New Labeling Rules for Wine: Wine Alcohol-Derived Calories and Polyphenol Consumption on Health

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. New Labeling Rules for Wine

1.2. Spanish Regulatory Wine Classification, Winemaking Procedure, and Common Additives in Wine

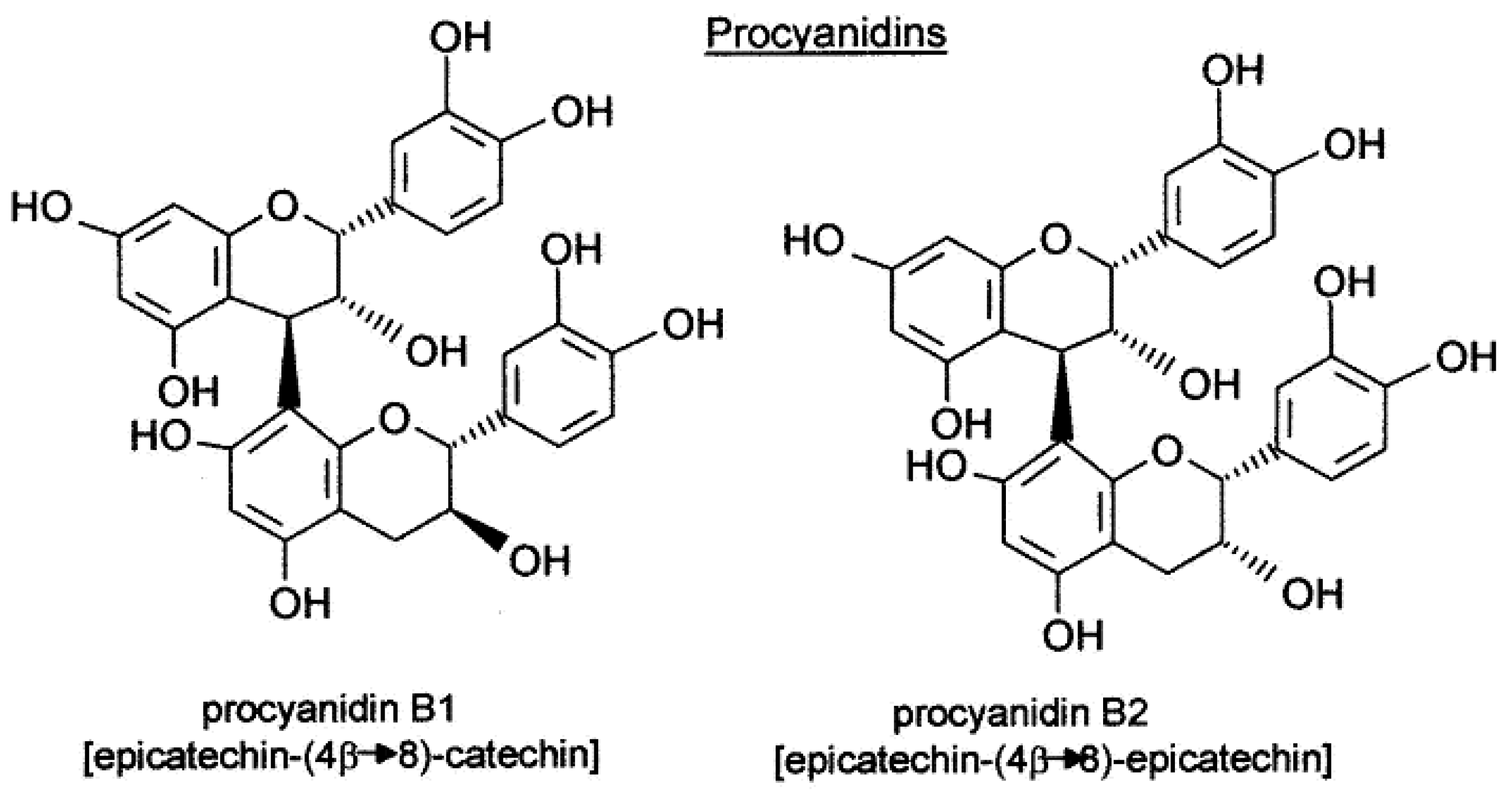

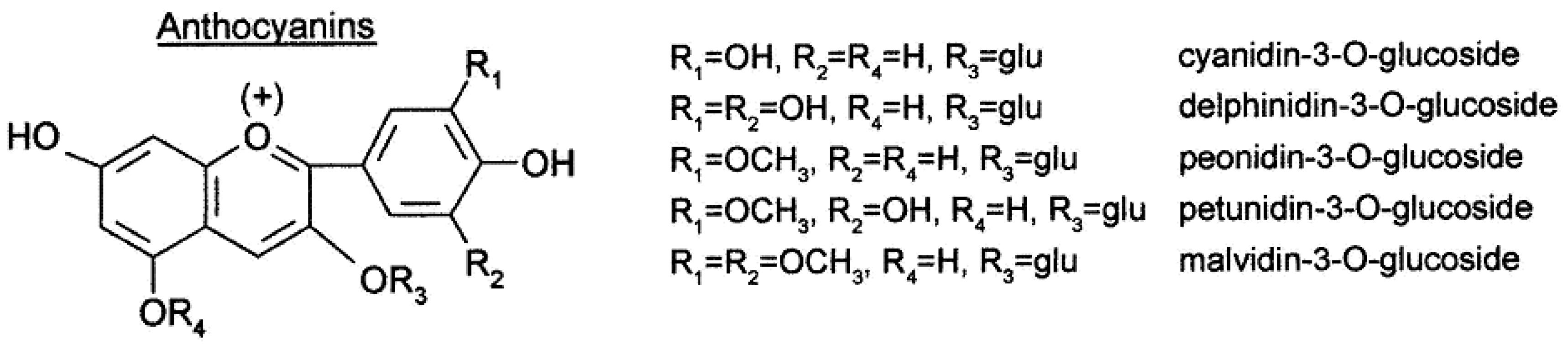

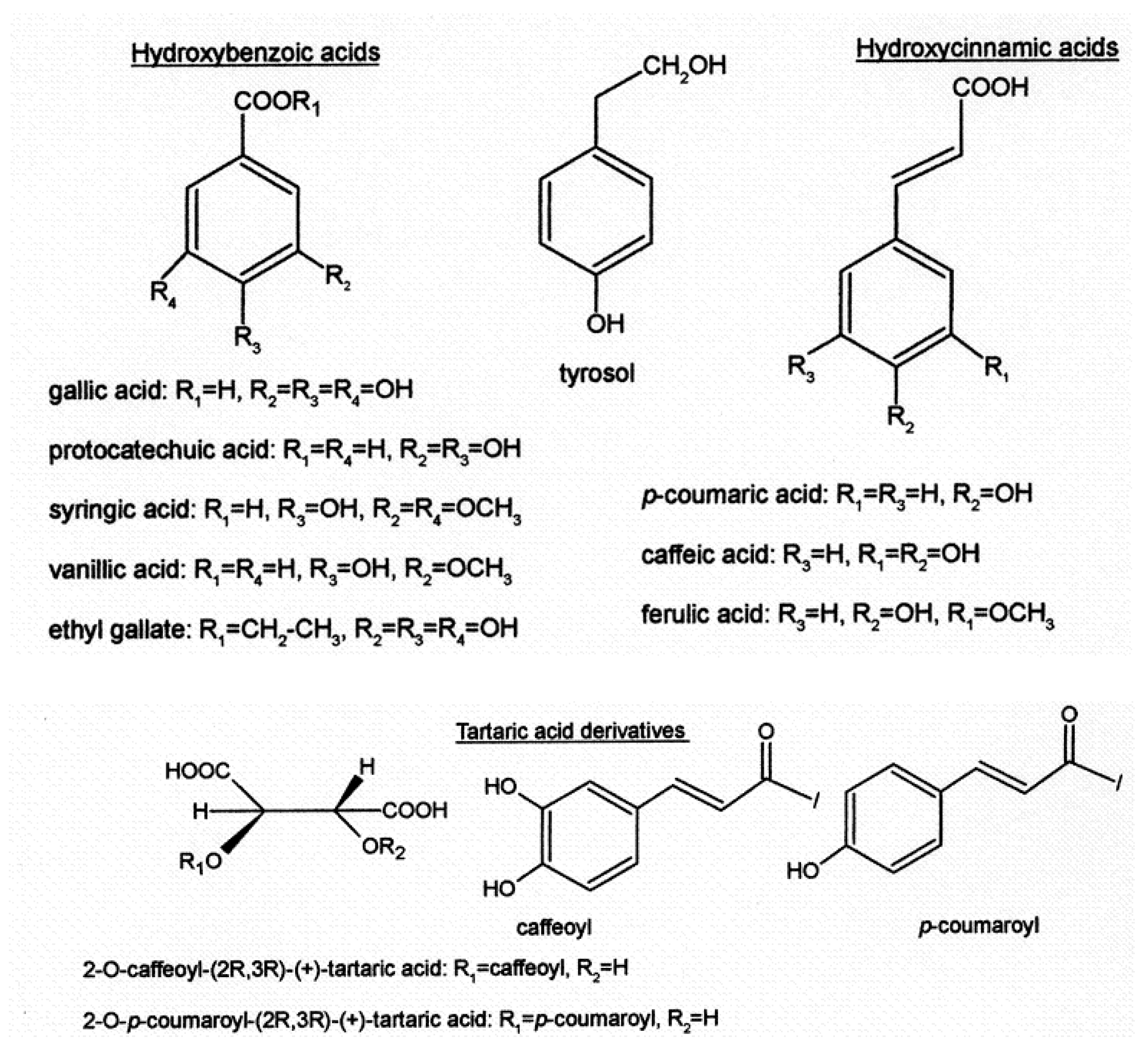

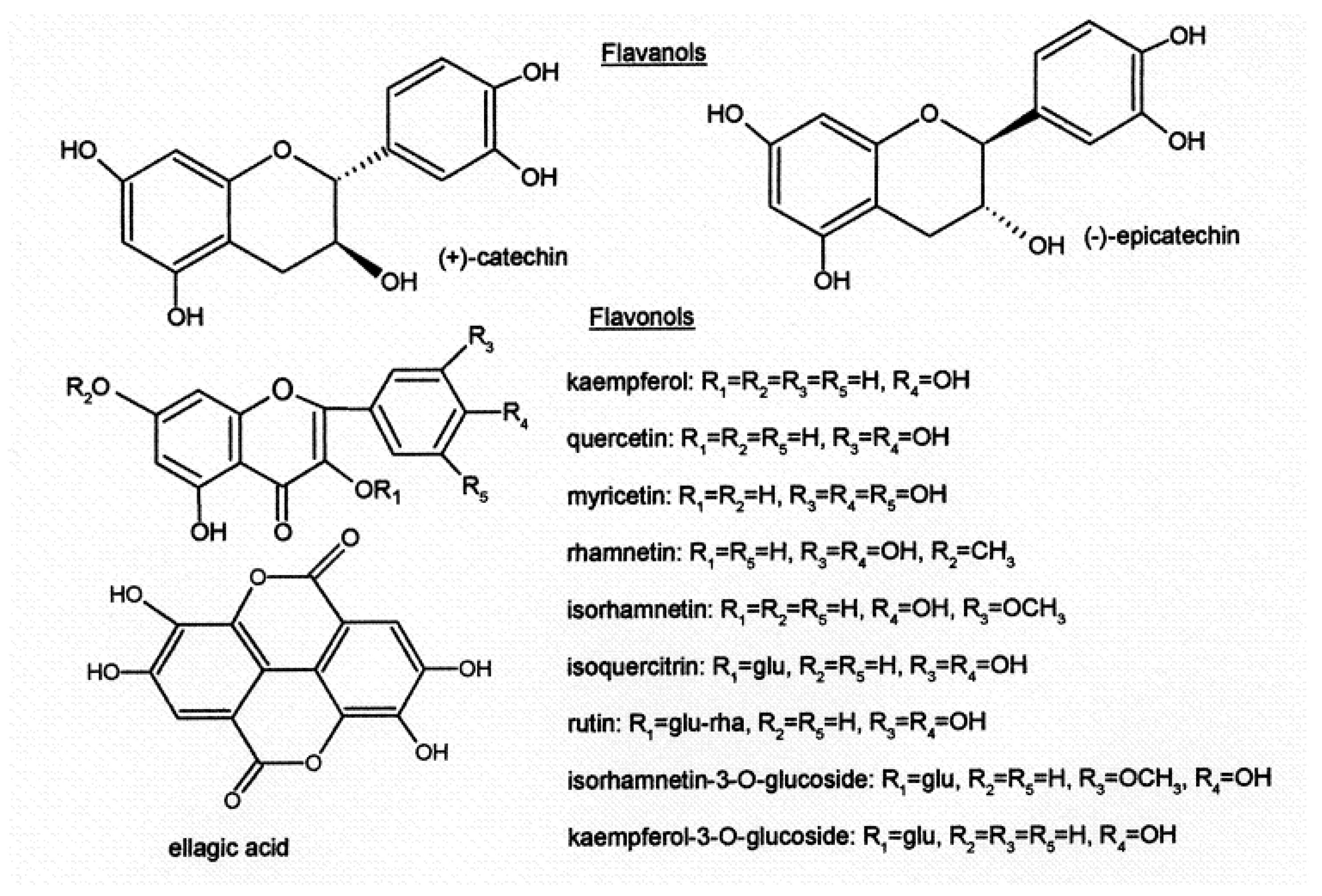

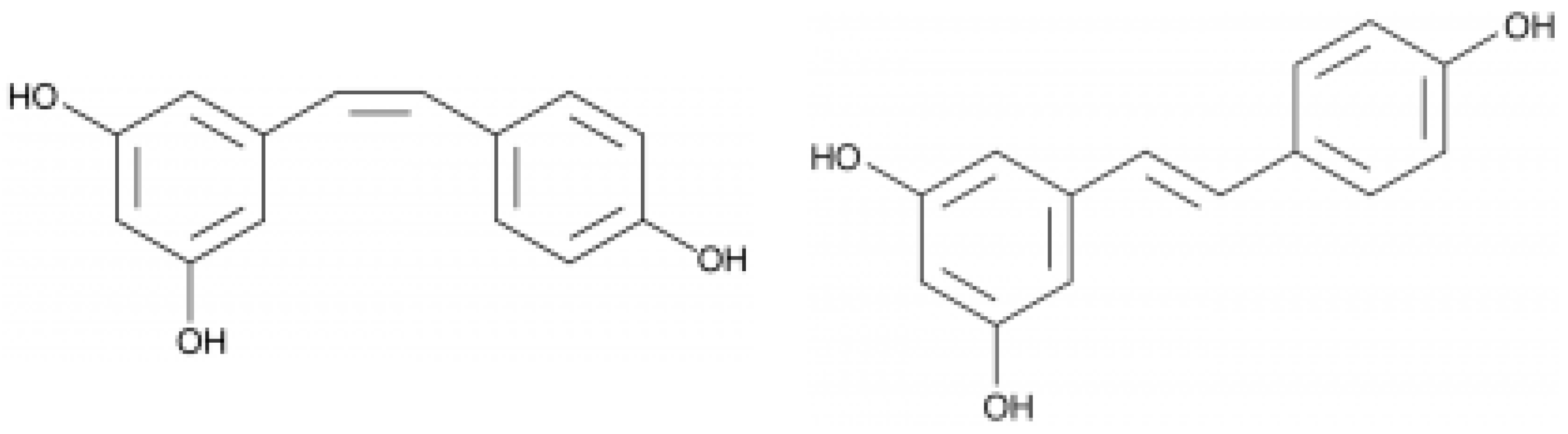

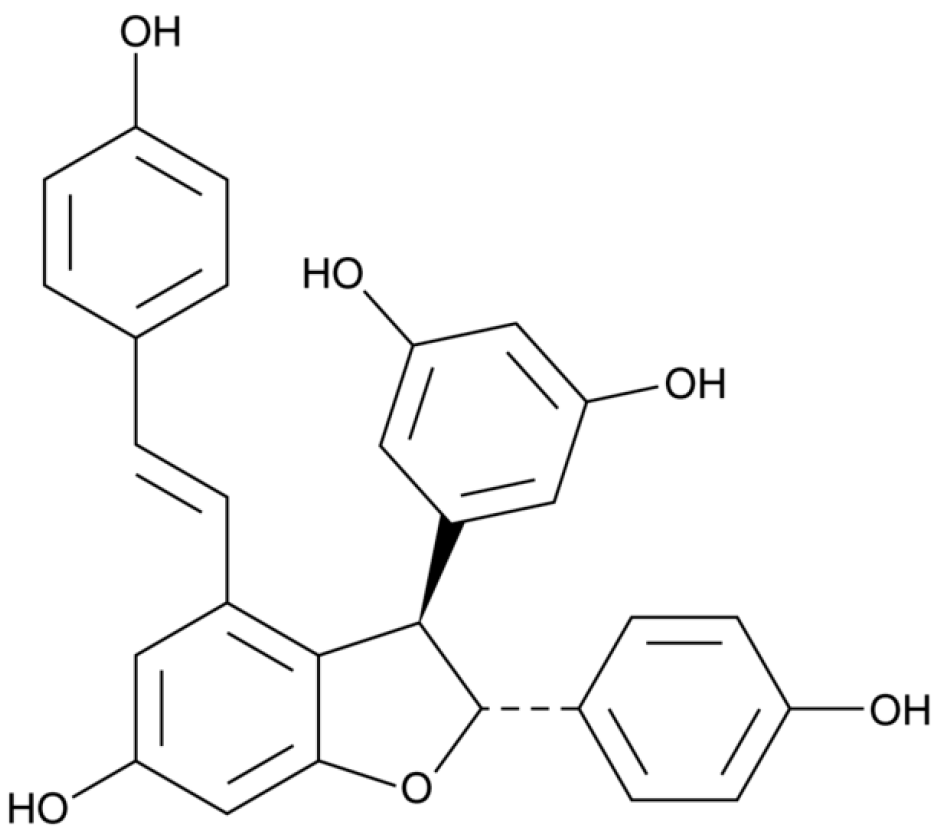

1.3. Grape Polyphenol Synthesis, Structure, and Composition

1.4. Effects of Climate, Soil, and Vineyard Location on Grape Composition

1.5. Health Effects of Wine Polyphenols

1.5.1. Metabolic Syndrome

1.5.2. Alcohol Intake

1.5.3. Coronary Heart Disease (CHD)

1.5.4. Dyslipidemia and Diabetes

1.6. Bioavailability of Anthocyanins and Procyanidins

1.7. Synergy of Wine Polyphenols with Food

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sampling and Winemaking

2.2. Composition of Priorat Wines

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Anthocyanin and Procyanidin Analysis of the Wines

3.2. Estimation of Polyphenol Intake in Humans

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Regulation (EU) 2021/2117. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=uriserv:OJ.L_.2021.435.01.0262.01.ENG (accessed on 4 December 2023).

- Regulation (EU) 1169/2011. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=OJ%3AL%3A2011%3A304%3A0018%3A0063%3AEN%3APDF (accessed on 4 December 2023).

- Regulation (EU) 2019/934. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg_del/2019/934/oj (accessed on 4 December 2023).

