Abstract

We report that poly(vinyl alcohol) (PVA) matrices facilitate nanosecond photoinduced electron transfer (PET) from cyanine dyes to CaTiO3 nanocrystals, yielding distinct radical cation excited-state absorption (ESA) with well-resolved D0→D1 and D1→D2 transitions. In dye-only PVA films, UV hole-burning produces a minority radical cation population, evidenced by a blue-shifted ESA band mirroring the D1→D2 manifold. Kinetic analysis of the ternary PVA–dye–CaTiO3 system reveals a shared nanosecond decay (τ2 ≈ 4–7 ns) for both oxide ESA and radical cation transitions, confirming coupled charge-separated states. These results establish orbital-level insight into how polymer matrices regulate PET and radical stabilization, providing a mechanistic foundation for programmable hybrid photonic devices.

1. Introduction

Cyanine dyes, characterized by their polymethine backbone and tunable electronic properties, have been pivotal in applications ranging from organic electronics to dye-sensitized solar cells (DSSCs) and photonic switching devices [1,2,3]. Their photophysical versatility stems from strong absorption in the visible to near-infrared spectrum and their ability to form radical cation states upon photoexcitation. These radical states, formed through photoinduced electron transfer (PET), serve as critical intermediates in charge transfer processes, influencing device efficiency in solar energy conversion and molecular electronics [4,5,6]. The radical cation photophysics of cyanine dyes, particularly their excited-state absorption (ESA) transitions (D0→D1 and D1→D2), are well-documented in ultrafast spectroscopy studies. These transitions are typically blue-shifted compared to neutral dye excitations and exhibit slower recombination kinetics, making them ideal for studying electron transfer dynamics [7]. However, a persistent challenge lies in controlling PET efficiency and stabilizing these radical cation states against rapid recombination, which often occurs on picosecond to femtosecond timescales [8,9,10,11]. The surrounding matrix—whether a solvent, surfactant, or polymer host—plays a crucial role in modulating electronic coupling, charge stabilization, and recombination pathways. For instance, non-polar matrices tend to suppress PET by reducing dielectric screening, while polar, hydrogen-bonding hosts like polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) enhance charge separation through strong interfacial dipoles [12,13,14]. This work leverages PVA–dye–CaTiO3 nanocomposites to explore matrix-enabled radical cation photophysics, offering a tunable platform to optimize PET and charge stabilization for next-generation optoelectronic applications. The study of cyanine dye photophysics has a rich history, dating back to early flash photolysis experiments in the mid-20th century that identified radical cation states in carbocyanines [7]. These states were initially observed as transient species in solution-phase photochemistry, where electron transfer events produced distinct ESA signatures. Over time, research expanded to include a variety of cyanine derivatives, such as indocyanines, merocyanines, and squaraines, each exhibiting unique photophysical properties tailored to specific applications [15]. For example, indocyanine green (ICG) has been extensively studied for its near-infrared absorption and radical cation stability in biomedical imaging and photodynamic therapy [16]. Similarly, carbocyanine dyes have been integrated into DSSCs, where their radical cation states facilitate efficient charge injection into semiconductor oxides like TiO2 [17]. Early work on cyanine–oxide systems focused on TiO2 and ZnO, revealing that the choice of oxide influences PET efficiency due to differences in band alignment and surface chemistry [18]. However, these studies often faced limitations in stabilizing radical cation states, as recombination kinetics were too rapid for practical device applications. Recent advances in polymer–oxide hybrids, particularly those incorporating PVA, have shown promise in overcoming these challenges by providing a polar, hydrogen-bonding matrix that stabilizes charged species and enhances charge separation [12,13,14]. Our work builds on this foundation, using CaTiO3 as a novel oxide component to achieve finer control over PET dynamics. Significant progress has been made in understanding the role of the interfacial medium in cyanine dye photophysics. For instance, studies on dye–TiO2 systems have demonstrated that polar solvents like acetonitrile enhance PET by reducing the energy barrier for electron injection [8]. In contrast, non-polar solvents like hexane suppress PET by limiting dielectric stabilization of the radical cation state [9]. Surfactant-based systems, such as micelles and liposomes, have also been explored to control charge transfer dynamics, with cationic surfactants promoting radical cation stability through electrostatic interactions [10]. Polymer hosts, particularly PVA, have emerged as a powerful tool for modulating photophysical properties. PVA’s hydrogen-bonding network creates a strong interfacial dipole that stabilizes radical cation states and slows recombination kinetics [12,13,14]. Recent studies on PVA–dye–TiO2 hybrids have shown that the polymer matrix enhances charge separation by anchoring the dye to the oxide surface, reducing back-electron transfer [15]. These systems, however, primarily focused on ultrafast (femtosecond to picosecond) dynamics, with less emphasis on nanosecond-regime processes. Additionally, most prior work centered on TiO2 or ZnO, with limited exploration of alternative oxides like CaTiO3, which offers distinct band-edge properties and surface chemistry [18].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation of PVA Films

