Effect of Transglutaminase-Mediated Cross-Linking on Physicochemical Properties and Structural Modifications of Rice Dreg Protein

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Material

2.2. Extraction and Cross-Linking of RDP

2.3. Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate-Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE)

2.4. Structural Characteristics of Cross-Linked RDP

2.4.1. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) Analysis

2.4.2. Intrinsic Emission Fluorescence Spectroscopy

2.4.3. Determination of Sulfhydryl Groups

2.5. Determination of Functional Properties

2.5.1. Determination of Solubility

2.5.2. Determination of Emulsifying Activity and Emulsion Stability

2.5.3. Water/Oil Holding Capacity (WHC/OHC)

2.5.4. Determination of Surface Hydrophobicity

2.6. Determination of Rheological Properties

2.6.1. Apparent Viscosity

2.6.2. Dynamic Oscillation Rheology

2.7. Digestibility In Vitro

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

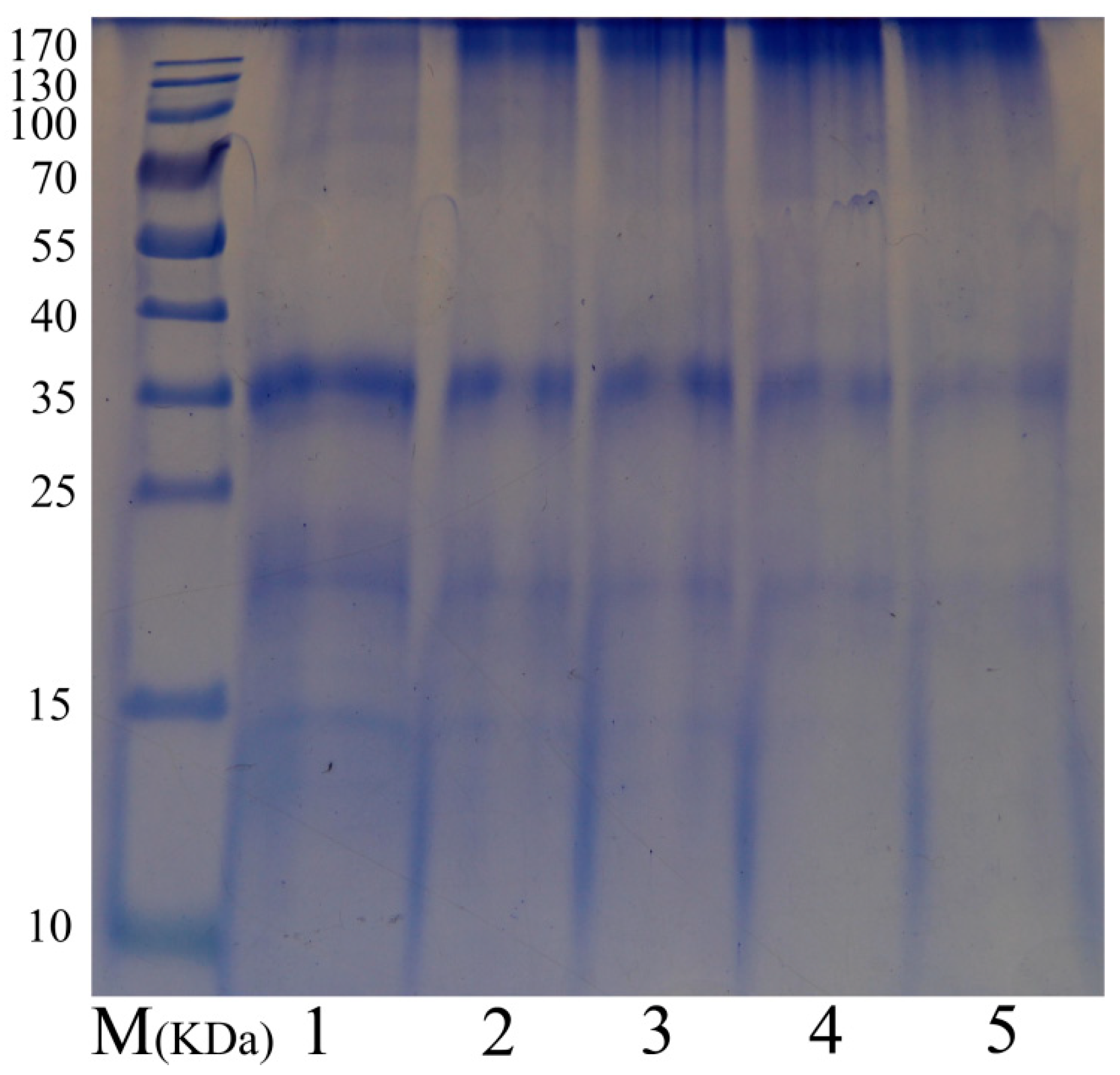

3.1. SDS–PAGE Analysis

3.2. Structural Characteristics of the Cross-Linked RDP

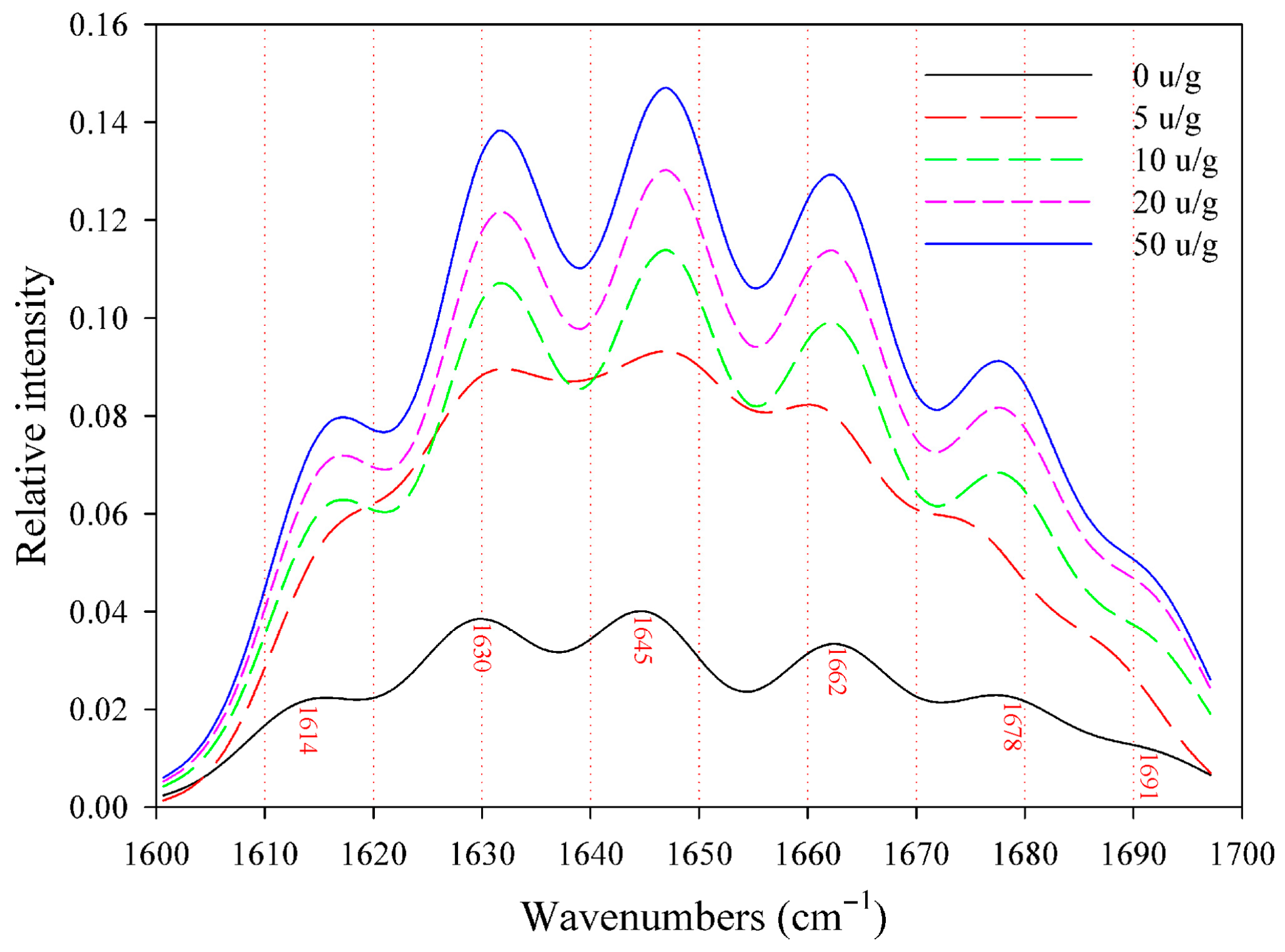

3.2.1. FTIR Spectroscopy

3.2.2. Intrinsic Emission Fluorescence Spectra

3.2.3. Sulfhydryl Groups (-SH) Contents

3.3. Protein Functional Properties

3.3.1. Solubility

3.3.2. Emulsifying Activity and Emulsion Stability

3.3.3. Water/Oil Holding Capacity

3.3.4. Surface Hydrophobicity

3.4. Rheological Properties

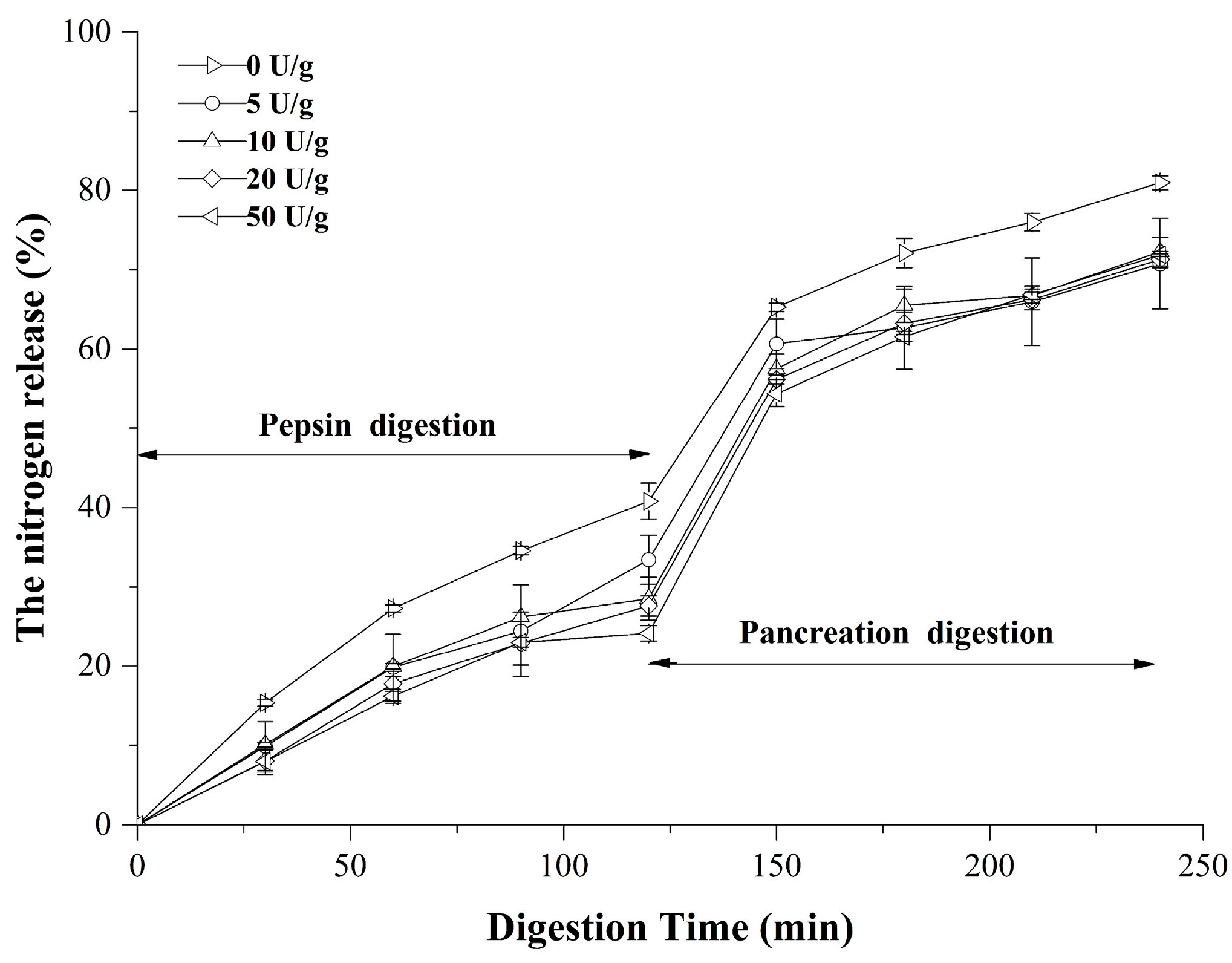

3.5. In Vitro Digestibility

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Olatunde, O.O.; Owolabi, I.O.; Fadairo, O.S.; Ghosal, A.; Coker, O.J.; Soladoye, O.P.; Aluko, R.E.; Bandara, N. Enzymatic Modification of Plant Proteins for Improved Functional and Bioactive Properties. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2023, 16, 1216–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Q.; Lu, W.; Wang, R.; Hu, J.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, H.; Zhou, N.; Xiong, Q. Lipidomic Analysis of Grain Quality Variation in High Quality Aromatic Japonica Rice. Food Chem. X 2024, 22, 101473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, W.; Shi, W.; Xie, H.; Wang, S.; Zhang, Q.; Ouyang, K.; Xiao, F.; Zhao, Q. Non-Covalent Interaction of Rice Protein and Polyphenols: The Effects on Their Emulsions. Food Chem. 2025, 479, 143732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Wang, S.; Xie, H.; Ouyang, K.; Wang, C.; Yang, Y.; Xiong, H.; Zhao, Q. Improving the Functional Properties of Rice Glutelin: Impact of Succinic Anhydride Modification. