Abstract

Water pollution has become a critical issue because of the Industrial Revolution, growing populations, extended droughts, and climate change. Therefore, advanced technologies for wastewater remediation are urgently needed. Water contaminants are generally classified as microorganisms and inorganic/organic pollutants. Inorganic pollutants are toxic and some of them are carcinogenic materials, such as cadmium, arsenic, chromium, cadmium, lead, and mercury. Organic pollutants are contained in various materials, including organic dyes, pesticides, personal care products, detergents, and industrial organic wastes. Nanostructured materials could be potential candidates for photocatalytic reduction and for photodegradation of organic pollutants in wastewater since they have unique physical, chemical, and optical properties. Enhanced photocatalytic performance of nanostructured semiconductors can be achieved using numerous techniques; nanostructured semiconductors can be doped with different species, transition metals, noble metals or nonmetals, or a luminescence agent. Furthermore, another technique to enhance the photocatalytic performance of nanostructured semiconductors is doping with materials that have a narrow band gap. Nanostructure modification, surface engineering, and heterojunction/homojunction production all take significant time and effort. In this review, I report on the synthesis and characterization of nanostructured materials, and we discuss the photocatalytic performance of these nanostructured materials in reducing environmental pollutants.

1. Introduction

The Industrial Revolution has had a negative environmental impact because of the increased release of hazardous materials into the environment [1,2]. Hazardous materials include organic dyes, pharmaceuticals, personal care products, petrochemicals, and pesticides; inorganic hazardous materials include heavy metals and various industrial additives [3]. Hazardous materials cause air, soil, and water pollution. Water pollution is a global environmental concern that threatens billions of people worldwide, particularly those in developing countries [4]. Hazardous materials pose many hidden dangers to human health and the ecosystem. These materials are toxic and cause many health issues, such as lung, liver, and brain damage, as well as carcinogenic diseases and neurological disorders [5,6]. Furthermore, these materials are difficult to degrade and thus accumulate in the environment, i.e., in water and soil [7]. According to the WHO, the water crisis will affect half of the world’s population by 2025 [8]. Therefore, it is a necessity to treat water and soil tainted with hazardous materials. Wastewater treatment has been drawing increasing attention as a research topic, and several methods, including ones that are physical, chemical, and biological in nature, have been utilized to remove hazardous waste [9]. Sedimentation, adsorption, membrane separation, and extraction are some physiochemical methods [10]. Activated sludge and biofilm are commonly used in biological treatment [11]. However, these methods have several drawbacks, as hazardous materials that cannot be decomposed are often still present; they also involve high operating costs, complex operations, and significant sludge production [7,10,12]. Advanced oxidation processes (AOPs) are among the most prominent chemical methods; they involve the generation of active free radicals such as hydroxyl radicals (•OH), superoxide anion radicals (O2•−), and sulfate radicals (SO4•−) to degrade target pollutants into small non-toxic and biodegradable compounds such as carbon dioxide (CO2) and water (H2O) and reduce or oxidize inorganic pollutants so that they become harmless substances and, consequently, secondary pollutants cannot be produced [13,14,15,16]. Fenton oxidation, Fenton-like oxidation, ozone oxidation, sonocatalysis, electrochemical oxidation, and photochemical oxidation are some advanced oxidation processes [14,15,16]. The chemical method of photocatalysis is a promising approach as it is a nonselective method that can be used for a wide range of hazardous chemicals, including both organic and inorganic pollutants, as well as pathogens [16,17,18,19,20]. It is a green process involving the conversion of solar energy into chemical energy [21,22]. AOPs can be controlled by several experimental parameters, for instance, the initial concentration of pollutants, pH, time, and temperature [23]. A semiconducting material can serve as a photocatalyst because of its ability to absorb light and produce free radicals [22,24]. Semiconductors are divided into intrinsic and extrinsic categories based on their purities [25]. Intrinsic semiconductors comprise pure or undoped elements such as germanium and silicon. Extrinsic semiconductors are doped with other impurity atoms to enhance their conductivity and properties, and they fall into two subcategories: n- and p-type semiconductors. In a semiconductor, current conduction is caused by the movement of free electrons and “holes”, which are collectively referred to as “charge carriers” [25,26]. The photocatalytic reaction occurs on the surface of the semiconductor, where photoexcited electrons (e−) and holes (h+) function as reduction and oxidation agents for target pollutants [22].

The fundamental principles of semiconductor photocatalysts are further elucidated in the following paragraphs. Various semiconductors, such as titanium dioxide (TiO2) and zinc oxide (ZnO), have been proposed and investigated as photocatalysts [27,28,29,30,31,32]. However, the efficiency of semiconductor photocatalysts is a concern among researchers; issues regarding sunlight absorption, bandgap, and charge carrier lifetime are fundamental challenges that must be overcome [20].

Nanotechnology is a cutting-edge technology [33]. Nanoparticles (NPs) are particles with dimensions of less than 100 nanometers (nm). Nanomaterials have at least one dimension in nm [34,35]. These nanomaterials can be classified based on their sources, such as, for example, inorganic-based nanomaterial, polymer-based nanomaterial, and nanocomposite materials [35,36]. Nanomaterials possess unique physical, chemical, optical, and electrical properties and a large surface area [21]. Due to their extraordinary properties, they are widely used for various applications, including environmental remediation, photocatalysis, cancer therapy, battery production, and food industry uses [34,37,38,39]. There are several challenges to utilizing nanomaterials in environmental remediation. Some nanomaterials are toxic, causing potential risks to human and aquatic environments and ecosystems [35,40]. A major challenge in nanomaterial development is the toxicity of nanomaterials [41]. The toxicity differs depending on the type of nanomaterial, its physiochemical properties, morphology, size and size distribution, crystalline structure, preparation method, concentration, aggregation, and mobility [35,41,42]. Therefore, before implementing nanomaterials in living systems and environmental applications, it is crucial to thoroughly investigate their long-term toxicity [41]. Mathematical models are useful to simulate the negative impact of nanomaterials on the environment [35]. Analytical techniques must be developed to determine and isolate environmentally relevant concentrations of nanomaterials and controlling factors to enhance or decrease the toxicity of nanomaterials [35,42].

This review presents information about the most recent attempts in the photocatalytic removal of hazardous material, e.g., organic dyes, antibiotics, and hexavalent chromium ions Cr(VI), from water using nanostructure semiconductor heterojunction photocatalysts during the last two years. The review includes a more in-depth discussion about the synthesis of photocatalysts, e.g., bismuth-based oxides, sulfides, oxyhalides, and metal chalcogenides such as MoS2, In2S3, and ZnIn2S4, especially regarding the architecture and mechanism of photocatalysts. It also explores the fabrication of Z-scheme and S-scheme photocatalysts.

2. The Fundamental Principles of Semiconductor Photocatalysts

Photocatalysts are defined as materials that, when exposed to light, modify the rate of a chemical reaction, and photocatalysis is the term for this phenomenon. Photocatalysis is a process that uses light and a semiconductor as a catalyst [43,44]. The photocatalytic ability of a semiconductor is the ability to absorb light energy to generate negative electron (e−) and positive hole (h+) pairs [13,45]. When a semiconductor material is illuminated by light, the electrons in the valence band migrate to the conduction band (CB) to generate positive holes. The wavelength of light must be equal to or larger than the energy band gap of the semiconductor [46]. The negative electron (e−) and positive hole (h+) pairs, i.e., the photogenerated pairs (charge carriers), recombine and release energy in the form of heat. The photogenerated pairs have redox ability [13,45]. The recombination of electrons and holes presents the most difficult challenge in this step. The photogenerated electron-hole pairs can recombine quickly before catalyzing the redox reactions [47,48,49].

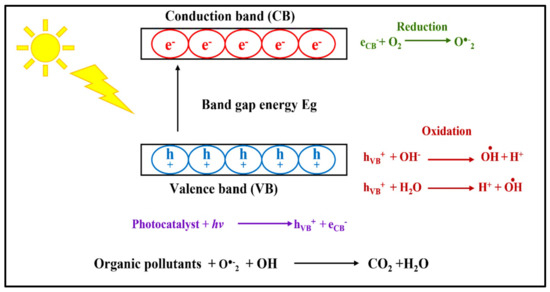

Applications of photocatalysts have been widely recognized in hydrogen production including water splitting and offer promising solutions to environmental issues such as the photodegradation of many environmental pollutants, such as, for example, organic dyes, pharmaceuticals, and pesticides. Photocatalysts can also be used to kill a wide range of microorganisms including fungi, viruses, and bacteria, and to photoreduce heavy metals [3,43,46,50]. Photocatalytic environmental remediation has numerous advantages; it utilizes harmless semiconductors that convert environmental pollution into light of appropriate wavelengths, which is an effective and low-cost technique. Photocatalytic environmental remediation is achieved in four steps [51]. First, the pollutants are transported from the water to the surface. Then, the pollutants are attached to the semiconductor’s surface. The photocatalytic reaction takes place between the pollutants and the semiconductor. Finally, the pollutants are degraded and discharged into the environment [51]. The general mechanism of photocatalytic degradation of organic pollutants in water is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The general mechanism of photocatalytic degradation of organic pollutants in water.

3. Semiconductor Photocatalysts

As previously mentioned, photocatalytic semiconductors are useful for environmental remediation. However, there are several drawbacks that have a negative impact on the efficiency of photocatalytic semiconductors [52,53]. For instance, single-phase semiconductor energy band gaps are inactive when exposed to visible light, while a semiconductor with a narrower band gap can absorb visible light, and a semiconductor with a greater band gap can absorb ultraviolet (UV) radiation [54,55]. Visible light accounts for approximately 45% of sunlight, but UV light accounts for approximately 5% of sunlight [52]. Modification of the electronic and optical properties of semiconductors has been proposed to overcome the abovementioned difficulties, such as the modification of energy band gaps to absorb photons with energy values greater than the semiconductor band gap [56], impurity doping with metals or nonmetals, sensitization with visible light quantum dot co-catalyst loading, and construction of heterojunctions [46,57,58,59]. Recently, construction of heterojunctions has been the most practical and efficient method for enhancing photocatalytic activity [59,60].

