Effect of Okara Inclusion on Starch Digestibility and Phenolic-Related Health-Promoting Properties of Sorghum-Based Instant Porridges

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation of Sorghum Flour

2.2. Preparation of Okara Flour

2.3. Preparation of Composite Flours

2.4. Instant Porridge Preparation

2.5. In Vitro Starch Digestibility

2.6. Total Phenolic Content (TPC) and Antioxidant Assays

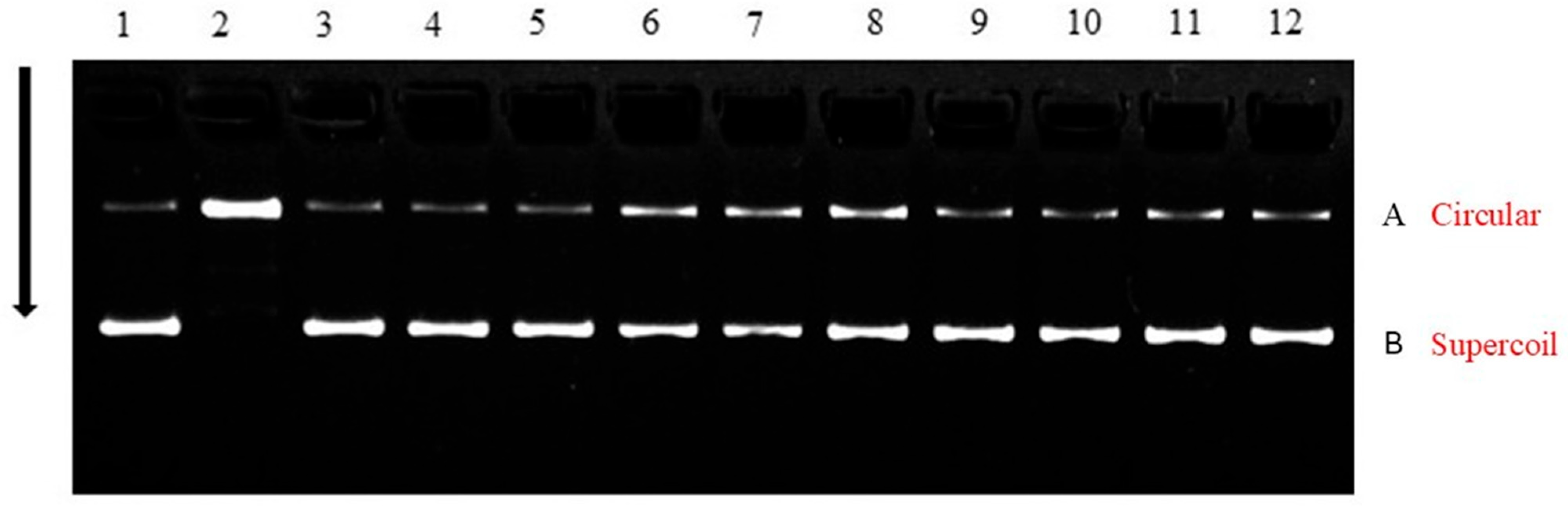

2.7. Inhibition of the Oxidative DNA Damage Assay

2.8. HPLC Analysis

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. In Vitro Starch Digestibility

