Physicochemical Properties of Sprouted Fava Bean Flour–Fermented Red Rice Flour Mixed System and Its Application in Gluten-Free Noodles

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Pre-Treatment of Materials

2.2.1. Fermentation Treatment of Red Rice

2.2.2. Sprouting Treatment for Fava Beans

2.3. Preparation of Mixed Flour

2.4. Determination of Physiochemical Properties of Flours

2.4.1. Water Absorption Capacity, Solubility, and Swelling Power

2.4.2. Thermal Properties

2.4.3. Pasting Properties

2.4.4. Dynamic Rheological Measurements

2.5. Preparation of Dough

2.6. Interaction of the Main Components in the Dough

2.6.1. Chemical Interactions

2.6.2. X-Ray Diffraction (XRD)

2.6.3. Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectroscopy

2.6.4. Moisture Distribution Analysis

2.7. Preparation of Noodles

2.8. Determination of Quality Properties of Noodles

2.8.1. Microstructure of Noodles

- (1)

- Scanning electron microscopy (SEM)

- (2)

- Confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM)

2.8.2. Cooking Properties

2.8.3. Textural Properties

2.8.4. Color

2.8.5. Total Phenolic Content and Antioxidant Activity

2.8.6. In Vitro Digestibility of Starch

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussions

3.1. Water Absorption Capacity, Solubility, and Swelling Power Swelling

3.2. Thermal Properties

3.3. Pasting Property

3.4. Dynamic Rheological Measurements

3.5. Chemical Interactions

3.6. X-Ray Diffraction (XRD)

3.7. FTIR Analysis

3.7.1. Functional Group Structure Analysis

3.7.2. Protein Secondary Structure Analysis

3.7.3. Analysis of Short-Range Ordering of Starch

3.8. Moisture Distribution Analysis

3.9. Microstructure of Noodles

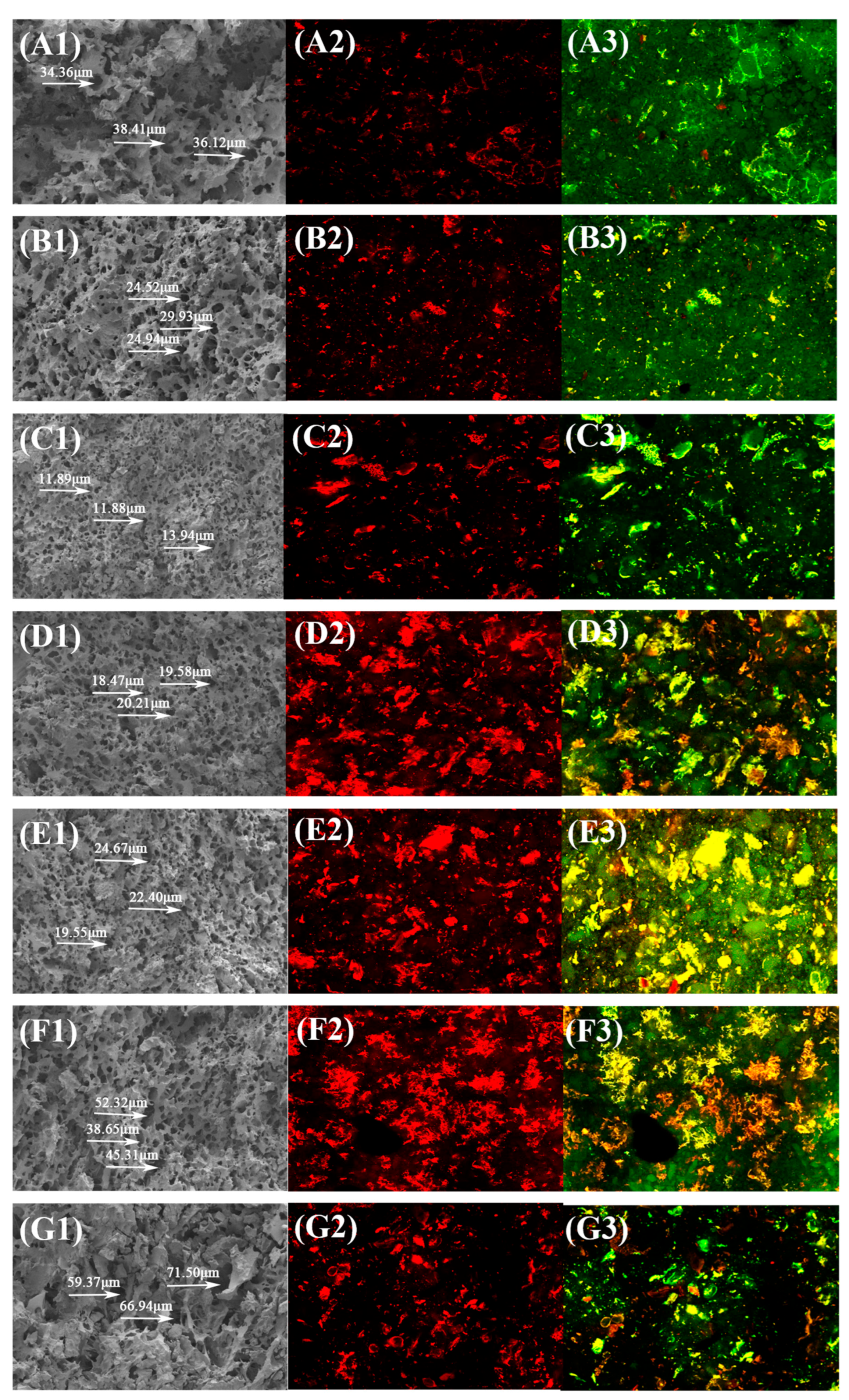

3.9.1. SEM Analysis

3.9.2. CLSM Analysis

3.10. Cooking Properties

3.11. Textural Properties

3.12. Color Parameters of Noodles

3.13. Total Phenolic Content and Antioxidant Properties of Noodles

3.14. Starch Digestion and Glycemic Index

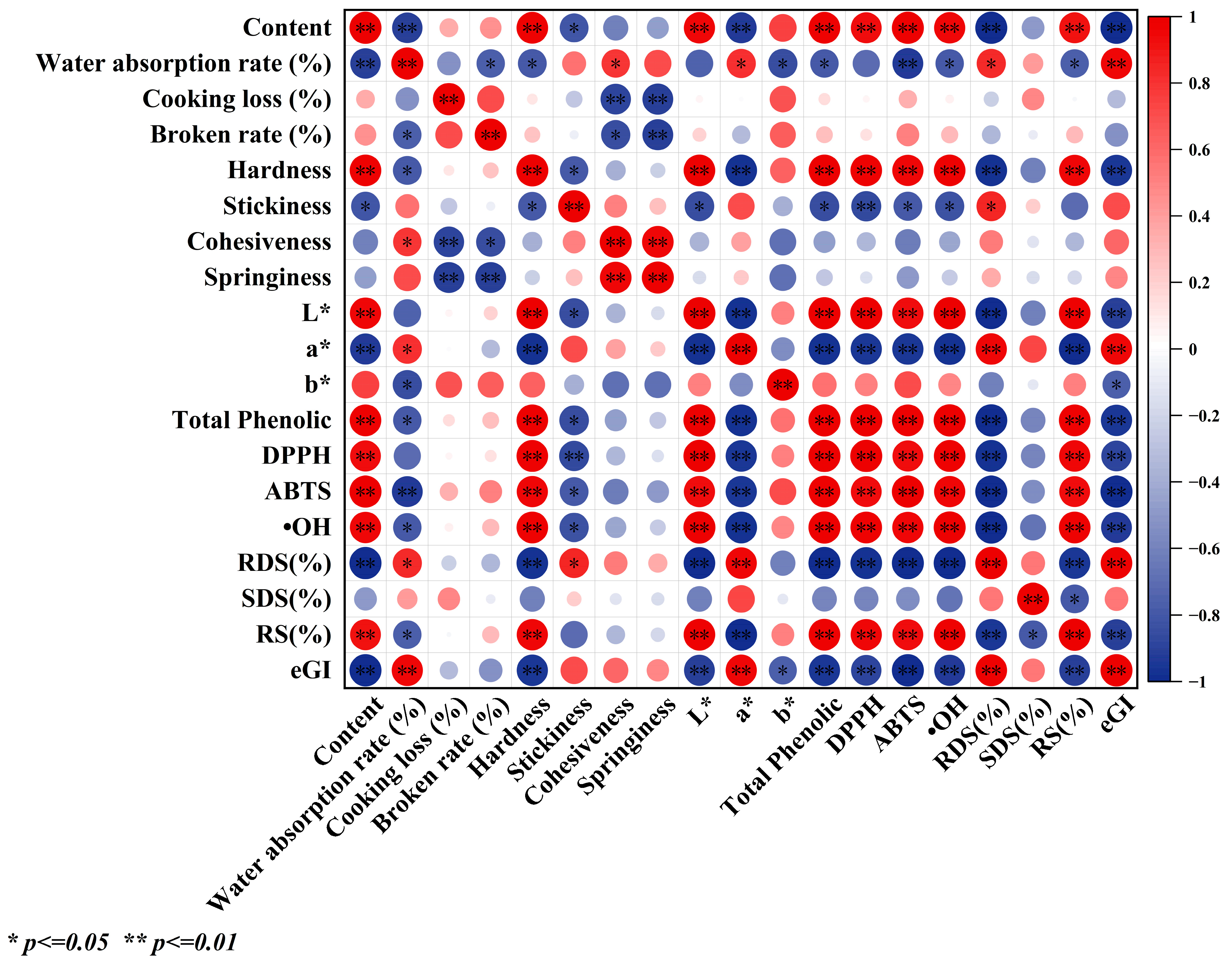

3.15. Pearson’s Correlation Coefficient Analysis

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Malalgoda, M.; Simsek, S. Celiac disease and cereal proteins. Food Hydrocoll. 2017, 68, 108–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catassi, C.; Verdu, E.F.; Bai, J.C.; Lionetti, E. Coeliac disease. Lancet 2022, 399, 2413–2426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qadir, N.; Wani, I.A. In-vitro digestibility of rice starch and factors regulating its digestion process: A review. Carbohydr. Polym. 2022, 291, 119600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nugraheni, M.; Windarwati, W.; Palupi, S. Gluten-free noodles made based on germinated organic red rice: Chemical composition, bioactive compounds, antioxidant activity and sensory evaluation. Food Res. 2022, 6, 354–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, A.B.; Bhattacharya, S. Characterization of the batter and gluten-free cake from extruded red rice flour. LWT 2019, 102, 197–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senevirathna, S.S.J.; Ramli, N.S.; Azman, E.M.; Juhari, N.H.; Karim, R. Production of innovative antioxidant-rich and gluten-free extruded puffed breakfast cereals from purple sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas L.) and red rice using a mixture design approach. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2022, 46, e16666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Se, C.-H.; Chuah, K.-A.; Mishra, A.; Wickneswari, R.; Karupaiah, T. Evaluating Crossbred Red Rice Variants for Postprandial Glucometabolic Responses: A Comparison with Commercial Varieties. Nutrients 2016, 8, 308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finocchiaro, F.; Ferrari, B.; Gianinetti, A.; Dall’Asta, C.; Galaverna, G.; Scazzina, F.; Pellegrini, N. Characterization of antioxidant compounds of red and white rice and changes in total antioxidant capacity during processing. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2007, 51, 1006–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wahyuni, S.; Asnani, A.; Khaeruni, A.; Dewi, N.D.P.; Sarinah, S.; Faradilla, R.H.F. Study on physicochemical characteristics of local colored rice varieties (black, red, brown, and white) fermented with lactic acid bacteria (SBM.4A). J. Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 60, 3035–3042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lancetti, R.; Salvucci, E.; Moiraghi, M.; Pérez, G.T.; Sciarini, L.S. Gluten-free flour fermented with autochthonous starters for sourdough production: Effect of the fermentation process. Food Biosci. 2022, 47, 101723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudau, M.; Mashau, M.E.; Ramashia, S.E. Nutritional Quality, Antioxidant, Microstructural and Sensory Properties of Spontaneously Fermented Gluten-Free Finger Millet Biscuits. Foods 2022, 11, 1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Chen, W.; Zhu, H.; Yi, C.; Yuan, J.; Liu, Y.; Li, Z.; Cheng, H. Digestibility of indica rice and structural changes of rice starch during fermentation by Lactobacillus plantarum. LWT 2023, 187, 115392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, L.; Wu, W. Fermentation Effect on the Properties of Sweet Potato Starch and its Noodle’s Quality by Lactobacillus plantarum. J. Food Process Eng. 2017, 40, e12460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karataş, S.Ç; Günay, D.; Sayar, S. In vitro evaluation of whole faba bean and its seed coat as a potential source of functional food components. Food Chem. 2017, 230, 182–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahate, K.A.; Madhumita, M.; Prabhakar, P.K. Nutritional composition, anti-nutritional factors, pretreatments-cum-processing impact and food formulation potential of faba bean (Vicia faba L.): A comprehensive review. LWT 2021, 138, 110796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikram, A.; Saeed, F.; Afzaal, M.; Imran, A.; Niaz, B.; Tufail, T.; Hussain, M.; Anjum, F.M. Nutritional and end-use perspectives of sprouted grains: A comprehensive review. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021, 9, 4617–4628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakshmipathy, K.; Buvaneswaran, M.; Rawson, A.; Chidanand, D.V. Effect of dehulling and germination on the functional properties of grass pea (Lathyrus sativus) flour. Food Chem. 2024, 449, 139265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akkad, R.; Buchko, A.; Johnston, S.P.; Han, J.; House, J.D.; Curtis, J.M. Sprouting improves the flavour quality of faba bean flours. Food Chem. 2021, 364, 130355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, L.; Xiong, G.; Wang, Q.; Xiang, X.; Long, Z.; Huang, Z.; Ding, Y.; Liu, C. Enhancing cooking and eating quality of semi-dried brown rice noodles through Lactobacillus fermentation and moderate lysine addition. Food Chem. X 2025, 26, 102327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Woo, S.-H.; Park, J.-D.; Sung, J.M. Changes in physicochemical properties of rice flour by fermentation with koji and its potential use in gluten-free noodles. J. Food Sci. 2021, 86, 5188–5199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, X.; Sui, J.; Qiu, H.; Sun, C.; Zhang, H.; Cui, B.; Abd El-Aty, A.M. Effects of wheat protein on the formation and structural properties of starch-lipid complexes in real noodles incorporated with fatty acids of varying chain lengths. LWT 2021, 144, 111271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.; Chiang, J.H.; Tan, M.Y.P.; Saw, L.K.; Xu, Y.; Ngan-Loong, M.N. Physicochemical properties of hydrothermally treated glutinous rice flour and xanthan gum mixture and its application in gluten-free noodles. J. Food Eng. 2016, 186, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, F.-H.; Li, X.-J.; Luo, S.-Z.; Mu, D.-D.; Zhong, X.-Y.; Jiang, S.-T.; Zheng, Z.; Zhao, Y.-Y. Effects of organic acid coagulants on the physical properties of and chemical interactions in tofu. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 85, 58–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Liu, C.; Zheng, X.; Hong, J.; Bian, K.; Li, L. Interaction between A-type/B-type starch granules and gluten in dough during mixing. Food Chem. 2021, 358, 129870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Yang, S.; Zhang, M.; Shan, C.; Chen, Z. Effects of potato starch on the characteristics, microstructures and quality attributes of indica rice flour and instant rice noodles. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 57, 2285–2297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, M.; Shen, C.; Li, Y.; Xiong, S.; Li, F. The Quality Characteristics Comparison of Stone-Milled Dried Whole Wheat Noodles, Dried Wheat Noodles, and Commercially Dried Whole Wheat Noodles. Foods 2023, 12, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, J.; Moon, Y.; Kweon, M. The Effects of Milling Conditions on the Particle Size, Quality, and Noodle-Making Performance of Whole-Wheat Flour: A Mortar Mill Study. Foods 2025, 14, 1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Cervantes, M.E.; Hernández-Uribe, J.P.; Gómez-Aldapa, C.A.; Navarro-Cortez, R.O.; Palma-Rodríguez, H.M.; Vargas-Torres, A. Physicochemical, functional, and quality properties of fettuccine pasta added with huitlacoche mushroom (Ustilago maydis). J. Food Process. Preserv. 2021, 45, e15825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Zhao, Y.; Yao, X.; Zheng, Z.; Zheng, C.; Jiang, Z. Effect of high hydrostatic pressure pretreatment on flavour and physicochemical properties of freeze-dried carambola slices. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 57, 4245–4253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, D.; Zhou, W.; Yang, Z.; Zhong, Y.; Xing, B.; Wu, Z.; Chen, H.; Wu, D.; Zhang, Q.; Qin, W.; et al. Study on physicochemical properties, digestive properties and application of acetylated starch in noodles. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 128, 948–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yenasew, A.; Urga, K. Effect of the germination period on functional properties of finger millet flour and sensorial quality of porridge. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 11, 2336–2343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.; Man, J.; Huang, J.; Liu, Q.; Wei, W.; Wei, C. Relationship between structure and functional properties of normal rice starches with different amylose contents. Carbohydr. Polym. 2015, 125, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, D.; Li, H.; Li, D.; Zhang, D.; Huang, Y.; Obadi, M.; Xu, B. The relation between wheat starch properties and noodle springiness: From the view of microstructure quantitative analysis of gluten-based network. Food Chem. 2022, 393, 133396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ang, K.; Bourgy, C.; Fenton, H.; Regina, A.; Newberry, M.; Diepeveen, D.; Lafiandra, D.; Grafenauer, S.; Hunt, W.; Solah, V. Noodles Made from High Amylose Wheat Flour Attenuate Postprandial Glycaemia in Healthy Adults. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieves-Hernández, M.G.; Correa-Piña, B.L.; Esquivel-Fajardo, E.A.; Barrón-García, O.Y.; Gaytán-Martínez, M.; Rodriguez-Garcia, M.E. Study of morphological, structural, pasting, thermal, and vibrational changes in maize and isolated maize starch during germination. J. Cereal Sci. 2023, 111, 103685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, R.; Prasad, K. Elucidation of chickpea hydration, effect of soaking temperature, and extent of germination on characteristics of malted flour. J. Food Sci. 2022, 87, 2197–2210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sofi, S.A.; Rafiq, S.; Singh, J.; Mir, S.A.; Sharma, S.; Bakshi, P.; McClements, D.J.; Khaneghah, A.M.; Dar, B.N. Impact of germination on structural, physicochemical, techno-functional, and digestion properties of desi chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) flour. Food Chem. 2023, 405, 135011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicente, A.; Villanueva, M.; Caballero, P.A.; Muñoz, J.M.; Ronda, F. Buckwheat grains treated with microwave radiation: Impact on the techno-functional, thermal, structural, and rheological properties of flour. Food Hydrocoll. 2023, 137, 108328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Jan, R.; Riar, C.S.; Bansal, V. Analyzing the effect of germination on the pasting, rheological, morphological and in- vitro antioxidant characteristics of kodo millet flour and extracts. Food Chem. 2021, 361, 130073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, W.; Yin, L.