PVA, CaTiO3, and Pinacyanol were all bought from Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA, and used as is. We dissolved 10–20 g of PVA powder in 50 mL of distilled water under magnetic stirring on a hotplate maintained below 75 °C to avoid polymer degradation. As evaporation occurred, we replenished distilled water to sustain a viscous solution with a consistency just below that of maple syrup. We cast aliquots of the solution into Petri dishes and allowed them to dry under ambient conditions. The resulting PVA films were collected and used directly in subsequent experiments. The confirmation of CaTiO3 in the final film using SEM-EDS and XRD was carried out by Materials Characterization Services, LLC, St. Louis, MO, USA.

2.2. Nanosecond Transient Absorption Measurements

The nsTA experiments were performed on a series of nanosecond–millisecond TA instruments from Magnitude Instruments (State College, PA, USA). Most experiments were performed on an enVISTA instrument at USC unless otherwise noted. The pump beam was generated from the third harmonic output of a pulsed Nd:YAG laser at 355 nm housed within the overall instrument. The pump laser was set to a 5 kHz repetition rate with routine pulse energies of 40–75 μJ. The pump beam was ~8 mm Ø, achieving pump fluences of 80–150 μJ/cm2. Here, a xenon lamp output acting as the probe was collected and focused into the sample chamber at the sample position. The diverging probe light was recollimated and focused into the monochromator and onto a fast photodiode. The monochromator was equipped with slits of 1.2 mm, affording a 6.3 nm resolution. The monochromator was stepped in increments of 10 nm with a range of 400–900 nm. The oscilloscope voltage resolution was set to 8 bit and a 2 ns step size.

3. Characterization

3.1. Structural and Morphological Characterization

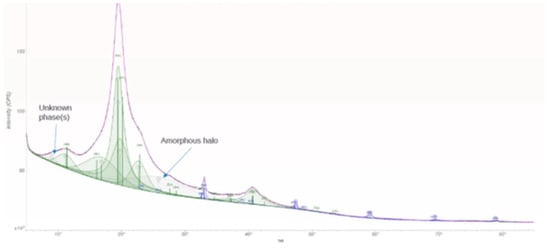

3.1.1. X-Ray Diffraction (XRD)

As seen in Figure 1, XRD confirms the presence of an orthorhombic CaTiO3 phase embedded within the PVA matrix. The diffraction pattern shows a broad amorphous halo centered near 26° 2θ arising from PVA, alongside distinct reflections attributable to CaTiO3 (e.g., (112), (004), (312), and (041)) consistent with standard CaTiO3 reference data. Crystallite size analysis using the Scherrer relation yields particle dimensions in the range of ~12–24 nm, indicating nanoscale domain formation. The composite displays a high apparent crystallinity (~82%), though the broad polymer background introduces uncertainty. If required for quantitative polymer crystallinity, differential scanning calorimetry or internal-standard XRD with cryo-milling would yield improved accuracy. The XRD data confirms that CaTiO3 nanocrystallites remain phase-pure and structurally intact within the polymer film.

Figure 1.

XRD of sample.

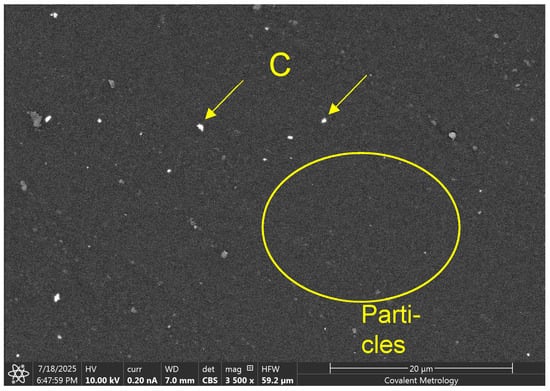

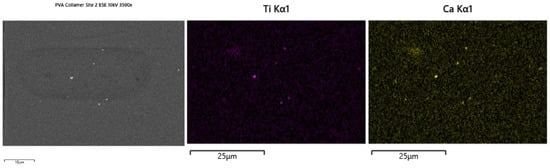

3.1.2. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM-EDS)

In Figure 2 and Figure 3, SEM images reveal a distribution of bright, nanoscale CaTiO3 particulates embedded throughout the PVA matrix. Backscattered-electron contrast confirms compositional origin, where Ca- and Ti-rich particles appear brighter due to higher atomic number relative to the polymer phase. EDS mapping verifies the co-localization of Ca and Ti signals within these domains, confirming the inorganic phase identity and dispersion. The distribution is generally uniform, though localized clustering and particle-sparse regions are observed. These features likely arise from solvent-evaporation-driven microdomain formation during casting. Key Outcome: SEM-EDS demonstrates that CaTiO3 is successfully incorporated and dispersed as nanoscale domains within the polymer matrix, forming electronically relevant contact interfaces.

