1. Introduction

Infectious diseases instigated by pathogenic bacteria continue to pose a pervasive threat to global public health, exacerbated by the emergence and proliferation of multidrug-resistant (MDR) strains that undermine the effectiveness of conventional antimicrobial therapies. Infectious diseases driven by pathogenic bacteria remain a critical global health challenge, exacerbated by their pervasive presence in both clinical settings and the environment. Among these challenges, the microbial contamination of water sources resulting from anthropogenic activities, such as agricultural runoff, sewage discharge, and industrial effluents, poses a critical barrier to ensuring safe drinking water. Pathogenic bacteria, such as

Escherichia coli,

Salmonella spp., and

Vibrio cholerae, are frequently implicated in waterborne disease outbreaks, contaminating both surface and groundwater systems on an alarming scale [

1]. Conventional disinfection strategies, notably chlorination and ozonation, remain cornerstones of municipal water treatment infrastructure. However, their efficacy is increasingly constrained by several physicochemical and microbiological factors, particularly in the inactivation of chlorine- and ozone-resistant strains. Chlorination, albeit effective against a broad spectrum of pathogens, is associated with the generation of disinfection byproducts (DBPs) such as trihalomethanes (THMs) and haloacetic acids (HAAs), which are persistent and linked to carcinogenic outcomes in humans [

2]. Ozonation, though a potent oxidizing method, suffers from inherent limitations, including ozone’s rapid decomposition, necessitating on-site generation and continuous replenishment to sustain disinfection potency [

3]. Moreover, both chlorine-based agents and ozone can produce secondary pollutants or residual toxicity, raising ecological and toxicological concerns. Notably, failures in disinfection protocols, such as suboptimal chlorine dosing, have contributed to significant public health incidents. This includes multistate outbreaks of Salmonella, underscoring the urgent necessity for next-generation antimicrobial technologies that are both broad-spectrum and environmentally benign.

Therefore, the development of high-efficiency photocatalytic antibacterial materials is of paramount importance for advancing global health and environmental resilience, directly contributing to the realization of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly SDG 3 (Good Health and Well-being) and SDG 6 (Clean Water and Sanitation). Over recent decades, photocatalytic antimicrobial technologies have experienced significant growth, with demonstrated applicability across a broad range of sectors including healthcare disinfection [

4], water purification [

5], and environmental remediation [

6]. These materials harness solar irradiation to generate reactive species that effectively inactivate pathogenic microorganisms, thereby offering a sustainable, non-toxic, and energy-efficient route to mitigating microbial contamination [

7]. As such, the rational design and advancement of visible-light-responsive photocatalysts represent a critical frontier in safeguarding public and environmental health. Therefore, advancing visible-light-responsive photocatalysts represents a critical strategy for mitigating bacterial threats and safeguarding environmental and human health. Traditionally, research in this domain has been predominantly centered on titanium dioxide (TiO

2), a benchmark photocatalyst known for its chemical stability and photocatalytic efficacy under ultraviolet (UV) light. However, TiO

2 is limited by its wide band gap (~3.2 eV), rendering it only photoactive under UV irradiation, which comprises merely ~4% of the solar spectrum [

8]. This limitation has prompted a strategic shift toward the exploration of alternative photocatalysts that can efficiently harvest visible light, which accounts for approximately 45% of solar energy. Among these, bismuth vanadate (BiVO

4) has emerged as a particularly attractive candidate due to its narrow band gap (~2.4 eV), high chemical stability, non-toxicity, and resistance to photocorrosion [

8].

BiVO

4 exists in three principal crystalline polymorphs: tetragonal zircon, tetragonal scheelite, and monoclinic scheelite [

9]. The tetragonal zircon phase features valence and conduction bands primarily derived from O 2p and V 3d orbitals, whereas the scheelite-type structures incorporate Bi 6s and O 2p orbital contributions into the valence band, leading to a reduction in band gap energy [

10]. Specifically, the monoclinic scheelite phase demonstrates superior photocatalytic performance, attributed to its enhanced charge separation and broader visible-light absorption [

11]. The intrinsic band gap of BiVO

4 (∼2.42 eV) enables efficient harvesting of the visible spectrum, while its crystal structure and optical properties further support its candidacy as a solar-driven photocatalyst [

9].

Despite these advantages, BiVO

4 suffers from diminished photocatalytic efficacy relative to isostructural semiconductor materials, attributed to suboptimal charge carrier mobility, elevated recombination kinetics, and inefficient interfacial charge transfer mechanisms [

12]. Additionally, BiVO

4 suffers from a low conduction band potential and fast recombination of photoinduced electron–hole pairs. In aqueous environments, BiVO

4 often forms microcrystalline aggregates with low surface area and smooth facets, leading to suboptimal dispersion and reduced photocatalytic contact with target contaminants [

13]. These drawbacks necessitate innovative material design strategies, such as heterojunction formation, surface modification, or internal field engineering, to overcome the kinetic barriers of BiVO

4.

