Trends in Food Preferences and Sustainable Behavior during the COVID-19 Lockdown: Evidence from Spanish Consumers

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Socio-Demographic Factors

2.2. Psychological Factors (Mood)

2.3. Cognitive Factors

2.3.1. Trust in Information Sources

2.3.2. Risk Perceptions and Risk Preference

2.3.3. Knowledge

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data Collection and Questionnaire Design

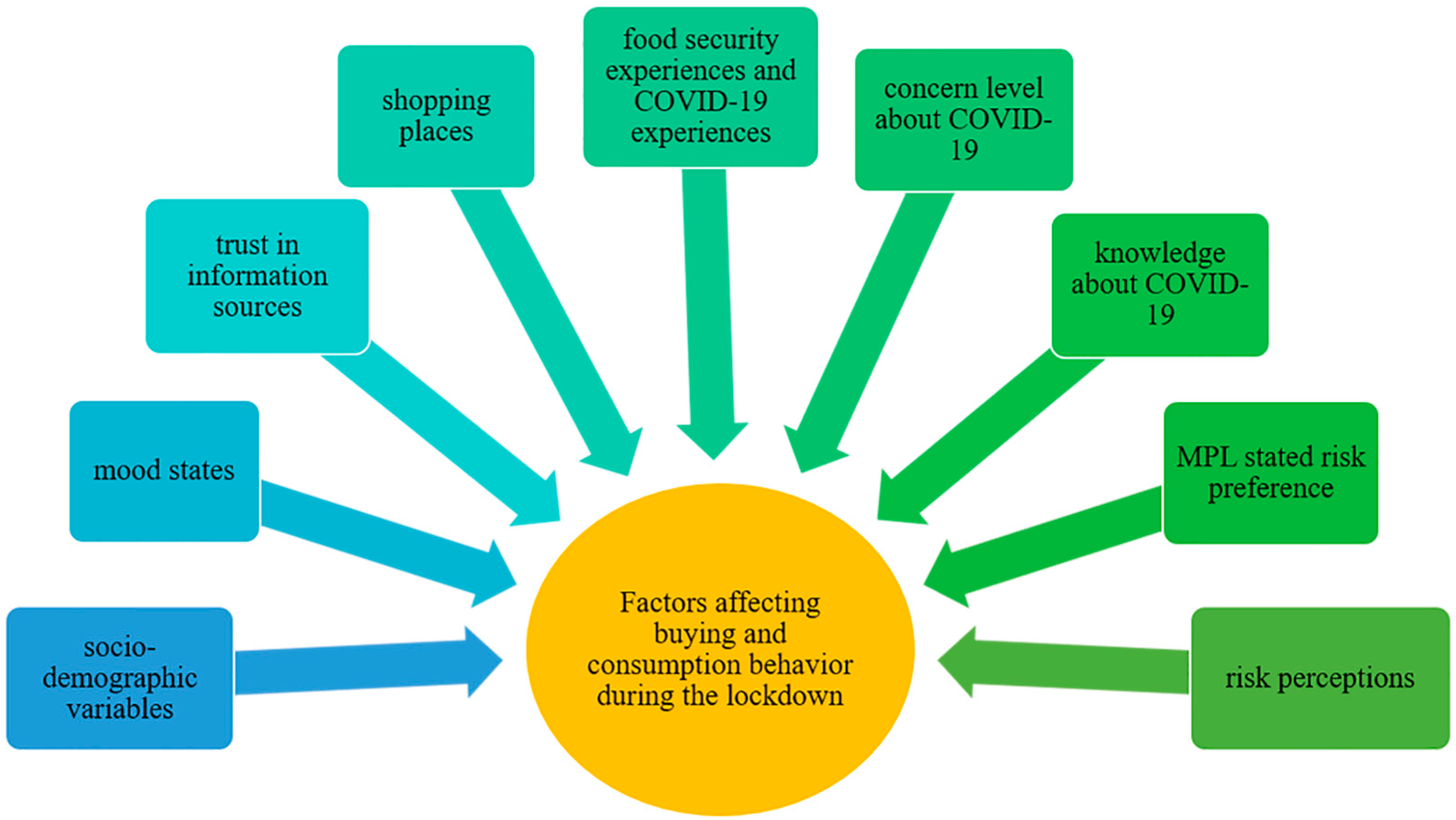

3.2. Independent Variables Included in this Research

3.2.1. Risk Preference

3.2.2. Risk Perceptions

3.2.3. Mood States, Experiences, Concerns, and Shopping Places

3.2.4. Trust in Information Sources and Knowledge

3.3. Measuring Consumers’ Food Preferences and Sustainable Behavior

3.4. Data Analysis

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Results of the Independent Variables Included in the Model

