Exploring the Impact of Pitch-Coated Pottery on Wine Composition: Metabolomics Characterization of an Ancient Technique

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals

2.2. Pitch and Ceramic Vessel Production

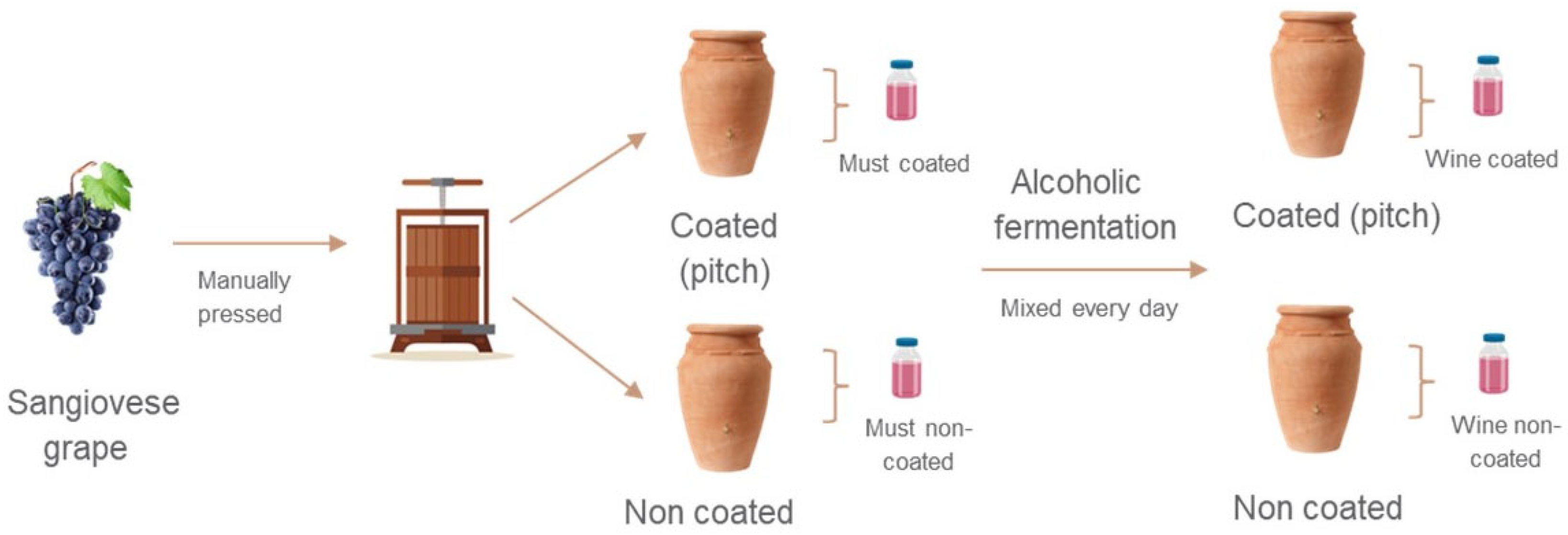

2.3. Winemaking Using Ceramic Vessels

2.4. Sample Preparation

2.5. Foodomics Profiling by UHPLC-Q-ToF-MS

2.5.1. Untargeted Analysis of Wine

2.5.2. Wine Anthocyanins

2.5.3. Pitch Lipidomics

2.6. Semi-Volatile Organic Compound Analysis by GC-MS

2.7. Anthocyanin Quantification by UPLC-DAD

2.8. Multivariate Date Analysis

2.9. Monovariate Statistics

3. Results and Discussion

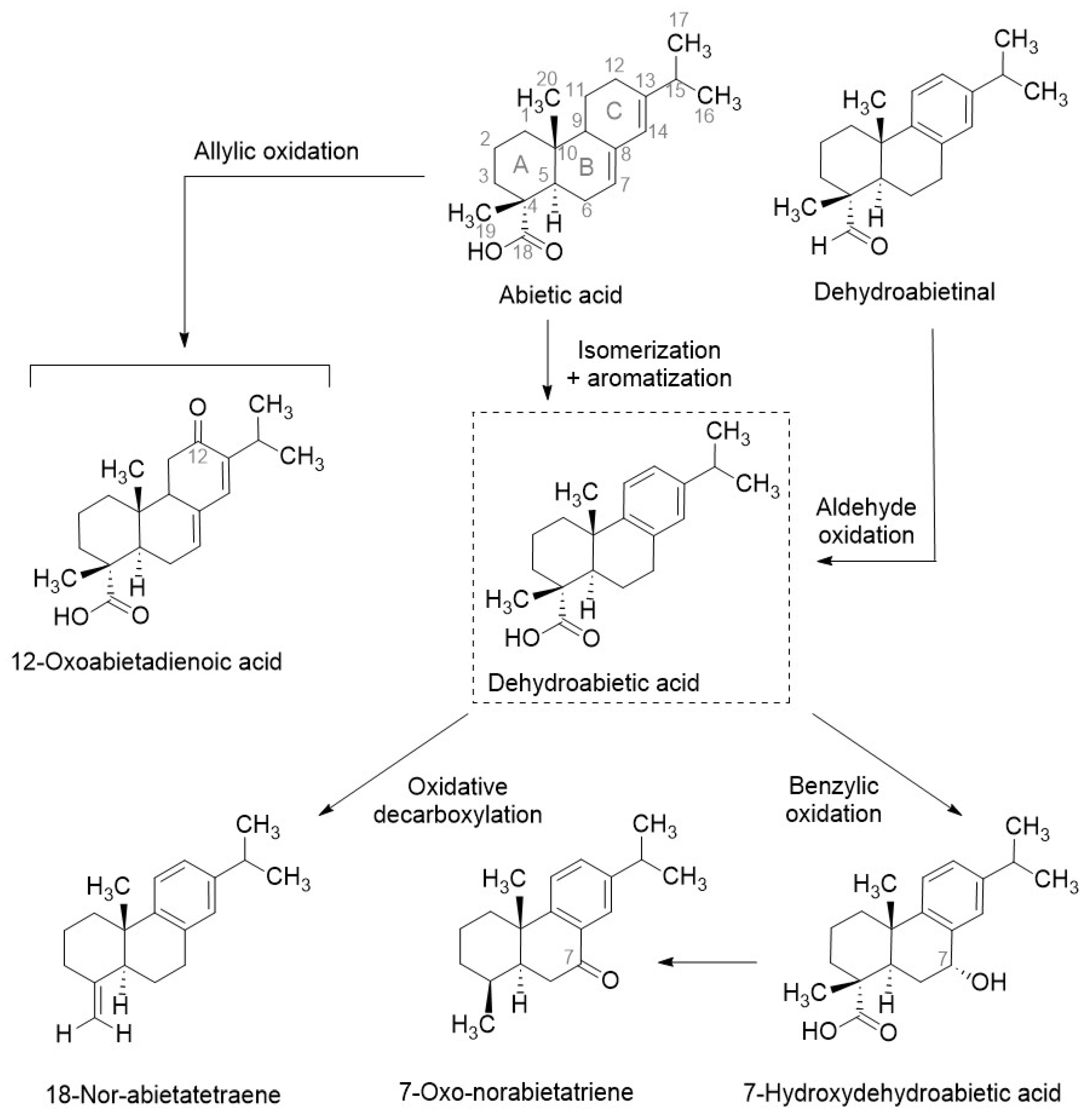

3.1. Pitch Characterisation

3.2. Effect of Pitch on Winemaking

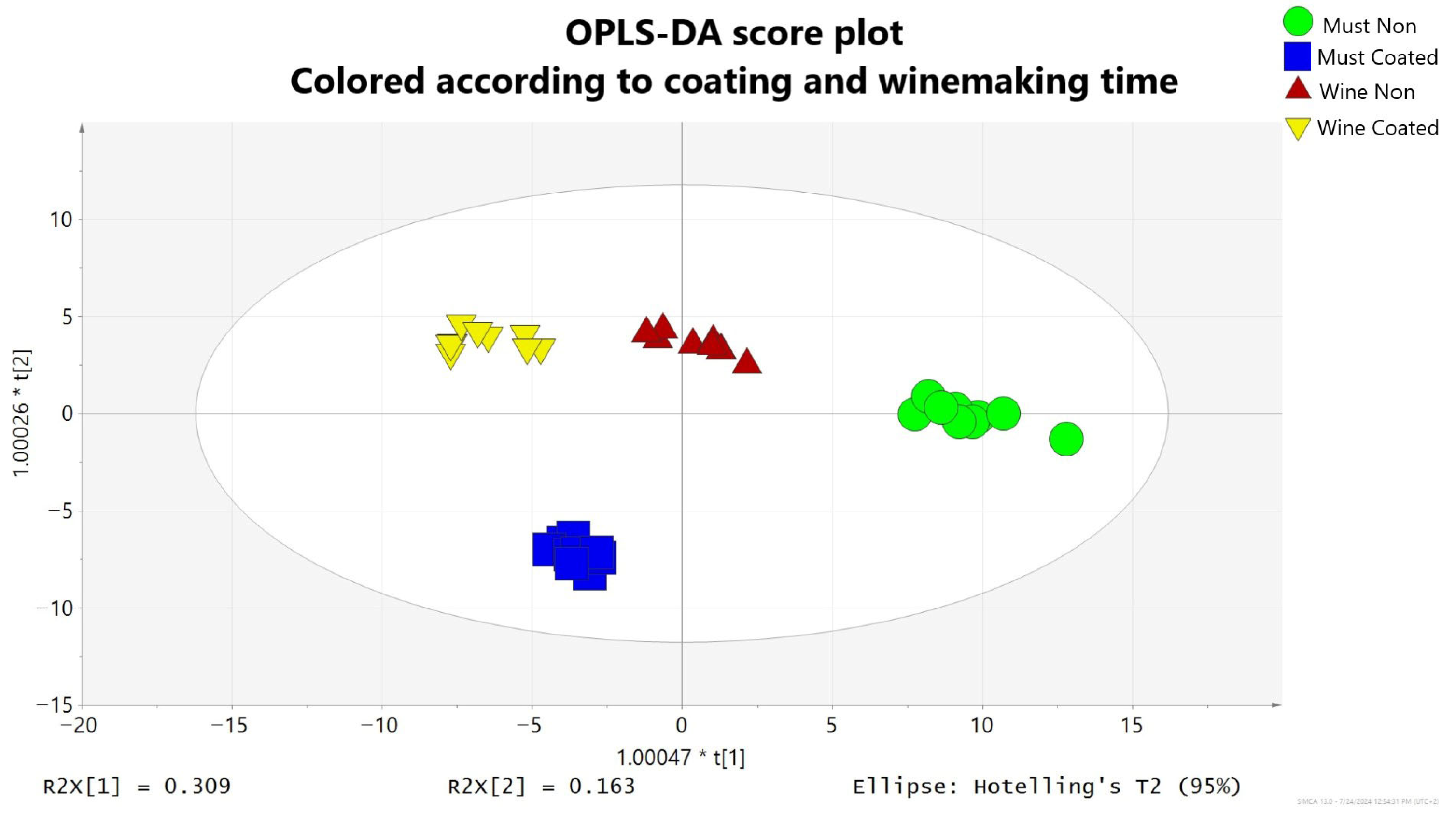

3.2.1. Wine and Must Chemical Profile

3.2.2. Anthocyanins

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Diaz, C.; Laurie, V.F.; Molina, A.M.; Bucking, M.; Fischer, R. Characterization of Selected Organic and Mineral Components of Qvevri Wines. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 2013, 64, 532–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montalvo, F.F.; García-Alcaraz, J.L.; Cámara, E.M.; Jiménez-Macías, E.; Blanco-Fernández, J. Environmental impact of wine fermentation in steel and concrete tanks. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 278, 123602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nevares, I.; Del Alamo-Sanza, M. Characterization of the Oxygen Transmission Rate of New-Ancient Natural Materials for Wine Maturation Containers. Foods 2021, 10, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curry, A. Oldest Evidence of Winemaking Discovered at 8000-Year-Old Village. National Geographic, 13 November 2017. Available online: https://news.nationalgeographic.com/2017/11/oldest-winemaking-grapes-georgia-archaeology/ (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- McGovern, P.; Jalabadze, M.; Batiuk, S.; Callahan, M.P.; Smith, K.E.; Hall, G.R.; Kvavadze, E.; Maghradze, D.; Rusishvili, N.; Bouby, L.; et al. Early Neolithic wine of Georgia in the South Caucasus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, E10309–E10318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picuno, P. Use of traditional material in farm buildings for a sustainable rural environment. Int. J. Sustain. Built Environ. 