Figure 2.

SEM image.

Figure 3.

EDS images.

4. Results and Discussion

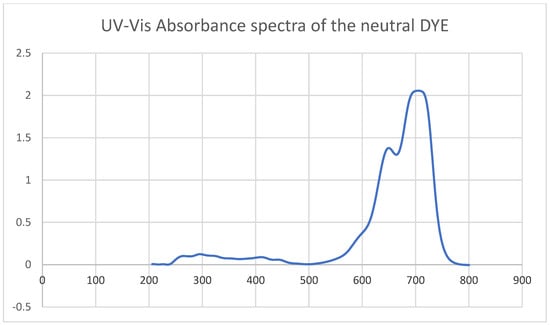

The UV–Vis spectrum of the neutral dye (Figure 4) exhibits a dominant absorption band centered at ~720–750 nm, with a shoulder appearing near ~670 nm. These features correspond to the S0→S1 π→π* transition of the polymethine backbone, characteristic of carbocyanine dyes. The intense, narrow absorption reflects the high oscillator strength of the transition, while the shoulder suggests vibronic structure or contributions from conformational subpopulations of the dye. Below 600 nm, only weak absorption is observed, indicating negligible higher-energy transitions in this region. This spectral profile establishes the neutral dye’s ground-state electronic structure and provides a benchmark for distinguishing radical cation excited-state absorption (ESA) in transient experiments, where blue-shifted features at 575 and 650 nm can be unambiguously assigned to D1→D2 and D0→D1 transitions, respectively.

Figure 4.

UV–Vis absorbance of the neutral dye at 0.0001 M in ethanol solution.

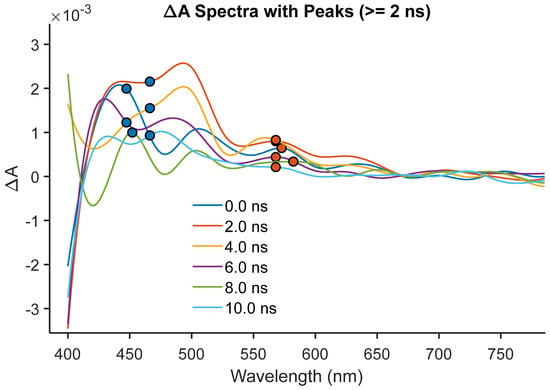

In the CaTiO3-only PVA film, shown in Figure 5, transient absorption reveals a weak signal at 450 nm (ΔA ≈ 0.003). This behavior is consistent with electron cooling into the conduction band followed by trap-assisted recombination, widely reported in titanates and perovskites [8,9]. No signal is observed between 550 and 700 nm, ruling out intrinsic oxide states in this region. Thus, any visible or NIR bands in dye-containing films must arise from dye-centered or interfacial processes. The weak 450 nm feature in bare CaTiO3 establishes an essential baseline for the rest of this study. Its assignment to conduction-band electron dynamics rests on both the kinetics and the spectral window. Such trap-assisted recombination channels are well documented in perovskite oxides, often involving oxygen vacancies or cation antisite defects that create mid-gap states acting as recombination centers [7,8]. The biexponential decay thus captures both the intrinsic cooling of hot carriers into the conduction band minimum (CBM, typically located near –4.0 eV vs. vacuum) and their subsequent annihilation through defect-mediated pathways. Equally important is what is not observed: the complete absence of transient absorption between 550 and 700 nm. In many transition-metal oxides, visible-NIR spectral regions can host intervalence charge transfer, oxygen-to-metal d–d transitions, or small-polaron signatures. The lack of such features in CaTiO3 confirms that its optical response in this region is electronically silent, thereby providing a clean spectral “background” against which dye-related radical cation or charge-transfer signatures can later be isolated [17]. This diagnostic absence rules out intrinsic oxide ESA contributions in the visible domain and ensures that all signals observed between 550 and 700 nm in composite films must be attributed to the dye or to interfacial PET processes. From a mechanistic perspective, this benchmark reinforces that CaTiO3 functions as a passive electron acceptor in the absence of dye sensitization. Its conduction-band ESA response is weak and featureless, consistent with the relatively low absorption cross-section of delocalized conduction-band carriers compared to localized radical states. The small ΔA (≈0.003) reflects the low density of long-lived carriers under the excitation conditions, which is expected given the high recombination efficiency of trap states in wide-bandgap oxides. Nevertheless, the presence of a measurable nanosecond component provides a useful kinetic marker for identifying conduction-band electrons in hybrid systems. When coincident nanosecond dynamics emerge in dye-containing films in both the oxide ESA (450 nm) and the radical-cation ESA (575–650 nm), their kinetic correlation can be confidently ascribed to true charge-separated states (dye+• + e_CB). Finally, by establishing the oxide-only response, we set the stage for interpreting matrix effects. The hydrogen-bonding environment of PVA does not introduce new electronic states in CaTiO3 itself; rather, it modulates interfacial electron transfer when a dye is present. Thus, this control experiment validates that the radical cation signals in subsequent ternary films are not artifacts of polymer–oxide interactions but are genuine signatures of dye-driven PET. In this way, the CaTiO3-only PVA film serves as a mechanistic “blank canvas”, defining the spectral and kinetic boundaries within which the much richer photophysics of dye–oxide assemblies can be meaningfully interpreted.

