Exploring Bioactive Compounds from Fruit and Vegetable By-Products with Potential for Food and Nutraceutical Applications

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Bioactive Compounds in Fruit and Vegetable By-Products

| Class of Compounds | Source Examples | Representative Compounds | Concentrations | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polyphenols | Pomegranate peel | Punicalagins, ellagic acid, gallic acid | 50.2–134.36 µg/mL | [24] |

| Apple pomace | Procyanidins B2, quercetin, hyperin | 1.50–92.62 mg/kg DW | [25] | |

| Carotenoids | Pumpkin peel | n.s. | 216.9–306.8 µg/g | [30] |

| Papaya pulp/peel | β-Carotene, lycopene, lutein | 39.3–58.7 µg/g soybean oil | [32] | |

| Dietary fibre | Banana peel | n.s. | 61.8–470.8 mg/g | [35] |

| Orange peel residues | Soluble fiber | 5.04–19.95% | [36] | |

| Insoluble fiber | 23.96–57.70% | |||

| Phytosterols | Orange seed oil | n.s. | 1.304 mg/g | [40] |

| Tomato seed oil | Sitosterol, cycloartenol, stigmasterol | 1.13–4.00 mg/g | [41] | |

| Glucosinolates | Broccoli industrial by-products | Glucoiberin, glucoerucin, glucoraphanin | 68–23,226 g/kg DW | [43] |

| Cauliflower industrial by-products | Glucoiberin, glucobrassicin, sinigrin, glucoraphanin | n.s. | [44] | |

| Essential oils | Citrus and grapefruit peel | Monoterpenes, sesquiterpenes | 1.72–96.96% | [51] |