One of the principal limitations governing the suboptimal photocatalytic performance of BiVO

4 is its inherently low electronic conductivity, which significantly impedes efficient charge carrier transport. This poor conductivity restricts the migration of photogenerated electrons and holes to active surface sites, thereby increasing the likelihood of bulk recombination events and reducing the quantum efficiency of photocatalytic processes. The electronic structure of BiVO

4 plays a pivotal role in mediating this recombination behavior. For instance, doping studies involving molybdenum (Mo) and tungsten (W) have demonstrated that strategic elemental substitution not only enhances electrical conductivity but also suppresses recombination rates by over an order of magnitude. This is primarily attributed to the modulation of the conduction band edge, which remains energetically lower than the reduction potential required for superoxide radical anion (·O

2−) formation, a critical reactive species in oxidative photocatalysis. Consequently, photogenerated electrons often lack the thermodynamic driving force to initiate redox reactions before undergoing recombination, thereby diminishing photocatalytic efficacy. The conduction band’s relatively low energy level plays a role in reducing the stability of photogenerated electrons. Moreover, the band structure of BiVO

4 across both its monoclinic scheelite and tetragonal zircon polymorphs governs the charge separation and recombination processes. The relatively low conduction band minimum (CBM) compromises the stability and reactivity of photoexcited electrons, further exacerbating recombination kinetics [

14].

In this context, the integration of piezoelectric materials offers a compelling strategy for facilitating spatially resolved charge separation. The piezoelectric effect, activated under mechanical stimuli such as compressive strain, ultrasonic vibration, or external mechanical deformation, generates an internal electric field via ferroelectric polarization. This strain-induced piezoelectric potential induces directional migration of photogenerated charge carriers, establishing a built-in electric field that serves to spatially separate electrons and holes. The resultant band bending at the interface generates a favorable thermodynamic gradient, promoting carrier diffusion, effectively elongating their diffusion lengths and enhancing carrier lifetimes. This field induces directional migration of photogenerated electrons and holes via strain-induced piezoelectric potential, thereby minimizing recombination kinetics [

15]. This piezoelectric modulation has been widely leveraged in functional optoelectronic systems, including photocatalytic water splitting, CO

2 photoreduction, and environmental pollutant degradation, where efficient charge utilization is critical [

16].

Since tourmaline is a naturally abundant mineral and can be utilized with minimal post-processing, its implementation as a functional material aligns with principles of environmental sustainability. Functionally analogous to magnetic dipoles, tourmaline crystals exhibit spontaneous polarization, enabling their use as naturally occurring electrodes in energy conversion systems. Among piezoelectric minerals, tourmaline demonstrates one of the highest piezoelectric coefficients, with a reported value of 4.1 pC/N, resulting in a substantial charge output of 4.1 × 10

−9 C and a voltage of 0.41 V under an applied force of 1000 N. This performance surpasses that of other naturally piezoelectric materials such as quartz, topaz, and zinc-based compounds, which are limited either by lower conversion efficiency or by material instability under operating conditions. Under external mechanical stimuli, such as vibration, seismic motion, or compressive force, tourmaline undergoes polarization-induced potential generation. This charge separation can be harnessed via electrodes to produce usable electrical energy, rendering it a promising eco-compatible component for hybrid piezo-photocatalytic system [

17,

18,

19].

2. Results

2.1. Structural and Morphological Analysis

Figure 1 presents the X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns of pristine BiVO

4 (BVO) and the tourmaline/BiVO

4 composites. All samples exhibit well-defined and sharp diffraction peaks, demonstrating good crystallinity. The diffraction pattern of pure BiVO

4 matches well with the monoclinic scheelite structure (JCPDS card No. 83-1699), with characteristic reflections appearing at 2θ ≈ 18.9°, 28.9°, 30.5°, 34.5°, and 35.2°, corresponding to the (011), (112), (004), (200), and (020) planes, respectively [

20]. This confirms that the BiVO

4 phase is successfully formed.

After the incorporation of tourmaline, no new diffraction peaks corresponding to crystalline tourmaline are observed in the composite patterns. Tourmaline itself is a complex borosilicate mineral with a multi-component trigonal crystal structure. In XRD, its strongest diffraction peaks typically appear near 2θ ≈ 21°, 26°, and 30°, but these peaks are weak due to its low scattering factor and may overlap with the more intense BiVO4 peaks. In the present composites, the absence of distinct tourmaline reflections can therefore be attributed to (i) the low tourmaline loading, (ii) partial amorphousness of the tourmaline phase, and (iii) peak overlap with the BiVO4 lattice. This behavior has also been reported in previous tourmaline-based composite photocatalysts.

Although new tourmaline peaks were not observed, a subtle but systematic rightward shift of (112) diffraction peak of BiVO

4 is observed for all tourmaline-containing samples. This shift toward higher 2θ values indicates a reduction in interplanar spacing (d-spacing) according to Bragg’s Law [

21]:

where

d is the interplanar spacing,

λ is the wavelength, and

n is the number of reflection stages.

The calculated d-spacing values for the key diffraction planes of each sample are summarized in

Table 1. The slight decrease in d-spacing suggests the presence of lattice compression or interfacial strain in BiVO

4 introduced by the composition of tourmaline. Such strain effects typically arise from interfacial interactions between phases with mismatched lattice parameters or from surface polarization effects associated with piezoelectric minerals.

