Comparison of Methods for the Extraction of Saponins from Sechium spp. Genotypes and Their Spectrophotometric Quantification

Abstract

1. Introduction

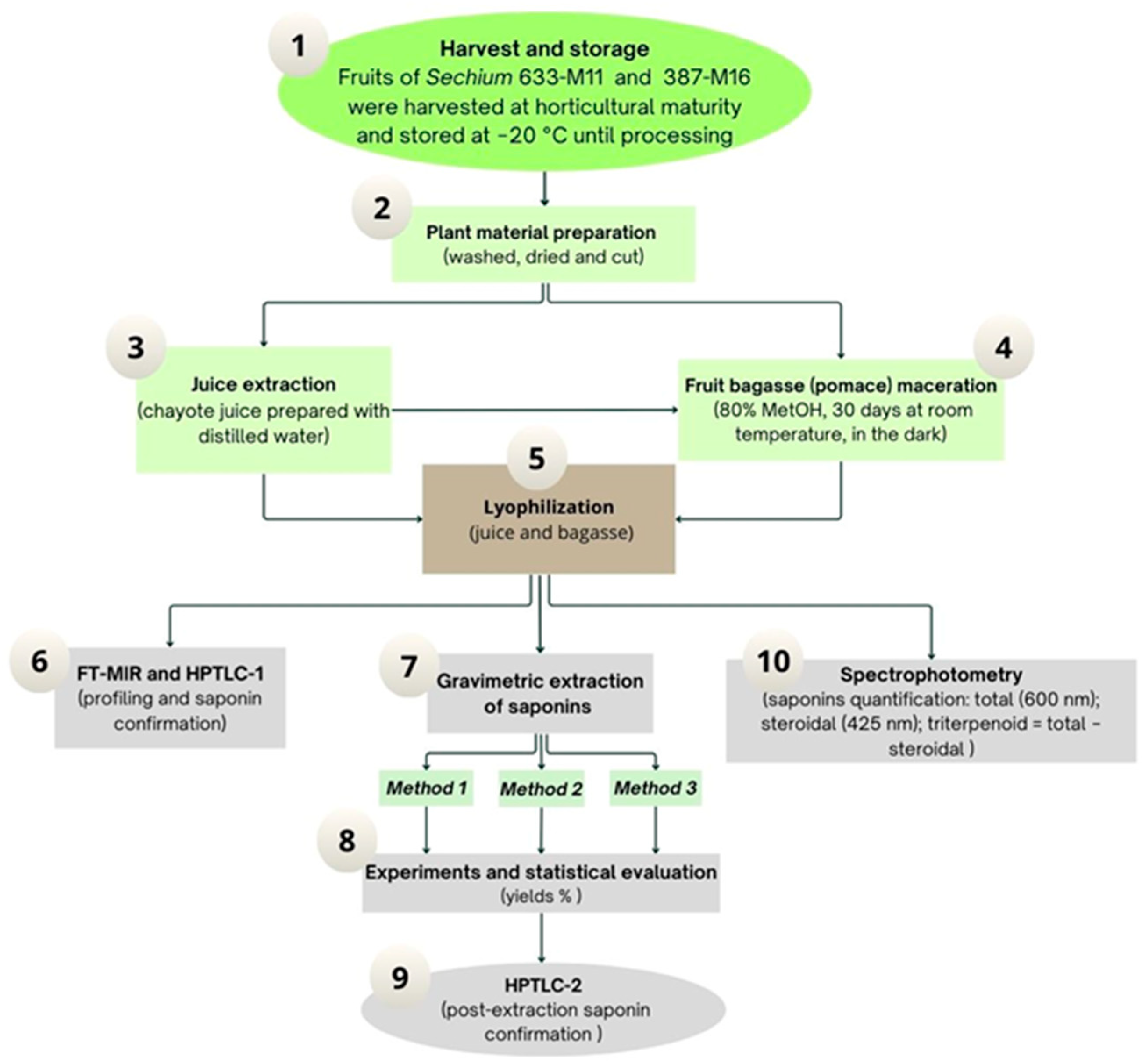

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material

2.2. Chemicals

2.3. Juice Extraction

2.4. Maceration of Fruit Bagasse

2.5. Foam Formation and Persistence Test

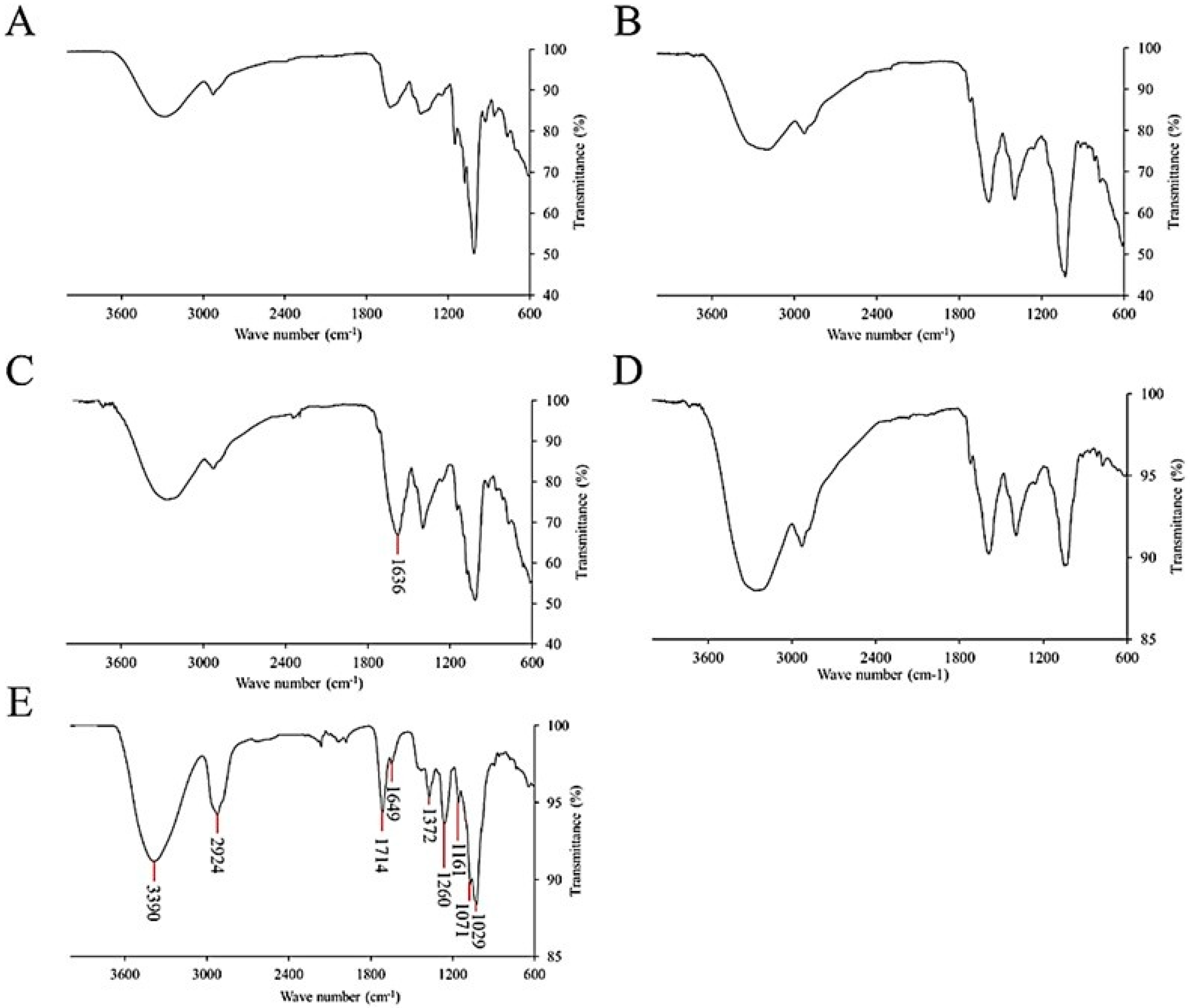

2.6. Fourier Transform Mid-Infrared Spectroscopy (FT-MIR) Spectroscopic Analysis and Sample Preparation