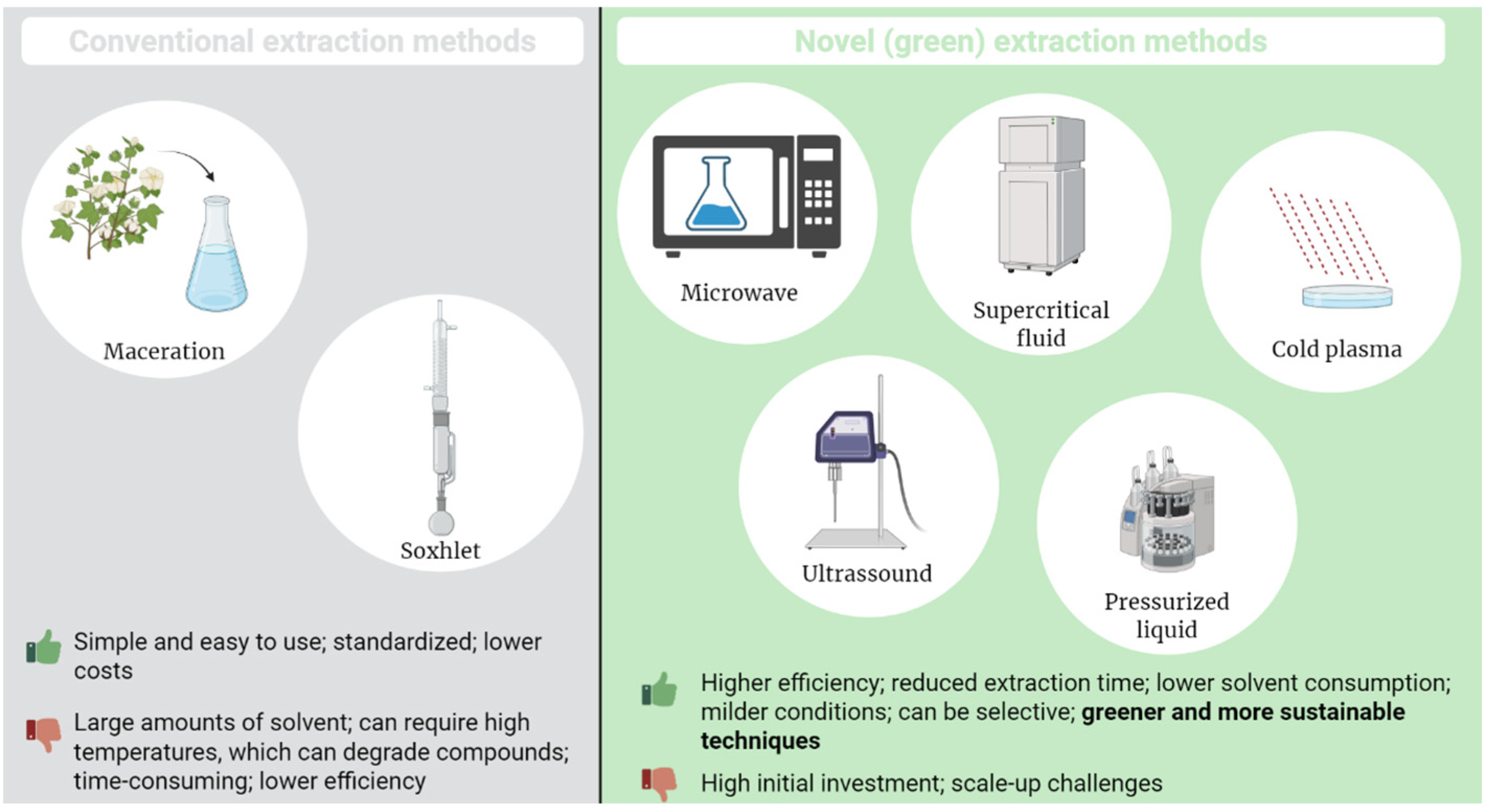

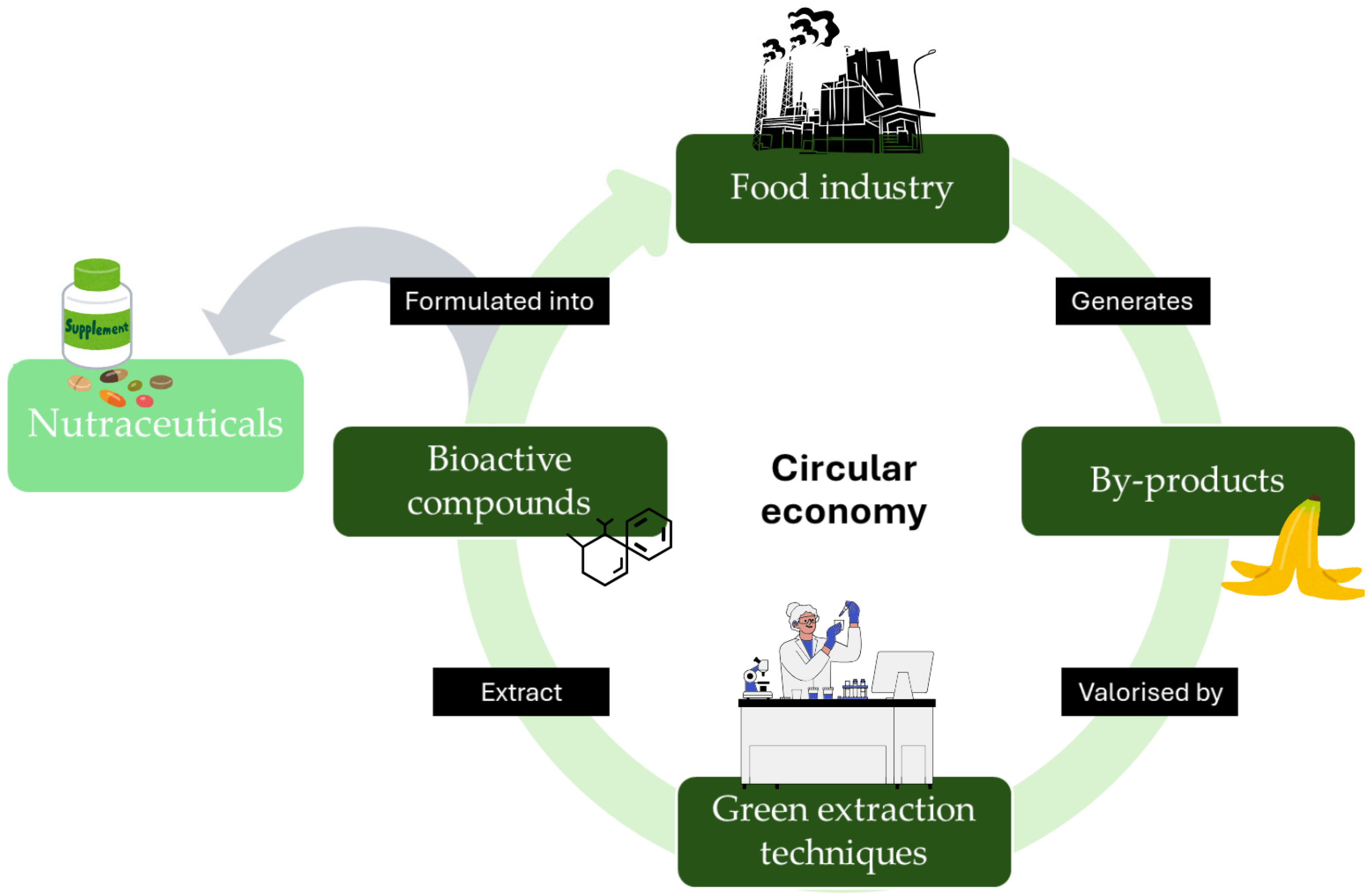

3. Extraction Technologies for Bioactive Compounds

4. By-Products of Fruit and Vegetables in Food and Nutraceutical Applications

| By-Product Source | Main Bioactive Compounds | Extraction Method | Aim | Effects | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peach, apricot, apple, tomato | Polyphenols: phenolic acids, flavonoids Other: proteins | UAE | Nutraceutical functional ingredients and dietary supplements | Antioxidant | [93] |

| Cantaloupe | Polyphenols Dietary fibre | Hydromethanolic extraction | Functional food ingredient for gluten-free bakery products | Antioxidant | [94] |

| Asparagus officinalis stem and root | Dietary fibre Insulin Low- and high-molecular-weight polyphenols | Hydromethanolic and hydroethanolic extractions | Potential prebiotic supplement or functional ingredient | Prebiotic potential for gut microbiota modulation | [95] |

| Turmeric | Phenolics, flavonoids, and curcumin Dietary fibre (insoluble & soluble) Minerals | Aqueous acetone extraction | Use as a functional ingredient in fortified cookies to enhance antioxidant and fibre content | Antioxidant | [96] |

| Oat husk and bran | Phenolic acids, mainly ferulic acid Dietary fibre | Micronization | Development of a fibre-rich antioxidant ingredient for food or dietary supplement formulations | Antioxidant | [97] |

| Grape pomace, bilberries, red currants | Major phenolics: Chlorogenic acid, rutin, ferulic acid, catechin | UAE | Dietary supplement in capsule form | Potential to prevent oxidative stress related chronic diseases | [98] |

| Apple | High total and insoluble dietary fiber Free phenolic compounds and biogenic compounds | UAE | Development of a dietary supplement | Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory Potential hypoglycaemic/antidiabetic effects | [99] |

| Artichoke | Hydroxycinnamates: 5-O-caffeoylquinic acid, 3,5-di-O-caffeoylquinic acid Flavonoids: apigenin-7-O-rutinoside, luteolin, luteolin-7-O-rutinoside | Aqueous extraction | Evaluation for nutraceutical and dietary supplement applications | Antioxidant Prebiotic potential | [100] |

