Advances in the Formation and Control Methods of Undesirable Flavors in Fish

Abstract

1. Introduction

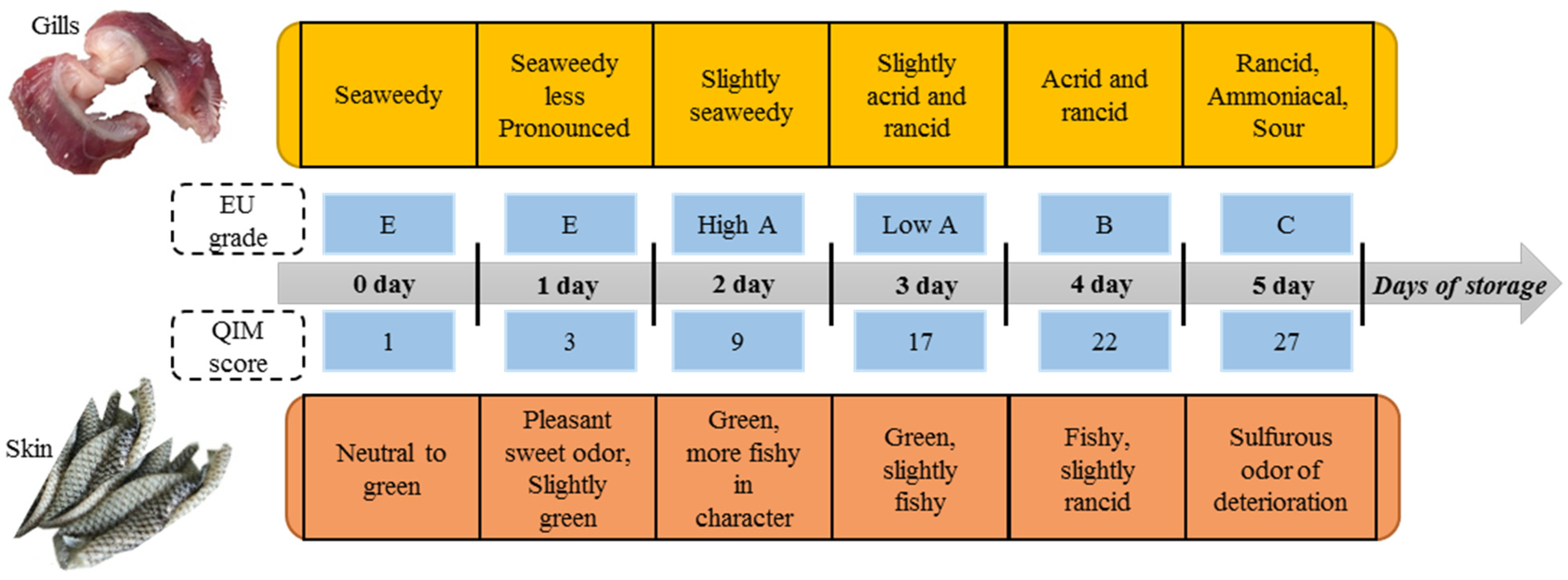

2. Volatile Compounds Contributing to Undesirable Flavors in Fish

3. The Formation of Post−Harvest Undesirable Flavors in Fish

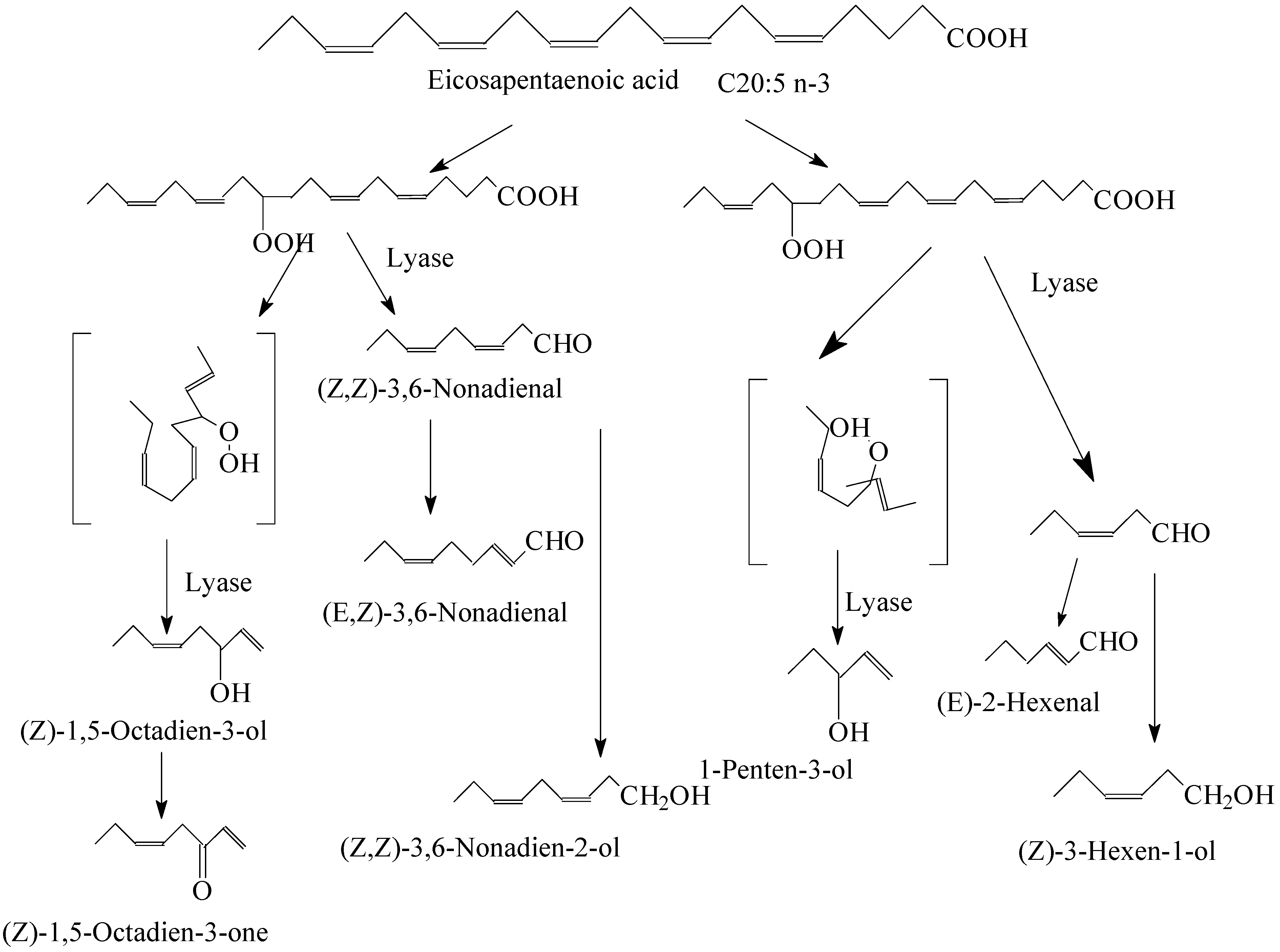

3.1. Lipid Oxidation

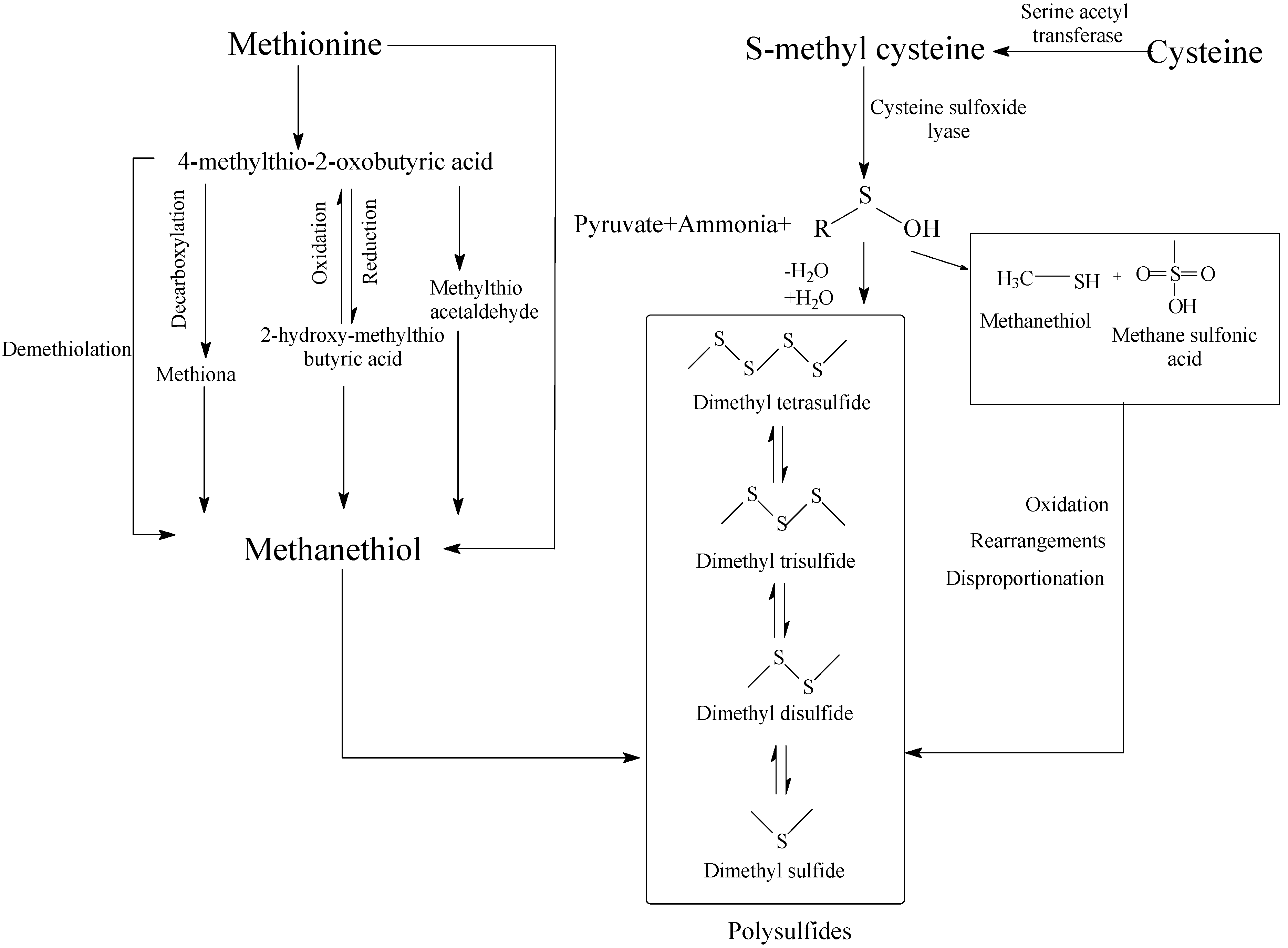

3.2. Microbial Metabolites

3.3. Living Environment

4. Odor Control Techniques

4.1. Environmental Renovation

4.2. Processing Treatment

4.2.1. Freezing

4.2.2. Salting and Drying

4.2.3. High−Pressure Processing

4.2.4. Boiling

4.2.5. Fermenting

4.2.6. Defatting

4.2.7. Masking

4.3. Application of Additives

4.3.1. Synthetic Additives

4.3.2. Natural Additives

4.4. Packaging

4.4.1. Vacuum Packaging (VP)

4.4.2. Modified Atmosphere Packaging (MAP)

4.4.3. Active Packaging (AP)

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhou, X.X.; Chong, Y.Q.; Ding, Y.T.; Gu, S.Q.; Liu, L. Determination of the effects of different washing processes on aroma characteristics in silver carp mince by MMSE-GC-MS, e-nose and sensory evaluation. Food Chem. 2016, 207, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, J.L.; Boyer, G.L.; Zimba, P.V. A review of cyanobacterial odorous and bioactive metabolites: Impacts and management alternatives in aquaculture. Aquaculture 2008, 280, 5–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auffret, M.; Pilote, A.; Proulx, E.; Proulx, D.; Villemur, R. Establishment of a real-time pcr method for quantification of geosmin-producing Streptomyces spp. in recirculating aquaculture systems. Water Res. 2011, 45, 6753–6762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawai, T.; Sakaguchi, M. Fish flavor. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 1996, 36, 257–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- An, Y.; Qian, Y.L.; Alcazar Magana, A.; Xiong, S.; Qian, M.C. Comparative characterization of aroma compounds in silver carp (Hypophthalmichthys molitrix), pacific whiting (Merluccius productus), and alaska pollock (Theragra chalcogramma) surimi by aroma extract dilution analysis, odor activity value, and aroma recombination studies. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2020, 68, 10403–10413. [Google Scholar]

- Howgate, P. Tainting of farmed fish by geosmin and 2-methyliso-borneol: A review of sensory aspects and of ptake/depuration. Aquaculture 2004, 234, 155–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alasalvar, C.; Taylor, K.D.A.; Zubcov, E.; Shahidi, F.; Alexis, M. Differentiation of cultured and wild sea bass (Dicentrarchus labrax): Total lipid content, fatty acid and trace mineral composition. Food Chem. 2002, 79, 145–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, D.; Poole, S.; Kirchhoff, S.; Forde, C. Investigation of sensory and volatile characteristics of farmed and wild barramundi (Lates calcarifer) using gas chromatography-olfactometry mass spectrometry and descriptive sensory analysis. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009, 57, 10302–10312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigorakis, K.; Taylor, K.D.A.; Alexis, M.N. Organoleptic and volatile aroma compounds comparison of wild and cultured gilthead sea bream (Sparus aurata): Sensory differences and possible chemical basis. Aquaculture 2003, 225, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigorakis, K. Compositional and organoleptic quality of farmed and wild gilthead sea bream (Sparus aurata) and sea bass (Dicentrarchus labrax) and factors affecting it: A review. Aquaculture 2007, 272, 55–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, W.Z.; Ying, M.M.; Wang, X.C. Effect of seasons on volatile compounds in grass carp meat. Adv. Mater. Res. 2012, 554–556, 1565–1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.-L.; Tu, Z.-C.; Zhang, L.; Lin, D.-R.; Sha, X.-M.; Zeng, K.; Wang, H.; Pang, J.-J.; Tang, P.-P. Characterization of volatile compounds in grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idellus) soup cooked using a traditional Chinese method by GC-MS. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2017, 41, e12995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Josephson, D.B.; Lindsay, R.C. Enzymic generation of volatile aroma compounds from fresh fish. In Biogeneration of Aromas; American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, USA, 1986; pp. 201–219. [Google Scholar]

