The Reaction to Diagnosis Questionnaire—Sibling Version: A Preliminary Study on the Psychometric Properties

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Measure for Assessing the Reaction to the Diagnosis Process

1.2. Aims of the Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Back-Translation and Adaptation of the RDQ-S

2.2. Measures

2.3. Study Design

2.4. Participants

2.5. Statistical Plan

3. Results

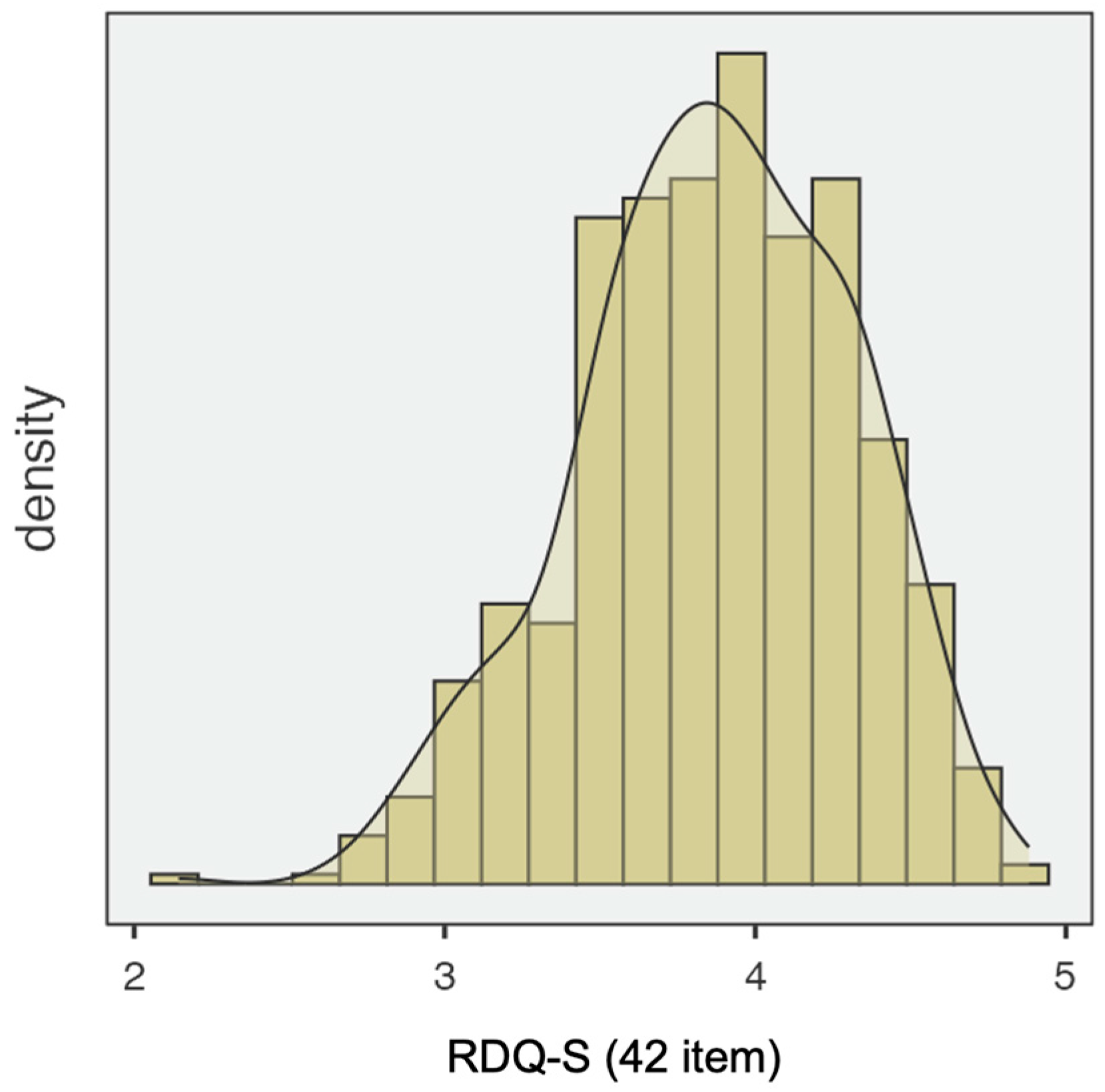

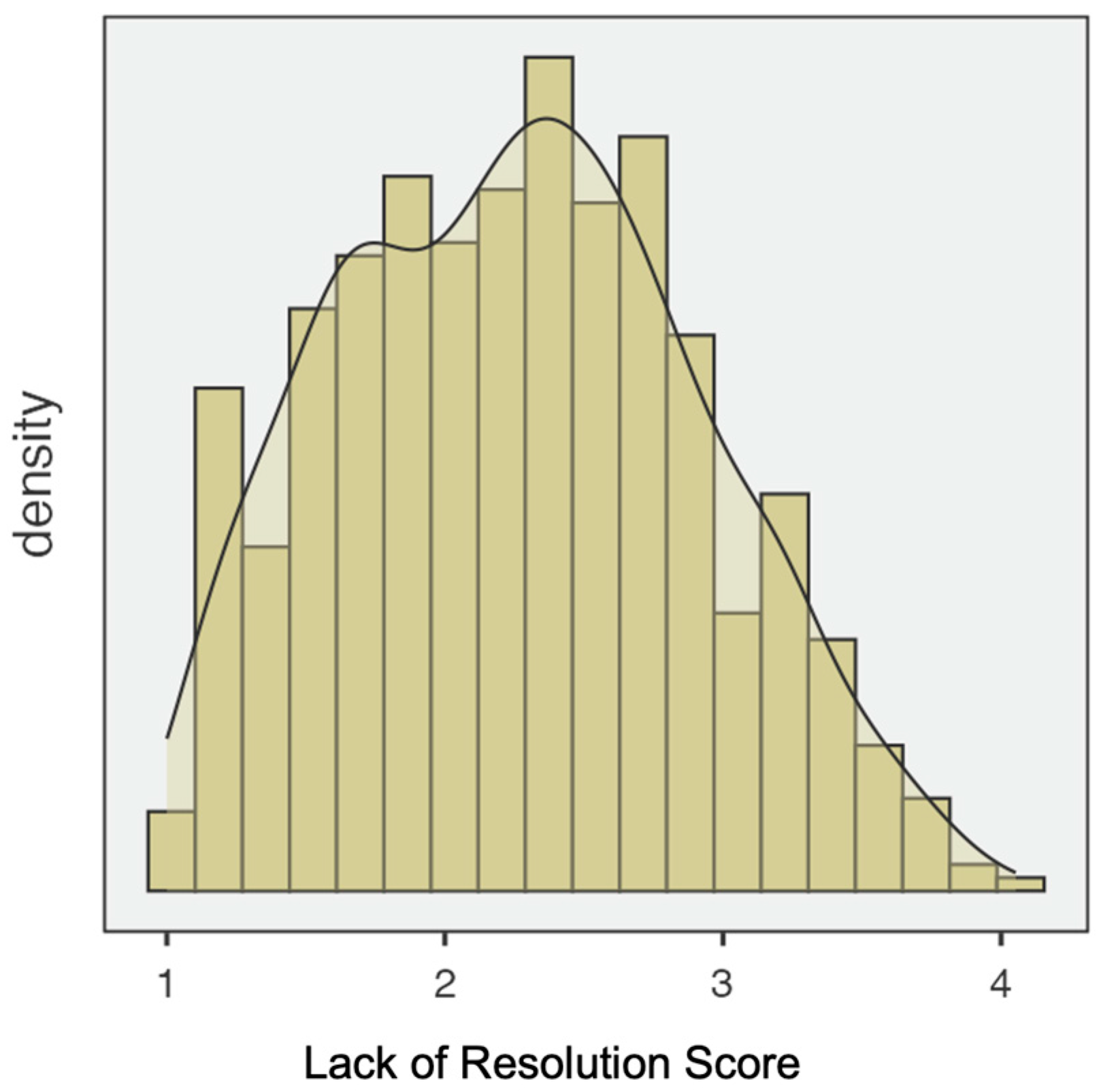

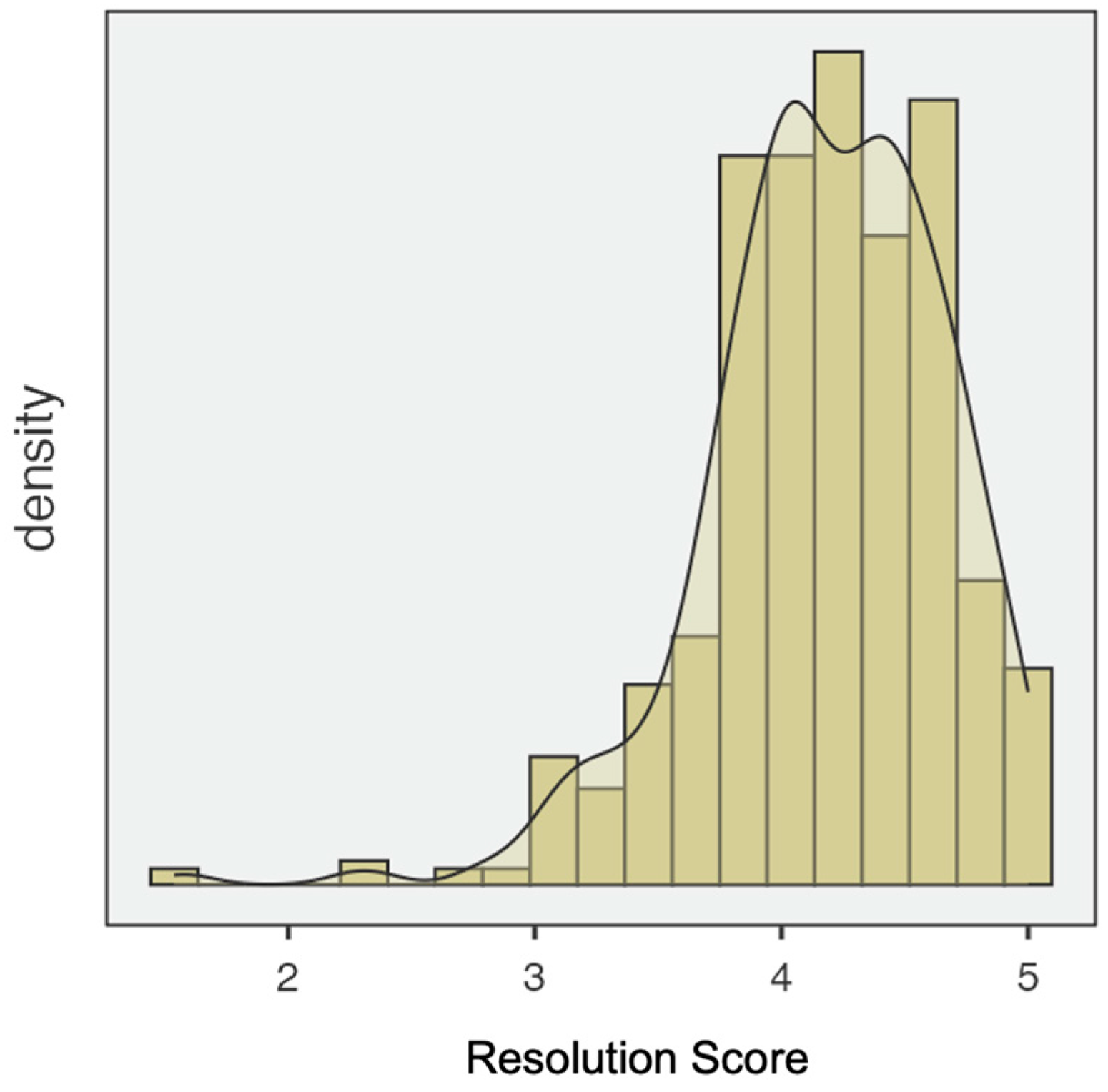

3.1. Preliminary and Descriptive Analyses

3.2. Exploratory Factor Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Strengths, Limitations, and Future Directions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ashori, M. (2025). Adjustment and relationships between adolescents of typically developing siblings, deaf siblings, and blind siblings. Current Psychology, 44, 2895–2906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auyeung, T. W., Kwok, T., Lee, J., Leung, P. C., Leung, J., & Woo, J. (2008). Functional decline in cognitive impairment–the relationship between physical and cognitive function. Neuroepidemiology, 31(3), 167–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backer van Ommeren, T., Koot, H. M., & Begeer, S. (2017). Reciprocity in autistic and typically developing children and adolescents with and without mild intellectual disabilities. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 61(8), 810–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaton, D. E., Bombardier, C., Guillemin, F., & Ferraz, M. B. (2000). Guidelines for the process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures. Spine, 25(24), 3186–3191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowlby, J. (1982). Attachment and loss: Retrospect and prospect. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 52, 664–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braconnier, M. L., Coffman, M. C., Kelso, N., & Wolf, J. M. (2018). Sibling relationships: Parent–child agreement and contributions of siblings with and without ASD. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 48, 1612–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brislin, R. W. (1970). Back-translation for cross-cultural research. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 1(3), 185–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brolin, R., Hanson, E., Magnusson, L., Lewis, F., Parkhouse, T., Hlebec, V., Santini, S., Hoefman, R., Leu, A., & Becker, S. (2024). Adolescent young carers who provide care to siblings. Healthcare, 12(3), 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camargo, S. P. H., Rispoli, M., Ganz, J., Hong, E. R., Davis, H., & Mason, R. (2014). A review of the quality of behaviorally-based intervention research to improve social interaction skills of children with ASD in inclusive settings. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 44, 2096–2116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cervellione, B., Iacolino, C., Bottari, A., Vona, C., Leuzzi, M., & Presti, G. (2025). Functioning of neurotypical siblings of individuals with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review. Psychiatry International, 6(2), 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, C. Y. (2022). Bamboo sibs: Experiences of Taiwanese non-disabled siblings of adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities across caregiver lifestages. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities, 34, 233–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Church, C., Patil, S., Butler, S., Miller, F., Salazar-Torres, J. J., Lennon, N., Shrader, M. W., Donohoe, M., Kalisperis, F., Mackenzie, W. G. S., & Nichols, L. R. (2025). Health-related quality of life of individuals with physical disabilities in childhood. Children, 12(3), 