| Mauritia flexuosa | - | Aqueous extraction | Evaluation for food supplement/nutraceutical for inflammation | Anti-inflammatory | [101] |

| Citrus reticulata Blanco peel and pomace | Catechin, neohesperidin, nomilinic acid derivatives | UAE | Functional ingredients for nutraceuticals or food applications | Antioxidant | [102] |

| Mango peel | Pectin | MAE | Sustainable development of prebiotics | Prebiotic | [103] |

| Pistachio hull | Cyanidin-3-O-galactoside, gallic acid, catechin, and eriodictyol-7-O-glucoside | Methanolic extraction | Food product applications potential | Antidiabetic, antifungal, antioxidant and anti-glycative | [104] |

| Guava purée | Rhamnose and xylose | Ethanolic extraction | Incorporation in yogurt-making for increased probiotics | Prebiotic | [106] |

| European cranberry bush and sea buckthorn berry pomace | Linoleic, linolenic, oleic, palmitic and palmitoleic acids, b-sitosterol and a-tocopherol | SFE | Potential application in functional foods and nutraceuticals | Antioxidant | [107] |

| Pumpkin leaves | Proteins | UAE | Potential application as food additives and dietary supplements | - | [108] |

| Mango peel | Mono- and di-galloyl compounds, gallotannins, phenolic acids, benzophenones, flavonoids | UAE | Potential application as nutraceuticals | - | [110] |

| Red pomegranate seeds | Protein and peptides | Protein extraction and enzymatic hydrolysis | Potential use in food formulations and dietary supplements | Antioxidant, antibacterial and blood pressure lowering | [109] |

| Corylus avellana hells | Lignans, flavonoids, gallic acid derivatives, diarylheptanoids and fatty acids | MAE | Nutraceutical formulations | Antidiabetic and antioxidant | [105] |

| Mango seed kernel | Iriflophenone glucoside, maclurin C-glucoside, maclurin digalloyl glucoside, mangiferin, 5-galloyl quinic acid, trigalloyl glucose, hexa-gallotannins, hepta-gallotannins | UAE | Nutraceutical formulations | - | [111] |

5. Challenges and Future Perspectives

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Khan, R.; Anwar, F.; Ghazali, F.M.; Mahyudin, N.A. Valorization of Waste: Innovative Techniques for Extracting Bioactive Compounds from Fruit and Vegetable Peels—A Comprehensive Review. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2024, 97, 103828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baysal, S.S.; Ülkü, M.A. Food Loss and Waste. In Disruptive Technologies and Eco-Innovation for Sustainable Development; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2022; pp. 90–108. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. Food Wastage Footprint-Impacts on Natural Resources—Summary Report; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Aqilah, N.M.N.; Rovina, K.; Felicia, W.X.L.; Vonnie, J.M. A Review on the Potential Bioactive Components in Fruits and Vegetable Wastes as Value-Added Products in the Food Industry. Molecules 2023, 28, 2631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.J.; Lv, C.H.; Chen, Z.; Shi, M.; Zeng, C.X.; Hou, D.X.; Qin, S. The Regulatory Effect of Phytochemicals on Chronic Diseases by Targeting Nrf2-ARE Signaling Pathway. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piccialli, I.; Tedeschi, V.; Caputo, L.; D’Errico, S.; Ciccone, R.; De Feo, V.; Secondo, A.; Pannaccione, A. Exploring the Therapeutic Potential of Phytochemicals in Alzheimer’s Disease: Focus on Polyphenols and Monoterpenes. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 876614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, V.K.; Arora, D.; Ansari, M.I.; Sharma, P.K. Phytochemicals Based Chemopreventive and Chemotherapeutic Strategies and Modern Technologies to Overcome Limitations for Better Clinical Applications. Phytother. Res. 2019, 33, 3064–3089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddique, F.; Ali, Z.; Arshad, M.; Mubeen, K.; Ghazala, A. Exploration of Novel Eco-Friendly Techniques to Utilize Bioactive Compounds from Household Food Waste: Special Reference to Food Applications. Front. Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 4, 1388461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nirmal, N.P.; Khanashyam, A.C.; Mundanat, A.S.; Shah, K.; Babu, K.S.; Thorakkattu, P.; Al-Asmari, F.; Pandiselvam, R. Valorization of Fruit Waste for Bioactive Compounds and Their Applications in the Food Industry. Foods 2023, 12, 556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares Mateus, A.R.; Pena, A.; Sanches-Silva, A. Unveiling the Potential of Bioactive Compounds in Vegetable and Fruit By-Products: Exploring Phytochemical Properties, Health Benefits, and Industrial Opportunities. Curr. Opin. Green Sustain. Chem. 2024, 48, 100938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artés-Hernández, F.; Castillejo, N.; Martínez-Zamora, L.; Martínez-Hernández, G.B. Phytochemical Fortification in Fruit and Vegetable Beverages with Green Technologies. Foods 2021, 10, 2534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panzella, L.; Moccia, F.; Nasti, R.; Marzorati, S.; Verotta, L.; Napolitano, A. Bioactive Phenolic Compounds from Agri-Food Wastes: An Update on Green and Sustainable Extraction Methodologies. Front. Nutr. 2020, 7, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seyyedi-Mansour, S.; Donn, P.; Carpena, M.; Chamorro, F.; Barciela, P.; Perez-Vazquez, A.; Jorge, A.O.S.; Prieto, M.A. Utilization of Ultrasonic-Assisted Extraction for Bioactive Compounds from Floral Sources. In Proceedings of the 5th International Electronic Conference on Foods, Virtual, 21 January 2025; MDPI: Basel, Switzerland. 15p. [Google Scholar]

