Abstract

Ingestion of food or water contaminated with pathogenic bacteria may cause serious diseases. The One Health approach may help to ensure food safety by anticipating, preventing, detecting, and controlling diseases that spread between animals, humans, and the environment. This concept pays special attention to the increasing spread and dissemination of antibiotic-resistant bacteria, which are considered one of the most important environment-related human and animal health hazards. In this context, the development of innovative, versatile, and effective alternatives to control bacterial infections in order to assure comprehensive food microbial safety is becoming an urgent issue. Bacteriophages (phages), viruses of bacteria, have gained significance in the last years due to the request for new effective antimicrobials for the treatment of bacterial diseases, along with many other applications, including biotechnology and food safety. This manuscript reviews the application of phages in order to prevent food- and water-borne diseases from a One Health perspective. Regarding the necessary decrease in the use of antibiotics, results taken from the literature indicate that phages are also promising tools to help to address this issue. To assist future phage-based real applications, the pending issues and main challenges to be addressed shortly by future studies are also taken into account.

1. Introduction

Food and water are the main routes of transmission of more than 200 known infectious diseases, many of which are attributed to bacteria [1]. Among these, the main bacterial foodborne pathogens, in terms of occurrence and seriousness, are Salmonella enterica, Campylobacter spp., Escherichia coli, Listeria monocytogenes, Staphylococcus aureus, and Clostridium botulinum. Considering waterborne diseases, the genus Vibrio also enters this important group, besides E. coli and S. enterica serovar Typhi [2]. Besides the potential serious clinical symptoms, food- and water-borne diseases represent an enormous economic burden for health systems (treatment, potential hospitalization, loss of working days, etc.) and some of them, such us L. monocytogenes, can be fatal to humans. Accordingly, measures for the prevention of their presence and proliferation in food products should be comprehensive and strict.

On the other hand, food production is a complex and multifaceted procedure which starts from the growth of animals and the harvest of plants through different practices up to the point of their consumption by customer. Along this path, there are many chances for bacterial contamination. Many of those pathogenic bacteria are considered as ubiquitous and normal microbiota in the environment and in animals. They may cause infections as zoonotic pathogens, usually infecting humans through cross-contamination, for instance, during improper food handling and preparation, especially if the food products are stored under poor conditions [3,4,5].

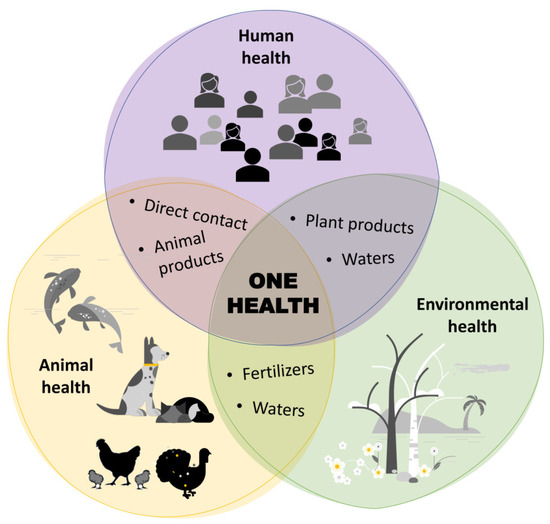

To reduce the risk, several control measures may be taken to preserve food from contamination with dangerous microorganisms and to reduce foodborne diseases, accordingly. In this sense, the One Health approach is promoted by global organizations for the health of people, animals, plants, and the environment [6]. This promotes a transformation of the agrifood system, which involves many factors, such as sustainable agriculture; animal, plant, forest, and aquaculture health; antimicrobial resistance (AMR); and, of course, food safety [6]. In agreement with this definition, the One Health approach (Figure 1) also ensures food safety by anticipating, preventing, detecting, and controlling pathogens that spread between animals and humans, with special attention paid to AMR bacteria. Indeed, AMR is considered one of the most important environment-related global threats, expected to be the leading cause of human mortality by 2050 [7,8].

Figure 1.

Interconnection between humans, animals, and the environment within the One Health concept.

Considering the emergence of multidrug-resistant (MDR) bacteria, the development of innovative and effective alternatives to control bacterial infections is becoming an urgent issue. In this scenario, bacteriophages or phages, which are viruses that infect bacteria and the most abundant and diverse biological entities worldwide, are currently gaining an important prominence in the request of new effective alternatives to treat bacterial diseases in humans, animals, and plants [9,10]. Moreover, this “phage biocontrol”, targeting specific pathogenic bacteria, is also increasingly accepted as a natural, effective, and inexpensive food (and feed) safety strategy [11,12].

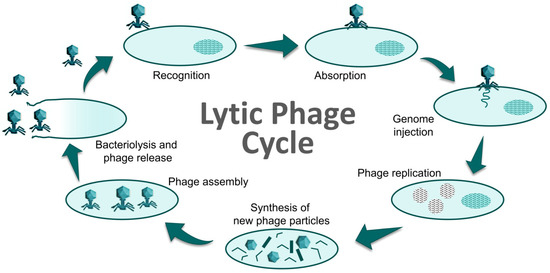

Phages are usually classified according to the strategies they use to escape their hosts, into lysogenic (temperate) phages and lytic (virulent) phages [13,14]. Lytic phages cause the death (lysis) of their host at the end of their lytic cycle (Figure 2) and, consequently, these are the most suitable phages to be used in biocontrol applications [15]. Because of their high specificity, phages eliminate target bacteria without affecting the normal and beneficial microbiota of the host, the food, or the environment. Moreover, as they are already widely present in the environment, phages are not supposed to have any harmful consequence on the quality of food or animal and human health [16]. The safety and effectiveness of phage-based biocontrollers is reflected in the fact that several preparations have been approved for use in food [17]. In addition, they can be used alone or in combination with other phages (phage cocktails) in order to achieve a broader host range, or with antibiotics or disinfectants to control bacterial infections more effectively [18]. In fact, phage-antibiotic synergy (knowns as the PAS effect), has been observed in some phage–antibiotic combinations [19].

Figure 2.

Cycle of a lytic phage resulting in cell death (bacteriolysis). Adapted from [20].

Phages are potent antimicrobial agents against most pathogenic bacteria, and can be usefully implemented for their environmentally-friendly application at each stage of the farm-to-fork continuum. This corresponds to the One Health concept for reducing foodborne diseases: they can be used in many applications, such as phage-therapy in animal production, cleaning of the livestock, disinfection and sanitation of equipment and contact surfaces on farms and in industry, biocontrols in fresh meats and produce, and also as natural preservatives to extend product shelf-life [1,21,22].

Nevertheless, many factors, such as the target bacteria, the application route, the phage administration timing (prophylactic vs. therapeutic), the number of phage administrations (single vs. repeated), the number of phages used (single vs. cocktail), food composition, or the storage temperature, for instance, are factors to be taken into account, as they may imply differences in the results regarding the effects of phages on the biocontrol of pathogens in foods and animals [15,23].

2. Phage Biocontrol in Animal Husbandry for Food Production

The raise of MDR bacteria causing dissemination of AMR requires alternative strategies to combat pathogenic bacteria. Phages possess some unique characteristics, such as high species-specific nature, relatively easy handling, self-replication, and self-limiting [24,25], that make them a promising alternative for effectively inhibiting the colonization of pathogenic bacteria and reducing animal and zoonotic diseases [17,26,27].

2.1. Control of Campylobacter and Salmonella in Broilers

Campylobacter and Salmonella are widely distributed in most warm-blooded animals, such as poultry, and contaminate foods during slaughter, handling, and/or carcass processing. The main source of human infection for both bacteria is the consumption of contaminated products of animal origin, mainly undercooked eggs and poultry meat [28]. Due to their importance in public health, both bacteria are controlled by the European Community legislation. However, despite efforts to control them, new foodborne outbreaks (FBO) of salmonellosis and campylobacteriosis emerge every year [28,29].

Campylobacter is the most common foodborne pathogen causing zoonotic illnesses in humans. The majority of campylobacteriosis cases are caused by Campylobacter jejuni (∼89%) and Campylobacter coli (∼10%), with only a few cases (<1%) associated with C. fetus, C. upsaliensis, and C. lari [28]. Although treatment is not generally required, quinolones, macrolides, and tetracyclines are antibiotics used to combat severe infections [30,31]. The alarming emergence of Campylobacter resistance to these drugs compromises the effectiveness of therapeutic treatments and lead the World Health Organization (WHO) to include Campylobacter in its global priority list of antibiotic-resistant pathogens [32].

Poultry is considered the natural primary reservoir of Campylobacter spp., with C. jejuni being the predominant species colonizing broiler chickens. Colonization naturally occurs by horizontal transmission from the environment, and the infection rapidly spreads within the flock, reaching more than 107 CFU/g in their intestinal tract before slaughter [33]. The prevention and control of Campylobacter in poultry is a food safety issue of high priority, since it is widely accepted as a significant risk factor of human campylobacteriosis. Reducing the Campylobacter load in broiler intestines by 3 logs prior to slaughter was estimated to reduce the risk of human campylobacteriosis attributable to the consumption of poultry meat by 58% [34].

Even though no phage-based products with specific activity against Campylobacter are commercially available yet, phage biocontrol is one of the most promising alternatives under development to address the reduction in this pathogen in the poultry reservoir [35]. Campylobacter-infecting phages (also called campylophages) have been isolated wherever their hosts are present, including in both poultry environmental samples and food products [33,36]. Campylophages have been classified into three groups (groups I, II, and III) according to their genome size [37]. Group I phages (320 kb) have rarely been isolated, whereas phages of group II (180 kb; Cp220virus) and group III (140 kb; Cp8virus) are common and contact their target hosts via flagella and capsule polysaccharide (CPS) receptors, respectively [33].

