Occurrence of Aspergillus and Penicillium Species, Accumulation of Fungal Secondary Metabolites, and qPCR Detection of Potential Aflatoxigenic Aspergillus Species in Chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) Seeds from Different Farming Systems

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Marketed Chickpea Seed Samples

2.2. Isolation and Molecular Identification of the Fungal Microorganisms Belonging to the Aspergillus and Penicillium Genera Associated with the Marketed Chickpea Seed Samples

- For BenA: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 4 min, followed by 35 cycles of 94 °C for 1 min, 65 °C for 1 min and 72 °C for 1 min, with a final extension at 72 °C for 8 min;

- For CaM: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 4 min, followed by 35 cycles of 95 °C for 1 min, 55.5 °C for 1 min and 72 °C for 2 min, with a final extension at 72 °C for 8 min.

2.3. Analysis of Fungal Secondary Metabolites in the Marketed Chickpea Seed Samples and Determination of Secondary Metabolite Profile Produced In Vitro by Selected Fungal Isolates

2.4. DNA Quantification of Aflatoxigenic Aspergillus Species in Chickpea Seed Samples by qPCR

- For aflatoxigenic Aspergillus species, F-omt (5′-GGCCGCCGCTTTGATCTAGG-3′) and R-omt (5′-ACCACGACCGCCGCC-3′), designed on the omt-1 gene coding for the sterigamatocystin O-methyltransferase, a key enzyme in the aflatoxin biosynthetic pathway, which generates an amplicon of 123 bp and has previously been used for the detection of A. flavus and A. parasiticus [45,46];

- For chickpea DNA assay, Fw (5′-CCAAGGTCAAGATCGGAATCA-3′) and Rev (5′-CAAAGCCACTCTAGCAACCAAA-3′), designed on the internal control gene Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GADPH), generating an amplicon of 65 bp [47].