To further quantify the influence of tourmaline on the BiVO

4 crystal lattice, the microstrain (ε) was estimated using the standard relation:

where

d0 represents the d-spacing of pristine BiVO

4 and Δ

d is the difference between the pristine and composite samples.

The data in

Table 1 demonstrate that the lattice strain increases progressively with higher tourmaline content, confirming that tourmaline induces compressive effects on the BiVO

4 lattice. This strain is likely caused by interfacial interactions, including electrostatic forces generated by tourmaline’s spontaneous polarization and short-range chemical bonding between tourmaline surface groups and BiVO

4. The spontaneous polarization of tourmaline induces local electric fields at the heterointerface, creating an electrostatic force that perturbs the BiVO

4 lattice. Additionally, chemical bonding or short-range interactions between surface functional groups (e.g., BO

3/SiO

4 groups of tourmaline and VO

4/Bi–O networks) may contribute to local lattice distortion. These interfacial effects lead to slight adjustments in the BiVO

4 crystal spacing, manifested as the rightward peak shift in XRD. The lattice compression and interfacial polarization have important implications for photocatalytic performance. The induced strain can modulate the local electronic environment, promoting enhanced charge separation and carrier mobility at the heterointerface. This, in combination with the intrinsic polar field of tourmaline, contributes to the observed improvement in photocatalytic antibacterial activity, as discussed in subsequent sections.

Overall, the XRD results confirm that tourmaline does not alter the crystal phase of BiVO4 but induces subtle lattice compression due to interfacial polarization and strain. This structural modification is consistent with the enhanced charge separation behavior discussed later, as lattice perturbation can modify band structure and influence carrier transport within semiconductor composites.

Furthermore, scanning electron microscopy (SEM) was employed to investigate the morphology and microstructure of the as-prepared materials.

Figure 2 displays representative SEM images of pristine tourmaline powder, pure BiVO

4, and BiVO

4 composites containing 6 wt.% and 10 wt.% tourmaline. The untreated tourmaline powder exhibits an irregular, bulk-like morphology with no defined particle shape. In contrast, BiVO

4 synthesized via the sol–gel method forms relatively uniform spherical particles with an average size of ~800 nm. For the 6 wt.% and 10 wt.% Tourmaline/BiVO

4 composites, BiVO

4 nanoparticles are observed to be uniformly anchored on the tourmaline surface, suggesting effective dispersion and strong interfacial contact. This well-distributed structure likely facilitates the enhanced charge separation and interfacial transport critical for improved photocatalytic activity.

2.2. The Local Structure of the Composite Photocatalysts

Raman spectroscopy and infrared (IR) reflectance spectroscopy were employed to investigate the local structural and vibrational properties of the synthesized samples. Raman spectroscopy is based on the inelastic scattering of monochromatic light, where energy exchange between incident photons and vibrational or phonon modes results in a wavelength shift. Raman-active modes correspond to vibrations that induce a change in the polarizability tensor of the molecule or lattice [

18]. Infrared Reflectance Spectroscopy (often meaning mid-IR reflectance or FTIR in reflectance mode) probes vibrational transitions via absorption (and consequent changes in reflectance) of IR radiation; IR-active modes are those that involve a change in the dipole moment during vibration. Together, these techniques offer complementary insights into lattice dynamics, crystallographic orientation, and local symmetry [

22].

Figure 3 displays the Raman spectra of BiVO

4 powders with various tourmaline mass ratios, measured in the spectral range of 100–1100 cm

−1. Several characteristic vibrational modes associated with the VO

43− tetrahedron are evident. The bands near 324 and 366 cm

−1 are attributed to symmetric and asymmetric bending vibrations, respectively [

23], while the prominent peak at 640 cm

−1 corresponds to the asymmetric stretching of the shorter V–O bonds. Peaks around 710 and 811 cm

−1 are assigned to symmetric stretching modes, which provide further insight into V–O bond lengths [

24]. Moreover, external lattice modes such as translational and rotational motions are observed near 213 cm

−1. Pure tourmaline exhibited no detectable Raman activity within this spectral window, consistent with its complex silicate structure and low Raman cross-section. However, with increasing tourmaline content in the BiVO

4 matrix, notable shifts in Raman band positions and intensities were observed. Specifically, the asymmetric deformation mode (~366 cm

−1) shifted toward higher wavenumbers, while the symmetric deformation mode (~324 cm

−1) shifted to lower wavenumbers as the mass ratio of tourmaline increased. These spectral shifts suggest structural distortion and symmetry breaking in the VO

43− tetrahedral units, likely induced by internal electric fields generated by the spontaneously polarized tourmaline. Such distortions indicate lattice strain and modified local symmetry environments, which can significantly influence the electronic structure and carrier dynamics of the material. The observed changes are consistent with enhanced electron–hole separation and improved photocatalytic performance discussed in subsequent sections. Overall, the Raman analysis reveals that tourmaline integration alters the vibrational characteristics of BiVO

4, confirming strong interfacial interaction and lattice modulation within the composite.