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 59, 2739–2750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Shi, S.; Jiang, Y.; Xiong, H.; Woo, M.W.; Zhao, Q.; Bai, C.; Zhou, Q.; Sun, W. Physicochemical Properties and Emulsion Stabilization of Rice Dreg Glutelin Conjugated with κ-Carrageenan through Maillard Reaction. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2013, 93, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, L.; Chen, F.; Yang, Y.; Li, Q.; Fan, X.; Zhao, D.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, C. The Underlying Starch Structures of Rice Grains with Different Digestibilities but Similarly High Amylose Contents. Food Chem. 2022, 379, 132071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Selomulya, C.; Xiong, H.; Chen, X.D.; Ruan, X.; Wang, S.; Xie, J.; Peng, H.; Sun, W.; Zhou, Q. Comparison of Functional and Structural Properties of Native and Industrial Process-Modified Proteins from Long-Grain Indica Rice. J. Cereal Sci. 2012, 56, 568–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xin, Q.; Miao, Y.; Zeng, X.; Li, H.; Shan, K.; Nian, Y.; Zhao, D.; Wu, J.; Li, C. Interplay between Transglutaminase Treatment and Changes in Digestibility of Dietary Proteins. Food Chem. 2022, 373, 131446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Yuan, Z.; Zou, X.; Ji, Y.; Hou, J.; Zhang, J.; Lu, F.; Liu, Y. Crosslinking Mechanism on a Novel Bacillus Cereus Transglutaminase-Mediated Conjugation of Food Proteins. Foods 2022, 11, 3722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahid, A.; Haq, M.A.; Hussain, N.; Nawaz, H.; Xu, J. Impact of Deep Eutectic Solvent Deamidation on the Solubility and Conformation of Rice Dreg Protein Isolate. Cereal Chem. 2025, 102, 80–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlangen, M.; Ribberink, M.A.; Taghian Dinani, S.; Sagis, L.M.C.; van der Goot, A.J. Mechanical and Rheological Effects of Transglutaminase Treatment on Dense Plant Protein Blends. Food Hydrocoll. 2023, 136, 108261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babiker, E.E. Effect of Transglutaminase Treatment on the Functional Properties of Native and Chymotrypsin-Digested Soy Protein. Food Chem. 2000, 70, 139–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Kee, J.I.; Lee, S.; Yoo, S.