Effect of Rootstock on the Volatile Profile of Mandarins

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material

2.2. Preparation of Juice

2.3. Volatile Composition

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Carvalho, E.V.; Cifuentes-Arenas, J.C.; Raiol-Junior, L.L.; Stuchi, E.S.; Girardi, E.A.; Lopes, S.A. Modeling seasonal flushing and shoot growth on different citrus scion-rootstock combinations. Sci. Hortic. 2021, 288, 110358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, Z.; Iftikhar, Y.; Mubeen, M.; Saleem, M.Z.; Naseer, M.U.; Luqman, M.; Anwar, R.; Khadija, F.; Abbas, A. Application of micronutrients enhances the quality of kinnow mandarin infected by citrus greening disease (Huanglongbing). Sarhad J. Agric. 2022, 38, 360–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAOSTAT. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Database. Available online: https://www.fao.org/faostat/es/#data/QCL (accessed on 22 February 2022).

- Liu, Y.; Heying, E.; Tanumihardjo, S.A. History, global distribution, and nutritional importance of citrus fruits. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2012, 11, 530–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.-H.; Pizzo, N.; Abutineh, M.; Jin, X.-L.; Naylon, S.; Meredith, T.L.; West, L.; Harlin, J.M. Molecular and cellular analysis of orange plants infected with Huanglongbing (citrus greening disease). Plant Growth Regul. 2020, 92, 333–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hijaz, F.; Gmitter, F.G., Jr.; Bai, J.; Baldwin, E.; Biotteau, A.; Leclair, C.; McCollum, T.G.; Plotto, A. Effect of fruit maturity on volatiles and sensory descriptors of four mandarin hybrids. J. Food Sci. 2020, 85, 1548–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FAO. Perspectivas a Plazo Medio de los Productos Básicos Agrícolas. Proyecciones al año 2010; Organización de las Naciones Unidas para la Agricultura y la Alimentación: Rome, Italy, 2004.

- Yu, Y.; Bai, J.; Chen, C.; Plotto, A.; Baldwin, E.A.; Gmitter, F.G. Comparative analysis of juice volatiles in selected mandarins, mandarin relatives and other citrus genotypes. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2018, 98, 1124–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales-Alfaro, J.; Bermejo, A.; Navarro, P.; Quiñones, A.; Salvador, A. Effect of rootstock on citrus fruit quality: A review. Food Rev. Int. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sdiri, S.; Salvador, A.; Farhat, I.; Navarro, P.; Besada, C. Influence of postharvest handling on antioxidant compounds of citrus fruits. In Citrus: Molecular Phylogeny, Antioxidant Properties and Medicinal Uses; Nova Science Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 83–93. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Ting, J.L.H.; Peng, Y.; Tangjaidee, P.; Zhu, Y.; Li, Q.; Shan, Y.; Quek, S.Y. Comparing three types of mandarin powders prepared via microfluidic-jet spray drying: Physical properties, phenolic retention and volatile profiling. Foods 2021, 10, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Li, G.; Wu, H.; Liang, G.; Wang, H. Flavor deterioration of mandarin juice during storage by mdgc-ms/o and gc-ms/pfpd. LWT 2022, 159, 113132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, S.; Niu, L.; Suh, J.H.; Hung, W.-L.; Wang, Y. Comprehensive metabolomics analysis of mandarins (Citrus reticulata) as a tool for variety, rootstock, and grove discrimination. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2018, 66, 10317–10326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castle, W.S. Rootstock as a fruit quality factor in citrus and deciduous tree crops. N. Z. J. Crop Hortic. Sci. 1995, 23, 383–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamin, G.; Tietel, Z.; Porat, R. Effects of rootstock/scion combinations on the flavor of citrus fruit. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2013, 61, 11286–11294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aguilar-Hernández, M.G.; Sánchez-Bravo, P.; Hernández, F.; Carbonell-Barrachina, Á.A.; Pastor-Pérez, J.J.; Legua, P. Determination of the volatile profile of lemon peel oils as affected by rootstock. Foods 2020, 9, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legua, P.; Forner, J.B.; Hernández, F.; Forner-Giner, M.A. Total phenolics, organic acids, sugars and antioxidant activity of mandarin (Citrus clementina Hort. ex Tan.): Variation from rootstock. Sci. Hortic. 2014, 174, 60–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malochleb, M. Sustainability: How food companies are turning over a new leaf. Food Technol. Mag. 2018, 72, 32–43. [Google Scholar]