2016, 5, 451–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baiano, A.; Varva, G. Evolution of physico-chemical and sensory characteristics of Minutolo white wines during aging in amphorae: A comparison with stainless steel tanks. LWT 2019, 103, 78–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baiano, A.; Mentana, A.; Quinto, M.; Centonze, D.; Longobardi, F.; Ventrella, A.; Agostiano, A.; Varva, G.; De Gianni, A.; Terracone, C.; et al. The effect of in-amphorae aging on oenological parameters, phenolic profile and volatile composition of Minutolo white wine. Food Res. Int. 2015, 74, 294–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrini, S.; Barbato, D.; Mangani, S.; Ganucci, D.; Buscioni, G.; Galli, V.; Triossi, A.; Granchi, L. Management of in-Amphora “Trebbiano Toscano” Wine Production: Selection of Indigenous Saccharomyces cerevisiae Strains and Influence on the Phenolic and Sensory Profile. Foods 2023, 12, 2372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maioli, F.; Picchi, M.; Guerrini, L.; Parenti, A.; Domizio, P.; Andrenelli, L.; Zanoni, B.; Canuti, V. Monitoring of Sangiovese Red Wine Chemical and Sensory Parameters along One-Year Aging in Different Tank Materials and Glass Bottle. ACS Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 2, 321–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panella, C.; Tchernia, A. Agricultural products transported in amphorae: Oil and wine. In The Ancient Economy; Routledge: London, UK, 2012; pp. 173–189. [Google Scholar]

- Van Limbergen, D.; Komar, P. Making wine in earthenware vessels: A comparative approach to Roman vinification. Antiquity 2024, 98, 85–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brun, J.P. Archéologie du vin et de l’huile: De la Préhistoire à L’époque Hellénistique; Errance: Paris, France, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Estreicher, S.K. From Fermentation to Transportation: Materials in the History of Wine. MRS Bull. 2002, 27, 991–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shackelford, J.F.; Shackelford, P.L. Ceramics in the wine industry. Int. J. Ceram. Eng. Sci. 2021, 3, 18–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piergiovanni, L.; Limbo, S. Food Packaging Materials; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; pp. 204–400. [Google Scholar]

