1. Introduction

Metamaterials are artificially engineered composite materials. Unlike conventional materials that are typically composed of a single substance, metamaterials consist of periodically arranged subwavelength structural units with various geometries, enabling precisely tunable electromagnetic or optical properties [

1,

2]. As artificial materials featuring subwavelength-scale characteristics, metamaterials exhibit remarkable potential in micro–nanophotonic devices [

3,

4]. Metamaterial-based micro- and nanostructures can give rise to a variety of unique physical phenomena and functionalities, such as negative refraction [

5], electromagnetic cloaking [

6], perfect lensing [

7], and the generation of vortex beams [

8], making them highly valuable for both fundamental research and practical applications.

With the growing demand for highly sensitive, real-time, and label-free detection technologies in fields such as biomedical diagnostics [

9,

10], food safety monitoring [

11,

12], and environmental surveillance [

13,

14], research on advanced sensing technologies has received increasing attention. Compared with terahertz-band sensing, microwave sensing exhibits significant advantages due to its superior electromagnetic penetration capability in water-containing media. For instance, terahertz waves suffer from high water absorption where the absorption coefficient exceeds 100 cm

−1 at 1 THz, limiting their penetration depth to the sub-millimeter range [

15]. In contrast, microwaves can penetrate several centimeters into aqueous environments. The performance of optical sensing methods, including those in the visible band, is fundamentally constrained by Rayleigh and Mie scattering effects in adverse atmospheric conditions, leading to severe signal degradation in the presence of smoke, fog, or dust. Research indicates that in dense fog conditions, optical signal attenuation can exceed 300 dB/km, whereas microwave attenuation in the same environment remains negligible at less than 0.5 dB/km [

16]. Consequently, microwave sensing, with its longer wavelength, experiences significantly less scattering and attenuation, thereby offering stronger penetration capability and greater environmental robustness. This allows it to function reliably regardless of natural lighting or challenging weather. Furthermore, owing to its high sensitivity to subtle variations in dielectric permittivity, together with advantages such as low system cost and ease of integration, microwave sensing has gradually become one of the key technological approaches for liquid analysis, chemical concentration monitoring, and biomolecular recognition. For example, Kuznetsova et al. designed a microwave sensor using commercial electromagnetic simulation software to measure protein concentrations in mixed solutions, achieving a sensitivity of 0.075 MHz/(mg/mL) within the tested range [

17]. In addition, Mahfazur Rahman and colleagues proposed a metamaterial (MTM)-based microwave biosensing approach for detecting dilution-level variations in blood samples and developed a predictive model based on the measured data. Their sensor exhibits a pronounced frequency response within the investigated band, featuring a high Q-factor of 819 and an FOM value of 187.55 [

18]. In the field of liquid analysis, Song et al. developed a high-sensitivity microwave sensor for determining ethanol concentration by modifying the split-ring resonator (SRR) structure, achieving a measurement range of 20–80% with sensitivities of 0.75 MHz/% and 0.03 dB/% [

19]. For non-invasive glucose monitoring, Kiani and Rezaei employed an improved open-ring resonator to probe dielectric property variations in human fingertip tissue, enabling non-invasive glucose concentration measurement. Their sensor demonstrated strong agreement between simulations and volunteer experiments, exhibiting high sensitivity and a relatively large Q-factor [

20]. However, conventional microwave resonators are typically constrained by both radiation loss and material loss, resulting in broad resonance linewidths and limited Q-factors. These limitations restrict their detection sensitivity and represent a major bottleneck in advancing high-performance microwave sensing technologies.

To further enhance the sensor’s ability to detect subtle dielectric variations, high–quality factor (Q-factor) resonant structures play a critical role in metasurface-based sensing. In 1929, von Neumann and Wigner first introduced the concept of bound states in the continuum (BIC) [

21]. Theoretically, BICs exist in infinitely extended structures and remain completely decoupled from the external radiation field, thereby enabling an infinite Q-factor [

22]. However, ideal BICs are difficult to realize in practical implementations. Most engineering-applicable BICs are achieved by introducing appropriate perturbations into finite structures, transforming an originally perfectly confined mode into a leakage mode with an extremely high Q-factor, commonly referred to as a quasi-BIC (qBIC) or supercavity mode [

23].

Metasurfaces based on the BIC mechanism have attracted considerable attention due to their ability to suppress radiative losses, generate ultra-narrow spectral linewidths, and significantly enhance the resonance Q-factor. A wide range of BIC metasurface designs has been reported in recent years. Early studies mainly focused on metallic structures. For example, in 2021, Wang et al. proposed a metasurface composed of three gold nanorods within a single unit cell, achieving a high-Q resonance [

24]. In 2024, Song et al. further optimized metal-based BIC performance by depositing metallic patterns on a polyimide (PI) substrate and designing a dual split-ring resonator structure [

25]. However, the inherent absorption loss of metals limits their ability to achieve extremely high Q-factors. As a result, research interest has gradually shifted toward all-dielectric and metal–dielectric hybrid metasurfaces. In the area of all-dielectric BIC metasurfaces, Liu et al. from Zhejiang University designed a structure composed of paired rectangular pillars, achieving high-Q resonant modes [

26]. Zhang et al. from Shenzhen University demonstrated a silicon-based honeycomb metasurface with near-perfect absorption characteristics [

27]. Lin et al. from Fuzhou University utilized longitudinal symmetry breaking in a pure silicon metasurface to excite multiple tunable high-Q resonances [

28]. For hybrid structures, Liu et al. from Fudan University reported in 2024 that fabricating Si

3N

4 cylindrical tetramers on a gold film effectively enhances light–matter interactions [

29]. Additionally, in 2023, a graphene–dielectric hybrid metamaterial was proposed, capable of supporting high-Q quasi-BIC resonances while enabling dynamic tunability through graphene [

30]. Extensive research on BICs and quasi-BICs has been conducted across various material platforms and spectral regimes, with particularly abundant progress achieved in the terahertz domain. However, compared with optical and terahertz implementations, BIC-based sensing in the microwave regime remains relatively limited. Most existing microwave sensors still rely on split-ring resonators, defect-mode resonators, or other conventional electromagnetic structures, which inherently suffer from low Q-factors [

31,

32,

33,

34]. Most existing microwave sensors still rely on split-ring resonators, defect-mode resonators, or other conventional electromagnetic structures, which inherently have lower Q-factors due to intrinsic radiation and material losses. These limitations lead to broad resonance linewidths, hindering the detection of small dielectric variations, especially in complex and dynamic environments. Additionally, some microwave sensor structures are complicated and require cumbersome fabrication processes. Therefore, developing a microwave metasurface sensor that simultaneously possesses a high Q-factor, strong field enhancement, and a simple structural design is of significant scientific and practical value.