- Cano-Lamadrid, M.; Lipan, L.; Hernández, F.; Martínez, J.J.; Legua, P.; Carbonell-Barrachina, Á.A.; Melgarejo, P. Quality parameters, volatile composition, and sensory profiles of highly endangered Spanish citrus fruits. J. Food Qual. 2018, 2018, 3475461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palma, C.E.; Cruz, P.S.; Cruz, D.T.C.; Bugayong, A.M.S.; Castillo, A.L. Chemical composition and cytotoxicity of Philippine calamansi essential oil. Ind. Crops Prod. 2019, 128, 108–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-López, A.J.; Saura, D.; Lorente, J.; Carbonell-Barrachina, Á.A. Limonene, linalool, α-terpineol, and terpinen-4-ol as quality control parameters in mandarin juice processing. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2006, 222, 281–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, J.; Baldwin, E.; Hearn, J.; Driggers, R.; Stover, E. Volatile and nonvolatile flavor chemical evaluation of USDA orange–mandarin hybrids for comparison to sweet orange and mandarin fruit. J. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 2016, 141, 339–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plotto, A.; Margaría, C.A.; Goodner, K.L.; Baldwin, E.A. Odour and flavour thresholds for key aroma components in an orange juice matrix: Esters and miscellaneous compounds. Flavour Fragr. J. 2008, 23, 398–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obenland, D.; Collin, S.; Sievert, J.; Arpaia, M.L. Mandarin flavor and aroma volatile composition are strongly influenced by holding temperature. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2013, 82, 6–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TGSC. The Good Scents Company Database. Available online: http://www.thegoodscentscompany.com/index.html (accessed on 24 February 2022).

- Dharmawan, J.; Kasapis, S.; Curran, P.; Johnson, J.R. Characterization of volatile compounds in selected citrus fruits from Asia. Part i: Freshly-squeezed juice. Flavour Fragr. J. 2007, 22, 228–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tietel, Z.; Plotto, A.; Fallik, E.; Lewinsohn, E.; Porat, R. Taste and aroma of fresh and stored mandarins. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2011, 91, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaw, P.E. Volatile Compounds in Foods and Beverages; Fruits, I.I., Maarse, H., Eds.; Marcel Dekker: New York, NY, USA, 1991; pp. 305–327. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-López, A.J.; Carbonell-Barrachina, Á.A. Volatile odour components and sensory quality of fresh and processed mandarin juices. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2006, 86, 2404–2411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saini, M.K.; Capalash, N.; Kaur, C.; Singh, S.P. Comprehensive metabolic profiling to decipher the influence of rootstocks on fruit juice metabolome of Kinnow (C. nobilis × C. deliciosa). Sci. Hortic. 2019, 257, 108673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raddatz-Mota, D.; Franco-Mora, O.; Mendoza-Espinoza, J.A.; Rodríguez-Verástegui, L.L.; Díaz de León-Sánchez, F.; Rivera-Cabrera, F. Effect of different rootstocks on Persian lime (Citrus latifolia T.) postharvest quality. Sci. Hortic. 2019, 257, 108716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llosa, M.J. Evaluation of the Behavior of New Citrus Patterns against Ferric Chlorosis. Ph.D. Thesis, Polythecnic University of Valencia, Valencia, Spain, 2009. [Google Scholar]

| Rootstocks | Botanical Name | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Carrizo citrange | Citrus sinensis (L.) Osb. × Poncirus trifoliata (L.) Raf. |

| 2 | Swingle citrumelo CPB 4475 | C. paradisi × P. trifoliata |

| 3 | Macrophylla | C. macrophylla Wester |

| 4 | Volkameriana | C. volkameriana Ten. and Pasq. |

| 5 | Forner-Alcaide 5 | C. reshni × P. trifoliata |

| 6 | Forner-Alcaide V17 | C. volkameriana × P. trifoliata |

| 7 | C-35 | C. sinensis × P. trifoliata |

| 8 | Forner-Alcaide 418 | (C. sinensis x P. trifoliata) × C. deliciosa Ten. |

| 9 | Forner-Alcaide 517 | C. nobilis Lour. × P. trifoliata |

| Compound | RT | KI (Exp) | KI (Lit) | Descriptors | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| V1 | Ethanol | 5.14 | 498 | 482 | Ethanol |