To further elucidate the molecular vibrations and bonding environment within the tourmaline/BiVO

4 composite, Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy in attenuated total reflectance mode (FT-ATR-IR) was employed (FT-ATR-IR) [

25]. As shown in

Figure 4, the characteristic vibrational bands of BiVO

4 were observed, including the V–O stretching vibration at 610 cm

−1 and the Bi–O bending mode at 471 cm

−1 [

26]. These results confirm the retention of the BiVO

4 crystal structure, particularly its photocatalytically favorable monoclinic phase.

A prominent peak at ~1050 cm

−1, corresponding to the Si–O stretching vibration, was also detected [

27], indicating the presence of tourmaline, whose silicate framework includes Si–O bonds as a structural motif. As observed, the intensity and sharpness of this peak increased with the tourmaline mass ratio, suggesting enhanced structural integration and higher degrees of crystallinity within the composite. Ultimately, these observations imply that the incorporation of tourmaline contributes to a more ordered and uniform bonding environment, possibly enhancing charge separation and stability. Collectively, the FT-IR results confirm successful compounding of tourmaline into the BiVO

4 matrix and suggest that increasing tourmaline content induces improved structural organization, which could positively influence the photocatalytic behavior of the material.

2.3. The Photophysical Property of the Photocatalysts

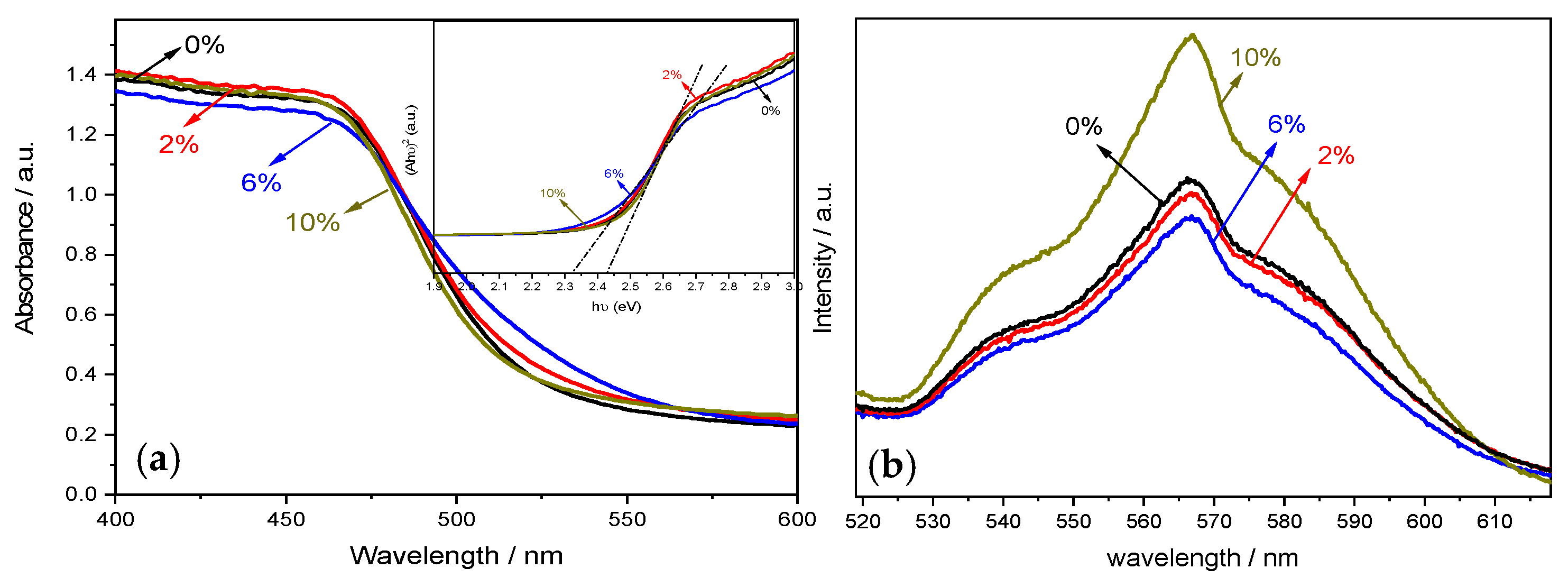

UV–Visible diffuse reflectance spectroscopy (UV–Vis DRS) was conducted to evaluate the optical absorption behavior of the composite materials. This technique is particularly suited for assessing the band structure and light-harvesting capability of semiconductor photocatalysts. As shown in

Figure 5, all samples exhibited strong absorption in the visible light region (400–700 nm). Pristine BiVO

4, known as a visible-light-responsive semiconductor, exhibits a narrow band gap (~2.4–2.5 eV), enabling absorption up to approximately 520 nm. This visible-light activity arises from electronic transitions from the valence band (dominated by O 2p orbitals) to the conduction band (primarily V 3d orbitals). The composite samples maintained a steep absorption edge, indicating that the visible-light absorption is primarily due to intrinsic band-to-band transitions, rather than sub-bandgap transitions via defect states or impurity levels. This behavior is characteristic of a well-crystallized semiconductor with either a direct or indirect allowed transition, depending on the phase (e.g., monoclinic or tetragonal) of BiVO

4.

