Factors Influencing Consumer Behavior and Purchasing Decisions Regarding Mud Crabs (Scylla paramamosain) in the Major Cities of Vietnam

Abstract

1. Introduction

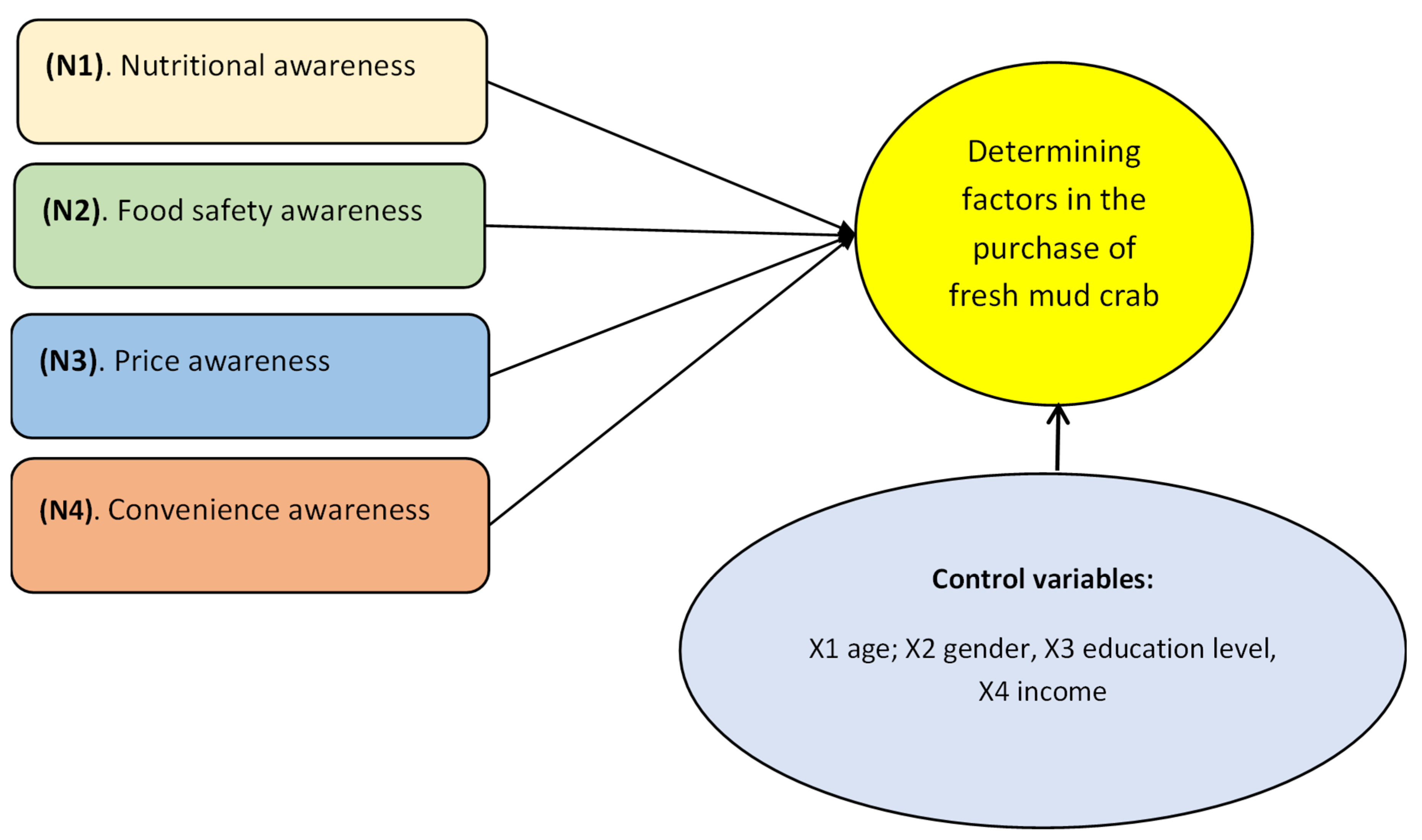

2. Theoretical Approach and Perspective Review

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Area

3.2. Data Collection and Development of Research Scales

3.2.1. Data Collection

3.2.2. Research Scale Development

3.3. Data Analysis

3.3.1. Verifying the Reliability Coefficient

- K is the number of variables (items)—usually the number of questions.

- Sigma squared is the variance. You can find the statistical terms and formulas using Google, or you may already have a basic understanding of these.

- Y is the component variable.

- X is the total variable.

3.3.2. Exploratory Factor Analysis

- Eigenvalues (representing the variance explained by each factor) must be greater than 1, with a cumulative variance exceeding 50%.

- The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) test coefficient assesses the suitability of factor analysis. The KMO value should range between 0.5 and 1; a value below 0.5 indicates that factor analysis may not be appropriate for the data.

- Factor loading coefficients, which measure the correlation between variables and factors, should be greater than 0.3 to be considered acceptable.

