Current Status and Future Perspectives of Betaine and Betaine-Based Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents: A Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Physicochemical Properties of BET

3. Healthy and Functional Properties of BET

4. BET Production/Extraction

4.1. Reactive Extraction Using Dinonylnaphthalene Disulfonic Acid (DNNDSA)

4.2. Alcohol Extraction

4.3. Chromatographic Separation and Crystallization

4.4. Membrane Technology

5. Fundamentals of BET-Based Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents

5.1. BET-Based DESs

5.2. Characterization Techniques for BET-Based DES

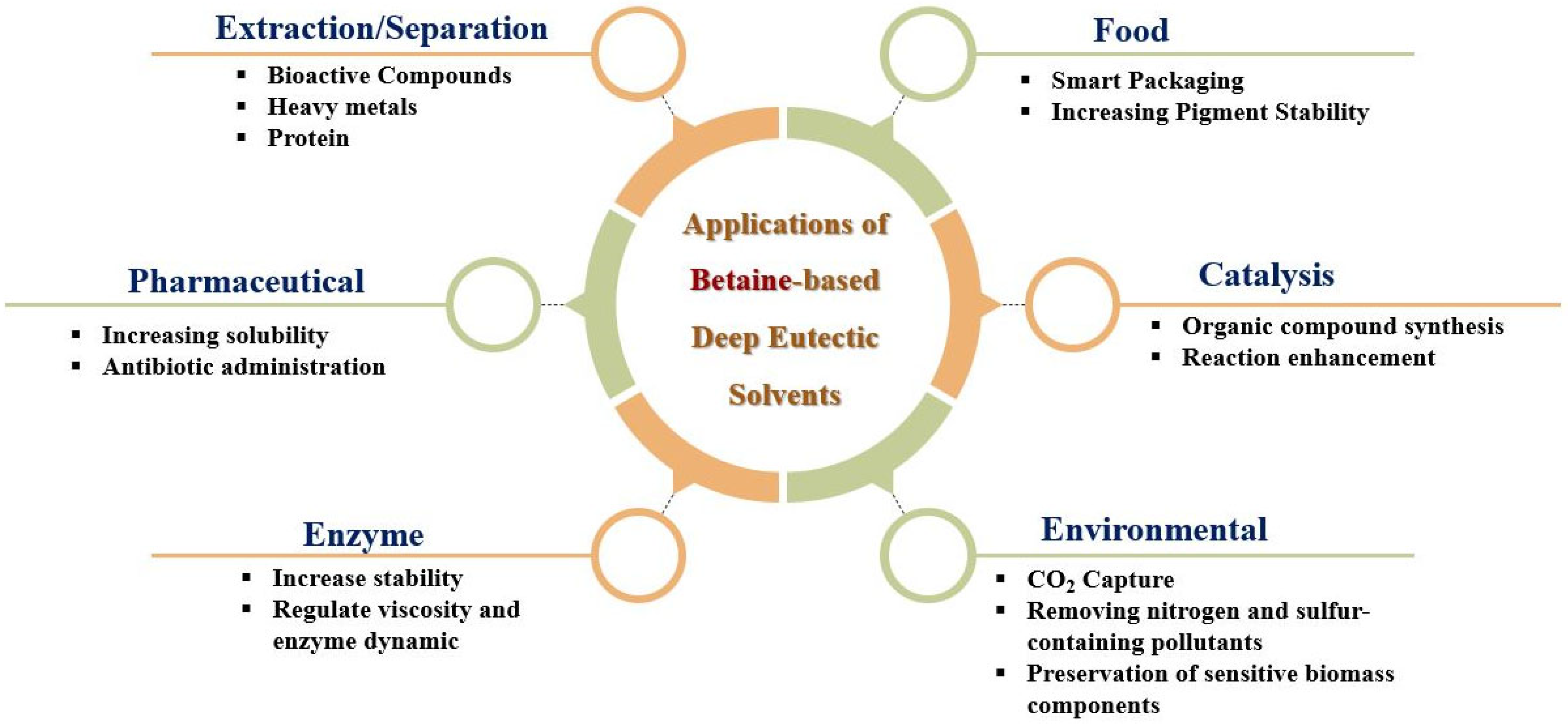

6. Current Applications of BET-Based DES

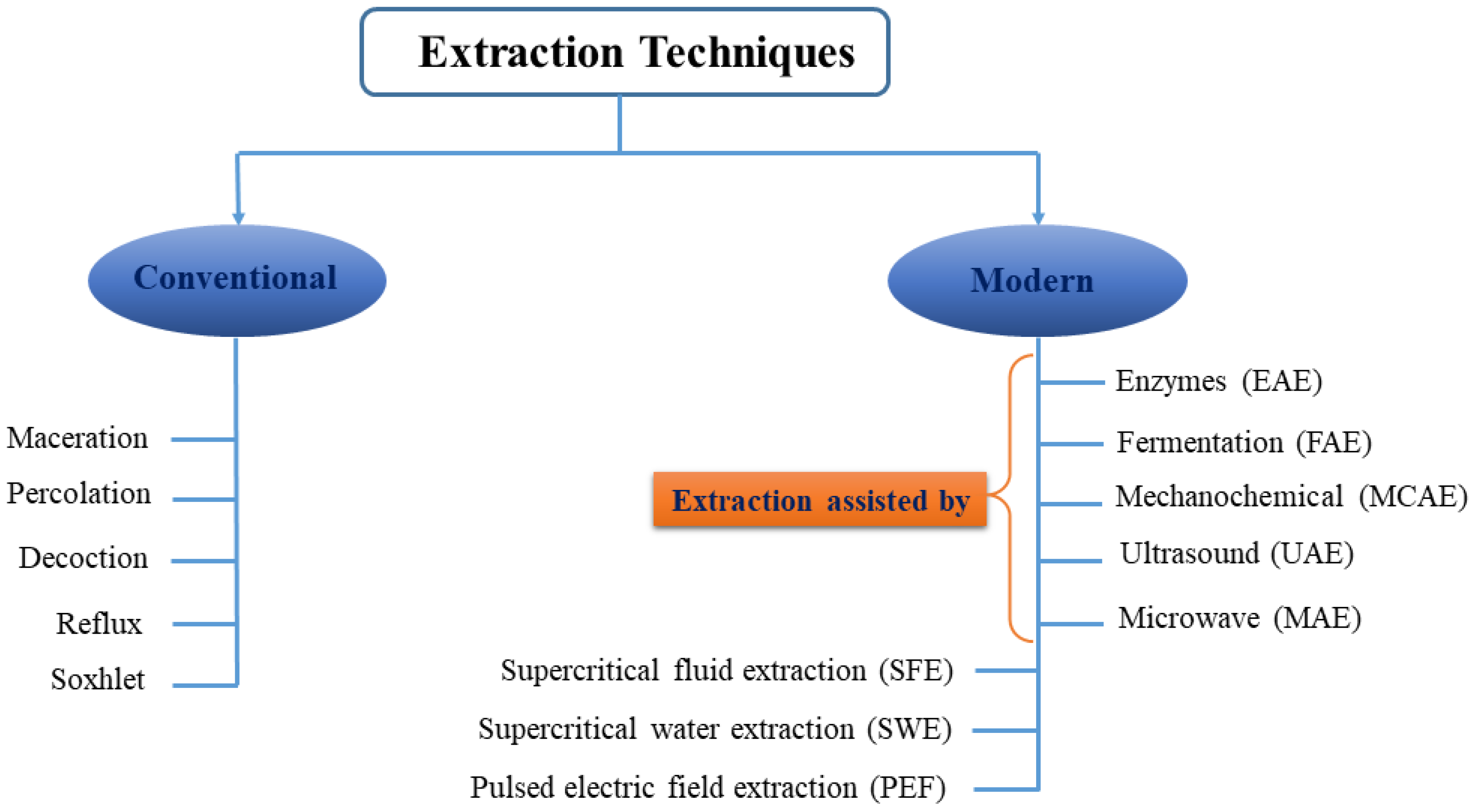

6.1. Extraction/Separation of Compounds

6.2. Catalysis and Chemical Synthesis (e.g., Organic Reactions, Enzymatic Processes)

6.3. Specific Applications in Pharmaceutical Sciences

6.4. Specific Applications in Food Science and Preservation

6.5. Specific Applications in Electrochemical Energy Storage

6.6. Specific Application in the Environment

7. Regulatory and Safety Considerations

8. Future Perspectives

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rodrigues, L.A.; Cardeira, M.; Leonardo, I.C.; Gaspar, F.B.; Redovniković, I.R.; Duarte, A.R.C.; Paiva, A.; Matias, A.A. Deep eutectic systems from betaine and polyols–Physicochemical and toxicological properties. J. Mol. Liq. 2021, 335, 116201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, A.P.; Capper, G.; Davies, D.L.; Rasheed, R.K.; Tambyrajah, V. Novel solvent properties of choline chloride/urea mixtures. Chem. Commun. 2003, 39, 70–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, M.Q.; Abbasi, N.M.; Anderson, J.L. Deep eutectic solvents in separations: Methods of preparation, polarity, and applications in extractions and capillary electrochromatography. J. Chromatogr. A 2020, 1633, 461613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paiva, A.; Craveiro, R.; Aroso, I.; Martins, M.; Reis, R.L.; Duarte, A.R.C. Natural deep eutectic solvents–solvents for the 21st century. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2014, 2, 1063–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, C.; Tu, W.; Levers, O.; Brohl, A. Hallett Green and Sustainable Solvents in Chemical Processes. Chem. Rev. 2018, 118, 747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowen, H.; Durrani, R.; Delavault, A.; Durand, E.; Chenyu, J.; Yiyang, L.; Lili, S.; Jian, S.; Weiwei, H.; Fei, G. Application of deep eutectic solvents in protein extraction and purification. Front. Chem. 2022, 10, 912411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuad, F.M.; Nadzir, M.M. The formulation and physicochemical properties of betaine-based natural deep eutectic solvent. J. Mol. Liq. 2022, 360, 119392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, C.R.; Kempson, S.A. Betaine chemistry, roles, and potential use in liver disease. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA) Gen. Subj. 2016, 1860, 1098–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arumugam, M.K.; Paal, M.C.; Donohue, T.M.; Ganesan, M.; Osna, N.A.; Kharbanda, K.K. Beneficial effects of betaine: A comprehensive review. Biology 2021, 10, 456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krisanti, E.A.; Saputra, K.; Arif, M.M.; Mulia, K. Formulation and characterization of betaine-based deep eutectic solvent for extraction phenolic compound from spent coffee grounds. In Proceedings of the 5th International Symposium on Applied Chemistry, Tangerang, Indonesia, 23–24 October 2019; AIP Publishing LLC: Melville, NY, USA, 2019; p. 020040. [Google Scholar]

