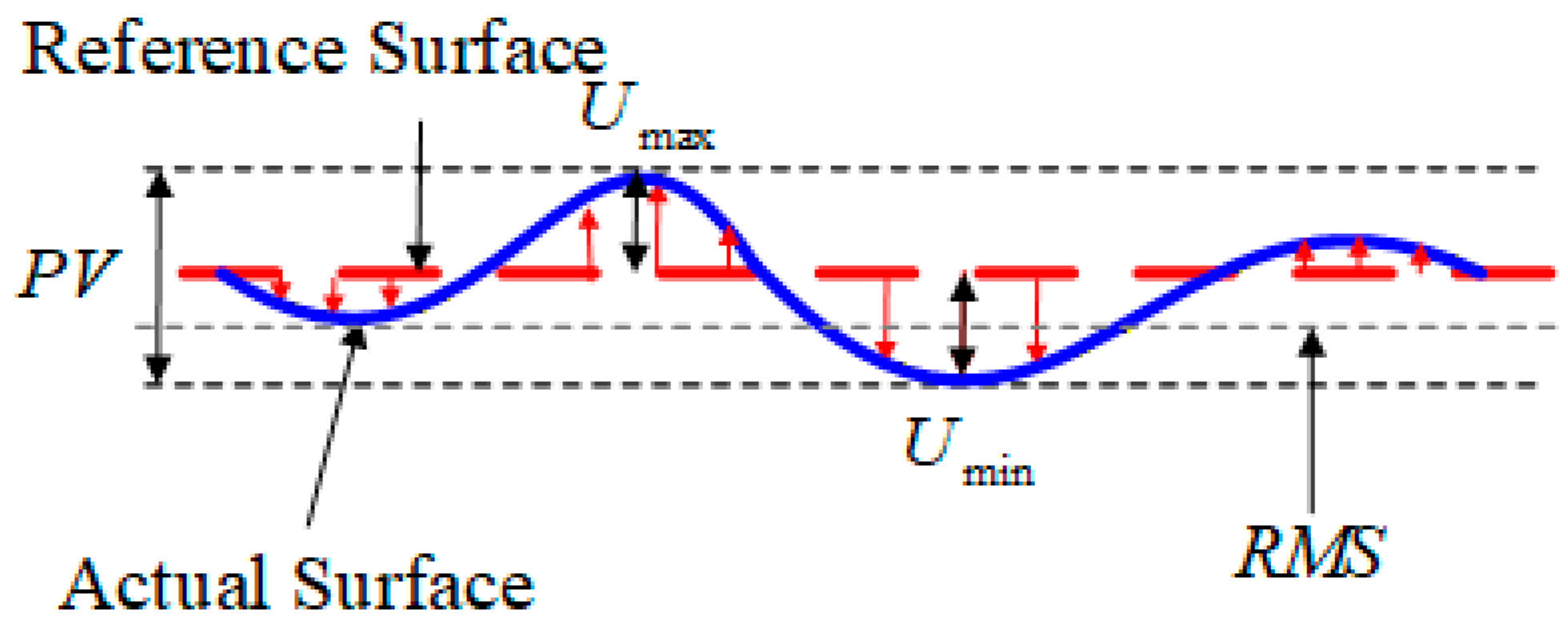

Surface figure fitting reconstructs a continuous surface from discrete finite element analysis (FEA) data. While Shi Yincheng et al. established a link between FEA and Zernike polynomials for static mirrors [

20], their method did not account for coordinate grid changes or rigid-body displacement. For high-dynamic scanning mirrors, factors such as mechanical and environmental loads can cause simultaneous optical surface deformation and rigid body displacement. Hence, rigid-body displacement must be subtracted prior to surface fitting.

