Quantitative Detection of Key Parameters and Authenticity Verification for Beer Using Near-Infrared Spectroscopy

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Beer Sample Preparation

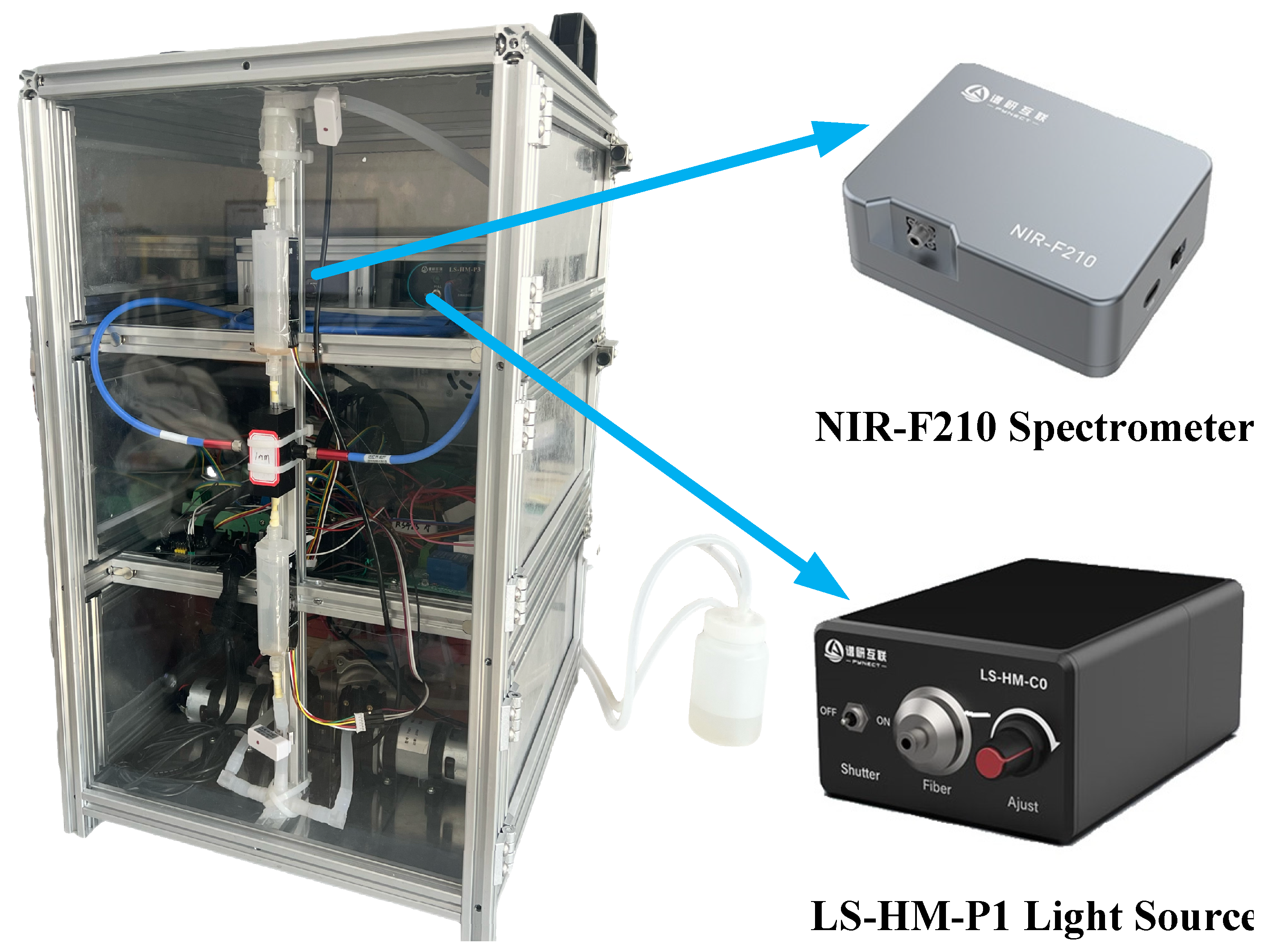

2.2. Spectral Data Acquisition

2.3. Feature Extraction Methods

2.3.1. CARS

2.3.2. SPA

2.3.3. CNN

2.3.4. LSTM

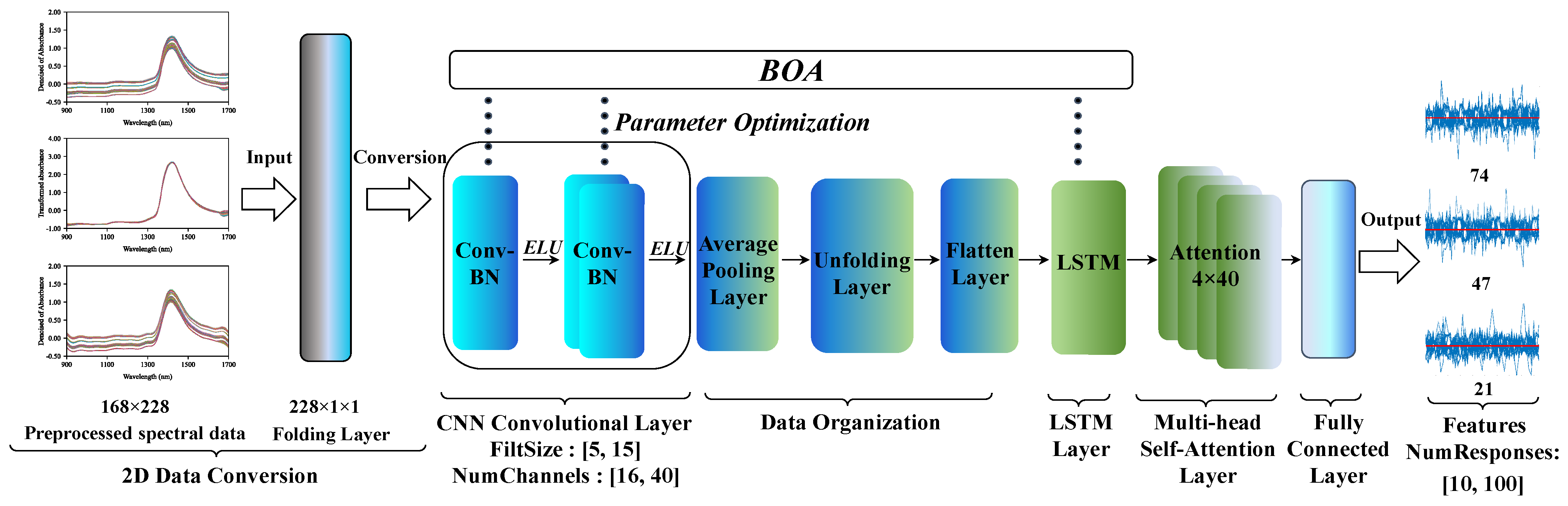

2.3.5. CNN-LSTM

2.4. Modeling Methods and Evaluation Metrics

3. Results and Discussion

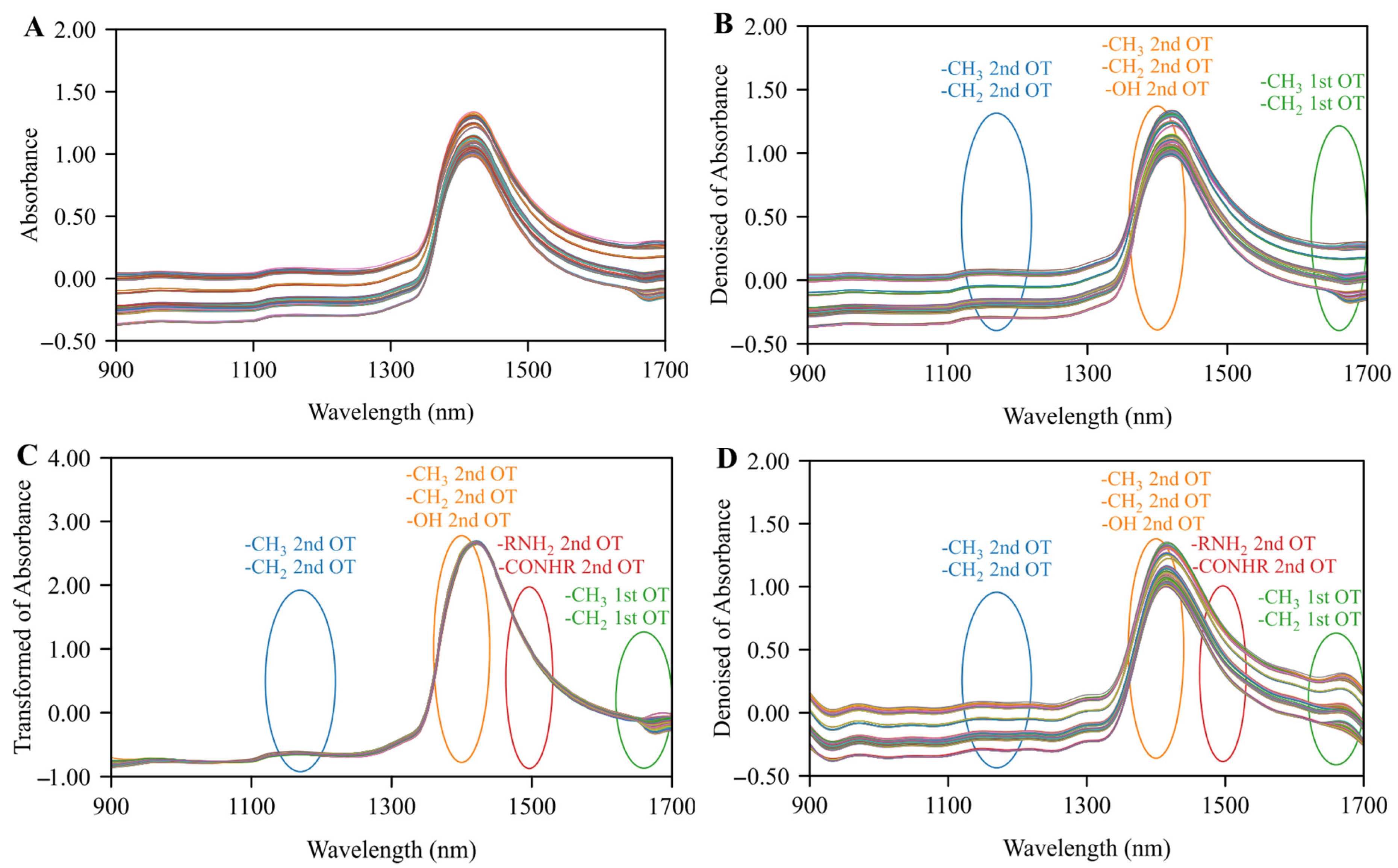

3.1. Data Analysis

3.2. Spectral Feature Extraction

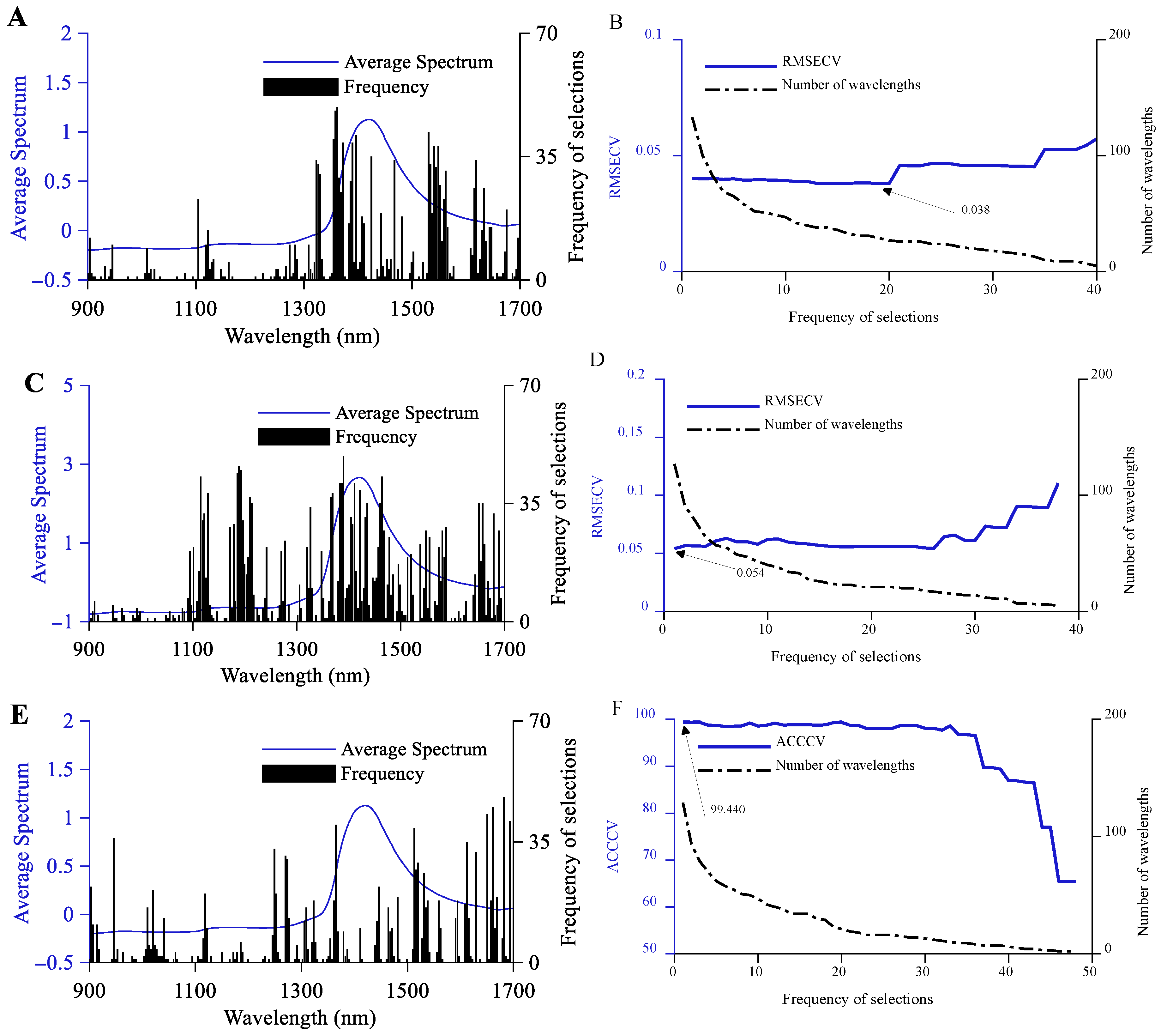

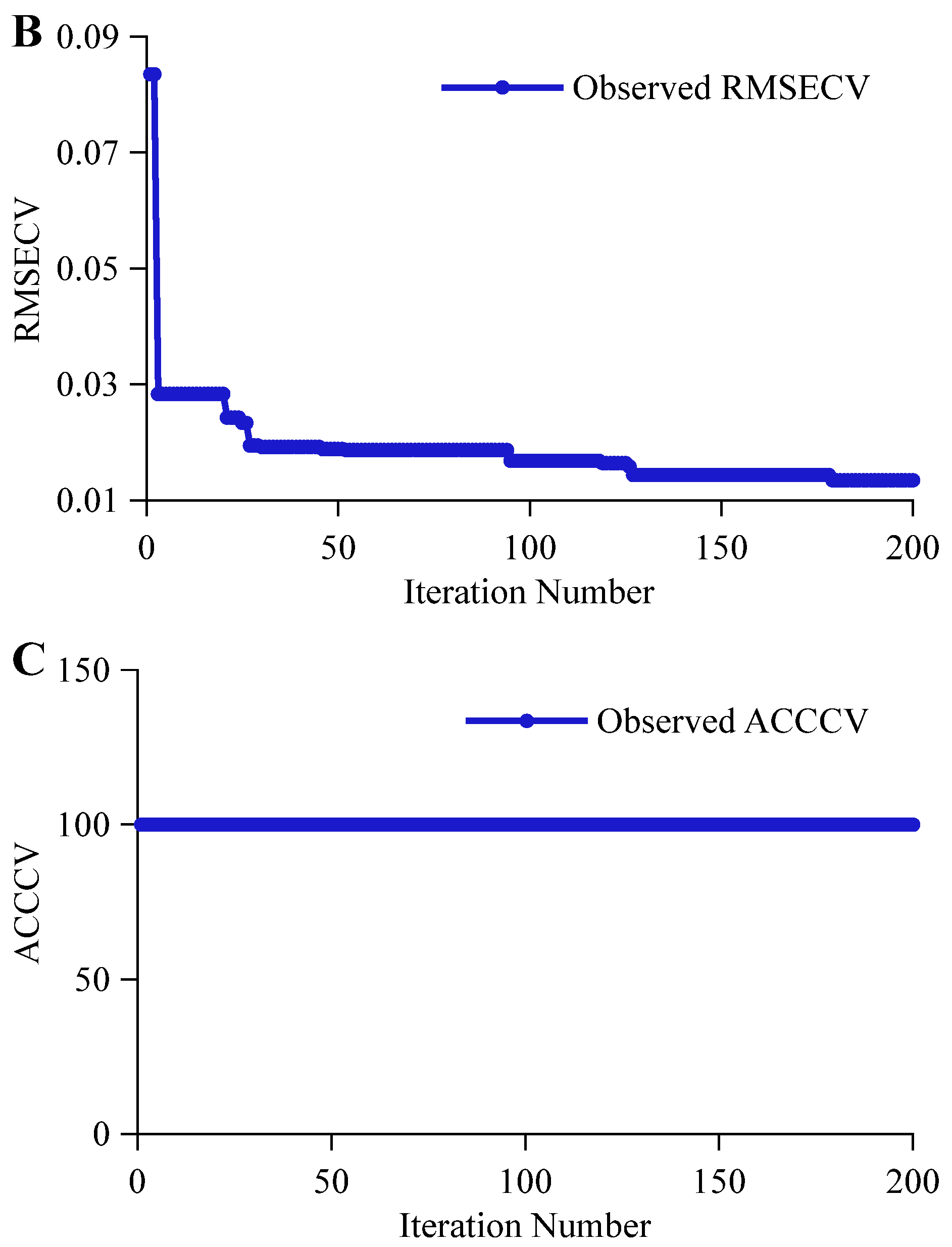

3.2.1. CARS Feature Variable Selection

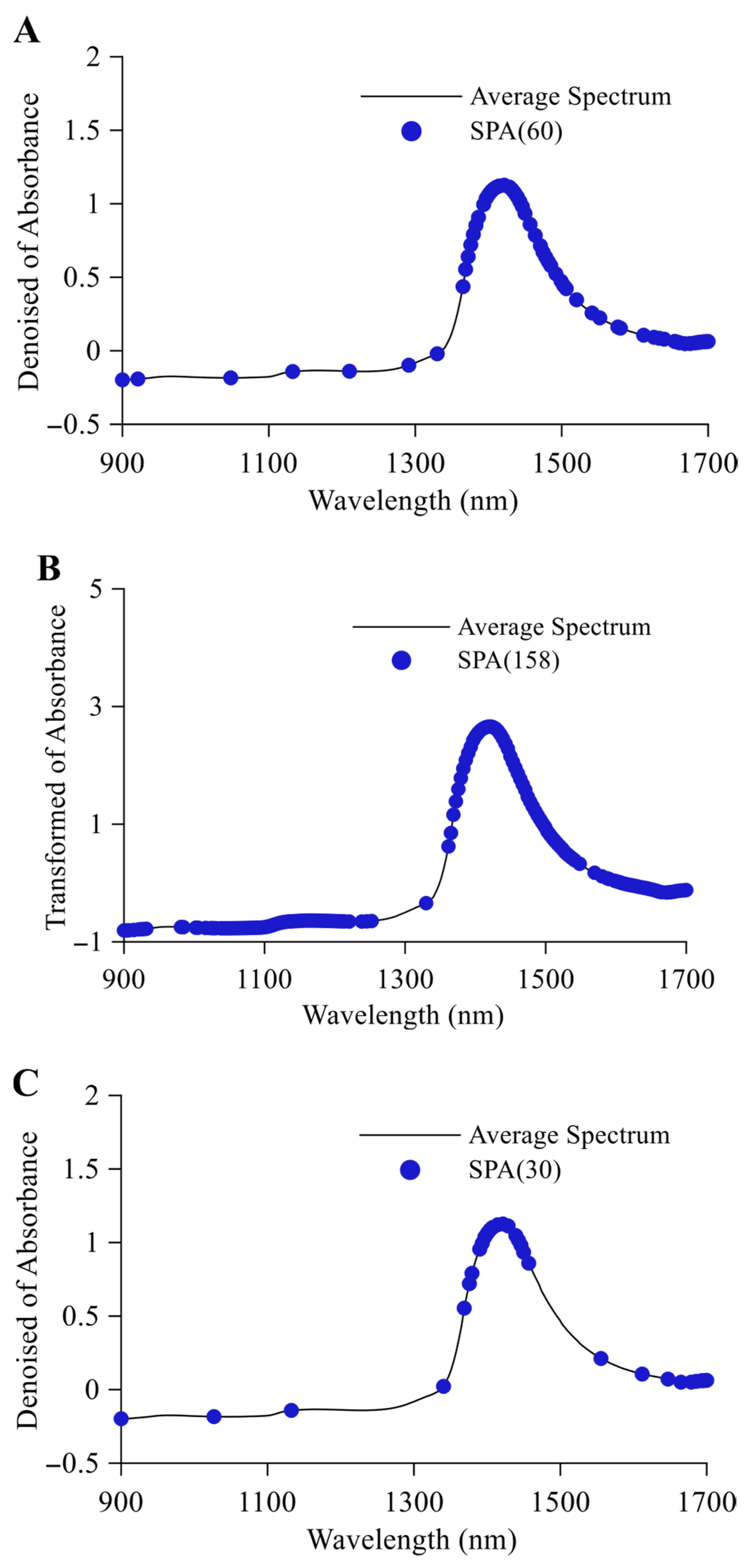

3.2.2. SPA Feature Variable Selection

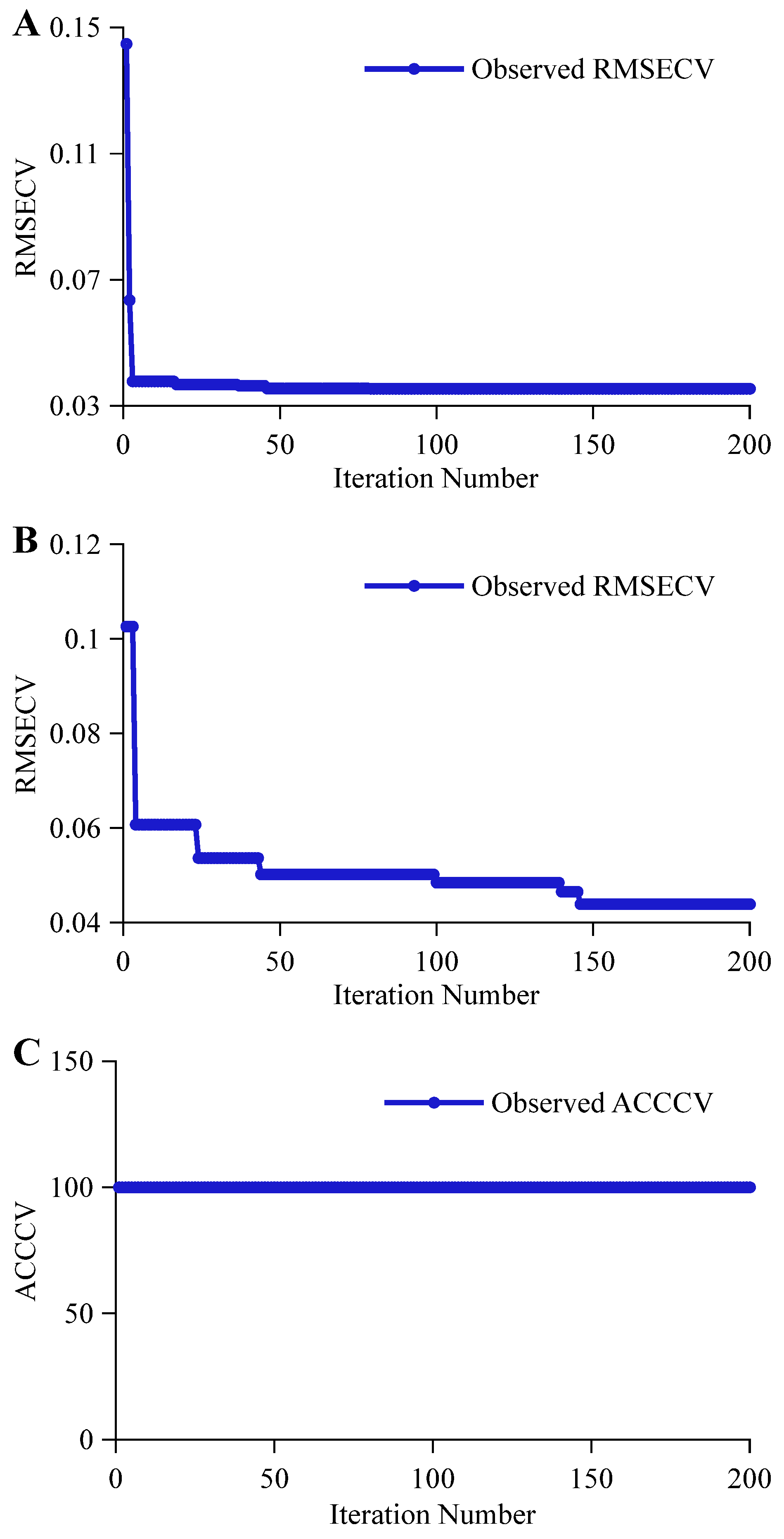

3.2.3. CNN Spectral Feature Extraction

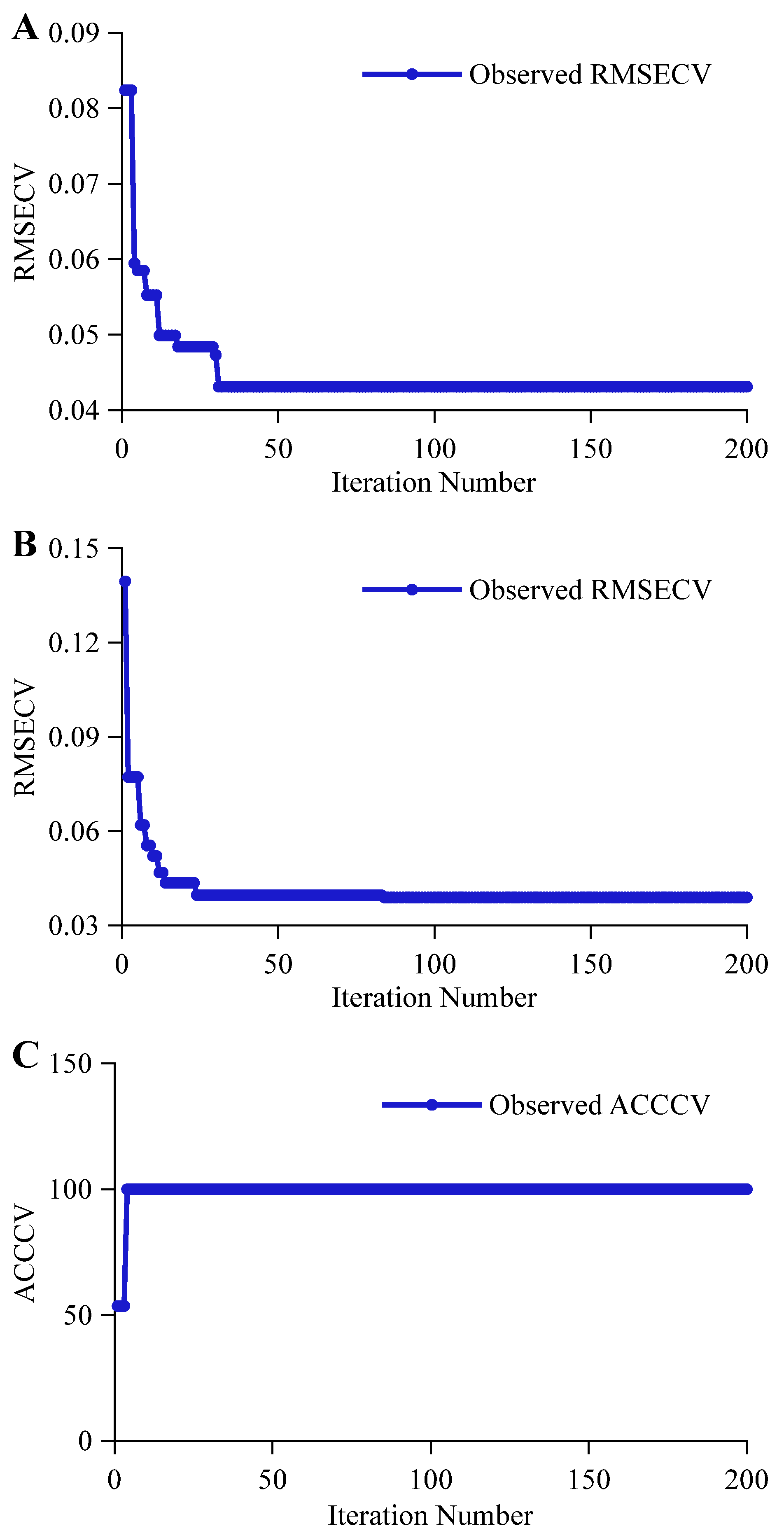

3.2.4. LSTM Spectral Feature Extraction

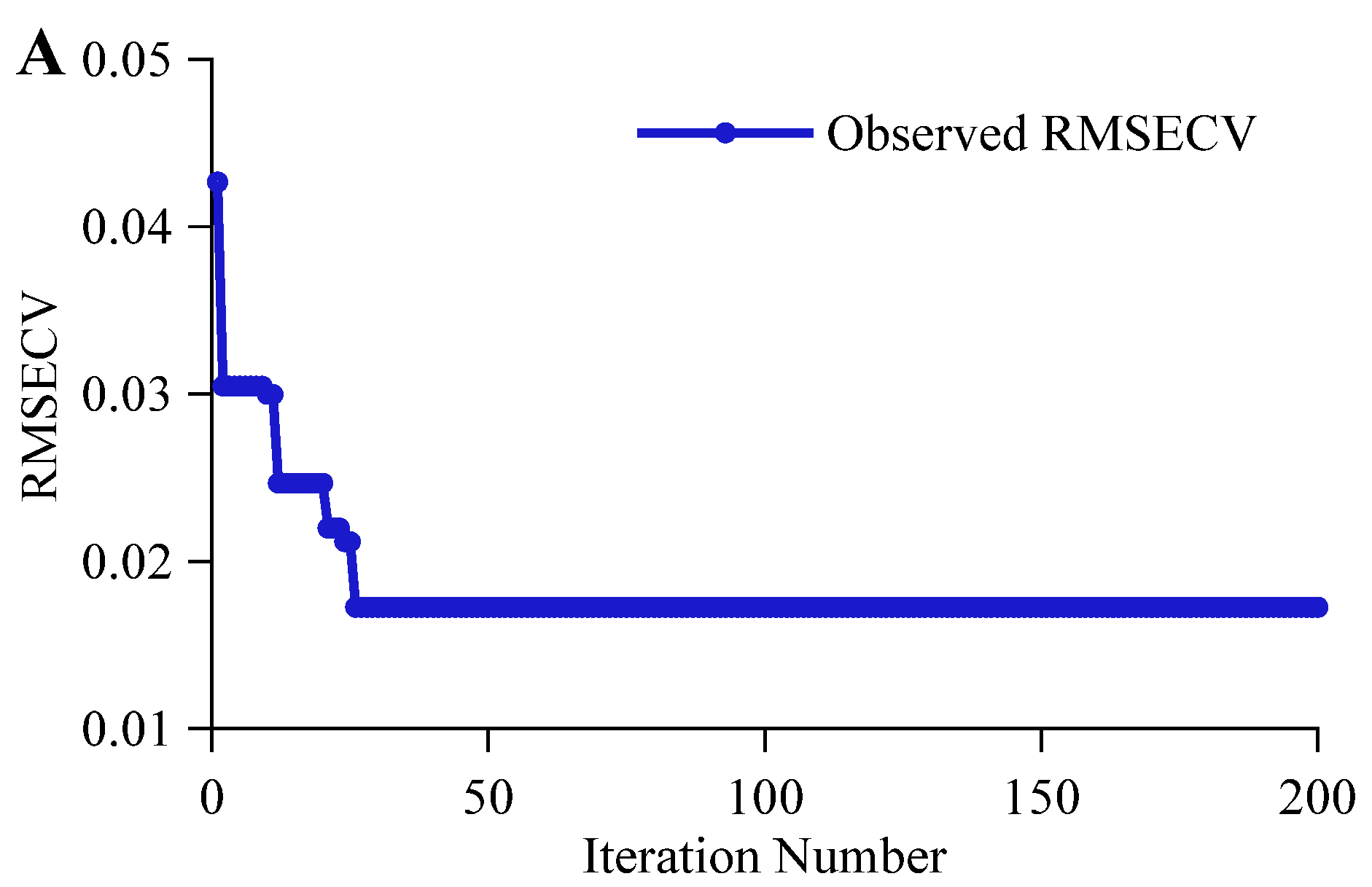

3.2.5. CNN-LSTM Spectral Feature Extraction

3.3. Model Construction and Evaluation

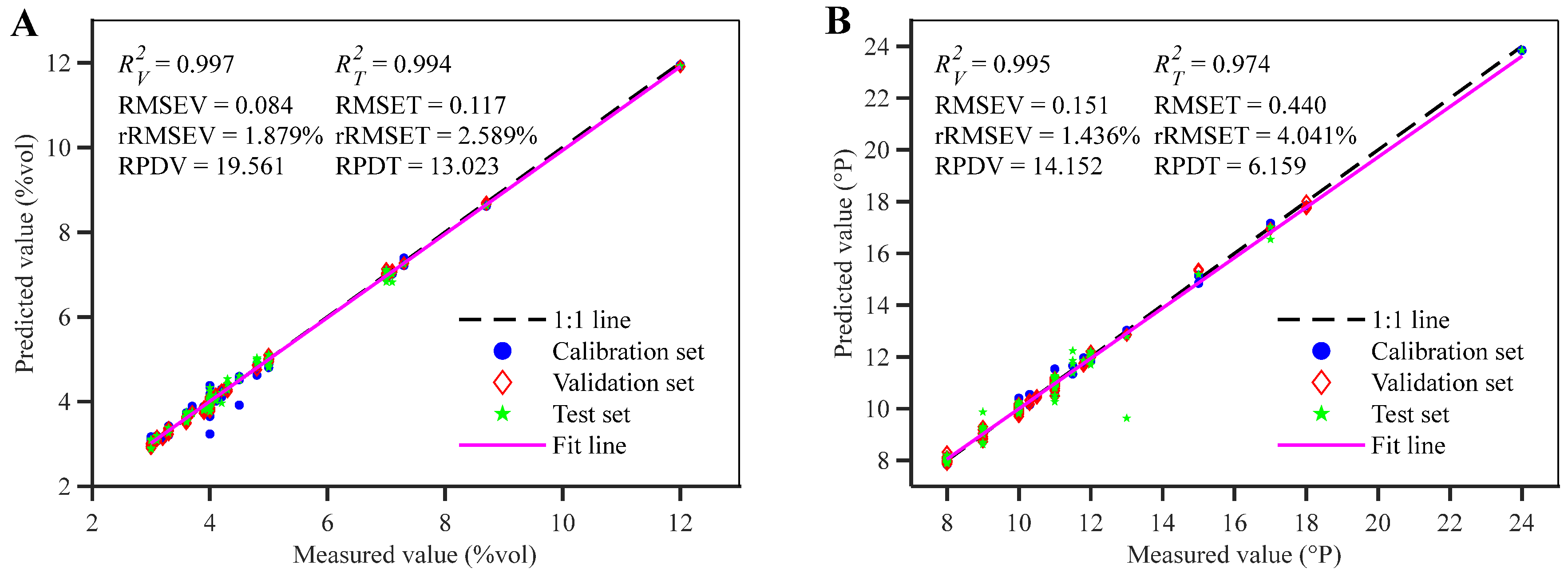

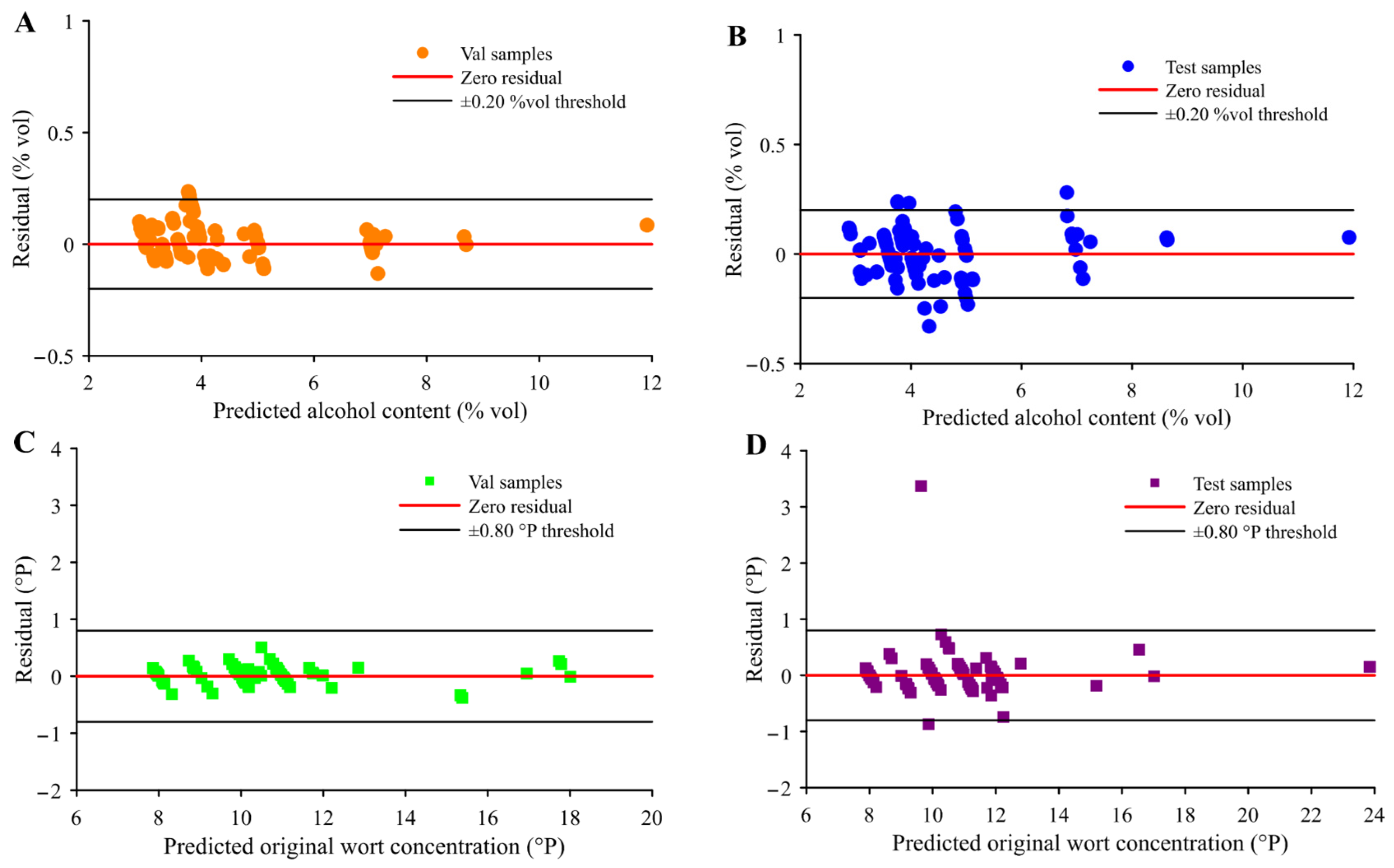

3.3.1. Quantitative Forecast Results and Analysis

3.3.2. Classification Results and Analysis

3.4. Advantages and Limitations

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Raihofer, L.; Zarnow, M.; Gastl, M.; Hutzler, M. A short history of beer brewing. EMBO Rep. 2022, 23, e56355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iorizzo, M.; Coppola, F.; Letizia, F.; Testa, B.; Sorrentino, E. Role of Yeasts in the Brewing Process: Tradition and Innovation. Processes 2021, 9, 839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Postigo, V.; Mauro, L.; Diaz, T.; Saiz, R.; Arroyo, T.; García, M. Autochthonous Ingredients for Craft Beer Production. Fermentation 2024, 10, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villacreces, S.; Blanco, C.A.; Caballero, I. Developments and characteristics of craft beer production processes. Food Biosci. 