- Suffet, I.H.; Djanette, K.; Auguste, B. The drinking water taste and odor wheel for the millennium: Beyond geosmin and 2-methylisoborneol. Water Sci. Technol. 1999, 40, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindholm-Lehto, P.C.; Vielma, J. Controlling of geosmin and 2-methylisoborneol induced off-flavours in recirculating aquaculture system farmed fish-A review. Aquac. Res. 2019, 50, 9–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, C.S.; Schrader, K.K. Off-flavors in pond-grown ictalurid catfish: Causes and management options. J. World Aquac. Soc. 2020, 51, 7–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, M.A.; Hyldig, G.; Strobel, B.W.; Henriksen, N.H.; Jørgensen, N.O.G. Chemical and sensory quantification of geosmin and 2-methylisoborneol in rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) from recirculated aquacultures in relation to concentrations in basin water. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2011, 59, 12561–12568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Liao, T.; Mccrummen, S.T.; Hanson, T.R.; Wang, Y. Exploration of volatile compounds causing off-flavor in farm-raised channel catfish (Ictalurus punctatus) fillet. Aquac. Int. 2017, 25, 413–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Rai, P.K.; Jeon, Y.J.; Kim, K.-H.; Kwon, E.E. The role of algae and cyanobacteria in the production and release of odorants in water. Environ. Pollut. 2017, 227, 252–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podduturi, R.; Petersen, M.A.; Mahmud, S.; Rahman, M.M.; Jørgensen, N.O.G. Potential contribution of fish feed and phytoplankton to the content of volatile terpenes in cultured pangasius (Pangasianodon hypophthalmus) and tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus). J. Agric. Food Chem. 2017, 65, 3730–3736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mccrummen, S.T.; Wang, Y.; Hanson, T.R.; Bott, L.; Liu, S. Culture environment and the odorous volatile compounds present in pond-raised channel catfish (Ictalurus punctatus). Aquac. Int. 2018, 26, 685–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guen, S.L.; Prost, C.; Demaimay, M. Characterization of odorant compounds of mussels (Mytilus edulis) according to their origin using gas chromatography-olfactometry and gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. A 2000, 896, 361–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varlet, V.; Fernandez, X. Review. Sulfur-containing volatile compounds in seafood: Occurrence, odorant properties and mechanisms of formation. Food Sci. Technol. Int. 2010, 16, 463–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alasalvar, C.; Taylor, K.D.A.; Shahidi, F. Comparison of volatiles of cultured and wild sea bream (Sparus aurata) during storage in ice by dynamic headspace analysis/gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005, 53, 2616–2622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hebard, C. Occurrence and significance of trimethylamine oxide and its derivatives in fish and shellfish. In Chemistry and Biochemistry of Marine Food Products; AVI: Westport, CT, USA, 1982; pp. 149–304. [Google Scholar]

- Triqui, R.; Bouchriti, N. Freshness assessments of moroccan sardine (Sardina pilchardus): Comparison of overall sensory changes to instrumentally determined volatiles. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2003, 51, 7540–7546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triqui, R. Sensory and flavor profiles as a means of assessing freshness of hake (Merluccius merluccius) during ice storage. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2005, 222, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milo, C.; Grosch, W. Changes in the odorants of boiled trout (Salmo fario) as affected by the storage of the raw material. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1993, 41, 2366–2371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sae-Leaw, T.; Benjakul, S.; Gokoglu, N.; Nalinanon, S. Changes in lipids and fishy odour development in skin from nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) stored in ice. Food Chem. 2013, 141, 2466–2472. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Reineccius, G.A. Symposium on meat flavor off-flavors in meat and fish—A review. J. Food Sci. 1979, 44, 12–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, L.; Decker, E.A. Phospholipids in foods: Prooxidants or antioxidants? J. Agric. Food Chem. 2016, 96, 18–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidal, N.P.; Manzanos, M.J.; Goicoechea, E.; Guillén, M.D. Farmed and wild sea bass (Dicentrarchus labrax) volatile metabolites: A comparative study by SPME-GC/MS. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2016, 96, 1181–1193. [Google Scholar]