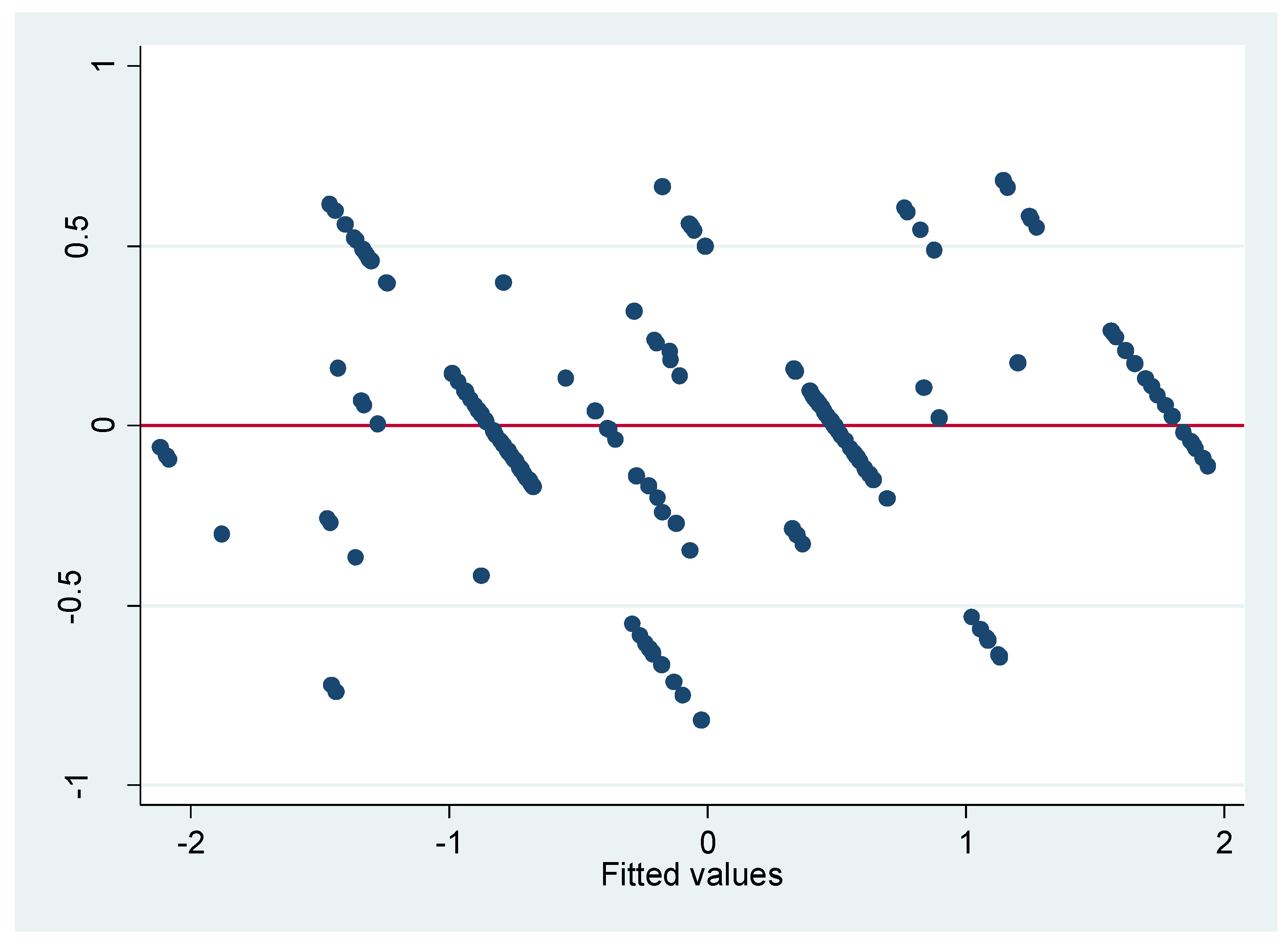

3.3.3. Multiple Regression Analysis

- Xpi denotes the value of the pi independent variable at the ith observation.

- Bp is the partial regression coefficient.

- ei is a stochastic independent variable characterized by a normal distribution, with a mean of 0 and constant variance.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Attributes of Mud Crab Consumers in Vietnam