-H. Quality Improvement of Rice Noodle Restructured with Rice Protein Isolate and Transglutaminase. Food Chem. 2014, 145, 409–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Chen, X.; Cai, X.; Wang, S. Lipid-Lowering Activity and Underlying Mechanism of Glycosylated Peptide–Calcium Chelate Prepared by Transglutaminase Pathway. Food Front. 2024, 5, 160–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; Wang, C.; Wu, Z.; Yu, B.; Yu, X.; Li, C.; Cao, Y.; Yuan, C.; Zhang, Z.; Zhao, H.; et al. Structural and Gelation Properties of Soy Protein Isolates-Sesbania Gum Gels: Effects of Ultrasonic Pretreatment and CaSO4 Concentration. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 310, 143215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wen, Z.; Sun, J.; Lu, Y.; Roopesh, M.S.; Cui, L.; Pan, D.; Du, L. Cold Argon Plasma-Modified Pea Protein Isolate: A Strategy to Enhance Ink Performance and Digestibility in 3D-Printed Plant-Based Meat. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 311, 144049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.-X.; Li, Y.-Q.; Sun, G.-J.; Wang, C.-Y.; Liang, Y.; Hua, D.-L.; Chen, L.; Mo, H.-Z. Effect of Transglutaminase on Structure and Gelation Properties of Mung Bean Protein Gel. Food Biophys. 2023, 18, 421–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moguiliansky, S.; Friedman, N.; Davidovich-Pinhas, M. The Effect of Transglutaminase on the Structure and Texture of Plant-Protein Based Bigel. Food Hydrocoll. 2025, 162, 110981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Li, T.; Chen, Q.; Liu, H.; Kaplan, D.L.; Wang, Q. Application of Transglutaminase Modifications for Improving Protein Fibrous Structures from Different Sources by High-Moisture Extruding. Food Res. Int. 2023, 166, 112623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Zhang, J.; Hu, A.; Guo, F.; Zhou, H.; Wang, Q. Effect of Transglutaminase and Laccase on Pea Protein Gel Properties Compared to That of Soybean. Food Hydrocoll. 2024, 156, 110314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udomrati, S.; Pantoa, T.; Sorndech, W.; Ploypetchara, T. Investigation of Transglutaminase Incubated Condition on Crosslink and Rheological Properties of Soy Protein Isolate, and Their Effects in Plant-Based Patty Application. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2024, 18, 8811–8824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Lan, D.; Wang, W.; Zhang, W.; Wang, Y. Effect of Transglutaminase-Catalyzed Crosslinking Behavior on the Quality Characteristics of Plant-Based Burger Patties: A Comparative Study with Methylcellulose. Food Chem. 2023, 428, 136754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.