Hybrid Crude Palm Oil in Brazilian Regions: Evaluation of Knowledge, Perceptions, and Consumption Potential

Abstract

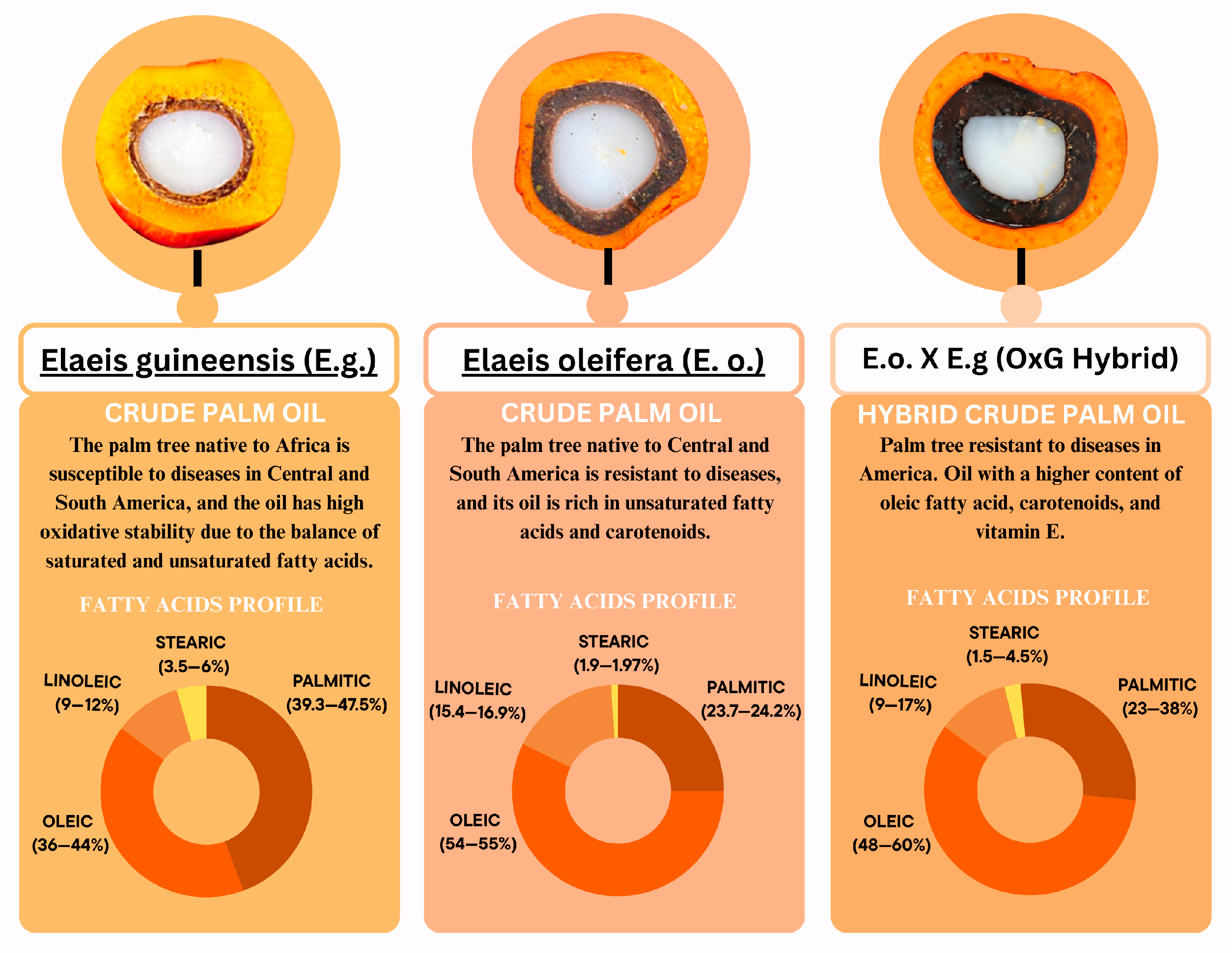

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Consumer Profile

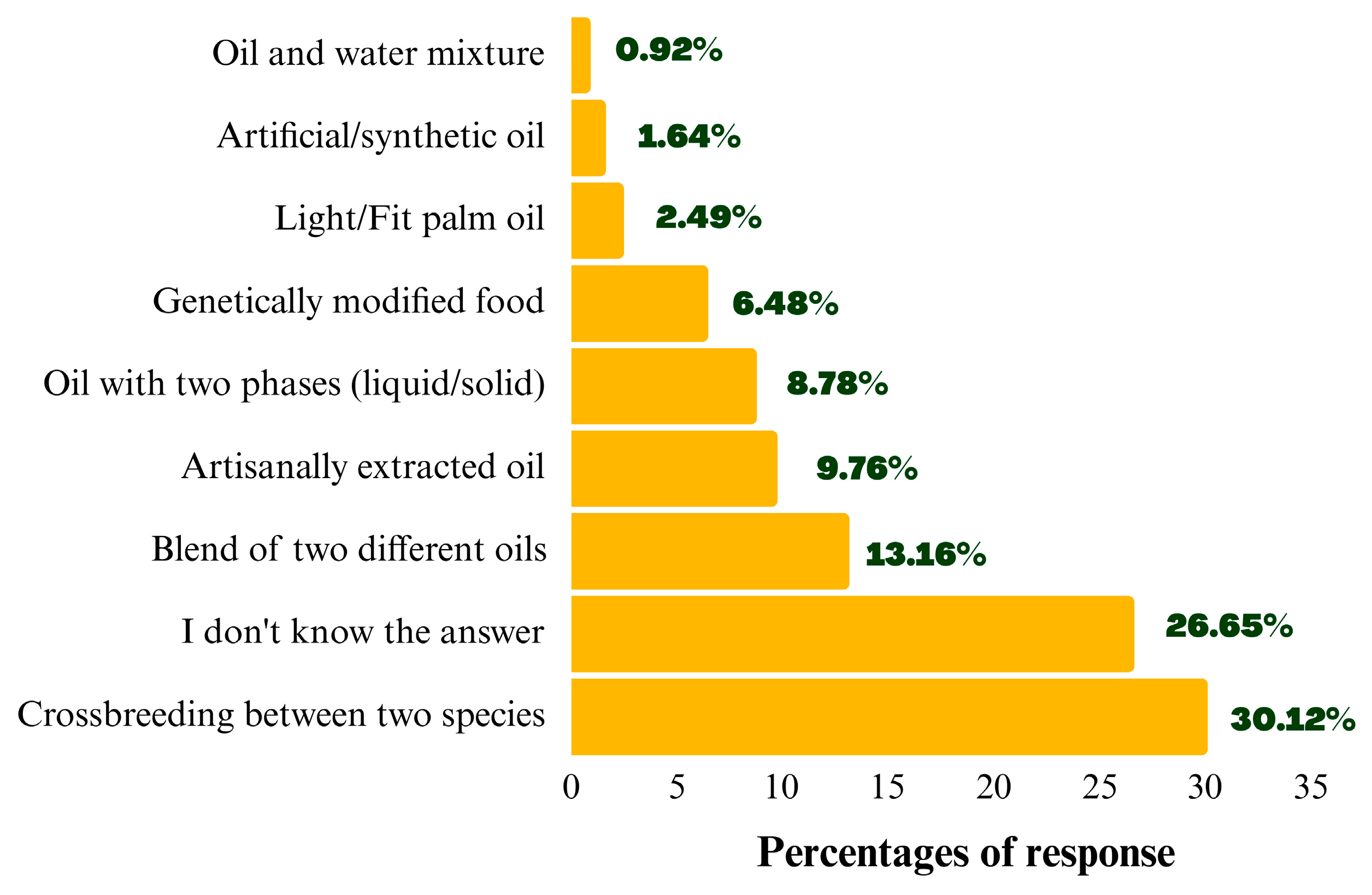

3.2. Knowledge of Hybrid Crude Palm Oil

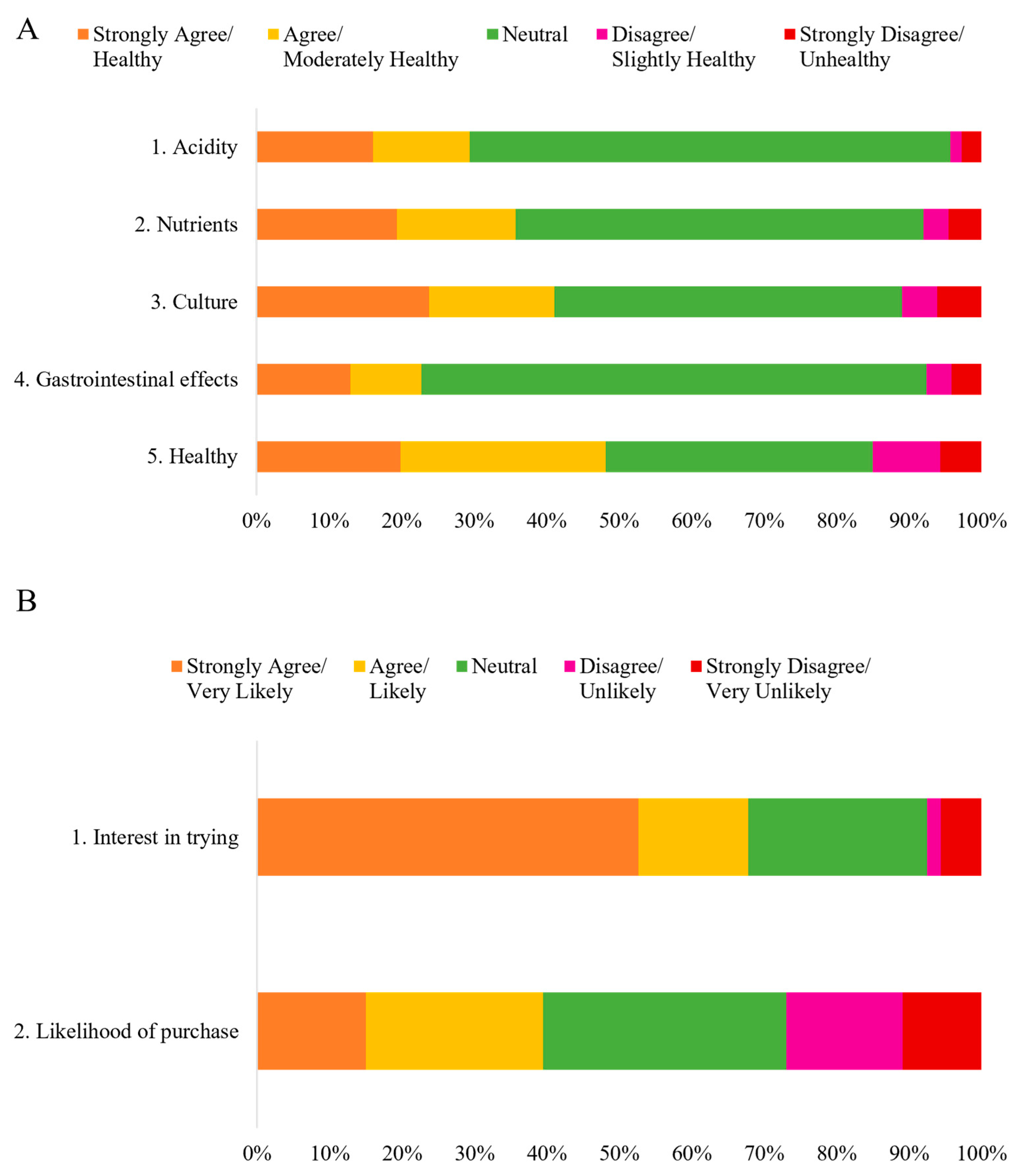

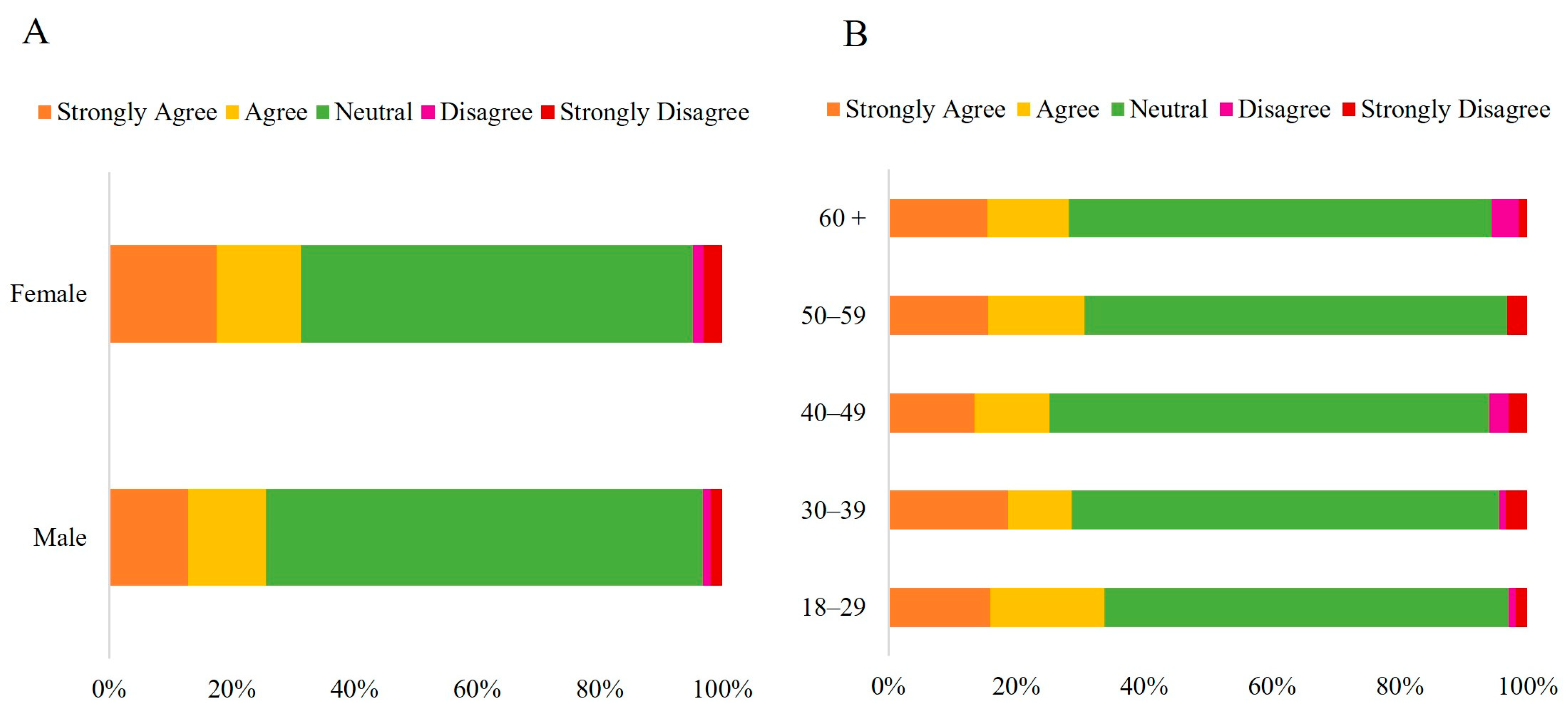

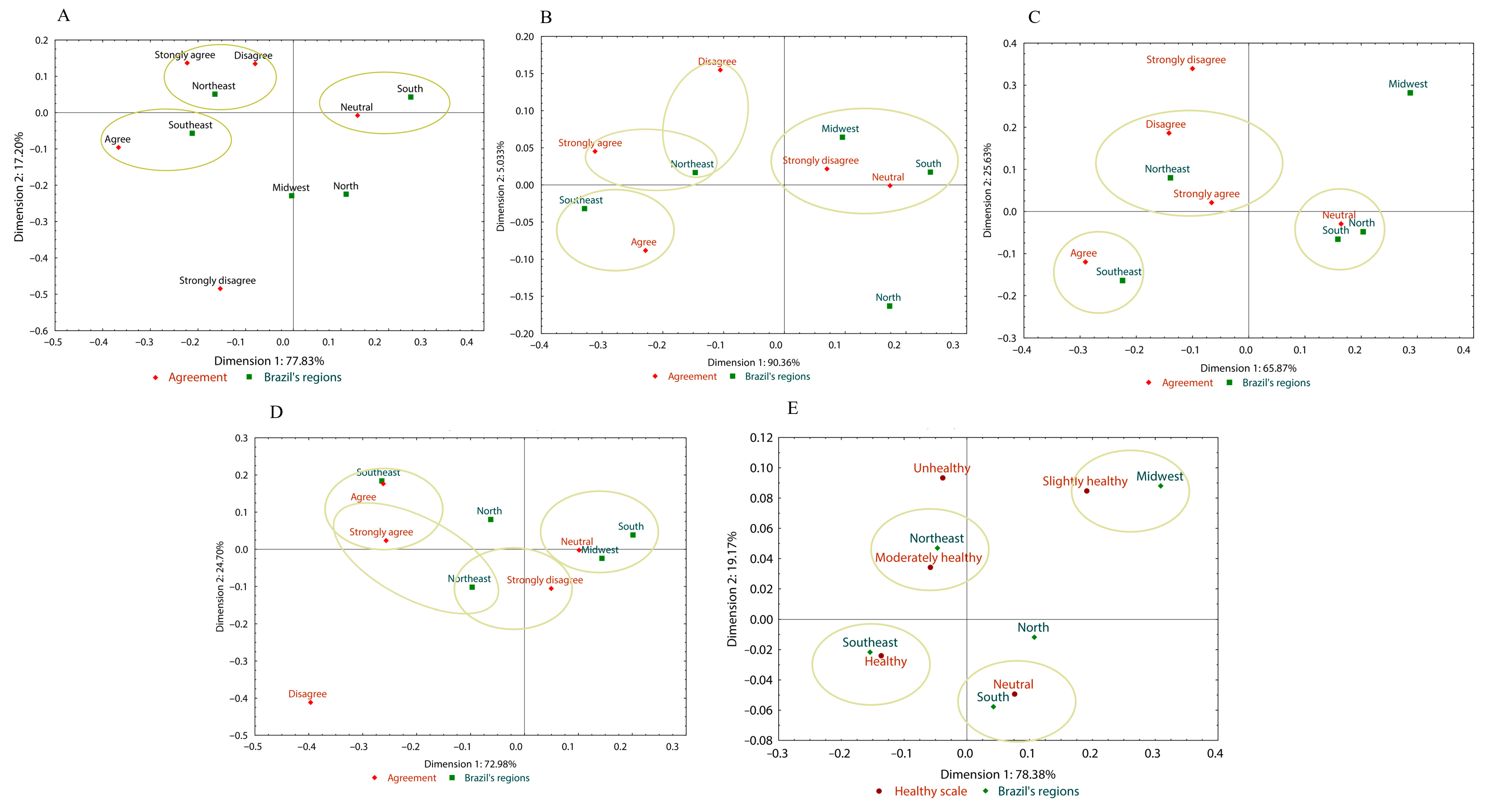

3.3. Perception of Hybrid Crude Palm Oil

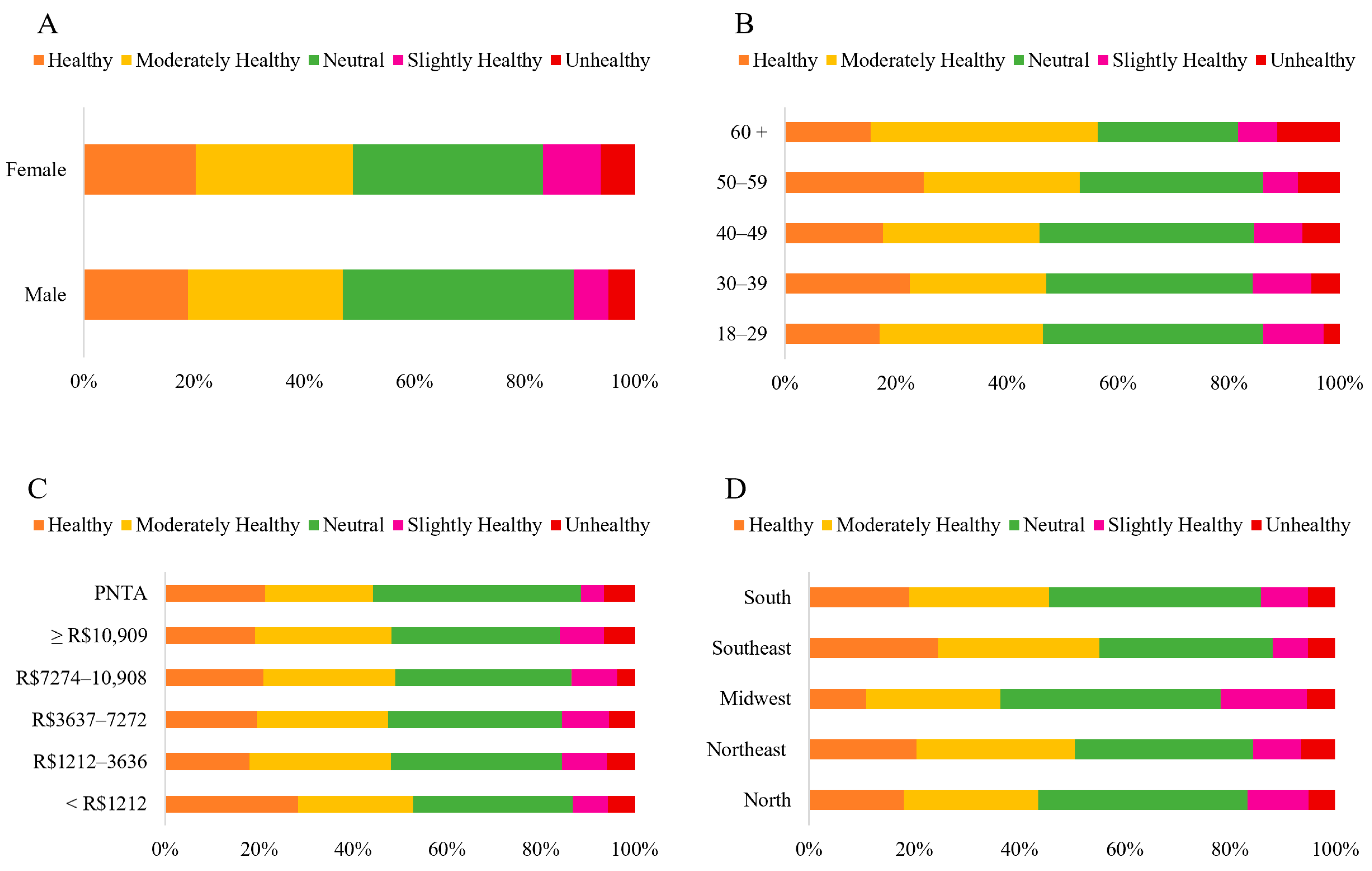

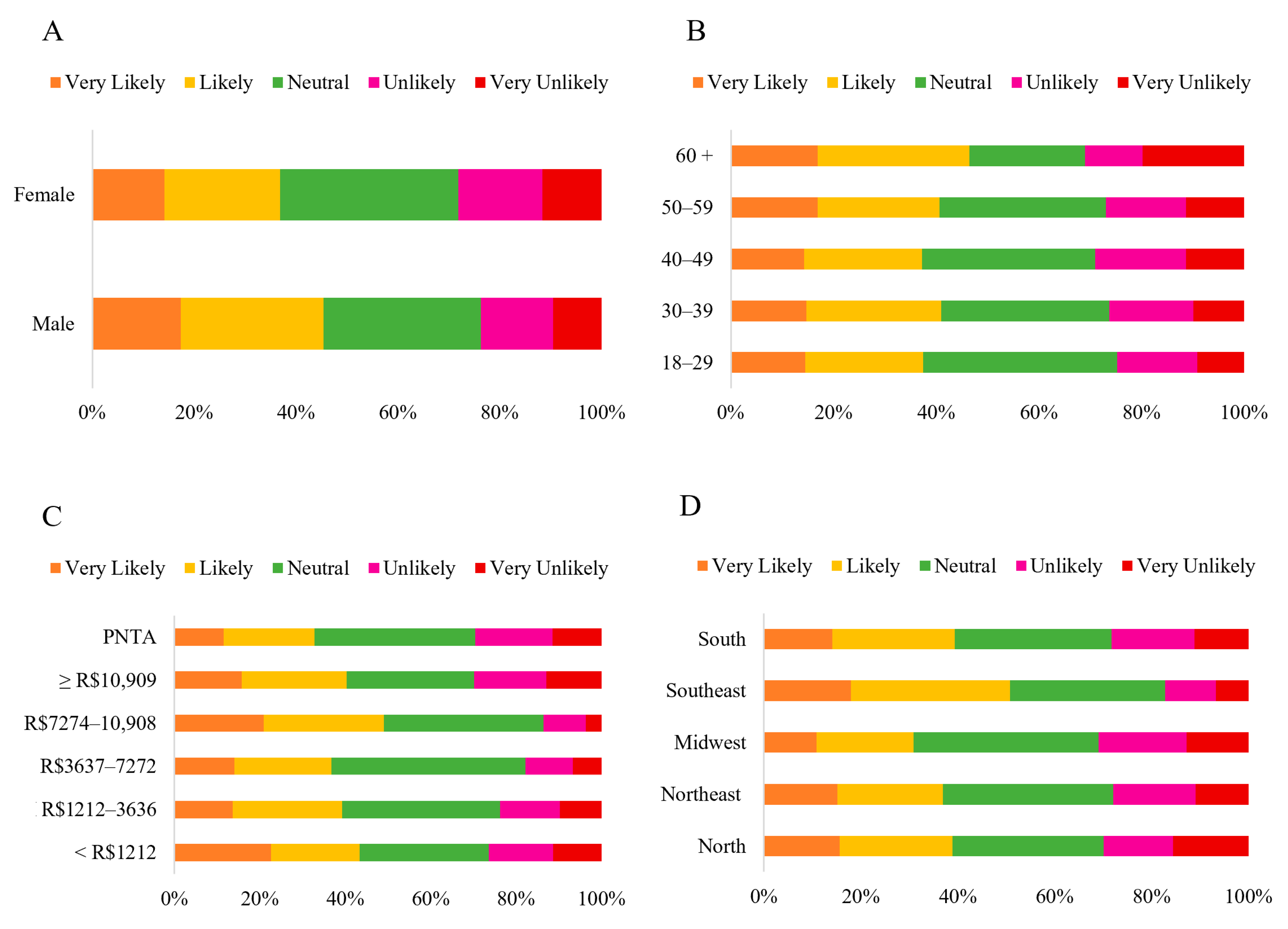

3.4. Purchase Potential of Products with Hybrid Crude Palm Oil

4. Discussion

4.1. Consumer Profile

4.2. Knowledge of Hybrid Crude Palm Oil

4.3. Perception of Hybrid Crude Palm Oil

4.4. Potential for Purchasing Products with Hybrid Crude Palm Oil

5. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

