1. Introduction

Data exchange is a key function of advanced optical networks. The integration of collaborative artificial intelligence into both industrial production and daily life has transformed traditional passive network transmission into a new, intelligent paradigm. This transformation significantly increases the demand for flexibility in data exchange. Developing multiple physical dimensions of light and utilizing spatial modes to simultaneously carry multiple optical signals can achieve the large-scale parallel processing of data transmission. In recent years, substantial efforts have been devoted to the development of multiplexing technologies, such as wavelength division multiplexing [

1], polarization division multiplexing [

2], and mode division multiplexing (MDM) [

3]. Among these, MDM can be combined with other multiplexing techniques [

4,

5], emerging as one of the most effective approaches for enhancing communication capacity. Over the past years, a variety of passive components have been widely studied and demonstrated for MDM, such as mode multiplexers/demultiplexers, mode converters, multimode bends, mode switches, and multimode cross-connects [

6,

7,

8,

9].

Mode switching is regarded as a key component for realizing large-scale reconfigurable MDM networks. However, most existing approaches based on multimode interferometers, Y-junctions, Mach–Zehnder interferometers, and asymmetric directional couplers [

10,

11,

12,

13] can only enable data exchange between two or three modes, which is clearly insufficient to support higher-order mode optical communication networks. Multimode switching architectures based on micro-ring or micro-disk resonators [

14,

15] can achieve data switching among multiple modes and extend the number of supported channels, but their structural complexity and limited integrability hinder large-scale deployment. Therefore, to realize flexible on-chip interconnects for MDM, a major challenge lies in developing a simple and reconfigurable mode switch. The three-waveguide coupled (TWC) switch between the E

00 mode and the E

10 mode has been successfully verified and demonstrated on silicon-on-insulator and lithium niobate platforms [

16,

17,

18] and arbitrary switching among the first three-order modes has been proposed [

19], which is essential for future large-scale MDM systems. The SOI platform exhibits low switching power consumption and fast switching speeds due to its high thermo-optical coefficient and thermal conductivity. However, its high thermo-optical coefficient also results in elevated temperature sensitivity for WDM devices on this platform, preventing the realization of high-performance monolithic integrated WDM-MDM systems. Thin-film lithium niobate exhibits fast electro-optic switching speeds but suffers from poor inherent electro-optic stability, necessitating additional thermo-optic modulation to ensure stable switching rates. Silica platforms are a mature platform with a low transmission loss (0.12 dB/cm) [

20], a low polarization-dependent loss (PDL), and a high coupling tolerance [

21]. By using a 2% index contrast silica platform, the bend radius can be reduced to 1500 μm. Meanwhile, the silica platform features highly mature WDM devices, enabling the rapid realization of monolithic WDM-MDM systems. Power consumption in silica-based devices can be optimized to be as low as 20 mW through refined designs of isolation trenches and electrode geometries [

22]. Our silica-based switch exhibits millisecond-level switching speeds (0.64–0.86 ms), which is sufficient for static reconfigurable MDM provisioning.

In this work, we design and experimentally demonstrate a TWC mode switch on a silica platform for E00 (E20)/E10 (E30) modes. We further propose a non-crossing cascaded TWC architecture and successfully validate it experimentally, extending the design to the high-order E00–E30 modes. From 1500 to 1630 nm, the insertion losses (ILs) of mode switching for E00/E10 and E20/E30 are lower than 8.07 dB and 14.52 dB, with −16.23 dB and −14.97 dB.

Meanwhile, the loss of the mode demultiplexer and coupling loss and the CT was lower than −22.84 (−18.28) dB. Furthermore, we optimize and expand the mode-selective switch for input E

00 and output E

00–E

30 in [

19], reducing the number of beam splitters and achieving a non-crossing structure, which is experimentally verified. This facilitates the implementation of higher-order mode-selective switches.