- Ávalos-García, A.; Pérez-Urria Carril, E. Serie Fisiología Vegetal. Metabolismo secundario de plantas. La Reduca (Biol.) 2009, 2, 119–145. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Ortiz, A.; Mateo-Sanz, J.M.; Nadal, M.; Lampreave, M. Water stress assessment on grapevines by using classification and regression trees. Plant Direct 2021, 5, e00319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lea, C.Y.; Jaworsky, A. Phenolic compounds in the white grapes grown in New York. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 1987, 38, 277–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lea, A.G.H. Flavour, colour, and stability in fruit products: The effect of polyphenols. In Plant Polyphenols; Hemingway, R.W., Laks, P.E., Eds.; Plenum: New York, NY, USA, 1992; pp. 827–837. [Google Scholar]

- Romeyer, F.M.; Macheix, J.J.; Goiffon, J.P.; Reminiak, C.C.; Sapis, J.C. The browning capacity of grapes. Changes and importante of hydroxycinnamic acid tartaric acid esters during development and maturation of the fruit. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1983, 31, 346–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singleton, V.L.; Trousdale, E. White wine phenolics: Varietal and processing differences as shown by HPLC. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 1983, 34, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, D.I.; Lombard, P.B. Environmental and management practices affecting grape composition and wine quality—A review. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 1993, 44, 409–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harborne, J.B.; Grayer, R.J. The anthocyanins. In The Flavonoids; Harborne, J.B., Ed.; Chapman and Hall: London, UK, 1988; pp. 1–20, 146. [Google Scholar]