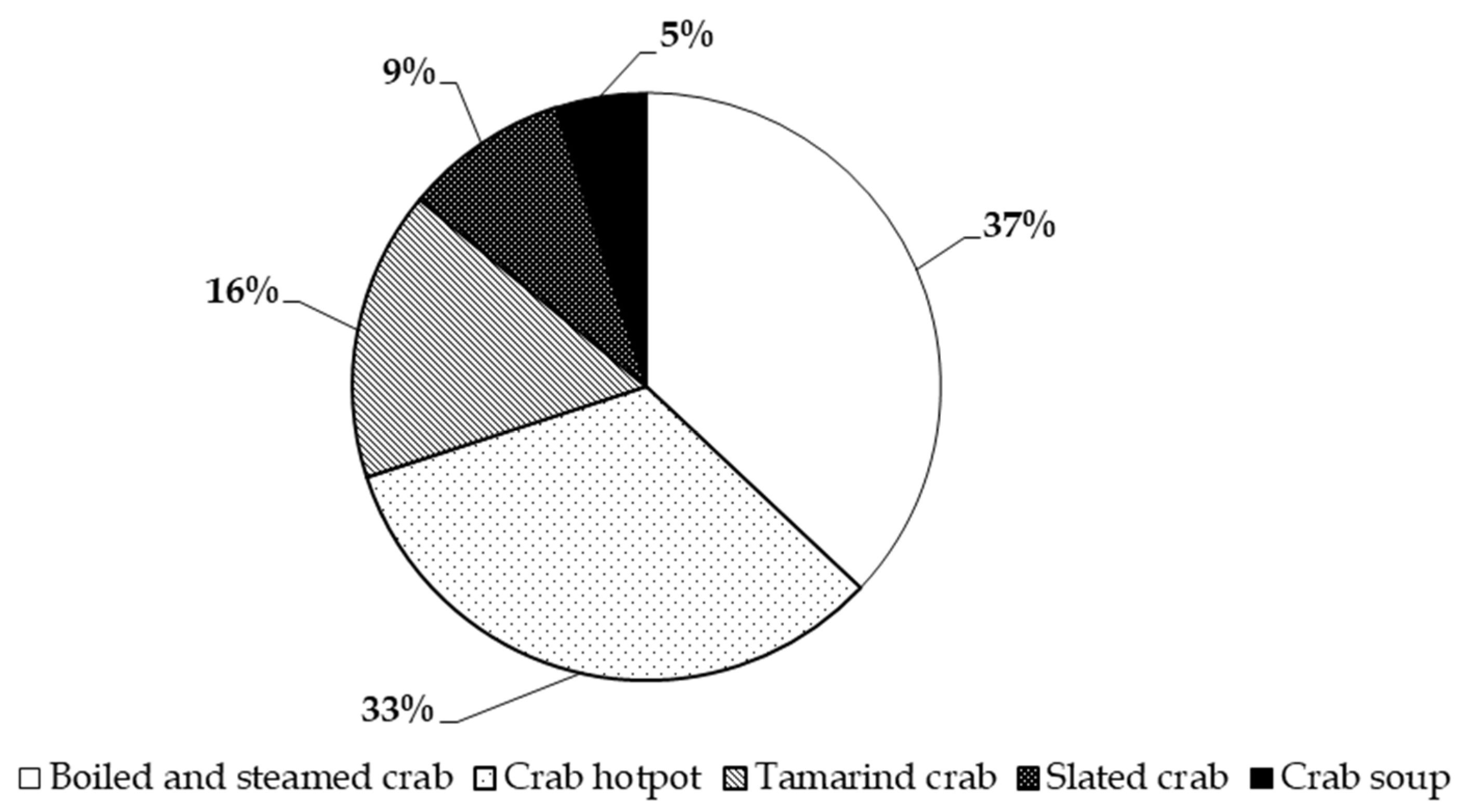

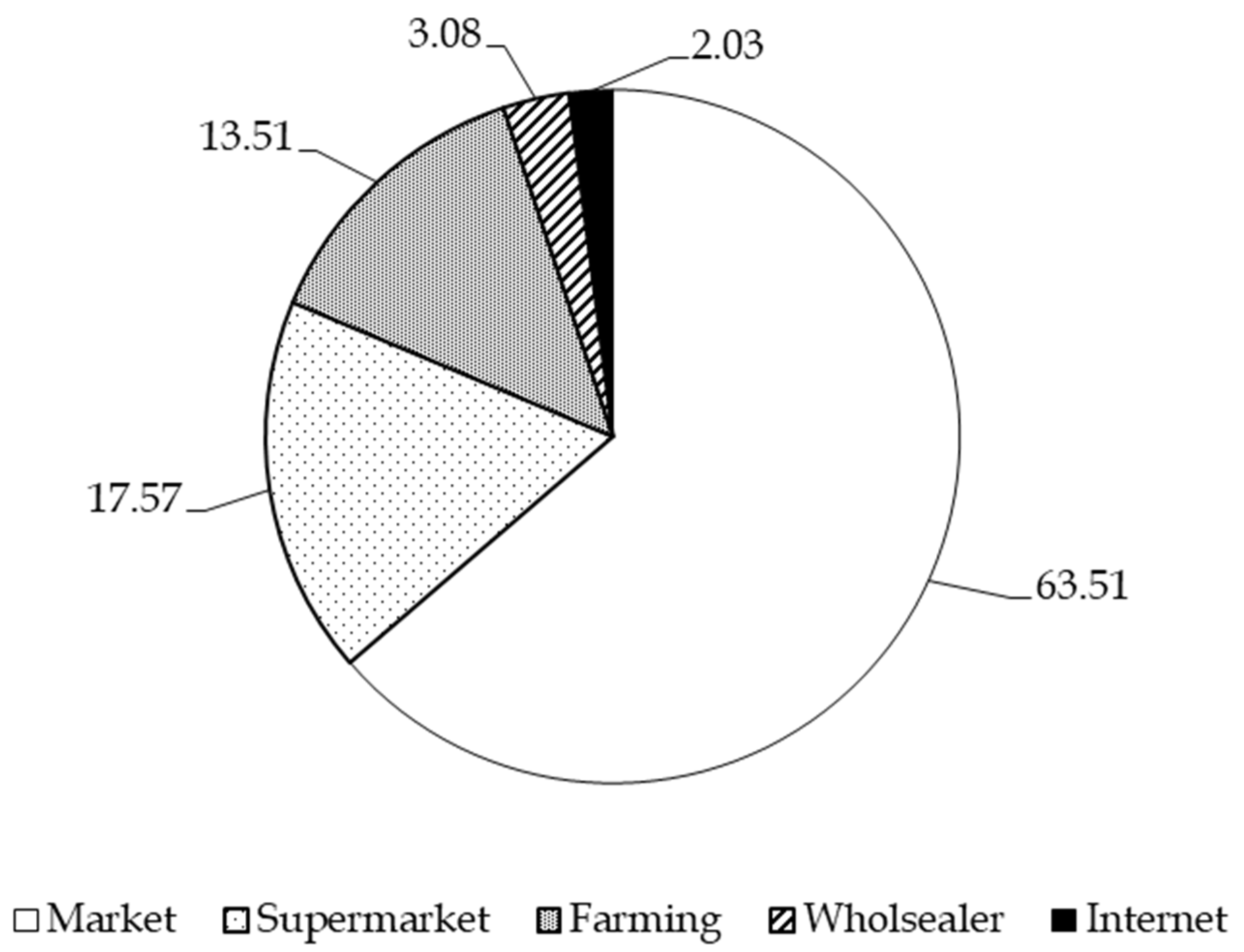

4.2. Domestic Consumer Demand for Fresh Mud Crab in Vietnam

4.3. Factors Affecting the Decision to Buy Fresh Mud Crab in Vietnam

4.3.1. Testing the Reliability of Observed Variables

4.3.2. Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA)—Independent Variable

5. Solutions and Recommendations

5.1. Basis for Proposing Solutions

5.2. Solutions and Recommendations to Enhance the Value of Vietnam’s Mud Crabs

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Salladarré, F.; Guillotreau, P.; Perradeau, Y.; Monfort, M.-C. The demand for seafood eco-labels in France. J. Agric. Food Ind. Organ. 2011, 8, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchirico, J.N.; Bush, S.R.; Sanchirico, J.N.; Uchida, H. Evolution and future of the sustainable seafood market. Nat. Sustain. 2018, 1, 392–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. The state of world fisheries and aquaculture 2020. In Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations 4; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2020; p. 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naylor, R.L.; Goldburg, R.J.; Primavera, J.H.; Kautsky, N.; Beveridge, M.C.M.; Clay, J.; Folke, C.; Lubchenco, J.; Moonet, H.; Troell, M. Effect of aquaculture on world fish supplies. Nature 2000, 405, 1017–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delgado, C.L.; Wada, N.; Rosegrant, M.W.; Meijer, S.; Ahmed, M. Outlook for Fish to 2020: Meeting Global Demand; The International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI): Washington, DC, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Tacon, A.G.J.; Metian, M. Fish matters: Importance of aquatic foods in human nutrition and global food supply. Rev. Fish. Sci. 2013, 21, 22–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, R.A.; Green, B.S.; Tracey, S.R.; Pitcher, T.J. Provenance of global seafood. Fish Fish. 2016, 17, 585–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- General Statistics Office. Socio-Economic Situation; General Statistics Office: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Zweig, R.D.; Saugmann, O.; Ich, C. Vietnam: Research on the Seafood Industry; Japan and World Bank Group Trust Funds Program Report (Vietnamese); Rural Development and Natural Resources East Asia & Pacific Regional (EASRD): Bangkok, Thailand, 2005; p. 49. [Google Scholar]