- Cannavacciuolo, C.; Pagliari, S.; Frigerio, J.; Giustra, C.M.; Labra, M.; Campone, L. Natural deep eutectic solvents (NADESs) combined with sustainable extraction techniques: A review of the green chemistry approach in food analysis. Foods 2022, 12, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hikmawanti, N.P.E.; Ramadon, D.; Jantan, I.; Mun’im, A. Natural deep eutectic solvents (NADES): Phytochemical extraction performance enhancer for pharmaceutical and nutraceutical product development. Plants 2021, 10, 2091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z. Natural deep eutectic solvents and their applications in biotechnology. In Application of Ionic Liquids in Biotechnology; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 31–59. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, I.J.; Paiva, A.; Diniz, M.; Duarte, A.R. Uncovering biodegradability and biocompatibility of betaine-based deep eutectic systems. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 40218–40229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varriale, S.; Delorme, A.E.; Andanson, J.-M.; Devemy, J.; Malfreyt, P.; Verney, V.; Pezzella, C. Enhancing the thermostability of engineered laccases in aqueous betaine-based natural deep eutectic solvents. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2021, 10, 572–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richter, J.; Pietsch, T.; Elsner, N.; Ruck, M. Critical Investigation of Betaine Hydrochloride-Based Deep Eutectic Solvent for Ionometallurgical Metal Production. Chem. 2023, 12, e202300114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, J.K.U.; Hadinoto, K. Deep eutectic solvent as green solvent in extraction of biological macromolecules: A review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 3381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahar, Y.; Thickett, S.C. Greener, faster, stronger: The benefits of deep eutectic solvents in polymer and materials science. Polymers 2021, 13, 447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, X.-L.; Yao, Y.-H.; Zhen, J.-F.; Cao, Y.; Gao, W.; Lu, T.-B.; Chen, J.-M. An Efficient and Organic Solvent-Free Slurry Method for Cocrystal Synthesis: Using Betaine Deep Eutectic Solvents as Dual-Functional Solvents and Reactants. Cryst. Growth Des. 2024, 24, 7686–7694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yancey, P.H.; Clark, M.E.; Hand, S.C.; Bowlus, R.D.; Somero, G.N. Living with water stress: Evolution of osmolyte systems. Science 1982, 217, 1214–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobrijević, D.; Pastor, K.; Nastić, N.; Özogul, F.; Krulj, J.; Kokić, B.; Bartkiene, E.; Rocha, J.M.; Kojić, J. Betaine as a functional ingredient: Metabolism, health-promoting attributes, food sources, applications and analysis methods. Molecules 2023, 28, 4824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Qin, L.; Zhou, Z.; Wang, J. Solubility and solution thermodynamics of betaine in different pure solvents and binary mixtures. J. Chem. Eng. Data 2012, 57, 2128–2135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadaei, Z.; Rad-Moghadam, K. Deep eutectic melt of betaine and trichloroacetic acid; its anomalous thermal behavior and green promotion effect in selective synthesis of benzimidazoles. J. Mol. Liq. 2024, 399, 124401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolte, K.D.; Hanson, A.D.; Gage, D.A. Proline accumulation and methylation to proline betaine in citrus: Implications for genetic engineering of stress resistance. J. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 1997, 122, 8–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzafera, P.; Crozier, A.; Magalhães, A.C. Caffeine metabolism in Coffea arabica and other species of coffee. Phytochemistry 1991, 30, 3913–3916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajasekaran, L.R.; Aspinall, D.; Jones, G.; Paleg, L. Stress metabolism. IX. Effect of salt stress on trigonelline accumulation in tomato. Can. J. Plant Sci. 2001, 81, 487–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tramontano, W.A.; Jouve, D. Trigonelline accumulation in salt-stressed legumes and the role of other osmoregulators as cell cycle control agents. Phytochemistry 1997, 44, 1037–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blunden, G.; Gordon, S.M. Betaines and their sulphonio analogues in marine algae. Prog. Phycol. Res. 1986, 4, 39–80. [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida, K.; Kuroda, K.; Inoue, Y.; Chen, H.; Wanibuchi, H.; Fukushima, S.; Endo, G. Metabolites of arsenobetaine in rats: Does decomposition of arsenobetaine occur in mammals? Appl. Organomet. Chem. 2001, 15, 271–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flowers, T.; Troke, P.; Yeo, A. The mechanism of salt tolerance in halophytes. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. 1977, 28, 89–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sizeland, P.C.; Chambers, S.T.; Lever, M.; Bason, L.M.; Robson, R.A. Organic osmolytes in human and other mammalian kidneys. Kidney Int. 1993, 43, 448–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lever, M.; Sizeland, P.; Bason, L.; Hayman, C.; Chambers, S. Glycine betaine and proline betaine in human blood and urine. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Gen. Subj. 1994, 1200, 259–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, S.A. Betaine in human nutrition. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2004, 80, 539–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hruby, M.; Ombabi, A.; Schlagheck, A. Natural betaine maintains layer performance in methionine/choline chloride reduced diets. In Proceedings of the 15th European Symposium on Poultry Nutrition, Balatonfüred, Hungary, 25–29 September 2005; World’s Poultry Science Association (WPSA): Beekbergen, The Netherlands, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Zeisel, S.H.; Mar, M.-H.; Howe, J.C.; Holden, J.M. Concentrations of choline-containing compounds and betaine in common foods. J. Nutr. 2003, 133, 1302–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willingham, B.D.; Ragland, T.J.; Ormsbee, M.J. Betaine supplementation may improve heat tolerance: Potential mechanisms in humans. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perumal, S.K.; Arumugam, M.K.; Osna, N.A.; Rasineni, K.; Kharbanda, K.K. Betaine regulates the gut-liver axis: A therapeutic approach for chronic liver diseases. Front. Nutr. 2025, 12, 1478542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, C.; Kaplowitz, N. Betaine decreases hyperhomocysteinemia, endoplasmic reticulum stress, and liver injury in alcohol-fed mice. Gastroenterology 2003, 124, 1488–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McRae, M.P. Betaine supplementation decreases plasma homocysteine in healthy adult participants: A meta-analysis. J. Chiropr. Med. 2013, 12, 20–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, J.; Shen, L.; Tan, Z.; Zhang, P.; Zhao, X.; Xu, Y.; Gan, M.; Yang, Q.; Ma, J.; Jiang, A. Betaine supplementation enhances lipid metabolism and improves insulin resistance in mice fed a high-fat diet. Nutrients 2018, 10, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Zhang, H.; Guo, X.-f.; Li, K.; Li, S.; Li, D. Effect of betaine on reducing body fat—A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashtary-Larky, D.; Bagheri, R.; Tinsley, G.M.; Asbaghi, O.; Salehpour, S.; Kashkooli, S.; Kooti, W.; Wong, A. Betaine supplementation fails to improve body composition: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. J. Nutr. 2022, 128, 975–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Zhang, H.; Li, H.; Lai, F.; Li, X.; Tang, Y.; Min, T.; Wu, H. Antioxidant mechanism of betaine without free radical scavenging ability. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2016, 64, 7921–7930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malik, M.I.; Bilal, M.; Anwar, M.; Hassan, T.; Rashid, M.A.; Tarla, D.; Dunshea, F.R.; Cheng, L. Effects of betaine supplementation on dry matter intake, milk characteristics, plasma non-esterified fatty acids, and β-hydroxybutyric acid in dairy cattle: A meta-analysis. J. Anim. Sci. 2024, 102, skae241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekdash, R.A. Methyl donors, epigenetic alterations, and brain health: Understanding the connection. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 2346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olthof, M.R.; Verhoef, P. Effects of betaine intake on plasma homocysteine concentrations and consequences for health. Curr. Drug Metab. 2005, 6, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habibi, F.; Valero, D.; Serrano, M.; Guillén, F. Exogenous application of glycine betaine maintains bioactive compounds, antioxidant activity, and physicochemical attributes of blood orange fruit during prolonged cold storage. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 873915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bahmani, R.; Razavi, F.; Mortazavi, S.N.; Gohari, G.; Juárez-Maldonado, A. Enhancing postharvest quality and shelf life of strawberries through advanced coating technologies: A comprehensive investigation of chitosan and glycine betaine nanoparticle treatments. Plants 2024, 13, 1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, C.; Chen, C.; Zhang, S.; Zhao, X.; Wu, C.; Kou, X.; Xue, Z. Glycine betaine inhibits postharvest softening and quality decline of winter jujube fruit by regulating energy and antioxidant metabolism. Food Chem. 2023, 410, 135445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dikilitas, M.; Simsek, E.; Roychoudhury, A. Role of proline and glycine betaine in overcoming abiotic stresses. In Protective Chemical Agents in the Amelioration of Plant Abiotic Stress: Biochemical and Molecular Perspectives; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Alirezaei, M.; Gheisari, H.R.; Ranjbar, V.R.; Hajibemani, A. Betaine: A promising antioxidant agent for enhancement of broiler meat quality. Br. Poult. Sci. 2012, 53, 699–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, M.; Rehman, H.M.; Ahmed, N.; Nawaz, S.; Saleem, F.; Ahmad, S.; Uzair, M.; Rana, I.A.; Atif, R.M.; Zaman, Q.U. Using exogenous melatonin, glutathione, proline, and glycine betaine treatments to combat abiotic stresses in crops. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 12913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malekzadeh, P.; Kamrani, A.; Abbasi, Z.; Sadeghi, M. Glycine betaine treatment extends the shelf life and retards cap browning of button mushrooms. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 20796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Cao, F.; Richmond, M.E.A.; Qiu, C.; Wu, F. Foliar application of betaine improves water-deficit stress tolerance in barley (Hordeum vulgare L.). Plant Growth Regul. 2019, 89, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basit, F.; Alyafei, M.; Hayat, F.; Al-Zayadneh, W.; El-Keblawy, A.; Sulieman, S.; Sheteiwy, M.S. Deciphering the role of glycine betaine in enhancing plant performance and defense mechanisms against environmental stresses. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1582332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shemi, R.; Wang, R.; Gheith, E.-S.M.; Hussain, H.A.; Cholidah, L.; Zhang, K.; Zhang, S.; Wang, L. Role of exogenous-applied salicylic acid, zinc and glycine betaine to improve drought-tolerance in wheat during reproductive growth stages. BMC Plant Biol. 2021, 21, 574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, X.; Qian, J.; Liu, P.; Zeng, H.; Chen, G.; Wang, Y. Exogenous betaine enhances the protrusion vigor of rice seeds under heat stress by regulating plant hormone signal transduction and its interaction network. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.; Abbas, Z.; Seleiman, M.F.; Rizwan, M.; YavaŞ, İ.; Alhammad, B.A.; Shami, A.; Hasanuzzaman, M.; Kalderis, D. Glycine betaine accumulation, significance and interests for heavy metal tolerance in plants. Plants 2020, 9, 896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kempson, S.A.; Vovor-Dassu, K.; Day, C. Betaine transport in kidney and liver: Use of betaine in liver injury. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2013, 32, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCue, K.F.; Hanson, A.D. Drought and salt tolerance: Towards understanding and application. Trends Biotechnol. 1990, 8, 358–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkataramani, D.; Tsulaia, A.; Amin, S. Fundamentals and applications of particle stabilized emulsions in cosmetic formulations. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2020, 283, 102234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelleppan, V.T.; King, J.P.; Butler, C.S.; Williams, A.P.; Tuck, K.L.; Tabor, R.F. Heads or tails? The synthesis, self-assembly, properties and uses of betaine and betaine-like surfactants. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2021, 297, 102528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Zwart, F.; Slow, S.; Payne, R.; Lever, M.; George, P.; Gerrard, J.; Chambers, S. Glycine betaine and glycine betaine analogues in common foods. Food Chem. 2003, 83, 197–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cholewa, J.M.; Guimaraes-Ferreira, L.; Zanchi, N.E. Effects of betaine on performance and body composition: A review of recent findings and potential mechanisms. Amino Acids 2014, 46, 1785–1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahlström, B.; Thompson, R.; Edebo, L. Loss of bactericidal capacity of long-chain quaternary ammonium compounds with protein at lowered temperature. APMIS 1999, 107, 606–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurko, L. Synthesis of Betaine, Choline and Carnitine Containing Polymers for Dermal Wound Healing. Doctoral Dissertation, University of Maribor, Maribor, Slovenia, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Y.; Wang, D.; Ma, L.Z. Effect of polyhexamethylene biguanide in combination with undecylenamidopropyl betaine or PslG on biofilm clearance. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindstedt, M.; Allenmark, S.; Thompson, R.; Edebo, L. Antimicrobial activity of betaine esters, quaternary ammonium amphiphiles which spontaneously hydrolyze into nontoxic components. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1990, 34, 1949–1954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, D.; Wang, X.; Cao, S.; Ba, L.; Chen, J. Recent Advances in Betaine: Extraction, Identification, and Bioactive Functions in Human Health. Food Sci. Nutr. 2025, 13, e70173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Wu, X.; Lai, F.; Zhang, X.; Wu, H.; Min, T. Betaine inhibits hepatitis B virus with an advantage of decreasing resistance to lamivudine and interferon α. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2016, 64, 4068–4077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajmirza, A.; Emadali, A.; Gauthier, A.; Casasnovas, O.; Gressin, R.; Callanan, M.B. BET family protein BRD4: An emerging actor in NFκB signaling in inflammation and cancer. Biomedicines 2018, 6, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belkina, A.C.; Nikolajczyk, B.S.; Denis, G.V. BET protein function is required for inflammation: Brd2 genetic disruption and BET inhibitor JQ1 impair mouse macrophage inflammatory responses. J. Immunol. 2013, 190, 3670–3678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blinov, A.V.; Nagdalian, A.A.; Siddiqui, S.A.; Maglakelidze, D.G.; Gvozdenko, A.A.; Blinova, A.A.; Yasnaya, M.A.; Golik, A.B.; Rebezov, M.B.; Jafari, S.M. Synthesis and characterization of selenium nanoparticles stabilized with cocamidopropyl betaine. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 21975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Kou, H. The effect of NaCl on the solution properties of a betaine-type amphiphilic polymer and its performance enhancement mechanism. Colloid Polym. Sci. 2022, 300, 69–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petronini, P.G.; De Angelis, E.; Borghetti, P.; Borghetti, A.; Wheeler, K.P. Modulation by betaine of cellular responses to osmotic stress. Biochem. J. 1992, 282, 69–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, L.R.; Poddar, N.K.; Dar, T.A.; Kumar, R.; Ahmad, F. Protein and DNA destabilization by osmolytes: The other side of the coin. Life Sci. 2011, 88, 117–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnoor, M.; Voß, P.; Cullen, P.; Böking, T.; Galla, H.-J.; Galinski, E.A.; Lorkowski, S. Characterization of the synthetic compatible solute homoectoine as a potent PCR enhancer. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2004, 322, 867–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kishitani, S.; Watanabe, K.; Yasuda, S.; Arakawa, K.; Takabe, T. Accumulation of glycinebetaine during cold acclimation and freezing tolerance in leaves of winter and spring barley plants. Plant Cell Environ. 1994, 17, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleland, D.; Krader, P.; McCree, C.; Tang, J.; Emerson, D. Glycine betaine as a cryoprotectant for prokaryotes. J. Microbiol. Methods 2004, 58, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obeid, R. The metabolic burden of methyl donor deficiency with focus on the betaine homocysteine methyltransferase pathway. Nutrients 2013, 5, 3481–3495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.; Deaciuc, I.; Zhou, Z.; Song, M.; Chen, T.; Hill, D.; McClain, C.J. Involvement of AMP-activated protein kinase in beneficial effects of betaine on high-sucrose diet-induced hepatic steatosis. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2007, 293, G894–G902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, I. Betaine is a positive regulator of mitochondrial respiration. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2015, 456, 621–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Yao, T.; Pini, M.; Zhou, Z.; Fantuzzi, G.; Song, Z. Betaine improved adipose tissue function in mice fed a high-fat diet: A mechanism for hepatoprotective effect of betaine in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2010, 298, G634–G642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilcken, D.E.; Wilcken, B.; Dudman, N.P.; Tyrrell, P.A. Homocystinuria—The effects of betaine in the treatment of patients not responsive to pyridoxine. N. Engl. J. Med. 1983, 309, 448–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.B.; Kooistra, M.; Zhang, B.; Slow, S.; Fortier, A.L.; Garrow, T.A.; Lever, M.; Trasler, J.M.; Baltz, J.M. Betaine homocysteine methyltransferase is active in the mouse blastocyst and promotes inner cell mass development. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 33094–33103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ratriyanto, A.; Mosenthin, R.; Bauer, E.; Eklund, M. Metabolic, osmoregulatory and nutritional functions of betaine in monogastric animals. Asian-Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 2009, 22, 1461–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virtanen, E.; Junnila, M.; Soivio, A. Effects of food containing betaine/amino acid additive on the osmotic adaptation of young Atlantic salmon, Salmo salar L. Aquaculture 1989, 83, 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altinisik, S.; Zeidan, H.; Yilmaz, M.D.; Marti, M.E. Reactive extraction of betaine from sugarbeet processing byproducts. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 11029–11038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krulj, J.; Jevtić-Mučibabić, R.; Grbić, J.; Brkljača, J.; Milovanović, I.; Filipčev, B.; Bodroža-Solarov, M. Determination of Betaine in Sugar Beet Molasses Određivanje Betaina U Melasi Šećerne Repe. J. Process. Energy Agric. 2014, 18, 179. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, A.N. Recovery of Betaine and Betaine Salts from Sugar Beet Wastes. 1945. Available online: https://patents.google.com/patent/US2375164A/en (accessed on 28 November 2025).

