Texturing (Na0.5Bi0.5)TiO3-KNbO3-SrTiO3 Electrostrictive Ceramics by Templated Grain Growth Using (Na0.5Bi0.5)TiO3 Platelets

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

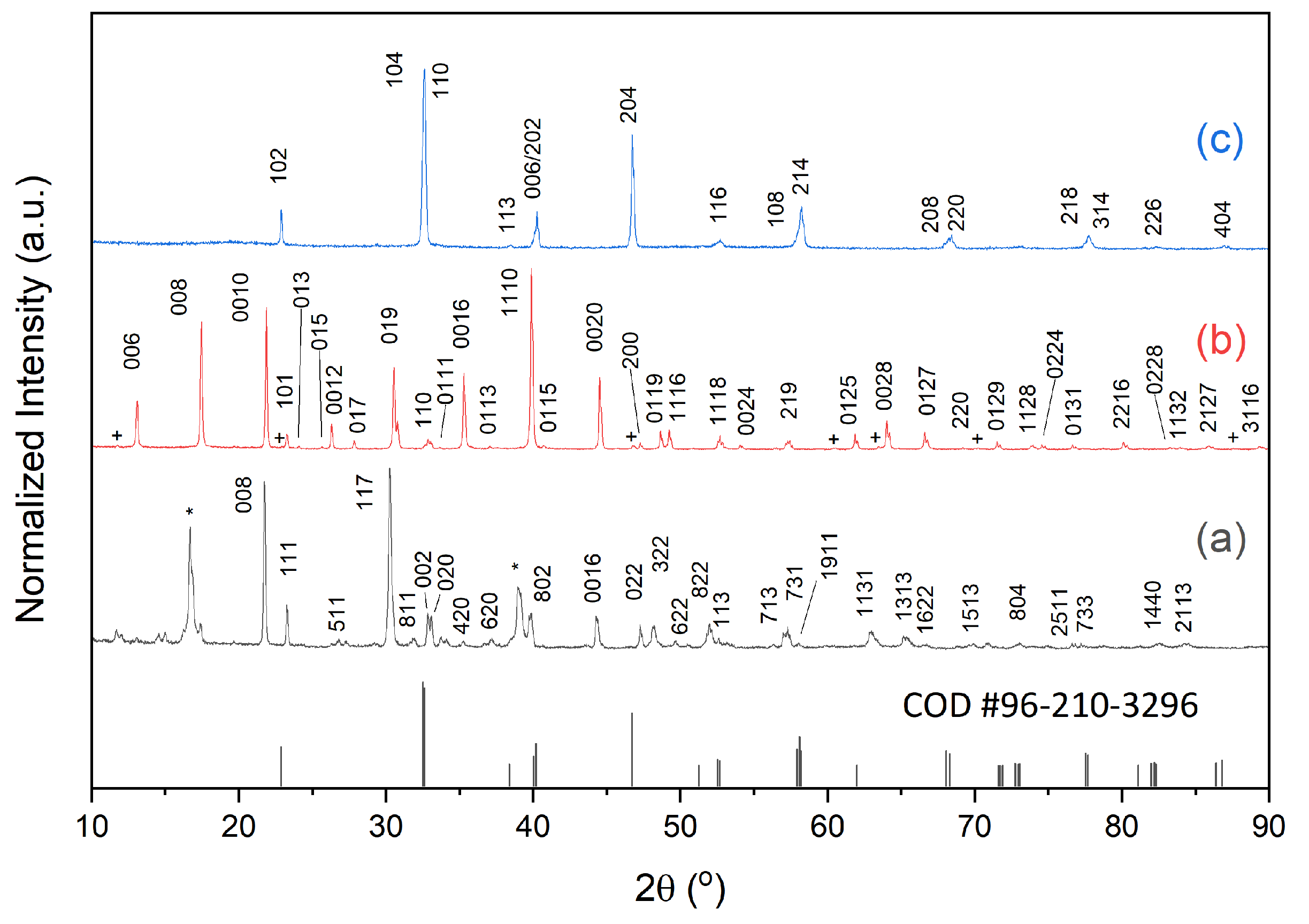