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, M.; Jia, X. Gelatinization, Retrogradation and Gel Properties of Wheat Starch–Wheat Bran Arabinoxylan Complexes. Gels 2021, 7, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sofi, S.A.; Singh, J.; Muzaffar, K.; Dar, B.N. Effect of Germination Time on Physicochemical, Electrophoretic, Rheological, and Functional Performance of Chickpea Protein Isolates. ACS Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 1, 802–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.; Chen, B.; Xu, R.; Liu, T.; Huangfu, J.; Zhou, F.; Zhao, M.; Zhao, Q. Effects of heat treatment at different moisture of mung bean flour on the structural, gelation and in vitro digestive properties of starch. Food Chem. 2024, 443, 138518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Wang, G.; Wen, P.; Chen, Y.; Yu, Q.; Shen, M.; Xie, J. Effect of purple red rice bran anthocyanins on pasting, rheological and gelling properties of rice starch. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 247, 125689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Z.-H.; Li, L.-T.; Min, W.-H.; Wang, F.; Tatsumi, E. The effects of natural fermentation on the physical properties of rice flour and the rheological characteristics of rice noodles. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2005, 40, 985–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Shen, W.; Jin, W.; Li, F.; Chen, X.; Jia, X.; Cai, H. Physicochemical characterization of a composite flour: Blending purple sweet potato and rice flours. Food Chem. X 2024, 22, 101493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamboj, U.; Paramita, G.; Mishra, S. Characterization of Chickpea Flour by Near Infrared Spectroscopy and Chemometrics. Anal. Lett. 2017, 50, 1754–1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, S.; Guo, Q.; Ren, W.; Zhou, M.; Dai, S.; Zhao, Y.; Yang, W.; Xiao, C.; Liu, X.; Wang, D.; et al. Production, structural and functional properties of dietary fiber from prosomillet bran obtained through Bifidobacterium fermentation. Food Chem. 2025, 475, 143264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vela, A.J.; Villanueva, M.; Solaesa, Á.G.; Ronda, F. Impact of high-intensity ultrasound waves on structural, functional, thermal and rheological properties of rice flour and its biopolymers structural features. Food Hydrocoll. 2021, 113, 106480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roa-Acosta, D.F.; Bravo-Gómez, J.E.; García-Parra, M.A.; Rodríguez-Herrera, R.; Solanilla-Duque, J.F. Hyper-protein quinoa flour (Chenopodium Quinoa Wild): Monitoring and study of structural and rheological properties. LWT 2020, 121, 108952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Zhong, F.; Yokoyama, W.; Huang, D.; Zhu, S.; Li, Y. Interactions in starch co-gelatinized with phenolic compound systems: Effect of complexity of phenolic compounds and amylose content of starch. Carbohydr. Polym. 2020, 247, 116667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, C.; Wang, B. Effect of camellia oil gel on rheology, water distribution and microstructure of flour dough for crispy biscuits. J. Cereal Sci. 2024, 117, 103912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Xu, M.; Wu, H.; Jing, L.; Gong, B.; Gou, M.; Zhao, K.; Li, W. The compositional, physicochemical and functional properties of germinated mung bean flour and its addition on quality of wheat flour noodle. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 55, 5142–5152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Odabas, E.; Aktas-Akyildiz, E.; Cakmak, H. Effect of raw and heat-treated yellow lentil flour on starch-based gluten-free noodle quality. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2022, 46, e16825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, S.; Wang, L.; Wang, A.; Zhang, Q.; Li, Z.; Qiu, J. Effect of Moisture Distribution Changes Induced by Different Cooking Temperature on Cooking Quality and Texture Properties of Noodles Made from Whole Tartary Buckwheat. Foods 2021, 10, 2543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Pang, L.; Bao, L.; Ye, X.; Lu, G. Effect of White Kidney Bean Flour on the Rheological Properties and Starch Digestion Characteristics of Noodle Dough. Foods 2022, 11, 3680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, K.M.; Lee, J.H.; Yun, H.D.; Ahn, B.Y.; Kim, H.; Seo, W.T. Changes of phytochemical constituents (isoflavones, flavanols, and phenolic acids) during cheonggukjang soybeans fermentation using potential probiotics Bacillus subtilis CS90. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2011, 24, 402–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, R.-Y.; Shah, N.P.; Wang, M.-F.; Lui, W.-Y.; Corke, H. Lactobacillus plantarum WCFS1 Fermentation Differentially Affects Antioxidant Capacity and Polyphenol Content in Mung bean (Vigna radiata) and Soya Bean (Glycine max) Milks. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2017, 41, e12944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilowefah, M.; Bakar, J.; Ghazali, H.M.; Muhammad, K. Enhancement of Nutritional and Antioxidant Properties of Brown Rice Flour Through Solid-State Yeast Fermentation. Cereal Chem. 2017, 94, 519–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonard, W.; Zhang, P.; Ying, D.; Adhikari, B.; Fang, Z. Fermentation transforms the phenolic profiles and bioactivities of plant-based foods. Biotechnol. Adv. 2021, 49, 107763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fois, S.; Campus, M.; Piu, P.P.; Siliani, S.; Sanna, M.; Roggio, T.; Catzeddu, P. Fresh Pasta Manufactured with Fermented Whole Wheat Semolina: Physicochemical, Sensorial, and Nutritional Properties. Foods 2019, 8, 422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, G.; Singh, B.; Singh, A.; Sharma, S. Functionality of Barley pasta supplemented with Mungbean flour: Cooking behavior, quality characteristics and morphological interactions. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2023, 17, 5806–5820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuberti, G.; Gallo, A.; Cerioli, C.; Fortunati, P.; Masoero, F. Cooking quality and starch digestibility of gluten free pasta using new bean flour. Food Chem. 2015, 175, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Samples | Thermal Properties | Pasting Property | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T0 (°C) | Tp (°C) | Tc (°C) | ΔH (J/g) | Peak Viscosity (cP) | Trough Viscosity (cP) | Breakdown (cP) | Final Viscosity (cP) | Setback (cP) | Peak Time (min) | Paste Temperature (°C) | |