- Brouillard, R. Flavonoids and flower color. In The Flavonoids; Harborne, J.B., Ed.; Chapman and Hall: London, UK, 1988; pp. 525–538. [Google Scholar]

- Boulton, R. The copigmentation of anthocyanins and its role in the color of red wine: A critical review. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 2001, 52, 67–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plumb, G.W.; de Pascual-Teresa, S.; Santos-Buelga, C.; Cheynier, V.; Williamson, G. Antioxidant properties of catechins and proanthocyanidins: Effect of polymerisation, galloylation and glycosylation. Free Radic. Res. 1998, 29, 351–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazza, G.; Fukumoto, L.; Delaquis, P.; Girard, B.; Ewert, B. Anthocyanins, phenolics, and colour of Cabernet Franc, Merlot, and Pinot Noir wines from British Columbia. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1999, 47, 4009–4017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheynier, V.; Moutounet, M.; Sarni-Manchado, P. Les composés phénoliques. In Oenologie, Fondements Scientifiques et Tecnologiques; Flanzy, C., Ed.; Lavoisier TEc&Doc: Paris, France, 1998; pp. 124–164. [Google Scholar]

- Broussaud, F.; Cheynier, V.; Asselin, C.; Moutounet, M. Flavonoid compositional differences of grapes among site test plantings of Cabernet franc. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 1999, 50, 277–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojeda, H.; Andary, C.; Creaba, E.; Carbonneau, A.; Deloire, A. Influence of pre- and postveraison water deficit on synthesis and concentration of skin phenolic compounds during berry growth of Vitis vinifera var. Shiraz. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 2002, 53, 149–157. [Google Scholar]