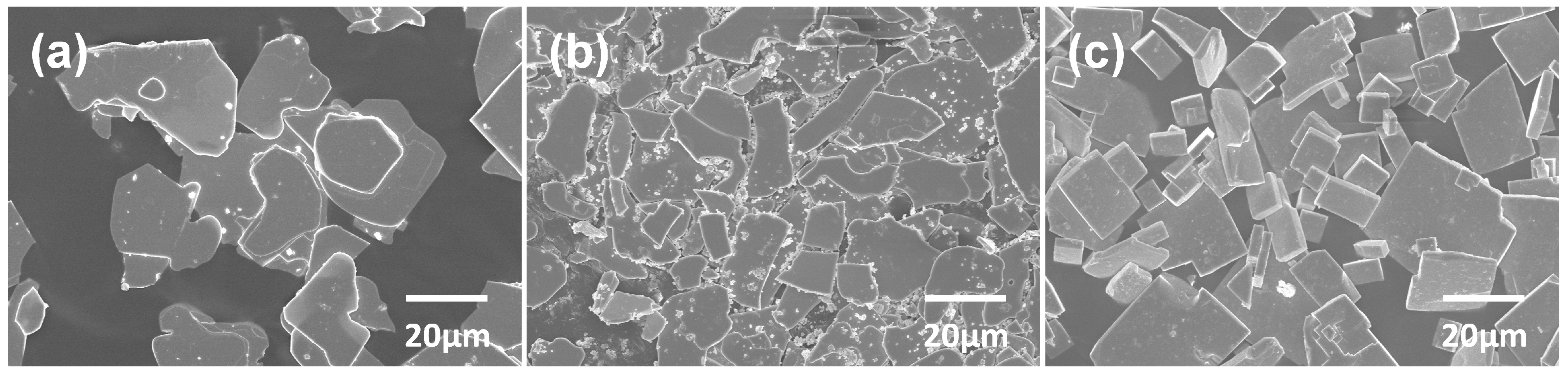

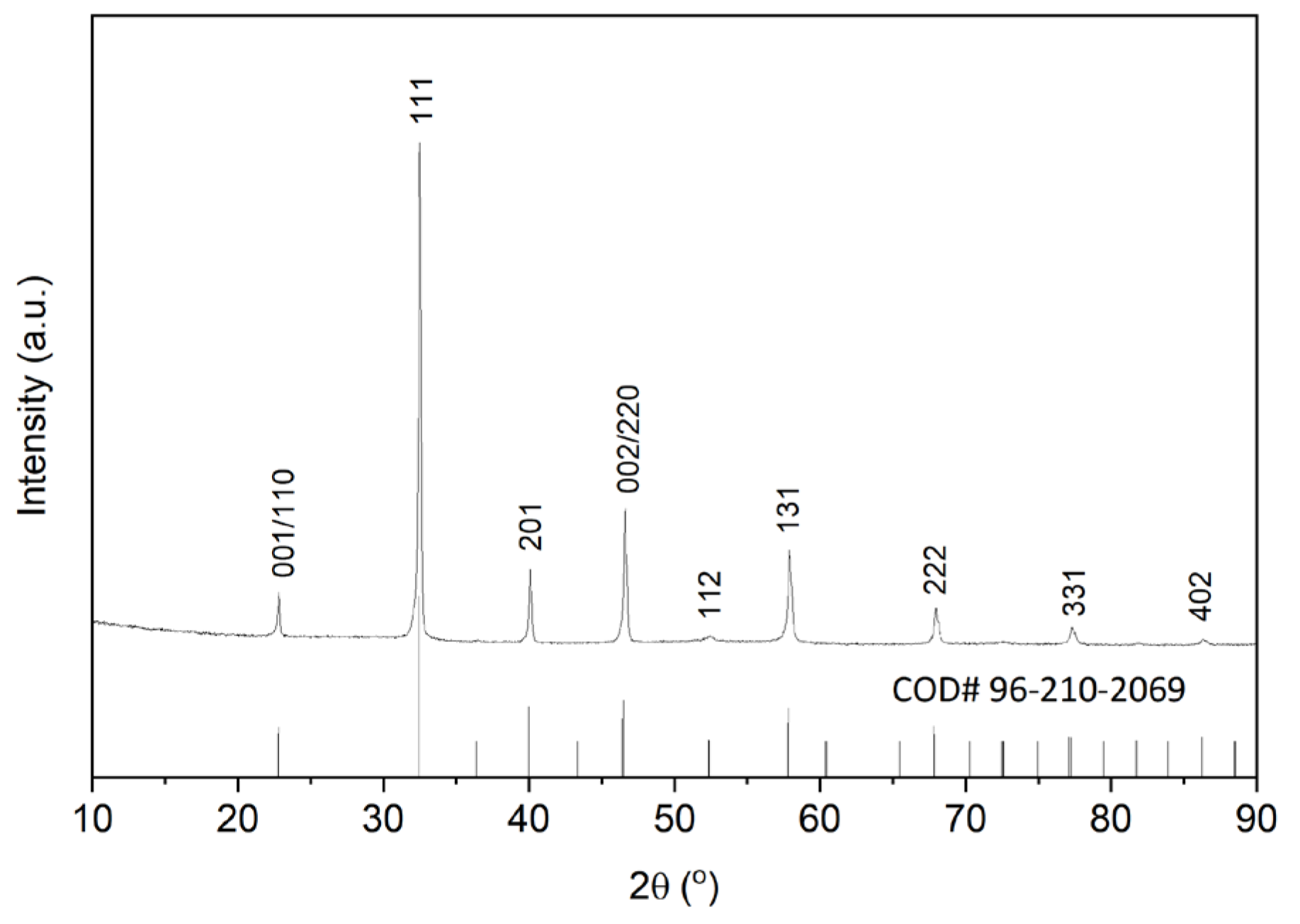

2.1. (Na0.5Bi0.5)TiO3 Platelet Preparation

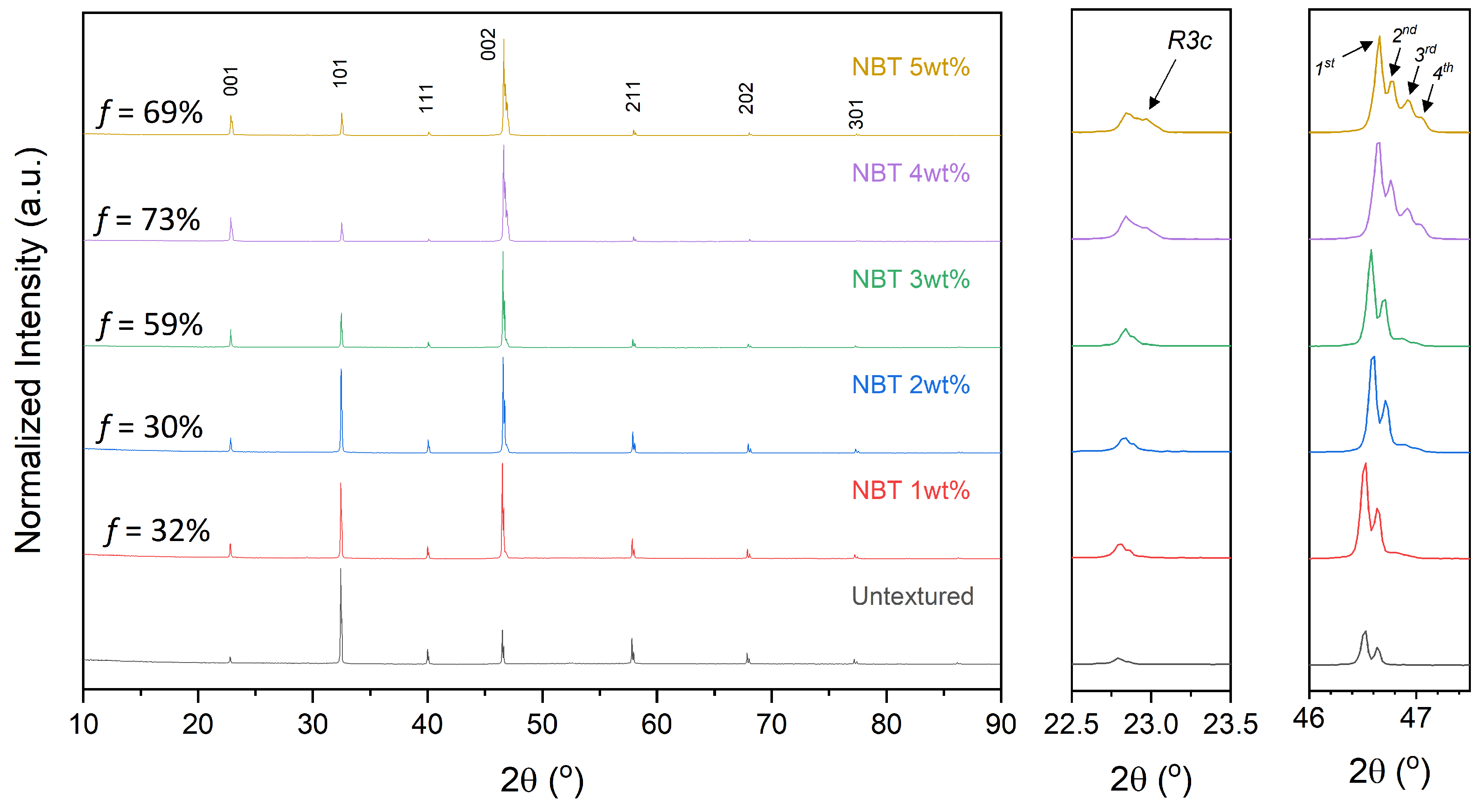

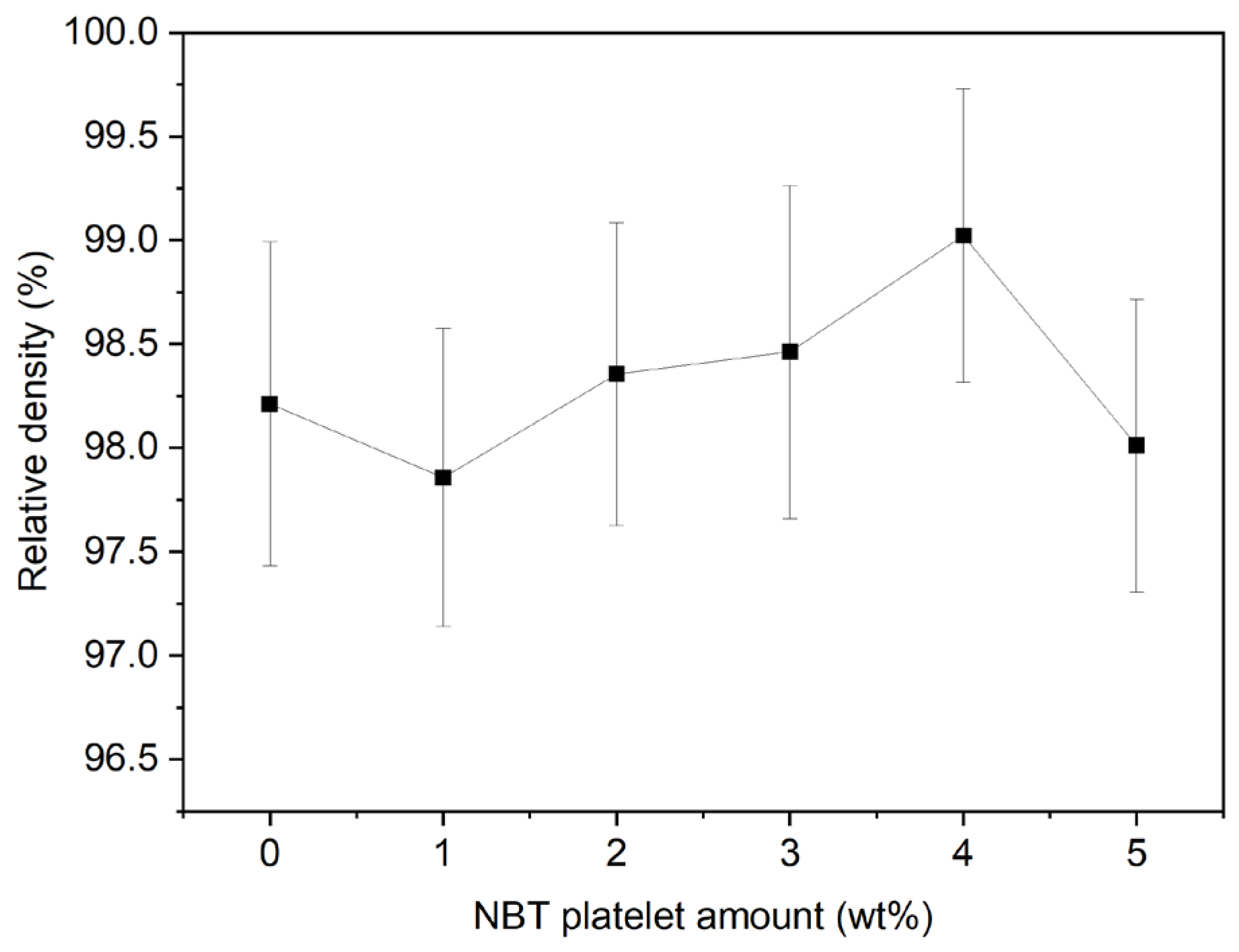

