How Does Perceived Value Influence Functional Snack Consumption Intention? An Empirical Analysis Based on Generational Differences

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- How do different value dimensions affect consumers’ consumption intention?

- (2)

- How do these relationships differ between Generation Y and Generation Z?

- (3)

- Which combinations of value dimensions effectively trigger strong consumption intention?

2. Literature Review and Research Hypotheses

2.1. Perceived Value Theory

2.2. Self-Oriented Value and Other-Oriented Value

2.3. Perceived Value and Consumption Intention

2.4. Generational Moderation Effects

3. Research Design

3.1. Variable Measurement

3.2. Questionnaire Design and Data Collection

3.3. Research Methods

4. Results

4.1. Common Method Bias Tests

4.2. Assessment of Measurement Model

4.3. Assessment of Structural Model

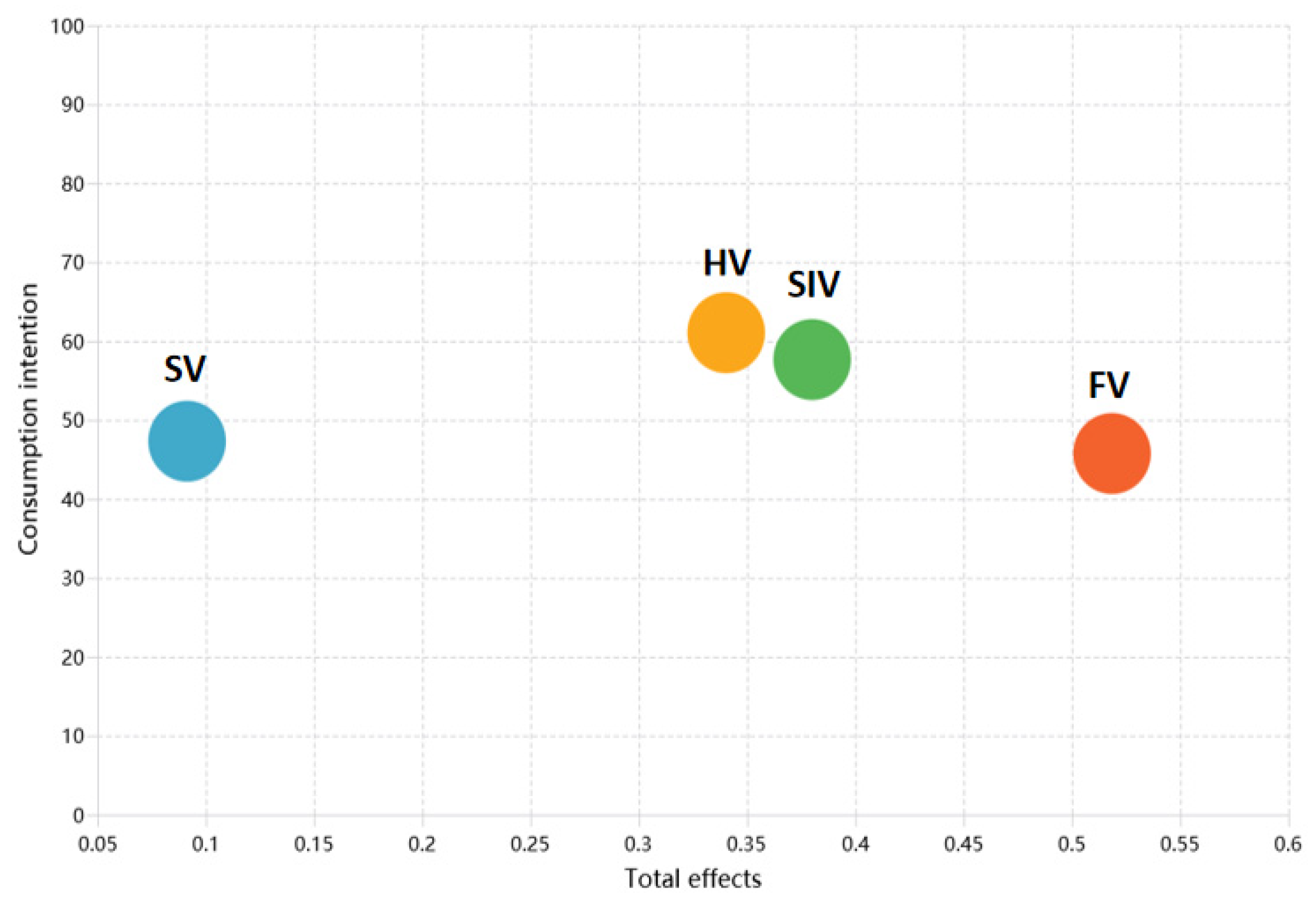

4.4. Importance–Performance Map Analysis

4.5. Fuzzy-Set Qualitative Comparative Analysis

5. Discussion

5.1. The Impact Mechanisms of Perceived Value

5.2. Findings on Generational Moderation Effects

5.3. IPMA Findings

5.4. Configurational Analysis

6. Conclusions and Implications

6.1. Research Conclusions

6.2. Theoretical Contributions

6.3. Practical Implications

6.4. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- China Insights Consultancy. China Snack Industry Blue Book 2024. Available online: https://www.baogaobox.com/insights/241225000005015.html (accessed on 5 January 2025).

- Euromonitor International. Essential Items: Willingness to Pay More in Emerging or Developing Markets. Available online: https://www.euromonitor.com/article/essential-items-willingness-to-pay-more-in-emerging-or-developing-markets (accessed on 5 January 2025).

- Applegate, E.; Carins, J.; Vincze, L.; Stainer, M.; Irwin, C. The impact of front-of-package design features on consumers’ attention and selection likelihood of protein bars: An eye-tracking study. Food Qual. Prefer. 2025, 126, 105427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, M.; Sharma, C.; Mehta, A.; Torrico, D.D. Health claim effects on consumer acceptability, emotional responses, and purchase intent of protein bars. J. Agric. Food Res. 2022, 8, 100291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uliano, A.; Stanco, M.; Marotta, G.; Nazzaro, C. Combining healthiness and sustainability: An analysis of consumers’ preferences and willingness to pay for functional and sustainable snack bars. Future Foods 2024, 9, 100355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barauskaite, D.; Gineikiene, J.; Fennis, B.M.; Auruskeviciene, V.; Yamaguchi, M.; Kondo, N. Eating healthy to impress: How conspicuous consumption, perceived self-control motivation, and descriptive normative influence determine functional food choices. Appetite 2018, 131, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lähteenmäki, L. Claiming health in food products. Food Qual. Prefer. 