2022, 45, 101495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciont, C.; Epuran, A.; Kerezsi, A.D.; Coldea, T.E.; Mudura, E.; Pasqualone, A.; Zhao, H.; Suharoschi, R.; Vriesekoop, F.; Pop, O.L. Beer Safety: New Challenges and Future Trends within Craft and Large-Scale Production. Foods 2022, 11, 2693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosales, A.; Talaverano, M.I.; Lozano, J.; Sánchez-Vicente, C.; Santamaría, Ó.; García-Latorre, C.; Rodrigo, S. Craft beer vs. industrial beer: Chemical and sensory differences. Br. Food J. 2021, 123, 4332–4346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umemura, M.; Slater, S. Institutional explanations for local diversification: A historical analysis of the Japanese beer industry, 1952–2017. J. Strateg. Mark. 2021, 29, 71–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Li, Y.; Shao, F.; Lu, Y.; Meng, W.; Rogers, K.M.; Sun, D.; Wu, H.; Peng, X. Advancing Stable Isotope Analysis for Alcoholic Beverages’ Authenticity: Novel Approaches in Fraud Detection and Traceability. Foods 2025, 14, 943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edgar Herkenhoff, M.; Brödel, O.; Frohme, M. Aroma component analysis by HS-SPME/GC–MS to characterize Lager, Ale, and sour beer styles. Food Res. Int. 2024, 194, 114763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Costa Fulgêncio, A.C.; Resende, G.A.P.; Teixeira, M.C.F.; Botelho, B.G.; Sena, M.M. Determination of Alcohol Content in Beers of Different Styles Based on Portable Near-Infrared Spectroscopy and Multivariate Calibration. Food Anal. Methods 2022, 15, 307–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Dai, H.; Zhang, J.; Zheng, Z.; Song, B.; Chen, J.; Lin, G.; Chen, L.; Sun, W.; Huang, Y. A Study on Origin Traceability of White Tea (White Peony) Based on Near-Infrared Spectroscopy and Machine Learning Algorithms. Foods 2023, 12, 499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, J.; Yu, H.-D.; Chen, Z.; Yun, Y.-H. A review on hybrid strategy-based wavelength selection methods in analysis of near-infrared spectral data. Infrared Phys. Technol. 2022, 125, 104231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Zeng, S.; Fu, H.; Wu, B.; Zhou, H.; Dai, C. Determination of corn protein content using near-infrared spectroscopy combined with A-CARS-PLS. Food Chem. X 2023, 18, 100666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Yu, H.; Jiang, D.