2. Optical Design and Principles

As shown in

Figure 1a, a reconfigurable and broadband adiabatic TWC mode switch was designed on a silica platform with a 2% index contrast. The operating wavelength was set to 1550 nm, corresponding to refractive index of 1.4737 for the core layer and 1.4448 for the cladding layer. The input combiner of the device adopts an adiabatic coupling design, whereas the combiner following the modulation arm adopts a TWC design. This three-waveguide coupling region (TWCR) consists of four TWC sections (TWCR

1–4), corresponding to mode selection among the E

00–E

30 modes. Each TWC structure contains single-mode waveguides on both sides and a single-mode waveguide together with a multimode waveguide in the center. The bus waveguide is formed by connecting four waveguides of different widths using linear taper transitions. The two input ports and the output port of the multimode bus waveguide are defined as I

1, I

2, and O, respectively.

The adiabatic coupler at the input is designed based on the principle of mode evolution [

19,

20], and its structural parameters are shown in

Figure 1c. The input waveguide widths,

and

, taper linearly from 5 μm to 4 μm, with a coupling length L

c of 10,000 μm, while the gap g

c decreases from 12 μm to 0 μm, and eventually connects to a multimode output waveguide with a width W

3 of 8 μm at the end of the adiabatic transition. The subsequent Y-junction and the modulation arm waveguide are both single-mode waveguides with a height and width of 4 μm. The thermo-optic modulation of the silica waveguide by the Ti electrode with Au pads is adopted to implement the demanded phase; the electrode is 21 μm wide and 3000 μm long. The cross-section of the device’s waveguide is shown in

Figure 1b.

The modulation arm (s) behind the Y-branch only supports the E00 mode transmission. When the E00 mode is input from the wide waveguide port I1, the light in the multimode output waveguide remains in the E00 mode, passing through the Y-branch then generating two E00 mode beams with identical phases and equal power. When input from the narrow waveguide port I2, the light converts to the E10 mode in the multimode waveguide, and subsequent transmission through the Y-branch produces two E00 mode beams with opposite phases (phase difference of π) and equal optical power. This is critical to the operating state of the subsequent TWC system.

Based on the supermode theory [

21,

22], the TWCR was designed as shown in

Figure 1d. A coupling structure consisting of two closely spaced single-mode waveguides can be regarded as an integrated system. When the input signal light enters from one of the waveguides, it will excite an even-symmetric mode SM

1 and an odd-symmetric mode SM

2 in this system, the initial phase of the two supermodes will be the same, the initial mode field integral will be the same as the mode field integral of the input light, and it can exist stably in the system due to the different propagation constants. When the mode field is superimposed, the signal light of the input waveguide (WG) will be all coupled into the adjacent waveguide, which needs to meet the two supermodes to transmit a distance along the

z-axis direction to make the phase difference π. These supermodes can be mathematically expressed as

where

(

) is the electric field distribution of the even (odd) symmetric supermode and

(

) is the corresponding propagation constant. Since the two supermodes possess different propagation constants, they can stably coexist. When the two supermodes propagate along the

-axis for a certain distance such that their phase difference reaches

, the initial modal field launched in one waveguide will be completely transferred to the adjacent waveguide, where the propagation distance satisfies,

We define this coupling distance as the beat length

. Based on

, (where k is the wave number in free space and

is the effective refractive index) we obtain

where

is the wavelength of the input light, and

and

are the effective refractive indices of the odd-symmetric and even-symmetric modes in the system, respectively.