4.2. Results of Consumers’ Food Preferences and Sustainable Behavior

4.2.1. Changes in Total Food Consumption (C) during the Lockdown

4.2.2. Changes in the Total Food Expenditure (E) during the Lockdown

4.2.3. Changes in Purchasing Food with Sustainable Attributes (S) during the Lockdown

4.3. Overall Discussion

5. Conclusions

5.1. Practical Implications

5.2. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chakraborty, I.; Maity, P. COVID-19 outbreak: Migration, effects on society, global environment and prevention. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 728, 138882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laguna, L.; Fiszman, S.; Puerta, P.; Chaya, C.; Tárrega, A. The impact of COVID-19 lockdown on food priorities. Results from a preliminary study using social media and an online survey with Spanish consumers. Food Qual. Prefer. 2020, 86, 104028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coibion, O.; Gorodnichenko, Y.; Weber, M. The Cost of the Covid-19 Crisis: Lockdowns, Macroeconomic Expectations, and Consumer Spending; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Wanberg, C.R. The Individual Experience of Unemployment. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2012, 63, 369–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Alessandro, D.; Gola, M.; Appolloni, L.; Dettori, M.; Fara, G.M.; Rebecchi, A.; Settimo, G.; Capolongo, S. COVID-19 and Living space challenge. Well-being and Public Health recommendations for a healthy, safe, and sustainable housing. Acta Biomed. Atenei Parm. 2020, 91, 61–75. [Google Scholar]

- Scarmozzino, F.; Visioli, F. Covid-19 and the Subsequent Lockdown Modified Dietary Habits of Almost Half the Population in an Italian Sample. Foods 2020, 9, 675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuijten, S. Pandemic Impacts on Consumer food Behaviour. Available online: https://www.eitfood.eu/media/news-pdf/COVID-19_Study_-_European_Food_Behaviours_-_Report.pdf (accessed on 6 April 2021).

- Głąbska, D.; Skolmowska, D.; Guzek, D. Population-Based Study of the Changes in the Food Choice Determinants of Secondary School Students: Polish Adolescents’ COVID-19 Experience (PLACE-19) Study. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scacchi, A.; Catozzi, D.; Boietti, E.; Bert, F.; Siliquini, R. COVID-19 Lockdown and Self-Perceived Changes of Food Choice, Waste, Impulse Buying and Their Determinants in Italy: QuarantEat, a Cross-Sectional Study. Foods 2021, 10, 306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Pérez, C.; Molina-Montes, E.; Verardo, V.; Artacho, R.; García-Villanova, B.; Guerra-Hernández, E.J.; Ruíz-López, M.D. Changes in Dietary Behaviours during the COVID-19 Outbreak Confinement in the Spanish COVIDiet Study. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Hassen, T.; El-Bilali, H.; Allahyari, M.S. Impact of COVID-19 on Food Behavior and Consumption in Qatar. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuen, K.F.; Wang, X.; Ma, F.; Li, K.X. The Psychological Causes of Panic Buying Following a Health Crisis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lins, S.; Aquino, S. Development and initial psychometric properties of a panic buying scale during COVID-19 pandemic. Heliyon 2020, 6, e04746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MAPA Spanish Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food (MAPA). Press Releases, March/April, Madrid, Spain. 2020. Available online: https://www.mapa.gob.es/es/prensa/ultimas-noticias (accessed on 6 April 2021).

- Cranfield, J.A.L. Framing consumer food demand responses in a viral pandemic. Can. J. Agric. Econ. Can. d’Agroecon. 2020, 68, 151–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, V.; Shah, H. An Empirical Analysis into Sentiments, Media Consumption Habits, and Consumer Behaviour during the Coronavirus (COVID-19) Outbreak. Purakala UGC Care J. 2020, 31, 353–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cha, W.M.; Chintagunta, P.K.; Dhar, S.K. Food Purchases during the Great Recession. Kilts Cent. Mark. Chic. Booth Nielsen Dataset Pap. Ser. 2015, 1, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, S.R.; Farrokhnia, R.A.; Meyer, S.; Pagel, M.; Yannelis, C. How Does Household Spending Respond to an Epidemic? Consumption during the 2020 COVID-19 Pandemic. Rev. Asset Pricing Stud. 2020, 10, 834–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Economic Forum. These Charts Show How COVID-19 Has Changed Consumer Spending Around the World. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/05/coronavirus-covid19-consumers-shopping-goods-economics-industry/ (accessed on 6 April 2021).

- Martin-Neuninger, R.; Ruby, M. What Does Food Retail Research Tell Us About the Implications of Coronavirus (COVID-19) for Grocery Purchasing Habits? Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Renzo, L.; Gualtieri, P.; Pivari, F.; Soldati, L.; Attinà, A.; Cinelli, G.; Leggeri, C.; Caparello, G.; Barrea, L.; Scerbo, F.; et al. Eating habits and lifestyle changes during COVID-19 lockdown: An Italian survey. J. Transl. Med. 2020, 18, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mankoff, J.; Matthews, D.; Fussell, S.R.; Johnson, M. Leveraging Social Networks To Motivate Individuals to Reduce their Ecological Footprints. In Proceedings of the 2007 40th Annual Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences (HICSS’07), Big Island, HI, USA, 3–6 January 2007; p. 87. [Google Scholar]