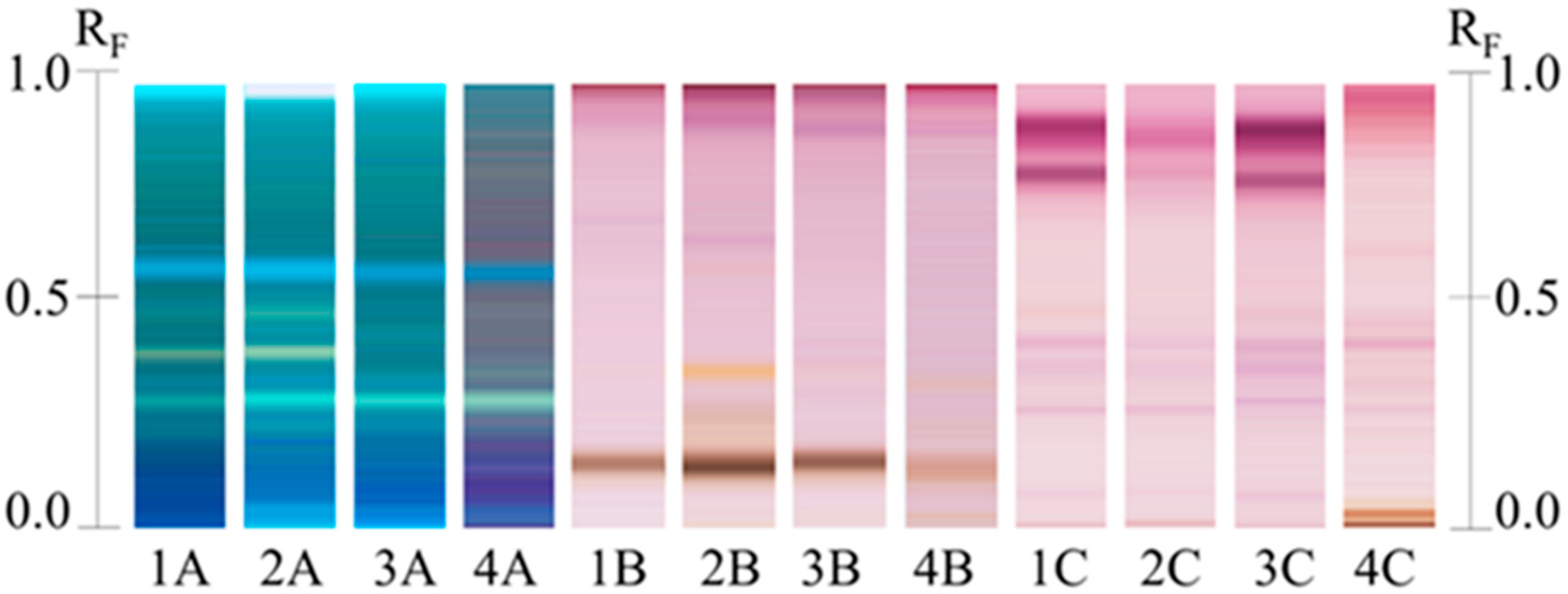

2.7. High-Performance Thin-Layer Chromatography (HPTLC)

2.8. Gravimetric Methods for Saponin Extraction from Sechium

2.8.1. Method 1 (M1)

2.8.2. Method 2 (M2)

2.8.3. Method 3 (M3)

2.9. Quantification of Saponins by Spectrophotometry

2.10. Data Processing and Analysis

2.10.1. Data Processing

2.10.2. Statistical Analysis

2.10.3. Analytical Greenness Assessment

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Processing Yields of Sechium Juice and Bagasse