- Colombini, M.P.; Modugno, F.; Ribechini, E. Direct exposure electron ionization mass spectrometry and gas chromatography/mass spectrometry techniques to study organic coatings on archaeological amphorae. J. Mass Spectrom. 2005, 40, 675–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pecci, A.; Clarke, J.; Thomas, M.; Muslin, J.; Van Der Graaff, I.; Toniolo, L.; Miriello, D.; Crisci, G.M.; Buonincontri, M.; Di Pasquale, G. Use and reuse of amphorae. Wine residues in Dressel 2–4 amphorae from Oplontis Villa B (Torre Annunziata, Italy). J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 2017, 12, 515–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pecci, A.; Borgna, E.; Mileto, S.; Dalla Longa, E.; Bosi, G.; Florenzano, A.; Mercuri, A.M.; Corazza, S.; Marchesini, M.; Vidale, M. Wine consumption in Bronze Age Italy: Combining organic residue analysis, botanical data and ceramic variability. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2020, 123, 105256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, K.B.; Winans, R.E.; Botto, R.E. The nature and fate of natural resins in the geosphere—II. Identification, classification and nomenclature of resinites. Org. Geochem. 1992, 18, 829–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Nasa, J.; Nardella, F.; Andrei, L.; Giani, M.; Degano, I.; Colombini, M.P.; Ribechini, E. Profiling of high molecular weight esters by flow injection analysis-high resolution mass spectrometry for the characterization of raw and archaeological beeswax and resinous substances. Talanta 2020, 212, 120800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garnier, N.; Pecci, A. Amphorae and Residue Analysis: Content of Amphorae and Organic Coatings; RLAMP 17; Archaeopress: Oxford, UK, 2021; pp. 13–26. [Google Scholar]

- Rageot, M.; Lepère, C.; Henry, A.; Binder, D.; Davtian, G.; Filippi, J.J.; Fernandez, X.; Guilaine, J.; Jallet, F.; Radi, G.; et al. Management systems of adhesive materials throughout the Neolithic in the North-West Mediterranean. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2021, 126, 105309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, N.; Garcia, R.; Mendes, D.; Costa Freitas, A.M.; Da Silva, M.G.; Cabrita, M.J. An ancient winemaking technology: Exploring the volatile composition of amphora wines. LWT 2018, 96, 288–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrita, M.J.; Martins, N.; Barrulas, P.; Garcia, R.; Dias, C.B.; Pérez-Álvarez, E.P.; Freitas, A.M.C.; Garde-Cerdán, T. Multi-element composition of red, white and palhete amphora wines from Alentejo by ICPMS. Food Control 2018, 92, 80–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernal-Casasola, D.; Pecci, A.; Romero, A.M.S. Preliminary Organic Residue Analysis of Few Ovoid 1 and Ovoid 5 Amphorae from the Guadalquivir Valley; Archaeopress: Oxford, UK, 2019; pp. 391–402. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctvpmw4m6.22 (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Charters, S.; Evershed, R.P.; Quye, A.; Blinkhorn, P.W.; Reeves, V. Simulation Experiments for Determining the Use of Ancient Pottery Vessels: The Behaviour of Epicuticular Leaf Wax During Boiling of a Leafy Vegetable. J. Archaeol. Sci. 1997, 24, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salek, R.M.; Neumann, S.; Schober, D.; Hummel, J.; Billiau, K.; Kopka, J.; Correa, E.; Reijmers, T.; Rosato, A.; Tenori, L.; et al. COordination of Standards in MetabOlomicS (COSMOS): Facilitating integrated metabolomics data access. Metabolomics 2015, 11, 1587–1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Z.; Tsugawa, H.; Wohlgemuth, G.; Mehta, S.; Mueller, M.; Zheng, Y.; Ogiwara, A.; Meissen, J.; Showalter, M.; Takeuchi, K.; et al. Identifying metabolites by integrating metabolome databases with mass spectrometry cheminformatics. Nat. Methods 2018, 15, 53–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsugawa, H.; Kind, T.; Nakabayashi, R.; Yukihira, D.; Tanaka, W.; Cajka, T.; Saito, K.; Fiehn, O.; Arita, M. Hydrogen Rearrangement Rules: Computational MS/MS Fragmentation and Structure Elucidation Using MS-FINDER Software. Anal. Chem. 2016, 88, 7946–7958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandoval, V.; Femenias, A.; Martínez-Garza, Ú.; Sanz-Lamora, H.; Castagnini, J.; Quifer-Rada, P.; Lamuela-Raventós, R.M.; Marrero, P.F.; Haro, D.; Relat, J. Lyophilized Maqui (Aristotelia chilensis) Berry Induces Browning in the Subcutaneous White Adipose Tissue and Ameliorates the Insulin Resistance in High Fat Diet-Induced Obese Mice. Antioxidants 2019, 8, 360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pang, Z.; Chong, J.; Zhou, G.; de Lima Morais, D.A.; Chang, L.; Barrette, M.; Gauthier, C.; Jacques, P.É.; Li, S.; Xia, J. MetaboAnalyst 5.0: Narrowing the gap between raw spectra and functional insights. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, 9388–9396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lozano-Castellón, J.; Olmo-Cunillera, A.; Casadei, E.; Valli, E.; Domínguez-López, I.; Miliarakis, E.; Pérez, M.; Ninot, A.; Romero-Aroca, A.; Bendini, A.; et al. A targeted foodomic approach to assess differences in extra virgin olive oils: Effects of storage, agronomic and technological factors. Food Chem. 2024, 435, 137539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitrakoudi, E.A.; Mitkidou, S.A.; Urem-Kotsou, D.; Kotsakis, K.; Stephanidou-Stephanatou, J.; Stratis, J.A. Characterization by Gas Chromatography—Mass Spectrometry of Diterpenoid Resinous Materials in Roman-Age Amphorae from Northern Greece. Eur. J. Mass Spectrom. 2011, 17, 581–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Izzo, F.C.; Zendri, E.; Bernardi, A.; Balliana, E.; Sgobbi, M. The study of pitch via gas chromatography–mass spectrometry and Fourier-transformed infrared spectroscopy: The case of the Roman amphoras from Monte Poro, Calabria (Italy). J. Archaeol. Sci. 2013, 40, 595–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombini, M. Organic Mass Spectrometry in Art and Archaeology; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009; pp. 215–235. [Google Scholar]

