Assessing the Alignment Between Naturally Adaptive Grain Crop Planting Patterns and Staple Food Security in China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection

2.1.1. Grain Crop Sample Data

2.1.2. Environmental Data

2.2. Data Preprocessing

2.2.1. Identification of Grain Crops’ Planting Sites

2.2.2. Selection of Environment Variables

2.3. Application of the MaxEnt Model

2.4. Measurement of Grain Crops’ Diversity

2.5. Calculation of Grain Crops’ Nutrient

| Nutritional Index | Wheat | Rice | Maize | Soybean | Tuber | Potato | Sweet Potato | Cassava |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy (KJ/100 g) | 1416 | 1457 | 1453 | 1631 | 367 | 343 | 260 | 498 |

| Protein (g/100 g) | 11.9 | 8.7 | 7.9 | 35.0 | 1.8 | 2.6 | 0.7 | 2.1 |

| Fat (g/100 g) | 1.3 | 3.8 | 0.9 | 16.0 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.3 |

| CHO (g/100 g) | 75.2 | 73.0 | 77.2 | 34.2 | 20.3 | 17.8 | 15.3 | 27.8 |

| Edible (per cent) | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 94 | 94 | 90 | 99 |

| Moisture content (g/100 g) | 10.0 | 13.2 | 13.3 | 10.2 | 77.0 | 78.6 | 83.4 | 69.0 |