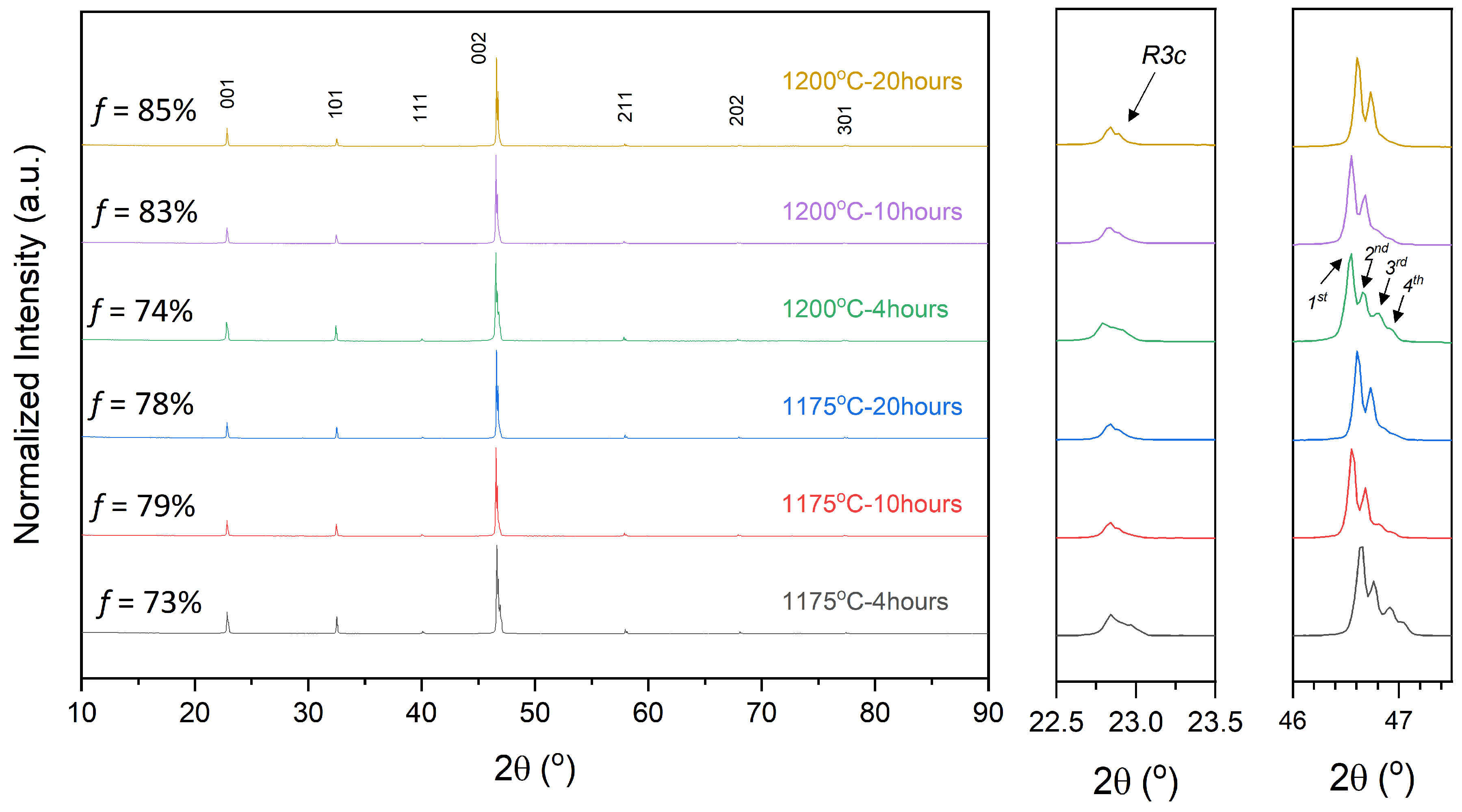

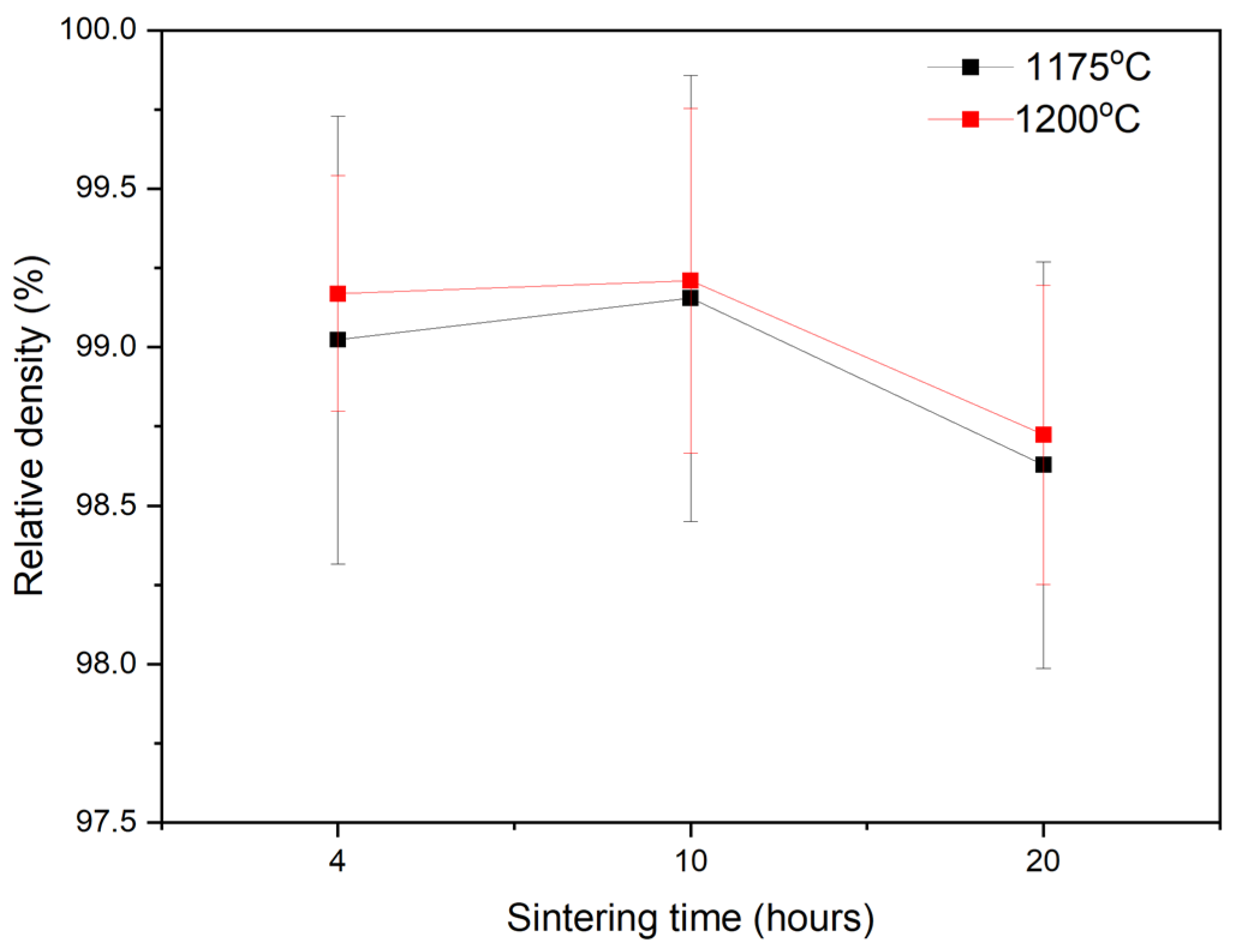

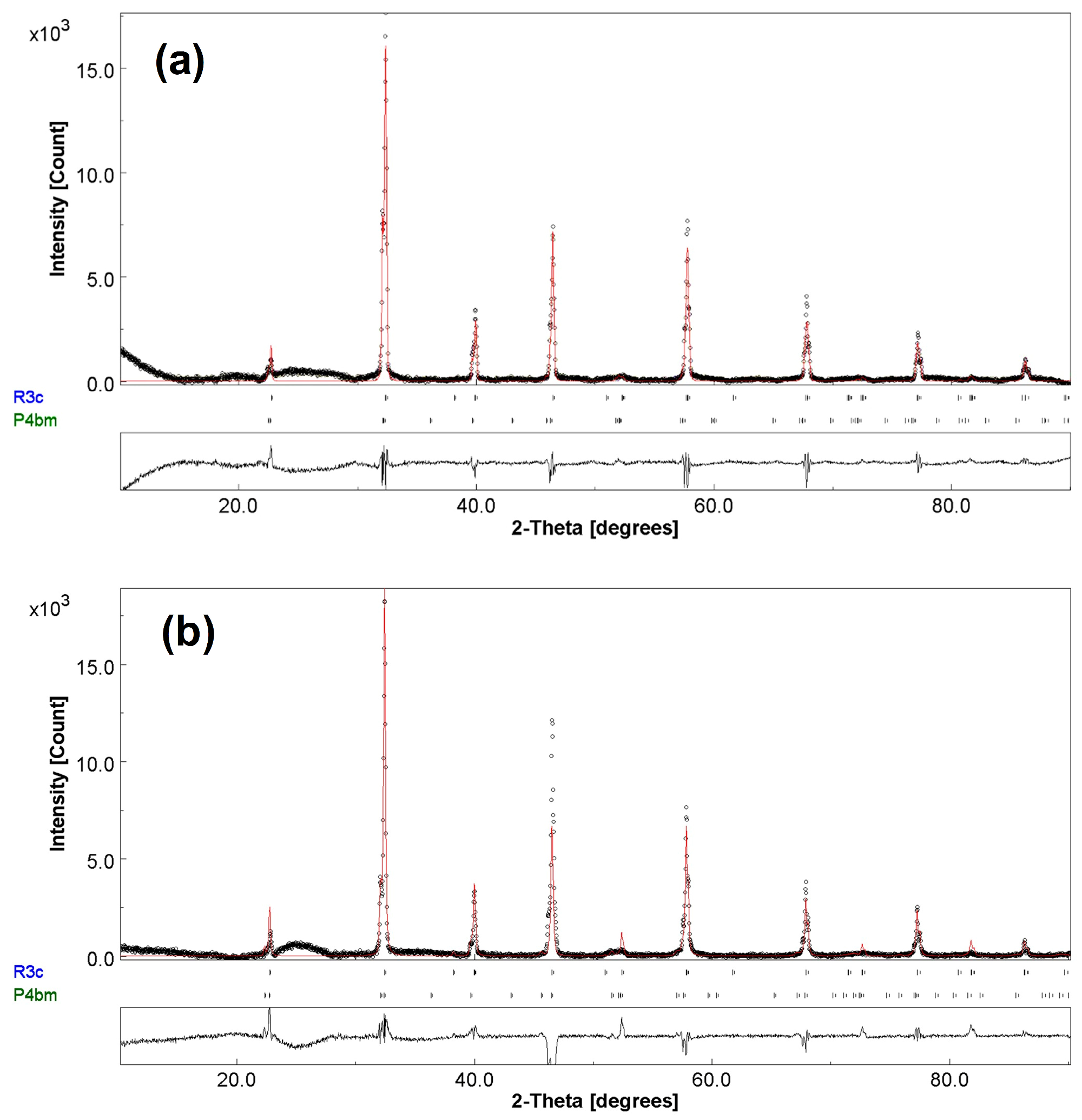

2.2. Textured Ceramic Development

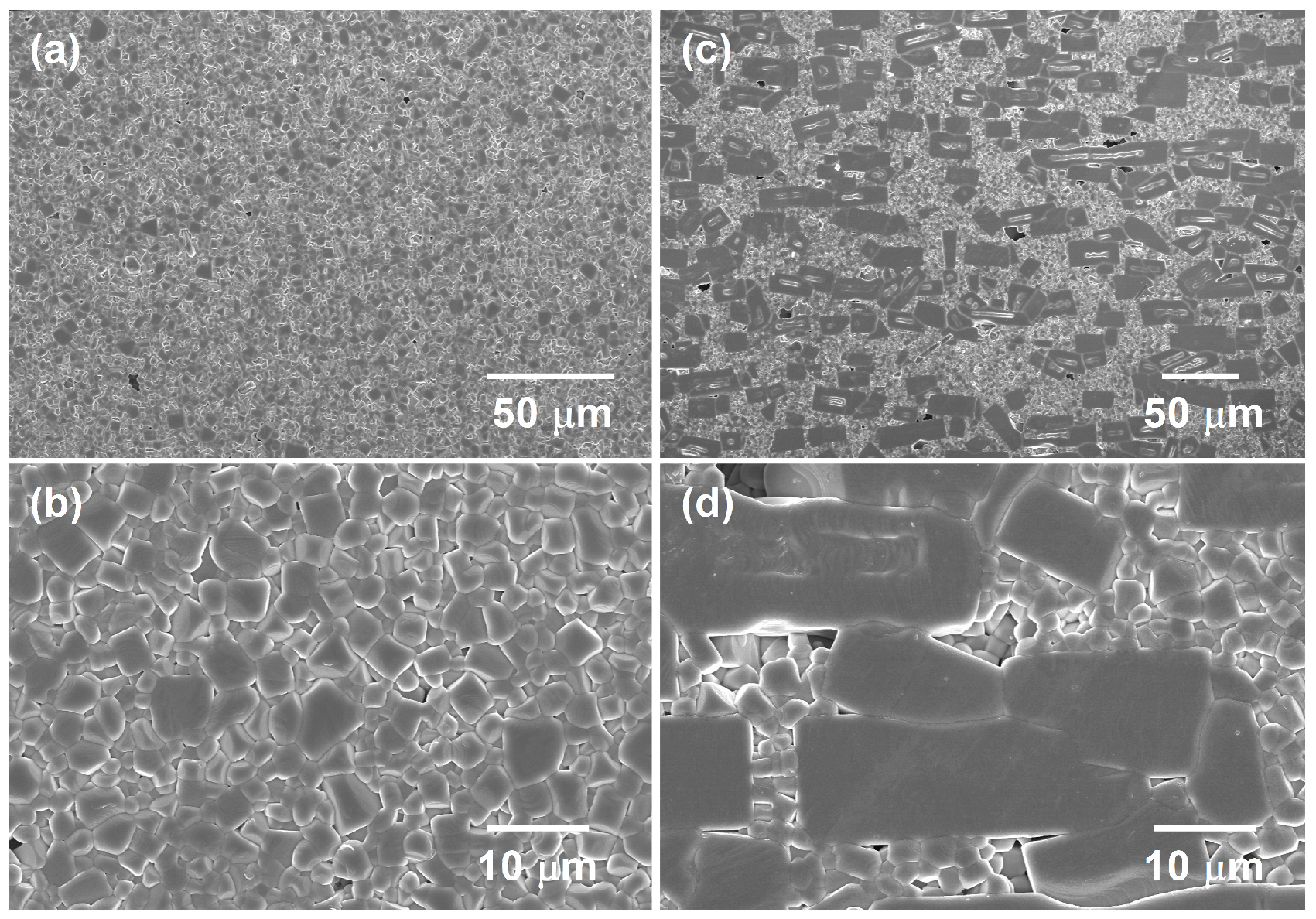

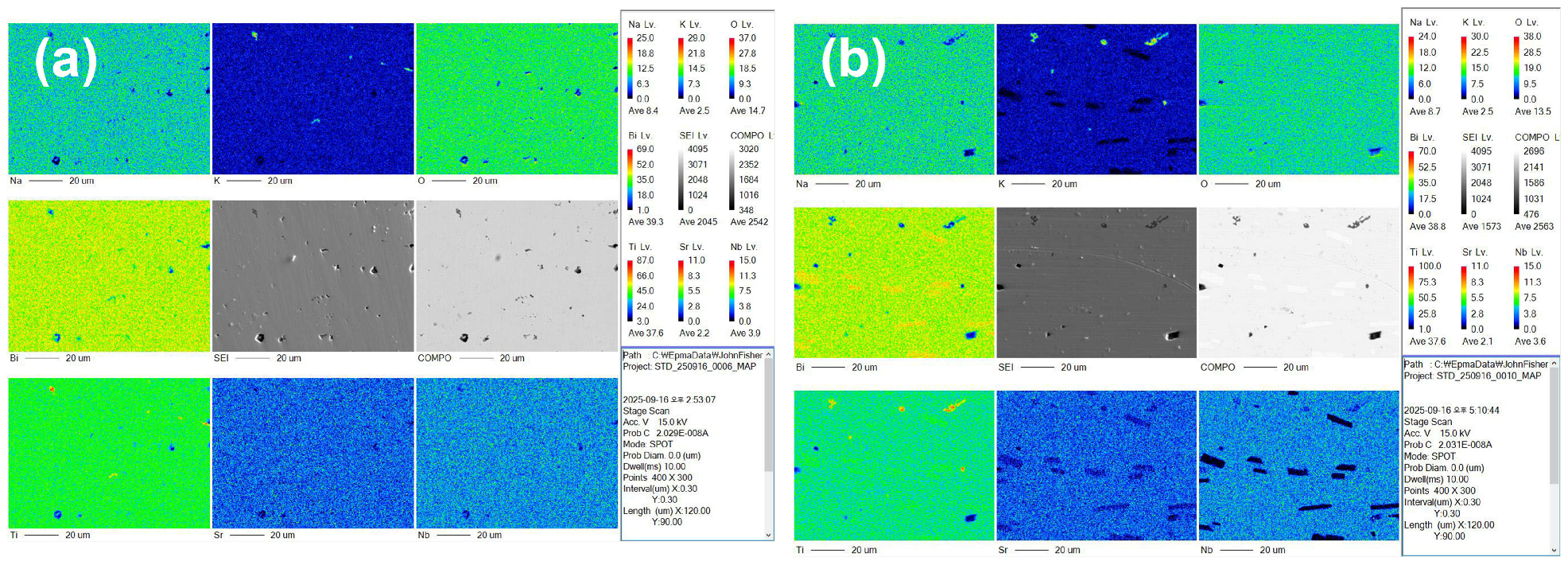