3.2. Total Phenolic Content and Antioxidant Activities

3.3. Inhibition of DNA Damage

3.4. Phenolic Profiling

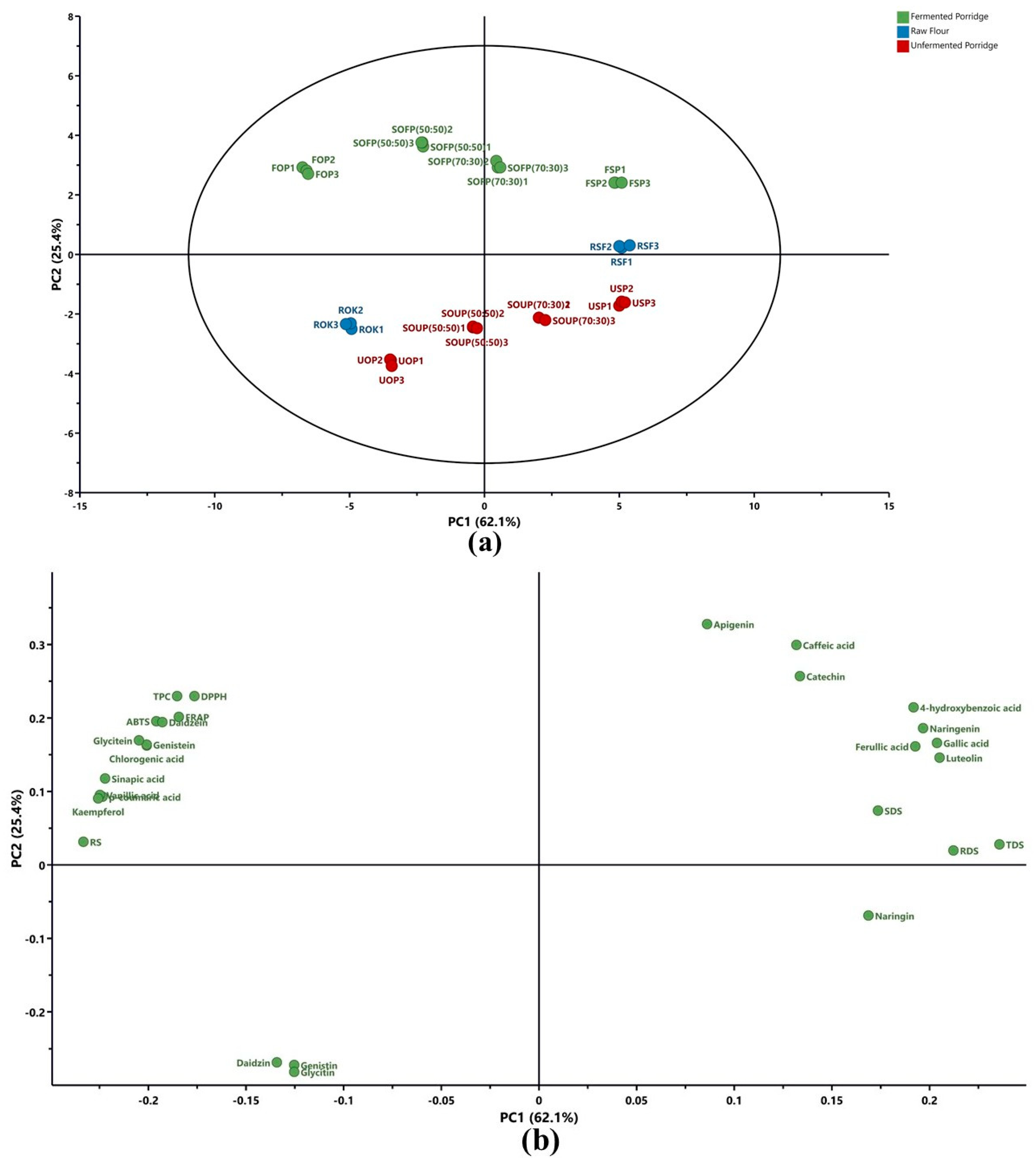

3.5. Principal Component Analysis (PCA)

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- WHO. Noncommunicable Diseases: Key Facts. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/noncommunicable-diseases (accessed on 18 September 2025).