- Šmidrkal, J.; Řiháková, Z.; Plocková, M. Antifungal activity of lauric acid derivatives against Aspergillus niger. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2001, 213, 488–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baur, J.A.; Sinclair, D.A. Therapeutic potential of resveratrol: The in vivo evidence. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2006, 5, 493–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribéreau-Gayon, P.; Glories, Y.; Maujean, A.; Dubourdieu, D. Tratado de Enología: Química del vino Estabilización y Tratamientos; Ediciones Mundi-Prensa: Madrid, Spain, 2003; Volume 2, p. 537. [Google Scholar]

- Valls, J.; Millán, S.; Martí, M.P.; Borràs, E.; Arola, L. Advanced separation methods of food anthocyanins, isoflavones and flavanols. J. Chromatogr. A 2009, 1216, 7143–7172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vivas, N. Les conditions d’élaboration des vins rouges destinés à un élevage en barriques. Rev. Oenol. 1993, 68, 27–33. [Google Scholar]

- Edo, M.; Nadal, M.; Sánchez-Ortiz, A.; Lampreave, M. Anthocyanin composition in Carignan and Grenache grapes and wines affected by plant vigour and bunch uniformity. J. Int. Sci. Vigne Vin. 2014, 48, 201–217. [Google Scholar]

- Nadal, M.; Sánchez-Ortiz, A. Territoires du vin. El Priorat. Territoires du vin. 2011. Available online: http://revuesshs.u-bourgogne.fr/territoiresduvin/document.php?id=942UTH (accessed on 4 December 2023).

- Fernández-Pachón, M.S.; Villaño, D.; García-Parrilla, M.C.; Troncoso, A.M. Antioxidant activity of wines and relation with their polyphenolic composition. Anal. Chim. Acta 2004, 513, 113–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waterhouse, A.L.; Ignelzi, S.; Shirley, J.R. A comparison of methods for quantifying oligomeric proanthocyanidins from grape seed extracts. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 2000, 51, 383–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clifford, M.N.; Scalbert, A. Ellagitannins, occurrence in food, bioavailability, and cancer prevention. J. Food Sci. Agric. 2000, 80, 1118–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stintzing, F.C.; Carle, R. Functional Properties of Anthocyanins and Betalains in Plants, Food, and in Human Nutrition. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2004, 15, 19–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Bowerman, N.A.; Salama, J.K.; Schmidt, H.; Spiotto, M.T.; Schietinger, A.; Yu, P.; Fu, Y.X.; Weichselbaum, R.R.; Rowley, D.A.; et al. Induced sensitization of tumor stroma leads to eradication of established cancer by T cells. J. Exp. Med. 2007, 204, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jayaprakasam, B.; Vareed, S.K.; Olson, L.K.; Nair, M.G. Insulin secretion by bioactive anthocyanins and anthocyanidins present in fruits. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005, 53, 28–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsui, T.; Ueda, T.; Oki, T.; Sugita, K.; Terahara, N.; Matsumoto, K. Alpha-glucosidase inhibitory action of natural acylated anthocyanins. 1. Survey of natural pigments with potent inhibitory activity. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2001, 49, 1948–1951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tall, J.M.; Seeram, N.P.; Zhao, C.; Nair, M.G.; Meyer, R.A.; Raja, S.N. Tart cherry anthocyanins suppress inflammation-induced pain behavior in rat. Behav. Brain Res. 2004, 153, 181–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, J.A.; Shukitt-Hale, B.; Gemma, C. Reversing the deleterious effects of aging on neuronal communication and behaviour: Beneficial properties of fruit polyphenolic compounds. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2005, 81, 313S–316S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brennan, R.M. Currants gooseberries. In Fruit Breeding, Vol. II: Vine and Small Fruits Crops; Janick, J., Moore, J.N., Eds.; John Wiley and Sons, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1996; pp. 191–295. [Google Scholar]

- Serafini, M.; Maiani, G.; Ferro-Luzzi, A. Alcohol-free red wine enhances plasma antioxidant capacity in humans. J. Nutr. 1998, 128, 1003–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez-Tortosa, C.; Andersen, Ø.M.; Cabrita, L.; Gardner, P.T.; Morrice, P.C.; Wood, S.G.; Duthie, S.J.; Collins, A.R.; Duthie, G.G. Anthocyanin-rich extract decreases indices of lipid peroxidation and DNA damage in vitamin E-depleted rats. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2001, 31, 1033–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuda, T.; Horio, F.; Osawa, T. Dietary cyanidin 3-O-h-d-glucoside increases ex vivo oxidation resistance of serum in rats. Lipids 1998, 33, 583–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuda, T.; Horio, F.; Kitoh, J.; Osawa, T. Protective effects of dietary cyanidin 3-O-h-d-glucoside on ischemia-reperfusion injury in rats. Arch. Biochem. Biophys 1999, 368, 361–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuda, T.; Horio, F.; Osawa, T. Cyanidin 3-O-h-d-glucoside suppresses nitric oxide production during a zymosan treatment in rats. J. Nutr. Sci. Vitaminol. 2002, 48, 305–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuda, T.; Horio, F.; Kato, Y.; Osawa, T. Cyanidin 3-O-h-d-glucoside attenuates the hepatic ischemia-reperfusion injury through a decrease in the neutrophil chemoattractant production in rats. J. Nutr. Sci. Vitaminol. 2002, 48, 134–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Tsuda, T.; Horio, F.; Uchida, K.; Aoki, H.; Osawa, T. Dietary cyanidin 3-O-h-d-glucoside-rich purple corn color prevents obesity and ameliorates hyperglycemia in mice. J. Nutr. 2003, 133, 2125–2130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motilva, M.J.; Macià, A.; Romero, M.P.; Rubió, L.; Mercader, M.; González-Ferrero, C. Human bioavailability and metabolism of phenolic compounds from red wine enriched with free or nano-encapsulated phenolic extract. J. Funct. Foods 2016, 25, 80–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inkung, B.; Shin, C. Prospective study of alcohol consumption and metabolic syndrome. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2008, 87, 1455–1463. [Google Scholar]

