Upcycling Grape Pomace in a Plant-Based Yogurt Alternative: Starter Selection, Phenolic Profiling, and Antioxidant Efficacy on Human Keratinocytes

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Raw Materials and Microorganisms

2.2. Gurts Production Process

2.3. Microbiological and Biochemical Characterization

2.4. Color and Sensory Analysis

2.5. Study of Gurts Phenolic Profile

2.5.1. Extraction of Phenolic Compounds

2.5.2. Qualitative and Quantitative Analysis of Phenolic Compounds

2.5.3. Quantification of Proanthocyanidins

2.6. Study of Gurts Antioxidant Potential on Human Keratinocytes

2.6.1. Human Keratinocytes Cell Culture

2.6.2. Proliferation Assay

2.6.3. Oxidative Stress Assay

2.6.4. qRT-PCR Assay

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Starter Selection

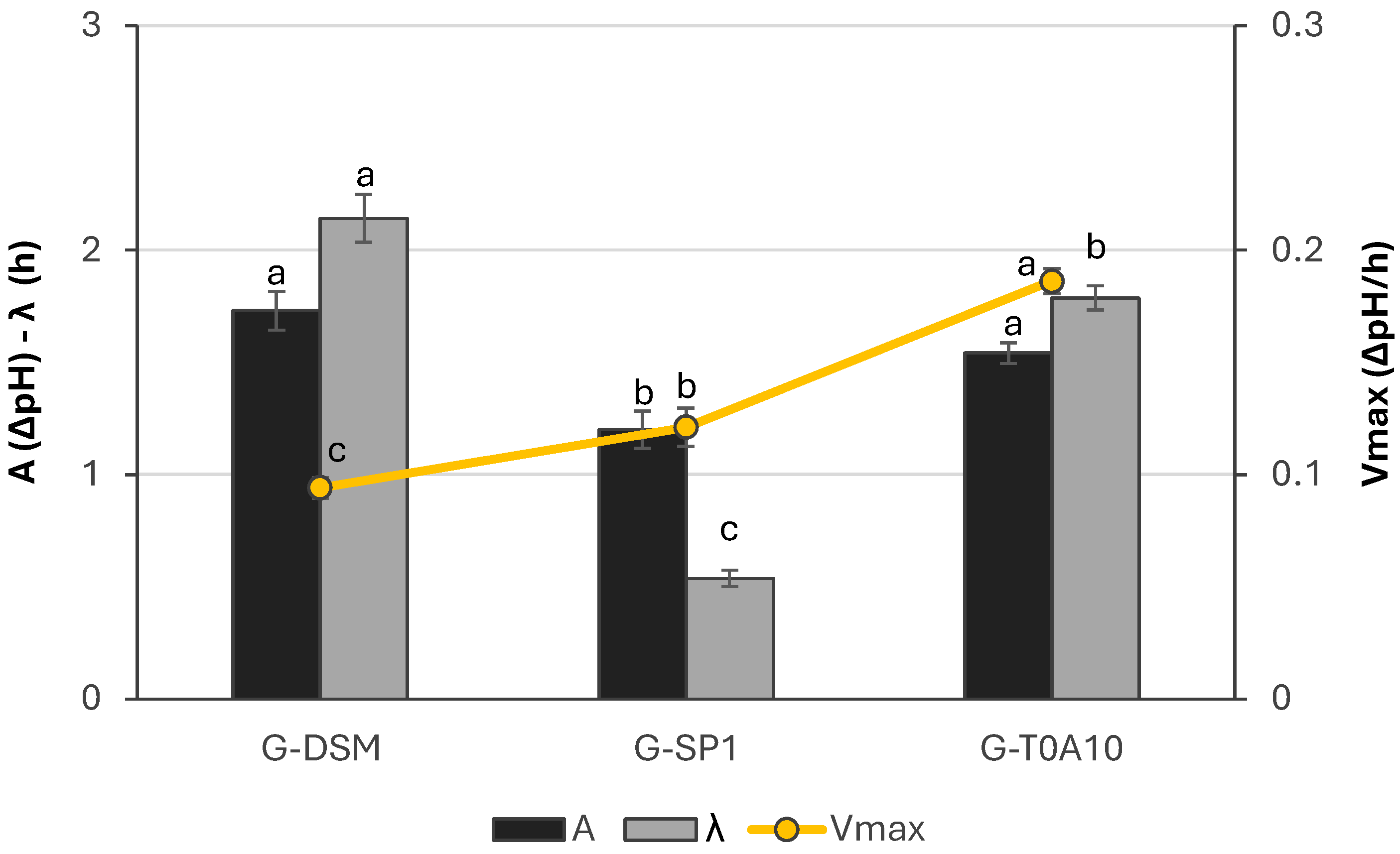

3.1.1. Growth and Acidification