- Durmus, N.; Gulsunoglu-Konuskan, Z.; Kilic-Akyilmaz, M. Recovery, Bioactivity, and Utilization of Bioactive Phenolic Compounds in Citrus Peel. Food Sci. Nutr. 2024, 12, 9974–9997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandyliari, A.; Potsaki, P.; Bousdouni, P.; Kaloteraki, C.; Christofilea, M.; Almpounioti, K.; Moutsou, A.; Fasoulis, C.K.; Polychronis, L.V.; Gkalpinos, V.K.; et al. Development of Dairy Products Fortified with Plant Extracts: Antioxidant and Phenolic Content Characterization. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurćubić, V.S.; Stanišić, N.; Stajić, S.B.; Dmitrić, M.; Živković, S.; Kurćubić, L.V.; Živković, V.; Jakovljević, V.; Mašković, P.Z.; Mašković, J. Valorizing Grape Pomace: A Review of Applications, Nutritional Benefits, and Potential in Functional Food Development. Foods 2024, 13, 4169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luisa García, M.; Calvo, M.M.; Dolores Selgas, M. Beef Hamburgers Enriched in Lycopene Using Dry Tomato Peel as an Ingredient. Meat Sci. 2009, 83, 45–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamasiga, P.; Miri, T.; Onyeaka, H.; Hart, A. Food Waste and Circular Economy: Challenges and Opportunities. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillejo, N.; Martínez-Zamora, L. Bioactive Compounds from Fruit and Vegetable Waste: Extraction and Possible Utilization. Foods 2024, 13, 775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subhan, S.; Zeeshan, M.; Rahman, A.U.; Yaseen, M. Fundamentals of Polyphenols: Nomenclature, Classification and Properties. In Science and Engineering of Polyphenols; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2024; pp. 1–36. [Google Scholar]

- Kondratyuk, T.P.; Pezzuto, J.M. Natural Product Polyphenols of Relevance to Human Health. Arch. Physiol. Biochem. 2004, 42, 46–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brimson, J.M.; Prasanth, M.I.; Malar, D.S.; Thitilertdecha, P.; Kabra, A.; Tencomnao, T.; Prasansuklab, A. Plant Polyphenols for Aging Health: Implication from Their Autophagy Modulating Properties in Age-Associated Diseases. Pharmaceuticals 2021, 14, 982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Kong, K.W.; Wu, D.-T.; Liu, H.-Y.; Li, H.-B.; Zhang, J.-R.; Gan, R.-Y. Pomegranate Peel-Derived Punicalagin: Ultrasonic-Assisted Extraction, Purification, and Its α-Glucosidase Inhibitory Mechanism. Food Chem. 2022, 374, 131635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahmood, A.; Jabar, H. Characterization of Biochemical Compounds in Different Accessions of Pomegranate (Punica granatum L.) Peels in Iraq. Passer J. Basic. Appl. Sci. 2023, 5, 382–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, X.; Zhang, H.; Ren, S. Antioxidant Activity and HPLC Analysis of Polyphenol-enriched Extracts from Industrial Apple Pomace. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2013, 93, 2502–2506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cazzonelli, C.I. Carotenoids in Nature: Insights from Plants and Beyond. Funct. Plant Biol. 2011, 38, 833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priyadarshini Pradhan, S.; Padhi, S.; Dash, M.; Heena; Mittu, B.; Behera, A. Carotenoids. In Nutraceuticals and Health Care; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 135–157. [Google Scholar]

- Vílchez, C.; Forján, E.; Cuaresma, M.; Bédmar, F.; Garbayo, I.; Vega, J.M. Marine Carotenoids: Biological Functions and Commercial Applications. Mar. Drugs 2011, 9, 319–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heider, S.A.E.; Peters-Wendisch, P.; Wendisch, V.F.; Beekwilder, J.; Brautaset, T. Metabolic Engineering for the Microbial Production of Carotenoids and Related Products with a Focus on the Rare C50 Carotenoids. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2014, 98, 4355–4368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lima, P.M.; Rubio, F.T.V.; Silva, M.P.; Pinho, L.S.; Kasemodel, M.G.C.; Favaro-Trindade, C.S.; Dacanal, G.C. Nutritional Value and Modelling of Carotenoids Extraction from Pumpkin (Cucurbita moschata) Peel Flour By-Product. Int. J. Food Eng. 2019, 15, 20180381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ninčević Grassino, A.; Rimac Brnčić, S.; Badanjak Sabolović, M.; Šic Žlabur, J.; Marović, R.; Brnčić, M. Carotenoid Content and Profiles of Pumpkin Products and By-Products. Molecules 2023, 28, 858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lara-Abia, S.; Welti-Chanes, J.; Cano, M.P. Effect of Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction of Carotenoids from Papaya (Carica papaya L. Cv. Sweet Mary) Using Vegetable Oils. Molecules 2022, 27, 638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedayati, S.; Tarahi, M.; Ashrafi-Dehkordi, E. Dietary Fibers from Fruit Processing Waste. In Adding Value to Fruit Wastes; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024; pp. 131–165. [Google Scholar]

- Oreopoulou, V.; Tzia, C. Utilization of Plant By-Products for the Recovery of Proteins, Dietary Fibers, Antioxidants, and Colorants. In Utilization of By-Products and Treatment of Waste in the Food Industry; Springer: New York, NY, USA; pp. 209–232.

