Specific Identification of Listeria monocytogenes in Food Using a QCM Sensor Based on Amino-Modified Mesoporous SiO2 with Enhanced Surface-Active Capabilities

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reagents and Instruments

2.2. Synthesis of NH2-MSNs via a Sol–Gel One-Pot Method

2.3. Characterization Methods and Instruments

2.4. Procedure for QCM Sensor Fabrication and Testing

2.5. Practical Sample Analysis of LM

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

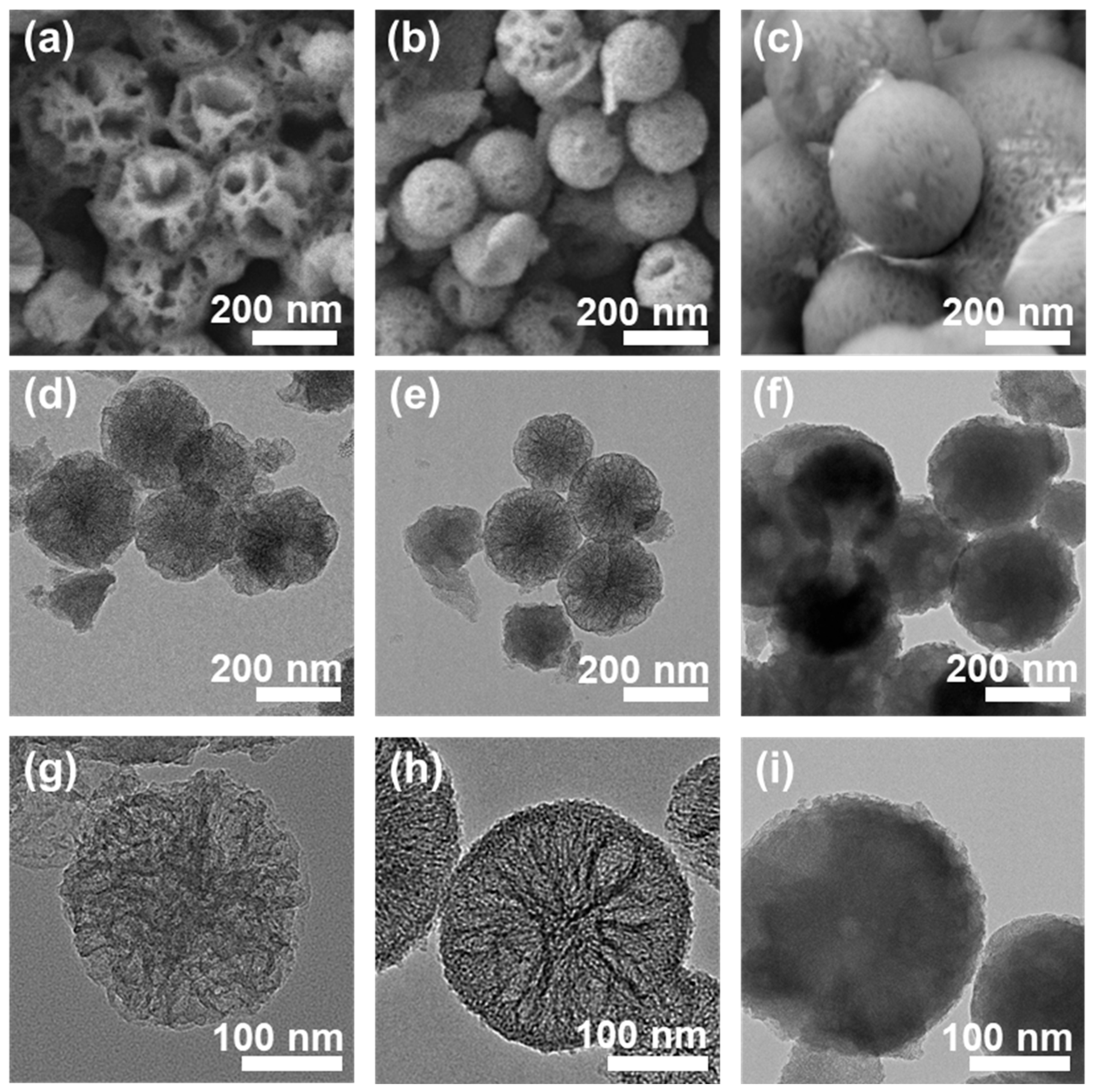

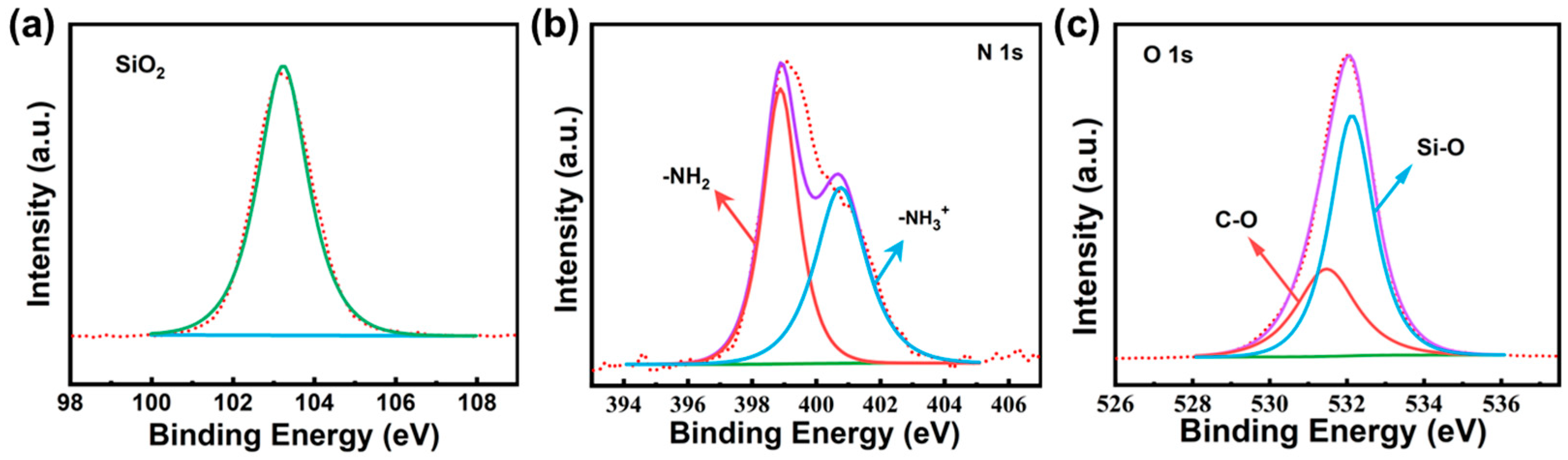

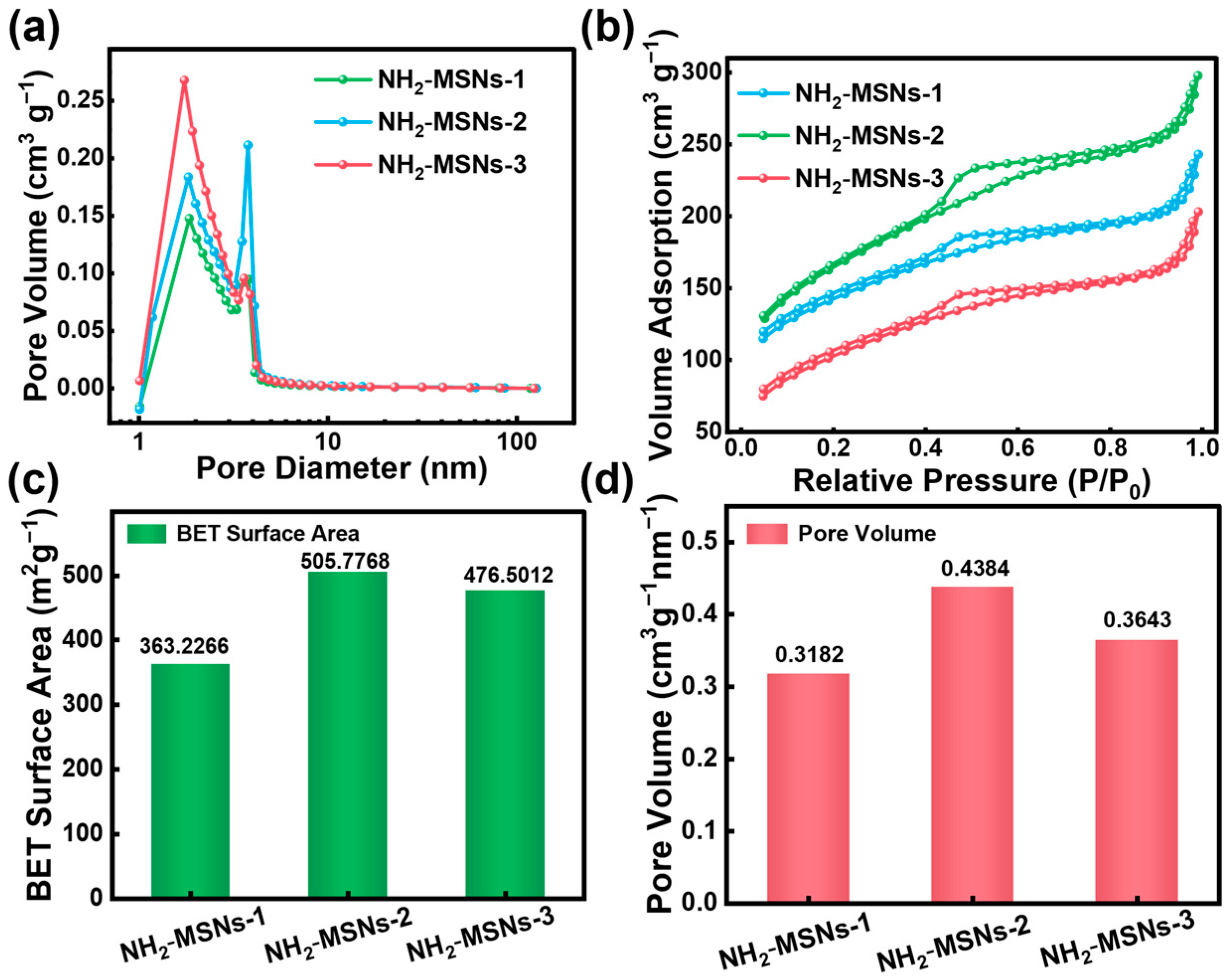