Different studies have reported the use of campylophages to reduce Campylobacter counts in the gastrointestinal tracts of broiler chickens (Table 1), without affecting their health and well-being [38] or their gut microbiome [39]. These studies have shown reductions of up to 5 log in the cecal counts of Campylobacter colonized chickens, including AMR Campylobacter strains [38]. As mentioned initially, the high variability reported in Campylobacter reduction might be dependent on a number of factors, such as the susceptibility of each strain to the applied phages [40,41,42,43], the route of phage administration [41,42], the dose and timing of application [38,39,40,42,44,45] or the development of phage-resistant Campylobacter mutants [40,41]. The use of polyphage therapy (campylophage cocktails) instead of single phages has been also studied for a broader host range [39,41,42,44]. Unfortunately, achieving complete Campylobacter elimination in broilers may be a difficult task. Nevertheless, the careful design and application of campylophage cocktails targeting different cell receptors (containing both group II and group III campylophages) has been suggested as the best approach to successfully combat Campylobacter, resulting in an efficient reduction in Campylobacter at the farm level, with a significant impact on food safety and public health [39,46].

Salmonella is the second zoonotic pathogen responsible for human gastrointestinal diseases. In fact, millions of human salmonellosis cases are reported worldwide every year, resulting in thousands of deaths. In the United States, Salmonella causes around 1.2 million cases every year, of which there are around 23,000 hospitalizations and 450 deaths [47]. In Europe, a total of 60,050 confirmed cases in humans were reported in 2021 by the European Surveillance System [28], reporting an increase of 14.3% in comparison with the previous year. Different serovars have been associated with salmonellosis, yet Salmonella Enteritidis, followed by Salmonella Typhimurium, has been the most common serovar related to FBO in humans worldwide [48], as well as in the EU [28].

Table 1.

Examples of the use of bacteriophages for reducing the incidence of Campylobacter spp. and Salmonella spp. in broilers (pre-harvest stages of production).

Table 1.

Examples of the use of bacteriophages for reducing the incidence of Campylobacter spp. and Salmonella spp. in broilers (pre-harvest stages of production).

| Animal (Age) | Bacteria Load 1,2 | Phage | Application Method and Dose 3 | Bacterial Reduction | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Campylobacter spp. | |||||

| Chickens (38 days old) | C. jejuni AMR * 108 (1) | ϕ16-izsam ϕ7-izsam | Oral (37 dpi); single dose; sequential application (24 h) 1 day before slaughtering. 107 108 | 1 log reduction 2 log reduction | [38] |

| Chickens (24 days old) | C. jejuni HPC5 108 (1) | Cocktail (2): CP20 GII CP30A GIII | Oral (4 dpi); single dose; 107 | 2.4 and 1.3 log reduction after 2 and 5 dpt | [39] |

| Chickens (25 days old) | C. jejuni HPC5 107 (1) C. jejuni GIIC8 107 (1) | CP34 GIII CP8 GIII CP8 GIII | Oral (5 dpi); single dose; 105–107–109 | 0.5–4 log reduction Marginal reductions Initial 5 log reduction and 2 log reduction after 5 dpt | [40] |

| Chickens (38 days old) | C. jejuni 2140CD1 107 (1) C. coli A11 106 (1) | Cocktail (3): ϕCcoIBB35 GII ϕCcoIBB37 GII ϕCcoIBB12 GII | Oral (7 dpi); single dose; 106 In feed (7dpi); single dose; 107 | 1.2 and 1.7 log reduction after 2 and 7 dpt 2 log reduction after 2 and 7 dpt | [41] |

| 3 field trials Chickens (36 days old) | C. jejuni 102–107 (1) | Cocktail (4): NCTC12672 GIII NCTC12673 GIII NCTC12674 GIII NCTC12678 GIII | Drinking water (7 dpi); single dose; 107 | Up to 3.2 log reduction in one field trial No reduction in two field trials | [42] |

| Chickens (47 days old) | Naturally colonized chickens | Cocktail (4): PH5, PH8, PH11, PH13 | Oral; single dose; 107 | 1.3 log reduction after 1 dpt | [43] |

| Chickens (10 days old) Chickens (32 days old) | C. jejuni C356 108–109 (1) | NCTC12671 GIII Cocktail (2): NCTC12671 GIII NCTC12669 GIII | Oral (5dpi); 5 doses (24 h interval); 1010–1011 Oral (7dpi); 4 doses (24 h interval); 1010–1011 | Initial 3 log reduction followed by 1 log reduction over 20 dpt Initial 1.5 log reduction followed by 1 log reduction over 20 dpt | [44] |

| Chickens (25 days old) | C. jejuni HPC5 107 (1) C. coli OR12 109 (1) | CP220 GII | Oral (5 dpi); single dose; 107 109 | 2 log reduction 2 log reduction | [45] |

| Chickens (27 days old) | C. jejuni 3871 109 (1) | CP14 GIII Cocktail (2): CP14 GIII CP81 GIII CP14 GIII CP68 GII | Oral (7 dpi); single dose; 5 × 108 Oral (7 dpi); single dose; 5 × 108 Oral (7 dpi); single dose; sequential application (24 h); 5 × 108–5 × 1010 | 1 log reduction after 3 dpt No reduction 3 log reduction after 3 dpt | [46] |

| Salmonella spp. | |||||

| Layer hens (6 weeks old) | S. Gallinarum KVCC BA00722 108 (2) | ST4 L13 SG3 | Feed additive 108 7 days before and 21 dpi | 50% reduction in liver and spleen after 7 dpi; 70% survival rate 75% and 50% reduction in liver and spleen after 7 and 14 dpi, respectively; 75% survival rate 25% and 50% reduction in liver and spleen after 7 and 14 dpi, respectively; 50% survival rate | [49] |

| Chickens (36 days old) | S. Enteritidis P125109 S. Typhimurium 4/74 108 (2) | Phage cocktail: ϕ151, ϕ25 ϕ10 | Oral; single dose 1011 | 1.53 log and 3.48 log reduction of S. Enteritidis and S. Typhimurium, respectively | [50] |

| Chickens (6-10 days) Chickens (31-35 days) | S. Enteritidis (PT4) 6 × 106 (2) | Phage cocktail: CNPSA1 CNPSA3 CNPSA4 | Early treatment after challenge: drinking water for 5 consecutive days (from 6 to 10 dpi) Later treatment after challenge: drinking water for 5 consecutive days (from 31 to 35 dpi) 109 | 1.08 log reduction after later treatment | [51] |

| Chickens (1 day old) (6 days old) | S. Enteritidis 103 (2) | Single phage or cocktail: CB4ϕ WT45ϕ | Cloacal drop 1 h pi: WT45ϕ: 109 Oral delivery 1 h pi: WT45ϕ: 108 CB4ϕ: 108 Cocktail: 108 | Reduction in Salmonella detection to 36% Reduction in Salmonella detection to 70%, 65%, and 45% after 1 dpt No significant differences after 48 h | [52] |

| Chickens (10 days old) | S. Enteritidis 105 (2) | Phage cocktail | Coarse spray or drinking water 108 | Reduction in Salmonella detection to 72.7% by aerosol-spray | [53] |

| Layer hens (40 weeks old) | S. Enteritidis (SENAR) 108 (2) | Phage cocktail: SP-1 STP-1 | Feed additive: 0.2% of the phage cocktail | 0.9, 0.57, and 0.38 log reduction in cecum, liver, and spleen at 7 dpt 0.86 log reduction in cecum at 6 dpt | [54] |

| Layer hens (60 weeks old) | Natural infection | Autophage (AP) Wild-type phage | Spray applications 108 Two single applications in 24 h intervals | 1.78 log reduction in feces samples Total elimination of Salmonella from the environment | [55] |

| Chickens (1 to 35 days) | S. Enteritidis 104 (2) | Bafasal (4 phages cocktail) | Feed additive daily 106 | 1 log reduction at day 35 of study | [56] |

1 Cecal/fecal content (CFU/g); 2 bacterial oral infection dose (CFU/animal); 3 administered phage dose (PFU/mL); dpt: days post-treatment; dpi: days post-infection; pi: post-infection; * AMR: antimicrobial resistant strain.

Although the use of antibiotics has been limited to therapeutics in Europe since 2012, the presence of resistant strains is being considered as a human and veterinary health concern. For instance, the data published by the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) and the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (EDCD) in 2022 reported resistance of Salmonella against sulfonamides/sulfamethoxazole (30.1%), tetracyclines (31.2%), and ampicillin (29.8%) [57]. Moreover, resistance to ciprofloxacin was reported in 14.1% of the isolates, which was a slight increase compared with the previous report. Resistance to cefotaxime or ceftazidime was observed to be generally very low (<1%) among Salmonella spp. of the isolates. These antimicrobials represent the most important antimicrobial classes (fluoroquinolones and third-generation cephalosporins) used for the treatment of salmonellosis, and they have been classified by the WHO as the highest priority [58].

