Photocatalytic Antibacterial Mechanism and Biotoxicity Trade-Off of Metal-Doped M-ZIF-8 (M=Co, Cu): Progress and Challenges

Abstract

1. Introduction

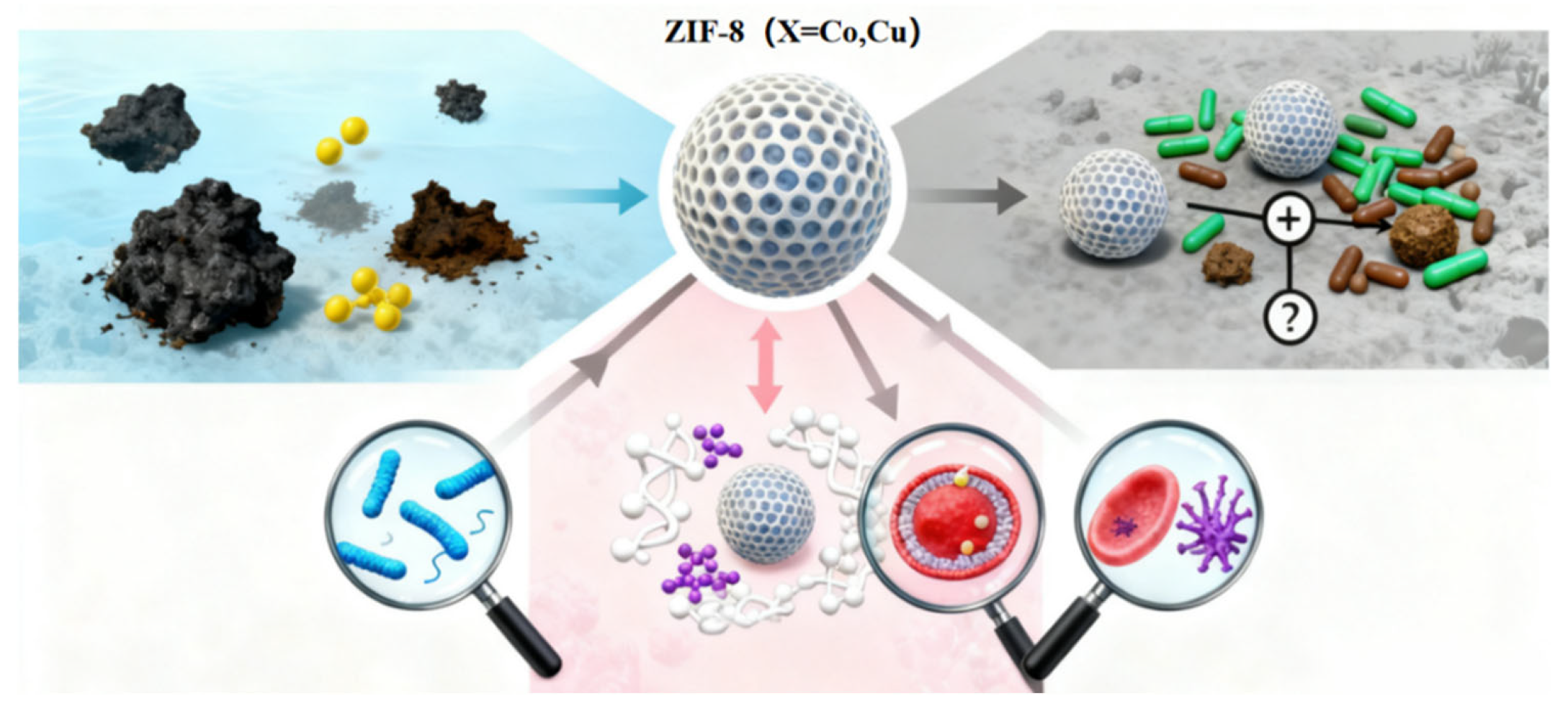

2. Material Properties and Antibacterial Mechanism of M-ZIF-8 (M=Co, Cu)

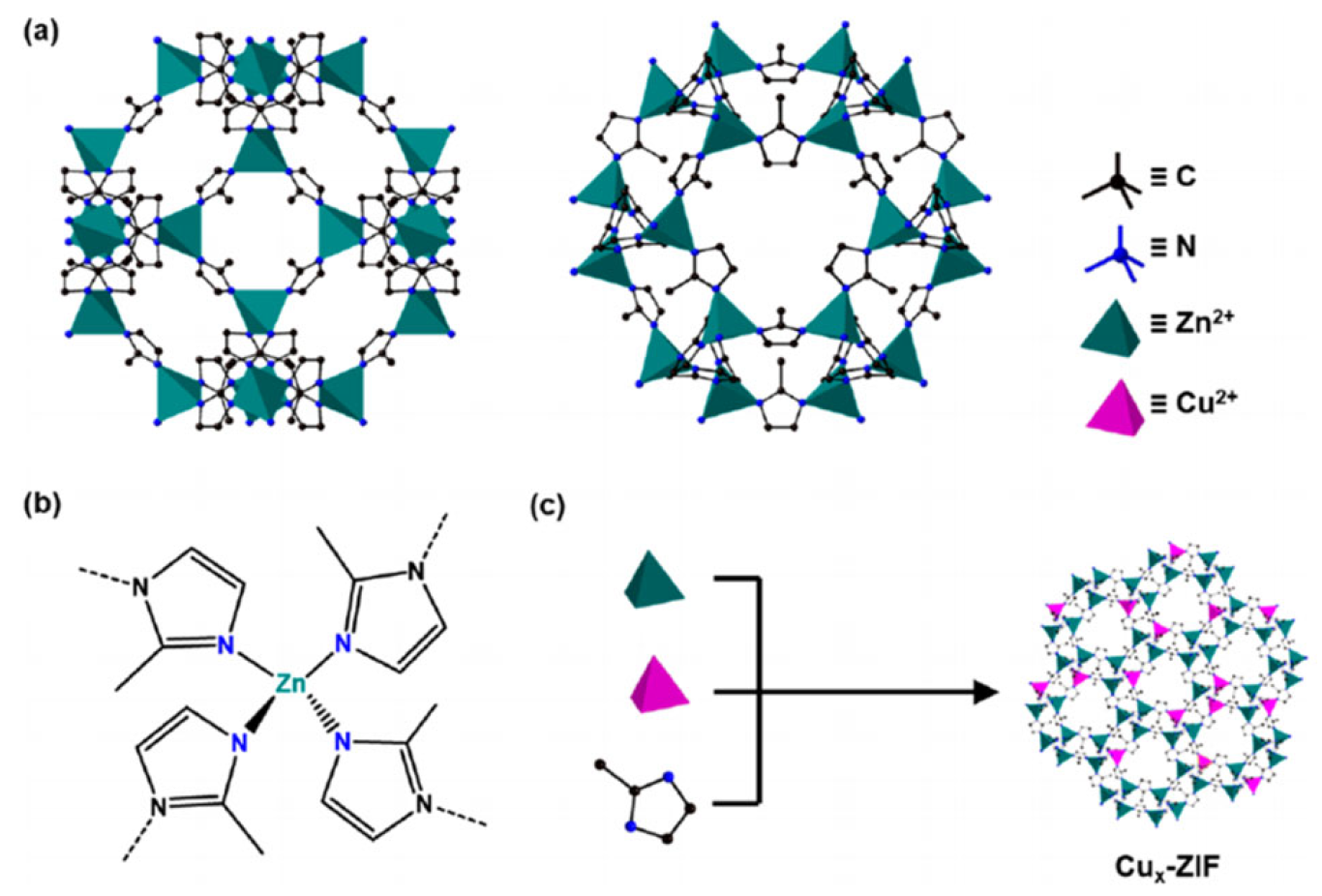

2.1. Material Design Principles

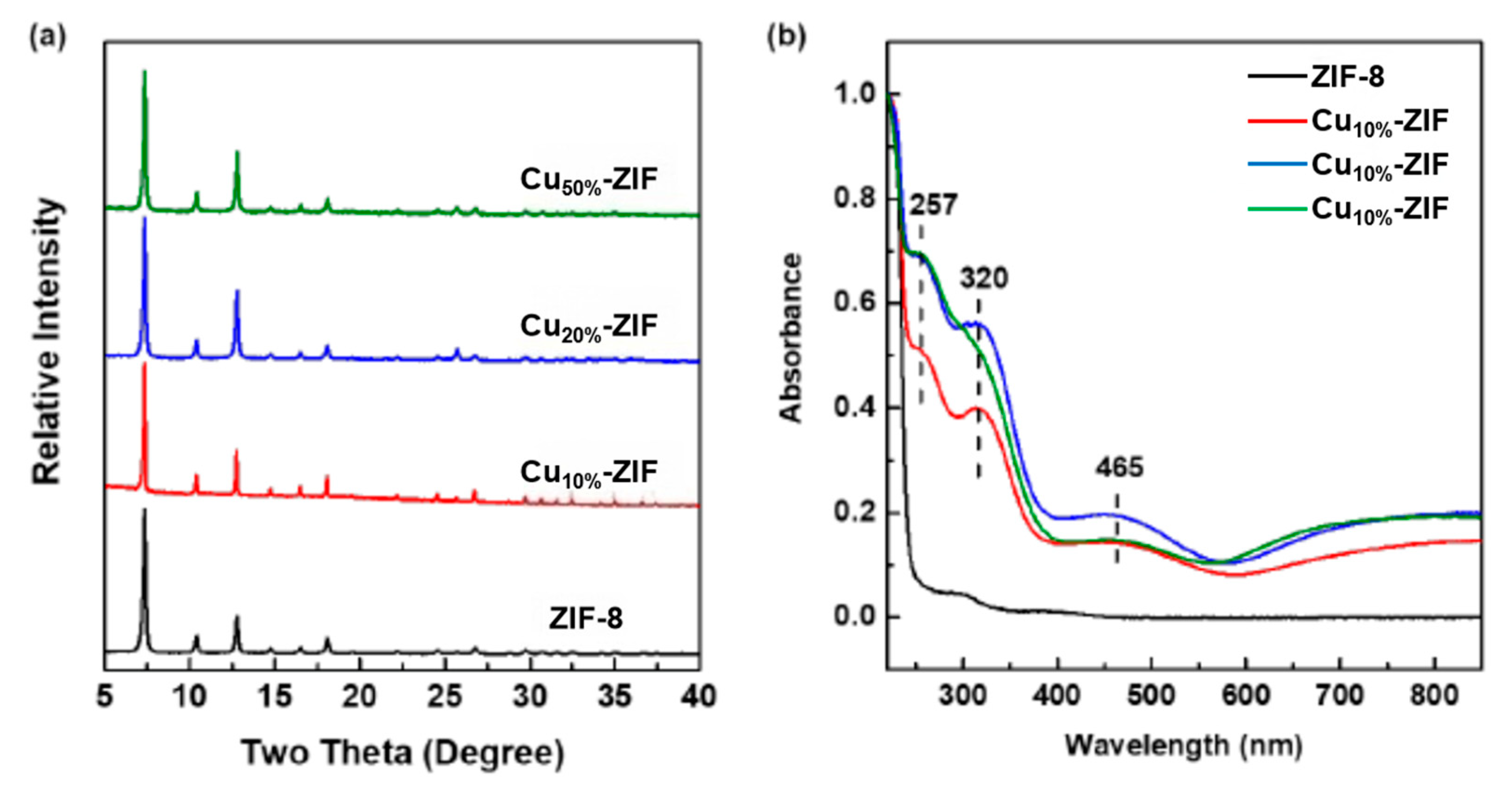

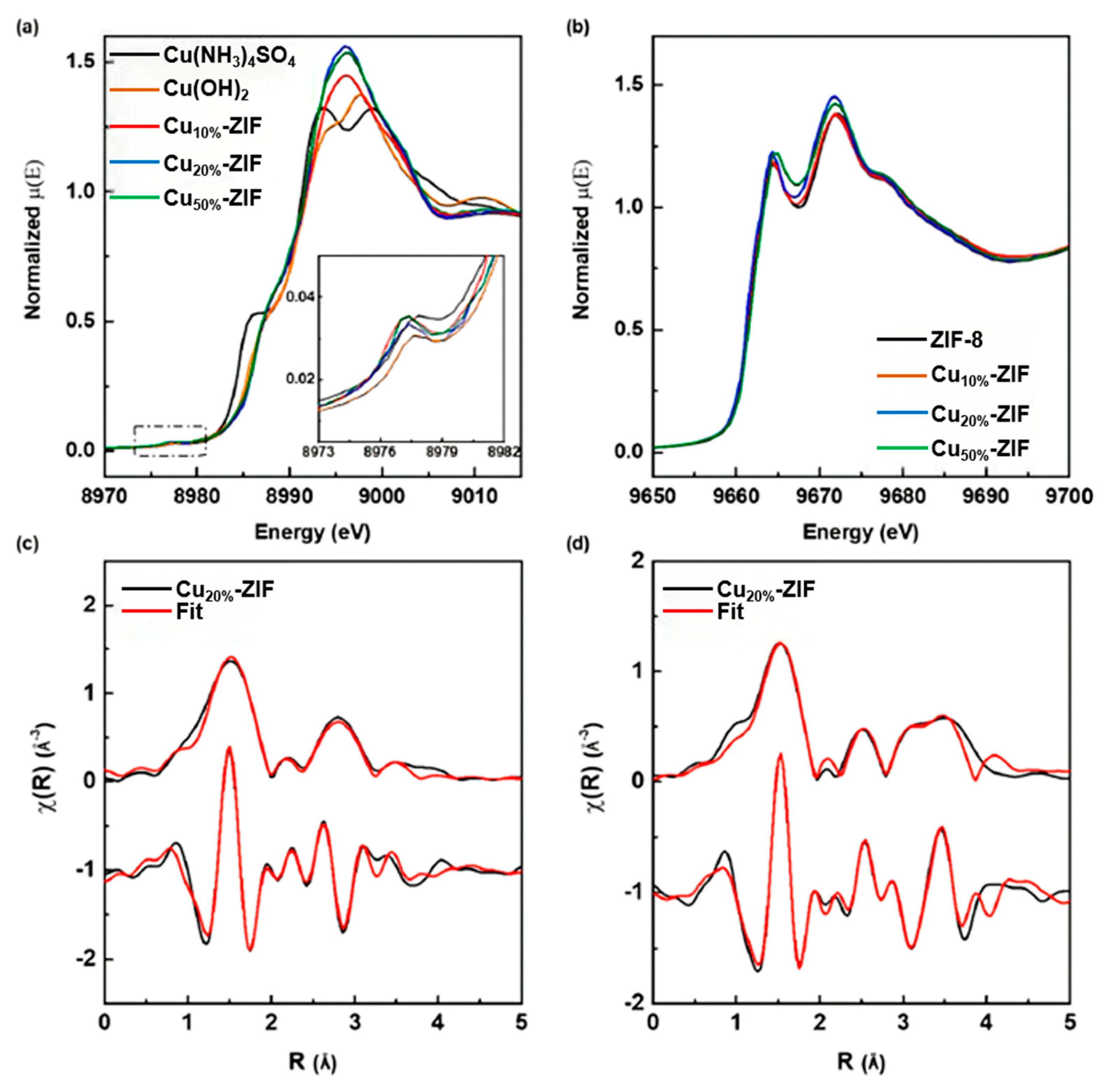

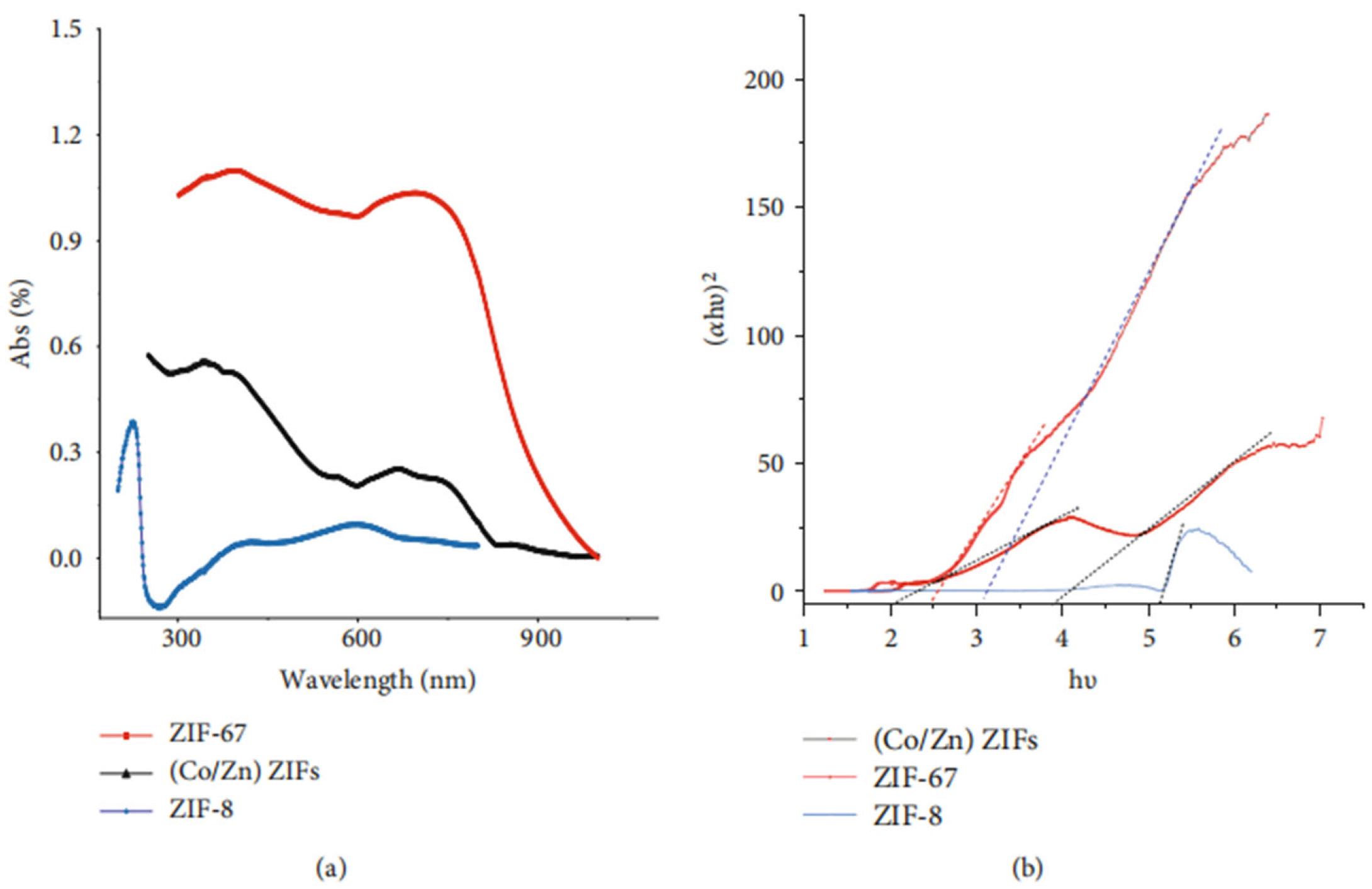

2.1.1. Light Absorption and Carrier Separation (Co/Cu Doping Effect)

2.1.2. Regulatory Mechanisms of Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) Generation

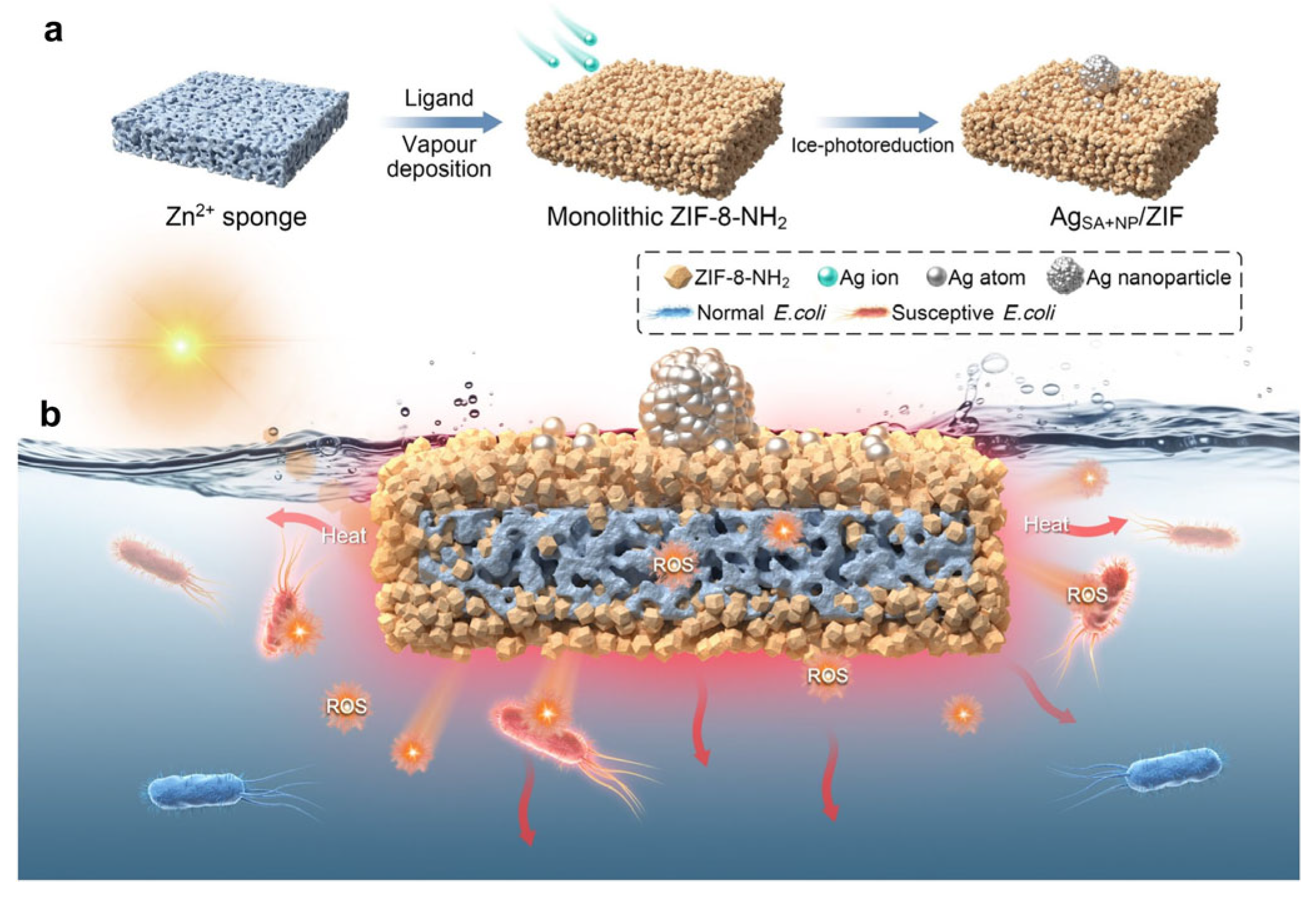

2.1.3. Synergistic Antibacterial Effects of Metal Ion Controlled-Release

2.1.4. Cobalt and Copper: Distinct Photocatalytic Roles

2.2. Antimicrobial Action Pathway

2.2.1. ROS-Mediated Microbial Damage

2.2.2. Disruption of Metal Ion Metabolism

2.2.3. Material–Microorganism Interface Interactions

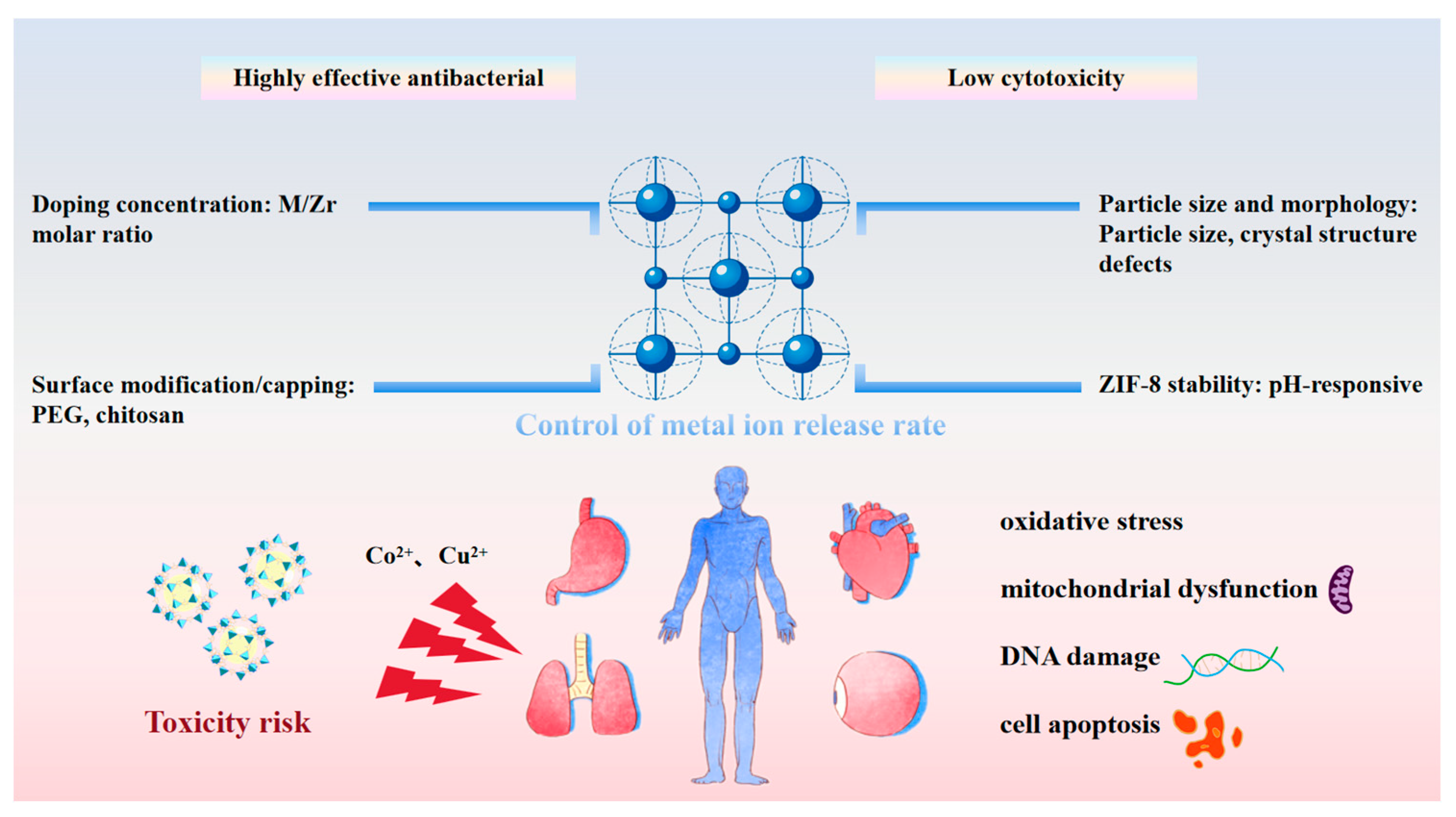

3. Biological Toxicity Mechanisms and Safety Challenges

3.1. Toxicity Manifestation Dimension

3.1.1. Microbial Selectivity

3.1.2. Mammalian Cell Cytotoxicity

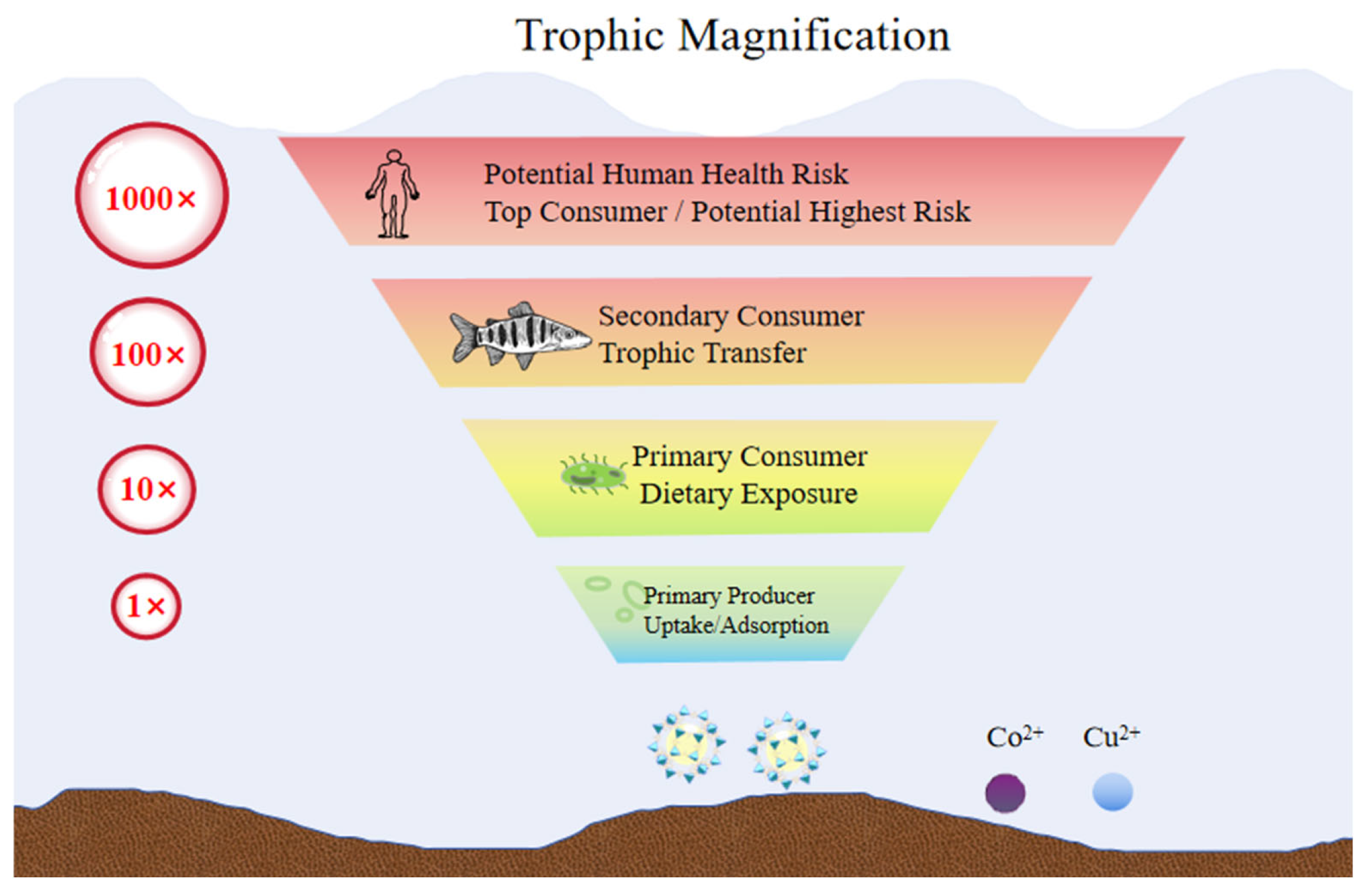

3.1.3. Ecotoxicity

3.2. Key Toxicity Mechanisms

3.2.1. Dose–Response Relationship of Metal Ion Leaching

3.2.2. Physical Damage from Nanoparticles

3.2.3. Long-Term Exposure to Genetic Toxicity

3.2.4. Environmental Persistence and Ecological Accumulation Risk

3.2.5. Key Issues and Future Outlook

4. Performance Optimization and Security Control Strategies

4.1. Current Material Optimization and Safety Regulation Strategies

4.1.1. Material Design Optimization

4.1.2. Application Scenario Adaptation

4.1.3. Safety Evaluation System

5. Future Challenges and Research Directions

5.1. Challenges in In-Depth Mechanism Research

5.2. Development of Smart Materials

5.3. Pathways to Standardization and Industrialization

5.4. Summary and Outlook

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tiwana, G.; Cock, I.E.; Cheesman, M.J. Phytochemistry, antibacterial and toxicity properties of Phyllanthus emblica linn fruit extracts against gastrointestinal pathogens and their interactions with antibiotics. Pharmacol. Res.-Nat. Prod. 2025, 9, 100386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghariani, B.; Zouari-Mechichi, H.; Alessa, A.H.; Alqahtani, H.; Alsaigh, A.A.; Mechichi, T. Biotransformation of Antibiotics by Coriolopsis gallica: Degradation of Compounds Does Not Always Eliminate Their Toxicity. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.; Chen, Y.; Cheng, F.; Yang, H.; Qu, J.; Zhang, Y.-N.; Peijnenburg, W.J. Hydrophilicity-dependent photodegradation of antibiotics in ice: Freeze-concentration effects and dissolved organic matter interactions drive divergent kinetics, pathways and toxicity. Water Res. 2025, 286, 124277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanveer, R.; Neale, P.A.; Melvin, S.D.; Leusch, F.D. Application of an extended bacterial toxicity assay to differentiate antibiotics from other contaminants in environmental mixtures. Environ. Res. 2025, 285, 122310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guleria, A.; Fatima, N.; Shukla, A.; Raj, R.; Sahu, C.; Prasad, N.; Pathak, A.; Kumar, D. Synergistic Potential of Curcumin–Vancomycin Therapy in Combating Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus Infections: Exploring a Novel Approach to Address Antibiotic Resistance and Toxicity. Microb. Drug Resist. 2025, 31, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panah, Z.A.; Shahbazi, A.; Bijari, M.; Dehghan, R.; Nadi, A. Controlled atmosphere synthesis of g-C3N4 for enhanced antibacterial and photocatalytic removal of antibiotics and COD from real textile wastewater. J. Water Process. Eng. 2025, 79, 108921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu, N.-N.; Van Tran, B.; Ladhari, S.; Saidi, A.; Assadi, A.A.; Nguyen-Tri, P. Phase transformation-induced intimate Ag deposition in Ag-TiO2 hybrids for enhanced photocatalytic antibacterial performance. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 524, 169720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gálvez-Barbosa, S.; Bretado, L.A.; Salinas-Delgado, Y.; González, L.A. Photocatalytic performance and antibacterial activity of dumbbell-shaped ZnO with flower-like tips synthesized via the hydrothermal method. Solid State Commun. 2025, 406, 116191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathew, S.; Xavier, S.; Thomas, S. Facile nanosynthesis of ZnCuTiO4: Dual performance in photocatalytic and antibacterial activity. Phys. Lett. A 2025, 563, 131049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Pan, T.; Gu, Y.; Yan, P.; Hou, F.; Zhang, S.; Wei, W.; Li, X.; Lai, W.