- Paramitasari, D.; Pramana, Y.S.; Suparman, S.; Putra, O.N.; Musa, M.; Pudjianto, K.; Triwiyono, B.; Supriyanti, A.; Elisa, S.; Singgih, B.; et al. Valorization of Lampung Province Banana Peel Cultivars: Nutritional and Functional Characterizations for Biscuit Production and Wheat Flour Substitution. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2024, 18, 9906–9920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, J.M.d.M.; Jong, E.V.d.; Henriques, A.T. Byproducts of Orange Extraction: Influence of Different Treatments in Fiber Composition and Physical and Chemical Parameters. Braz. J. Pharm. Sci. 2014, 50, 473–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Sáenz, C.; Estévez, A.M.; Sanhueza, S. Orange Juice Residues as Dietary Fiber Source for Foods. Arch. Latinoam. Nutr. 2007, 57, 186–191. [Google Scholar] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Carlucci, R.; Arancibia, J.A.; Labadie, G.R. Environmentally Friendly Process for Phytosterols Recovery from Residues of Biodiesel Production. Sustain. Chem. Pharm. 2024, 37, 101360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poudel, P.; Petropoulos, S.A.; Di Gioia, F. Plant Tocopherols and Phytosterols and Their Bioactive Properties. In Natural Secondary Metabolites; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 285–319. [Google Scholar]

- Jorge, N.; Silva, A.C.d.; Aranha, C.P.M. Antioxidant Activity of Oils Extracted from Orange (Citrus sinensis) Seeds. Acad. Bras. Cienc. 2016, 88, 951–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eller, F.J.; Moser, J.K.; Kenar, J.A.; Taylor, S.L. Extraction and Analysis of Tomato Seed Oil. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 2010, 87, 755–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Z.-X. Effect of Postharvest and Industrial Processing on Glucosinolate from Broccoli: A Review. Am. J. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2022, 18, 168–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, M.; Badr, A.; Desjardins, Y.; Gosselin, A.; Angers, P. Characterization of Industrial Broccoli Discards (Brassica oleracea Var. Italica) for Their Glucosinolate, Polyphenol and Flavonoid Contents Using UPLC MS/MS and Spectrophotometric Methods. Food Chem. 2018, 245, 1204–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingallina, C.; Di Matteo, G.; Spano, M.; Acciaro, E.; Campiglia, E.; Mannina, L.; Sobolev, A.P. Byproducts of Globe Artichoke and Cauliflower Production as a New Source of Bioactive Compounds in the Green Economy Perspective: An NMR Study. Molecules 2023, 28, 1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baser, K.H.C.; Buchbauer, G. (Eds.) Handbook of Essential Oils; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2015; ISBN 9780429155666. [Google Scholar]

- Mollaei, S.; Farnia, P.; Hazrati, S. Chapter 5 Essential Oils and Their Constituents. In Essential Oils; De Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 2023; pp. 89–120. [Google Scholar]

- Nikolić, B.M.; Ballian, D.; Mitić, Z.S.S. Diversity of Needle Terpenes Among Pinus Taxa. Forests 2025, 16, 623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popovici, J.; Bertrand, C.; Bagnarol, E.; Fernandez, M.P.; Comte, G. Chemical Composition of Essential Oil and Headspace-Solid Microextracts from Fruits of Myrica gale L. and Antifungal Activity. Nat. Prod. Res. 2008, 22, 1024–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, M.A.; Ibrahim, M.E.; Wahba, H.E. Flavoring Compounds of Essential Oil Isolated from Agriculture Waste of Coriander (Coriandrum sativum) Plant. J. Mater. Environ. Sci. 2018, 9, 77–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grover, S.; Aggarwal, P.; Kaur, S.; Yadav, R.; Kumar, A. Physicochemical Assessment, Characterization, Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Potential Study of Essential Oil Extracted from the Peel of Different Galgal (Citrus pseudolimon) Cultivars. Waste Biomass Valorization 2024, 15, 3157–3167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.-Y.; Peng, C.C.; Huang, Y.-P.; Chen, K.-C.; Peng, R.Y. P-Synephrine Indicates Internal Maturity of Citrus grandis (L.) Osbeck Cv. Mato Peiyu—Reclaiming Functional Constituents from Nonedible Parts. Molecules 2023, 28, 4244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghani, A.; Mohtashami, S.; Jamalian, S. Peel Essential Oil Content and Constituent Variations and Antioxidant Activity of Grapefruit (Citrus × paradisi Var. Red Blush) during Color Change Stages. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2021, 15, 4917–4928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M.M.; Islam, M.R.; Haque, A.R.; Kabir, M.R.; Khushe, K.J.; Hasan, S.M.K. Trends and Challenges of Fruit By-Products Utilization: Insights into Safety, Sensory, and Benefits of the Use for the Development of Innovative Healthy Food: A Review. Bioresour. Bioprocess. 2024, 11, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gębczyński, P.; Tabaszewska, M.; Kur, K.; Zbylut-Górska, M.; Słupski, J. Effect of the Drying Method and Storage Conditions on the Quality and Content of Selected Bioactive Compounds of Green Legume Vegetables. Molecules 2024, 29, 1732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, A.J.; Stewart, R.F. Phenols. In Encyclopedia of Ecology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2008; pp. 2682–2689. [Google Scholar]

- Amruthraj Nagoth, J.; Poonga Preetam Raj, J.; Joseph Amruthraj, N.; Raj, P.J.; Lebel, A.L. Impact of Organic Solvents in the Extraction Efficiency of Therapeutic Analogue Capsaicin from Capsicum Chinense Bhut Jolokia Fruits. Int. J. Pharm. Clin. Res. 2014, 6, 159–164. [Google Scholar]