The current situation has encouraged the search for new alternatives, such as the use of phages against Salmonella [59]. Several studies showed phage biocontrol success in the poultry sector (Table 1), as it has been shown that phages reduced side effects compared to traditional antibiotic treatments due to their specificity [60]. At the field level, different publications have demonstrated the efficacy of phages in reducing Salmonella concentration in chickens. Zbikowska et al. infected chickens with Salmonella Gallinarum, and then animals were fed with a cocktail of phages, leading to a significant decrease in Salmonella in the organs as well as in the mortality of the chickens [61]. Similar results have been previously reported, showing that phages are a promising tool and an effective alternative to antibiotics [49,62]. Further, reductions of 1.53 log and 3.48 log of S. Enteritidis and S. Typhimurium, respectively, were reached after the application of a single dose of a phage cocktail [50]. Likewise, statistically significant differences in S. Enteritidis reduction after a later phage treatment demonstrated that the application of phages at late stages of broiler growth may be a promising measure for the control of this bacterium in future stages of the production chain [51].

2.2. Control of Listeria Monocytogenes in Animals

L. monocytogenes is a well-known pathogen responsible for listeriosis, one of the most serious food- and feed-borne zoonotic diseases worldwide. This pathogen can reach food products by contaminated raw materials or by cross-contamination during different steps of food processing [63,64]. Listeriosis in domestic animals is usually transmitted through the ingestion of contaminated feed and/or pet food, although it can also be transmitted through the upper respiratory tract mucosa, conjunctiva, and wounds [65]. Animal listeriosis is generally associated with encephalitis, abortion, septicemia, and mastitis in ruminants, but also in swine, horses, birds, rodents, fishes, and crustaceans, although an even wider range of animal species can also be affected.

Since animals act a reservoir and a main source of L. monocytogenes to humans, using the One Health concept, it would be reasonable to treat animals to control the introduction of Listeria into the food chain. However, the absence of harmonized regulations regarding the presence of L. monocytogenes at primary production has led to the low quantity of reported data [28]. Accordingly, as far as we know, there is still a lack of investigation into the use of phages for the control of L. monocytogenes in animals, and few examples have been found in the literature. The use of phage P100 has been proposed for the treatment of animals (including humans) infected with L. monocytogenes [66], but no further publications have been found regarding the application conditions or phage effectivity. Only one recent publication has demonstrated the potential therapeutic effect of phage LP8 against listeriosis in mice and the feasibility of a combined therapy to reduce the use of antibiotics in animals [67]. As more published research continues to focus on the application of Listeria phages in foods and food processing environments, this topic will be discussed in the sections below.

2.3. Control of Vibrio spp. in Aquaculture

Water also represents one of the most important methods of dissemination of AMR. Pathogenic microorganisms, such as Vibrio spp., occur naturally in water [68] and are the most important environmental human pathogen from aquatic and marine habitats [69,70]. In animals, vibriosis is responsible for important economic losses in turbot, salmonids, sea bass, and shrimps [71,72]. The incidence of all of these infections is rising, favored by the rising of sea water temperature due to climate change [68,73,74]. Additionally, as the global aquaculture production is increasing and is progressively growing into an intensive industry, the concentration of fishes in larger farms also may cause an increase in bacterial disease occurrence [71,73].

Although control and hygiene measures are important hurdles to the occurrence of an outbreak, antibiotics are still the most effective chemical agents for controlling Vibrio spp. Their abuse has caused the emergence of multidrug-resistant strains, and many Vibrios have already become highly resistant to most commercially available antibiotics [75,76,77]. With only a few antibiotics approved for aquaculture, this food source industry is continuously facing the threat of bacterial contamination. Furthermore, to mitigate antibiotic-resistant microorganisms, many countries have introduced strict antibiotic-handling programs, which include proper dosage of antibiotic treatment and objectives such as a 50% reduction in the use of antibiotics by 2030 in aquaculture [78]. Accordingly, the development of alternative biocontrol agents against Vibrio for aquatic hatcheries is also an urgent need, especially where vaccines cannot be applied. Some studies have shown the applicability of phages to reduce human pathogenic Vibrio spp. from aquaculture (Table 2).

Table 2.

Examples of the use of phages for controlling or reducing the incidence of different Vibrio spp. in aquaculture and closely related conditions.

These studies have demonstrated the potential of phages controlling V. parahaemolyticus in vivo. For instance, the VP10 phage cocktail significantly reduced V. parahaemolyticus to undetectable numbers in mussels [79], and pVp-1 reduced bacterial growth by five orders of magnitude when phages were added into oysters’ tanks [80]. Additionally, the VPG01 phage remarkably reduced the presence of V. parahaemolyticus in artificial seawater and in the aquatic crustacean Artemia franciscana [81].

For the last two decades, phages have been also studied for controlling animal vibriosis (Table 2), most of them specifically targeting the fish pathogen Vibrio harveyi. It has been demonstrated that phages can reduce the mortality of infected shrimp larvae, from 75% (without phages) up to 20% [82]. More recently, a phage named Virtus has shown an important protective effect against mortality caused by V. harveyi on seabream larvae [83]. Phages have been also demonstrated to be useful weapons against V. anguillarum infections. The application of the phage CHOED increased Salmo salar survival rates in aquaculture conditions from 60% to 100% [84]. A similar result, namely a mortality rate less than 3%, was achieved using the VP-2 phage on zebrafish larvae as an infection model [85].

In aquaculture, phages may have additional advantages: Their specificity allows them to kill the target pathogenic Vibrio spp., while being unable to kill beneficial Vibrio spp. in fish microbiota. In addition, phages are especially easy to administer in water, and have the benefit of treating both the farm environment (water and facilities) and the farmed species [88]. This evidence suggest that phage therapy could be a viable alternative to protect and treat fish against these bacteria in different developmental stages, as well as preventing water-borne human Vibrio infections.

3. Phage Biocontrol at the Post-Harvest and Post-Slaughtering Stage

Pathogenic bacteria mostly contaminate the food products during the steps of harvesting, slaughtering, processing, and packing, and are becoming resistant to available antibiotics. Due to their potential, at present, there are many studies on post-harvest phage biocontrol interventions (direct food applications) for L. monocytogenes, Salmonella spp., C. jejuni, Vibrio spp., E. coli O157:H7, Cronobacter sakazakii, Shigella spp., and Staphylococcus aureus [89,90,91,92,93], among others. Below, we review some studies on the effectiveness of bacteriophage biocontrol of the selected foodborne pathogens on different food products.

3.1. Campylobacter

The consumption of contaminated raw and undercooked poultry meat is the major source of human campylobacteriosis [28]. The application of specific phages has been explored as a pre-harvest strategy to reduce Campylobacter colonization in broilers, as mentioned previously. Furthermore, although no commercial phage preparation is currently available for the biocontrol of Campylobacter in foods, some studies have also reported the efficacy of campylophages as a post-slaughter biocontrol strategy to reduce Campylobacter counts in different poultry products (Table 3) without affecting the remaining microbiota [33]. Three studies found a reduction of around one log in C. jejuni loads when artificially contaminated chicken skin samples were treated with phages and stored in refrigerated conditions (4–5 °C) [26,94,95]. The use of a high multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 103 has been suggested as the best approach to reduce Campylobacter load with no development of phage-resistant Campylobacter mutants [26].

The combination of phage treatment and freezing was shown to cause a further Campylobacter reduction of up to 2.5 log in chicken skin [26]. Under refrigerated temperatures, phage treatment was effective as a function of the campylophage receptor [95]: group II campylophages, which reversibly bind to host flagella, resulted to be unsuitable for Campylobacter biocontrol. Therefore, although the application of cocktails including both group II and III campylophages has been suggested to reduce Campylobacter colonization in broilers (Section 2.1), the use of only group III campylophage cocktails was proposed to successfully combat Campylobacter through post-harvest application [95]. While some authors reported negligible Campylobacter reduction in contaminated chicken meat [96], other researchers achieved a reduction of more than 1.5 log in raw and cooked beef [97] and chicken meat [98] after refrigerated storage for 1 and 2 days, respectively.

The ability of campylophages to reduce Campylobacter counts from chicken carcasses or food products may represent a promising approach to eliminating the risk of contamination from a finished product. Furthermore, the application of Campylobacter-specific phages could also provide an innovative alternative for surface sanitizing to reduce biofilms on food contact surfaces [33,99].

Table 3.

Examples of the effectiveness of phage biocontrol of target foodborne pathogens on different food products.

Table 3.