- Tapkigen, J.; Harding, S.; Pulkki, J.; Atkins, S.; Koivusalo, M. Climate change-induced shifts in the food systems and diet-related non-communicable diseases in sub-Saharan Africa: A scoping review and a conceptual framework. BMJ Open 2024, 14, e080241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, J.R.; Duodu, K.G. Resistant-type starch in sorghum foods—Factors involved and health implications. Starch Starke 2023, 75, 2100296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espitia-Hernández, P.; Chavez Gonzalez, M.L.; Ascacio-Valdés, J.A.; Dávila-Medina, D.; Flores-Naveda, A.; Silva, T.; Ruelas Chacon, X.; Sepúlveda, L. Sorghum (Sorghum bicolor L.) as a potential source of bioactive substances and their biological properties. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 62, 2269–2280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, J.; Santana, A.L.; Cox, S.; Perez-Fajardo, M.; Covarrubias, J.; Perumal, R.; Bean, S.; Wu, X.; Wang, W.; Smolensky, D. Impact of heat and high-moisture pH treatments on starch digestibility, phenolic composition, and cell bioactivity in sorghum (Sorghum bicolor L. Moench) flour. Front. Nutr. 2024, 11, 1428542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeyanju, A.A.; Duodu, K.G. Effects of different souring methods on phenolic constituents and antioxidant properties of non-alcoholic gruels from sorghum and amaranth. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 58, 1062–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeyanju, A.A.; Emmanuel, P.O.; Adetunji, A.I.; Adebo, O.A. Nutritional, pasting, rheological, and thermal properties of sorghum–okara composite flours and porridges. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2025, 60, vvae021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, D.; Wu, J.; Yang, Y.; Long, X.; Wu, Z.; Qin, W. The anti-lipidemic role of soluble dietary fiber extract from okara after fermentation and dynamic high-pressure microfluidization treatment to Kunming mice. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 57, 4247–4256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamble, D.B.; Rani, S. Bioactive components, in vitro digestibility, microstructure and application of soybean residue (okara): A review. Legume Sci. 2020, 2, e32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCleary, B.V.; McLoughlin, C.; Charmier, L.M.; McGeough, P. Measurement of available carbohydrates, digestible, and resistant starch in food ingredients and products. Cereal Chem. 2020, 97, 114–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeyanju, A.A.; Adeleye, D.G.; Adejuyitan, J.A.; Ogunbusola, E.; Bamidele, O.P. The in-vitro starch digestibility, pasting and antioxidant properties of the composite flour from cassava root and tigernut seed. CYTA J. Food 2024, 22, 2318343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razola-Díaz, M.D.C.; Gómez-Caravaca, A.M.; Guerra-Hernández, E.J.; Garcia-Villanova, B.; Verardo, V. New advances in the phenolic composition of tiger nut (Cyperus esculentus L.) by-products. Foods 2022, 11, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.-J.; Hyun, J.-N.; Kim, J.-A.; Park, J.-C.; Kim, M.-Y.; Kim, J.-G.; Lee, S.-J.; Chun, S.-C.; Chung, I.-M. Relationship between phenolic compounds, anthocyanins content and antioxidant activity in colored barley germplasm. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2007, 55, 4802–4809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Bean, S.; Wu, X.; Shi, Y.-C. Effects of protein digestion on in vitro digestibility of starch in sorghum differing in endosperm hardness and flour particle size. Food Chem. 2022, 383, 132635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adeyanju, A.A.; Adebo, O.A. Okara-enriched fermented sorghum instant porridge: Effects on mineral bioaccessibility and structural properties. Front. Nutr. 2025, 12, 1690627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Zeng, J.; Hu, J.; Chen, J.; Peng, D.; Du, B.; Li, P. Effects of cooking methods on the physical properties and in vitro digestibility of starch isolated from Chinese yam. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 267, 131597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; McClements, D.J.; Luo, S.; Ye, J.; Liu, C. A review of the effects of fermentation on the structure, properties, and application of cereal starch in foods. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2025, 65, 2323–2342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirkesen-Bicak, H.; Arici, M.; Yaman, M.; Karasu, S.; Sagdic, O. Effect of different fermentation condition on estimated glycemic index, in vitro starch digestibility, and textural and sensory properties of sourdough bread. Foods 2021, 10, 514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madhujith, T.; Amarowicz, R.; Shahidi, F. Phenolic antioxidants in beans and their effects on inhibition of radical-induced DNA damage. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 2004, 81, 691–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Q.-Y.; Zhou, B.; Cai, Y.-J.; Yang, L.; Liu, Z.-L. Synergistic effect of green tea polyphenols with trolox on free radical-induced oxidative DNA damage. Food Chem. 2006, 96, 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nderitu, A.M.; Dykes, L.; Awika, J.M.; Minnaar, A.; Duodu, K.G. Phenolic composition and inhibitory effect against oxidative DNA damage of cooked cowpeas as affected by simulated in vitro gastrointestinal digestion. Food Chem. 2013, 141, 1763–1771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, J.R.; Duodu, K.G. Effects of processing sorghum and millets on their phenolic phytochemicals and the implications of this to the health-enhancing properties of sorghum and millet food and beverage products. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2015, 95, 225–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Parameters | RSF (100%) | ROF (100%) | USP (100%) | UOP (100%) | SOUP (70:30) | SOUP (50:50) | FSP (100%) | FOP (100%) | SOFP (70:30) | SOFP (50:50) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RDS (g/100 g) | 28.06 c ± 1.17 | 2.74 a ± 0.35 | 54.76 f ± 1.41 | 9.96 b ± 0.71 | 43.31 e ± 2.82 | 34.35 d ± 0.70 | 51.03 f ± 1.06 | 1.74 a ± 0.35 | 35.84 d ± 1.41 | 23.90 c ± 0.70 |

