AraR Transcription Factor Affects the Sugar Metabolism and Acid Tolerance of Lactiplantibacillus plantarum

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Bacterial Strains, Plasmids, and Culture Conditions

2.2. Construction of LP_RS14895 Plasmids and Strains

2.3. Acid Tolerance

2.4. Comparison of Sugar Concentrations Between the Wild-Type and Mutant Strains in MRSC Medium via Hplc

2.5. Real-Time Quantitative PCR Analysis of the LP_RS14895 Gene and Capsular Polysaccharide Biosynthesis

2.6. DNA Affinity Purification Sequencing (DAP-Seq)

2.7. RNA-Seq Analysis

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

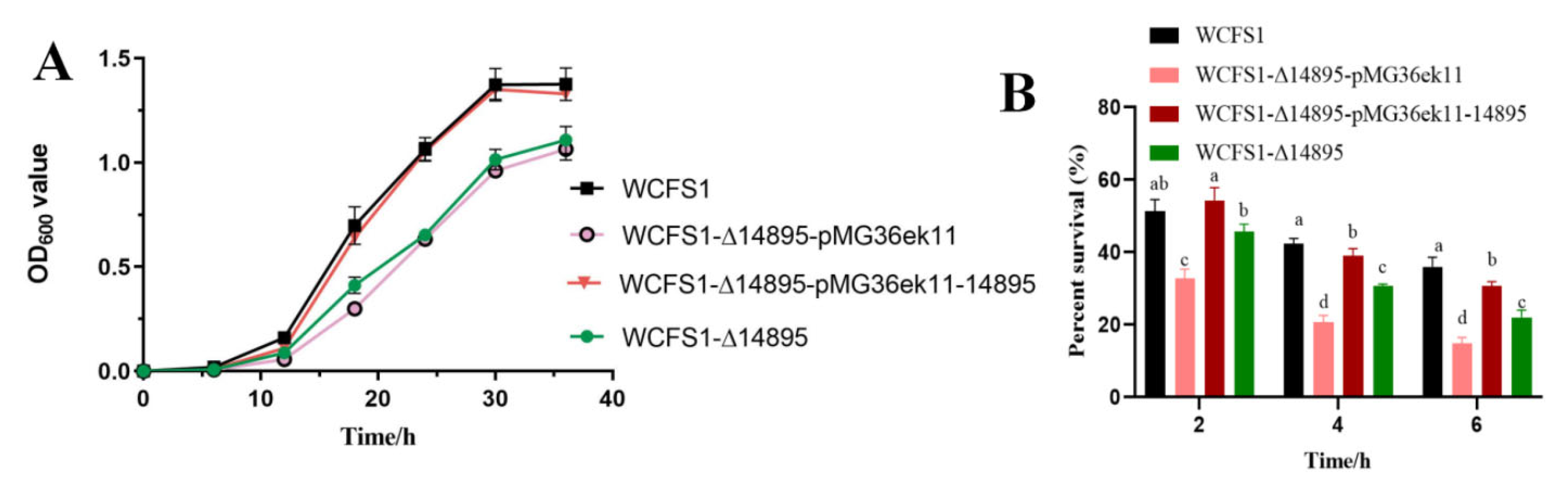

3.1. LP_RS14895 Functions as an AraR Transcriptional Regulator to Increase Acid Stress Tolerance in L. plantarum WCFS1

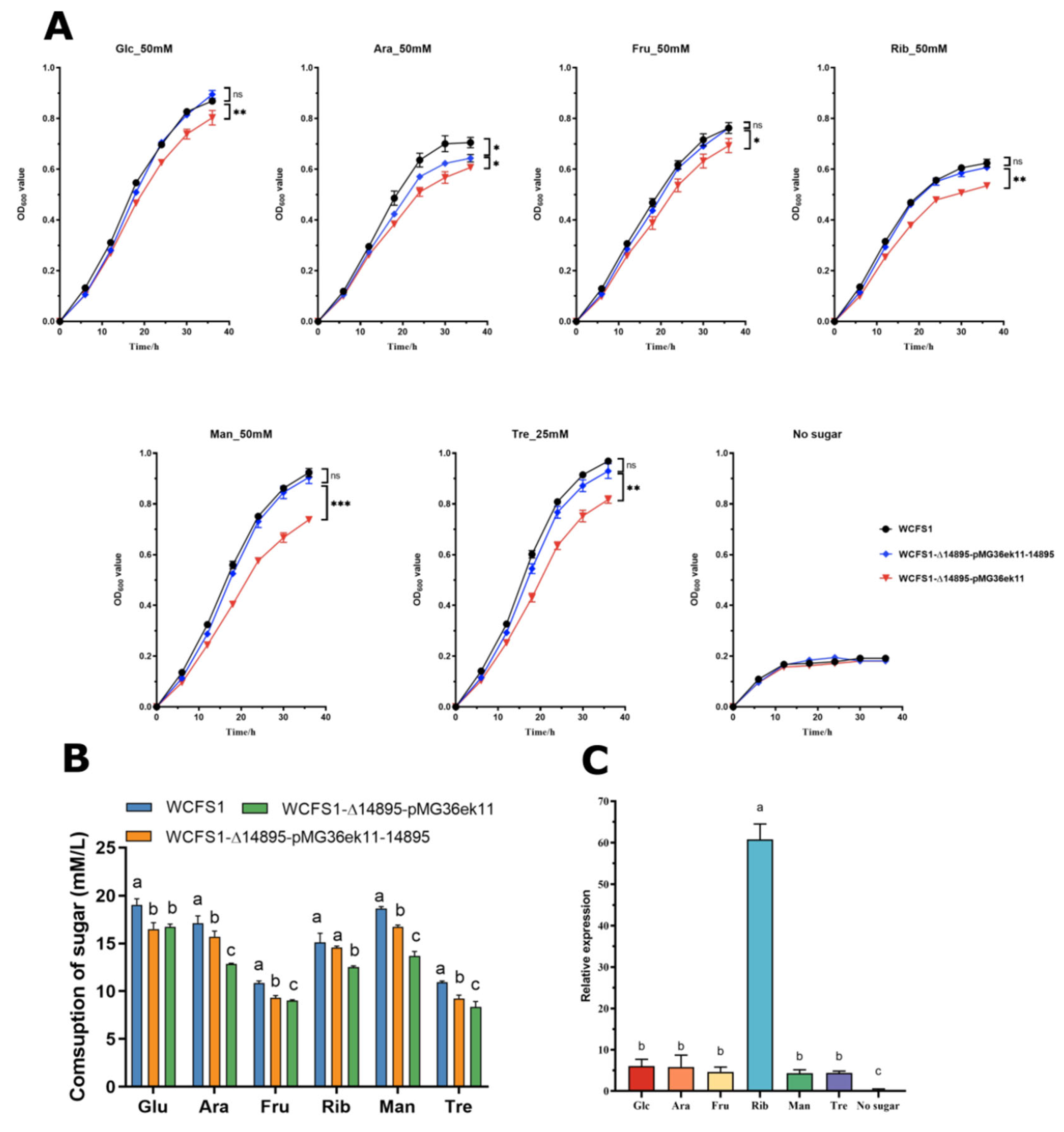

3.2. AraR: A Central Regulatory Hub for Carbohydrate Metabolic Reprogramming Under Acid Stress

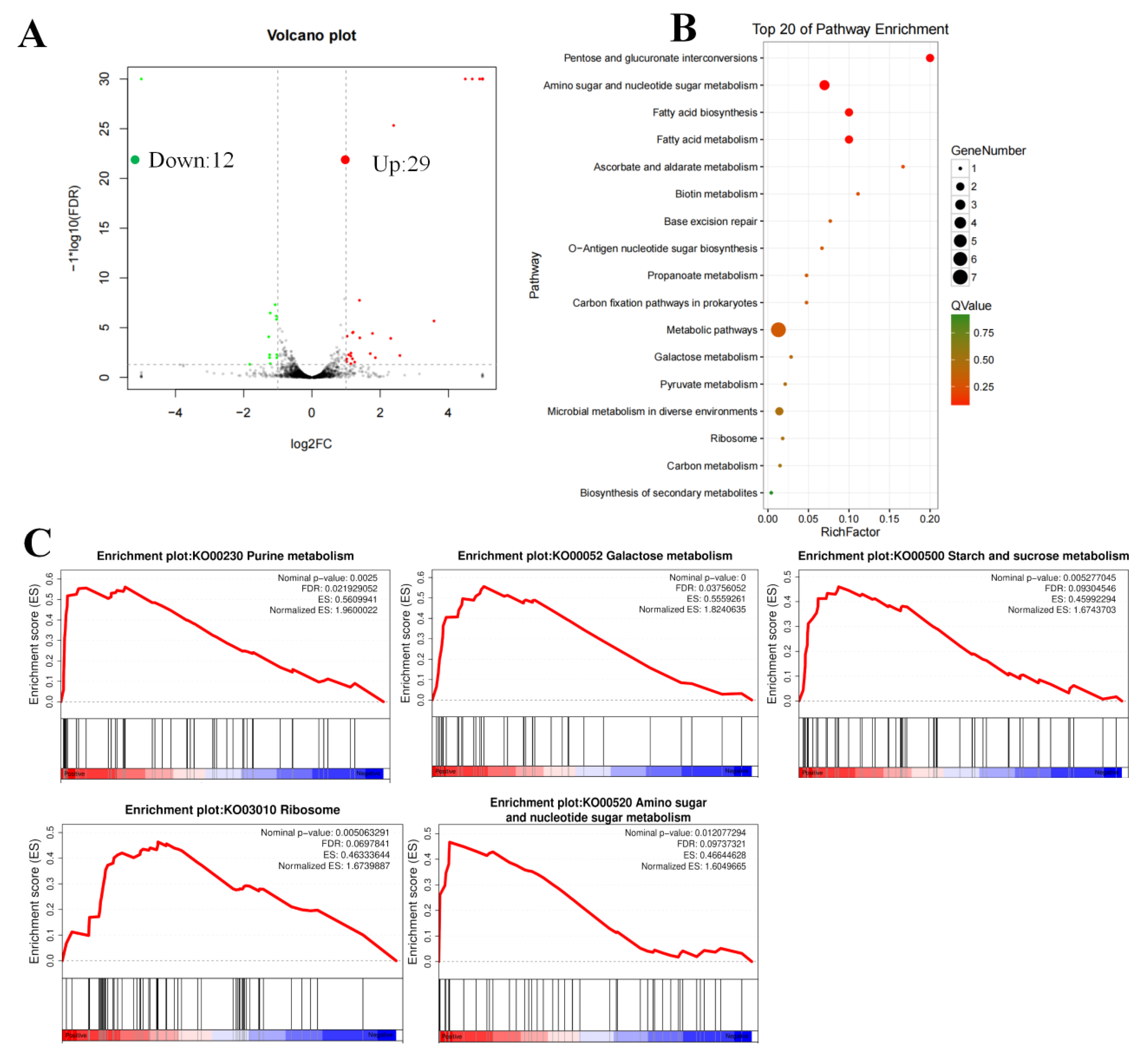

3.3. RNA-Seq Analysis Revealed That the AraR Regulates Various Carbohydrate Pathways

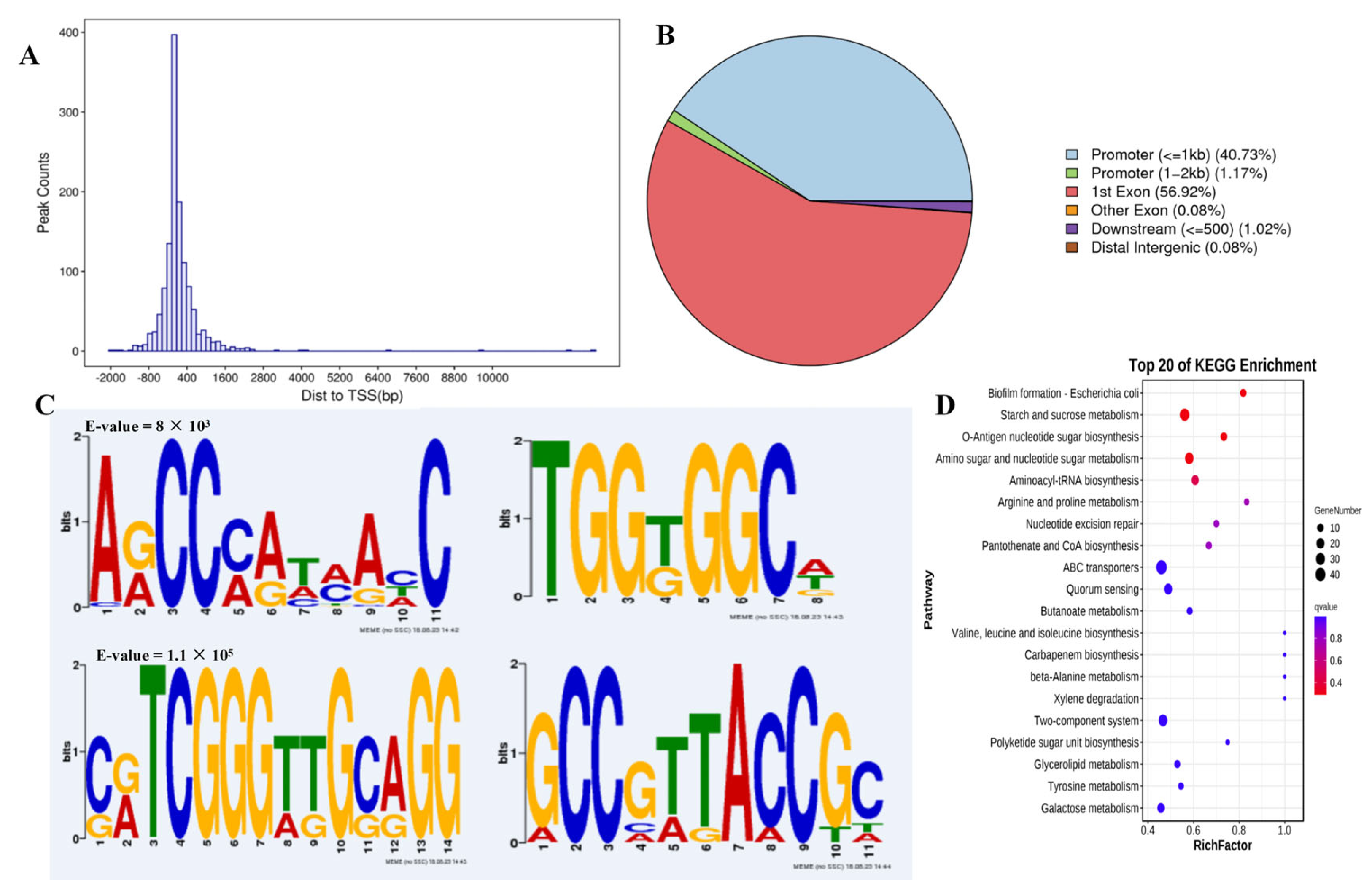

3.4. DAP-Seq Provides a Global Overview of Potential TF Binding Sites Genome-Wide

3.5. Integrated Multiomics Identification of LP_RS14895 Potential Targets Under Acid Stress

4. Discussion

4.1. AraR Enhances Microbial Adaptation in Acidic Environments: Transitioning from Arabinose Regulator to pH Modulator

4.2. AraR Governs Acid-Driven Sugar Utilization in L. plantarum

4.3. AraR: A Promising Target for Engineering Microbial Carbohydrate Biocatalysts