3.2. Foam Test

3.3. FT-MIR Profiling and Functional Group Identification

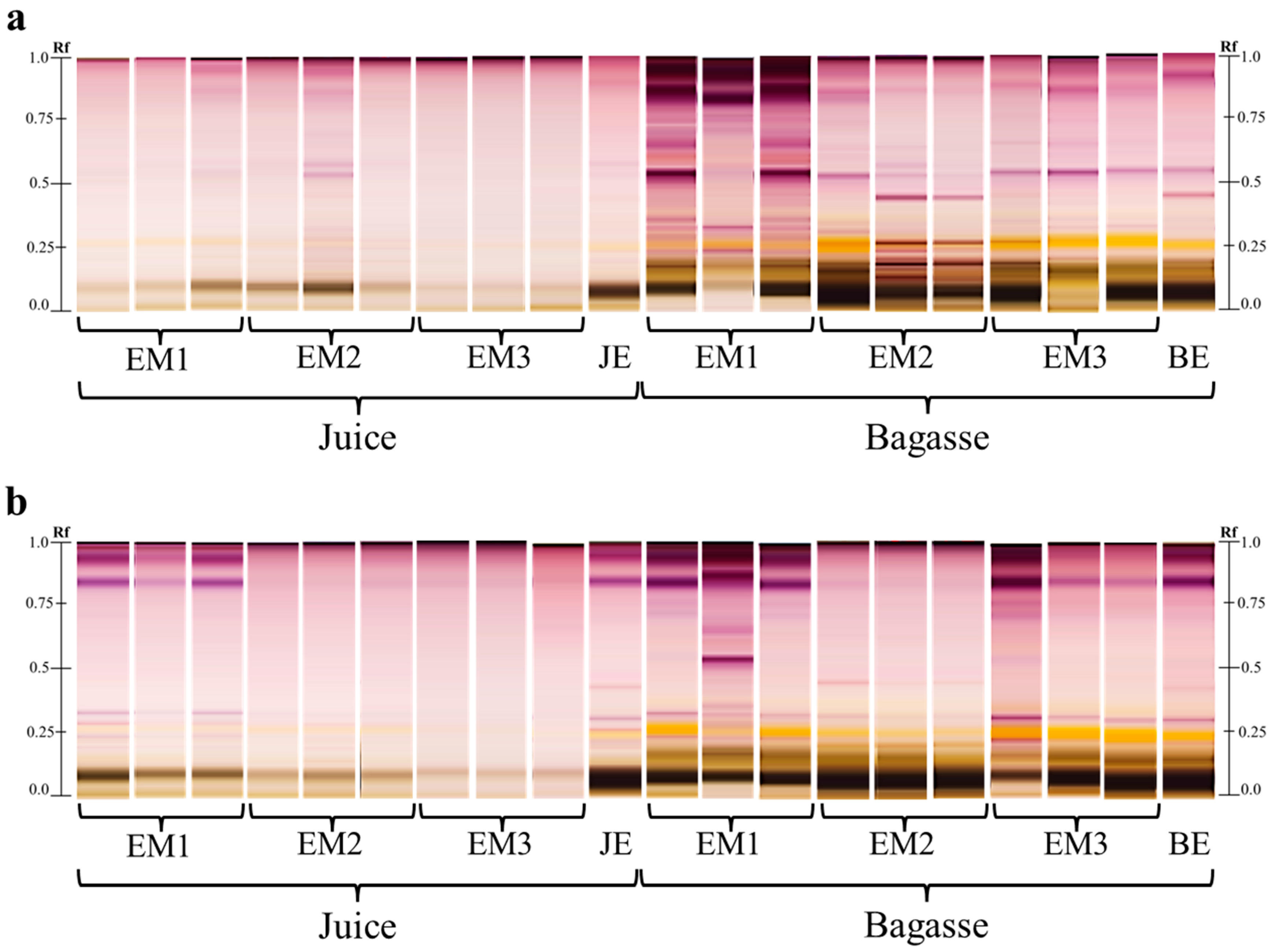

3.4. Metabolite Profiling by High Performance Thin Layer Chromatography (HPTLC)

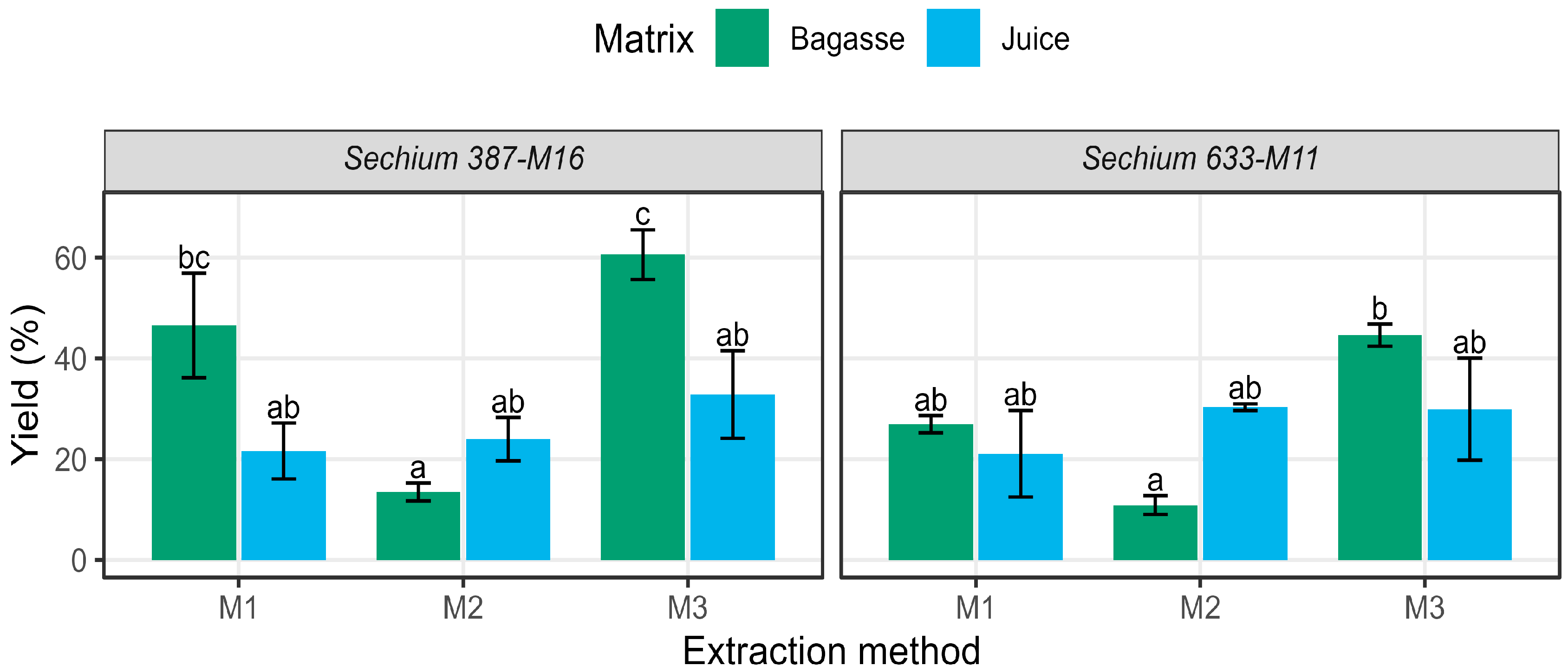