2013, 27, 196–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priporas, C.-V.; Stylos, N.; Fotiadis, A.K. Generation Z consumers’ expectations of interactions in smart retailing: A future agenda. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 77, 374–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slootweg, E.; Rowson, B. My generation: A review of marketing strategies on different age groups. Res. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 8, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djafarova, E.; Bowes, T. ‘Instagram made Me buy it’: Generation Z impulse purchases in fashion industry. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 59, 102345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shetu, S.N. Do user-generated content and micro-celebrity posts encourage generation Z users to search online shopping behavior on social networking sites—The moderating role of sponsored ads. Future Bus. J. 2023, 9, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeithaml, V.A. Consumer perceptions of price, quality, and value: A means-end model and synthesis of evidence. J. Mark. 1988, 52, 2–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leroi-Werelds, S. An update on customer value: State of the art, revised typology, and research agenda. J. Serv. Manag. 2019, 30, 650–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusnara, R.I.; Soepatini, S. Utilitarian, hedonic, and social values on e-commerce customer loyalty: Mediating role of customer satisfaction. J. Enterp. Dev. (JED) 2023, 5, 296–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.-J.; Oh, H.-I.; Yang, J.-Y.; Oh, J.-E.; Kang, N.-E.; Cho, M.-S. A study on the consumer’s preference and purchasing behavior of high-protein bars with soy protein isolate. J. Korean Soc. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 49, 270–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folwarczny, M.; Otterbring, T.; Ares, G. Sustainable food choices as an impression management strategy. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2023, 49, 100969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenfeld, D.L.; Burrow, A.L. The unified model of vegetarian identity: A conceptual framework for understanding plant-based food choices. Appetite 2017, 112, 78–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nwobodo, S.; Weissmann, M.A. Common traits in online shopping behavior: A study of different generational cohorts. Glob. Bus. Organ. Excell. 2024, 43, 46–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, R.; Holbrook, M. Consumer Value: A Framework for Analysis and Research; Routledge: Oxford, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Sheth, J.N.; Newman, B.I.; Gross, B.L. Why we buy what we buy: A theory of consumption values. J. Bus. Res. 1991, 22, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodds, W.B.; Monroe, K.B.; Grewal, D. Effects of price, brand, and store information on buyers’ product evaluations. J. Mark. Res. 1991, 28, 307–319. [Google Scholar]