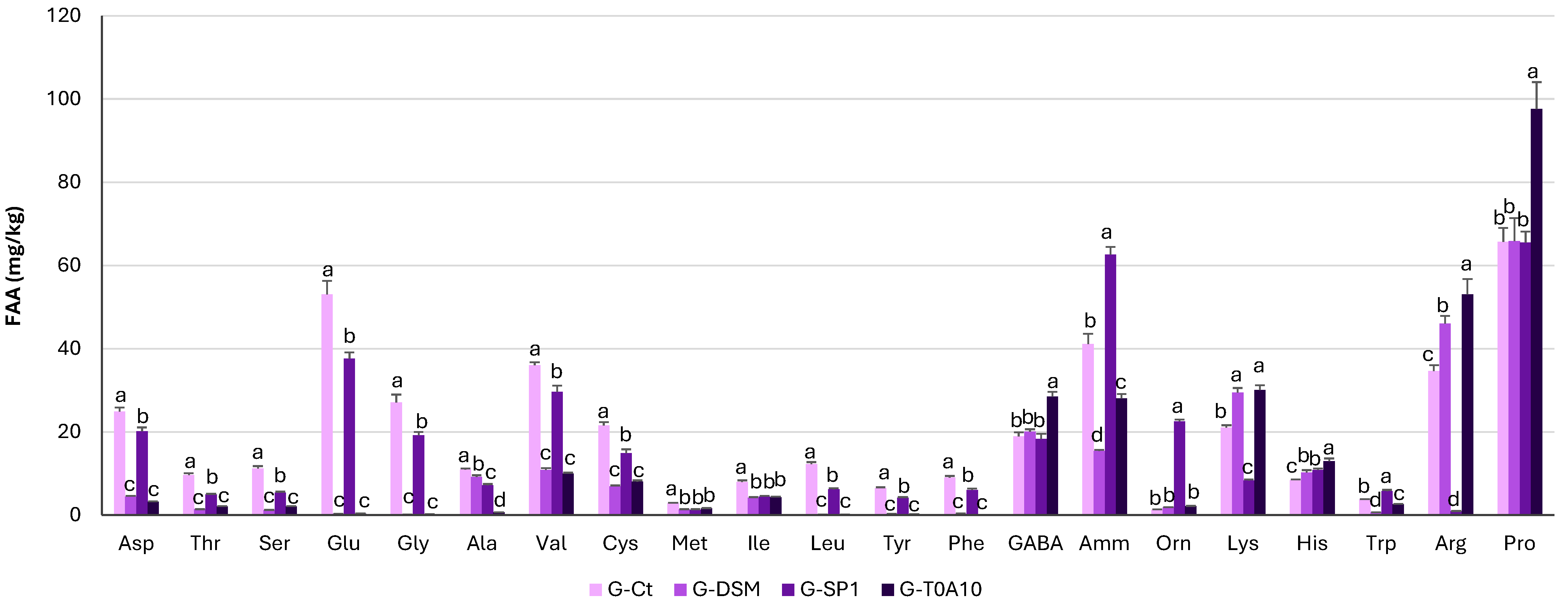

3.1.2. Organic Acids and Free Amino Acids

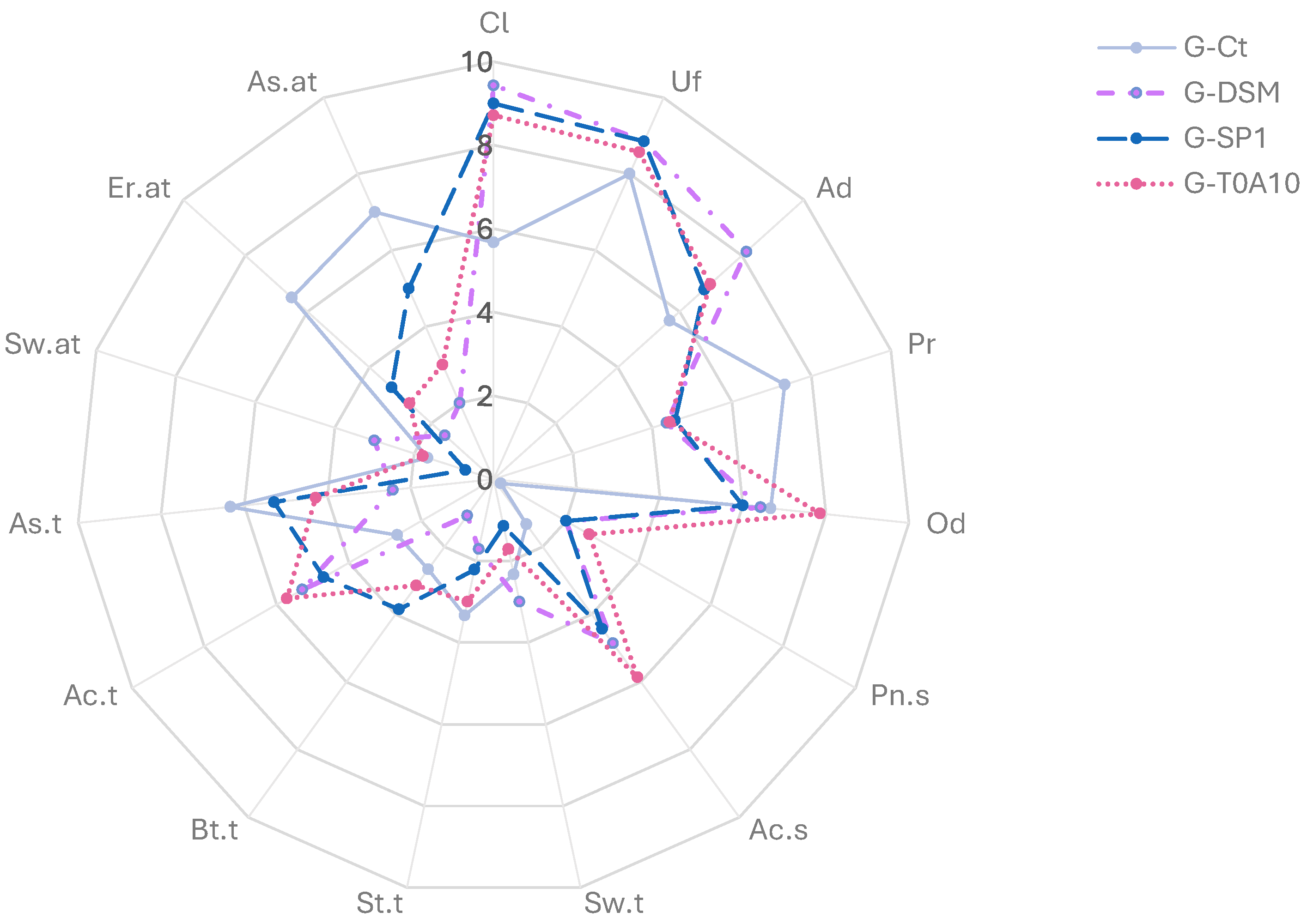

3.1.3. Nutritional, Functional, and Sensory Characteristics

3.1.4. Shelf-Life Monitoring

3.2. Phenolic Compounds Profile

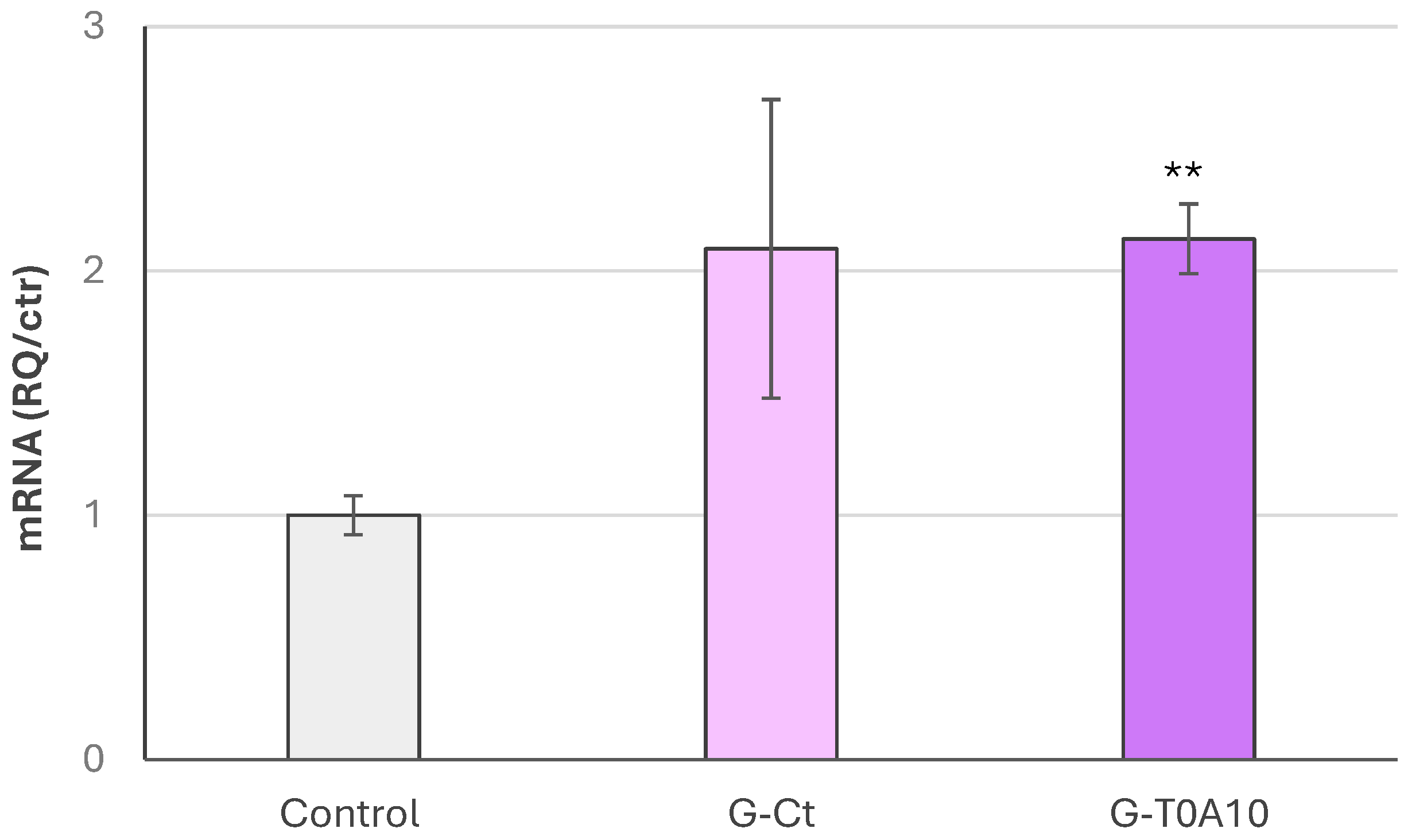

3.3. Proliferative Activity and Protection from Oxidative Stress

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| cDNA | Complementary DNA |

