Modulating Protein Glycation in Skim Milk Powder via Low Humidity Dry Heating to Improve Its Heat-Stabilizing Properties

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Dry Heat Treatment of SMP

2.3. Colour Development

2.4. Determination of Total HMF

2.5. Protein Solubility of SMP

2.6. Determination of Free Sulfhydryl Group (-SH) in SMP

2.7. Protein Carbonyl Content in SMP

2.8. Heat Stability of RFEM Emulsions

2.8.1. Preparation of RFEM Emulsions

2.8.2. Heat Stability Test

2.8.3. Particle Size and Viscosity Measurement

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Colour Development

3.2. Development of HMF

3.3. Protein Solubility of Dry-Heat-Treated SMP Dispersion

3.4. Sulfhydryl Group Content

3.5. Protein Carbonyl Group Content

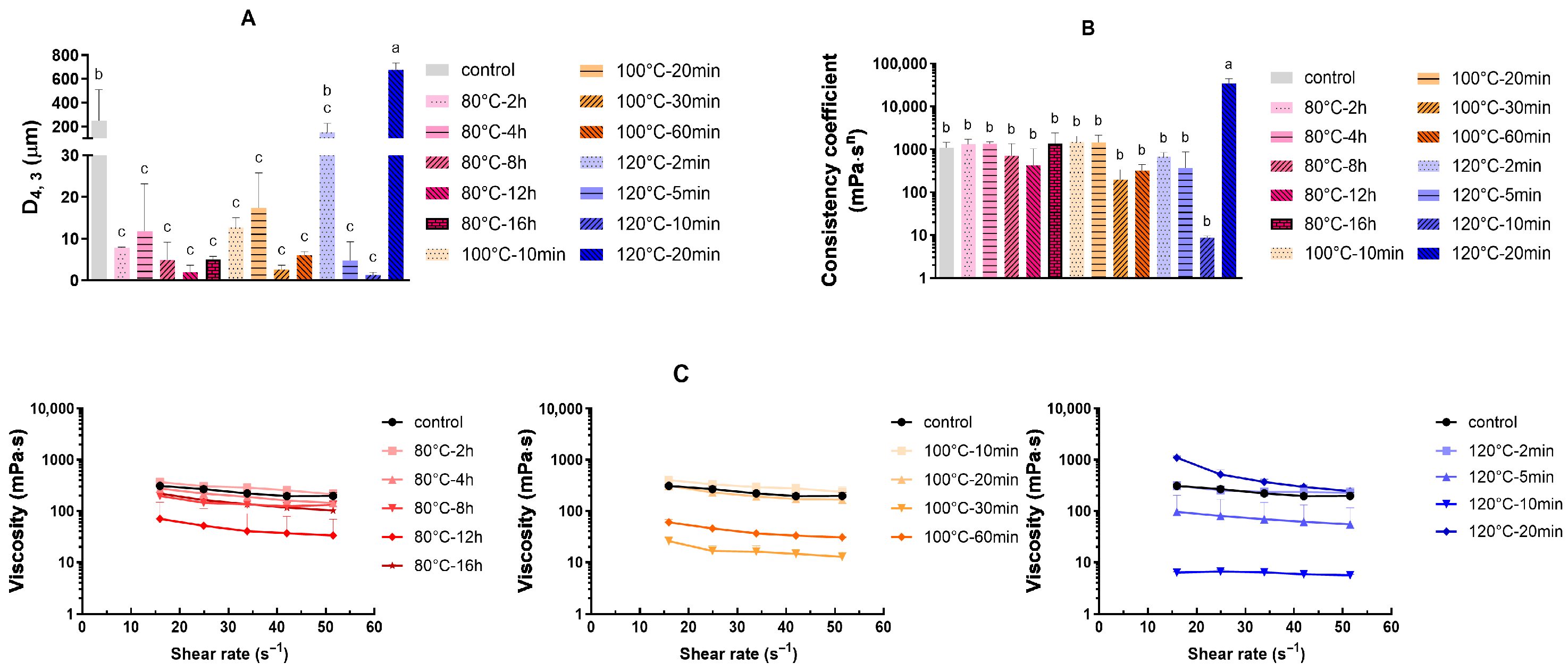

3.6. Heat Stability of RFEM

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MR | Maillard reaction |

| MRPs | Maillard reaction products |

| AGEs | Advanced glycation end-products |

| SMP | Skim milk powder |

| RH | Relative humidity |

| RFEM | Recombined filled evaporated milk |

| HMF | Hydroxymethylfurfural |

References

- Jensen, G.K.; Nielsen, P. Reviews of the progress of dairy science: Milk powder and recombination of milk and milk products. J. Dairy Res. 1982, 49, 515–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.F.; Chen, S.M.; Doost, A.S.; Ayun, Q.; Van der Meeren, P. Dry heat treatment of skim milk powder greatly improves the heat stability of recombined evaporated milk emulsions. Food Hydrocoll. 2021, 112, 106342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.F.; Li, H.; A’yun, Q.; Doost, A.S.; De Meulenaer, B.; Van der Meeren, P. Conjugation of milk proteins and reducing sugars and its potential application in the improvement of the heat stability of (recombined) evaporated milk. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 108, 287–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Zhong, Q. Glycation of whey protein to provide steric hindrance against thermal aggregation. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2012, 60, 9754–9762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lund, M.N.; Ray, C.A. Control of Maillard reactions in foods: Strategies and chemical mechanisms. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2017, 65, 4537–4552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Alvarenga, M.; Martinez-Rodriguez, E.; Garcia-Amezquita, L.; Olivas, G.; Zamudio-Flores, P.; Acosta-Muniz, C.; Sepulveda, D. Effect of Maillard reaction conditions on the degree of glycation and functional properties of whey protein isolate–maltodextrin conjugates. Food Hydrocoll. 2014, 38, 110–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Zhong, Q. High temperature-short time glycation to improve heat stability of whey protein and reduce color formation. Food Hydrocoll. 2015, 44, 453–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loncin, M.; Bimbenet, J.J.; Lenges, J. Influence of the activity of water on the spoilage of foodstuffs. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2007, 3, 131–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phosanam, A.; Chandrapala, J.; Huppertz, T.; Adhikari, B.; Zisu, B. Effect of storage conditions on physicochemical and microstructural properties of skim and whole milk powders. Powder Technol. 2020, 372, 394–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, T.T.; Bhandari, B.; Holland, J.W.; Deeth, H.C. Maillard reaction and protein cross-linking in relation to the solubility of milk powders. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2011, 59, 12473–12479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schacterle, G.R.; Pollack, R.L. A simplified method for the quantitative assay of small amounts of protein in biologic material. Anal. Biochem. 1973, 51, 654–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clare, D.A.; Bang, W.S.; Cartwright, G.; Drake, M.A.; Coronel, P.; Simunovic, J. Comparison of sensory, microbiological, and biochemical parameters of microwave versus indirect UHT fluid skim milk during storage. J. Dairy Sci. 2005, 88, 4172–4182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerkaert, B.; Mestdagh, F.; Cucu, T.; Aedo, P.R.; Ling, S.Y.; De Meulenaer, B. Hypochlorous and peracetic acid induced oxidation of dairy proteins. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2011, 59, 907–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augustyniak, E.; Adam, A.; Wojdyla, K.; Rogowska-Wrzesinska, A.; Willetts, R.; Korkmaz, A.; Atalay, M.; Weber, D.; Grune, T.; Borsa, C.; et al. Validation of protein carbonyl measurement: A multi-centre study. Redox Biol. 2015, 4, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasinos, M.; Karbakhsh, R.R.; Van der Meeren, P. Sensitivity analysis of a small-volume objective heat stability evaluation test for recombined concentrated milk. Int. J. Dairy Technol. 2015, 68, 38–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasinos, M.; Goñi, M.L.; Nguyen, M.T.; Sabatino, P.; Martins, J.C.; Dewettinck, K.; Van der Meeren, P. Effect of hydrolysed sunflower lecithin on the heat-induced coagulation of recombined concentrated milk emulsions. Int. Dairy J. 2014, 38, 187–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Wang, M.; Wang, Y.; Wu, Z.; Yang, J.; Li, H.; Li, H.; Yu, J. Control of the Maillard reaction and secondary shelf-life prediction of infant formula during domestic use. J. Food Sci. 2023, 88, 681–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Jia, X.; Wang, Z.; He, Z.; Zeng, M.; Chen, J. Characterizing changes in Maillard reaction indicators in whole milk powder and reconstituted low-temperature pasteurized milk under different preheating conditions. J. Food Sci. 2022, 87, 193–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lund, P.; Bechshoft, M.R.; Ray, C.A.; Lund, M.N. Effect of processing of whey protein ingredient on Maillard reactions and protein structural changes in powdered infant formula. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2022, 70, 319–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roos, Y.H. Importance of glass transition and water activity to spray drying and stability of dairy powders. Dairy Sci. Technol. 2002, 82, 475–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Supplee, G.; Bellis, B. The solubility of milk powder as affected by moisture content. J. Dairy Sci. 1925, 8, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Considine, T.; Patel, H.A.; Anema, S.G.; Singh, H.; Creamer, L.K. Interactions of milk proteins during heat and high hydrostatic pressure treatments–A review. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2007, 8, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zweig, G.; Block, R.J. The effect of heat treatment on the sulfhydryl groups in skim milk and nonfat dry milk. J. Dairy Sci. 1953, 36, 427–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, J.; Biliaderis, C.G.; Moschakis, T. Whey proteins: Musings on denaturation, aggregate formation and gelation. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 60, 3793–3806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Zhang, J.; Zou, B.; Ren, C.; Na, X.; Xu, X.; Du, M.; Zhu, B.; Wu, C. Mild alkalinity preheating treatment regulates the heat and ionic strength co-tolerance of whey protein aggregates. Food Res. Int. 2024, 193, 114845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.J.; Chen, S.M.; De Meulenaer, B.; Wu, J.F.; van der Meeren, P. Effect of dry heat treatment temperature of skim milk powder on the improved heat stability of recombined filled evaporated milk. Food Hydrocoll. 2025, 166, 111345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenaille, F.; Parisod, V.; Tabet, J.C.; Guy, P.A. Carbonylation of milk powder proteins as a consequence of processing conditions. Proteomics 2005, 5, 3097–3104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.; Chen, S.; Van Damme, E.J.M.; De Meulenaer, B.; Van der Meeren, P. Protein interactions during dry and wet heat pre-treatment of skim milk powder (dispersions) and their effect on the heat stability of recombined filled evaporated milk. Food Chem. 2023, 418, 135974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuinier, R.; De Kruif, C. Stability of casein micelles in milk. J. Chem. Phys. 2002, 117, 1290–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aminlari, M.; Ramezani, R.; Jadidi, F. Effect of Maillard-based conjugation with dextran on the functional properties of lysozyme and casein. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2005, 85, 2617–2624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 80 °C | 100 °C | 120 °C |