2.3. Microstructure

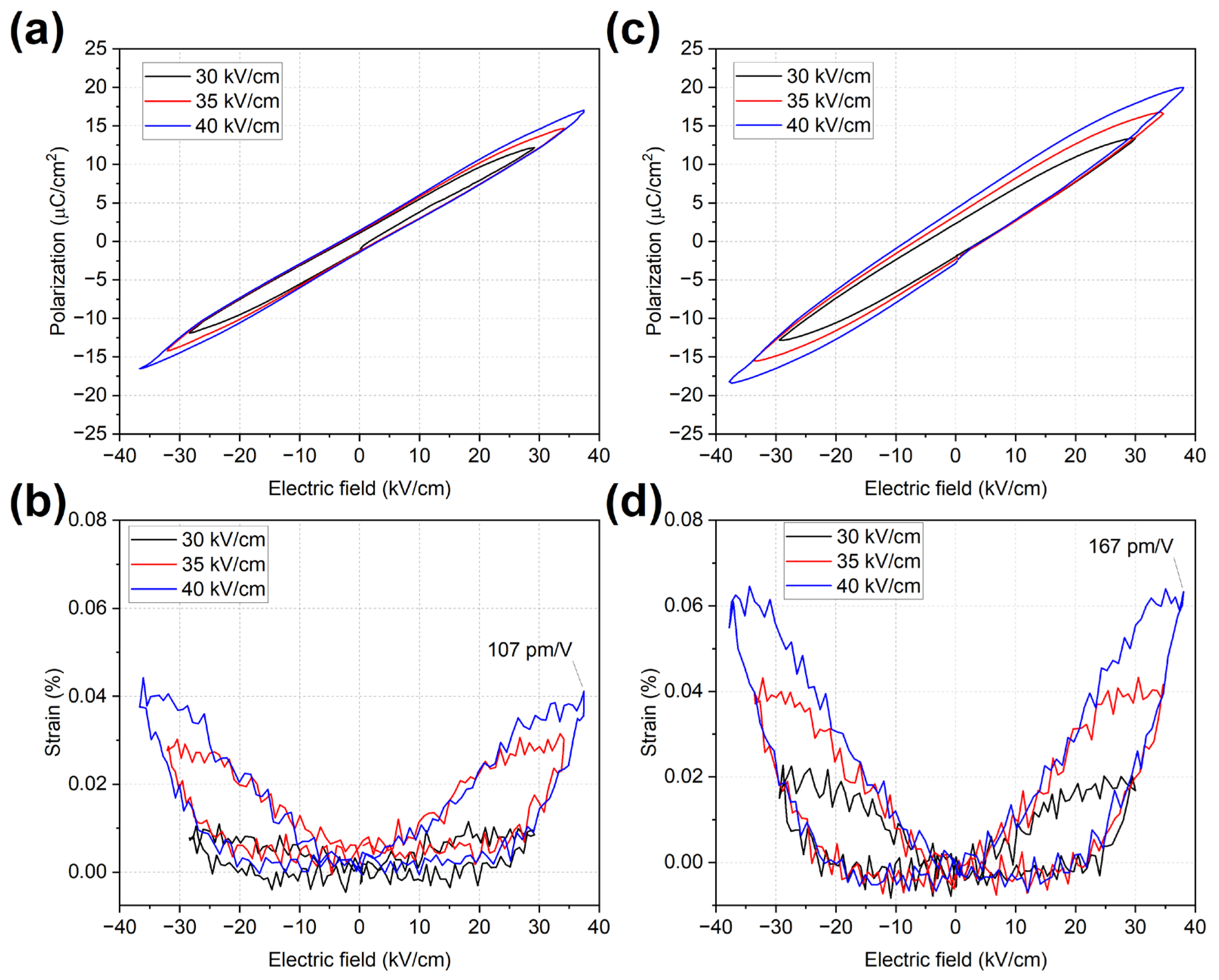

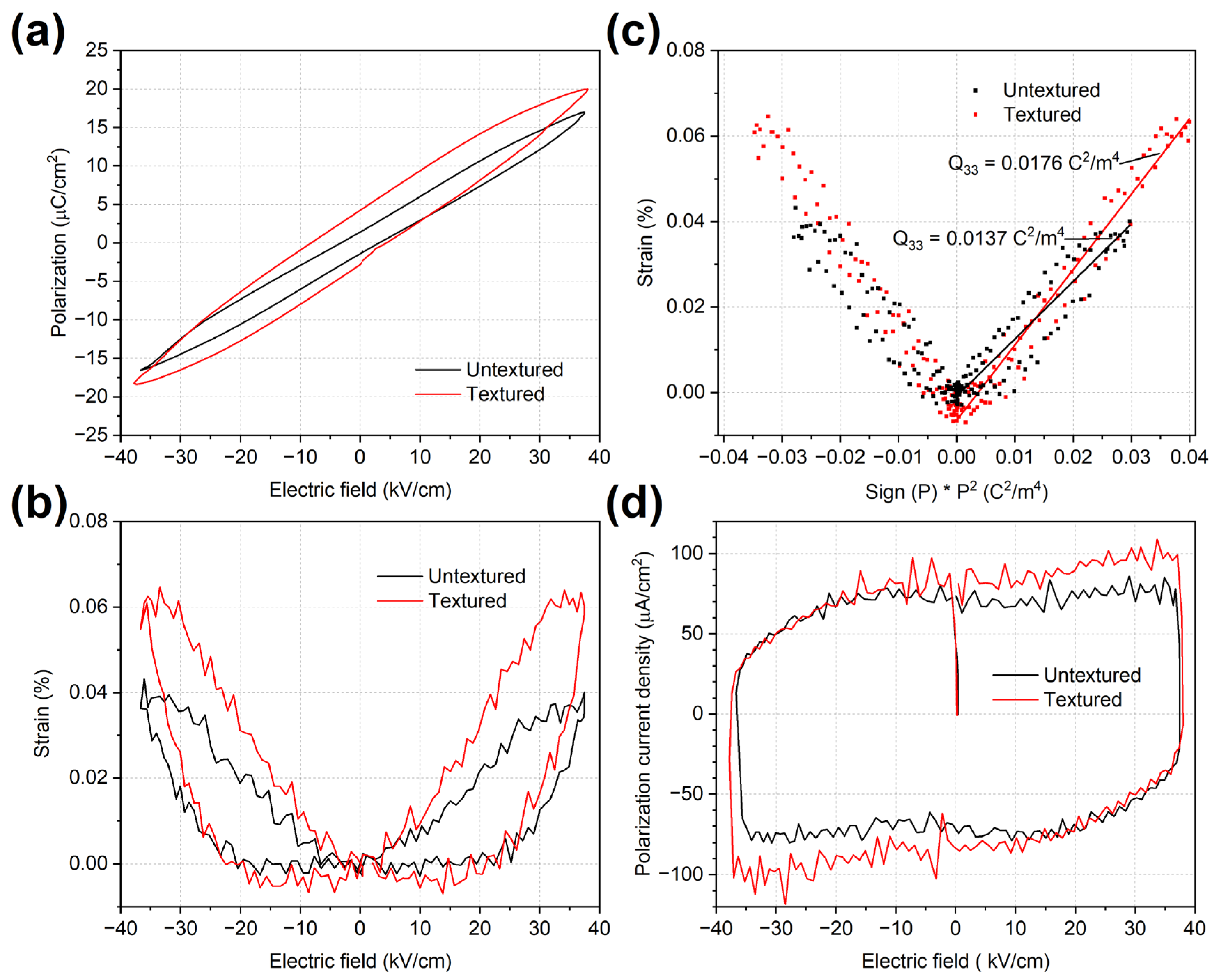

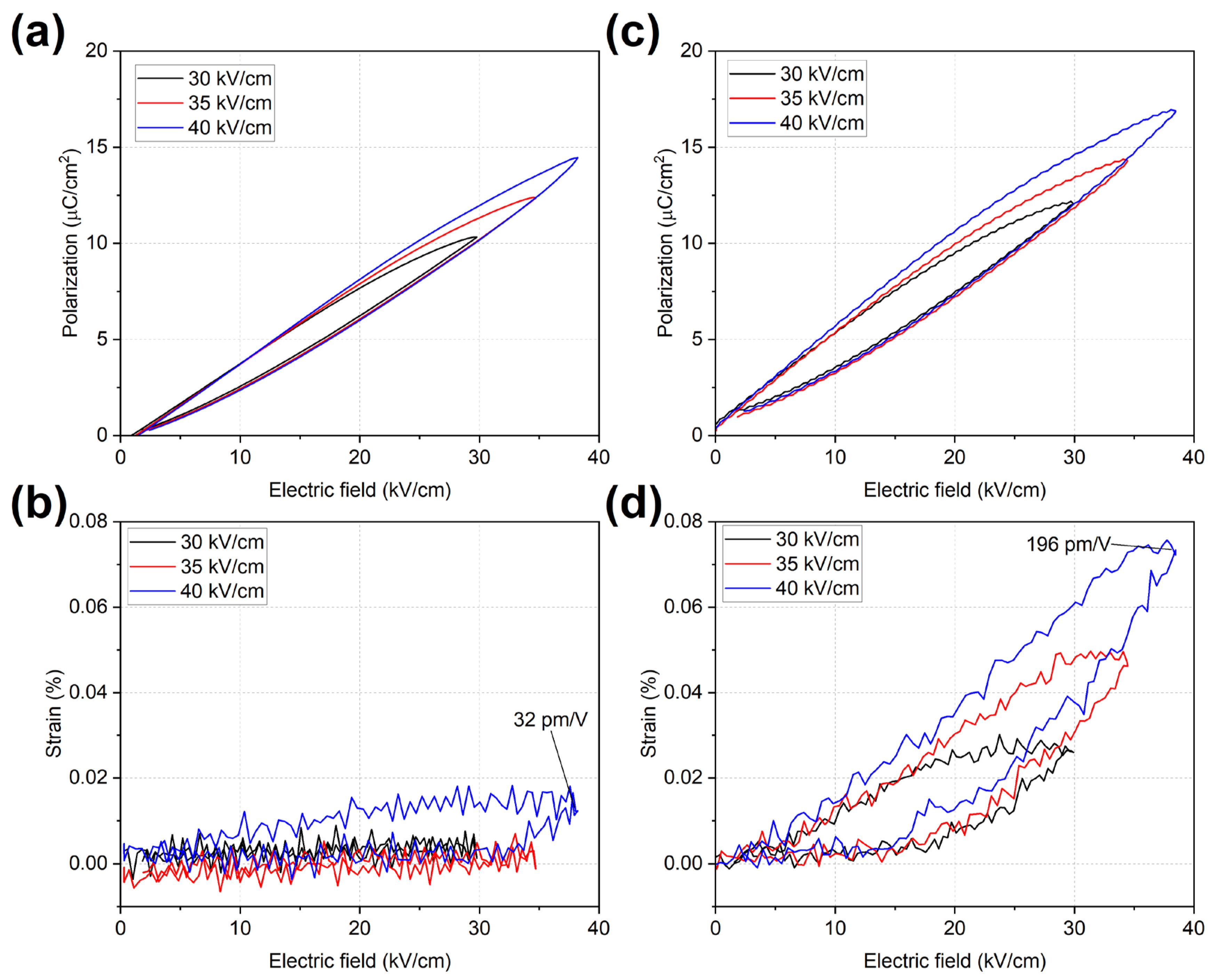

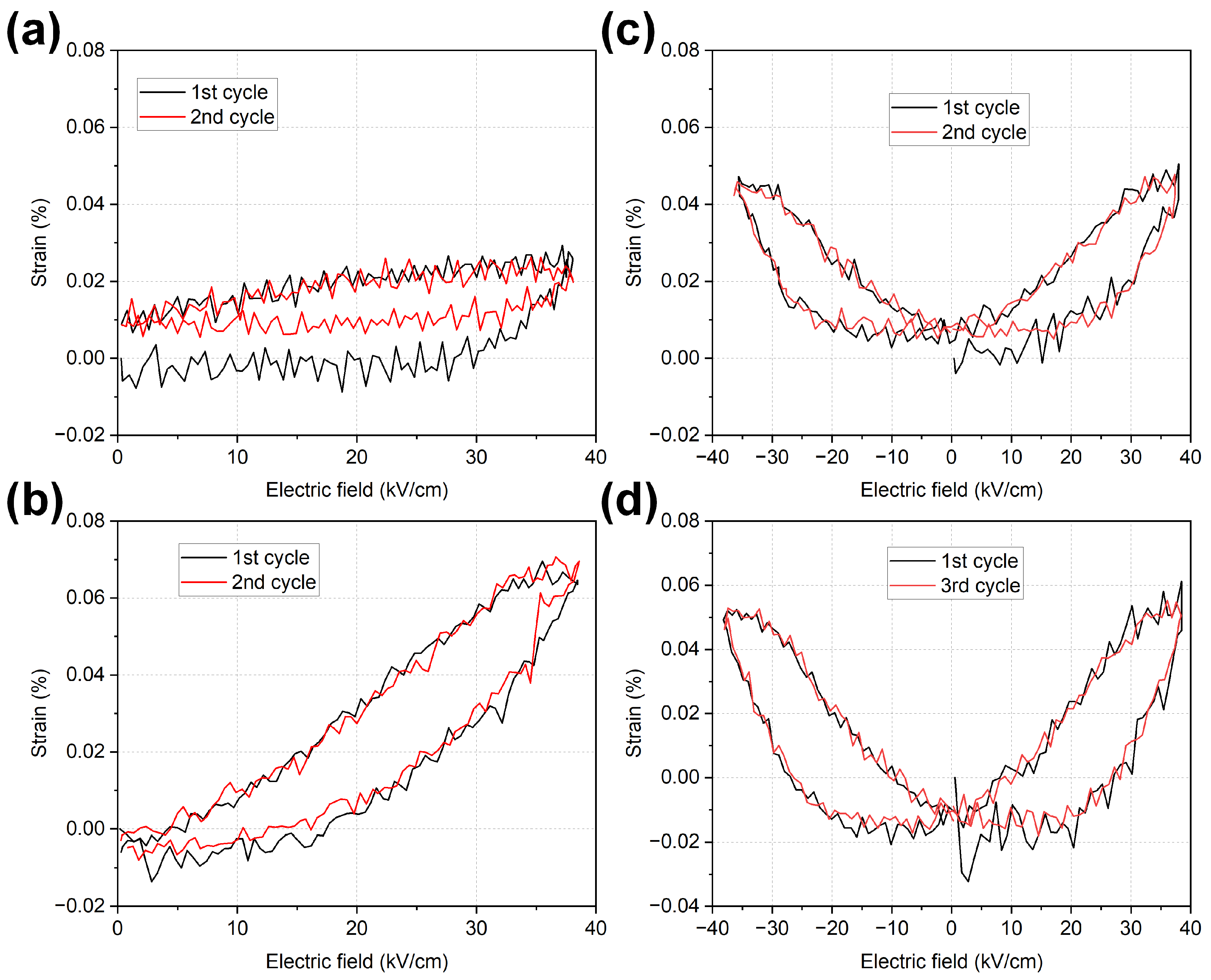

2.4. Polarization and Strain Behaviour