- Viet, T.V. The role and potential of the seafood industry in the economic development of the Mekong Delta, Vietnam. Can Tho Univ. J. Sci. 2013, 27, 136–144. [Google Scholar]

- Duy, D.T.; Nga, N.H.; Berg, H.; Da, C.T. Assessment of technical, economic, and allocative efficiencies of shrimp farming in the Mekong Delta, Vietnam. J. World Aquac. Soc. 2023, 54, 915–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.R.; Essu, E.J.; Islam, A.; Islam, H.; Ali, K.; Mathin, T.T.; Jany, R. Exploring the effect of climate transformation on biodiversity in coastal ecosystems. Glob. J. Eng. Technol. Adv. 2024, 21, 168–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da, C.T.; Thai, L.; Labor, F.; Long, T. Farmers’ perceived impact of high-dikes on rice and wild fish yields, water quality, and use of fertilizers in the Mekong Delta, Vietnam. ACS EST Water 2024, 4, 3235–3243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingrid, K. Aquaculture Farmer’s Needs in Mekong River Delta, Viet Nam; Agricultural Department, Netherlands Embassy in Hanoi and the Netherlands Enterprise Agency: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2024; pp. 1–62. Available online: https://www.agroberichtenbuitenland.nl/documenten/rapporten/2024/01/22/report-aquaculture-farmers-needs-in-mekong-delta-vietnam (accessed on 12 August 2024).

- Sayeed, Z.; Sugino, H.; Sakai, Y.; Yagi, N. Consumer preferences and willingness to pay for mud crabs in Southeast Asian countries: A discrete choice experiment. Foods 2021, 10, 2873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, D.; Keenan, C.P. Mud crab culture in the Minh Hai province, South Vietnam. In Mud Crab Aquaculture and Biology, Proceedings of the An International Forum, Darwin, Australia, 21–24 April 1997; Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research: Canberra, Australia, 1999; pp. 95–98. [Google Scholar]

- Nghi, N.Q.; Can, T.T.D.; Huy, P. Analysis of economic efficiency of prawn-mud crab farming model in Minh Hoa Commune, Chau Thanh District, Tra Vinh Province (Vietnamese). J. Vietnam. Argicultural Sci. Technol. 2015, 3, 15–22. [Google Scholar]

