1. Introduction

With the swift expansion of ocean resource development, underwater exploration, and the need for high-speed wireless communication, traditional acoustic communication methods are increasingly insufficient to meet the bandwidth, rate, and security demands of next-generation underwater sensor networks and vehicles [

1]. In recent years, Underwater Wireless Optical Communication (UWOC) has emerged as a pivotal technological solution to overcome the “last mile” challenge, thanks to its high bandwidth, low latency, and resistance to electromagnetic interference [

2,

3,

4]. Notably, significant advancements have been achieved in leveraging beam technology for communication purposes, particularly through the use of vortex beams characterized by helical phase fronts. These beams facilitate the simultaneous transmission of multiple information streams along the same spatial path, substantially boosting communication capacity and spectral efficiency [

5,

6].

However, seawater, as a complex optical channel, not only exhibits strong absorption and scattering losses but is also affected by oceanic turbulence (OT) driven by temperature and salinity gradients. This leads to random wavefront distortions, intensity scintillations, and beam wander, significantly limiting the reliability and transmission distance of communication links [

7,

8,

9]. Given the limitations of traditional technologies in underwater communication, it is of great importance to conduct in-depth research on the propagation characteristics of beams carrying Orbital Angular Momentum (OAM) [

10]. OAM beams, with their unique disturbance resistance and high mode purity, are expected to significantly enhance the robustness and spectral efficiency of UWOC systems [

11]. This research direction not only provides new ideas for addressing the challenges currently faced by underwater communication but also lays a solid theoretical foundation for further exploration of the more promising Airy vortex beams [

12].

In 2007, Siviloglou et al. [

13] proposed a finite-energy Airy beam, whose self-focusing, self-healing, and diffraction-free characteristics offered new possibilities for beam propagation in complex media. Based on this, the Ring Airy-Gaussian Vortex (RAiGV) beam emerged, combining the excellent propagation characteristics of Airy wave packets with the OAM degree of freedom of optical vortices, thus opening up a new physical dimension for underwater long-distance and high-capacity information transmission [

14,

15]. The RAiGV beam can achieve abrupt focusing at a preset distance, significantly enhancing the light intensity at the receiving surface, thereby effectively suppressing power attenuation caused by seawater absorption and scattering [

16]. Meanwhile, its ring-shaped intensity distribution and phase singularity can reduce the scintillation index and mode crosstalk caused by OT. Moreover, by adjusting parameters such as the distribution factor

b, topological charge

m, and initial ring radius

r0, flexible trade-offs can be made between focal depth, focal spot shape, and turbulence resistance, providing a dynamically controllable optical field platform for underwater multiplexing communication and particle manipulation [

14]. Although the propagation characteristics of ring Airy vortex beams in the atmosphere and free space have received widespread attention, their evolution laws in OT channels, OAM mode stability, and self-focusing-turbulence coupling mechanisms still lack systematic research [

2]. Existing work mostly focuses on single-point scintillation or intensity wander measurements, failing to reveal the impact of focal position movement under different

b values on the non-monotonic evolution of the scintillation index. There is also a lack of quantitative assessment of far-field mode crosstalk and OAM spectrum evolution [

17].