4. Basics and Types of Semiconductor Heterojunctions

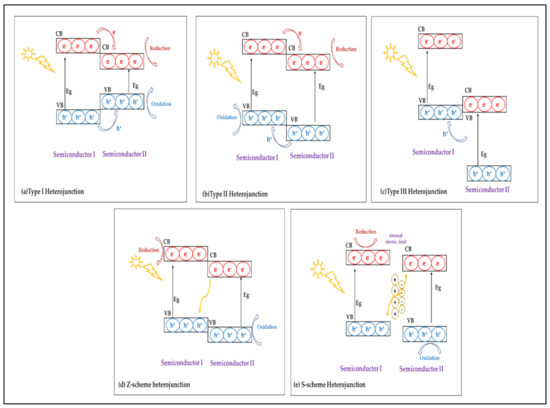

Semiconductor heterojunctions consist of two or more semiconductors with different band gaps [61]. The electric structures of the resulting heterojunctions are able to absorb visible-light-range photons and photogenerate charge carriers, i.e., electron–hole pairs [61]. As shown in Figure 2, the coupling between semiconductors I and II produce three traditional types of heterojunctions based on band gap alignment: straddling gap (type I), staggered gap (type II), and broken gap (type III) [62]. In the type I heterojunction, the VB and the CB of semiconductor I are lower and higher than that of semiconductor II, respectively. This indicates that the band gap of semiconductor I is wider than that of semiconductor II [63,64]. Therefore, holes and electrons can jump from the VB and the CB of semiconductor A to the VB and the CB of semiconductor B, respectively [63,64]. Semiconductor A has more negative CB and VB energy levels than semiconductor B, which has lower VB and CB energy levels than semiconductor I in a type II heterojunction [63,64]. As a consequence, the photogenerated electrons at the CB of semiconductor I move to the CB of semiconductor B, and the holes at the VB of semiconductor II move to the VB of semiconductor I [63,64]. Therefore, the CB at semiconductor II and the VB at semiconductor I act as an electron sink and hole sink, respectively. Based on [64], this leads to electron and hole spatial separation and enhances the charge separation efficiency. As compared with type I heterojunctions, type II heterojunctions perform well in photocatalytic reduction [65].

Figure 2.

Schematic illustration of the band gap alignment of different types of heterojunctions.

The S-scheme heterojunction is another band structure that is similar to the traditional type II, but it differs in the recombination pathway [66]. An S-scheme heterojunction consists of a reduction-type photocatalyst semiconductor and an oxidation-type photocatalyst semiconductor [67]. An internal field is created that causes the photogenerated electrons to flow from the conduction band of the oxidation-type semiconductor to the valence band of the reduction-type semiconductor, and the corresponding photogenerated holes are consumed to balance the Fermi level of the contacting semiconductors [66,67]. Due to the increased likelihood of recombination, electrons and holes located at lower energy levels are more likely to be useful electrons and holes with higher potential for redox processes. As a result, the S-scheme heterojunction can separate electron–hole pairs while maintaining its entire redox potential [66].

The Z-scheme photocatalyst has been proposed as a solution to the low redox capacity of traditional type II heterojunctions [68]. The Z-scheme photocatalyst offers a method of recombining the electron–hole pairs, i.e., charge carriers from the two semiconductors’ lower energy levels recombine with those from their higher energy levels to react with outside molecules [68]. Z-scheme photocatalysts can be classified into direct Z-scheme mediator-free photocatalysts (two elements, i.e., two semiconductors) and indirect Z-scheme photocatalysts (three elements, i.e., two semiconductors and one mediator), and the Fermi level of the composite reaches equilibrium, which is between the original Fermi level of the two semiconductors [26,68]. This interface has a Fermi level between the Fermi levels of the VB of semiconductor I and those of the CB of semiconductor II [26]. The third traditional type of semiconductor heterojunction, i.e., broken gap (type III), possesses a very large band gap as compared with those of the previous types; as a result, there is no overlap band gap between semiconductor I and semiconductor II, and, therefore, there is no interaction, and photogenerated electrons and holes cannot travel from one semiconductor to the other [66]. Other types of heterojunctions comprise metal–semiconductor junctions (Schottky heterojunction) and semiconductor heterojunctions with a carbon material (carbon and graphene) [62].

5. Synthesis Methods for Semiconductor Heterojunctions

5.1. Hydrothermal/Solvothermal Methods

Some of the most commonly used methods to prepare semiconductor heterojunctions are hydrothermal/solvothermal methods [57,69]. The differences between hydrothermal and solvothermal processes are the solvent types. Water and organic solvent are used in hydrothermal and solvothermal processes, respectively [70]. This method is a wet chemical reaction used to crystallize materials into nanostructures, and was introduced by Wang et al. [71]. Hydrothermal/solvothermal methods involve the synthesis of chemicals in a sealed and heated solution above ambient condition under high pressure. The advantage of such methods is that the reaction conditions, such as temperature, time, pH, and other parameters, can be controlled to obtain crystals of different morphologies and sizes [72,73].

5.2. Sol–Gel Method

The sol–gel method is a chemical synthesis method that is commonly used as a bottom-up approach to prepare a variety of nanocomposites [74]. The synthesis mechanism is described by its name, which involves the process of converting a colloidal suspension into a gel [75]. This process is completed through five steps: hydrolysis, polycondensation, aging, and drying, followed by thermal decomposition [74]. The sol–gel technique has several advantages; it is very effective at obtaining nanocomposites with large specific surface area, high porosity, high quality, and well-mixed multi-component materials [76].

5.3. Chemical Precipitation Method

The chemical precipitation method is commonly referred to as wet precipitation or aqueous precipitation. Chemical precipitation turns a liquid into a solid either by making the liquid insoluble or making it extremely saturated. The process involves the addition of chemical agents, with pH adjustment, and then the precipitates and solution are separated. As compared with other methods of preparation, the precipitation method is the most useful since it allows for the production of a sizable quantity of materials at a reasonable cost without the use of organic solvents [77].

5.4. Solid-Phase Method

The solid-phase method is the most straightforward and low-cost technique, as it is free of organic solvents. The solid-state reaction route is one of the most widely used methods for preparing crystalline solids [78] and involves the decomposition of solid reagents at very high temperatures to produce crystalline solids and gases, such as NH3, NO2, CO2, and H2O, depending on the precursor powder. Furthermore, there are several benefits associated with choosing this method, such as, for example, the controllable adjustable reaction conditions, ease of use, high yield, and simple apparatus needed. The powder produced by this method has a large particle size with poor uniformity as a result of particle agglomeration and aggregation [79].

5.5. Sonochemical Method

The sonochemical method is a well-recognized synthesis method that applies powerful ultrasonic radiation from 20 to 10 MHz to a precursor to obtain nanomaterials for the preparation, insertion, or deposition of nanomaterials on mesoporous materials, ceramics, or polymers. It offers a simple route for fabricating nanomaterials that is inexpensive and can control the morphologies of nanomaterials under adjustable reaction conditions. The sonochemical method is based on cavitation phenomena, i.e., tiny acoustic bubbles are formed, then grow, and then collapse in liquid [25,80,81].

6. Types of Pollutions

Pollution is a major issue confronting international industries and endangering the lives of people. Pollutants are being released into the land, water (i.e., surface and ground waters), and air at higher rates because of industrialization, which largely occurred during the previous century.

6.1. Heavy Metals

Heavy metals are characterized as metals with relatively high densities, high atomic numbers, and high atomic weights [82]. Heavy metals have a negative effect on the environment because of their extreme toxicity, even if their concentration is very low [83,84]. Heavy metals, e.g., arsenic (As), cadmium (Cd), chromium (Cr), lead (Pb), and mercury (Hg), are present in the environment as a consequence of manufacturing processing and the Industrial Revolution [51,85]. Heavy metals can change to hazardous forms such as cadmium ion (Cd(II)) and lead ion (Pb(II)), which are highly toxic as compared with metal atoms [86]. Heavy metals are carcinogenic, can cause lung and kidney damage and neurological disorders, and can impact maternal reproductive health, causing fetal toxicity. Conventional methods for the removal of heavy metals, e.g., chemical precipitation, membrane filtration, ion exchange, and adsorption, are not effective, since the toxic species are still present [51]. The photocatalytic reduction of heavy metals is a promising strategy, as it converts the metals into less toxic forms; for instance, hexavalent chromium ions Cr(VI) can be reduced to a less toxic trivalent state, Cr(III), which is easily precipitated as hydroxides and is less poisonous and less mobile [87]. Spanu et al. fabricated hematite photoanodes α-Fe2O3 for the photoelectrocatalytic oxidation of As(III) to As(V) [88]. It was found that within 30 min 30% of the initial As(III) concentration was oxidized [88]. Raez et al. studied the photocatalytic performance of the photocatalytic TiO2 in the photoelectrocatalytic oxidation of As(III) to As(V) [89]. The photocatalytic TiO2 used zero-valent iron nanoparticles (nZVI) to enhance the photocatalytic performance [89]. Salmanvandi et al. applied a bentonite-supported Zn oxide nanoparticle (ZnO/BT) photocatalyst in the photoreduction and removal of Cd(II) to non-toxic Cd(0) under exposure to UV light [90]. The photoreduction efficiency of Cd(II) was 79.05% [90]. Abbasi et al. prepared BT/ZnO and BT/TiO2 photocatalysts to remove Cd(II) [91]. Murruni et al. investigated the photoreduction of Pb(II) using the synthesized photocatalysis TiO2 [92]. Interesting work was conducted by Kanakaraju et al. [93]. Multifunctional TiO2/Alg/FeNPs beads have been applied in the removal of heavy metal mixtures, i.e., Cr(III), Cu(II), and Pb(II) ions [93]. The removal efficiency for all three ions was >98.4% after 72 min of UV light exposure [93]. A mesoporous CuO/ZnO S-scheme heterojunction photocatalyst was developed by Mohamed et al. for the photocatalytic reduction and removal of Hg(II) ions [94]. The CuO/ZnO photocatalyst showed an excellent photoreduction/removal efficiency of Hg(II). The efficiency reached 100% within one hour [94]. Spanu et al. constructed Au-decorated TiO2 nanotubes for the photocatalytic reduction and scavenging of Hg(II) [95]. The photocatalytic reduction and scavenging of Hg(II) reached 90% within 24 h [95].