To further investigate the band structure, the band gap energy (E

9) can be estimated using the Tauc formula [

28]:

where

hν is the photon energy (in eV),

Eg is the optical band gap (eV), α is the absorption coefficient derived from the UV–Vis DRS data, A is a proportionality constant, and

n is the transition type exponent. For BiVO

4, which undergoes a direct allowed transition,

n = 2 [

29].

The curve derived from this formula, the “Tauc plot”, can be utilized to accurately estimate the optical band gaps. From this plot, the estimated band gap energies for pure BiVO4 and the tourmaline/BiVO4 composites were approximately 2.46, 2.45, 2.38, and 2.40 eV, respectively. These results reveal a slight red shift in the absorption edge with increasing tourmaline content, indicating a narrowing of the band gap. This red shift reflects improved light-harvesting in the visible region, likely due to electronic interactions at the tourmaline/BiVO4 interface and an enhanced charge transfer environment. The reduction in band gap implies better utilization of solar photons, which is advantageous for enhancing photocatalytic activity under natural sunlight.

Simultaneously, the corresponding photoluminescence (PL) spectra were employed to investigate the recombination behavior of photogenerated charge carriers, offering insights into the separation efficiency and dynamics of electron–hole pairs [

30]. The PL spectra of all prepared photocatalysts were measured at room temperature using an excitation wavelength of 325 nm, as shown in

Figure 6. All samples exhibited a prominent emission peak centered around 570 nm, corresponding to band-edge recombination in BiVO

4. Generally, high PL intensity indicates rapid recombination of photogenerated electron–hole pairs, while lower intensity suggests enhanced separation efficiency. Among the tested samples, the 6 wt.% tourmaline/BiVO

4 composite exhibited the weakest PL intensity, implying significantly reduced recombination and more efficient charge carrier separation. In contrast, the 10 wt.% tourmaline/BiVO

4 sample displayed the highest PL intensity, likely due to excessive tourmaline content acting as recombination centers or impeding effective charge transfer pathways. These findings suggest that moderate incorporation of tourmaline, specifically at 6 wt.%, optimally facilitates interfacial charge separation, thus contributing to improved photocatalytic performance.

2.4. Photocatalytic Antibacterial Efficiency

The photocatalytic properties of tourmaline/BVO compositions were evaluated by comparing their respective antibacterial abilities. The anti-microbial properties of the prepared samples were evaluated under visible light irradiation utilizing bacterial cultures of

Escherichia coli (Gram-negative) and

Staphylococcus aureus (Gram-positive). Both cultures were prepared at an initial concentration of 2 × 10

6 CFU/mL. Based on prior studies conducted within our group, negligible changes in bacterial count were observed in both dark and blank control conditions, confirming that visible light alone has no significant bactericidal effect in this system [

31,

32]. Therefore, the observed antibacterial activity can be attributed solely to the photocatalytic action of the synthesized materials.

Figure 6 presents the bacterial survival curves under visible light exposure. Notably, the 6 wt.% T/BVO composite exhibited superior antibacterial activity compared to pure BiVO

4, achieving nearly complete inactivation of both

E. coli and

S. aureus within 120 min. Among the two, S. aureus was more susceptible to photocatalytic inactivation, suggesting a differential response likely rooted in structural differences between Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacterial cell walls. Individually, both tourmaline and BiVO

4 demonstrated limited antibacterial activity, with tourmaline showing a slightly higher effect, consistent with previous reports. However, the significantly enhanced performance of the T/BVO composites indicates a synergistic interaction between tourmaline and BiVO

4, particularly at the optimized 6 wt.% loading. Photographs of the bacterial colonies post-treatment, shown in

Figure S1, visually corroborate the quantitative results. The heightened antibacterial efficacy against S. aureus may be attributed to the increased interaction between the photocatalyst surface and the thick peptidoglycan layer characteristic of Gram-positive bacteria. The negatively charged surface of the polarized T/BVO composite likely promotes stronger electrostatic interactions with the bacterial cell walls, facilitating reactive oxygen species (ROS)-mediated damage.

The enhanced photocatalytic disinfection efficiency is thus proposed to arise from two main mechanisms: the electrostatic attraction between bacterial cells and the surface-polarized T/BVO composite, and the generation of reactive oxygen species, such as superoxide radicals (·O2−), via surface redox reactions under visible light, leading to oxidative damage of bacterial membranes. Overall, the 6 wt.% tourmaline/BiVO4 composite exhibited the most favorable photocatalytic antibacterial performance, exemplifying its potential for application in light-driven disinfection technologies and antifouling strategies in biomedical and environmental settings.