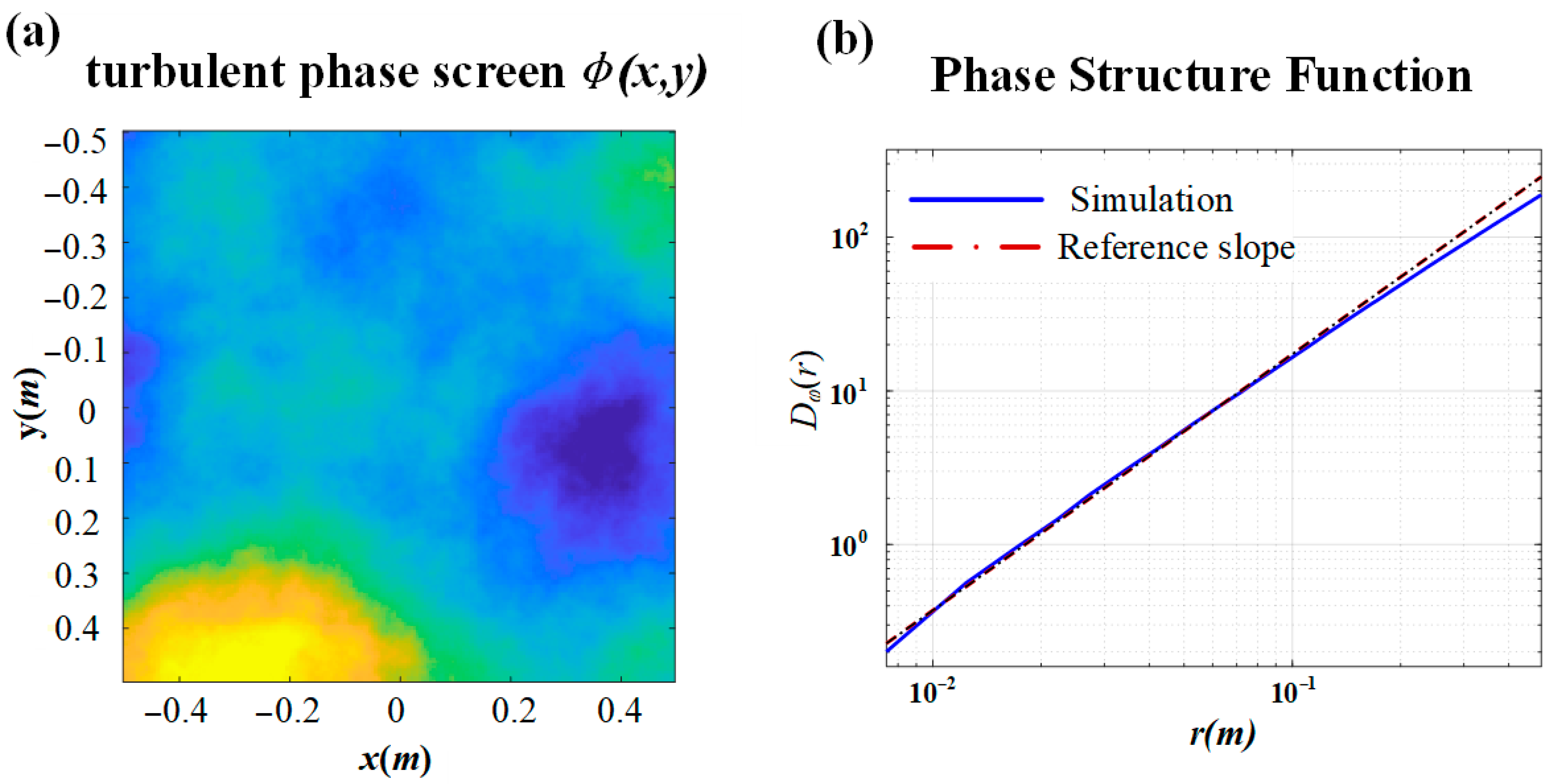

To overcome the above research bottlenecks and provide reliable design basis for underwater OAM multiplexing communication, this paper investigates the propagation characteristics of RAiGV beams in OT. Firstly, based on the Nikishov spectrum and angular spectrum propagation method [

18], a combined numerical model based on angular spectrum and phase screen is established to systematically analyze the effects of distribution factor

b, topological charge

m, and turbulence intensity

σ2 on light intensity distribution, scintillation index (SI), and OAM detection probability (DP). Secondly, by combining the analytical focal length formula with the light field intensity, the quantitative correspondence between self-focusing positions and scintillation valleys is revealed, and a near-field-far-field turbulence resistance trade-off criterion is proposed. Finally, by comparing the light intensity distribution, SI, and DP under different parameters, design references are provided for underwater OAM communication systems.

3. Simulation

Let

A0 = 1,

λ = 532 nm,

a = 0.05,

b = 0.1 to 0.15,

r0 = 1 mm, and

w = 0.5 mm. The Rayleigh range of the RAiGV beam is given by

ZR =

kw2/2. Utilizing these parameters, this paper employs the Angular Spectrum Method (ASM) to simulate the underwater propagation of RAiGV beams.

Figure 2 illustrates the evolution of intensity and phase along a 50 m transmission path under different initial parameter settings for the RAiGV.