3.5. Gravimetric Extraction Yields

3.6. HPTLC Confirmation of Saponins Extraction

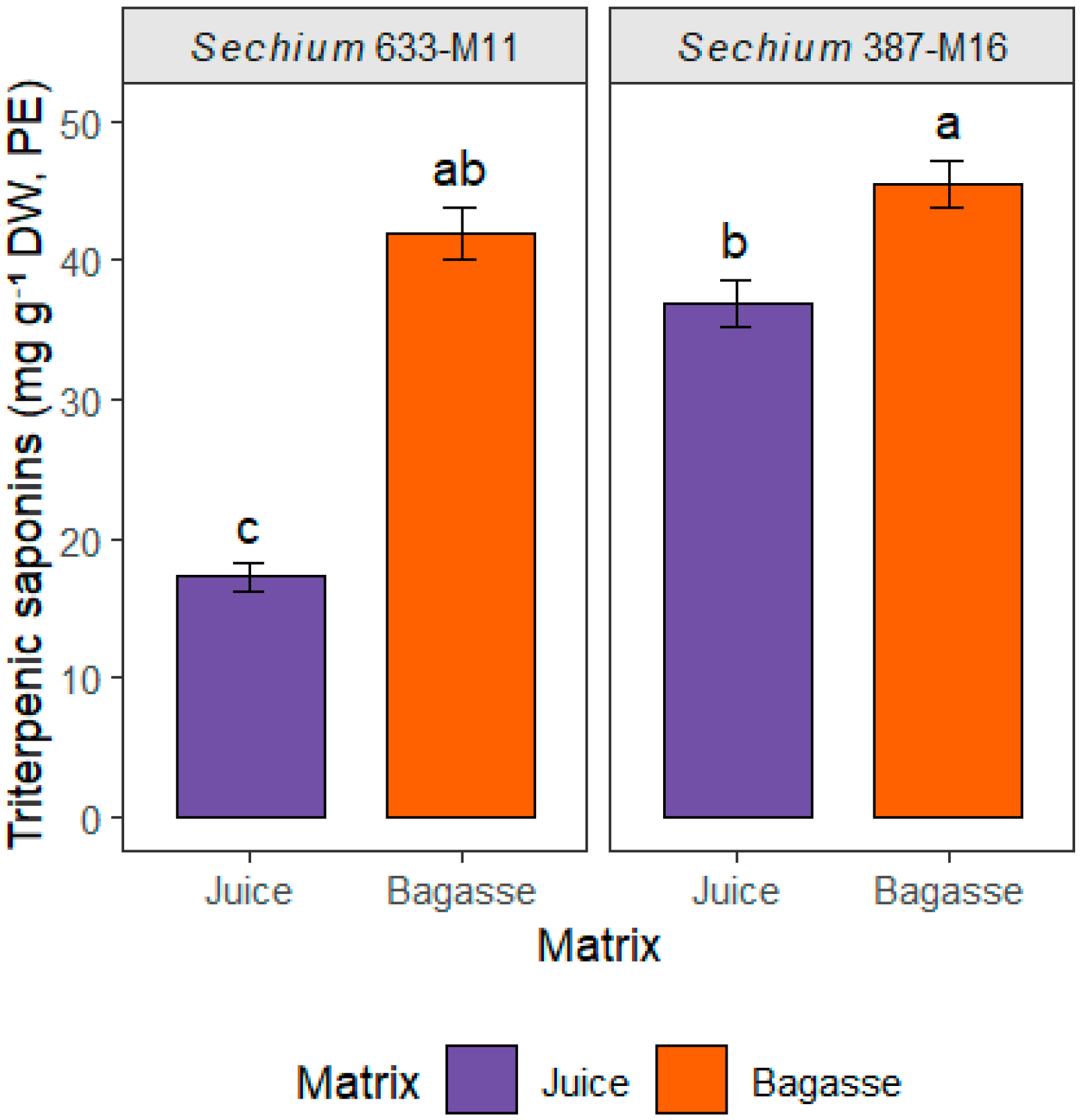

3.7. Spectrophotometric Quantification of Saponins

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ANOVA | Analysis of variance |