6.2. Organic Dyes

Organic dyes are common environmental pollutants because of their widespread use in numerous industries, such as, for example, textiles, leather electroplating, and tanneries [46,96]. The chemical structure of organic dyes is used to categorize them, as well as their color source and fiber type; dyes can be classified as anionic, cationic, acidic, or basic. In addition, the ability of dyes to absorb light in the visible spectrum is one of their characteristics [97]. Congo red (CR), methylene blue (MB), methyl orange (MO), and rhodamine B (RhB) are examples of common textile dyes. Textile dyes have an adverse impact on human health in various ways, such as, for example, skin irritation and harm to the respiratory system. They can be toxic, carcinogenic, mutagenic, and disruptive to blood formation. Moreover, dyes have negative environmental effects. Dyes are water-soluble organic molecules, and when these dyes are released into an aquatic environment the change in the esthetic quality of the water can lead to reduced sunlight transmission, increased chemical (COD) and biochemical (BOD) oxygen demand, and inhibited plant growth, i.e., reduced photosynthesis. Furthermore, textile dyes can bioaccumulate in an aquatic environment, increasing their toxicity [98,99,100]. Compared to other chemical techniques, advanced oxidation processes (AOPs) are considered promising techniques for treating dye-contaminated wastewater [16]. Previous research showed that the efficiency of AOPs in the removal of COD reached 90% compared to 60% efficiency of the chemical method. In addition, 96% of colored compounds can be removed by AOPs, while conventional ferrous sulfate treatment removes only 49% of colored compounds [16,101,102,103]. A number of experimental parameters have a significant impact on a dye’s photocatalytic degradation, such as the dye’s initial concentration, pH, and catalyst dosage [92]. Ali et al. synthesized a cobalt ferrite (CoFe2O4) catalyst for the photocatalytic degradation of CR dye [104]. They reported that 91% of the CR dye was photodegraded after 90 min of light exposure [104]. Pinna and co-workers achieved the photodegradation of MB dye under UV light radiation using biochar nanoparticles decorated with TiO2 nanotube arrays (BC-TiO2 NTS) [105]. Similar to nanocomposites, Lu et al. applied photocatalyst TiO2/biochar for the photodegradation of MO dye [106]. Chai and co-workers developed phosphorus-doped g-C3N4 to improve the efficiency of the photocatalytic performance of RhB dye [107]. After 30 min of visible-light irradiation, the efficiency of the photodegradation of RB dye reached 95% [107].

6.3. Pesticides and Herbicides

Pesticides are a class of species that have a special function, i.e., to kill pests or build resistance to them, and they include fungicides, rodenticides, herbicides, insecticides, nematicides, rodenticides, and garden chemicals [108]. Pesticides take up a significant amount of space in terms of chemical composition such as organic compounds, metal inorganic, and natural and synthetic pyrethroids synthesized [108]. The necessity of using pesticides has grown because of growing populations. They have some benefits, such as economic benefits and the preservation of agricultural crops [109]. As a result, pesticides are widely used in agriculture, which has led to the bioaccumulation of pesticides in the food chain, human bodies, and the aquatic environment. In contrast to all previous benefits, pesticide use can harm the nervous and reproductive systems and can cause cancer and fetal abnormalities [110,111,112]. Photodegradation of pesticides has been reported in the literature [108,113].

Herbicides control weeds; they are applied to protect agricultural crops from broad-leaf weeds and unwanted grass [114]. The increase in the consumption of herbicides has consequently increased agricultural productivity and intensification [114]. Atrazine is the most common herbicide and is widely used [115]. However, exposure to these compounds causes major problems for environmental and public health, such as stomach problems and skin diseases [116]. Therefore, the removal of these compounds is necessary, and the photocatalytic degradation of herbicides is a promising method for the removal of herbicides [117,118,119].

6.4. Phenolic Compounds

Phenolic compounds are commonly thought to be among the most significant organic pollutants released into the environment from different resources, either naturally or as a result of anthropogenic activities [120,121]. Phenol is a naturally occurring substance derived from dead animals and plants that degrade in water. Phenol is discharged as a result of anthropogenic activities, such as those occurring in petrochemical industries, chemical production, and the agriculture sector [122]. Phenolic compounds and their derivatives show variation in molecular diversity and can be classified by their source and the number of carbon atoms [120]. Exposure to phenolic compounds has several negative effects, such as muscle weakness, tremors, respiratory arrest, and cardiovascular tissue irrigation in the eyes and skin, as well as damage to the liver and kidney [123,124]. Therefore, many studies on the photodegradation of phenolic compounds and their substituent compounds have been published [125,126,127].

6.5. Pharmaceutical Pollutants

Pharmaceutical compounds include personal care products, cosmetics, drugs, and antibiotics. Antibiotics are commonly employed to kill and inhibit the growth of target microorganisms in humans and veterinary medicine. The disadvantages of antibiotics include their adverse effects on aquatic life and human health [128,129]. Antibiotics are toxic and nondegradable by animals. As a consequence, antibiotics have been found in a range of aquatic environments, such as wastewater, surface water, groundwater, and potable water. Antibiotics can be absorbed in the human body and can cause serious problems such as altered metabolic activity and side effects (permanent or long-lasting) [15,130,131]. Metal oxides photocatalysts, such as TiO2, ZnO, Bi2WO6, WO3, and Fe2O3, have been applied in the photodegradation of pharmaceutical pollutants [132].

7. Nanostructure Semiconductor Heterojunction Photocatalysts

Nanostructure semiconductors, including binary and ternary, have been widely investigated in environmental photocatalysts and have various morphologies and properties. Different types of heterojunctions have been designed, such as metal oxides and metal chalcogenides. In this review, we report on recent nanostructure semiconductor heterojunction photocatalysts for the purpose of environmental remediation.

7.1. Bismuth-Based Semiconductor Photocatalysts

Bismuth-based (bi-based) photocatalysts have attracted significant scientific interest because of their exceptional physical and chemical features, visible light absorption capability, and suitable energy band. In addition, bismuth compounds are non-toxic [133,134]. The photocatalytic activities of bismuth-based semiconductor materials are superior as compared with those of traditional TiO2 and ZnO semiconductors [134,135]. Since 2021, the number of studies on bi-based photocatalysts has grown to 2388 (ScienceDirect database). Numerous bi-based semiconductors have been constructed, such as bismuth-based oxides, sulfides, and multi-component oxides and oxyhalides, such as Bi2O3, Bi2S3, Bi2MO6 (M = Cr, W), BiVO4, BiPO4, and BiOX (X = Cl, Br, and I) [133,134]. The majority of bi-based semiconductors are visible-light active because of their electronic structure and band gap, i.e., less than 3.0 eV. In addition, bi-based multi-component oxides show excellent characteristics such as size, porosity, and form, with a large surface area as compared with regular bi-based oxides and sulfides [136]. Numerous uses of bi-based semiconductor photocatalysts have been investigated, such as CO2 reduction, photodegradation of organic pollutants, photoreduction of heavy metals, and hydrogen production [133,135]. To enhance the photocatalytic activities of bi-based semiconductor photocatalysts, numerous studies have been conducted, including the construction of heterojunctions with or without metal [133,134]. The benefits of these strategies include promoting the migration of photogenerated charge carriers, effectively reducing the recombination of photogenerated electron–hole pairs, and shortening the band gaps of photocatalysts [133,134]. Type II is the most prevalent type of traditional bismuth-based heterojunction. Z-scheme bismuth-based heterojunctions are the most useful structures with which to study photocatalytic performance [133,134]. Table 1 summarizes a list of bi-based semiconductor photocatalysts.

Table 1.

List of bi-based semiconductor heterojunction photocatalysts.

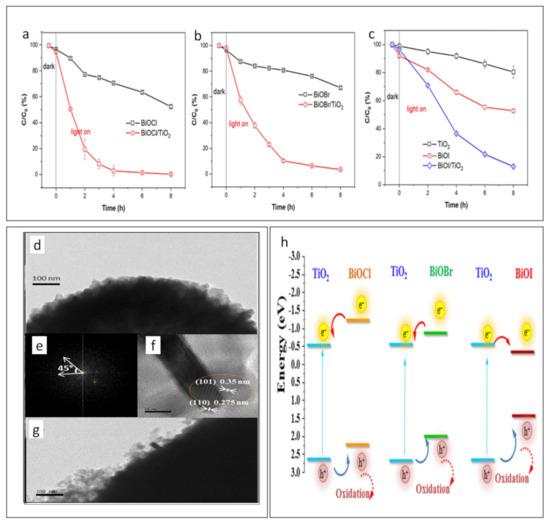

Yan et al. synthesized Bi2O2CO3/BiOBr (BOC/BiOBr) Z-scheme heterojunction photocatalysts using a hydrothermal method for the purpose of photocatalytic removal of ciprofloxacin (CIP) and tetracycline (TC). The removal efficiency for CIP and TC reached 88.9% and 94.8%, respectively, after 120 min of visible light exposure [152]. More recent research was conducted by Liu et al. to develop the p–n heterojunction BiOX/TiO2, i.e., BiOX (X = Cl, Br, and I), for photocatalytic decomposition of perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) [153]. It was found that PFOA was completely degraded in the case of BiOBr and BiOCl. The kinetics of the photocatalytic degradation of PFOA is displayed in Figure 3a–c. The characteristics of different halides impact semiconductor photocatalysts [153]. In Figure 3d–g, the TEM images show BiOCl nanostructures. BiOCl/TiO2 and BiOBr/TiO2 are smaller nanorods than BiOl/TiO2, and, because their small sizes, charge carriers can be easily transferred to the surface for redox reactions [153]. In addition, photoinduced electrons can move from BiOX to TiO2 in the [001] direction, which is perpendicular to the [110] facet; this is facilitated by the inner electric field in BiOX.