- Josephson, D.B.; Lindsay, R.C.; Stuiber, D.A. Identification of compounds characterizing the aroma of fresh whitefish (Coregonus clupeaformis). J. Agric. Food Chem. 1983, 31, 326–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghavan, S.; Hultin, H.O. Effect of various antioxidants on the oxidative stability of acid and alkali solubilized muscle protein isolates. J. Food Biochem. 2010, 33, 163–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jónsdóttir, R.; Bragadóttir, M.; Olafsdottir, G. The role of volatile compounds in odor development during hemoglobin-mediated oxidation of cod muscle membrane lipids. J. Aquat. Food Prod. Technol. 2007, 16, 67–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.; Xu, S.; Wang, Z. Kinetics of lipid oxidation and off-odor formation in silver carp mince: The effect of lipoxygenase and hemoglobin. Food Res. Int. 2009, 42, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morita, K.; Kubota, K.; Aishima, T. Comparison of aroma characteristics of 16 fish species by sensory evaluation and gas chromatographic analysis. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2003, 83, 289–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nomikos, T.; Karantonis, H.C.; Skarvelis, C.; Demopoulos, C.A.; Zabetakis, I. Antiatherogenic properties of lipid fractions of raw and fried fish. Food Chem. 2006, 96, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansur, M.; Bhadra, A.; Takamura, H.; Matoba, T. Volatile flavor compounds of some sea fish and prawn species. Fish. Sci. 2003, 69, 864–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Sohn, J.-H.; Taki, Y.; Ushio, H.; Kohata, T.; Shioya, I.; Ohshima, T. Lipid oxidations in ordinary and dark muscles of fish: Influences on rancid off-odor development and color darkening of yellowtail flesh during ice storage. J. Food Sci. 2005, 70, s490–s496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, R.J.; Kinsella, J.E. Lipoxygenase generation of specific volatile flavor carbonyl compounds in fish tissues. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1989, 37, 279–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prost, C.; Hallier, A.; Cardinal, M.; Serot, T.; Courcoux, P. Effect of storage time on raw sardine (Sardina pilchardus) flavor and aroma quality. J. Food Sci. 2004, 69, S198–S204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, R.J.; Kinsella, J.E. Oxidation of polyunsaturated fatty acids: Mechanisms, products, and inhibition with emphasis on fish. Adv. Food Nutr. Res. 1989, 33, 233–341. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Jiang, C.; Zhang, C.; Li, X.; Zhu, D.; Li, J. Determination of volatile compounds in turbot (Psetta maxima) during refrigerated storage by headspace solid-phase microextraction and gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2014, 94, 2464–2471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patton, S.; Barnes, I.J.; Evans, L.E. n-Deca-2,4-dienal, its origin from linoleate and flavor significance in fats. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 1959, 40, 280–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swoboda, P.A.T.; Peers, K.E. Volatile odorous compounds responsible for metallic, fishy taint formed in butterfat by selective oxidation. J. Sci. Food Agric. 1977, 28, 1010–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, O.P.; Sumar, S. Compositional changes and spoilage in fish (Part II)—Microbiological induced deterioration. Nutr. Food Sci. 1998, 98, 325–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesfay, S.; Teferi, M. Assessment of fish post-harvest losses in Tekeze dam and Lake Hashenge fishery associations: Northern Ethiopia. Agric. Food Secur. 2017, 6, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gram, L.; Huss, H.H. Microbiological spoilage of fish and fish products. Int. J. food Microbiol. 1996, 33, 121–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parlapani, F.F.; Kormas, K.A.; Boziaris, I.S. Microbiological changes, shelf life and identification of initial and spoilage microbiota of sea bream fillets stored under various conditions using 16S rRNA gene analysis. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2015, 95, 2386–2394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfaro, B.; Hernández, I.; Marc, Y.L.; Pin, C. Modelling the effect of the temperature and carbon dioxide on the growth of spoilage bacteria in packed fish products. Food Control 2013, 29, 429–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broekaert, K.; Heyndrickx, M.; Herman, L.; Devlieghere, F.; Vlaemynck, G. Seafood quality analysis: Molecular identification of dominant microbiota after ice storage on several general growth media. Food Microbiol. 2011, 28, 1162–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalgaard, P. Qualitative and quantitative characterization of spoilage bacteria from packed fish. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 1995, 26, 319–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, C.J. Psychrobacters and related bacteria in freshwater fish. J. Food Prot. 2000, 63, 315–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gram, L.; Dalgaard, P. Fish spoilage bacteria—Problems and solutions. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2002, 13, 262–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parlapani, F.F.; Boziaris, I.S. Monitoring of spoilage and determination of microbial communities based on 16S rRNA gene sequence analysis of whole sea bream stored at various temperatures. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 66, 553–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nychas, G.-J.E.; Marshall, D.L.; Sofos, J.N. Meat, poultry, and seafood. In Food Microbiology: Fundamentals and Frontiers; ASM Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Hickey, M.E.; Accumanno, G.M.; Mcintosh, D.M.; Blank, G.S.; Lee, J.L. Comparison of extracellular DNase- and protease-producing spoilage bacteria isolated from Delaware pond-sourced and retail channel catfish (Ictalurus punctatus). J. Sci. Food Agric. 2015, 95, 1024–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papadopoulos, V.; Chouliara, I.; Badeka, A.; Savvaidis, I.N.; Kontominas, M.G. Effect of gutting on microbiological, chemical, and sensory properties of aquacultured sea bass (Dicentrarchus labrax) stored in ice. Food Microbiol. 2003, 20, 411–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gram, L.; Trolle, G.; Huss, H.H. Detection of specific spoilage bacteria from fish stored at low (0 °C) and high (20 °C) temperatures. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 1987, 4, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serio, A.; Fusella, G.C.; Lòpez, C.C.; Sacchetti, G.; Paparella, A. A survey on bacteria isolated as hydrogen sulfide-producers from marine fish. Food Control 2014, 39, 111–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.-C.; Kung, H.-F.; Chen, W.-C.; Lin, W.-F.; Hwang, D.-F.; Lee, Y.-C.; Tsai, Y.-H. Determination of histamine and histamine-forming bacteria in tuna dumpling implicated in a food-borne poisoning. Food Chem. 2008, 106, 612–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parlapani, F.F.; Mallouchos, A.; Haroutounian, S.A.; Boziaris, I.S. Volatile organic compounds of microbial and non-microbial origin produced on model fish substrate un-inoculated and inoculated with gilt-head sea bream spoilage bacteria. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 78, 54–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broekaert, K.; Noseda, B.; Heyndrickx, M.; Vlaemynck, G.; Devlieghere, F. Volatile compounds associated with Psychrobacter spp. and Pseudoalteromonas spp., the dominant microbiota of brown shrimp (Crangon crangon) during aerobic storage. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2013, 166, 487–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casaburi, A.; Piombino, P.; Nychas, G.-J.; Villani, F.; Ercolini, D. Bacterial populations and the volatilome associated to meat spoilage. Food Microbiol. 2015, 45, 83–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nychas, G.J.E.; Drosinos, E.; Board, R.G. The microbiology of meat and poultry. In Chemical Changes in Stored Meat; Blackie Academic and Professional: London, UK, 1998; pp. 288–326. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrocino, I.; Storia, A.L.; Torrieri, E.; Musso, S.S.; Mauriello, G.; Villani, F.; Ercolini, D. Antimicrobial packaging to retard the growth of spoilage bacteria and to reduce the release of volatile metabolites in meat stored under vacuum at 1 °C. J. Food Prot. 2013, 76, 52–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duflos, G.; Coin, V.M.; Cornu, M.; Antinelli, J.-F.; Malle, P. Determination of volatile compounds to characterize fish spoilage using headspace/mass spectrometry and solid-phase microextraction/gas chromatography/mass spectrometry. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2006, 86, 600–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joffraud, J.J.; Leroi, F.; Roy, C.; Berdaguéb, J.L. Characterisation of volatile compounds produced by bacteria isolated from the spoilage flora of cold-smoked salmon. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2001, 66, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ercolini, D.; Casaburi, A.; Nasi, A.; Ferrocino, I.; Monaco, R.D.; Ferranti, P.; Mauriello, G.; Villani, F. Different molecular types of Pseudomonas fragi have the same overall behaviour as meat spoilers. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2010, 142, 120–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karpas, Z.; Tilman, B.; Gdalevsky, R.; Lorber, A. Determination of volatile biogenic amines in muscle food products by ion mobility spectrometry. Anal. Chim. Acta 2002, 463, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimba, P.V.; Tucker, C.S.; Mischke, C.C.; Grimm, C.C. Short-term effect of diuron on catfish pond ecology. N. Am. J. Aquac. 2002, 64, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimba, P.V.; Boue, S.; Chatham, M.A.; Nonneman, D. Variants of microcystin in south-eastern USA channel catfish (Ictalurus punctatus Rafinesque) production ponds. SIL Proc. 1922–2010 2002, 28, 1163–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicklisch, A.; Shatwell, T.; Köhler, J. Analysis and modelling of the interactive effects of temperature and light on phytoplankton growth and relevance for the spring bloom. J. Plankton Res. 2008, 30, 75–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McQueen, D.J.; Leam, D.R.S. Influence of water temperature and nitrogen to phosphorus ration the dominance of blue-green algae in lake St. George, Ontario. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 1987, 44, 598–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehman, P.W.; Marr, K.; Boyer, G.L.; Acuna, S.; Teh, S.J. Long-term trends and causal factors associated with microcystis abundance and toxicity in San Francisco Estuary and implications for climate change impacts. Hydrobiologia 2013, 718, 141–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paerl, H.W.; Huisman, J. Blooms like it hot. Science 2008, 320, 57–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginzburg, B.; Chalifa, I.; Zohary, T.; Hadas, O.; Dor, I.; Lev, O. Identification of oligosulphide odorous compounds and their source in the Lake of Galilee. Water Res. 1998, 32, 1789–1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zorn, H.; Langhoff, S.; Sheibner, M.; Berger, R.G. Cleavage of β,β-carotene to flavor compounds by fungi. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2003, 62, 331–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Yu, J.W.; Li, Z.L.; Guo, Z.H.; Burch, M.; Lin, T.F. Taihu Lake not to blame for Wuxi’s woes. Science 2008, 319, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Xie, P.; Ma, Z.; Niu, Y.; Tao, M.; Deng, X.; Wang, Q. A systematic study on spatial and seasonal patterns of eight taste and odor compounds with relation to various biotic and abiotic parameters in Gonghu Bay of Lake Taihu, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2010, 409, 314–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dickschat, J.S.; Nawrath, T.; Thiel, V.; Kunze, B.; Muller, R.; Schulz, S. Biosynthesis of the off-flavor 2-methylisoborneol by the myxobacterium Nannocystis exedens. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2007, 46, 8287–8290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, C.S. Off-flavor problems in aquaculture. Rev. Fish. Sci. 2000, 8, 45–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimba, P.V.; Grimm, C.C. A synoptic survey of musty/muddy odor metabolites and microcystin toxin occurrence and concentration in southeastern USA channel catfish (Ictalurus punctatus Ralfinesque) production ponds. Aquaculture 2003, 218, 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez, R.; Whangchai, N.; Sompong, U.; Prarom, W.; Sugiura, N. Off-flavour in nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) cultured in an integrated pond-cage culture system. Maejo Int. J. Sci. Technol. 2013, 7, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Houle, S.; Schrader, K.K.; François, N.R.L.; Comeau, Y.; Kharoune, M.; Summerfelt, S.T.; Savoie, A.; Vandenberg, G.W. Geosmin causes off-flavour in arctic charr in recirculating aquaculture systems. Aquac. Res. 2011, 42, 360–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, H.Y.; Yung, I.K.S.; Ma, W.C.J.; Kim, J.S. Analysis of volatile components in frozen and dried scallops (Patinopecten yessoensis) by gas chromatography/mass spectrometry. Food Res. Int. 2002, 35, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guttman, L.; Rijn, J.V. Identification of conditions underlying production of geosmin and 2-methylisoborneol in a recirculating system. Aquaculture 2008, 279, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burr, G.S.; Wolters, W.R.; Schrader, K.K.; Summerfelt, S.T. Impact of depuration of earthy-musty off-flavors on fillet quality of atlantic salmon, salmo salar, cultured in a recirculating aquaculture system. Aquac. Eng. 2012, 50, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drake, S.L.; Drake, M.A.; Sanderson, R.; Daniels, H.V.; Yates, M.D. The effect of purging time on the sensory properties of aquacultured southern flounder (Paralichthys lethostigma). J. Sens. Stud. 2010, 25, 246–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmeri, G.; Turchini, G.M.; Marriott, P.J.; Morrison, P.; Silva, S. Biometric, nutritional and sensory characteristic modifications in farmed Murray cod (Maccullochella peelii peelii) during the purging process. Aquaculture 2009, 287, 354–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, B.W.; Schrader, K.K. Effect of stocking large channel catfish in a biofloc technology production system on production and incidence of common microbial off-flavor compounds. J. Aquac. Res. Dev. 2015, 6, 314. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, T.J.; Nakano, K.; Matsumara, M. Ultrasonic irradiation for blue-green algae bloom control. Environ. Technol. Lett. 2001, 22, 383–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, C.Y.; Park, M.H.; Joung, S.H.; Kim, H.S.; Jang, K.Y.; Oh, H.M. Growth inhibition of cyanobacteria by ultrasonic radiation: Laboratory and enclosure studies. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2003, 37, 3031–3037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.W.; Wu, Q.Y.; Hao, H.W.; Chen, Y.F.; Wu, M.S. Growth inhibition of the cyanobacterium Spirulina (Arthrospira) platensis by 1.7 MHz ultrasonic irradiation. J. Appl. Phycol. 2003, 15, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halliwell, B.; Gutteridge, J.M.C. Free radicals in biology and medicine. J. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1999, 1, 331–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.W.; Wu, Q.Y.; Hao, H.W.; Chen, Y.F.; Wu, M.S. Effect of 1.7 MHz ultrasound on a gas-vacuolate cyanobacterium and a gas-vacuole negative cyanobacterium. Colloids Surf. B 2004, 36, 115–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nam-Koong, H.; Schroeder, J.P.; Petrick, G.; Schulz, C. Removal of the off-flavor compounds geosmin and 2-methylisoborneol from recirculating aquaculture system water by ultrasonically induced cavitation. Aquac. Eng. 2016, 70, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, D.; Newcombe, G.; Sztajnbok, P. The application of powdered activated carbon for mib and geosmin removal: Predicting pac doses in four raw waters. Water Res. 2001, 35, 1325–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newcombe, G.; Morrison, J.; Hepplewhite, C.; Knappe, D.R.U. Simultaneous adsorption of MIB and NOM onto activated carbon: II. Competitive effects. Carbon 2002, 40, 2147–2156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, W.K.; Qu, Q.Y.; Gunten, U.V.; Chen, C.; Yu, G.; Wang, Y.J. Comparison of methylisoborneol and geosmin abatement in surface water by conventional ozonation and an electro-peroxone process. Water Res. 2017, 108, 373–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atasi, K.Z.; Chen, T.; Huddieston, J.I.; Young, C.C.; Suffet, I.H. Factor screening for ozonating the taste- and odor-causing compounds in source water at Detroit, USA. Water Sci. Technol. 1999, 40, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collivignarelli, C.; Sorlini, S. AOPs with ozone and UV radiation in drinking water: Contaminants removal and effects on disinfection byproducts formation. Water Sci. Technol. 