| V2 | Ethyl acetate | 5.63 | 613 | 608 | Pleasant, fruity |

| V3 | Methyl butyrate | 6.35 | 694 | 719 | Fruity, sweet |

| V4 | Ethyl butyrate | 7.28 | 797 | 799 | Fruity, sweet |

| V5 | Hexanal | 7.36 | 803 | 801 | Green, grassy |

| V6 | Butyl acetate | 7.48 | 809 | 813 | Fruity |

| V7 | Ethyl-2-butenoate | 8.11 | 841 | 834 | -- |

| V8 | Heptanal | 9.42 | 906 | 902 | Oily, fatty |

| V9 | Methyl hexanoate | 9.89 | 922 | 924 | Fruity |

| V10 | α-Thujene | 10.18 | 933 | 933 | Wood, green, herb |

| V11 | α-Pinene | 10.51 | 944 | 940 | Pine, turpentine |

| V12 | Benzaldehyde | 11.54 | 981 | 970 | Almond, cherry |

| V13 | Sabinene | 11.68 | 986 | 978 | Pepper, turpentine, wood |

| V14 | Myrcene | 11.97 | 996 | 995 | Musty, wet soil |

| V15 | Ethyl hexanoate | 12.17 | 1002 | 1000 | Fruity, sweet, green |

| V16 | Octanal | 12.50 | 1011 | 1006 | Citrus, green, herbal |

| V17 | Hexyl acetate | 12.63 | 1014 | 1011 | Fruity, green, sweet |

| V18 | α-Phellandrene | 12.83 | 1019 | 1025 | Citrus, herbal, green, woody |

| V19 | d-3-Carene | 12.95 | 1022 | 1013 | Citrus, herbal, woody |

| V20 | α-Terpinene | 13.23 | 1029 | 1023 | Lemony, citrus |

| V21 | p-Cymene | 13.55 | 1037 | 1027 | Woody, spicy |

| V22 | Limonene | 13.92 | 1047 | 1039 | Citrus, fresh |

| V23 | Benzyl alcohol | 14.01 | 1049 | 1040 | Floral, fruity, sweet |

| V24 | (Z)-β-Ocimene | 14.10 | 1051 | 1050 | Herbal, sweet |

| V25 | (E)-β-Ocimene | 14.53 | 1062 | 1053 | Herbal, sweet |

| V26 | γ-Terpinene | 14.76 | 1068 | 1066 | Lemony, citrus |

| V27 | 1-Octanol | 15.08 | 1076 | 1072 | Waxy, green, citrus, floral |

| V28 | Sabinene hydrate | 15.70 | 1092 | 1096 | Herbal, minty, green |

| V29 | α-Terpinolene | 15.89 | 1097 | 1092 | Citrus, pine |

| V30 | Linalool | 16.28 | 1106 | 1101 | Floral, green, citrus, woody |

| V31 | Nonanal | 16.48 | 1111 | 1102 | Pine, floral, citrus |

| V32 | Methyl octanoate | 17.12 | 1125 | 1127 | Waxy, green, orange, herbal, sweet |

| V33 | Ethyl-3-hydroxy-hexanoate | 17.53 | 1134 | 1130 | Fruity, woody, spicy, green |

| V34 | cis-Limonene oxide | 17.69 | 1138 | 1132 | Fresh citrus |

| V35 | trans-Limonene oxide | 17.97 | 1144 | 1138 | Fresh citrus |

| V36 | Menthol | 18.72 | 1161 | 1160 | Minty |

| V37 | Terpinen-4-ol | 20.25 | 1195 | 1192 | Peppery, woody, sweet, musty |

| V38 | Ethyl octanoate | 20.35 | 1197 | 1200 | -- |

| V39 | α-Terpineol | 20.86 | 1208 | 1192 | Oil, anise, mint |

| V40 | Decanal | 20.98 | 1211 | 1216 | Beefy, musty |

| V41 | Carveol | 21.73 | 1227 | 1220 | Minty |

| V42 | Chavicol | 22.04 | 1234 | 1251 | Herbal |

| V43 | Neral | 22.65 | 1247 | 1235 | Lemon |

| V44 | Linalyl acetate | 22.88 | 1251 | 1250 | Herbal, green, citrus, woody, floral |

| V45 | Carvone | 23.18 | 1258 | 1254 | Spearmint, caraway |

| V46 | Geranial | 23.97 | 1275 | 1277 | Lemon, mint, floral |

| V47 | 1-Decanol | 24.23 | 1280 | 1274 | Fatty, waxy, floral, citrus |

| V48 | Perilla aldehyde | 24.74 | 1291 | 1271 | -- |

| V49 | Ethyl nonanoate | 24.95 | 1296 | 1296 | Fruity, rose, waxy, rum, wine |

| V50 | Bornyl acetate | 25.13 | 1300 | 1285 | Woody, balsamic, pine, herbal |

| V51 | Undecanal | 25.70 | 1312 | 1307 | Floral, citrus, green |

| V52 | cis-Carvyl acetate | 26.60 | 1332 | 1334 | Minty, green, herbal |

| V53 | trans-Carvyl acetate | 26.91 | 1338 | 1341 | Minty, green, herbal |

| V54 | Citronellyl acetate | 27.48 | 1351 | 1354 | Floral, green, fuity, citrus, woody |