Figure 3.

The kinetics of the photocatalytic degradation of PFOA by (a) BiOCl/TiO2, (b) BiOBr/TiO2, and (c) BiOl/TiO2; (d–g) TEM images of BiOCl, (h) the band structures of BiOX/TiO2 heterostructures (reprinted with permission, copyright Elsevier (2022)) [153]).

It can be seen in Figure 3h that the VB of BiOI has a lower level than the VB of TiO2 and the CB of BiOI has a higher level than the CB of TiO2. Therefore, photogenerated holes and electrons flow from TiO2 to BiOI, and, therefore, photogenerated holes and electrons accumulate in the VB and CB of BiOI, leading to a high recombination rate of charge carriers in BiOI [153]. Due to the spatial separation of carriers in each component to moderate recombination, BiOCl(Br)/TiO2 outperforms BiOI/TiO2 in terms of photocatalytic degradation of PFOA [153].

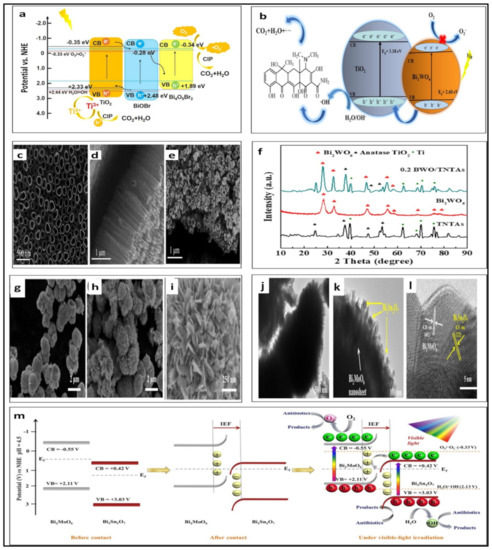

Lou et al. synthesized BiOBr/MgBTC (BTC = 1,3,5-benzenetricarboxylate) photocatalysts with Mott–Schottky heterojunctions using a solvothermal reaction method for visible-light photodegradation of RhB [154]. The role of the Mott–Schottky heterojunctions was significant in the recombination of the photoinduced carriers and improved the separation of photoinduced electron–hole pairs [154]. TiO2@BiOBr/Bi4O5Br2 (TBB) was fabricated for the first time by Yang with a degradation efficiency of 95% for CIP in less than 50 min [154]. TBB has hollow structures with pore sizes of 17.89 nm [154]. The new type-II Z-scheme tandem heterojunction (see Figure 4a) shows the proposed photocatalytic mechanism of TiO2@BiOBr/Bi4O5Br2 (TBB) to photodegrade CIP [154]. It can be seen that BiOBr works as a bridge to join TiO2 and Bi4O5Br2 [154]. These results should encourage researchers to prepare high-efficiency heterojunctions with hollow structures [155].

Figure 4.

(a) Proposed photocatalytic mechanism for the photodegradation of CIP (reprinted with permission, copyright Elsevier (2022)) [155]; (b) the mechanism of photodegradation of TC under the visible light by Bi2WO6/TiO2; (c–e) SEM images: (c) top view of TiO2, (d) side view of TiO2, (c) 0.2 Bi2WO6/TiO2; (f) the PXRD pattens of TiO2, Bi2WO6 and Bi2WO6/TiO2 (reprinted with permission, copyright Elsevier (2022)) [156]); (g–i) SEM image: (g) of pristine Bi2MoO6; (h,i) SEM images of Bi2Sn2O7/Bi2MoO6-6%; (j,k) TEM images of Bi2Sn2O7/Bi2MoO6-6%; (l) HRTEM image Bi2Sn2O7/Bi2MoO6-6%; (m) the mechanism of the Bi2Sn2O7/Bi2MoO6 S-scheme heterojunction under visible light (reprinted with permission, copyright Elsevier (2022)) [157]).

Bismuth tungstate (Bi2WO6) is another bismuth-based semiconductor photocatalyst, which has an excellent photonic response because of its unique outer electron configuration: narrow band gap, i.e., ∼2.7 eV; visible-light active; large specific surface area; and non-toxic Bi2WO6 made of alternating (Bi2O2)2+ layers and perovskite such as (WO4)2− sheets [156,158]. Because of these advantages, researchers have synthesized semiconductor photocatalysts with Bi2WO6 [156]. Type II heterostructures have been developed with Bi2WO6/TiO2 for photodegradation of TC and RhB under visible light, with a removal efficiency greater than 92% in 180 min and 97% in 120 min, respectively (see Figure 4b: The mechanism of photodegradation of TC under the visible light) [156]. Figure 4c–e display the SEM images of the nanotube arrays of TiO2 and Bi2WO6 dispersed on a TiO2 nanotube, with the PXRD patterns of TiO2, Bi2WO6, and Bi2WO6/TiO2 (see Figure 4f). S-scheme heterojunctions have been constructed consisting of n-semiconductor Bi2Sn2O7/Bi2MoO6, with a removal efficiency of almost 100% for TC in 100 min [157]. It can be seen in Figure 4g–i that the SEM images show that Bi2MoO6 has flowerlike microspheres and Bi2Sn2O7 NPs are attached to the surface of the Bi2MoO6 microspheres [157]. Moreover, the TEM images are present on the hierarchical heterostructure of Bi2Sn2O7/Bi2MoO6 (see Figure 4j–l) [157]. The mechanism of the Bi2Sn2O7/Bi2MoO6 S-scheme heterojunction under visible light is explained in Figure 4m [157].

7.2. Metal Chalcogenide-Based Semiconductor Photocatalysts

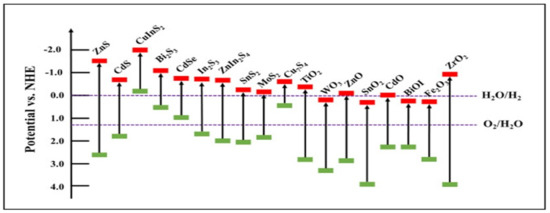

Metal chalcogenides are a large family of layered materials, which have been constructed in enormous structures such as binary chalcogenides (CdS, ZnS, MoS2, In2S3, ZnSe, CdSe, and PbSe), ternary chalcogenides (AgInS2, CuGaS2, CdIn2S4, ZnIn2S4, CdMoS4, and CuInSe2), and quaternary chalcogenides (SrScCuSe3, SrScCuTe3, and BaScCuSe3) [159,160,161]. Metal chalcogenides are promising candidates in photocatalytic applications for numerous reasons; for example, they are excellent charge carriers and have low effective mass, long-term stability in aqueous and air, conductivity, empty valence band, anti-oxidation, and quantum size effect properties [159,160,161]. The structure and electronic properties of chalcogenides can be modified. The potential energy of the valence band and the conduction band as they approach nano-dimensions, and the morphologies and sizes of particles, can be adjusted. For photocatalysts, metal sulfides are more favorable than metal oxides [159,160,161]. Metal cations in metal sulfide semiconductor catalysts typically have electron configurations of d0, d5, and d10. The VB consists of sulfur 3p orbitals. The p orbital in the third level of sulfur is more negative than the p orbital In the second level of oxygen, i.e., 3p and 2p. Therefore, the position of the valence band of the metal sulfide is higher than that of the metal oxide [159,160,161]. The CB is composed of d and sp orbitals. The metal sulfides show a negative conduction band that is due to metal sulfides’ own smaller band gaps as compared with metal oxides, as seen in Figure 5 [159,160,161]. Due to the structure and electronic properties of chalcogenides such as metal sulfides, they have been applied in other applications—for example, energy storage and electrochemical sensing [162,163].

Figure 5.

The band structure of common metal sulfide and metal oxide semiconductors (reprinted with permission, copyright Elsevier (2021)) [161].

Metal sulfides, i.e., transition metal sulfides and molybdenum disulfide (MoS2), have been investigated to enhance other semiconductor photocatalysts in environmental remediation, such as TiO2 [164,165,166]. Table 2 presents a list of MoS2-based semiconductor photocatalysts.

Table 2.

List of MoS2-based semiconductor photocatalysts.