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, K. A novel NIRS modelling method with OPLS-SPA and MIX-PLS for timber evaluation. J. For. Res. 2022, 33, 369–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, J.; Zhang, J.; Xiong, Y.; Min, S. Feature selection of infrared spectra analysis with convolutional neural network. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2022, 266, 120361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Dong, Y.; Liu, J.; Wu, S. Combined use of near infrared spectroscopy and chemometrics for the simultaneous detection of multiple illicit additions in wheat flour. Appl. Food Res. 2025, 5, 101263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Dong, Y.; Liu, J.; Wang, C.; Bao, C.; Wang, N.; Zhao, X.; Chen, Z. Identification and quantitative detection of illegal additives in wheat flour based on near-infrared spectroscopy combined with chemometrics. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2024, 323, 124938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Chen, H.; Meng, F.; Lin, B.; Xu, L. Reusable CNN-LSTM block for improving near-infrared spectroscopic analysis of berberine content. Microchem. J. 2025, 217, 114911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, G.; Zhao, J.; Qu, H. A novel CNN-LSTM model with attention mechanism for online monitoring of moisture content in fluidized bed granulation process based on near-infrared spectroscopy. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2025, 340, 126361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wu, Q.; Kamruzzaman, M. Portable NIR spectroscopy and PLS based variable selection for adulteration detection in quinoa flour. Food Control 2022, 138, 108970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spoladore, S.F.; Brígida dos Santos Scholz, M.; Bona, E. Genotypic classification of wheat using near-infrared spectroscopy and PLS-DA. Appl. Food Res. 2021, 1, 100019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasconcelos, L.; Dias, L.G.; Leite, A.; Ferreira, I.; Pereira, E.; Silva, S.; Rodrigues, S.; Teixeira, A. SVM Regression to Assess Meat Characteristics of Bísaro Pig Loins Using NIRS Methodology. Foods 2023, 12, 470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.; Tan, C.; Lin, Z.; Wu, T. Classification of different liquid milk by near-infrared spectroscopy and ensemble modeling. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2021, 251, 119460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Liang, Y.; Xu, Q.; Cao, D. Key wavelengths screening using competitive adaptive reweighted sampling method for multivariate calibration. Anal. Chim. Acta 2009, 648, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, M.C.U.; Saldanha, T.C.B.; Galvão, R.K.H.; Yoneyama, T.; Chame, H.C.; Visani, V. The successive projections algorithm for variable selection in spectroscopic multicomponent analysis. Chemom. Intell. Lab. Syst. 2001, 57, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, Q.; Fan, Z.; Chang, H.; Shoaib, M.; Chen, Q. Analyzing TVB-N in snakehead by Bayesian-optimized 1D-CNN using molecular vibrational spectroscopic techniques: Near-infrared and Raman spectroscopy. Food Chem. 2025, 464, 141701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, L.; Zhang, Z.-T.; Guan, H.; Liu, W.; Chen, L.; Yuan, D.; Chen, P.; Xue, M.; Yan, G. Rapid and accurate quality evaluation of Angelicae Sinensis Radix based on near-infrared spectroscopy and Bayesian optimized LSTM network. Talanta 2024, 275, 126098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Z.; Gu, J.; Zhu, R.; Yao, X.; Kang, L.; Ge, J. Discrimination of Minced Mutton Adulteration Based on Sized-Adaptive Online NIRS Information and 2D Conventional Neural Network. Foods 2022, 11, 2977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, L.; Liu, W.; Lei, M.; Yu, X. An Improved Residual Network for Pork Freshness Detection Using Near-Infrared Spectroscopy. Entropy 2021, 23, 1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Liu, J.; Li, P.; Tan, C. Rapid detection of volatile fatty acids in biogas slurry using near-infrared spectroscopy combined with optimized wavelength selection and partial least squares regression. Results Chem. 2025, 16, 102462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Pu, Y.; Wei, Z.; Liu, H.; Zhang, D.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, Z.; Zhao, J.; Hu, J. Combination of interactance and transmittance modes of Vis/NIR spectroscopy improved the performance of PLS-DA model for moldy apple core. Infrared Phys. Technol. 