-D.; Li, L.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, Y.-Q.; Liu, Y.; Yan, J.-N.; Lai, B.; Wang, C.; Wu, H.-T. Impact of Plant and Animal Proteins with Transglutaminase on the Gelation Properties of Clam Meretrix Meretrix Surimi. Food Biosci. 2024, 61, 104915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, F.; Gu, Q.; Liu, L.; Xu, T.; Li, L.; Yang, Q.; Lv, L. Study on the Allergenicity and Gel Properties of Transglutaminase Cross-Linked Shrimp Myofibrillar Protein. Food Chem. 2025, 488, 144910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.-J.; Zhao, X.-H. Transglutaminase-Induced Cross-Linking and Glucosamine Conjugation in Soybean Protein Isolates and Its Impacts on Some Functional Properties of the Products. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2010, 231, 679–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhao, H.; Wang, H.; Xu, P.; Chen, M.; Xu, Z.; Wen, L.; Cui, B.; Yu, B.; Zhao, H.; et al. Preparation of High-Solubility Rice Protein Using an Ultrasound-Assisted Glycation Reaction. Food Res. Int. 2022, 161, 111737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, A.; Li, L. Effects of Ultrasound Pretreatment on Functional Property, Antioxidant Activity, and Digestibility of Soy Protein Isolate Nanofibrils. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2022, 90, 106193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Zhou, J.; Wu, Q.; Zhang, X.; Chen, Z.; Wang, L. Modifying Functional Properties of Food Amyloid-Based Nanostructures from Rice Glutelin. Food Chem. 2023, 398, 133798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ince, C.; Condict, L.; Ashton, J.; Stockmann, R.; Kasapis, S. Molecular Characterisation of Interactions between β-Lactoglobulin and Hexanal—An off Flavour Compound. Food Hydrocoll. 2024, 146, 109260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, C.-L.; Zhao, X.-H. Structure and Property Modification of an Oligochitosan-Glycosylated and Crosslinked Soybean Protein Generated by Microbial Transglutaminase. Food Chem. 2014, 163, 114–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Xiong, H.; Selomulya, C.; Chen, X.D.; Huang, S.; Ruan, X.; Zhou, Q.; Sun, W. Effects of Spray Drying and Freeze Drying on the Properties of Protein Isolate from Rice Dreg Protein. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2013, 6, 1759–1769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Espinosa, M.E.; Guevara-Oquendo, V.H.; He, J.; Zhang, W.; Yu, P. Research Updates and Progress on Nutritional Significance of the Amides I and II, Alpha-Helix and Beta-Sheet Ratios, Microbial Protein Synthesis, and Steam Pressure Toasting Condition with Globar and Synchrotron Molecular Microspectroscopic Techniques with Chemometrics. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2025, 65, 367–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korićanac, M.; Mijalković, J.; Petrović, P.; Pavlović, N.; Knežević-Jugović, Z. Exploring Green Proteins from Pumpkin Leaf Biomass: Assessing Their Potential as a Novel Alternative Protein Source and Functional Alterations via pH-Shift Treatment. Bioresour. Bioprocess. 2025, 12, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Zhao, M.; Sun, W.; Zhao, G.; Ren, J. Effects of Microfluidization Treatment and Transglutaminase Cross-Linking on Physicochemical, Functional, and Conformational Properties of Peanut Protein Isolate. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2011, 59, 8886–8894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, Z.; Yang, S.; Cheng, L.; Liao, P.; Dai, S.; Tong, X.; Tian, T.; Wang, H.; Jiang, L. Emulsifying Properties and Oil–Water Interface Properties of Succinylated Soy Protein Isolate: Affected by Conformational Flexibility of the Interfacial Protein. Food Hydrocoll. 2023, 136, 108224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, M.; Liao, L.; Zhang, X.; Chen, X.; Peng, S.; Zou, L.; Liang, R.; Liu, W. Electric Field-Driven Fabrication of Anisotropic Hydrogels from Plant Proteins: Microstructure, Gel Performance and Formation Mechanism. Food Hydrocoll. 2023, 136, 108297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alabi, O.O.; Annor, G.A.; Amonsou, E.O. Effect of Cold Plasma-Activated Water on the Physicochemical and Functional Properties of Bambara Groundnut Globulin. Food Struct. 2023, 36, 100321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorinstein, S.; Goshev, I.; Moncheva, S.; Zemser, M.; Weisz, M.; Caspi, A.; Libman, I.; Lerner, H.T.; Trakhtenberg, S.; Martín-Belloso, O. Intrinsic Tryptophan Fluorescence of Human Serum Proteins and Related Conformational Changes. J. Protein Chem. 2000, 19, 637–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.-J.; Zhao, X.