2004, 49, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Gonzalez, L.; Pettit, S.L.; Zhao, W.; Michaels, J.T.; Kuhn, J.N.; Alcantar, N.A.; Ergas, S.J. Oxidation of off flavor compounds in recirculating aquaculture systems using UV-TiO2 photocatalysis. Aquaculture 2019, 502, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berlt, M.M.G.; Schneider, R.D.C.D.S.; Machado, Ê.L.; Kist, L.T. Comparative assessment of the degradation of 2-methylisoborneol and geosmin in freshwater using advanced oxidation processes. Environ. Technol. 2021, 42, 3832–3839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narayan, L.V.; III, W.J.N. Biological control: Isolation and bacterial oxidation of the taste- and-odor compound geosmin. J. Am. Water Work. Assoc. 1974, 66, 532–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.H.; Yuan, R.F.; Shi, C.H.; Yu, L.Y.; Gu, J.N.; Zhang, C.L. Biodegradation of geosmin in drinking water by novel bacteria isolated from biologically active carbon. J. Environ. Sci. 2011, 23, 816–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izaguirre, G.; Wolfe, R.L.; Means, E.G. Degradation of 2-methylisoborneol by aquatic bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1988, 54, 2424–2431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhadi, S.L.N.; Huck, P.M.; Slawson, R.M. Factors affecting the removal of geosmin and MIB in drinking water biofilters. J. Am. Water Work. Assoc. 2006, 98, 108–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, R.; Zhou, B.; Shi, C.; Yu, L.; Zhang, C.; Gu, J. Biodegradation of 2-methylisoborneol by bacteria enriched from biological activated carbon. Front. Environ. Sci. Eng. 2012, 6, 701–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clercin, N.A.; Druschel, G.K.; Gray, M. Occurrences of 2-methylisoborneol and geosmin-degrading bacteria in a eutrophic reservoir and the role of cell-bound versus dissolved fractions. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 297, 113304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, G.; Park, S.; Kang, D.W.; Krajmalnik-Brown, R.; Rittmann, B.E. 2,4,5-Trichlorophenol degradation using a novel TiO2-coated biofilm carrier: Roles of adsorption, photocatalysis, and biodegradation. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011, 45, 8359–8367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Park, S.; Rittmann, B. Degradation of reactive dyes in a photocatalytic circulating-bed biofilm reactor. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2012, 109, 884–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, S.Y.; Zhao, X.Y.; Zhou, Z.; Li, M.Y.; Zhu, L. Effective removal of odor substances using intimately coupled photocatalysis and biodegradation system prepared with the silane coupling agent (SCA)-enhanced TiO2 coating method. Water Res. 2021, 188, 116569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.S.; Al-Belushi, R.M.; Guizani, N.; Al-Saidi, G.S.; Soussi, B. Fat oxidation in freeze-dried grouper during storage at different temperatures and moisture contents. Food Chem. 2009, 114, 1257–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolstorebrov, I.; Eikevik, T.M.; Bantle, M. Effect of low and ultra-low temperature applications during freezing and frozen storage on quality parameters for fish. Int. J. Refrig. 2016, 63, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indergård, E.; Tolstorebrov, I.; Larsen, H.; Eikevik, T.M. The influence of long-term storage, temperature and type of packaging materials on the quality characteristics of frozen farmed Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar). Int. J. Refrig. 2014, 41, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Sun, F.; Xia, X.; Xu, H.; Kong, B. The comparison of ultrasound-assisted immersion freezing, air freezing and immersion freezing on the muscle quality and physicochemical properties of common carp (Cyprinus carpio) during freezing storage-sciencedirect. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2019, 51, 281–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, X.; Chen, S.; Lin, H. Oxidative stability of dried seafood products during processing and storage: A review. J. Aquat. Food Prod. Technol. 2019, 28, 329–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Mao, L. Influences of hot air drying and microwave drying on nutritional and odorous properties of grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idellus) fillets. Food Chem. 2008, 110, 647–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Rubai, H.H.; Hassan, K.H.A.; Eskandder, M.Z. Drying and salting fish using different methods and their effect on the sensory, chemical and microbial indices. Multidiscip. Rev. 2020, 3, e2020003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonin, H.; Duranton, F.; Lamballerie, M.D. New insights into the high-pressure processing of meat and meat products. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2012, 11, 285–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pita-Calvo, C.; Guerra-Rodríguez, E.; Saraiva, J.A.; Aubourg, S.P.; Vázquez, M. Effect of high-pressure processing pretreatment on the physical properties and colour assessment of frozen european hake (Merluccius merluccius) during long term storage. Food Res. Int. 2018, 112, 233–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campus, M. High pressure processing of meat, meat products and seafood. Food Eng. Rev. 2010, 2, 256–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salum, P.; Guclu, G.; Selli, S. Comparative evaluation of key aroma-active compounds in raw and cooked red mullet (Mullus barbatus) by aroma extract dilution analysis. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2017, 65, 8402–8408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.J.; Son, K.T.; Lee, S.G.; Park, S.Y.; Heu, M.S.; Kim, J.S. Suppression of lipid deterioration in boiled-dried anchovy by coating with fish gelatin hydrolysates. J. Food Biochem. 2017, 41, e12331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cyprian, O.O.; Nguyen, M.V.; Sveinsdottir, K.; Tomasson, T.; Arason, S. Influence of blanching treatment and drying methods on the drying characteristics and quality changes of dried sardine (Sardinella gibbosa) during storage. Dry. Technol. 2016, 35, 478–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udomsil, N.; Rodtong, S.; Choi, Y.J.; Hua, Y.; Yongsawatdigul, J. Use of Tetragenococcus halophilus as a starter culture for flavor improvement in fish sauce fermentation. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2011, 59, 8401–8408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fukami, K.; Funatsu, Y.; Kawasaki, K.; Watabe, S. Improvement of fish-sauce odor by treatment with bacteria isolated from the fish-sauce mush (Moromi) made from frigate mackerel. J. Food Sci. 2004, 69, 45–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Ahn, H.J.; Yook, H.S.; Kim, K.S.; Rhee, M.S.; Ryu, G.H.; Byun, M.W. Color, flavor, and sensory characteristics of gamma-irradiated salted and fermented anchovy sauce. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 2004, 69, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.P.; Pan, B.S. Modification of fish oil aroma using a macroalgal lipoxygenase. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 2000, 77, 343–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sae-leaw, T.; Benjakul, S.; O’Brien, N.M. Effects of defatting and tannic acid incorporation during extraction on properties and fishy odour of gelatin from seabass skin. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 65, 661–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yarnpakdee, S.; Benjakul, S.; Penjamras, P.; Kristinsson, H.G. Chemical compositions and muddy flavour/odour of protein hydrolysate from nile tilapia and broadhead catfish mince and protein isolate. Food Chem. 2014, 142, 210–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdollahi, M.; Undeland, I. Structural, functional, and sensorial properties of protein isolate produced from salmon, cod, and herring by-products. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2018, 11, 1733–1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bett, K.L.; Ingram, D.A.; Grimm, C.C.; Vinyard, B.T.; Boyette, K.D.C.; Dionigi, C.P. Alteration of the sensory perception of the muddy/earthy odorant 2-methylisoborneol in channel catfish Ictalurus punctatus fillet tissues by addition of seasonings. J. Sens. Stud. 2000, 15, 459–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negbenebor, C.A.; Godiya, A.A.; Igene, J.O. Evaluation of Clarias anguillaris treated with spice (Piper guineense) for washed mince and kamaboko-type product. J. Food Compos. Anal. 1999, 12, 315–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, K.P.P. Ginger as a spice and flavorant. In The Agronomy and Economy of Turmeric and Ginger; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2013; pp. 497–510. [Google Scholar]