3.1. Characterizations of Materials

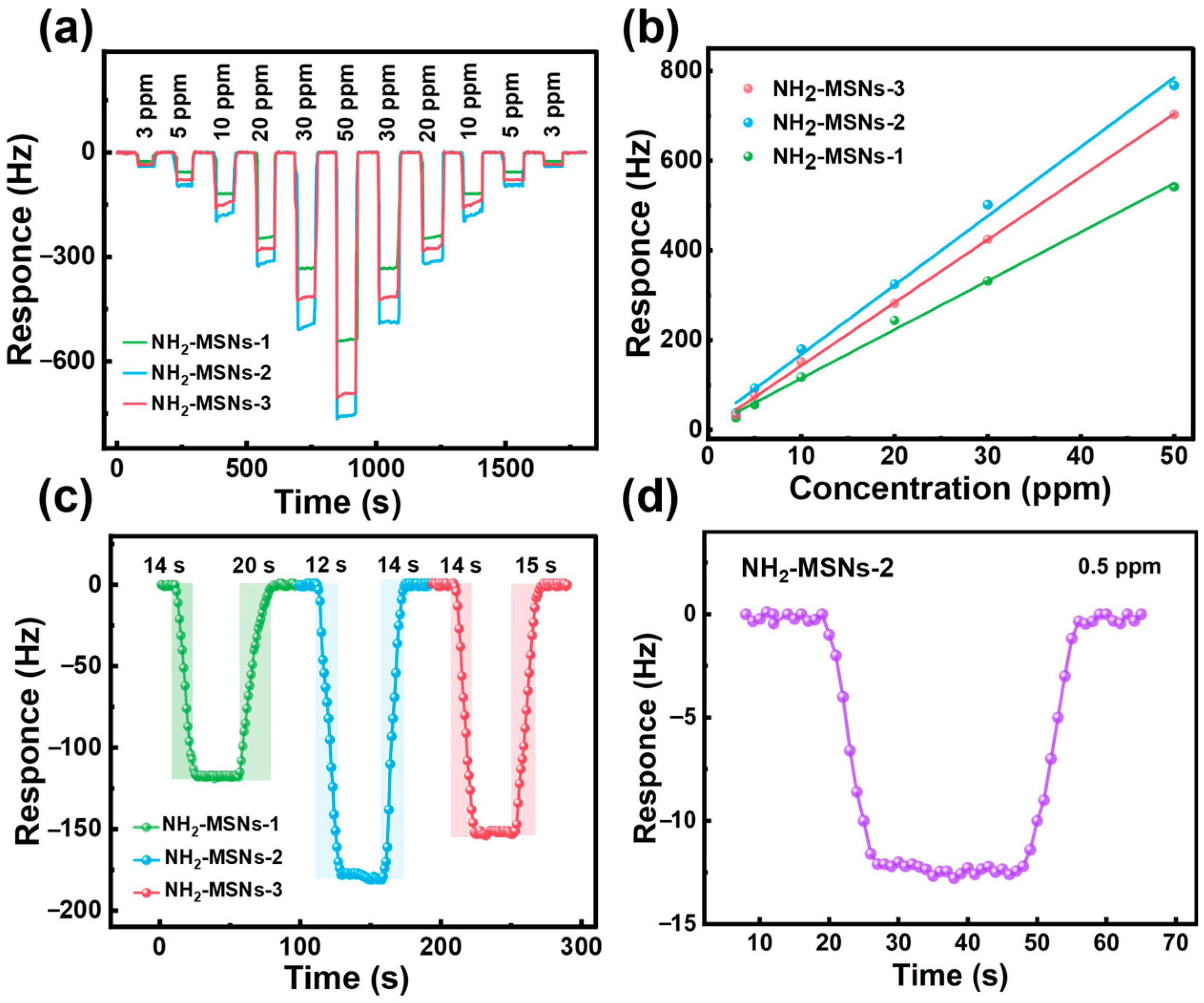

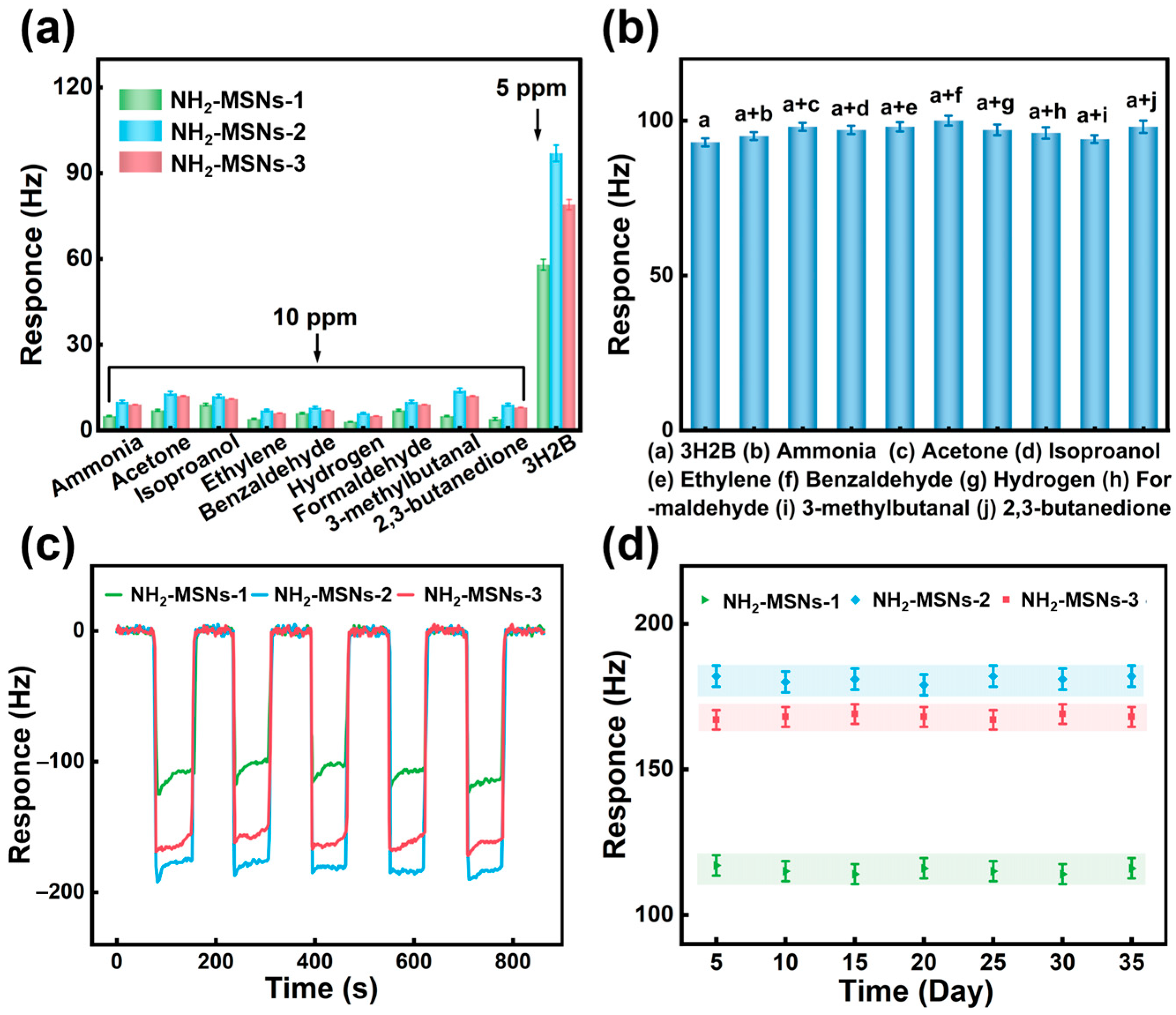

3.2. Gas Sensitivity Performance

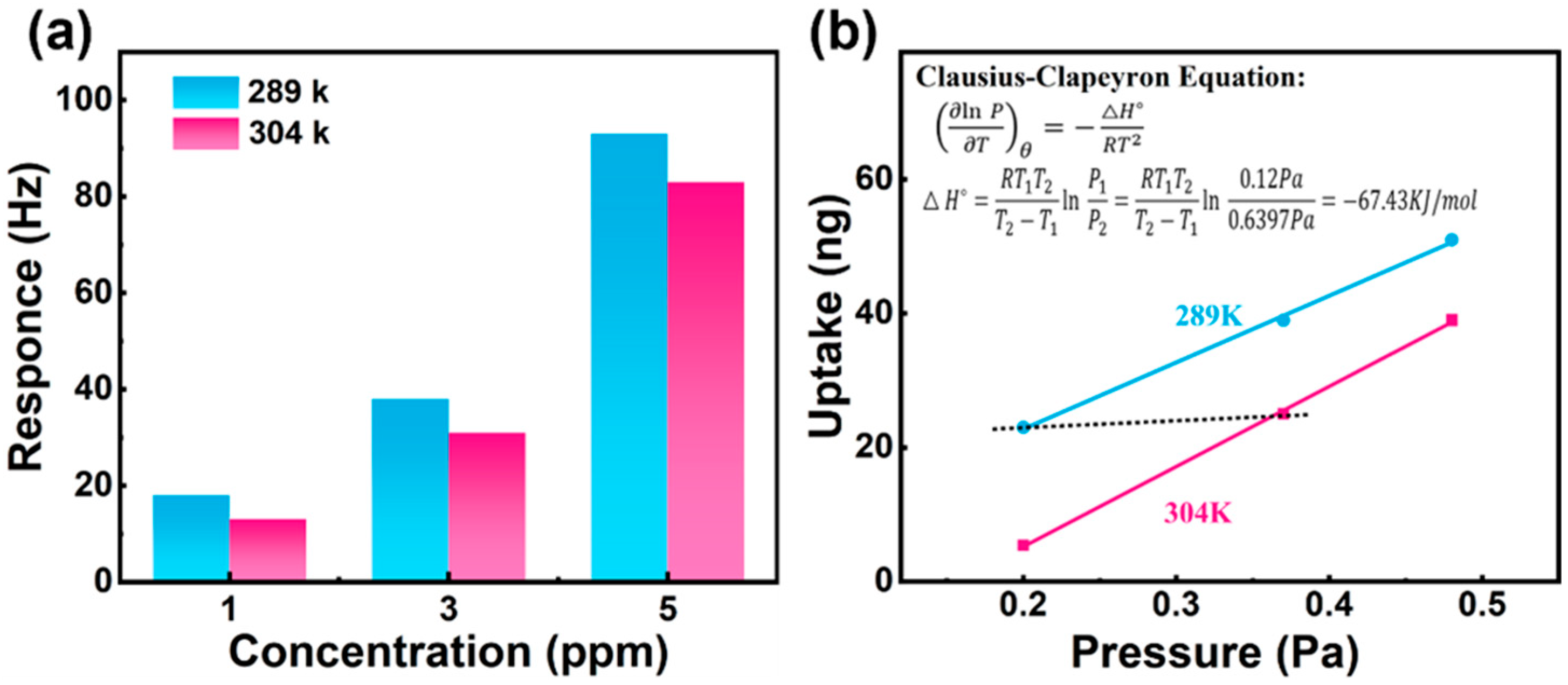