4.1. Computation of Rigid Body Displacement

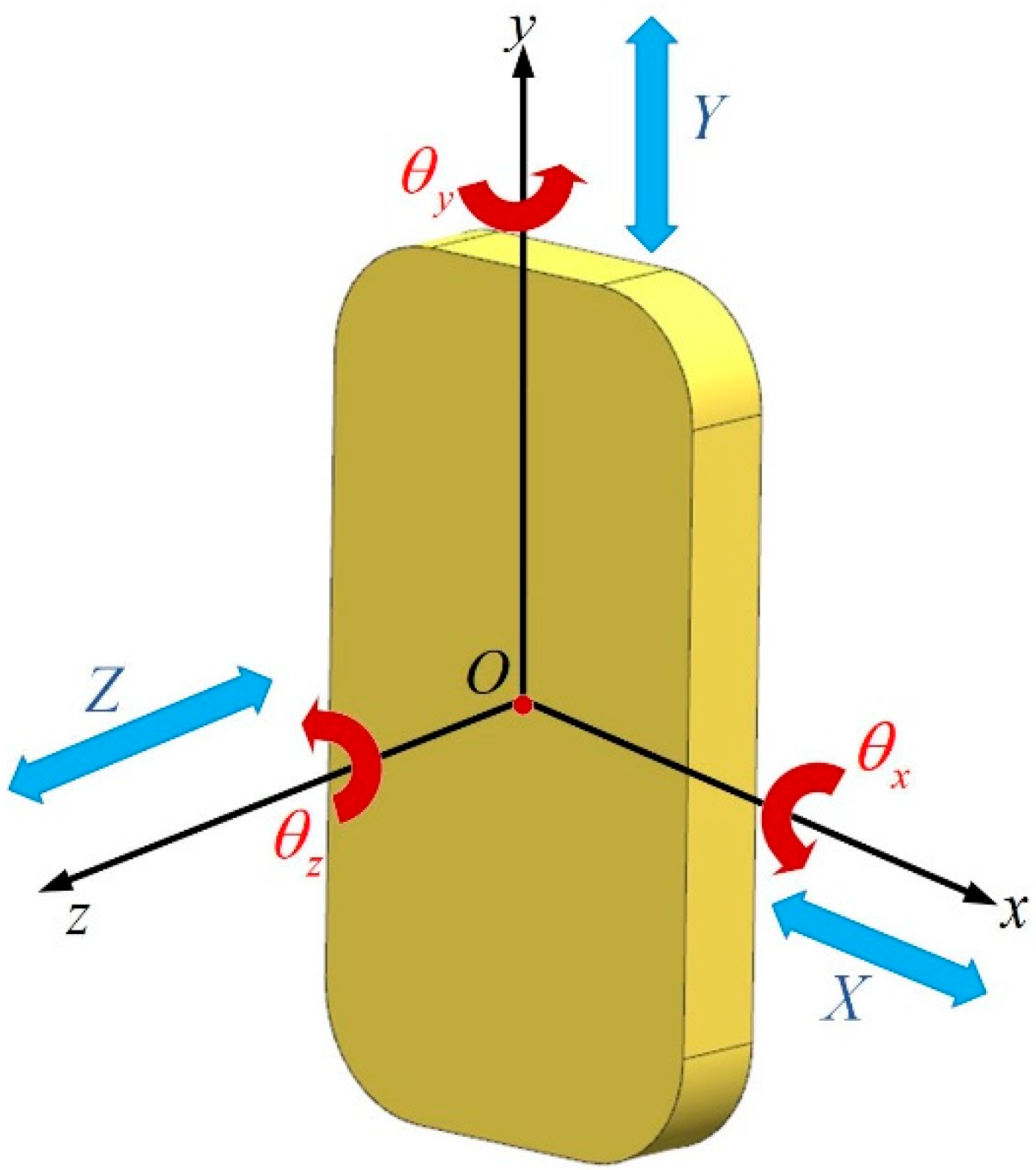

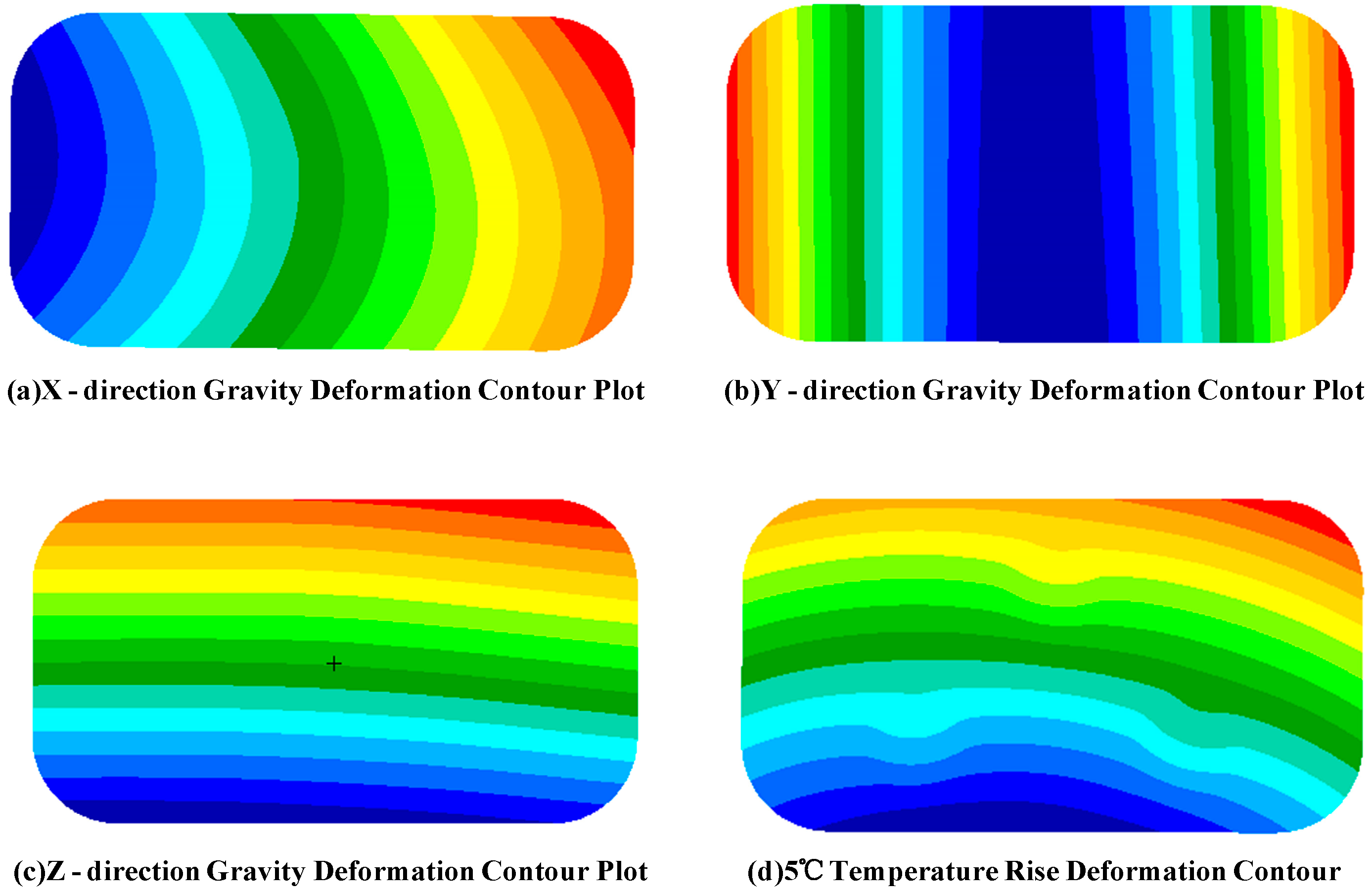

As shown in

Figure 4, the rigid body displacement manifests as: translation along the optical axis, decentration perpendicular to the optical axis, and tilt resulting from rotation.

A coordinate transformation matrix is first established, followed by the application of the least squares method to calculate the rigid body displacement. For optical surfaces with non-uniform coordinate grid distributions, the rigid body motion can be computed using an area-weighted average motion. The deformed coordinates

of a surface point

on the optical element can be expressed as:

Here, denotes the coordinate transformation matrix accounting for both rotation and translation. A fitting error is defined as the weighted sum of squares of the residuals in the , , and directions. The rigid-body displacement is estimated via the least squares method, yielding the displacement transformation matrix . This matrix is then used to extract the surface distortion data of the scanning mirror, which subsequently serves as the input for surface fitting.

4.2. Zernike Polynomial Surface Reconstruction Based on Finite Element Analysis

Zernike polynomials are widely used in optics, image processing, and surface figure fitting. From an engineering perspective, to accurately capture the critical higher-order aberrations inherent in rectangular scanning mirrors, this study adopts the Fringe indexing scheme [

21]. Specifically, the first 37 terms of the Zernike polynomials under this indexing convention are utilized for surface fitting.

The basic functions of traditional Zernike polynomials are orthogonal by construction within a unit circle. Nevertheless, this property does not hold for our rectangular scanning mirror, compromising fitting accuracy. To address this, a common technique for non-circular wavefronts is to regenerate an orthogonal basis from the Zernike polynomials via the Gram–Schmidt process [

22,

23,

24]. Given that our surface reconstruction is fundamentally a matrix transformation—akin to wavefront fitting—we adopt this same approach.