- Blut, M.; Chaney, D.; Lunardo, R.; Mencarelli, R.; Grewal, D. Customer perceived value: A comprehensive meta-analysis. J. Serv. Res. 2024, 27, 501–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holbrook, M.B. Consumption experience, customer value, and subjective personal introspection: An illustrative photographic essay. J. Bus. Res. 2006, 59, 714–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallarza, M.; Gil-Saura, I.; Arteaga-Moreno, F. Bridging service dominant logic and the concept of customer value through higher order indexes: Insights from hospitality experiences. Eur. J. Tour. Res. 2023, 35, 3510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overby, J.W.; Lee, E.-J. The effects of utilitarian and hedonic online shopping value on consumer preference and intentions. J. Bus. Res. 2006, 59, 1160–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quach, S.; Roberts, R.E.; Dang, S.; Zuo, A.; Thaichon, P. The interaction between values and self-identity on fairtrade consumption: The value-identity-behavior model. Appetite 2025, 206, 107826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwartz, S.H. Universals in the content and structure of values: Theoretical advances and empirical tests in 20 countries. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1992; Volume 25, pp. 1–65. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, M.T.; Lu, P.; Parrella, J.A.; Leggette, H.R. Consumer acceptance toward functional foods: A scoping review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackel, L.M.; Coppin, G.; Wohl, M.J.; Van Bavel, J.J. From groups to grits: Social identity shapes evaluations of food pleasantness. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2018, 74, 270–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, K.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, L.; Li, C. Self-transcendence values influence meaningful sports consumption behavior: The chain mediator of team identification and eudaimonic motivation. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamczyk, G.; Capetillo-Ponce, J.; Szczygielski, D. Links between types of value orientations and consumer behaviours. An empirical study. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0264185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruwys, T.; Bevelander, K.E.; Hermans, R.C. Social modeling of eating: A review of when and why social influence affects food intake and choice. Appetite 2015, 86, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, S.; Huang, L.; Roth, M.S.; Madden, T.J. The influence of social media interactions on consumer–brand relationships: A three-country study of brand perceptions and marketing behaviors. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2016, 33, 27–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, X.J.; Radzol, A.; Cheah, J.; Wong, M.W. The impact of social media influencers on purchase intention and the mediation effect of customer attitude. Asian J. Bus. Res. 2017, 7, 19–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilro, R.G.; Loureiro, S.M.C.; Guerreiro, J. Exploring online customer engagement with hospitality products and its relationship with involvement, emotional states, experience and brand advocacy. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2019, 28, 147–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, C.; Xie, Q. Something social, something entertaining? How digital content marketing augments consumer experience and brand loyalty. Int. J. Advert. 2021, 40, 376–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaupp, L.C.; Bélanger, F. The value of social media for small businesses. J. Inf. Syst. 2014, 28, 187–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Suárez, M.; Martínez-Ruiz, M.P.; Martínez-Caraballo, N. Consumer-brand relationships under the marketing 3.0 paradigm: A literature review. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dessart, L. Social media engagement: A model of antecedents and relational outcomes. J. Mark. Manag. 2017, 33, 375–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, J.U.; Hollebeek, L.D.; Rahman, Z.; Khan, I.; Rasool, A. Customer engagement in the service context: An empirical investigation of the construct, its antecedents and consequences. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2019, 50, 277–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, J.; Kumar, V. Drivers of brand community engagement. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 54, 101949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronin, J.J., Jr.; Brady, M.K.; Hult, G.T.M. Assessing the effects of quality, value, and customer satisfaction on consumer behavioral intentions in service environments. J. Retail. 