- Communication and Education: Awareness campaigns should be designed to clearly and technically elucidate the nutritional advantages of HCPO, notably its high oleic acid (ω-9) content and its rich composition of natural antioxidants (carotenoids, vitamin E), which confer significant antioxidant capacity and nutraceutical potential.

- Sustainable Production Expansion: Overcoming the current scale limitations is imperative. This requires incentives to expand hybrid cultivation in integrated agroforestry systems, which promote socio-biodiversity (e.g., consortia with cocoa) and ensure the environmental and economic sustainability of the chain.

- Research and Development: Continuous investment in R&D is crucial for advancing the characterization of oil, development of food products, and validation of its beneficial health effects through clinical studies, providing the necessary scientific foundation for its popularization. Equally important is the expansion of these investigations to other Latin American countries, considering aspects of knowledge, perception, and consumption potential, which may foster both population acceptance and the formulation of regional strategies in health, market development, and public policies.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- CODEX STAN 210—CXS 210-199; Codex Standard for Named Vegetable Oils. Codex Alimentarius: Rome, Italy, 2024.

- USDA. United States Department of Agriculture. Foreign Agricultural Service. Production, Supply, and Distribution Online. Oilseeds: World Markets and Trade. Office of Global Analysis. 2025. Available online: https://www.fas.usda.gov/data/search?reports%5B0%5D=report_commodities%3A26&reports%5B1%5D=report_type%3A10259 (accessed on 22 August 2025).

- USDA. United States Department of Agriculture. Foreign Agricultural Service. Production—Palm Oil. 2025. Available online: https://www.fas.usda.gov/data/production/commodity/4243000 (accessed on 22 August 2025).