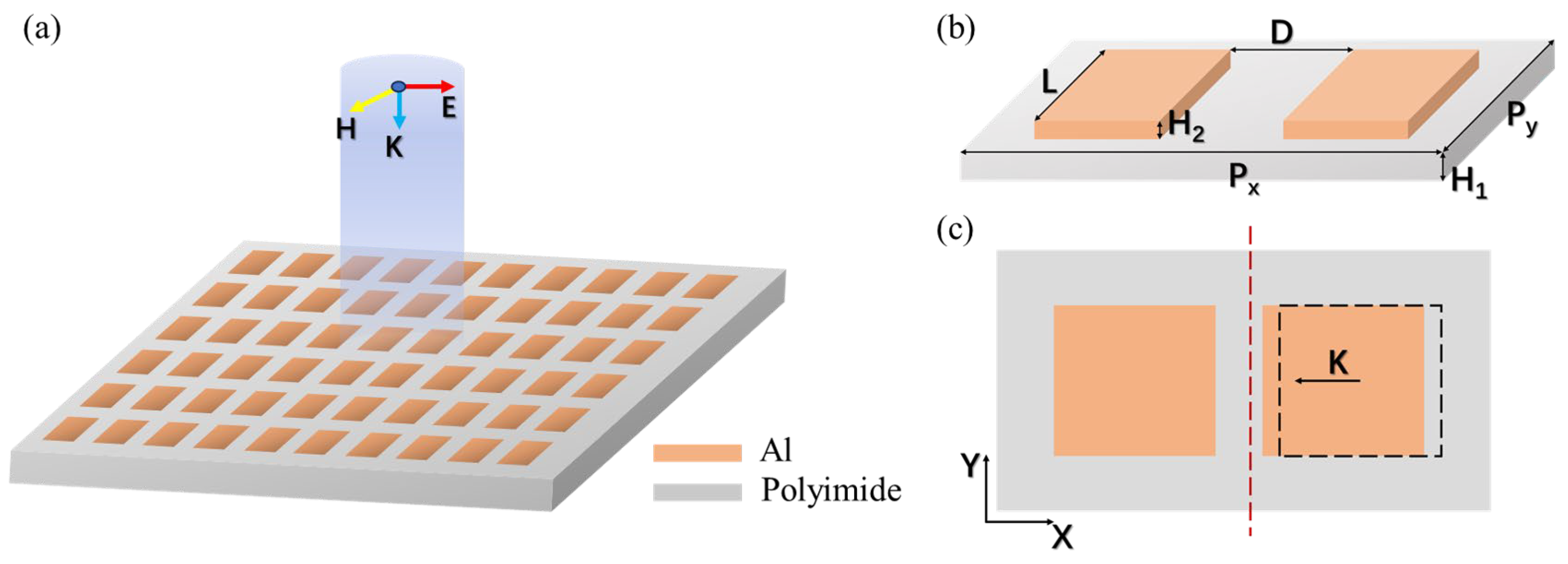

Therefore, this study proposes a high-Q microwave metasurface sensor enabled by the bound states in the continuum (BIC) mechanism. By introducing a tunable perturbation parameter into the dielectric metasurface structure, a continuum quasi-BIC (qBIC) mode with strongly suppressed radiation leakage is successfully excited, resulting in an ultra-narrowband microwave resonance with a significantly enhanced Q-factor. Numerical simulations demonstrate that the proposed sensor exhibits extremely high sensitivity to subtle variations in the surrounding dielectric environment, enabling applications such as chemical solution concentration monitoring and trace substance detection. These results further validate the feasibility and superiority of continuum-domain BICs for microwave sensing, providing a new design paradigm for high-performance, low-loss, and customizable microwave biosensors, and establishing a foundation for future development of ultra–high-Q microwave sensing platforms.