| V55 | Terpenyl acetate | 27.68 | 1355 | 1351 | Herbal, citrus |

| V56 | Neryl acetate | 28.83 | 1380 | 1368 | Fruity, floral, citrus |

| V57 | α-Copaene | 29.27 | 1390 | 1377 | Woody, spicy, honey |

| V58 | Ethyl decanoate | 29.53 | 1395 | 1397 | Waxy, fruity |

| V59 | cis-β-Elemene | 29.77 | 1400 | 1381 | Herbal |

| V60 | Decyl acetate | 30.16 | 1409 | 1408 | Waxy, soapy, citrus |

| V61 | Dodecanal | 30.36 | 1414 | 1409 | Citrus, green, floral |

| V62 | Limonen-10-yl-acetate | 30.51 | 1417 | na | Fruity |

| V63 | β-Farnesene | 30.99 | 1428 | 1431 | Woody, citrus, herbal |

| V64 | Caryophyllene | 31.43 | 1437 | 1430 | Spicy, Woody, clove |

| V65 | Germacrene-D | 31.80 | 1446 | 1449 | Woody, spicy |

| V66 | Alloaromadendrene | 32.57 | 1463 | 1462 | Woody |

| V67 | Humulene | 33.03 | 1473 | 1461 | Woody, spicy-clove |

| V68 | Valencene | 34.61 | 1509 | 1496 | Citrus, fruity, woody |

| V69 | d-Selinene | 34.81 | 1514 | 1496 | -- |

| V70 | Cadinene | 35.53 | 1531 | 1516 | Fresh woody |

| V71 | γ-Muurolene | 35.88 | 1539 | 1530 | Woody, herbal, spicy |

| Carrizo Citrange | Swingle Citrum. | Macrophylla | Volkameriana | Forner-Alcaide 5 | Forner-Alcaide V17 | C-35 | Forner-Alcaide 418 | Forner-Alcaide 517 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compound | ANOVA Ϯ | µg L−1 | ||||||||

| Ethanol | *** | 116 bc‡ | 94.3 cd | 67.5 de | 76.8 de | 88.9 cd | 121 bc | 46.9 e | 146 b | 200 a |

| Ethyl acetate | *** | 1.7 c | 2.7 b | 1.3 c | 2.5 b | 2.9 b | 3.7 a | 1.4 c | 2.5 b | 4.0 a |

| Methyl butyrate | *** | 3.1 e | 4.8 cd | 2.9 e | 0.0 f | 5.1 c | 8.0 b | 10.2 a | 3.5 de | 4.3 cde |

| Ethyl butyrate | *** | 72.1 b | 105 a | 64.2 b | 59.1 b | 105 a | 114 a | 30.3 c | 108 a | 106 a |

| Hexanal | *** | 10.6 b | 7.2 c | 7.3 c | 14.3 a | 7.2 c | 5.7 cd | 2.7 e | 4.9 de | 5.7 cd |

| Butyl acetate | *** | 21.1 cd | 26.1 bc | 13.2 e | 16.9 de | 25.6 bc | 13.9 e | 35.1 a | 31.2 ab | 31.6 ab |

| Ethyl-2-butenoate | *** | 3.3 cde | 3.3 bcd | 2.4 de | 2.2 e | 4.4 b | 3.7 bc | 1.0 f | 4.3 bc | 7.1 a |

| Heptanal | *** | 1.2 bc | 0.9 cd | 1.3 b | 2.3 a | 0.4 e | 0.9 cd | 0.6 de | 1.4 b | 1.4 b |

| Methyl hexanoate | *** | 1.2 cd | 2.8 b | 1.7 cd | 1.9 c | 2.6 b | 3.9 a | 1.2 d | 1.5 cd | 1.9 c |

| α-Thujene | *** | 2.2 a | 0.3 d | 0.3 d | 0.4 d | 0.7 c | 0.4 d | 0.3 d | 0.8 c | 1.2 b |

| α-Pinene | *** | 66.1 a | 22.7 c | 13.6 d | 14.4 d | 38.4 b | 22.5 c | 15.0 d | 36.9 b | 58.4 a |

| Benzaldehyde | *** | 1.3 cd | 4.8 a | 1.0 cde | 0.7 de | 0.5 e | 1.1 cd | 1.5 c | 1.1 cd | 2.9 b |

| Sabinene | *** | 24.4 a | 3.9 cd | 2.8 cd | 2.5 cd | 4.2 c | 2.5 cd | 1.3 d | 4.0 c | 11.8 b |

| Myrcene | *** | 521 a | 228 cd | 131 e | 137 de | 361 b | 241 c | 170 cde | 369 b | 485 a |

| Ethyl hexanoate | *** | 15.1 c | 22.8 ab | 8.9 d | 14.4 c | 19.0 bc | 25.7 a | 5.7 d | 18.1 bc | 17.6 c |

| Octanal | *** | 149 a | 30.2 cd | 54.9 b | 5.6 e | 52.6 bc | 21.7 de | 53.3 bc | 48.8 bc | 171 a |

| Hexyl acetate | *** | 12.7 ab | 4.9 cd | 3.2 d | 6.4 c | 14.8 a | 6.3 c | 3.3 d | 3.4 d | 11.2 b |

| α-Phellandrene | *** | 10.3 a | 4.1 c | 2.4 de | 2.2 e | 8.1 b | 4.0 cd | 3.9 cd | 4.2 c | 7.7 b |

| d-3-Carene | *** | 32.3 a | 10.7 de | 6.2 e | 6.2 e | 35.9 a | 8.2 de | 12.7 cd | 18.0 c | 25.0 b |