365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Carlo, E., Martis, C., Lecciso, F., Levante, A., Signore, F., & Ingusci, E. (2024). Acceptance of disability as a protective factor for emotional exhaustion: An empirical study on employed and unemployed persons with disabilities. Psicologia Sociale, 2, 235–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Cagno, L., Gandione, M., & Massaglia, P. (1992). Il contenimento delle angosce come momento terapeutico. In G. Fava Vizziello, & D. N. Stern (Eds.), Dalle cure materne all’interpretazione. Raffaello Cortina. [Google Scholar]

- Dorsman, N. I., Waninge, A., van der Schans, C. P., Luijkx, J., & Van der Putten, A. A. (2023). The roles of adult siblings of individuals with a profound intellectual disability. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 36(6), 1308–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giallo, R., & Gavidia-Payne, S. (2006). Child, parent and family factors as predictors of adjustment for siblings of children with a disability. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 50(12), 937–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gudmundsson, E. (2009). Guidelines for translating and adapting psychological instruments. Nordic Psychology, 61(2), 29–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guidotti, L., Musetti, A., Barbieri, G. L., Ballocchi, I., & Corsano, P. (2021). Conflicting and harmonious sibling relationships of children and adolescent siblings of children with autism spectrum disorder. Child: Care, Health and Development, 47(2), 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hastings, R. P. (2003). Brief report: Behavioral adjustment of siblings of children with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 33(1), 99–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutman, T., Siller, M., & Sigman, M. (2009). Mothers’ narratives regarding their child with autism predict maternal synchronous behavior during play. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 50, 1255–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaminsky, L., & Dewey, D. (2001). Siblings relationships of children with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 31, 399–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, M. A., Yi, J., Hwang, S., Sung, J., Lee, S. Y., & Kim, H. (2025). Narratives from female siblings of adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities: A photovoice study on identity and growth experiences in South Korea. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 38(2), e70029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kübler-Ross, E. (1970). The care of the dying—Whose job is it? Psychiatry and Medicine, 1, 103–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lecciso, F., Martis, C., Antonioli, G., & Levante, A. (2025a). The impact of the reaction to diagnosis on sibling relationship: A study on parents and adult siblings of people with disabilities. Frontiers in Psychology, 16, 1551953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lecciso, F., Martis, C., Del Prete, C. M., Martino, P., Primiceri, P., & Levante, A. (2025b). Determinants of sibling relationships in the context of mental disorders. PLoS ONE, 20(4), e0322359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lecciso, F., Petrocchi, S., & Marchetti, A. (2013a). Hearing mothers and oral deaf children: An atypical relational context for theory of mind. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 28, 903–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lecciso, F., Petrocchi, S., Savazzi, F., Marchetti, A., Nobile, M., & Molteni, M. (2013b). The association between maternal resolution of the diagnosis of autism, maternal mental representations of the relationship with the child, and children’s attachment. Life Span and Disability, 16, 21–38. [Google Scholar]