3. Results

3.1. Suitable Planting Pattern of Grain Crop

3.1.1. Model Performance

3.1.2. Influence of Environmental Variables on Planting Suitability Range

3.2. Comparison of Actual and Suitable Planting Patterns

3.2.1. Analysis of Grain Crops’ Planting Layout

3.2.2. Analysis of Grain Crops’ Planting Structure

3.3. Assessment of Differences Between Actual and Suitable Grain Crops’ Planting Effectiveness

3.3.1. Analysis of Grain Crops’ Planting Diversity

3.3.2. Analysis of Grain Crops’ Production

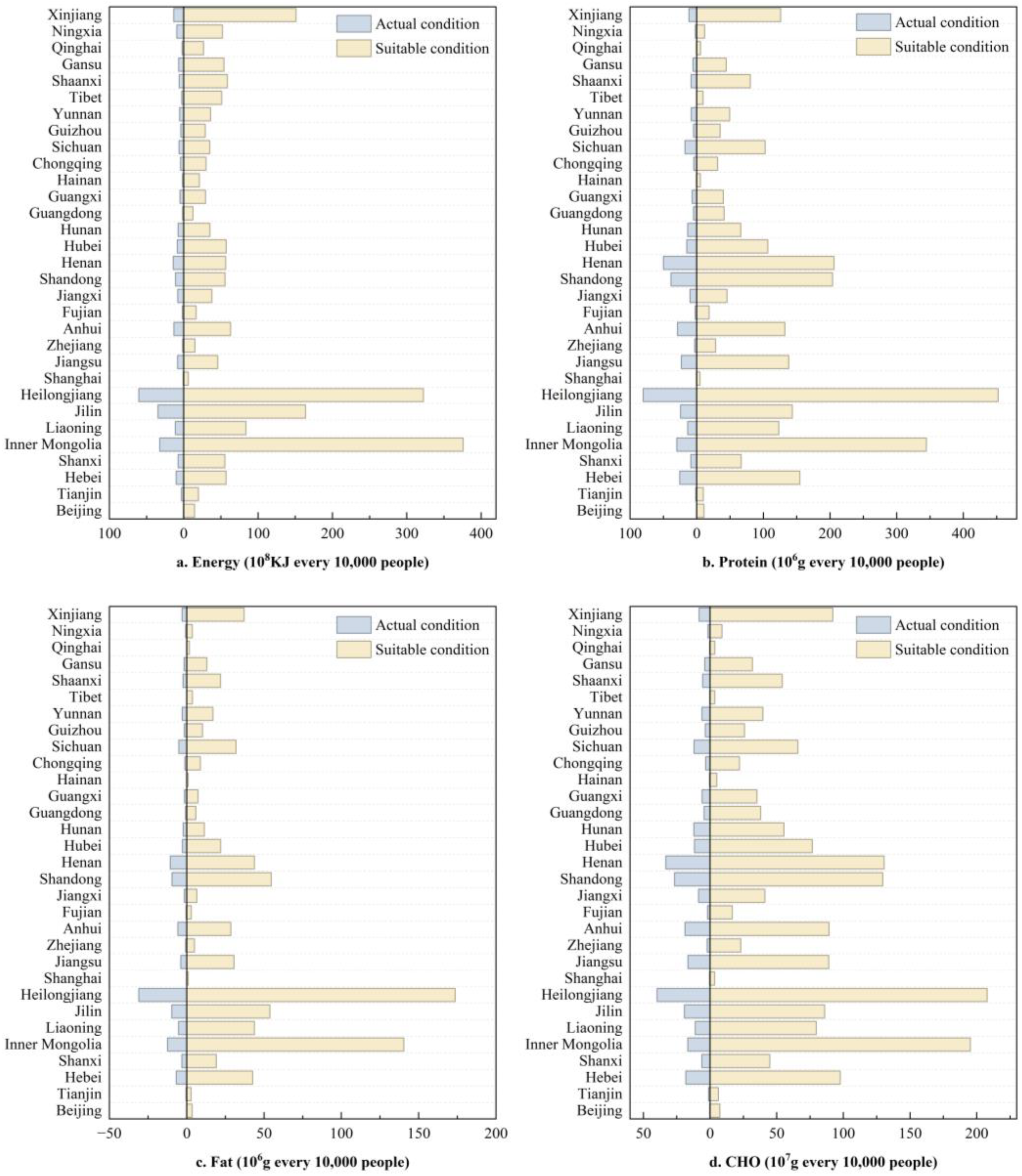

3.3.3. Analysis of Grain Crops’ Nutrient Supply

4. Discussion

4.1. Disparities Between Potential Suitability and Actual Planting Patterns

4.2. Policy Suggestions

4.3. Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| NCP | Northeast China Plain |

| NAS | Northern Arid and Semiarid Region |

| HHHP | Huang-Huai-Hai Plain |

| LP | Loess Plateau |

| QTP | Qinghai–Tibet Plateau |

| SBS | Sichuan Basin and Surrounding Region |

| MLYP | Middle-Lower Yangtze Plain |

| YGP | Yunnan-Guizhou Plateau |

| SC | Southern China |

| SDI | The Simpson Diversity Index, measuring the planting diversity of regional grain crops |