-H. Transglutaminase-Induced Cross-Linking and Glucosamine Conjugation of Casein and Some Functional Properties of the Modified Product. Int. Dairy J. 2011, 21, 198–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Z.-L.; Yao, P.-L.; Xie, J.-J.; Li, Y.-P.; Ma, H.-J. Effects of Low-Frequency Magnetic Field on Solubility, Structural and Functional Properties of Soy 11S Globulin. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2024, 104, 5944–5954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.-H.; Sun, X.; Yin, S.-W.; Ma, C.-Y. Transglutaminase-Induced Cross-Linking of Vicilin-Rich Kidney Protein Isolate: Influence on the Functional Properties and in Vitro Digestibility. Food Res. Int. 2008, 41, 941–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanqa, N.; Mshayisa, V.V.; Basitere, M. Proximate, Physicochemical, Techno-Functional and Antioxidant Properties of Three Edible Insect (Gonimbrasia belina, Hermetia illucens and Macrotermes subhylanus) Flours. Foods 2022, 11, 976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutzli, I.; Weiss, J.; Gibis, M. Glycation of Plant Proteins via Maillard Reaction: Reaction Chemistry, Technofunctional Properties, and Potential Food Application. Foods 2021, 10, 376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelraheem, A.N.; Hashim, A.S.; Ahmed, M.E. Changes in Functional Properties by Transglutaminase Cross Linking as a Function of pH of Legumes Protein Isolate. Innov. Rom. Food Biotechnol. 2010, 7, 12–20. Available online: https://www.gup.ugal.ro/ugaljournals/index.php/IFRB/article/view/3354. (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Yao, X.-N.; Dong, R.-L.; Li, Y.-C.; Lv, A.-J.; Zeng, L.-T.; Li, X.-Q.; Lin, Z.; Qi, J.; Zhang, C.-H.; Xiong, G.-Y.; et al. pH-Shifting Treatment Improved the Emulsifying Ability of Gelatin under Low-Energy Emulsification. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 282, 136979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, C.; Zhao, J.; Wang, L.; Jiang, J. Modified Pea Protein Coupled with Transglutaminase Reduces Phosphate Usage in Low Salt Myofibrillar Gel. Food Hydrocoll. 2023, 139, 108577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, F.; Chiu, I.; Li, D.; Wu, X.; Yang, T.; Gao, Y.; Zheng, H. Physicochemical Modulation of Soy-Hemp-Wheat Protein Meat Analogues Prepared by High-Moisture Extrusion Using Transglutaminase. Food Res. Int. 2025, 208, 116229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.; Yang, X.-Q.; Chen, Z.; Wu, H.; Peng, Z.