Performance Testing of Bacillus cereus Chromogenic Agar Media for Improved Detection in Milk and Other Food Samples

Abstract

:1. Introduction

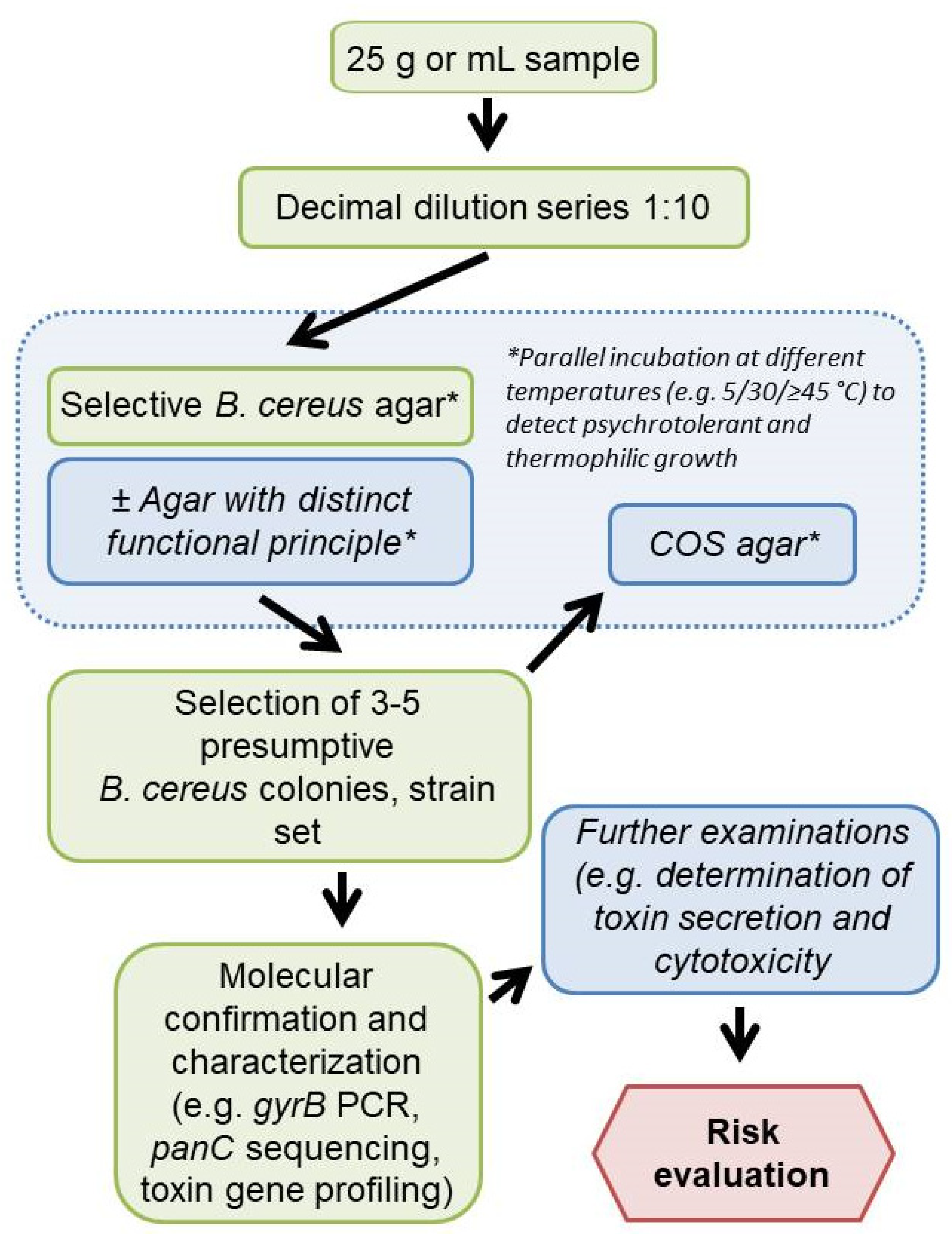

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Performance Testing of Selective Media