- Lippi, G.; Franchini, M.; Favaloro, E.J.; Targher, G. Moderate red wine consumption and cardiovascular disease risk: Beyond the “French paradox”. Semin. Thromb. Hemost. 2010, 36, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hertog, M.G.; Kromhout, D.; Aravanis, C.; Blackburn, H.; Buzina, R.; Fidanza, F.; Giampaoli, S.; Jansen, A.; Menotti, A.; Nedeljkovic, S. Flavonoid intake and long-term risk of coronary heart disease and cancer in the Seven Countries Study. Arch. Intern. Med. 1995, 155, 381–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamont, K.T.; Somers, S.; Lacerda, L.; Opie, L.H.; Lecour, S. Is red wine a safe sip away from cardioprotection? Mechanisms involved in resveratrol -and melatonin- induced cardioprotection. J. Pineal Res. 2011, 50, 374–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Opie, L.H.; Lecour, S. The red wine hypothesis: From concepts to protective signalling molecules. Eur. Heart J. 2007, 28, 1683–1693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szmitko, P.E.; Verma, S. Red Wine and Your Heart. Circulation 2005, 111, e10–e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardevol, A.; Blade, C.; Salvado, M.J.; Arola, L. Changes in lipolysis and hormone-sensitive lipase expression caused by procyanidins in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Int. J. Obes. Relat. Metab. Disord. 2000, 24, 319–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuda, T.; Yuki, U.; Hiromitsu, A.; Takatoshi, K.; Fumihiko, H.; Nobuyuki, T.; Teruo, K.; Toshihiko, O. Anthocyanin enhances adipocytokine secretion and adipocyte-specific gene expression in isolated rat adipocytes. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2004, 316, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuda, T.; Yuki, U.; Hitoshi, K.; Toshikazu, Y.; Toshihiko, O. Gene expression profile of isolated rat adipocytes treated with anthocyanins. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids 2005, 1733, 137–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamauchi, T.; Kamon, J.; Waki, H.; Murakami, K.; Motojima, K.; Komeda, K.; Ide, T.; Kubota, N.; Terauchi, Y.; Tobe, K.; et al. The mechanisms by which both heterozygous peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARgamma) deficiency and PPARgamma agonist improve insulin resistance. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 41245–41254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schulze, M.B.; Liu, S.; Rimm, E.B.; Manson, J.E.; Willett, W.C.; Hu, F.B. Glycemic index, glycaemic load, and dietary fibre intake and incidence of type 2 diabetes in younger and middle-aged women. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2004, 80, 348–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griendling, K.K.; FitzGerald, G.A. Oxidative stress, and cardiovascular injury: Part I: Basic mechanisms and in vivo monitoring of ROS. Circulation 2003, 108, 1912–1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frantz, S.; Calvillo, L.; Tillmanns, J.; Elbing, I.; Dienesch, C.; Bischoff, H.; Ertl, G.; Bauersachs, J. Repetitive postprandial hyperglycemia increases cardiac ischemia/reperfusion injury: Prevention by the alpha-glucosidase inhibitor acarbose. FASEB J. 2005, 19, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vincent, A.M.; McLean, L.L.; Backus, C.; Feldman, E.L. Short-term hyperglycemia produces oxidative damage and apoptosis in neurons. FASEB J. 2005, 19, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinent, M.; Blay, M.; Bladé, M.C.; Salvadó, M.J.; Arola, L.; Ardévol, A. Grape Seed-Derived Procyanidins Have an Antihyperglycemic Effect in Streptozotocin-Induced Diabetic Rats and Insulinomimetic Activity in Insulin-Sensitive Cell Lines. Endocrinology 2004, 145, 4985–4990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordain, L.; Melby, C.; Hamamoto, A.E.; O’Neill, D.S.; Cornier, M.A.; Barakat, H.A. Influence of moderate chronic wine consumption on insulin sensitivity and other correlates of syndrome X in moderately obese women. Metab. Clin. Exp. 2000, 49, 1473–1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavalgante, A.R.; Carisa, D.; de Souza, L.M.; Vera de Rosso, V. Bioavailability of anthocyanins: Gaps in knowledge, challenges, and future research. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2018, 68, 31–40. [Google Scholar]

- Williamson, G.; Manach, C. Bioavailability and bioefficacy of polyphenols in humans. II Review of 93 intervention studies. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2005, 81, 243S–255S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bell, J.R.C.; Donovan, J.L.; Wong, R.; Waterhouse, A.L. (+)-Catechin in human plasma after ingestion of a single serving of reconstituted red wine. Am.J.Clin.Nutr. 2000, 71, 103–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Alonso, J.; Ros, G.; Vidal-Guevara, M.L.; Periago, M.J. Acute intake of phenolic-rich juice improves antioxidant status in healthy subjects. Nutr. Res. 2006, 117, 326–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baba, S.; Osakabe, N.; Natsume, M.; Muto, Y.; Takizawa, T.; Terao, J. In vivo comparison of the bioavailability of (+)-Catechin, (-)-epicatechin and their mixture in orally administered rats. J. Nutr. 2001, 131, 2885–2891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandes, I.; Faria, A.; De Freitas, V.; Calhau, C.; Mateus, N. Multiple-approach studies to assess anthocyanin bioavailability. Phytochem. Rev. 2015, 14, 899–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, F.; Oliveira, H.; Brás, N.; Fernandes, I.; Cruz, L.; De Freitas, V.; Mateus, N. In vitro gastrointestinal absorption of red wine anthocyanins—Impact of structural complexity and phase II metabolization. Food Chem. 2020, 317, 126398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, J.A.; Kasum, C.M. Dietary flavonoids: Bioavailability, metabolic effects, and safety. Annu. Review Nutr. 2002, 22, 19–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.Y.; Liu, H.Q.; Xie, K.Q.; Yin, L.-L.; Li, Y.; Kwik-Uribe, C.L.; Zhu, X.Z. Procyanidin dimer B2[epicatechin-(4β-8)-epicatechin] supresses the expresión of cyclooxygenase-2 in endotoxin-treated monocytic cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2006, 345, 508–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crespy, V.; Aprikian, O.; Morand, C.; Besson, C.; Manach, C.; Demigne, C.; Reitman, C. Bioavailability of phloretin and phloridzin in rats. J. Nutr. 2001, 131, 3227–3230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitaglione, P.; Donnarumma, G.; Napolitano, A.; Galvano, F.; Gallo, A.; Scalfi, L.; Fogliano, V. Protocatechuic Acid Is the Major Human Metabolite of Cyanidin-Glucosides. Am. Soc. Nutr. J. Nutr. 2007, 137, 2043–2048. [Google Scholar]

- Nicolin, V.; Grill, V.; Micali, F.; Narducci, P.; Passamonti, S. Immunolocalisation of bilitranslocase in mucosecretory and parietal cells of the rat gastric mucosa. J. Mol. Histol. 2005, 36, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, F.; Yang, P.; Wang, H.; Fernandes, I.; Mateus, N.; Liu, Y. Digestion and absorption of red grape and wine anthocyanins through the gastrointestinal tract. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 83, 211–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schönfeldt, H.C.; Pretorius, B.; Hall, N. Bioavailability of Nutrients. In Encyclopedia of Food and Health; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2016; pp. 401–406. ISBN 9780123849533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cilla, A.; Gonzalez-Sarrias, A.; Tomas-Barberan, F.A.; Espic, J.C.; Barbera, R. Availability of polyphenols in fruit beverages subjected to in vitro gastrointestional digestion and their effects on proliferation, cell-cycle, and apoptosis in human colon cancer Caco-2 cells. Food Chem. 2009, 114, 813–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argyri, K.; Komatis, M.; Kapsokefalou, M. Iron decreases the antioxidant capacity of red wine under conditions of in vitro digestion. Food Chem. 2005, 96, 281–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDougall, G.J.; Fyffe, S.; Dobson, P.; Stewart, D. Anthocyanins from red wine-Their Stability Ander simulated gastrointestinal digestion. Phytochemistry 2005, 66, 2540–2548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soleas, G.J.; Diamandis, E.P.; Goldberg, D.M. Resveratrol: A molecule whose time has come? And gone? Clin. Biochem. 1997, 30, 91–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, J.A.; Benedict, F.G. A Biometric Study of Human Basal Metabolism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1918, 4, 370–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Wang, Z.; Li, Y.; Liu, Q.; Yuan, C. Survey of the phenolic content and antioxidant properties of wines from five regions of China according to variety and vintage. Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 169, 114004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Class of Wine Antioxidants | Compound |

|---|---|

| Flavanols | (+)-catechin, (-)-epicatechin |

| Hydroxybenzoic acids | gallic acid, protocatechuic acid, syringic acid vanillic acid, ethyl gallate, ellagic acid |