- Melicháčová, S.; Timoracká, M.; Bystrická, J.; Vollmannová, A.; Čéry, J. Relation of Total Antiradical Activity and Total Polyphenol Content of Sweet Cherries (Prunus avium L.) and Tart Cherries (Prunus cerasus L.). Acta Agric. Slov. 2010, 95, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liazid, A.; Palma, M.; Brigui, J.; Barroso, C.G. Investigation on Phenolic Compounds Stability during Microwave-Assisted Extraction. J. Chromatogr. A 2007, 1140, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakshmanan, M. Plant Extraction Methods. In Introduction to Basics of Pharmacology and Toxicology; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2022; pp. 773–783. [Google Scholar]

- Subbalakshmi, G.; Nagamani, J.E.; Mohanty, S.K.; Umalatha; Anuradha, M. Analytical Methods for Screening High Yielding In Vitro Cultures. In In Vitro Production of Plant Secondary Metabolites; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2025; pp. 297–308. [Google Scholar]

- Rajasekar, A.; Deivasigamani, P.; Amar, G.; Moorthi, M.; Sekar, S. A Review on Screening, Isolation, and Characterization of Phytochemicals in Plant Materials. In Pharmacological Benefits of Natural Agents; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2023; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Mahibalan, S.; Sharma, R.; Vyas, A.; Bashab, S.A.; Begum, A.S. Assessment of Extraction Techniques for Total Phenolics and Flavonoids from Annona Muricata Seeds. J. Indian Chem. Soc. 2013, 90, 2199–2205. [Google Scholar]

- Picot-Allain, C.; Mahomoodally, M.F.; Ak, G.; Zengin, G. Conventional versus Green Extraction Techniques—A Comparative Perspective. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2021, 40, 144–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurora, A.; Lund, M.N.; Tiwari, B.K.; Poojary, M.M. Application of Ultrasound to Obtain Food Additives and Nutraceuticals. In Design and Optimization of Innovative Food Processing Techniques Assisted by Ultrasound; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 111–141. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, J.; Zhou, P.; Li, X.; Lu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Yuan, H.; Yang, Y. Ultrasound-Assisted Deep Eutectic Solvent Extraction of Flavonol Glycosides from Ginkgo Biloba: Optimization of Efficiency and Mechanism. Ultrason. Sonochem 2025, 114, 107254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faheema, K.K.; Mohan, A.; Komathkandy, F. Comprehensive Study on Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction (UAE) of Bioactive Compounds with Medicinal Properties from Date Processing Byproduct. Eur. J. Nutr. Food Saf. 2024, 16, 203–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusoff, I.M.; Mat Taher, Z.; Rahmat, Z.; Chua, L.S. A Review of Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction for Plant Bioactive Compounds: Phenolics, Flavonoids, Thymols, Saponins and Proteins. Food Res. Int. 2022, 157, 203–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, X.; Cui, Y.; Yuan, W. Ultrasound for Microalgal Cell Disruption and Product Extraction: A Review. Ultrason. Sonochem 2022, 87, 106054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picó, Y. Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction for Food and Environmental Samples. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2013, 43, 84–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özdemir, M.; Yıldırım, R.; Yurttaş, R.; Başargan, D.; Hakcı, M.B. A Review of Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction of Bioactive Compounds from Coffee Waste. Gıda 2025, 50, 56–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delazar, A.; Nahar, L.; Hamedeyazdan, S.; Sarker, S.D. Microwave-Assisted Extraction in Natural Products Isolation. In Natural Products Isolation; Human Press: Waverley, Australia, 2012; pp. 89–115. [Google Scholar]

- López-Salazar, H.; Camacho-Díaz, B.H.; Ocampo, M.L.A.; Jiménez-Aparicio, A.R. Microwave-Assisted Extraction of Functional Compounds from Plants: A Review. Bioresources 2023, 18, 6614–6638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calinescu, I.; Lavric, V.; Asofiei, I.; Gavrila, A.I.; Trifan, A.; Ighigeanu, D.; Martin, D.; Matei, C. Microwave Assisted Extraction of Polyphenols Using a Coaxial Antenna and a Cooling System. Chem. Eng. Process. Process Intensif. 2017, 122, 373–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samanta, R.; Ghosh, M. Optimization of Microwave-Assisted Extraction Technique for Flavonoids and Phenolics from the Leaves of Oroxylum indicum (L.) Kurtz Using Taguchi L9 Orthogonal Design. Pharmacogn. Mag. 2023, 19, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irianto, I.; Putra, N.R.; Yustisia, Y.; Abdullah, S.; Syafruddin, S.; Paesal, P.; Irmadamayanti, A.; Herawati, H.; Raharjo, B.; Agustini, S.; et al. Green Technologies in Food Colorant Extraction: A Comprehensive Review. S. Afr. J. Chem. Eng. 2025, 51, 22–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soni, N.; Yadav, M.; Malarvannan, M.; Sharma, D.; Paul, D. Current Developments and Trends in Hybrid Extraction Techniques for Green Analytical Applications in Natural Products. J. Chromatogr. B 2025, 1256, 124543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrero, M.; Cifuentes, A.; Ibanez, E. Sub- and Supercritical Fluid Extraction of Functional Ingredients from Different Natural Sources: Plants, Food-by-Products, Algae and Microalgae A Review. Food Chem. 2006, 98, 136–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, R.P.F.F.; Rocha-Santos, T.A.P.; Duarte, A.C. Supercritical Fluid Extraction of Bioactive Compounds. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2016, 76, 40–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibáñez, E.; Mendiola, J.A.; Castro-Puyana, M. Supercritical Fluid Extraction. In Encyclopedia of Food and Health; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016; pp. 227–233. [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Vazquez, A.; Barciela, P.; Carpena, M.; Donn, P.; Seyyedi-Mansour, S.; Cao, H.; Fraga-Corral, M.; Otero, P.; Simal-Gandara, J.; Prieto, M.A.; et al. Supercritical Fluid Extraction as a Potential Extraction Technique for the Food Industry. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Electronic Conference on Processes: Process Engineering—Current State and Future Trends, Online, 17 May 2023; MDPI: Basel, Switzerland. 115p. [Google Scholar]