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

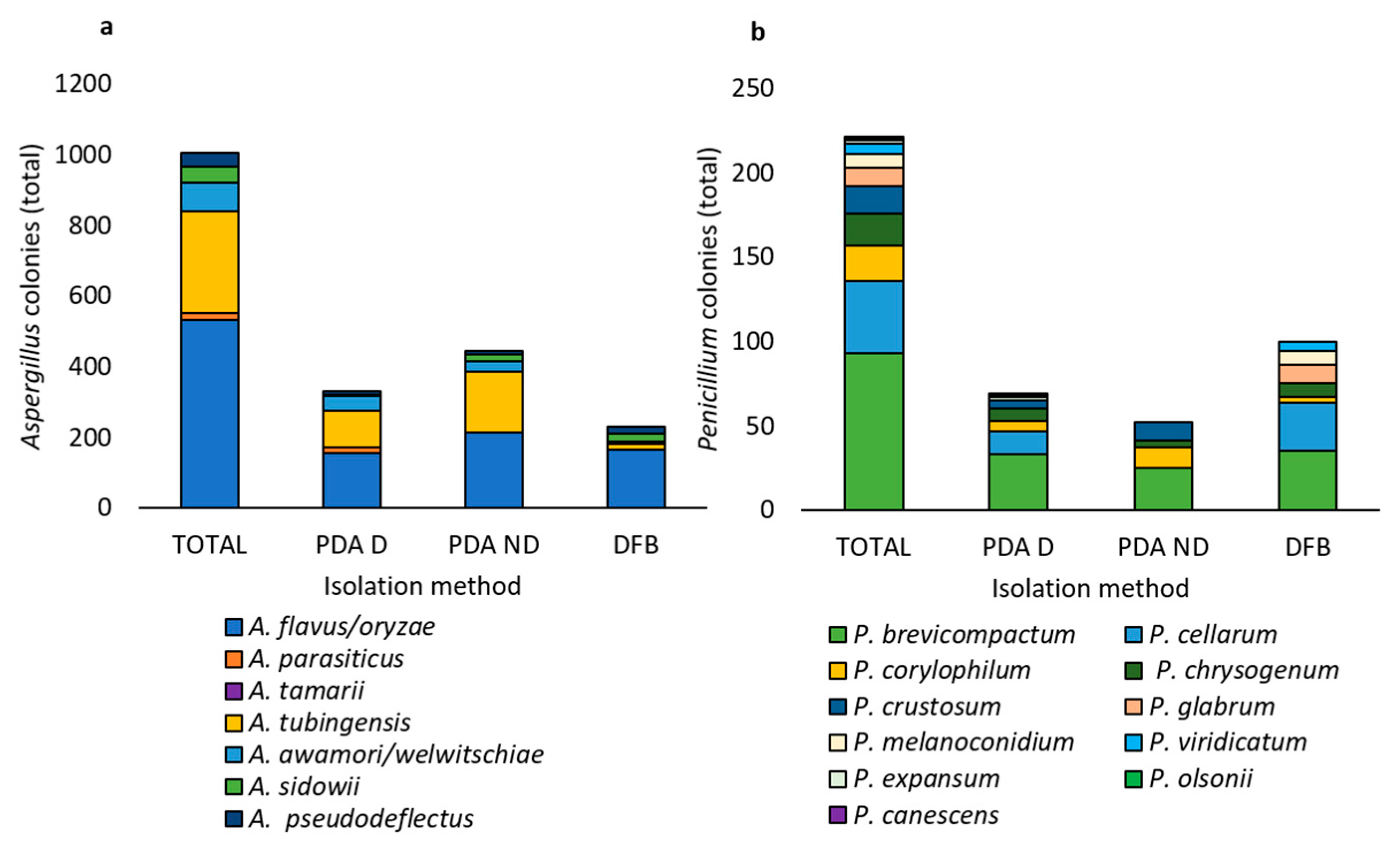

3.1. Fungal Microorganisms Associated with the Marketed Chickpea Seed Samples

3.2. Molecular Identification of the Fungal Isolates Belonging to the Aspergillus and Penicillium Genera Associated with the Marketed Chickpea Seed Samples

3.3. Fungal Secondary Metabolites in Marketed Chickpea Seed Samples and in In Vitro Cultures of Potentially Aflatoxigenic Aspergillus Isolates

3.4. Potentially Aflatoxigenic Aspergillus Species Quantified by qPCR in the Marketed Chickpea Seed Samples and Comparison of qPCR with Isolation Results

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- FAOSTAT. 2025. Available online: https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/QCL (accessed on 26 February 2025).

- Merga, B.; Haji, J. Economic importance of chickpea: Production, value, and world trade. Cogent. Food Agric. 2019, 5, 1615718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begum, N.; Khan, Q.U.; Liu, L.G.; Li, W.; Liu, D.; Haq, I.U. Nutritional composition, health benefits and bio-active compounds of chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.). Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1218468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cid-Gallegos, M.S.; Sánchez-Chino, X.M.; Álvarez-González, I.; Madrigal-Bujaidar, E.; Vásques-Garzón, V.R.; Baltiérrez-Hoyos, R.; Villa-Treviño, S.; Dávila-Ortíz, G.; Jiménez-Martinéz, C. Modification of in vitro and in vivo antioxidant activity by consumption of cooked chickpea in a colon cancer model. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahbub, R.; Francis, N.; Blanchard, C.; Santhakumar, A. The anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties of chickpea hull phenolic extracts. Food Biosci. 2021, 40, 100850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, M.; Cubero, J.I. Variation in Cicer arietinum L. Euphytica 1978, 27, 465–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyaya, H.D.; Dwivedi, S.L.; Baum, M.; Varshney, R.K.; Udupa, S.M.; Godwa, C.L.L.; Hoisington, D.; Singh, S. Genetic structure, diversity, and allelic richness in composite collection and reference set in chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.). BMC Plant Biol. 2008, 8, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y.; Thomas, M.; Bhardwaj, H.L. Chemical composition, functional properties and microstructural characteristics of three kabuli chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) as affected by different cooking methods. Food Sci. Technol. 2014, 49, 1215–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nene, Y.L.; Sheila, Y.K.; Sharma, S.B. A World List of Chickpea and Pigeon Pea Pathogens, 5th ed.; International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics: Andhra Pradesh, India, 1996; Volume 502, p. 324. [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez, M.L.; Candoya, E.; Nichea, M.J.; Zachetti, V.G.L.; Chulze, S. Impact of toxigenic fungi and mycotoxins in chickpea: A review. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2018, 23, 32–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamsi, S.; Khatun, A. Prevalence of fungi in different varieties of chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) seeds in storage. J. Bangladesh Acad. Sci. 2016, 40, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, T.; Malhotra, A.; Trivedi, P.C. Fungi associated with chickpea, lentil and blackgram seeds of Rajasthan. Int. J. Pharma Bio Sci. 2011, 2, 478–483. [Google Scholar]

- Alemayehu, S.; Abera, F.A.; Aymut, K.M.; Harvey, J.; Mahroof, R.; Subramanyam, B.; Ulmer, J. Fungal infection and mycotoxins contamination on farm-stored chickpea in major producing districts of Ethiopia. J. Biomed. Res. Environ. Sci. 2023, 4, 413–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero Donato, C.J.; Nichea, M.J.; Cendoya, E.; Zachetti, V.G.L.; Ramirez, M.L. Interacting abiotic factors affect growth and mycotoxin production profiles of Alternaria section Alternaria strains on chickpea-based media. Pathogens 2023, 12, 565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mushtaq, S.; Akram, A.; Hanif, N.Q.; Qureshi, R.; Akram, Z.; Akhund, S.; Nayyar, B.G. Natural incidence of aflatoxins, mycological profile and molecular characterization of aflatoxigenic strains in chickpea flour. Pak. J. Bot. 2015, 47, 1153–1160. [Google Scholar]