2000, 76, 193–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annunziata, A.; Vecchio, R. Functional foods development in the European market: A consumer perspective. J. Funct. Foods 2011, 3, 223–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, H.; Liu, S. Sociopsychological determinants of functional foods consumption in China: Based on the theory of the planned behaviour expansion model. Front. Nutr. 2025, 12, 1624390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okazaki, S.; Mendez, F. Perceived ubiquity in mobile services. J. Interact. Mark. 2013, 27, 98–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourazad, N.; Stocchi, L.; Michaelidou, N.; Pare, V. What (really) drives consumer love for traditional luxury brands? The joint effects of brand qualities on brand love. J. Strateg. Mark. 2024, 32, 422–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, P.; Rosendo-Rios, V. Intra and inter-country comparative effects of symbolic motivations on luxury purchase intentions in emerging markets. Int. Bus. Rev. 2021, 30, 101768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega, D.L.; Sun, J.; Lin, W. Identity labels as an instrument to reduce meat demand and encourage consumption of plant based and cultured meat alternatives in China. Food Policy 2022, 111, 102307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osmanova, I.; Ozerden, S.; Dalal, B.; Ibrahim, B. Examining the relationship between brand symbolism and brand evangelism through consumer brand identification: Evidence from Starbucks coffee brand. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, J.; Pang, J.; Dong, X. More gain, more give? The impact of brand community value on users’ value co-creation. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 74, 103389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaheen, R.; Aljarah, A.; Ibrahim, B.; Hazzam, J.; Ghasemi, M. Make it real, make it useful! The impact of AR social experience on brand positivity and information sharing. Br. Food J. 2024, 126, 3157–3176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, C.; Ling, S.; Cho, D. How social identity affects green food purchase intention: The serial mediation effect of green perceived value and psychological distance. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhuri, N.; Gupta, G.; Sharma, S.K. Outpacing choices: Examining dynamic consumer preferences across multi-generational information-intensive digital products. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2024, 77, 102784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Israfilzade, K.; Guliyeva, N. Cross-Generational Impacts of Digital Remarketing: An Examination of Purchasing Behaviours among Generation Z and Generation Y. Futur. Econ. Law 2023, 3, 96–117. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Xu, A.; Tang, D.; Zheng, M. Divergence and convergence: A cross-generational study on local food consumption. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 13463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, S.; Wai, P.P.; Koirala, P.; Bromage, S.; Nirmal, N.P.; Pandiselvam, R.; Nor-Khaizura, M.A.R.; Mehta, N.K. Food product quality, environmental and personal characteristics affecting consumer perception toward food. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2023, 7, 1222760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savelli, E.; Murmura, F. The intention to consume healthy food among older Gen-Z: Examining antecedents and mediators. Food Qual. Prefer. 2023, 105, 104788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raptou, E.; Tsiami, A.; Negro, G.; Ghuriani, V.; Baweja, P.; Smaoui, S.; Varzakas, T. Gen Z’s willingness to adopt plant-based diets: Empirical evidence from Greece, India, and the UK. Foods 2024, 13, 2076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tirocchi, S. Generation Z, values, and media: From influencers to BeReal, between visibility and authenticity. Front. Sociol. 2024, 8, 1304093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, K.-Y.; Ashraf, A.R.; Thongpapanl, N.T.; Nguyen, O. Influence of social augmented reality app usage on customer relationships and continuance intention: The role of shared social experience. J. Bus. Res. 2023, 166, 114092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweeney, J.C.; Soutar, G.N. Consumer perceived value: The development of a multiple item scale. J. Retail. 2001, 77, 203–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holbrook, M.B.; Hirschman, E.C. The experiential aspects of consumption: Consumer fantasies, feelings, and fun. J. Consum. Res. 1982, 9, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiedmann, K.