| CHO | carbohydrate |

| AUC | Area Under the Curve |

References

- Godfray, H.C.J.; Beddington, J.R.; Crute, I.R.; Haddad, L.; Lawrence, D.; Muir, J.F.; Pretty, J.; Robinson, S.; Thomas, S.M.; Toulmin, C. Food Security: The Challenge of Feeding 9 Billion People. Science 2010, 327, 812–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, J.; Zhang, Z.; Zhao, C.; Liu, Z.; Guo, E.; Zhang, T.; Chen, J.; Olesen, J.E.; Liu, K.; Harrison, M.T.; et al. Dissecting the Vital Role of Dietary Changes in Food Security Assessment under Climate Change. Commun. Earth Environ. 2024, 5, 440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laborde, D.; Martin, W.; Swinnen, J.; Vos, R. COVID-19 Risks to Global Food Security. Science 2020, 369, 500–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Tan, Q.; Chen, J.; Pan, T.; Penuelas, J.; Zhang, J.; Ge, Q. Dietary Transition Determining the Tradeoff between Global Food Security and Sustainable Development Goals Varied in Regions. Earth’s Future 2022, 10, e2021EF002354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willett, W.; Rockström, J.; Loken, B.; Springmann, M.; Lang, T.; Vermeulen, S.; Garnett, T.; Tilman, D.; DeClerck, F.; Wood, A.; et al. Food in the Anthropocene: The EAT–Lancet Commission on Healthy Diets from Sustainable Food Systems. Lancet 2019, 393, 447–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, D.K.; Sloat, L.L.; Garcia, A.S.; Davis, K.F.; Ali, T.; Xie, W. Crop Harvests for Direct Food Use Insufficient to Meet the UN’s Food Security Goal. Nat. Food 2022, 3, 367–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, W.; Su, M.; Cai, Y.; Rong, Q.; Xu, C.; Hu, Y.; Li, J.; Yu, S.; Chen, D.; Liu, Z.; et al. Merits of Dietary Patterns for China’s Future Food Security Satisfying Socioeconomic Development and Climate Change Adaptation. iScience 2025, 28, 112859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Li, Y.; Cui, J.; Yu, B. Multidimensional Deconstruction and Workable Solutions for Addressing China’s Food Security Issues: From the Perspective of Sustainable Diets. Land Use Policy 2025, 148, 107401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhuri, I.; Pal, S.C. Challenges and Potential Pathways towards Sustainable Agriculture Crop Production: A Systematic Review to Achieve Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Soil Tillage Res. 2025, 248, 106442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, B.; Jian, Z.; Yang, P.; Tang, Z.; Zhu, X.; Duan, M.; Yu, Q.; Chen, X.; Zhang, M.; Tu, P.; et al. Unveiling Grain Production Patterns in China (2005–2020) towards Targeted Sustainable Intensification. Agric. Syst. 2024, 216, 103878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Nie, F.; Jia, X. Production Choices and Food Security: A Review of Studies Based on a Micro-Diversity Perspective. Foods 2024, 13, 771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sibhatu, K.T.; Krishna, V.V.; Qaim, M. Production Diversity and Dietary Diversity in Smallholder Farm Households. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 10657–10662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arimond, M.; Wiesmann, D.; Becquey, E.; Carriquiry, A.; Daniels, M.C.; Deitchler, M.; Fanou-Fogny, N.; Joseph, M.L.; Kennedy, G.; Martin-Prevel, Y.; et al. Simple Food Group Diversity Indicators Predict Micronutrient Adequacy of Women’s Diets in 5 Diverse, Resource-Poor Settings. J. Nutr. 2010, 140, 2059S–2069S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Jiao, L.; Li, C.; Deng, Z.; Wang, Z.; Jia, Q.; Lian, X.; Liu, Y.; Hu, Y. Global Environmental Impacts of Food System from Regional Shock: Russia-Ukraine War as an Example. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Yang, H.; Chen, Y.; Chiu, Y.; Pang, Q.; Sun, C.; Shi, Z. Assessing Water-Energy-Food Nexus Efficiency for Food Security Planning in China. Food Policy 2025, 134, 102902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Wu, H.; Li, J.; Xiao, Q.; Li, J. Assessment of the Effect of the Main Grain-Producing Areas Policy on China’s Food Security. Foods 2024, 13, 654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Wang, G.; Cai, W.; Che, X.; Zhou, W.; Zhang, C.; Zeng, J. Spatiotemporal Mismatch of Global Grain Production and Farmland and Its Influencing Factors. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2023, 194, 107008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, S.; Zhu, Y.; Fang, X. Big Food Vision and Food Security in China. Agric. Rural. Stud. 2023, 1, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddad, L.; Hawkes, C.; Webb, P.; Thomas, S.; Beddington, J.; Waage, J.; Flynn, D. A New Global Research Agenda for Food. Nature 2016, 540, 30–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrero, M.; Thornton, P.K.; Power, B.; Bogard, J.R.; Remans, R.; Fritz, S.; Gerber, J.S.; Nelson, G.; See, L.; Waha, K.; et al. Farming and the Geography of Nutrient Production for Human Use: A Transdisciplinary Analysis. Lancet Planet. Health 2017, 1, e33–e42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, S.; Yosef, S.; Pandya-Lorch, R. Linking Agriculture to Nutrition: The Evolution of Policy. CAER 2020, 12, 595–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasa Rao, C.; Kareemulla, K.; Krishnan, P.; Murthy, G.R.K.; Ramesh, P.; Ananthan, P.S.; Joshi, P.K. Agro-Ecosystem Based Sustainability Indicators for Climate Re silient Agriculture in India: A Conceptual Framework. Ecol. Indic. 