- Pressman, P.; Clemens, R.; Hayes, W.; Reddy, C. Food additive safety: A review of toxicologic and regulatory issues. Toxicol. Res. Appl. 2017, 1, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladikos, D.; Lougovois, V. Lipid oxidation in muscle foods: A review. Food Chem. 1990, 35, 295–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucera, A.; Costa, C.; Conte, A.; Nobile, M.A.D. Food applications of natural antimicrobial compounds. Front. Microbiol. 2012, 3, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dave, D.; Ghaly, A.E. Meat spoilage mechanisms and preservation techniques: A critical review. Am. J. Agric. Biol. Sci. 2011, 6, 486–510. [Google Scholar]

- Slavin, M.; Dong, M.; Gewa, C. Effect of clove extract pretreatment and drying conditions on lipid oxidation and sensory discrimination of dried omena (Rastrineobola argentea) fish. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 51, 2376–2385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina, I.; González, M.J.; Iglesias, J.; Hedges, N.D. Effect of hydroxycinnamic acids on lipid oxidation and protein changes as well as water holding capacity in frozen minced horse mackerel white muscle. Food Chem. 2009, 114, 881–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pazos, M.; Gallardo, J.M.; Torres, J.L.; Medina, I. Activity of grape polyphenols as inhibitors of the oxidation of fish lipids and frozen fish muscle. Food Chem. 2005, 92, 547–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pazos, M.; González, M.J.; Gallardo, J.M.; Torres, J.L.; Medina, I. Preservation of the endogenous antioxidant system of fish muscle by grape polyphenols during frozen storage. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2005, 220, 514–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, L.; Zhu, J.; Li, X.; Li, J. Effect of tea polyphenols on the physical and chemical characteristics of dried-seasoned squid (Dosidicus gigas) during storage. Food Control 2013, 31, 586–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Z.; Shahidi, F. Chemoenzymatic synthesis of phytosteryl ferulates and evaluation of their antioxidant activity. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2011, 59, 12375–12383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galati, G.; Lin, A.; Sultan, A.M.; O’Brien, P.J. Cellular and in vivo hepatotoxicity caused by green tea phenolic acids and catechins. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2006, 40, 570–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maqsood, S.; Benjakul, S.; Shahidi, F. Emerging role of phenolic compounds as natural food additives in fish and fish products. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2013, 53, 162–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nirmal, N.P.; Benjakul, S. Melanosis and quality changes of pacific white shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei) treated with catechin during iced storage. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009, 57, 3578–3586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maqsood, S.; Benjakul, S. Synergistic effect of tannic acid and modified atmospheric packaging on the prevention of lipid oxidation and quality losses of refrigerated striped catfish slices. Food Chem. 2010, 121, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulares, M.; Moussa, O.B.; Mankai, M.; Sadok, S.; Hassouna, M. Effects of lactic acid bacteria and citrus essential oil on the quality of vacuum-packed sea bass (Dicentrarchus labrax) fillets during refrigerated storage. J. Aquat. Food Prod. Technol. 2018, 27, 698–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goulas, A.E.; Kontominas, M.G. Combined effect of light salting, modified atmosphere packaging and oregano essential oil on the shelf-life of sea bream (Sparus aurata): Biochemical and sensory attributes. Food Chem. 2007, 100, 287–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erkan, N.; Tosun, Ş.Y.; Ulusoy, Ş.; Üretener, G. The use of thyme and laurel essential oil treatments to extend the shelf life of bluefish (Pomatomus saltatrix) during storage in ice. J. Verbr. Lebensm. 2011, 6, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayasena, D.D.; Jo, C. Essential oils as potential antimicrobial agents in meat and meat products: A review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2013, 34, 96–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burt, S. Essential oils: Their antibacterial properties and potential applications in foods-a review. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2004, 94, 223–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, A.; Xiong, Y.L. Myoprotein-phytophenol interaction: Implications for muscle food structure-forming properties. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf. 2021, 20, 2801–2824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeong, S.; Lee, H.G.; Cho, C.H.; Yoo, S.R. Deodorization films based on polyphenol compound-rich natural deodorants and polycaprolactone for removing volatile sulfur compounds from kimchi. J. Food Sci. 2021, 86, 1004–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, F.; Ding, Y.; Ye, X.; Liu, D. Cinnamon and nisin in alginate-calcium coating maintain quality of fresh northern snakehead fish fillets. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2010, 43, 1331–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flick, G.J.; Hong, G.-P.; Knobl, G.M. Lipid oxidation of seafood during storage. In Lipid Oxidation in Food; ACS: Washington, DC, USA, 1992; pp. 183–207. [Google Scholar]