- Acuña-Gutiérrez, C.; Jiménez, V.M.; Müller, J. Occurrence of mycotoxins in pulses. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2022, 21, 4002–4017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pisuttu, C.; Risoli, S.; Moncini, L.; Nali, C.; Pellegrini, E.; Sarocco, S. Sustainable strategies to counteract mycotoxins contamination and cowpea weevil in chickpea seeds during post-harvest. Toxins 2023, 15, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Commission. Commission Regulation (EC) 2023/915 of 25 April 2023 on maximum levels for certain contaminants in food and repealing Regulation (EC) 1881/2006. Off. J. Eur. Un. 2023, L119, 103–157. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Commission Regulation (EC) 2024/1756 of 25 June 2024 amending and correcting Regulation (EU) 2023/915 on maximum levels for certain contaminants in food. Off. J. Eur. Un. 2024, L26.6, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Regulation (EU) 2018/848 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 30 May 2018 on organic production and labelling of organic products and repealing Council Regulation (EC) No 834/2007. Off. J. Eur. Un. 2018, L150, 1–92. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Directive 2009/128/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 21 October 2009 establishing a framework for Community action to achieve the sustainable use of pesticides. Off. J. Eur. Un. 2009, 309, 71–86. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Sufar, E.K.; Bernhoft, A.; Seal, C.; Rempelos, L.; Hasanaliyeva, G.; Zhao, B.; Iversen, P.O.; Baranski, M.; Volakakis, N.; et al. Mycotoxin contamination in organic and conventional cereal grain and products: A systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2024, 23, e13363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quaglia, M.; Beccari, G.; Vella, G.F.; Filippucci, R.; Buldini, D.; Onofri, A.; Sulyok, M.; Covarelli, L. Marketed quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa Willd.) seeds: A mycotoxin-free matrix contaminated by mycotoxigenic fungi. Pathogens 2023, 12, 418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Limonard, T. A modified blotter test for seed health. Neth. J. Plant Pathol. 1966, 72, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covarelli, L.; Beccari, G.; Prodi, A.; Generotti, S.; Etruschi, F.; Jaun, C.; Ferrer, E.; Manes, J. Fusarium species chemotype characterization and trichothecene contamination of durum and soft wheat in an area of central Italy. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2015, 95, 540–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quaglia, M.; Santinelli, M.; Sulyok, M.; Onofri, A.; Covarelli, L.; Beccari, G. Aspergillus, Penicillium and Cladosporium species associated with dried date fruits collected in the Perugia (Umbria, Central Italy) market. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2020, 322, 108585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castegnaro, M.; Wild, C.P. IARC activities in mycotoxins research. Nat. Toxins 1995, 3, 327–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perrone, G.; Mulè, G.; Susca, A.; Battilani, P.; Pietri, A.; Logrieco, A. Ochratoxin A production and amplified fragment length polymorphism analysis of Aspergillus carbonarius, Aspergillus tubingensis, and Aspergillus niger strains isolated from grapes in Italy. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2006, 72, 680–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frisvad, J.C.; Hubka, V.; Ezekiel, C.N.; Hong, S.-B.; Nováková, A.; Chen, A.J.; Larsen, T.O.; Sklenár, F.; Mahakarnchanakul, W.; Samson, R.A.; et al. Taxonomy of Aspergillus section Flavi and their production of aflatoxins, ochratoxins and other mycotoxins. Stud. Mycol. 2019, 93, 1–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varga, J.; Frisvad, J.C.; Kocsubé, S.; Brankovics, B.; Tóth, B.; Samson, R.A. New and revised species in Aspergillus section Nigri. Stud. Mycol. 2011, 69, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glass, N.L.; Donaldson, G.C. Development of primer sets designed for use with the PCR to amplify conserved genes from filamentous Ascomycetes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1995, 61, 1323–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, S.-B.; Cho, H.-S.; Shin, H.-D.; Frisvad, J.C.; Samson, R.A. Novel Neosartorya species isolated from soil in Korea. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2006, 2, 477–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varga, J.; Due, M.; Frisvad, J.C.; Samson, R.A. Taxonomic revision of Aspergillus section Clavati based on molecular, morphological and physiological data. Stud. Mycol. 2007, 59, 89–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Tamura, K. MEGA7: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis version 7.0 for bigger dataset. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2016, 33, 1870–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altschul, S.F.; Gish, W.; Miller, W.; Myers, E.W.; Lipman, D.J. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 1990, 3, 403–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samson, R.A.; Visagie, C.M.; Houbraken, J.; Hong, S.B.; Hubka, V.; Klaassen, C.H.V.; Perrone, G.; Seifert, K.A.; Susca, A.; Tanney, J.B.; et al. Phylogeny, identification and nomenclature of the genus Aspergillus. Stud. Mycol. 2014, 78, 141–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steenwyk, J.L.; Shen, X.-X.; Lind, A.L.; Goldman, G.H.; Rokas, A. A robust phylogenomic time tree for biotechnologically and medically important fungi in the genera Aspergillus and Penicillium. mBio 2019, 10, e00925-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Houbraken, J.; Kocsubé, S.; Visagie, C.M.; Yilmaz, N.; Wang, X.-C.; Meijer, M.; Kraak, B.; Hubka, V.; Bensch, K.; Samson, R.A.; et al. Classification of Aspergillus, Penicillium, Talaromyces and related genera (Eurotiales): An overview of families, genera, subgenera, sections, series and species. Stud. Mycol. 2020, 95, 5–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saitou, N.; Nei, M. The neighbor-joining method: A new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1987, 4, 406–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Felsenstein, J. Confidence limits on phylogenies: An approach using the bootstrap. Evolution 1985, 39, 783–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamura, K.; Nei, M.; Kumar, S. Prospects for inferring very large phylogenies by using the neighbor-joining method. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 11030–11035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sulyok, M.; Suman, M.; Krska, R. Quantification of 700 mycotoxins and other secondary metabolites of fungi and plants in grain products. NPJ Sci. Food 2024, 8, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Commission. Decision 2002/657/EC of 12 August 2002 implementing Council Directive 96/23/EC concerning the performance of analytical methods and the interpretation of results. Off. J. Eur. Un. 2002, 221, 8–36. [Google Scholar]