-Y. Physicochemical and Structural Characteristics of Sodium Caseinate Biopolymers Induced by Microbial Transglutaminase. J. Food Biochem. 2005, 29, 402–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiller, B.; Lorenzen, P.C. Functional Properties of Milk Proteins as Affected by Enzymatic Oligomerisation. Food Res. Int. 2009, 42, 899–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velazquez-Dominguez, A.; Hennetier, M.; Abdallah, M.; Hiolle, M.; Violleau, F.; Delaplace, G.; Peres De Sa Peixoto, P. Influence of Enzymatic Cross-Linking on the Apparent Viscosity and Molecular Characteristics of Casein Micelles at Neutral and Acidic pH. Food Hydrocoll. 2023, 139, 108552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dash, D.R.; Singh, S.K.; Singha, P. Viscoelastic Behavior, Gelation Properties and Structural Characterization of Deccan Hemp Seed (Hibiscus cannabinus) Protein: Influence of Protein and Ionic Concentrations, pH, and Temperature. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 263, 130120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spotti, M.J.; Martinez, M.J.; Pilosof, A.M.R.; Candioti, M.; Rubiolo, A.C.; Carrara, C.R. Rheological Properties of Whey Protein and Dextran Conjugates at Different Reaction Times. Food Hydrocoll. 2014, 38, 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, G.; Chen, W.; Wang, Z.; Chu, X.; Zeng, M.; He, Z.; Goff, H.D.; Chen, J. Hydrogel Structure of Soy Protein and Gelatin Dual Network Based on TGase Cross-Linking. Food Hydrocoll. 2025, 162, 110990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cain, R.L.; Webb, I.K. Comparison of Partially Denatured Cytochrome c Structural Ensembles in Solution and Gas Phases Using Cross-Linking Mass Spectrometry. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2025, 36, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamiloglu, S.; Tomas, M.; Ozkan, G.; Ozdal, T.; Capanoglu, E. In Vitro Digestibility of Plant Proteins: Strategies for Improvement and Health Implications. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2024, 57, 101148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.-H.; Li, L.; Yang, X.-Q. Influence of Transglutaminase-Induced Cross-Linking on in Vitro Digestibility of Soy Protein Isolate. J. Food Biochem. 2006, 30, 718–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Samples | β-Sheet (%) | β-Turn (%) | Random Coil (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Without TG | 49.53 | 24.78 | 23.40 |