2.1.1. Test Media

2.1.2. Inclusivity and Exclusivity Test Strains

2.1.3. Naturally Contaminated Food Samples

2.2. Molecular and Phenotypical Characterization

2.2.1. DNA-Extraction

2.2.2. Confirmation of Group Affiliation

2.2.3. Toxin Gene Screening and Profiling

2.2.4. Partial panC Sequencing

2.2.5. Assessment of Hemolytic Activity

2.3. Evaluation Criteria and Statistics

3. Results

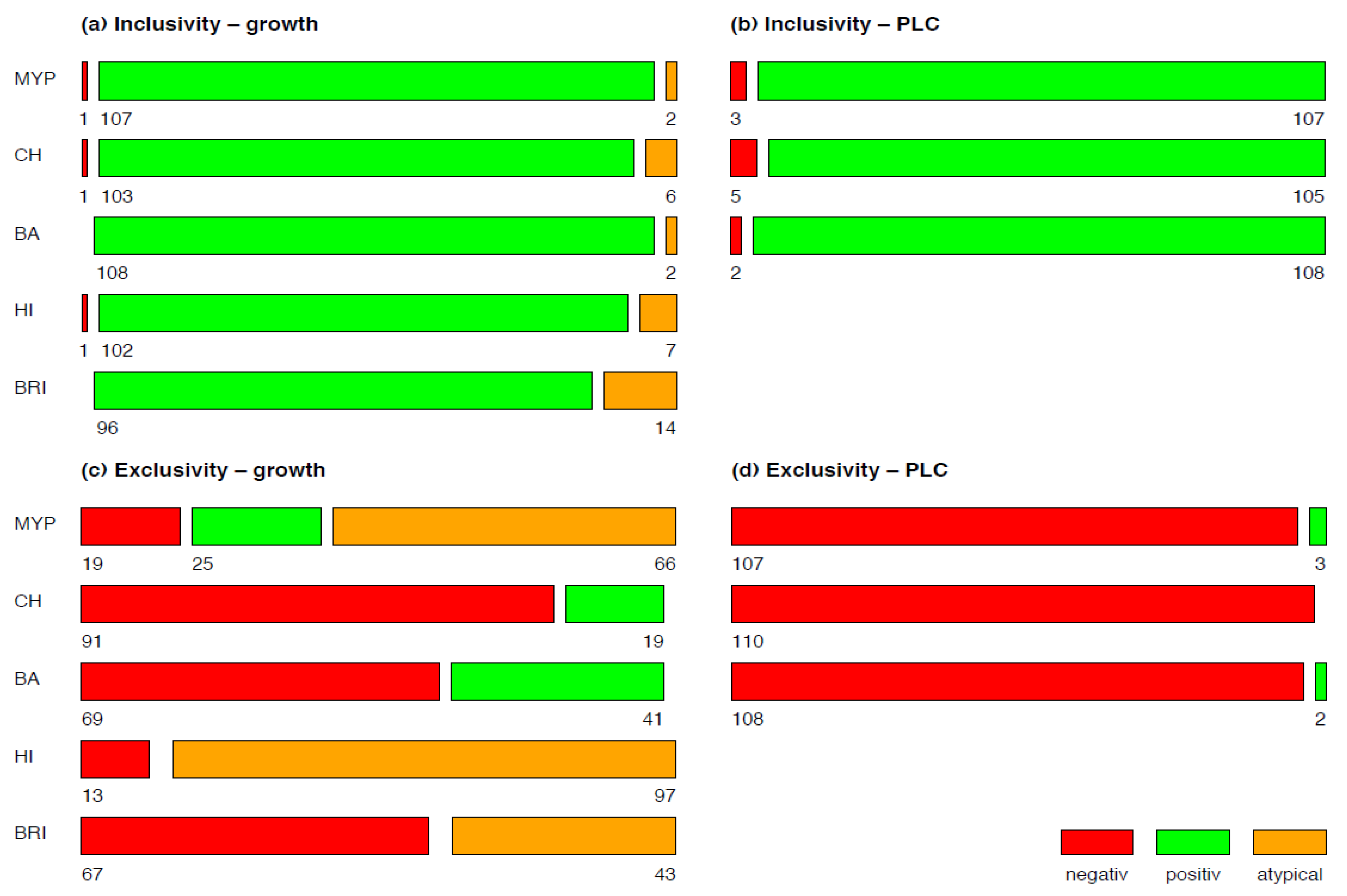

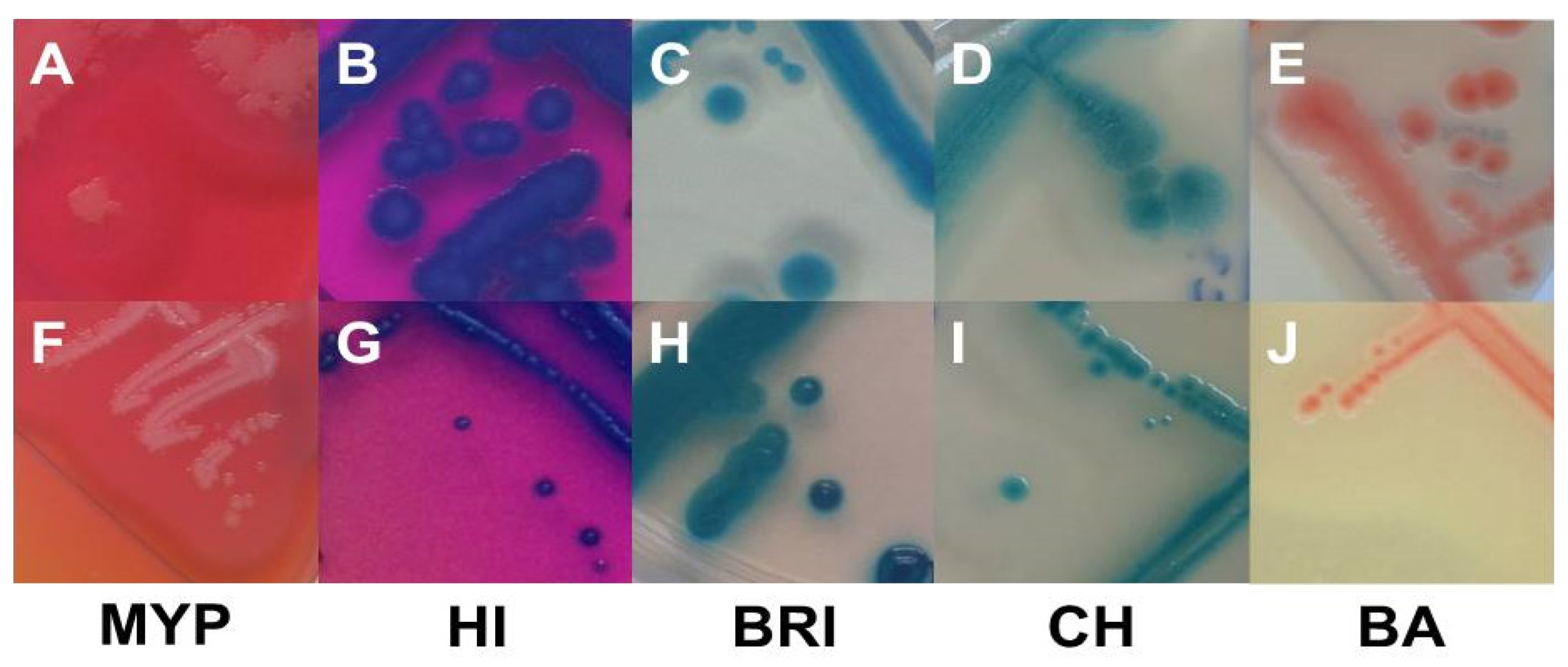

3.1. Inclusivity and Exclusivity Testing

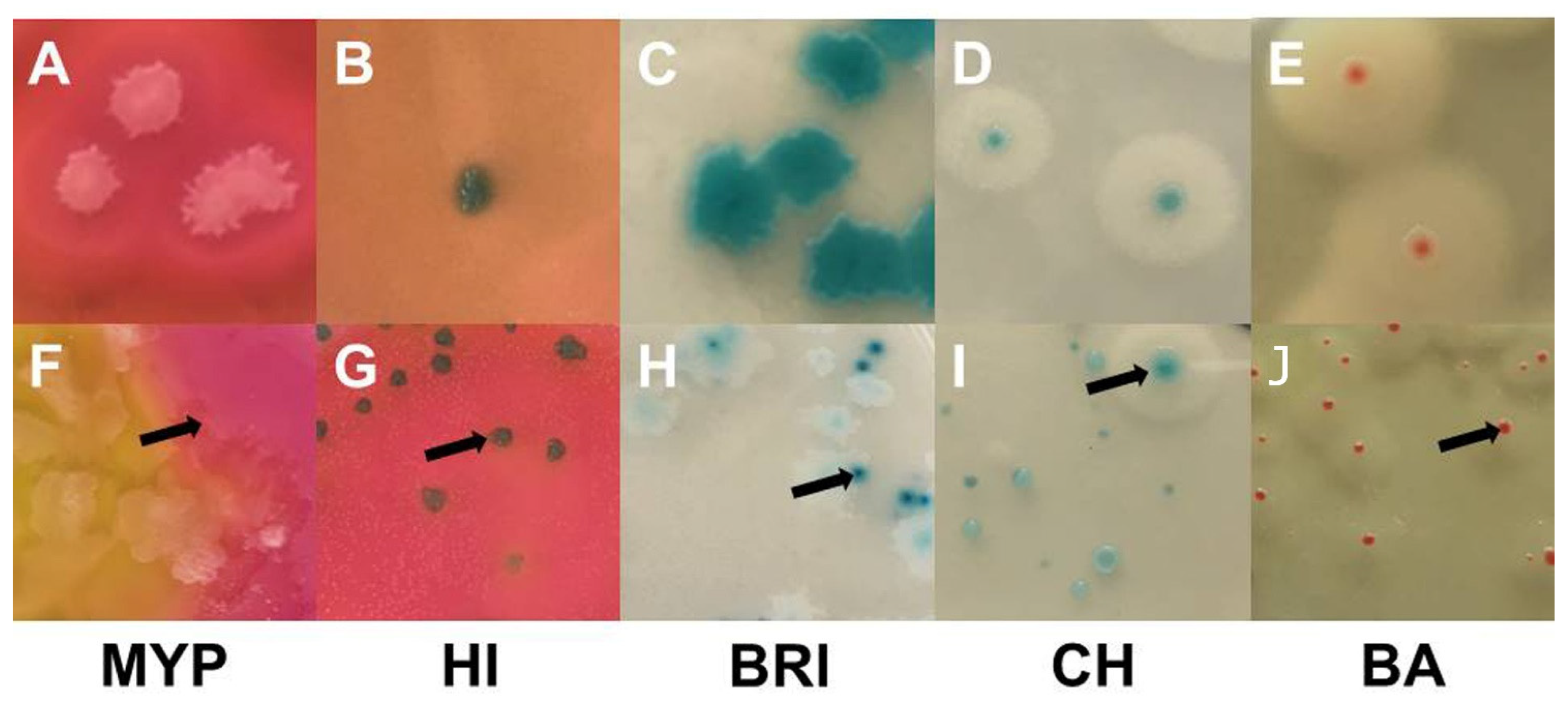

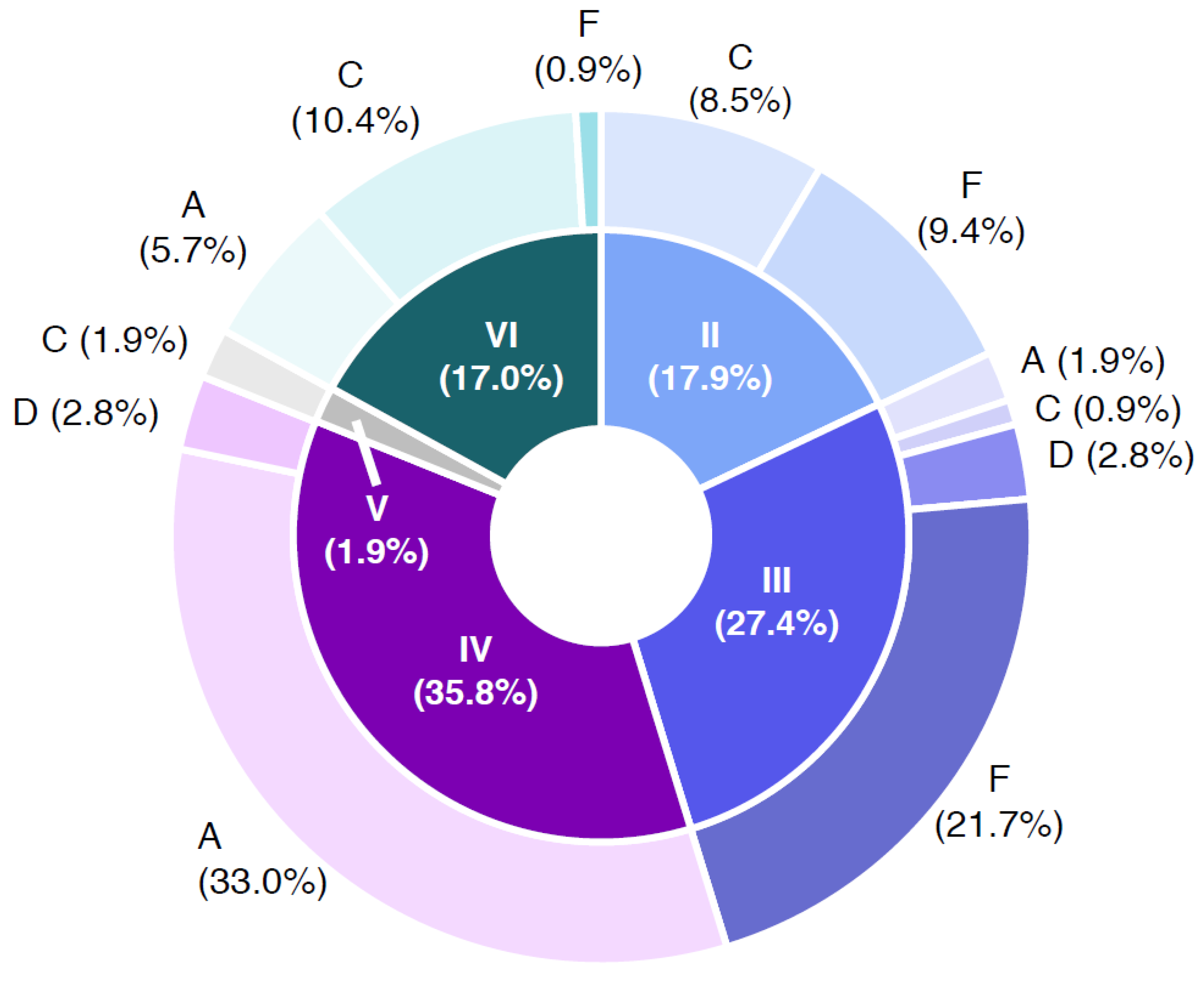

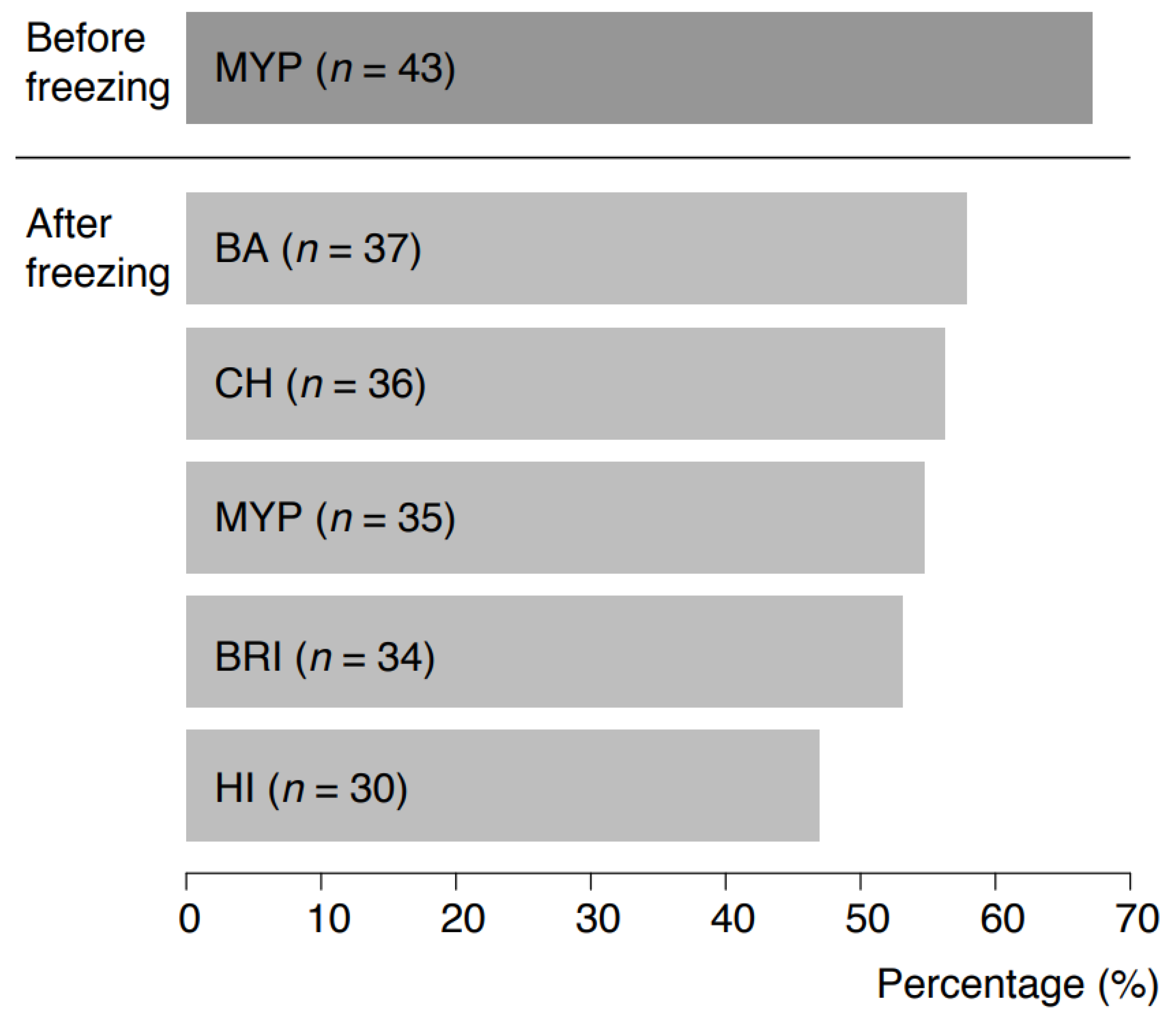

3.2. Naturally Contaminated Samples

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kumari, S.; Sarkar, P.K. Bacillus cereus hazard and control in industrial dairy processing environment. Food Control 2016, 69, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logan, N.A.; De Vos, P. Bacillus. In Bergey’s Manual of Systematics of Archaea and Bacteria; Whitman, W.B., Rainey, F., Kämpfer, P., Trujillo, M., Chun, J., de Vos, P., Hedlund, B., Dedysh, S., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Messelhäußer, U.; Ehling-Schulz, M. Bacillus cereus—A Multifaceted Opportunistic Pathogen. Curr. Clin. Microbiol. Rep. 