Figure 2a illustrates the scenario under no-turbulence conditions (

σ2 = 0), where for

l = 1 and distribution factor

b = 0.1, the beam begins to show significant focusing behavior at approximately

z ≈ 15 m. The beam demonstrates typical annular Airy acceleration behavior, with its main energy moving along a curved trajectory toward the center. A significant self-focusing occurs at

z ≈ 25 m, where the focal region’s intensity sharply increases, while the central position maintains a persistent zero-intensity dark core due to the vortex phase.

Figure 2b shows that when

b = 0.12, the Airy characteristics of the beam are partially suppressed, resulting in a noticeable delay of the self-focusing distance to approximately

z ≈ 36 m, and a reduction in intensity at the focal point.

Figure 2c depicts the scenario for

l = 5, where the diameter of the beam’s dark core increases. The higher-order vortex mode exhibits a stronger divergence tendency during propagation, with weakened self-focusing capability and a rearward shift in the focal position. The phase distribution displays a typical multi-helix structure, reflecting the structural instability of higher-order OAM modes.

Figure 2d illustrates the impact of moderate ocean turbulence (

σ2 = 0.5), where the beam structure is significantly disrupted. The Airy side lobes and acceleration trajectory gradually become blurred, and the central dark core undergoes deformation and drift.

In summary, as depicted in

Figure 2, the distribution factor

b determines the beam’s Airy pattern and initial energy distribution, the topological charge

l influences the dark core scale and mode stability, and the turbulence intensity

σ2 dominates the degree of beam structure disruption, making it a key factor affecting long-distance propagation performance.

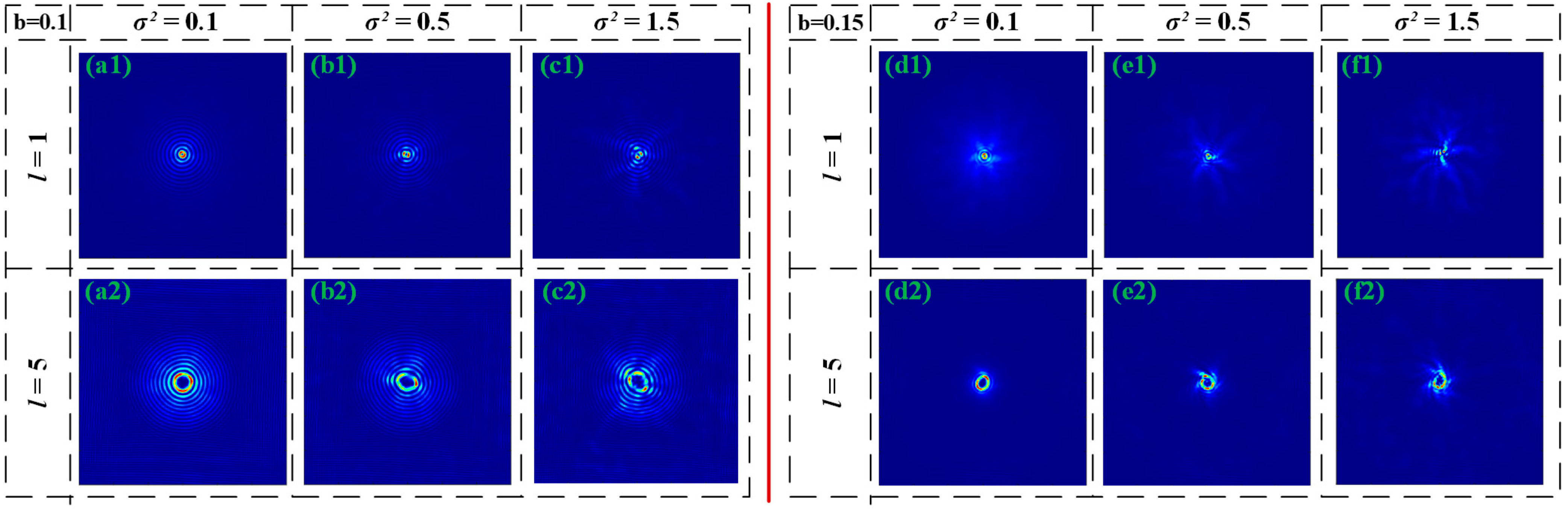

Figure 3 illustrates the light intensity distribution of RAiGV beams with distribution factors