- USDA. United States Department of Agriculture. Foreign Agricultural Service. Palm Oil Explorer: Palm Oil 2025 World Production. Available online: https://ipad.fas.usda.gov/cropexplorer/cropview/commodityView.aspx?cropid=4243000 (accessed on 22 August 2025).

- Ferreira, L. A Resistência do Dendê: Produção Vive Realidades Distintas no Brasil. Globo Rural. 2025. Available online: https://globorural.globo.com/agricultura/noticia/2025/02/a-resistencia-do-dende-producao-vive-realidades-distintas-no-brasil.ghtml (accessed on 22 August 2025).

- Almeida, D.T.; Viana, T.V.; Costa, M.M.; Silva, C.S.; Feitosa, S. Effects of different storage conditions on the oxidative stability of crude and refined palm oil, olein and stearin (Elaeis guineensis). Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 39, 211–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Cunha, R.N.V.; Lopes, R. BRS Manicoré: Híbrido interespecífico entre o caiaué e o dendezeiro africano recomendado para áreas de incidência de amarelecimento-fatal. Embrapa Agroind. Aliment. 2010, 85, 1517–3887. Available online: https://ainfo.cnptia.Embrapa.br/digital/bitstream/item/63813/1/ComTec-85-2010.pdf (accessed on 22 August 2024).

- Pinto, S.S.; Lopes, R.; da Cunha, R.N.V.; dos Santos Filho, L.P.; Moura, J.I.L. Produção e Composição de Cachos e Incidência do Anel Vermelho em Híbridos Interespecíficos de Caiaué com Dendezeiro no Sul da Bahia. Agrotrópica 2019, 31, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, H.M.; Daza, E.; Ayala-Díaz, I.; Ruiz-Romero, R. High-Oleic Palm Oil (HOPO) Production from Parthenocarpic fruits in oil palm interspecific hybrids using naphthalene acetic acid. Agronomy 2021, 11, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tupinambá, M.J. Com Menor Acidez, Novo Azeite de Dendê Agrega Valor à Culinária Baiana. Notícias. Unidade Embrapa Agroenergia. Embrapa Amazônia Ocidental. 2021. Available online: https://www.embrapa.br/agroenergia/busca-de-noticias/-/noticia/62661022/com-menor-acidez-novo-azeite-de-dende-agrega-valor-a-culinaria-baiana (accessed on 22 August 2025).