- Salfinger, Y.; Tortorello, M.L. Compendium of Methods for the Microbiological Examination of Foods, 5th ed.; American Public Health Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Shapira, R.; Paster, N.; Eyal, O.; Menasherov, M.; Mett, A.; Salomon, R. Detection of aflatoxigenic molds in grains by PCR. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1996, 62, 3270–3273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez, A.; Rodríguez, M.; Luque, M.I.; Martín, A.; Córdoba, J.J. Real-time PCR assay for detection and quantification of aflatoxin-producing molds in foods. Food Microbiol. 2012, 31, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rohini, G.; Sahoo, A.; Tyagi, A.K.; Jain, M. Validation of internal control genes for quantitative gene expression studies in chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.). Biochem. Biophys. Res. Comm. 2010, 396, 283–288. [Google Scholar]

- Onofri, A.; Pannacci, E. Spreadsheet tools for biometry classes in crop science programmes. Commun. Biometry Crop Sci. 2014, 9, 43–53. [Google Scholar]

- Houbraken, J.; Samson, R.A. Phylogeny of Penicillium and segregation of Trichocomaceae into three families. Stud. Mycol. 2011, 70, 1–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamasaki, T.; Sato, Y.; Hatsuda, Y. Structure of Sydowinin A, Sydowinin B, and Sydowinol, metabolites from Aspergillus sydowi. Agric. Bio. Chem. 1975, 39, 2341–2345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellis, D.; Fischer, H.P. Moniliformin and related cyclobutenediones. In Synthesis of Pesticides Chemical Structure and Biological Activity Natural Products with Biological Activity; Geissbühler, H., Ed.; Pergamon: Pergamon, Greece, 1979; pp. 373–381. [Google Scholar]

- Nihei, K.; Itoh, H.; Hashimoto, K.; Miyairi, K.; Okuno, T. Antifungal cyclodepsipeptides, W493 A and B, from Fusarium sp.: Isolation and structural determination. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 1998, 62, 858–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bräse, S.; Encinas, A.; Keck, J.; Nising, C.F. Chemistry and biology of mycotoxins and related fungal metabolites. Chem. Rev. 2009, 109, 3903–3990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; Qiang, S. Recent advances in tenuazonic acid as a potential herbicide. Pest. Bio. Phys. 2017, 143, 252–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ezekiel, C.N.; Oyedele, A.O.; Kraak, B.; Ayeni, K.I.; Sulyok, M.; Houbraken, J.; Krska, R. Fungal diversity and mycotoxins in low moisture content ready-to-eat foods in Nigeria. Front Microbiol. 2020, 11, 615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uka, V.; Cary, J.W.; Lebar, M.D.; Puel, O.; De Saeger, S.; Di Mavungu, J.D. Chemical repertoire and biosynthetic machinery of the Aspergillus flavus secondary metabolome: A review. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2020, 19, 2797–2842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, S.K.; Singh, P.L. Mycofloral changes and aflatoxin contamination in stored chickpea seeds. Food Add. Contam. 1991, 8, 723–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, I.; Iftikhar, S.; Bhutta, A.R. Seed Borne Microorganism In Pakistan; A checklist; Pakistan Agricultural Research Council: Islamabad, Pakistan, 1993; p. 32.