- Levante, A., Martis, C., Del Prete, C. M., Martino, P., Pascali, F., Primiceri, P., Vergari, M., & Lecciso, F. (2023). Parentification, distress, and relationship with parents as factors shaping the relationship between adult siblings and their brother/sister with disabilities. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 13, 1079608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levante, A., Martis, C., Del Prete, C. M., Martino, P., Primiceri, P., & Lecciso, F. (2024). Siblings of persons with disabilities: A systematic integrative review of the empirical literature. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 28, 209–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levante, A., Petrocchi, S., & Lecciso, F. (2020). The criterion validity of the first year inventory and the quantitative-checklist for autism in toddlers: A longitudinal study. Brain Sciences, 10(10), 729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahoney, F. I., & Barthel, D. W. (1965). Functional evaluation: The Barthel index: A simple index of independence useful in scoring improvement in the rehabilitation of the chronically ill. Maryland State Medical Journal, 14, 61–65. [Google Scholar]

- Main, M., & Hesse, E. (1990). Parents’ unresolved traumatic experiences are related to infant disorganized attachment status: Is frightened/frightening parental behavior the linking mechanism? In M. T. Greenberg, D. Cicchetti, & E. M. Cummings (Eds.), Attachment in the preschool years: Theory, research, and intervention (pp. 161–182). University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Martis, C., Levante, A., De Carlo, E., Ingusci, E., Signore, F., & Lecciso, F. (2024). The power of acceptance of their disability for improving flourishing: Preliminary insights from persons with physical acquired disabilities. Disabilities, 4(4), 815–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marvin, R. S., & Pianta, R. C. (1996). Mothers’ reactions to their child’s diagnosis: Relations with security of attachment. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 25(4), 436–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milshtein, S., Yirmiya, N., Oppenheim, D., Koren-Karie, N., & Levi, S. (2010). Resolution of the diagnosis among parents of children with autism spectrum disorder: Associations with child and parent characteristics. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 40, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgan, G. A., Leech, N. L., Gloeckner, G. W., & Barrett, K. C. (2004). SPSS for introductory statistics: Use and interpretation. Psychology Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyson, T., & Roeyers, H. (2012). ‘The overall quality of my life as a sibling is all right, but of course, it could always be better’: Quality of life of siblings of children with intellectual disability: The siblings’ perspectives. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 56(1), 87–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naicker, V. V., Hedley, D., & Bury, S. M. (2024). Does hope mediate the relationship between parent’s resolution of their child’s autism diagnosis and parental stress? Frontiers in Psychology, 15, 1443707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Neill, L. P., & Murray, L. E. (2016). Anxiety and depression symptomatology in adult siblings of individuals with different developmental disability diagnoses. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 51–52, 116–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oppenheim, D., Koren-Karie, N., Dolev, S., & Yirmiya, N. (2009). Maternal insightfulness and resolution of the diagnosis are associated with secure attachment in preschoolers with autism spectrum disorders. Child Development, 80(2), 519–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opperman, S., & Alant, E. (2003). The coping responses of the adolescent siblings of children with severe disabilities. Disability and Rehabilitation, 25(9), 441–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petalas, M. A., Hastings, R. P., Nash, S., Lloyd, T., & Dowey, A. (2009). Emotional and behavioural adjustment in siblings of children with intellectual disability with and without autism. Autism, 13(5), 471–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pianta, R. C., Marvin, R. S., & Morog, M. C. (1999). Resolving the past and present: Relations with attachment organization. In J. Solomon, & C. George (Eds.), Attachment disorganization (pp. 379–398). The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pilowsky, T., Yirmiya, N., Doppelt, O., Gross-Tsur, V., & Shalev, R. S. (2004). Social and emotional adjustment of siblings of children with autism. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 45(4), 855–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poslawsky, I. E., Naber, F. B. A., Van Daalen, E., & Van Engeland, H. (2014). Parental reaction to early diagnosis of their children’s autism spectrum disorder: An exploratory study. Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 45(3), 294–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Regmi, K., Naidoo, J., & Pilkington, P. (2010). Understanding the processes of translation and transliteration in qualitative research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 9(1), 16–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossetti, Z., & Hall, S. (2015). Adult sibling relationships with brothers and sisters with severe disabilities. Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities, 40(2), 120–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, P. E., Clements, M., & Poehlmann, J. (2011). Maternal resolution of grief after preterm birth: Implications for infant attachment security. Pediatrics, 127(2), 284–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharpe, D., & Rossiter, L. (2002). Siblings of children with a chronic illness: A meta-analysis. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 27(8), 699–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sher-Censor, E., Dan Ram-On, T., Rudstein-Sabbag, L., Watemberg, M., & Oppenheim, D. (2019). The reaction to diagnosis questionnaire: A preliminary validation of a new self-report measure to assess parents’ resolution of their child’s diagnosis. Attachment & Human Development, 22(4), 409–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sher-Censor, E., Harel, M., Oppenheim, D., & Aran, A. (2024). Parental representations and emotional availability: The case of children with autism and severe behavior problems. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sher-Censor, E., & Shahar-Lahav, R. (2022). Parents’ resolution of their child’s diagnosis: A scoping review. Attachment & Human Development, 24(5), 580–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takataya, K., Mizuno, E., Kanzaki, Y., Sakai, I., & Yamazaki, Y. (2019). Feelings of siblings having a brother/sister with down syndrome. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 33(4), 337–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Jamovi Project. (2024). Jamovi (Version 2.6.26) [Computer software]. Available online: https://www.jamovi.org (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Tomeny, T. S., Barry, T. D., & Fair, E. C. (2017). Parentification of adult siblings of individuals with autism spectrum disorder: Distress, sibling relationship attitudes, and the role of social support. Journal of Intellectual & Developmental Disability, 42(4), 320–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Travers, H. E., Carlton, M. E., & Carter, E. W. (2020). Social connections among siblings with and without intellectual disability or autism. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 58(1), 19–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, P., Piamjariyakul, U., Carolyn Graff, J., Stanton, A., Guthrie, A. C., Hafeman, C., & Williams, A. R. (2010). Developmental Disabilities: Effects on well siblings. Issues in Comprehensive Pediatric Nursing, 33(1), 39–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yaldiz, A. H., Solak, N., & Ikizer, G. (2021). Negative emotions in siblings of individuals with developmental disabilities: The roles of early maladaptive schemas and system justification. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 117, 104046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youngstrom, E. A. (2013). A primer on receiver operating characteristic analysis and diagnostic efficiency statistics for pediatric psychology: We are ready to ROC. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 39(2), 204–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Educational Level | |

| TD siblings of individuals with NDD | Low (up to 8 years of education) = 13% Intermediate (up to 13 years of education) = 60% High (13 or more years of education) = 27% |

| Individuals with NDD | No formal education = 15% Low (up to 8 years of education) = 32% Intermediate (up to 13 years of education) = 52% High (13 or more years of education) = 1% |

| TD siblings of individuals with physical disability | Low (up to 8 years of education) = 12% Intermediate (up to 13 years of education) = 66% High (13 or more years of education) = 22% |