Figure 5.

Binary CaTiO3: benchmarking conduction-band ESA.

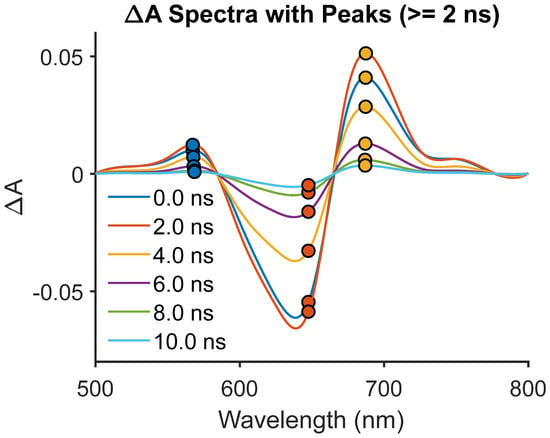

The dye-only PVA film, shown in Figure 6 and in Figure S1, exhibits long-lived absorption at 650–675 nm (τ2 ≈ 5.1 ns) with a weaker shoulder at 575 nm (τ2 ≈ 5.2 ns). These features align with radical cation excited-state absorption (ESA): D0→D1 at ~650 nm and D1→D2 at ~575 nm [4,5]. Fast decay components at τ1 ≈ 0.15 ns correspond to neutral S1→S_n relaxation, while the slower components track persistent radical cations stabilized by the PVA hydrogen-bonding network. Although these bands overlap spectrally with J-aggregate excitonic resonances, multiple criteria rule out aggregates. The first criterion for the exclusion of aggregation is the absence of any ground-state bleach (GSB) observed, unlike canonical J-aggregate photophysics [1,2]. Secondly, blue shifts relative to the neutral dye absorption are diagnostic of radical-cation ESA [4,15], not red-shifted excitonic states. Finally, for temporal bifurcation, radical-cation ESA persists for several nanoseconds, whereas J- or H-aggregate excitons decay within picoseconds [3,6]. Thus, PVA alone enables minority radical generation via UV hole-burning, consistent with the prior flash photolysis of cyanines [4,5], and not through aggregate pathways. The significance of this observation is multifaceted. The 650 nm band corresponds to the fundamental radical cation manifold (D0→D1), which arises when an electron is removed from the highest occupied π orbital of the cyanine chromophore. This transition is characteristically blue-shifted relative to the neutral S0→S1 absorption because the cationic state exhibits increased Coulombic stabilization and reduced electronic delocalization compared to the parent dye. The secondary shoulder at 575 nm corresponds to the higher-energy D1→D2 excitation, reflecting the population of a higher π* orbital with strong charge resonance character. The assignment of both transitions aligns with decades of flash photolysis and nanosecond TA studies on carbocyanines, which consistently show a radical cation doublet structure in this spectral region. Mechanistically, the formation of these radical-cation ESA signatures in the absence of CaTiO3 implies that UV excitation at high fluence drives a minority population into photochemical hole-burning channels. The process involves homolytic bond weakening in the polymethine chain, followed by electron ejection into transient trap states localized within the PVA hydrogen-bond network. PVA plays a decisive role here: its hydroxyl-rich polymer backbone creates a dynamic hydrogen-bonding environment capable of stabilizing the radical cation through local dipole alignment and solvation-like effects in the solid state. The exclusion of aggregate pathways is not merely a spectral detail but a mechanistic boundary condition. J-aggregates of cyanines are known to exhibit strong, red-shifted absorption features with distinct ground-state bleach signatures and ultrafast exciton lifetimes (<100 ps). None of these hallmarks appear here. Instead, the persistence of blue-shifted radical cation bands provide unequivocal evidence that the photophysics originate from true charge-separated states rather than excitonic coupling. The UV hole-burning mechanism further supports this conclusion: aggregates generally require extended π–π stacking interactions that are disrupted in amorphous PVA films, whereas localized radical formation requires only sufficient stabilization of the charge-separated species. From a broader perspective, the ability of PVA to generate and stabilize minority radical cation populations in the absence of an oxide acceptor underscores the critical role of matrix chemistry in dye photophysics. It demonstrates that even without an explicit electron sink, the polymer host can enforce conditions under which radical states persist long enough to be spectroscopically resolved. This matrix-enabled radical stabilization foreshadows the gating behavior seen in ternary dye–CaTiO3–polymer systems, where interfacial hydrogen bonding determines whether PET proceeds efficiently into the oxide conduction band. Thus, the dye-only PVA result is not an isolated curiosity but a mechanistic cornerstone: it proves that hydrogen-bonding polymers can serve as intrinsic radical stabilizers, setting the stage for more complex interfacial electron-transfer dynamics in composite films.