| Hydroxycinnamic acids | p-coumaric acid, o-coumaric acid, caffeic acid, ferulic acid |

| Tartaric acid and derivatives | caftaric acid (2-O-caffeoyl-(2R,3R)-(+)-tartaric acid) fertaric acid (2-O-feruloyl-(2R,3R)-(+)-tartaric acid) coutaric acid (2-O-p-coumaryl-(2R,3R)-(+)-tartaric acid) |

| Proanthocyanins | procyanidin B1, procyanidin B2 |

| Phenols | tyrosol, hydroxytyrosol, 4-ethylguaiacol, tryphtophol |

| Flavonols | kaempherol, quercetin, rhamnetin, isorhamnetin, myricetin, kaempherol-3-O- glucoside, isorhamnetin-3-O-glucoside, isoquercitrin, rutin |

| Anthocyanins (coumaroylated, acylated, pyranoanthocyanins) | cyanidin-3-O-glucoside, delphinidin-3-O-glucoside, peonidin-3-O-glucoside, petunidin-3-O-glucoside, malvidin-3-O-glucoside, Vitisin A, Vitisin B |

| Resveratrols | cis-resveratrol, trans-resveratrol, trans-piceid, cis-piceid, trans-ε-viniferin α-viniferin |

| Origin | Phenolic Compounds |

|---|---|

| Seed | gallic acid, (+)-catechin, epicatechin, dimeric procyanidin, proanthocyanins |

| Skin | proanthocyanins, ellagic acid, myricetin, quercetin, kaempferol, trans-resveratrol |

| Leaf | myricetin, ellagic acid, kaempferol, quercetin, gallic acid |

| Stem | rutin, quercetin 3-O-glucuronide, trans-resveratrol, astilbin |

| Raisin | hydroxycinnamic acid, hydroxymethylfurfural |

| Red wine | malvidin-3-glucoside, peonidin-3-glucoside, cyanidin-3-glucoside, petunidin-3-glucoside, catechin, quercetin, resveratrol, hydroxycinnamic acid |

| Wine | Site 1 | Site 2 | Site 3 | Site 4 | Site 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total ANT (mg/L) | 398.4 ± 9.6 a | 466.6 ± 4.0 b | 470.5 ± 22.0 b | 432.9 ± 22.8 ab | 451.5 ± 6.3 b |

| Tannins (g/L) | 2.9 ± 0.2 c | 2.4 ± 0.2 a | 2.2 ± 0.3 a | 1.7 ± 0.1 b | 1.4 ± 0.1 b |

| DMACH (mg/L) | 388.8 ± 22.9 a | 361.4 ± 14.4 a | 324.0 ± 7.9 b | 295.6 ± 8.0 bc | 263.1 ± 4.5 c |

| pH | 3.17 ± 0.1 ac | 3.27 ± 0.0 abc | 3.28 ± 0.0 abc | 3.35 ± 0.0 b | 3.21 ± 0.0 c |

| TTA (g/L) | 6.63 ± 0.2 ac | 6.40 ± 0.2 c | 6.39 ± 0.0 c | 6.85 ± 0.1 a | 7.62 ± 0.1 b |

| ABV (%) | 16.10 ± 0.4 a | 15.20 ± 0.6 abc | 14.80 ± 0.1 bde | 14.50 ± 0.2 ce | 15.40 ± 0.2 ad |

| Wine | Site 1 | Site 2 | Site 3 | Site 4 | Site 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| malvidin-3-G | 164.1 ± 4.8 a | 217.1 ± 4.5 d | 222.6 ± 6.3 cd | 203.6 ± 7.4 b | 226.8 ± 1.8 c |

| petunidin-3-G | 7.6 ± 0.4 a | 8.8 ± 2.3 b | 7.7 ± 2.0 a | 5.5 ± 1.8 a | 6.9 ± 2.0 a |

| delphinidin-3-G | 2.0 ± 1.7 a | 2.7 ± 1.0 b | 2.2 ± 1.8 a | 2.0 ± 1.3 a | 2.6 ± 0.6 a |

| peonidin-3-G | 4.6 ± 0.2 b | 5.2 ± 0.1 d | 5.5 ± 0.1 e | 3.5 ± 0.0 a | 4.7 ± 0.0 c |

| cyanidin-3-G | 0.3 ± 0.0 b | 0.3 ± 0.1 ab | 0.3 ± 0.0 b | 0.2 ± 0.0 a | 0.3 ± 0.0 b |

| malvidin-3-AG | 32.3 ± 1.6 a | 57.1 ± 1.9 c | 54.8 ± 0.6 b | 59.5 ± 1.8 c | 64.6 ± 1.5 d |

| petunidin-3-AG | 0.8 ± 0.0 a | 1.1 ± 0.0 d | 1.0 ± 0.0 c | 0.9 ± 0.0 b | 0.9 ± 0.0 b |

| delphinidin-3-AG | 0.3 ± 0.0 a | 0.4 ± 0.0 b | 0.3 ± 0.0 a | 0.3 ± 0.0 a | 0.3 ± 0.0 a |

| peonidin-3-AG | 1.5 ± 0.0 a | 1.8 ± 0.0 b | 1.9 ± 0.0 c | 1.5 ± 0.0 a | 2.0 ± 0.1 d |

| cyanidin-3-AG | 0.2 ± 0.0 | 0.2 ± 0.0 | 0.2 ± 0.0 | 0.2 ± 0.0 | 0.2 ± 0.0 |

| malvidin-3-CG | 28.7 ± 2.4 a | 38.5 ± 5.6 b | 41.5 ± 1.2 b | 34.6 ± 7.9 ab | 37.3 ± 7.6 ab |

| petunidin-3-CG | 3.9 ± 0.2 a | 5.8 ± 0.0 c | 4.4 ± 0.2 b | 3.7 ± 0.2 a | 4.2 ± 0.1 b |

| delphinidin-3-CG | 1.3 ± 0.1 b | 1.8 ± 0.0 c | 1.2 ± 0.0 b | 1.0 ± 0.1 a | 1.0 ± 0.0 a |

| peonidin-3-CG | 2.5 ± 0.3 | 3.0 ± 0.4 | 2.8 ± 0.1 | 2.0 ± 0.2 | 2.8 ± 0.0 |

| cyanidin-3-CG | 1.1 ± 0.0 c | 1.2 ± 0.0 d | 1.0 ± 0.0 c | 0.7 ± 0.0 a | 0.9 ± 0.0 b |

| Total Anthocyanins (mg/L) | 251.1 ± 11.7 a | 345.0 ± 15.9 c | 347.6 ± 12.3 c | 319.1 ± 20.7 b | 355.5 ± 13.7 c |

| Wine | Site 1 | Site 2 | Site 3 | Site 4 | Site 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| procyanidin B3 | 3.5 ± 0.2 c | 2.4 ± 0.1 b | 2.3 ± 0.2 b | 2.7 ± 0.1 b | 2.0 ± 0.1 a |

| procyanidin B1 | 23.7 ± 0.0 e | 19 ± 0.2 d | 13.7 ± 0.3 c | 14.5 ± 0.1 b | 12.6 ± 0.2 a |

| procyanidin B4 | 8.5 ± 0.2 d | 6.3 ± 0.0 c | 6.9 ± 0.1 b | 9.5 ± 0.2 a | 7.1 ± 0.2 b |