First, the grid coordinates

of the rectangular scanning mirror are normalized to ensure numerical stability and unit consistency for the subsequent orthonormalization process. Let the center coordinates of the sample points be

. For a rectangular aperture with length 2a and width 2b, the radius of its circumscribed circle R is defined as:

The original coordinates are then mapped onto the unit disk. The normalized coordinates

are calculated as follows:

Second, the Gram–Schmidt orthogonalization method is applied to construct a new set of orthogonal basis functions for the non-circular domain. Here, using the non-circular domain transformation matrix

, a linear transformation relationship is established between the circular-domain Zernike polynomials

and the rectangular-domain Zernike polynomials

:

Here, and represent the -th Zernike polynomial matrix in the non-circular domain and circular domain, respectively. With set to 37, each non-circular domain has a one-to-one correspondence with the transformation matrix .

Let the reflective surface area of the scanning mirror be denoted as

. Combining the inner product

between the matrices and leveraging the orthogonality of

and

the following expression is derived:

Based on Equations (15) and (16), the following transformation can be derived:

Expressed in the complete Zernike matrix form as:

Substituting Equation (18) into Equation (19):

Therefore, the equation of the transformation matrix

can be expressed as the inner product of the Zernike polynomial matrix in the circular field

This process enables the conversion of Zernike polynomials from a circular domain to a non-circular domain while preserving their orthogonality.