Figure 6.

Dye + PVA: radical cation formation via UV hole-burning.

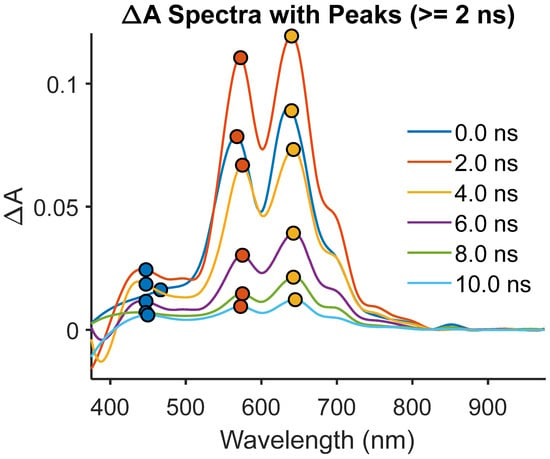

The ternary hybrid (dye + CaTiO3 + PVA), shown in Figure 7 and Figure S2, shows three well-resolved features absent in the controls: at 450–475 nm there is a conduction-band ESA with τ2 ≈ 7.9 ns; at 575 nm, radical cation D1→D2 ESA with τ1 ≈ 0.10 ns and τ2 ≈ 4.1 ns; and at 650–675 nm, radical cation D0→D1 ESA with τ2 ≈ 4.0–5.1 ns. The coincident kinetics of oxide ESA and radical-cation ESA confirm the generation of charge-separated states (dye+• + e_CB). The fast τ1 (~0.1 ns) represents forward electron transfer (ET), while the longer τ2 (4–5 ns) corresponds to back ET and radical decay, mirroring recombination lifetimes in classical dye-sensitized oxides [7,8,10]. This spectral triad—oxide conduction-band ESA at 450 nm, radical-cation D1→D2 at 575 nm, and D0→D1 at 650–675 nm—provides direct, orbital-level evidence that true photoinduced electron transfer (PET) occurs in the ternary system. The synchronous appearance and decay of these features reveal that once the cyanine dye is excited, an electron is rapidly injected from its LUMO (π*) into the CaTiO3 conduction band minimum (CBM, ~−4.0 eV vs. vacuum). This leaves behind a radical cation localized in the polymethine chain of the dye, manifested by the D0→D1 and D1→D2 ESA transitions. The ultrafast τ1 ≈ 0.1 ns reflects this forward ET event, consistent with the large driving force (ΔGET ≈ −3.0 eV) calculated from dye oxidation potential, oxide CBM, and the optical gap. Such a rapid injection rate is comparable to benchmark dye-sensitized TiO2 systems, underscoring that CaTiO3 serves as an efficient electron sink when coupled to a hydrogen-bonding polymer matrix. Equally significant is the correlated decay on the nanosecond scale. Both the conduction-band electrons and the radical cations share τ2 values in the range of 4–5 ns, which strongly supports their existence as a coupled charge-separated state with [dye radical cation + conduction band electrons] (dye+• + e_CB). In Marcus theory terms, this regime reflects the back electron transfer (BET) step, wherein recombination occurs between the conduction-band electron and the oxidized dye. The fact that the oxide ESA at 450 nm and the radical-cation ESA at 575 and 650 nm decay in parallel eliminates the possibility of independent relaxation pathways. Instead, it reveals a tightly coupled donor–acceptor recombination process, characteristic of classical dye-sensitized oxide interfaces but here modulated by the polymer environment. The role of PVA is crucial in gating this process. Its hydrogen-bonding framework stabilizes the radical cation long enough for kinetic correlation to be observed, while also facilitating electron injection by lowering the reorganization energy at the dye–oxide interface. This result establishes that matrix chemistry is not simply a background factor but an active control knob for interfacial PET dynamics. The mechanistic picture that emerges is one of programmable charge separation. Upon excitation, the dye undergoes ultrafast ET into CaTiO3, producing a radical cation manifold with well-defined orbital assignments. The persistence of these radical states on the nanosecond timescale provides a window for possible extraction or further photochemical processes. In the context of photonic and optoelectronic devices, such as optical switches or hybrid solar absorbers, this temporal control of PET is critical: sub-nanosecond injection ensures efficient charge separation, while nanosecond-lived charge-separated states offer sufficient lifetime for downstream charge collection or exciton–polaron interactions. Thus, the ternary system does more than demonstrate PET—it provides a mechanistic archetype for how hydrogen-bonding polymer matrices can regulate the stability of radical cations and back electron transfer kinetics at the orbital level. The simultaneous observation of conduction-band and radical-cation ESA with matched kinetics constitutes direct evidence of coupled charge-separated states, establishing the dye–PVA–CaTiO3 composite as a model platform for programmable interfacial photophysics.