| FBF | 61.88 ± 0.45 e | 73.18 ± 0.65 h | 81.76 ± 1.09 h | 3.36 ± 0.22 g | 703.00 ± 3.61 h | 694.00 ± 3.46 h | 46.67 ± 3.06 h | 1073.67 ± 19.60 g | 379.67 ± 16.50 f | 6.80 ± 0.07 a | 82.08 ± 0.46 cd |

| S-FBF | 60.83 ± 0.57 i | 70.90 ± 0.78 i | 76.72 ± 0.87 i | 2.48 ± 0.34 h | 667.33 ± 5.86 i | 634.33 ± 4.16 i | 33.00 ± 2.65 h | 813.67 ± 20.03 i | 222.67 ± 4.04 g | 6.31 ± 0.23 b | 79.90 ± 0.05 f |

| RRF | 69.41 ± 0.79 a | 82.25 ± 0.55 a | 90.59 ± 0.67 a | 5.22 ± 0.19 e | 2221.50 ± 10.61 c | 1495.50 ± 3.54 a | 726.00 ± 14.14 d | 3290.00 ± 1.41 a | 1794.50 ± 4.95 a | 5.64 ± 0.05 de | 87.63 ± 0.53 a |

| F-RRF | 65.88 ± 0.64 b | 79.99 ± 0.70 b | 89.44 ± 0.64 b | 8.03 ± 0.35 a | 2624.50 ± 2.12 a | 1309.50 ± 27.58 b | 1315.00 ± 25.46 a | 2176.00 ± 38.18 c | 866.50 ± 10.61 c | 5.90 ± 0.04 c | 83.22 ± 0.11 b |

| S-F10 | 63.17 ± 0.61 c | 79.49 ± 0.41 c | 88.86 ± 0.49 c | 6.00 ± 0.27 b | 2503.67 ± 9.24 b | 1289.00 ± 11.53 c | 1214.67 ± 15.31 b | 2238.00 ± 14.73 b | 956.00 ± 2.00 b | 5.71 ± 0.03 d | 82.95 ± 0.48 b |

| S-F20 | 62.58 ± 0.78 d | 78.75 ± 0.49 d | 88.06 ± 0.75 d | 5.75 ± 0.33 c | 2187.00 ± 11.36 d | 1217.00 ± 7.21 d | 970.00 ± 12.77 c | 2173.33 ± 7.02 c | 953.33 ± 2.08 b | 5.55 ± 0.04 def | 82.63 ± 0.49 bc |

| S-F30 | 61.72 ± 0.72 f | 78.35 ± 0.86 e | 87.70 ± 0.32 e | 5.55 ± 0.21 d | 1822.00 ± 12.00 e | 1184.67 ± 10.60 e | 637.33 ± 10.02 e | 2061.00 ± 10.00 d | 876.33 ± 1.53 c | 5.47 ± 0.00 efg | 82.05 ± 0.52 cd |

| S-F40 | 61.36 ± 0.36 g | 77.98 ± 0.69 f | 86.86 ± 0.59 f | 5.23 ± 0.37 e | 1469.00 ± 5.66 f | 1074.50 ± 3.54 f | 394.50 ± 9.19 f | 1818.50 ± 12.02 e | 755.00 ± 15.56 d | 5.40 ± 0.00 fg | 81.58 ± 0.35 d |

| S-F50 | 61.06 ± 0.72 h | 77.64 ± 0.41 g | 86.32 ± 0.83 g | 5.01 ± 0.31 f | 1277.00 ± 18.52 g | 1002.33 ± 5.13 g | 274.67 ± 14.43 g | 1608.33 ± 12.34 f | 606.00 ± 7.21 e | 5.33 ± 0.07 g | 80.72 ± 0.08 e |

| Samples | T21 (ms) | T22 (ms) | T23 (ms) | A21 (%) | A22 (%) | A23 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FBF | 0.52 ± 0.04 g | 12.75 ± 0.05 d | 191.63 ± 0.15 b | 4.01 ± 0.61 i | 95.71 ± 0.21 a | 0.28 ± 0.61 h |

| S-FBF | 0.50 ± 0.17 g | 12.75 ± 0.05 d | 181.63 ± 0.21 c | 4.08 ± 0.39 h | 95.48 ± 0.64 b | 0.44 ± 0.25 g |

| RRF | 4.80 ± 0.04 a | 19.65 ± 0.03 a | 251.60 ± 0.44 a | 27.08 ± 0.19 d | 72.88 ± 0.25 f | 0.04 ± 0.63 i |

| F-RRF | 1.24 ± 0.05 f | 9.75 ± 0.02 f | 89.33 ± 0.35 i | 32.52 ± 0.98 a | 65.47 ± 0.47 i | 2.01 ± 0.56 a |

| S-F10 | 1.95 ± 0.04 e | 10.83 ± 0.03 e | 117.63 ± 0.25 h | 30.44 ± 0.68 b | 68.21 ± 0.26 h | 1.35 ± 0.36 b |

| S-F20 | 2.65 ± 0.02 c | 12.75 ± 0.05 d | 124.43 ± 0.42 g | 27.41 ± 0.75 c | 71.86 ± 0.47 g | 0.73 ± 0.85 f |

| S-F30 | 2.67 ± 0.02 c | 12.75 ± 0.05 d | 131.17 ± 0.12 f | 21.47 ± 0.34 e | 77.59 ± 0.26 e | 0.94 ± 0.25 d |

| S-F40 | 2.89 ± 0.08 b | 14.20 ± 0.05 b | 154.37 ± 0.15 d | 21.35 ± 0.35 f | 77.86 ± 0.96 d | 0.79 ± 0.86 e |