| BE | Bagasse extract |

| BuOH | n-butanol |

| CV | Coefficient of variation |

| DF | Dilution factor |

| DW | Dry Weight |

| FT-MIR | Fourier transform mid-infrared spectroscopy |

| H2SO4 | Sulfuric acid |

| HPLC-DAD | High-performance liquid chromatography with diode-array detection |

| HPTLC | High-performance thin-layer chromatography |

| HSD | Tukey’s honestly significant difference |

| JE | Juice extract |

| MeOH | Methanol |

| ND | Not detected |

| NPR | Natural products reagent |

| OLS | Ordinary least squares (regression) |

| PE | Protodioscin equivalents |

| Rf | Retardation factor (TLC) |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| SE | Standard Error |

| UHPLC-QTOF-MS | Ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography-quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry |

| UV | Ultraviolet |

| WGS84 | World Geodetic System 1984 |

| M1, M2, M3 | Gravimetric extraction methods 1–3 |

Appendix A. Cultivation Site and Soil Conditions

Appendix B. Detailed Spectrophotometric Workflow for Saponins Quantification (Le Bot et al., 2022 [40] Method Adapted)

- Reference material (steroidal saponins)

- 2.

- Preparation of Agave lechuguilla extract

- 3.

- Preparation of Agave/Sechium extract mixtures (w/w)

| Agave/Sechium Proportion (w/w) | Agave (mg) | Sechium (mg) | Total Mass (mg) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 20:80 | 100 | 400 | 500 |

| 50:50 | 250 | 250 | 500 |

| 80:20 | 400 | 100 | 500 |

- 4.

- Extraction and Sample Preparation

- 5.

- Total Saponin Sample assay (600 nm)

- 6.

- Steroidal Saponin assay (425 nm)

- 7.

- Calibration curves and reporting criteria

- 8.

- Triterpenoid saponin determination and ND rule

Appendix C. Mass Balance of Recovered Solids

| Sechium Genotype | Juice Solids (g) | Bagasse Extract Solids (g) | Total Solids Recovered (g) | Share of Total Solids, Juice (%) a | Share of Total Solids, Bagasse Extract (%) a | Residual Dry Bagasse (g) | Extractable Fraction of Initial Dry Bagasse (%) b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 633-M11 | 215.2 | 62.3 | 277.5 | 77.6 | 22.4 | 695 | 8.2 |

| 387-M16 | 136.1 | 176.9 | 313.0 | 43.5 | 56.5 | 635 | 21.8 |

References

- Wang, P.; Wei, G.; Feng, L. Research advances in oxidosqualene cyclase in plants. Forests 2022, 13, 1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, A.V.; Arinchedathu Surendran, V.; Sukumaran, S.T. Bioactive metabolites in gymnosperms. In Plant Metabolites: Methods, Applications and Prospects; Sukumaran, S.T., Sugathan, S., Abdulhameed, S., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De La Torre, A.R.; Piot, A.; Liu, B.; Wilhite, B.; Weiss, M.; Porth, I. Functional and morphological evolution in gymnosperms: A portrait of implicated gene families. Evol. Appl. 2020, 13, 210–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sugita, P.; Ustati, M.N.; Kurniawanti; Syahbirin, G.; Dianhar, H.; Rahayu, D.U.C. Phytochemical analysis and antioxidant activity of Araucaria spp. from Taman Bunga Nusantara, Cianjur, West Java, Indonesia. Biodiversitas 2025, 26, 118–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patial, P.K.; Sud, D. Bioactive phytosteroids from Araucaria columnaris (G. Forst.) Hook.: RP-HPLC-DAD analysis, in-vitro antioxidant potential, in-silico computational study and molecular docking against 3MNG and 1N3U. Steroids 2022, 188, 109116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurniawanti; Agusta, D.D.; Dianhar, H.; Rahayu, D.U.C.; Sugita, P. Phytochemical screening and preliminary evaluation of antioxidant activity of three Indonesian Araucaria leaves extracts. Sci. Arch. 2021, 2, 250–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadav, K.M.; Ninge Gowda, K.N. Preliminary phytochemical analysis and in-vitro antioxidant activity of Araucaria columnaris bark peel and Cosmos sulphureus flowers. Int. J. Curr. Pharm. Res. 2017, 9, 96–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, G.R.; Goud, D.R.; Ranjani, P.H.; Kirthi, P.S. Preliminary phytochemical screening of Araucaria heterophylla leaves. World J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 2017, 6, 1950–1956. [Google Scholar]