| DMSO | Dimethyl sulphoxide |

| DPPH | 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl |

| FAA | Free amino acids |

| FBS | Fetal bovine serum |

| GABA | γ-Aminobutyric acid |

| GP | Grape pomace |

| G-Ct | Control gurt |

| G-DSM | Gurt fermented with Leuconostoc pseudomesenteroides DMS20193 |

| G-SP1 | Gurt fermented with Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus SP1 |

| G-T0A10 | Gurt fermented with Lactiplantibacillus plantarum T0A10 |

| LAB | Lactic acid bacteria |

| qRT-PCR | Quantitative reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction |

| SOD2 | Superoxide dismutase 2 |

| TTA | Total titratable acidity |

References

- Perra, M.; Bacchetta, G.; Muntoni, A.; De Gioannis, G.; Castangia, I.; Rajha, H.N.; Manconi, M. An outlook on modern and sustainable approaches to the management of grape pomace by integrating green processes, biotechnologies and advanced biomedical approaches. J. Funct. Foods 2022, 98, 105276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, J.D.C.; Madureira, J.; Margaça, F.M.; Cabo Verde, S. Grape pomace: A review of its bioactive phenolic compounds, health benefits, and applications. Molecules 2025, 30, 362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karastergiou, A.; Gancel, A.L.; Jourdes, M.; Teissedre, P.L. Valorization of grape pomace: A review of phenolic composition, bioactivity, and therapeutic potential. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bordiga, M.; Travaglia, F.; Locatelli, M. Valorisation of grape pomace: An approach that is increasingly reaching its maturity–A review. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 54, 933–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qadir, R.; Nasir, W.N.A.W.M.; Azmi, A.B.; Fatima, S.; Mehmood, N.; Hussin, A.S.M. An insight into plant-based yogurts: Physicochemical, organoleptic properties and functional food aspects. J. Food Comp. Anal. 2025, 143, 107578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demarinis, C.; Verni, M.; Koirala, P.; Cera, S.; Rizzello, C.G.; Coda, R. Effect of LAB starters on technological and functional properties of composite carob and chickpea flour plant-based gurt. Fut. Foods 2024, 9, 100289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caponio, M.; Verni, M.; Tlais, A.Z.A.; Longo, E.; Pontonio, E.; Di Cagno, R.; Rizzello, C.G. Development, optimization and integrated characterization of rice-based yogurt alternatives enriched with roasted and non-roasted sprouted barley flour. Cur. Res. Food Sci 2025, 10, 101059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montemurro, M.; Verni, M.; Fanelli, F.; Wang, Y.; Maina, H.N.; Torreggiani, A.; Rizzello, C.G. Molecular characterization of exopolysaccharide from Periweissella beninensis LMG 25373T and technological properties in plant-based food production. Food Res. Int. 2025, 201, 115537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Part, N.; Kazantseva, J.; Rosenvald, S.; Kallastu, A.; Vaikma, H.; Kriščiunaite, T.; Viiard, E. Microbiological, chemical, and sensorial characterisation of commercially available plant-based yoghurt alternatives. Fut. Foods 2023, 7, 100212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erem, E.; Kilic-Akyilmaz, M. The role of fermentation with lactic acid bacteria in quality and health effects of plant-based dairy analogues. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2024, 23, e13402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurćubić, V.S.; Stanišić, N.; Stajić, S.B.; Dmitrić, M.; Živković, S.; Kurćubić, L.V.; Mašković, J. Valorizing Grape Pomace: A Review of Applications, Nutritional Benefits, and Potential in Functional Food Development. Foods 2024, 13, 4169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coda, R.; Rizzello, C.G.; Trani, A.; Gobbetti, M. Manufacture and characterization of functional emmer beverages fermented by selected lactic acid bacteria. Food Microbiol. 2011, 28, 526–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torreggiani, A.; Demarinis, C.; Pinto, D.; Papale, A.; Difonzo, G.; Caponio, F.; Rizzello, C.G. Up-cycling grape pomace through sourdough fermentation: Characterization of phenolic compounds, antioxidant activity, and anti-inflammatory potential. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AACC. Approved Methods of the American Association of Cereal Chemistry, 11th ed.; AACC: St. Paul, MN, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Zwietering, M.H.; Jongenburger, I.; Rombouts, F.M.; Van’t Riet, K.J.A.E.M. Modeling of the bacterial growth curve. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1990, 56, 1875–1881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiss, W.; Vogelmeier, C.; Görg, A. Electrophoretic characterization of wheat grain allergens from different cultivars involved in bakers’ asthma. Electrophoresis 1993, 14, 805–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verni, M.; Dingeo, C.; Rizzello, C.G.; Pontonio, E. Lactic acid bacteria fermentation and endopeptidase treatment improve the functional and nutritional features of Arthrospira platensis. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 744437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slinkard, K.; Singleton, V.L. Total phenol analysis: Automation and comparison with manual methods. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 1977, 28, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Perret, J.; Harris, M.; Wilson, J.; Haley, S. Antioxidant properties of bran extracts from “Akron” wheat grown at different locations. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2003, 51, 1566–1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 6564-1985; Sensory Analysis—Methodology—Flavour Profile-Methods. Technical Committee ISO/TC 34: Switzerland, 1985.