- Javaid, A.; Bajwa, R.; Javaid, A.; Anjum, T. Fungi associated with seeds of pulses collected from Lahore and their effect on seed germination. Mycopath 2005, 3, 13–16. [Google Scholar]

- Dawar, S.; Syed, F.; Ghaffar, A. Seed borne fungi associated with chickpea in Pakistan. Pak. J. Bot. 2007, 39, 637–643. [Google Scholar]

- Youssef, M.F.; El-Mahmoudy, E.M.; Abubakr, M.A.S. Mesophilic fungi and mycotoxins contamination of Libyan cultivated four Fabaceae seeds. Res. J. Microbiol. 2008, 3, 520–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, D.P.; Pawar, P.V.; Muley, S.M. Mycoflora associated with Pigeon pea and Chickpea. Int. Multidiscip. Res. J. 2012, 2, 10–12. [Google Scholar]

- Aguaysol, N.C.; Acosta, M.E.; González, V.; Fogliata, G.; De Lisi, V. Patógenos detectados en semillas de garbanzo (Cicer arietinum) en Tucumán y áreas de influencia. Av. Agroind. 2013, 34, 28–30. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, V.K. Detection of mycoflora associated with Cicer arietinum L. seeds by agar plate method with PDA. Weekly Sci. Res. J. 2014, 1, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Sontakke, N.R.; Hedawoo, G.B. Mycoflora associated with seeds of chickpea. Int. J. Life Sci. 2014, A2, 27–30. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, N. Food seed health of chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) at Panchgaon, Guargaon, India. Adv. Crop Sci. Technol. 2016, 4, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warunde, S.N.; Mane, S.S.; Giri, G.K. Detection of seedborne myco-flora associated with chickpea. Int. J. Pure App. Biosci. 2016, 4, 309–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menon, G. Mycoflora associated with farmer stored seeds of chickpea and pigeon pea collected from Satara. Asian J. Sci. Technol. 2017, 8, 6187–6191. [Google Scholar]

- Assunção, R.; Silva, M.J.; Alvito, P. Challenges in risk assessment of multiple mycotoxins in food. World Mycotoxin J. 2016, 9, 791–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.-B.; Lee, M.; Kim, D.-H.; Varga, J.; Frisvad, J.C.; Perrone, G.; Gomi, K.; Yamada, O.; Machida, M.; Houbraken, J.; et al. Aspergillus luchuensis, an industrially important black Aspergillus in East Asia. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e63769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bian, C.; Kusuya, Y.; Sklenář, F.; D’hooge, E.; Yaguchi, T.; Ban, S.; Visagie, C.M.; Houbraken, J.; Takahashi, H.; Hubka, V. Reducing the number of accepted species in Aspergillus series Nigri. Stud. Mycol. 2022, 102, 95–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, D.M.; Baek, J.H.; Choi, D.G.; Jeon, M.S.; Eyun, S.I.; Jeon, C.O. Comparative pangenome analysis of Aspergillus flavus and Aspergillus oryzae reveals their phylogenetic, genomic, and metabolic homogeneity. Food Microbiol. 2024, 119, 104435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dwivedi, S.N. Effect of fungal invasion on sugar of gram (Cicer arietinum L.) seed during storage. Indian J. Mycol. Plant Path. 1989, 19, 10–13. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, K.; Singh, A.K.; Singh, R.P. Detection of seed mycoflora of chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.). Ann. Pl. Protec. Sci. 2005, 13, 167–171. [Google Scholar]