2018, 5, 120–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ehling-Schulz, M.; Fricker, M.; Scherer, S. Bacillus cereus, the causative agent of an emetic type of food-borne illness. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2004, 48, 479–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehling-Schulz, M.; Lereclus, D.; Koehler, T.M. The Bacillus cereus Group: Bacillus Species with Pathogenic Potential. Microbiol. Spect. 2019, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietrich, R.; Jessberger, N.; Ehling-Schulz, M.; Märtlbauer, E.; Granum, P.E. The Food Poisoning Toxins of Bacillus cereus. Toxins 2021, 13, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lechner, S.; Mayr, R.; Francis, K.P.; Pruess, B.M.; Kaplan, T.; Wießner-Gunkel, E.; Steward, G.S.; Scherer, S. Bacillus weihenstephanensis sp. nov. is a new psychrotolerant species of the Bacillus cereus group. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 1998, 48, 1373–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nakamura, L.K. Bacillus pseudomycoides sp. nov. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 1998, 48, 1031–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Guinebretière, M.H.; Auger, S.; Galleron, N.; Contzen, M.; De Sarrau, B.; De Buyser, M.L.; Lamberet, G.; Fagerlund, A.; Granum, P.E.; Lereclus, D.; et al. Bacillus cytotoxicus sp. nov. is a novel thermotolerant species of the Bacillus cereus Group occasionally associated with food poisoning. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2013, 63, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiménez, G.; Urdiain, M.; Cifuentes, A.; López-López, A.; Blanch, A.R.; Tamames, J.; Kämpfer, P.; Kolstø, A.B.; Ramón, D.; Martínez, J.F.; et al. Description of Bacillus toyonensis sp. nov., a novel species of the Bacillus cereus group, and pairwise genome comparisons of the species of the group by means of ANI calculations. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 2013, 36, 383–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Fricker, M.; Reissbrodt, R.; Ehling-Schulz, M. Evaluation of standard and new chromogenic selective plating media for isolation and identification of Bacillus cereus. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2008, 121, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tallent, S.M.; Kotewicz, K.M.; Strain, E.A.; Bennett, R.W. Efficient Isolation and Identification of Bacillus cereus Group. J. AOAC Int. 2012, 95, 