- Savluchinske-Feio, S.; Nunes, L.; Pereira, P.T.; Silva, A.M.; Roseiro, J.C.; Gigante, B.; Curto, M.J.M. Activity of dehydroabietic acid derivatives against wood contaminant fungi. J. Microbiol. Methods 2007, 70, 7465–7470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woldemichael, G.M.; Wächter, G.; Singh, M.P.; Maiese, W.M.; Timmermann, B.N. Antibacterial Diterpenes from Calceolaria pinifolia. J. Nat. Prod. 2003, 66, 242–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCadden, C.A.; Alsup, T.A.; Ghiviriga, I.; Rudolf, J.D. Biocatalytic diversification of abietic acid in Streptomyces. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2024, 52, kuaf003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prinz, S.; Müllner, U.; Heilmann, J.; Winkelmann, K.; Sticher, O.; Haslinger, E.; Hüfner, A. Oxidation Products of Abietic Acid and Its Methyl Ester. J. Nat. Prod. 2002, 65, 1530–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González, M.A.; Pérez-Guaita, D.; Correa-Royero, J.; Zapata, B.; Agudelo, L.; Mesa-Arango, A.; Betancur-Galvis, L. Synthesis and biological evaluation of dehydroabietic acid derivatives. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2010, 45, 811–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.K.; Liu, L.; Wang, J.J.; Qian, F.; Yang, M.Q.; Zhang, L.Q.; Fu, J.G.; Li, Y.M.; Feng, C.G. An asymmetric synthesis of (+)-Scrodentoid A from dehydroabietic acid. Tetrahedron 2021, 85, 132031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavit, V.R.; Kundu, S.; Niyogi, S.; Roy, N.K.; Bisai, A. Total Synthesis of Diterpenoid Quinone Methide Tumor Inhibitor, (+)-Taxodione. J. Org. Chem. 2024, 89, 1823–1835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, U.; Berglund, N.; Lindahl, F.; Axelsson, S.; Redeby, T.; Lassen, P.; Karlberg, A.T. SPE and HPLC/UV of resin acids in colophonium-containing products. J. Sep. Sci. 2008, 31, 2784–2790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerković, I.; Marijanović, Z.; Gugić, M.; Roje, M. Chemical Profile of the Organic Residue from Ancient Amphora Found in the Adriatic Sea Determined by Direct GC and GC-MS Analysis. Molecules 2011, 16, 7936–7948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kargar, N.; Matin, G.; Matin, A.A.; Buyukisik, H.B. Biomonitoring, status and source risk assessment of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) using honeybees, pine tree leaves, and propolis. Chemosphere 2017, 186, 140–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Gu, R.; Sheng, Y.; Zeng, N.; Zhan, X. Acropetal translocation of phenanthrene in wheat seedlings: Xylem or phloem pathway? Environ. Pollut. 2020, 260, 114055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Zhang, J.; Krebs, P. Consumption-and income-based sectoral emissions of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in China from 2002 to 2017. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 55, 3582–3592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Tel, T.; Tarazi, H.; Aloum, L.; Lorke, D.; Petroianu, G. Possible metabolic conversion of pinene to ionone. Die Pharm.—Int. J. Pharm. Sci. 2020, 75, 360–363. [Google Scholar]

- Plotto, A.; Barnes, K.W.; Goodner, K.L. Specific Anosmia Observed for β -Ionone, but not for α-Ionone: Significance for Flavor Research. J. Food Sci. 2006, 71, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinbo, Y.; Nakamura, Y.; Altaf-Ul-Amin, M.; Asahi, H.; Kurokawa, K.; Arita, M.; Saito, K.; Ohta, D.; Shibata, D.; Kanaya, S. KNApSAcK: A Comprehensive Species-Metabolite Relationship Database. In Plant Metabolomics; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2006; pp. 165–181. [Google Scholar]

- Biva, I.J.; Ndi, C.P.; Semple, S.J.; Griesser, H.J. Antibacterial Performance of Terpenoids from the Australian Plant Eremophila lucida. Antibiotics 2019, 8, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balsells-Llauradó, M.; Vall-llaura, N.; Usall, J.; Silva, C.J.; Blanco-Ulate, B.; Teixidó, N.; Caballol, M.; Torres, R. Transcriptional profiling of the terpenoid biosynthesis pathway and in vitro tests reveal putative roles of linalool and farnesal in nectarine resistance against brown rot. Plant Sci. 2023, 327, 111558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera, R.; Da Silva, D.T.; Llano-Ponte, R.; Labidi, J. Characterization of pine wood liquid and solid residues generated during industrial hydrothermal treatment. Biomass Bioenergy 2016, 95, 174–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rokade, Y.B.; Sayyed, R. Naphthalene derivatives: A new range of antimicrobials with high therapeutic value. Rasayan J. Chem. 2009, 2, 972–980. [Google Scholar]

- Mármol, I.; Quero, J.; Jiménez-Moreno, N.; Rodríguez-Yoldi, M.J.; Ancín-Azpilicueta, C. A systematic review of the potential uses of pine bark in food industry and health care. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 88, 558–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vek, V.; Poljanšek, I.; Humar, M.; Willför, S.; Oven, P. In vitro inhibition of extractives from knotwood of Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris) and black pine (Pinus nigra) on growth of Schizophyllum commune, Trametes versicolor, Gloeophyllum trabeum and Fibroporia vaillantii. Wood Sci. Technol. 2020, 54, 1645–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conde, E.; Cara, C.; Moure, A.; Ruiz, E.; Castro, E.; Domínguez, H. Antioxidant activity of the phenolic compounds released by hydrothermal treatments of olive tree pruning. Food Chem. 2009, 114, 806–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanda, S.; Mohanty, P.; Kozinski, J.A.; Dalai, A.K. Physico-chemical properties of bio-oils from pyrolysis of lignocellulosic biomass with high and slow heating rate. Energy Environ. Res. 2014, 4, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd El-Ghafar, O.A.M.; Hassanein, E.H.M.; Sayed, A.M.; Rashwan, E.K.; Shalkami, A.S.; Mahmoud, A.M. Acetovanillone prevents cyclophosphamide-induced acute lung injury by modulating PI3K/Akt/mTOR and Nrf2 signaling in rats. Phytother. Res. 2021, 35, 4499–4510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tai, A.; Sawano, T.; Yazama, F. Antioxidant Properties of Ethyl Vanillin in Vitro and in Vivo. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2011, 75, 2346–2350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhardwaj, K.; Silva, A.S.; Atanassova, M.; Sharma, R.; Nepovimova, E.; Musilek, K.; Sharma, R.; Alghuthaymi, M.A.; Dhanjal, D.S.; Nicoletti, M.; et al. Conifers Phytochemicals: A Valuable Forest with Therapeutic Potential. Molecules 2021, 26, 3005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virjamo, V.; Fyhrquist, P.; Koskinen, A.; Lavola, A.; Nissinen, K.; Julkunen-Tiitto, R. 1,6-Dehydropinidine Is an Abundant Compound in Picea abies (Pinaceae) Sprouts and 1,6-Dehydropinidine Fraction Shows Antibacterial Activity against Streptococcus equi Subsp. equi. Molecules 2020, 25, 4558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, T.; Manivannan, H.P.; Veeraraghavan, V.P.; Sankaran, K.; Francis, A.P. Selective plant alkaloids as potential inhibitors of PARP in pancreatic cancer-An in silico study. Indian J. Biochem. Biophys. IJBB 2023, 60, 66–555. [Google Scholar]