| Individuals with physical disability | No formal education = 8% Low (up to 8 years of education) = 30% Intermediate (up to 13 years of education) = 56% High (13 or more years of education) = 6% |

| Marital status | |

| TD siblings of individuals with NDD | With a partner = 13.50% Without a partner = 86.50% |

| Individuals with NDD | With a partner = 5% Without a partner = 95% |

| TD siblings of individuals with physical disability | With a partner = 23% Without a partner = 77% |

| Individuals with physical disability | With a partner = 9% Without a partner = 91% |

| Employment status | |

| TD siblings of individuals with NDD | Employed = 41% Unemployed = 59% |

| Individuals with NDD | Employed = 10% Unemployed = 90% |

| TD siblings of individuals with physical disability | Employed = 55% Unemployed = 45% |

| Individuals with physical disability | Employed = 18% Unemployed = 82% |

| Sibship | |

| Older vs. younger TD siblings of individuals with NDD | Older TD sibling = 61% Younger TD sibling = 39% |

| Older vs. younger TD siblings of individuals with physical disability | Older TD sibling = 58% Younger TD sibling = 42% |

| TD Sibling Sex | Brother/Sister Type of Disability | TD Sibling Sibship | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TD Sisters M (SD) | TD Brothers M (SD) | U; p | NDDs M (SD) | PDs M (SD) | U; p | Older M (SD) | Younger M (SD) | U; p | |

| TD Sibling Resolution Score | 3.86 (0.43) | 3.86 (0.45) | 1.654; 0.78 | 3.87 (0.41) | 3.85 (0.46) | 4.650; 0.77 | 3.85 (0.45) | 3.89 (0.42) | 4.475 (0.31) |

| FACTOR | ||

|---|---|---|

| Lack of Resolution | Resolution | |

| 28. It is difficult for me to stop thinking about my brother/sister’s diagnosis and difficulties. (r) | 0.766 | |

| 26. I am angry about everything that happened to my brother/sister and me. (r) | 0.734 | |

| 30. I keep asking myself why this happened to me. (r) | 0.732 | |

| 5. I am still upset regarding the way my brother/sister was diagnosed. (r) | 0.727 | |

| 22. There isn’t a day in which I don’t think about the amount and type of treatments and interventions my brother/sister receives. | 0.670 | |

| 19. Whenever I think about my brother/sister, I feel despair or sadness. (r) | 0.662 | |

| 4. I often think why my brother/sister has this diagnosis. (r) | 0.640 | |

| 14. Since I am aware of my brother/sister’s diagnosis, it is difficult for me to function in day-to-day life. (r) | 0.630 | |

| 15. I am preoccupied with searching for reasons for my brother/sister’s difficulties. (r) | 0.623 | |

| 31. I am very concerned about my brother/sister’s future. (r) | 0.581 | |

| 32. Since I found out about my brother/sister’s diagnosis, I feel powerless and there is no joy in my life. (r) | 0.562 | |

| 13. I am preoccupied with thinking and asking what I did wrong so that this has happened to me, that I have a brother/sister with special needs. (r) | 0.549 | |

| 23. I feel very confused about my brother/sister’s diagnosis. (r) | 0.511 | |

| 9. When I think about having a brother/sister with special needs, I feel guilty. (r) | 0.509 | |

| 37. I continue to take my brother/sister to receive additional medical opinions about her/his diagnosis. (r) | 0.491 | |

| 25. I remember every detail of the moment I found out my brother/sister’s diagnosis as if it were yesterday. (r) | 0.474 | 0.350 |

| 10. It is difficult for me to treat my brother/sister as a “typical” person. (r) | 0.394 | −0.351 |

| 6. I want to treat my brother/sister like any other brother/sister, but I am not successful in doing so. (r) | 0.378 | |

| 24. I feel that my brother/sister suffers because of me. (r) | 0.375 | |

| 34. I am still angry regarding the way my brother/sister’s diagnosis was given to me. (r) | 0.309 | |

| 21. I believe that the diagnosis my brother/sister received is incorrect. (r) | 0.303 | |