3.3. Gas-Sensing Mechanism

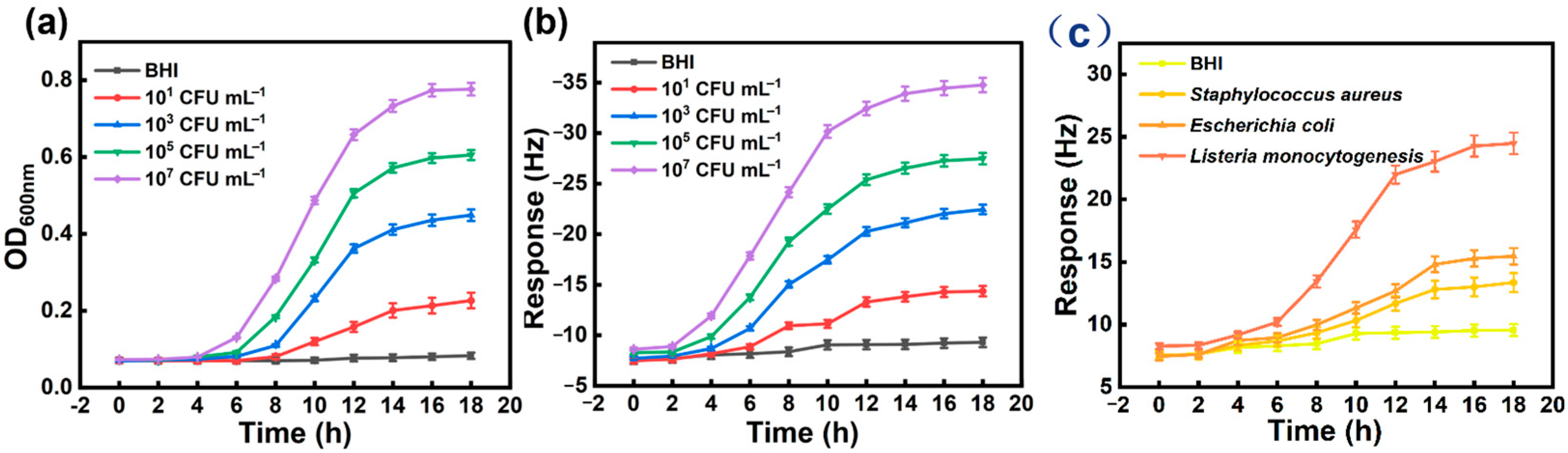

3.4. Practical Application

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| APTES | 3-Aminopropyltriethoxysilane |

