Evaluation of Immune Modulation by β-1,3; 1,6 D-Glucan Derived from Ganoderma lucidum in Healthy Adult Volunteers, A Randomized Controlled Trial

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Identity of the Intervention

2.2. Study Population

2.2.1. Eligible/Inclusion Criteria

2.2.2. Non-Eligible/Exclusion Criteria

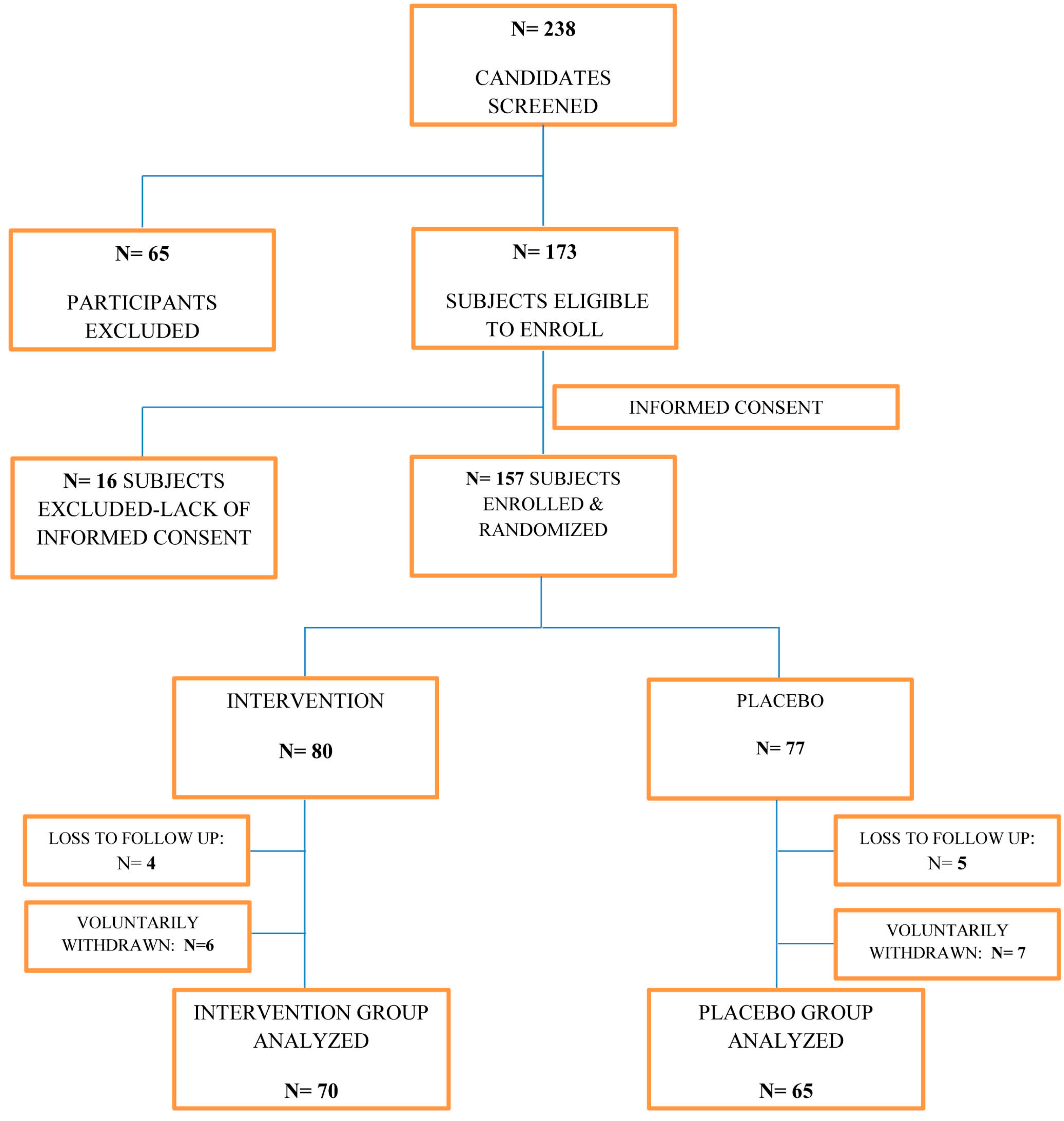

2.3. Study Design

2.4. Clinical and Laboratory Assays

2.5. Dose Determination

2.6. Interim Monitoring

2.7. Data Handling and Statistical Analysis

3. Results

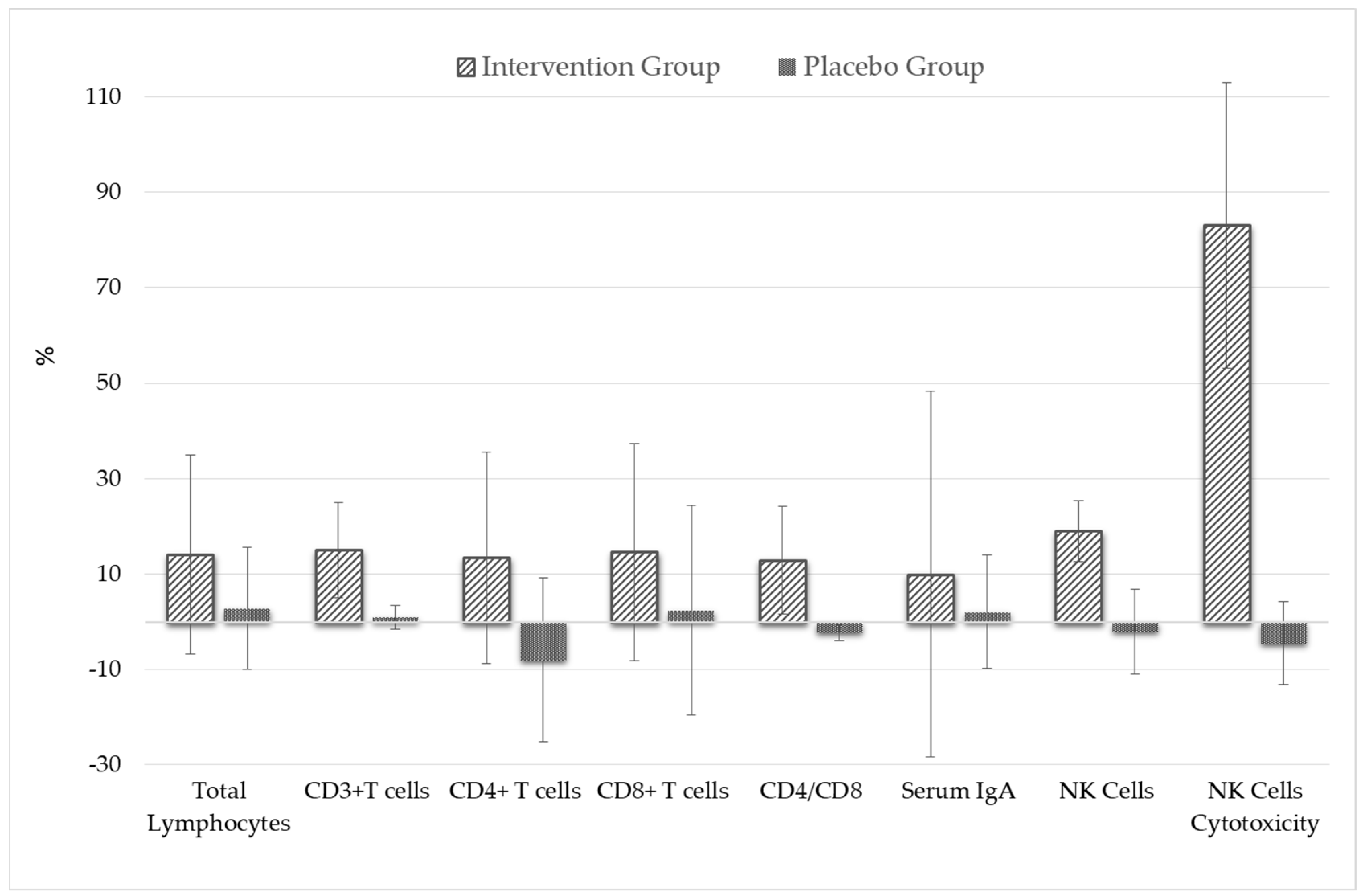

3.1. Primary Outcomes

3.2. Secondary Outcomes

3.3. Intra-Group Analyses

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Picard, C.; Al-Herz, W.; Bousfiha, A.; Casanova, J.L.; Chatila, T.; Conley, M.E.; Cunningham-Rundles, C.; Etzioni, A.; Holland, S.M.; Klein, C.; et al. Primary Immunodeficiency Diseases: An Update on the Classification from the International Union of Immunological Societies Expert Committee for Primary Immunodeficiency 2015. J. Clin. Immunol. 2015, 35, 696–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chinen, J.; Shearer, W.T. Secondary immunodeficiencies, including HIV infection. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2010, 125, S195–S203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, L.G.; Levin, M.J.; Ljungman, P.; Davies, E.G.; Avery, R.; Tomblyn, M.; Bousvaros, A.; Dhanireddy, S.; Sung, L.; Keyserling, H.; et al. 2013 IDSA clinical practice guideline for vaccination of the immunocompromised host. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2014, 58, 309–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, Y.T. Vaccine adjuvant materials for cancer immunotherapy and control of infectious disease. Clin. Exp. Vaccine Res. 2015, 4, 54–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geng, D.; Kaczanowska, S.; Tsai, A.; Younger, K.; Ochoa, A.; Rapoport, A.P.; Ostrand-Rosenberg, S.; Davila, E. TLR5 Ligand-Secreting T Cells Reshape the Tumor Microenvironment and Enhance Antitumor Activity. Cancer Res. 2015, 75, 1959–1971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Häcker, H.; Vabulas, R.M.; Takeuchi, O.; Hoshino, K.; Akira, S.; Wagner, H. Immune cell activation by bacterial CpG-DNA through myeloid differentiation marker 88 and tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor (TRAF) 6. J. Exp. Med. 