- Amule, R.; Sinch, R.; Gupta, O.; Raipuriya, N.; Gupta, P.K. Study to detect seed borne mycoflora associated with chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) seeds. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. App. Sci. 2019, 8, 424–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tania, A.; Akram, A.; Hanif, N.Q.; Ajmal, M.; Seerat, W.; Nijabat, A.; Mahak, A. Proximate composition, fungal isolation and contamination of aflatoxin B1 in chickpea seeds from Punjab, Pakistan. Nat. Prod. Res. 2022, 37, 3314–3322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beccari, G.; Prodi, A.; Senatore, M.T.; Balmas, V.; Tini, F.; Onofri, A.; Pedini, L.; Sulyok, M.; Brocca, L.; Covarelli, L. Cultivation area affects the presence of fungal communities and secondary metabolites in Italian durum wheat grains. Toxins 2020, 12, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Senatore, M.T.; Prodi, A.; Tini, F.; Balmas, V.; Infantino, A.; Onofri, A.; Cappelletti, E.; Oufensou, S.; Sulyok, M.; Covarelli, L.; et al. Different diagnostic approaches for the characterization of the fungal community and Fusarium species complex composition of Italian durum wheat grain and correlation with secondary metabolite accumulation. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2023, 103, 4503–4521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomes, A.L.; Sousa, R.L.M.; das Neves, L.A.V.; da Gloria, E.M.; Burbarelli, M.F.C.; Seno, L.O.; Petrus, R.R.; Fernandes, A.M. Occurrence and co-exposure of aflatoxins and fumonisins in conventional and organic corn. Food Control. 2024, 165, 110628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacco, C.; Donato, R.; Zanella, B.; Pini, G.; Pettini, L.; Marino, M.F.; Rookmin, A.D.; Marvasi, M. Mycotoxins and flours: Effect of type crop, organic production, packaging type on the recovery of fungal genus and mycotoxins. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2020, 334, 108808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mascarello, G.; Pinto, A.; Parise, N.; Crovato, S.; Ravarotto, L. The perception of food quality. Profiling Italian consumers. Appetite 2015, 89, 175–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magkos, F.; Arvaniti, F.; Zampelas, A. Organic food: Buying more safety or just peace of mind? A critical review of the literature. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2006, 46, 23–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bennett, J.W.; Rubin, P.L.; Lee, L.S.; Chen, P.N. Influence of trace elements and nitrogen sources on versicolorin production by a mutant strain of Aspergillus parasiticus. Mycopathologia 1979, 69, 161–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakazato, M.; Morozumi, S.; Saito, K.; Fujinuma, K.; Nishima, T.; Kasai, N. Production of aflatoxins and aflatoxicols by Aspergillus flavus and Aspergillus parasiticus and metabolism of Aflatoxin B1 by aflatoxin-non-producing Aspergillus flavus. Eisei Kagaku 1991, 37, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gegan, R.M.; Chuturgoon, A.A.; Mulholland, D.A.; Dutton, M.F. Synthesis of sterigmatocystin derivatives and their biotransformation to aflatoxins by a blocked mutant of Aspergillus parasiticus. Mycopathologia 1999, 144, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahman, M.A.H.; Selamat, J.; Samsudin, N.I.P.; Shaari, K.; Mahror, N.; John, J.M. Antagonism of nonaflatoxigenic Aspergillus flavus isolated from peanuts against aflatoxigenic A. flavus growth and aflatoxin B1 production in vitro. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 10, 3993–4002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barros, G.; Chiotta, M.L.; Torres, A.; Chulze, S. Genetic diversity in Aspergillus parasiticus population from the peanut agroecosystem in Argentina. Appl. Microbiol. 2006, 6, 560–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ehrlich, K.C. Non-aflatoxigenic Aspergillus flavus to prevent aflatoxin contamination in crops: Advantages and limitations. Front. Microbiol. 2014, 10, 5–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, R.; Ghazali, F.M.; Mahyudin, N.A.; Samsudin, N.I.P. Biocontrol of aflatoxins using non-aflatoxigenic Aspergillus flavus: A literature review. J. Fungi. 2021, 7, 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, P.-K.; Ehrlich, K.C.; Hua, S.-S.T. Cladal relatedness among Aspergillus oryzae isolates and Aspergillus flavus S and L morphotype isolates. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2006, 108, 172–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toyotome, T.; Hamada, S.; Yamaguchi, S.; Takahashi, H.; Kondoh, D.; Takino, M.; Kanesaki, Y.; Kamei, K. Comparative genome analysis of Aspergillus flavus clinically isolated in Japan. DNA Res. 2019, 26, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Commission. Commission Regulation (EC) 1881/2006 of 19 December 2006 setting maximum levels for certain contaminants in foodstuffs. Off. J. Eur. Un. 2006, L364, 5–24. [Google Scholar]

- Gallo, P.; Imbimbo, S.; Alvino, S.; Castellano, V.; Arace, O.; Soprano, V.; Esposito, M.; Serpe, F.P.; Sansone, D. Contamination by aflatoxins B/G in food and commodities imported in Southern Italy from 2017 to 2020: A risk-based evaluation. Toxins 2021, 13, 368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agenzia Regionale per la Protezione Ambientale Piemonte. Il Rischio Micotossine in Piemonte. Available online: https://www.slideshare.net/slideshow/il-rischio-micotossine-in-piemonte/11157365#1 (accessed on 25 February 2025).