- Long, N.T. Analysis of finance and technique aspects of mud crab farming in Bac Lieu Province (Vietnamese). Can Tho Univ. J. Sci. 2019, 55, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangubhai, S.; Fox, M.; Nand, Y.; Mason, N. Value chain analysis of a women-dominated wild-caught mud crab fishery. Fish Fish. 2024, 25, 781–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hien, H.V.; Đuc, P.M.; Thao, Đ.N. An analysis of mub crab (Scylla paramamosain) distribution channels in Nam Can, Ca Mau province. In Internaltional Sympopsium Aquatic Products Processing Cleaner Production Chain for Healthier Food; Cantho University: Can Tho, Vietnam, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Pho, T.H. Farming of Mud Crab (Scylla spp.) in Ca Mau: Current Status of Technique, Social Economy and Solutions of Sustainable Development. Master’s Thesis, Nha Trang University, Hanoi, Vietnam, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Directorate of Fisheries. Summary Report of the Year 2022; Directorate of Fisheries: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Danh, L.N.; Doan, N.; Van Nguyen, T.; Thi Bich, H.N. An empirical study of financial efficiency and stability of crab–shrimp farming model n Mekong Delta, Vietnam. Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2024, 25, 754–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danh, L.N.; Truc, N.T.T. Supply chain management for the mud crab industry in the Mekong Delta. J. Commer. Sci. 2022, 116, 11–22. [Google Scholar]

- Nhung, T.N. Analysis of Factors Affecting the Production Efficiency of Crab Farming Models in the Mekong Delta; Can Tho University: Can Tho, Vietnam, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Naylor, R.; Fang, S.; Fanzo, J. A global view of aquaculture policy. Food Policy 2023, 116, 102422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eftimov, T.; Popovski, G.; Petkovic, M.; korousic Seljak, B.; Kocev, D. COVID-19 pandemic changes the food consumption patterns. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 104, 268–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheth, J. Impact of COVID-19 on consumer behavior: Will the old habits return or die? J. Bus. Res. 2020, 117, 280–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwanka, R.J.; Buff, C. COVID-19 generation: A conceptual framework of the consumer behavioral shifts to be caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Int. Consum. Mark. 2021, 33, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, A. Quality Control and Reliability; Thomas Nelson and Sons: London, UK, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Malcorps, W.; Newton, R.; Maiolo, S.; Elthoth, M.; Zhu, C.; Zhang, W.; Li, S.; Tlusty, M.; Little, D.C. Global seafood trade: Insights in sustainability messaging and claims of the major producing and consuming regions. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Ang, S.Y.; Hunter, A.M.; Erdem, S.; Bostock, J.; Da, C.T.; Nguyen, N.T.; Moss, A.; Hope, W.; Howie, C.; et al. Building towards one health: A transdisciplinary autoethnographic approach to understanding perceptions of sustainable aquatic foods in Vietnam. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuu, H.H.; Olsen, S.O.; Thao, D.T.; Nguyen, T.K.A. The role of norms in explaining attitudes, intention and consumption of a common food (fish) in Vietnam. Appetite 2008, 51, 546–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ngoc, C.N.M.; Nhat, P.T. Analysis of factors affecting choice decision of supermarket channels when buying fresh foods of consumers in Ho Chi Minh City. J. Dev. Integr. 2013, 10, 47–51. [Google Scholar]

- Duy, D.T.; Berg, H.; Dao, T.T.K.; Da, C.T. Assessing the effects of social capital on trade credit in shrimp farming in the Mekong Delta, Vietnam. Aquac. Econ. Manag. 2025, 29, 63–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McManus, A.; Hunt, W.; Storey, J.; McManus, J.; Hilhorst, S. Perceptions and preference for fresh seafood in an Australian context. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2014, 38, 146–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaeema, A.; Hassan, Z. Factors affecting purchase decision of canned tuna brands in Maldives. Int. J. Account. Bus. 2016, 4, 124–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riniwati, H.; Harahab, N.; Carla, T.Y. Analysis of Indonesian crab export competitiveness in international market. Int. Rev. Manag. Mark. 2017, 7, 23–27. Available online: https://econjournals.com/index.php/irmm/article/view/5576 (accessed on 19 September 2024).

- Lorenzo, R.A.; Tomac, A.; Tapella, F.; Yeannes, M.I.; Romero, M.C. Biochemical and quality parameters of southern king crab meat after transport simulation and re-immersion. Food Control. 2021, 119, 107480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khasanah, U.; Huang, W.-C.; Asmara, R. Indonesian frozen and processed crab export performance and competitiveness analysis. Agric. Soc. Econ. J. 2019, 19, 165–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Yan, B.; Chen, X.; Cai, C.; Guan, S. Supply chain coordination of fresh agricultural products based on consumer behavior. Comput. Oper. Res. 2020, 123, 105038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlucci, D.; Nocella, G.; De Devitiis, B.; Viscecchia, R.; Bimbo, F.; Nardone, G. Consumer purchasing behaviour towards fish and seafood products. Patterns and insights from a sample of international studies. Appetite 2015, 84, 212–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C. The Gender gap is real for crabs. Baltimore Sun. 13 September 2018. Available online: https://digitaledition.baltimoresun.com/tribune/article_popover.aspx?guid=bab0c338-b825-4381-83e9-0564baa4fe38#:~:text=Even%20among%20our%20crustacean%20counterparts,growing%20after%20they%20reach%20maturity (accessed on 17 August 2021).