| α-Terpinene | *** | 14.7 a | 7.0 c | 3.6 e | 3.3 e | 9.9 b | 4.6 cd | 4.7 cd | 10.0 b | 10.6 b |

| p-Cymene | *** | 2.1 b | 1.7 b | 1.9 b | 5.0 a | 1.1 c | 1.6 b | 2.1 b | 2.0 b | 1.1 c |

| Limonene | *** | 12,278 ab | 7004 c | 4021 e | 3879 e | 10,124 b | 6353 cd | 5348 cd | 10,194 b | 12,785 a |

| Benzyl alcohol | *** | 69.0 a | 35.7 b | 17.4 cd | 20.1 cd | 11.0 d | 37.2 b | 26.0 bc | 67.5 a | 69.0 a |

| (Z)-β-Ocimene | *** | 34.1 a | 14.6 d | 7.2 ef | 5.6 f | 24.7 bc | 12.7 de | 10.5 def | 22.4 c | 28.4 ab |

| (E)-β-Ocimene | *** | 1.2 bc | 0.5 c | 0.2 d | 0.2 d | 1.6 b | 1.2 bc | 1.0 c | 1.5 b | 2.0 a |

| γ-Terpinene | *** | 43.7 a | 19.0 c | 11.6 d | 10.3 f | 33.6 b | 14.5 cd | 13.7 cd | 29.6 b | 30.0 b |

| 1-Octanol | *** | 59.0 a | 40.7 bc | 29.8 cd | 33.7 c | 29.0 cd | 39.6 bc | 44.1 b | 27.2 d | 63.3 a |

| Sabinene hydrate | *** | 2.2 a | 0.9 bc | 0.6 c | 0.5 c | 2.3 a | 1.0 bc | 1.5 b | 1.3 b | 2.2 a |

| α-Terpinolene | *** | 22.3 a | 8.6 c | 5.2 d | 3.8 e | 20.8 a | 7.8 cd | 8.5 c | 13.9 b | 15.8 b |

| Linalool | *** | 416 a | 196 c | 177 c | 235 bc | 197 c | 209 bc | 274 ab | 199 c | 323 a |

| Nonanal | *** | 47.3 a | 11.9 | 14.1 cd | 10.0 d | 17.9 c | 10.6 d | 11.5 cd | 12.3 cd | 38.1 b |

| Methyl octanoate | *** | 2.3 b | 1.7 bc | 1.2 c | 2.4 b | 4.0 a | 2.8 b | 1.1 c | 2.3 b | 2.4 b |

| Ethyl-3-hydroxy-hexanoate | *** | 8.7 bc | 10.1 ab | 6.6 c | 12.7 a | 12.7 a | 11.6 a | 2.8 d | 8.4 bc | 12.1 a |

| cis-Limonene oxide | *** | 3.4 a | 1.6 de | 2.0 cd | 1.4 de | 3.6 a | 3.2 ab | 1.0 e | 2.6 bc | 2.9 ab |

| trans-Limonene oxide | *** | 1.5 a | 0.8 b | 0.4 c | 0.7 b | 0.8 b | 0.5 bc | 0.5 bc | 0.8 b | 1.7 a |

| Menthol | *** | 0.8 c | 1.1 c | 1.2 c | 0.9 c | 1.6 b | 1.0 c | 1.4 bc | 1.2 c | 2.2 a |

| Terpinen-4-ol | *** | 132 a | 64.5 c | 105 b | 64.2 c | 76.4 c | 53.9 c | 56.c8 | 71.1 c | 101 b |

| Ethyl octanoate | *** | 14.1 b | 13.3 b | 8.4 cd | 11.3 bc | 13.2 b | 11.5 bc | 6.4 d | 18.5 a | 13.0 b |

| α-Terpineol | *** | 33.1 a | 21.4 d | 30.1 b | 24.9 bc | 23.3 bc | 21.8 cd | 29.0 b | 22.4 c | 31.9 ab |

| Decanal | *** | 308 a | 59.6 de | 104 c | 30.1 e | 123 c | 56.3 de | 55.1 de | 80.1 cd | 263 b |

| Carveol | *** | 6.1 a | 2.0 d | 2.1 d | 1.7 d | 3.1 bc | 2.0 d | 2.2 cd | 2.4 cd | 3.7 b |

| Chavicol | *** | 40.2 a | 28.6 b | 26.2 b | 32.7 ab | 32.5 ab | 25.7 b | 32.1 ab | 25.9 b | 32.8 ab |

| Neral | *** | 15.3 a | 3.0 de | 3.9 de | 3.6 de | 6.1 bc | 3.7 de | 2.9 e | 4.8 cd | 7.5 b |

| Linalyl acetate | *** | 8.6 a | 4.9 b | 5.1 b | 2.5 de | 2.4 de | 4.8 bc | 1.9 e | 2.3 e | 3.6 cd |