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Devi, A.; Anu-Appaiah, K.A.; Lin, T.F. Timing of inoculation of Oenococcus oeni and Lactobacillus plantarum in mixed malo-lactic culture along with compatible native yeast influences the polyphenolic, volatile and sensory profile of the Shiraz wines. Lwt-Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 158, 113130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nath, S.; Sikidar, J.; Roy, M.; Deb, B. Screening of probiotic properties of isolated from fermented milk product. Food Qual. Saf. 2020, 4, 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.F.; Li, P.H.; Xin, J.L.; Huang, H.C.; Yang, Y.X.; Deng, H.C.; Zhou, Z.Y.; Zhong, Z.J.; Peng, G.N.; Chen, D.C.; et al. Probiotic characteristics and whole genome analysis of PM8 from giant panda (Ailuropoda melanoleuca) milk. Probiotics Antimicro. 2025, 17, 5148–5166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echegaray, N.; Yilmaz, B.; Sharma, H.; Kumar, M.; Pateiro, M.; Ozogul, F.; Lorenzo, J.M. A novel approach to From probiotic properties to the omics insights. Microbiolo. Res. 2023, 268, 127289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, C.; Zhao, W.; Peng, C.; Hu, S.; Fang, H.; Hua, Y.; Yao, S.; Huang, J.; Mei, L. Exploring the contributions of two glutamate decarboxylase isozymes in Lactobacillus brevis to acid resistance and gamma-aminobutyric acid production. Microb. Cell Fact. 2018, 17, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mallick, S.; Das, S. Acid-tolerant bacteria and prospects in industrial and environmental applications. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2023, 107, 3355–3374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, W.; Li, C.; He, Z.; Pan, F.; Pan, S.; Wang, Y. Probiotic properties and cellular antioxidant activity of Lactobacillus plantarum MA2 isolated from Tibetan kefir grains. Probiotics Antimicro. 