- Mozzon, M.; Foligni, R.; Tylewicz, U. Chemical Characteristics and Nutritional Properties of Hybrid Palm Oils; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.-Y.; Le, D.D.; Bae, C.-S.; Park, J.W.; Lee, M.; Cho, S.-S.; Park, D.-H. Oleic acid attenuates asthma pathogenesis via Th1/Th2 immune cell modulation, TLR3/4-NF-κB-related inflammation suppression, and intrinsic apoptotic pathway induction. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1429591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozzon, M.; Foligni, R.; Mannozzi, C. Current Knowledge on Interspecific Hybrid Palm Oils as Food and Food Ingredient. Foods 2020, 9, 631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, J.C.; Gómez, D.; Pacetti, D.; Núñez, O.; Gagliardi, R.; Frega, N.G.; Ojeda, M.; Loizzo, M.R.; Tundis, R.; Lucci, P. Effects of the Fruit Ripening Stage on Antioxidant Capacity, Total Phenolics, and Polyphenolic Composition of Crude Palm Oil from Interspecific Hybrid Elaeis oleifera × Elaeis guineensis. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2016, 64, 852–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojeda, M.; Borrero, M.; Sequeda-Castañeda, L.G.; Diez, O.; Castro, V.; García, Á.; Ruiz, A.J.; Pacetti, D.; Frega, N.; Gagliardi, R.; et al. Hybrid palm oil (Elaeis oleifera × Elaeis guineensis) supplementation improves plasma antioxidant capacity in humans. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 2016, 119, 1600070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucci, P.; Borrero, M.; Ruiz, A.J.; Pacetti, D.; Frega, N.G.; Díez, O.; Ojeda, M.; Gagliardi, R.; Parra, L.; Angel, M. Palm oil and cardiovascular disease: A randomized trial of the effects of hybrid palm oil supplementation on human plasma lipid patterns. Food Funct. 2016, 7, 347–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spreafico, F.; Sales, R.C.; Gil-Zamorano, J.; Medeiros, P.; Latasa, M.-J.; Lima, M.R.; De Souza, S.A.L.; Martin-Hernandez, R.; Gómez-Coronado, D.; Iglesias-Gutiérrez, E.; et al. Dietary supplementation with hybrid palm oil alters liver function in the common Marmoset. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 2765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sales, R.C.; Medeiros, P.; Spreafico, F.; De Velasco, P.C.; Gonçalves, F.K.A.; Martin-Hernandez, R.; Mantilla-Escalante, D.C.; Gil-Zamorano, J.; Peres, W.A.F.; Souza, S.A.L.; et al. Olive Oil, Palm Oil, and Hybrid Palm Oil Distinctly Modulate Liver Transcriptome and Induce NAFLD in Mice Fed a High-Fat Diet. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 20, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gesteiro, E.; Galera-Gordo, J.; González-Gross, M. Palm oil and cardiovascular health: Considerations to evaluate the literature critically. Nutr. Hosp. 2018, 35, 1229–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villamil, R.-A.; Romero, L.-N.; Ruiz, J.-P.; Patiño, D.-C.; Gutiérrez, L.-F.; Cortés, L.-Y. Efeitos do consumo diário de iogurtes funcionalizados com óleo de Sacha Inchi e óleo de palma híbrido interespecífico no perfil lipídico e na relação ApoB/ApoA1 de indivíduos adultos saudáveis. Foods 2024, 13, 3973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assunção, L.S.; Duarte, C.; Oliveira, C.; Danielski, R.; Kumari, S.; Nunes, I.L.; Shahidi, F. Nanoencapsulation of Hybrid Crude Palm Oil Unaué HIE OxG with Jackfruit By-Products as Encapsulants: A Study of Cellular Antioxidant Activity and Cytotoxicity in Caco-2 Cells. Food Chem. 2024, 448, 139009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, T.S.; de Castro Almeida, R.C.; Pegg, R.B.; Assuncao, L.S.; Passos, R.S.F.T.; Alves, A.S.B.; Ribeiro, C.D.F. Hybrid Crude Palm Oil Unaue HIE OxG Nanoencapsulated in Jackfruit Seed Flour: An Alternative for Beef Burger Preservation. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2025, 18, 5654–5671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homma, A.K.O. Histórico do desenvolvimento de híbridos interespecíficos entre caiaué e dendezeiro. Belém, PA. Embrapa Amaz. Ocident. 2016, 421, 36. Available online: https://www.infoteca.cnptia.embrapa.br/infoteca/bitstream/doc/1047110/1/TC1616DOC421AINFO.pdf (accessed on 22 August 2024).

- Barcelos, E.; Cunha, R.N.V.d.; Nouy, B.; Pacheco, A.R.; Silva, E.B. Recursos Genéticos de Caiaué. 2002. Available online: http://www.alice.cnptia.embrapa.br/alice/handle/doc/671607 (accessed on 22 August 2025).

- Bispo, A.M.; Alves, A.S.B.; da Silva, E.F.; Krumreich, F.D.; Nunes, I.L.; Ribeiro, C.D.F. Perception, Knowledge, and Consumption Potential of Crude and Refined Palm Oil in Brazilian Regions. Foods 2024, 13, 2923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, A.S.; Bell, A.; Adamson, A.; Moynihan, P. A questionnaire assessment of nutrition knowledge—Validity and reliability issues. Public Health Nutr. 2002, 5, 497–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machova, R.; Ambrus, R.; Zsigmond, T.; Bakó, F. The Impact of Green Marketing on Consumer Behavior in the Market of Palm Oil Products. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, D.T.; Nunes, I.L.; Conde, P.L.; Rosa, R.P.S.; Rogério, W.F.; Machado, E.R. A quality assessment of crude palm oil marketed in Bahia, Brazil. Grasas Aceites 2013, 64, 387–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBGE. Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística. Pesquisa Nacional por Amostra de Domicílios Contínua, 2º Trimestre. Estatísticas de Gênero—Indicadores Sociais das Mulheres no Brasil. Tabelas—Indicadores Sociais das Mulheres no Brasil—3ª Edição. Educação. Tabela 2.11—Nível de Instrução da População de 25 anos ou Mais, por Sexo, Segundo Grupos de Idade—Brasil—2022. Available online: https://www.ibge.gov.br/estatisticas/multidominio/genero/20163-estatisticas-de-genero-indicadores-sociais-das-mulheres-no-brasil.html (accessed on 22 August 2024).

- IFIC. International Food Information Council. Food& Health Survey. 2023. Available online: https://foodinsight.org/2023-foodhealth-survey/ (accessed on 22 August 2024).

- OECD/FAO. OECD-FAO Agricultural Outlook 2022–2031; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bittencourt, M. Agronegócio: Nova Variedade de Dendê Embrapa. 2021. Available online: https://economia.uol.com.br/reportagens-especiais/agronegocio-nova-variedade-de-dende-Embrapa/#cover (accessed on 9 January 2024).