- Elia, M. A procedure for sensory evaluation of bread: Protocol developed by a trained panel. J. Sens. Stud. 2011, 26, 269–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verardo, V.; Arraez-Roman, D.; Segura-Carretero, A.; Marconi, E.; Fernandez-Gutierrez, A.; Caboni, M.F. Determination of free and bound phenolic compounds in buckwheat spaghetti by RP-HPLC-ESI-TOF-MS. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2011, 59, 7700–7707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-de-Cerio, E.; Gómez-Caravaca, A.M.; Verardo, V.; Fernández-Gutiérrez, A.; Segura-Carretero, A. Determination of guava phenolic compounds using HPLC-DAD-QTOF-MS. J. Funct. Foods 2016, 22, 376–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollands, W.J.; Voorspoels, S.; Jacobs, G.; Aaby, K.; Meisland, A.; Garcia-Villalba, R.; Tomas-Barberan, F.; Piskula, M.K.; Mawson, D.; Vovk, I.; et al. Determination of monomeric and oligomeric procyanidins in apple extracts. J. Chromatogr. A 2017, 1495, 46–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosmann, T. Rapid colorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival. J. Immunol. Methods 1983, 65, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chomczynski, P.; Mackey, K. Modification of the TRI reagent procedure for isolation of RNA. Biotechniques 1995, 19, 942–945. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Vigetti, D.; Viola, M.; Karousou, E.; Rizzi, M.; Moretto, P.; Genasetti, A.; Clerici, M.; Hascall, V.C.; De Luca, G.; Passi, A. Hyaluronan-CD44-ERK1/2 regulate smooth muscle cell motility. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 4448–4458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peixoto, C.M.; Dias, M.I.; Alves, M.J.; Calhelha, R.C.; Barros, L.; Pinho, S.P.; Ferreira, I.C. Grape pomace as a source of phenolic compounds. Food Chem. 2018, 253, 132–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaafar, A.A.; Asker, M.S. The effectiveness of the functional components of grape (Vitis vinifera) pomace as antioxidant, antimicrobial, and antiviral agents. Jordan J. Biol. Sci. 2019, 12, 625–635. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Gil, A.M.; Angenieux, M.; Pardo-Garcia, A.I.; Alonso, G.L.; Ojeda, H.; Salinas, M.R. Glycosidic aroma precursors after oak extract treatment. Food Chem. 2013, 138, 956–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Cerda-Carrasco, A.; López-Solís, R.; Nuñez-Kalasic, H.; Peña-Neira, Á.; Obreque-Slier, E. Phenolics and antioxidant capacity of pomaces from four grape varieties (Vitis vinifera L.). J. Sci. Food Agric. 2015, 95, 1521–1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mir-Cerdà, A.; Carretero, I.; Coves, J.R.; Pedrouso, A.; Castro-Barros, C.M.; Alvarino, T.; Cortina, J.L.; Saurina, J.; Granados, M.; Sentellas, S. Recovery of phenolic compounds from wine lees. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 857, 159623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Ramírez, I.F.; Reynoso-Camacho, R.; Saura-Calixto, F.; Pérez-Jiménez, J. Characterization of extractable and nonextractable phenolics. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2018, 66, 661–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Han, Y.; Tian, X.; Sajid, M.; Mehmood, S.; Wang, H.; Li, H. Phenolic composition of grape pomace. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2024, 64, 4865–4881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maier, T.; Sanzenbacher, S.; Kammerer, D.R.; Berardini, N.; Conrad, J.; Beifuss, U.; Schieber, A. Isolation of hydroxycinnamoyltartaric acids. J. Chromatogr. A 2006, 1128, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frum, A.; Georgescu, C.; Gligor, F.G.; Lengyel, E.; Stegarus, D.I.; Dobrea, C.M.; Tita, O. Identification and quantification of phenolic compounds from red grape pomace. Sci. Stud. Res. Chem. ChemEng. Biotech. Food Ind. 2018, 19, 45–52. [Google Scholar]