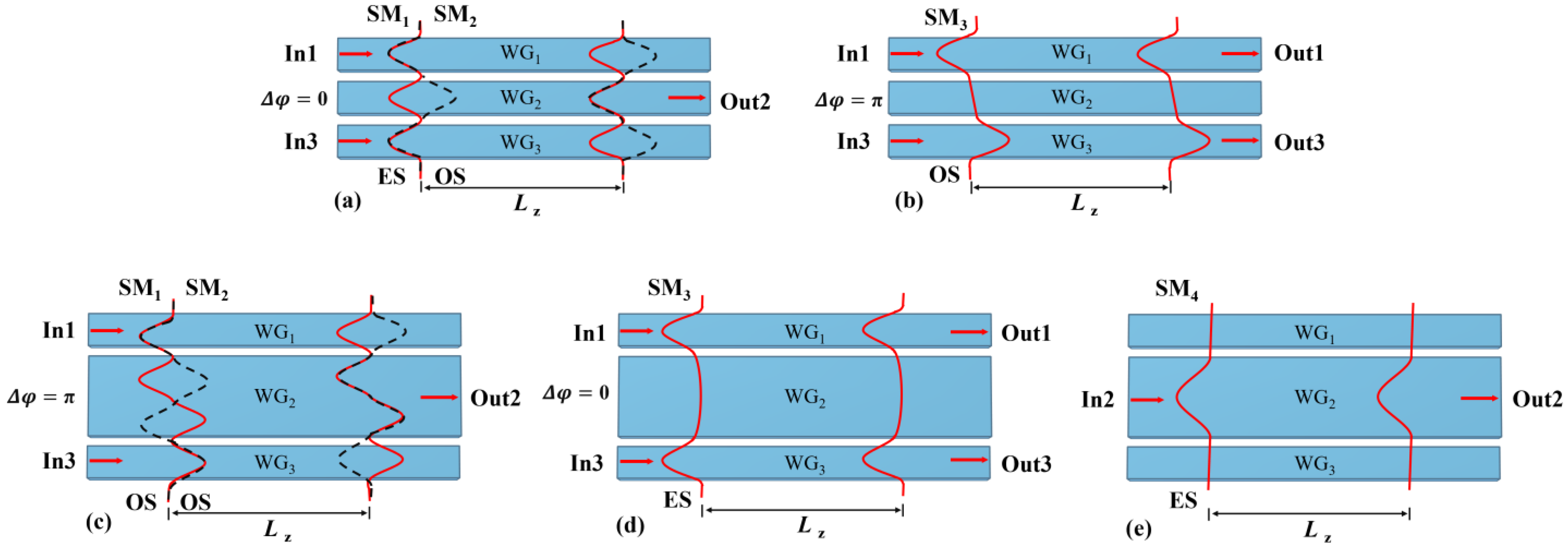

The supermode coupling composed of three single-mode waveguides is shown in

Figure 2a,b. Two beams of incident signal light, with a phase difference

and input from WG

1 and WG

3 at the same time, will excite an even-symmetric mode SM

1 and an odd-symmetric mode SM

2 and transmit a beat length

, and the signal light is all coupled from WG

1 and WG

3 into WG

2, as shown in

Figure 2a. When

, only an odd-symmetric mode SM

3 is excited in the system and transmits stably, without coupling, as shown in

Figure 2b.

The middle waveguide of TWCR is designed as a multimode waveguide supporting E

00 mode transmission. As shown in

Figure 2c–e, when two beams of signal light are incident from WG

1 and WG

3 with a phase difference

, two odd-symmetric modes SM

1 and SM

2 are excited. After transmitting a coupling distance

, the signal light couples into WG

2, propagating as the E

00 mode, as shown in

Figure 2c. When the phase difference

, only the even-symmetric mode SM

3 is excited, which stably propagates in the system without coupling, as shown in

Figure 2d. When the signal light is input from WG

2, only the even-symmetric mode SM

4 is excited, which stably propagates in the system without coupling, as shown in

Figure 2e.

As shown in

Figure 3, this is a TWC cascaded mode-selective system. When

n = 1 (

n = 2), this corresponds to the E

00/E

10 (E

20/E

30) mode-selective structure. When the phase difference between the two incident beams of signal light in TWCR

2n−1 is 0 or 2π, the signal light will couple into the bus waveguide as even-symmetric modes, with the excited supermode and transmission characteristics as shown in

Figure 2a. When the phase difference between the two incident beams of signal light in TWCR

2n is π, the signal light will couple into the bus waveguide as odd-symmetric modes, as shown in

Figure 2c. Here, the coupling conditions for TWCR

2n−1 and TWCR

2n are equally applicable to the four-cascaded TWC structure.