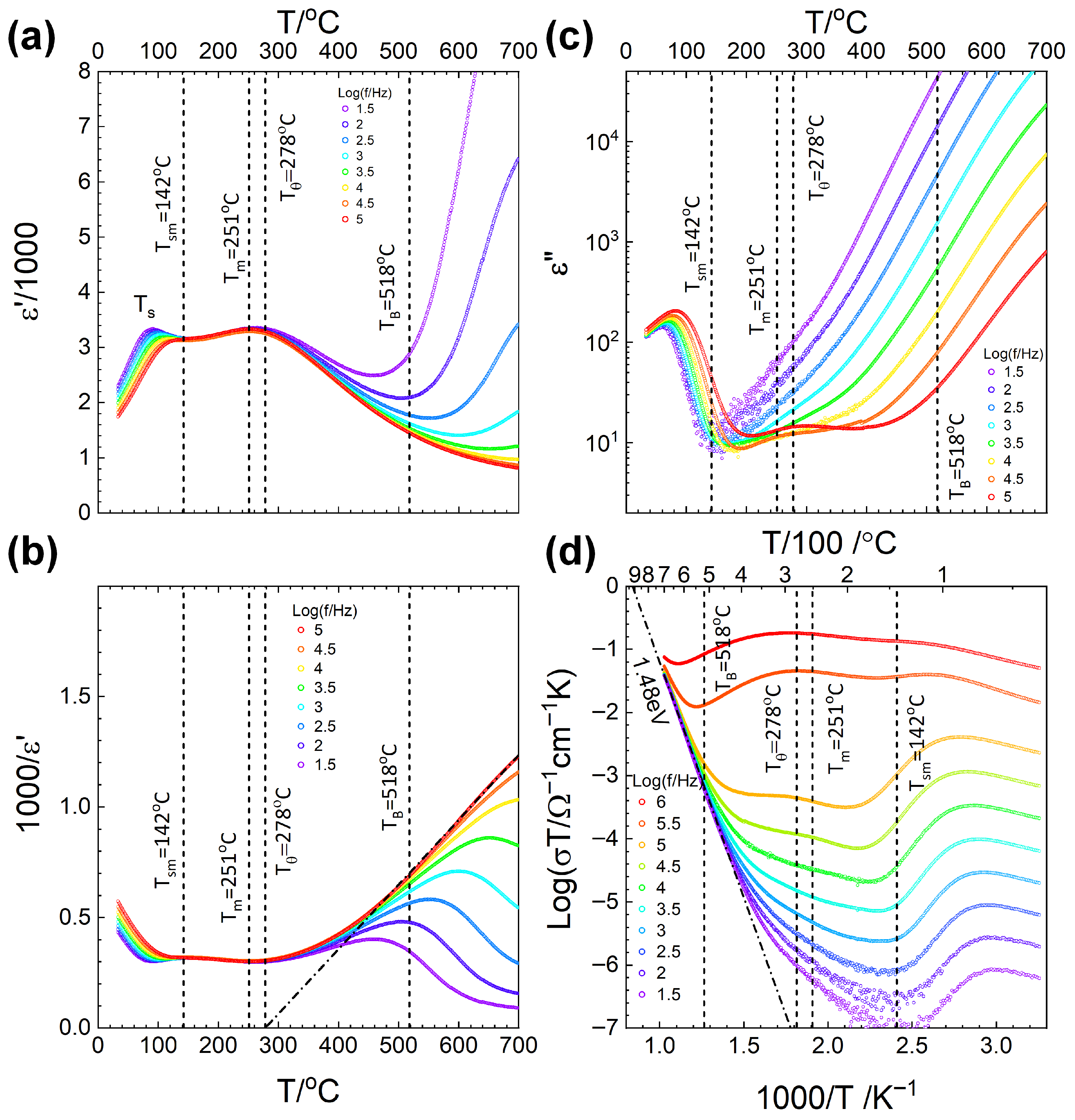

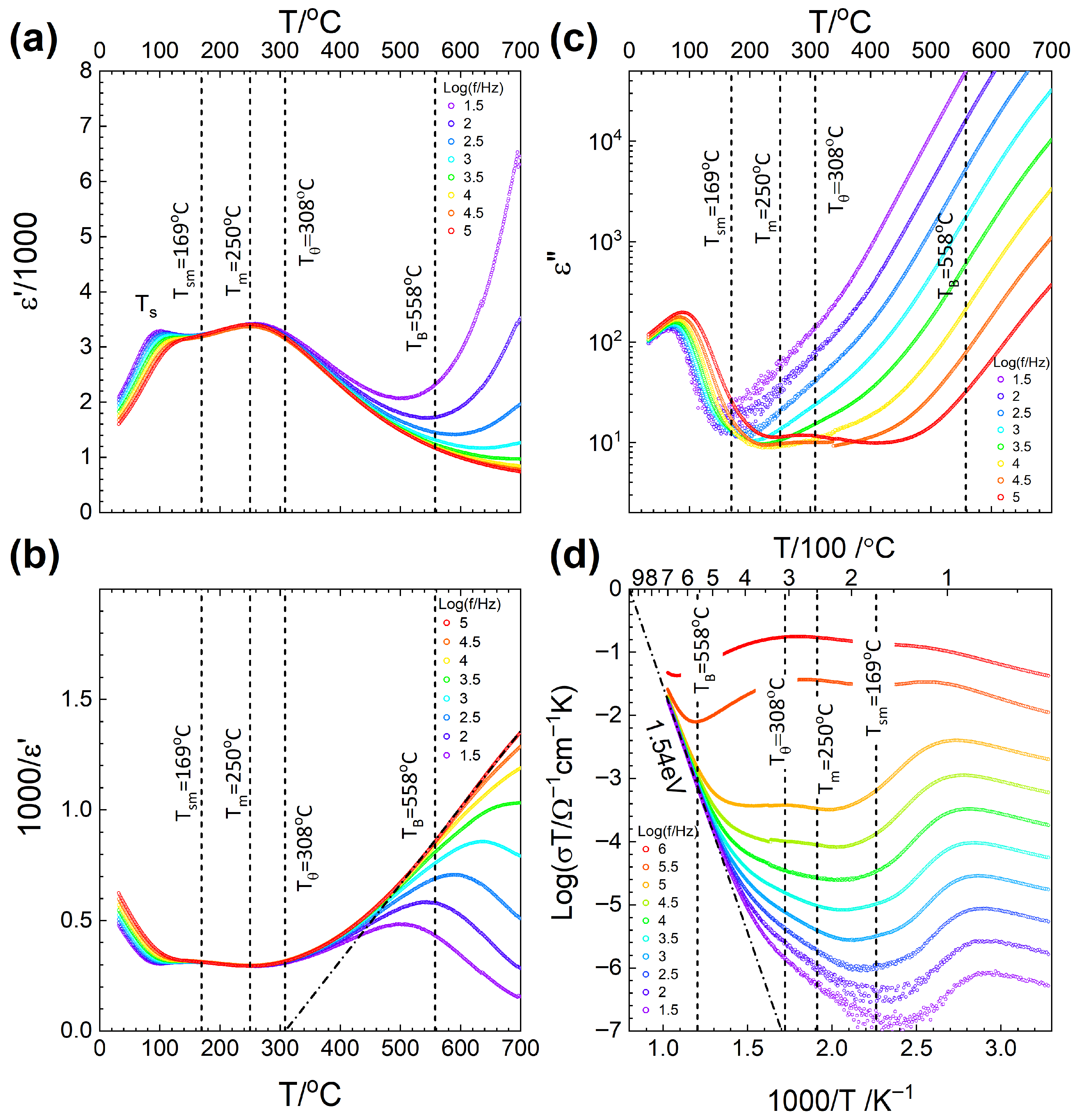

2.5. Dielectric Property Measurements

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. (Na0.5Bi0.5)TiO3 Platelet Preparation