446–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guinebretière, M.H.; Thompson, F.L.; Sorokin, A.; Normand, P.; Dawyndt, P.; Ehling-Schulz, M.; Svensson, B.; Sanchis, V.; Nguyen-The, C.; Heyndrickx, M.; et al. Ecological diversification in the Bacillus cereus Group. Environ. Microbiol. 2008, 10, 851–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehling-Schulz, M.; Messelhäußer, U. Bacillus “next generation” diagnostics: Moving from detection toward subtyping and risk-related strain profiling. Front. Microbiol. 2013, 4, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nair, K.; Al-Thani, R.; Al-Thani, D.; Al-Yafei, F.; Ahmed, T.; Jaoua, S. Diversity of Bacillus thuringiensis Strains From Qatar as Shown by Crystal Morphology, δ-Endotoxins and cry Gene Content. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doellinger, J.; Schneider, A.; Stark, T.D.; Ehling-Schulz, M.; Lasch, P. Evaluation of MALDI-ToF mass spectrometry for rapid detection of cereulide from Bacillus cereus cultures. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 2483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehling-Schulz, M.; Svensson, B.; Guinebretière, M.H.; Lindbäck, T.; Andersson, M.; Schulz, A.; Fricker, M.; Christiansson, A.; Granum, P.E.; Märtlbauer, E.; et al. Emetic toxin formation of Bacillus cereus is restricted to a single evolutionary lineage of closely related strains. Microbiology 2005, 151, 183–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Johler, S.; Kalbhenn, E.M.; Heini, N.; Brodmann, P.; Gautsch, S.; Bağcioğlu, M.; Contzen, M.; Stephan, R.; Ehling-Schulz, M. Enterotoxin Production of Bacillus thuringiensis Isolates From Biopesticides, Foods, and Outbreaks. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 1915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bağcıoğlu, M.; Fricker, M.; Johler, S.; Ehling-Schulz, M. Detection and Identification of Bacillus cereus, Bacillus cytotoxicus, Bacillus thuringiensis, Bacillus mycoides and Bacillus weihenstephanensis via Machine Learning Based FTIR Spectroscopy. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzulli, V.; Rondinone, V.; Buchicchio, A.; Serrecchia, L.; Cipolletta, D.; Fasanella, A.; Parisi, A.; Difato, L.; Iatarola, M.; Aceti, A.; et al. Discrimination of Bacillus cereus Group Members by MALDI-TOF Mass Spectrometry. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 7932; Microbiology of Food and Animal Feeding Stuffs-Horizontal Method for the Enumeration of Presumptive Bacillus cereus-Colony-Count Technique at 30 °C. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2004.

