Clarity and Emotional Regulation as Protective Factors for Adolescent Well-Being: A Moderated Mediation Model Involving Depression

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Measurements

2.4. Procedure

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Bivariate Correlations Between Variables

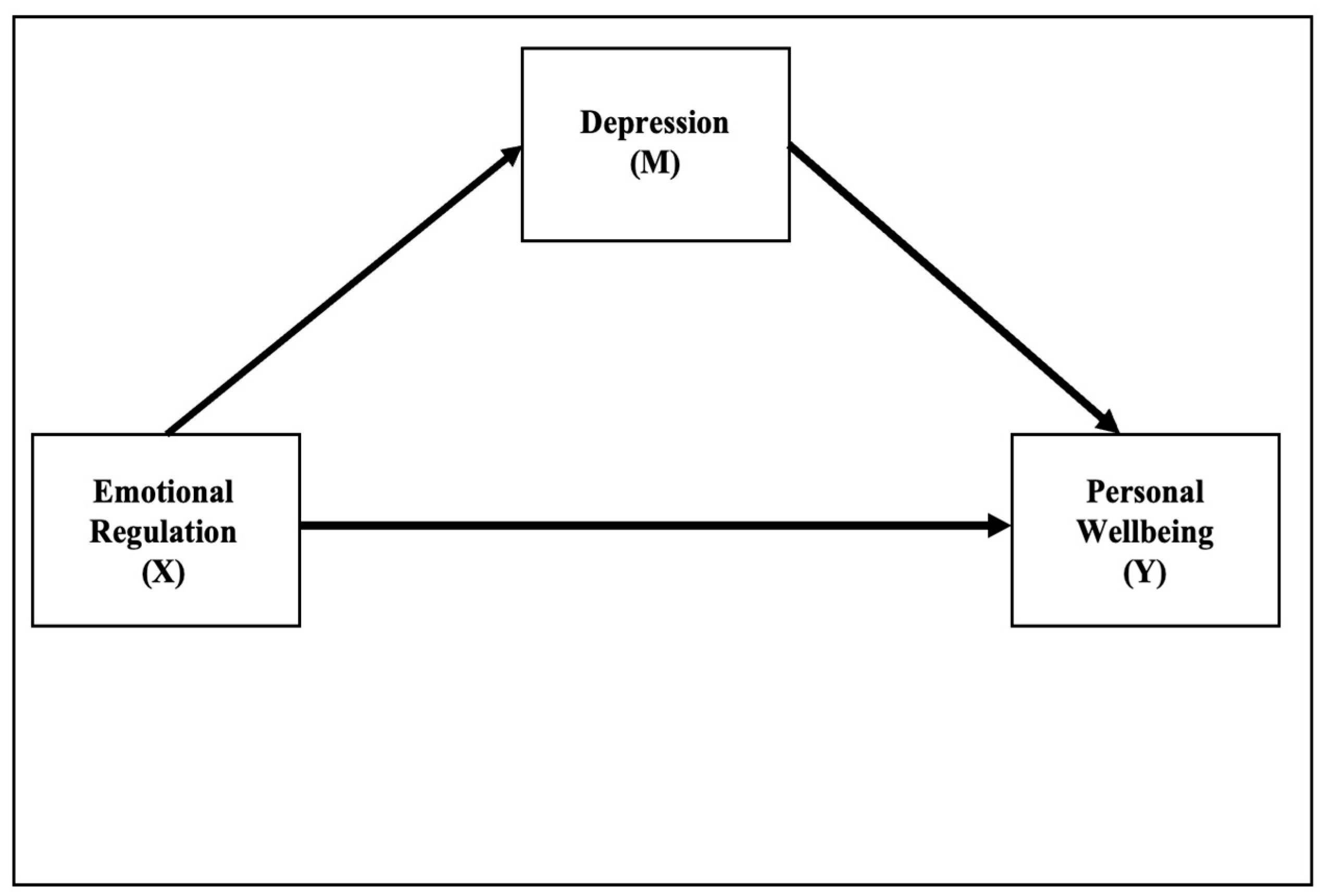

3.2. Mediation Analyses

3.3. Moderated Mediation Analyses

3.4. Simple Slope Test and J-N Technique Analysis of the Moderating Effect of Emotional Clarity

4. Discussion

4.1. Total Effects of Emotional Regulation on Subjective Well-Being

4.2. Mediation of Depression in the Relationship Between Emotional Regulation and Subjective Well-Being

4.3. Moderating Effect of Emotional Clarity Between Emotional Regulation and Depression

4.4. Limitations

4.5. Future Studies

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aldao, A., Nolen-Hoeksema, S., & Schweizer, S. (2010). Emotion-regulation strategies across psychopathology: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 30(2), 217–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antúnez, Z., & Vinet, E. V. (2012). Escalas de depresión, ansiedad y estrés (DASS-21): Validación de la versión abreviada en estudiantes universitarios Chilenos. Terapia Psicologica, 30(3), 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azpiazu Izaguirre, L., Fernández, A. R., & Palacios, E. G. (2021). Adolescent life satisfaction explained by social support, emotion regulation, and resilience. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 694183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barahona-Fuentes, G., Huerta Ojeda, Á., Romero, G. L., Delgado-Floody, P., Jerez-Mayorga, D., Yeomans-Cabrera, M. M., & Chirosa-Ríos, L. J. (2023). Muscle quality index is inversely associated with psychosocial variables among Chilean adolescents. BMC Public Health, 23(1), 2104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barahona-Fuentes, G. D., Lagos, R. S., & Ojeda, Á. C. H. (2019). Influencia del autodiálogo sobre los niveles de ansiedad y estrés en jugadores de tenis: Una revisión sistemática. Revista Brasileira de Ciências Do Esporte, 41, 135–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, A. T., Rush, A. J., Shaw, B. F., & Emery, G. (1979). Cognitive therapy of depression. Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Boden, M. T., Thompson, R. J., Dizén, M., Berenbaum, H., & Baker, J. P. (2013). Are emotional clarity and emotion differentiation related? Cognition & Emotion, 27(6), 961–978. [Google Scholar]