2000, 192, 595–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhee, S.H.; Hwang, D. Murine TOLL-like receptor 4 confers lipopolysaccharide responsiveness as determined by activation of NF kappa B and expression of the inducible cyclooxygenase. J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 34035–34040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Björkbacka, H.; Fitzgerald, K.A.; Huet, F.; Li, X.; Gregory, J.A.; Lee, M.A.; Ordija, C.M.; Dowley, N.E.; Golenbock, D.T.; Freeman, M.W. The induction of macrophage gene expression by LPS predominantly utilizes Myd88-independent signaling cascades. Physiol. Genom. 2004, 19, 319–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabeta, K.; Georgel, P.; Janssen, E.; Du, X.; Hoebe, K.; Crozat, K.; Mudd, S.; Shamel, L.; Sovath, S.; Goode, J.; et al. Toll-like receptors 9 and 3 as essential components of innate immune defense against mouse cytomegalovirus infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 3516–3521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.K.; Deb, R.; Dey, S.; Chellappa, M.M. Toll-like receptor-based adjuvants: Enhancing the immune response to vaccines against infectious diseases of chicken. Expert Rev. Vaccines 2014, 13, 909–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, L.A.; Bryant, C.E.; Doyle, S.L. Therapeutic targeting of Toll-like receptors for infectious and inflammatory diseases and cancer. Pharmacol. Rev. 2009, 61, 177–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabroe, I.; Read, R.C.; Whyte, M.K.; Dockrell, D.H.; Vogel, S.N.; Dower, S.K. Toll-like receptors in health and disease: Complex questions remain. J. Immunol. 2003, 171, 1630–1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Ben, A.; Reville, J.; Calabrese, V.; Villa, N.N.; Bandyopadhyay, M.; Dasgupta, S. Immunotherapeutic Impact of Toll-like Receptor Agonists in Breast Cancer. Anticancer Agents Med. Chem. 2015, 15, 1134–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, M.C.; Shirey, K.A.; Pletneva, L.M.; Boukhvalova, M.S.; Garzino-Demo, A.; Vogel, S.N.; Blanco, J.C. Novel drugs targeting Toll-like receptors for antiviral therapy. Future Virol. 