- Walsh, P.S.; Metzger, D.A.; Higuchi, R. Chelex 100 as a medium for simple extraction of DNA for PCR-based typing from forensic material. Biotechniques 2013, 10, 506–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dzieciol, M.; Fricker, M.; Wagner, M.; Hein, I.; Ehling-Schulz, M. A novel diagnostic real-time PCR assay for quantification and differentiation of emetic and non-emetic Bacillus cereus. Food Control 2013, 32, 176–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehling-Schulz, M.; Guinebretière, M.H.; Monthán, A.; Berge, O.; Fricker, M.; Svensson, B. Toxin gene profiling of enterotoxic and emetic Bacillus cereus. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2006, 260, 232–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Guinebretière, M.H.; Velge, P.; Couvert, O.; Carlin, F.; Debuyser, M.L. Ability of Bacillus cereus Group Strains To Cause Food Poisoning Varies According to Phylogenetic Affiliation (Groups I to VII) Rather than Species Affiliation. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2010, 48, 3388–3391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- R Development Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2021; ISBN 3-900051-07-0. Available online: http://www.R-project.org (accessed on 17 December 2021).

- Glasset, B.; Herbin, S.; Granier, S.A.; Cavalié, L.; Lafeuille, E.; Guérin, C.; Ruimy, R.; Casagrande-Magne, F.; Levast, M.; Chautemps, N.; et al. Bacillus cereus, a serious cause of nosocomial infections: Epidemiologic and genetic survey. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0194346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorsen, L.; Budde, B.B.; Henrichsen, L.; Martinussen, T.; Jakobsen, M. Cereulide formation by Bacillus weihenstephanensis and mesophilic emetic Bacillus cereus at temperature abuse depends on pre-incubation conditions. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2009, 134, 133–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh-Lakha, S.; Leon-Velarde, C.G.; Chen, S.; Lee, S.; Shannon, K.; Fabri, M.; Downing, G.; Keown, B. A Study To Assess the Numbers and Prevalence of Bacillus cereus and Its Toxins in Pasteurized Fluid Milk. J. Food Prot. 2017, 80, 1085–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, K.M.; Kim, H.J.; Jeong, M.; Koo, M. Enterotoxin Genes, Antibiotic Susceptibility, and Biofilm Formation of Low-Temperature-Tolerant Bacillus cereus Isolated from Green Leaf Lettuce in the Cold Chain. Foods 2020, 9, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Rouzeau-Szynalski, K.; Stollewerk, K.; Messelhäußer, U.; Ehling-Schulz, M. Why be serious about emetic Bacillus cereus: Cereulide production and industrial challenges. Food Microbiol. 2020, 85, 103279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messelhäußer, U.; Frenzel, E.; Blöchinger, C.; Zucker, R.; Kämpf, P.; Ehling-Schulz, M. Emetic Bacillus cereus Are More Volatile Than Thought: Recent Foodborne Outbreaks and Prevalence Studies in Bavaria (2007–2013). BioMed Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 465603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Warda, A.K.; Siezen, R.J.; Boekhorst, J.; Wells-Bennik, M.H.; de Jong, A.; Kuipers, O.P.; Nierop Groot, M.N.; Abee, T. Linking Bacillus cereus Genotypes and Carbohydrate Utilization Capacity. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0156796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendriksen, N.B.; Hansen, B.M. Diagnostic properties of three conventional selective plating media for selection of Bacillus cereus, B. thuringiensis and B. weihenstephanensis. Folia Microbiol. 2011, 56, 535–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chon, J.W.; Song, K.Y.; Kim, H.; Seo, K.H. Comparison of 3 Selective Media for Enumeration of Bacillus cereus in Several Food Matrixes. J. Food Sci. 2014, 79, M2480–M2484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabir, M.S.; Hsieh, Y.H.; Simpson, S.; Kerdahi, K.; Sulaiman, I.M. Evaluation of Two Standard and Two Chromogenic Selective Media for Optimal Growth and Enumeration of Isolates of 16 Unique Bacillus Species. J. Food Prot. 2017, 80, 952–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chon, J.W.; Seo, K.H. Development of a new chromogenic medium for the enumeration of Bacillus cereus in various ready-to-eat foods. Food Control 2021, 128, 108188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, A.C.; Alippi, A.M. Phenotypic and genotypic diversity of Bacillus cereus isolates recovered from honey. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2007, 117, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaves, J.Q.; Pires, E.S.; Vivoni, A.M. Genetic diversity, antimicrobial resistance and toxigenic profiles of Bacillus cereus isolated from food in Brazil over three decades. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2011, 147, 12–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, R.A.; Jian, J.; Beno, S.M.; Wiedmann, M.; Kovac, J. Intraclade Variability in Toxin Production and Cytotoxicity of Bacillus cereus Group Type Strains and Dairy-Associated Isolates. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2018, 84, e02479-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Slamti, L.; Perchat, S.; Gominet, M.; Vilas-Bôas, G.; Fouet, A.; Mock, M.; Sanchis, V.; Chaufaux, J.; Gohar, M.; Lereclus, D. Distinct Mutations in PlcR Explain Why Some Strains of the Bacillus cereus Group Are Nonhemolytic. J. Bacteriol. 2004, 186, 3531–3538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- ISO 11290; Microbiology of the Food Chain-Horizontal Method for the Detection and Enumeration of Listeria monocytogenes and of Listeria spp.—Part 1: Detection Method. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017.