-P.; Hennigs, N.; Siebels, A. Measuring consumers’ luxury value perception: A cross-cultural framework. Acad. Mark. Sci. Rev. 2007, 2007, 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Gallarza, M.G.; Gil-Saura, I.; Holbrook, M.B. The value of value: Further excursions on the meaning and role of customer value. J. Consum. Behav. 2011, 10, 179–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, J.; Costa, C.; Oliveira, T.; Gonçalves, R.; Branco, F. How smartphone advertising influences consumers’ purchase intention. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 94, 378–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chetioui, Y.; Benlafqih, H.; Lebdaoui, H. How fashion influencers contribute to consumers’ purchase intention. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. Int. J. 2020, 24, 361–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.-Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis: Pearson New International Edition PDF eBook; Pearson: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y. On the evaluation of structural equation models. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1988, 16, 74–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM); SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wetzels, M.; Odekerken-Schröder, G.; Van Oppen, C. Using PLS path modeling for assessing hierarchical construct models: Guidelines and empirical illustration. MIS Q. 2009, 33, 177–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’brien, R.M. A caution regarding rules of thumb for variance inflation factors. Qual. Quant. 2007, 41, 673–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. Gain more insight from your PLS-SEM results: The importance-performance map analysis. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2016, 116, 1865–1886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiss, P.C. Building better causal theories: A fuzzy set approach to typologies in organization research. Acad. Manag. J. 2011, 54, 393–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, C.Q.; Wagemann, C. Set-Theoretic Methods for the Social Sciences: A Guide to Qualitative Comparative Analysis; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kraus, S.; Ribeiro-Soriano, D.; Schüssler, M. Fuzzy-set qualitative comparative analysis (fsQCA) in entrepreneurship and innovation research–the rise of a method. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2018, 14, 15–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodside, A.G. The Complexity Turn: Cultural, Management, and Marketing Applications; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, S.H.; Cieciuch, J. Measuring the refined theory of individual values in 49 cultural groups: Psychometrics of the revised portrait value questionnaire. Assessment 2022, 29, 1005–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bech-Larsen, T.; Grunert, K.G. The perceived healthiness of functional foods: A conjoint study of Danish, Finnish and American consumers’ perception of functional foods. Appetite 2003, 40, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banna, J.C.; Gilliland, B.; Keefe, M.; Zheng, D. Cross-cultural comparison of perspectives on healthy eating among Chinese and American undergraduate students. BMC Public Health 2016, 16, 1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halicka, E.; Kaczorowska, J.; Rejman, K.; Plichta, M. Investigating the Consumer Choices of Gen Z: A Sustainable Food System Perspective. Nutrients 2025, 17, 591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fathin, F.F.; Sosianika, A.; Amalia, F.A.; Kania, R. The role of health consciousness and trust on Gen Y and Gen Z intention to purchase functional beverages. J. Consum. Sci. 2023, 8, 360–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Acunto, D.; Filieri, R.; Okumus, F. The Gen Z attitude-behavior gap in sustainability-framed eWOM: A generational cohort theory perspective. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2025, 129, 104194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, J.M.; Gomes, S.; Suchek, N.; Nogueira, S. The hidden reasons behind generation Z’s green choices. Discov. Sustain. 2024, 5, 520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Construct | Items | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Functional Value (FV) | FV1: I believe this snack helps me meet specific health needs (e.g., digestion, immunity). FV2: The low-sugar/low-salt/low-fat features of this snack fit my healthy diet standards. FV3: I trust the functional claims of this snack because they are supported by authoritative certifications (e.g., health food labels). FV4: Compared with ordinary snacks, this product has superior health attributes. | Sweeney and Soutar [61]; Savelli and Murmura [57] |