2014, 9, 811–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vecchione, R.; Quagliariello, V.; Giustetto, P.; Calabria, D.; Sathya, A.; Marotta, R.; Profeta, M.; Nitti, S.; Silvestri, N.; Pellegrino, T.; et al. Oil/water nano-emulsion loaded with cobalt ferrite oxide nanocubes for photo-acoustic and magnetic resonance dual imaging in cancer: In vitro and preclinical studies. Nanomedicine 2017, 13, 275–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Pompo, G.; Cortini, M.; Palomba, R.; Di Francesco, V.; Bellotti, E.; Decuzzi, P.; Baldini, N.; Avnet, S. Curcumin-Loaded Nanoparticles Impair the Pro-Tumor Activity of Acid-Stressed MSC in an In Vitro Model of Osteosarcoma. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 5760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, J.; Baker, C.; Cherry, L.; Dunne, E. Black elderberry (Sambucus nigra) supplementation effectively treats upper respiratory symptoms: A meta-analysis of randomized, controlled clinical trials. Complement. Ther. Med. 2019, 42, 361–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Q.; Liu, L.; Miron, A.; Klímová, B.; Wan, D.; Kuča, K. The antioxidant, immunomodulatory, and anti-inflammatory activities of Spirulina: An overview. Arch. Toxicol. 2016, 90, 1817–1840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasser, S. Medicinal Mushroom Science: History, Current Status, Future Trends, and Unsolved Problems. Int. J. Med. Mushrooms 2010, 12, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.L.; Lee, S.S.; Hou, S.M.; Chiang, B.L. Polysaccharide purified from Ganoderma lucidum induces gene expression changes in human dendritic cells and promotes T helper 1 immune response in BALB/c mice. Mol. Pharmacol. 2006, 70, 637–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quagliariello, V.; Basilicata, M.G.; Pepe, G.; De Anseris, R.; Di Mauro, A.; Scognamiglio, G.; Palma, G.; Vestuto, V.; Buccolo, S.; Luciano, A.; et al. Combination of Spirulina platensis, Ganoderma lucidum and Moringa oleifera Improves Cardiac Functions and Reduces Pro-Inflammatory Biomarkers in Preclinical Models of Short-Term Doxorubicin-Mediated Cardiotoxicity: New Frontiers in Cardioncology? J. Cardiovasc. Dev. Dis. 2022, 9, 423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vos, A.P.; M’Rabet, L.; Stahl, B.; Boehm, G.; Garssen, J. Immune-modulatory effects and potential working mechanisms of orally applied nondigestible carbohydrates. Crit. Rev. Immunol. 