Effects of Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction on Yield, Physicochemical Properties, and Structural Characterization of Rosa laevigata Polysaccharides: A Comparative Analysis with Five Conventional Methods

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Reagents

2.2. Material Preparation

2.3. Extraction Method of Polysaccharide from R. laevigata Michx

2.3.1. Hot Water Extraction (HAE)

2.3.2. Microwave-Assisted Extraction (MAE)

2.3.3. Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction (UAE)

2.3.4. Acid Extraction (FTACP)

2.3.5. Alkali Extraction (FTAIP)

2.3.6. Enzyme-Assisted Extraction (EAE)

2.4. Determination of Polysaccharide Yield

2.5. Determination of Physicochemical Indices

2.5.1. Oil Absorption Capacity

2.5.2. Foaming Capacity and Foam Stability

2.6. Determination of Cholesterol Adsorption Capacity

2.7. Determination of Antioxidant Activity

2.7.1. DPPH Radical Scavenging Capacity

2.7.2. ABTS Radical Scavenging Capacity

2.7.3. Ferric Ion Reducing Antioxidant Power (FRAP)

2.8. Determination of Structural Characterization

2.8.1. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FT-IR)

2.8.2. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

2.8.3. Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA)

2.8.4. X-Ray Diffraction (XRD) Analysis

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

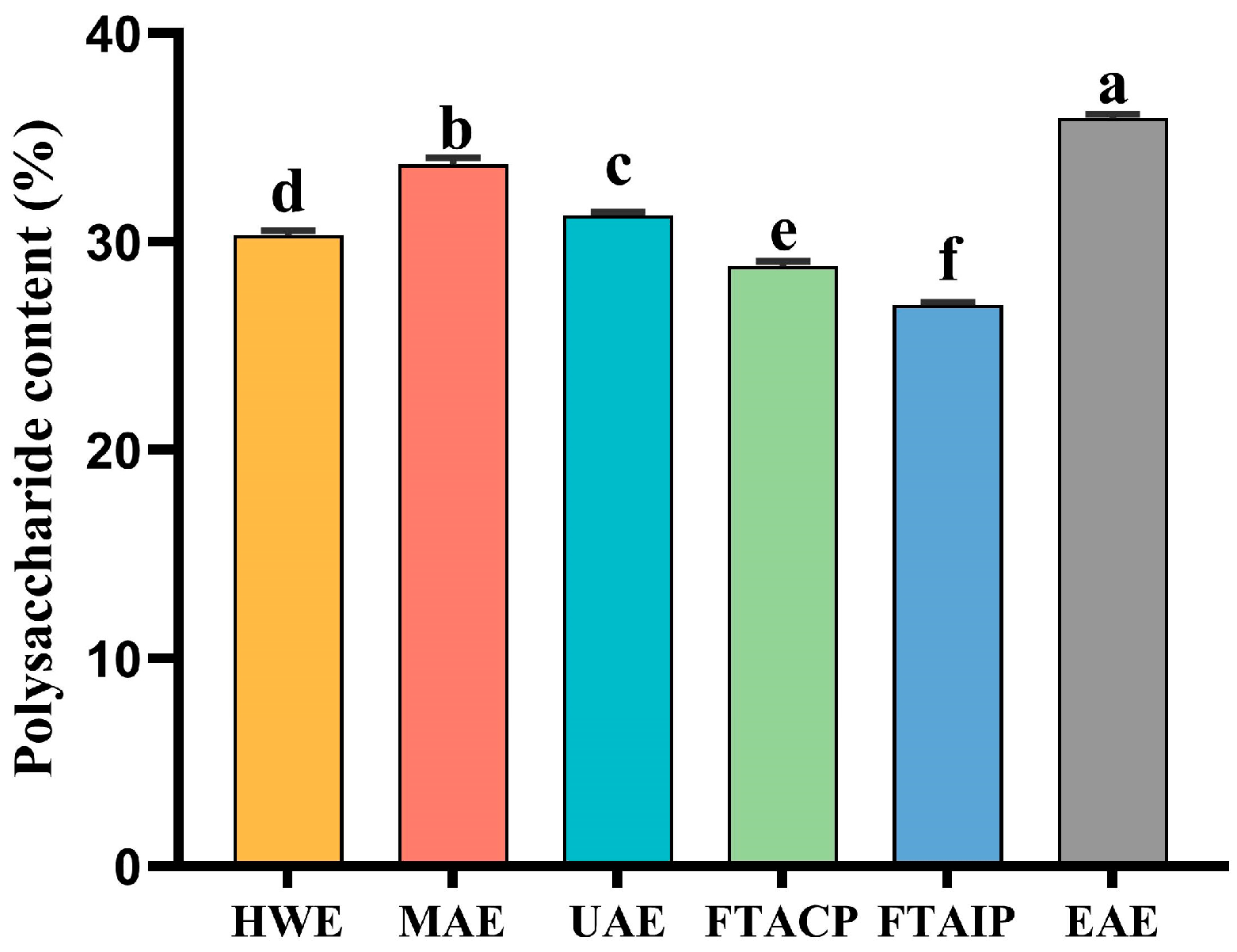

3.1. Analysis of Polysaccharide Yield

3.2. Analysis of Physicochemical Indices

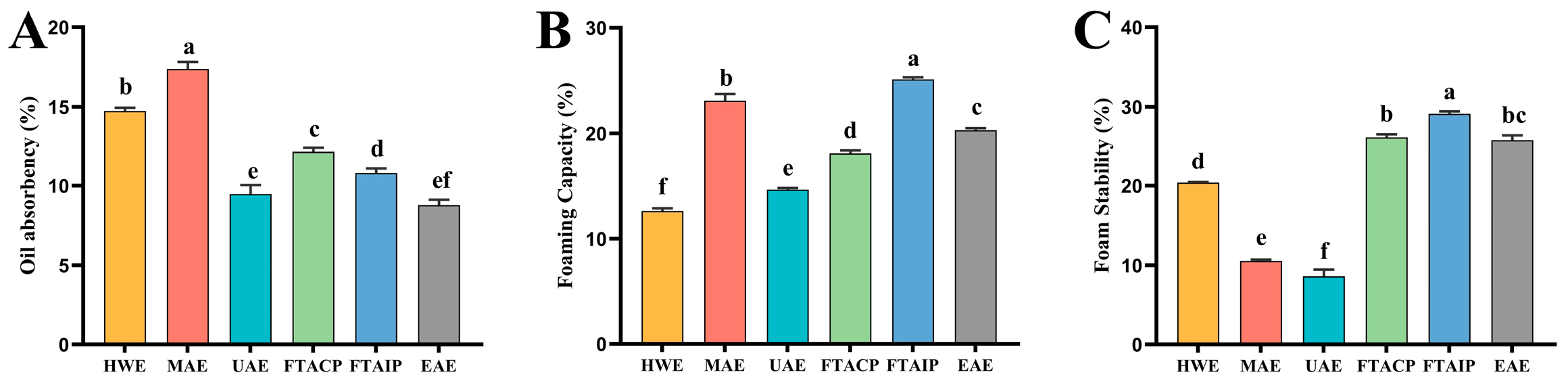

3.2.1. Analysis of Oil Absorption Capacity

3.2.2. Analysis of Foaming Capacity and Foam Stability

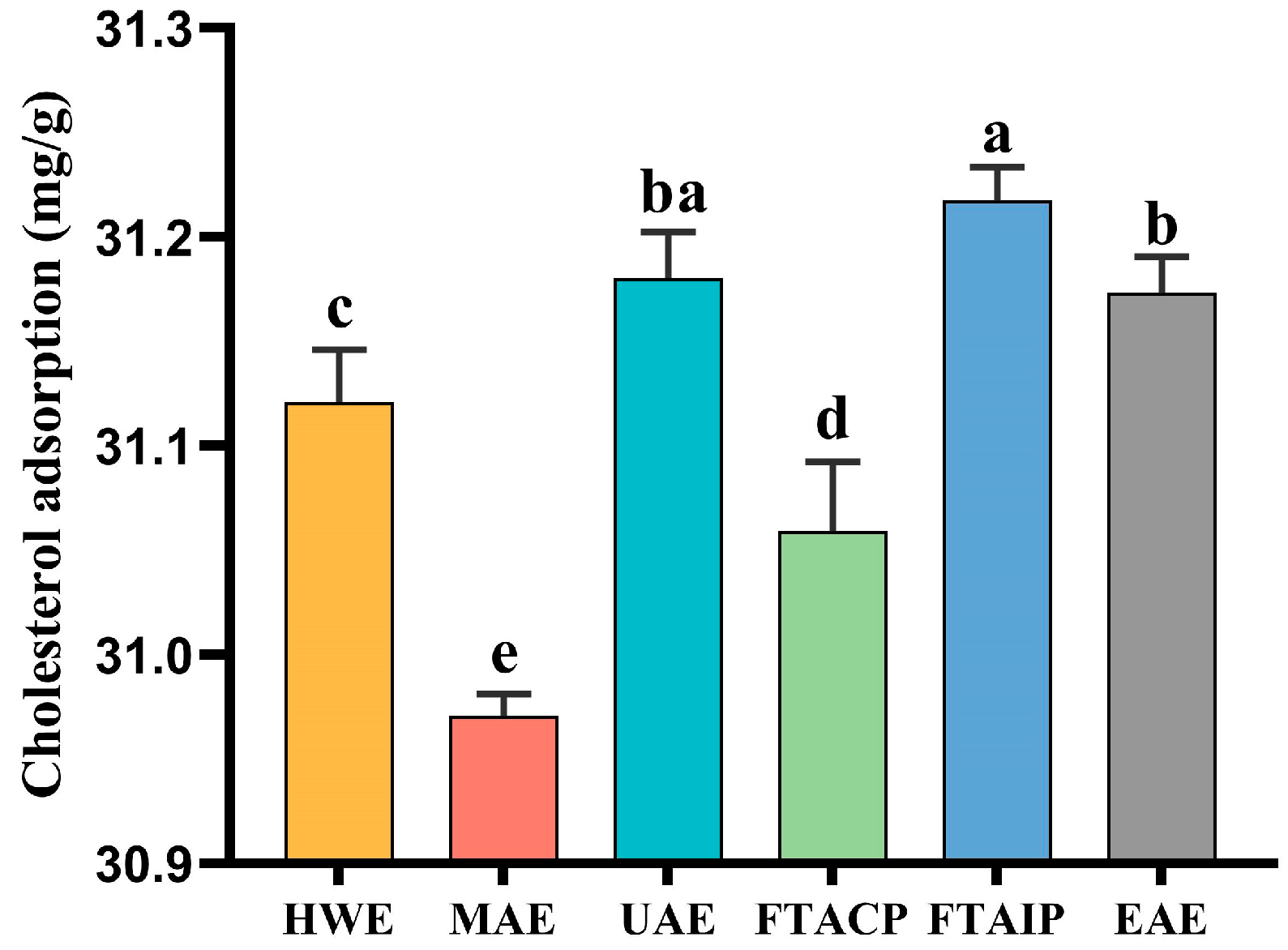

3.3. Analysis of Cholesterol Adsorption Capacity

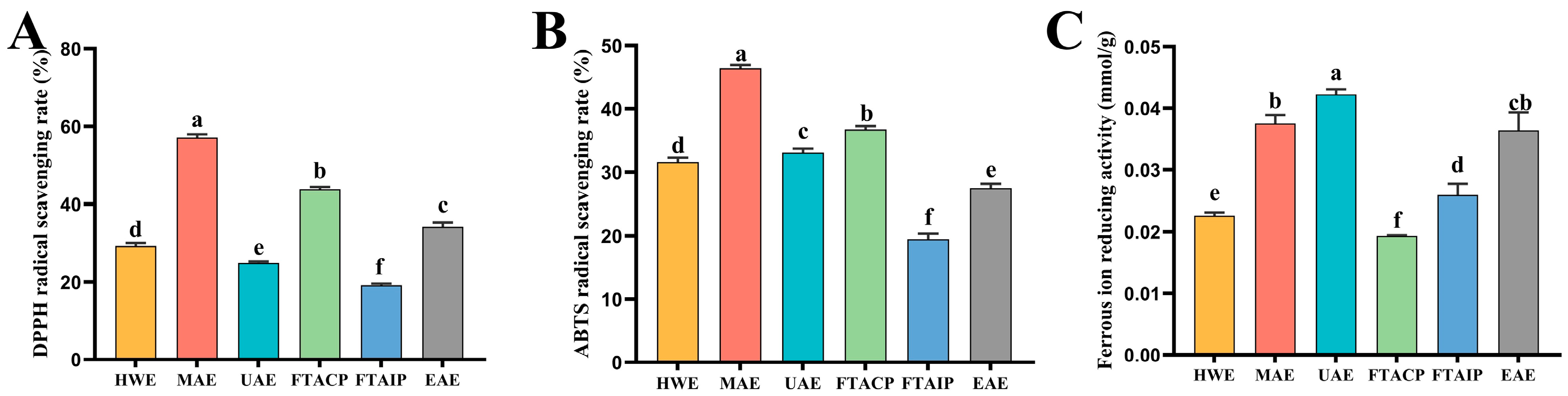

3.4. Analysis of Antioxidant Activity

3.5. Analysis of Structural Characterization

3.5.1. Analysis of FT-IR

3.5.2. Analysis of SEM

3.5.3. Analysis of TGA

3.5.4. Analysis of XRD