- Tsakiridou, E.; Mattas, K.; Tzimitra-Kalogianni, I. The Influence of Consumer Characteristics and Attitudes on the Demand for Organic Olive Oil. J. Int. Food Agribus. Mark. 2006, 18, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmani, D.; Kallas, Z.; Pappa, M.; Gil, J.M. Are Consumers’ Egg Preferences Influenced by Animal-Welfare Conditions and Environmental Impacts? Sustainability 2019, 11, 6218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Escobar, C.; Kallas, Z.; Gil, J. Consumers’ wine preferences in a changing scenario. Br. Food J. 2018, 120, 18–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Kallas, Z. Meta-analysis of consumers’ willingness to pay for sustainable food products. Appetite 2021, 163, 105239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romeo-Arroyo, E.; Mora, M.; Vázquez-Araújo, L. Consumer behavior in confinement times: Food choice and cooking attitudes in Spain. Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci. 2020, 21, 100226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.-J.; Antonelli, M. Conceptual Models of Food Choice: Influential Factors Related to Foods, Individual Differences, and Society. Foods 2020, 9, 1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lea, E.; Worsley, T. Australians’ organic food beliefs, demographics and values. Br. Food J. 2005, 107, 855–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kriwy, P.; Mecking, R.-A. Health and environmental consciousness, costs of behaviour and the purchase of organic food. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2011, 36, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memery, J.; Angell, R.J.; Megicks, P.; Lindgreen, A. Unpicking motives to purchase locally-produced food: Analysis of direct and moderation effects. Eur. J. Mark. 2015, 49, 1207–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onyango, B.M.; Hallman, W.K.; Bellows, A.C. Purchasing organic food in US food systems: A study of attitudes and practice. Br. Food J. 2007, 109, 399–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Aertsens, J.; Mondelaers, K.; Verbeke, W.; Buysse, J.; Van Huylenbroeck, G. The influence of subjective and objective knowledge on attitude, motivations and consumption of organic food. Br. Food J. 2011, 113, 1353–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gracia Royo, A.; De-Magistris, T. Organic food product purchase behaviour: A pilot study for urban consumers in the South of Italy. Span. J. Agric. Res. 2007, 5, 439–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zepeda, L.; Li, J. Characteristics of Organic Food Shoppers. J. Agric. Appl. Econ. 2007, 39, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Garcia, T.; Grande, I. Determinants of food expenditure patterns among older consumers. The Spanish case. Appetite 2010, 54, 62–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banovic, M.; Barreira, M.M.; Fontes, M.A. The Portuguese Household Food Expenditure: 1990, 1995 and 2000. New Medit 2006, 5, 25. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, A.; Titterington, A.J.; Cochrane, C. Who buys organic food? A profile of the purchasers of organic food in Northern Ireland. Br. Food J. 1995, 97, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babalola, D.A.; Isitor, S.U. Analysis of the determinants of food expenditure patterns among urban households in Nigeria: Evidence from Lagos State. IOSR J. Agric. Vet. Sci. 2014, 7, 71–75. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu, S.-Y.; Chang, C.-C.; Lin, T.T. An analysis of purchase intentions toward organic food on health consciousness and food safety with/under structural equation modeling. Br. Food J. 2016, 118, 200–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Januszewska, R.; Pieniak, Z.; Verbeke, W. Food choice questionnaire revisited in four countries. Does it still measure the same? Appetite 2011, 57, 94–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canetti, L.; Bachar, E.; Berry, E.M. Food and emotion. Behav. Process. 2002, 60, 157–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardi, V.; Leppanen, J.; Treasure, J. The effects of negative and positive mood induction on eating behaviour: A meta-analysis of laboratory studies in the healthy population and eating and weight disorders. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2015, 57, 299–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyman, B. The Nutritional Values and Food Group Characteristics of Foods Preferred during Various Emotions. J. Psychol. 1982, 112, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mennella, J.A.; Pepino, M.Y.; Lehmann-Castor, S.M.; Yourshaw, L.M. Sweet preferences and analgesia during childhood: Effects of family history of alcoholism and depression. Addiction 2010, 105, 666–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mehrabian, A.; Riccioni, M. Measures of Eating-Related Characteristics for the General Population: Relationships with Temperament. J. Pers. Assess. 1986, 50, 610–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evers, C.; Adriaanse, M.; De Ridder, D.T.; Huberts, J.C.D.W. Good mood food. Positive emotion as a neglected trigger for food intake. Appetite 2013, 68, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wansink, B. Environmental Factors that Increase the Food Intake and Consumption Volume of Unknowing Consumers. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2004, 24, 455–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Boggiano, M.M.; Wenger, L.E.; Mrug, S.; Burgess, E.E.; Morgan, P.R. The Kids-Palatable Eating Motives Scale: Relation to BMI and binge eating traits. Eat. Behav. 2015, 17, 69–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Garbarino, E.; Johnson, M.S. The different roles of satisfaction, trust, and commitment in customer relationships. J. Mark. 1999, 63, 70–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pornpitakpan, C. The Persuasiveness of Source Credibility: A Critical Review of Five Decades’ Evidence. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2004, 34, 243–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoque, M.Z.; Alam, M. What determines the purchase intention of liquid milk during a food security crisis? The role of perceived trust, knowledge, and risk. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Thomas, M.S.; Feng, Y. Consumer risk perception and trusted sources of food safety information during the COVID-19 pandemic. Food Control 2021, 130, 108279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobb, A.; Mazzocchi, M.; Traill, W. Modelling risk perception and trust in food safety information within the theory of planned behaviour. Food Qual. Prefer. 2007, 18, 384–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faour-Klingbeil, D.; Osaili, T.M.; Al-Nabulsi, A.A.; Jemni, M.; Todd, E.C. The public perception of food and non-food related risks of infection and trust in the risk communication during COVID-19 crisis: A study on selected countries from the Arab region. Food Control 2021, 121, 107617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arafat, S.Y.; Kar, S.K.; Marthoenis, M.; Sharma, P.; Apu, E.H.; Kabir, R. Psychological underpinning of panic buying during pandemic (COVID-19). Psychiatry Res. 2020, 289, 113061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, T.; Pitafi, A.H.; Aryaa, V.; Wang, Y.; Akhtar, N.; Mubarik, S.; Xiaobei, L. Panic buying in the COVID-19 pandemic: A multi-country examination. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 59, 102357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohrmann, B. Risk perception, risk attitude, risk communication, risk management: A conceptual appraisal. In Proceedings of the International Emergency Management Society Annual Conference, Prague, Czech Republic, 17–19 June 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor-Gooby, P. Varieties of risk. Health Risk Soc. 2002, 4, 109–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, H.; Jung, J.; Kim, J.; Shim, S.W. Cross-Cultural Differences in Perceived Risk of Online Shopping. J. Interact. Advert. 2004, 4, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallowell, M. Safety risk perception in construction companies in the Pacific Northwest of the USA. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2010, 28, 403–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieniak, Z.; Verbeke, W.; Scholderer, J.; Brunsø, K.; Olsen, S.O. Impact of consumers’ health beliefs, health involvement and risk perception on fish consumption: A study in five European countries. Br. Food J. 2008, 110, 898–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.; Paladino, A. Eating clean and green? Investigating consumer motivations towards the purchase of organic food. Australas. Mark. J. 2010, 18, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusk, J.L.; Coble, K. Risk Perceptions, Risk Preference, and Acceptance of Risky Food. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2005, 87, 393–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brucks, M. The Effects of Product Class Knowledge on Information Search Behavior. J. Consum. Res. 1985, 12, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodd, T.H.; Laverie, D.A.; Wilcox, J.F.; Duhan, D.F. Differential Effects of Experience, Subjective Knowledge, and Objective Knowledge on Sources of Information used in Consumer Wine Purchasing. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2005, 29, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Sohaib, M.; Iqbal, S.; Hayat, K.; Khan, A.U.; Rasool, M.F. Evaluation of COVID-19 Disease Awareness and Its Relation to Mental Health, Dietary Habits, and Physical Activity: A Cross-Sectional Study from Pakistan. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2021, 104, 1687–1693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clements, J.M. Knowledge and Behaviors toward COVID-19 among US Residents during the Early Days of the Pandemic: Cross-Sectional Online Questionnaire. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2020, 6, e19161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musche, V.; Bäuerle, A.; Steinbach, J.; Schweda, A.; Hetkamp, M.; Weismüller, B.; Kohler, H.; Beckmann, M.; Herrmann, K.; Tewes, M.; et al. COVID-19-Related Fear and Health-Related Safety Behavior in Oncological Patients. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latip, M.S.A.; Newaz, F.T.; Ramasamy, R.; Tumin, S.A.; Noh, I. How do food safety knowledge and trust affect individual’s green considerations during the covid-19 pandemic in malaysia? Malays. J. Consum. Fam. Econ. 2020, 24, 261–285. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, H.; Deng, F. How to Influence Rural Tourism Intention by Risk Knowledge during COVID-19 Containment in China: Mediating Role of Risk Perception and Attitude. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, M.A.O.; Kallas, Z.; Herrera, S.I.O. Analysis of Farmers’ Stated Risk Using Lotteries and Their Perceptions of Climate Change in the Northwest of Mexico. Agronomy 2018, 9, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Harrison, G.W.; Lau, M.I.; Rutström, E.E. Estimating Risk Attitudes in Denmark: A Field Experiment. Scand. J. Econ. 2007, 109, 341–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bults, M.; Beaujean, D.J.M.A.; de Zwart, O.; Kok, G.; van Empelen, P.; van Steenbergen, J.E.; Richardus, J.H.; Voeten, H.A.C.M. Perceived risk, anxiety, and behavioural responses of the general public during the early phase of the Influenza A (H1N1) pandemic in the Netherlands: Results of three consecutive online surveys. BMC Public Health 2011, 11, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rosi, A.; van Vugt, F.T.; Lecce, S.; Ceccato, I.; Vallarino, M.; Rapisarda, F.; Vecchi, T.; Cavallini, E. Risk Perception in a Real-World Situation (COVID-19): How It Changes From 18 to 87 Years Old. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 646558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brug, J.; Aro, A.R.; Oenema, A.; De Zwart, O.; Richardus, J.H.; Bishop, G.D. SARS Risk Perception, Knowledge, Precautions, and Information Sources, The Netherlands. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2004, 10, 1486–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, M.L.; Leung, S.O. Effects of varying numbers of Likert scale points on factor structure of the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale. Asian J. Soc. Psychol. 2018, 21, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, R.; Schoeneberger, H.; Pfeifer, H.; Preuss, H.-J. The four dimensions of food and nutrition security: Definitions and concepts. SCN News 2000, 20, 20–25. [Google Scholar]