3.2. Preparation of 0.90(Na0.5Bi0.5)TiO3-0.08KNbO3-0.02SrTiO3 Powder

3.3. Textured Ceramic Development

3.4. Characterization

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Taniguchi, N. Current Status in, and Future Trends of, Ultraprecision Machining and Ultrafine Materials Processing. CIRP Ann. 1983, 32, 573–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coutte, J.; Debus, J.C.; Dubus, B.; Bossut, R.; Granger, C.; Haw, G. Finite Element Modeling of PMN electrostrictive Materials and Application to the Design of Transducers. In Proceedings of the 1998 IEEE International Frequency Control Symposium (Cat. No.98CH36165), Pasadena, CA, USA, 29 May 1998; pp. 703–708. [Google Scholar]

- Uchino, K.; Tsuchiya, Y.; Nomura, S.; Sato, T.; Ishikawa, H.; Ikeda, O. Deformable Mirror Using The PMN Electrostrictor. Appl. Opt. 1981, 20, 3077–3080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nomura, L.S.; Gomi, M.; Uchino, K. Bistable Optical Device with a PMN-Based Ceramic Electrostrictor. Ferroelectrics 1985, 63, 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nomura, S.; Uchino, K. Recent Applications of PMN-based Electrostrictors. Ferroelectrics 1983, 50, 197–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, M.-J.; Rehrig, P.W.; Kucera, J.P.; Park, S.-E.; Hackenberger, W.S. Comparison of Actuator Properties for Piezoelectric and Electrostrictive Materials. In Proceedings of the SPIE 3992, Smart Structures and Materials 2000: Active Materials: Behavior and Mechanics, Newport Beach, CA, USA, 6–9 March 2000; pp. 80–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, S.; Sirohi, J.; Wang, G.; Wereley, N.M. Comparison of Piezoelectric, Magnetostrictive, and Electrostrictive Hybrid Hydraulic Actuators. J. Intell. Mater. Syst. Struct. 2007, 18, 1035–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q.; Meng, X.; Li, D.; Yao, Z.; Sun, H.; Hao, H.; Liu, H.; Zhang, S. Ultrahigh Electrostrictive Strain and Its Response to Mechanical Loading in Nd-doped PMN-PT Ceramics. Acta Mater. 2024, 266, 119695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Li, F. A Low-Working-Field (2 kV/mm), Large-Strain (>0.5%) Piezoelectric Multilayer Actuator Based On Periodically Orthogonal Poled PZT Ceramics. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2018, 272, 212–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, J.; Zuo, R. Giant Electrostrains Accompanying The Evolution of A Relaxor Behavior in Bi(Mg,Ti)O3-PbZrO3-PbTiO3 Ferroelectric Ceramics. Acta Mater. 2013, 61, 3687–3694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchino, K.; Nomura, S.; Cross, L.E.; Newnham, R.E.; Jang, S.J. Review Electrostrictive Effect in Perovskites and Its Transducer Applications. J. Mater. Sci. 1981, 16, 569–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Jin, L.; Xu, Z.; Zhang, S. Electrostrictive Effect in Ferroelectrics: An Alternative Approach to Improve Piezoelectricity. Appl. Phys. Rev. 2014, 1, 011103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santucci, S.; Esposito, V. Electrostrictive Ceramics and Their Applications. In Encyclopedia of Materials: Technical Ceramics and Glasses: Volume 1–3; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; Volume 3, pp. 369–374. [Google Scholar]

- Hao, J.; Li, W.; Zhai, J.; Chen, H. Progress in High-Strain Perovskite Piezoelectric Ceramics. Mater. Sci. Eng. R Rep. 2019, 135, 1–57. [Google Scholar]

- Rödel, J.; Webber, K.G.; Dittmer, R.; Jo, W.; Kimura, M.; Damjanovic, D. Transferring Lead-Free Piezoelectric Ceramics into Application. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2015, 35, 1659–1681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, P.; Liu, K.; Ma, W.; Tan, H.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, L.; Zhou, C.; Salamon, D.; Zhang, S.T.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Progress and Perspective of High Strain NBT-based Lead-free Piezoceramics and Multilayer Actuators. J. Mater. 2021, 7, 508–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.; Liu, G.; Zhao, C.; Huang, Y.; Li, Z.; Zhang, X.; Wang, K.; Wu, J. Perovskite Na0.5Bi0.5TiO3: A Potential Family of Peculiar Lead-free Electrostrictors. J. Mater. Chem. A Mater. 2019, 7, 13658–13670. [Google Scholar]

- Dunce, M.; Birks, E.; Antonova, M.; Bikse, L.; Dutkevica, S.; Freimanis, O.; Livins, M.; Eglite, L.; Smits, K.; Sternberg, A. Influence of Sintering Temperature on Microstructure of Na0.5Bi0.5TiO3 Ceramics. J. Alloys Compd. 2021, 884, 160955. [Google Scholar]

- Hiruma, Y.; Nagata, H.; Takenaka, T. Thermal Depoling Process and Piezoelectric Properties of Bismuth Sodium Titanate Ceramics. J. Appl. Phys. 2009, 105, 084112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Zhu, C.; Zhao, S. Good Energy Storage Properties of Na0.5Bi0.5TiO3 Thin Films. J. Alloys Compd. 2021, 869, 159366. [Google Scholar]

- Suchanicz, J.; Nowakowska-Malczyk, M.; Kania, A.; Budziak, A.; Kluczewska-Chmielarz, K.; Czaja, P.; Sitko, D.; Sokolowski, M.; Niewiadomski, A.; Kruzina, T.V. Effects of Electric Field Poling on Structural, Thermal, Vibrational, Dielectric and Ferroelectric Properties of Na0.5Bi0.5TiO3 Single Crystals. J. Alloys Compd. 2021, 854, 157227. [Google Scholar]

- Ramesh Babu, P.; Selvamani, R.; Singh, G.; Kalainathan, S.; Babu, R.; Tiwari, V.S. Growth, Mechanical and Domain Structure Studies of Na0.5Bi0.5TiO3 Single Crystal Grown by Flux Growth Method. J. Alloys Compd. 2017, 721, 199–204. [Google Scholar]

- Rödel, J.; Jo, W.; Seifert, K.T.P.; Anton, E.M.; Granzow, T.; Damjanovic, D. Perspective on the development of lead-free piezoceramics. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2009, 92, 1153–1177. [Google Scholar]

- Duong, T.A.; Han, H.-S.; Hong, Y.-H.; Park, Y.-S.; Nguyen, H.T.K.; Dinh, T.H. Dielectric and Piezoelectric Properties of Bi1/2Na1/2TiO3–SrTiO3 Lead–free Ceramics. J. Electroceram. 2018, 41, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, G.O.; Thomas, P.A. Investigation of the structure and phase transitions in the novel A-site substituted distorted perovskite compound Na0.5Bi0.5TiO3. Acta Crystallogr. B. 2002, 58, 168–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kruzina, T.V.; Sidak, V.M.; Trubitsyn, M.P.; Popov, S.A.; Tuluk, A.Y.; Suchanicz, J. Impedance Spectra of As-Grown and Heat Treated Na0.5Bi0.5TiO3 Crystals. Acta Phys. Pol. A 2018, 133, 816–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aksel, E.; Forrester, J.S.; Kowalski, B.; Deluca, M.; Damjanovic, D.; Jones, J.L. Structure and Properties of Fe-modified Na0.5Bi0.5TiO3 at Ambient and Elevated Temperature. Phys. Rev. B Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 2012, 85, 024121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, G.; Lu, W.; Wang, X.; Liang, F.; Xiao, J. Phase Transition Behaviour and Electromechanical Properties of (Na1/2Bi1/2)TiO3-KNbO3 Lead-free Piezoelectric Ceramics. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2008, 41, 035403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Hall, D.A.; Li, Y.; Murray, C.A.; Tang, C.C. Structural Characterization of The Electric Field-induced Ferroelectric Phase in Na0.5Bi0.5TiO3 -KNbO3 Ceramics. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2016, 36, 4015–4021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, X.; Li, H.; Zhou, J.; Liu, H.; Fang, J. Giant Electrostrain under Low Driving Field in Bi1/2Na1/2TiO3-SrTiO3 Ceramics for Actuator Applications. Ceram. Int. 2016, 42, 16153–16159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashif, M.; Bashir, R.; Ullah, S.; Wang, J.; Hu, W. Enhanced Energy Storage Properties of 0.7Bi0.5Na0.5TiO3 -0.3SrTiO3 Ceramic through The Addition of NaNbO3. Ceram. Int. 2021, 47, 30922–30928. [Google Scholar]