- ISO 6579; Microbiology of the Food Chain-Horizontal Method for the Detection, Enumeration and Serotyping of Salmonella—Part 1: Detection of Salmonella spp. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017.

- Webb, M.D.; Barker, G.C.; Goodburn, K.E.; Peck, M.W. Risk presented to minimally processed chilled foods by psychrotrophic Bacillus cereus. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 93, 94–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cairo, J.; Gherman, I.; Day, A.; Cook, P.E. Bacillus cytotoxicus-A potentially virulent food-associated microbe. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2021, 132, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heini, N.; Stephan, R.; Ehling-Schulz, M.; Johler, S. Characterization of Bacillus cereus group isolates from powdered food products. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2018, 283, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Porcellato, D.; Narvhus, J.; Skeie, S.B. Detection and quantification of Bacillus cereus group in milk by droplet digital PCR. J. Microbiol. Methods 2016, 127, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramarao, N.; Tran, S.L.; Marin, M.; Vidic, J. Advanced methods for detection of Bacillus cereus and its pathogenic factors. Sensors 2020, 20, 2667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walser, V.; Kranzler, M.; Dawid, C.; Ehling-Schulz, M.; Stark, T.D.; Hofmann, T.F. Distribution of the Emetic Toxin Cereulide in Cow Milk. Toxins 2021, 13, 528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porcellato, D.; Aspholm, M.; Skeie, S.B.; Mellegård, H. Application of a novel amplicon-based sequencing approach reveals the diversity of the Bacillus cereus group in stored raw and pasteurized milk. Food Microbiol. 2019, 81, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonis, M.; Felten, A.; Pairaud, S.; Dijoux, A.; Maladen, V.; Mallet, L.; Radomski, N.; Duboisset, A.; Arar, C.; Sarda, X.; et al. Comparative phenotypic, genotypic and genomic analyses of Bacillus thuringiensis associated with foodborne outbreaks in France. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0246885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwenk, V.; Riegg, J.; Lacroix, M.; Märtlbauer, E.; Jessberger, N. Enteropathogenic potential of Bacillus thuringiensis isolates from soil, animals, food and biopesticides. Foods 2020, 9, 1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raymond, B.; Federici, B.A. In defence of Bacillus thuringiensis, the safest and most successful microbial insecticide available to humanity-a response to EFSA. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2017, 93, fix084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- De Bock, T.; Zhao, X.; Jacxsens, L.; Devlieghere, F.; Rajkovic, A.; Spanoghe, P.; Höfte, M.; Uyttendaele, M. Evaluation of B. thuringiensis-based biopesticides in the primary production of fresh produce as a food safety hazard and risk. Food Control 2021, 130, 108390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fuchs, E.; Raab, C.; Brugger, K.; Ehling-Schulz, M.; Wagner, M.; Stessl, B. Performance Testing of Bacillus cereus Chromogenic Agar Media for Improved Detection in Milk and Other Food Samples. Foods 2022, 11, 288. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods11030288

Fuchs E, Raab C, Brugger K, Ehling-Schulz M, Wagner M, Stessl B. Performance Testing of Bacillus cereus Chromogenic Agar Media for Improved Detection in Milk and Other Food Samples. Foods. 2022; 11(3):288. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods11030288

Chicago/Turabian StyleFuchs, Eva, Christina Raab, Katharina Brugger, Monika Ehling-Schulz, Martin Wagner, and Beatrix Stessl. 2022. "Performance Testing of Bacillus cereus Chromogenic Agar Media for Improved Detection in Milk and Other Food Samples" Foods 11, no. 3: 288. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods11030288

APA StyleFuchs, E., Raab, C., Brugger, K., Ehling-Schulz, M., Wagner, M., & Stessl, B. (2022). Performance Testing of Bacillus cereus Chromogenic Agar Media for Improved Detection in Milk and Other Food Samples. Foods, 11(3), 288. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods11030288