| CO | Carbon monoxide |

| CTAB | Cetyltrimethylammonium bromide |

| ELISA | Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay |

| FTIR | Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy |

| LM | Listeria monocytogenes |

| MVOC | Microbial volatile organic compound |

| MSNs | Mesoporous silica nanoparticles |

| OD600 | Optical density |

| PCR | Polymerase chain reaction |

| QCM | Quartz crystal microbalance |

| SiO2 | Silicon dioxide |

| SEM | Scanning electron microscopy |

| TEM | Transmission electron microscopy |

| TEOS | Tetraethyl orthosilicate |

| XPS | X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy |

| 3H2B | 3-hydroxy-2-butanone |

| -CH2- | Alkyl chains |

| -NH2 | Amino |

| -OCH2CH3 | Ethoxy |

| ΔH | Adsorption enthalpy change |

References

- Buchanan, R.L.; Gorris, L.G.M.; Hayman, M.M.; Jackson, T.C.; Whiting, R.C. A review of Listeria monocytogenes: An update on outbreaks, virulence, dose-response, ecology, and risk assessments. Food Control 2017, 75, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zunabovic, M.; Domig, K.J.; Kneifel, W. Practical relevance of methodologies for detecting and tracing of Listeria monocytogenes in ready-to-eat foods and manufacture environments—A review. LWT—Food Sci. Technol. 2011, 44, 351–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, J.; Li, Y.; Yang, G.; Su, M.; Yang, Z. Silane-nanoSiO2 composite surface modification of steel fibres: A multiscale experimental study of fibre-UHPC interfaces. Compos. Part B Eng. 2026, 308, 112999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, M.; Rakotondrabe, T.F.; Chen, G.; Guo, M. Advances in microbial analysis: Based on volatile organic compounds of microorganisms in food. Food Chem. 2023, 418, 135950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, G.L.P.A.; Nascimento, J.S.; Margalho, L.P.; Duarte, M.C.K.H.; Esmerino, E.A.; Freitas, M.Q.; Cruz, A.G.; Sant’Ana, A.S. Quantitative microbiological risk assessment in dairy products: Concepts and applications. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 111, 610–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velusamy, V.; Arshak, K.; Korostynska, O.; Oliwa, K.; Adley, C. An overview of foodborne pathogen detection: In the perspective of biosensors. Biotechnol. Adv. 2010, 28, 232–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.-X.; Sun, X.-H.; Liu, Y.; Pan, Y.-J.; Zhao, Y. Odor Fingerprinting of Listeria monocytogenes Recognized by SPME-GC/MS and E-nose. Can. J. Microbiol. 2015, 61, 367–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zong, J.; Zhang, Y.S.; Zhu, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, W.; Zhu, Y. Rapid and highly selective detection of formaldehyde in food using quartz crystal microbalance sensors based on biomimetic poly-dopamine functionalized hollow mesoporous silica spheres. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2018, 271, 311–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broten, C.; Wydallis, J.; Reilly, T.; Bisha, B. Development and evaluation of a paper-based microfluidic device for detection of Listeria monocytogenes on food contact and non-food contact surfaces. Foods 2022, 11, 947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golshadi, Z.; Dinari, M.; Knebel, A.; Lützenkirchen, J.; Monjezi, B.H. Metal organic and covalent organic framework-based QCM sensors for environmental pollutant detection and beyond. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2024, 521, 216163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, J.R.; Baumann, A.E.; Stafford, C.M. The role of humidity in enhancing CO2 capture efficiency in poly(ethyleneimine) thin films. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 507, 160347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.H.; Moon, Y.K.; Lee, J.-H.; Chan Kang, Y.; Jeong, S.-Y. Hierarchically porous PdO-functionalized SnO2 nano-architectures for exclusively selective, sensitive, and fast detection of exhaled hydrogen. J. Mater. Chem. A 2023, 11, 1159–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.H.; Song, S.G.; Shin, M.H.; Song, C.; Bae, H.Y. N-triflyl phosphoric triamide: A high-performance purely organic trifurcate quartz crystal microbalance sensor for chemical warfare agent. ACS Sens. 2022, 7, 423–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, N.; Zhang, J.B.; Wöll, C.; Gu, Z.G.; Zhang, J. Breathable biomimetic chiral porous MOF thin films for multiple enantiomers sensing. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, 35, 2422860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Hu, H.; Tong, Z.; Lin, H.; Chu, Z.; Hu, Y.; Yang, Z. Double-layer structure superhydrophobic coatings based on silica-modified graphene oxide: Robust stability, weather resistance, and anti-corrosion. Prog. Org. Coat. 2026, 210, 109668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidina Ousseini, O.; Peng, B.; Miao, Z.; Cheng, K.; Li, J.; Altaf, M.F.; Ramatou, I.I.; Salim, M.Z.; Yang, X.; Zhang, H.; et al. Rheological and displacement performance of modified nano-SiO2 grafted polymeric system for enhanced oil recovery. Geoenergy Sci. Eng. 2026, 257, 214213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rokicka-Konieczna, P.; Wanag, A.; Sienkiewicz, A.; Izuma, D.S.; Ekiert, E.; Kusiak-Nejman, E.; Terashima, C.; Yasumori, A.; Fujishima, A.; Morawski, A.W. Photocatalytic inactivation of co-culture of E. coli and S. epidermidis using APTES-modified TiO2. Molecules 2023, 28, 1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proença, M.; Rodrigues, M.S.; Moura, C.; Machado, A.V.; Borges, J.; Vaz, F. Nanoplasmonic Au:CuO thin films functionalized with APTES to enhance the sensitivity of gas sensors. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2024, 401, 134959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Divyamani, M.P.; Hegde, S.N.; Naveen Kumar, S.K.; Dharma Guru Prasad, M.P. ZnO nanoparticle-based electrochemical immunosensor for one-step quantification of cortisol in saliva. ACS Omega 2025, 10, 38303–38310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Wei, S.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, K.; Ye, G.; Yang, H.; Kwan, T.H. Hydrophilic SiO2 nanoparticle deposition on boiling surface: Molecular dynamics insights into deposition behavior and heat transfer performance. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2026, 255, 127872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeamjumnunja, K.; Cheycharoen, O.; Phongzitthiganna, N.; Hannongbua, S.; Prasittichai, C. Surface-modified halloysite nanotubes as electrochemical CO2 sensors. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2021, 4, 3686–3695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaggiotti, S.; Scroccarello, A.; Della Pelle, F.; Ferraro, G.; Del Carlo, M.; Mascini, M.; Cichelli, A.; Compagnone, D. An electronic nose based on 2D group VI transition metal dichalcogenides/organic compounds sensor array. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2022, 218, 114749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khandaker, M.U.; Itas, Y.S.; El-Rayyes, A.; Benabdallah, F. DFT study on radon adsorption by graphene oxide quantum dots from optically radioactive environment, using three organic functional groups: A new approach to wastewater treatment. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 2026, 239, 113259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, J.; Liu, L.; Yu, Z.; Wu, Q.; Zhang, L. Silane coupling agent 3-aminopropyltriethoxysilane modified silica/epoxidized solution-polymerized styrene butadiene rubber nanocomposites. Polym. Compos. 2023, 44, 6957–6968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torad, N.L.; Kim, J.; Kim, M.; Lim, H.; Na, J.; Alshehri, S.M.; Ahamad, T.; Yamauchi, Y.; Eguchi, M.; Ding, B.; et al. Nanoarchitectured porous carbons derived from ZIFs toward highly sensitive and selective QCM sensor for hazardous aromatic vapors. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 405, 124248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montejo-Mesa, L.A.; Díaz-García, A.M.; Cavalcante, C.L.; Vilarrasa-García, E.; Rodríguez-Castellón, E.; Ballesteros-Plata, D.; Autié-Castro, G.I. Evaluation of APTES-functionalized zinc oxide nanoparticles for adsorption of CH4 and CO2. Molecules 2024, 29, 5219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabdin, S.; Azraie Mohd Azmi, M.; Azurin Badruzaman, N.; Zuriati Makmon, F.; Abd Aziz, A.; Azura Mohd Said, N. Effect of APTES percentage towards reduced graphene oxide screen printed electrode surface for biosensor application. Mater. Today Proc. 2019, 19, 1183–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Duan, X.; Liu, C.; Liu, S.; Li, P.; Su, D.; Sun, X.; Guo, Y.; Chen, W.; Wang, Z. La-Ce-MOF nanocomposite coated quartz crystal microbalance gas sensor for the detection of amine gases and formaldehyde. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 467, 133672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okur, S.; Hashem, T.; Bogdanova, E.; Hodapp, P.; Heinke, L.; Bräse, S.; Wöll, C. Optimized detection of volatile organic compounds utilizing durable and selective arrays of tailored UiO-66-X SURMOF sensors. ACS Sens. 2024, 9, 622–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Ye, W.; Ruan, J.; Ren, Q.; Dong, S.; Chen, D.; Li, N.; Xu, Q.; Li, H.; Lu, J. Lead-free halide double perovskite Cs2AgBiCl6 for H2S trace detection at room temperature. ACS Sens. 2025, 10, 2224–2233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Deng, F.; Xu, M.; Wang, J.; Wei, Z.; Wang, Y. GO/Cu2O nanocomposite based QCM gas sensor for trimethylamine detection under low concentrations. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2018, 273, 498–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Fei, T.; Guan, X.; Zhao, H.; Zhang, T. Highly sensitive and chemically stable NH3 sensors based on an organic acid-sensitized cross-linked hydrogel for exhaled breath analysis. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2021, 191, 113459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, X.; Chen, C.; Zhang, Y.; Kong, H.; An, R.; Li, S.; Liu, W.; Ji, Q. Chiral recognition on bare gold surfaces by quartz crystal microbalance. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 25028–25033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, I.R.; Jung, S.I.; Lee, G.; Park, I.; Kim, S.B.; Kim, H.J. Quartz crystal microbalance with thermally-controlled surface adhesion for an efficient fine dust collection and sensing. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 424, 127560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lan, T.; Dong, Y.; Xu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Jiang, L.; Zhou, W.; Sui, X. Quercetin directed transformation of calcium carbonate into porous calcite and their application as delivery system for future foods. Biomaterials 2023, 301, 122216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, J.S.; Kubus, M.; Pedersen, K.S.; Andersen, S.I.; Sundberg, J. Room-temperature monitoring of CH4 and CO2 using a metal-organic framework-based QCM sensor showing inherent analyte discrimination. ACS Sens. 2023, 8, 3478–3486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Zhou, X.; Shan, Y.; Yue, H.; Huang, R.; Hu, J.; Xing, D. Sensitive detection of a bacterial pathogen using allosteric probe-initiated catalysis and CRISPR-Cas13a amplification reaction. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flickinger, J.C.; Rodeck, U.; Snook, A.E. Listeria monocytogenes as a vector for Cancer immunotherapy: Current understanding and progress. Vaccines 2018, 6, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrucci, S.; Costa, C.; Broyles, D.; Dikici, E.; Daunert, S.; Deo, S. On-site detection of food and waterborne bacteria-Current technologies, challenges, and future directions. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 115, 409–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Zhao, C.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, D.; Yin, X.; Han, J.; Wei, J.; Zhao, Y.; Zhu, Y. Highly selective QCM sensor based on functionalized hierarchical hollow TiO2 nanospheres for detecting ppb-level 3-hydroxy-2-butanone biomarker at room temperature. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2025, 36, 109939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, S.; Zhao, C.; Shen, J.; Wei, J.; Liu, H.; Pan, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Zhu, Y. Hierarchical flower-like WO3 nanospheres decorated with bimetallic Au and Pd for highly sensitive and selective detection of 3-Hydroxy-2-butanone biomarker. ACS Sens. 2023, 8, 728–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.-Y.; Liu, P.-P.; Cai, H.-J.; Li, M.-M.; Deng, C.-H.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, Z.-H.; Zhu, Y.-H. PdRh bimetallic-loaded α-Fe2O3 nanospindles with ppb-limit of 3-hydroxy-2-butanone biomarker detection: Particle dimension regulation and oxygen spillover effect. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 512, 162686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fan, Z.; Li, M.; Wang, X.; Zhou, H.; Ahmed, F.; Zhu, Y. Specific Identification of Listeria monocytogenes in Food Using a QCM Sensor Based on Amino-Modified Mesoporous SiO2 with Enhanced Surface-Active Capabilities. Foods 2025, 14, 4151. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234151

Fan Z, Li M, Wang X, Zhou H, Ahmed F, Zhu Y. Specific Identification of Listeria monocytogenes in Food Using a QCM Sensor Based on Amino-Modified Mesoporous SiO2 with Enhanced Surface-Active Capabilities. Foods. 2025; 14(23):4151. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234151

Chicago/Turabian StyleFan, Ziliang, Miaomiao Li, Xingyu Wang, Haixia Zhou, Faraz Ahmed, and Yongheng Zhu. 2025. "Specific Identification of Listeria monocytogenes in Food Using a QCM Sensor Based on Amino-Modified Mesoporous SiO2 with Enhanced Surface-Active Capabilities" Foods 14, no. 23: 4151. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234151

APA StyleFan, Z., Li, M., Wang, X., Zhou, H., Ahmed, F., & Zhu, Y. (2025). Specific Identification of Listeria monocytogenes in Food Using a QCM Sensor Based on Amino-Modified Mesoporous SiO2 with Enhanced Surface-Active Capabilities. Foods, 14(23), 4151. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234151