-Y. Redox-mediated stabilization of ultrasmall Au25 nanoclusters in amine-functionalized MOF for robust photocatalytic antibacterial applications. Sci. China Mater. 2025, 68, 2347–2357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doan, T.D.; Vu, N.-N.; Hoang, T.L.G.; Nguyen-Tri, P. Metal-organic framework (MOF)-based materials for photocatalytic antibacterial applications. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2024, 523, 216298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manivel, C.M.; Zheng, A.L.T.; Kannan, R.; Seenivasagam, S.; Hin, T.Y.Y.; Boonyuen, S.; Lease, J.; Andou, Y.; Tan, K.B. ZIF-8/graphene composite for photocatalytic degradation under low intensity UV irradiation and antibacterial applications. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 33875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wang, H.; Zhang, J.; Han, N.; Ma, W.; Zhang, D.; Yao, M.; Wang, X.; Chen, Y. Peroxidase-like active Cu-ZIF-8 with rich copper(I)-nitrogen sites for excellent antibacterial performances toward drug-resistant bacteria. Nano Res. 2024, 17, 7427–7435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Q.; Yao, H.; Wang, F.; Gu, Z.; Yang, X.; Zhao, Y.; Pang, H.; Wang, D.-A.; Chong, H. Curcumin-Encapsulated Co-ZIF-8 for Ulcerative Colitis Therapy: ROS Scavenging and Macrophage Modulation Effects. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 30571–30582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Kanchanakungwankul, S.; Bhaumik, S.; Ma, Q.; Ahn, S.; Truhlar, D.G.; Hupp, J.T. Bioinspired Cu(II) Defect Sites in ZIF-8 for Selective Methane Oxidation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023, 145, 22019–22030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikuno, T.; Zheng, J.; Vjunov, A.; Sanchez-Sanchez, M.; Ortuño, M.A.; Pahls, D.R.; Fulton, J.L.; Camaioni, D.M.; Li, Z.; Ray, D.; et al. Methane Oxidation to Methanol Catalyzed by Cu-Oxo Clusters Stabilized in NU-1000 Metal–Organic Framework. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 10294–10301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borfecchia, E.; Lomachenko, K.A.; Giordanino, F.; Falsig, H.; Beato, P.; Soldatov, A.V.; Bordiga, S.; Lamberti, C. Revisiting the nature of Cu sites in the activated Cu-SSZ-13 catalyst for SCR reaction. Chem. Sci. 2015, 6, 548–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alkallas, F.H.; Trabelsi, A.B.G.; Alraddadi, S.; Hassan, A.; Ali, A.S.; Aboraia, A.M. Influence of cobalt doping on the structural, morphological, and optical properties of ZIF-8 thin films. Opt. Mater. 2025, 167, 117364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, B.; Chen, J.; Zhu, L.; Zhuang, Z.; Hu, X.; Zhu, C.; Zhao, S.; Shu, K.; Dang, H.; Gao, J.; et al. Tuning Co–Zn bimetallic synergy in ZIF-67@ZIF-8 catalysts for selective photothermal CO2 reduction: Mechanistic insights and performance optimization. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2025, 15, 4550–4566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khang, L.H.; Thao, N.N.P.; Hien, N.T.T.; To, T.C.; Diep, L.T.H.; Son, L.V.T.; Lien, P.; Nguyen, V.T.; Khieu, D.Q. Zinc/Cobalt-Based Zeolite Imidazolate Frameworks for Simultaneously Degrading Dye and Inhibiting Bacteria. J. Nanomater. 2022, 2022, 8630685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostad, M.I.; Shahrak, M.N.; Galli, F. The effect of different reaction media on photocatalytic activity of Au- and Cu-decorated zeolitic imidazolate Framework-8 toward CO2 photoreduction to methanol. J. Solid State Chem. 2022, 315, 123514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wang, H.; Cheng, J.; Li, H.; Wu, X.; Zhang, D.; Shi, X.; Zhang, J.; Han, N.; Chen, Y. Initiative ROS generation of Cu-doped ZIF-8 for excellent antibacterial performance. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 466, 143201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Shu, Z.; Sun, H.; Yan, L.; Peng, C.; Dai, Z.; Yang, L.; Fan, L.; Chu, Y. Cu(II)@ZIF-8 nanoparticles with dual enzyme-like activity bound to bacteria specifically for efficient and durable bacterial inhibition. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2022, 611, 155599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Zhu, J.; Wang, K.; Yan, X.; Xu, L.; Zhang, X.; Ding, H.; Yang, P.; Hu, S.; Xie, R. Engineered-Doping Strategy for Self-Sufficient Reactive Oxygen Species Blossom to Amplify Ferroptosis/Cuproptosis Sensibilization in Hepatocellular Carcinoma Treatment. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2405383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, S.; Zhang, X.; Jiang, F.; Guo, Q.; Jiang, P.; Liu, Y. “Multi-in-One” Yolk-Shell Structured Nanoplatform Inducing Pyroptosis and Antitumor Immune Response Through Cascade Reactions. Small 2024, 20, e2400254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.; Lai, D.; Cao, W.; Bao, Z.; Zhao, T.; Wang, C.; Liu, Y.; Yang, J. Easily Coating Zeolitic Imidazolate Framework (ZIF-8) with Basic Magnesium Hypochlorite (BMH) Achieves an Efficient Antibacterial Strategy. J. Inorg. Organomet. Polym. Mater. 2025, 35, 7060–7075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, D.; Liu, X.; Wu, S. Metal organic framework-based antibacterial agents and their underlying mechanisms. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2022, 51, 7138–7169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shams, S.; Ahmad, W.; Memon, A.H.; Shams, S.; Wei, Y.; Yuan, Q.; Liang, H. Cu/H3BTC MOF as a potential antibacterial therapeutic agent against Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli. New J. Chem. 2020, 44, 17671–17678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, X.; Huang, Q.; Bian, Z.; Zhang, W.; Su, B.; Zhang, H. Mechanistic Study on Orpiment Pigment Discoloration Induced by Reactive Oxygen Species. Molecules 2025, 30, 3318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.-S.; Chen, Y.; Dong, C.; Wang, Z.-Y.; Cai, J.; Zhao, X.; Mo, H.-L.; Zang, S.-Q. Copper doping boosts the catalase-like activity of atomically precise gold nanoclusters for cascade reactions combined with urate oxidase in the ZIF-8 matrix. Inorg. Chem. Front. 2024, 11, 3465–3473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Ma, M.-W.; Cai, S.-Z.; He, K.-L.; Tan, L.-F.; Cheng, K.; Fan, J.-X.; Dong, L.-L.; Liu, B. Inflammatory microenvironment-responsive “double-insurance” nanoreactors for accurate sonodynamic-chemodynamic therapy of rheumatoid arthritis. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 498, 155436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Xie, C.; Ren, X.; Zhang, Q.; Ma, B. CuS nanoenzyme against bacterial infection by in situ hydroxyl radical generation on bacteria surface. Rare Met. 2023, 42, 1899–1911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Y.; Zhang, L.; Chen, J.; Ma, D.; Zhang, Y.; Han, Y. An “all-in-one” therapeutic platform for programmed antibiosis, immunoregulation and neuroangiogenesis to accelerate diabetic wound healing. Biomaterials 2025, 321, 123293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Long, Y.; Yu, G.; Wang, G.; Zhou, Z.; Li, P.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, K.; Wang, S. A Review on Microorganisms in Constructed Wetlands for Typical Pollutant Removal: Species, Function, and Diversity. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 845725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Longhi, C.; Maurizi, L.; Conte, A.L.; Marazzato, M.; Comanducci, A.; Nicoletti, M.; Zagaglia, C. Extraintestinal Pathogenic Escherichia coli: Beta-Lactam Antibiotic and Heavy Metal Resistance. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naik, G.A.R.R.; Roy, A.A.; Mutalik, S.; Dhas, N. Unleashing the power of polymeric nanoparticles—Creative triumph against antibiotic resistance: A review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 278, 134977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.; Wu, Q.; Ni, M.; Chen, C.; Han, C.; Yu, F. Transcriptome Analysis of Endogenous Hormone Response Mechanism in Roots of Styrax tonkinensis Under Waterlogging. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 896850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, T.; Cai, Z.; Chang, X.; Xing, C.; White, S.; Guo, X.; Jin, J. Research Progress of Nanomaterials in Chemotherapy of Osteosarcoma. Orthop. Surg. 2023, 15, 2244–2259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, C.; Miao, Y.; Chai, Y.; Zhang, X.; Dong, X.; Zhao, Y. Highly Water-Stable Zinc Based Metal–Organic Framework: Antibacterial, Photocatalytic Degradation and Photoelectric Responses. Molecules 2023, 28, 6662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miron, A.; Giurcaneanu, C.; Mihai, M.M.; Beiu, C.; Voiculescu, V.M.; Popescu, M.N.; Soare, E.; Popa, L.G. Antimicrobial Biomaterials for Chronic Wound Care. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lelouche, S.N.K.; Albentosa-González, L.; Clemente-Casares, P.; Biglione, C.; Rodríguez-Diéguez, A.; Barrilero, J.T.; García-Martínez, J.C.; Horcajada, P. Antibacterial Cu or Zn-MOFs Based on the 1,3,5-Tris-(styryl)benzene Tricarboxylate. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 2294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Wu, C.; Shen, P.; Zhou, L.; Wang, W.; Lv, K.; Wei, C.; Li, G.; Ma, D.; Xue, W. Tumor microenvironment-responsive multifunctional nanoplatform with selective toxicity for MRI-guided photothermal/photodynamic/nitric oxide combined cancer therapy. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 481, 148618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Wang, C.; Sun, Z.; Lian, Y.; Ji, Q.; Tang, J.; Ma, X. Biocompatible dually reinforced gellan gum hydrogels with selective antibacterial activity. Carbohydr. Polym. 2024, 351, 123071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, N.; Cai, K.; Zhao, J.; Liu, C.; Li, H.; Tan, P.; Li, Y.; Li, D.; Ma, X. Mannosylated MOF Encapsulated in Lactobacillus Biofilm for Dual-Targeting Intervention Against Mammalian Escherichia coli Infections. Adv. Mater. 2025, 37, e2503056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johari, S.A.; Sarkheil, M.; Veisi, S. Cytotoxicity, oxidative stress, and apoptosis in human embryonic kidney (HEK293) and colon cancer (SW480) cell lines exposed to nanoscale zeolitic imidazolate framework 8 (ZIF-8). Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 56772–56781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faustino-Rocha, A.; Silva, A.; Gabriel, J.; Teixeira-Guedes, C.; Lopes, C.; Gil da Costa, R.; Gama, A.; Ferreira, R.; Oliveira, P.; Ginja, M. Ultrasonographic, thermographic and histologic evaluation of MNU-induced mammary tumors in female Sprague-Dawley rats. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2013, 67, 771–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-C.; Lin, K.-Y.A.; Chen, Y.-C.; Hong, Y.-Y.; Hsu, Y.-F.; Lin, C.-H. Impact of photoaging on the chemical and cytotoxic properties of nanoscale zeolitic imidazolate framework-8. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 479, 135536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, H.; Newton, A.A.; Rajib, M.; Zhang, Q.; Gao, W.; Lu, Z.; Zheng, Y.; Dai, Z.; Zhu, J. A ZIF-8-encapsulated interpenetrated hydrogel/nanofiber composite patch for chronic wound treatment. J. Mater. Chem. B 2024, 12, 2042–2053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Yi, Y.; Wang, S.; Dou, H.; Fan, Y.; Tian, L.; Zhao, J.; Ren, L. Bio-Inspired Self-Adaptive Nanocomposite Array: From Non-antibiotic Antibacterial Actions to Cell Proliferation. ACS Nano 2022, 16, 16549–16562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Y.; Weng, J.; Qin, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Ji, S.; Zhang, H. Metal–organic framework- and graphene quantum dot-incorporated nanofibers as dual stimuli-responsive platforms for day/night antibacterial bio-protection. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 473, 145365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Jiang, X.; Wu, Y.; Jiang, J.; Liu, X.; Liu, Y.; Wang, W.; Lai, J.; Wang, X. Zeolitic imidazolate framework-8 encapsulating gold nanoclusters and carbon dots for ratiometric fluorescent detection of adenosine triphosphate and cellular imaging. Talanta 2022, 255, 124226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, H.S.; Tayemeh, M.B.; Abaei, H.; Johari, S.A. On how zeolitic imidazolate framework-8 reduces silver ion release and affects cytotoxicity and antimicrobial properties of AgNPs@ZIF8 nanocomposite. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2023, 668, 131411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, S.; Zhang, J.; Li, X.; Pan, L.; Li, J.; Wu, X.; Yang, S.-T. Low Toxicity of Metal-Organic Framework MOF-74(Co) Nano-Particles In Vitro and In Vivo. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 3398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.; Kalimuthu, P.; Nam, G.; Jung, J. Cyanobacteria control using Cu-based metal organic frameworks derived from waste PET bottles. Environ. Res. 2023, 224, 115532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikzad, M.S.; Qiu, J.; Wang, G.; Wang, X.; Demo, N.S.; Li, A. Safety assessment of copper- and zinc-based metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) for embryonic development and adult fish of Oryzias melastigma. Aquat. Toxicol. 2025, 287, 107529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Xiong, W.; He, S.; Li, F.; Chen, Y.; Li, Z.; Yang, Z.; Zeng, Z.; Song, B. Revealing the synergistic impacts of ZIF-8 and copper co-exposure on zebrafish behavior, tissue damage, and intestine microbial community. Environ. Res. 2025, 269, 120922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, J.; Jia, Y.; Liang, A.; Chen, J.; Zhao, Z.; Huang, Y.; Yu, L.; Yang, J.; Pu, J.; Sun, M.; et al. pH/pectinase dual-responsive metal–organic frameworks enhance the efficacy duration of Isoprothiolane and improve disease resistance in rice. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2025, 716, 164634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Li, D.; Zhang, S.; Wang, S.; Hu, X. Quantum dots bind nanosheet to promote nanomaterial stability and resist endotoxin-induced fibrosis and PM2.5-induced pneumonia. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2022, 234, 113420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, G.; Huang, Y.; Wang, Y.; He, J.; Zhang, R.; Yan, L.; Huang, L.; Zhang, X. Physiological and comprehensive transcriptome analysis reveals distinct regulatory mechanisms for aluminum tolerance of Trifolium repens. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2024, 284, 117001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Miao, X.; Du, S.; Zhang, T.; Chen, L.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, L. Effects of Culinary Procedures on Concentrations and Bioaccessibility of Cu, Zn, and As in Different Food Ingredients. Foods 2023, 12, 1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, A.; He, Y.; Chen, F.-F.; Yu, Y. Antibacterial Activity of M-MOF Nanomaterials (M = Fe, Co, Ni, Cu, and Zn): Impact of Metal Centers. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2024, 7, 24571–24580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Yang, X.; Yuan, T.; Ge, J.; Li, X.; Ma, M.; Ding, S. B, N-codoped carbon confined cobalt nanostructures derived from a single MOF precursor for rapid peroxymonosulfate activation in organic contaminant degradation. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2024, 354, 128842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Z.; Kong, L.; Mei, J.; Li, Q.; Qian, Z.; Ma, Y.; Chen, Y.; Ju, S.; Wang, J.; Jia, W.; et al. Enzymatic bionanocatalysts for combating peri-implant biofilm infections by specific heat-amplified chemodynamic therapy and innate immunomodulation. Drug Resist. Updat. 2023, 67, 100917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Wu, J.; Zhang, B.; Shi, A.; Pei, X.; Zhang, X.; Zhu, Z.; Chen, J.; Wang, J. Optimized fabrication of L-Asp-Cu(II) Bio-MOF for enhanced vascularized bone regeneration. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 505, 159617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, S.; Chen, L.; Liu, C.; Guo, B.; Fan, Y.; Li, Z.; Liu, Y.; Luo, D. Ultrathin ZIF-8 Coating-Reinforced Enzyme Nanoformulation Avoids Lysosomal Degradation for Senile Osteoporosis Therapy. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2410931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Zhang, W.; Wang, J.; Li, W.; Ge, F.; Jin, W.; Tao, Y. Development of the Cu/ZIF-8 MOF Acid-Sensitive Nanocatalytic Platform Capable of Chemo/Chemodynamic Therapy with Improved Anti-Tumor Efficacy. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 19402–19412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saif, M.S.; Waqas, M.; Hussain, R.; Ahmed, M.M.; Tariq, T.; Batool, S.; Liu, Q.; Mustafa, G.; Hasan, M. Potential of CME@ZIF-8 MOF Nanoformulation: Smart Delivery of Silymarin for Enhanced Performance and Mechanism in Albino Rats. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2024, 7, 6919–6931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosohata, K. Role of Oxidative Stress in Drug-Induced Kidney Injury. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 1826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morajkar, R.V.; Kumar, A.S.; Kunkalekar, R.K.; Vernekar, A.A. Advances in nanotechnology application in biosafety materials: A crucial response to COVID-19 pandemic. Biosaf. Heath 2022, 4, 347–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Zhong, R.; Qu, X.; Xiang, Y.; Ji, M. Effect of 8-Hydroxyguanine DNA Glycosylase 1 on the Function of Immune Cells. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sykuła, A.; Nowak, A.; Garribba, E.; Dzeikala, A.; Rowińska-Żyrek, M.; Czerwińska, J.; Maniukiewicz, W.; Łodyga-Chruścińska, E. Spectroscopic Characterization and Biological Activity of Hesperetin Schiff Bases and Their Cu(II) Complexes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Zhong, H.; Huo, J.; Wang, T.; Wu, F.; Du, K.; Feng, T.; Wang, J.-Q. A copper complex with a thiazole-modified tridentate ligand: Synthesis, structural characterization, and anticancer activity in B16-F10 melanoma cells. Dalton Trans. 2025, 54, 14079–14092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, J.; Ma, M.; Shi, S.; Wang, J.; Xiao, P.; Yu, H.-F.; Zhang, C.; Guo, Q.; Yu, Z.; Lou, Z.; et al. Copper enhances genotoxic drug resistance via ATOX1 activated DNA damage repair. Cancer Lett. 2022, 536, 215651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsang, C.Y.; Cheung, M.C.Y.; Beyer, S. Assessing the colloidal stability of copper doped ZIF-8 in water and serum. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2022, 656, 130452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Yu, W.; Zhang, Z.; Deng, F.; Wang, S.; Zou, R.; Wang, Y.; Yuan, B. Rhombic dodecahedral ZIF-8-supported CuFe2O4 triggers sodium percarbonate activation for enhanced sulfonamide antibiotics degradation: Synergistic roles of heterostructure and photocatalytic mechanisms. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 501, 157650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Sun, W.; Li, T.; Zhang, J.; Liu, S.; Liao, Y.; Younas, M.; Qiu, Z. Ultrafast degradation of tetracycline via peroxymonosulfate activation using ZIF-8 modified biochar-supported MgAl/LDH. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 116860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Wang, Z.; Peijnenburg, W.J.G.M.; Vijver, M.G. Review and Prospects on the Ecotoxicity of Mixtures of Nanoparticles and Hybrid Nanomaterials. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56, 15238–15250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bose, S.; Kumar, M. Nickel-decorated ZIF-67 (Co) MOF derived bi-metallic catalyst for efficient degradation of tetracycline under microwave irradiation through persulfate activation route: Performance assessment and predictive intermediate toxicity profile. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 364, 132371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Nie, X.; Liu, X. Preparation of Fe/Co bimetallic MOF photofenton catalysts and their performance in degrading tetracycline hydrochloride pollutants efficiently under visible light. J. Alloys Compd. 2024, 1010, 176967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rastin, H.; Dell’aNgelo, D.; Sayede, A.; Badawi, M.; Habibzadeh, S. Green and sustainable metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) in wastewater treatment: A review. Environ. Res. 2025, 282, 122087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, N.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, Q.; Zhang, X.; Duan, J.; Hou, B. Novel MOF-Based Photocatalyst AgBr/AgCl@ZIF-8 with Enhanced Photocatalytic Degradation and Antibacterial Properties. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Chen, T.; Lu, J.; Hu, H.; Zheng, H.; Zhu, P.; Pan, X. Metal–organic frameworks doped with metal ions for efficient sterilization: Enhanced photocatalytic activity and photothermal effect. Water Res. 2022, 229, 119366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, J.; Li, Y.; Xia, X.; Yang, H.; Kim, J.H.; Zhang, W. Silver single atoms and nanoparticles on floatable monolithic photocatalysts for synergistic solar water disinfection. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Xue, B.; Ruan, S.; Guo, J.; Huang, Y.; Geng, X.; Wang, D.; Zhou, C.; Zheng, J.; Yuan, Z. Supercharged precision killers: Genetically engineered biomimetic drugs of screened metalloantibiotics against Acinetobacter baumanni. Sci. Adv. 2024, 10, eadk6331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pahlevani, M.; Beig, M.; Barzi, S.M.; Sadeghzadeh, M.; Shafiei, M.; Chiani, M.; Sohrabi, A.; Sholeh, M.; Nasr, S. Antibacterial and wound healing effects of PEG-coated ciprofloxacin-loaded ZIF-8 nanozymes against ciprofloxacin-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa taken from burn wounds. Front. Pharmacol. 2025, 16, 1556335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, S.; Pan, Y.; Wang, J.; Jiang, Z.; Ma, T.; Chen, S.; Chen, M.; Wu, Y.; Leng, Y.; Hu, Y.; et al. Bone-targeting ZIF-8 based nanoparticles loaded with vancomycin for the treatment of MRSA-induced periprosthetic joint infection. J. Control. Release 2025, 385, 113965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, H.-V.T.; Pham, S.N.; Mirzaei, A.; Mai, N.X.D.; Nguyen, C.C.; Nguyen, H.T.; Vong, L.B.; Nguyen, P.T.; Doan, T.L.H. Surface modification of ZIF-8 nanoparticles by hyaluronic acid for enhanced targeted delivery of quercetin. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2024, 696, 134288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasiri, K.; Masoumi, S.M.; Amini, S.; Goudarzi, M.; Tafreshi, S.M.; Bagheri, A.; Yasamineh, S.; Alwan, M.; Arellano, M.T.C.; Gholizadeh, O. Recent advances in metal nanoparticles to treat periodontitis. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2023, 21, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Liang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Deng, Y.; Fu, H.; Yuan, X.; Wang, Z.; Lu, X.; Lin, B. Active cellulose-based film with synergistic enhanced photothermal antibacterial effects by Fe-doped ZIF-8 and EGCG for efficient litchi preservation. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 521, 166462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Lei, T.; Zhu, F.; Wang, M.; Yu, Z.; Liu, Y.; Deng, C.; Liu, C.; Xiao, H. Lignosulfonate-Decorated Boron Nitride/Cellulose Nanofibril Porous Foam: Multifunctional Phase Change Composites for Leakage-Free Thermal Energy Storage and Photothermal Conversion. Biomacromolecules 2025, 26, 5873–5887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Y.; Shi, J.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Han, Y. One-step engineered multifunctional gauze: On-demand antibiosis, accelerated hemostasis and angiogenesis for tissue regeneration. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 322, 146866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Zhu, Y.; Li, X.; Li, D.; Jia, K.; Liu, Y. Photo-Activated Cu-ZIF-8 Integrated Sprayable Hydrogels for Accelerated Wound Healing. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2025, 8, 8197–8217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, A.; Qiao, Q.; Pei, Z.; Wang, Z.; Guo, J.; Li, Y.; Zhai, G.; Fei, P.; Lu, J.; Jia, H. Polyurethane-based T-ZIF-8 nanofibers as photocatalytic antibacterial materials. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2023, 6, 22173–22184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, J.; Zhang, J.; Yuan, M.; Lv, Y.; Chen, Z.; Wang, M. Visible-light-driven Au/PCN-224/Cu(II) modified fabric with enhanced photocatalytic antibacterial and degradation activity and mechanism insight. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2023, 333, 125863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Mehalmey, W.A.; Latif, N.; Ibrahim, A.H.; Haikal, R.R.; Mierzejewska, P.; Smolenski, R.T.; Yacoub, M.H.; Alkordi, M.H. Nine days extended release of adenosine from biocompatible MOFs under biologically relevant conditions. Biomater. Sci. 2022, 10, 1342–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viana, R.S.; de Araújo, P.M.; da Silva, J.P.; de Santana, J.R.; Ferreira, E.G.A.; Barros, A.B.B.; Barbosa, C.D.A.D.E.S.; Puma, C.A.L.; Jesus, L.T.; Freire, R.O.; et al. Luminescent Nanocomposite SiO2/EuTTA/ZIF-8 Loaded with Uvaol: Synthesis, Characterization, Anti-Inflammatory Effects, and Molecular Docking Analysis. ACS Omega 2025, 10, 32391–32403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruan, F.; Liu, C.; Zeng, J.; Zhang, F.; Jiang, Y.; Zuo, Z.; He, C. Multi-omics integration identifies ferroptosis involved in black phosphorus quantum dots-induced renal injury. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 947, 174532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, K.; Li, Y.; Zhou, Q.; Hu, X.; Ouyang, S. Integrating FTIR 2D correlation analyses, regular and omics analyses studies on the interaction and algal toxicity mechanisms between graphene oxide and cadmium. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 443, 130298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Guan, J.; Lai, S.; Fang, L.; Su, J. pH-responsive curcumin-based nanoscale ZIF-8 combining chemophotodynamic therapy for excellent antibacterial activity. RSC Adv. 2022, 12, 10005–10013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Xu, J.; Chen, X.; Yao, M.; Pei, M.; Yang, Y.; Gao, P.; Zhang, C.; Wang, Z. Co-exposure of butyl benzyl phthalate and TiO2 nanomaterials (anatase) in Metaphire guillelmi: Gut health implications by transcriptomics. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 354, 120429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Liang, K.; Zhong, H.; Liu, S.; He, R.; Sun, P. A cold-water polysaccharide-protein complex from Grifola frondosa exhibited antiproliferative activity via mitochondrial apoptotic and Fas/FasL pathways in HepG2 cells. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 218, 1021–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Subhadarshini, A.; Subudhi, E.; Achary, P.G.R.; Behera, S.A.; Parwin, N.; Nanda, B. ZIF-8 supported Ag3PO4/g-C3N4 a Double Z-scheme heterojunction: An efficient photocatalytic, antibacterial and hemolytic nanomaterial. J. Water Process. Eng. 2024, 65, 105901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Wu, H.; Sathishkumar, G.; He, X.; Ran, R.; Zhang, K.; Rao, X.; Kang, E.T.; Xu, L. Chemo-photothermal therapy of bacterial infections using metal–organic framework-integrated polymeric network coatings. J. Mater. Chem. B 2024, 12, 9238–9248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Material Type | Test Cell Line | Key Toxicity Manifestations/Mechanisms | Biocompatibility Results | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| nZIF-8 | BEAS-2B (lung epithelial) | At high concentrations, ROS, mitochondrial damage, apoptosis | Concentration-dependent toxicity | [47] |