Examples of the effectiveness of phage biocontrol of target foodborne pathogens on different food products.

| Food | Bacteria Load 1 | Phage | Application MOI * and Method | Result/Bacterial Reduction | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Campylobacter spp. | |||||

| Chicken skin | C. jejuni PT14 4 and 6 log | ϕ2: NCTC12674 GIII | MOI: 0.01–1 MOI: 10–103 spread on surface | Negligible reduction 1 log reduction after 30 min, 3 d and 5 d at 4 °C 2.5 log reduction after 5 d at −20 °C | [26] |

| Chicken skin | C. jejuni C222 4 log | NCTC12673 GIII | MOI: 102 spread on surface | 1 log reduction after 1 d at 4 °C | [94] |

| Chicken neck skin | C. jejuni NCTC12662 4 log | F356GIII F357 GIII F379 GIII Cocktail (2): F356 GIII F357 GIII | MOI: 103 spread on surface | 0.5 log reduction at 5 °C 0.5 log reduction at 5 °C Negligible reduction at 5 °C 0.7 log reduction after 1 d at 5 °C | [95] |

| Chicken meat | C. coli NCTC 126683 C. jejuni NCTC 11168 3 log | NCTC12684 GII CP81 GIII | MOI: 104 spread on surface | No reduction at 4 °C No reduction at 4 °C | [96] |

| Raw and cooked beef | C. jejuni 4 log | Cj6 | MOI: 104 spread on surface | 1.5 and 2 log reduction after 1 d at 5 °C in raw and cooked beef, respectively | [97] |

| Chicken meat | C. jejuni 4 log | CJ01 | MOI: 102 spread on surface | 1.7 log reduction after 2 d at 4 °C | [98] |

| Salmonella spp. | |||||

| Commercial broiler and turkey carcasses | S. Enteritidis (PT 13A) 20 CFU S. Enteritidis (PT 13A) 31 CFU S. Enteritidis host S. Enteritidis field (S9, S14) | PHL 4 72 wild-type phages | Broiler carcasses: MOI: 104 to 1010 spray Turkey carcasses: MOI: 106 to 108 rinsed | 50–100% reduction 60% reduction | [100] |

| Breast and eggs | S. Enteritidis LK5, UA1894 Breast: 106 Eggs: 107 | UAB_Phi 20 UAB_Phi78 UAB_Phi87 | 109 PFU (MOI: 103) rinse 1010 (MOI:103) spray | 2.0 log reduction 0.9 log reduction | [101] |

| Liquid eggs and chicken meat | S. Enteritidis Liquid eggs: 104 Chicken meat: 105 | SE07 | 1011 (MOI 107) Direct addition of 100 mL 1012 (MOI 107) spray | 2 log reduction after 12, 24, and 48 h 2 log reduction after 12, 24, and 48 h | [102] |

| Breast samples | S. Enteritidis ATCC13076 CVCC2184 4 × 105 | PA13076 PC2184 | Single phage: 4 × 109 (MOI: 104) Cocktail: 4 × 109 (MOI: 104) | 2 log reduction Phage PC2184 better than phage PA13076 at 4 °C and 25 °C 2 log reduction | [103] |

| Chicken breast | S. Typhimurium ATCC 14,028 S. Enteritidis ATCC 4931 S. Heidelberg ATCC 8326 3 logs | SalmoFresh TM (6 phages) | MOI: 106 spray | 0.7 and 0.9 log reduction on day 0 and 1, at 4 °C 1 log reduction on day 7 with modified atmosphere at 4 °C 0.8, 0.9, and 0.4 log reduction at 0, 4, and 8 h at room temperature, respectively | [104] |

| Chicken and turkey meat | S. Enteritidis ATCC 13,076 S. Typhimurium ATCC 6539 S. Heidelberg ATCC 8326 1.5 × 103 1.25 × 103 | SalmoLyse® | 2 × 106, 4 × 106, 9 × 106 MOI: 2 × 103, 3 × 103, 6 × 103 spray 9 × 106 and 2 × 107 MOI: 7 × 103, 1 × 104 spray | 60%, 71%, and 88% reduction from chicken meat at 2 × 106, 4 × 106, 9 × 106 PFU/mL, respectively 68% and 86% reduction from turkey meat at 106 and 107 PFU/g, respectively | [105] |

| Chicken meat | S. Typhimurium JCW-3001 S. Enteritidis VDL-133 S. Dublin SP-598 5 log | SalmoFREE® (6 phages) | 108, 109 (MOI: 103, 104) immersion | 1.9–2.0 log reduction in combination with plant-based essential oils | [106] |

| Chicken meat | S. Enteritidis 104 | PhageGuard S® (2 phages) | 107 (MOI: 103) immersion | 1.5 log reduction after 24 h | [107] |

| Listeria monocytogenes | |||||

| Raw salmon | 4 log 2 log | Listex™ P100 | MOI: 1, 10, 102, 103, 104 spread on surface MOI: 106 spread on surface | Marginal reductions at lower MOIs, but up to 3 log reduction at higher MOIs 1.4 log reduction (1 d) No regrowth after 10 d at 4 °C | [108] |

| Raw hake Raw salmon Smoked salmon | 3 log | Listex™ P100 | Automated spray MOI: 104 | 1.2 and 2.0 log reduction after 1 d and 7 d at 4°C (hake) 0.8 and 1.0 log reduction after 1 d and 7 d at 4°C (raw salmon) 0.8 and 1.6 log reduction after 1 d and 30 d at 4°C (smoked salmon) | [109] |

| Smoked salmon | 3 log | ListShield™ (6 phages) | MOI: 103 spray | 0.4 and 1 log reduction | [110] |

| RTE chicken breast roll | 2, 4, and 5 log | FWLLm1 | MOI: 105, 103, 102 spread on surface | Rapid 1.5–2.5 log at 5–30 °C. Regrowth prevented over 21 d at higher MOI and 5 °C (vacuum packed) | [111] |

| Cooked turkey and roast beef | 3 log | Listex™ P100 | MOI:104 spread on surface | 1.7 log and 2.1 log, respectively, after 28 d at 4 °C | [112] |

| Sliced cooked ham | 4 log | Listex™ P100 | MOI: 104 spread on surface | Rapid 1 log reduction 2 log reduction after 28 d at 4 °C | [113] |

| Dry-cured ham | 2, 3, 4 log | Listex™ P100 | MOI: 102–106 spread on surface | 2.5 log to undetectable (highest MOI) after 14 d at 4 °C | [114] |

| Milk | 5 log | Monophages LMP1 and LMP7 | MOI:10 addition to milk | 0.5–3.3 log at 4 °C | [115] |

| “Queso fresco” cheese | 4 log | Listex™ P100 | MOI: 104 spread on surface | 2 log reduction | [116] |

| Soft cheeses | 3 log 1, 2 log | A511 | MOI: 105 in the smearing solution MOI: 106, 107 | 2.5–3 log reduction during the 21 d ripening period >6 log reduction (below the limit of detection) | [117] |

| Hard cheese | 4 log | ListShield™ (6 phages) | MOI: 104 spray | 0.7 log reduction | [110] |

| Lettuce Apple slices | 3 log 4 log | ListShield™ (6 phages) | MOI: 104, 105 spray MOI: 102 spray | 1.1 log reduction at higher MOI 1 log reduction | [110] |

| Fresh-cut apple and melon | 5.5 log | Cocktail (12 phages) LM-103 Cocktail (6 phages) LMP-102 | MOI: 102 spray | Below 0.4 log reduction in apple 2.0–4.6 log reduction in melon | [118] |

| Fresh-cut apple, pear, and melon slices. Apple, pear, and melon juices | 5 log 5 log | Listex™ P100 | MOI: 103 spread on surface MOI: 103 addition to juice | None, 0.6, and 1.5 log reduction in apple, pear, and melon slices after 8 d at 10 °C None, 2, and 8 log reduction in apple, pear, and melon juices after 8 d at 10 °C | [119] |

| Celery and enoki mushroom | 5 log | Mix of 3 phages: LMPC01 LMPC02 LMPC03 | MOI: 10 | 2.2 and 1.8 log reduction in celery and enoki mushroom after 7 d at 4 °C | [120] |

| Vibriospp. | |||||

| Oysters Crassostrea gigas | V. parahaemolyticus CRS 09-17, AMR* 1.6 × 106 CFU in each oyster | pVp-1 | 2 × 107 PFU/oyster (MOI: 10) surface of flesh | 6 log CFU/mL growth reduction after 12 h | [80] |

| Fresh fish flesh | V. parahaemolyticus FORC_023 3 × 104 | VPG01 | MOI: 1 MOI: 10 surface direct application | 1 log reduction (MOI: 1) Counts under the detection limit after 6 h (MOI: 10) | [81] |

| Cutting board | V. parahaemolyticus FORC_023 3 × 104 CFU/cm2 | VPG01 | MOI: 103 surface direct application | 3 log reduction in utensil surface | [81] |

| Raw fish flesh slices | V. parahaemolyticus FORC_023 3 × 104 | VPT02 | MOI of 0, 1, or 10 surface direct application | 2 log reduction after 6 h at 25 °C (MOI: 10) | [121] |

| Shrimp | V. parahaemolyticus F23 | F23s1 Recombinant endolysin ORF52 | MOI: 103 in vitro 20 µmol/L | Growth inhibition at 25 °C for 12 h Decreased OD600 after 60 min The endolysin also showed lytic activity against a panel of 23 drug-resistant V. parahaemolyticus | [122] |

| Manila clams | V. parahaemolyticus Vp-KF4 1 × 104 | Vpp2 | MOI of 1, 10, or 100 | 2.1 log reduction at 25 °C until 24 h No effect of treatment at 4 °C | [123] |

| Oysters | V. parahaemolyticus ATCC 17802) 104 | vB_VpaS_OMN | MOI: 103 surface direct application | 1 log and 2 log reduction after 48 and 72 h of incubation, respectively | [124] |

| Oysters | V. vulnificus 106 | Phage pool (9 phages): S1, P3, P38, P53, P65, P68, P108, P111, P147 | Unknown | 5 log reduction after 18 h of incubation at 4 °C | [125] |

| Abalone flesh | V. vulnificus MO6-24/O 2 × 103 | VVP001 | MOI: 105 MOI: 106 | 2.06 log reduction 2.51 log reduction | [126] |

1 Content in food (CFU/g or mL, unless specified); * MOI (multiplicity of infection: ratio between bacteriophage and bacterial load).

3.2. Salmonella

Many Salmonella species have in common the ability to form biofilms, which are being considered as a factor to explain the extreme persistence of Salmonella in food-processing environments. Consequently, although the food industry has evolved in recent decades, the risk of contamination during food processing remains high. Due to the implication of Salmonella on FBO, the interest in phage biocontrol has increased in the last year as a new method of microbiological control applicable to food pathogens. In this regard, phages have been postulated as an alternative that could be applied directly to food or during food production as disinfectants, due to their stability under abiotic conditions, null toxicity, and selectivity in antimicrobial activity [127].