- Decision 985/QD-TTg, Decision No. 985/QĐ-TTg 2022: Issuance of the National Program for the Development of Aquaculture for the Period 2021–2030, Dated 16 August 2022. Available online: https://english.luatvietnam.vn/decision-no-985-qd-ttg-promulgating-the-national-program-on-aquaculture-development-in-the-2021-2030-peri-228363-doc1.html (accessed on 19 September 2024).

- MARD. Regulation on the Responsibilities of Aquaculture Household Owners for Aquatic Animal Disease Prevention and Control, Dated 12 December 2024; Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health; People’s Committee of Ho Chi Minh City. 2023 Decision No. 6002/QĐ-UBND on the Approval of the Urban Agriculture Development Program in Ho Chi Minh City for the Period 2021–2030, with a Vision to 2050, dated 29 December 2023; Ministry of Health: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Belief, attitude, intention, and behavior: An introduction to theory and research. Philos. Rhetor. 1977, 10, 130–132. [Google Scholar]

- Olsen, S.O. Antecedents of seafood consumption behavior. J. Aquat. Food Prod. Technol. 2004, 13, 79–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackwell, R.D.; Miniard, P.W.; Engel, J.F. Consumer Behavior, Sampling Techniques, 10th ed.; John Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2006; Volume 60, pp. 252–269. [Google Scholar]

- D’Amico, M.; Di Vita, G.; Chinnici, G.; Pappalardo, G.; Pecorino, B. Short food supply chain and locally produced wines: Factors affecting consumer behavior. Ital. J. Food Sci. 2014, 26, 329–334. [Google Scholar]

- Giampietri, E.; Verneau, F.; Del Giudice, T.; Carfora, V.; Finco, A. A theory of planned behaviour perspective for investigating the role of trust in consumer purchasing decision related to short food supply chains. Food Qual. Prefer. 2018, 64, 160–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior: Frequently asked questions. Hum. Behav. Emerg. Technol. 2020, 2, 314–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotler, P.; Olguín, V.C. Marketing Internacional de Lugares y Destinos: Estrategias para la Atracción de Clientes y Negocios en Latinoamérica; Pearson Educación: London, UK, 2006; ISBN 9789702608523. [Google Scholar]

- Annunziata, A.; Pascale, P. Consumers’ behaviours and attitudes toward healthy food products: The case of Organic and Functional foods. In Agricultural and Food Policy Consumer/Household Economics; MDPI: Basel, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohm, H.; Oostindjer, M.; Aschemann-Witzel, J.; Symmank, C.; Almli, V.L.; De Hoodge, I.E.; Normann, A.; Karantininis, K. Consumers in a sustainable food supply chain (COSUS): Understanding consumer behavior to encourage food waste reduction. Foods 2017, 6, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuu, H.H. Applying the theory of planned behavior (TPB) to explain the motivations of consumers of fish in Nha Trang city (Vietnamese). JMST J. 2007, 3, 30–38. [Google Scholar]

- Thuan, N.V.; Danh, V.T. Analysis of factors affecting safe vegetable consumption behavior in Can Tho City. Can Tho Univ. J. Sci. 2011, 17, 113–119. [Google Scholar]

- Nhat, P.T. Factors affecting decision of choosing of supermarket channels when purchasing fresh foods of consumers in Ho Chi Minh City (Vietnamese). Res. Exch. J. 2013, 10, 46–51. [Google Scholar]

- Xe, D.V.; Bao, C.T. Catfish market in the Mekong Delta: Analyzing domestic catfish consumer behavior (Vietnamese). J. Econ. Dev. 2021, 14, 37–41. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, B.; Long, C.; Dong, W.; Shao, Q.J.; Shu, M. Molecular characterization of calreticulin gene in mud crab Scylla paramamosain (Estampador): Implications for the regulation of calcium homeostasis during moult cycle. Aquac. Res. 2016, 47, 3276–3286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honkanen, P.; Young, J. What determines British consumers’ motivation to buy sustainable seafood? Br. Food J. 2015, 117, 1289–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, N.T. Factors affecting consumers’ purchase choice of Vietnamese food products (Vietnamese). AGU Int. J. Sci. 2013, 1, 48–56. [Google Scholar]