b = 0.1 and

b = 0.15 after propagating 50 m through a marine turbulent channel under varying turbulence intensities. It also compares the structural retention capabilities of topological charges

l = 1 and

l = 5. As shown in

Figure 3(a1–c2), for

b = 0.1 under

σ2 = 0.1, both types of vortex beams maintain relatively intact annular structures. The central dark core of

l = 1 remains clearly defined with good symmetry

Figure 3(a1), while the higher-order dark core of

l = 5, though larger in size, shows no significant structural degradation

Figure 3(a2).

As depicted in

Figure 3(b1,b2), increasing turbulence to

σ2 = 0.5 induces asymmetric distortion in the main beam, with slight displacement of the central dark core. Particularly for the higher-order vortex, due to its more complex phase structure, its outer ring experiences greater perturbation. As shown in

Figure 3(c1,c2), at

σ2 = 1.5, the beam with

l = 1 exhibits pronounced collapse, while the beam with

l = 5 demonstrates stronger dark core boundary distortion and even annular structure fracture, indicating that higher-order OAM modes exhibit weaker turbulence robustness than lower-order modes.

As shown in

Figure 3(d1–f2), when the distribution factor increases to

b = 0.15, the beam’s turbulence resistance significantly decreases. As depicted in

Figure 3(d1,d2), under weak turbulence

σ2 = 0.1, the outer ring of the beam undergoes pronounced disturbance, exhibiting starburst scattering characteristics. Both

l = 1 and

l = 5 beams show energy fragmentation at the spot edges. As shown in

Figure 3(e1,e2), at

σ2 = 0.5, this disturbance intensifies further, causing asymmetric fractures in the main lobe, with particularly pronounced deformation of the high-order vortex dark cores. As shown in

Figure 3(f1,f2), under strong turbulence conditions (

σ2 = 1.5), both beam types exhibit extensive speckle formation, with the original ring structure nearly completely lost.

Compared to the b = 0.1 case, the beam propagation characteristics at b = 0.15 exhibit more fragile self-acceleration and side lobe structures. The increased proportion of Gaussian components renders the overall beam more susceptible to random refraction disruption. While b = 0.1 better preserves the Airy pattern and enhances beam robustness against turbulence, b = 0.15 causes the beam to transition toward a hollow Gaussian-like structure.