| Hedonic Value (HV) | HV1: Eating this snack gives me a pleasurable sensory experience (taste, flavor, etc.). HV2: I enjoy the immediate pleasure this snack brings. HV3: The color, aroma, or texture of this snack makes me feel relaxed and satisfied. HV4: Even as an ordinary snack, I would choose it because of its good taste. | Holbrook and Hirschman [62]; Thakur, Sharma, Mehta and Torrico [4] |

| Symbolic Value (SV) | SV1: Eating this snack makes me feel aligned with the lifestyle I aspire to. SV2: The values embodied by this snack resonate with me. SV3: Choosing this snack makes me feel that I belong to a certain group. SV4: The style of this snack matches the personal image I want to project. | Wiedmann, Hennigs and Siebels [63] |

| Social Interaction Value (SIV) | SIV1: I think this snack is suitable for sharing at gatherings with friends. SIV2: Eating this snack with friends increases the fun. SIV3: I consider this snack a good choice for entertaining guests. SIV4: Sharing this snack with others enhances my social experience. | Gallarza, Gil–Saura and Holbrook [64]; Wang, Ashraf, Thongpapanl and Nguyen [60] |

| Consumption Intention (CI) | CI1: I plan to purchase this snack in the future. CI2: I would prioritize this snack over other similar products. CI3: I am willing to pay a higher price for this snack compared with ordinary snacks. CI4: I am willing to recommend this snack to others. | Martins, Costa, Oliveira, Gonçalves and Branco [65]; Chetioui, Benlafqih and Lebdaoui [66] |

| Sample | Category | Number | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Male | 382 | 47.3 |

| Female | 425 | 52.7 | |

| Generation | Generation Y (1980–1994) | 357 | 44.2 |

| Generation Z (1995–2007) | 450 | 55.8 | |

| Education | Secondary vocational school, high school and below | 155 | 19.2 |

| Junior college | 240 | 29.7 | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 355 | 44.0 | |

| Master’s degrees and above | 57 | 7.1 | |

| Monthly disposable income | 1000 and below | 311 | 38.5 |

| 1001–3000 yuan | 242 | 30.0 | |

| 3001–6000 yuan | 182 | 22.5 | |

| 6000 yuan and above | 72 | 9.0 |

| Constructs | Items | Loadings | α | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FV | FV 1 | 0.868 | 0.843 | 0.895 | 0.681 |

| FV 2 | 0.773 | ||||

| FV 3 | 0.792 | ||||

| FV 4 | 0.865 | ||||

| HV | HV 1 | 0.799 | 0.811 | 0.874 | 0.634 |

| HV 2 | 0.771 | ||||

| HV 3 | 0.813 | ||||

| HV 4 | 0.801 | ||||

| SV | SV 1 | 0.895 | 0.870 | 0.912 | 0.721 |

| SV 2 | 0.781 | ||||

| SV 3 | 0.840 | ||||

| SV 4 | 0.875 | ||||

| SIV | SIV 1 | 0.876 | 0.862 | 0.906 | 0.708 |

| SIV 2 | 0.842 | ||||

| SIV 3 | 0.850 | ||||

| SIV 4 | 0.795 | ||||

| CI | CI 1 | 0.896 | 0.892 | 0.925 | 0.756 |

| CI 2 | 0.808 | ||||

| CI 3 | 0.889 | ||||

| CI 4 | 0.883 |

| FV | HV | SV | SIV | Gen | CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FV | ||||||

| HV | 0.643 | |||||

| SV | 0.712 | 0.574 | ||||

| SIV | 0.680 | 0.717 | 0.737 | |||

| Gen | 0.145 | 0.049 | 0.100 | 0.063 | ||

| CI | 0.804 | 0.706 | 0.729 | 0.791 | 0.070 |

| FV | HV | SV | SIV | Gen | CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FV | 0.825 | |||||

| HV | 0.553 | 0.796 | ||||

| SV | 0.615 | 0.503 | 0.849 | |||

| SIV | 0.581 | 0.611 | 0.643 | 0.841 | ||

| Gen | −0.137 | −0.007 | −0.097 | −0.044 | 1 | |

| CI | 0.702 | 0.623 | 0.645 | 0.695 | −0.054 | 0.870 |

| Constructs | R2 | Q2 | GOF |

|---|---|---|---|

| SV | 0.416 | 0.411 | 0.614 |

| SIV | 0.540 | 0.454 | |

| CI | 0.659 | 0.563 |

| Hypothesis | Path | Std Beta | p-Value | VIF | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | FV→SV | 0.485 | <0.001 | 1.439 | Support |