2018, 10, 523–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thalmann, M.; Santelia, D. Starch as a determinant of plant fitness under abiotic stress. New Phytol. 2017, 214, 943–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeandet, P.; Formela-Luboinska, M.; Labudda, M.; Morkunas, I. The role of sugars in plant responses to stress and their regulatory function during fevelopment. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 5161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La, V.H.; Lee, B.R.; Islam, M.T.; Park, S.H.; Lee, H.; Bae, D.W.; Kim, T.H. Antagonistic shifting from abscisic acid- to salicylic acid-mediated sucrose accumulation contributes to drought tolerance in. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2019, 162, 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, S.F.; Yang, Z.F.; Zheng, Y.H. Sugar metabolism in relation to chilling tolerance of loquat fruit. Food Chem. 2013, 136, 139–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.Y.; Li, J.J.; Wang, L.J.; Li, X.Y.; Liu, Y.Q.; Wang, X.; Gao, T.T.; Ma, Y.P. Integrated transcriptomic and metabolomics analysis reveals abscisic acid signal transduction and sugar metabolism pathways as defense responses to cold stress in Argyranthemum frutescens. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2023, 205, 105115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.Y.; Xu, T.Y.; Chen, H.; Tang, M. Sugar metabolism and 14-3-3 protein genes expression induced by arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and phosphorus addition to response drought stress in. J. Plant Physiol. 