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yin, X.; Liao, B.; Guo, S.; Liang, C.; Pei, J.; Xu, J.; Chen, S. The chloroplasts genomic analyses of Rosa laevigata, R. rugosa and R. canina. Chin. Med. 2020, 15, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, D.; Qi, Y.; Xu, L.; Yin, L.; Xu, Y.; Han, X.; Zhao, Y.; Peng, J. Total saponins from Rosa laevigata Michx fruit attenuates hepatic steatosis induced by high-fat diet in rats. Food Funct. 2014, 5, 3065–3075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, P.; Han, T.; Jin, M.; Li, D.; Jiang, F.; Zhang, L.; Liu, X. Extraction and isolation of polyhydroxy triterpenoids from Rosa laevigata Michx. fruit with anti-acetylcholinesterase and neuroprotection properties. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 38131–38139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Wang, L.; Rong, S.; Duan, Y.; Wang, H. Extraction, purification, chemical characterization, and in vitro hypoglycemic activity of polysaccharides derived from Rosa laevigata Michx. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 279, 135116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Zhang, C.; Xu, Y.; Ma, M.; Yao, T.; Sui, Z. Impact of six extraction methods on molecular composition and antioxidant activity of polysaccharides from young hulless barley leaves. Foods 2023, 12, 3381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, X.X.; Huang, Y.Y.; Chen, L.; Yuan, J.Q. Traditional uses, phytochemical, pharmacology, quality control and modern applications of two important Chinese medicines from Rosa laevigata Michx.: A review. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 1012265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.H.; Dai, X.Y.; Chen, Q.; Zang, J.N.; Deng, L.L.; Liu, Y.H.; Ying, H.Z. Hypolipidemic and antioxidant activities of polysaccharides from Rosae Laevigatae Fructus in rats. Carbohydr. Polym. 2013, 94, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Yan, X.; Liang, J.; Li, S.; He, H.; Xiong, Q.; Lai, X.; Hou, S.; Huang, S. Comparison of different extraction methods for polysaccharides from Dendrobium officinale stem. Carbohydr. Polym. 