- Batiha, G.E.-S.; Teibo, J.O.; Shaheen, H.M.; Akinfe, O.A.; Awad, A.A.; Teibo, T.K.A.; Alexiou, A.; Papadakis, M. Bioactive compounds, pharmacological actions and pharmacokinetics of Cupressus sempervirens. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 2023, 396, 389–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moses, T.; Papadopoulou, K.K.; Osbourn, A. Metabolic and functional diversity of saponins, biosynthetic intermediates and semi-synthetic derivatives. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2014, 49, 439–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, X.; Ma, X.; Li, C.; Meng, H.; Han, C. A review: Structure–activity relationship between saponins and cellular immunity. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2023, 50, 2779–2793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparg, S.G.; Light, M.E.; van Staden, J. Biological activities and distribution of plant saponins. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2004, 94, 219–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales-Vela, K.; Pérez-Sánchez, F.C.; Padrón, J.M.; Márquez-Fernández, O. Antiproliferative activity of Cucurbitaceae species extracts from southeast of Mexico. J. Med. Plants Stud. 2020, 8, 20–25. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández-Carlos, B.; González-Coloma, A.; Orozco-Valencia, A.U.; Ramírez-Mares, M.V.; Andrés-Yeves, M.F.; Joseph-Nathan, P. Bioactive saponins from Microsechium helleri and Sicyos bulbosus. Phytochemistry 2011, 72, 743–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- León, I.; Enríquez, R.G.; McLean, S.; Reynolds, W.F.; Yu, M. Isolation and identification by 2D NMR of two new complex saponins from Microsechium helleri. Magn. Reson. Chem. 1998, 36, S111–S117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, G.; Zhou, P.; Li, P.; Zhao, Z.; Zhang, R.; Tang, X.; Wang, Z.; Wei, Z.; et al. Saponins from Momordica charantia exert hypoglycemic effect in diabetic mice by multiple pathways. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 11, 7626–7637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, J.; Yang, H.; Chen, Y.; Feng, X.; Wu, C.; Long, F. Purified saponins in Momordica charantia treated with high hydrostatic pressure and ionic liquid-based aqueous biphasic systems. Foods 2022, 11, 1930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augustin, J.; Kuzina, V.; Andersen, S.B.; Bak, S. Molecular activities, biosynthesis and evolution of triterpenoid saponins. Phytochemistry 2011, 72, 435–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timilsena, Y.P.; Phosanam, A.; Stockmann, R. Perspectives on saponins: Food functionality and applications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 13538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smail, H.O. The roles of genes in the bitter taste. AIMS Genet. 2019, 6, 88–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wooding, S.P.; Ramirez, V.A. Global population genetics and diversity in the TAS2R bitter taste receptor family. Front. Genet. 2022, 13, 952299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morini, G. The taste for health: The role of taste receptors and their ligands in the complex food/health relationship. Front. Nutr. 2024, 11, 1396393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, L.T.P.; Nachtigal, M.W.; Selman, T.; Nguyen, E.; Salsman, J.; Dellaire, G.; Dupré, D.J. Bitter taste receptors are expressed in human epithelial ovarian and prostate cancer cells and noscapine stimulation impacts cell survival. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2019, 454, 203–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delgado-Tiburcio, E.E.; Cadena-Íñiguez, J.; Santiago-Osorio, E.; Ruiz-Posadas, L.d.M.; Castillo-Juárez, I.; Aguiñiga-Sánchez, I.; Soto-Hernández, M. Pharmacokinetics and biological activity of cucurbitacins. Pharmaceuticals 2022, 15, 1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, A.; Jeffery, E.H.; Miller, M.J. Is bitterness only a taste? The expanding area of health benefits of Brassica vegetables and potential for bitter taste receptors to support health benefits. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newstrom, L.E. Evidence for the origin of chayote Sechium edule (Cucurbitaceae). Econ. Bot. 1991, 45, 410–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lira, R.; Bye, R. Las cucurbitáceas en la alimentación de los dos mundos. In Conquista y Comida: Consecuencias del Encuentro de Dos Mundos, 3rd ed.; UNAM-IIH: Mexico City, Mexico, 2018; pp. 199–226. [Google Scholar]

- Bye, R.; Linares, E. Plantas medicinales del México prehispánico. Arqueol. Mex. 1999, 7, 4–13. [Google Scholar]