2023, 288, 154075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, S.; Bitoun, J.; Nguyen, A.H.; Bozner, D.; Yao, X.; Wen, Z.T. Deficiency of PdxR in Streptococcus mutans affects vitamin B-6 metabolism, acid tolerance response and biofilm formation. Mol. Oral Microbiol. 2015, 30, 255–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Q.L.; Hao, N.; Zhao, L.L.; Yang, X.K.; Yuan, Y.X.; Zhao, Y.Z.; Wang, F.; Qiu, Z.B.; He, L.; Shi, K.; et al. Comparative functional analysis of malate metabolism genes in and at low pH and their roles in acid stress response. Food Res. Int. 2022, 157, 111235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cibrario, A.; Peanne, C.; Lailheugue, M.; Campbell-Sills, H.; Dols-Lafargue, M. Carbohydrate metabolism in Oenococcus oein: A genomic insight. Bmc Genomics 2016, 17, 984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Song, X.; Yang, S. Development of a RecE/T-Assisted CRISPR-Cas9 Toolbox for. Biotechnol. J. 2019, 14, 1800690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Zhao, L.; Chen, Q.; Wang, N.; Shi, K.; Liu, S. Functional verification of the citrate transporter gene in a wine lactic acid bacterium, Lactiplantibacillus plantarum. Front Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 10, 894870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Q.; Yuan, Y.X.; Li, Y.Y.; Wu, S.W.; Shi, K.; Liu, S.W. Optimization of electro transformation parameters and engineered promoters for from Wine. Acs Synth Biol. 2021, 10, 1728–1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.Q.; Yu, H.I.; Feng, X.; Tang, H.Y.; Xiong, Z.Q.; Xia, Y.J.; Ai, L.Z.; Song, X. Specific bile salt hydrolase genes in Lactobacillus plantarum AR113 and relationship with bile salt