- Gardner, M.P.; Wansink, B.; Kim, J.; Park, S.-B. Better moods for better eating? How mood influences food choice. J. Consum. Psychol. 2014, 24, 320–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillard, J.P.; Peck, E. Affect and persuasion: Emotional responses to public service announcements. Communic. Res. 2000, 27, 461–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, L.C.; Wallner, L.; Kirch, M.A.; Grainger, R.; Attai, D. Online Social Engagement by Cancer Patients: A Clinic-Based Patient Survey. JMIR Cancer 2016, 2, e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Power, M.; Doherty, B.; Pybus, K.; Pickett, K. How COVID-19 has exposed inequalities in the UK food system: The case of UK food and poverty. Emerald Open Res. 2020, 2, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Boylan, J.; Seli, P.; Scholer, A.A.; Danckert, J. Boredom in the COVID-19 pandemic: Trait boredom proneness, the desire to act, and rule-breaking. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2021, 171, 110387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostafa, M.M. Antecedents of Egyptian consumers’ green purchase intentions: A hierarchical multivariate regression model. J. Int. Consum. Mark. 2006, 19, 97–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aday, S.; Aday, M.S. Impact of COVID-19 on the food supply chain. Food Qual. Saf. 2020, 4, 167–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, H.; Park, M.; Hong, K.; Hyun, E. The Impact of an Epidemic Outbreak on Consumer Expenditures: An Empirical Assessment for MERS Korea. Sustainability 2016, 8, 454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Adelaar, T.; Chang, S.; Lancendorfer, K.M.; Lee, B.; Morimoto, M. Effects of Media Formats on Emotions and Impulse Buying Intent. J. Inf. Technol. 2003, 18, 247–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thai, C.L.; Gaysynsky, A.; Falisi, A.; Chou, W.-Y.S.; Blake, K.; Hesse, B.W. Trust in Health Information Sources and Channels, Then and Now: Evidence from the Health Information National Trends Survey (2005–2013). eHealth Curr. Evidence Promises Perils Futur. Dir. 2018, 15, 43–67. [Google Scholar]