- Higuchi, A.; Dávalds, J.; Hernani-Merind, M. Theory of planned behavior applied to fish consumption in modern Metropolitan Lima. Food Sci. Technol. Camp. 2017, 37, 202–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, M.V. Econometrics; Culture and Information Publishing House: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Trong, H.; Ngoc, C.N.M. Analysis of Research Data with SPSS (1 & 2); Hong Duc Publisher: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Bentler, P.M.; Chou, C.P. Practical Issues in Structural Modeling. Sociol. Methods Res. 1987, 16, 78–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Grootel, L.; Nair, L.B.; Klugkist, I.; van Wesel, F. Quantitizing findings from qualitative studies for integration in mixed methods reviewing. Res. Synth. Methods 2020, 11, 413–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendenhall, W.; Beaver, R.J. Introduction to Probability and Statistics, 14th ed.; Cengage Learning: Boston, MA, USA, 2019; p. 214, ISBN-13: 978-8131518502. [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally, J.C.; Bernstein, I.H. Psychometric Theory, 3rd ed; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Sanghvi, T.; Homan, R.; Nguyen, T.; Mahmud, Z.; Walissa, T.; Nersesyan, M.; Preware, P.; Frongillo, E.A.; Matheson, R. Incremental financial costs of strengthening large-scale programs to improve young child nutrition in Bangladesh, Ethiopia, and Vietnam: Retrospective expenditure analysis. Glob. Health 2025, 21, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duy, D.T.; Trung, T.Q.; Lan, T.H.P.; Berg, H.; DA, C.T. Assessment of the impacts of social capital on the profit of shrimp farming production in the Mekong Delta, Vietnam. Aquac. Econ. Manag. 2022, 26, 152–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Mazrooei, N.; Chomo, G.; Omezzine, A. Purchase behavior of consumers for seafood products. Agric. Mar. Sci. 2011, 8, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, T.; Saha, D.; Bhowmik, S.; Nordin, N.; Islam, S.; Ujjaman Nur, A.-A.; Begum, M. Nutritional properties of wild and fattening mud crab (Scylla serrata) in the south-eastern district of Bangladesh. Heliyon 2022, 8, e09696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tri, H.M. Factors affecting students’ purchase decisions green products in Ho Chi Minh City. J. Sci.-Econ. Bus. Adm. 2022, 17, 19–35. [Google Scholar]

- Fishbein, M.; Cappella, J.N. The role of theory in developing effective health communications. J. Commun. 2006, 56, S1–S17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bose, S.; Brown, N. A preliminary investigation of factors affecting seafood consumption behaviour in the inland and coastal regions of Victoria, Australia. J. Consum. Stud. Home Econ. 2000, 24, 257–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thang, D.Q.; Dung, N.T.T.; Nguyen, G.; Dao, Q.T. Factors affecting the consumers’s purchase decision safe food: Case study in Vietnam. J. Manag. Econ. Stud. 2019, 1, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen-Viet, H.; Lam, S.; Nguyen-Mai, H.; Trang, D.T.; Phuong, V.T.; Tuan, N.D.A.; Tan, D.Q.; Thuy, N.T.; Linh, D.T.; Pahm-Duc, P. Decades of emerging infectious disease, food safety, and antimicrobial resistance response in Vietnam: The role of One Health. One Health 2022, 14, 100361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamberg, S.; Ajzen, I.; Schmidt, P. Choice of travel mode in the theory of planned behavior: The roles of past behavior, habit, and reasoned action. Basic Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 25, 175–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, H.; Tam, N.T.; Lan, T.H.P.; Da, C.T. Enhanced food-production efficiencies through integrated farming systems in the Hau Giang province in the Mekong Delta, Vietnam. Agriculture 2024, 14, 1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Respondent Characteristics | Medium | Standard Deviation | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 32 | 8.4 | 20 | 62 |

| Number of family members (people) | 3.7 | 1.4 | 1 | 9 |

| Female ratio (%) | 69 | |||

| Male ratio (%) | 31 | |||

| Education level | ||||

| PhD | 0.75 | |||

| Master’s | 7.46 | |||

| Bachelor’s | 70 | |||

| College | 8.95 | |||

| Intermediate | 5.9 | |||

| High School | 6.94 | |||

| Career (%) | ||||

| Unemployed | 3.7 | |||

| Housewife | 12 | |||

| General laborer | 9 | |||

| Office staff | 60.4 | |||

| Teacher | 2.9 | |||

| Online sales | 12 | |||

| Income (million VND/person/month) | 11 | 15 | 1 | 104 |

| Household food expenses (million VND/month) | 11.2 | 9 | 2 | 70 |

| Respondent Characteristics | Medium | Standard Deviation | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of crab purchases (times/household/year) | ||||

| Times | 2.1 | 1.3 | 1.1 | 12 |

| Purchase rate of each type of crab (%) | ||||

| Crab with roe | 53.7 | |||

| Crab meat | 56.0 | |||

| Crab bucket | 6.0 | |||

| Purchase volume of each type of crab (kg/household/year) | ||||

| Crab with roe | 3.5 | 2.8 | 1.0 | 20 |

| Crab meat (Y crab) | 5.1 | 2.9 | 0.5 | 13 |

| Crab bucket | 6.0 | 2.9 | 2.0 | 10 |

| Amount spent on each type of crab (1000 VND/household/year) | ||||

| Crab with roe | 1454 | 1040 | 280 | 6420 |

| Crab meat (Y crab) | 1656 | 1042 | 175 | 5030 |

| Crab bucket | 976.0 | 386.0 | 420 | 1560 |

| Numerical Order | Observation Variable Name | Total Variable Correlation Coefficient | Cronbach’s Alpha Coefficient | Eliminated Variable |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NU1 | Fresh crab ensures freshness. | 0.87 | 0.92 | |

| NU2 | Fresh crab ensures high minerals. | 0.86 | 0.93 | |

| NU3 | Fresh crab has sweet meat. | 0.87 | 0.92 | |

| NU4 | Fresh crab tastes better than canned products. | 0.87 | 0.92 | |

| FHS1 | Fresh crab does not contain toxic substances. | 0.74 | 0.83 | |

| FHS2 | Fresh crab ensures clear origin. | 0.76 | 0.82 | |

| FHS3 | Fresh crab does not contain preservatives. | 0.67 | 0.84 | |

| FHS4 | Fresh crab does not contain parasites. | 0.63 | 0.85 | |

| FHS5 | Fresh crab does not cause allergies. | 0.66 | 0.85 | |

| PR1 | The price of fresh crab is an important issue for me. | 0.88 | 0.89 | |

| PR2 | The price of fresh crab is commensurate with the quality. | 0.87 | 0.82 | |