2018, 198, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Shi, Y.; Liu, Y.; Ma, Y.; Lin, C.; Nie, N.; Song, X.; Yang, J. Physicochemical properties of soluble dietary fiber from passion fruit peel based on various extraction methods. Agriculture 2024, 15, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Fang, C.; Ran, C.; Tan, Y.; Yu, Q.; Kan, J. Comparison of different extraction methods for polysaccharides from bamboo shoots (Chimonobambusa quadrangularis) processing by-products. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 130, 903–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geng, X.; Guo, D.; Wu, B.; Wang, W.; Zhang, D.; Hou, S.; Bau, T.; Lei, J.; Xu, L.; Cheng, Y.; et al. Effects of different extraction methods on the physico-chemical characteristics and biological activities of polysaccharides from Clitocybe squamulosa. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 259, 129234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Yang, J.; Pan, S.; Zeng, C.; Guo, R.; Li, X.; Song, X.; Yang, J.; Song, Y. Quality characteristics of Cornus officinalis Sieb. et Zucc. polysaccharides extracted by different methods. J. South. Agric. 2024, 55, 2031–2043. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, H.; Zhang, P.; Zhang, C.; Gao, Y.; Tan, J. Research progress in the preparation, structural characterization, and biological activities of polysaccharides from traditional Chinese medicine. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 262, 129923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, X.; Sun, X.; Xu, L.; Yin, L.; Han, X.; Qi, Y.; Xu, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, C.; Peng, J. Total flavonoids from Rosa laevigata Michx fruit ameliorates hepatic Ischemia/Reperfusion injury through inhibition of oxidative stress and inflammation in rats. Nutrients 2016, 8, 418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chirumbolo, S. Hormetic effect of Rosa laevigata Michx in CCl4-induced hepatotoxicity and the presumptive role of PPARs. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2013, 57, 387–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Ma, Y.; Xu, X.; Huang, G.; Zhang, R.; Jia, X.; Dong, L.; Deng, M.; Zhang, M.; Huang, F. Comparison of different longan polysaccharides during gut Bacteroides fermentation. Food Chem. 2024, 461, 140840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, Q.; Wang, Q.; Lin, R.; He, P.; Lai, F.; Zhang, M.; Wu, H. Structural characterization and immunomodulatory activity of a novel acid polysaccharide isolated from the pulp of Rosa laevigata Michx fruit. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 145, 1080–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rostami, H.; Gharibzahedi, S.M. Microwave-assisted extraction of jujube polysaccharide: Optimization, purification and functional characterization. Carbohydr. Polym. 2016, 143, 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jooyandeh, H.; Noshad, M.; Khamirian, R.A. Modeling of ultrasound-assisted extraction, characterization and in vitro pharmacological potential of polysaccharides from Vaccinium arctostaphylos L. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 107, 938–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, Y.R.; Sung, S.K.; Jang, M.; Lim, T.G.; Cho, C.W.; Han, C.J.; Hong, H.D. Enzyme-assisted extraction, chemical characteristics, and immunostimulatory activity of polysaccharides from Korean ginseng (Panax ginseng Meyer). Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 116, 1089–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ktari, N.; Feki, A.; Trabelsi, I.; Triki, M.; Maalej, H.; Slima, S.B.; Nasri, M.; Ben, A.I.; Ben, S.R. Structure, functional and antioxidant properties in Tunisian beef sausage of a novel polysaccharide from Trigonella foenum-graecum seeds. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017, 98, 169–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB 5009.128-2016; National Food Safety Standard—Determination of Cholesterol in Foods. Standards Press of China: Beijing, China, 2016.