- Camporesi, S.; Vaccarella, M.; Davis, M. Investigating Public trust in Expert Knowledge: Narrative, Ethics, and Engagement. J. Bioethical Inq. 2017, 14, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Freimuth, V.S.; Musa, D.; Hilyard, K.; Quinn, S.C.; Kim, K. Trust During the Early Stages of the 2009 H1N1 Pandemic. J. Health Commun. 2014, 19, 321–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Weber, E.U.; Milliman, R.A. Perceived Risk Attitudes: Relating Risk Perception to Risky Choice. Manag. Sci. 1997, 43, 123–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, G.W.; Lau, M.; Rutström, E.; Sullivan, M.B. Eliciting Risk and Time Preferences Using Field Experiments: Some Methodological Issues. Res. Exp. Econ. 2005, 125–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dryhurst, S.; Schneider, C.R.; Kerr, J.; Freeman, A.L.J.; Recchia, G.; van der Bles, A.M.; Spiegelhalter, D.; van der Linden, S. Risk perceptions of COVID-19 around the world. J. Risk Res. 2020, 23, 994–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Informacion Producir Frutas y Verduras Cuesta Ahora un 25% Más Que Antes de la Crisis del Covid-19—Información. Available online: https://www.informacion.es/economia/2020/04/18/producir-frutas-verduras-cuesta-ahora-4692057.html (accessed on 22 February 2021).

- Kasperson, R.E.; Renn, O.; Slovic, P.; Brown, H.S.; Emel, J.; Goble, R.; Kasperson, J.X.; Ratick, S. The Social Amplification of Risk: A Conceptual Framework. Risk Anal. 1988, 8, 177–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Maharjan, K.L.; Joshi, N.P. Determinants of household food security in Nepal: A binary logistic regression analysis. J. Mt. Sci. 2011, 8, 403–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Thompson, S.H. Gender and Racial Diferences in Emotional Eating, Food Addiction Symptoms, and Body Weight Satisfaction among ndergraduates. J. Diabetes Obes. 2015, 2, 93–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Emerson, K.G. Coping with being cooped up: Social distancing during COVID-19 among 60+ in the United States. Rev. Panam. Salud Pública 2020, 44, e81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen-Rodriguez, S.T.; Unger, J.; Spruijt-Metz, D. Psychological Determinants of Emotional Eating in Adolescence. Eat. Disord. 2009, 17, 211–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cameron, L.; Shah, M. Risk-Taking Behavior in the Wake of Natural Disasters. J. Hum. Resour. 2015, 50, 484–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Zhang, H.; Huang, H. Media exposure to COVID-19 information, risk perception, social and geographical proximity, and self-rated anxiety in China. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spanish Statistical Office Unemployment Rates by CCAA. Available online: https://www.ine.es/infografias/tasasepa/desktop/tasas.html?t=0&lang=en (accessed on 22 February 2021).