| ZIF-8 Composite Fiber Membrane | L929 (fibrogenesis) | - | Low toxicity, survival rate > 80–90% | [48,50] |

| CDs/AuNCs@ZIF-8 | HepG2 (Liver cancer) | - | Low toxicity | [51] |

| AgNPs@ZIF-8 | HSF (Skin fibroblast) | Ag+ release resulted in an IC50 of 31.4–39 μg/mL. | Ion release dominates toxicity | [52] |

| Cu-BTC (MOF-199) | MCF7 | High toxicity, IC50 = 3.49 mg/L | Cu2+ is more toxic than Zn2+ | [53] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ren, H.; Gao, C.; Huang, S.; Du, L.; Liu, S.; Cao, X.; Lv, Y. Photocatalytic Antibacterial Mechanism and Biotoxicity Trade-Off of Metal-Doped M-ZIF-8 (M=Co, Cu): Progress and Challenges. Inorganics 2026, 14, 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/inorganics14020043

Ren H, Gao C, Huang S, Du L, Liu S, Cao X, Lv Y. Photocatalytic Antibacterial Mechanism and Biotoxicity Trade-Off of Metal-Doped M-ZIF-8 (M=Co, Cu): Progress and Challenges. Inorganics. 2026; 14(2):43. https://doi.org/10.3390/inorganics14020043

Chicago/Turabian StyleRen, Huili, Chenxia Gao, Siqi Huang, Libo Du, Shuang Liu, Xi Cao, and Yuguang Lv. 2026. "Photocatalytic Antibacterial Mechanism and Biotoxicity Trade-Off of Metal-Doped M-ZIF-8 (M=Co, Cu): Progress and Challenges" Inorganics 14, no. 2: 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/inorganics14020043

APA StyleRen, H., Gao, C., Huang, S., Du, L., Liu, S., Cao, X., & Lv, Y. (2026). Photocatalytic Antibacterial Mechanism and Biotoxicity Trade-Off of Metal-Doped M-ZIF-8 (M=Co, Cu): Progress and Challenges. Inorganics, 14(2), 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/inorganics14020043