- Tukuljac, L.E.P.; Šereš, Z.I.; Kojić, J.S.; Maravić, N.R.; Ilić, N.M.; Perović, J.N.; Solarov, M.I.B. The effect of different pretreatments on betaine separation. Food Feed Res. 2018, 45, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strange, R.; Majer, J.; Smith, H. The isolation and identification of choline and betaine as the two major components in anthers and wheat germ that stimulate Fusarium graminearum In Vitro. Physiol. Plant Pathol. 1974, 4, 277–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorham, J. Separation and quantitative estimation of betaine esters by high-performance liquid chromatography. J. Chromatogr. A 1986, 361, 301–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asadi, M. Molasses-Desugaring Process. Beet-Sugar Handbook; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2005; pp. 517–546. [Google Scholar]

- Escudero, I.; Ruiz, M.O. Extraction of betaine from beet molasses using membrane contactors. J. Membr. Sci. 2011, 372, 258–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cibis, E.; Ryznar-Luty, A.; Krzywonos, M.; Lutosławski, K.; Miśkiewicz, T. Betaine removal during thermo-and mesophilic aerobic batch biodegradation of beet molasses vinasse: Influence of temperature and pH on the progress and efficiency of the process. J. Environ. Manag. 2011, 92, 1733–1739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, L.; Gao, J.; Zhang, Q.; Kong, F.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, Z.; Sun, C.; Lv, S. Research progress on deep eutectic solvents and recent applications. Processes 2023, 11, 1986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y.; Yao, C.; Wu, W. Deep eutectic solvents: Green solvents for separation applications. Acta Phys.-Chim. Sin 2018, 34, 873–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teles, A.R.R.; Capela, E.V.; Carmo, R.S.; Coutinho, J.A.; Silvestre, A.J.; Freire, M.G. Solvatochromic parameters of deep eutectic solvents formed by ammonium-based salts and carboxylic acids. Fluid Phase Equilibria 2017, 448, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abranches, D.O.; Silva, L.P.; Martins, M.A.; Pinho, S.P.; Coutinho, J.A. Understanding the formation of deep eutectic solvents: Betaine as a universal hydrogen bond acceptor. ChemSusChem 2020, 13, 4916–4921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spittle, S.; Poe, D.; Doherty, B.; Kolodziej, C.; Heroux, L.; Haque, M.A.; Squire, H.; Cosby, T.; Zhang, Y.; Fraenza, C. Evolution of microscopic heterogeneity and dynamics in choline chloride-based deep eutectic solvents. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaibuna, M.; Theresa, L.V.; Sreekumar, K. Neoteric deep eutectic solvents: History, recent developments, and catalytic applications. Soft Matter 2022, 18, 2695–2721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skarpalezos, D.; Detsi, A. Deep eutectic solvents as extraction media for valuable flavonoids from natural sources. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 4169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; Witkamp, G.-J.; Verpoorte, R.; Choi, Y.H. Tailoring properties of natural deep eutectic solvents with water to facilitate their applications. Food Chem. 2015, 187, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, V.I.; Craveiro, R.; Silva, J.M.; Reis, R.L.; Paiva, A.; Duarte, A.R.C. Natural deep eutectic systems as alternative nontoxic cryoprotective agents. Cryobiology 2018, 83, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Florindo, C.; Oliveira, F.S.; Rebelo, L.P.N.; Fernandes, A.M.; Marrucho, I.M. Insights into the synthesis and properties of deep eutectic solvents based on cholinium chloride and carboxylic acids. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2014, 2, 2416–2425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ijardar, S.P.; Singh, V.; Gardas, R.L. Revisiting the physicochemical properties and applications of deep eutectic solvents. Molecules 2022, 27, 1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, F.; Zheng, Q.; Tan, H.; Wang, X. Insight into the role of hydrogen bond donor in deep eutectic solvents. J. Mol. Liq. 2024, 399, 124332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mero, A.; Koutsoumpos, S.; Giannios, P.; Stavrakas, I.; Moutzouris, K.; Mezzetta, A.; Guazzelli, L. Comparison of physicochemical and thermal properties of choline chloride and betaine-based deep eutectic solvents: The influence of hydrogen bond acceptor and hydrogen bond donor nature and their molar ratios. J. Mol. Liq. 2023, 377, 121563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vorobyova, V.; Skiba, M.; Vinnichuk, K.; Linyucheva, O.; Vasyliev, G. Influence of hydrogen bond donor compound type on the properties of betaine based deep eutectic solvents: A computational and experimental approach. J. Mol. Struct. 2025, 1323, 140743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.B.; Mr, V.S.K.; Chaudhary, M.; Singh, P. A mini review on synthesis, properties and applications of deep eutectic solvents. J. Indian Chem. Soc. 2021, 98, 100210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurkan, B.; Squire, H.; Pentzer, E. Metal-free deep eutectic solvents: Preparation, physical properties, and significance. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2019, 10, 7956–7964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, K.; Ren, J.; Wang, Q.; Nuerjiang, M.; Xia, X.; Bian, C. Research progress on the preparation and action mechanism of natural deep eutectic solvents and their application in food. Foods 2022, 11, 3528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajardo-Parra, N.F.; Meneses, L.; Duarte, A.R.C.; Paiva, A.; Held, C. Assessing the influence of betaine-based natural deep eutectic systems on horseradish peroxidase. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 12873–12881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.-E.; Jun, S.-H.; Ryoo, J.-Y.; Kang, N.-G. Formulation of Ascorbic Acid and Betaine-based Therapeutic Deep Eutectic System for Enhanced Transdermal Delivery of Ascorbic Acid. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, N.; Wang, Y.; Xu, K.; Huang, Y.; Wen, Q.; Ding, X. Development of green betaine-based deep eutectic solvent aqueous two-phase system for the extraction of protein. Talanta 2016, 152, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; He, N.; Fan, J.; Song, F. Physical properties of betaine-1, 2-propanediol-based deep eutectic solvents. Polymers 2022, 14, 1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutiérrez, A.; Alcalde, R.; Atilhan, M.; Aparicio, S. Insights on betaine+ lactic acid deep eutectic solvent. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2020, 59, 11880–11892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Yu, D.; Chen, Y.; Shi, R.; Zhou, F.; Mu, T. High-resolution thermogravimetric analysis is required for evaluating the thermal stability of deep eutectic solvents. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2022, 61, 14347–14354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahavishnu, G.; Malaiyarasan, V.; Kannaiyan, S.K.; Ramalingam, A. Investigation of molecular polarity and thermal stability of monoethanolamine based deep eutectic solvents. J. Dispers. Sci. Technol. 2024, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasil’eva, I.; Morozova, O.; Shumakovich, G.; Yaropolov, A. Betaine-based deep eutectic solvent as a new media for laccase-catalyzed template-guided polymerization/copolymerization of aniline and 3-aminobenzoic acid. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 11409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolmachev, D.; Lukasheva, N.; Ramazanov, R.; Nazarychev, V.; Borzdun, N.; Volgin, I.; Andreeva, M.; Glova, A.; Melnikova, S.; Dobrovskiy, A. Computer simulations of deep eutectic solvents: Challenges, solutions, and perspectives. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; Van Spronsen, J.; Witkamp, G.-J.; Verpoorte, R.; Choi, Y.H. Natural deep eutectic solvents as new potential media for green technology. Anal. Chim. Acta 2013, 766, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, K.M.; Ko, J.; Zhao, J.; Jin, Y.; Han, S.Y.; Lee, J. Multi-functioning deep eutectic solvents as extraction and storage media for bioactive natural products that are readily applicable to cosmetic products. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 151, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zainal-Abidin, M.H.; Hayyan, M.; Hayyan, A.; Jayakumar, N.S. New horizons in the extraction of bioactive compounds using deep eutectic solvents: A review. Anal. Chim. Acta 2017, 979, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiecco, M.; Cappellini, F.; Nicoletti, F.; Del Giacco, T.; Germani, R.; Di Profio, P. Role of the hydrogen bond donor component for a proper development of novel hydrophobic deep eutectic solvents. J. Mol. Liq. 2019, 281, 423–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espino, M.; de los Ángeles Fernández, M.; Gomez, F.J.; Silva, M.F. Natural designer solvents for greening analytical chemistry. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2016, 76, 126–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, D.; Li, D.; Chen, B.; Luo, B.; Huang, Y.; Shi, W. 2D–2D SnS2/covalent organic framework heterojunction photocatalysts for highly enhanced solar-driven hydrogen evolution without cocatalysts. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 14238–14248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aroso, I.M.; Paiva, A.; Reis, R.L.; Duarte, A.R.C. Natural deep eutectic solvents from choline chloride and betaine–Physicochemical properties. J. Mol. Liq. 2017, 241, 654–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhamarnah, Y.; Qiblawey, H.; Nasser, M.S.; Benamor, A. Thermo-rheological characterization of malic acid based natural deep eutectic solvents. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 708, 134848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rumyantsev, M.; Rumyantsev, S.; Kalagaev, I.Y. Effect of water on the activation thermodynamics of deep eutectic solvents based on carboxybetaine and choline. J. Phys. Chem. B 2018, 122, 5951–5960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, L.; Fan, W.; Mei, Y.; Liu, L.; Li, L.; Wang, Z.; Yang, L. Mechanochemical assisted extraction as a green approach in preparation of bioactive components extraction from natural products-A review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 129, 98–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanović, M.; Islamčević Razboršek, M.; Kolar, M. Innovative extraction techniques using deep eutectic solvents and analytical methods for the isolation and characterization of natural bioactive compounds from plant material. Plants 2020, 9, 1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pai, S.; Hebbar, A.; Selvaraj, S. A critical look at challenges and future scopes of bioactive compounds and their incorporations in the food, energy, and pharmaceutical sector. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 35518–35541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, C.; Sarraguça, M. A Comprehensive Review on Deep Eutectic Solvents and Its Use to Extract Bioactive Compounds of Pharmaceutical Interest. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dheyab, A.S.; Abu Bakar, M.F.; AlOmar, M.; Sabran, S.F.; Muhamad Hanafi, A.F.; Mohamad, A. Deep eutectic solvents (DESs) as green extraction media of beneficial bioactive phytochemicals. Separations 2021, 8, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, A.K.; Sit, N. Extraction of bioactive compounds from plant materials using combination of various novel methods: A review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 119, 579–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulia, K.; Adam, D.; Zahrina, I.; Krisanti, E.A. Green extraction of palmitic acid from palm oil using betaine-based Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents. Int. J. Technol. 2018, 9, 335–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Z.; Wang, N.; Li, Q. Ultrasonic assisted extraction of coumarins from Angelicae Pubescentis Radix by betaine-based natural deep eutectic solvents. Arab. J. Chem. 2024, 17, 105542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanali, C.; Della Posta, S.; Dugo, L.; Gentili, A.; Mondello, L.; De Gara, L. Choline-chloride and betaine-based deep eutectic solvents for green extraction of nutraceutical compounds from spent coffee ground. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2020, 189, 113421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, G.; Pastre, J. Microwave-assisted HMF production from water-soluble sugars using betaine-based natural deep eutectic solvents (NADES). Sustain. Energy Fuels 2020, 4, 1891–1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Xie, Q.; Liu, Q.; Liu, J.; Wan, C.; Liang, D.; Zhang, H. Separation of phenolic compounds from oil mixtures by betaine-based deep eutectic solvents. Asia-Pac. J. Chem. Eng. 2020, 15, e2515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, L.A.; Leonardo, I.C.; Gaspar, F.B.; Roseiro, L.C.; Duarte, A.R.C.; Matias, A.A.; Paiva, A. Unveiling the potential of betaine/polyol-based deep eutectic systems for the recovery of bioactive protein derivative-rich extracts from sardine processing residues. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2021, 276, 119267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi, A.; Pazuki, G.R. Separation of heavy metals using aqueous two-phase systems based on choline chloride/urea and betaine/urea deep eutectic solvents. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 3948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Wei, J.; Ge, H.; Yan, Z.; Jiang, M.; Lu, J.; Pu, M.; Li, B.; Xu, H. Molecular simulation and machine learning assisted in exploring betaine-based deep eutectic solvent extraction of active compounds from peony petals. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 361, 131550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, H.; Ding, S.; Xue, S.; Liu, S.; Wu, Q.; Zhang, Q. Capillary electrophoresis separations with Betaine: Urea, a deep eutectic solvent as the separation medium. Anal. Chim. Acta 2025, 1336, 343467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertolo, M.R.; Oliveira, L.F.R.; Titato, G.M.; Lanças, F.M.; Correa, D.S. Sustainable extraction of value-added compounds from orange waste using natural deep eutectic solvents. J. Mol. Liq. 2025, 431, 127703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Hao, J.-W.; Mo, L.-P.; Zhang, Z.-H. Recent advances in the application of deep eutectic solvents as sustainable media as well as catalysts in organic reactions. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 48675–48704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnodo, D.; Maffeis, E.; Marra, F.; Nejrotti, S.; Prandi, C. Combination of enzymes and deep eutectic solvents as powerful toolbox for organic synthesis. Molecules 2023, 28, 516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buzatu, A.R.; Todea, A.; Peter, F.; Boeriu, C.G. The Role of Reactive Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents in Sustainable Biocatalysis. ChemCatChem 2024, 16, e202301597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guajardo, N.; Müller, C.R.; Schrebler, R.; Carlesi, C.; Domínguez de María, P. Deep eutectic solvents for organocatalysis, biotransformations, and multistep organocatalyst/enzyme combinations. ChemCatChem 2016, 8, 1020–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez, M.S.; Longo, M.A.; Rodríguez, A.; Deive, F.J. The role of deep eutectic solvents in catalysis. A vision on their contribution to homogeneous, heterogeneous and electrocatalytic processes. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2024, 132, 36–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Gu, Q.; Zhou, J.; Liu, X.; Yu, X. High-value bioconversion of ginseng extracts in betaine-based deep eutectic solvents for the preparation of deglycosylated ginsenosides. Foods 2023, 12, 496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Duan, W.; An, X.; Qiao, Y.; Tian, Y.; Zhou, H. Novel betaine-amino acid based natural deep eutectic solvents for enhancing the enzymatic hydrolysis of corncob. Bioresour. Technol. 2020, 310, 123389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, I.; Syakfanaya, A.M.; Azminah, A.; Saputri, F.C.; Mun’im, A. Optimization of betaine-sorbitol natural deep eutectic solvent-based ultrasound-assisted extraction and pancreatic lipase inhibitory activity of chlorogenic acid and caffeine content from robusta green coffee beans. Heliyon 2021, 7, e07702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasanah, N.F.; Darmawan, M.A.; Bahua, H.; Hidayat, H.; Rosadi, D.; Abidin, K.Y.; Pradiva, M.I.; Rosjidi, M. Oil Palm Trunks as Raw Material for Bioethanol Production: A Study on the Delignification Efficiency of Betaine-Based Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents. Waste Biomass Valorization 2025, 16, 5197–5212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Zuo, J.; Xu, H.; Gao, S.; He, Y. Pretreatment of wheat straw with alkali-assisted betaine-based deep eutectic solvents improves saccharification efficiency. Sustain. Chem. Pharm. 2025, 46, 102068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Ao, F.; Ge, X.; Shen, W. Food-grade Pickering emulsions: Preparation, stabilization and applications. Molecules 2020, 25, 3202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, H.; Paiva, A.; Duarte, A.R.C.; Galamba, N. Structure and dynamic properties of a glycerol–betaine deep eutectic solvent: When does a DES become an aqueous solution? ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 3501–3512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikodijević, M.M.; Troter, D.Z.; Konstantinović, S.S. Dyeing of polyester fabric using a natural deep eutectic solvent. Adv. Technol. 2024, 13, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.-j.; Lou, L.; Huang, Q.; Xu, W.; Li, H. Ultrasonic extraction and purification of scutellarin from Erigerontis Herba using deep eutectic solvent. Ultrason. Sonochemistry 2023, 99, 106560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivares, B.; Martínez, F.A.; Ezquer, M.; Morales, B.J.; Fuentes, I.; Calvo, M.; Campodónico, P.R. Betaine-urea deep eutectic solvent improves imipenem antibiotic activity. J. Mol. Liq. 2022, 350, 118551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, C.-X.; Qi, S.-J.; Xin, R.-P.; Yang, B.; Wang, Y.-H. Synergistic behavior of betaine–urea mixture: Formation of deep eutectic solvent. J. Mol. Liq. 2016, 219, 74–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardellini, F.; Tiecco, M.; Germani, R.; Cardinali, G.; Corte, L.; Roscini, L.; Spreti, N. Novel zwitterionic deep eutectic solvents from trimethylglycine and carboxylic acids: Characterization of their properties and their toxicity. RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 55990–56002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Z.; Li, J.; Zhou, J.; Chen, Y.; Cui, Z. Extraction of chlorogenic acid from Lonicera japonica Thunb. using deep eutectic solvents: Process optimization and mechanism exploration by the combination of experiment and molecular simulation. Microchem. J. 2025, 212, 113280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cysewski, P.; Jeliński, T.; Przybyłek, M. Exploration of the Solubility Hyperspace of Selected Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients in Choline-and Betaine-Based Deep Eutectic Solvents: Machine Learning Modeling and Experimental Validation. Molecules 2024, 29, 4894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janbezar, E.; Shekaari, H.; Bagheri, M. Gabapentin drug interactions in water and aqueous solutions of green betaine based compounds through volumetric, viscometric and interfacial properties. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 16813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Aguirre, O.A.; Muro, C.; Hernández-Acosta, E.; Alvarado, Y.; Díaz-Nava, M.d.C. Extraction and stabilization of betalains from beetroot (Beta vulgaris) wastes using deep eutectic solvents. Molecules 2021, 26, 6342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negi, T.; Kumar, A.; Sharma, S.K.; Rawat, N.; Saini, D.; Sirohi, R.; Prakash, O.; Dubey, A.; Dutta, A.; Shahi, N.C. Deep eutectic solvents: Preparation, properties, and food applications. Heliyon 2024, 10, e28784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Muñoz, R.; Can Karaça, A.; Saeed Kharazmi, M.; Boczkaj, G.; Hernández-Pinto, F.J.; Anusha Siddiqui, S.; Jafari, S.M. Deep eutectic solvents for the food industry: Extraction, processing, analysis, and packaging applications–a review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2024, 64, 10970–10986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vinci, G.; Maddaloni, L.; Prencipe, S.A.; Orlandini, E.; Sambucci, M. Simple and reliable eco-extraction of bioactive compounds from dark chocolate by Deep Eutectic Solvents. A sustainable study. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 58, 4051–4065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, E.; Yokota, Y.; Urakawa, M.; Usuki, T. Extraction of oleanolic acid from wine pomace using betaine-based deep eutectic solvents. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2024, 250, 2053–2058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Ortega, L.A.; Kumar-Patra, J.; Kerry, R.G.; Das, G.; Mota-Morales, J.D.; Heredia, J.B. Synergistic Antioxidant Activity in Deep Eutectic Solvents: Extracting and Enhancing Natural Products. ACS Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 4, 2776–2798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, H.; Zhu, Z.; Sun, D.-W. Deep eutectic solvents (DESs) films based on gelatin as active packaging for moisture regulation in fruit preservation. Food Chem. 2024, 439, 138114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roselli, V.; Leuci, R.; Pugliese, G.; Barbarossa, A.; Laghezza, A.; Paparella, M.; Carocci, A.; Tufarelli, V.; Gambacorta, L.; Piemontese, L. Deep Eutectic Solvents (DESs) as Alternative Sustainable Media for the Extraction and Characterization of Bioactive Compounds from Winemaking Industry Wastes. Molecules 2025, 30, 1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Y.; Yang, W.; Zhan, J.; Pu, C.; Zhong, L.; Hou, H. Eutectogels: Recent Advances and Emerging Biological Applications. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, 35, 2425778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, K.; Ning, H.; Liu, H.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, S. Preparation, Properties, and Applications of Eutectogels. Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 2025, 651, 2500039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arjunan, K.K.; Weng, C.-Y.; Sheng, Y.-J.; Tsao, H.-K. Formation of Self-Healing Granular Eutectogels through Jammed Carbopol Microgels in Supercooled Deep Eutectic Solvent. Langmuir 2024, 40, 17081–17089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vorobyova, V.; Skiba, M.; Vinnichuk, K.; Vasyliev, G. Synthesis of gold nanoparticles using deep eutectic solvents and their incorporation into polyvinyl alcohol–based eutectogels: Structural, chemical, and functional analysis. Colloid Polym. Sci. 2025, 303, 1213–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Shen, J.; Gao, P.; Jiang, Q.; Xia, W. Sustainable chitosan films containing a betaine-based deep eutectic solvent and lignin: Physicochemical, antioxidant, and antimicrobial properties. Food Hydrocoll. 2022, 129, 107656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zdanowicz, M. Influence of Urea Content in Deep Eutectic Solvents on Thermoplastic Starch Films’ Properties. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, H.; Fan, Y.; Lu, D.; Yang, H.; Zou, Y.; Wang, X.; Ji, X.; Si, C. Preparation of zwitterionic cellulose nanofibers with betaine-oxalic acid DES and its multiple performance characteristics. Cellulose 2023, 30, 10953–10969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowacki, K.; Wysokowski, M.; Galiński, M. Synthesis and characterization of betaine-based natural deep eutectic solvents for electrochemical application. J. Mol. Liq. 2025, 424, 127071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulia, K.; Krisanti, E.; Libriandy, E. Betaine-based deep eutectic solvents with diol, acid and amine hydrogen bond donors for carbon dioxide absorption. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2019, 1295, 012039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Zhou, X.; Guo, S.; Li, S. study on carbon dioxide capture using ternary betaine-based deep eutectic solvents. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 51031–51039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jangir, A.K.; Verma, G.; Pandey, S.; Kuperkar, K. Design and thermophysical characterization of betaine hydrochloride-based deep eutectic solvents as a new platform for CO2 capture. New J. Chem. 2022, 46, 5332–5345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, S.; Gupta, A.; Kashyap, H.K. How hydration affects the microscopic structural morphology in a deep eutectic solvent. J. Phys. Chem. B 2020, 124, 2230–2237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islam, S.; Rubio, C.; Rafikova, K.; Mutelet, F. Desulfurization and Denitrogenation Using Betaine-Based Deep Eutectic Solvents. J. Chem. Eng. Data 2024, 69, 2244–2254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del Mar Contreras-Gámez, M.; Galán-Martín, Á.; Seixas, N.; da Costa Lopes, A.M.; Silvestre, A.; Castro, E. Deep eutectic solvents for improved biomass pretreatment: Current status and future prospective towards sustainable processes. Bioresour. Technol. 2023, 369, 128396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Procentese, A.; Raganati, F.; Olivieri, G.; Russo, M.E.; Rehmann, L.; Marzocchella, A. Low-energy biomass pretreatment with deep eutectic solvents for bio-butanol production. Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 243, 464–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira Sanches, M.; Freitas, R.; Oliva, M.; Mero, A.; De Marchi, L.; Cuccaro, A.; Fumagalli, G.; Mezzetta, A.; Colombo Dugoni, G.; Ferro, M. Are natural deep eutectic solvents always a sustainable option? A bioassay-based study. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 17268–17279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayyan, M.; Hashim, M.A.; Hayyan, A.; Al-Saadi, M.A.; AlNashef, I.M.; Mirghani, M.E.; Saheed, O.K. Are deep eutectic solvents benign or toxic? Chemosphere 2013, 90, 2193–2195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radošević, K.; Čanak, I.; Panić, M.; Markov, K.; Bubalo, M.C.; Frece, J.; Srček, V.G.; Redovniković, I.R. Antimicrobial, cytotoxic and antioxidative evaluation of natural deep eutectic solvents. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2018, 25, 14188–14196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapeña, D.; Errazquin, D.; Lomba, L.; Lafuente, C.; Giner, B. Ecotoxicity and biodegradability of pure and aqueous mixtures of deep eutectic solvents: Glyceline, ethaline, and reline. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 8812–8821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juneidi, I.; Hayyan, M.; Hashim, M.A. Evaluation of toxicity and biodegradability for cholinium-based deep eutectic solvents. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 83636–83647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardellini, F.; Germani, R.; Cardinali, G.; Corte, L.; Roscini, L.; Spreti, N.; Tiecco, M. Room temperature deep eutectic solvents of (1 S)-(+)-10-camphorsulfonic acid and sulfobetaines: Hydrogen bond-based mixtures with low ionicity and structure-dependent toxicity. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 31772–31786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayyan, M.; Mbous, Y.P.; Looi, C.Y.; Wong, W.F.; Hayyan, A.; Salleh, Z.; Mohd-Ali, O. Natural deep eutectic solvents: Cytotoxic profile. SpringerPlus 2016, 5, 913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayyan, M.; Looi, C.Y.; Hayyan, A.; Wong, W.F.; Hashim, M.A. In Vitro and In Vivo toxicity profiling of ammonium-based deep eutectic solvents. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0117934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez-Argüello, P.; Martín-Esteban, A. Ecotoxicological assessment of different choline chloride-based natural deep eutectic solvents: In Vitro and In Vivo approaches. Environ. Res. 2025, 284, 122202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Q.; Chen, J.-X.; Tang, Y.-L.; Wang, J.; Yang, Z. Assessing the toxicity and biodegradability of deep eutectic solvents. Chemosphere 2015, 132, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radošević, K.; Bubalo, M.C.; Srček, V.G.; Grgas, D.; Dragičević, T.L.; Redovniković, I.R. Evaluation of toxicity and biodegradability of choline chloride based deep eutectic solvents. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2015, 112, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Union. Regulation (EC) No 1223/2009 of the european parliament and of the council. Off. J. Eur. Union L 2009, 342, 59. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, K.; Pronczuk, A.; Cook, M.W.; Robbins, M.C. Betaine in sub-acute and sub-chronic rat studies. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2003, 41, 1685–1700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benlebna, M.; Ruesgas-Ramón, M.; Bonafos, B.; Fouret, G.; Casas, F.; Coudray, C.; Durand, E.; Cruz Figueroa-Espinoza, M.; Feillet-Coudray, C. Toxicity of natural deep eutectic solvent betaine: Glycerol in rats. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2018, 66, 6205–6212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagadeeswaran, I.; Sriram, H. EU 1907/2006–Registration, Evaluation, Authorisation and Restriction of Chemicals. In Medical Device Guidelines and Regulations Handbook; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 237–260. [Google Scholar]