Then the signal light of E

00 mode enters from port I

1 and the optical phase difference between the two modulation arms is

. In TWCR

2n−1, the two beams of signal light couple into the bus waveguide as the E

00 mode, and the excited supermode and transmission characteristics are as shown in

Figure 2a; in TWCR

2n, the signal light stably propagates without coupling as shown in

Figure 2e, and the E

00 mode is output finally. When the E

00 mode enters from port I

2, the optical phase difference between the two modulation arms is

. In TWCR

2n−1, the beams stably propagate without coupling as shown in

Figure 2b; in TWCR

2n, the signal light couples into the bus waveguide and excites the E

10 mode as shown in

Figure 2c, and the E

10 mode is output finally.

In summary, without modulation, this work can realize a two-mode-selective output by means of different input ports.

Figure 3b illustrates the operating mode of the structure with modulation. By applying a voltage to the electrode heater above the modulation arm waveguide, a modulation-induced phase difference

is introduced into the light propagating through these modulation arm waveguides. When the E

00 mode is launched through port I

1, the light in the upper modulation arm waveguide undergoes phase compensation—specifically, this varies the initial optical phase difference (

) between the two modulation arms to

. Consequently, the E

00 mode does not couple into the bus waveguide at TWCR

2n−1 and continues propagating to TWCR

2n, where it couples into the multimode bus waveguide and outputs as an odd-order mode. Similarly, when the E

00 mode is launched through port I

2, the optical phase difference between the two modulation arms is adjusted from the initial

to

. The two beams then couple at TWCR

2n−1 and enter the multimode bus waveguide as an even-order mode. This design enables mode-selective output through thermo-optic modulation, thereby eliminating the need for input port switching.

Based on the above working principle, the BPM was used to simulate and optimize the mode selectors for the E

00/E

10 and E

20/E

30 modes.

Figure 4a–d present the simulated optical field distributions of the E

00/E

10 mode-selective switch at 1550 nm with different operating conditions, whereas

Figure 4e–h show those of the E

20/E

30 mode-selective switch at 1550 nm with various operating conditions.

For the E

00/E

10 mode-selective switch, the following observations were made: With the E

00 mode input from port I

1, the output is E

00 at

(no modulation,

Figure 4a) and E

10 when the heating electrode is activated (

,

Figure 4b). From port I

2, the output switches to E

10 at

(

Figure 4c) and reverts to E

00 at

(

Figure 4d). For the E

20/E

30 mode-selective switch, the following observations were made: E

00 input from port I

1 yields E

20 at

(

Figure 4e) and E

30 at

(heating electrode on,

Figure 4f). From port I

2, E

30 is output at

(

Figure 4g) and E

20 at

(

Figure 4h).

The simulation results are highly consistent with the theoretical analysis, confirming the excellent scalability and flexibility of the TWCR cascade structure when it is mode-selective.

To achieve conversion from the fundamental mode to higher-order modes, the effective refractive index of the high-order mode supported by the multimode bus waveguide must match that of the E

00 mode in the single-mode waveguides on both sides of the system. Using the effective refractive index matching method [

19] and taking the effective refractive index of the fundamental mode in a 4 μm wide silica waveguide as a reference, the widths of the multimode waveguides corresponding to the E

10, E

20, and E

30 modes were determined. Specific structural parameters including the widths (W

4–7) and coupling lengths (L

1–4) of the relevant waveguides and coupling segments are summarized in

Table 1.

We simulated the spectra with different fabricated errors for the E

00/E

10 mode-selective switch in

Figure 5. When the waveguide width shifts −0.2 μm, the loss in E

00 mode increases to 0.5 dB and the loss in E

10 mode increases to 1.2 dB. When the waveguide width shifts 0.2 μm, the loss in E

20 mode is lower than 1 dB. When the waveguide width shifts 0.1 μm, the loss in E

30 mode is lower than 1 dB.