2007, 27, 97–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, G.D.; Herre, J.; Williams, D.L.; Willment, J.A.; Marshall, A.S.; Gordon, S. Dectin-1 mediates the biological effects of beta-glucans. J. Exp. Med. 2003, 197, 1119–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vetvicka, V.; Dvorak, B.; Vetvickova, J.; Richter, J.; Krizan, J.; Sima, P.; Yvin, J.C. Orally administered marine (1-->3)-beta-D-glucan Phycarine stimulates both humoral and cellular immunity. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2007, 40, 291–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, J.; Vetvicka, V.; Xia, Y.; Coxon, A.; Carroll, M.C.; Mayadas, T.N.; Ross, G.D. Beta-glucan, a “specific” biologic response modifier that uses antibodies to target tumors for cytotoxic recognition by leukocyte complement receptor type 3 (CD11b/CD18). J. Immunol. 1999, 163, 3045–3052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherwood, E.R.; Williams, D.L.; McNamee, R.B.; Jones, E.L.; Browder, I.W.; Di Luzio, N.R. Enhancement of interleukin-1 and interleukin-2 production by soluble glucan. Int. J. Immunopharmacol. 1987, 9, 261–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikewaki, N.; Iwasaki, M.; Kurosawa, G.; Rao, K.S.; Lakey-Beitia, J.; Preethy, S.; Abraham, S.J. β-glucan: Wide-spectrum immune-balancing food-supplement-based enteric (β-WIFE) vaccine adjuvant approach to COVID-19. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 2021, 17, 2808–2813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.C.; Quintin, J.; Cramer, R.A.; Shepardson, K.M.; Saeed, S.; Kumar, V.; Giamarellos-Bourboulis, E.J.; Martens, J.H.; Rao, N.A.; Aghajanirefah, A.; et al. mTOR- and HIF-1α-mediated aerobic glycolysis as metabolic basis for trained immunity. Science 2014, 345, 1250684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Töpfer, E.; Boraschi, D.; Italiani, P. Innate Immune Memory: The Latest Frontier of Adjuvanticity. J. Immunol. Res. 2015, 2015, 478408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Netea, M.G.; Quintin, J.; van der Meer, J.W. Trained immunity: A memory for innate host defense. Cell Host Microbe 2011, 9, 355–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. GRAS Notice No. 413: Beta-Glucans Derived from Ganoderma lucidum Mycelium. 10 August 2012. Available online: https://www.cfsanappsexternal.fda.gov/scripts/fdcc/?set=GRASNotices&id=413&sort=GRN_No&order=DESC&startrow=1&type=basic&search=413 (accessed on 12 March 2016).