| procyanidin B2 | 8.6 ± 0.1 d | 6.3 ± 0.0 c | 6.9 ± 0.1 b | 9.6 ± 0.1 a | 7.1 ± 0.1 b |

| dimer monogallate | 1.7 ± 0.1 c | 2.5 ± 0.1 a | 3.0 ± 0.1 b | 3.1 ± 0.2 b | 1.9 ± 0.0 c |

| procyanidin B 5.1 | 1.2 ± 0.1 b | 1.2 ± 0.1 b | 0.9 ± 0.0 a | 0.8 ± 0.1 a | 0.8 ± 0.0 a |

| dimer digallate | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 |

| procyanidin B 6.6 | 3.0 ± 0.2 c | 3.6 ± 0.1 b | 4.2 ± 0.2 a | 4.7 ± 0.1 a | 4.2 ± 0.0 a |

| gallic acid | 22.1 ± 0.3 d | 16 ± 0.6 c | 14.6 ± 0.5 a | 15.3 ± 0.5 cb | 13.8 ± 0.2 a |

| catechin | 10.7 ± 0.2 e | 7.7 ± 0.1 d | 5.0 ± 0.1 c | 5.4 ± 0.1 b | 4.7 ± 0.1 a |

| epicatechin | 3.2 ± 0.1 b | 1.8 ± 0.1 a | 2.2 ± 0.0 a | 3.1 ± 0.0 b | 2.6 ± 0.0 a |

| epicatechin gallate | 0.1 ± 0.1 b | 0.1 ± 0.0 b | 0.1 ± 0.0 b | 0.1 ± 0.0 b | 0.0 ± 0.0 a |

| trimer C 0.6 | 7.4 ± 0.3 b | 6.6 ± 0.3 b | 5.7 ± 0.1 a | 5.5 ± 0.5 a | 5.0 ± 0.2 a |

| trimer C 2.4 | 9.8 ± 0.1 e | 6.9 ± 0.0 d | 4.8 ± 0.2 c | 5.5 ± 0.1 b | 4.2 ± 0.1 a |

| trimer C1 | 6.4 ± 0.2 b | 4.1 ± 0.2 a | 4.5 ± 0.2 a | 6.6 ± 0.2 b | 4.4 ± 0.3 a |

| TOTAL | 109.9 ± 1.0 c | 84 ± 0.7 b | 74.9 ± 1.0 a | 86.2 ± 0.9 b | 70.3 ± 0.5 a |

| Table Calculation Equations | ||

|---|---|---|

| Description | Unit | Calculation |

| Activity factor (physical activity level, PAL) (World Health Organization) | No | Light level activity factor: 1.55 (men) and 1.56 (women) Moderate level activity factor: 1.78 (men) and 1.64 (women) Intense level activity factor: 2.10 (men) and 1.82 (women) |

| Daily Energy Needs, REE (Harris–Benedict Equation) | kcal | Women: REE = 655.1 + 9.56 × weight (kg) + 1.85 × height (cm) − 4.68 × age (years) Men: REE = 66.5 + 13.75 × weight (kg) + 5.0 × height (cm) − 6.78 × age (years) +20% light; +30% moderate and 50–75% intense activity +10% Food-Induced Thermogenesis |

| Alcohol Energy | kcal | mL wine/day·(%alc. vol/100) × alcohol density × 7 Kcal/g Ethanol 7 kcal/g alcohol (Atwater Factor) |

| % Energy due to alcohol consumption | % | % = Alcohol energy/Daily Energy Needs |

| Healthy wine (intake of wine volume recommended) | mL/day | V (mL wine) = (g healthy alcohol/ % DA × 0.789) |

| Blood alcohol level (BAL) | g/day | BAL = (g healthy alcohol/kg) × (60 L/100 kg) |

| Men | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wine | Site 1 | Site 2 | Site 3 | Site 4 | Site 5 | ||||||||||

| Healthy alcohol serving (g/day) | 30 | 35 | 40 | 30 | 35 | 40 | 30 | 35 | 40 | 30 | 35 | 40 | 30 | 35 | 40 |

| Alcohol Energy (Kcal) | 210 | 245 | 280 | 210 | 245 | 280 | 210 | 245 | 280 | 210 | 245 | 280 | 210 | 245 | 280 |

| Healthy wine (mL/day) | 233 | 272 | 311 | 247 | 288 | 329 | 253 | 296 | 338 | 259 | 302 | 345 | 244 | 284 | 325 |

| % alc. Vol | 16.1 | 15.2 | 14.8 | 14.5 | 15.4 | ||||||||||

| Blood alcohol levels/day | 0.23 | 0.27 | 0.31 | 0.23 | 0.27 | 0.31 | 0.23 | 0.27 | 0.31 | 0.23 | 0.27 | 0.31 | 0.23 | 0.27 | 0.31 |

| % Energy due to alcohol consumption | 8.9 | 10.4 | 11.8 | 8.9 | 10.4 | 11.8 | 8.9 | 10.4 | 11.8 | 8.9 | 10.4 | 11.8 | 8.9 | 10.4 | 11.8 |

| Women | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wine | Site 1 | Site 2 | Site 3 | Site 4 | Site 5 | ||||||||||

| Healthy alcohol serving (g/day) | 10 | 15 | 20 | 10 | 15 | 20 | 10 | 15 | 20 | 10 | 15 | 20 | 10 | 15 | 20 |

| Alcohol Energy (Kcal) | 70 | 105 | 140 | 70 | 105 | 140 | 70 | 105 | 140 | 70 | 105 | 140 | 70 | 105 | 140 |

| Healthy wine (mL/day) | 78 | 117 | 156 | 82 | 123 | 164 | 84 | 127 | 169 | 86 | 129 | 172 | 81 | 122 | 162 |

| % alc. Vol | 16.1 | 15.2 | 14.8 | 14.5 | 15.4 | ||||||||||

| Blood alcohol levels/day | 0.09 | 0.13 | 0.18 | 0.09 | 0.13 | 0.18 | 0.09 | 0.13 | 0.18 | 0.09 | 0.13 | 0.18 | 0.09 | 0.13 | 0.18 |

| % Energy due to alcohol consumption | 3.4 | 5.1 | 6.7 | 3.4 | 5.1 | 6.7 | 3.4 | 5.1 | 6.7 | 3.4 | 5.1 | 6.7 | 3.4 | 5.1 | 6.7 |

| (a) | |||||||||

| Total ANT. (mg/L) | ANT. Intake (mg/day) | % BIO. ANT. | ANT. Intake (%) | ANT. Serum Intake (mg/day) | Serum Intake | ||||

| <1 | 1 < x < 2 | >2 | |||||||

| Men | Site 1 | 251.1 | 58.6 | 3.9 | 29.3 | 2.29 | x | ||

| 68.3 | 34.1 | 2.66 | x | ||||||

| 78.1 | 39.0 | 3.05 | x | ||||||

| Site 2 | 345 | 85.2 | 42.6 | 3.32 | x | ||||

| 99.4 | 49.7 | 3.88 | x | ||||||

| 113.5 | 56.8 | 4.43 | x | ||||||

| E (early ripeness) | 298.1 | 71.9 | 36.0 | 2.81 | x | ||||

| 83.8 | 41.9 | 3.27 | x | ||||||

| 95.8 | 47.9 | 3.74 | x | ||||||

| Site 3 | 347.6 | 87.9 | 44.0 | 3.43 | x | ||||

| 102.9 | 51.4 | 4.01 | x | ||||||

| 117.5 | 58.7 | 4.58 | x | ||||||

| Site 4 | 319.1 | 82.6 | 41.3 | 3.22 | x | ||||

| 96.4 | 48.2 | 3.76 | x | ||||||

| 110.1 | 55.0 | 4.29 | x | ||||||

| Site 5 | 355.5 | 86.7 | 43.4 | 3.38 | x | ||||

| 101.0 | 50.5 | 3.94 | x | ||||||

| 115.5 | 57.8 | 4.51 | x | ||||||

| L (late ripeness) | 340.7 | 85.8 | 42.9 | 3.35 | x | ||||

| 100.1 | 50.0 | 3.90 | x | ||||||

| 114.4 | 57.2 | 4.46 | x | ||||||

| (b) | |||||||||

| TOT. PRO (mg/L) | PRO. Intake (mg/day) | % BIO. PRO. | PRO. Intake (%) | PRO. Serum Intake (mg/day) | Serum Intake | ||||