- Davara, J.; Jambrina-Enríquez, M.; Rodríguez De Vera, C.; Herrera-Herrera, A.V.; Mallol, C. Pyrotechnology and lipid biomarker variability in pine tar production. Archaeol. Anthropol. Sci. 2023, 15, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de-la-Fuente-Blanco, A.; Ferreira, V. Gas Chromatography Olfactometry (GC-O) for the (Semi)Quantitative Screening of Wine Aroma. Foods 2020, 9, 1892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Ma, W.; Meng, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Jin, G.; Fang, Z. Wine phenolic profile altered by yeast: Mechanisms and influences. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2021, 20, 3579–3619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira-Alves, S.; Lourenço, S.; Fernandes, T.A.; Canas, S. Coumarins in Spirit Beverages: Sources, Quantification, and Their Involvement in Quality, Authenticity and Food Safety. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zenkevich, I.G.; Eshchenko, A.Y.; Makarova, S.V.; Vitenberg, A.G.; Dobryakov, Y.G.; Utsal, V.A. Identification of the Products of Oxidation of Quercetin by Air Oxygenat Ambient Temperature. Molecules 2007, 12, 654–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deokar, R.G.; Barik, A. Transient species of esculetin produced in pulse radiolysis: Experimental and quantum chemical investigations. Phys. Chem. 2020, 22, 18573–18584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutiérrez-Escobar, R.; Aliaño-González, M.J.; Cantos-Villar, E. Wine Polyphenol Content and Its Influence on Wine Quality and Properties: A Review. Molecules 2021, 26, 718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winstel, D.; Gautier, E.; Marchal, A. Role of Oak Coumarins in the Taste of Wines and Spirits: Identification, Quantitation, and Sensory Contribution through Perceptive Interactions. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2020, 68, 7434–7443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rihak, Z.; Prusova, B.; Kumsta, M.; Baron, M. Effect of Must Hyperoxygenation on Sensory Expression and Chemical Composition of the Resulting Wines. Molecules 2021, 27, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustamante, M.; Gil-Cortiella, M.; Peña-Neira, Á.; Gombau, J.; García-Roldán, A.; Cisterna, M.; Montané, X.; Fort, F.; Rozès, N.; Canals, J.M.; et al. Oxygen-induced enzymatic and chemical degradation kinetics in wine model solution of selected phenolic compounds involved in browning. Food Chem. 2025, 484, 144421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrascón, V.; Bueno, M.; Fernandez-Zurbano, P.; Ferreira, V. Oxygen and SO2 Consumption Rates in White and Rosé Wines: Relationship with and Effects on Wine Chemical Composition. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2017, 65, 9488–9495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; He, F.; Zhou, P.P.; Liu, Y.; Duan, C.Q. Copigmentation between malvidin-3-O-glucoside and hydroxycinnamic acids in red wine model solutions: Investigations with experimental and theoretical methods. Food Res. Int. 2015, 78, 313–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Du, G.; Wang, S.; Zhao, P.; Cao, X.; Cheng, C.; Liu, H.; Xue, Y.; Wang, X. Investigating the role of tartaric acid in wine astringency. Food Chem. 2023, 403, 134385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berovic, M.; Kosmerl, T. Monitoring of potassium hydrogen tartrate stabilization by conductivity measurement. Acta Chim. Slov. 2008, 55, 535–540. [Google Scholar]

- Yılmaz, C.; Gökmen, V. Formation of amino acid derivatives in white and red wines during fermentation: Effects of non-Saccharomyces yeasts and Oenococcus oeni. Food Chem. 2021, 343, 128415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turska, M.; Rutyna, R.; Paluszkiewicz, M.; Terlecka, P.; Dobrowolski, A.; Pelak, J.; Turski, M.P.; Muszyńska, B.; Dabrowski, W.; Kocki, T.; et al. Presence of kynurenic acid in alcoholic beverages—Is this good news, or bad news? Med. Hypotheses 2019, 122, 200–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gambuti, A.; Picariello, L.; Rinaldi, A.; Moio, L. Evolution of Sangiovese Wines with Varied Tannin and Anthocyanin Ratios During Oxidative Aging. Front. Chem. 2018, 6, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mangani, S.; Buscioni, G.; Collina, L.; Bocci, E.; Vincenzini, M. Effects of Microbial Populations on Anthocyanin Profile of Sangiovese Wines Produced in Tuscany, Italy. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 2011, 62, 487–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yermolin, D.; Yermolina, G.; Gerber, Y.; Zadorozhnaya, D.; Kotolovets, Z. Phenolic complex of red wine materials from grapes growing in the Crimea. E3S Web Conf. 2020, 175, 08002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallverdú-Queralt, A.; Meudec, E.; Eder, M.; Lamuela-Raventos, R.M.; Sommerer, N.; Cheynier, V. Targeted filtering reduces the complexity of UHPLC-Orbitrap-HRMS data to decipher polyphenol polymerization. Food Chem. 2017, 227, 255–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallverdú-Queralt, A.; Meudec, E.; Ferreira-Lima, N.; Sommerer, N.; Dangles, O.; Cheynier, V.; Le Guernevé, C. A comprehensive investigation of guaiacyl-pyranoanthocyanin synthesis by one-/two-dimensional NMR and UPLC–DAD–ESI–MSn. Food Chem. 2016, 199, 902–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Metabolite Name | Exact Mass | Adduct | RT (min) | Error (ppm) | MS/MS Majority Fragments (Intensity) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diterpenoids | |||||

| Hydroxydehydroabietic acid isomer 1 | 299.20145 | [M−H2O+H]+ | 7.187 | −2.7 | 155.08615 (16,282); 159.11694 (5873); 211.14789 (6354); 253.19463 (11,701); 197.13223 (6035) |

| Hydroxydehydroabietic acid isomer 2 | 299.20139 | [M−H2O+H]+ | 7.908 | −2.7 | 155.08594 (16,919); 253.19516 (12,193); 211.14859 (9890); 133.10124 (8078); 117.07057 (5019) |

| Hydroxydehydroabietic acid isomer 3 | 299.20132 | [M−H2O+H]+ | 12.104 | −2.3 | 155.08569: (29,841); 253.19525: (27,501); 211.14841 (17,932); 197.13234 (14,186); 133.10144 (12,894) |

| Abietic acid | 303.23254 | [M+H]+ | 8.214 | −2.1 | 123.11738 (25,683); 121.1014 (17,131); 135.11754 (14,543); 107.08598 (13,703); 149.13266 (9772) |

| Nor-abietatetraene isomer 1 | 255.21158 | [M+H]+ | 9.418 | −3.4 | 171.11717 (38,139); 143.08554 (9124); 156.09375 (6957); 128.06276 (2680); 142.07762 (2179) |

| Nor-abietatetraene isomer 2 | 255.21191 | [M+H]+ | 9.746 | −4.6 | 171.11713 (14,598); 143.08574 (3778); 123.11701 (2977); 199.14777:2267; 156.09427 (2205) |

| Dehydroabietic acid isomer 1 | 301.21686 | [M+H]+ | 11.935 | −2.3 | 199.14795 (10,474); 109.10152 (10,150); 143.08582 (9216); 105.07001 (9042); 121.10129 (8698) |

| 12-Oxo-abietic acid | 317.21185 | [M+H]+ | 12.055 | −2.3 | 317.21127 (13,759); 107.04906 (6792); 147.08023 (4061); 133.06474 (3628); 59.11662 (2141) |

| Phenanthrene carboxylic acid dodecahydrohydroxydimethylmethylethyl | 317.21194 | [M−H2O+H]+ | 12.27 | −2.1 | 155.08615 (16,282); 253.19463 (11,701); 197.13223 (6035); 211.14789 (6354); 159.11694 (5873) |