- Gao, Y.; Tang, W.; Dai, X.; Gao, H.; Chen, G.; Ye, J.; Chan, E.; Koh, H.L.; Li, X.; Zhou, S. Effects of water-soluble Ganoderma lucidum polysaccharides on the immune functions of patients with advanced lung cancer. J. Med. Food 2005, 8, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehne, G.; Haneberg, B.; Gaustad, P.; Johansen, P.W.; Preus, H.; Abrahamsen, T.G. Oral administration of a new soluble branched beta-1,3-D-glucan is well tolerated and can lead to increased salivary concentrations of immunoglobulin A in healthy volunteers. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2006, 143, 65–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Lee, S.M.; Bae, I.Y.; Park, H.G.; Gyu Lee, H.; Lee, S. (1-3)(1-6)-β-glucan-enriched materials from Lentinus edodes mushroom as a high-fibre and low-calorie flour substitute for baked foods. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2011, 91, 1915–1919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Driscoll, M.; Hansen, R.; Ding, C.; Cramer, D.E.; Yan, J. Therapeutic potential of various beta-glucan sources in conjunction with anti-tumor monoclonal antibody in cancer therapy. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2009, 8, 218–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Allendorf, D.J.; Brandley, B. Yeast whole glucan particle (WGP) beta-glucan in conjunction with antitumour monoclonal antibodies to treat cancer. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 2005, 5, 691–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.N.; Nan, F.H.; Chen, S.; Wu, J.F.; Lu, C.L.; Soni, M.G. Safety assessment of mushroom β-glucan: Subchronic toxicity in rodents and mutagenicity studies. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2011, 49, 2890–2898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komura, D.L.; Ruthes, A.C.; Carbonero, E.R.; Gorin, P.A.; Iacomini, M. Water-soluble polysaccharides from Pleurotus ostreatus var. florida mycelial biomass. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2014, 70, 354–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruthes, A.C.; Carbonero, E.R.; Córdova, M.M.; Baggio, C.H.; Santos, A.R.; Sassaki, G.L.; Cipriani, T.R.; Gorin, P.A.; Iacomini, M. Lactarius rufus (1→3),(1→6)-β-D-glucans: Structure, antinociceptive and anti-inflammatory effects. Carbohydr. Polym. 2013, 94, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.S.; Chen, S.; Wang, W.; Lu, C.L.; Liu, C.F.; Chen, S.N. Oral Administration of MBG to Modulate Immune Responses and Suppress OVA-Sensitized Allergy in a Murine Model. Evid. Based. Complement. Alternat. Med. 2014, 2014, 567427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, A.B.; Jacob, S. A simple practice guide for dose conversion between animals and human. J. Basic. Clin. Pharm. 2016, 7, 27–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller, R.; Butt, H.; Noakes, P.S.; Kenyon, J.; Yam, T.S.; Calder, P.C. Influence of yeast-derived 1,3/1,6 glucopolysaccharide on circulating cytokines and chemokines with respect to upper respiratory tract infections. Nutrition 2012, 28, 665–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talbott, S.M.; Talbott, J.A. Baker’s yeast beta-glucan supplement reduces upper respiratory symptoms and improves mood state in stressed women. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2012, 31, 295–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mah, E.; Kaden, V.N.; Kelley, K.M.; Liska, D.J. Beverage Containing Dispersible Yeast β-Glucan Decreases Cold/Flu Symptomatic Days after Intense Exercise: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Diet. Suppl. 2020, 17, 200–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA Regulations Relating to Good Clinical Practice and Clinical Trials. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/science-research/clinical-trials-and-human-subject-protection/regulations-good-clinical-practice-and-clinical-trials (accessed on 21 January 2021).