2019, 105, 621–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolinska, A.; Hassenforder, E.; Loboguerrero, A.M.; Sultan, B.; Bossuet, J.; Cottenceau, J.; Bonatti, M.; Hellin, J.; Mekki, I.; Drogoul, A.; et al. Co-Production Opportunities Seized and Missed in Decision-Support Frameworks for Climate-Change Adaptation in Agriculture—How Do We Practice the “Best Practice”? Agric. Syst. 2023, 212, 103775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagbemi, F.; Oke, D.F.; Fajingbesi, A. Climate-Resilient Development: An Approach to Sustainable Food Production in Sub-Saharan Africa. Future Foods 2023, 7, 100216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobell, D.B.; Burke, M.B.; Tebaldi, C.; Mastrandrea, M.D.; Falcon, W.P.; Naylor, R.L. Prioritizing Climate Change Adaptation Needs for Food Security in 2030. Science 2008, 319, 607–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acevedo, M.; Pixley, K.; Zinyengere, N.; Meng, S.; Tufan, H.; Cichy, K.; Bizikova, L.; Isaacs, K.; Ghezzi-Kopel, K.; Porciello, J. A Scoping Review of Adoption of Climate-Resilient Crops by Small-Scale Producers in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. Nat. Plants 2020, 6, 1231–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tabe-Ojong, M.P.J.; Lokossou, J.C.; Gebrekidan, B.; Affognon, H.D. Adoption of Climate-Resilient Groundnut Varieties Increases Agricultural Production, Consumption, and Smallholder Commercialization in West Africa. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 5175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhankher, O.P.; Foyer, C.H. Climate Resilient Crops for Improving Global Food Security and Safety. Plant Cell Environ. 2018, 41, 877–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, L.; Wang, G.; Wang, E.; Liu, S.; Chang, J.; Zhang, P.; Zhou, H.; Wei, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhu, Y.; et al. Spatiotemporal Co-Optimization of Agricultural Management Practices towards Climate-Smart Crop Production. Nat. Food 2024, 5, 59–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Singh, S.; Schillinger, W.F.; Neely, H.; Cappellazzi, S.B.; Norris, C. Does Increased Cropping Intensity Translate into Better Soil Health in Dryland Wheat Systems? Appl. Soil Ecol. 2024, 204, 105728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, S.; Zhao, J.; Wang, C.; Feng, Y.; Zhao, M.; Shi, X.; Chen, F.; Chu, Q. Planting Date Adjustment and Varietal Replacement Can Effectively Adapt to Climate Warming in China Southern Rice Area. Agric. Syst. 2025, 226, 104330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Z.; Zhao, J.; Zhuang, M.; Liu, Z.; Zhao, C.; Pullens, J.W.M.; Liu, K.; Harrison, M.T.; Yang, X. Climate-Adaptive Crop Distribution Can Feed Food Demand, Improve Water Scarcity, and Reduce Greenhouse Gas Emissions. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 944, 173819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, W.; Ma, G.; Wang, R.; Scherer, L.; He, P.; Xia, L.; Zhu, Y.; Bi, J.; Liu, B. Climate Adaptation through Crop Migration Requires a Nexus Perspective for Environmental Sustainability in the North China Plain. Nat. Food 2024, 5, 569–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, S.; Fang, Z.; van Riper, C.; He, W.; Li, X.; Zhang, F.; Wang, T.; Cheng, C.; Zhou, Q.; Huang, Z.; et al. Ensuring China’s Food Security in a Geographical Shift of Its Grain Production: Driving Factors, Threats, and Solutions. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2024, 210, 107845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, W.; Wang, H.; Luo, L.; Shi, Y.; Sui, Y.; Wu, L.; Zhang, B.; Yu, Q. Spatiotemporal Impact of Cultivated Land Use Transition on Grain Production: Perspective of Interaction between Dominant and Recessive Transitions. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2026, 117, 108170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Xiao, R.; Zhang, Z.; Zhou, F.; Mo, F.; Xu, Z.; Tian, F.; Gao, Z.; Li, Y.; Zhu, P.; et al. Rising Disparities in Grain Self-Sufficiency across China: Provincial Divergence amidst Overall National Improvement. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2025, 114, 107942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, T.; Peng, S.; Liu, B.; Liu, Y.; Ding, Y. Planting Suitability of China’s Main Grain Crops under Future Climate Change. Field Crops Res. 2023, 302, 109112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; He, L.; Liu, Y.; Wang, S. Reallocating Crop Spatial Pattern Improves Agricultural Productivity and Irrigation Benefits without Reducing Yields. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2023, 25, 14155–14176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aramburu Merlos, F.; Hijmans, R.J. Potential, Attainable, and Current Levels of Global Crop Diversity. Environ. Res. Lett. 2022, 17, 044071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, Y. Spatial Shifts in Grain Production Increases in China and Implications for Food Security. Land Use Policy 2018, 74, 204–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, O.; Ran, J.; Huang, S.; Duan, J.; Reis, S.; Zhang, J.; Zhu, Y.