- Meredith, L.; Elbourne, A.; Greaves, T.L.; Bryant, G.; Bryant, S.J. Physico-chemical characterisation of glycerol-and ethylene glycol-based deep eutectic solvents. J. Mol. Liq. 2024, 394, 123777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Scientific Name | Trimethyl Glycine |

|---|---|

| Chemical Formula | C5H11NO2 |

| Molar Weight | 117.15 g/mol |

| Natural Resources | Beets (Beta vulgaris), wheat bran, wheat germ, spinach, microorganisms, aquatic invertebrates |

| Color | White hygroscopic crystals |

| Taste | Sweet |

| pKa | 1.83 at 0 °C |

| Melting Point | 293 °C (decomposes) |

| Solubility (g/100 g solvent) | Water: 160 Methanol: 57 Ethanol: 8.7 |

| Aqueous Solution | Clear and colorless |

| Food Item | BET Content (mg/100 g) | Food Item | BET Content (mg/100 g) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wheat Bran | 1200–1300 | Rye Bread | 250–400 |

| Wheat Germ | ~1200 | Whole Wheat Bread | 150–400 |

| Spinach (raw) | 600–645 | Pasta (whole wheat) | 100–250 |

| Beets (raw) | 175–300 (Up to 750 µg/g dry wt) | Shrimp | 1000–2000 |

| Quinoa (cooked) | 150–200 | Clams | 200–900 |

| Mussels | 1100–2000 | Sweet Potato | 35–50 |

| Oysters | 400–900 | Turkey Breast | 45–75 |

| Veal | 60–80 | Beef | 20–50 |

| Fields | Applications | References |

|---|---|---|

| Chemical | - Osmolyte in cell volume regulation | [75] |

| - Stabilizes protein/DNA as a chemical chaperone | [76] | |

| - PCR enhancer | [77] | |

| - Cold acclimation in the plant | [78] | |

| - Cryoprotectant for microorganism storage | [79] | |

| - Surfactant | [62] | |

| Metabolic | - Methyl donor in the methionine cycle | [80] |

| - Activation of hepatic AMP-activated protein kinase | [81] | |

| - Preservation of mitochondrial function | [82] | |

| - Improves insulin sensitivity of adipose tissue | [83] | |

| Clinical Medicine | - Decreases plasma homocysteine in patients with homocystinuria | [84] |

| - Promotes viability and development of mouse blastocysts | [85] | |

| - Reduces injury and improves liver function in animal models with liver disease involving fatty liver. The human application remains speculative | [8] | |

| Agriculture | - Increase lean muscle mass in livestock (e.g., pigs, poultry) | [86] |

| - Salmon farming | [87] |

| Method | Extraction Efficiency (%) | Stripping/Recovery (%) | Purity (%) | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reactive Extraction (DNNDSA) | 67–71 | 47–54 | Moderate | High efficiency, easy, economical |

