Coral-like Magnetic Metal–Organic Framework for Selective Adsorption and Detection of Thiabendazole in Tomato and Chinese Cabbage Samples

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Instrument

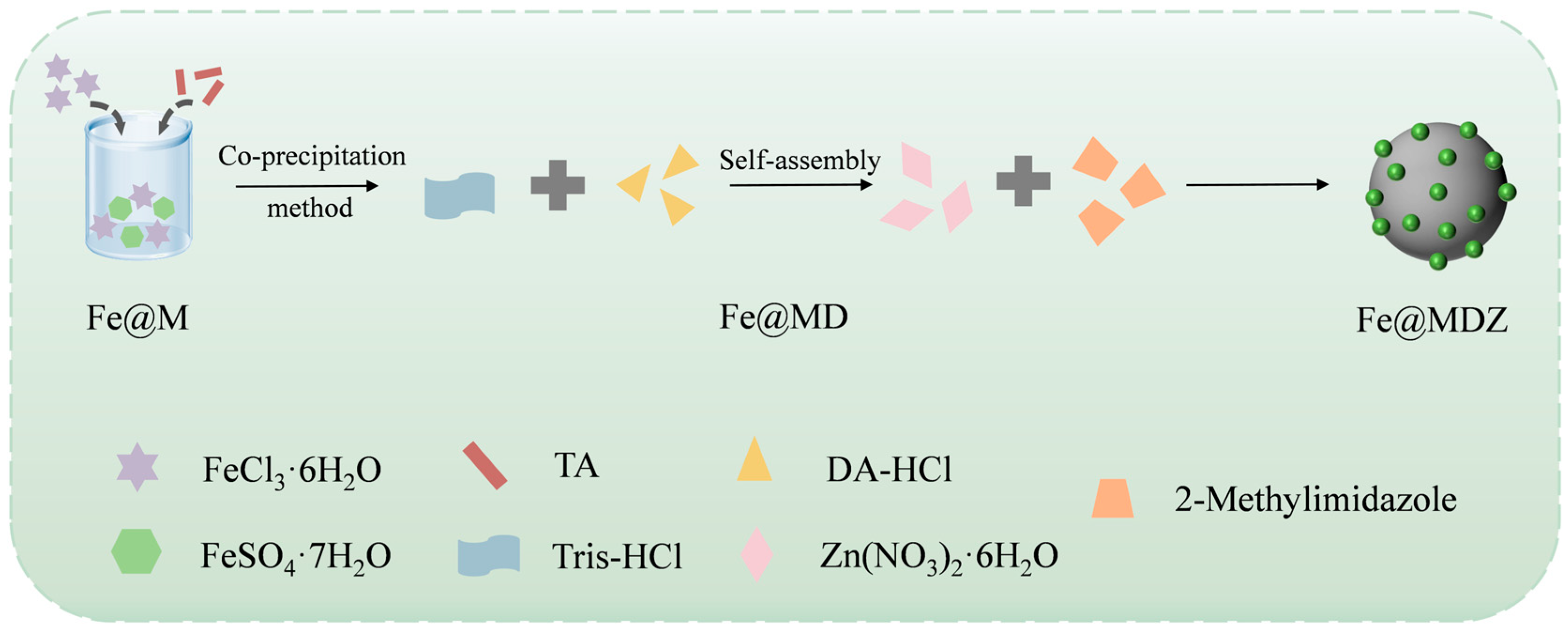

2.3. Preparation of Fe3O4@MPN

2.4. Preparation of Fe3O4@MPN@PDA

2.5. Preparation of Fe3O4@MPN@PDA@ZIF-8

2.6. Adsorption Experiment

- C0 (mg/L): the initial TBZ concentration;

- Ce (mg/L): the solution concentration at the adsorption equilibrium state;

- V (L): the volume of TBZ solution;

- m (mg): the quantity of Fe@MDZ employed.