- Ünal, M.A.; Karakaya, M.; Irmak, T.; Yıldırım-Özarslan, G.; Murat Avcı, A.; Fulanovic, L.; Suvacı, E.; Adem, U. Electrocaloric Behaviour of Tape Cast Grain Oriented NBT-KBT Ceramics. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2024, 44, 2128–2134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Ya, J.; Xin, Y.; E, L.; Zhao, D.; Zhou, H. Fabrication of Na0.5Bi0.5TiO3-BaTiO3-Textured Ceramics Templated by Plate-like Na0.5Bi0.5TiO3 Particles. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2009, 92, 1607–1609. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhong, C.; Li, L. Enhancement of Piezoelectric and Ferroelectric Performances in (Na0.85K0.15)0.5Bi0.5TiO3 Films with BaTiO3 interlayers. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2018, 38, 1434–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C.; Zhou, X.; Zhou, K.; Chen, C.; Luo, H.; Yuan, X.; Zhang, D. Grain Oriented Na0.5Bi0.5TiO3-BaTiO3 Ceramics with Giant Strain Response Derived from Single-Crystalline Na0.5Bi0.5TiO3-BaTiO3 Templates. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2016, 36, 1377–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Li, Y.; Murray, C.A.; Tang, C.C.; Hall, D.A. Thermally-induced phase transformations in Na0.5Bi0.5TiO3–KNbO3 ceramics. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2017, 100, 3293–3304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berksoy-Yavuz, A.; Kaya, M.Y.; Yalcin, E.; Gozuacik, N.K.; Mensur, E. Effect of Texture on Ultra-high Strain Behavior in Eco-friendly NBT-0.25ST Ceramics using NBT Template. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2024, 107, 5502–5511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Jin, C.; Yao, Q.; Shi, W. Large Electrostrictive Effect in Ternary Bi0.5Na0.5TiO3-based Solid Solutions. J. Appl. Phys. 2013, 114, 027004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Lu, X.; Li, M.; Wang, Y.; Li, Z.; Lu, Z.; Lu, L. Thermal and Compositional Driven Relaxor Ferroelectric Behaviours of Lead-free Bi0.5Na0.5TiO3-SrTiO3 Ceramics. J. Mater. Chem. C Mater. 2020, 8, 2411–2418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiruma, Y.; Nagata, H.; Takenaka, T. Phase Diagrams and Electrical Properties of (Bi1/2Na1/2)TiO3-based Solid Solutions. J. Appl. Phys. 2008, 104, 124106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, W.; Chen, D.; Zheng, P.; Zhang, J.; Wen, F.; Shen, B.; Zhai, J.; Ji, Z. Phase transition, switching characteristics of MPB compositions and large strain in lead-free (Bi0.5Na0.5)TiO3-based piezoceramics. J. Alloys Compd. 2017, 709, 646–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, W.; Li, L.; Li, W.; Shen, B.; Zhai, J.; Chen, H. Phase Diagrams and Electromechanical Strains in Lead-Free BNT-Based Ternary Perovskite Compounds. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2014, 97, 3510–3518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, W.; Li, L.; Wang, W.; Shen, B.; Zhai, J. Phase Diagram and Electrostrictive Effect in BNT-based Ceramics. Solid. State Commun. 2015, 206, 22–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.S.; Jo, W.; Kang, J.K.; Ahn, C.W.; Kim, I.W.; Ahn, K.K.; Lee, J.S. Incipient piezoelectrics and electrostriction behavior in Sn-doped Bi1/2(Na0.82K0.18)1/2TiO3 lead-free ceramics. J. Appl. Phys. 2013, 113, 154102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, W.; Li, L.; Li, W.; Shen, B.; Zhai, J.; Chen, H. Effect of SrTiO3 template on electric properties of textured BNT-BKT ceramics prepared by templated grain growth process. J. Alloys Compd. 2014, 603, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, C.W.; Choi, G.; Kim, I.W.; Lee, J.S.; Wang, K.; Hwang, Y.; Jo, W. Forced electrostriction by constraining polarization switching enhances the electromechanical strain properties of incipient piezoceramics. NPG Asia Mater. 2017, 9, e346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Shi, J.; Liu, X. Strain performance and thickness-induced asymmetry in SrTiO3 doped BNT-based lead-free ferroelectrics from nonergodic to ergodic phase. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 2024, 193, 112188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, W.; Chen, D.; Zheng, P.; Zhang, J.; Shen, B.; Zhai, J.; Ji, Z. Grain-orientated lead-free BNT-based piezoceramics with giant electrostrictive effect. Ceram. Int. 2017, 43, 3339–3345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Jin, L.; Xu, Z.; Wang, D.; Zhang, S. Electrostrictive effect in Pb(Mg1/3Nb2/3)O3-xPbTiO3 crystals. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2013, 102, 152910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, C.H.; Kim, H.P.; Choi, B.Y.; Han, H.S.; Son, J.S.; Ahn, C.W.; Jo, W. Lead-free piezoceramics—Where to move on? J. Mater. 2016, 2, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, W.; Li, H.; Xi, J.; Zhang, J.; Shen, B.; Zhai, J. Effect of different templates and texture on structure evolution and strain behavior of <001>-textured lead-free piezoelectric BNT-based ceramics. J. Alloys Compd. 2016, 656, 13–23. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J.; Zhang, S.; Li, F. Prospect of Texture Engineered Ferroelectric Ceramics. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2022, 121, 120501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moriana, A.D.; Zhang, S. Lead-free Textured Piezoceramics using Tape Casting: A Review. J. Mater. 2018, 4, 277–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Li, Y. Topochemical Synthesis of Plate-like Na0.5Bi0.5TiO3 Templates from Bi4Ti3O12. Mater. Lett. 2010, 64, 1157–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Huang, R.; Lin, H.T.; Du, Z.; Dai, Y. Effect of the Template Particles Size on Structure and Piezoelectric Properties of <001>-textured BNT-Based Ceramics. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2024, 107, 3219–3229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Zhou, H.; Yan, Y.; Liu, D. Topochemical Synthesis of Plate-like Na0.5Bi0.5TiO3 from Aurivillius Precursor. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2008, 91, 1322–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, Y.; Takao, H. Synthesis of Plate-Like (Bi0.5Na0.5)TiO3 Particles by Using a Topochemical Microcrystal Conversion Method and Grain-Oriented Ceramics. J. Korean Phys. Soc. 2007, 51, 790–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanjaya Ranmohotti, K.G.; Josepha, E.; Choi, J.; Zhang, J.; Wiley, J.B. Topochemical Manipulation of Perovskites: Low-temperature Reaction Strategies for Directing Structure and Properties. Adv. Mater. 2011, 23, 442–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poterala, S.F.; Chang, Y.; Clark, T.; Meyer, R.J.; Messinge, G.L. Mechanistic Interpretation of the Aurivillius to Perovskite Topochemical Microcrystal Conversion Process. Chem. Mater. 2010, 22, 2061–2068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, J.T.; Kwok, K.W.; Tam, W.K.; Tian, H.Y.; Jiang, X.P.; Chan, H.L.W. Plate-like Na0.5Bi0.5TiO3 Template Synthesized by a Topochemical Method. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2006, 89, 3850–3853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C.; Zhou, K.; Zhou, X.; Li, Z.; Zhang, D. Synthesis and Characterization of Na0.5Bi0.5TiO3 Platelets with Preferred Orientation using Aurivillius Precursors. Ceram. Int. 2015, 41, 6858–6862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Huang, R.; Peng, C.; Dai, Y.; Xiong, S.; Cai, C.; Lin, H.T. Low Temperature Synthesis of Plate-like Na0.5Bi0.5TiO3 via Molten Salt Method. Ceram. Int. 2020, 46, 19752–19757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dursun, S.; Mensur-Alkoy, E.; Sabuncu, A.; Berksoy-Yavuz, A.; Gülgün, M.A.; Alkoy, S. Growth of NBT Template Particles through Topochemical Microcrystal Conversion and Their Structural Characterization. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2017, 100, 937–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, L.; Tang, C.; Chen, Y.; Yang, S.; Tang, M. The Thermal Physical Properties and Stability of the Eutectic Composition in a Na2CO3-NaCl Binary System. Thermochim. Acta 2014, 596, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andleeb, K.; Trung, D.T.; Fisher, J.G.; Tran, T.T.H.; Lee, J.S.; Choi, W.J.; Jo, W. Fabrication of Textured 0.685(Na0.5Bi0.5)TiO3-0.065BaTiO3-0.25SrTiO3 Electrostrictive Ceramics by Templated Grain Growth Using NaNbO3 Templates and Characterization of Their Electrical Properties. Crystals 2024, 14, 861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, W.; Hao, J.; Shen, B.; Fu, F.; Zhai, J. Processing optimization and piezoelectric properties of textured Ba(Zr,Ti)O3 ceramics. J. Alloys Compd. 2012, 536, 189–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, T.; Yi, Y.; Sakurai, F. Mechanisms of texture development in lead-free piezoelectric ceramics with perovskite structure made by the templated grain growth process. Materials 2010, 3, 4965–4978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kimura, T.; Yoshida, Y. Origin of Texture Development in Barium Bismuth Titanate Prepared by the Templated Grain Growth Method. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2006, 89, 869–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Liu, F.; Zhang, W.; Dou, Z.; Ma, W.; Samart, C.; Takesue, N.; Tan, H.; Fan, F.; Ye, Z.G.; et al. Design and development of outstanding strain properties in NBT-based lead-free piezoelectric multilayer actuators by grain-orientation engineering. Acta Mater. 2023, 246, 118696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, K.S.; Kang, S.J.L. Coarsening behavior of round-edged cubic grains in the Na1/2Bi1/2TiO3-BaTiO3 system. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2008, 91, 3191–3196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messing, G.L.; Trolier-McKinstry, S.; Sabolsky, E.M.; Duran, C.; Kwon, S.; Brahmaroutu, P.; Park, P.; Yilmaz, H.; Rehrig, P.W.; Eitel, K.B.; et al. Templated Grain Growth of Textured Piezoelectric Ceramics. Crit. Rev. Solid State Mater. Sci. 2004, 29, 45–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Liu, L.; Xie, H.; Zhang, Z.; Kou, Q.; Lv, R.; Yang, B.; Chang, Y.; Li, F. Enhanced Piezoelectric Properties and Depolarization Temperature in Textured (Bi0.5Na0.5)TiO3-based Ceramics via Homoepitaxial Templated Grain Growth. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2024, 176, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, J.G.; Kang, S.J.L. Strategies and Practices for Suppressing Abnormal Grain Growth during Liquid Phase Sintering. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2018, 102, 717–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.J.L.; Lee, M.G.; An, S.M. Microstructural Evolution during Sintering with Control of the Interface Structure. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2009, 92, 1464–1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, A.; Jing, R.; Zhuang, M.; Hou, H.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, J.; Lu, X.; Yan, Y.; Du, H.; Jin, L. Nonstoichiometric Effect of A-site Complex Ions on Structural, Dielectric, Ferroelectric, and Electrostrain Properties of Bismuth Sodium Titanate Ceramics. Ceram. Int. 2021, 47, 32747–32755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, P.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Ma, W.; Liu, K.; He, X.; Marwat, M.A.; Xie, B.; Li, M.; Zhang, H. Large strain under low driving field in lead-free relaxor/ferroelectric composite ceramics. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2019, 102, 4113–4126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Groh, C.; Zhang, Q.; Jo, W.; Webber, K.G.; Rödel, J. Large Strain in Relaxor/Ferroelectric Composite Lead-Free Piezoceramics. Adv. Electron. Mater. 2015, 1, 1500018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinterstein, M.; Knapp, M.; Hölzel, M.; Jo, W.; Cervellino, A.; Ehrenberg, H.; Fuess, H. Field-induced phase transition in Bi1/2Na1/2TiO3-based lead-free piezoelectric ceramics. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2010, 43, 1314–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.; Sun, X.; Li, Q.; Qian, H.; Liu, Y.; Lyu, Y. Enhanced electrostrictive coefficient and suppressive hysteresis in lead-free Ba(1−x)SrxTiO3 piezoelectric ceramics with high strain. Crystals 2021, 11, 555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viola, G.; Saunders, T.; Wei, X.; Chong, K.B.; Luo, H.; Reece, M.J.; Yan, H. Contribution of piezoelectric effect, electrostriction and ferroelectric/ferroelastic switching to strain-electric field response of dielectrics. J. Adv. Dielectr. 2013, 3, 1350007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, L.; Li, F.; Zhang, S. Decoding the fingerprint of ferroelectric loops: Comprehension of the material properties and structures. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2014, 97, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Fan, H.; Liu, X.; Li, Q. Ferroelectric Hysteresis Loop Scaling and Electric Field-induced Strain of Bi0.5Na0.5TiO3-BaTiO3 Ceramics. Phys. Status Solidi (A) Appl. Mater. Sci. 2014, 211, 2388–2393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thi, M.P.; March, G.; Colomban, P. Phase Diagram and Raman Imaging of Grain Growth Mechanisms in Highly Textured Pb(Mg1/3Nb2/3)O3–PbTiO3 Piezoelectric Ceramics. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2005, 25, 3335–3346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motohashi, T.; Kimura, T. Formation of Homotemplate Grains in Bi0.5Na0.5TiO3 Prepared by The Reactive-Templated Grain Growth Process. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2008, 91, 3889–3895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, P.G.; Tran, T.L.; Kim, H.P.; Jo, W.; Lee, J.S.; Fisher, J.G. Growth of Single Crystals of 0.75(Na0.5Bi0.5)TiO3-0.25(Sr0.7Ca0.3)TiO3 and Characterisation of Their Electrical Properties. Open Ceram. 2021, 6, 100099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Dong, J.; Zhang, L.; Yan, Y.; Jing, R.; Jin, L. Phase Evolution in (1−x)(Na0.5Bi0.5)TiO3-xSrTiO3 Solid Solutions: A Study Focusing on Dielectric and Ferroelectric Characteristics. J. Mater. 2020, 6, 677–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thawong, P.; Prasertpalichat, S.; Suriwong, T.; Pinitsoontorn, S.; Jantaratana, P.; Chootin, S.; Sriondee, M.; Charoonsuk, T.; Vittayakorn, N.; Rittidech, A.; et al. Optimal Bi0.8Ba0.2FeO3 Doping in Bi0.5(Na0.77K0.20Li0.03)0.5TiO3 Multiferroic Ceramics Synthesized by The Solid-State Combustion Technique. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 23340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeb, A.; Jan, S.U.; Bamiduro, F.; Hall, D.A.; Milne, S.J. Temperature-stable Dielectric Ceramics Based on Na0.5Bi0.5TiO3. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2018, 38, 1548–1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, A.; Jung, W.-G.; Moon, W.-J.; Uwiragiye, E.; Pham, T.L.; Lee, J.-S.; Fisher, J.G.; Ge, W.; Naqvi, F.U.H. Growth of (1−x)(Na1/2Bi1/2)TiO3–xKNbO3 Single Crystals by The Self-Flux Method and Their Characterisation. J. Korean Ceram. Soc. 2024, 61, 342–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.C.; Yang, C.F. Effects of NaNbO3 concentration on the relaxor and dielectric properties of the lead-free (Na0.5Bi0.5)TiO3 ceramics. CrystEngComm 2013, 15, 9097–9103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M’peko, J.-C.; Peixoto, A.G.; Jiménez, E.; Jiménez, J.; Gaggero-Sager, L.M. Electrical Properties of Nb-Doped PZT 65/35 Ceramics: Influence of Nb and Excess PbO. J. Electroceram. 2005, 15, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strukov, B.A.; Levanyuk, A.P. Ferroelectric Phenomena in Crystals; Physical Foundations Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, X.; Wu, D.; Zhang, F.; Niu, M.; Chen, B.; Zhao, X.; Liang, P.; Wei, L.; Chao, X.; Yang, Z. Enhanced Energy Density and Thermal Stability in Relaxor Ferroelectric Bi0.5Na0.5TiO3-Sr0.7Bi0.2TiO3 Ceramics. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2019, 39, 4778–4784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z.-Y.; Katiyar, R.S.; Yao, X.; Bhalla, A.S. Temperature Dependence of The Ferroelectrics. Phys. Rev. B 1998, 57, 8166–8177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundari, S.S.; Kumar, B.; Dhanasekaran, R. Structural, Dielectric, Piezoelectric and Ferroelectric Characterization of NBT-BT Lead-free Piezoelectric Ceramics. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2013, 43, 012010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suchanicz, J.; Roleder, K.; Kwapuliński, J.; Jankowska-Sumara, I. Dielectric and Structural Relaxation Phenomena in Na0.5Bi0.5TiO3 Single Crystal. Phase Transit. 1996, 57, 173–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvamani, R.; Singh, G.; Tiwari, V.S.; Gupta, P.K. Oxygen vacancy related relaxation and conduction behavior in (1−x)NBT-xBiCrO3 solid solution. Phys. Status Solidi (A) Appl. Mater. Sci. 2012, 209, 118–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suchanicz, J.; Kluczewska-Chmielarz, K.; Sitko, D.; Jagło, G. Electrical Transport in Lead-free Na0.5Bi0.5TiO3 Ceramics. J. Adv. Ceram. 2021, 10, 152–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Li, M.; Li, L.; Wu, P.; Pradal-Velázquez, E.; Sinclair, D.C. Defect chemistry and electrical properties of sodium bismuth titanate perovskite. J. Mater. Chem. A 2018, 6, 5243–5254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Li, L.; Zang, J.; Sinclair, D.C. Donor-doping and reduced leakage current in Nb-doped (Na0.5Bi0.5)TiO3. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2015, 106, 102904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, L. First-Principle Study of The Defect Chemistry and Conductivity in Sodium Bismuth Titanate; Technische Universität Darmstadt: Darmstadt, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Bersuker, I.B. Pseudo-Jahn-teller effect—A two-state paradigm in formation, deformation, and transformation of molecular systems and solids. Chem. Rev. 2013, 113, 1351–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nye, J.F. Physical Properties of Crystals: Their Representation by Tensors and Matrices; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, C.A.J.; Islam, M.S.; Moriwake, H. Atomic Level Investigations of Lithium Ion Battery Cathode Materials. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 2010, 79, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishimura, S.I.; Kobayashi, G.; Ohoyama, K.; Kanno, R.; Yashima, M.; Yamada, A. Experimental visualization of lithium diffusion in LiₓFePO4. Nat. Mater. 2008, 7, 707–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, W.; Liu, N.; Gao, K.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, S. Synthesis of Anisotropic Na0.5Bi0.5TiO3 Crystals Using Different Topochemical Microcrystal Conversion Methods. Int. J. Appl. Ceram. Technol. 2016, 13, 871–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotgering, F.K. Topotactical Reactions with Ferrimagnetic Oxides Having Hexagonal Crystal Structures-I. J. Inorg. Nucl. Chem. 1959, 9, 113–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, J.L.; Slamovich, E.B.; Bowman, K.J. Critical Evaluation of the Lotgering Degree of Orientation Texture Indicator. J. Mater. Res. 2004, 19, 3414–3422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Untextured | Textured | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crystal system | Tetragonal | Rhombohedral | Tetragonal | Rhombohedral |