- Lin, Z.B.; Zhang, H.N. Anti-tumor and immunoregulatory activities of Ganoderma lucidum and its possible mechanisms. Acta. Pharmacol. Sin. 2004, 25, 1387–1395. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wasser, S.P.; Weis, A.L. Therapeutic effects of substances occurring in higher Basidiomycetes mushrooms: A modern perspective. Crit. Rev. Immunol. 1999, 19, 65–96. [Google Scholar]

- Henao, S.L.D.; Urrego, S.A.; Cano, A.M.; Higuita, E.A. Randomized Clinical Trial for the Evaluation of Immune Modulation by Yogurt Enriched with β-glucan from Lingzhi or Reishi Medicinal Mushroom, Ganoderma lucidum (Agaricomycetes), in Children from Medellin, Colombia. Int. J. Med. Mushrooms 2018, 20, 705–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demir, G.; Klein, H.O.; Mandel-Molinas, N.; Tuzuner, N. Beta glucan induces proliferation and activation of monocytes in peripheral blood of patients with advanced breast cancer. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2007, 7, 113–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, G.C.; Chan, W.K.; Sze, D.M. The effects of beta-glucan on human immune and cancer cells. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2009, 2, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, W.K.; Law, H.K.; Lin, Z.B.; Lau, Y.L.; Chan, G.C. Response of human dendritic cells to different immunomodulatory polysaccharides derived from mushroom and barley. Int. Immunol. 2007, 19, 891–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noss, I.; Ozment, T.R.; Graves, B.M.; Kruppa, M.D.; Rice, P.J.; Williams, D.L. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of fungal β-(1→6)-glucan in macrophages. Innate. Immun. 2015, 21, 759–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobb, B.A.; Wang, Q.; Tzianabos, A.O.; Kasper, D.L. Polysaccharide processing and presentation by the MHCII pathway. Cell 2004, 117, 677–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahoo, P.K.; Mukherjee, S.C. Effect of dietary beta-1,3 glucan on immune responses and disease resistance of healthy and aflatoxin B1-induced immunocompromised rohu (Labeo rohita Hamilton). Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2001, 11, 683–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuller, R.; Moore, M.V.; Lewith, G.; Stuart, B.L.; Ormiston, R.V.; Fisk, H.L.; Noakes, P.S.; Calder, P.C. Yeast-derived β-1,3/1,6 glucan, upper respiratory tract infection and innate immunity in older adults. Nutrition 2017, 39–40, 30–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McFarlin, B.K.; Carpenter, K.C.; Davidson, T.; McFarlin, M.A. Baker’s yeast beta glucan supplementation increases salivary IgA and decreases cold/flu symptomatic days after intense exercise. J. Diet. Suppl. 