- Correio. Novo dendê da Bahia: Conheça o Unaué, Azeite ‘Light’ Desenvolvido em Laboratório. 2021. Available online: https://www.correio24horas.com.br/bahia/novo-dende-da-bahia-conheca-o-unaue-azeite-light-desenvolvido-em-laboratorio-0821 (accessed on 9 January 2024).

- Antoniassi, R.; Machado, A.F.d.F.; Wilhelm, A.E.; Guedes, A.M.M.; Bizzo, H.R.; Oliveira, M.E.C.; Yokoyama, R.; Lopes, R. Óleo de palma de alto oleico produzido no brasil no ano de 2016. Embrapa Agroind. Aliment. 2018, 229, 1–6. Available online: https://ainfo.cnptia.Embrapa.br/digital/bitstream/item/193393/1/CT-229-oleo-palma-alto-oleico.pdf (accessed on 22 August 2024).

- USDA. Brazil Summary: Palm Oil. United States Department of Agriculture Foreign Agriculture Services (USDA, FAS). 2024. Available online: https://ipad.fas.usda.gov/cropexplorer/cropview/ChartSummary.aspx?cropid=4243000&year=2025&subrgnid=br_BRA000 (accessed on 7 January 2024).

- Watkins, C. An Afro-Brazilian Landscape: African Oil Palms and Socioecological Change in Bahia, Brazil. Ph.D. Thesis, Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, LA, USA, 2015. Available online: https://repository.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/1450 (accessed on 22 August 2024).

- Chew, C.L.; Ng, C.Y.; Hong, W.O.; Wu, T.Y.; Lee, Y.-Y.; Low, L.E.; Kong, P.S.; Chan, E.S. Improving sustainability of palm oil production by increasing oil extraction rate: A review. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2021, 14, 573–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabiul, M.K.; Promsivapallop, P.; Karim, R.A.; Islam, M.A.; Patwary, A.K. Fostering quality customer service during Covid-19: The role of managers’ oral language, employee work engagement, and employee resiliencece. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2022, 53, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponte, L.G.S.; Ribeiro, S.F.; Pereira, J.C.V.; Antunes, A.E.C.; Bezerra, R.M.N.; da Cunha, D.T. Consumer Perceptions of Functional Foods: A Scoping Review Focusing on Non-Processed Foods. Food Rev. Int. 2025, 41, 1738–1756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safraid, G.F.; Portes, C.Z.; Dantas, R.M.; Batista, Â.G. Perception of functional food consumption by adults: Is there any difference between generations? Braz. J. Food Technol. 2024, 27, e2023095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, A.S. O Azeite da Costa do Dendê: Um Produto do Território. Master’s Thesis, Programa de Pós-Graduação em Geografia, Universidade Federal da Bahia, Salvador, Brazil, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Castañeda, V. Bahia, a terra do dendê: Uma história transnacional e complexa do dendê. Afro-Ásia 2022, 66, 687–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanelli, R.M. Italian Consumers’ Perceptions and Understanding of the Concepts of Food Sustainability, Authenticity and Food Fraud/Risk. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguiar, L.K.; Martinez, D.C.; Caleman, S.M. Consumer awareness of palm oil as an ingredient in food and non-food products. J. Food Prod. 2018, 24, 297–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goes, S.B.; Santana, T.R.S.; Santos, C.B.; Silva, F.M. Análise Microbiológica Da Salada Vinagrete Utilizada Em Acarajés Comercializados Em Salvador/Ba. Rev. Ciência Cena 2022, 1, 9. Available online: https://estacio.periodicoscientificos.com.br/index.php/cienciaincenabahia/article/view/1261 (accessed on 22 August 2024).

- Amaral, D.A.; Gregório, E.L.; Silva, M.; Oliveira, J.H.M.; Bastos, B.F.M. Análise Microbiológica do Acarajé Comercializado na Feira de Arte e Artesanato de Belo Horizonte, MG. HU Rev. 2012, 38, 3–4. [Google Scholar]

- Sereno, H.R.; Cardoso, R.d.C.V.; Guimarães, A.G. O comércio e a segurança do acarajé e complementos: Um estudo com vendedores treinados em boas práticas. Rev. Inst. Adolfo Lutz 2011, 70, 354–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, R.C.L.; Vilas Boas, L.H.B.; Brito, M.J.B. Food safety, consumption behavior and personal values: An integrative review. Rev. Adm. UFSM 2024, 17, e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, L.A.; Greiner, R.; Alves, A.S.B.; Santos, S.R.C.; dos Santos, W.P.C.; Ribeiro, P.R.; Almeida, D.T. Content of minerals and antinutritional factors in moin-moin (steamed cowpea food). Afr. J. Food Sci. 2021, 15, 72–80. Available online: https://academicjournals.org/journal/AJFS/article-full-text/C85B61E66202 (accessed on 22 August 2024). [CrossRef]

- Da Motta Lody, R.G. Bahia Bem Temperada, 1st ed.; Editora Senac Sao Paulo: Sao Paulo, Brazil, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Tedner, S.G.; Asarnoj, A.; Thulin, H.; Westman, M.; Konradsen, J.R.; Nilsson, C. Food allergy and hypersensitivity reactions in children and adults—A review. J. Intern. Med. 2022, 291, 283–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asioli, D.; Aschemann-Witzel, J.; Caputo, V.; Vecchio, R.; Annunziata, A.; Næs, T.; Varela, P. Making sense of the “clean label” trends: A review of consumer food choice behavior and discussion of industry implications. Food Res. Int. 2017, 99, 58–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, P.; Teixeira, M.; Silva, S.C.E. Healthy eating as a trend: Consumers’ perceptions towards products with nutrition and health claims. Rev. Bras. Gest. Neg. 2021, 23, 405–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assunção, L.S.; Oliveira de Souza, C.; Shahidi, F.; Santos Oliveira, T.; Assis, D.D.J.; Pereira Santos, L.F.; Ferreira Ribeiro, C.D. Optimization and Characterization of Interspecific Hybrid Crude Palm Oil Unaué HIE OxG Nanoparticles with Vegetable By-Products as Encapsulants. Foods 2024, 13, 523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guadalupe, G.A.; Lerma-García, M.J.; Fuentes, A.; Barat, J.M.; Bas, M.d.C.; Fernández-Segovia, I. Presence of palm oil in foodstuffs: Consumers’ perception. Br. Food J. 2019, 121, 2148–2162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinkes, C.; Christoph-Schulz, I. Consumer Attitudes toward Palm Oil: Insights from Focus Group Discussions. J. Food Prod. Mark. 2019, 25, 875–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reardon, K.; Padfield, R.; Salim, H.K. “Consumers don’t see tigers dying in palm oil plantations”: A cross-cultural comparative study of UK, Malaysian and Singaporean consumer views of palm oil. Asian Geogr. 2019, 36, 117–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malani, P.; Kullgren, J.; Solway, E.; Wolfson, J.; Leung, C.; Singer, D.; Kirch, M. The Joy of Cooking and Its Benefits for Older Adults. University of Michigan National Poll on Healthy Aging. 2020. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/2027.42/155433 (accessed on 22 August 2024).