| SDS (g/100 g) | 37.73 f ± 1.18 | 8.87 c ± 0.98 | 21.99 e ± 2.46 | 3.73 ab ± 0.35 | 7.72 bc ± 1.06 | 6.72 abc ± 0.35 | 18.92 de ± 0.70 | 2.73 a ± 0.35 | 9.23 c ± 0.36 | 17.45 d ± 1.41 |

| TDS (g/100 g) | 67.99 e ± 1.12 | 11.52 b ± 0.19 | 75.18 f ± 0.71 | 14.69 b ± 0.35 | 53.80 d ± 1.41 | 42.08 c ± 1.06 | 70.23 e ± 0.70 | 4.23 a ± 0.35 | 42.56 c ± 1.75 | 38.36 c ± 1.41 |

| RS (g/100 g) | 12.43 bc ± 0.76 | 38.38 g ± 1.68 | 4.71 a ± 0.40 | 27.15 f ± 1.41 | 15.66 cd ± 0.71 | 22.04 e ± 1.27 | 10.84 b ± 0.15 | 41.21 g ± 1.41 | 20.39 de ± 1.67 | 27.21 f ± 1.41 |

| Parameters | RSF (100%) | ROF (100%) | USP (100%) | UOP (100%) | SOUP (70:30) | SOUP (50:50) | FSP (100%) | FOP (100%) | SOFP (70:30) | SOFP (50:50) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TPC (mgGAE/g) | 4.68 b ± 0.16 | 7.70 e ± 0.20 | 3.92 a ± 0.10 | 6.77 d ± 0.18 | 5.32 c ± 0.05 | 6.27 d ± 0.11 | 6.82 d ± 0.08 | 11.15 g ± 0.23 | 7.83 e ± 0.21 | 9.84 f ± 0.07 |

| DPPH (µmolTE/g) | 28.34 b ± 0.63 | 42.06 e ± 0.99 | 21.23 a ± 0.47 | 37.74 d ± 0.53 | 27.29 b ± 0.43 | 35.45 cd ± 1.73 | 34.06 c ± 1.12 | 54.39 g ± 0.86 | 48.28 f ± 0.55 | 60.22 h ± 0.80 |

| ABTS (µmolTE/g) | 32.61 b ± 1.34 | 53.47 f ± 0.98 | 27.21 a ± 0.45 | 47.68 e ± 1.40 | 33.33 b ± 0.79 | 43.31 d ± 0.59 | 39.03 c ± 0.76 | 63.84 g ± 1.49 | 55.94 f ± 1.34 | 68.33 j ± 0.49 |

| FRAP (µmolTE/g) | 29.12 ab ± 0.94 | 48.34 d ± 0.49 | 25.50 a ± 0.86 | 45.40 d ± 0.70 | 32.50 b ± 0.55 | 39.34 c ± 0.63 | 36.92 c ± 0.43 | 57.33 f ± 1.72 | 52.68 e ± 1.59 | 66.09 g ± 1.22 |

| Phenolic Acid | RSF (100%) | ROF (100%) | USP (100%) | UOP (100%) | SOUP (70:30) | SOUP (50:50) | FSP (100%) | FOP (100%) | SOFP (70:30) | SOFP (50:50) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| p-Coumaric acids | 21.99 b ± 0.96 | 68.44 g ± 2.31 | 14.32 a ± 0.80 | 47.51 ef ± 0.11 | 25.01 b ± 0.11 | 36.89 d ± 0.06 | 31.07 c ± 2.49 | 77.24 h ± 1.68 | 44.96 e ± 0.39 | 52.35 f ± 1.64 |