- Soh, H.S.; Kim, C.S.; Lee, S.P. A new in vitro assay of cholesterol adsorption by food and microbial polysaccharides. J. Med. Food 2003, 6, 225–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Nan, S.; Qiu, C.; Song, C.; Wu, B.; Tang, Y.; Cheng, L.; Ma, H. Ultrasound-assisted enzymatic extraction of jujube (Ziziphus jujuba Mill.) polysaccharides: Extraction efficiency, antioxidant activity, and structure features. Ultrason. Sonochem 2024, 111, 107088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Zhang, Z.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, L.; Wang, S.; He, Y.; Liu, J.; Zhu, D.; Liu, H. Effects of different enzyme extraction methods on the properties and prebiotic activity of soybean hull polysaccharides. Heliyon 2022, 8, e11053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, L.; Zhu, P.; Wang, W.; Wang, M. The influence of extraction pH on the chemical compositions, macromolecular characteristics, and rheological properties of polysaccharide: The case of okra polysaccharide. Food Hydrocolloid 2020, 102, 105586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, M.; Feng, M.; Chen, Y.; Li, S.; Fang, Z.; Wang, L.; Lin, D.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, Y.; Luo, Y.; et al. Comparison on structure, properties and functions of pomegranate peel soluble dietary fiber extracted by different methods. Food Chem. X 2023, 19, 100827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Dou, Z.; Duan, Q.; Chen, C.; Liu, R.; Jiang, Y.; Yang, B.; Fu, X. A comparison study on structure-function relationship of polysaccharides obtained from sea buckthorn berries using different methods: Antioxidant and bile acid-binding capacity. Food Sci. Hum. Wellness 2024, 13, 494–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Li, Y.; Dong, H.; Liu, Z.; Li, S.; Yang, S.; Li, X. Optimization of ultrasonic extraction process of polysaccharides from Ornithogalum Caudatum Ait and evaluation of its biological activities. Ultrason. Sonochem 2012, 19, 1160–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, N.; Li, Q. Study on extraction and antioxidant activity of polysaccharides from Radix Bupleuri by natural deep eutectic solvents combined with ultrasound-assisted enzymolysis. Sustain. Chem. Pharm. 2022, 30, 100877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Zheng, H.; Zheng, T.; Xu, P.; Xu, Y.; Cao, Y.; Jia, F.; Zeng, Y.; Fan, Y.; He, K.; et al. Adsorption, in vitro digestion and human gut microbiota regulation characteristics of three Poria cocos polysaccharides. Food Sci. Hum. Wellness 2024, 13, 1685–1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; He, X.; Liu, G.; Wei, Z.; Sheng, J.; Sun, J.; Li, C.; Xin, M.; Li, L.; Yi, P. Effects of different extraction methods on the structural, antioxidant and hypoglycemic properties of red pitaya stem polysaccharide. Food Chem. 2023, 405, 134804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.Y.; Zhou, T.; Shabbir, I.; Choi, J.; Kim, Y.H.; Park, M.; Aweya, J.J.; Tan, K.; Zhong, S.; Cheong, K.L. Marine algal polysaccharides: Multifunctional bioactive ingredients for cosmetic formulations. Carbohydr. Polym. 2025, 353, 123276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.; Zhao, J.; Lv, M.; Li, X.; Wang, J.; Yue, Z.; Shi, J.; Zhang, G.; Sui, G. Comparative study of structural properties and biological activities of polysaccharides extracted from Chroogomphus rutilus by four different approaches. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 188, 215–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Q.; Zhang, Y.H. Ultrasound-assisted polysaccharide extraction from Cercis chinensis and properites, antioxidant activity of polysaccharide. Ultrason. Sonochem 2023, 96, 106422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallo, M.; Ferrara, L.; Naviglio, D. Application of ultrasound in food science and technology: A perspective. Foods 2018, 7, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Wang, L.; Ruan, Y.; Wen, C.; Ge, M.; Qian, Y.; Ma, B. Physicochemical properties and biological activities of polysaccharides from the peel of Dioscorea opposita Thunb. extracted by four different methods. Food Sci. Hum. Wellness 2023, 12, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, Q.; Wang, F.; Wang, L.; Xiong, L.; Shen, X. Extraction optimization, purification, characterization, and hypolipidemic activities of polysaccharide from pumpkin. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 307, 141907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, N.; Yang, B.; Mao, K.; Liu, Y.; Chitrakar, B.; Wang, X.; Sang, Y. Comparison of structural characteristics and bioactivity of Tricholoma mongolicu Imai polysaccharides from five extraction methods. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 962584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Li, X.; Miao, J.; Jing, S.; Li, X.; Huang, L.; Gao, W. The effect of different extraction techniques on property and bioactivity of polysaccharides from Dioscorea hemsleyi. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017, 102, 847–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarah, M.; Madinah, I.; Misran, E.; Fatimah. Optimization of microwave-assisted hydrolysis of glucose from oil palm empty fruit bunch. S. Afr. J. Chem. Eng. 2025, 51, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.; Zheng, Z.; Han, X.; Chen, Y.; Liu, H.; Yang, L.; Wu, M. Effects of different extraction methods on the molecular composition and biological activities of polysaccharides from Pleione yunnanensis. Molecules 2025, 30, 1942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Z.; Yuan, R.; Yang, J.; Pan, Y. Hydrogen sulfide delays softening of banana fruit by inhibiting cell wall polysaccharides disassembly. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 58, 5236–5246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Wei, Z.; He, X.; Ling, D.; Qin, M.; Yi, P.; Liu, G.; Li, L.; Li, C.; Sun, J. A comparison study on polysaccharides extracted from banana flower using different methods: Physicochemical characterization, and antioxidant and antihyperglycemic activities. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 264, 130459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shi, Y.; Zuo, X.; Han, Z.; Song, X.; Yang, J.; Song, Y. Effects of Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction on Yield, Physicochemical Properties, and Structural Characterization of Rosa laevigata Polysaccharides: A Comparative Analysis with Five Conventional Methods. Foods 2025, 14, 4275. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244275

Shi Y, Zuo X, Han Z, Song X, Yang J, Song Y. Effects of Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction on Yield, Physicochemical Properties, and Structural Characterization of Rosa laevigata Polysaccharides: A Comparative Analysis with Five Conventional Methods. Foods. 2025; 14(24):4275. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244275

Chicago/Turabian StyleShi, Yunxin, Xiangying Zuo, Ziyu Han, Xuqin Song, Jian Yang, and Ya Song. 2025. "Effects of Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction on Yield, Physicochemical Properties, and Structural Characterization of Rosa laevigata Polysaccharides: A Comparative Analysis with Five Conventional Methods" Foods 14, no. 24: 4275. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244275

APA StyleShi, Y., Zuo, X., Han, Z., Song, X., Yang, J., & Song, Y. (2025). Effects of Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction on Yield, Physicochemical Properties, and Structural Characterization of Rosa laevigata Polysaccharides: A Comparative Analysis with Five Conventional Methods. Foods, 14(24), 4275. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244275