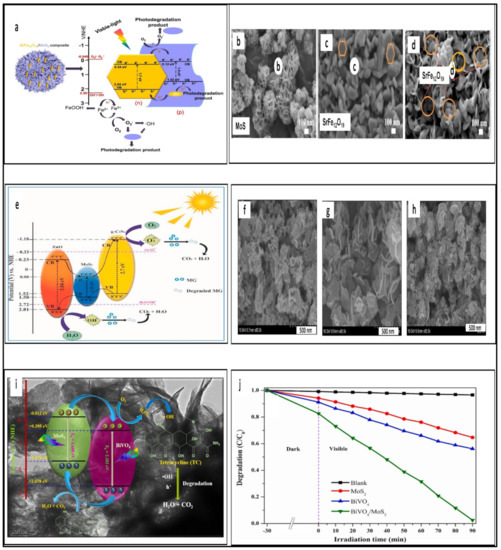

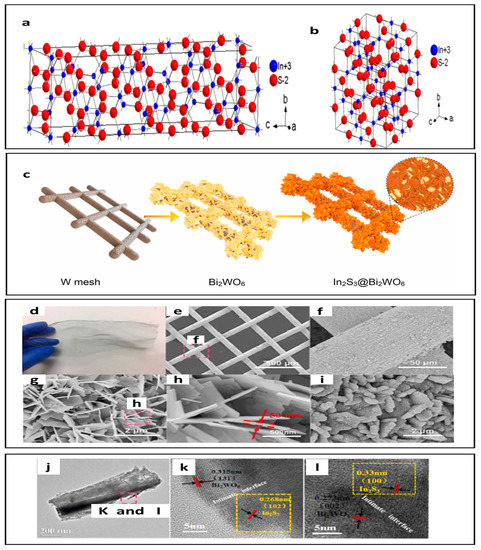

Shawky et al. developed photocatalysts containing MoS2/TiO2 heterojunctions for photoreduction of Cr(VI) [174]. The efficiency conversion of Cr6+ to Cr3+ was 96% [174]. In addition, researchers have combined MoS2 with a wide range of materials such as MoS2/ZnO, MoS2/FeOCl, and MoS2/SrFe12O19 for environmental remediation [175,176]. Under visible light, the SrFe12O19/MoS2 heterojunction showed MB and MO degradation as seen in Figure 6a [177]. The SrFe12O19/MoS2 heterojunction showed an MB degradation rate of 97% [177]. This rate was almost twice that of pure MoS2 [177]. Zhao et al. utilized the hydrothermal method to synthesize unique flower-like structure SrFe12O19/MoS2 p–n heterojunctions to achieve a photocatalytic degradation rate for methylene blue with 97% removal efficiency (see Figure 6a) [177]. Figure 6 shows the SEM images of (b) MoS2 with flowerlike microspheres, (c) Hexagonal structure of SrFe12O19, and (d) SrFe12O19/MoS2 hexagonal nanoplate composite [177]. The advantages of that heterojunction include rich active sites in 2D MoS2 nanosheets that facilitate catalytic reactions and the interface region of the p–n heterojunction, which decreases the recombination rate of the photogenerated charge carriers [177]. Moreover, a strategy to overcome photocatalysts efficiency is to develop a ternary system using Z-scheme heterojunctions. MoS2/g-C3N4/ZnO ternary photocatalysts have been fabricated to degrade malachite green dye, as seen in Figure 6e [178]. Effective charge carrier transport and separation were promoted using MoS2/g-C3N4/ZnO. MoS2 nanosheets increased the photocatalytic efficiency and lengthened the longevity of charge carriers by accelerating the charge transfer at the ZnO/g-C3N4 interface. It was found that the efficiency of a ternary system using Z-scheme heterojunctions was 97% within 60 min [178]. As previously mentioned, the benefit of bismuth-based semiconductor photocatalysts is that they would be superior in the case of coupling Bi compounds with a metal chalcogenide-based semiconductor. Koutavarapu at el. investigated a binary nanocomposite; a bismuth-based semiconductor photocatalyst was coupled with a lower band gap semiconductor photocatalyst, MoS2 [179]. MoS2 with a nanoflake structure was attached over the BiVO4 nanosheets, as seen in Figure 6f–h (the SEM images) [179]. The modification of the surface and the band gap enhanced the photodegradation performance for TC to 97.46% within 90 min. The proposed photocatalytic degradation pathway of TC and the photocatalytic removal curve of TC are presented in Figure 6i,j, respectively [179]. In2S3/Bi2WO6 is another example of a heterojunction. In2S3 is classified as a representative of Group III–VI sulfides. It possesses three polymorphic crystalline forms, which are α-In2S3 (defect cubic), β-In2S3 (defect spinel), and γ-In2S3 (layered structure) [180]. β-In2S3 can be further classified into tetragonal or cubic phase, as shown in Figure 7a,b [181,182,183]. The β-In2S3 structure has strong photoconductive and photoluminescent characteristics, making it a strong option for photocatalytic applications [184,185]. Wang et al. applied In2S3/Bi2WO6 heterojunctions in the photodegradation of toluene. In2S3/Bi2WO6 efficiently removed 99.7% of toluene in 80 min [186]. A simple solvothermal method was used to prepare hierarchical In2S3/Bi2WO6 heterostructures on tungsten (W) mesh [186]. The preparation method is illustrated in Figure 7c. The characteristic feature of the heterostructures appeared in the SEM images, and in TEM images (Figure 7d–l) the nanoflake of In2S3 is observed. The heterostructures with large porosity and surface area compare to pure In2S3 and Bi2WO6 [186]. The interfaces between In2S3 and Bi2WO6 are formed that facilitate the rapid migration of photogenerated carriers. All those advantages have a positive impact on the photodegradation of TC [186].

Figure 6.

(a) The proposed photocatalytic degradation pathway of MB and MO, SEM images (b) MoS2, (c) SrFe12O19, (d) SrFe12O19/MoS2 (reprinted with permission, copyright Elsevier (2022)) [177]). (e) The proposed photocatalytic degradation pathway of MG (reprinted with permission, copyright Elsevier (2022)) [178]). SEM images of (f) BiVO4 nanosheets, (g) MoS2 nanoflakes, and (h) BiVO4/MoS2 nanocomposite; (i) the proposed photocatalytic degradation pathway of TC, (j) the photocatalytic removal curve of TC. (reprinted with permission, copyright Elsevier (2022)) [179]).

Figure 7.

Crystal structures of β-In2S3: (a) tetragonal phase; (b) cubic phase (reprinted with permission from [181] Copyright 2018 American Chemical Society). (c) the schematic illustration of synthesis In2S3@Bi2WO6 crystals on W mesh; (d) digital picture of pristine W mesh; (e–i) the SEM images of (e) Bi2WO6/W mesh (low-magnification); (f) enlarged SEM image of the part marked in (e); (g,h) with increased resolution of the SEM images of Bi2WO6 nanosheets; (i) SEM image of In2S3 nanoflakes anchored Bi2WO6; (j) TEM images of In2S3@Bi2WO6 (k,l) the HRTEM images of marked part in (j) (reprinted with permission, copyright Elsevier (2022)) [186].

Zinc indium sulfide (ZnIn2S4) is a remarkable AB2X4 family ternary semiconductor that has recently attracted attention [187,188]. Due to its characteristic features, it has attracted significant interdisciplinary interest as a visible-light-response photocatalyst in the domains of energy and the environment. Its tunable band gap, which ranges from 2.06 to 2.85 eV, is what provokes the visible light region’s strong responses [187,188]. Additionally, it exhibits higher physicochemical stability than the well-known cadmium sulfide (CdS), which results in a significant amount of durability during the photocatalytic reaction [187,188]. In addition, it has higher application potential in the field of environmental remediation because it is less poisonous than other metal sulfides such as CdS, NiS, and Sb2S3, and it is extremely straightforward to create because of the availability of its raw components and basic chemical composition [187,188]. Table 3 presents a list of ZnIn2S4-based semiconductor photocatalysts.

Table 3.

A list of ZnIn2S4-based semiconductor heterojunction photocatalysts.

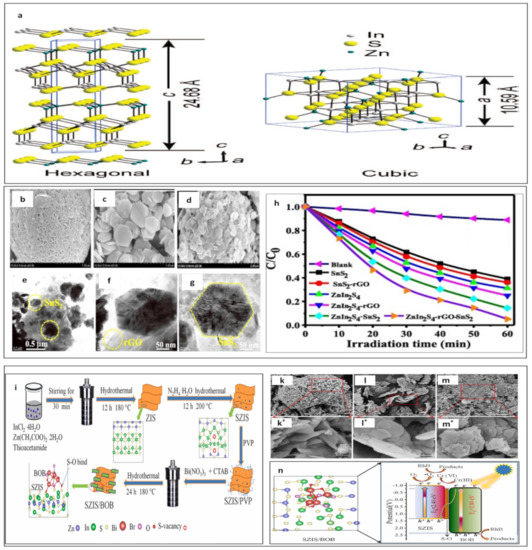

There are two unique types of ZnIn2S4 crystal structures: hexagonal and cubic structures, as reported in Figure 8a [197]. In the field of photocatalysis, hexagonal structures have received more attention as compared with the few reports on cubic structures [187,188,198]. Raja et al. reported on a ZnIn2S4/rGO/SnS2 heterostructure photocatalyst for TC degradation and H2 generation [199]. A heterostructure photocatalyst was synthesized using a one-step hydrothermal method [199]. This ternary nanocomposite had a synergetic effect because of its heterostructure, and the hexagonal and layered structure of materials, as well as thermal properties and specific oxidative of SnS2 [199]. Moreover, reduced graphene oxide (rGO) has unique properties, i.e., excellent light transport, rapid movement rate of charge carriers, and large specific surface area. The morphologies of a ZnIn2S4/rGO/SnS2 heterostructure present in Figure 8b–g [199]. These points all have positive impacts on photocatalytic performance with an efficiency of 96.5% during 60 min of exposure to visible light [199]. Figure 8h shows the photocatalytic degradation of TC under different catalysts [199]. He et al. constructed a ZnIn2S4/BiOBr Z-scheme heterostructure (see Figure 8i) for removal of Cr(VI) and organic pollutants, i.e., RhB [200]. The photocatalytic performance of ZnIn2S4/BiOBr within 100 min was 95.2% and 97.8% for RhB and Cr(VI), respectively [200]. Figure 8k–l displays SEM images of ZnIn2S4, BiOBr, and ZnIn2S4/BiOBr-10 heterojunction. The methodologies of enhancing photocatalytic activities are based on an abundance of sulfur vacancies that facilitate the covalent bond S-O at the interface in the ZnIn2S4 and BiOBr catalysts [200]. Therefore, interfacial charge transfer is encouraged via a direct Z-scheme charge transfer mechanism, as shown in Figure 8n [200].

Figure 8.

The crystal structures of ZnIn2S4 (reprinted with permission from [197] Copyright (2007) American Chemical Society). (a) ZnIn2S4 crystal structures; (b–d) SEM images of ZnIn2S4, SnS2 and ZnIn2S4-rGO- SnS2; (e–g) HRTEM images of ZnIn2S4-rGO- SnS2; (h) the photocatalytic degradation of TC under different catalysts (reprinted with permission, copyright Elsevier (2022) [199]). (i) Schematic description of the preparing process of ZnIn2S4/BiOBr heterojunction; SEM images of: (k, k*) ZnIn2S4, (l, l*) BiOBr, and (m, m*) ZnIn2S4/BiOBr-10 heterojunction; (n) schematic illustration of the proposed photoelectron generation and transport routes in the ZnIn2S4/BiOBr heterostructure as well as the photocatalytic reaction mechanism for reduction of Cr(VI) and RhB degradation and under Irradiation with visible light (reprinted with permission, copyright Elsevier (2022)) [200].

8. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Organic and inorganic water pollutants are a global threat to aquatic life, human health, crops, and the economy. Water pollutants are non-biodegradable, toxic molecules that are difficult to handle; thus, effective, non-traditional methods for removing these pollutants are required. Photocatalytic removal is one method with great potential. Semiconductor materials have a strong environmental remediation ability because of their electric structure and optical properties; they can serve as photocatalysts because of their ability to absorb light and produce free radicals. This review has explored the fundamental principles of semiconductor photocatalysts, including associated challenges and strategies to overcome such challenges. Photocatalysts are excited by light, resulting in photogenerated charge carriers (electrons and holes are photogenerated as the electrons move from the valence band to the conducting band, leaving free holes). The excitement of electrons depends on the band gap energies (Eg) of photocatalysts. Photogenerated electrons and holes react either with oxygen or water to produce reactive oxygen species (ROS) such as superoxide radicals (O2−) and hydroxyl radicals (•OH). ROS can photodegrade organic pollutants; simultaneously, the target chemical species can be reduced or oxidized by the charge carriers, transforming them into a harmless species. Numerous investigations into environmental remediation utilizing photocatalysts have been conducted. However, there are two major challenges to the photolysis process. Due to the level of band gap energy, some semiconductors are limited by poor visible-light absorption and the rapid recombination of photogenerated chargers that carry electrons and holes (charge carrier lifetimes). Therefore, further studies must be conducted to enhance the photocatalytic performance of semiconductors for pollutant removal. One of the most effective techniques used for the removal of various water contaminants is the development of semiconductor heterojunctions. It has been used for several types of organic pollutants, such as organic dyes (MB, MO, RhB), antibiotics (CIP, TC), and heavy metals (Cr(VI)). Various types of heterojunctions (type II, Z-scheme, and S-scheme) have been fabricated. This work has assessed previous research on the most promising photocatalysts such as bismuth-based and metal chalcogenides-based photocatalysts, including MoS2, In2S3, and ZnIn2S4, concerning the morphologies of semiconductor photocatalysts and band gap modification.

For bismuth-based photocatalysts, several successful tactics have been discovered to improve photocatalysts’ activities, such as the synthesizing of the hollow mesoporous Z-scheme heterojunction. Additionally, coupling a semiconductor such as TiO2 with an Aurivillius compound such as Bi2WO6 type II increased the absorption of visible light and inhibited charge recombination [117]. Hierarchical 0D/3D S-scheme heterostructures possess a large surface area with plenty of active sites that enhance photocatalyst performance and the efficiency of charge carrier separation, maintaining optimal redox ability [118]. Metal chalcogenides such as MoS2, In2S3, and ZnIn2S4 are promising candidates for photocatalytic applications. A similar approach has been investigated to improve photocatalytic degradation by preparing semiconductor heterojunction with a large surface area and interfacial charge transfer. The morphologies of photocatalysts play an important role in photocatalysts efficiency and the selection of suitable crystal structures for photocatalytic applications [138,147]. Furthermore, the fabrication of a ternary photocatalytic system had a significant impact on decelerating the recombination of charge carriers [160].

However, although extensive research has been conducted on the removal of hazards using semiconductor photocatalysts such as bismuth-based and metal chalcogenides, there are still many challenges to be overcome. According to current knowledge regarding the limitations of photocatalytic technology in hazard removal, the majority of investigations are based on bench-scale operations in a laboratory setting. Thus, more studies including large-scale simulations are required. The lack of scale-up experiments is the result of a number of issues, including the design of a suitable photoreactor. The photoreactor’s geometrical shapes and morphologies are fundamental to controlling a number of parameters, such as any pollutants on the surface of the catalyst, flow patterns, and uniform distribution of light. Photoreactors also reduce light scattering and do not consume a lot of energy. Regarding the physiochemical properties of catalysts, the synthesis of larger-scale catalysts would be stable for a long time. In addition, in comparison to pure water solutions that contain a single pollutant, a real wastewater sample would contain a mixture of pollutants, such as organic, inorganic, and other dissolved species that could hinder the photocatalytic process; these species may also work as radical scavengers. The low concentration of pollutants in real wastewater, which is lower than the detection limit. In a laboratory setting, the photocatalytic experiment is conducted at the concentration of mg L−1 scale. Thus, catalysts should have large numbers of active sites, i.e., large surface areas. Moreover, the cost of scale-up experiments is one significant challenge that has not been addressed yet because of the lack of information in the literature.

Regarding chemical characteristics in the future experiments, effective heterostructures of photocatalysts with high surface areas, such as Z-scheme or S-scheme photocatalysts, must be developed as heterostructures can impact photogenerated charge carriers and their lifetime. The modification of nanostructure photocatalysts is undertaken to produce photocatalysts with high surface areas, flower shapes, nanoroads, and nanoflakes. More emphasis should be placed on the development of facile synthesis routes of photocatalysts that do not require extreme conditions. The photocatalytic removal of hazards should be conducted using real wastewater; therefore, it would be useful to simulate photocatalytic performance before conducting experiments. Additional environmental parameters that impact photocatalytic degradation must be further explored to construct a perfect, cost-effective photoreactor with high photocatalytic efficiency. Regarding the toxicity of nanomaterials, it is crucial to thoroughly investigate their long-term toxicity before using them in environmental applications.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Yu, C.; Chen, X.; Li, N.; Zhang, Y.; Li, S.; Chen, J.; Yao, L.; Lin, K.; Lai, Y.; Deng, X. Ag3PO4-based photocatalysts and their application in organic-polluted wastewater treatment. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 18423–18439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdullah, F.H.; Bakar, N.H.H.A.; Bakar, M.A. Current advancements on the fabrication, modification, and industrial application of zinc oxide as photocatalyst in the removal of organic and inorganic contaminants in aquatic systems. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 424, 127416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahmoudi, F.; Saravanakumar, K.; Maheskumar, V.; Njaramba, L.K.; Yoon, Y.; Park, C.M. Application of perovskite oxides and their composites for degrading organic pollutants from wastewater using advanced oxidation processes: Review of the recent progress. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 436, 129074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, Y.; Ma, J.; Chen, Y.; Qian, Y.; Xu, B.; Chu, W.; An, D. Recent progress of silver-containing photocatalysts for water disinfection under visible light irradiation: A review. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 804, 150024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Sharabati, M.; Abokwiek, R.; Al-Othman, A.; Tawalbeh, M.; Karaman, C.; Orooji, Y.; Karimi, F. Biodegradable polymers and their nano-composites for the removal of endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) from wastewater: A review. Environ. Res. 2021, 202, 111694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patidar, R.; Srivastava, V.C. Evaluation of the sono-assisted photolysis method for the mineralization of toxic pollutants. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2021, 258, 117903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, R.; Wang, J.; Bi, Z.; Chen, X.; Hu, X.; Pan, W. Recent advances and perspectives of g–C3N4–based materials for photocatalytic dyes degradation. Chemosphere 2022, 295, 133834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivaraman, C.; Vijayalakshmi, S.; Leonard, E.; Sagadevan, S.; Jambulingam, R. Current Developments in the Effective Removal of Environmental Pollutants through Photocatalytic Degradation Using Nanomaterials. Catalysts 2022, 12, 544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, K.; Hu, L.; Li, L.; Zheng, Q.; Xin, Y.; Zhang, G. Recent advances in persulfate-based advanced oxidation processes for organic wastewater treatment. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2022, 33, 4461–4477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, D.; Yi, H.; Lai, C.; Liu, X.; Huo, X.; An, Z.; Li, L.; Fu, Y.; Li, B.; Zhang, M.; et al. Critical review of advanced oxidation processes in organic wastewater treatment. Chemosphere 2021, 275, 130104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sgroi, M.; Snyder, S.A.; Roccaro, P. Comparison of AOPs at pilot scale: Energy costs for micro-pollutants oxidation, disinfection by-products formation and pathogens inactivation. Chemosphere 2021, 273, 128527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeola, A.O.; Abiodun, B.A.; Adenuga, D.O.; Nomngongo, P.N. Adsorptive and photocatalytic remediation of hazardous organic chemical pollutants in aqueous medium: A review. J. Contam. Hydrol. 2022, 248, 104019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, G.; Han, H.; Wang, Y.; Liu, S.; Zhao, J.; Meng, X.; Li, Z. Recent Advances of Photocatalytic Application in Water Treatment: A Review. Nanomater 2021, 11, 1804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wu, X.; Liu, J.; Zhai, Z.; Yang, Z.; Xia, J.; Deng, S.; Qu, X.; Zhang, H.; Wu, D.; et al. Mo-modified band structure and enhanced photocatalytic properties of tin oxide quantum dots for visible-light driven degradation of antibiotic contaminants. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 107091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Chen, Z.; Zhao, W.; Liu, C.; Qian, X.; Zhang, M.; Wei, G.; Khan, E.; Hau Ng, Y.; Sik Ok, Y. Recent advances in photodegradation of antibiotic residues in water. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 405, 126806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, M.; Muneer, M.; Haq, A.U.; Akram, N. Photocatalysis: An effective tool for photodegradation of dyes—A review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 293–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuerda-Correa, E.M.; Alexandre-Franco, M.F.; Fernández-González, C. Advanced Oxidation Processes for the Removal of Antibiotics from Water. An Overview. Water 2020, 12, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbari, M.Z.; Xu, Y.; Lu, Z.; Peng, L. Review of antibiotics treatment by advance oxidation processes. Environ. Adv. 2021, 5, 100111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brillas, E. A review on the photoelectro-Fenton process as efficient electrochemical advanced oxidation for wastewater remediation. Treatment with UV light, sunlight, and coupling with conventional and other photo-assisted advanced technologies. Chemosphere 2020, 250, 126198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, J.; Cho, K.-H.; Presser, V.; Su, X. Recent advances in wastewater treatment using semiconductor photocatalysts. Curr. Opin. Green Sustain. Chem. 2022, 36, 100644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahir, M.B.; Sohaib, M.; Sagir, M.; Rafique, M. Role of Nanotechnology in Photocatalysis. Ref. Modul. Mater. Sci. Mater. Eng. 2020, 1, 439–458. [Google Scholar]