|---|---|---|

| 2 h | 10 min | 2 min |

| 4 h | 20 min | 5 min |

| 8 h | 30 min | 10 min |

| 12 h | 60 min | 20 min |

| 16 h |

| Incubation Temperature | 80 °C | 90 °C | 100 °C | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time (h) | K (mPa⋅sn) | n | Time (min) | K (mPa⋅sn) | n | Time (min) | K (mPa⋅sn) | n |

| 2 | 1320 ± 330 | 0.55 ± 0.10 | 0 | 1090 ± 320 | 0.56 ± 0.12 | 0 | 1090 ± 320 | 0.56 ± 0.12 |

| 4 | 1330 ± 140 | 0.43 ± 0.04 | 10 | 1490 ± 450 | 0.55 ± 0.15 | 2 | 673 ± 140 | 0.72 ± 0.11 |

| 8 | 710 ± 530 | 0.49 ± 0.21 | 20 | 1440 ± 580 | 0.46 ± 0.09 | 5 | 370 ± 410 | 0.51 ± 0.03 |

| 12 | 400 ± 500 | 0.43 ± 0.12 | 30 | 199 ± 110 | 0.43 ± 0.07 | 10 | 8.9 ± 0.6 | 0.90 ± 0.01 |

| 16 | 1350 ± 870 | 0.34 ± 0.05 | 60 | 320 ± 99 | 0.41 ± 0.09 | 20 | 34,800 ± 7900 | 0.27 ± 0.04 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhao, Z.; Flores, R.; De Meulenaer, B.; Van der Meeren, P. Modulating Protein Glycation in Skim Milk Powder via Low Humidity Dry Heating to Improve Its Heat-Stabilizing Properties. Foods 2025, 14, 4197. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244197

Zhao Z, Flores R, De Meulenaer B, Van der Meeren P. Modulating Protein Glycation in Skim Milk Powder via Low Humidity Dry Heating to Improve Its Heat-Stabilizing Properties. Foods. 2025; 14(24):4197. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244197

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhao, Zijun, Riza Flores, Bruno De Meulenaer, and Paul Van der Meeren. 2025. "Modulating Protein Glycation in Skim Milk Powder via Low Humidity Dry Heating to Improve Its Heat-Stabilizing Properties" Foods 14, no. 24: 4197. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244197

APA StyleZhao, Z., Flores, R., De Meulenaer, B., & Van der Meeren, P. (2025). Modulating Protein Glycation in Skim Milk Powder via Low Humidity Dry Heating to Improve Its Heat-Stabilizing Properties. Foods, 14(24), 4197. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244197