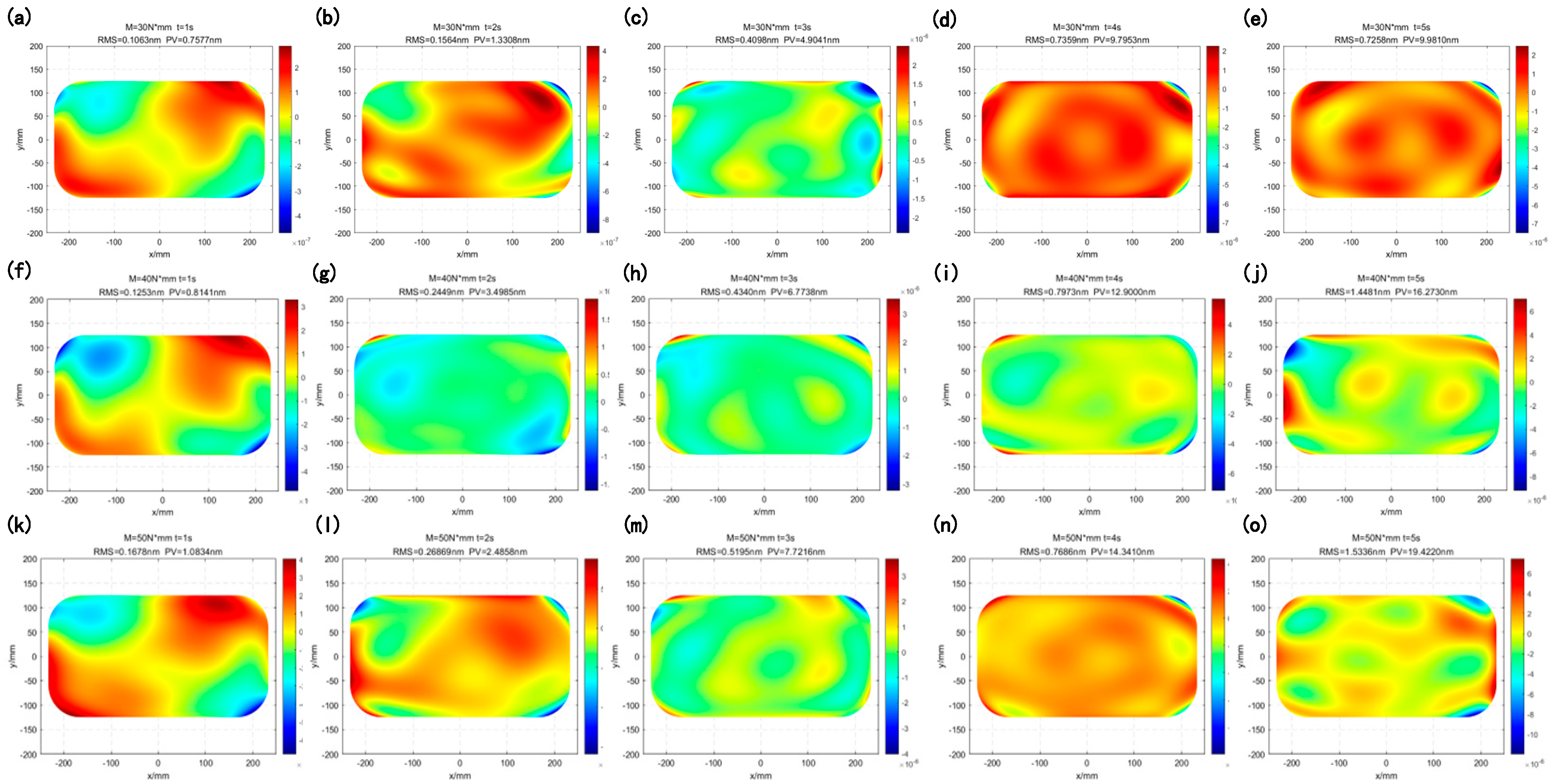

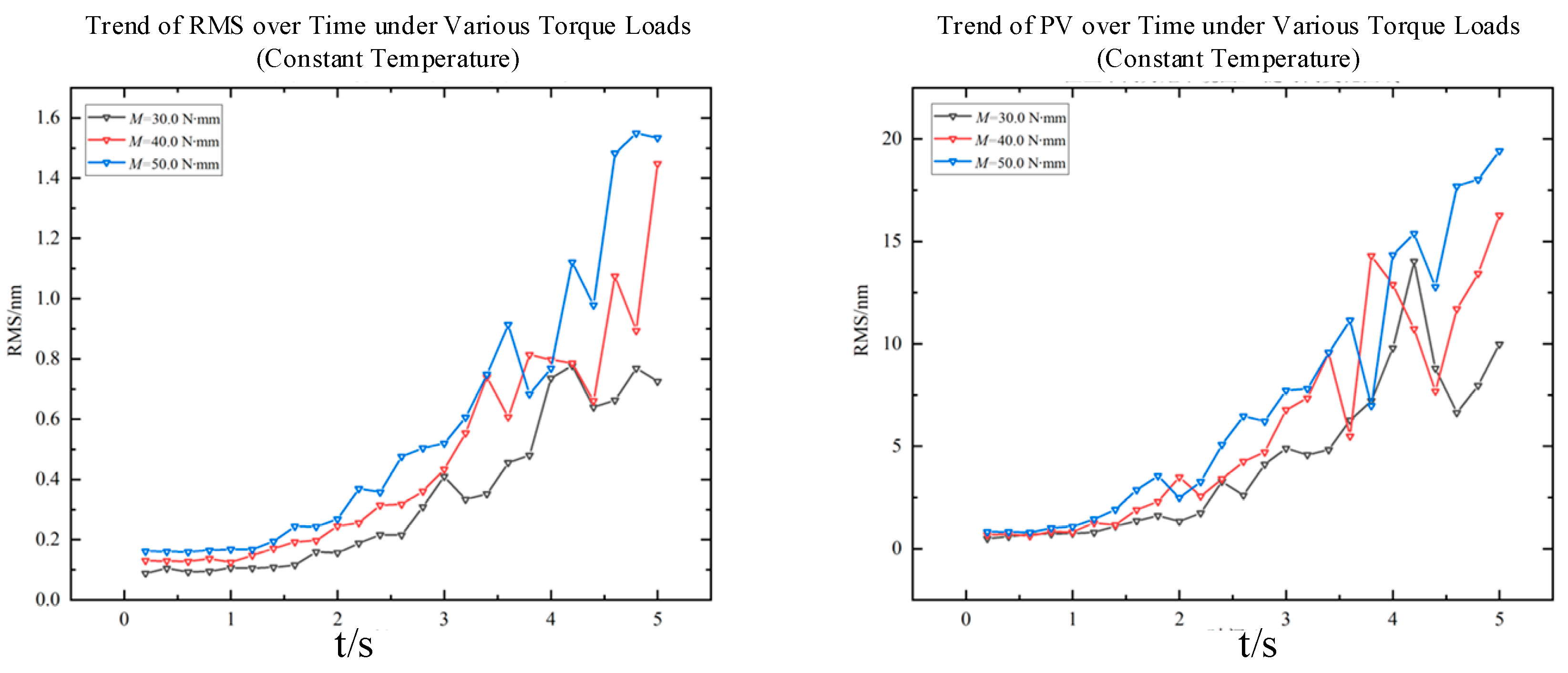

Subsequently, the fitted coefficient matrix is utilized to form a linear combination of the non-circular domain Zernike polynomial basis functions for surface reconstruction:

Based on the distribution of non-uniform discrete nodes in the finite element model, the area represented by each node is calculated. The coefficient matrix is then determined using the weighted least squares method. By substituting into the original coordinate system and performing the operation in Equation (22), the fitted and reconstructed surface form is obtained. Finally, the RMS and PV values of the surface deformation are computed by subtracting the deformed surface height data from the initial surface data. This calculation quantifies the deformation induced by gravity, motion, and other factors, thereby enabling the subsequent evaluation of imaging quality.