- Jara-Palacios, M.J.; Hernanz, D.; Cifuentes-Gomez, T.; Escudero-Gilete, M.L.; Heredia, F.J.; Spencer, J.P. Bioactive compounds in white grape pomace. Food Chem. 2015, 183, 78–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo-Muñoz, N.; Gómez-Alonso, S.; García-Romero, E.; Gómez, M.V.; Velders, A.H.; Hermosín-Gutiérrez, I. Flavonol 3-O-glycosides in Petit Verdot grapes. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009, 57, 209–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amico, V.; Napoli, E.M.; Renda, A.; Ruberto, G.; Spatafora, C.; Tringali, C. Constituents of Nerello Mascalese pomace. Food Chem. 2004, 88, 599–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H.; Johnson, J.V.; Talcott, S.T. Ellagic acid conjugates in muscadine grapes. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005, 53, 6003–6010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subiría-Cueto, C.R.; Muñoz-Bernal, Ó.A.; Rosa, L.A.D.L.; Wall-Medrano, A.; Rodrigo-García, J.; Martinez-Gonzalez, A.I.; González-Aguilar, G.; Martínez-Ruiz, N.d.R.; Alvarez-Parrilla, E. Adsorption of grape pomace phenolics. Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 42, e41422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruberto, G.; Renda, A.; Daquino, C.; Amico, V.; Spatafora, C.; Tringali, C.; De Tommasi, N. Polyphenols and antioxidant activity of grape pomace extracts. Food Chem. 2007, 100, 203–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, T.O.; Portugal, I.; de ACKodel, H.; Droppa-Almeida, D.; Lima, M.D.S.; Fathi, F.; Oliveira, M.B.P.; de Albuquerque-Júnior, R.L.; Dariva, C.; Souto, E.B. Therapeutic potential of grape pomace extracts. Food Biosci. 2024, 60, 104210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinrod, A.J.; Shah, I.M.; Surek, E.; Barile, D. Grape pomace as modulator of the gut microbiome. Heliyon 2023, 9, e20499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Chen, L.; Wang, Y.; Xu, Z.; Liu, Y.; Yuan, C.; Li, J. Release patterns of dietary fiber-bound polyphenols. Food Chem. X 2025, 29, 102694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirkol, M.; Tarakçi, Z. Fruit juice waste as prebiotic in yogurt. Food Sci. Nutr. 2025, 13, e70612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Wei, Y.; Xiang, R.; Dong, B.; Yang, X. Lactic acid bacteria exopolysaccharides. Foods 2025, 14, 823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kok, J. Genetics of the proteolytic system of lactic acid bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 1990, 87, 15–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verni, M.; Verardo, V.; Rizzello, C.G. Effect of fermentation on antioxidant properties. Foods 2019, 8, 362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, M.; Xiao, X.; Jin, D.; Zhai, L.; Li, Y.; Yang, Q.; Xing, F.; Qiao, W.; Yan, X.; Tang, Q. Composition and biological activity of colored rice. Foods 2025, 14, 1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vakhariya, R.R.; Mohite, S.K.; Narde, K.J. Grape pomace phenolic composition. J. Clin. Biomed. Sci. 2025, 15, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filannino, P.; Di Cagno, R.; Gobbetti, M. Metabolic and functional roles of lactic acid bacteria in plants. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2018, 49, 64–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franchin, M.; de Lima Xavier, B.T.; Guo, Y.; Luo, L.; Wang, K.; Granato, D. Standardisation of human plasma oxidation assay. Food Res. Int. 2025, 218, 116951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pontonio, E.; Verni, M.; Dingeo, C.; Diaz-de-Cerio, E.; Pinto, D.; Rizzello, C.G. Impact of enzymatic and microbial bioprocessing on antioxidant properties of hemp (Cannabis sativa L.). Antioxidants 2020, 9, 1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merecz-Sadowska, A.; Sitarek, P.; Zajdel, K.; Kucharska, E.; Kowalczyk, T.; Zajdel, R. The modulatory influence of plant-derived compounds on human keratinocyte function. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 12488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, J.Y.; Yan Ng, X.M.G.; Wong, Q.Y.A.; Chew, F.T. Dietary interventions in skin ageing: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Physiol. Anthropol. 2025, 44, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhan, M. The Promising Role of Polyphenols in Skin Disorders. Molecules 2024, 29, 865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dichi, I.; Breganó, J.W.; Cecchini, R. Role of Oxidative Stress in Chronic Diseases; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2014; ISBN 9781482216813. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, J.; Ren, X.; Simpkins, J.W. Upregulation of SOD2 and HO-1 by tBHQ. Mol. Pharmacol. 2015, 88, 437–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, P.T.; Chen, C.L.; Ohanyan, V.; Luther, D.J.; Meszaros, J.G.; Chilian, W.M.; Chen, Y.R. Overexpressing SOD2 enhances mitochondrial function. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2015, 88, 14–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishihara, Y.; Takemoto, T.; Itoh, K.; Ishida, A.; Yamazaki, T. Dual role of SOD2 in activated microglia. J. Biol. Chem. 2015, 290, 22805–22817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, B.; Wang, L.; Yang, S.; Liang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, X.; Pan, X.; Li, J. Pyrogallol protects against influenza A virus injury. MedComm 2024, 5, e531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.; Boeren, S.; Miro Estruch, I.; Rietjens, I.M. Pyrogallol as potent Nrf2 inducer. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| LAB (cfu/g) | pH | TTA (mL) | Lactic Acid (mmol/kg) | Acetic Acid (mmol/kg) | TFAA (mg/kg) | TPC (mmol GAE/kg) | DPPH (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| tf | ||||||||