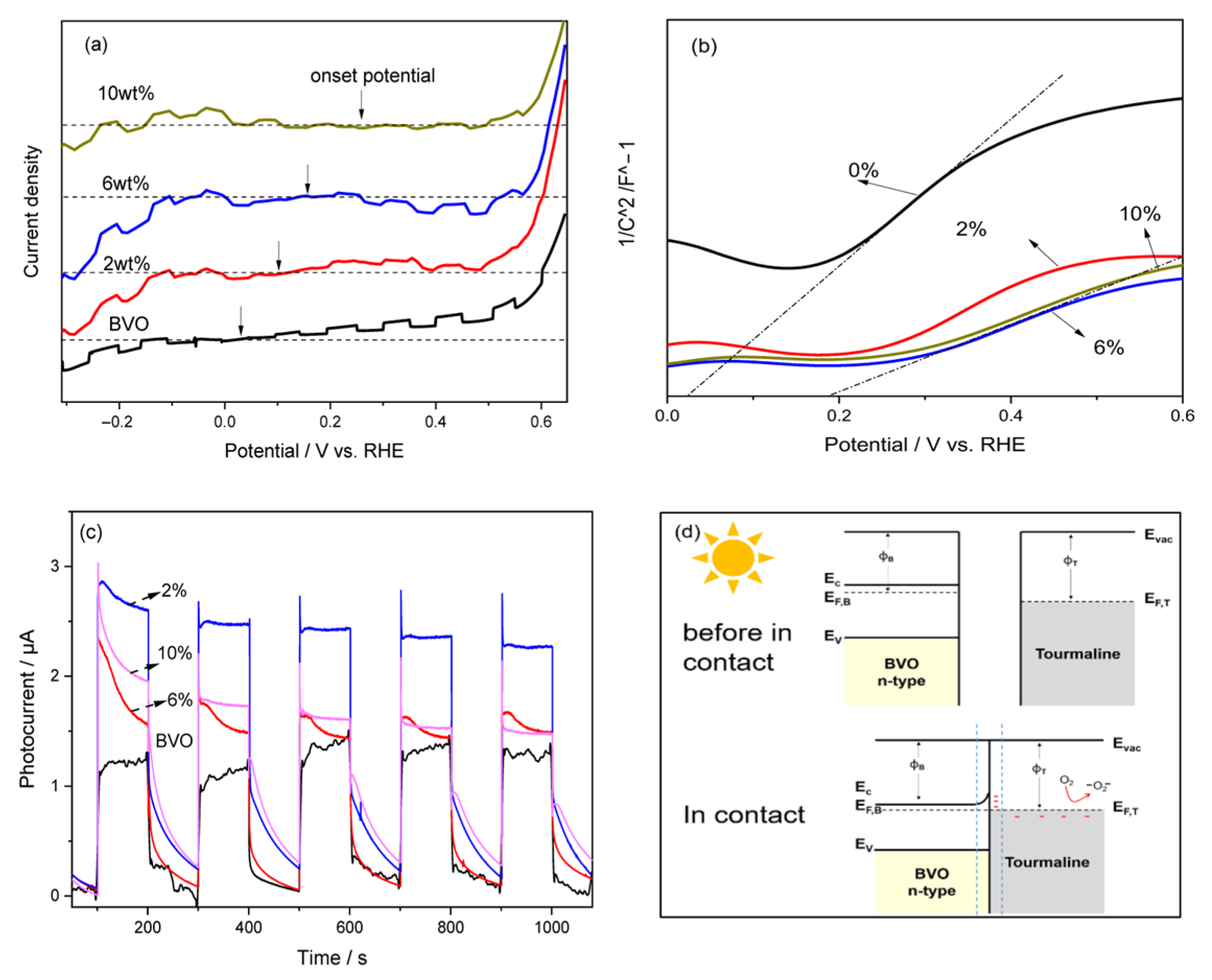

2.5. Photoelectrochemical Measurement

Photocatalytic reactions on semiconductor surfaces typically proceed through three sequential steps: (1) absorption of photons with energy equal to or greater than the semiconductor’s band gap, leading to the generation of electron–hole pairs; (2) separation and migration of these photoexcited charge carriers to the surface without undergoing recombination; and (3) surface redox reactions where photogenerated electrons and holes reduce or oxidize adsorbed species, respectively. Among these, the second step (carrier separation and transport) is crucial, as it directly governs the overall photocatalytic efficiency.

To evaluate the separation and surface transfer dynamics of photogenerated carriers, photoelectrochemical (PEC) measurements were conducted. This method offers direct insight into charge transport behavior and surface reaction potential under light excitation. The photocurrent responses of the prepared thin films were measured in a 1 M Na

2SO

4 and Na

2SO

3 electrolyte under visible light illumination (390–780 nm, 100 mW·cm

−2), with the films irradiated from the back side through the FTO substrate. The measured potential (vs. Ag/AgCl) was converted to the reversible hydrogen electrode (RHE) scale using the following equation:

Figure 5a displays the photocurrent–potential (I–V) curves for the different samples under chopped light illumination. All samples exhibited increasing photocurrent densities with increasing anodic bias, a characteristic behavior of n-type semiconductors. The point at which the photocurrent switches direction, known as the onset potential, provides key information regarding the material’s Fermi level (E

f) and band bending [

33]. Notably, upon incorporating tourmaline, the onset potential of pristine BiVO

4 (0.045 V) shifted positively to 0.245 V in the composite, indicating a shift in the Fermi level and enhanced band bending, which facilitates more efficient charge separation. Furthermore, both the 2 wt.% and 6 wt.% tourmaline/BiVO

4 composites exhibited significantly higher photocurrent densities compared to pure BiVO

4, especially at higher applied potentials. This enhancement suggests improved separation and migration of photogenerated charge carriers, likely due to internal electric fields generated by the tourmaline component.