2022, 126, 104366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, J.K.; Moura-Bueno, J.M.; Ramon, R.; Almeida, T.F.; Naibo, G.; Martins, A.P.; Santos, L.S.; Gianello, C.; Tiecher, T. Combining different pre-processing and multivariate methods for prediction of soil organic matter by near infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) in Southern Brazil. Geoderma Reg. 2022, 29, e00530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Li, L.; Zheng, J.; Wu, J.; Wen, L.; Huang, M.; Ao, F.; Luo, W.; Li, M.; Wang, H.; et al. Quantitative analysis of key components in Qingke beer brewing process by multispectral analysis combined with chemometrics. Food Chem. 2024, 436, 137739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Song, J.; He, H.; Yu, Y.; Wang, R.; Huang, Y.; Li, Z. Quantitative Analysis of High-Price Rice Adulteration Based on Near-Infrared Spectroscopy Combined with Chemometrics. Foods 2024, 13, 3241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Luo, X.; Zhang, D.; Wang, C.; Chen, Z.; Zhao, X. Rapid determination of rice protein content using near-infrared spectroscopy coupled with feature wavelength selection. Infrared Phys. Technol. 2023, 135, 104969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Liu, J.; Sun, Y.; Chen, S.; Miao, X. Fast detection of volatile fatty acids in biogas slurry using NIR spectroscopy combined with feature wavelength selection. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 857, 159282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fulgêncio, A.C.d.C.; Resende, G.A.P.; Teixeira, M.C.F.; Botelho, B.G.; Sena, M.M. Combining portable NIR spectroscopy and multivariate calibration for the determination of ethanol in fermented alcoholic beverages by a multi-product model. Talanta Open 2023, 7, 100180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, M.-W.; Guo, Q.; Yang, H.-L.; Wang, H.-L.; Sun, X.-L. Estimation of soil organic matter by in situ Vis-NIR spectroscopy using an automatically optimized hybrid model of convolutional neural network and long short-term memory network. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2023, 214, 108350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buzpinar, M.A.; Gunaydin, S.; Kavuncuoglu, E.; Cetin, N.; Sacilik, K.; Cheein, F.A. Model comparison and hyperparameter optimization for visible and near-infrared (Vis-NIR) spectral classification of dehydrated banana slices. Expert Syst. Appl. 2025, 283, 127858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Luan, X.; Liu, F. Near-infrared quality monitoring modeling with multi-scale CNN and temperature adaptive correction. Infrared Phys. Technol. 2024, 137, 105162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehin, M.M.; Rafe, M.R.I.; Amin, A.; Rahman, K.S.; Rakib, M.R.I.; Ahamed, S.; Rahman, A. Prediction of sugar content in Java Plum using SW-NIR spectroscopy with CNN-LSTM based hybrid deep learning model. Meas. Food 2025, 19, 100246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razavi, M.S.; Sharabiani, V.R.; Tahmasebi, M.; Grassi, S.; Szymanek, M. Chemometric and meta-heuristic algorithms to find optimal wavelengths and predict ‘Red Delicious’ apples traits using Vis-NIR. Appl. Food Res. 2025, 5, 100853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wang, R. Determination of soil pH from Vis-NIR spectroscopy by extreme learning machine and variable selection: A case study in lime concretion black soil. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2022, 283, 121707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, T.; Shi, Y.; Cui, E.; Wang, X.; Mao, C.; Xie, H.; Lu, T. Rapid detection of multi-indicator components of classical famous formula Zhuru Decoction concentration process based on fusion CNN-LSTM hybrid model with the near-infrared spectrum. Microchem. J. 2023, 195, 109438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Liu, J.; Tauqeer, I.M.; Shao, Z. Water chemical oxygen demand prediction based on a one-dimensional multi-scale feature fusion convolutional neural network and ultraviolet-visible spectroscopy. RSC Adv. 2025, 15, 19431–19442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Indicator | Subsets | Number | Mean (%vol/°P) | Max (%vol/°P) | Min (%vol/°P) | Standard Deviation (%vol/°P) | Coefficient of Variation (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alcohol content | Calibration set | 168 | 4.497 | 12 | 3 | 1.773 | 39.426 |