| Alcohol Extraction + Crystallization | ~40–45 (dry matter) | Not specified | High | Reduced acid use, avoids impurities |

| Chromatographic Separation | >80 | Not specified | ~99.8 | High yield, high purity, industrial |

| Membrane Technology | 66–91 (stripping) | 66–91 | Moderate | Continuous, selective, low energy |

| DES Components | Molar Ratio | Key Finding/Applications | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Component 1 | Component 2 | |||

| BET | 1,2-Propanediol | 1:3 1:4 1:5 |

| [138] |

| 1,3-Propanediol | ||||

| 1,2-Butanediol | ||||

| 1,3-Butanediol | ||||

| 1,4-Butanediol | ||||

| Ethylene Glycol | ||||

| Glycerol | ||||

| BET | 1,2-Propanediol | 1:3 1:5 1:7 |

| [10] |

| 1,3-Propanediol | ||||

| 1,2-Butanediol | ||||

| 1,3-Butanediol | ||||

| 1,4-Butanediol | ||||

| Levulinic acid | ||||

| Lactic acid | ||||

| Choline Chloride | Urea | 1:2 |

| [140] |

| Citric acid | ||||

| Lactic acid | ||||

| Glucose | ||||

| Sorbitol | ||||

| Xylitol | ||||

| Glycerol | ||||

| 1,6-Hexanediol | 1:7 | |||

| Triethylene glycol | 1:2 | |||

| Ethylene glycol | ||||

| Propylene glycol | ||||

| BET | Lactic acid | |||

| Glycerol | ||||

| Ethylene glycol | ||||

| Triethylene glycol | ||||

| BET Hydrochloride (BHC) | Citric acid: H2O | 1:1:1 |

| [141] |

| Tartaric acid: H2O | ||||

| Malic acid: H2O | ||||

| Lactic acid: H2O | ||||

| Glycolic acid: H2O | ||||

| BET | Glycerol | 1:2 |

| [142] |

| DL-lactic acid | 1:2 | |||

| Levulinic acid | 1:2 | |||

| BET | Ethylene glycol | 1:4 |

| [139] |

| Glycerol | 1:2 | |||

| BET | Glycerol Glycerol: Water | 1:2 1:2:1 1:2:5 1:2:10 |

| [143] |

| Propylene glycol Propylene glycol: Water | 1:3 1:3:1 1:3:5 1:3:10 | |||

| Ethylene glycol Ethylene glycol: Water | 1:3 1:3:1 1:3:5 1:3:10 | |||

| BET | Urea | 1:2 |

| [144] |

| Glycerol | 1:1 | |||

| BET | Ethylene glycol | 1:4 |

| [145] |

| 1,2-propanediol | 1:4 | |||

| Lactic acid | 1:2 | |||

| Levulinic acid | 1:2 | |||

| BET | Urea: H2O | 1:2:2 |

| [146] |

| BET | Lactic acid | 1:2 |

| [147] |

| Glycerol | 1:2 | |||

| Ethylene glycol | 1:2 | |||

| Urea | 1:2 | |||

| DES Components | Abbreviation | Molar Ratio | Key Finding/Applications | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Component 1 | Component 2 | ||||

| Choline Chloride | 1,2-Propanediol | ChCl: P | 1:2 |

| [153] |

| Urea | ChCl: U | 1:2 | |||

| Ethylene glycol | ChCl: EG | 1:2 | |||

| 1,4-Butanediol | ChCl: B | 1:2 | |||

| Glycerol | ChCl: G | 1:1 & 1:2 | |||

| Citric acid | ChCl: Ca | 1:1 | |||

| D-Glucitol | ChCl: Dg | 1:1 | |||

| Malic acid | ChCl: Ma | 1:1 | |||

| Xylitol | ChCl: X | 1:2 | |||

| Glucose | ChCl: Glu | 5:2 | |||

| Malic acid: Xylitol | ChCl: Ma: X | 1:1:1 | |||

| Urea: Glycerol | ChCl: U: G | 1:1:1 | |||

| Betaine | Xylitol | BET: X | 1:2 & 1:1 & 2:1 | ||

| Glycerol | BET: G | 1:1 & 1:2 | |||

| Citric acid | BET: Ca | 1:1 | |||

| Ethylene glycol | BET: EG | 1:2 | |||

| Urea | BET: U | 1:2 | |||

| Malic acid | BET: Ma | 1:1 | |||

| Glucose | BET: Glu | 5:2 | |||

| Malic acid: Glucose | BET: Ma: Glu | 1:1:1 | |||

| Lysine | BET: Lys | 1:1 |

| [154] | |

| Arginine | BET: Arg | 1:1 | |||

| Histidine | BET: His | 1:1 | |||

| Sorbitol | BET: S | 1.25:1.2 |

| [155] | |

| lactic acid | BET: La | 1:2 |

| [156] | |

| Glycerol | BET: G | 1:2 | |||

| Formic acid | BET: FA | 1:2 |

| [157] | |

| Citric acid: water | BET: CA: W | 1:2:3 | |||

| Malic acid: water | BET: Ma: W | 1:2:2 | |||

| Polyethylene glycol 400: water | BET: PEG: W | 1:2:4 | |||

| Propylene glycol | BET: PG | 1:2 | |||

| Sorbitol: water | BET: SO: W | 1:2:3 | |||

| Methylurea: water | BET: ME: W | 1:2:1 | |||

| Acetamide: water | BET: AC: W | 1:2:1 | |||

| N-(2-hydroxyethyl) Ethylenediamine: water | BET: NE: W | 1:2:4 | |||

| DES Components | Molar Ratio | Key Finding/Applications | References | |

| Component 1 | Component 2 | |||

| BET | Benzoic | 1:2 |

| [164] |

| 2-Hydroxybenzoic (salicylic) | ||||

| 4-Chlorobenzoic | ||||

| 2-Chlorobenzoic | ||||

| 3-Chlorobenzoic | ||||

| 2-Furoic | ||||

| Phenylacetic | ||||

| D-(+)-Mandelic | ||||

| Glycolic | ||||

| Oxalic | ||||

| Citric | ||||

| Urea | 1:1 1:1.5 1:2 1:2.5 |

| [163] | |

| Glycerol | 1:2 |

| [165] | |

| 1,3-Propanediol | 1:2 | |||

| Ethylene Glycol | 1:2 | |||

| Lactic acid | 1:1 | |||

| Urea | 1:2 |

| [167] | |

| Ascorbic acid: water | 1:3:8 1:1:2 5:1:8 |

| [115] | |

| DES Components | Molar Ratio | Key Finding/Applications | References | |

| Component 1 | Component 2 | |||

| BET | Xylitol | 3:2 |

| [172] |

| Glucose | 5:2 |

| [173] | |

| Malic acid | 1:1 | |||

| Malic acid: proline | 1:1:1 | |||

| Malic acid: glucose | 1:1:1 | |||

| glycerol | 1:2 | |||

| Polyethylene glycol | 1:3 | |||

| ethylene glycol | 1:3 | |||

| Sorbitol: water | 1:1:3 | |||

| Glycerol | 1:2 |

| [174] | |

| Glycerol | 1:4:40% water |

| [175] | |

| Lactic acid | 1:4:40% water | |||

| Ascorbic acid | 2:1:40% water | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Allahyari, A.; Borji, M.; Jahanban-Esfahlan, A.; Khanalipour, A.; Tabibiazar, M.; Ahmadi, P. Current Status and Future Perspectives of Betaine and Betaine-Based Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents: A Review. Foods 2025, 14, 4122. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234122

Allahyari A, Borji M, Jahanban-Esfahlan A, Khanalipour A, Tabibiazar M, Ahmadi P. Current Status and Future Perspectives of Betaine and Betaine-Based Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents: A Review. Foods. 2025; 14(23):4122. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234122

Chicago/Turabian StyleAllahyari, Aylin, Maryam Borji, Ali Jahanban-Esfahlan, Ali Khanalipour, Mahnaz Tabibiazar, and Parisa Ahmadi. 2025. "Current Status and Future Perspectives of Betaine and Betaine-Based Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents: A Review" Foods 14, no. 23: 4122. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234122

APA StyleAllahyari, A., Borji, M., Jahanban-Esfahlan, A., Khanalipour, A., Tabibiazar, M., & Ahmadi, P. (2025). Current Status and Future Perspectives of Betaine and Betaine-Based Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents: A Review. Foods, 14(23), 4122. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234122