To further elucidate this behavior, Mott–Schottky (MS) plots were obtained and are shown in

Figure 5b. These plots provide information about the flat-band potential and donor density, enabling a deeper understanding of the electrochemical properties of the materials. The corresponding equation used to interpret MS plots is as follows:

where C is the capacitance of the space charge region, e is the electron charge, ε is the dielectric constant of the semiconductor, ε

0 is the vacuum permittivity, N

D is the donor density, V is the applied potential, and V

fb is the flat band potential. κ is the Boltzmann constant. T The MS analysis confirms that the inclusion of tourmaline not only shifts the flat-band potential positively but also increases the carrier density, facilitating more efficient photoinduced charge transfer. These findings support the conclusion that moderate tourmaline incorporation, particularly at 6 wt.%, significantly improves the PEC performance of BiVO

4-based photocatalysts, offering a promising strategy for enhanced solar-driven applications. T is the thermodynamic temperature.

By combining insights from the photocurrent–potential curves and Mott–Schottky (MS) plots, the direction of charge carrier movement and the underlying separation mechanism can be deduced. In pure BiVO

4 (BVO), upon visible light irradiation, electrons in the valence band absorb photon energy and are excited to the conduction band, generating electron–hole pairs. The resulting photovoltage (V

photo) facilitates the migration of these carriers toward the surface. Due to the internal electric field in the space charge region, electrons and holes are separated and migrate to different crystal facets: electrons predominantly move toward the {010} facets, while holes migrate toward the {110} facets [

34]. As BVO is an n-type semiconductor, electrons are the majority carriers, and the Fermi level (E

f) tends to shift closer to the flat-band potential. However, defects within the material act as recombination centers, limiting the number of electrons that can participate in surface redox reactions. The band bending gradually decreases until the generation rate of charge carriers is balanced by the recombination rate [

10].

3. Discussion

The incorporation of tourmaline into the BiVO4 matrix markedly enhances the charge-separation efficiency, thereby improving the photocatalytic and antibacterial performance of the composite. Tourmaline is a naturally polar mineral that exhibits spontaneous surface polarization, even at room temperature. Under illumination, the internal electric field generated by the separation of photogenerated carriers in BiVO4 is further reinforced by tourmaline’s inherent polarization. This synergistic effect creates localized surface charges on tourmaline that function analogously to a semiconductor heterojunction, effectively promoting the migration of electrons and holes.

As illustrated schematically in

Figure 5d, the interfacial electron transfer between tourmaline and BiVO

4 is governed by their difference in work functions. Because the work function of tourmaline (

ϕT) is higher than that of BiVO

4 (

ϕB), electrons spontaneously transfer from BiVO

4 to tourmaline until the Fermi levels equilibrate. This charge redistribution induces downward band bending in BiVO

4 and establishes a built-in electric field at the interface. A Helmholtz double layer is formed, wherein the tourmaline surface becomes negatively charged while the adjacent BiVO

4 surface becomes positively charged. Together with tourmaline’s intrinsic spontaneous polarization, this interfacial electric field drives the spatial separation of photogenerated carriers, causing electrons and holes to accumulate at opposite regions of the composite. The electrons on the tourmaline side readily react with molecular oxygen to generate superoxide radicals (·O

2−), which actively contribute to the enhanced antibacterial activity.

The enhanced charge-transfer behavior is further supported by the photocurrent measurements shown in

Figure 5c. All samples exhibit negligible current in the dark, confirming that the photocurrent originates exclusively from photoexcitation. Upon illumination, the photocurrent increases significantly, with the 6 wt.% tourmaline/BiVO

4 composite showing nearly twice the current density of pristine BiVO

4. This substantial enhancement demonstrates that the introduction of tourmaline effectively increases the photogenerated carrier density and improves their separation and transport, thereby validating the role of tourmaline in boosting the photocatalytic antibacterial performance of the composite.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Chemicals and Reagents

Tourmaline powder (10,000 mesh; Hebei, China), bismuth nitrate pentahydrate (Bi(NO3)3·5H2O, AR), ammonium metavanadate (NH4VO3, AR), citric acid monohydrate (C6H8O7·H2O, AR), ammonia solution (NH3·H2O, 25 wt.%, AR), and deionized water were used throughout the study. All reagents were of analytical grade and used as received without further purification.

4.2. Synthesis of Tourmaline/BiVO4 Composite Materials

Tourmaline powder was pre-treated to enhance its surface polarity. Specifically, the powder was dispersed in a 1 M HCl aqueous solution and subjected to ultrasonic treatment for 30 min. The resulting suspension was repeatedly washed with deionized water until a neutral pH was achieved, followed by drying at 60 °C in air for 6 h [

18].