| Validation set | 84 | 4.495 | 12 | 3 | 1.537 | 34.193 | |

| Test set | 84 | 4.532 | 12 | 3 | 1.624 | 35.834 | |

| Original wort | Calibration set | 168 | 10.865 | 24 | 8 | 2.705 | 24.896 |

| Validation set | 84 | 10.613 | 24 | 8 | 2.434 | 22.934 | |

| Test set | 84 | 10.879 | 24 | 8 | 2.719 | 24.993 |

| Key Indicators | Parameters | Results |

|---|---|---|

| Alcohol content | numResponses | 36 |

| InitialLearnRate | 0.0011024 | |

| L2Regularization | 2.0555 × 10−10 | |

| LearnRateDropFactor | 0.66659 | |

| Parameter count | 263,044 | |

| Original wort | numResponses | 50 |

| InitialLearnRate | 0.007966 | |

| L2Regularization | 6.6968 × 10−5 | |

| LearnRateDropFactor | 0.86817 | |

| Parameter count | 365,202 | |

| Classification and Identification | numResponses | 27 |

| InitialLearnRate | 0.0017568 | |

| L2Regularization | 0.0033696 | |

| LearnRateDropFactor | 0.4984 | |

| Parameter count | 197,371 |

| Key Indicators | Parameters | Results |

|---|---|---|

| Alcohol content | numResponses | 50 |

| InitialLearnRate | 0.0050306 | |

| L2Regularization | 4.9258 × 10−7 | |

| LearnRateDropFactor | 0.61321 | |

| Parameter count | 58,350 | |

| Original wort | numResponses | 95 |

| InitialLearnRate | 0.0051512 | |

| L2Regularization | 3.1168 × 10−9 | |

| LearnRateDropFactor | 0.89368 | |

| Parameter count | 132,240 | |

| Classification and Identification | numResponses | 26 |

| InitialLearnRate | 0.010598 | |

| L2Regularization | 9.7163 × 10−5 | |

| LearnRateDropFactor | 0.88148 | |

| Parameter count | 27,222 |

| Key Indicators | Parameter | Result |

|---|---|---|

| Alcohol content | numResponses | 74 |

| FiltSize | 7 | |

| numChannels | 37 | |

| MaxEpochs | 294 | |

| numHiddenUnits | 38 | |

| InitialLearnRate | 0.0041 | |

| LearnRateDropPeriod | 114 | |

| L2Regularization | 9.8567 × 10−6 | |

| LearnRateDropFactor | 0.8671 | |

| Parameter count | 111,933 | |

| Original wort | numResponses | 47 |

| FiltSize | 10 | |

| numChannels | 18 | |

| MaxEpochs | 100 | |

| numHiddenUnits | 32 | |

| InitialLearnRate | 0.0051 | |

| LearnRateDropPeriod | 86 | |

| L2Regularization | 1.6383 × 10−8 | |

| LearnRateDropFactor | 0.8783 | |

| Parameter count | 47,737 | |

| Classification and Identification | numResponses | 21 |

| FiltSize | 5 | |

| numChannels | 22 | |

| MaxEpochs | 125 | |

| numHiddenUnits | 32 | |

| InitialLearnRate | 0.0033777 | |

| LearnRateDropPeriod | 99 | |

| L2Regularization | 2.3756 × 10−8 | |

| LearnRateDropFactor | 0.57755 | |

| Parameter count | 84,323 |

| Model | Method | Dimension | RMSEC | RMSEV | RMSET | rRMSEC | rRMSEV | rRMSET | RPDV | RPDT | LVs | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CNN | CNN | 36 | 0.976 | 0.968 | 0.956 | 0.273 | 0.288 | 0.320 | 6.075 | 6.410 | 7.060 | 5.693 | 4.781 | N/A |

| LSTM | LSTM | 50 | 0.965 | 0.979 | 0.955 | 0.328 | 0.237 | 0.325 | 7.301 | 5.263 | 7.179 | 6.864 | 4.723 | N/A |

| PLSR | Full | 228 | 0.964 | 0.950 | 0.947 | 0.334 | 0.361 | 0.353 | 7.420 | 8.039 | 7.783 | 4.559 | 4.337 | 10 |

| CARS | 29 | 0.966 | 0.954 | 0.952 | 0.325 | 0.347 | 0.335 | 7.225 | 7.722 | 7.399 | 4.699 | 4.562 | 10 | |

| SPA | 60 | 0.967 | 0.952 | 0.950 | 0.323 | 0.353 | 0.343 | 7.176 | 7.849 | 7.571 | 4.656 | 4.455 | 10 | |

| CNN | 36 | 0.973 | 0.964 | 0.955 | 0.289 | 0.304 | 0.323 | 6.422 | 6.767 | 7.132 | 5.420 | 4.736 | 9 | |

| LSTM | 50 | 0.977 | 0.965 | 0.957 | 0.266 | 0.304 | 0.318 | 5.911 | 6.753 | 7.018 | 5.424 | 4.829 | 15 | |

| CNN-LSTM | 74 | 0.988 | 0.991 | 0.980 | 0.194 | 0.157 | 0.214 | 4.314 | 3.483 | 4.721 | 10.532 | 7.143 | 14 | |

| SVM | Full | 228 | 0.980 | 0.978 | 0.971 | 0.252 | 0.238 | 0.260 | 5.612 | 5.304 | 5.742 | 6.903 | 5.884 | N/A |