| 4-hydroxybenzoic acid | 15.16 ef ± 0.79 | 6.02 ab ± 0.29 | 13.71 de ± 0.51 | 4.85 a ± 0.06 | 11.16 c ± 1.13 | 8.28 b ± 0.12 | 16.44 f ± 0.85 | 7.50 b ± 0.42 | 14.69 def ± 0.73 | 12.53 cd ± 0.40 |

| Caffeic acid | 14.59 ef ± 0.59 | 7.82 ab ± 0.64 | 10.91 cd ± 0.20 | 6.45 a ± 0.14 | 9.13 bc ± 0.01 | 7.93 ab ± 0.12 | 16.04 f ± 0.59 | 11.43 d ± 0.02 | 14.40 ef ± 1.22 | 12.84 de ± 0.01 |

| Chlorogenic acid | 2.82 ab ± 0.01 | 4.23 cd ± 0.50 | 2.47 a ± 0.00 | 3.65 bcd ± 0.17 | 2.85 ab ± 0.02 | 3.34 abc ± 0.18 | 3.37 abcd ± 0.10 | 5.63 e ± 0.10 | 3.70 bcd ± 0.25 | 4.40 d ± 0.25 |

| Ferulic acid | 101.47 f ± 2.64 | 54.39 ab ± 1.27 | 82.14 e ± 0.15 | 49.09 a ± 0.14 | 70.81 d ± 1.92 | 53.42 ab ± 0.02 | 122.60 g ± 3.21 | 58.84 bc ± 2.25 | 80.70 e ± 4.79 | 67.51 cd ± 1.26 |

| Gallic acid | 39.99 e ± 2.277 | 6.36 ab ± 0.48 | 35.59 de ± 2.34 | 0.23 a ± 0.08 | 33.91 de ± 0.19 | 26.76 c ± 1.82 | 49.93 f ± 2.39 | 11.19 b ± 0.10 | 37.58 de ± 0.18 | 31.13 cd ± 2.87 |

| Sinapic acid | 20.95 b ± 0.75 | 43.73 d ± 0.44 | 13.04 a ± 1.07 | 34.91 c ± 1.15 | 22.86 b ± 2.19 | 30.37 c ± 0.99 | 24.62 b ± 1.07 | 49.75 e ± 0.11 | 34.85 c ± 0.15 | 41.44 d ± 2.14 |

| Vanillic acid | 28.75 b ± 1.65 | 81.84 g ± 0.02 | 20.90 a ± 0.11 | 63.57 ef ± 0.03 | 44.97 d ± 0.10 | 57.36 e ± 0.20 | 35.55 c ± 0.70 | 91.33 h ± 2.56 | 66.60 f ± 1.40 | 82.55 g ± 4.02 |

| Total phenolic acid | 245.71 d ± 1.02 | 272.84 e ± 4.08 | 193.09 a ± 4.16 | 210.25 b ± 1.20 | 220.72 bc ± 3.03 | 224.37 c ± 0.83 | 299.61 fg ± 1.66 | 312.90 g ± 3.19 | 297.48 f ± 7.34 | 304.76 fg ± 0.46 |

| Flavonoid | RSF (100%) | ROF (100%) | USP (100%) | UOP (100%) | SOUP (70:30) | SOUP (50:50) | FSP (100%) | FOP (100%) | SOFP (70:30) | SOFP (50:50) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Apigenin | 143.08 f ± 2.62 | 109.93 cd ± 0.51 | 116.04 d ± 5.63 | 87.65 a ± 1.40 | 100.91 bc ± 3.53 | 92.28 ab ± 0.72 | 165.42 h ± 5.02 | 129.20 e ± 0.24 | 156.78 gh ± 0.79 | 144.46 fg ± 5.23 |

| Catechin | 54.75 d ± 2.30 | nd | 10.26 b ± 0.47 | nd | 7.52 b ± 0.42 | 4.53 a ± 0.35 | 78.01 e ± 2.49 | nd | 60.43 d ± 2.49 | 46.38 c ± 2.49 |

| Daidzin | nd | 349.21 h ± 2.41 | nd | 285.47 g ± 3.39 | 95.44 e ± 0.57 | 172.76 f ± 0.82 | nd | 28.35 c ± 4.16 | 9.39 a ± 0.21 | 16.96 b ± 0.52 |