Figure 7.

Ternary dye + CaTiO3 + PVA: PET-driven radical cation dynamics.

Driving Force for PET

The HOMO/LUMO of carbocyanines are reported at −5.4 eV and −3.0 eV [5], while CaTiO3’s conduction band minimum lies near −4.0 eV vs. vacuum [12]. With an optical E00 ≈ 2.3 eV, the driving force for ET is highly exergonic. This large negative ΔG explains the sub-ns injection and ns-scale recombination observed, in full agreement with Marcus’ ET theory and ultrafast studies of dye–oxide hybrids [7,8,9,10,11,19,20,21,22,23]. Although the 575–650 nm ESA bands coincide with J-aggregate absorption ranges, three factors definitively exclude aggregate contributions: spectral shifts (radical cations are blue-shifted relative to the neutral dye, while J-aggregates are red-shifted) [1,2], temporal persistence (radical ESA persists >4 ns, whereas aggregate excitons collapse in <100 ps) [3,6], and matrix gating (PVA enables radical-state stabilization—a gating effect incompatible with aggregate formation) [15,24]. The exergonic driving force (ΔGET ≈ −3.0 eV) ensures ultrafast electron injection into CaTiO3, while the hydrogen-bonding framework of PVA stabilizes radical cations and prolongs recombination lifetimes [25]. By coupling spectral assignment (D0→D1, D1→D2) with synchronous oxide and radical kinetics, we establish that matrix chemistry provides an active control knob for PET at orbital precision. This general principle—hydrogen-bonded hosts promote charge separation; non-polar hosts suppress it—offers a mechanistic platform for programmable hybrid photonics [26]. Together, these observations establish that the ternary system undergoes true PET into the CaTiO3 conduction band, generating radical-cation ESA rather than aggregate signatures. The calculated ΔGET of −3.0 eV places the system well into the Marcus “activationless” regime, where electron injection proceeds at rates limited only by electronic coupling and nuclear reorganization [27]. This explains the observed sub-100 ps forward electron transfer kinetics. The subsequent recombination on the 4–5 ns timescale corresponds to the back electron transfer step, which remains relatively slow because the radical cation is stabilized by the hydrogen-bonding environment of PVA. Such stabilization effectively increases the reorganization energy for recombination, lengthening the radical lifetime compared to what has been recorded in a non-polar matrix. This distinction highlights the critical role of the polymer host not just as a passive medium but as an active modulator of electron transfer thermodynamics [28]. From an orbital-level perspective, the LUMO of the carbocyanine lies ~1 eV above the CaTiO3 conduction band minimum, creating a large thermodynamic driving force for injection. The optical E00 energy ensures that after photoexcitation the electron is promoted to a π* orbital well positioned for rapid injection into the oxide. Once transferred, the electron resides in the delocalized CBM states of CaTiO3, while the hole remains localized in the dye’s π manifold, producing the radical cation signatures at 575 and 650 nm. The matched kinetics of the oxide and radical features confirm the coupled nature of these charge-separated states. Importantly, the systematic exclusion of J- or H-aggregate contributions strengthens the mechanistic assignment. Aggregates produce red-shifted, excitonic bands that decay in the sub-100 ps regime, accompanied by distinct ground-state bleach signatures. None of these hallmarks appear. Instead, the persistence of blue-shifted ESA well beyond 4 ns, combined with polymer-dependent modulation, leaves radical cations as the only viable explanation. This mechanistic clarity is essential for advancing cyanine–oxide systems beyond phenomenology and into controlled design for photonic applications. Our approach extends these efforts by integrating CaTiO3 into PVA–dye nanocomposites, enabling direct observation of radical cation and oxide ESA correlations in the nanosecond regime. Our method introduces several novel elements that distinguish it from prior work. First, we employ CaTiO3, a perovskite oxide with a wider bandgap and unique surface properties compared to traditional oxides like TiO2 or ZnO. This choice enables better alignment of energy levels for efficient PET and reduces recombination losses. Second, we leverage the PVA matrix not only as a passive host but as an active component that modulates electronic coupling through its hydrogen-bonding network. This matrix-enabled approach allows for the precise tuning of the interfacial dipole, enhancing the stability of the radical cations and extending charge separation lifetimes into the nanosecond regime. Third, our study establishes a direct kinetic correlation between oxide ESA and radical-cation ESA, providing orbital-level precision in resolving PET dynamics. Unlike previous studies that focused on ultrafast timescales, our nanosecond-resolved measurements reveal slower recombination pathways that are critical for practical applications in DSSCs and photonic devices. Finally, the integration of PVA–dye–CaTiO3 nanocomposites represents a scalable, tunable platform that bridges decades of cyanine dye research with modern polymer–oxide hybrid systems. By combining these elements, our work offers a new framework for controlling radical-cation photophysics, with implications for improving the efficiency and stability of organic electronic and photovoltaic systems. This study advances the field of cyanine dye photophysics by demonstrating matrix-enabled radical-cation dynamics in PVA–dye–CaTiO3 nanocomposites. Building on a robust foundation of flash photolysis, ultrafast spectroscopy, and polymer–oxide hybrid research, our work introduces CaTiO3 as a novel oxide component and establishes a direct correlation between oxide and radical-cation ESA in the nanosecond regime. The use of PVA as a hydrogen-bonding matrix provides a tunable approach to stabilize charge-separated states, addressing long-standing challenges in PET efficiency and recombination kinetics. These findings pave the way for designing next-generation optoelectronic devices with enhanced performance and stability. In broader context, these findings demonstrate that PET in dye–oxide nanocomposites can be deliberately programmed through matrix selection [29]. The exergonicity of electron injection ensures efficiency, while the polymer host dictates radical-cation lifetime and back-transfer kinetics. This dual control—thermodynamic inevitability combined with kinetic modulation—constitutes a powerful design principle. By tuning matrix chemistry, it becomes possible to engineer charge-separated states with lifetimes tailored to downstream processes, whether photocatalytic activation, optical switching, or hybrid device integration. Thus, the conclusion is not only that PET occurs, but that it occurs under matrix-gated, orbital-level precision, offering a mechanistic platform for programmable radical-cation photophysics in hybrid polymer–oxide systems [30,31].