| Space group | P4bm | R3c | P4bm | R3c |

| a (Å) | 5.5501 | 5.5205 | 5.5245 | 5.5160 |

| b (Å) | 5.5501 | 5.5205 | 5.5245 | 5.5160 |

| c (Å) | 3.9526 | 13.5624 | 3.9751 | 13.5183 |

| α (°) | 90 | 90 | 90 | 90 |

| β (°) | 90 | 90 | 90 | 90 |

| γ (°) | 90 | 120 | 90 | 120 |

| Weight fraction% | 46.1 | 53.9 | 17.9 | 82.1 |

| R (weighted profile)% | 9.5496 | 8.7159 | ||

| R profile% | 7.7909 | 5.4665 | ||

| Oxide (mol%) | Untextured | Textured | Nominal 0.90(Na0.5Bi0.5)TiO3-0.08KNbO3-0.02SrTiO3 | Templates | Nominal (Na0.5Bi0.5)TiO3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Na2O | 13.39 ± 0.64 | 13.89 ± 0.41 | 15.31 | 14.05 ± 0.51 | 16.67 |

| K2O | 2.33 ± 0.12 | 2.38 ± 0.10 | 2.72 | 1.83 ± 0.59 | 0 |

| TiO2 | 64.28 ± 0.33 | 64.12 ± 0.35 | 62.59 | 65.36 ± 1.13 | 66.67 |

| SrO | 1.15 ± 0.05 | 1.07 ± 0.07 | 1.36 | 0.68 ± 0.48 | 0 |

| Bi2O3 | 16.06 ± 0.25 | 15.79 ± 0.22 | 15.31 | 16.17 ± 0.51 | 16.67 |

| Nb2O5 | 2.80 ± 0.08 | 2.75 ± 0.14 | 2.72 | 1.91 ± 1.05 | 0 |

| Parameter | Untextured | Textured |

|---|---|---|

| Td (°C) | - | - |

| Tsm (°C) | 142 | 169 |

| Tm (°C) | 251 | 250 |

| Tθ (°C) | 278 | 308 |

| TB (°C) | 518 | 558 |

| Ea (eV) | 1.48 | 1.54 |

| Component | Composition wt% | Function |

|---|---|---|

| Matrix powder: 0.90NBT-0.08KN-0.02ST | 51.61 | |

| Organic Binder: Polyvinyl-Butyral PVB (Butvar B79, Eastman, Kingsport, TN, USA) | 4.65 | Binder |

| Polyethylene-Glycol PEG 400 (Daejung Chemicals, CP grade) | 0.33 | Plasticizer |

| n-Butyl Benzyl Phthalate BBP (Alfa Aesar, 98%) | 1.59 | Plasticizer |

| Methyl-ethyl ketone (Daejung Chemicals, >99.5%) | 27.60 | Solvent |

| Ethanol (Daejung Chemicals, 99.9%) | 14.22 | Solvent |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ayuningsih, A.; Ecebaş, N.; Tran, T.T.H.; Fisher, J.G.; Lee, J.-S.; Choi, W.-J.; Jo, W. Texturing (Na0.5Bi0.5)TiO3-KNbO3-SrTiO3 Electrostrictive Ceramics by Templated Grain Growth Using (Na0.5Bi0.5)TiO3 Platelets. Inorganics 2025, 13, 387. https://doi.org/10.3390/inorganics13120387

Ayuningsih A, Ecebaş N, Tran TTH, Fisher JG, Lee J-S, Choi W-J, Jo W. Texturing (Na0.5Bi0.5)TiO3-KNbO3-SrTiO3 Electrostrictive Ceramics by Templated Grain Growth Using (Na0.5Bi0.5)TiO3 Platelets. Inorganics. 2025; 13(12):387. https://doi.org/10.3390/inorganics13120387

Chicago/Turabian StyleAyuningsih, Arum, Nazım Ecebaş, Tran Thi Huyen Tran, John G. Fisher, Jong-Sook Lee, Woo-Jin Choi, and Wook Jo. 2025. "Texturing (Na0.5Bi0.5)TiO3-KNbO3-SrTiO3 Electrostrictive Ceramics by Templated Grain Growth Using (Na0.5Bi0.5)TiO3 Platelets" Inorganics 13, no. 12: 387. https://doi.org/10.3390/inorganics13120387

APA StyleAyuningsih, A., Ecebaş, N., Tran, T. T. H., Fisher, J. G., Lee, J.-S., Choi, W.-J., & Jo, W. (2025). Texturing (Na0.5Bi0.5)TiO3-KNbO3-SrTiO3 Electrostrictive Ceramics by Templated Grain Growth Using (Na0.5Bi0.5)TiO3 Platelets. Inorganics, 13(12), 387. https://doi.org/10.3390/inorganics13120387