- Chawla, H.; Chandra, A.; Ingole, P.P.; Garg, S. Recent advancements in enhancement of photocatalytic activity using bismuth-based metal oxides Bi2MO6 (M=W, Mo, Cr) for environmental remediation and clean energy production. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2021, 95, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, C.; Fang, W.; Yi, Q.; Zhang, J. A comprehensive review on reactive oxygen species (ROS) in advanced oxidation processes (AOPs). Chemosphere 2022, 308, 136205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz, C.; Segovia, M.; Valenzuela, M.L. Solid State Nanostructured Metal Oxides as Photocatalysts and Their Application in Pollutant Degradation: A Review. Photochem 2022, 2, 609–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terna, A.D.; Elemike, E.E.; Mbonu, J.I.; Osafile, O.E.; Ezeani, R.O. The future of semiconductors nanoparticles: Synthesis, properties and applications. Mater. Sci. Eng. B 2021, 272, 115363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Y.J.; Lee, D.J. Solid mediator Z-scheme heterojunction photocatalysis for pollutant oxidation in water: Principles and synthesis perspectives. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2021, 125, 88–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alahmadi, N.; Amin, M.S.; Mohamed, R.M. Facile synthesis of mesoporous Pt-doped, titania-silica nanocomposites as highly photoactive under visible light. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2020, 9, 14093–14102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alahmadi, N.; Amin, M.S.; Mohamed, R.M. Superficial visible-light-responsive Pt@ZnO nanorods photocatalysts for effective remediation of ciprofloxacin in water. J. Nanoparticle Res. 2020, 22, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Oliveira Pereira, L.; Marques Sales, I.; Pereira Zampiere, L.; Silveira Vieira, S.; Do Rosário Guimarães, I.; Magalhães, F. Preparation of magnetic photocatalysts from TiO2, activated carbon and iron nitrate for environmental remediation. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2019, 382, 111907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, S.; Ni, S.; Xu, X. A new approach to inducing Ti3+ in anatase TiO2 for efficient photocatalytic hydrogen production. Chin. J. Catal. 2018, 39, 510–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, A.K.; Roy George, D.; Jos Baby, N.; Reji, M.; Joseph, S. Solar dye degradation using TiO2 nanosheet based nanocomposite floating photocatalyst. Mater. Today Proc. 2021, 46, 2747–2751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goktas, S.; Goktas, A. A comparative study on recent progress in efficient ZnO based nanocomposite and heterojunction photocatalysts: A review. J. Alloys Compd. 2021, 863, 158734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajith, M.P.; Aswathi, M.; Priyadarshini, E.; Rajamani, P. Recent innovations of nanotechnology in water treatment: A comprehensive review. Bioresour. Technol. 2021, 342, 126000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarani, M.; Tosan, F.; Hasani, S.A.; Barani, M.; Adeli-Sardou, M.; Khosravani, M.; Niknam, S.; Jadidi Kouhbanani, M.A.; Beheshtkhoo, N. Study of in vitro cytotoxic performance of biosynthesized α-Bi2O3 NPs, Mn-doped and Zn-doped Bi2O3 NPs against MCF-7 and HUVEC cell lines. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2022, 19, 140–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradford, S.A.; Shen, C.; Kim, H.; Letcher, R.J.; Rinklebe, J.; Ok, Y.S.; Ma, L. Environmental applications and risks of nanomaterials: An introduction to CREST publications during 2018–2021. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 52, 3753–3762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, T.; Ali, I.; Naz, I.; Kayshar, M.S. Chapter 1—Appraisal of nanotechnology for sustainable environmental remediation. In Micro and Nano Technologies; Koduru, J.R., Karri, R.R., Mubarak, N.M., Bandala, E.R., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 3–31. ISBN 978-0-12-824547-7. [Google Scholar]

- Arshad, R.; Kiani, M.H.; Rahdar, A.; Sargazi, S.; Barani, M.; Shojaei, S.; Bilal, M.; Kumar, D.; Pandey, S. Nano-Based Theranostic Platforms for Breast Cancer: A Review of Latest Advancements. Bioengineering 2022, 9, 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafiq, M.; Anjum, S.; Hano, C.; Anjum, I.; Abbasi, B.H. An Overview of the Applications of Nanomaterials and Nanodevices in the Food Industry. Foods 2020, 9, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, S.; Sun, Q.; Gu, X.; Xu, Y.; Shen, J.; Zhu, D.; Chao, J.; Fan, C.; Wang, L. Two-dimensional nanomaterials for biosensing applications. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2019, 119, 115610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taghavi, S.M.; Momenpour, M.; Azarian, M.; Ahmadian, M.; Souri, F.; Taghavi, S.A.; Sadeghain, M.; Karchani, M. Effects of Nanoparticles on the Environment and Outdoor Workplaces. Electron. Physician 2013, 5, 706–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazari, S.A.; Ali, E.; Abro, R.; Khan, F.S.A.; Ahmed, I.; Ahmed, M.; Nizamuddin, S.; Siddiqui, T.H.; Hossain, N.; Mubarak, N.M.; et al. Nanomaterials: Applications, waste-handling, environmental toxicities, and future challenges—A review. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 105028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.F.; Mofijur, M.; Rafa, N.; Chowdhury, A.T.; Chowdhury, S.; Nahrin, M.; Islam, A.B.M.S.; Ong, H.C. Green approaches in synthesising nanomaterials for environmental nanobioremediation: Technological advancements, applications, benefits and challenges. Environ. Res. 2022, 204, 111967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elgohary, E.A.; Mohamed, Y.M.A.; El Nazer, H.A.; Baaloudj, O.; Alyami, M.S.S.; El Jery, A.; Assadi, A.A.; Amrane, A. A Review of the Use of Semiconductors as Catalysts in the Photocatalytic Inactivation of Microorganisms. Catalysts 2021, 11, 1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameta, R.; Solanki, M.S.; Benjamin, S.; Ameta, S.C. Chapter 6—Photocatalysis. In Advanced Oxidation Processes for Waste Water Treatment; Ameta, S.C., Ameta, R., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2018; pp. 135–175. ISBN 978-0-12-810499-6. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, B.; Wu, H.; Parkin, I.P. New Insights into the Fundamental Principle of Semiconductor Photocatalysis. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 14847–14856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jabbar, Z.H.; Graimed, B.H. Recent developments in industrial organic degradation via semiconductor heterojunctions and the parameters affecting the photocatalytic process: A review study. J. Water Process Eng. 2022, 47, 102671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafari, T.; Moharreri, E.; Amin, A.S.; Miao, R.; Song, W.; Suib, S.L. Photocatalytic Water Splitting—The Untamed Dream: A Review of Recent Advances. Molecules 2016, 21, 900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Mao, Q.; Jian, L.; Dong, Y.; Zhu, Y. Photodeposition of earth-abundant cocatalysts in photocatalytic water splitting: Methods, functions, and mechanisms. Chin. J. Catal. 2022, 43, 1774–1804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kausar, F.; Varghese, A.; Pinheiro, D.; Devi, K.R.S. Recent trends in photocatalytic water splitting using titania based ternary photocatalysts—A review. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2022, 47, 22371–22402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasija, V.; Raizada, P.; Singh, P.; Verma, N.; Khan, A.A.P.; Singh, A.; Selvasembian, R.; Kim, S.Y.; Hussain, C.M.; Nguyen, V.-H.; et al. Progress on the photocatalytic reduction of hexavalent Cr(VI) using engineered graphitic carbon nitride. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2021, 152, 663–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Feng, C.; Tang, L.; Zeng, G.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, M. Nanohybrid Photocatalysts for Heavy Metal Pollutant Control. In Nanohybrid and Nanoporous Materials for Aquatic Pollution Control; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 125–153. ISBN 9780128141557. [Google Scholar]

- Arora, I.; Chawla, H.; Chandra, A.; Sagadevan, S.; Garg, S. Advances in the strategies for enhancing the photocatalytic activity of TiO2: Conversion from UV-light active to visible-light active photocatalyst. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2022, 143, 109700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Wang, X.; Liu, H.; Liu, C.; Wan, Y.; Long, Y.; Cai, Z. Recent Advances and Applications of Semiconductor Photocatalytic Technology. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 2489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Hu, Y.; Gu, H. Ultraviolet Detectors Based on Wide Bandgap Semiconductor Nanowire: A Review. Sensors 2018, 18, 2072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohadesi, M.; Sanavi Fard, M.; Shokri, A. The application of modified nano-TiO2 photocatalyst for wastewater treatment: A review. Int. J. Environ. Anal. Chem. 2022, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Domen, K. Particulate Photocatalysts for Light-Driven Water Splitting: Mechanisms, Challenges, and Design Strategies. Chem. Rev. 2020, 120, 919–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parul; Kaur, K.; Badru, R.; Singh, P.P.; Kaushal, S. Photodegradation of organic pollutants using heterojunctions: A review. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 103666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhebshi, A.; Sharaf Aldeen, E.; Mim, R.S.; Tahir, B.; Tahir, M. Recent advances in constructing heterojunctions of binary semiconductor photocatalysts for visible light responsive CO2 reduction to energy efficient fuels: A review. Int. J. Energy Res. 2022, 46, 5523–5584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, Q.; Zeng, G.; Song, J.; Liu, C.; Wang, Z.; Wu, S. Ultrasonic power combined with seed materials for recovery of phosphorus from swine wastewater via struvite crystallization process. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 293, 112961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Yu, Y.; Zhu, X.; Fang, J.; Xu, W.; Hu, X.; Li, R.; Yao, L.; Qin, J.; Fang, Z. Semiconductor heterojunctions for photocatalytic hydrogen production and Cr(VI) Reduction: A review. Mater. Res. Bull. 2022, 147, 111636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eivazihollagh, A.; Bäckström, J.; Dahlström, C.; Carlsson, F.; Ibrahem, I.; Lindman, B.; Edlund, H.; Norgren, M. One-pot synthesis of cellulose-templated copper nanoparticles with antibacterial properties. Mater. Lett. 2017, 187, 170–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.; Chen, S.; Zeng, G.; Gong, X.; Zhou, C.; Cheng, M.; Xue, W.; Yan, X.; Li, J. Artificial Z-scheme photocatalytic system: What have been done and where to go? Coord. Chem. Rev. 2019, 385, 44–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasija, V.; Kumar, A.; Sudhaik, A.; Raizada, P.; Singh, P.; Van Le, Q.; Le, T.T.; Nguyen, V.-H. Step-scheme heterojunction photocatalysts for solar energy, water splitting, CO2 conversion, and bacterial inactivation: A review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2021, 19, 2941–2966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- San Martín, S.; Rivero, M.J.; Ortiz, I. Unravelling the Mechanisms that Drive the Performance of Photocatalytic Hydrogen Production. Catalysts 2020, 10, 901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Zong, X.; An, L.; Hua, S.; Miao, X.; Luan, S.; Wen, Y.; Tao, F.F.; Sun, Z. Consciously Constructing Heterojunction or Direct Z-Scheme Photocatalysts by Regulating Electron Flow Direction. ACS Catal. 2018, 8, 2209–2217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Lin, Z.; Shen, S.; Zhong, W.; Cao, S. Advances in designing heterojunction photocatalytic materials. Chin. J. Catal. 2021, 42, 710–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Zhang, L.; Cheng, B.; Fan, J.; Yu, J. S-Scheme Heterojunction Photocatalyst. Chem 2020, 6, 1543–1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stelo, F.; Kublik, N.; Ullah, S.; Wender, H. Recent advances in Bi2MoO6 based Z-scheme heterojunctions for photocatalytic degradation of pollutants. J. Alloys Compd. 2020, 829, 154591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kafle, B.P. Chapter 6—Introduction to nanomaterials and application of UV–Visible spectroscopy for their characterization. In Chemical Analysis and Material Characterization by Spectrophotometry; Kafle, B.P., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 147–198. ISBN 978-0-12-814866-2. [Google Scholar]