| G-Ct | 2.70 ± 0.12 Bb | 6.07 ± 0.09 Aa | 1.8 ± 0.03 Bc | 0.66 ± 0.02 Bc | 0.15 ± 0.01 Bc | 427 ± 20 Aa | 756 ± 3.63 Ac | 40.1 ± 2.26 Ac |

| G-DSM | 8.96 ± 0.41 Aa | 4.37 ± 0.03 Ab | 4.6 ± 0.14 Ba | 14.80 ± 0.58 Ba | 0.69 ± 0.02 Bb | 269 ± 12 Bc | 828 ± 2.24 Aa | 58.8 ± 1.44 Aa |

| G-SP1 | 8.56 ± 0.25 Aa | 4.79 ± 0.10 Ab | 3.4 ± 0.23 Cb | 11.49 ± 0.61 Bb | 0.59 ± 0.03 Bb | 394 ± 14 Ba | 803 ± 0.13 Ab | 50.5 ± 1.21 Bab |

| G-T0 A10 | 8.84 ± 0.38 Aa | 4.49 ± 0.05 Ab | 4.2 ± 0.17 Ba | 14.66 ± 0.43 Ba | 1.35 ± 0.07 Ba | 305 ± 5 Cb | 839 ± 1.09 Ba | 56.9 ± 2.93 Ca |

| t7 | ||||||||

| G-Ct | 2.71 ± 0.09 Bc | 5.97 ± 0.11 Aa | 2.0 ± 0.12 Ac | 0.72 ± 0.01 Ac | 0.23 ± 0.02 Ac | 456 ± 23 Aa | 750 ± 1.52 Ac | 38.3 ± 3.57 Ad |

| G-DSM | 8.95 ± 0.31 Aa | 4.23 ± 0.10 Ac | 5.4 ± 0.11 Aa | 15.98 ± 0.75 Aa | 0.71 ± 0.09 Ab | 294 ± 18 ABc | 832 ± 1.04 ABa | 62.2 ± 1.34 Ab |

| G-SP1 | 8.29 ± 0.14 Ab | 4.53 ± 0.03 Bb | 3.7 ± 0.07 Bb | 12.91 ± 0.34 Ab | 0.81 ± 0.05 Ab | 408 ± 33 ABab | 807 ± 2.93 Ab | 53.7 ± 3.29 Bc |

| G-T0A10 | 9.07 ± 0.42 Aa | 4.34 ± 0.09 Ac | 5.2 ± 0.14 Aa | 15.17 ± 0.29 Aa | 1.91 ± 0.21 Aa | 358 ± 12 Bb | 847 ± 4.14 Ba | 69.2 ± 1.23 Ba |

| t14 | ||||||||

| G-Ct | 3.06 ± 0.07 Ab | 5.78 ± 0.05 Ba | 2.3 ± 0.09 Ad | 0.81 ± 0.03 Ac | 0.32 ± 0.01 Ac | 437 ± 9 Aa | 755 ± 0.25 Ac | 36.3 ± 2.16 Ac |

| G-DSM | 8.85 ± 0.11 Ba | 3.98 ± 0.07 Bd | 6.0 ± 0.37 Aa | 16.22 ± 0.11 Aa | 0.73 ± 0.10 Ab | 325 ± 3 Ab | 838 ± 2.24 Aa | 65.3 ± 1.89 Ab |

| G-SP1 | 8.18 ± 0.72 Aa | 4.56 ± 0.17 Bb | 4.1 ± 0.19 Ac | 13.45 ± 0.61 Ab | 0.84 ± 0.05 Ab | 451 ± 14 Aa | 799 ± 2.79 Ab | 67.2 ± 1.07 Ab |

| G-T0A10 | 8.92 ± 0.49 Aa | 4.23 ± 0.04 Bc | 5.2 ± 0.13 Ab | 15.36 ± 0.37 Ab | 1.89 ± 0.17 Aa | 427 ± 20 Aa | 887 ± 0.08 Aa | 77.9 ± 2.58 Aa |

| L* | a* | b* | ΔE* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| G-Ct | 42.5 ± 0.9 a | −0.42 ± 0.09 c | 1.82 ± 0.22 a | 42.4 ± 1.01 a |