| Daidzein | nd | 92.04 d ± 2.41 | nd | 65.04 c ± 3.39 | 21.96 b ± 0.57 | 34.99 b ± 1.78 | nd | 282.95 f ± 7.79 | 102.93 d ± 2.60 | 178.24 e ± 5.20 |

| Genistin | nd | 1980.18 f ± 11.18 | nd | 1564.05 e ± 5.39 | 575.01 c ± 4.40 | 774.20 d ± 22.01 | nd | 55.62 b ± 5.51 | 15.84 a ± 0.22 | 29.69 ab ± 1.32 |

| Genistein | nd | 165.28 e ± 3.91 | nd | 109.35 c ± 7.06 | 33.54 a ± 4.98 | 58.99 b ± 8.56 | nd | 467.41 g ± 8.59 | 142.75 d ± 0.83 | 224.35 f ± 7.34 |

| Glycitin | nd | 26.07 f ± 0.76 | nd | 22.39 e ± 0.46 | 7.34 c ± 0.02 | 15.71 d ± 0.14 | nd | 1.31 b ± 0.02 | 0.31 a ± 0.02 | 0.55 a ± 0.00 |

| Glycitein | nd | 88.25 d ± 0.76 | nd | 65.91 c ± 0.46 | 22.57 a ± 1.34 | 40.31 b ± 0.88 | nd | 218.33 f ± 8.80 | 78.39 cd ± 4.40 | 143.35 e ± 8.31 |

| Kaempferol | nd | 6.24 e ± 0.25 | nd | 4.20 c ± 0.19 | 1.90 a ± 0.13 | 2.65 b ± 0.12 | nd | 10.34 f ± 0.14 | 4.00 c ± 0.07 | 5.29 d ± 0.09 |

| Luteolin | 173.73 bc ± 2.63 | nd | 231.35 d ± 5.79 | nd | 188.65 c ± 3.35 | 105.76 a ± 0.39 | 317.38 e ± 11.59 | nd | 242.28 d ± 3.21 | 157.92 b ± 5.81 |

| Naringin | 33.44 f ± 1.08 | nd | 17.32 e ± 0.11 | nd | 12.61 d ± 0.08 | 8.23 c ± 0.28 | 2.88 b ± 0.05 | nd | 1.70 ab ± 0.11 | 0.95 a ± 0.03 |

| Naringenin | 547.42 d ± 10.37 | nd | 408.22 c ± 24.92 | nd | 300.56 b ± 6.01 | 221.88 a ± 0.10 | 820.52 f ± 18.52 | nd | 582.58 d ± 16.72 | 389.38 c ± 11.64 |

| Total Flavonoids | 952.42 b ± 19.01 | 2817.19 f ± 18.14 | 783.18 a ± 24.38 | 2204.07 f ± 21.75 | 1368.02 d ± 20.39 | 1532.30 e ± 14.36 | 1384.21 d ± 27.62 | 1193.50 c ± 0.44 | 1397.39 d ± 22.82 | 1337.51 d ± 16.62 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Adeyanju, A.A.; Adebo, O.A. Effect of Okara Inclusion on Starch Digestibility and Phenolic-Related Health-Promoting Properties of Sorghum-Based Instant Porridges. Foods 2025, 14, 4149. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234149

Adeyanju AA, Adebo OA. Effect of Okara Inclusion on Starch Digestibility and Phenolic-Related Health-Promoting Properties of Sorghum-Based Instant Porridges. Foods. 2025; 14(23):4149. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234149

Chicago/Turabian StyleAdeyanju, Adeyemi Ayotunde, and Oluwafemi Ayodeji Adebo. 2025. "Effect of Okara Inclusion on Starch Digestibility and Phenolic-Related Health-Promoting Properties of Sorghum-Based Instant Porridges" Foods 14, no. 23: 4149. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234149

APA StyleAdeyanju, A. A., & Adebo, O. A. (2025). Effect of Okara Inclusion on Starch Digestibility and Phenolic-Related Health-Promoting Properties of Sorghum-Based Instant Porridges. Foods, 14(23), 4149. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234149