- Mohamed-Mahmood, M.; Ramli, W.; Daud, W.; Markom, M.; Nurul, C.; Nadirah, A.; Mansor, C.; Latif C A Jabatan, J.; Kimia, K.; Proses, D.; et al. Effects of Pressure Variation and Dynamic Extraction Time in Supercritical Fluid Extraction (SFE) with Co-Solvent on Bioactive Compounds from Orthosiphon Stamineus. Malays. J. Fundam. Appl. Sci. 2019, 15, 712–715. [Google Scholar]

- Herzyk, F.; Piłakowska-Pietras, D.; Korzeniowska, M. Supercritical Extraction Techniques for Obtaining Biologically Active Substances from a Variety of Plant Byproducts. Foods 2024, 13, 1713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Andrade Maia, F.; Fasolin, L.H. Recovery of Bioactive Compounds from Pineapple Waste through High-Pressure Technologies. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2025, 218, 106455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Andrade Lima, M.; Kestekoglou, I.; Charalampopoulos, D.; Chatzifragkou, A. Supercritical Fluid Extraction of Carotenoids from Vegetable Waste Matrices. Molecules 2019, 24, 466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barp, L.; Višnjevec, A.M.; Moret, S. Pressurized Liquid Extraction: A Powerful Tool to Implement Extraction and Purification of Food Contaminants. Foods 2023, 12, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreu, V.; Picó, Y. Pressurized Liquid Extraction of Organic Contaminants in Environmental and Food Samples. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2019, 118, 709–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieto, J.A.; Santoyo, S.; de Sá, M.; Baoshan, S.; Reglero, G.; Jaime, L. Comprehensive Study of Sustainable Pressurized Liquid Extractions to Obtain Bioavailable Antioxidant Phenolic Compounds from Grape Seed By-Products. Processes 2024, 12, 2308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puente-Díaz, L. Principios, Aplicaciones y Efectos de La Aplicación de Plasma Frío En Alimentos: Una Revisión Actualizada. Rev. Chil. Nutr. 2024, 51, 155–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, K.K.; Routray, W. Cold Plasma: A Nonthermal Pretreatment, Extraction, and Solvent Activation Technique for Obtaining Bioactive Compounds from Agro-Food Industrial Biomass. Food Chem. 2025, 472, 142960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loukri, A.; Kissas, T.; Kyriakoudi, A.; Zymvrakaki, E.; Stratakos, A.C.; Mourtzinos, I. Coupling of Cold Atmospheric Plasma Treatment with Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction for Enhanced Recovery of Bioactive Compounds from Cornelian Cherry Pomace. Food Chem. 2024, 455, 139989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vilas-Boas, A.A.; Oliveira, A.; Ribeiro, T.B.; Ribeiro, S.; Nunes, C.; Gómez-García, R.; Nunes, J.; Pintado, M. Impact of Extraction Process in Non-Compliant ‘Bravo de Esmolfe’ Apples towards the Development of Natural Antioxidant Extracts. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 5916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wei, Y.; Fan, Z.; Chen, Y.; Cui, Z. Life Cycle Assessment for Evaluation of Novel Solvents and Technologies: A Case Study of Flavonoids Extraction from Ginkgo biloba Leaves. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 922, 171319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terenzi, C.; Bermudez, G.; Medri, F.; Davani, L.; Tumiatti, V.; Andrisano, V.; Montanari, S.; De Simone, A. Phenolic and Antioxidant Characterization of Fruit By-Products for Their Nutraceuticals and Dietary Supplements Valorization under a Circular Bio-Economy Approach. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namir, M.; Rabie, M.A.; Rabie, N.A. Physicochemical, Pasting, and Sensory Characteristics of Antioxidant Dietary Fiber Gluten-Free Donut Made from Cantaloupe By-Products. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2021, 15, 5445–5459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goñi, I.; García-Alonso, A.; Alba, C.; Rodríguez, J.M.; Sánchez-Mata, M.C.; Guillén-Bejarano, R.; Redondo-Cuenca, A. Composition and Functional Properties of the Edible Spear and By-Products from Asparagus officinalis L. and Their Potential Prebiotic Effect. Foods 2024, 13, 1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, T.T.; Nguyen, T.K.; Ton, N.M.N.; Tran, T.T.T.; Le, V.V.M. Quality of Cookies Supplemented with Various Levels of Turmeric By-Product Powder. AIMS Agric. Food 2024, 9, 209–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dziki, D.; Gawlik-Dziki, U.; Tarasiuk, W.; Różyło, R. Fiber Preparation from Micronized Oat By-Products: Antioxidant Properties and Interactions between Bioactive Compounds. Molecules 2022, 27, 2621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frum, A.; Dobrea, C.M.; Rus, L.L.; Virchea, L.-I.; Morgovan, C.; Chis, A.A.; Arseniu, A.M.; Butuca, A.; Gligor, F.G.; Vicas, L.G.; et al. Valorization of Grape Pomace and Berries as a New and Sustainable Dietary Supplement: Development, Characterization, and Antioxidant Activity Testing. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tlais, A.Z.A.; Da Ros, A.; Filannino, P.; Vincentini, O.; Gobbetti, M.; Di Cagno, R. Biotechnological Re-Cycling of Apple by-Products: A Reservoir Model to Produce a Dietary Supplement Fortified with Biogenic Phenolic Compounds. Food Chem. 2021, 336, 127616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caponio, G.R.; Vacca, M.; Scalvenzi, L.; Annunziato, A.; Silletti, R.; Ruta, C.; Difonzo, G.; De Angelis, M.; De Mastro, G. Phenolic Characterization and Nutraceutical Evaluation of By-products from Different Globe Artichoke Cultivars. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2025, 105, 5062–5073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amorim, V.R.; Rodrigues, D.C.d.N.; Silva, J.d.N.; Ramos, C.L.S.; Almeida, L.M.N.; Almeida, A.A.C.; Pinheiro-Neto, F.R.; Almeida, F.R.C.; Rizzo, M.S.; Pereira-Freire, J.A.; et al. Anti-Inflammatory Mechanisms of Fruits and by-Products from Mauritia Flexuosa, an Exotic Plant with Functional Benefits. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health A 2021, 84, 441–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Negi, P.S. Multivariate Analysis of the Efficiency of Bio-Actives Extraction from Laboratory-Generated By-Products of Citrus Reticulata Blanco. J. Food Sci. 2025, 90, e70304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wongkaew, M.; Tinpovong, B.; Sringarm, K.; Leksawasdi, N.; Jantanasakulwong, K.; Rachtanapun, P.; Hanmoungjai, P.; Sommano, S.R. Crude Pectic Oligosaccharide Recovery from Thai Chok Anan Mango Peel Using Pectinolytic Enzyme Hydrolysis. Foods 2021, 10, 627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gharibi, S.; Matkowski, A.; Sarfaraz, D.; Mirhendi, H.; Fakhim, H.; Szumny, A.; Rahimmalek, M. Identification of Polyphenolic Compounds Responsible for Antioxidant, Anti-Candida Activities and Nutritional Properties in Different Pistachio (Pistacia vera L.) Hull Cultivars. Molecules 2023, 28, 4772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maccarronello, A.E.; Cardullo, N.; Silva, A.M.; Di Francesco, A.; Costa, P.C.; Rodrigues, F.; Muccilli, V. Unlocking the Nutraceutical Potential of Corylus Avellana L. Shells: Microwave-assisted Extraction of Phytochemicals with Antiradical and Anti-diabetic Properties. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2024, 104, 9472–9485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, C.Y.; Lee, K.C.; Chang, Y.P. Cellulase-Xylanase-Treated Guava Purée By-Products as Prebiotics Ingredients in Yogurt. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 2022, 77, 299–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dienaitė, L.; Baranauskienė, R.; Rimantas Venskutonis, P. Lipophilic Extracts Isolated from European Cranberry Bush (Viburnum opulus) and Sea Buckthorn (Hippophae rhamnoides) Berry Pomace by Supercritical CO2–Promising Bioactive Ingredients for Foods and Nutraceuticals. Food Chem. 2021, 348, 129047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mijalković, J.; Šekuljica, N.; Jakovetić Tanasković, S.; Petrović, P.; Balanč, B.; Korićanac, M.; Conić, A.; Bakrač, J.; Đorđević, V.; Bugarski, B.; et al. Ultrasound as Green Technology for the Valorization of Pumpkin Leaves: Intensification of Protein Recovery. Molecules 2024, 29, 4027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbarbaglu, Z.; Mazloomi, N.; Karimzadeh, L.; Sarabandi, K.; Jafari, S.M.; Hesarinejad, M.A. Nutritional Value, Antibacterial Activity, ACE and DPP IV Inhibitory of Red Pomegranate Seeds Protein and Peptides. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 10802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alañón, M.E.; Pimentel-Moral, S.; Arráez-Román, D.; Segura-Carretero, A. Profiling Phenolic Compounds in Underutilized Mango Peel By-Products from Cultivars Grown in Spanish Subtropical Climate over Maturation Course. Food Res. Int. 2021, 140, 109852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alañón, M.E.; Pimentel-Moral, S.; Arráez-Román, D.; Segura-Carretero, A. HPLC-DAD-Q-ToF-MS Profiling of Phenolic Compounds from Mango (Mangifera indica L.) Seed Kernel of Different Cultivars and Maturation Stages as a Preliminary Approach to Determine Functional and Nutraceutical Value. Food Chem. 2021, 337, 127764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tadesse Tsegay, Z.; Smaoui, S.; Varzakas, T. Toxicological Qualities and Detoxification Trends of Fruit By-Products for Valorization: A Review. Open Life Sci. 2025, 20, 20251105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katsouli, M.; Thanou, I.V.; Raftopoulou, E.; Ntzimani, A.; Taoukis, P.; Giannakourou, M.C. Bioaccessibility and Stability Studies on Encapsulated Phenolics and Carotenoids from Olive and Tomato Pomace: Development of a Functional Fruit Beverage. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 10495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vettorazzi, A.; López de Cerain, A.; Sanz-Serrano, J.; Gil, A.G.; Azqueta, A. European Regulatory Framework and Safety Assessment of Food-Related Bioactive Compounds. Nutrients 2020, 12, 613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Carvalho, F.; Lahlou, R.A.; Silva, L.R. Exploring Bioactive Compounds from Fruit and Vegetable By-Products with Potential for Food and Nutraceutical Applications. Foods 2025, 14, 3884. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14223884

Carvalho F, Lahlou RA, Silva LR. Exploring Bioactive Compounds from Fruit and Vegetable By-Products with Potential for Food and Nutraceutical Applications. Foods. 2025; 14(22):3884. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14223884

Chicago/Turabian StyleCarvalho, Filomena, Radhia Aitfella Lahlou, and Luís R. Silva. 2025. "Exploring Bioactive Compounds from Fruit and Vegetable By-Products with Potential for Food and Nutraceutical Applications" Foods 14, no. 22: 3884. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14223884

APA StyleCarvalho, F., Lahlou, R. A., & Silva, L. R. (2025). Exploring Bioactive Compounds from Fruit and Vegetable By-Products with Potential for Food and Nutraceutical Applications. Foods, 14(22), 3884. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14223884