| 41. I think that I or someone in my family could have prevented the development of my brother/sister’s condition. (r) | ||

| 35. My brother/sister’s diagnosis did not change my life or the life of my family. (r) | ||

| 39. Today I can see my brother/sister’s difficulties as well as her/his strengths and achievements. | 0.713 | |

| 40. My brother/sister has characteristics and abilities that I love very much. | 0.683 | |

| 7. In spite of the difficulties, I see that my brother/sister is successful in facing his/her challenges. | 0.673 | |

| 29. When I think about my brother/sister’s future, I believe his/her life will be happy. | 0.622 | |

| 27. My brother/sister has enriched my life by being a brother/sister with special needs. | 0.616 | |

| 17. I believe that my family and I can cope with my brother/sister’s difficulties and help him/her. | 0.598 | |

| 16. I see that the treatments and interventions help my brother/sister. | 0.533 | |

| 33. My brother/sister is in an educational setting that is appropriate to his/her needs and abilities. | 0.524 | |

| 3. When I plan the interventions my brother/sister will receive, the most important thing for me is that he/she will be happy. | 0.514 | |

| 8. I feel that my brother/sister’s condition is improving. | 0.512 | |

| 38. I hope that my brother/sister’s condition will improve with time. | 0.454 | |

| 12. I am confident that my brother/sister would soon close the gap and be like any other typically developing person. (r) | 0.453 | |

| 36. I do not enjoy playing/spending time with my brother/sister. (r) | −0.426 | |

| 20. I feel that I lost the brother/sister I hoped to have. (r) | 0.377 | −0.416 |

| 1. I shared my brother/sister’s diagnosis with my extended family. | 0.405 | |

| 18. I don’t believe that my brother/sister’s level of independence will improve in the future. (r) | −0.361 | |

| 42. I feel that my feelings regarding my brother/sister’s diagnosis have changed since I found out about my brother/sister’s diagnosis. | 0.361 | |

| 11. I am very dissatisfied with the treatment my brother/sister is receiving. (r) | ||

| 2. I believe that my brother/sister’s diagnosis is incorrect. (r) | ||

| TD Sibling Sex | Brother/Sister Type of Disability | TD Sibling Sibship | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TD Sisters M (SD) | TD Brothers M (SD) | U; p | NDDs M (SD) | PDs M (SD) | U; p | Older M (SD) | Younger M (SD) | U; p | |

| Lack of Resolution | 2.27 (0.64) | 2.25 (0.66) | 4.5570; 0.47 | 2.25 (0.61) | 2.27 (0.67) | 4.6997; 0.094 | 2.29 (0.66) | 2.22 (0.063) | 4.4341; 0.23 |

| Resolution | 4.18 (0.49) | 4.15 (0.49) | 4.5721; 0.52 | 4.19 (0.48) | 4.15 (0.49) | 4.5554; 0.47 | 4.16 (0.51) | 4.17 (0.45) | 4.6667; 0.88 |

| Factor | M (SD) | Cronbach’s α | McDonald’s ω |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lack of Resolution | 2.26 (0.65) | 0.911 | 0.914 |

| Resolution | 4.17 (0.49) | 0.846 | 0.856 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the University Association of Education and Psychology. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Martis, C.; Levante, A.; Lecciso, F. The Reaction to Diagnosis Questionnaire—Sibling Version: A Preliminary Study on the Psychometric Properties. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2025, 15, 147. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15080147

Martis C, Levante A, Lecciso F. The Reaction to Diagnosis Questionnaire—Sibling Version: A Preliminary Study on the Psychometric Properties. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education. 2025; 15(8):147. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15080147

Chicago/Turabian StyleMartis, Chiara, Annalisa Levante, and Flavia Lecciso. 2025. "The Reaction to Diagnosis Questionnaire—Sibling Version: A Preliminary Study on the Psychometric Properties" European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education 15, no. 8: 147. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15080147

APA StyleMartis, C., Levante, A., & Lecciso, F. (2025). The Reaction to Diagnosis Questionnaire—Sibling Version: A Preliminary Study on the Psychometric Properties. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 15(8), 147. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15080147