-G.; Xu, J.; Gu, B. Managing Fragmented Croplands for Environmental and Economic Benefits in China. Nat. Food 2024, 5, 230–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; Xu, S.; Gu, B.; He, T.; Zhang, H.; Fang, K.; Xiao, W.; Ye, Y. Stabilizing Unstable Cropland towards Win-Win Sustainable Development Goals. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2024, 105, 107395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Z.-Z.; Duan, J.-J.; Liang, H.-Y.; Zhu, Z.-Y.; Feng, Y.-Z.; Wang, X. Spatial Optimization of Cropping Patterns of Staple Crops to Enhance Supply–Demand Balance in China. J. Rural. Stud. 2025, 120, 103869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Z.-Z.; Chang, S.; Zhao, G.-R.; Duan, J.-J.; Liang, H.-Y.; Zhu, Z.-Y.; Liu, S.-L.; Feng, Y.-Z.; Wang, X. Unlocking China’s Grain Yield Potential: Harnessing Technological and Spatial Synergies in Diverse Cropping Systems. Agric. Syst. 2025, 226, 104308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.; Lu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Tong, Z.; Xing, L.; Dou, C. Multifunctional Evaluation and Multiscenario Regulation of Non-Grain Farmlands from the Grain Security Perspective: Evidence from the Wuhan Metropolitan Area, China. Land Use Policy 2024, 146, 107322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Q.; You, L.; Wood-Sichra, U.; Ru, Y.; Joglekar, A.K.B.; Fritz, S.; Xiong, W.; Lu, M.; Wu, W.; Yang, P. A Cultivated Planet in 2010—Part 2: The Global Gridded Agricultural-Production Maps. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2020, 12, 3545–3572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei, E.E.; Webber, H.; Asseng, S.; Boote, K.; Durand, J.L.; Ewert, F.; Martre, P.; MacCarthy, D.S. Climate Change Impacts on Crop Yields. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2023, 4, 831–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Wang, Y.; Wang, L. Impact of Climate Change on Wheat Production in China. Eur. J. Agron. 2024, 153, 127066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.Z.; Yu, D.S.; Warner, E.D.; Pan, X.Z.; Petersen, G.W.; Gong, Z.G.; Weindorf, D.C. Soil Database of 1:1,000,000 Digital Soil Survey and Reference System of the Chinese Genetic Soil Classification System. Soil Surv. Horiz. 2004, 45, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Wang, C.; Shi, X.; Bo, X.; Li, S.; Shang, M.; Chen, F.; Chu, Q. Modeling Climatically Suitable Areas for Soybean and Their Shifts across China. Agric. Syst. 2021, 192, 103205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wu, K.; Hao, S.; Yue, Z.; Ran, Z.; Ma, J. Mapping Cropland Suitability in China Using Optimized MaxEnt Model. Field Crops Res. 2023, 302, 109064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaskulski, D.; Jaskulska, I. Diversity and Dominance of Crop Plantations in the Agroecosystems of the Kujawy and Pomorze Region in Poland. Acta Agric. Scand. Sect. B Soil Plant Sci. 2011, 61, 633–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Wang, X.; Huo, M.; Chen, F.; He, X. Changes of Cropping Structure Lead Diversity Decline in China during 1985–2015. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 346, 119051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Wu, K.; Song, W. Farmland quality classification based on productive ratio coefficient modified by crop nutrition equivalent unit. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2019, 35, 238–245. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, J.; Hou, F. Change traditional thinking about food grain production and use food equivalent in yield measurement. Acta Prataculturae Sin. 1999, 8, 55–75. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Li, T.; Long, H.; Zhang, Y.; Tu, S.; Ge, D.; Li, Y.; Hu, B. Analysis of the Spatial Mismatch of Grain Production and Farmland Resources in China Based on the Potential Crop Rotation System. Land Use Policy 2017, 60, 26–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drewnowski, A.; Dwyer, J.; King, J.C.; Weaver, C.M. A Proposed Nutrient Density Score That Includes Food Groups and Nutrients to Better Align with Dietary Guidance. Nutr. Rev. 2019, 77, 404–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drewnowski, A.; McKeown, N.; Kissock, K.; Beck, E.; Mejborn, H.; Vieux, F.; Smith, J.; Masset, G.; Seal, C.J. Perspective: Why Whole Grains Should Be Incorporated into Nutrient-Profile Models to Better Capture Nutrient Density. Adv. Nutr. 2021, 12, 600–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cardinaals, R.P.M.; Verly, E.; Jolliet, O.; Van Zanten, H.H.E.; Huppertz, T. The Complementarity of Nutrient Density and Disease Burden for Nutritional Life Cycle Assessment. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2024, 8, 1304752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y.; Liu, Y.; Xu, X.; Fan, Y.; He, L.; Wang, S. Improving Food System Sustainability: Grid-Scale Crop Layout Model Considering Resource-Environment-Economy-Nutrition. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 403, 136881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Chai, L. Trade-off between Human Health and Environmental Health in Global Diets. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2022, 182, 106336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; He, P.; Searchinger, T.D.; Chen, Y.; Springmann, M.; Zhou, M.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, L.; Mauzerall, D.L. Environmental and Human Health Trade-Offs in Potential Chinese Dietary Shifts. One Earth 2022, 5, 268–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mugiyo, H.; Chimonyo, V.G.P.; Sibanda, M.; Kunz, R.; Nhamo, L.; Masemola, C.R.; Dalin, C.; Modi, A.T.; Mabhaudhi, T. Multi-Criteria Suitability Analysis for Neglected and Underutilised Crop Species in South Africa. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0244734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadebe, S.T.; Modi, A.T.; Mabhaudhi, T. Assessing Suitability of Sorghum to Alleviate Sub-Saharan Nutritional Deficiencies through the Nutritional Water Productivity Index in Semi-Arid Regions. Foods 2021, 10, 385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getzner, M.; Bröthaler, J.; Neuhuber, T.; Dillinger, T.; Grinzinger, E.; Kanonier, A. Socio-Economic, Political and Fiscal Drivers of Unsustainable Local Land Use Decisions. Land Use Policy 2025, 153, 107537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, H.; Li, C.; Zhou, D.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, J. Peasant Households’ Land Use Decision-Making Analysis Using Social Network Analysis: A Case of Tantou Village, China. J. Rural. Stud. 2020, 80, 452–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Githinji, M.; Van Noordwijk, M.; Muthuri, C.; Speelman, E.N.; Kampen, J.; Hofstede, G.J. “You Never Farm Alone”: Farmer Land-Use Decisions Influenced by Social Relations. J. Rural. Stud. 2024, 108, 103284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Yin, Y.; Wang, Y.; Tian, X.; Ying, H.; Zhang, Q.; Xue, Y.; Oenema, O.; Li, S.; Zhou, F.; et al. Integrating Crop Redistribution and Improved Management towards Meeting China’s Food Demand with Lower Environmental Costs. Nat. Food 2022, 3, 1031–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Zhang, W. Spatiotemporal differentiation characteristics of cultivated land use from persprctive of growing food crops in major grain production areas in northeast China. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2020, 36, 1–8. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Sun, Y. Study on the functional transformation characteristics of farmland utilization in northeast China from the perspective of grain security. Res. Agric. Mod. 2024, 45, 210–220. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Wang, D.; Wang, J.; Wang, X.; Liu, X. National and Regional Food Security and Sustainable Development Againstthe Backdrop of Internationalization and Greenization. Strateg. Study CAE 2019, 21, 10–18. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Yang, H.; Duan, J. Suggestions for layout adjustment of China’s agricultural regions during Fifteenth Five-Year Plan period. Bull. Chin. Acad. Sci. 2024, 39, 663–675. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Zhang, X.; Zheng, D. Arid Northwest China Can Not Be Regarded as the Farmland Reserve Base. Arid Zone Res. 2010, 27, 1–5. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; He, G.; Zhao, Y.; Yao, Y.; He, F.; Li, H.; Wang, H. Potential for exploring cultivated land reserve resources under the influence of water supply project in Northern China. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2024, 40, 264–274. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Peng, X.; Dai, L.; Li, J.; Yan, Y.; Xu, Z.; Xu, Q.; Dou, Z.; Gao, H. Effects of Comprehensive Planting-breeding in Paddy Fields on Yield and Quality of Rice in the Middle and Lower Reaches of the Yangtze River. China Rice 2024, 28, 55–60. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, N.; Cai, D.; Zhao, P. Development of Potato Seed Industry and Targeted Poverty Alleviation in Plateau of China. Bull. Chin. Acad. Sci. 2020, 35, 1308–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, J.; Wang, W.; Chen, J.; Fu, H.; Shi, F. Scales and spatial distribution patterns of grain reserves on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Prog. Geogr. 2023, 42, 1869–1881. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, H.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, J.; Han, J.; Cheng, F.; Tao, F. Overcoming Wheat Yield Stagnation in China Depends More on Cultivar Improvements than Water and Fertilizer Management. Field Crops Res. 2025, 333, 110089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, H.; Zhang, Z.; Han, J.; Cheng, F.; Li, S.; Wu, H.; Mei, Q.; Song, J.; Wu, X.; Zhang, Z.; et al. Stagnating Rice Yields in China Need to Be Overcome by Cultivars and Management Improvements. Agric. Syst. 2024, 221, 104134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Crop Type | Based on All Environmental Variables | Based on Major Environmental Variables |