Different approaches (Table 3) have been used to assess phage success in controlling Salmonella biofilms in foodstuff [128,129]. Phages have also been applied to food as a natural preservative to treat chicken carcasses against Salmonella that is non-recoverable after phage application, resulting in the elimination of the pathogen [59,94]. In the same way, Salmonella contamination from broiler and turkey carcasses rinses was reduced by 100% and 60%, respectively [100]. In addition, a reduction of 2.0 logs of S. Enteritidis in packaged chicken breast after treatment with a cocktail of phages was observed, and a reduction of 0.9 logs was reached in egg samples after phage treatment [101]. Another work assessed the effect of one phage against S. Enteritidis on different matrices, such as eggs and chicken meat. After 12 h of treatment, reductions of 1.79 log CFU/mL and 1.83 log CFU/mL were achieved, respectively [102]. In breast samples, a reduction of 2 log CFU/mL in the Salmonella contamination was observed after the application of 2 different bacteriophages [103]. In addition, several commercial phages against Salmonella for the poultry industry are available, showing promising results in Salmonella biocontrol [104,105,106,107]. In one of the studied cases, phage treatment was the most effective, in comparison with peracetic acid and cetylpyridinium chloride, in controlling Salmonella in chicken breast fillets under room temperature conditions [104].

3.3. Listeria Monocytogenes

Despite the low incidence of listeriosis, its high fatality rate makes it the most frequent cause of foodborne infection-related deaths [28,130]. The main route of human infection is the consumption of contaminated food and, specially, ready-to-eat (RTE) food products that do not require further cooking between production and consumption [28]. The extraordinary capabilities of L. monocytogenes to survive and grow in a wide range of temperatures, pH levels, acidic solutions, and salt concentrations [131,132,133], as well as its ability to form biofilms [134,135], make it very challenging to remove from processing facilities, equipment, and environments [136].

Phage biocontrol shows great potential to be used as a safety control approach at the post-harvest stage of food production, in order to reduce the occurrence of L. monocytogenes in both the food-processing environment and the final food product (Table 3). Although few virulent Listeria-specific phages with potential for biocontrol have been characterized [137,138,139], some of them can infect not only the major L. monocytogenes serotypes, but also other species within the Listeria genus.

Several studies have assessed the effectiveness of commercial products (Phage Guard Listex™ P100 by Micreos B.V., and ListShield™ by Intralytix) and other Listeria-specific phages to control this pathogen in contaminated food products, with variable success. Treatment effectiveness is mainly influenced by the MOI ratio, i.e., the ratio between phage dose and Listeria load. High concentration of phages allowing treatments at high MOI ratios ensure successful contact between phages and their hosts, leading to a more efficient reduction in L. monocytogenes on RTE chicken breast roll [111], dry cured ham [114], raw salmon [108], soft cheeses [117], and lettuce [110]. More successful treatments were observed when phage application occurred during or directly after product contamination [118] and under refrigerated post-treatment storage conditions [112,114,120].

It has been observed that Listeria reduction was more effective in fruit juices, where phages can diffuse until they meet their host, than in fruit slices, where phages are immobilized and cannot contact their hosts through limited diffusion [119]. Similarly, more important reductions were obtained in melon products (slices and juice; pH 5.8 ± 0.1) than in pear products (pH 4.7 ± 0.2), suggesting that pH could be also a key factor contributing to phage effectiveness [119]. These results indicated that, as suggested by other studies, food-related factors, such as physical form, pH, food composition, and/or the presence of specific compounds or substances, may interact with receptors or cell surfaces and interfere with phage diffusion, receptor recognition, and/or binding [115,140].

The intrinsic properties (e.g., lytic spectra, stability, etc.) of the different Listeria-specific phages directly affect treatment effectiveness. Better reduction was found on sliced apples after treatment with the cocktail Listshield [110] than with single phages [119], suggesting that the use of phage cocktails may contribute to better results [110]. Different reduction levels were also found after the application of different cocktails [118] and as a function of the target L. monocytogenes strain [115,141], underlying the importance of the lytic spectra of selected phages. Enhanced effectiveness of Listeria-specific phages has been reported when used in combination with other antimicrobials (e.g., bacteriocins or protective cultures) [108,109,112,113,116]. The application of phages as an innovative approach to eradicate L. monocytogenes biofilms in food processing environments and contact surfaces is another huge challenge that is currently being explored [120,140,142].

Overall, Listeria-specific bacteriophages and their cocktails could contribute, as an additional tool, to a multi-hurdle approach in order to safely reduce the occurrence and growth of L. monocytogenes in food products and food processing environments.

3.4. Human Pathogenic Vibrio spp.

Vibrio spp. are natural hosts in marine waters, and, consequently, are also naturally present in seafood. V. parahaemolyticus constitutes the major causative agent for seafood-borne gastroenteritis by the consumption of contaminated products [81,121]. On the other hand, although less frequent, V. vulnificus is also an opportunistic foodborne pathogen that may cause lethal septicemia [125]. As was previously mentioned, Vibrio infections are being controlled as emerging foodborne agents worldwide, and AMR is also increasing. Consequently, the need for alternative pathogen-control tools has become an urgent necessity. As in the case of Campylobacter, there are no commercial solutions for controlling Vibrio spp. yet. However, in recent years, research into this kind of solution has increased, according to the emergence of Vibrio FBO. There are many works focused on the development and application of phages, especially on V. parahaemolyticus control (Table 3).

For instance, the pVp-1 phage achieved a reduction of 6 log against a pandemic multidrug-resistant V. parahaemolyticus strain (CRS 09-17) when oysters were directly treated on their surfaces [80]. Other works have also reported an interesting effectivity when attempting to reduce V. parahaemolyticus counts in seafood products. Phage VPT02 showed about a 2 log drop in V. parahaemolyticus in raw fish flesh slices [121]. Similarly, the phages Vpp2 and OMN achieved reductions of about 2 logs in Manila clams and oysters, respectively [123,124]. Although more limited, the phages VPG01 and F23s1 have also demonstrated their capability, in solutions, to control the growth of V. parahaemolyticus in fresh fish and shrimps [81,122].

Regarding V. vulnificus, similarly, a phage cocktail has been also applied to reduce the load of V. vulnificus in eastern oysters from 106 to 101 CFU/mL [125]. A more recent study concluded that the VVP001 phage may be used to control V. vulnificus in a broad range of temperatures, ranging from −20 °C to 65 °C, showing a reduction of up to 2.51 logs of bacteria on abalone flesh [126].

These works have demonstrated that phages exhibit great potential as natural food preservatives for the biocontrol of potential Vibrio infections, as well as the prevention of contamination in diverse seafood-related circumstances, such as the storage and depuration steps of seafood [80] and the disinfection of seafood-processing equipment or utensils to prevent cross-contaminations [81].

4. Challenges of Using Phages for Food Safety

The use of phages as biocontrol tools has been gaining interest as a safety strategy in recent decades due to the emergence of AMR bacteria and the subsequent limited use of antibiotics in livestock and crops [143], thus remaining an interesting and natural alternative to combat bacteria. In terms of food safety, applications and advantages of phages have been already summarized in previous sections. However, although the results of the published studies appear to be promising, there are still some limitations that need to be addressed before their generalized use. To assist future phage-based real applications, pending issues and main challenges to be addressed shortly in future investigations are also reflected (Table 4).

The high specificity of phages, their ability to overcome resistance, and their self-dosage can be both strengths and weaknesses. Phage specificity is a major issue for their effectivity as antimicrobials in biocontrol. Host tropism is mostly dependent on receptors based in the cell walls or bacterial capsules. In this situation, building a collection of phages or biobanks to confront most of pathogenic bacteria strains could be a huge and time-consuming undertaking and, depending on the species, direct hunting could be both faster and costless. Interestingly, biobanks could allow ready-to-use phages to be available that can recognize and lyse a battery of bacteria. However, this requires performing phagograms to quickly select the potential phages to be used. This process, known as “phage matching”, could be easily performed with automated equipment, although is not common and the delay in determining the specific phage could be a problem. However, phage biocontrol can be effectively achieved as a customized treatment, which requires prior knowledge of the bacterial host and, most likely, phage hunting to select an efficient phage to control the target bacterium. Additionally, phages can be used as broad-range products by designing proper phage cocktails encompassing broad-range phages. Phage training (experimental evolution) or engineered phages could also help to broaden the host range and to obtain chimeric phages that could recognize multiple strains or species, although this may be detrimental to commensals. However, in food safety, and especially in the food industry, disinfectants to reduce bacterial burden are welcome, and phage-based products, including using phage-derived enzymes to eliminate bacterial biofilms, might be a promising solution as well. Indeed, phages encode several proteins with hydrolytic activity that can actively destroy the bacterial matrix composed of polysaccharide substances and can disrupt biofilms very effectively [144].

Table 4.

Challenges and possible responses to resolve specific issues with using phages.

Table 4.