- Noseda, B.; Vermeulen, A.; Ragaert, P.; Devlieghere, F. Packaging of fish and fishery products. In Seafood Processing: Technology, Quality and Safety; Wiley: Chichester, UK, 2013; pp. 237–261. [Google Scholar]

- Narasimha Rao, D.; Sachindra, N.M. Modified atmosphere and vacuum packaging of meat and poultry products. Food Rev. Int. 2002, 18, 263–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivertsvik, M.; Jeksrud, W.K.; Rosnes, J.T. A review of modified atmosphere packaging of fish and fishery products—Significance of microbial growth, activities and safety. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2002, 37, 107–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, A.Å.; Mørkøre, T.; Rudi, K.; Langsrud, Ø.; Eie, T. The combined effect of superchilling and modified atmosphere packaging using CO2 emitter on quality during chilled storage of pre-rigor salmon fillets (Salmo salar). J. Sci. Food Agric. 2009, 89, 1625–1633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermeiren, L.; Devlieghere, F.; Beest, M.V.; Beest, M.V.; Kruijf, N.D.; Debevere, J. Developments in the active packaging of foods. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2004, 10, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyagi, P.; Salem, K.S.; Hubbe, M.A.; Pal, L. Advances in barrier coatings and film technologies for achieving sustainable packaging of food products—A review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 115, 461–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maes, C.; Luyten, W.; Herremans, G.; Peeters, R.; Carleer, R.; Buntinx, M. Recent Updates on the Barrier Properties of Ethylene Vinyl Alcohol Copolymer (EVOH): A Review. Polym. Rev. 2018, 58, 209–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaikh, S.; Yaqoob, M.; Aggarwal, P. An overview of biodegradable packaging in food industry. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 2021, 4, 503–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jafarzadeh, S.; Salehabadi, A.; Nafchi, A.M.; Oladzadabbasabadi, N.; Jafari, S.M. Cheese packaging by edible coatings and biodegradable nanocomposites; improvement in shelf life, physicochemical and sensory properties. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 116, 218–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, S.A.A.; El-Sakhawy, M.; El-Sakhawy, M.A.-M. Polysaccharides, protein and lipid -based natural edible films in food packaging: A review. Carbohydr. Polym. 2020, 238, 116178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Debeaufort, F.; Quezada-Gallo, J.A.; Voilley, A. Edible films and coatings: Tomorrow’s packagings: A review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 1998, 38, 299–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahidi, F.; Arachchi, J.K.V.; Jeon, Y.J. Food applications of chitin and chitosans. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 1999, 10, 37–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Broek, L.A.M.; Knoop, R.J.I.; Kappen, F.H.J.; Boeriu, C.G. Chitosan films and blends for packaging material. Carbohydr. Polym. 2015, 116, 237–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojagh, S.M.; Rezaei, M.; Razavi, S.H.; Hosseini, S.M.H. Effect of chitosan coatings enriched with cinnamon oil on the quality of refrigerated rainbow trout. Food Chem. 2010, 120, 193–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vimaladevi, S.; Panda, S.K.; Xavier, K.A.M.; Bindu, J. Packaging performance of organic acid incorporated chitosan films on dried anchovy (Stolephorus indicus). Carbohydr. Polym. 2015, 127, 189–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Restuccia, D.; Spizzirri, U.G.; Parisi, O.I.; Cirillo, G.; Curcio, M.; Iemma, F.; Puoci, F.; Vinci, G.; Picci, N. New EU regulation aspects and global market of active and intelligent packaging for food industry applications. Food Control 2010, 21, 1425–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, B.; Keshwani, A.; Kharkwal, H. Antimicrobial food packaging: Potential and pitfalls. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 6, 611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No. | Off−Flavors | Origin | Oxidation Causes | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1−Penten−3−ol | Eicosapentaenoic acid | 15−Lipoxygenase | [13] |