- Solgaard, H.S.; Yang, Y. Consumers’ perception of farmed fish and willingness to pay for fish welfare. Br. Food J. 2011, 113, 997–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vives, J.M.M.; Jornet-Gibert, M.; Cámara-Cabrera, J.; Esteban, P.L.; Brunet, L.; Delgado-Flores, L.; Camacho-Carrasco, P.; Torner, P.; Marcano-Fernández, F. Spanish HIP-COVID Investigation Group Mortality Rates of Patients with Proximal Femoral Fracture in a Worldwide Pandemic. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Am. Vol. 2020, 102, e69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeżewska-Zychowicz, M.; Plichta, M.; Królak, M. Consumers’ Fears Regarding Food Availability and Purchasing Behaviors during the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Importance of Trust and Perceived Stress. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, N.N.; Khoi, B.H. An Empirical Study about the Intention to Hoard Food during COVID-19 Pandemic. Eurasia J. Math. Sci. Technol. Educ. 2020, 16, em1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Borsellino, V.; Kaliji, S.; Schimmenti, E. COVID-19 Drives Consumer Behaviour and Agro-Food Markets towards Healthier and More Sustainable Patterns. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tham, K.W.; Dastane, O.; Johari, Z.; Ismail, N.B. Perceived Risk Factors Affecting Consumers’ Online Shopping Behaviour. J. Asian Financ. Econ. Bus. 2019, 6, 246–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Kallas, Z.; Rahmani, D. Did the COVID-19 lockdown affect consumers’ sustainable behaviour in food purchasing and consumption in China? Food Control 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köster, E.P.; Mojet, J. From mood to food and from food to mood: A psychological perspective on the measurement of food-related emotions in consumer research. Food Res. Int. 2015, 76, 180–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil Roig, J.M.; Gracia Royoz, A.; Sánchez García, M. Market segmentation and willingness to pay for organic products in Spain. Int. Food Agribus. Manag. Rev. 2000, 3, 207–226. [Google Scholar]

- Bhaskaran, S.; Polonsky, M.; Cary, J.; Fernandez, S. Environmentally sustainable food production and marketing. Br. Food J. 2006, 108, 677–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vidal-Mones, B.; Barco, H.; Diaz-Ruiz, R.; Fernandez-Zamudio, M.-A. Citizens’ Food Habit Behavior and Food Waste Consequences during the First COVID-19 Lockdown in Spain. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pak, H.; Süsen, Y.; Nazlıgül, M.D.; Griffiths, M. The Mediating Effects of Fear of COVID-19 and depression on the association between intolerance of uncertainty and emotional eating during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Turkey. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2021, 19, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, L.; Liu, J.; Yuan, Y.C.; Burns, K.S.; Lu, E.; Li, D. Source Trust and COVID-19 Information Sharing: The Mediating Roles of Emotions and Beliefs About Sharing. Health Educ. Behav. 2021, 48, 132–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dutta-Bergman, M. Trusted Online Sources of Health Information: Differences in Demographics, Health Beliefs, and Health-Information Orientation. J. Med. Internet Res. 2003, 5, e21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Socio-Demographic Variables | Percentage (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 49.0 |