3. Results and Discussion

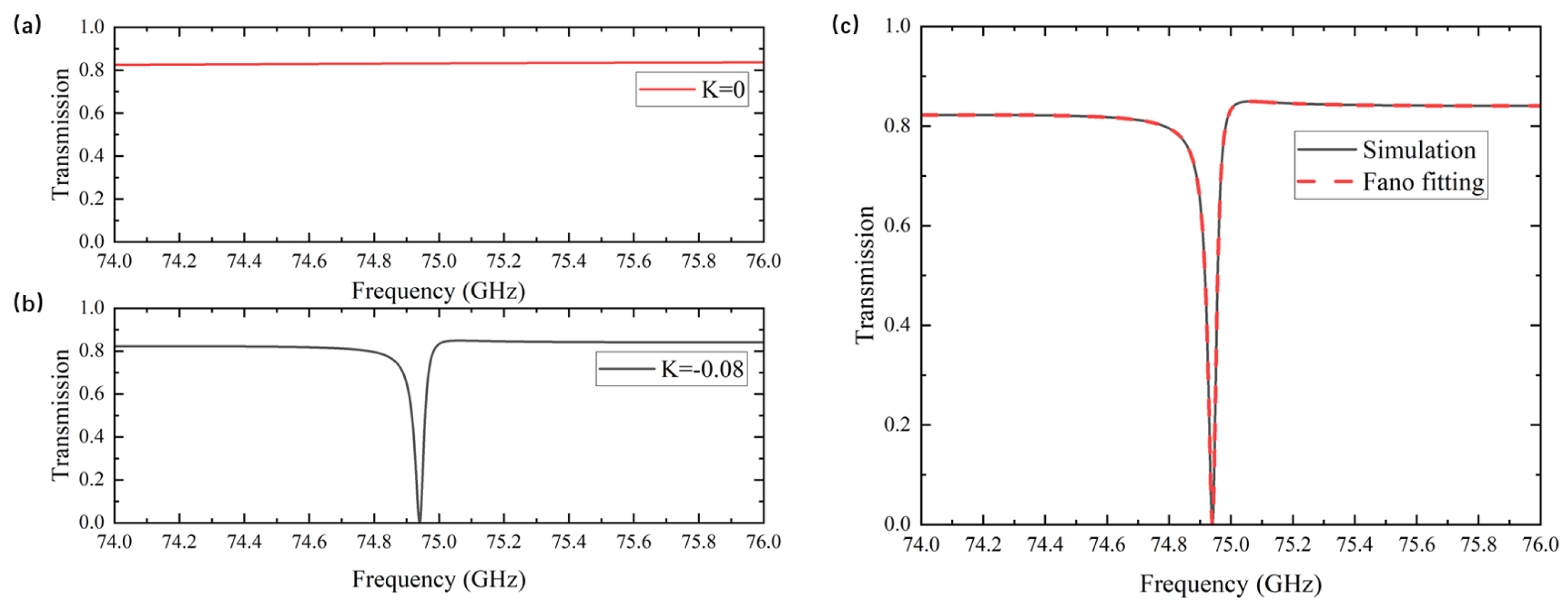

According to the classification of BIC-to-quasi-BIC transitions, a mode arising from the disruption of structural symmetry is referred to as a symmetry-protected BIC. Such quasi-BIC modes are characterized by extremely narrow resonance linewidths and exceptionally high Q-factors. As shown in

Figure 2a, when the unit cell remains fully symmetric, no transmission peak appears within the investigated frequency range. Once the structural symmetry is broken, the originally ideal BIC mode becomes perturbed, giving rise to a leakage channel through which electromagnetic waves couple to the metasurface resonance, resulting in a sharp transmission peak in the spectrum. The transmission peak observed in

Figure 2b is located at 74.92 GHz and clearly exhibits an asymmetric Fano line shape. Fano resonances originate from the coherent interference mechanism between a discrete state and a continuum state within the same radiation channel. When a narrowband discrete resonance spectrally overlaps with a broadband continuous background, the coherent superposition of their radiation amplitudes can give rise to destructive interference at specific frequencies, thereby producing an asymmetric Fano line shape [

37]. In contrast, metasurface structures support quasi-bound states in the continuum (qBIC) by introducing a slight symmetry breaking that enables weak radiative leakage. The weak radiative response of the qBIC mode inevitably undergoes coherent superposition with the non-resonant continuous background, resulting in an asymmetric spectral profile resembling a Fano resonance. However, this spectral asymmetry does not alter the physical origin of the qBIC mode, which remains governed by weakly coupled radiation leakage induced by symmetry breaking. Therefore, it is necessary to clearly distinguish between their conceptual levels: the qBIC is an eigenmode whose physical essence lies in the suppression of radiative leakage achieved through symmetry breaking, while the Fano resonance is the spectral lineshape manifested when this mode interferes with a background field. In this work, the metasurface structure we designed supports the qBIC mode by introducing asymmetry; this mode interferes with the broadband background of the system, thereby producing a typical asymmetric Fano lineshape in the transmission spectrum.

Therefore, to qualitatively confirm that the observed resonance peak corresponds to a quasi-BIC mode, a Fano line-shape fitting is performed. The fitting results are shown in

Figure 2c, where the red dashed line represents the theoretical Fano curve, and the black solid line represents the simulated data curve. The amplitude interference form of the Fano equation used in this analysis is given in Equation (1):

where

is the complex background amplitude (often expressed in the literature as

),

is a numerical constant,

is the resonance center angular frequency,

represents the transmission coefficient and

is the half-width parameter corresponding to the full width at half maximum (FWHM). Based on the above formulation, the expression for the Q-factor can be derived as

For the spectrum shown in

Figure 2b, the Fano fitting was performed using a MATLAB R2021b program. The initial parameters were set as

,

, and

was initialized to the average transmission coefficient of data points 10% away from the resonance frequency on both sides, yielding a value of approximately

. Parameter B was automatically determined based on the coherent destructive interference condition, thus eliminating the need for manual assignment. After running the program, the parameters involved in Equations (1)–(3) were fitted and calculated based on the provided data file.

To intuitively reveal the resonant physical mechanism of symmetry-protected BICs, this study performs a multilevel decomposition analysis of the induced current density based on the Cartesian coordinate system. This approach is a commonly adopted method for elucidating the physical mechanism of BICs, and the corresponding mathematical expressions are given as follows [

38]:

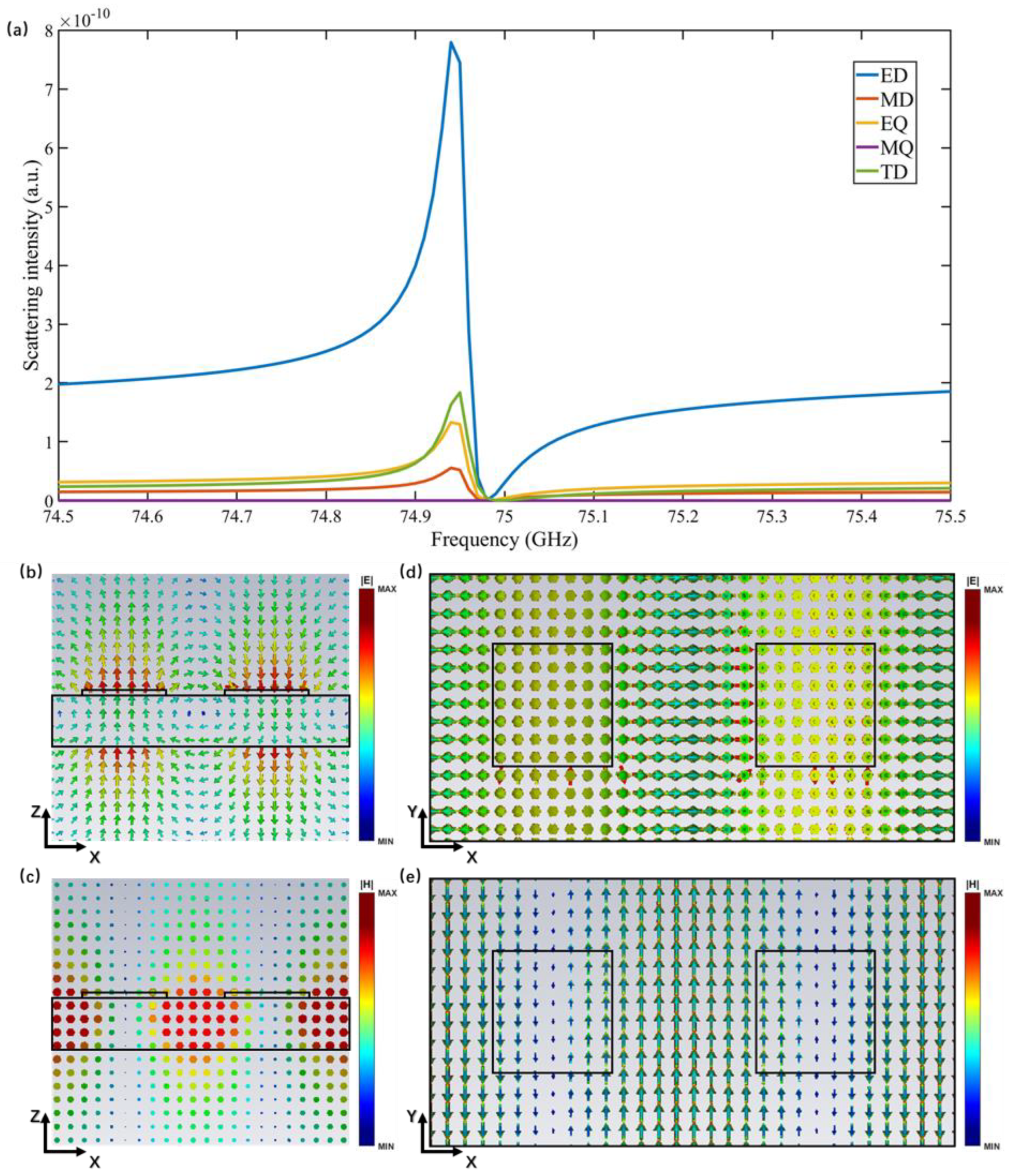

Since several higher-order multipole components contribute negligibly to the overall resonance, they are omitted in this study. Instead, five primary multipole terms are considered: the electric dipole (ED), magnetic dipole (MD), electric quadrupole (EQ), magnetic quadrupole (MQ), and toroidal dipole (TD). As shown in

Figure 3a, the resonance of the metasurface is predominantly governed by the electric dipole term, while MQ, EQ, MD, and TD components are significantly suppressed. In electromagnetic scattering or resonant systems dominated by electric dipole excitation, characteristic field distribution patterns typically emerge.

Figure 3b,c present the electric and magnetic field distributions in the X–Z and

Figure 3d,e present the electric and magnetic field distributions in X–Y planes. The electric field mainly varies along the X-axis and exhibits pronounced enhancement and polarity reversal at the two ends of the resonator. Within the resonator region, the electric field is strongly concentrated around the rectangular pillars and gradually decays with increasing distance. Distinct polarization regions appear on both sides of the structure, consistent with the features of an electric dipole–dominated resonance. The magnetic field distribution further validates these observations. The magnetic field forms a ring-like pattern around the resonator, with its peak regions complementing those of the electric field. Moreover, the magnetic field maintains clear symmetry along the Y-axis, which aligns well with the expected characteristics of an electric dipole–driven resonant mode. Given that the structure is excited by an X-polarized plane wave, the two aluminum pillars, oriented parallel to the electric field, naturally induce a strong oscillating electric dipole moment along the X-axis. The subsequent multipole decomposition analysis and field distribution patterns confirm that this ED mode is indeed the dominant resonance mechanism.

To further analyze the characteristics of the electric dipole resonance, a parametric sweep of the structural parameter

was conducted. The scanning range was set from −0.2 mm to 0.2 mm with a step size of 0.02 mm, yielding 21 transmission spectra corresponding to different values of