| G-DSM | 42.0 ± 0.31 a | 1.30 ± 0.23 ab | 1.91 ± 0.12 a | 42.5 ± 0.29 a |

| G-SP1 | 42.7 ± 0.4 a | 0.41 ± 0.22 b | 1.86 ± 0.13 a | 42.8 ± 0.31 a |

| G-T0A10 | 41.4 ± 0.3 a | 2.19 ± 0.49 a | 1.97 ± 0.13 a | 42.2 ± 0.51 a |

| Phenolic Compound | G-Ct | G-T0A10 |

|---|---|---|

| Gallic acid | 14.1 ± 2.7 a | 6.0 ± 0.3 b |

| Pyrogallol | n.d. | 4.4 ± 0.8 a |

| Syringol | 0.9 ± 0.1 a | n.d. |

| Protocatechuic acid | 0.7 ± 0.1 a | n.d. |

| Protocatechuic acid isomer II | 8.2 ± 1.3 a | 4.0 ± 0.1 b |

| Caftaric acid | 1.9 ± 0.4 a | n.d. |

| Methyl gallate | 3.3 ± 0.5 a | 3.9 ± 0.1 a |

| Hydroxybenzoic acid | 11.1 ± 2.3 a | 9.9 ± 3.9 a |

| Hydroxybenzoic acid isomer II | 1.0 ± 0.1 a | n.d. |

| Proanthocyanidin B1 | 8.8 ± 0.2 b | 14.3 ± 1.4 a |

| Caffeoyl glucose | 7.1 ± 0.9 a | 5.0 ± 0.6 a |

| (+)-Catechin | 70.9 ± 0.9 b | 99.3 ± 8.8 a |

| Caffeoyl glucose isomer | 5.2 ± 0.6 a | 5.0 ± 0.0 a |

| Fertaric acid | 2.3 ± 0.5 a | n.d. |

| Proanthocyanidin B1 isomer II | 1.8 ± 0.5 a | n.d. |

| p-Coumaric acid glucoside | 12.2 ± 2.9 b | 16.2 ± 0.4 a |

| Proanthocyanidin B1 isomer III | 10.3 ± 0.4 b | 12.1 ± 0.6 a |

| Syringic acid | 6.3 ± 0.7 a | 3.7 ± 0.2 b |

| Protocatechuic acid isomer III | 4.7 ± 0.1 b | 8.8 ± 1.6 a |

| p-Coumaric acid glucoside isomer II | 13.6 ± 4.3 a | 11.8 ± 6.2 a |

| (−)-epicatechin isomer II | 45.0 ± 1.5 b | 59.7 ± 0.6 a |

| p-Coumaric acid | 1.6 ± 0.1 a | n.d. |

| Syringic acid isomer II | 15.3 ± 2.4 a | 10.4 ± 0.2 b |

| Proanthocyanidin B1 gallate | 3.0 ± 0.0 b | 4.4 ± 1.3 a |

| Proanthocyanidin B1 isomer IV | 0.3 ± 0.2 a | n.d. |

| Myricetin glucuronide | 1.8 ± 0.5 a | 1.5 ± 0.2 a |

| p-Coumaric acid isomer II | 1.8 ± 0.5 a | 1.3 ± 0.4 a |

| Hydroxybenzoic acid isomer II | 3.2 ± 0.1 a | 3.0 ± 0.3 a |

| Malvidin glucoside pyruvic acid | 0.7 ± 0.1 a | 1.1 ± 0.3 a |

| Epicatechin gallate | 1.6 ± 0.0 b | 3.4 ± 0.5 a |

| Ellagic acid | 1.2 ± 0.7 a | 0.9 ± 0.4 a |

| Isoquercitrin | 3.0 ± 0.6 a | 2.5 ± 0.5 a |

| Quercetin glucuronide | 46.2 ± 1.9 a | 36.5 ± 2.3 b |

| Isoquercitrin isomer II | 6.5 ± 1.0 a | 5.1 ± 0.8 a |

| Eriodictyol | 0.6 ± 0.1 a | 0.8 ± 0.1 a |

| Isorhamnetin galactoside | 0.5 ± 0.0 a | n.d. |

| Isorhamnetin galactoside isomer II | 9.0 ± 1.0 a | 7.2 ± 0.9 a |

| Syringetin glucoside | 18.0 ± 1.5 a | 16.7 ± 1.8 a |

| Quercetin | 2.4 ± 0.0 a | 5.7 ± 1.2 b |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Torreggiani, A.; Caponio, M.; Pinto, D.; Mondadori, G.; Verardo, V.; Gómez-Caravaca, A.M.; Verni, M.; Rizzello, C.G. Upcycling Grape Pomace in a Plant-Based Yogurt Alternative: Starter Selection, Phenolic Profiling, and Antioxidant Efficacy on Human Keratinocytes. Foods 2025, 14, 4294. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244294

Torreggiani A, Caponio M, Pinto D, Mondadori G, Verardo V, Gómez-Caravaca AM, Verni M, Rizzello CG. Upcycling Grape Pomace in a Plant-Based Yogurt Alternative: Starter Selection, Phenolic Profiling, and Antioxidant Efficacy on Human Keratinocytes. Foods. 2025; 14(24):4294. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244294

Chicago/Turabian StyleTorreggiani, Andrea, Mario Caponio, Daniela Pinto, Giorgia Mondadori, Vito Verardo, Ana María Gómez-Caravaca, Michela Verni, and Carlo Giuseppe Rizzello. 2025. "Upcycling Grape Pomace in a Plant-Based Yogurt Alternative: Starter Selection, Phenolic Profiling, and Antioxidant Efficacy on Human Keratinocytes" Foods 14, no. 24: 4294. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244294

APA StyleTorreggiani, A., Caponio, M., Pinto, D., Mondadori, G., Verardo, V., Gómez-Caravaca, A. M., Verni, M., & Rizzello, C. G. (2025). Upcycling Grape Pomace in a Plant-Based Yogurt Alternative: Starter Selection, Phenolic Profiling, and Antioxidant Efficacy on Human Keratinocytes. Foods, 14(24), 4294. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244294