| Female | 51.0 | |

| Age | 18–39 years | 28.1 |

| 40–59 years | 36.9 | |

| More than 60 years | 35.0 | |

| Monthly household income before the lockdown | <999 euros | 10.5 |

| 1000–3000 euros | 56.1 | |

| >3001 euros | 22.0 | |

| “I prefer not to answer” | 11.4 | |

| Monthly household income during the lockdown | <999 euros | 19.0 |

| 1000–3000 euros | 53.6 | |

| >3001 euros | 15.9 | |

| “I prefer not to answer” | 11.5 | |

| Stated health status | Unhealthy | 43.0 |

| Healthy | 57.0 | |

| Household size | 1 person | 10.7 |

| 2 persons | 36.3 | |

| 3 persons | 27.0 | |

| 4 persons | 20.3 | |

| 5 persons | 4.0 | |

| 6 persons or more | 1.7 | |

| Family structure | There are children aged 0–6 years | Yes (13.5), No (86.5) |

| There are children aged 7–12 years | Yes (15.5), No (84.5) | |

| There are adults over 70 years | Yes (14.1), No (85.9) | |

| None of the above | Yes (61.2), No (38.8) | |

| Place of residence | Urban place | 71.8 |

| Suburban place | 14.8 | |

| Rural place | 13.4 | |

| Employment status | Student | 2.3 |

| Full time (without variation) | 24.4 | |

| Full time (telecommuting) | 16.5 | |

| ERTE a (partial or total) | 10.8 | |

| A homemaker | 5.2 | |

| Sick leave | 2.1 | |

| Unemployed | 15.0 | |

| Retired | 21.5 | |

| Unable to work | 2.2 | |

| Variables | Percentage (%) | Scales |

| Knowledge | ||

| Subjective knowledge level | 77.26 | 1–100% |

| Objective knowledge level | 67.44 | 1–100% |

| Risk preference | ||

| Risk-loving | 20.7 | |

| Risk-neutral | 13.6 | |

| Risk-averse | 65.7 | |

| Experiences | ||

| Food security experiences | ||

| Experienced food shortages | Yes 29.2; No 70.8 | |

| Experienced higher food prices | Yes 60.7; No 39.3 | |

| Experienced neither | Yes 28.4; No 71.6 | |

| COVID-19 experiences | ||

| Q. Have you contracted the COVID-19 virus? | ||

| Yes. I tested positive for the COVID-19 virus. | 1.5 | |

| No, I had the symptoms, but the test result was negative. | 5.1 | |

| No. I did not have the symptoms, so I did not opt for a test. | 71.7 | |

| I don’t know. I had the symptoms but did not have access to tests. | 21.7 | |

| Q. Do you know someone who has been diagnosed or died due to the COVID-19 virus? | ||

| Members of my family | Yes 19.0; No 81.0 | |

| Friends | Yes 26.4; No 73.6 | |

| Neighbors | Yes 14.3; No 85.7 | |

| Friends of my friends | Yes 25.6; No 74.4 | |

| Colleagues | Yes 6.6; No 93.4 | |

| No, I don’t know any person | Yes 37.2; No 62.8 | |

| Variables | Mean (SD) | Scales |

| Concern level about COVID-19 | 4.77 (1.70) | 7-point Likert scale |

| Food security risk perception | ||

| The probability of food shortages in the next 6 months | 2.34 (1.49) | 7-point Likert scale |

| The probability of higher food prices in the next 6 months | 5.01 (1.61) | 7-point Likert scale |

| Risk perception of COVID-19 | ||

| The severity of one’s health condition will be if they contract COVID-19 | 6.04 (2.40) | 11-point Likert scale |

| The probability of contracting COVID-19 | 2.65 (0.95) | 5-point Likert scale |

| Trust in information sources | ||

| Government | 2.52 (1.27) | 5-point Likert scale |

| Social media | 2.70 (1.09) | |

| Health professionals (e.g., doctor) | 4.27 (0.82) | |

| Family, friends, and colleagues | 2.91 (1.04) | |

| Scientists | 4.13 (0.91) | |

| News (e.g., papers, TV, radio) | 1.90 (0.94) |

| Category | Percentage | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Food Consumption | Expenditure | Sustainable Food | |

| Increase (Y = 1) | 36.0% | 52.6% | 37.8% |

| Did not increase (Y = 0) | 63.8% | 47.4% | 55.2% |

| Missing | 0.2% | Null | 7.0% |

| Significant Variables | Reference Category | Beta (B) | p-Value | Exp (B) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||||

| Female | Male | 0.332 | 0.063 | 1.394 |

| Age | ||||

| 40–59 years old | 18–39 years old | −0.622 | 0.003 | 0.537 |

| More than 60 years old | −0.977 | 0.001 | 0.376 | |

| Monthly household income | ||||

| Income (before the lockdown) >3000 euros | <999 euros | 1.086 | 0.021 | 2.963 |

| Employment status | ||||

| ERTE (partial or total) | Student | −1.061 | 0.080 | 0.346 |

| Sick leave | −2.142 | 0.017 | 0.117 | |

| Unemployed | −1.020 | 0.087 | 0.361 | |

| Unable to work | −1.979 | 0.023 | 0.138 | |

| Place of residence | ||||

| Living in rural place | Urban | −0.437 | 0.077 | 0.646 |

| Risk preference | ||||

| Risk-averse | Risk-loving | −0.365 | 0.085 | 0.694 |

| Experiences | ||||

| Did not experience food shortages or price increase | Experienced | −0.785 | 0.026 | 0.456 |

| “I know a friend of my friends has been diagnosed or died due to COVID-19” | Do not know | 0.564 | 0.011 | 1.759 |

| Shopping places | ||||

| Specialized food stores (before the lockdown) | Supermarkets | −0.750 | 0.021 | 0.473 |

| Farmer’s market/open markets (before the lockdown) | −1.480 | 0.052 | 0.228 | |

| Trust in information sources | ||||

| Health professionals were perceived to be a little trustworthy | Not at all | −3.078 | 0.042 | 0.046 |

| Food security risk perception | ||||

| A little unlikely to face food shortages in the next 6 months | Very unlikely | 0.643 | 0.003 | 1.903 |

| Risk perception of COVID-19 | ||||

| Somewhat serious if contracting in the next 6 months | Not at all | 1.595 | 0.003 | 4.930 |

| Very serious if contracting in the next 6 months | 1.596 | 0.012 | 4.934 | |

| Percentage of correct classification Hosmer–Lemeshow’s goodness of fit | 75.2% | |||

| 0.353 | ||||

| Significant Variables | Reference Category | Beta (B) | p-Value | Exp (B) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||||