The Tourmaline/BiVO4 composite materials were synthesized via a modified sol–gel method. First, 0.01 mol of Bi(NO3)3·5H2O and 0.02 mol of citric acid monohydrate were dissolved in 50 mL of 2.0 mol·L−1 HNO3 under constant magnetic stirring to form solution A. Simultaneously, 0.01 mol of NH4VO3 and 0.02 mol of citric acid monohydrate were dissolved in deionized water to obtain solution B. Solution A was then added dropwise to solution B under continuous stirring to yield solution C. Pre-treated tourmaline powder was subsequently added to solution C at various mass ratios. The pH of the suspension was adjusted to 7.0 using 25 wt.% ammonia solution, and the mixture was maintained at 80 °C in a water bath with constant stirring until a gelatinous precursor formed. This precursor was thermally treated at 550 °C for 4 h in air. After natural cooling to room temperature, the resulting yellow powders were collected.

Composites with various tourmaline loadings were synthesized using similar procedure and labeled as 2 wt.%, 6 wt.%, and 10 wt.% Tourmaline/BiVO4, corresponding to the respective mass ratios.

4.3. Characterization

The crystalline phase compositions of the synthesized samples were analyzed via X-ray diffraction (XRD) using a DX-2700 diffractometer (Dandong Haoyuan, China) equipped with Cu Kα radiation (λ = 0.15418 nm), operating over a 2θ range of 5–60°. Surface morphology and microstructural features were examined using scanning electron microscopy (SEM) on a JSM-6390F instrument (JEOL, Tokyo, Japan) at an accelerating voltage of 20.0 kV. Optical absorption characteristics were analyzed using UV–Vis diffuse reflectance spectroscopy (DRS) on a Hitachi U3900H spectrophotometer (Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan), with band gap energies estimated from Tauc plots. Photoluminescence (PL) spectra were recorded using a Hitachi F-4600 spectrophotometer under excitation from a continuous Xe lamp (λ = 325 nm, 150 mW) to evaluate charge carrier recombination behavior.

The local bonding environments and vibrational modes of the composites were further investigated via Raman spectroscopy and Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy. Raman measurements were performed using a Thermo DXR Raman microscope system (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) equipped with a 532 nm laser source, collecting spectra in the 100–1200 cm−1 range. FTIR analysis was conducted using a Nicolet iS50 spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) to assess functional group interactions and confirm the presence of constituent phases.

4.4. Photocatalytic Performance Investigation

The photocatalytic antibacterial performance of the synthesized composites was evaluated by measuring the inactivation efficiency of representative bacterial strains. Antibacterial assays were performed under visible-light irradiation to simulate practical environmental conditions. An 800 W xenon lamp (PLS-SXE300, PerfectLight, Dresden, Germany) equipped with a 420 nm cutoff filter served as the visible-light source.

Escherichia coli (Gram-negative) and

Staphylococcus aureus (Gram-positive) were selected as model bacterial species for photocatalytic disinfection studies [

19]. Bacterial stock suspensions were prepared with concentrations of 10

6–10

7 colony-forming units per milliliter (cfu/mL).

In each experiment, 50 mg of the photocatalyst was dispersed in 49.5 mL of sterilized natural seawater, followed by the addition of 500 μL of bacterial suspension. The resulting mixture was transferred into 50 mL quartz tubes. Before illumination, the suspension was stirred magnetically in the dark for 60 min to establish adsorption–desorption equilibrium between the bacterial cells and photocatalyst surface. Subsequent visible-light irradiation was carried out under continuous stirring. At hourly intervals over a 3-h exposure period, 1 mL aliquots were extracted, serially diluted using sterile seawater, and plated (100 μL per plate) on Luria–Bertani (LB) agar under aseptic conditions [

19]. The inoculated plates were incubated at 37 °C for 18 h, after which the number of viable bacterial colonies (cfu) was enumerated. The photocatalytic antibacterial efficiency was calculated using the following equations:

where

N0 and

Nt denote the number of bacterial colonies in the control (absence of photocatalyst) and in the photocatalyst-treated sample at time

t, respectively.

Moreover, photoelectrochemical (PEC) measurements were conducted to evaluate the photo-to-current conversion efficiency, charge transfer kinetics, and structural–electronic variations in the photocatalytic materials under visible-light irradiation. A conventional three-electrode configuration was employed, comprising a BiVO4-based working electrode, an Ag/AgCl reference electrode (saturated in 3.0 mol·L−1 KCl), and a platinum foil serving as the counter electrode. The measurements were performed using a CompactStat.h10800 electrochemical workstation (Ivium Technologies, Eindhoven, The Netherlands). Photocurrent response curves were recorded under visible-light illumination using a 300 W xenon lamp equipped with a 420 nm cutoff filter (λ ≥ 420 nm) to exclude UV radiation. Aqueous solutions of 1 mol·L−1 Na2SO4 and Na2SO3 were employed as the electrolyte media in all electrochemical experiments to ensure ionic conductivity and minimize interfacial resistances.