resistance. Lwt-Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 145, 111208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossouw, D.; Du Toit, M.; Bauer, F.F. The impact of co-inoculation with Oenococcus oeni on the trancriptome of Saccharomyces cerevisiae and on the flavour-active metabolite profiles during fermentation in synthetic must. Food Microbiol. 2012, 29, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.J.; Li, T.; Chen, Q.; Yao, S.X.; Zeng, K.F. Transcriptional regulatory mechanism of a variant transcription factor CsWRKY23 in citrus fruit resistance to. Food Chem. 2023, 413, 135573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trapnell, C.; Williams, B.A.; Pertea, G.; Mortazavi, A.; Kwan, G.; van Baren, M.J.; Salzberg, S.L.; Wold, B.J.; Pachter, L. Transcript assembly and quantification by RNA-Seq reveals unannotated transcripts and isoform switching during cell differentiation. Nat. Biotechnol. 2010, 28, 511–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Love, M.I.; Huber, W.; Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014, 15, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.Y.; Liu, T.R.; Wang, B.; Li, H.B. Genome-wide characterization and expression analysis of GATA transcription factors in response to methyl jasmonate in. Genes 2022, 13, 822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nam, H.J.; Han, S.K.; Bowie, J.U.; Kim, S. Rampant exchange of the structure and function of extramembrane domains between membrane and water soluble proteins. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2013, 9, e1002997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Procházková, K.; Cermáková, K.; Pachl, P.; Sieglová, I.; Fábry, M.; Otwinowski, Z.; Rezácová, P. Structure of the effector-binding domain of the arabinose repressor AraR from Bacillus subtilis. Acta Crystallogr. D. 2012, 68, 176–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuge, T.; Teramoto, H.; Inui, M. AraR, an L-arabinose-responsive transcriptional regulator in ATCC 31831, exerts different degrees of repression depending on the location of its binding sites within the three target promoter regions. J. Bacteriol. 2015, 197, 3788–3796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mota, L.J.; Tavares, P.; Sa-Nogueira, I. Mode of action of AraR, the key regulator of L-arabinose metabolism in Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Microbiol. 1999, 33, 476–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartlett, A.; O'Malley, R.C.; Huang, S.S.C.; Galli, M.; Nery, J.R.; Gallavotti, A.; Ecker, J.R. Mapping genome-wide transcription-factor binding sites using DAP-seq. Nat. Protoc. 2017, 12, 1659–1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machanick, P.; Bailey, T.L. MEME-ChIP: Motif analysis of large DNA datasets. Bioinformatics 2011, 27, 1696–1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Zhang, Y.L.; Li, L.; Li, Y.N.; Yuan, L.; Yue, E.; Qiao, J.J. Positive regulation of the operon by TCSR7 enhances acid tolerance of F44. J. Dairy Sci. 2022, 105, 7940–7950. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, C.; Wei, X.W.; Sun, C.H.; Zhang, F.; Xu, J.R.; Zhao, X.Q.; Bai, F.W. Improvement of acetic acid tolerance of using a zinc-finger-based artificial transcription factor and identification of novel genes involved in acetic acid tolerance. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2015, 99, 2441–2449. [Google Scholar]