2013, 10, 171–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Egmond, M.; Damen, C.A.; van Spriel, A.B.; Vidarsson, G.; van Garderen, E.; van de Winkel, J.G. IgA and the IgA Fc receptor. Trends Immunol. 2001, 22, 205–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.S.; Ogbomo, H.; Mansour, M.K.; Xiang, R.F.; Szabo, L.; Munro, F.; Mukherjee, P.; Mariuzza, R.A.; Amrein, M.; Vyas, J.M.; et al. Identification of the fungal ligand triggering cytotoxic PRR-mediated NK cell killing of Cryptococcus and Candida. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, P.S.; Suck, G.; Nowakowska, P.; Ullrich, E.; Seifried, E.; Bader, P.; Tonn, T.; Seidl, C. Selection and expansion of natural killer cells for NK cell-based immunotherapy. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2016, 65, 477–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosso, F.; Quagliariello, V.; Tortora, C.; Di Lazzaro, A.; Barbarisi, A.; Iaffaioli, R.V. Cross-linked hyaluronic acid sub-micron particles: In vitro and in vivo biodistribution study in cancer xenograft model. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2013, 24, 1473–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Intervention Group (n = 70) | Placebo Group (n = 65) | p Value * | Statistically Significant Difference between Study Groups |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | |||

| Primary outcome | ||||

| Total Lymphocytes (cells/µL) | 1932.3 ± 508.5 | 1820.6 ± 438.2 | 0.557 | p > 0.05 |

| CD3+ T lymphocytes (cells/µL) | 1389.2 ± 392.0 | 1285.5 ± 323.1 | 0.615 | |

| CD4+ T lymphocytes (cells/µL) | 1086.9 ± 374.5 | 1018.7 ± 294.8 | 0.928 | |

| CD8+ T lymphocytes (cells/µL) | 782.2 ± 260.7 | 763.0 ± 240.3 | 0.619 | |

| CD4/CD8 cell ratio | 1.39 ± 0.62 | 1.33 ± 0.57 | 0.864 | |

| Serum IgA (mg/dL) | 262.3 ± 112.8 | 247.1 ± 121.2 | 0.105 | |

| NK Cells (cells/µL) | 285.5 ± 143.1 | 278.9 ± 130.7 | 0.093 | |

| NK Cells Cytotoxicity (%) | 36.8 ± 9.5 | 37.5 ± 9.1 | 0.431 | |

| Secondary Outcome | ||||

| AST (mg/dL) | 24.8 ± 8.6 | 23.2 ± 7.9 | 0.503 | p > 0.05 |

| ALT (mg/dL) | 15.2 ± 6.3 | 14.9 ± 5.8 | 0.102 | |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.86 ± 0.08 | 0.83 ± 0.07 | 0.114 | |

| RBC (106/µL) | 4.75 ± 0.41 | 4.93 ± 0.54 | 0.352 | |

| HB (g/dL) | 14.52 ± 2.01 | 14.70 ± 1.94 | 0.527 | |

| HCT (%) | 43.31 ± 4.25 | 44.12 ± 3.87 | 0.738 | |

| Platelet Counts (103/µL) | 264.82 ± 72.13 | 259.15 ± 68.42 | 0.570 |

| Parameter | Intervention Group (n = 70) | Placebo Group (n = 65) | p Value * | Statistically Significant Difference between Study Groups |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | |||