Challenges and possible responses to resolve specific issues with using phages.

| Challenge | Causes and/or Future Studies Needs | Refs. |

|---|---|---|

| Extreme host specificity |

| [144,145] |

| Potential development of phage resistance |

| [145,146,147] |

| Phage stability and administration routes |

| [148,149,150,151] |

| Mobilization of resistant genes between bacteria |

| [152,153] |

| Phage biobanking for immediate trials |

| [154] |

| Legislative approval |

| [155,156] |

| Consumer acceptance |

| [89] |

Another drawback of some phages is that they might be intrinsically unstable; therefore, some phage-based products might require some procedures to be followed to maintain their stability and, thus, their infectivity. Embedding phages within a material, such as nanoparticles, has been proposed to control phage release and targeted delivery, and could be useful for long-term storage and provision of commercial products that could be stable at different conditions [148]. In addition, other preservation methods, such as freeze-drying, could be another option for long-term storage of phages; they are much cheaper, making them an interesting solution for the industry. However, some phages are not able to maintain infectivity after processing, and encapsulation could be the preferred solution for food protection [149,150]. In this context, it is important to study the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of phages in the environment and in animals, in order to ensure their stability and potential immune responses. Additional in vivo assays are required to ensure the safety and efficacy of the phage biocontrol. In this view, phage administration routes and procedures should be deeply investigated to determine the outcome of the therapy [151].

Another point to be addressed is that phages can mobilize genetic material encoding resistant genes between strains, thus promoting the spread of AMR, including to non-pathogenic bacteria. Although phages are evolving entities in nature, and this transfer could certainly occur in their natural environment, for biocontrol purposes, lytic and perfectly characterized (sequenced) phages are always preferred to reduce potential gene transfer [152]. In addition, detailed analysis of each phage genome must be performed, as it provides useful information for the selection of the most suitable phages. In addition, understanding phage–host interactions will be of special interest to anticipate potential failure treatments, such as the emergence of phage-resistant bacteria. Interestingly, phages can overcome resistance, adapting to the new environment faster than their hosts. In addition, phage cocktails can be a solution to reduce the emergence of phage resistance [153].

Finally, to be used, any phage application must be in compliance with legislation. Nevertheless, the great variability of phage morphologies and diversity, their intrinsic evolving, and their self-replication nature in the presence of the bacterial host create a challenge for regulatory agencies due to their intrinsic evolvability [155], and highlight the problem of subjecting all phage-derived products to the same regulation and procedures. As seen, legislation on the use of phages is a complicated issue and will delay commercialization and routine use of this promising virus. However, regulatory agencies should provide rapid guidance on phage biocontrol to address the emergence of resistant bacteria, since an alternative to antibiotics is necessary [157].

5. Conclusions

Although it is clear that no therapeutic or preventive treatment can or should replace good hygiene practices in food production, progressively, more studies have demonstrated that phage application can be a leading approach to controlling important foodborne diseases. Considering their natural properties and advantages, phages can be used at all stages of the agriculture supply chain to control microbial pathogens. They can be employed in every step, from agriculture (primary production) to biosanitization of food processing facilities and biopreservation of foodstuffs. Moreover, the aforementioned challenges are expected to be answered as the issue of AMR becomes more pressing. The creation of a legal framework to allow different applications of phages in reality, including in food safety, is an especially pressing issue.

Author Contributions

All authors have substantially contributed to the writing and reviewing of this work. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

M.L. and A.L. acknowledge the financial support by CDTI (Spain), under the Programa para Centros Tecnológicos de Excelencia “Cervera” 2020, grant number Exp. CER-20211010. P.D.-C. was financially supported by a Ramón y Cajal contract RYC2019-028015-I and project PID2020-112835RA-I00, funded by MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033, ESF Invest in your future. S.S.-N. acknowledge the financial support by Generalitat Valenciana—Fondo Social Europeo (CIGE/2021/143).

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Endersen, L.; O’Mahony, J.; Hill, C.; Ross, R.P.; McAuliffe, O.; Coffey, A. Phage Therapy in the Food Industry. Ann. Rev. Food Sci. Technol. 2014, 5, 327–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousavi, S.L.; Rasooli, I.; Nazarian, S.; Amani, J. Simultaneous detection of Escherichia coli O157:H7, toxigenic Vibrio cholerae, and Salmonella typhimurium by multiplex PCR. Iran. J. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2009, 4, 97–103. [Google Scholar]

- Gould, L.H.; Seys, S.; Everstine, K.; Norton, D.; Ripley, D.; Reimann, D.; Dreyfuss, M.; Chen, W.S.; Selman, C.A. Recordkeeping Practices of Beef Grinding Activities at Retail Establishments. J. Food Prot. 2011, 74, 1022–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lynch, M.; Tauxe, R.; Hednerg, C. The growing burden of foodborne outbreaks due to contaminated fresh produce: Risks and opportunities. Epidemiol. Infect. 2009, 137, 307–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, S.L.; Lee, H.Y.; Mahyudin, N.A. Antimicrobial resistance of Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus isolated from food handler’s hands. Food Control 2014, 44, 203–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO; FAO; OIE. Taking a Multisectoral, One Health Approach: A Tripartite Guide to Addressing Zoonotic Diseases in Countries. 2019. Available online: https://www.woah.org/app/uploads/2021/03/en-tripartitezoonosesguide-webversion.pdf (accessed on 3 August 2022).

- Gordillo-Altamirano, F.L.; Barr, J.J. Phage therapy in the postantibiotic era. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2019, 32, e00066-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neil, J. Antimicrobial Resistance: Tackling a Crisis for the Health and Wealth of Nations. UK, 2014. Available online: https://amr-review.org (accessed on 29 July 2022).

- Jamal, M.; Bukhari, S.M.A.U.S.; Andleeb, S.; Ali, M.; Raza, S.; Nawaz, M.A.; Hussain, T.; Rahman, S.U.; Shah, S.S.A. Bacteriophages: An overview of the control strategies against multiple bacterial infections in different fields. J. Basic Microbiol. 2019, 59, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagel, T.E.; Chan, B.K.; De Vos, D.; El-Shibiny, A.; Kang’ethe, E.K.; Makumi, A.; Pirnay, J.-P. The Developing World Urgently Needs Phages to Combat Pathogenic Bacteria. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moye, Z.D.; Woolston, J.; Sulakvelidze, A. Bacteriophage applications for food production and processing. Viruses 2018, 10, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Sullivan, L.; Bolton, D.; McAuliffe, O.; Coffey, A. Bacteriophages in food applications: From foe to friend. Annu. Rev. Food Technol. 2019, 15, 151–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, I.; Wang, I.; Roof, W.D. Phages will out: Strategies of host cell lysis. Trends Microbiol. 2000, 8, 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernhardt, T.G.; Wang, I.N.; Struck, D.K.; Young, R. Breaking free: “protein antibiotics” and phage lysis. Res. Microbiol. 2002, 153, 493–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vikram, A.; Woolston, J.; Sulakvelidze, A. Phage Biocontrol Applications in Food Production and Processing. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2021, 40, 267–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pirnay, J.P.; Merabishvili, M.; Van Raemdonck, H.; DeVis, D.; Verbeken, G. Bacteriophage production in compliance with regulatory requirements. In Bacteriophage Therapy: From Lab to Clinical Practice; Azeredo, J., Sillankorva, S., Eds.; Humana Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017; Book Series: Methods in Molecular Biology; Volume 1693, pp. 233–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alomari, M.M.M.; Dec, M.; Urban-Chmiel, R. Bacteriophages as an Alternative Method for Control of Zoonotic and Foodborne Pathogens. Viruses 2021, 13, 2348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutateladze, M.; Adamia, R. Bacteriophages as potential new therapeutics to replace or supplement antibiotics. Trends Biotechnol. 2010, 28, 591–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schooley, R.T.; Biswas, B.; Gill, J.J.; Hernandez-Morales, A.; Lancaster, J.; Lessor, L.; Barr, J.J.; Reed, S.L.; Rohwer, F.; Benler, S.; et al. Development and use of personalized bacteriophage-based therapeutic cocktails to treat a patient with a disseminated resistant Acinetobacter baumannii Infection. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2017, 61, e00954-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doss, J.; Culbertson, K.; Hahn, D.; Camacho, J.; Barekzi, N. A Review of Phage Therapy against Bacterial Pathogens of Aquatic and Terrestrial Organisms. Viruses 2017, 9, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodridge, L.D.; Bisha, B. Phage-based biocontrol strategies to reduce foodborne pathogens in foods. Bacteriophage 2011, 1, 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sillankorva, S.M.; Oliveira, H.; Azeredo, J. Bacteriophages and their role in food safety. Inter. J. Microbiol 2012, 12, 863945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosimann, S.; Desiree, K.; Ebner, P. Efficacy of Phage Therapy in Poultry: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Poult. Sci. 2021, 100, 101472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Summers, W.C. Bacteriophage therapy. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2001, 55, 437–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, J.R.; March, J.B. Bacteriophages and biotechnology: Vaccines, gene therapy and antibacterials. Trends Biotechnol. 2006, 24, 212–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atterbury, R.J.; Connerton, P.L.; Dodd, C.E.; Rees, C.E.; Connerton, I.F. Application of host specific bacteriophages to the surface of chicken skin leads to a reduction in recovery of Campylobacter jejuni. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2003, 69, 6302–6306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bueno, E.; García, P.; Martínez, B.; Rodríguez, A. Phage inactivation of Staphylococcus aureus in fresh and hard-type cheeses. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2012, 158, 23–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EFSA; ECDC. The European Union One Health 2021 Zoonoses Report. EFSA J. 2022, 20, 7666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevilla-Navarro, S.; Catalá-Gregori, P.; Marin, C. Salmonella Bacteriophage Diversity According to Most Prevalent Salmonella Serovars in Layer and Broiler Poultry Farms from Eastern Spain. Animals 2020, 10, 1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sifre, E.; Salha, B.A.; Ducournau, A.; Floch, P.; Chardon, H.; Megraud, F.; Lehours, P. EUCAST recommendations for antimicrobial susceptibility testing applied to the three main Campylobacter species isolated in humans. J. Microbiol. Methods 2015, 119, 206–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaakoush, N.O.; Castano-Rodriguez, N.; Mitchell, H.M.; Man, S.M. Global epidemiology of Campylobacter infection. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2015, 28, 687–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Global Priority List of Antibiotic Resistant Bacteria to Guide Research, Discovery, and Development of New Antibiotics. 2017. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/27-02-2017-who-publishes-list-of-bacteria-for-which-new-antibiotics-are-urgently-needed (accessed on 29 July 2022).