| 7-Oxo-norabietatriene | 269.19101 | [M+H]− | 12.871 | −3.8 | 213.12778 (112,433); 171.0808 (106,761); 227.14305 (17,489); 211.11169 (11,307); 143.0858 (10,233) |

| Dehydroabietic acid isomer 2 | 301.21704 | [M+H]+ | 13.373 | −2.7 | 133.10153 (3843); 105.06971 (2939); 185.1319 (2784); 147.11729 (2639) 143.08575 (2300); |

| Dehydroabietinal isomer 1 | 285.22205 | [M+H]+ | 13.569 | −2.5 | 145.10132 (21,886); 117.06982 (14,934); 125.09614 (12,849); 133.1012 (12,851); 105.07013 (12,318) |

| Dehydroabietinal isomer 2 | 285.22223 | [M+H]+ | 13.704 | −3.2 | 145.1013 (23,601); 117.07012 (9694); 125.09616 (8414); 105.06988 (6866); 187.14833 (4514) |

| Salvirecognine | 271.20648 | [M+H]+ | 13.853 | −3.2 | 147.08063 (34,785); 109.10129 (13,594); 155.08595 (12,211); 189.12756 (11,643); 271.2059 (11,201) |

| Sesquiterpenoids | |||||

| Beta-Ionone | 193.15941 | [M+H]+ | 6.138 | 3.24 | 107.0854 (616); 137.0943 (535); 175.14847 (500); 133.10007 (416); 178.07945 (404) |

| Farnesal | 221.19019 | [M+H]+ | 11.306 | −0.9 | 221.19031 (3248); 178.134 (503); 150.10321 (454); 165.12466 (373); 149.09468 (290) |

| Fatty amides | |||||

| Oleamide | 282.27997 | [M+H]+ | 7.209 | −3 | 107.08616 (1178); 100.07643 (888); 121.1006 (642); 109.10107 (492); 114.09127 (440) |

| Palmitic amide | 256.26443 | [M+H]+ | 8.346 | −3.5 | 256.26373 (15,856); 102.09136 (5345); 116.10683 (1647); 130.12434 (571); 186.1833 (497) |

| Dodecanamide | 200.20161 | [M+H]+ | 12.186 | −3.6 | 102.09159 (1735); 116.10857 (868); 200.2011 (6335); 100.07675 (466); 130.12204 (229) |

| Linoleamide | 280.26413 | [M+H]+ | 13.047 | −2.2 | 109.10132 (6707); 133.101 (5098); 107.08582 (4150); 105.06998 (3705); 121.10113 (3414) |

| Docosenamide | 338.34256 | [M+H]+ | 13.918 | −2.5 | 121.10126 (2464); 100.0754 (1506); 107.08583 (1171); 135.11635 (1093); 114.09082 (997) |

| Naphthalene derivatives | |||||

| Dihydrotrimethylnaphthalene isomer 1 | 173.13297 | [M+H]+ | 7.011 | −3 | 131.08594 (3189); 116.06136 (358); 129.06964 (274); 115.05321 (212); 117.0714 (135) |

| Dihydrotrimethylnaphthalene isomer 2 | 173.13316 | [M+H]+ | 7.951 | −4.2 | 173.13266 (8316); 129.06953 (3288); 116.06165 (1697); 115.05361 (955); 117.06962 (808) |

| Vinylphenyl compounds | |||||

| Methoxy-phenylethenyl phenol | 227.10768 | [M+H]+ | 6.794 | −4.6 | 121.06529 (8679); 117.07023 (4178); 103.05476 (3953); 212.0831 (3704); 149.06018 (2917) |

| Dimethoxystilbene | 241.12334 | [M+H]+ | 7.558 | −4.1 | 117.07041 (9906); 226.09904 (8910); 194.07274 (5523); 165.07045 (5174); 115.05405 (4725) |

| Aromatic compounds | |||||

| Acetovanillone | 167.07111 | [M+H]+ | 6.968 | −4.9 | 121.02875 (20,456); 149.05962 (4628); 167.06958 (1376); 139.03828 (408); 149.00977 (257) |

| Ethyl vanillin | 167.07088 | [M+H]+ | 12.022 | −3.8 | 121.02848 (61,958); 149.05972 (16,175); 167.07042 (3802); 139.039 (3089); 123.0803 (1574) |

| Piperidines | |||||

| Pinidinol | 158.15468 | [M+H]+ | 6.226 | −4.8 | 102.09148 (1818); 126.12804 (282); 116.04947 (251); 130.98596 (214); 143.08549 (97) |

| Pinidine | 140.14388 | [M+H]+ | 8.63 | −3.76 | 140.144 (72,697); 138.12784 (6136); 111.1044 (3461); 110.09634 (2206); 112.11227 (2156) |

| Metabolite Name | Exact Mass | Adduct | RT (min) | Error (ppm) | MS/MS Majority Fragments (Intensity) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aminobutyric acid betaine | 146.11815 | [M+H]+ | 0.62 | −3.0 | 100.07588 (159); 101.05954 (45); 114.09331 (53); 146.12959 (1553) |

| Tartaric acid | 149.00964 | [M−H]− | 1.067 | −2.9 | 103.0052 (123); 105.01963 (235); 132.07819 (90); 148.90419 (98) |

| Acetylproline | 158.08163 | [M+H]+ | 3.364 | −1.5 | 112.07526 (467); 116.06914 (393); 117.06858 (124); 158.11858 (58) |

| Levoglucosan | 161.0462 | [M−H]− | 2.851 | −4.0 | 101.02549 (761); 115.00488 (163); 117.05934 (66); 160.89748 (48) |

| Tryptophol | 162.09164 | [M+H]+ | 5.192 | −2.8 | 117.07004 (1833); 130.06619 (731); 143.0726 (1651); 144.08101 (16,180) |

| Coumaric acid | 163.04121 | [M−H]−, [M+H−H2O]+ | 4.063 | −4.5 | 113.30286 (78); 119.0507 (3117); 130.0323 (64); 163.00392 (219) |

| Phenylalanine | 166.08661 | [M+H]+, [M−H]− | 2.487 | −2.7 | 103.05387 (1210); 107.04926 (395); 120.08129 (5796); 119.05094 (3710) |

| Ethyl vanillin | 167.07057 | [M+H]+ | 3.578 | −2.6 | 106.04202 (382); 123.04397 (1151); 124.05251 (358); 167.0713 (2675) |

| Gallic acid | 169.01564 | [M−H]− | 1.599 | −5.0 | 107.01315 (144); 124.01756 (1025); 125.0247 (8539); 161.38852 (219) |

| Pyridoxine | 170.08177 | [M+H]+ | 1.583 | −2.5 | 107.01307 (3051); 109.02811 (1721); 125.02496 (820); 153.01802 (960) |

| Aesculetin | 177.02003 | [M−H]−, [M+H]+ | 4.187 | −3.8 | 105.03596 (1012); 133.03026 (797); 149.024 (259); 177.0195 (2110) |

| Dihydroxycoumarin | 177.02013 | [M−H]− | 3.625 | −4.3 | 129.54765 (190); 133.02939 (113); 162.85072 (92); 169.45374 (58) |

| Tyrosine | 182.08162 | [M+H]+ | 0.996 | −4.0 | 119.04949 (1222); 123.04349 (1273); 136.07573 (1754); 147.04497 (514) |