- Cadena-Íñiguez, J.; Arévalo-Galarza, M.d.L.C. Las Variedades del Chayote (Sechium Edule (Jacq.) Sw.) y su Comercio Mundial; Colegio de Postgraduados; Mundi-Prensa: Mexico City, Mexico, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Cadena-Iñiguez, J.; Arévalo-Galarza, M.d.L.; Santiago-Osorio, E.; Aguiñiga-Sánchez, I.; Cadena-Zamudio, J.D.; Soto-Hernández, M.; Ramírez-Rodas, Y.C.; Ruiz-Posadas, L.M.; Salazar-Aguilar, S.; Cisneros-Solano, V.M. Genotypes of Sechium spp. as a source of natural products with biological activity. Life 2024, 15, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto-Hernández, R.M.; Ruiz-Posadas, L.M.; Aguiñiga-Sánchez, I.; Santiago-Osorio, E.; Arévalo-Galarza, M.L.; Avendaño-Arrazate, C.H.; Cisneros-Solano, V.M.; Cadena-Iñiguez, J. Uso de chayotes mexicanos para tratamiento de enfermedades de interés público. Rev. Agroproductividad 2018, 9, 51–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguiñiga-Sánchez, I.; Soto-Hernández, R.M.; Cadena-Iñiguez, J.; Ruiz-Posadas, L.M.; Cadena-Zamudio, J.D.; González-Ugarte, A.K.; Steider, B.W.; Santiago-Osorio, E. Fruit extract from a Sechium edule hybrid induces apoptosis in leukemic cell lines but not in normal cells. Nutr. Cancer 2015, 67, 250–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, V.H.; Ramirez, E.; Mora, G.A.; Iwase, Y.; Nagao, T.; Okabe, H.; Matsunaga, H.; Katano, M.; Mori, M. Structures and antiproliferative activity of saponins from Sechium pittieri and S. talamancense. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1997, 45, 349–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Carlos, B.; Carmona-Pineda, M.; Villanueva-Cañongo, C.; López-Olguín, J.F.; Aragón-García, A.; Joseph-Nathan, P. New saponins from Sechium mexicanum. Magn. Reson. Chem. 2009, 47, 994–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fordos, S.; Amin, S.; Abid, N.; Pasha, I.; Khan, M.K.I.; Amin, A.; Gulzar, M.; Subtain, M.; Abdi, G. Saponins: Advances in extraction techniques, functional properties, and industrial applications. Appl. Food Res. 2025, 5, 101146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadena-Iñiguez, J.; Avendaño-Arrazate, C.H.; Cisneros-Solano, V.M.; Ruiz-Posadas, L.M.; Arévalo-Galarza, M.L.; Aguirre-Medina, J.F. Protección de variedades criollas de uso común de chayotes mexicanos. Rev. Agroproductividad 2018, 9, 65–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadena-Iñiguez, J.; Arévalo-Galarza, M.d.L.; Aguirre-Medina, J.F.; Avendaño-Arrazate, C.H.; Cadena-Zamudio, D.A.; Cadena-Zamudio, J.D.; Soto-Hernández, R.M.; Cisneros-Solano, V.M.; Ruiz-Posadas, L.d.M.; Soto-Mendoza, C. Chayote [Sechium edule (Jacq.) Sw.] Fruit Quality Influenced by Plant Pruning. Horticulturae 2025, 11, 965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fichou, D.; Ristivojević, P.; Morlock, G.E. Proof-of-principle of rTLC, an open-source software developed for image evaluation and multivariate analysis of planar chromatograms. Anal. Chem. 2016, 88, 12494–12501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Aziz, M.M.A.; Said-Ashour, A.; Gomha-Melad, A.S. A review on saponins from medicinal plants: Chemistry, isolation, and determination. J. Nanomed. Res. 2019, 8, 282–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Bot, M.; Thibault, J.; Pottier, Q.; Boisard, S.; Guilet, D. An accurate, cost-effective and simple colorimetric method for the quantification of total triterpenoid and steroidal saponins from plant materials. Food Chem. 2022, 383, 132597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukanya, P.; Hiremath, L. Qualitative and quantitative estimation of phyto-constituents in Hemidismus indicus roots by using advanced analytical tools. Int. J. Pharm. Clin. Res. 2019, 1, 40–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojnowski, W.; Tobiszewski, M.; Pena-Pereira, F.; Psillakis, E. AGREEprep—Analytical Greenness Metric for Sample Preparation. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2022, 149, 116553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, S.; Acharya-Siwakoti, E.; Kafle, A.; Devkota, H.P.; Bhattarai, A. Plant-derived saponins: A review of their surfactant properties and applications. Sci 2021, 3, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aluola, E.E.; Ogbeide, S.E.; Obahiagbon, K.O. Detection and characterization of saponins in some indigenous plants using UV, FTIR, and XRD spectroscopy. Int. J. Eng. Adv. Technol. Stud. 2021, 9, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Velázquez-Martínez, J.R.; González-Cervantes, R.M.; Hernández-Gallegos, M.A.; Mendiola, R.C.; Aparicio, A.R.J.; Ocampo, M.L.A. Prebiotic potential of Agave angustifolia Haw fructans with different degrees of polymerization. Molecules 2014, 19, 12660–12675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kareru, P.G.; Keriko, J.M.; Gachanja, A.N.; Kenji, G. Direct detection of triterpenoid saponins in medicinal plants. Afr. J. Tradit. Complement. Altern. Med. 2007, 5, 56–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhajan, C.; Soulange, J.G.; Ranghoo-Sanmukhiya, V.M.; Olędzki, R.; Ociński, D.; Jacukowicz-Sobala, I.; Zając, A.; Howes, M.J.; Harasym, J. Nutraceutical potentital of Sideroxylon cinereum, an endemic Mauritian fruit of the Sapotaceae family, through the elucidation of its phytochemical composition and antioxidant activity. Molecules 2025, 30, 3041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iñiguez-Luna, M.I.; Cadena-Iñiguez, J.; Soto-Hernández, R.M.; Morales-Flores, F.J.; Cortes-Cruz, M.; Watanabe, K.N. Natural bioactive compounds of Sechium spp. for therapeutic and nutraceutical supplements. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 772389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, H.; Bladt, S. Plant Drug Analysis: A Thin Layer Chromatography Atlas; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Gavrila, A.I.; Rodica, T.; Seciu-Grama, A.M.; Tanase, C.; Tarcomnicu, I.; Negrea, C.; Calinescu, I.; Zalaru, C.; Moldovan, L.; Raiciu, A.D.; et al. Ultrasound-assisted extraction for saponins from Hedera helix L. and an in vitro biocompatibility evaluation of the extracts. Pharmaceuticals 2022, 15, 1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Zheng, H.; Zheng, T.; Jiang, J.; Xu, Y.; Jia, F.; He, K.; Yang, Y. Quantitative changes and transformation mechanisms of saponin components in Chinese herbal medicines during storage and processing: A review. Molecules 2024, 29, 4486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zannino, L.; Carelli, M.; Milanesi, G.; Croce, A.C.; Biggiogera, M.; Confalonieri, M. Histochemical and ultrastructural localization of triterpene saponins in Medicago truncatula. Microsc. Res. Tech. 2024, 87, 2143–2153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chua, L.S.; Goh, K.K.; Chew, L.Y.; Eng, C.M.; Tan, C.P.; Hena, S. Solvent fractionation and acetone precipitation for crude saponins from Eurycoma longifolia extract. Molecules 2019, 24, 1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajnos, A.; Oleszek, W. TLC of triterpenes (including saponins). In Thin-Layer Chromatography in Phytochemistry; CRC Press/Taylor & Francis: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Kowalska, T.; Sajewicz, M. Thin layer chromatography in the screening of botanicals—Its versatile potential and selected applications. Molecules 2022, 27, 6607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, Y.; Chen, X.; Gođevac, D.; Bueno, P.C.P.; Salomé Abarca, L.F.; Jang, Y.P.; Wang, M.; Choi, Y.H. Metabolic profiling of saponin-rich Ophiopogon japonicus roots based on 1H NMR and HPTLC platforms. Planta Med. 2019, 85, 917–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nafti, K.; Giacinti, G.; Marghali, S.; Delgado Raynaud, C. Screening for Astragalus hamosus Triterpenoid Saponins Using HPTLC Methods: Prior Identification of Azukisaponin Isomers. Molecules 2022, 27, 5376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oleszek, W. Chromatographic determination of plant saponins. J. Chromatogr. A 2002, 967, 147–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Ma, Y.; Xu, Q.; Shikov, A.N.; Pozharitskaya, O.N.; Flisyuk, E.V.; Liu, M.; Li, H.; Vargas-Murga, L.; Duez, P. Flavonoids and Saponins: What Have We got or Missed? Phytomedicine 2023, 109, 154580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Podolak, I.; Grabowska, K.; Sobolewska, D.; Wróbel-Biedrawa, D.; Makowska-Wąs, J.; Galanty, A. Saponins as Cytotoxic Agents: AN Update (2010–2021). Part II—Triterpene Saponins. Phytochem. Rev. 2023, 22, 113–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obadoni, B.O.; Ochuko, P.O. Phytochemical studies and comparative efficacy of the crude extracts of some haemostatic plants in Edo and Delta States of Nigeria. Glob. J. Pure Appl. Sci. 2001, 8, 203–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Wang, S.; Wan, F.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, Z.; Fan, G.; Wang, P.; Luo, H.; Liao, S.; He, L. Quantitative analysis of Camellia oleifera seed saponins and aqueous two-phase extraction and separation. Molecules 2023, 28, 2132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshmukh, A.G.; Pawar, A.R.; Tapre, V.V.; Parmar, J.N.; Deshmukh, K.M. Comparison of gravimetric method with the colorimetric method for saponin content in Safed Musli (Chlorophytum borivilianum). Int. J. Hortic. Food Sci. 2019, 1, 17–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sechium | Fruit Mass (kg) | Aqueous Extract | Hydroalcoholic Extract | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Juice (g) | Lyophilized Juice (g) | % Yield a | Bagasse Extract (g) | Lyophilized Bagasse (g) | % Yield b | Dry Bagasse Residue c (g) | ||