3. Device Fabrication and Characterization

The device was fabricated on a six-inch silicon-dioxide wafer. First, a 20 μm thick silica lower cladding layer was grown on the silicon substrate via thermal oxidation. A 4 μm thick silicon dioxide core layer was then deposited onto the lower cladding layer using plasma-enhanced chemical vapor deposition (PECVD). Subsequently, the waveguide structure of the mode-selective switch was defined using inductively coupled plasma etching. A 20 μm thick silica upper cladding layer was deposited using PECVD. Finally, the electrodes were fabricated via magnetron sputtering and lift-off techniques. The footprint of the E

00/E

10 mode-selective switch is approximately 1 × 30 mm

2, that of the E

20/E

30 mode-selective switch is approximately 1 × 33 mm

2, and that of the E

00–E

30 mode-selective switch is 1 × 60 mm

2. The fabricated four-stage cascaded adiabatic gradual broadband three-waveguide coupled mode-selective switch is shown in

Figure 6a, which presents the photograph of the device after electrical packaging.

Figure 6b–e show the optical microscope images of the waveguide structure.

Figure 6f shows the SEM image of the waveguide cross-section.

To characterize the response time of the switch, a signal generator (SDG6032X-E, Siglent, Shenzhen, China) equipped with two probes is used as the driver. As illustrated in

Figure 7a, the output optical signal is monitored using a high-speed photodetector connected to an oscilloscope (DS4024, RIGOL, Suzhou, China). The test system requires single-mode transmission. The device output end is designed with an asymmetric directional coupler structure for the E

00–E

30 mode multiplexer/demultiplexer, which demultiplexes higher-order modes in a multimode bus into the fundamental mode. As shown in

Figure 1e, this corresponds to the output ports labeled sequentially as O

j for the E

00–E

30 modes (j = 1, 2, 3, 4). The mode demultiplexer design process and performance characterization have been introduced in our previous work [

23]. The rise time (10–90%) of the switch is measured to be 0.86 ms, and the fall time (90–10%) is 0.64 ms. Both the E

00/E

10 and E

20/E

30 mode-selective switches are tested; since they share the same platform materials, their response speeds are essentially identical. Additionally, the current–voltage (I–V) and optical power–voltage (O–V) characteristic curves of the switch are measured, shown in

Figure 7b, yielding a resistance of 90.42 Ω. When a voltage of 4.8 V is applied to the upper modulation arm, the output mode is switched—this voltage corresponds to a power consumption of 266.22 mW to achieve a phase difference of

.

A tunable laser (TSL-550, Santec, Komaki-City, Japan) is used as the light source. The TE-polarized fundamental mode is input into the device via end-face coupling, and the output light is then transmitted to an optical power meter (MPM200, Santec, Komaki-City, Japan) by using a single-mode fiber array (FA) for optical power detection.

The transmission spectra of mode MUX/DEMUX is shown in

Figure 8. The performance of the device has undergone a red shift, resulting in poor CT between the E

20 and E

30 modes. The reference waveguide loss is lower than 7.1 dB at 1550 nm. Due to waveguide scattering loss scales with (Δn)

3 [

24], the lower refractive index, and wide waveguide, the high-order modes can also show low transmission losses. We can calculate that at 1550 nm, the demultiplexer imposes an excess loss (EL) of 0.27 dB for the E

00 mode, 0.78 dB for the E

10 mode, 2.08 dB for the E

20 mode, and 4.09 dB for the E

30 mode. While this effectively reduces device size, the increased doping increases the flowability of the core material, leading to the melting of the core layer and the formation of undesirable waveguide shapes [

25]. Furthermore, the emergence of an interdiffusion layer results in a broadening of the actual core layer range. As shown in

Figure 6f, the core layer is 4.1 × 4.1 μm

2 without an interdiffusion layer (4.6 × 4.5 μm

2 with an interdiffusion layer). Through process optimization and an integrated layout design, the device’s center wavelength can be aligned to 1550 nm.