| O-methylgallic acid | 185.04503 | [M+H]+ | 2.272 | −3.0 | 111.04411 (93); 139.03758 (558); 143.89607 (179); 144.90154 (80) |

| Tryptophan | 188.07155 | [M+H]+ | 3.728 | −2.1 | 118.06576 (6121); 143.07353 (1111); 144.08104 (2491); 146.05969 (5360) |

| Kynurenic Acid | 190.04971 | [M+H]+ | 3.964 | −0.2 | 107.04875 (99); 116.04951 (709); 144.04475 (4077); 162.21191 (56) |

| Citrate | 191.02113 | [M−H]− | 0.956 | −4.5 | 103.04139 (381); 111.00914 (22,274); 129.01886 (391); 130.54572 (212) |

| Ferulic acid | 193.05124 | [M−H]− | 4.199 | −2.4 | 126.96464 (55); 133.02979 (165); 133.16936 (36); 134.03615 (249) |

| Carvyl acetate | 195.13777 | [M+H]+ | 5.746 | 0.8 | 109.10175 (583); 119.08447 (283); 121.10174 (414); 137.09581 (1376) |

| Linalool acetate | 195.13969 | [M−H]− | 6.768 | −3.2 | 160.84276 (201); 167.14275 (176); 179.10927 (205); 195.13882 (1264) |

| Indolelactic acid | 206.08124 | [M+H]+ | 4.465 | −1.6 | 118.06466 (1050); 130.06508 (557); 170.06226 (377); 188.07065 (371) |

| Pantothenic acid | 218.10405 | [M−H]− | 3.428 | −3.2 | 116.07175 (300); 146.08296 (781); 208.59618 (118); 218.10118 (103) |

| Coniferyl acetate | 221.08205 | [M−H]− | 5.118 | −0.3 | 149.05922 (237); 157.06602 (135); 176.96494 (267); 195.9342 (125) |

| Leucylproline | 229.15515 | [M+H]+ | 1.578 | −2.3 | 114.09164 (283); 121.02687 (308); 142.08659 (3633); 229.15413 (3455) |

| Prolyl-isoleucine | 229.1552 | [M+H]+ | 0.887 | −3.2 | 114.05534 (2929); 116.07116 (1570); 142.08662 (21,438); 229.15469 (27,800) |

| Cysteinosuccinic acid | 238.03856 | [M+H]+ | 0.689 | −2.6 | 102.9845 (2398); 120.99609 (1341); 156.01283 (577); 184.00565 (718) |

| Prenyl caffeate | 249.11253 | [M+H]+ | 4.685 | −1.5 | 107.05048 (443); 129.07048 (978); 131.08498 (500); 204.07907 (589) |

| N-(tetradecanoyl)ethanolamine | 272.259 | [M+H]+ | 6.142 | −2.2 | 155.85768 (111); 171.8539 (419) 189.86389 (186); 258.27927 (2915) |

| Catechin | 289.07352 | [M−H]−, [M+H]+ | 4.039 | −4.6 | 109.03095 (5688); 121.0307 (903); 123.04592 (4149); 125.02528 (2574) |

| Epicatechin | 291.08679 | [M+H]+ | 4.262 | −1.6 | 123.04404 (8652); 139.03899 (10,130); 147.04361 (2115); 161.05923 (1763) |

| Argininosuccinic acid | 291.13089 | [M+H]+ | 0.777 | −3.4 | 116.07103 (1470); 130.09784 (1057); 134.04478 (1109); 158.09224 (1062) |

| Cyclopenteneoctanoic acid | 293.21182 | [M+H]+ | 5.667 | −2.3 | 105.06916 (381); 107.0499 (247); 107.08562 (580); 109.09935 (218) |

| Tetradecyliminodiethanol | 302.30579 | [M+H]+ | 6.464 | −2.5 | 104.06934 (214); 256.26303 (3755); 302.27063 (586); 302.3046 (460) |

| Quercetin | 303.05035 | [M+H]+ | 4.604 | −1.5 | 128.86797 (196); 137.02216 (410); 229.04767 (193); 303.04892 (1683) |

| Gentisic acid O-hexoside | 315.07315 | [M−H]− | 3.354 | −3.3 | 108.0223 (12,894); 109.03048 (3425); 152.01173 (7460); 153.02017 (1827) |

| Coumaric acid O-hexoside | 325.09305 | [M−H]− | 4.069 | −0.6 | 117.03597 (291); 119.05083 (20,129); 145.0298 (1917); 163.0405 (4063) |

| Vanilloyl-O-hexoside | 329.08859 | [M−H]− | 4.415 | −2.4 | 123.0458 (4655); 125.02437 (710); 167.0363 (5833); 191.03442 (568) |

| Gallic acid-O-hexoside | 331.06735 | [M−H]− | 2.05 | −1.0 | 125.02487 (1437); 151.00302 (286); 165.01988 (316); 169.01411 (2356) |

| Pyridoxine-O-hexoside | 332.13547 | [M+H]+ | 0.944 | −4.9 | 108.08124 (27,296); 124.07555 (4617); 134.06006 (2966); 136.07584 (4181) |

| Methyl gallate-O-hexoside | 345.08395 | [M−H]− | 2.271 | −3.7 | 139.04128 (13,792); 140.04408 (265); 153.05818 (242); 163.0403 (474) |

| Carboxymethyl epicatechin | 347.07755 | [M−H]− | 4.592 | −0.7 | 121.02943 (307); 166.02495 (274); 271.6481 (197); 291.69943 (171) |

| 6-O-fatty acyl-O-hexoside | 353.07346 | [M−H]− | 0.834 | −2.7 | 111.00956 (36,441); 112.01301 (284); 154.99751 (322); 165.95815 (173) |

| Syringic acid-O-hexoside | 359.09894 | [M−H]− | 3.628 | −1.5 | 123.00919 (1313); 138.03281 (2358); 153.05646 (1122); 182.02304 (1853) |

| Syringin-O-hexoside | 359.09952 | [M−H]− | 1.157 | −3.1 | 128.96178 (197); 167.95267 (283); 170.97278 (262); 182.00439 (252) |

| Tetrahydroxy-tetramethoxyflavone | 387.07211 | [M−H2O−H]− | 3.935 | 0.1 | 125.02521 (394); 164.01118 (951); 167.03485 (511); 308.02902 (215) |

| Tetrahydroxy-dimethoxyflavone-acetate | 387.07275 | [M−H]− | 4.112 | 0.9 | 125.02503 (959); 163.00285 (487); 164.01192 (1961); 207.06435 (607) |

| Resveratrol-O-hexoside | 389.1257 | [M−H]− | 4.946 | −2.1 | 143.05177 (368); 157.06528 (442); 185.06099 (694); 227.07249 (6972) |

| Apigenin-O-hexoside | 403.10266 | [M+H]+, [M−H]− | 4.3 | −0.6 | 167.0338 (2511); 194.05806 (314); 222.05153 (614); 237.07681 (5309) |

| Astilbin | 449.10883 | [M−H]− | 4.701 | 0.3 | 107.01384 (639); 151.00438 (1115); 151.03992 (566); 152.01263 (707) |

| Peonidin-O-hexoside Isomer I | 461.10953 | [M−2H]− | 4.068 | −2.5 | 147.009 (337); 148.017 (480); 229.05307 (137); 211.04135 (412); 227.03525 (582) |