| +TG, 5 U/g | 49.34 | 25.16 | 23.30 |

| +TG, 10 U/g | 48.60 | 25.84 | 23.63 |

| +TG, 20 U/g | 48.58 | 26.22 | 23.33 |

| +TG, 50 U/g | 48.56 | 25.26 | 23.46 |

| Index | Without TG | +TG, 5 U/g | +TG, 10 U/g | +TG, 20 U/g | +TG, 50 U/g |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total-SH (μmol/g) | 5.00 ± 0.04 a | 1.12 ± 0.01 c | 1.26 ± 0.01 b | 1.26 ± 0.01 b | 1.22 ± 0.04 b |

| Free-SH (μmol/g) | 3.33 ± 0.01 a | 0.80 ± 0.03 b | 0.57 ± 0.03 d | 0.46 ± 0.01 e | 0.67 ± 0.02 c |

| EAI (m2/g) | 5.91 ± 0.03 a | 8.07 ± 0.04 b | 10.72 ± 0.06 c | 10.46 ± 0.06 d | 10.09 ± 0.04 e |

| ESI (%) | 76.0 ± 1.5 a | 96.15 ± 3.15 b | 98.04 ± 0.08 bc | 99.89 ± 0.42 c | 99.89 ± 0.48 c |

| WHC (g/g) | 5.16 ± 0.09 a | 4.36 ± 0.04 b | 4.18 ± 0.68 c | 4.36 ± 0.12 d | 4.51 ± 0.16 d |

| OHC (g/g) | 4.30 ± 0.07 a | 5.15 ± 0.15 b | 6.82 ± 0.15 c | 7.177 ± 0.15 d | 7.09 ± 0.18 d |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, X.; Zhu, X.; Ning, F.; Wang, S.; Zhao, Q. Effect of Transglutaminase-Mediated Cross-Linking on Physicochemical Properties and Structural Modifications of Rice Dreg Protein. Foods 2025, 14, 3719. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14213719

Chen X, Zhu X, Ning F, Wang S, Zhao Q. Effect of Transglutaminase-Mediated Cross-Linking on Physicochemical Properties and Structural Modifications of Rice Dreg Protein. Foods. 2025; 14(21):3719. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14213719

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Xianxin, Xiaoyan Zhu, Fangjian Ning, Songyu Wang, and Qiang Zhao. 2025. "Effect of Transglutaminase-Mediated Cross-Linking on Physicochemical Properties and Structural Modifications of Rice Dreg Protein" Foods 14, no. 21: 3719. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14213719

APA StyleChen, X., Zhu, X., Ning, F., Wang, S., & Zhao, Q. (2025). Effect of Transglutaminase-Mediated Cross-Linking on Physicochemical Properties and Structural Modifications of Rice Dreg Protein. Foods, 14(21), 3719. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14213719