| S-F50 | 2.51 ± 0.03 d | 13.47 ± 0.05 c | 138.41 ± 0.15 e | 15.27 ± 0.21 g | 83.71 ± 0.51 c | 0.99 ± 0.31 c |

| Samples | Cooking Properties | Texture Properties | Color Properties | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Water Absorption Rate (%) | Cooking Loss (%) | Breakage Rate (%) | Hardness (N) | Stickiness (mJ) | Cohesiveness | Springiness (mm) | L* | a* | b* | |

| RRN | 49.70 ± 0.36 bc | 8.15 ± 0.36 a | 31.67 ± 2.89 b | 15.17 ± 2.57 e | 0.09 ± 0.02 ab | 0.42 ± 0.10 b | 0.36 ± 0.02 b | 38.85 ± 1.44 f | 12.35 ± 0.14 a | 13.53 ± 0.22 ab |

| F-RRN | 55.80 ± 2.31 a | 3.48 ± 0.40 e | 10.53 ± 5.27 c | 21.17 ± 1.15 d | 0.10 ± 0.04 a | 0.76 ± 0.16 a | 0.50 ± 0.10 a | 41.21 ± 0.43 e | 10.83 ± 0.31 b | 12.82 ± 0.24 bc |

| S-F10 | 53.00 ± 2.63 ab | 4.59 ± 0.13 d | 11.54 ± 0.38 c | 23.17 ± 1.61 cd | 0.06 ± 0.01 b | 0.60 ± 0.09 ab | 0.46 ± 0.05 a | 43.47 ± 0.00 d | 10.36 ± 0.06 bc | 12.55 ± 0.57 c |

| S-F20 | 51.70 ± 1.57 abc | 5.97 ± 0.15 c | 12.28 ± 3.04 c | 26.00 ± 2.65 c | 0.05 ± 0.02 b | 0.52 ± 0.10 ab | 0.44 ± 0.03 ab | 44.10 ± 1.55 d | 10.24 ± 0.17 c | 12.87 ± 0.06 bc |

| S-F30 | 47.33 ± 3.79 c | 6.57 ± 0.23 bc | 13.73 ± 6.8 c | 30.17 ± 1.26 b | 0.05 ± 0.01 b | 0.53 ± 0.02 ab | 0.42 ± 0.04 ab | 44.86 ± 0.25 cd | 10.01 ± 0.38 c | 13.86 ± 0.32 a |

| S-F40 | 39.15 ± 3.79 d | 6.44 ± 0.44 bc | 21.69 ± 14.61 bc | 34.83 ± 1.15 a | 0.05 ± 0.02 b | 0.48 ± 0.05 ab | 0.42 ± 0.05 ab | 46.76 ± 0.95 bc | 8.50 ± 0.10 d | 14.17 ± 0.03 a |

| S-F50 | 32.37 ± 2.10 e | 6.88 ± 0.24 b | 40.29 ± 3.21 a | 35.67 ± 1.53 a | 0.05 ± 0.02 b | 0.34 ± 0.33 b | 0.35 ± 0.03 b | 47.43 ± 0.74 b | 7.64 ± 0.37 e | 14.05 ± 0.51 a |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Min, Z.; Zheng, T.; Wang, J.; Hu, W.; Yang, Q.; Kong, Y. Physicochemical Properties of Sprouted Fava Bean Flour–Fermented Red Rice Flour Mixed System and Its Application in Gluten-Free Noodles. Foods 2025, 14, 4302. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244302

Min Z, Zheng T, Wang J, Hu W, Yang Q, Kong Y. Physicochemical Properties of Sprouted Fava Bean Flour–Fermented Red Rice Flour Mixed System and Its Application in Gluten-Free Noodles. Foods. 2025; 14(24):4302. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244302

Chicago/Turabian StyleMin, Zhongman, Ting Zheng, Jinghan Wang, Wenkai Hu, Qingyu Yang, and Yanwen Kong. 2025. "Physicochemical Properties of Sprouted Fava Bean Flour–Fermented Red Rice Flour Mixed System and Its Application in Gluten-Free Noodles" Foods 14, no. 24: 4302. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244302

APA StyleMin, Z., Zheng, T., Wang, J., Hu, W., Yang, Q., & Kong, Y. (2025). Physicochemical Properties of Sprouted Fava Bean Flour–Fermented Red Rice Flour Mixed System and Its Application in Gluten-Free Noodles. Foods, 14(24), 4302. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244302