| H2 | FV→SIV | 0.171 | 0.001 | 1.842 | Support |

| H3 | HV→SV | 0.235 | <0.001 | 1.439 | Support |

| H4 | HV→SIV | 0.330 | <0.001 | 1.534 | Support |

| H5 | SV→SIV | 0.372 | <0.001 | 1.713 | Support |

| H6 | FV→CI | 0.327 | <0.001 | 5.125 | Support |

| H7 | HV→CI | 0.209 | 0.002 | 4.096 | Support |

| H8 | SV→CI | 0.282 | <0.001 | 5.022 | Support |

| H9 | SIV→CI | 0.169 | 0.027 | 5.097 | Support |

| H10 | Gen × FV→CI | 0.031 | 0.729 | 4.581 | No Support |

| H11 | Gen × HV→CI | −0.066 | 0.412 | 3.981 | No Support |

| H12 | Gen × SV→CI | −0.196 | 0.026 | 4.964 | Support |

| H13 | Gen × SIV→CI | 0.203 | 0.025 | 4.986 | Support |

| Variable | High CI | Not High CI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Consistency | Coverage | Consistency | Coverage | |

| FV | 0.732 | 0.878 | 0.424 | 0.479 |

| ~FV | 0.567 | 0.511 | 0.892 | 0.758 |

| HV | 0.769 | 0.840 | 0.528 | 0.543 |

| ~HV | 0.581 | 0.567 | 0.844 | 0.775 |

| SV | 0.774 | 0.862 | 0.492 | 0.516 |

| ~SV | 0.565 | 0.542 | 0.868 | 0.784 |

| SIV | 0.818 | 0.850 | 0.542 | 0.531 |

| ~SIV | 0.549 | 0.560 | 0.847 | 0.814 |

| Variable | High CI | Not High CI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Consistency | Coverage | Consistency | Coverage | |

| FV | 0.866 | 0.764 | 0.492 | 0.504 |

| ~FV | 0.438 | 0.426 | 0.770 | 0.870 |

| HV | 0.788 | 0.721 | 0.509 | 0.542 |

| ~HV | 0.499 | 0.467 | 0.738 | 0.802 |

| SV | 0.800 | 0.754 | 0.511 | 0.560 |

| ~SV | 0.533 | 0.484 | 0.776 | 0.818 |

| SIV | 0.838 | 0.741 | 0.527 | 0.541 |

| ~SIV | 0.482 | 0.467 | 0.748 | 0.843 |

| Configuration | Generation Y | Generation Z | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High CI | Not High CI | High CI | Not High CI | |||

| M1 | M2 | M1 | M1 | M1 | M2 | |

| FV | ⬤ | ⬤ | ⨂ | ⬤ | ⊗ | ⊗ |

| HV | ⬤ | ⊗ | ⬤ | ⨂ | ● | |

| SV | ⬤ | ⊗ | ⬤ | ⨂ | ● | |

| SIV | ⬤ | ● | ⊗ | ⬤ | ⊗ | ⊗ |

| Consistency | 0.941 | 0.950 | 0.938 | 0.897 | 0.973 | 0.949 |

| Raw coverage | 0.562 | 0.577 | 0.698 | 0.588 | 0.521 | 0.268 |

| unique coverage | 0.051 | 0.066 | 0.698 | 0.588 | 0.304 | 0.051 |

| Solution coverage | 0.628 | 0.698 | 0.588 | 0.572 | ||

| Solution consistency | 0.939 | 0.938 | 0.897 | 0.961 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, X.; Zhang, X.-E.; Yin, J.; Chen, J.; Lin, H. How Does Perceived Value Influence Functional Snack Consumption Intention? An Empirical Analysis Based on Generational Differences. Foods 2025, 14, 3879. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14223879

Chen X, Zhang X-E, Yin J, Chen J, Lin H. How Does Perceived Value Influence Functional Snack Consumption Intention? An Empirical Analysis Based on Generational Differences. Foods. 2025; 14(22):3879. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14223879

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Xinqiang, Xiu-E Zhang, Jin Yin, Jiangjie Chen, and Hongyan Lin. 2025. "How Does Perceived Value Influence Functional Snack Consumption Intention? An Empirical Analysis Based on Generational Differences" Foods 14, no. 22: 3879. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14223879

APA StyleChen, X., Zhang, X.-E., Yin, J., Chen, J., & Lin, H. (2025). How Does Perceived Value Influence Functional Snack Consumption Intention? An Empirical Analysis Based on Generational Differences. Foods, 14(22), 3879. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14223879