. The following

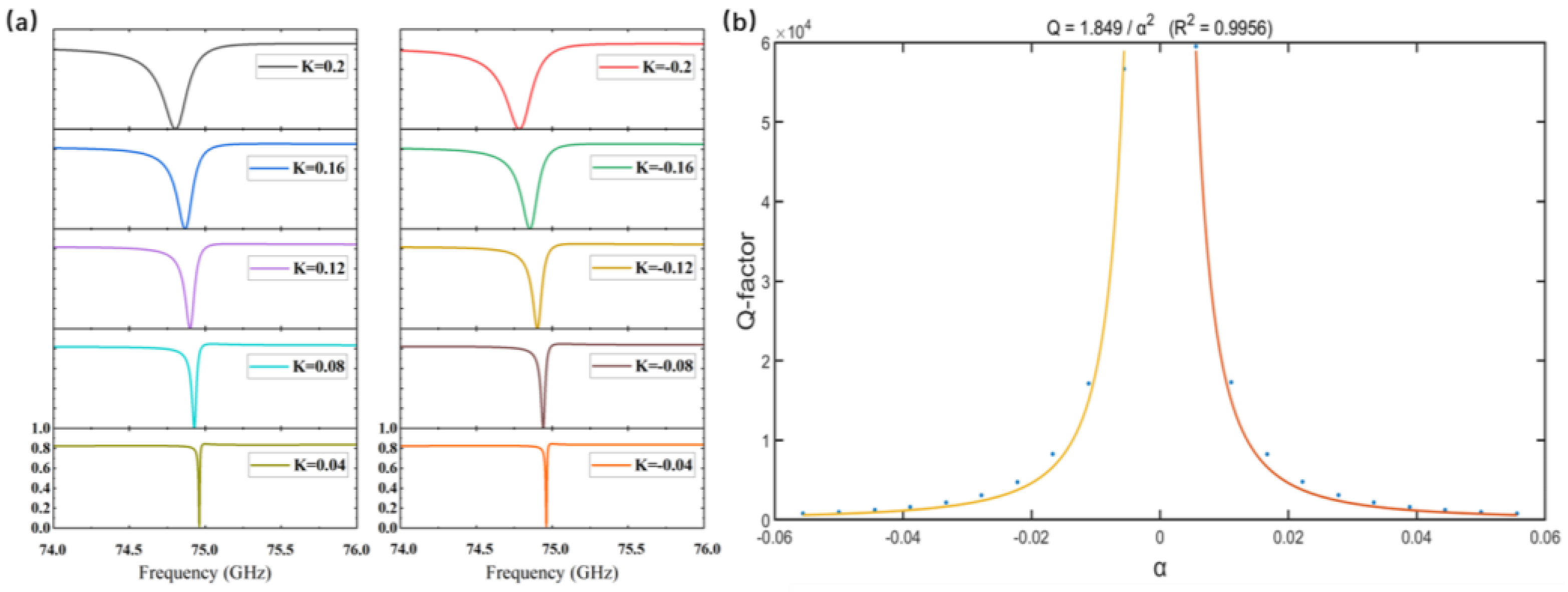

Figure 4a shows the parameter scan results for 10 sets of data. As observed, when

increases from −0.2 mm to 0.2 mm, the resonance linewidth of the transmission peak first narrows and then gradually broadens. When

mm, the transmission peak completely vanishes, forming a distinct transition point.

Overall, the resonance linewidth exhibits a strong dependence on the absolute value of : a smaller corresponds to a more symmetric structure, resulting in a narrower and sharper resonance peak; conversely, a larger indicates stronger symmetry breaking and leads to a significant broadening of the linewidth. In addition, as decreases, the resonance frequency undergoes a slight blue shift and gradually approaches 74.92 GHz.These observations demonstrate that when mm, the structure supports an ideal BIC mode in which electromagnetic energy is entirely confined within the structure without radiating into free space. When , symmetry breaking converts the BIC into a quasi-BIC (qBIC) mode, opening a radiation channel. The stronger the symmetry breaking (i.e., the larger ), the wider the radiation channel becomes, resulting in increased energy leakage.

To quantitatively describe the relationship between the degree of symmetry breaking and the Q-factor, an asymmetry parameter is introduced as

. Based on the simulation results, the Q-factors corresponding to 20 sets of data (excluding the case

) were calculated and fitted as a function of

, as shown in

Figure 4b. The fitting result indicates that the Q-factor follows the relation

with a coefficient of determination

, demonstrating a clear scaling behavior of

. This scaling law suggests that by precisely controlling the asymmetry parameter, the resonance frequency and linewidth can be effectively tuned within a desirable design range.

In the design of metasurface structures, variations in geometric parameters can significantly influence the overall resonance characteristics. To further investigate the effects of different structural parameters on the quasi-BIC mode of the asymmetric metasurface, parametric sweeps were performed for the lattice period, initial spacing between the aluminum pillars, pillar height, and pillar length, while keeping