| 633-M11 | 5.7 | 2144.0 | 215.2 | 10.03 | 2573.2 | 62.3 | 2.42 | 695 |

| 387-M16 | 5.2 | 3728.0 | 136.1 | 3.65 | 2457.9 | 176.9 | 7.19 | 635 |

| Sechium | Matrix | Mass of Crude Saponins (g g−1) | Gravimetric Yield (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Method 1 | Method 2 | Method 3 | Method 1 | Method 2 | Method 3 | ||

| 633-M11 | Juice | 0.211 | 0.303 | 0.299 | 21.1 ± 8.6 | 30.3 ± 0.7 | 29.9 ± 10.1 |

| Bagasse | 0.269 | 0.109 | 0.446 | 26.9 ± 1.7 | 10.9 ± 1.9 | 44.6 ± 2.2 | |

| 387-M16 | Juice | 0.216 | 0.240 | 0.328 | 21.6 ± 5.6 | 24.0 ± 4.3 | 32.8 ± 8.7 |

| Bagasse | 0.465 | 0.106 | 0.606 | 46.5 ± 10.4 | 13.5 ± 1.8 | 60.6 ± 4.9 | |

| Sechium Genotype | Matrix | Saponins (mg g−1) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Totals 600 nm | Steroidal 425 nm | Triterpenic 600–425 nm | ||

| 387-M16 | Bagasse | 86.92 ± 0.88 | 41.45 ± 2.55 | 45.48 ± 1.74 |

| Juice | 82.24 ± 1.28 | 45.33 ± 0.47 | 36.91 ± 1.67 | |

| 633-M11 | Bagasse | 73.17 ± 2.33 | 31.22 ± 0.45 | 41.95 ± 1.89 |

| Juice | 70.20 ± 3.78 | 52.96 ± 2.83 | 17.24 ± 0.96 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Rasgado-Bonilla, F.A.; Soto-Hernández, R.M.; Salomé-Abarca, L.F.; Cadena-Íñiguez, J.; González-Hernández, V.A.; Ruiz-Posadas, L.d.M.; Herrera-Rodríguez, S.E. Comparison of Methods for the Extraction of Saponins from Sechium spp. Genotypes and Their Spectrophotometric Quantification. Separations 2026, 13, 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/separations13010029

Rasgado-Bonilla FA, Soto-Hernández RM, Salomé-Abarca LF, Cadena-Íñiguez J, González-Hernández VA, Ruiz-Posadas LdM, Herrera-Rodríguez SE. Comparison of Methods for the Extraction of Saponins from Sechium spp. Genotypes and Their Spectrophotometric Quantification. Separations. 2026; 13(1):29. https://doi.org/10.3390/separations13010029

Chicago/Turabian StyleRasgado-Bonilla, Fátima Azucena, Ramón Marcos Soto-Hernández, Luis Francisco Salomé-Abarca, Jorge Cadena-Íñiguez, Víctor A. González-Hernández, Lucero del Mar Ruiz-Posadas, and Sara Elisa Herrera-Rodríguez. 2026. "Comparison of Methods for the Extraction of Saponins from Sechium spp. Genotypes and Their Spectrophotometric Quantification" Separations 13, no. 1: 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/separations13010029

APA StyleRasgado-Bonilla, F. A., Soto-Hernández, R. M., Salomé-Abarca, L. F., Cadena-Íñiguez, J., González-Hernández, V. A., Ruiz-Posadas, L. d. M., & Herrera-Rodríguez, S. E. (2026). Comparison of Methods for the Extraction of Saponins from Sechium spp. Genotypes and Their Spectrophotometric Quantification. Separations, 13(1), 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/separations13010029