4. Discussion

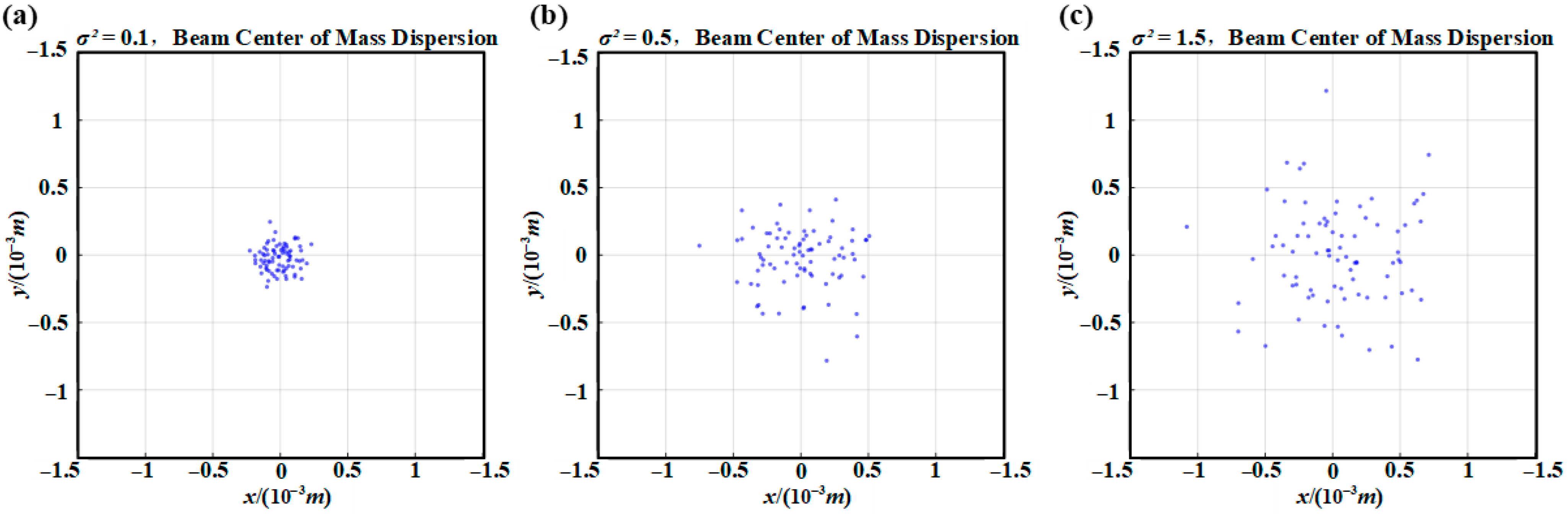

As depicted in

Figure 4a–c, the higher the turbulence intensity, the more pronounced the cumulative effect of random refraction during the propagation of the beam, leading to a continuous increase in the center-of-mass jitter of the RAiGV beam on the receiving plane. Under conditions of

σ2 = 0.1, the beam maintains a high degree of pointing stability. However, at

σ2 = 1.5, it exhibits significant random drift, which directly diminishes the robustness of point detection reception and OAM demodulation systems.

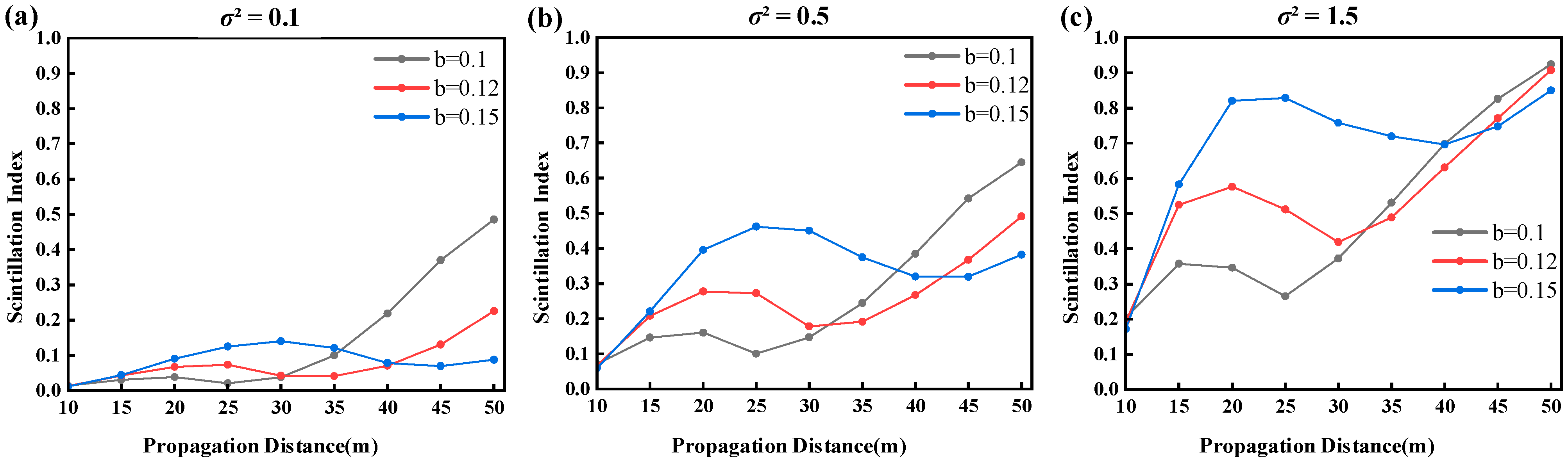

Figure 5 illustrates the variation in the SI for RAiGV beams with a topological charge

l = 1 propagating through OT channels over distances ranging from 10 to 50 m under different distribution factors

b = 0.1, 0.12, and 0.15.