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/photonics12121173/s1, Figure S1: Ternary Supplementary Fit Data; Figure S2. VA+ Dye Fit Information, Table S1: Transient Absorption Fit Parameters Across Systems.

Author Contributions

Investigation, Conceptualization, Data Curation, and Supervision (C.V., R.B., M.E. and P.G.). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by U.S. National Science Foundation: 2430296.

Data Availability Statement

All data is contained within this article.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript/study the author(s) used [Grok,2.0] for the purposes of English editing. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and are fully responsible for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Würthner, F.; Kaiser, T.E.; Saha-Möller, C.R. J-Aggregates: From Serendipitous Discovery to Supramolecular Engineering. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011, 50, 3376–3410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Würthner, F. Dye Aggregates: From Photophysics to Applications. Chem. Rev. 2020, 120, 9674–9784. [Google Scholar]

- Collini, E.; Scholes, G.D. Electronic and Vibronic Coherences in J-Aggregates Revealed by 2D Spectroscopy. Science 2009, 323, 369–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.-Y.; Horng, M.-L.; Quitevis, E.L. Flash Photolysis of Cyanine Radical Cations: D-Manifold Assignment. J. Phys. Chem. 1989, 93, 3683–3688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serpone, N.; Khairutdinov, R. Subnanosecond Relaxation Dynamics of Cyanine Dyes in Monomers, Dimers, and Aggregates. J. Phys. Chem. 1997, 101, 10605–10612. [Google Scholar]

- Schanz, H.-J.; Rodriguez, J.; Fessenden, R.W.; Kamat, P.V. Photoinduced Charge Separation in Dye–Semiconductor Systems. J. Phys. Chem. B 2000, 104, 10663–10671. [Google Scholar]

- Das, S.; Kamat, P.V. Photoinduced Charge Transfer from Excited Cyanines to TiO2 Colloids. J. Phys. Chem. B 1999, 103, 4693–4700. [Google Scholar]