| PR3 | The price of fresh crab is higher than that of shrimp. | 0.74 | 0.84 | X |

| PR4 | The price of fresh crab is suitable for my family’s income. | 0.87 | 0.89 | |

| CO1 | Fresh crab has a variety of types to choose from. | 0.81 | 0.94 | |

| CO2 | Fresh crab is easy to find everywhere. | 0.82 | 0.93 | |

| CO3 | Fresh crab is convenient for processing. | 0.83 | 0.96 | |

| CO4 | Fresh crab is easy to use after processing. | 0.83 | 0.90 | |

| PD1 | I decided to buy crab because of its high nutrition. | 0.91 | 0.91 | |

| PD2 | I decided to buy crab because of food safety. | 0.77 | 0.96 | X |

| PD3 | I decided to buy crab sea because the price is suitable for family. | 0.90 | 0.90 | |

| PD4 | I decided to buy sea crab because of the high convenience. | 0.91 | 0.90 |

| Observation Variable | Factors | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| 0.90 | |||

| 0.89 | |||

| 0.91 | |||

| 0.89 | |||

| 0.84 | |||

| 0.85 | |||

| 0.79 | |||

| 0.77 | |||

| 0.78 | |||

| 0.87 | |||

| 0.86 | |||

| 0.89 | |||

| 0.88 | |||

| 0.94 | |||

| 0.96 | |||

| 0.93 | |||

| KMO coefficients | 0.706 | |||

| Group of Factors | Factor Name | Medium | Evaluate ** |

|---|---|---|---|

| N1 | Nutritional awareness | 3.6 | affect |

| N2 | Food safety awareness | 3.8 | affect |

| N3 | Perception of convenience | 3.6 | affect |

| N4 | Price awareness | 3.3 | neutral |

| KMO Coefficient | 0.77 | |

|---|---|---|

| Bartlett’s test | Chi-square value | 732 |

| df | 3.0 | |

| Sig—observational significance level | 0.000 | |

| Load Factor | |

|---|---|

| Purchase decision 1 | 0.97 |

| Purchase decision 3 | 0.97 |

| Purchase decision 4 | 0.95 |

| Eigenvalue | 2.80 |

| Cumulative variance | 0.93 |

| Variable Name | VIF | 1/VIF |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 1.14 | 0.87 |

| Spending | 1.1 | 0.91 |

| Gender | 1.03 | 0.97 |

| Education | 1.03 | 0.97 |

| N1 Nutritional awareness | 1.01 | 0.99 |

| N2 Food safety awareness | 1.04 | 0.96 |

| N3 Perception of convenience | 1.00 | 0.96 |

| N4 Price awareness | 1.03 | 0.99 |

| Mean VIF | 1.05 |

| Symbol | Variable Name | Estimated Coefficient β | Standard Error | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| X1 | Age (years) | 0.001 ns | 0.003 | 0.659 |

| X2 | Gender (1—male; 0—female) | −0.02 ns | 0.049 | 0.650 |

| X3 | Education (years of schooling) | −0.08 ns | 0.014 | 0.589 |

| X4 | Income (million VND/month) | −0.04 ns | 0.031 | 0.235 |

| N1 | Nutritional awareness | 0.914 *** | 0.022 | 0.000 |

| N2 | Food safety awareness | 0.036 ns | 0.023 | 0.119 |

| N3 | Perception of convenience | 0.256 *** | 0.022 | 0.000 |

| N4 | Price awareness | −0.014 ns | 0.022 | 0.547 |

| Constant | 0.193 ns | 0.247 | 0.435 | |

| Y | Decision to buy fresh crab | |||

| Number of observations | 200 | |||

| p-value | 0.000 | |||

| Coefficient of determination R2 (%) | 90 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Danh, L.N.; Duy, D.T.; Nhan, D.H.; Da, C.T. Factors Influencing Consumer Behavior and Purchasing Decisions Regarding Mud Crabs (Scylla paramamosain) in the Major Cities of Vietnam. Foods 2025, 14, 2198. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14132198

Danh LN, Duy DT, Nhan DH, Da CT. Factors Influencing Consumer Behavior and Purchasing Decisions Regarding Mud Crabs (Scylla paramamosain) in the Major Cities of Vietnam. Foods. 2025; 14(13):2198. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14132198

Chicago/Turabian StyleDanh, Le Ngoc, Duong The Duy, Doan Hoai Nhan, and Chau Thi Da. 2025. "Factors Influencing Consumer Behavior and Purchasing Decisions Regarding Mud Crabs (Scylla paramamosain) in the Major Cities of Vietnam" Foods 14, no. 13: 2198. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14132198

APA StyleDanh, L. N., Duy, D. T., Nhan, D. H., & Da, C. T. (2025). Factors Influencing Consumer Behavior and Purchasing Decisions Regarding Mud Crabs (Scylla paramamosain) in the Major Cities of Vietnam. Foods, 14(13), 2198. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14132198