| Female | Male | −0.458 | 0.008 | 0.632 |

| Age | ||||

| 40–59 years old | 18–39 years old | −0.572 | 0.006 | 0.564 |

| More than 60 years old | −0.675 | 0.015 | 0.509 | |

| Employment status | ||||

| Sick leave | Student | −1.617 | 0.054 | 0.199 |

| Unable to work | −1.485 | 0.060 | 0.226 | |

| Family structure | ||||

| There are children aged 7–12 years in the household | No | 0.797 | 0.079 | 2.218 |

| Experiences | ||||

| Experienced food shortages during the lockdown | Did not | 0.524 | 0.017 | 1.688 |

| Did not have symptoms, so did not test | Tested positive | −1.265 | 0.078 | 0.282 |

| Did not know anyone who has been diagnosed or died due to COVID-19 | Knew someone | −0.784 | 0.002 | 0.457 |

| Shopping places | ||||

| Buy food on retailers’ websites during the lockdown | Supermarkets | 1.520 | 0.015 | 4.574 |

| Mood | ||||

| Feel a little reassured | None of this feeling | 0.794 | 0.004 | 2.213 |

| Feel moderately reassured | 0.582 | 0.044 | 1.789 | |

| Feel moderately angry | −0.859 | 0.017 | 0.424 | |

| Feel a great deal of angry | −0.722 | 0.095 | 0.486 | |

| Risk preference | ||||

| Risk-neutral | Risk-loving | −0.505 | 0.066 | 0.604 |

| Risk-averse | −0.528 | 0.009 | 0.590 | |

| Trust in information sources | ||||

| Government information regarding COVID-19 was perceived to be a little trustworthy | Not trustworthy at all | −0.425 | 0.092 | 0.654 |

| News information regarding COVID-19 was perceived to be very trustworthy | −1.021 | 0.030 | 0.360 | |

| Food security risk perception | ||||

| A little unlikely to face food shortages in the next 6 months | Very unlikely | 0.543 | 0.036 | 1.722 |

| Risk perception of COVID-19 | ||||

| A little unlikely to contract COVID-19 | Very unlikely | 0.819 | 0.004 | 2.268 |

| Financial risk perception | ||||

| Feel threatened moderately about financial situation | Not at all | −0.836 | 0.033 | 0.434 |

| Feel threatened considerably about financial situation | −0.981 | 0.035 | 0.375 | |

| Feel threatened a great deal about financial situation | −1.502 | 0.009 | 0.223 | |

| Knowledge regarding COVID-19 | ||||

| A higher level of objective knowledge | 0.944 | 0.075 | 2.570 | |

| Percentage of correct classification | 70.3% | |||

| Hosmer–Lemeshow’s goodness of fit | 0.311 | |||

| Significant Variables | Reference Category | Beta (B) | p-Value | Exp (B) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Household size | ||||

| Households with 5 members | 1 member | 0.936 | 0.066 | 2.551 |

| Risk preference | ||||

| Risk-averse | Risk-loving | −0.403 | 0.058 | 0.668 |

| Shopping places | ||||

| Specialized food stores (before the lockdown) | Supermarkets | −0.710 | 0.028 | 0.492 |

| Mood | ||||

| Feel considerably reassured | None of this feeling | 0.773 | 0.036 | 2.166 |

| Feel moderately angry | −0.953 | 0.010 | 0.386 | |

| Trust in information sources | ||||

| Government information regarding COVID-19 was perceived to be very trustworthy | Not at all | 0.481 | 0.095 | 1.618 |

| Food security risk perception | ||||

| A little unlikely to face food shortages in the next 6 months | Very unlikely | 0.369 | 0.082 | 1.446 |

| A little likely to face food shortages in the next 6 months | 1.152 | 0.064 | 3.163 | |

| Risk perception of COVID-19 | ||||

| A little unlikely to contract COVID-19 | Very unlikely | 0.748 | 0.015 | 2.113 |

| Financial risk perception | ||||

| Feel threatened moderately about financial situation | Not at all | −0.675 | 0.093 | 0.509 |

| Feel threatened a great deal about financial situation | −1.125 | 0.051 | 0.325 | |

| Percentage of correct classification | 73.0% | |||

| Hosmer–Lemeshow’s goodness of fit | 0.095 | |||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, S.; Kallas, Z.; Rahmani, D.; Gil, J.M. Trends in Food Preferences and Sustainable Behavior during the COVID-19 Lockdown: Evidence from Spanish Consumers. Foods 2021, 10, 1898. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods10081898

Li S, Kallas Z, Rahmani D, Gil JM. Trends in Food Preferences and Sustainable Behavior during the COVID-19 Lockdown: Evidence from Spanish Consumers. Foods. 2021; 10(8):1898. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods10081898

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Shanshan, Zein Kallas, Djamel Rahmani, and José Maria Gil. 2021. "Trends in Food Preferences and Sustainable Behavior during the COVID-19 Lockdown: Evidence from Spanish Consumers" Foods 10, no. 8: 1898. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods10081898

APA StyleLi, S., Kallas, Z., Rahmani, D., & Gil, J. M. (2021). Trends in Food Preferences and Sustainable Behavior during the COVID-19 Lockdown: Evidence from Spanish Consumers. Foods, 10(8), 1898. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods10081898