| 2 | (E)−2−Pentenal | Linolenic acid, docosahexaenoic acid /n−3 polyunsaturated fatty acids | 15−Lipoxygenase | [42] |

| 3 | Hexanal | Linoleic acid /n−6 Polyunsaturated fatty acids | 15−Lipoxygenase/autoxidation | [43,44] |

| 4 | (E)−3−Hexen−1−ol | Eicosapentaenoic acid | 15−Lipoxygenase | [13] |

| 5 | (E)−2−Hexenal | Linolenic acid /n−3 polyunsaturated fatty acids | 15−Lipoxygenase | [13,42] |

| 6 | Heptanal | n−6 Polyunsaturated fatty acids | Autoxidation | [42,43,44] |

| 7 | 1−Octen−3−ol | Arachidonic acid, linoleic acid /n−6 polyunsaturated fatty acids | 12−Lipoxygenase | [42,44] |

| 8 | (Z)−1,5−Octadien−3−one | Eicosapentaenoic acid /n−3 polyunsaturated fatty acids | 12−Lipoxygenase | [13,43] |

| 9 | Nonanal | n−9 Polyunsaturated fatty acids | 12−Lipoxygenase | [42,43] |

| 10 | (E)−2−Nonenal | Linoleic acid, arachidonic acid | 12−Lipoxygenase | [43] |

| 11 | (E,Z)−2,6−Nonadienal | Eicosapentaenoic acid /n−3 polyunsaturated fatty acids | 12−Lipoxygenase | [13,43] |

| 12 | 2,4−Heptadienal (two isomers) | Linolenic acid /n−3 polyunsaturated fatty acids | 12−Lipoxygenase/autoxidation | [43] |

| 13 | 2,4−Decadienal (two isomers) | Linoleic acid | Autoxidation | [45] |

| 14 | Short− and branched−chain fatty acids (e.g., butanoic, 2−/3−methylbutanoic, hexanoic, and octanoic acids) | Fatty acids | Autoxidation | [46] |

| Gas Composition | Microflora |

|---|---|

| Air | S. putrefaciens, Pseudomonas spp. |

| >50% CO2 with O2 | B. thermosphacta, S. putrefaciens |

| 50% CO2 | P. phosphoreum, Lactic acid bacteria |

| 50% CO2 with O2 | P. phosphoreum, Lactic acid bacteria, B. thermosphacta |

| 100% CO2 | Lactic acid bacteria |

| Vacuum packaged | Pseudomonas spp. |

| Compounds | Pseudomonas | Shewanella | Lactic Acid Bacteria (LAB) | Precursor(s) | Flavor Descriptors | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alcohols | ||||||

| 2−Methyl−1−butanol | Y | Y | / | Isoleucine | Malt, wine, onion | [63,64] |

| 3−Methyl−1−butanol | Y | Y | Y | Leucine | Whiskey, malty, burnt | [63,64] |

| Ethanol | Y | Y | Y | Glucose | Alcoholic, ethereal, medical | [63,65] |

| Aldehydes | ||||||

| 2−Methylbutanal | / | / | Y | Isoleucine | Cocoa, coffee, fruit | [63,66] |

| 3−Methylbutanal | / | / | Y | Leucine | Sweet, malty, sour | [63,66] |

| Benzene acetaldehyde | / | / | Y | Phenylalanine | Sweet, honey sweet | [67] |

| Ketones | ||||||

| 3−Hydroxy−2−butanone | / | / | Y | Glucose | Butter, creamy, dairy, milk, fatty | [63,68] |

| 2−Heptanone | Y | Y | / | Fatty acid | Fruity, spicy | [63,69] |

| Esters | ||||||

| Ethyl acetate | NAD | / | Y | Multiple origins | Ethereal, fruit, sweet | [68] |

| Ethyl octanoate | Y | / | NAD | Multiple origins | fruit, fat | [63,70] |

| 3−Methylbutyl acetate | / | / | Y | Multiple origins | Fruit, sweet, banana, ripe | [63,69] |

| Organic acids | ||||||

| Acetic acid | / | Y | Y | Glucose | Pungent sour | [55,63,69] |

| Sulfur compounds | ||||||

| Hydrogen sulfide | / | Y | Y | Cystine, cysteine, methionine | Rotten eggs | [23,69] |

| Methanethiol | Y | Y | / | Methionine, cysteine | Sulfur, gasoline, garlic | [23,49,64] |

| Dimethyl sulfide | Y | Y | / | Methanethiol, methionine, cysteine | Cabbage, sulfur, gasoline | [23,49] |

| Dimethyl disulfide | Y | Y | / | Methionine, cysteine | Onion, cabbage, putrid | [23,63,64] |

| Dimethyl trisulfide | Y | Y | / | Methionine, methanethiol, cysteine | Sulfur, fish, cabbage | [23,69] |

| Nitrogen compounds | ||||||

| Ammonia | NAD | NAD | NAD | Amino acids (e.g., arginine, histidine, tyrosine) | Ammoniacal | [71] |

| Trimethylamine | / | Y | / | Trimethylamine oxide | Fishy, oily, rancid, sweaty | [49,68,71] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wu, T.; Wang, M.; Wang, P.; Tian, H.; Zhan, P. Advances in the Formation and Control Methods of Undesirable Flavors in Fish. Foods 2022, 11, 2504. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods11162504

Wu T, Wang M, Wang P, Tian H, Zhan P. Advances in the Formation and Control Methods of Undesirable Flavors in Fish. Foods. 2022; 11(16):2504. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods11162504

Chicago/Turabian StyleWu, Tianle, Meiqian Wang, Peng Wang, Honglei Tian, and Ping Zhan. 2022. "Advances in the Formation and Control Methods of Undesirable Flavors in Fish" Foods 11, no. 16: 2504. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods11162504

APA StyleWu, T., Wang, M., Wang, P., Tian, H., & Zhan, P. (2022). Advances in the Formation and Control Methods of Undesirable Flavors in Fish. Foods, 11(16), 2504. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods11162504