| CARS | 29 | 0.981 | 0.975 | 0.963 | 0.245 | 0.257 | 0.293 | 5.445 | 5.725 | 6.500 | 6.457 | 5.252 | N/A | |

| SPA | 60 | 0.989 | 0.986 | 0.973 | 0.185 | 0.194 | 0.250 | 4.121 | 4.305 | 5.506 | 8.745 | 6.186 | N/A | |

| CNN | 36 | 0.998 | 0.996 | 0.991 | 0.079 | 0.108 | 0.145 | 1.759 | 2.406 | 3.192 | 16.357 | 10.568 | N/A | |

| LSTM | 50 | 0.994 | 0.996 | 0.985 | 0.136 | 0.100 | 0.185 | 3.017 | 2.223 | 4.079 | 17.266 | 8.271 | N/A | |

| CNN-LSTM | 74 | 0.995 | 0.997 | 0.994 | 0.120 | 0.084 | 0.117 | 2.664 | 1.879 | 2.589 | 19.561 | 13.023 | N/A | |

| ELM | Full | 228 | 0.977 | 0.965 | 0.950 | 0.269 | 0.301 | 0.343 | 5.991 | 6.688 | 7.571 | 5.478 | 4.481 | N/A |

| CARS | 29 | 0.972 | 0.971 | 0.962 | 0.295 | 0.274 | 0.299 | 6.551 | 6.085 | 6.601 | 6.016 | 5.120 | N/A | |

| SPA | 60 | 0.979 | 0.969 | 0.954 | 0.255 | 0.283 | 0.328 | 5.664 | 6.305 | 7.231 | 5.715 | 4.702 | N/A | |

| CNN | 36 | 0.993 | 0.990 | 0.981 | 0.150 | 0.163 | 0.211 | 3.329 | 3.623 | 4.660 | 11.253 | 7.243 | N/A | |

| LSTM | 50 | 0.991 | 0.989 | 0.971 | 0.172 | 0.173 | 0.261 | 3.817 | 3.841 | 5.763 | 9.350 | 5.973 | N/A | |

| CNN-LSTM | 74 | 0.992 | 0.994 | 0.983 | 0.163 | 0.130 | 0.202 | 3.615 | 2.893 | 4.452 | 12.778 | 7.574 | N/A |

| Model | Method | Dimension | RMSEC | RMSEV | RMSET | rRMSEC | rRMSEV | rRMSET | RPDV | RPDT | LVs | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CNN | CNN | 95 | 0.958 | 0.955 | 0.874 | 0.555 | 0.513 | 0.961 | 5.107 | 4.832 | 8.831 | 4.720 | 2.903 | N/A |

| LSTM | LSTM | 35 | 0.950 | 0.944 | 0.928 | 0.628 | 0.504 | 0.725 | 5.762 | 4.782 | 6.662 | 4.379 | 3.793 | N/A |

| PLSR | Full | 228 | 0.892 | 0.865 | 0.852 | 0.886 | 0.888 | 1.039 | 8.154 | 8.371 | 9.552 | 2.724 | 2.601 | 10 |

| CARS | 127 | 0.899 | 0.861 | 0.855 | 0.856 | 0.903 | 1.029 | 7.880 | 8.505 | 9.457 | 2.681 | 2.627 | 10 | |

| SPA | 158 | 0.889 | 0.860 | 0.830 | 0.898 | 0.906 | 1.113 | 8.265 | 8.532 | 10.229 | 2.672 | 2.429 | 10 | |

| CNN | 95 | 0.975 | 0.966 | 0.942 | 0.422 | 0.447 | 0.648 | 3.887 | 4.211 | 5.959 | 5.416 | 4.228 | 11 | |

| LSTM | 35 | 0.975 | 0.969 | 0.945 | 0.440 | 0.376 | 0.632 | 4.041 | 3.562 | 5.806 | 5.810 | 4.300 | 11 | |

| CNN-LSTM | 47 | 0.995 | 0.989 | 0.964 | 0.202 | 0.219 | 0.510 | 1.854 | 2.074 | 4.689 | 9.728 | 5.316 | 12 | |

| SVM | Full | 228 | 0.997 | 0.993 | 0.973 | 0.137 | 0.203 | 0.445 | 1.264 | 1.910 | 4.088 | 11.985 | 6.077 | N/A |

| CARS | 127 | 0.998 | 0.996 | 0.967 | 0.134 | 0.152 | 0.493 | 1.237 | 1.429 | 4.530 | 13.756 | 5.498 | N/A | |

| SPA | 158 | 0.997 | 0.994 | 0.974 | 0.135 | 0.181 | 0.439 | 1.245 | 1.701 | 4.039 | 13.410 | 6.167 | N/A | |

| CNN | 95 | 0.997 | 0.990 | 0.965 | 0.140 | 0.238 | 0.507 | 1.268 | 2.428 | 4.954 | 10.192 | 5.385 | N/A | |

| LSTM | 35 | 0.997 | 0.992 | 0.933 | 0.160 | 0.185 | 0.698 | 1.471 | 1.758 | 6.417 | 11.583 | 3.878 | N/A | |

| CNN-LSTM | 47 | 0.998 | 0.995 | 0.974 | 0.135 | 0.151 | 0.440 | 1.240 | 1.436 | 4.041 | 14.152 | 6.159 | N/A | |

| ELM | Full | 228 | 0.942 | 0.904 | 0.903 | 0.651 | 0.750 | 0.843 | 5.993 | 7.070 | 7.752 | 3.252 | 3.272 | N/A |

| CARS | 127 | 0.935 | 0.906 | 0.895 | 0.689 | 0.742 | 0.876 | 6.346 | 6.990 | 8.057 | 3.265 | 3.130 | N/A | |

| SPA | 158 | 0.963 | 0.949 | 0.914 | 0.516 | 0.549 | 0.791 | 4.752 | 5.170 | 7.276 | 4.431 | 3.416 | N/A | |

| CNN | 95 | 0.987 | 0.955 | 0.939 | 0.308 | 0.512 | 0.668 | 2.836 | 4.825 | 6.143 | 4.736 | 4.068 | N/A | |

| LSTM | 35 | 0.981 | 0.963 | 0.949 | 0.385 | 0.407 | 0.610 | 3.529 | 3.862 | 5.607 | 5.331 | 4.441 | N/A | |

| CNN-LSTM | 47 | 0.997 | 0.988 | 0.964 | 0.160 | 0.233 | 0.516 | 1.468 | 2.211 | 4.742 | 9.142 | 5.251 | N/A |

| Model | PLS-DA | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Method | Full | CARS | SPA | CNN | LSTM | CNN-LSTM |

| Dimension | 228 | 129 | 30 | 27 | 26 | 21 |

| ACCC | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| ACCV | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| ACCT | 98.809 | 98.809 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| PrecisionC | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| PrecisionV | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| PrecisionT | 99.074 | 99.074 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| RecallC | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| RecallV | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| RecallT | 98.889 | 98.889 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Macro F1C | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Macro F1V | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Macro F1V | 98.965 | 98.965 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Weighted F1C | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Weighted F1V | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Weighted F1T | 98.808 | 98.808 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| LVs | 18 | 16 | 17 | 13 | 19 | 19 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wei, Y.; Liu, J.; Xi, G.; Lu, Y. Quantitative Detection of Key Parameters and Authenticity Verification for Beer Using Near-Infrared Spectroscopy. Foods 2025, 14, 3936. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14223936

Wei Y, Liu J, Xi G, Lu Y. Quantitative Detection of Key Parameters and Authenticity Verification for Beer Using Near-Infrared Spectroscopy. Foods. 2025; 14(22):3936. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14223936

Chicago/Turabian StyleWei, Yongshun, Jinming Liu, Guiqing Xi, and Yuhao Lu. 2025. "Quantitative Detection of Key Parameters and Authenticity Verification for Beer Using Near-Infrared Spectroscopy" Foods 14, no. 22: 3936. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14223936

APA StyleWei, Y., Liu, J., Xi, G., & Lu, Y. (2025). Quantitative Detection of Key Parameters and Authenticity Verification for Beer Using Near-Infrared Spectroscopy. Foods, 14(22), 3936. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14223936