3. Results

3.1. Characterization

3.1.1. TEM and SEM

3.1.2. XRD

3.1.3. FTIR

3.1.4. VSM

3.1.5. BET

3.1.6. XPS and ICP-OES

3.2. Adsorption Properties of Fe@MDZ

3.2.1. Identification of Pesticides and Selection of Materials

3.2.2. Effect of Initial Concentration and Adsorption Isotherm Analysis

3.2.3. Effect of Time and Analysis of Adsorption Kinetics

3.2.4. Impact of Adsorbent Dose

3.2.5. Influence of pH on Adsorption

3.2.6. Effect of Desorption Solvents and Optimization of Time

3.3. Real Samples

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tang, J.; Ma, X.; Yang, J.; Feng, D.-D.; Wang, X.-Q. Recent advances in metal–organic frameworks for pesticide detection and adsorption. Dalton Trans. 2020, 49, 14361–14372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nehra, M.; Dilbaghi, N.; Marrazza, G.; Kaushik, A.; Sonne, C.; Kim, K.-H.; Kumar, S. Emerging nanobiotechnology in agriculture for the management of pesticide residues. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 401, 123369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budetić, M.; Kopf, D.; Dandić, A.; Samardžić, M. Review of Characteristics and Analytical Methods for Determination of Thiabendazole. Molecules 2023, 28, 3926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Zuo, J.; He, X.; Mo, X.; Tong, P.; Zhang, L. Enhanced fluorescence of terbium with thiabendazole and application in determining trace amounts of terbium and thiabendazole. Talanta 2017, 162, 540–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrón-Bravo, O.G.; Hernández-Marín, J.A.; Gutiérrez-Chávez, A.J.; Franco-Robles, E.; Molina-Ochoa, J.; Cruz-Vázquez, C.R.; Ángel-Sahagún, C.A. Susceptibility of entomopathogenic nematodes to ivermectin and thiabendazole. Chemosphere 2020, 253, 126658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, J.; Hu, Y.; Grant, E.; Lu, X. Determination of thiabendazole in orange juice using an MISPE-SERS chemosensor. Food Chem. 2018, 239, 816–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, C.; Wang, L.; Hong, X.; Chen, Z. Application of MNPs/ODA-SBA-15 composites in pretreatment of organophosphorus pesticide residues in green leafy vegetables. J. Porous Mater. 2023, 31, 191–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, W.A.; Arain, M.B.; Soylak, M. Nanomaterials-based solid phase extraction and solid phase microextraction for heavy metals food toxicity. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2020, 145, 111704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Li, L.; Gao, Y.; Gao, M.; Huang, X.; Lv, J.; Xu, D. A beta-cyclodextrin-functionalized magnetic metal organic framework for efficient extraction and determination of prochloraz and triazole fungicides in vegetables samples. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2019, 183, 109546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Issa, A.A.; Al-Saad, K.A.; Luyt, A.S. Magnetic solid phase extraction for chromatographic separation of carbamates. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2017, 101, 2038–2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, C.; Fu, N.; Zhou, Z.; Wu, M.; Yang, Z.; Liu, R. Mechanochemical Synthesis of Tannic Acid-Fe Coordination Compound and Its Derived Porous Carbon for CO2 Adsorption. Energy Fuels 2018, 32, 10779–10785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Xu, X.; Wang, X.; Li, R.; Cai, C.; Sun, T.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, L.; Xu, J.; Zhao, N. General Surface Modification Method for Nanospheres via Tannic Acid-Fe Layer-by-Layer Deposition: Preparation of a Magnetic Nanocatalyst. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2019, 2, 3510–3517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, M.; Yin, S.; Meng, F.; Qi, J.; Li, X.; Cui, P.; Wang, Y.; Wang, L. Metal nanoparticles capped with plant polyphenol for oxygen reduction electrocatalysis. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2023, 641, 359–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Ai, S.; Zhou, Y.; Luo, Z.; Dai, C.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Huang, H.; Luo, S.; Luo, L. Adsorption of agricultural wastewater contaminated with antibiotics, pesticides and toxic metals by functionalized magnetic nanoparticles. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2018, 6, 6468–6478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfieri, M.L.; Weil, T.; Ng, D.Y.W.; Ball, V. Polydopamine at biological interfaces. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2022, 305, 102689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, H.; Zheng, K.; Xu, X.; Liu, X.; Zhao, B.; Ding, H.; Yu, Z.; Deng, C. Preparation of β-cyclodextrin/dopamine hydrochloride-graphene oxide and its adsorption properties for sulfonamide antibiotics. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 70192–70201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.; Chen, Z.; Li, J.; He, X.; Peng, W.; Yan, C.; Huang, G. Mussel inspired synthesis of U6N@phos-PDA composite adsorbent for the efficient separation of U(VI). J. Mol. Liq. 2024, 413, 125946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Dai, Z.; Sui, Y.; Xue, J.; Ding, D. Adsorption of U(VI) from aqueous solution by magnetic core–dual shell Fe3O4@PDA@TiO2. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 2018, 317, 613–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, A.M.; Khedr, M.H.; Farghali, A.A.; Abdallah, H.; Taha, M. High-performance metal-organic frameworks for efficient adsorption, controlled release, and membrane separation of organophosphate pesticides. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 114292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Kong, Y.; Yin, H.; Cao, M. Study on the adsorption performance of ZIF-8 on heavy metal ions in water and the recycling of waste ZIF-8 in cement. J. Solid State Chem. 2023, 326, 124217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, M.; Lin, K.-Y.A.; Oh, W.-D.; Lisak, G. Metal-organic frameworks for pesticidal persistent organic pollutants detection and adsorption—A mini review. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 413, 125325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.; Wang, R.; Hu, W.; Xu, H.; Chen, Q.; Liu, T.; Fan, Y.; Kong, Y. Preparation and performance of MOF-808 (Zr-MOF) for the efficient adsorption of phenoxyacetic acid pesticides. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2025, 143, 293–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, R.; Wu, Z. High adsorption for ofloxacin and reusability by the use of ZIF-8 for wastewater treatment. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2020, 308, 110494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.-X.; Bao, G.-M.; Zhong, Y.-F.; Zhang, L.; Zeng, K.-B.; He, J.-X.; Xiao, W.; Xia, Y.-F.; Fan, Q.; Yuan, H.-Q. Highly sensitive and rapid detection of thiabendazole residues in oranges based on a luminescent Tb3+-functionalized MOF. Food Chem. 2021, 343, 128504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, W.; Fan, R.; Zhang, J.; Zhu, K.; Gai, S.; Yin, Y.; Yang, Y. Smart MOF-on-MOF Hydrogel as a Simple Rod-shaped Core for Visual Detection and Effective Removal of Pesticides. Small 2022, 18, 2201510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kotova, A.A.; Thiebaut, D.; Vial, J.; Tissot, A.; Serre, C. Metal-organic frameworks as stationary phases for chromatography and solid phase extraction: A review. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2022, 455, 214364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelhameed, R.M.; Taha, M.; Abdel-Gawad, H.; Mahdy, F.; Hegazi, B. Zeolitic imidazolate frameworks: Experimental and molecular simulation studies for efficient capture of pesticides from wastewater. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2019, 7, 103499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Lv, Z.; Shi, L.; Jiang, T.; Sun, S.; Li, Y.; Feng, J. Fe3O4@ZIF-8@SiO2 Core–Shell Nanoparticles for the Removal of Pyrethroid Insecticides from Water. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2023, 6, 6581–6593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawn, R.; Zzaman, M.; Faizal, F.; Kiran, C.; Kumari, A.; Shahid, R.; Panatarani, C.; Joni, I.M.; Verma, V.K.; Sahoo, S.K.; et al. Origin of Magnetization in Silica-coated Fe3O4 Nanoparticles Revealed by Soft X-ray Magnetic Circular Dichroism. Braz. J. Phys. 2022, 52, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajid, M.; Shuja, S.; Rong, H.; Zhang, J. Size-controlled synthesis of Fe3O4 and Fe3O4@SiO2 nanoparticles and their superparamagnetic properties tailoring. Prog. Nat. Sci. Mater. Int. 2023, 33, 116–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabani, I.; Patil, S.A.; Tahir, M.S.; Afzal, F.; Lee, J.-W.; Im, H.; Seo, Y.-S.; Shrestha, N.K. Tunning the Zeolitic Imidazole Framework (ZIF8) through the Wet Chemical Route for the Hydrogen Evolution Reaction. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, L.; Feng, H.; Chen, N.; Mohammad, A.M. Halloysite@polydopamine/ZIF-8 Nanocomposites for Efficient Removal of Heavy Metal Ions. J. Chem. 2023, 2023, 7182712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentes-Pérez, M.; Sotelo-Lerma, M.; Fuentes-Ríos, J.L.; Morales-Espinoza, E.G.; Serrano, M.; Nicho, M.E. Synthesis and study of physicochemical properties of Fe3O4@ZnFe2O4 core/shell nanoparticles. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2021, 32, 16786–16799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, L.T.T.; Thi Le, N.H.; Thi Ta, H.K.; Dang Nguyen, K. Isolation of DNA from Arthrospira platensis and whole blood using magnetic nanoparticles (Fe3O4@OA and Fe3O4@OA@SiO2). J. Anal. Sci. Technol. 2022, 13, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, R.; Yang, P.; Ma, Y.; Bian, F. Facile Synthesis of Magnetic Hierarchical Core-Shell Structured Fe3O4@PDA-Pd@MOF Nanocomposites: Highly Integrated Multifunctional Catalysts. ChemCatChem 2018, 10, 1446–1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.U.; Noor, T.; Iqbal, N.; Zaman, N.; Hussain, Z. CO2 adsorption study of the zeolite imidazolate framework (ZIF-8) and its g-C3N4 composites. J. Mater. Sci. 2023, 58, 3947–3959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, A.; Pour, A.N. Triethylenetetramine-impregnated ZIF-8 nanoparticles for CO2 adsorption. J. CO2 Util. 2023, 69, 102424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davodi, B.; Jahangiri, M.; Ghorbani, M. Magnetic Fe3O4@polydopamine biopolymer: Synthesis, characterization and fabrication of promising nanocomposite. J. Vinyl Addit. Technol. 2018, 25, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdollahi, B.; Salari, D.; Zarei, M. Synthesis and characterization of magnetic Fe3O4@SiO2-MIL-53(Fe) metal-organic framework and its application for efficient removal of arsenate from surface and groundwater. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 107144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Wu, J. comprehensive analysis of the BET area for nanoporous materials. AIChE J. 2017, 64, 286–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Bai, T.; Yi, X.; Zhao, K.; Shi, W.; Dai, F.; Wei, J.; Wang, J.; Shi, C. Polypropylene fiber grafted calcium alginate with mesoporous silica for adsorption of Bisphenol A and Pb2+. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 238, 124131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mergbi, M.; Aboagye, D.; Contreras, S.; Amor, H.B.; Medina, F.; Djellabi, R. Fast g-C3N4 sonocoated activated carbon for enhanced solar photocatalytic oxidation of organic pollutants through Adsorb & Shuttle process. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2023, 99, 106550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, M.; Xu, D.; Gao, Y.; Chen, G.; Zhai, R.; Huang, X.; Xu, X.; Wang, J.; Yang, X.; Liu, G. Mussel-inspired triple bionic adsorbent: Facile preparation of layered double hydroxide@polydopamine@metal-polyphenol networks and their selective adsorption of dyes in single and binary systems. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 420, 126609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chidiebere, M.A.; Anadebe, V.C.; Barik, R.C. Assessment of the inhibition performance of ZIF-8 on corrosion Mitigation of API 5L X65 steel in 3.5 wt% NaCl: Experimental and theoretical insight. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2024, 33, 2879–2898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Dai, X.; Zhan, Y.; Ding, X.; Wang, M.; Wang, X. In situ growth of ZIF-8 nanoparticles on chitosan to form the hybrid nanocomposites for high-efficiency removal of Congo Red. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 137, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, K.; Yang, J.; Dou, M.; Gu, P.; Su, H.; Huang, F. Attachment of Fe3O4 nanoparticles on UiO-66: A stable composite for efficient sorption and reduction of selenite from water. J. Saudi Chem. Soc. 2023, 27, 101678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, K.; Nde, D.T.; Khan, R.A.; Raza, W. Fabrication of Zeolitic imidazolate framework-8 (ZIF-8) modified screen-printed electrode and its catalytic role for the electrochemical determination of biological molecule (dopamine). Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2024, 699, 134606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalsoom; Ali, A.; Khan, S.; Ali, N.; Khan, M.A. Enhanced ultrasonic adsorption of pesticides onto the optimized surface area of activated carbon and biochar: Adsorption isotherm, kinetics, and thermodynamics. Biomass Convers. Biorefinery 2023, 14, 15519–15534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrefaee, S.H.; Aljohani, M.; Alkhamis, K.; Shaaban, F.; El-Desouky, M.G.; El-Bindary, A.A.; El-Bindary, M.A. Adsorption and effective removal of organophosphorus pesticides from aqueous solution via novel metal-organic framework: Adsorption isotherms, kinetics, and optimization via Box-Behnken design. J. Mol. Liq. 2023, 384, 122206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debnath, S.; Das, R. Strong adsorption of CV dye by Ni ferrite nanoparticles for waste water purification: Fits well the pseudo second order kinetic and Freundlich isotherm model. Ceram. Int. 2023, 49, 16199–16215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanta, P.; Kasemwong, K.; Skolpap, W. Isotherm and kinetic modeling on superparamagnetic nanoparticles adsorption of polysaccharide. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2018, 6, 794–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vareda, J.P. On validity, physical meaning, mechanism insights and regression of adsorption kinetic models. J. Mol. Liq. 2023, 376, 121416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahat, A.; Kubra, K.T.; El-marghany, A. Equilibrium, thermodynamic and kinetic modeling of triclosan adsorption on mesoporous carbon nanosphere Optimization using Box-Behnken design. J. Mol. Liq. 2023, 383, 122166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansouriieh, N.; Sohrabi, M.R.; Khosravi, M. Adsorption kinetics and thermodynamics of organophosphorus profenofos pesticide onto Fe/Ni bimetallic nanoparticles. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 13, 1393–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kebede Gurmessa, B.; Taddesse, A.M.; Teju, E. UiO-66 (Zr-MOF): Synthesis, Characterization, and Application for the Removal of Malathion and 2, 4-D from Aqueous Solution. Environ. Pollut. Bioavailab. 2023, 35, 2222910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Q.-W.; Sun, H.; Wang, K.; He, H.-B.; Feng, Y.-Q. Monitoring of Carbendazim and Thiabendazole in Fruits and Vegetables by SiO2@NiO-Based Solid-Phase Extraction Coupled to High-Performance Liquid Chromatography-Fluorescence Detector. Food Anal. Methods 2017, 10, 2892–2901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, D.; Hu, X.; Fu, X.; Xia, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Peng, L.; Yu, Q.; Peng, X. Flowerlike Ni–NiO composite as magnetic solid-phase extraction sorbent for analysis of carbendazim and thiabendazole in edible vegetable oils by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry. Food Chem. 2022, 374, 131761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rizzato, M.L.; Picone, A.L.; Romano, R.M. A facile method for in-situ detection of thiabendazole residues in fruit and vegetable peels using Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy. Talanta Open 2023, 7, 100223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altunay, N.; Ülüzger, D.; Gürkan, R. Simple and fast spectrophotometric determination of low levels of thiabendazole residues in fruit and vegetables after pre-concentration with ionic liquid phase microextraction. Food Addit. Contam. Part A 2018, 35, 1139–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gamba, M.; Olivelli, M.; Lázaro-Martínez, J.M.; Gaddi, G.; Curutchet, G.; Sánchez, R.M.T. Thiabendazole adsorption on montmorillonite, octadecyltrimethylammonium- and Acremonium sp.-loaded products and their copper complexes. Chem. Eng. J. 2017, 320, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Wang, C.; Li, N.; Tang, B.; Zhu, T. Study on Adsorption of Two Functionalized Conjugated Microporous Polymers: Extraction of Carbendazim and Thiabendazole in Ophiopogon japonicus. J. Sep. Sci. 2025, 48, e70185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Luo, T.; Yan, W.; Cheng, T.; Cheng, K.; Yu, L.; Cao, J.; Yang, Z. Adsorption Behavior and Adsorption Dynamics of Micrometer-Sized Polymer Microspheres on the Surface of Quartz Sand. Processes 2023, 11, 1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radoor, S.; Karayil, J.; Parameswaranpillai, J.; Siengchin, S. Removal of anionic dye Congo red from aqueous environment using polyvinyl alcohol/sodium alginate/ZSM-5 zeolite membrane. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 15452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajith, A.; Gowthaman, N.S.K.; John, S.A.; Elango, K.P. Direct Adsorption of Graphene Oxide on a Glassy Carbon Electrode: An Investigation of Its Adsorption and Electrochemical Activity. Langmuir 2023, 39, 9990–10000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sodkouieh, S.M.; Kalantari, M.; Shamspur, T. Methylene blue adsorption by wheat straw-based adsorbents: Study of adsorption kinetics and isotherms. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 2023, 40, 873–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Material | Surface Area (m2/g) | Pore Volume (cm3/g) | Pore Size (nm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| ZIF-8 | 276.996 | 0.168 | 2.428 |