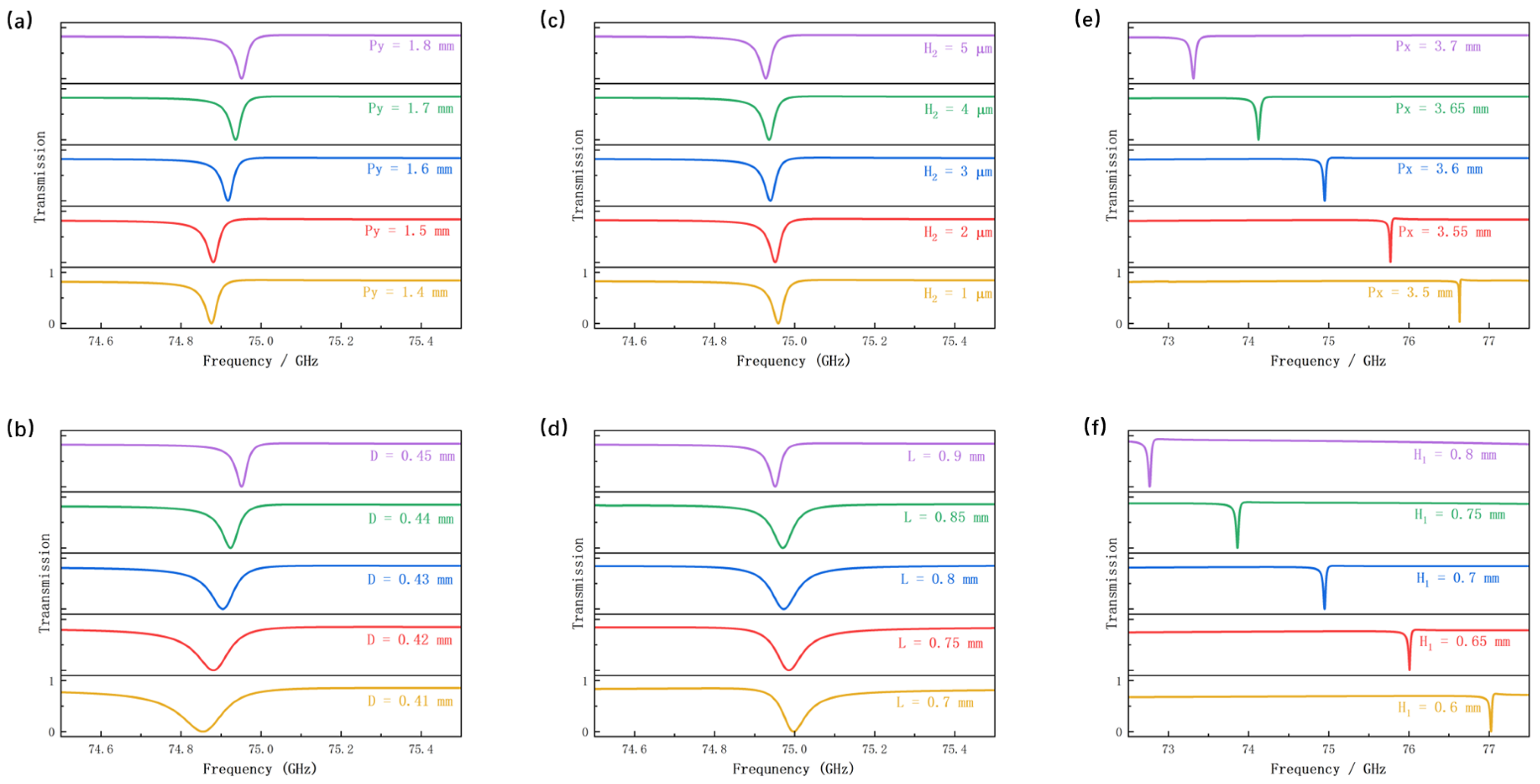

fixed. During the analysis of each individual parameter, all other parameters were kept constant. As shown in

Figure 5a,b, when the parameter

increases from 1.4 mm to 1.8 mm, and the spacing

increases from 0.41 mm to 0.45 mm, the resonance frequency shifts toward higher frequencies, accompanied by a noticeable narrowing of the resonance peak. This behavior can be explained using the LC equivalent resonance model, where the resonance frequency is given by

where

and

represent the equivalent inductance and capacitance, respectively. As

increases, the near-field coupling between adjacent unit cells becomes weaker, leading to a reduction in the equivalent capacitance

, and consequently, an increase in the resonance frequency. Meanwhile, the weakened coupling causes the electromagnetic energy to be more strongly confined within each individual resonator, reducing radiation loss through lattice coupling and resulting in a narrower resonance linewidth. Similarly, increasing the spacing

reduces the effective capacitance between the aluminum pillars, causing the resonance to shift toward higher frequencies.

Figure 5c,d illustrate the influence of the geometric dimensions of the aluminum pillars on the resonance behavior. As the pillar length and thickness increase, the resonance frequency shifts toward lower values and the resonance linewidth becomes significantly narrower. This occurs because increasing the pillar thickness effectively enlarges the conductor cross-sectional area, thereby increasing the equivalent inductance

. Moreover, the two aluminum pillars act as the plates of a capacitor, and enlarging their length increases the equivalent capacitance

. According to the inverse relationship between resonance frequency and the LC parameters, increases in both

and

lead to a lower resonance frequency. At the same time, the resonance peak becomes sharper, corresponding to an enhancement of the Q-factor. The Q-factor, which characterizes the ratio of stored energy to energy loss, satisfies the relation

, where

is the equivalent resistance. An increase in pillar thickness enlarges the conductor’s cross-sectional area, reducing the resistance

and thus increasing the Q-factor. Similarly, increasing the pillar length raises the capacitance

, which also contributes to a higher Q-factor.

Figure 5e illustrates the influence of the lattice period

along the polarization direction (X-axis). As

increases from 3.5 mm to 3.7 mm, a pronounced redshift of the resonance frequency is observed. This trend is opposite to the blueshift induced by increasing

, indicating that distinct physical mechanisms are involved. While the effect of

is mainly governed by near-field coupling between adjacent unit cells, the resonance behavior along the polarization axis is dominated by surface lattice resonance (SLR) conditions. SLR modes originate from the collective coherent oscillation of electric dipoles coupled through diffractive fields. Consequently, the SLR wavelength strongly depends on the lattice period parallel to the electric field, namely

. An increase in

effectively extends the collective resonance wavelength, driving the resonance toward lower frequencies (redshift). In addition, the linewidth broadening observed at larger

suggests that the collective interference condition becomes less ideal, leading to enhanced radiative damping.

Finally,

Figure 5f depicts the effect of the substrate thickness

on the transmission characteristics of the metasurface. As

increases, the resonance frequency exhibits a clear redshift toward lower frequencies. This behavior can be attributed to variations in the effective permittivity of the surrounding medium. Since the refractive index of the PI substrate (

) is significantly higher than that of air, increasing the substrate thickness results in a larger proportion of the electromagnetic near field being distributed within the high-index medium. As a result, the effective permittivity increases, leading to a reduction in the resonance frequency. Accompanied by this redshift, the resonance peak gradually broadens, indicating a decrease in the Q factor. This observation implies that thicker substrates introduce higher dielectric losses, thereby weakening the strong energy confinement capability of the quasi-BIC mode.

In summary, the resonance characteristics of the metasurface exhibit high sensitivity to its three-dimensional geometric parameters. By employing the LC equivalent circuit model, resonance frequency and Q-factor can be effectively tuned, enabling independent or synergistic optimization of structural performance and providing valuable guidance for the design of high-performance microwave metasurfaces.