The transmission spectrum of the E

00/E

10 mode-selective switch is shown in

Figure 9a and

Figure 10b. At 1550 nm, in the non-modulation state, IL is lower than 7.36 dB and CT is lower than −11.07 dB; in the electrode modulation state, the IL is lower than 7.86 dB and the CT is lower than −22.84 dB. The transmission spectrum of the E

00/E

10 mode-selective switch is shown in

Figure 9c and

Figure 10d. At 1550 nm, in the non-modulation state, IL is lower than 10.91 dB and CT is lower than −9.62 dB; in the electrode modulation state, the IL is lower than 10.75 dB and the CT is lower than −10.28 dB. With modulation, the EL of the E

20/E

30 mode-selective switch is 1.11–3.47 dB. In the unmodulated state, the device exhibits a relatively high additional loss and poor CT. This is attributed to minor variations in the width of the modulation arm waveguide during fabrication, which introduce additional phase shifts. Consequently, the TWC position deviates from the ideal π phase difference, leading to performance degradation. Widening the modulation arm can mitigate process-induced effects and enhance device performance.

4. E00–E30 Mode-Selective Switch

The two-mode-selective switches are regarded as a basic component for advanced functions. To demonstrate their scalability and flexibility, two components are cascaded on a bus waveguide, with three electrodes added to control the phase difference between the two light beams. As shown in the structural schematic of

Figure 1a, this configuration allows the selective output of any mode from E

00 to E

30. A mode demultiplexer is connected to the output end. The device has two input ports (I

1, I

2) and four output ports (O

1–O

4).

The phase shifts generated by the three electrodes S

1–3 is defined as

,

, and

. By modulating these three groups of phase shifts in different combinations, the output of any mode of E

00~E

30 can be realized. Taking the input E

00 mode output E

20 mode as an example, when the modulation conditions are set to

,

, and

, the signal light will be coupled to the E

20 mode at TWCR

3 and enter the bus waveguide. The correspondence between the remaining different input ports (I

1/I

2), different phase shift combinations, and output modes can be referred to the electrode voltage parameters summarized in

Table 2.

To contextualize the previously reported IL and CT values derived from transmission spectra, at 1550 nm, the loss of a reference straight waveguide was tested and plotted as a dashed line in the figures.

Figure 10a–d show the device’s transmission spectra, where when the E

00 mode is input from port I

1, the IL and CT values are 6.92 dB and −23 dB for E

00 output, 7.96 dB and −16.79 dB for E

10 output, 10.83 dB and −12.8 dB for E

20 output, and 15.56 dB and −14.8 dB for E

30 output.

Figure 10e–h present the transmission spectra for the E

00 mode input from port I

2, corresponding to IL and CT values of 7.00 dB and −23.03 dB for E

00 output, 6.62 dB and −14.96 dB for E

10 output, 9.36 dB and −10.57 dB for E

20 output, and 14.69 dB, and −15.91 dB for E

30 output. With modulation, the EL of the E

00–E

30 mode-selective switch is 1.28–6.12 dB.

The measurement results experimentally demonstrate that both the designed unit structure and the cascaded architecture can effectively achieve mode-selective output. This finding highlights the scalability and flexibility of the proposed approach, as well as its potential for enabling more advanced functionalities in related systems.

The mode demultiplexer is the main factor affecting the high-order mode IL in device test data, as shown in

Figure 8. Through process optimization and integrated layout design, the device’s center wavelength can be aligned to 1550 nm. By employing a fully automatic phase error calibration technique, this method dynamically compensates for phase errors. This significantly improves the precision and efficiency of the calibration process amid process-induced variations [

26]. The loss of the mode demultiplexer also can be reduced by using a conical ADC structure [

27,

28]. The power consumption can be further reduced through the structure of air isolation slots [

29]. The response speed can be reduced by reducing the thickness of the top cladding layer. The mode switch designed in this paper has the advantages of low transmission loss and a high mode extinction ratio, hence it has broad application prospects in MDM systems.