| <1 | 1 < x < 2 | >2 | |||||||

| Men | Site 1 | 109.9 | 25.7 | 7.2 | 12.8 | 1.85 | x | ||

| 29.9 | 14.9 | 2.15 | x | ||||||

| 34.2 | 17.1 | 2.46 | x | ||||||

| Site 2 | 84.4 | 20.8 | 10.4 | 1.50 | x | ||||

| 24.3 | 12.2 | 1.75 | x | ||||||

| 27.8 | 13.9 | 2.00 | x | ||||||

| E (early ripeness) | 97.2 | 23.3 | 11.6 | 1.67 | x | ||||

| 27.1 | 13.6 | 1.95 | x | ||||||

| 31.0 | 15.5 | 2.23 | x | ||||||

| Site 3 | 74.9 | 18.9 | 9.5 | 1.36 | x | ||||

| 22.2 | 11.1 | 1.60 | x | ||||||

| 25.3 | 12.7 | 1.82 | x | ||||||

| Site 4 | 86.2 | 22.3 | 11.2 | 1.61 | x | ||||

| 26.0 | 13.0 | 1.87 | x | ||||||

| 29.7 | 14.9 | 2.14 | x | ||||||

| Site 5 | 70.3 | 17.2 | 8.6 | 1.24 | x | ||||

| 20.0 | 10.0 | 1.44 | x | ||||||

| 22.8 | 11.4 | 1.65 | x | ||||||

| L (late ripeness) | 77.1 | 19.5 | 9.7 | 1.40 | x | ||||

| 22.7 | 11.4 | 1.64 | x | ||||||

| 26.0 | 13.0 | 1.87 | x | ||||||

| (c) | |||||||||

| TOT. ANT. (mg/L) | ANT. Intake (mg/day) | % BIO. ANT | ANT. Intake (%) | ANT. Serum Intake (mg/day) | Serum Intake | ||||

| <1 | 1 < x < 2 | >2 | |||||||

| Women | Site 1 | 251.1 | 19.6 | 3.9 | 9.8 | 0.76 | x | ||

| 29.4 | 14.7 | 1.15 | x | ||||||

| 39.2 | 19.6 | 1.53 | x | ||||||

| Site 2 | 345 | 28.3 | 14.1 | 1.10 | x | ||||

| 42.4 | 21.2 | 1.65 | x | ||||||

| 56.6 | 28.3 | 2.21 | x | ||||||

| E (early ripeness) | 298.1 | 23.9 | 12.0 | 0.93 | x | ||||

| 35.9 | 18.0 | 1.40 | x | ||||||

| 47.9 | 23.9 | 1.87 | x | ||||||

| Site 3 | 347.6 | 29.2 | 14.6 | 1.14 | x | ||||

| 44.1 | 22.1 | 1.72 | x | ||||||

| 58.7 | 29.4 | 2.29 | x | ||||||

| Site 4 | 319.1 | 27.4 | 13.7 | 1.07 | x | ||||

| 41.2 | 20.6 | 1.61 | x | ||||||

| 54.9 | 27.4 | 2.14 | x | ||||||

| Site 5 | 355.5 | 28.8 | 14.4 | 1.12 | x | ||||

| 43.4 | 21.7 | 1.69 | x | ||||||

| 57.6 | 28.8 | 2.25 | x | ||||||

| L (late ripeness) | 340.7 | 28.5 | 14.2 | 1.11 | x | ||||

| 42.9 | 21.4 | 1.67 | x | ||||||

| 57.1 | 28.5 | 2.23 | x | ||||||

| (d) | |||||||||

| TOT. PRO. (mg/L) | PRO. Intake (mg/day) | % BIO. PRO. | PRO Intake (%) | PRO Serum Intake (mg/day) | Serum PRO. EXP. Intake | ||||

| <1 | 1 < x < 2 | >2 | |||||||

| Women | Site 1 | 109.9 | 8.6 | 7.2 | 4.3 | 0.62 | x | ||

| 12.9 | 6.4 | 0.93 | x | ||||||

| 17.1 | 8.6 | 1.23 | x | ||||||

| Site 2 | 84.4 | 6.9 | 3.5 | 0.50 | x | ||||

| 10.4 | 5.2 | 0.75 | x | ||||||

| 13.8 | 6.9 | 1.00 | x | ||||||

| E (early ripeness) | 97.2 | 7.7 | 3.9 | 0.56 | x | ||||

| 11.6 | 5.8 | 0.84 | x | ||||||

| 15.5 | 7.7 | 1.12 | x | ||||||

| Site 3 | 74.9 | 6.3 | 3.1 | 0.45 | x | ||||

| 9.5 | 4.8 | 0.68 | x | ||||||

| 12.7 | 6.3 | 0.91 | x | ||||||

| Site 4 | 86.2 | 7.4 | 3.7 | 0.53 | x | ||||

| 11.1 | 5.6 | 0.80 | x | ||||||

| 14.8 | 7.4 | 1.07 | x | ||||||

| Site 5 | 70.3 | 5.7 | 2.8 | 0.41 | x | ||||

| 8.6 | 4.3 | 0.62 | x | ||||||

| 11.4 | 5.7 | 0.82 | x | ||||||

| L (late ripeness) | 77.1 | 6.5 | 3.2 | 0.47 | x | ||||

| 9.7 | 4.9 | 0.70 | x | ||||||

| 13.0 | 6.5 | 0.93 | x | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sánchez-Ortiz, A.; Mateo-Sanz, J.M.; Mateos-Fernández, M.A.; Figueras, M.L. New Labeling Rules for Wine: Wine Alcohol-Derived Calories and Polyphenol Consumption on Health. Foods 2024, 13, 295. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods13020295

Sánchez-Ortiz A, Mateo-Sanz JM, Mateos-Fernández MA, Figueras ML. New Labeling Rules for Wine: Wine Alcohol-Derived Calories and Polyphenol Consumption on Health. Foods. 2024; 13(2):295. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods13020295

Chicago/Turabian StyleSánchez-Ortiz, Antoni, Josep Maria Mateo-Sanz, Maria Assumpta Mateos-Fernández, and Miriam Lampreave Figueras. 2024. "New Labeling Rules for Wine: Wine Alcohol-Derived Calories and Polyphenol Consumption on Health" Foods 13, no. 2: 295. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods13020295

APA StyleSánchez-Ortiz, A., Mateo-Sanz, J. M., Mateos-Fernández, M. A., & Figueras, M. L. (2024). New Labeling Rules for Wine: Wine Alcohol-Derived Calories and Polyphenol Consumption on Health. Foods, 13(2), 295. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods13020295