|---|---|---|

| Wheat | 0.9259 ± 0.0064 | 0.9172 ± 0.0071 |

| Maize | 0.8534 ± 0.0063 | 0.8425 ± 0.0066 |

| Rice | 0.9177 ± 0.0055 | 0.9056 ± 0.0057 |

| Soybean | 0.9354 ± 0.0075 | 0.9268 ± 0.0072 |

| Potato | 0.9370 ± 0.0108 | 0.9225 ± 0.0120 |

| Sweet potato | 0.9627 ± 0.0099 | 0.9498 ± 0.0083 |

| Cassava | 0.9932 ± 0.0032 | 0.9892 ± 0.0031 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, Z.; Hong, Q.; Sun, Y.; Hao, J.; Ai, D. Assessing the Alignment Between Naturally Adaptive Grain Crop Planting Patterns and Staple Food Security in China. Foods 2025, 14, 3870. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14223870

Zhang Z, Hong Q, Sun Y, Hao J, Ai D. Assessing the Alignment Between Naturally Adaptive Grain Crop Planting Patterns and Staple Food Security in China. Foods. 2025; 14(22):3870. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14223870

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Zonghan, Qiuchen Hong, Yihang Sun, Jinmin Hao, and Dong Ai. 2025. "Assessing the Alignment Between Naturally Adaptive Grain Crop Planting Patterns and Staple Food Security in China" Foods 14, no. 22: 3870. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14223870

APA StyleZhang, Z., Hong, Q., Sun, Y., Hao, J., & Ai, D. (2025). Assessing the Alignment Between Naturally Adaptive Grain Crop Planting Patterns and Staple Food Security in China. Foods, 14(22), 3870. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14223870