- Olson, E.G.; Micciche, A.C.; Rothrock, M.J., Jr.; Yang, Y.; Ricke, S.C. Application of Bacteriophages to Limit Campylobacter in Poultry Production. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 458721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA BIOHAZ Panel (European Food Safety Authority Panel on Biological Hazards). Update and review of control options for Campylobacter in broilers at primary production. EFSA J. 2020, 18, 6090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mota-Gutierrez, J.; Lis, L.; Lasagabaster, A.; Nafarrate, I.; Ferrocino, I.; Cocolin, L.; Rantsiou, K. Campylobacter spp. prevalence and mitigation strategies in the broiler production chain. Food Microbiol. 2022, 104, 103998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nafarrate, I.; Mateo, E.; Miranda, K.; Lasagabaster, A. Isolation, host specificity and genetic characterization of Campylobacter specific bacteriophages from poultry and swine sources. Food Microbiol. 2021, 97, 103742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sails, A.D.; Wareing, D.R.A.; Bolton, F.J.; Fox, A.J.; Curry, A. Characterisation of 16 Campylobacter jejuni and C. coli typing bacteriophages. J. Med. Microbiol. 1998, 47, 123–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Angelantonio, D.; Scattolini, S.; Boni, A.; Neri, D.; Di Serafino, G.; Connerton, P.; Connerton, I.; Pomilio, F.; Di Giannatale, E.; Migliorati, G.; et al. Bacteriophage Therapy to Reduce Colonization of Campylobacter jejuni in Broiler Chickens before Slaughter. Viruses 2021, 13, 1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richards, P.J.; Connerton, P.L.; Connerton, I. Phage Biocontrol of Campylobacter jejuni in Chickens Does Not Produce Collateral Effects on the Gut Microbiota. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loc-Carrillo, C.; Atterbury, R.J.; El Shibiny, A.; Connerton, P.L. Bacteriophage therapy to reduce Campylobacter jejuni colonization of broiler chickens. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2005, 71, 6554–6563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carvalho, C.M.; Gannon, B.W.; Halfhide, D.E.; Santos, S.B.; Hayes, C.M.; Roe, J.M.; Azeredo, J. The in vivo efficacy of two administration routes of a phage cocktail to reduce numbers of Campylobacter coli and Campylobacter jejuni in chickens. BMC Microbiol. 2010, 10, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kittler, S.; Fischer, S.; Abdulmawjood, A.; Glünder, G.; Klein, G. Effect of Bacteriophage Application on Campylobacter jejuni Loads in Commercial Broiler Flocks. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2013, 79, 7525–7533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinivasagam, H.N.; Estella, W.; Maddock, L.; Mayer, D.G.; Weyand, C.; Connerton, P.L.; Connerton, I.F. Bacteriophages to control Campylobacter in commercially farmed broiler chickens in Australia. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagenaar, J.A.; Van Bergen, M.A.; Mueller, M.A.; Wassenaar, T.M.; Carlton, R.M. Phage therapy reduces Campylobacter jejuni colonization in broilers. Veter. Microbiol. 2005, 109, 275–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Shibiny, A.; Scott, A.; Timms, A.; Metawea, Y.; Connerton, P.; Connerton, I. Application of a Group II Campylobacter Bacteriophage To Reduce Strains of Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli Colonizing Broiler Chickens. J. Food Prot. 2009, 72, 733–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammerl, J.A.; Jäckel, C.; Alter, T.; Janzcyk, P.; Stingl, K.; Knüver, M.T.; Hertwig, S. Reduction of Campylobacter jejuni in broiler chicken by successive application of group II and group III phages. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e114785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. Salmonella (Non-Typhoidal). Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/salmonella-(non-typhoidal) (accessed on 11 August 2022).

- Dawoud, T.M.; Davis, M.L.; Park, S.H.; Kim, S.A.; Kwon, Y.M.; Jarvis, N.; O’Bryan, C.A.; Shi, Z.; Crandall, P.G.; Ricke, S.C. The Potential Link between Thermal Resistance and Virulence in Salmonella: A Review. Front. Vet. Sci. 2017, 4, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, S.S.; Jeong, J.; Lee, J.; Kim, S.; Min, W.; Myung, H. Therapeutic Effects of Bacteriophages against Salmonella Gallinarum Infection in Chickens. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2013, 23, 1478–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atterbury, R.J.; van Bergen, M.A.P.; Ortiz, F.; Lovell, M.A.; Harris, J.A.; de Boer, A.; Wagenaar, J.A.; Allen, V.M.; Barrow, P.A. Bacteriophage Therapy to Reduce Salmonella Colonization of Broiler Chickens. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2007, 73, 4543–4549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaz, C.S.L.; Voss-Rech, D.; Alves, L.; Coldebella, A.; Brentano, L.; Trevisol, I.M. Effect of Time of Therapy with Wild-Type Lytic Bacteriophages on the Reduction of Salmonella Enteritidis in Broiler Chickens. Vet. Microbiol. 2020, 240, 108527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreatti, R.L.; Higgins, J.P.; Higgins, S.E.; Gaona, G.; Wolfenden, A.D.; Tellez, G.; Hargis, B.M. Ability of bacteriophages isolated from different sources to reduce Salmonella enterica serovar Enteritidis in vitro and in vivo. Poult. Sci. 2007, 86, 1904–1909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borie, C.; Albala, I.; Sánchez, P.; Sánchez, M.L.; Ramírez, S.; Navarro, C.; Morales, M.A.; Retamales, J.; Robeson, J. Bacteriophage treatment reduces Salmonella colonization of infected chickens. Avian Dis. 2008, 52, 64–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, P.A.; Cosby, D.E.; Cox, N.A.; Lee, J.H.; Kim, W.K. Effect of dietary bacteriophage supplementation on internal organs, fecal excretion, and ileal immune response in laying hens challenged by Salmonella Enteritidis. Poult. Sci. 2017, 96, 3264–3271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevilla-Navarro, S.; Marín, C.; Cortés, V.; García, C.; Vega, S.; Catalá-Gregori, P. Autophage as a control measure for Salmonella in laying hens. Poult. Sci. 2018, 97, 4367–4373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wójcik, E.A.; Stańczyk, M.; Wojtasik, A.; Kowalska, J.D.; Nowakowska, M.; Łukasiak, M.; Bartnicka, M.; Kazimierczak, J.; Dastych, J. Comprehensive Evaluation of the Safety and Efficacy of BAFASAL® Bacteriophage Preparation for the Reduction of Salmonella in the Food Chain. Viruses 2020, 12, 742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EFSA; ECDC. The European Union Summary Report on Antimicrobial Resistance in zoonotic and indicator bacteria from hu-mans, animals and food in 2019–2020. EFSA J. 2022, 20, 7209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Critically Important Antimicrobials for Human Medicine, 6th Revision 2018, Ranking of Medically Important Antimicrobials for Risk Management of Antimicrobial Resistance Due to Non-Human Use. 2018. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/312266/9789241515528-eng.pdf (accessed on 29 July 2022).

- Carvalho, C.; Costa, A.R.; Silva, F.; Oliveira, A. Bacteriophages and Their Derivatives for the Treatment and Control of Food-Producing Animal Infections. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 2017, 43, 583–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nabil, N.M.; Tawakol, M.M.; Hassan, H.M. Assessing the Impact of Bacteriophages in the Treatment of Salmonella in Broiler Chickens. Infect. Ecol. Epidemiol. 2018, 8, 1539056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Żbikowska, K.; Michalczuk, M.; Dolka, B. The Use of Bacteriophages in the Poultry Industry. Animals 2020, 10, 872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, T.-H.; Lee, D.-H.; Lee, Y.-N.; Park, J.-K.; Youn, H.-N.; Kim, M.-S.; Lee, H.-J.; Yang, S.-Y.; Cho, Y.-W.; Lee, J.-B.; et al. Efficacy of Bacteriophage Therapy on Horizontal Transmission of Salmonella Gallinarum on Commercial Layer Chickens. Avian Dis. 2011, 55, 435–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakari, U.M.; Rantala, L.; Pihlajasaari, A.; Toikkanen, S.; Johansson, T.; Hellsten, C.; Raulo, S.M.; Kuusi, M.; Siitonen, A.; Rimhanen-Finne, R. Investigation of increased listeriosis revealed two fishery production plants with persistent Listeria contamination in Finland in 2010. Epidemiol. Infect. 2014, 142, 2261–2269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skowron, K.; Kwiecinska, J.; Grudlewska, K.; Swieca, A.; Paluszak, Z.; Bauza, J.; Wałecka, E.; Gospodarek, E. The occurrence, transmission, virulence and antibiotic resistance of Listeria monocytogenes in fish processing plant. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2018, 282, 71–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morwal, S.; Sharma, S.K. Bacterial zoonosis—A public health importance. J. Dairy Vet. Anim. Res. 2017, 5, 56–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loessner, M.; Carlton, R.M. Virulent Phages to Control Listeria monocytogenes in Foodstuffs and in Food Processing Plants. US Patent US7438901B2, 28 August 2008. Available online: https://patentscope.wipo.int/search/en/detail.jsf?docId=WO2004004495 (accessed on 13 October 2022).