In turbulent environments, the SI of the RAiGV beam with a topological charge l = 1 exhibits a non-monotonic “rise-fall-rise” trend with increasing propagation distance, which is associated with its self-accelerating focusing characteristics. Due to the forward self-focusing behavior of the Airy structure, the energy of the main ring of the beam concentrates sharply near the focal point, reducing normalized intensity fluctuations and leading to a local minimum in SI within this region. Numerical simulations indicate that when the distribution factor is b = 0.1, the beam achieves strong focusing at approximately ; whereas at b = 0.15, the focal position shifts towards the far field to approximately . At the focal point, the sharply enhanced main-ring intensity suppresses normalized intensity fluctuations, reducing SI and forming a typical “valley.”

Under moderate OT

Figure 5b, comparing the three distribution factors

b = 0.1, 0.12, and 0.15 reveals that

b = 0.1 achieves faster focusing near

L ≈ 25 m with higher intensity (SI ≈ 0.1). However, after focusing, the beam intensity rapidly decays, resulting in SI ≈ 0.5. In contrast,

b = 0.12 (SI < 0.4) and 0.15 (SI < 0.5) exhibit slower focusing with smoother intensity evolution, demonstrating superior resistance to scintillation in the far-field region.

Under strong OT

Figure 5c, the behavior is similar to that in

Figure 5b, but with increased overall volatility. The SI at

z = 20 m for

b = 0.1, 0.12, and 0.15 are 0.35, 0.58, and 0.84, respectively, indicating significant perturbation of the beam. At these same values of

b, the SIs in the focal region are approximately 0.21, 0.41, and 0.7, respectively.

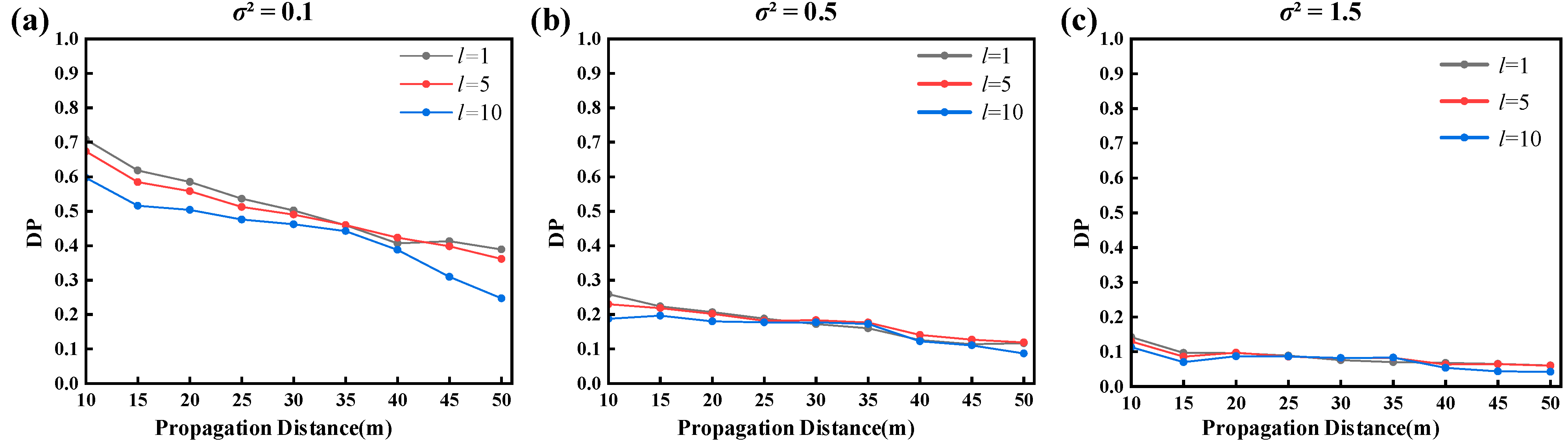

Figure 6 presents the variation in the DP with propagation distance for RAiGV beams with a topological charge

l = 1 under different OT intensities, using three distribution factors

b = 0.1, 0.12, and 0.15. DP reflects the degree of mode integrity preserved when the beam reaches the receiving plane, serving as a crucial metric for evaluating communication link reliability. As the propagation distance increases from 10 m to 50 m, all curves exhibit a pronounced downward trend, indicating that the beam accumulates wavefront distortion and speckle interference caused by OT during long-distance transmission, leading to an increase in SI.