| Carvone | *** | 14.3 b | 9.8 cd | 12.9 bc | 33.8 a | 12.2 bc | 10.1 bcd | 10.2 bcd | 7.6 d | 11.1 bcd |

| Geranial | *** | 25.4 a | 4.9 c | 5.7 c | 4.7 c | 10.9 b | 4.4 c | 4.5 c | 6.0 c | 12.2 b |

| 1-Decanol | *** | 16.0 a | 9.3 c | 8.9 c | 7.9 c | 12.8 ab | 8.0 c | 12.2 bc | 8.9 c | 14.1 ab |

| Perilla aldehyde | *** | 22.3 a | 11.4 bc | 14.1 b | 10.1 cd | 12.9 bc | 12.4 bc | 10.1 cd | 7.6 d | 15.0 b |

| Ethyl nonanoate | *** | 4.2 c | 3.4 c | 3.0 c | 3.3 c | 2.8 c | 1.8 c | 11.1 b | 3.8 c | 33.2 a |

| Bornyl acetate | *** | 2.4 bc | 2.1 bc | 1.5 c | 1.4 c | 2.2 bc | 2.1 bc | 2.0 bc | 2.8 b | 4.2 a |

| Undecanal | *** | 8.6 a | 2.2 c | 2.6 c | 2.1 c | 5.1 b | 2.0 c | 1.9 c | 2.0 c | 6.0 b |

| cis-Carvyl acetate | *** | 10.2 a | 2.4 cd | 5.0 b | 3.5 c | 2.7 c | 6.4 b | 1.3 d | 1.2 d | 5.0 b |

| trans-Carvyl acetate | *** | 6.3 a | 5.5 a | 5.2 a | 1.9 cd | 3.1 bc | 5.9 a | 1.5 d | 1.8 cd | 3.8 b |

| Citronellyl acetate | *** | 7.6 a | 2.7 cd | 2.3 cd | 2.2 d | 4.2 b | 3.0 cd | 2.4 cd | 3.4 bc | 2.9 cd |

| Terpenyl acetate | *** | 40.1 a | 10.8 c | 10.7 c | 11.9 c | 21.6 b | 10.9 c | 12.4 c | 8.1 c | 21.6 b |

| Neryl acetate | *** | 39.5 a | 13.6 c | 9.8 d | 14.2 c | 25.0 b | 13.0 c | 12.8 c | 16.4 c | 16.0 c |

| α-Copaene | *** | 2.1 a | 0.6 c | 0.7 bc | 0.5 c | 2.0 a | 1.1 b | 0.5 c | 0.8 bc | 2.4 a |

| Ethyl decanoate | *** | 3.1 c | 3.5 bc | 1.6 e | 1.8 de | 4.5 b | 2.6 cd | 2.0 de | 7.0 a | 2.6 cd |

| cis-β-Elemene | *** | 9.1 a | 2.7 c | 2.6 c | 3.0 c | 5.5 b | 4.5 b | 2.6 c | 4.6 b | 5.7 b |

| Decyl acetate | *** | 7.9 a | 4.5 bc | 4.4 bc | 1.6 ef | 3.4 cd | 4.8 b | 1.5 de | 2.7 f | 3.3 cd |

| Dodecanal | *** | 13.2 a | 2.6 de | 3.4 de | 1.8 e | 6.2 c | 2.6 de | 2.3 de | 3.8 d | 10.0 b |

| Limonen-10-yl-acetate | *** | 33.5 a | 7.3 e | 10.0 de | 8.9 de | 19.7 b | 8.2 cd | 12.3 de | 6.8 e | 16.1 bc |

| β-Farnesene | *** | 17.5 b | 15.7 b | 17.9 b | 5.2 d | 10.7 c | 22.0 a | 6.3 d | 7.8 cd | 7.6 cd |

| Caryophyllene | *** | 8.8 a | 1.9 de | 2.3 de | 2.1 de | 5.3 c | 2.8 d | 1.2 e | 4.4 c | 7.4 b |

| Germacrene-D | *** | 2.0 b | 0.7 c | 0.6 c | 0.7 c | 1.6 bc | 1.0 c | 0.7 c | 0.8 c | 3.1 a |

| Alloaromadendrene | *** | 4.7 a | 1.1 ef | 0.8 ef | 2.1 cd | 4.0 ab | 2.4 c | 0.5 f | 1.5 de | 3.3 b |

| Humulene | *** | 2.0 a | 1.0 b | 1.0 b | 0.8 b | 1.9 a | 1.1 b | 1.1 b | 1.1 b | 2.0 a |

| Valencene | *** | 251 a | 47.8 e | 60.1 de | 93.4 cd | 200 b | 124 c | 21.1 f | 101 cd | 201 b |

| d-Selinene | *** | 25.8 a | 5.8 d | 6.6 d | 10.2 c | 20.3 b | 12.9 c | 2.5 e | 10.6 c | 19.6 b |

| Cadinene | *** | 5.0 a | 1.1 cd | 1.6 c | 1.6 c | 2.5 b | 1.6 c | 0.5 d | 1.1 cd | 4.3 a |

| γ-Muurolene | *** | 14.5 a | 2.7 e | 3.5 de | 5.7 cd | 11.6 b | 6.8 c | 1.2 e | 6.0 c | 11.5 b |

| TOTAL | *** | 15,225 a | 8309 bc | 5170 d | 4999 d | 11,968 ab | 7777 bc | 6473 cd | 11,861 ab | 15,446 a |