- Kronenberg, K. The safety and regulation of chickpeas, lentils, and field peas in farming and post-harvest operations. Food Prot. Trends 2022, 42, 22–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample | Farming System | Origin | Packaging |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Organic | EU (Umbria, Italy) | Sealed Plastic Bag |

| 2 | Organic | EU (Umbria, Italy) | Sealed Plastic Bag |

| 3 | Organic | EU (Umbria, Italy) | Sealed Plastic Bag |

| 4 | Organic | Extra-EU | Sealed Plastic Bag |

| 5 | Organic | EU (Umbria, Italy) | Unsealed Cardboard Box |

| 6 | Organic | EU (Umbria, Italy) | Sealed Plastic Bag |

| 7 | Organic | EU (Umbria, Italy) | Sealed Plastic Bag |

| 8 | Organic | EU (Umbria, Italy) | Sealed Plastic Bag |

| 9 | Organic | EU (unspecified) | Sealed Plastic Bag |

| 10 | Organic | EU (Umbria, Italy) | Sealed Plastic Bag |

| 11 | Non-Organic | EU (Umbria, Italy) | Sealed Plastic Bag |

| 12 | Non-Organic | EU (Puglia, Italy) | Sealed Plastic Bag |

| 13 | Non-Organic | EU (Italy) | Sealed Plastic Bag |

| 14 | Non-Organic | EU (Umbria, Italy) | Sealed Plastic Bag |

| 15 | Non-Organic | EU (Umbria, Italy) | Sealed Plastic Bag |

| 16 | Non-Organic | EU (Umbria, Italy) | Sealed Plastic Bag |

| 17 | Non-Organic | EU (Spain) | Sealed Plastic Bag |

| 18 | Non-Organic | Unspecified | Sealed Plastic Bag |

| 19 | Non-Organic | EU (The Marche, Italy) | Sealed Plastic Bag |

| 20 | Non-Organic | EU (Umbria, Italy) | Sealed Plastic Bag |

| Fungal Genera | Samples | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | |

| Aspergillus | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Penicillium | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||

| Cladosporium | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||||||

| Alternaria | X | X | X | |||||||||||||||||

| Rhizopus | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Other genera | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||

| Secondary Metabolites * | Samples from Organic Farming System | Samples from Integrated Farming System | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | |

| Cyclobutanediones | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Moniliformin Fus | 0.24 | 0.14 | 0.56 | 0.14 | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD |

| Cyclodepsipeptides | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Destruxin B Fus | 0.42 | <LOD | 0.30 | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | 0.01 | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | 0.03 | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD |

| Enniatin A Fus | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | 0.001 | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD |

| Enniatin A1 Fus | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.04 | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.01 | <LOD | <LOD | 0.01 | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD |

| Enniatin B Fus | 0.37 | 0.21 | 0.72 | 0.18 | 0.09 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.01 | <LOD | 0.14 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| Enniatin B1 Fus | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.21 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | <LOD | 0.01 | <LOD | 0.09 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | <LOD | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| W493 Fus | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | 0.29 | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | 0.11 | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD |

| Cyclopeptides | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Tentoxins Al | <LOD | <LOD | 0.30 | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD |

| Propionic acids | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 3-Nitropropionic acid As | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | 0.88 | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD |

| Sesquiterpenes | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Sporogen AO As | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | 0.19 | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD |

| Tetramic acids | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Tenuazonic acid Al | 6.35 | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | 6.50 | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD |

| Trichothecenes | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Deoxynivalenol Fus | 1.61 | N.D. | 2.67 | 0.59 | 0.46 | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD |

| Xanthone derivatives | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Sydowinin B As | 2.06 | 1.54 | 3.54 | 1.93 | 1.62 | 1.04 | 3.94 | 0.76 | 1.15 | 0.97 | 1.32 | 1.63 | 2.14 | 1.47 | 1.90 | 1.51 | 3.44 | 2.37 | 1.18 | 1.32 |

| Secondary Metabolites * | Aspergillus flavus/oryzae | Aspergillus parasiticus | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 43 | 62 | 71 | 89 | 148 | |

| Aflatoxins | ||||||

| Aflatoxicol | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | 33.9 |

| Aflatoxin B1 | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | 18,100 |

| Aflatoxin B2 | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | 6640 |

| Aflatoxin G1 | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | 30,800 |

| Aflatoxin G2 | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | 6050 |

| Aflatoxin M1 | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | 752 |

| O-Methylsterigmatocystin | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | 214 |

| Sterigmatocystin | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | 72.5 |