Under three turbulence conditions (σ2 = 0.1, 0.5, 1.5), b = 0.1 consistently maintains the highest DP value with the slowest decay rate. This suggests that the larger Airy tail and self-accelerating behavior provide sustained energy compensation to the main lobe. As b increases, the beam gradually evolves from a typical Airy structure to a hollow Gaussian. With insufficient tail energy and diminished self-compensation capability, it becomes more susceptible to refractive disturbances from turbulence.

In

Figure 6, the variation in DP with propagation distance under different turbulence conditions is shown. As turbulence intensity increases, the beam experiences greater distortion, reflected in a decrease in SI. However, DP, which reflects mode integrity, does not always follow the same trend as SI. The compensation effects from the Airy tail, especially for lower values of

b, help the beam maintain a higher DP over longer distances, even as SI decreases. This is particularly evident in

Figure 6, where DP remains more stable for

b = 0.1, despite the SI decline. Thus, while

Figure 5 illustrates SI variations,

Figure 6 highlights the stability of the beam’s mode (DP), providing a clearer picture of beam behavior under varying turbulence.

Figure 7 illustrates SI evolution for OAM charges

l = 1, 5, and 10 at

b = 0.1, highlighting how vortex orders affect turbulence sensitivity. The SI shows a “rise-fall-rise” pattern with distance. At 10 m,

l = 10 has a lower SI than

l = 5 due to its broader energy distribution, which exceeds the 1 cm aperture, leading to less captured energy and a lower SI. In contrast,

l = 5 concentrated energy is better captured, resulting in a higher SI. Initially, turbulence increases SI, but as the beam focuses, intensity rises, reducing SI. Post-focus, SI increases due to beam diffusion and turbulence. Higher charges like

l = 10 is more sensitive to turbulence, showing higher SI, while

l = 1 shows the least. This sensitivity alters amplitude but maintains the three-stage pattern.

Figure 5 and

Figure 7 depict the universal propagation of ring-shaped Airy beams in turbulence, influenced by self-focusing, energy peak, and re-diffusion, and aperture size.

Figure 8 illustrates the attenuation pattern of the DP with propagation distance for different topological charges

l under a fixed distribution factor

b = 0.1. The DP decreases with increasing propagation distance, with higher topological charges

l exhibiting steeper declines. This ultimate reduction in DP is consistent with the variations in the SI observed in

Figure 6: higher-order vortex structures are more complex, have larger dark cores, and higher phase gradients, making them more susceptible to fragmentation or collapse upon turbulent disturbances.

Figure 8a shows that the DP is highest for

l = 1, maintaining robust pattern recognition capability over long distances, particularly in weak turbulence (

σ2 = 0.1), where

l = 5 exhibits the fastest decay.

Figure 8b,c demonstrate that as turbulence intensifies, it is the strength of the turbulence, rather than the topological charge, that predominantly influences the DP of RAiGV beams.

5. Conclusions

This paper systematically investigates the propagation characteristics of RAiGV beams in a 50 m marine turbulent channel, focusing on the effects of the distribution factor b, topological charge l, and turbulence intensity σ2 on light intensity evolution, SI, and DP. The study reveals that the distribution factor b exerts a significant yet conditional influence on beam transmission performance. Smaller b values (e.g., b = 0.1) enable rapid self-focusing within short distances, yielding high instantaneous peak intensities, reducing short-range normalized intensity fluctuations, and enhancing short-range DP. However, this leads to a rebound in far-field SI and a decline in DP. Larger b values (e.g., b = 0.15) cause the beam to approach a hollow Gaussian profile, exhibiting higher initial SI but smoother intensity evolution, while maintaining more stable SI and DP at long distances.

The vortex structure with topological charge l = 1 exhibits simplicity and significantly superior turbulence robustness compared to higher-order modes (e.g., l = 5, l = 10). The latter modes, characterized by large phase gradients and broad dark cores, are prone to fragmentation and abrupt DP decline under strong turbulence. By jointly controlling b and l, a quantitative trade-off between near-field and far-field performance can be achieved, providing a theoretical basis for optimizing underwater OAM multiplexing communication links.