| Fe@MD | 93.807 | 0.233 | 9.947 |

| Fe@MDZ | 229.254 | 0.238 | 4.154 |

| Materials | Element | Content (mg/kg) | Wt.% |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fe3O4 | Fe | 657,419.0 | 65.74 |

| Fe@M | Fe | 647,209.6 | 64.72 |

| Fe@MD | Fe | 588,628.8 | 58.86 |

| Fe@MDZ | Fe | 451,265.8 | 45.13 |

| Zn | 65,886.1 | 6.59 |

| Pesticide | Langmuir Equation | Freundlich Equation | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Qm (mg/g) | KL (L/mg) | R2 | RL | KF (L/mg) | n | R2 | |

| TBZ | 1.23 | 0.07 | 0.995 | 0.88 | 0.80 | 1.39 | 0.987 |

| Pseudo-First-Order Model | Pseudo-Second-Order Model | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| K1 (1/min) | Qe,exp (mg/g) | Qe,cal (mg/g) | R2 | K2 (1/min) | Qe,cal (mg/g) | R2 | |

| TBZ | 0.014 | 1.36 | 0.16 | 0.66 | 0.673 | 1.33 | 0.99 |

| Sample | Method | Detection Technology | LOD | R2 | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Apple | Solid phase extraction | HPLC-FLD | 7.5 ng/g | 0.9998 | [56] |

| Edible oil | Magnetic solid phase extraction | UHPLC-MS/MS | 0.001 mg/kg | 0.9957 | [57] |

| Apple peel | Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy | / | 0.20 g/cm2 | / | [58] |

| Pear peel | 40 ng/cm2 | ||||

| Fruits and vegetables | Ionic liquid phase microextraction | Spectrophotometry | 0.1, 0.24 μg/L | 0.998–0.975 | [59] |

| Wastewater | / | HPLC | 0.0045 mg/L | 0.999 | [60] |

| Ophiopogonis japonicus | Pipette-tip solid-phase extraction | HPLC-UV | 0.004 µg/g | 0.999 | [61] |

| Tomato and Chinese cabbage | Magnetic solid phase extraction | HPLC-MS/MS | 0.5 μg/L | 0.9914 | This work |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, M.; Zhao, X.; Lin, Z.; Yu, H.; Huang, Y.; Jiao, B.; Zhou, J.; Chen, G.; Liu, G.; Qin, L.; et al. Coral-like Magnetic Metal–Organic Framework for Selective Adsorption and Detection of Thiabendazole in Tomato and Chinese Cabbage Samples. Foods 2025, 14, 3748. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14213748

Wang M, Zhao X, Lin Z, Yu H, Huang Y, Jiao B, Zhou J, Chen G, Liu G, Qin L, et al. Coral-like Magnetic Metal–Organic Framework for Selective Adsorption and Detection of Thiabendazole in Tomato and Chinese Cabbage Samples. Foods. 2025; 14(21):3748. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14213748

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Miao, Xijuan Zhao, Zhihao Lin, Hailong Yu, Yanyan Huang, Bining Jiao, Jie Zhou, Ge Chen, Guangyang Liu, Lin Qin, and et al. 2025. "Coral-like Magnetic Metal–Organic Framework for Selective Adsorption and Detection of Thiabendazole in Tomato and Chinese Cabbage Samples" Foods 14, no. 21: 3748. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14213748

APA StyleWang, M., Zhao, X., Lin, Z., Yu, H., Huang, Y., Jiao, B., Zhou, J., Chen, G., Liu, G., Qin, L., Liu, X., & Xu, D. (2025). Coral-like Magnetic Metal–Organic Framework for Selective Adsorption and Detection of Thiabendazole in Tomato and Chinese Cabbage Samples. Foods, 14(21), 3748. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14213748