| Anthraquinoids | ||||||

| Averufin | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | 962 |

| Norsolorinic acid | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | 210 |

| Depsipeptides | ||||||

| Aspergillicin derivatives | 441 | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | 3730 |

| Dihydrobenzofuran derivatives | ||||||

| Asperfuran | 159 | 215 | 47.4 | 65.1 | 58 | <LOD |

| Isocumarins | ||||||

| Dichlordiaportin | 3.72 | <LOD | <LOD | 0.94 | 0.59 | 187 |

| O-Methyldichlordiaportin | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | 43.7 |

| Koningic acids | ||||||

| Heptelidic acid | <LOD | 683 | 1220 | 673 | 521 | <LOD |

| Monoterpenoids | ||||||

| Gliocladic acid | <LOD | 4440 | 2750 | 3990 | 4190 | <LOD |

| Penicillins | ||||||

| Penicillin G | 123,000 | 1,390,000 | 1,850,000 | 961,000 | 373,000 | <LOD |

| Propionic acids | ||||||

| 3-Nitropropionic acid | 2570 | 4960 | 26,200 | 10,100 | 12,200 | 463,000 |

| Pyrones | ||||||

| Kojic acid | 33.5 | 676 | 1010 | 687 | 77.5 | 401,000 |

| Sesquiterpenes | ||||||

| Sporogea AO | 152.5 | 67 | 55.4 | 19.9 | <LOD | |

| Steroids | ||||||

| Helvolic acid | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | 169 |

| Terpenes | ||||||

| Cyclopiazonic acid | <LOD | 62,600 | <LOD | 47,200 | 38,500 | <LOD |

| Versicolorins | ||||||

| Versiconal acetate | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | 34.8 |

| Versicolorin C | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | 1060 |

| Others | ||||||

| NP 1243 | 2.72 | 1.73 | <LOD | 1.39 | 1.37 | <LOD |

| Samples | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | |

| Potentially aflatoxigenic Aspergillus species detected by isolation methods (number of colonies) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| A. flavus/oryzae | 49 | 61 | 86 | 39 | 71 | 1 | 69 | - | - | - | 10 | 6 | 12 | - | 39 | 42 | - | 27 | - | 10 |

| A. parasiticus | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 17 | - |

| TOTAL | 49 | 61 | 86 | 39 | 71 | 1 | 69 | - | - | - | 10 | 6 | 12 | - | 39 | 42 | - | 27 | 17 | 10 |

| Potentially aflatoxigenic Aspergillus species detected by qPCR (pg Aspergillus DNA/ng chickpea seeds DNA) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| TOTAL | 0.031 | 0.015 | 0.012 | 0.008 | 0.009 | <LOD | 0.013 | 0.006 | 0.011 | 0.008 | 0.016 | <LOD | 0.013 | <LOD | 0.011 | 0.018 | <LOD | 0.006 | 0.014 | <LOD |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Quaglia, M.; Tini, F.; Bajrami, E.; Quadrini, E.; Fedeli, M.; Sulyok, M.; Beccari, G.; Covarelli, L. Occurrence of Aspergillus and Penicillium Species, Accumulation of Fungal Secondary Metabolites, and qPCR Detection of Potential Aflatoxigenic Aspergillus Species in Chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) Seeds from Different Farming Systems. Foods 2025, 14, 2610. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14152610

Quaglia M, Tini F, Bajrami E, Quadrini E, Fedeli M, Sulyok M, Beccari G, Covarelli L. Occurrence of Aspergillus and Penicillium Species, Accumulation of Fungal Secondary Metabolites, and qPCR Detection of Potential Aflatoxigenic Aspergillus Species in Chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) Seeds from Different Farming Systems. Foods. 2025; 14(15):2610. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14152610

Chicago/Turabian StyleQuaglia, Mara, Francesco Tini, Emina Bajrami, Erica Quadrini, Mariateresa Fedeli, Michael Sulyok, Giovanni Beccari, and Lorenzo Covarelli. 2025. "Occurrence of Aspergillus and Penicillium Species, Accumulation of Fungal Secondary Metabolites, and qPCR Detection of Potential Aflatoxigenic Aspergillus Species in Chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) Seeds from Different Farming Systems" Foods 14, no. 15: 2610. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14152610

APA StyleQuaglia, M., Tini, F., Bajrami, E., Quadrini, E., Fedeli, M., Sulyok, M., Beccari, G., & Covarelli, L. (2025). Occurrence of Aspergillus and Penicillium Species, Accumulation of Fungal Secondary Metabolites, and qPCR Detection of Potential Aflatoxigenic Aspergillus Species in Chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) Seeds from Different Farming Systems. Foods, 14(15), 2610. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14152610