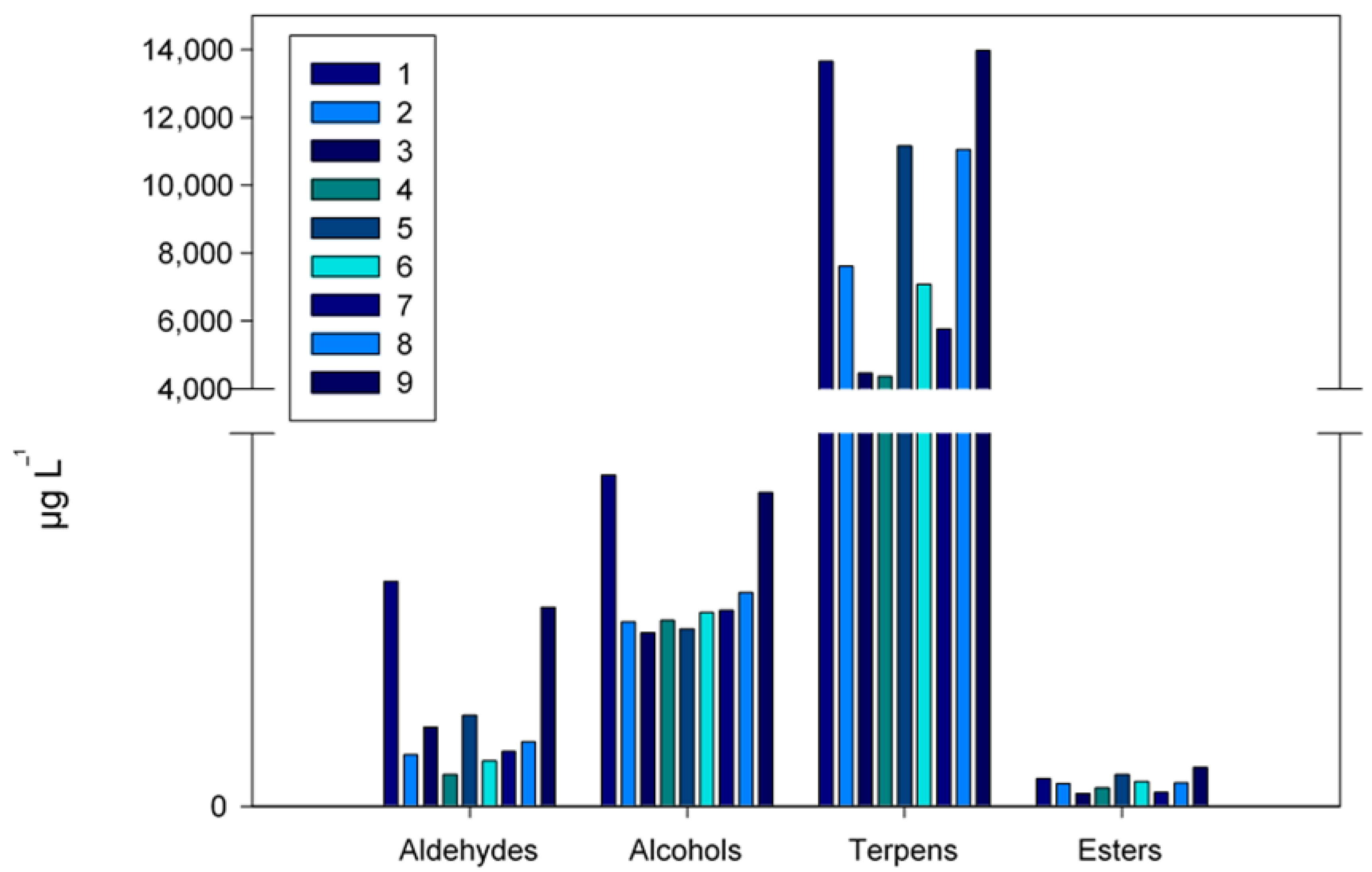

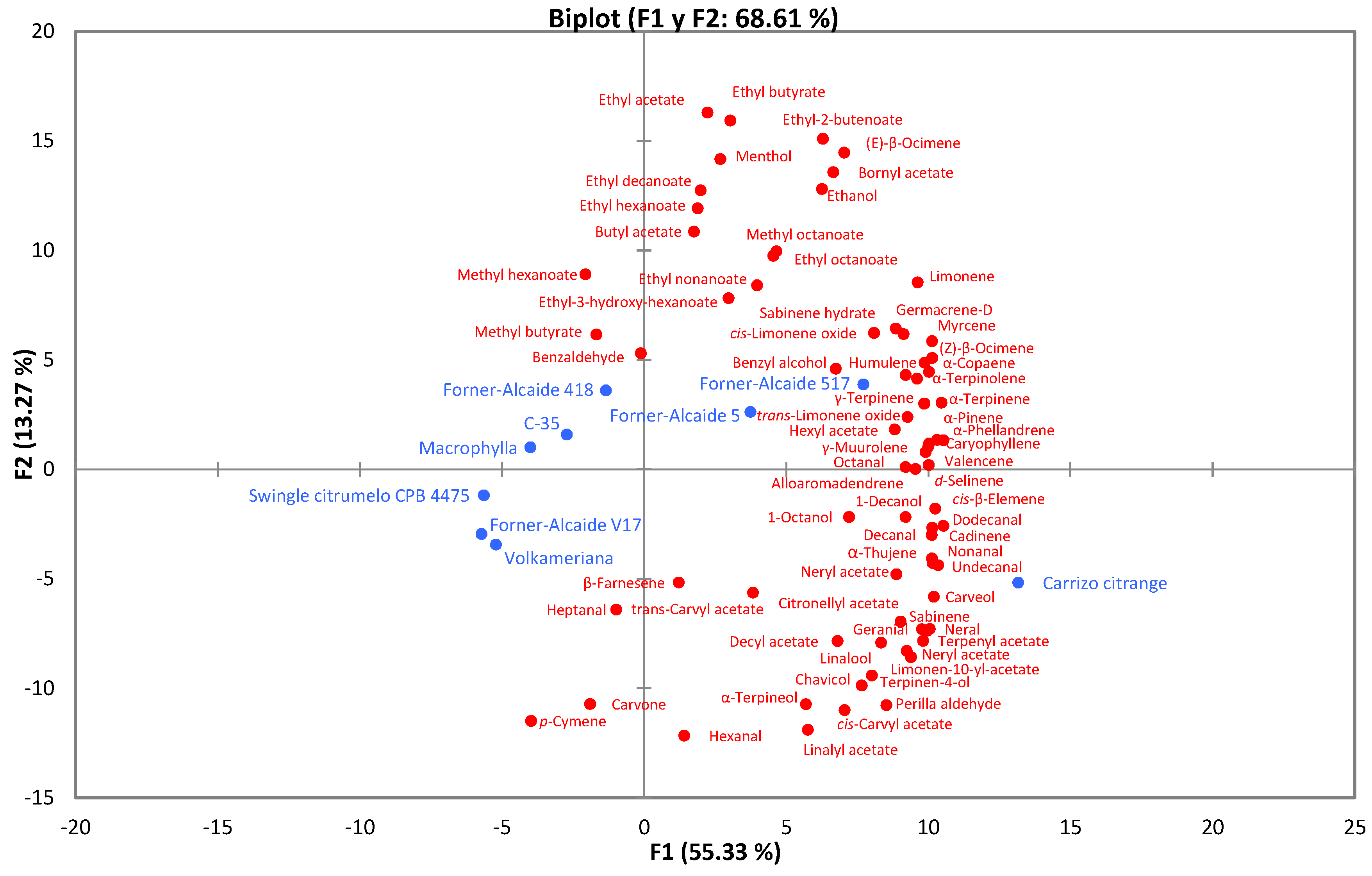

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ANOVA Ϯ | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** |

| Aldehydes | a | cd | bc | d | b | d | cd | bcd | a |

| Alcohols | a | b | b | b | b | b | b | b | a |

| Terpenes | ab | d | e | e | c | de | de | c | a |

| Esters | bc | cd | e | de | ab | cd | e | cd | a |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Forner-Giner, M.Á.; Sánchez-Bravo, P.; Hernández, F.; Primo-Capella, A.; Cano-Lamadrid, M.; Legua, P. Effect of Rootstock on the Volatile Profile of Mandarins. Foods 2023, 12, 1599. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods12081599

Forner-Giner MÁ, Sánchez-Bravo P, Hernández F, Primo-Capella A, Cano-Lamadrid M, Legua P. Effect of Rootstock on the Volatile Profile of Mandarins. Foods. 2023; 12(8):1599. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods12081599

Chicago/Turabian StyleForner-Giner, María Ángeles, Paola Sánchez-Bravo, Francisca Hernández, Amparo Primo-Capella, Marina Cano-Lamadrid, and Pilar Legua. 2023. "Effect of Rootstock on the Volatile Profile of Mandarins" Foods 12, no. 8: 1599. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods12081599

APA StyleForner-Giner, M. Á., Sánchez-Bravo, P., Hernández, F., Primo-Capella, A., Cano-Lamadrid, M., & Legua, P. (2023). Effect of Rootstock on the Volatile Profile of Mandarins. Foods, 12(8), 1599. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods12081599