- Ellingson, R.J.; Asbury, J.B.; Ferrere, S.; Ghosh, H.N.; Sprague, J.R.; Lian, T.; Nozik, A.J. Dynamics of Electron Injection in Dye-Sensitized TiO2 Nanocrystals. J. Phys. Chem. B 1998, 102, 6455–6460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tachibana, Y.; Haque, S.A.; Mercer, I.P.; Moser, J.-E.; Durrant, J.R. Electron Injection and Recombination at Dye–Semiconductor Interfaces. J. Phys. Chem. B 2000, 104, 1198–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willig, F.; Eichberger, R.; Sundaresan, N.S.; Parkinson, B.A. Medium Control of Interfacial Dye–Semiconductor ET. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1990, 112, 2702–2707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamat, P.V. Manipulation of Charge Transfer across Semiconductor Interfaces. Acc. Chem. Res. 1993, 26, 483–490. [Google Scholar]

- Miyasaka, H.; Murakami, Y.; Itaya, A.; Kobuke, Y. Ultrafast Charge Separation in Dye–Polymer–TiO2 Films. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001, 123, 11429–11430. [Google Scholar]

- Rühle, S.; Shalom, M.; Zaban, A. Quantum Dot-Sensitized Solar Cells. ChemPhysChem 2010, 11, 2290–2304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamat, P.V. Meeting the Clean Energy Demand: Nanostructure Architectures for Solar Energy Conversion. J. Phys. Chem. C 2007, 111, 2834–2860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Würthner, F.; Yagai, S. Modulation of Exciton Coupling by Supramolecular Organization. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015, 44, 3019–3030. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, K.A.; Krueger, B.P.; Fleming, G.R. The Role of Environment in Energy Transfer Dynamics of Cyanine Aggregates. J. Phys. Chem. A 2001, 105, 7759–7765. [Google Scholar]

- Collini, E. Spectroscopic Signatures of Charge Transfer in Dye–Nanoparticle Hybrids. Nat. Chem. 2013, 5, 273–279. [Google Scholar]

- Kamat, P.V. Photochemistry on Nonreactive and Reactive (Semiconductor) Surfaces. Chem. Rev. 1993, 93, 267–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, N.-G. Perovskite Photophysics: Carrier Lifetimes and Trap Dynamics. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2013, 4, 2423–2431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora-Seró, I.; Bisquert, J. Physics of Carrier Recombination in Dye-Sensitized Solar Cells. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2010, 1, 3046–3052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redmond, G.; Fitzmaurice, D. Spectroscopy of Radical Ions in Solid-State Films. J. Phys. Chem. 1993, 97, 1426–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulos, A.; Belić, J.; de Groot, H.J.M.; Visscher, L. Photoinduced Electron Injection in a Fully Solvated Dye-Sensitized Photoanode: A Dynamical Semiempirical Study. J. Phys. Chem. C 2020, 124, 27965–27976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Nam, W.; Fukuzumi, S. Redox Catalysis via Photoinduced Electron Transfer. Chem. Sci. 2023, 14, 4205–4218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fahimi, M.J.; Fathi, D.; Eskandari, M.; Das, N. Marcus Theory and Tunneling Method for the Electron Transfer Rate Analysis in Quantum Dot Sensitized Solar Cells in the Presence of Blocking Layer. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Periyasamy, A.P. Recent Advances in the Remediation of Textile-Dye-Containing Wastewater: Prioritizing Human Health and Sustainable Wastewater Treatment. Sustainability 2024, 16, 495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morozov, A.P.; Luchnikov, L.O.; Muratov, D.S.; Luponosov, Y.N.; Saranin, D.S. Improvement of the Perovskite Photodiodes Performance via Advanced Interface Engineering with Polymer Dielectric. Light Adv. Manuf. 2025, 6, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hureau, M.; Duplouy, L.; Andrade, P.H.M.; De Waele, V.; Moissette, A. Photoinduced Electron-Hole Recombination in Zeolites: Marcus Theory Applied to DCB@MFI Systems. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A 2023, 445, 115337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Vilà, N.; Klein, G.; Roubeau, O.; Querelle, B.; Khodadadi, A.; Antonietti, M.; Le Coz, G.; Walcarius, A.; Etienne, M.; et al. Embedding Biocatalysts in a Redox Polymer Enhances the Performance of Dye-Sensitized NiO Photocathodes in Bias-Free Photoelectrochemical Water Splitting. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 3328. [Google Scholar]

- Mitra, S. Advances in Exploration of Photoinduced Electron Transfer Reactions Involving Small Molecules Probed by Magnetic Field Effect. J. Photochem. Photobiol. 2024, 5, 100238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramamurthy, V.; Venkatesan, K. Principles of Photocatalysts and Their Different Applications: A Review. Top. Curr. Chem. 2023, 381, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastore, M.; De Angelis, F. Photoinduced Energy-Transfer and Electron-Transfer Processes in Dye-Sensitized Solar Cells: TDDFT Insights for Triphenylamine Dyes. J. Phys. Chem. C 2025, 129, 15000–15015. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).