- Yamada, R.; Kumata, Y.; Mitsui, R.; Matsumoto, T.; Ogino, H. Improvement of lactic acid tolerance by cocktail δ-integration strategy and identification of the transcription factor PDR3 responsible for lactic acid tolerance in yeast. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2021, 37, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.Q.; Song, S.C.; Tian, H.X.; Yu, H.Y.; Zhao, J.X.; Chen, C. Functional analysis of the role of CcpA in Lactobacillus plantarum grown on fructooligosaccharides or glucose: A transcriptomic perspective. Microb. Cell Fact. 2018, 17, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, S.; Ma, J.Z.; Lu, Z. Enhances oxidative stress tolerance through rhamnose-dependent mechanisms. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1505218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyer, B.; Rajput, M.S.; Jog, R.; Joshi, E.; Bharwad, K.; Rajkumar, S. Organic acid mediated repression of sugar utilization in rhizobia. Microbiol. Res. 2016, 192, 211–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, W.P.; Shang, Y.Z.; Zhang, P.; Liu, Y.; You, D.; Yin, B.C.; Ye, B.C. Engineering prokaryotic transcriptional activator XylR as a xylose-inducible biosensor for transcription activation in Yeast. Acs Synth. Biol. 2020, 9, 1022–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, R.; Flores, A.D.; Dufault, M.E.; Wang, X. The XylR variant (R121C and P363S) releases arabinose-induced catabolite repression on xylose fermentation and enhances coutilization of lignocellulosic sugar mixtures. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2019, 116, 3476–3481. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lin, Z.L.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J.Q. Engineering of transcriptional regulators enhances microbial stress tolerance. Biotechnol. Adv. 2013, 31, 986–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.W.; Zhang, X.Y.; Wu, H.; Bai, Y.P. Transcription factor engineering for high-throughput strain evolution and organic acid bioproduction: A review. Front. Bioeng. Biotech. 2020, 8, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahr, R.; Frunzke, J. Transcription factor-based biosensors in biotechnology: Current state and future prospects. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2016, 100, 79–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhao, L.; Chen, M.; Fu, C.; Pan, T.; Chen, Q. AraR Transcription Factor Affects the Sugar Metabolism and Acid Tolerance of Lactiplantibacillus plantarum. Foods 2025, 14, 4123. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234123

Zhao L, Chen M, Fu C, Pan T, Chen Q. AraR Transcription Factor Affects the Sugar Metabolism and Acid Tolerance of Lactiplantibacillus plantarum. Foods. 2025; 14(23):4123. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234123

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhao, Lili, Mengrong Chen, Chunjing Fu, Tao Pan, and Qiling Chen. 2025. "AraR Transcription Factor Affects the Sugar Metabolism and Acid Tolerance of Lactiplantibacillus plantarum" Foods 14, no. 23: 4123. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234123

APA StyleZhao, L., Chen, M., Fu, C., Pan, T., & Chen, Q. (2025). AraR Transcription Factor Affects the Sugar Metabolism and Acid Tolerance of Lactiplantibacillus plantarum. Foods, 14(23), 4123. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234123