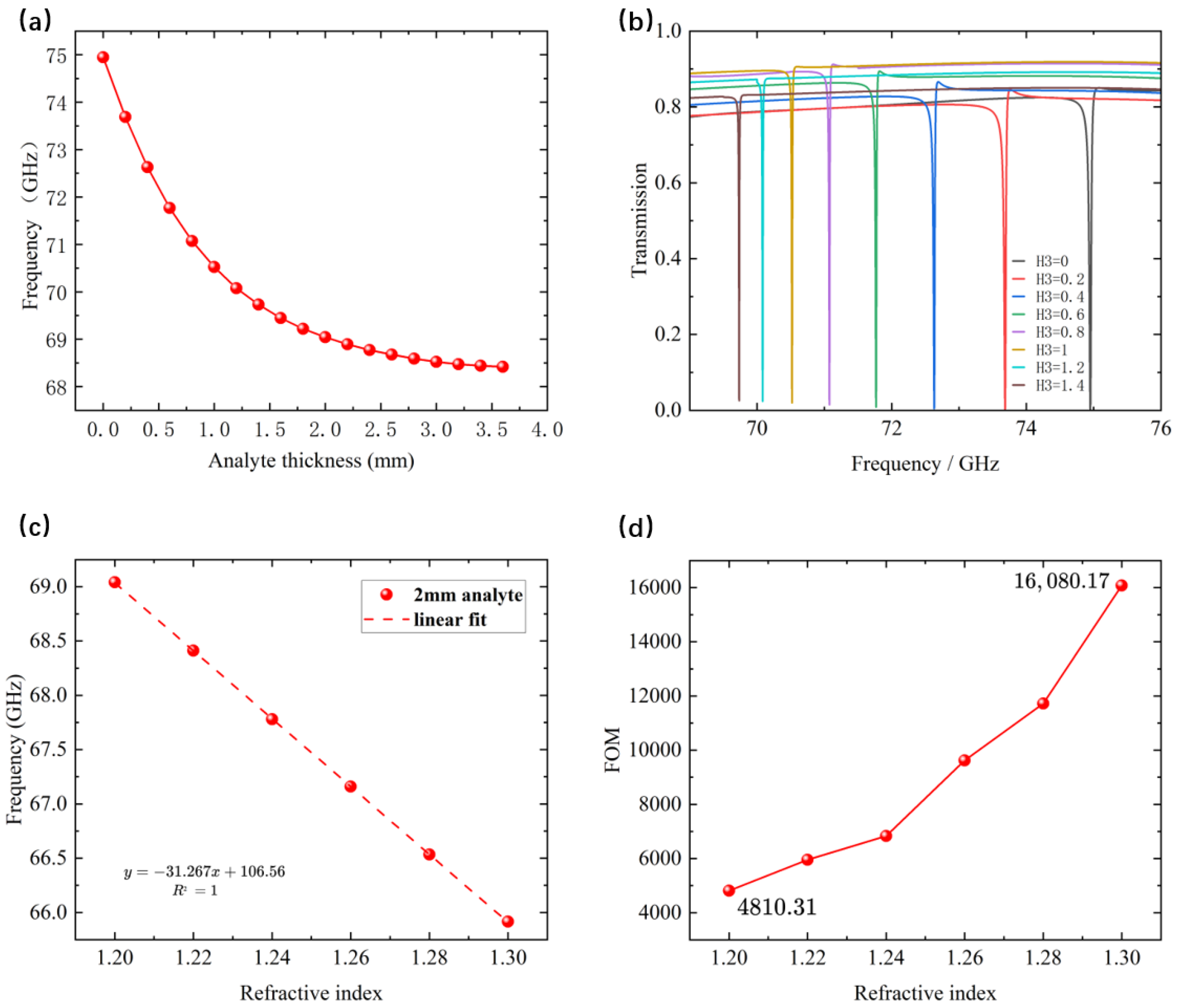

To evaluate the sensing performance of the proposed quasi-BIC microwave metasurface, an analyte layer was introduced onto the surface of the structure, and the resulting resonance shifts caused by variations in its thickness and refractive index were systematically analyzed. First, the refractive index of the analyte was fixed at 1.2, while its thickness was varied from 0 mm (i.e., no analyte) to 3.6 mm in increments of 0.2 mm. The simulation results are shown in

Figure 6a. Within the examined thickness range, the resonance frequency gradually shifts toward lower frequencies as the analyte thickness increases. This redshift occurs because the analyte increases the effective permittivity surrounding the metasurface. However, since the electromagnetic field associated with the metasurface resonance is primarily concentrated near the aluminum pillars and decays gradually along the

-direction, the upper portion of the analyte couples much more weakly to the structure than the lower portion near the surface. As a result, the contribution of increasing analyte thickness to the overall effective permittivity diminishes, causing the redshift to approach saturation. As shown in

Figure 6a, once the analyte thickness exceeds 2 mm, further increases result in minimal additional frequency shift. Therefore, 2 mm is defined as the saturation thickness, and this value is adopted in subsequent analyses.

Figure 6b presents the transmission spectrum parameter sweep results as the thickness of the sample under test increases from zero to 1.4 mm, with the thickness incremented in steps of 0.2 mm. The figure clearly shows that the redshift trend gradually slows down, while the resonance peak bandwidth becomes progressively narrower.

Figure 6c illustrates the influence of analyte refractive index on the resonance frequency for a fixed thickness of 2 mm. The spherical markers represent the resonance frequencies corresponding to different refractive indices, while the dashed line denotes their linear fit. The absolute value of the slope of this line reflects the refractive-index sensitivity of the metasurface, calculated using

where

is the resonance frequency corresponding to a specific refractive index, and

is the resonance frequency of the metasurface without the analyte. Based on the fitting results, the proposed metasurface achieves a refractive-index sensitivity of 31.267 GHz/RIU, demonstrating an exceptionally high responsiveness to refractive-index variations.

In practical sensing applications, performance evaluation relies not only on the sensitivity

and the quality factor

, but more commonly on a comprehensive metric known as the figure of merit (FOM), which is defined as

where FWHM denotes the full width at half maximum of the resonance peak.

Figure 6d presents the FOM values calculated using the sensitivity obtained in

Figure 6c for different refractive indices. The results show that, with the analyte thickness fixed at 2 mm and the refractive index increasing from 1.2 to 1.3, the FOM rises rapidly from 4810.31 to 16,080.17, indicating an exceptionally high upper performance limit. Since the thickness of the sample under test is fixed, the sensitivity is a constant value as calculated above. Therefore, the improvement in the FOM indicates that, with increasing refractive index, the full width at half maximum decreases, resulting in a narrower resonance peak. In summary, the proposed quasi-BIC microwave metasurface exhibits high sensitivity and extremely large FOM values in refractive-index sensing, demonstrating its strong potential for microwave sensing applications based on symmetry-breaking-induced qBIC modes.