- Li, T.; Zhao, X.; Wang, X.; Wang, Z.; Tian, C.; Shi, W.; Qi, Y.; Wei, H.; Song, C.; Xue, H.; et al. Characterization and Preliminary application of phage isolated from Listeria monocytogenes. Front. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 946814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vezzulli, L.; Grande, C.; Reid, P.C.; Hélaouët, P.; Edwards, M.; Höfle, M.G.; Brettar, I.; Colwell, R.R.; Pruzzo, C. Climate influence on Vibrio and associated human diseases during the past half-century in the coastal North Atlantic. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, E5062–E5071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neetoo, H.; Reega, K.; Manoga, Z.S.; Nazurally, N.; Bhoyroo, V.; Allam, M.; Jaufeerally-Fakim, Y.; Ghoorah, A.W.; Jaumdally, W.; Hossen, A.M.; et al. Prevalence, genomic characterization, and risk assessment of human pathogenic Vibrio Species in Seafood. J. Food Prot. 2022, 85, 1553–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker-Austin, C.; Oliver, J.D.; Alam, M.; Ali, A.; Waldor, M.K.; Qadri, F.; Martinez-Urtaza, J. Vibrio spp. infections. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 2018, 4, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arunkumar, M.; LewisOscar, F.; Thajuddin, N.; Pugazhendhi, A.; Nithya, C. In vitro and in vivo biofilm forming Vibrio spp: A significant threat in aquaculture. Process Biochem. 2020, 94, 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plaza, N.; Castillo, D.; Pérez-Reytor, D.; Higuera, G.; García, K.; Bastías, R. Bacteriophages in the control of pathogenic vibrios. Electron. J. Biotechnol. 2018, 31, 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cascarano, M.C.; Stavrakidis-Zachou, O.; Mladineo, I.; Thompson, K.D.; Papandroulakis, N.; Katharios, P. Mediterranean Aquaculture in a Changing Climate: Temperature Effects on Pathogens and Diseases of Three Farmed Fish Species. Pathogens 2021, 10, 1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, J.; Nelson, K.; Morcrette, H.; Morcrette, C.; Preston, J.; Helmer, L.; Titball, R.W.; Butler, C.S.; Wagley, S. The increased prevalence of Vibrio species and the first reporting of Vibrio jasicida and Vibrio rotiferianus at UK shellfish sites. Water Res. 2022, 211, 117942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarano, C.; Spanu, C.; Ziino, G.; Pedonese, F.; Dalmasso, A.; Spanu, V.; Virdis, S.; De Santis, E.P.L. Antibiotic resistance of Vibrio species isolated from Sparus aurata reared in Italian mariculture. New Microbiol. 2014, 37, 329–337. [Google Scholar]

- Elmahdi, S.; DaSilva, L.V.; Parveen, S. Antibiotic resistance of Vibrio parahaemolyticus and Vibrio vulnificus in various countries: A review. Food Microbiol. 2016, 57, 128–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yano, Y.; Hamano, K.; Satomi, M.; Tsutsui, I.; Ban, M.; Aue-umneoy, D. Prevalence and antimicrobial susceptibility of Vibrio species related to food safety isolated from shrimp cultured at inland ponds in Thailand. Food Control 2014, 38, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. DG Maritime Affairs and Fisheries. Strategic Guidelines for a More Sustainable and Competitive EU Aquaculture for the Period 2021 to 2030; Document 52021DC0236, COM/2021/236 final; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2021.

- Onarinde, B.A.; Dixon, R.A. Prospects for Biocontrol of Vibrio parahaemolyticus Contamination in Blue Mussels (Mytilus edulus)-A Year-Long Study. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jun, J.W.; Kim, H.J.; Yun, S.K.; Chai, J.Y.; Park, S.C. Eating oysters without risk of vibriosis: Application of a bacteriophage against Vibrio parahaemolyticus in oysters. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2014, 188, 31–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H.; Oh, M.; Kim, B.S. Phage biocontrol of zoonotic food-borne pathogen Vibrio parahaemolyticus for seafood safety. Food Control 2023, 144, 109334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinod, M.G.; Shivu, M.M.; Umesha, K.R.; Rajeeva, B.C.; Krohneb, G. Isolation of Vibrio harveyi bacteriophage with a potential for biocontrol of luminous vibriosis in hatchery environments. Aquaculture 2006, 255, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Droubogiannis, S.; Katharios, P. Genomic and biological profile of a novel Vibrio phage, Virtus, which improves survival of Sparus aurata larvae challenged with Vibrio harveyi. Pathogens 2022, 11, 630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higuera, G.; Bastías, R.; Tsertsvadze, G.; Romero, J.; Espejo, R.T. Recently discovered Vibrio anguillarum phages can protect against experimentally induced vibriosis in Atlantic salmon, Salmo salar. Aquaculture 2013, 395, 128–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, Y.J.; Costa, L.; Pereira, C.; Mateus, C.; Cunha, Â.; Calado, R.; Gomes, N.; Pardo, M.A.; Hernandez, I.; Almeida, A. Phage Therapy as an Approach to Prevent Vibrio anguillarum Infections in Fish Larvae Production. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e114197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lomelí-Ortega, C.O.; Martínez-Díaz, S.F. Phage therapy against Vibrio parahaemolyticus infection in the whiteleg shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei) larvae. Aquaculture 2014, 434, 208–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karunasagar, I.; Shivu, M.M.; Girisha, S.K.; Krohne, G.; Karunasagar, I. Biocontrol of pathogens in shrimp hatcheries using bacteriophages. Aquaculture 2007, 268, 288–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakai, T.; Park, S.C. Bacteriophage therapy of infectious diseases in aquaculture. Res. Microbiol. 2002, 153, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasagabaster, A.; Jiménez, E.; Lehnherr, T.; Miranda-Cadena, K.; Lehnherr, H. Bacteriophage biocontrol to fight Listeria outbreaks in seafood. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2020, 145, 111682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sulakvelidze, A. Using lytic bacteriophages to eliminate or significantly reduce contamination of food by foodborne bacterial pathogens. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2013, 93, 3137–3146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolocan, A.S.; Callanan, J.; Forde, A.; Ross, P.; Hill, C. Phage therapy targeting Escherichia coli-a story with no end? FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2016, 363, fnw256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutiérrez, D.; Fernández, L.; Martínez, B.; Ruas-Madiedo, P.; García, P.; Rodríguez, A. Real-Time Assessment of Staphylococcus aureus Biofilm Disruption by Phage-Derived Proteins. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagens, S.; Loessner, M.J. Application of bacteriophages for detection and control of foodborne pathogens. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2007, 76, 513–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goode, D.; Allen, V.M.; Barrow, P.A. Reduction of experimental Salmonella and Campylobacter contamination of chicken skin by application of lytic bacteriophages. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2003, 69, 5032–5036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zampara, A.; Sørensen, M.C.; Elsser-Gravesen, A.; Brøndsted, L. Significance of phage-host interactions for biocontrol of Campylobacter jejuni in food. Food Control 2017, 73, 1169–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orquera, S.; Golz, G.; Hertwig, S.; Hammerl, J.; Sparborth, D.; Joldic, A.; Alter, T. Control of Campylobacter spp. and Yersinia enterocolitica by virulent bacteriophages. J. Mol. Genet. Med. 2012, 6, 273–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigwood, T.; Hudson, J.A.; Billington, C.; Carey-Smith, G.V.; Heinemann, J.A. Phage inactivation of foodborne pathogens on cooked and raw meat. Food Microbiol. 2008, 25, 400–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thung, T.Y.; Lee, E.; Mahyudin, N.A.; Radzi, C.W.J.; Mazlan, N.; Tan, C.W.; Radu, S. Partial characterization and in vitro evaluation of a lytic bacteriophage for biocontrol of Campylobacter jejuni in mutton and chicken meat. J. Food Saf. 2020, 40, e12770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siringan, P.; Connerton, P.L.; Payne, R.J.H.; Connerton, I.F. Bacteriophage-mediated dispersal of Campylobacter jejuni biofilms. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2011, 77, 3320–3326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins, J.P.; Higgins, S.E.; Guenther, K.L.; Huff, W.; Donoghue, A.M.; Donoghue, D.J.; Hargis, B.M. Use of a Specific Bacteriophage Treatment to Reduce Salmonella in Poultry Products. Poult. Sci. 2005, 84, 1141–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spricigo, D.A.; Bardina, C.; Cortés, P.; Llagostera, M. Use of a Bacteriophage Cocktail to Control Salmonella in Food and the Food Industry. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2013, 165, 169–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thung, T.Y.; Krishanthi Jayarukshi Kumari Premarathne, J.M.; San Chang, W.; Loo, Y.Y.; Chin, Y.Z.; Kuan, C.H.; Tan, C.W.; Basri, D.F.; Radzi, C.W.J.W.M.; Radu, S. Use of a Lytic Bacteriophage to Control Salmonella Enteritidis in Retail Food. LWT 2017, 78, 222–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]