| Peonidin-O-hexoside Isomer II | 461.13187 | [M−H]− | 3.874 | 0.8 | 211.03944 (304); 227.03413 (353); 255.02911 (841); 256.03693 (524) |

| Quercetin-O-hexoside | 463.08871 | [M−H]− | 4.591 | −1.1 | 151.00304 (1045); 178.99954 (786); 255.02904 (2442); 300.02783 (13,213) |

| Delphinidin-O-hexoside | 465.10376 | [M]+, [M−2H]− | 3.732 | −0.7 | 116.9828 (268); 243.02551 (157); 285.03604 (149); 304.05365 (387) |

| Leucodelphinidin-O-hexoside | 467.11896 | [M−H]− | 3.711 | −0.9 | 109.02991 (617); 125.02531 (1108); 137.02364 (1114); 151.04021 (1024) |

| Epigallocatechin methylgallate | 473.10883 | [M+H]+ | 4.032 | −2.0 | 255.06308 (316); 283.05536 (328); 311.05511 (12,324); 312.06018 (595) |

| Syringetin-O-hexoside | 507.11331 | [M−H]− | 4.781 | −1.0 | 242.02228 (705); 245.04523 (1696); 273.04019 (1122); 283.02597 (1040); 344.05469 (1393) |

| Dihydrodehydrodiconiferyl alcohol-O-hexoside | 521.20343 | [M−H]− | 4.195 | −1.1 | 109.03052 (1457); 313.10938 (2172); 344.12653 (7490); 359.15076 (3562) |

| Procyanidin B1 dimer 1 | 579.15118 | [M+H]+ | 3.856 | −1.5 | 123.04429 (2314); 127.03931 (7446); 135.04451 (2811); 139.03914 (4671) |

| Procyanidin B1 dimer 2 | 579.15094 | [M+H]+ | 4.127 | −0.9 | 123.04432 (3096); 127.0392 (5317); 135.04445 (1925); 139.03851 (3331) |

| Naringin | 579.17334 | [M−H]−, [M+FA−H]−, [M+H]+ | 4.647 | −2.4 | 162.03224 (885); 177.0565 (3629); 205.05128 (1169); 219.06702 (2082) |

| Eriodictyol-O-hexoside-Pentoside | 581.15173 | [M−H]− | 4.334 | 0.5 | 272.03314 (547); 300.02737 (3341); 315.05026 (3288); 316.05701 (529) |

| O-Coumaroyltrifolin | 593.1297 | [M−H]− | 3.571 | 0.6 | 125.0249 (2188); 175.03925 (531); 177.01942 (741); 179.03432 (572) |

| Cyanidin-O-dihexoside | 611.16071 | [M]+ | 3.344 | 0.6 | 110.07099 (125); 221.08005 (155); 287.05588 (4460); 288.05411 (340) |

| Quercetin-O-dihexoside | 625.14172 | [M−H]− | 4.295 | −1.1 | 151.00378 (806); 271.02426 (941); 300.02713 (6067); 301.03458 (4671) |

| Procyanidin C1 dimer 1 | 865.19873 | [M−H]− | 4.286 | −0.3 | 125.02456 (7189); 161.02429 (2838); 243.02972 (1783); 289.07251 (2062) |

| Procyanidin C1 dimer 2 | 865.19897 | [M−H]− | 4.03 | 0.1 | 125.02441 (3970); 161.02467 (2332); 243.02951 (1281); 407.07571 (1754) |

| Procyanidin C1 dimer 3 | 865.19916 | [M−H]− | 3.434 | −0.1 | 125.02494 (3376); 243.03169 (1070); 289.07239 (1190); 407.07825 (1015) |

| Compound | VIP Value | p-Value |

|---|---|---|

| Coumaric acid | 1.748 | 1.01 × 10−6 |

| Esculetin | 1.339 | 1.17 × 10−4 |

| Tartaric acid | 1.462 | 1.46 × 10−12 |

| Procyanidin C1 dimer 1 | 1.270 | 1.21 × 10−4 |

| Procyanidin C1 dimer 2 | 1.246 | 1.12 × 10−4 |

| Procyanidin C1 dimer 3 | 1.228 | 8.42 × 10−6 |

| Procyanidin B1 dimer 2 | 1.167 | 4.01 × 10−4 |

| Kynurenic Acid | 1.169 | 2.82 × 10−8 |

| Sample | Delphinidin-3-O-glucoside * (µg/mL) | Cyanidin-3-O-glucoside (µg/mL) | Petunidin-3-O-glucoside (µg/mL) | Peonidin-3-O-glucoside * (µg/mL) | Malvidin-3-O-glucoside (µg/mL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Must from non-coated vessel | 8.27 ± 0.15 | 11.32 ± 0.21 | 18.11 ± 0.66 | 20.17 ± 0.21 | 60.58 ± 1.21 |

| Must from coated vessel | 7.08 ± 0.14 | 10.86 ± 0.25 | 16.03 ± 0.44 | 18.88 ± 0.50 | 57.29 ± 1.85 |

| Wine from non-coated vessel | 5.35 ± 0.33 | 5.10 ± 0.10 | 10.94 ± 0.42 | 9.10 ± 0.36 | 33.73 ± 0.87 |

| Wine from coated vessel | 7.96 ± 0.16 | 7.37 ± 0.08 | 15.05 ± 0.24 | 12.05 ± 0.17 | 39.92 ± 0.78 |

| Difference p-value | 0.0000 | 0.0002 | 0.0000 | 0.0005 | 0.0042 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Abarca-Rivas, C.; Lozano-Castellón, J.; Pérez, M.; Corrado, M.; Vallverdú-Queralt, A.; Zifferero, A.; Chessa, R.; Reynolds, P.; Pecci, A.; Lamuela-Raventós, R.M. Exploring the Impact of Pitch-Coated Pottery on Wine Composition: Metabolomics Characterization of an Ancient Technique. Foods 2025, 14, 3857. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14223857

Abarca-Rivas C, Lozano-Castellón J, Pérez M, Corrado M, Vallverdú-Queralt A, Zifferero A, Chessa R, Reynolds P, Pecci A, Lamuela-Raventós RM. Exploring the Impact of Pitch-Coated Pottery on Wine Composition: Metabolomics Characterization of an Ancient Technique. Foods. 2025; 14(22):3857. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14223857

Chicago/Turabian StyleAbarca-Rivas, Clara, Julián Lozano-Castellón, Maria Pérez, Marina Corrado, Anna Vallverdú-Queralt, Andrea Zifferero, Riccardo Chessa, Paul Reynolds, Alessandra Pecci, and Rosa M. Lamuela-Raventós. 2025. "Exploring the Impact of Pitch-Coated Pottery on Wine Composition: Metabolomics Characterization of an Ancient Technique" Foods 14, no. 22: 3857. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14223857

APA StyleAbarca-Rivas, C., Lozano-Castellón, J., Pérez, M., Corrado, M., Vallverdú-Queralt, A., Zifferero, A., Chessa, R., Reynolds, P., Pecci, A., & Lamuela-Raventós, R. M. (2025). Exploring the Impact of Pitch-Coated Pottery on Wine Composition: Metabolomics Characterization of an Ancient Technique. Foods, 14(22), 3857. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14223857