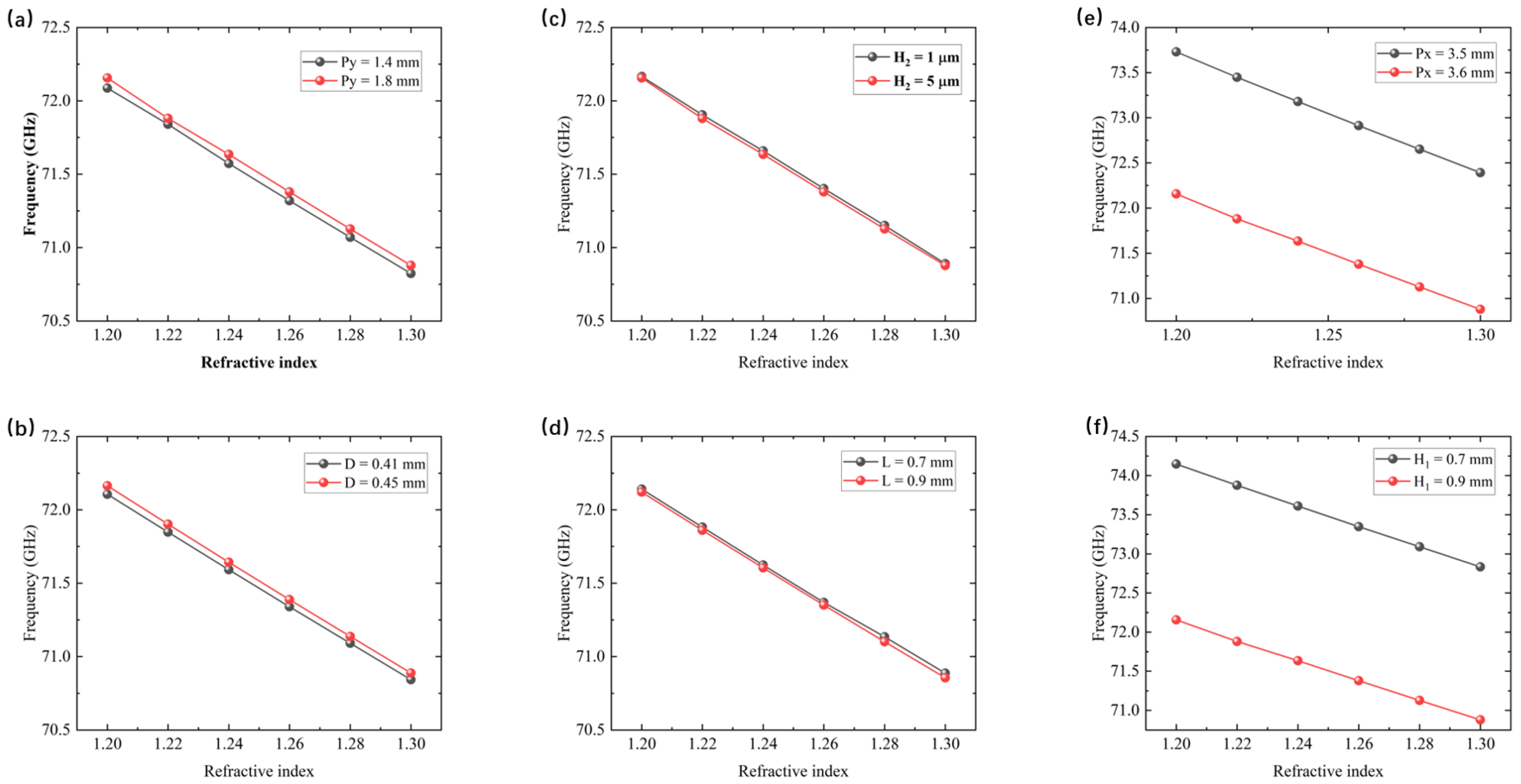

The primary objective of this study is to exploit the theoretically infinite quality factor (Q factor) associated with bound states in the continuum (BICs) to enhance the sensing performance of a microwave metasurface sensor. In this process, the underlying physical mechanisms are systematically investigated through numerical simulations. Although the proposed metasurface has not yet been experimentally fabricated or validated, the robustness of its refractive-index sensitivity is thoroughly evaluated from a simulation perspective, and the corresponding results are presented in

Figure 7. Specifically, following a procedure similar to that used in the analysis of structural-parameter effects on the transmission spectrum, one structural parameter is investigated at two different values while all other parameters are kept constant. Under the condition that the thickness of the analyte layer is fixed at 0.5 mm, the resonance frequency shifts induced by variations in the refractive index are extracted and compared. The results reveal that, despite the different parameter values considered, the magnitudes of the frequency shifts are nearly identical, which is manifested in

Figure 7 by two parallel fitted linear curves. Based on these observations, it can be reasonably inferred that minor deviations in certain structural parameters arising during the fabrication process would not significantly degrade the refractive-index sensitivity of the sensor. This finding demonstrates that the proposed metasurface sensor exhibits good robustness in terms of refractive-index sensing performance.

Finally,

Table 1 provides a performance comparison of several previously reported microwave refractive-index sensors, listing key parameters including operating frequency band (GHz), quality factor

, FOM value, and refractive-index sensitivity. The comparison clearly shows that the metasurface sensor designed in this work achieves an ultra-high Q-factor due to its extremely narrow resonance linewidth. In addition, its relatively high refractive-index sensitivity leads to a significantly enhanced FOM. Overall, the proposed sensor outperforms existing microwave sensing approaches across multiple key metrics, demonstrating its pronounced advantages in microwave refractive-index sensing applications.