- Dahiya, M.S.; Tomer, V.K.; Duhan, S. 31—Metal–ferrite nanocomposites for targeted drug delivery. In Woodhead Publishing Series in Biomaterials; Asiri, Inamuddin, A.M., Mohammad, A., Eds.; Woodhead Publishing: Sawston, UK, 2018; pp. 737–760. ISBN 978-0-12-813741-3. [Google Scholar]

- Da Silva, A.K.; Ricci, T.G.; De Toffoli, A.L.; Maciel, E.V.S.; Nazario, C.E.D.; Lanças, F.M. Chapter 4—The role of magnetic nanomaterials in miniaturized sample preparation techniques. In Handbook on Miniaturization in Analytical Chemistry; Hussain, C.M., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 77–98. ISBN 978-0-12-819763-9. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, W.; Yang, J.; Zhang, J.; Li, W.; Sun, C.; Zhao, H.; Wen, Y.; Sha, O.; Liang, B. Recent progress in SnO2/g-C3N4 Heterojunction Photocatalysts: Synthesis, Modification, and Application. J. Alloy. Compd. 2022, 906, 164372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, C.; Liu, Q.; Tang, H.; Yuvaraja, G.; Long, J.; Rammohan, A.; Zyryanov, G. V An overview of graphene oxide supported semiconductors based photocatalysts: Properties, synthesis and photocatalytic applications. J. Mol. Liq. 2020, 297, 111826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parashar, M.; Shukla, V.K.; Singh, R. Metal oxides nanoparticles via sol–gel method: A review on synthesis, characterization and applications. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2020, 31, 3729–3749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, A.; Saha, N.; Majumdar, G.B.T.-R.M. in M.S. and M.E. Fabrication and Characterization of Flexible Semi-conducting Nanocomposite Polymer. In Reference Module in Materials Science and Materials Engineering; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; ISBN 978-0-12-803581-8. [Google Scholar]

- Yilmaz, E.; Soylak, M. 15—Functionalized nanomaterials for sample preparation methods. In Handbook of Nanomaterials in Analytical Chemistry; Hussain, C.M., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 375–413. ISBN 978-0-12-816699-4. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, G.; Kumar, A.; Sharma, S.; Naushad, M.; Prakash Dwivedi, R.; ALOthman, Z.A.; Mola, G.T. Novel development of nanoparticles to bimetallic nanoparticles and their composites: A review. J. King Saud Univ. Sci. 2019, 31, 257–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Tiwari, S.P.; Ntwaeaborwa, O.M.; Swart, H.C. 10—Luminescence properties of rare-earth doped oxide materials. In Woodhead Publishing Series in Electronic and Optical Materials; Dhoble, S.J., Pawade, V.B., Swart, H.C., Chopra, V.B., Eds.; Woodhead Publishing: Sawston, UK, 2020; pp. 345–364. ISBN 978-0-08-102935-0. [Google Scholar]

- Ben Smida, Y. Synthesis Methods in Solid-State Chemistry; Marzouki, R., Ed.; IntechOpen: Rijeka, Croatia, 2020; Chapter 2; pp. 1–16. ISBN 978-1-83880-224-0. [Google Scholar]

- Foroughi, F.; Lamb, J.J.; Burheim, O.S.; Pollet, B.G. Sonochemical and Sonoelectrochemical Production of Energy Materials. Catalysts 2021, 11, 284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentes-García, J.A.; Carvalho Alavarse, A.; Moreno Maldonado, A.C.; Toro-Córdova, A.; Ibarra, M.R.; Goya, G.F. Simple Sonochemical Method to Optimize the Heating Efficiency of Magnetic Nanoparticles for Magnetic Fluid Hyperthermia. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 26357–26364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, X.; Meng, X. Photocatalysis for Heavy Metal Treatment: A Review. Processes 2021, 9, 1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basaleh, A.S.; Mahmoud, M.H.H. MnCo2O4@ZrO2 nanocomposites prepared via facile route toward photoreduction of Hg (II) ions. Opt. Mater. 2022, 125, 112135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, C.V.; Koutavarapu, R.; Shim, J.; Cheolho, B.; Reddy, K.R. Novel g-C3N4/Cu-doped ZrO2 hybrid heterostructures for efficient photocatalytic Cr(VI) photoreduction and electrochemical energy storage applications. Chemosphere 2022, 295, 133851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzad, K.; Tahir, M.B.; Sagir, M.; Kabli, M.R. Role of CuCo2S4 in Z-scheme MoSe2/BiVO4 composite for efficient photocatalytic reduction of heavy metals. Ceram. Int. 2019, 45, 23225–23232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wang, X.; Li, N.; Xia, J.; Meng, Q.; Ding, J.; Lu, J. Synthesis and characterization of TiO2/graphene oxide nanocomposites for photoreduction of heavy metal ions in reverse osmosis concentrate. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 34241–34251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raja, A.; Rajasekaran, P.; Selvakumar, K.; Arivanandhan, M.; Asath Bahadur, S.; Swaminathan, M. Efficient Photoreduction of Hexavalent Chromium Using the Reduced Graphene Oxide–Sm2MoO6–TiO2 Catalyst under Visible Light Illumination. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 6414–6422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spanu, D.; Dal Santo, V.; Malara, F.; Naldoni, A.; Turolla, A.; Antonelli, M.; Dossi, C.; Marelli, M.; Altomare, M.; Schmuki, P.; et al. Photoelectrocatalytic oxidation of As(III) over hematite photoanodes: A sensible indicator of the presence of highly reactive surface sites. Electrochim. Acta 2018, 292, 828–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raez, J.M.; Arencibia, A.; Segura, Y.; Arsuaga, J.M.; López-Muñoz, M.J. Combination of immobilized TiO2 and zero valent iron for efficient arsenic removal in aqueous solutions. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2021, 258, 118016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmanvandi, H.; Rezaei, P.; Tamsilian, Y. Photoreduction and Removal of Cadmium Ions over Bentonite Clay-Supported Zinc Oxide Microcubes in an Aqueous Solution. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 13176–13184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, H.; Salimi, F.; Golmohammadi, F. Removal of Cadmium from Aqueous Solution by Nano Composites of Bentonite /TiO2 and Bentonite/ZnO Using Photocatalysis Adsorption Process. Silicon 2020, 12, 2721–2731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murruni, L.; Conde, F.; Leyva, G.; Litter, M.I. Photocatalytic reduction of Pb(II) over TiO2: New insights on the effect of different electron donors. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2008, 84, 563–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanakaraju, D.; Rusydah bt Mohamad Shahdad, N.; Lim, Y.-C.; Pace, A. Concurrent removal of Cr(III), Cu(II), and Pb(II) ions from water by multifunctional TiO2/Alg/FeNPs beads. Sustain. Chem. Pharm. 2019, 14, 100176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, R.M.; Ismail, A.A. Photocatalytic reduction and removal of mercury ions over mesoporous CuO/ZnO S-scheme heterojunction photocatalyst. Ceram. Int. 2021, 47, 9659–9667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spanu, D.; Bestetti, A.; Hildebrand, H.; Schmuki, P.; Altomare, M.; Recchia, S. Photocatalytic reduction and scavenging of Hg(ii) over templated-dewetted Au on TiO2 nanotubes. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2019, 18, 1046–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivakumar, R.; Lee, N.Y. Emerging bismuth-based direct Z-scheme photocatalyst for the degradation of organic dye and antibiotic residues. Chemosphere 2022, 297, 134227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benkhaya, S.; M’ rabet, S.; El Harfi, A. A review on classifications, recent synthesis and applications of textile dyes. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2020, 115, 107891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lellis, B.; Fávaro-Polonio, C.Z.; Pamphile, J.A.; Polonio, J.C. Effects of textile dyes on health and the environment and bioremediation potential of living organisms. Biotechnol. Res. Innov. 2019, 3, 275–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardila-Leal, L.D.; Poutou-Piñales, R.A.; Pedroza-Rodríguez, A.M.; Quevedo-Hidalgo, B.E. A Brief History of Colour, the Environmental Impact of Synthetic Dyes and Removal by Using Laccases. Molecules 2021, 26, 3813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]