| Primary outcome | ||||

| Total Lymphocytes (cells/µL) | 2206.3 ± 614.5 | 1872 ± 494.3 | 0.012 * | Yes, increase |

| CD3+ T lymphocytes (cells/µL) | 1598.8 ± 431.1 | 1299.4 ± 331.2 | 0.001 * | Yes, increase |

| CD4+ T lymphocytes (cells/µL) | 1233.3 ± 457.8 | 936.7 ± 243.8 | 0.003 * | Yes, increase |

| CD8+ T lymphocytes (cells/µL) | 896.9 ± 320.3 | 754.9 ± 187.2 | 0.025 * | Yes, increase |

| CD4/CD8 cell ratio | 1.57 ± 0.69 | 1.30 ± 0.58 | 0.036 * | Yes, increase |

| Serum IgA (mg/dL) | 288.7 ± 156.1 | 252.3 ± 135.6 | 0.048 * | Yes, increase |

| NK Cells (cells/µL) | 341.2 ± 152.3 | 284.6 ± 142.4 | 0.045 * | Yes, increase |

| NK Cells Cytotoxicity (%) | 67.4 ± 12.4 | 35.8 ± 8.3 | 0.001 * | Yes, increase |

| Secondary Outcome | ||||

| AST (mg/dL) | 25.6 ± 9.3 | 23.7 ± 8.5 | 0.426 | No, unchanged |

| ALT (mg/dL) | 15.4 ± 6.4 | 15.6 ± 6.0 | 0.124 | No, unchanged |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.83 ± 0.1 | 0.90 ± 0.12 | 0.325 | No, unchanged |

| RBC (106/µL) | 4.68 ± 0.73 | 4.98 ± 0.67 | 0.311 | No, unchanged |

| HB (g/dL) | 14.12 ± 3.40 | 13.94 ± 2.73 | 0.570 | No, unchanged |

| HCT (%) | 44.13 ± 5.03 | 43.98 ± 4.68 | 0.694 | No, unchanged |

| Platelet Counts (103/µL) | 258.63 ± 63.52 | 249.31 ± 59.45 | 0.627 | No, unchanged |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, S.-N.; Nan, F.-H.; Liu, M.-W.; Yang, M.-F.; Chang, Y.-C.; Chen, S. Evaluation of Immune Modulation by β-1,3; 1,6 D-Glucan Derived from Ganoderma lucidum in Healthy Adult Volunteers, A Randomized Controlled Trial. Foods 2023, 12, 659. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods12030659

Chen S-N, Nan F-H, Liu M-W, Yang M-F, Chang Y-C, Chen S. Evaluation of Immune Modulation by β-1,3; 1,6 D-Glucan Derived from Ganoderma lucidum in Healthy Adult Volunteers, A Randomized Controlled Trial. Foods. 2023; 12(3):659. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods12030659

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Shiu-Nan, Fan-Hua Nan, Ming-Wei Liu, Min-Feng Yang, Ya-Chih Chang, and Sherwin Chen. 2023. "Evaluation of Immune Modulation by β-1,3; 1,6 D-Glucan Derived from Ganoderma lucidum in Healthy Adult Volunteers, A Randomized Controlled Trial" Foods 12, no. 3: 659. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods12030659

APA StyleChen, S.-N., Nan, F.-H., Liu, M.-W., Yang, M.-F., Chang, Y.-C., & Chen, S. (2023). Evaluation of Immune Modulation by β-1,3; 1,6 D-Glucan Derived from Ganoderma lucidum in Healthy Adult Volunteers, A Randomized Controlled Trial. Foods, 12(3), 659. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods12030659