- Tani, Y.; Fujiwara, T.; Anzai, T.; Kondo, K. Cooking skills, living alone, and mortality: JAGES cohort study. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2023, 20, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolfson, J.A.; Martinez-Steele, E.; Tucker, A.C.; Leung, C.W. Greater frequency of cooking dinner at home and more time spent cooking are inversely associated with ultra-processed food consumption among US adults. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2024, 124, 1590–1605.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Area | Questions/Statements | Response Format | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Socioeconomic aspects |

| Multiple choice (Single answer) | [25] |

| Knowledge | [26] | ||

| What is meant by the term hybrid crude palm oil? | Multiple choice (Multiple answer) | ||

| Perception | [6,7,10,11,25,26] | ||

| The acidity of traditionally marketed crude palm oil is higher than that of hybrid crude palm oil. | Agree Partially agree Neither agree nor disagree Partially disagree Disagree | ||

| Hybrid crude palm oil has more nutrients than traditional crude palm oil. | |||

| The popularization and consumption of hybrid crude palm oil will not alter the authenticity of traditional Bahian dishes. | |||

| Hybrid crude palm oil does not cause gastrointestinal symptoms such as abdominal pain when consumed. | |||

| On a Likert scale of 1 to 5, how healthy do you consider hybrid crude palm oil? | Unhealthy Slightly unhealthy Neutral Moderately healthy Healthy | ||

| Potential Consumption | [27] | ||

| I am interested in trying hybrid crude palm oil. | Agree Partially agree Neither agree nor disagree Partially disagree Disagree | ||

| On a Likert scale of 1 to 5, how likely are you to purchase products with hybrid crude palm oil? | Very Likely Likely Neutral Unlikely Very Unlikely |

| Variable | N | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Region of residence | Northeast | 430 | 40.38 |

| South | 368 | 34.56 | |

| Southeast | 134 | 12.58 | |

| North | 78 | 7.32 | |

| Midwest | 55 | 5.16 | |

| Sex identification | Female | 743 | 69.77 |

| Male | 317 | 29.76 | |

| Prefer not to say | 3 | 0.28 | |

| Non-binary | 2 | 0.19 | |

| Age group | Between 18 and 29 years | 275 | 25.82 |

| Between 30 and 39 years | 293 | 27.51 | |

| Between 40 and 49 years | 266 | 24.98 | |

| Between 50 and 59 years | 160 | 15.02 | |

| 60 years or older | 71 | 6.67 | |

| Number of people living in the household | 1 | 135 | 12.68 |

| 2 | 336 | 31.55 | |

| 3 | 294 | 27.60 | |

| 4 | 212 | 19.91 | |

| 5 | 68 | 6.38 | |

| More than 5 | 20 | 1.88 | |

| Level of education | Postgraduate | 671 | 63 |

| Completed undergraduate degree | 146 | 13.71 | |

| Completed high school | 233 | 21.88 | |

| Completed elementary school | 8 | 0.75 | |

| Incomplete elementary school | 2 | 0.19 | |

| Prefer not to answer | 5 | 0.47 | |

| Occupation | Full-time/Part-time employment | 768 | 72.11 |

| Undergraduate/Graduate student | 244 | 22.91 | |

| Not working/Not studying | 38 | 3.57 | |

| Prefer not to answer | 15 | 1.41 | |

| Approximate household income | Less than 1 minimum wage | 53 | 4.98 |

| Between 1 and 3 minimum wages | 206 | 19.34 | |

| Between 3 and 6 minimum wages | 200 | 18.78 | |

| Between 6 and 9 minimum wages | 163 | 15.30 | |

| More than 9 minimum wages | 382 | 35.87 | |

| Prefer not to answer | 61 | 5.73 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alves, A.S.B.; Murowaniecki Otero, D.; Bispo, A.M.; de Jesus, F.d.E.S.; Silva, E.F.d.; Santos, L.d.M.; Nunes, I.L.; Cangussu, M.C.T.; Ribeiro, C.V.D.M.; Ferreira Ribeiro, C.D. Hybrid Crude Palm Oil in Brazilian Regions: Evaluation of Knowledge, Perceptions, and Consumption Potential. Foods 2025, 14, 3242. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14183242

Alves ASB, Murowaniecki Otero D, Bispo AM, de Jesus FdES, Silva EFd, Santos LdM, Nunes IL, Cangussu MCT, Ribeiro CVDM, Ferreira Ribeiro CD. Hybrid Crude Palm Oil in Brazilian Regions: Evaluation of Knowledge, Perceptions, and Consumption Potential. Foods. 2025; 14(18):3242. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14183242

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlves, Agnes Sophia Braga, Deborah Murowaniecki Otero, Alana Moreira Bispo, Fabiane do Espírito Santo de Jesus, Edilene Ferreira da Silva, Lívia de Matos Santos, Itaciara Larroza Nunes, Maria Cristina Teixeira Cangussu, Cláudio Vaz Di Mambro Ribeiro, and Camila Duarte Ferreira Ribeiro. 2025. "Hybrid Crude Palm Oil in Brazilian Regions: Evaluation of Knowledge, Perceptions, and Consumption Potential" Foods 14, no. 18: 3242. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14183242

APA StyleAlves, A. S. B., Murowaniecki Otero, D., Bispo, A. M., de Jesus, F. d. E. S., Silva, E. F. d., Santos, L. d. M., Nunes, I. L., Cangussu, M. C. T., Ribeiro, C. V. D. M., & Ferreira Ribeiro, C. D. (2025). Hybrid Crude Palm Oil in Brazilian Regions: Evaluation of Knowledge, Perceptions, and Consumption Potential. Foods, 14(18), 3242. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14183242