- Carl, J. R., Soskin, D. P., Kerns, C., & Barlow, D. H. (2013). Positive emotion regulation in emotional disorders: A theoretical review. Clinical Psychology Review, 33(3), 343–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cejudo, J., Losada, L., & Feltrero, R. (2020). Promoting social and emotional learning and subjective well-being: Impact of the “aislados” intervention program in adolescents. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(2), 609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cianconi, P., Hanife, B., Hirsch, D., & Janiri, L. (2023). Is climate change affecting mental health of urban populations? Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 36(3), 213–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compas, B. E., & Wagner, B. M. (2017). Psychosocial stress during adolescence: Intrapersonal and interpersonal processes. In Adolescent stress (pp. 67–86). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, D., Yap, K., & Batalha, L. (2018). Mindfulness-based interventions and their effects on emotional clarity: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 235, 265–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crego, A., Yela, J. R., Gómez-Martínez, M. Á., Sánchez-Zaballos, E., & Vicente-Arruebarrena, A. (2025). Long-term effectiveness of the Mindful Self-Compassion programme compared to a Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction intervention: A quasi-randomised controlled trial involving regular mindfulness practice for 1 year. Frontiers in Psychology, 16, 1597264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Domitrovich, C. E., Durlak, J. A., Staley, K. C., & Weissberg, R. P. (2017). Social-emotional competence: An essential factor for promoting positive adjustment and reducing risk in school children. Child Development, 88(2), 408–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dryman, M. T., & Heimberg, R. G. (2018). Emotion regulation in social anxiety and depression: A systematic review of expressive suppression and cognitive reappraisal. Clinical Psychology Review, 65, 17–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Džida, M., Babarović, T., & Brajša-Žganec, A. (2023). The factor structure of different subjective well-being measures and its correlates in the Croatian sample of children and adolescents. Child Indicators Research, 16(5), 1871–1888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckland, N. S., & Thompson, R. J. (2023). State emotional clarity is an indicator of fluid emotional intelligence ability. Journal of Intelligence, 11(10), 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenstadt, M., Liverpool, S., Infanti, E., Ciuvat, R. M., & Carlsson, C. (2021). Mobile apps that promote emotion regulation, positive mental health, and well-being in the general population: Systematic review and meta-analysis. JMIR Mental Health, 8(11), e31170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everaert, J., & Joormann, J. (2020). Emotion regulation habits related to depression: A longitudinal investigation of stability and change in repetitive negative thinking and positive reappraisal. Journal of Affective Disorders, 276, 738–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Extremera, N., & Fernández-Berrocal, P. (2006). Emotional intelligence as predictor of mental, social, and physical health in university students. The Spanish Journal of Psychology, 9(1), 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Extremera, N., & Rey, L. (2015). The moderator role of emotion regulation ability in the link between stress and well-being. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Berrocal, P., Extremera, N., & Ramos, N. (2004). Validity and reliability of the Spanish modified version of the Trait Meta-Mood Scale. Psychological Reports, 94(3), 751–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flynn, M., & Rudolph, K. D. (2010). The contribution of deficits in emotional clarity to stress responses and depression. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 31(4), 291–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flynn, M., & Rudolph, K. D. (2014). A prospective examination of emotional clarity, stress responses, and depressive symptoms during early adolescence. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 34(7), 923–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca-Pedrero, E., Ortuño-Sierra, J., & Pérez-Albéniz, A. (2020). Dificultades emocionales y conductuales y comportamiento prosocial en adolescentes: Un análisis de perfiles latentes. Revista de Psiquiatría y Salud Mental, 13(4), 202–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giménez-Espert, M. D. C., & Prado-Gascó, V. J. (2018). The role of empathy and emotional intelligence in nurses’ communication attitudes using regression models and fuzzy-set qualitative comparative analysis models. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 27(13–14), 2661–2672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gohm, C. L., & Clore, G. L. (2002). Four latent traits of emotional experience and their involvement in well-being, coping, and attributional style. Cognition & Emotion, 16(4), 495–518. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-Restrepo, C., Diez-Canseco, F., Brusco, L. I., Acosta, M. P. J., Olivar, N., Carbonetti, F. L., Hidalgo-Padilla, L., Toyama, M., Uribe-Restrepo, J. M., Malagon, N. R., Niño-Torres, D., Casasbuenas, N. G., Sureshkumar, D. S., Fung, C., Bird, V., Morgan, C., Araya, R., Kirkbride, J., & Priebe, S. (2025). Mental distress among youths in low-income urban areas in South America. JAMA Network Open, 8(3), e250122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Romero, M. J., Limonero, J. T., Trallero, J. T., Montes-Hidalgo, J., & Tomás-Sábado, J. (2018). Relación entre inteligencia emocional, afecto negativo y riesgo suicida en jóvenes universitarios. Ansiedad y Estrés, 24(1), 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gratz, K. L., & Roemer, L. (2004). Multidimensional assessment of emotion regulation and dysregulation: Development, factor structure, and initial validation of the difficulties in emotion regulation scale. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 26, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, J. J. (1998). The emerging field of emotion regulation: An integrative review. Review of General Psychology, 2(3), 271–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, J. J. (1999). Emotion regulation: Past, present, future. Cognition & Emotion, 13(5), 551–573. [Google Scholar]

- Gross, J. J. (2015). The extended process model of emotion regulation: Elaborations, applications, and future directions. Psychological Inquiry, 26(1), 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, J. J., & Jazaieri, H. (2014). Emotion, emotion regulation, and psychopathology: An affective science perspective. Clinical Psychological Science, 2(4), 387–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerra-Bustamante, J., León-del-Barco, B., Yuste-Tosina, R., López-Ramos, V. M., & Mendo-Lázaro, S. (2019). Emotional intelligence and psychological well-being in adolescents. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(10), 1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haas, L. M., McArthur, B. A., Burke, T. A., Olino, T. M., Abramson, L. Y., & Alloy, L. B. (2019). Emotional clarity development and psychosocial outcomes during adolescence. Emotion, 19(4), 563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, A. F. (2017). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. Guilford Publications. [Google Scholar]

- IBM Corp. (2025). IBM SPSS. In IBM SPSS statistics for macintosh. IBM Corp. [Google Scholar]

- Kendler, K. S. (2016). The phenomenology of major depression and the representativeness and nature of DSM criteria. American Journal of Psychiatry, 173(8), 771–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kent, M. (2003). Diccionario Oxford de medicina y ciencias del deporte (Vol. 44). Editorial Paidotribo. [Google Scholar]

- Kozubal, M., Szuster, A., & Wielgopolan, A. (2023). Emotional regulation strategies in daily life: The intensity of emotions and regulation choice. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1218694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraaij, V., & Garnefski, N. (2015). Cognitive, behavioral and goal adjustment coping and depressive symptoms in young people with diabetes: A search for intervention targets for coping skills training. Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings, 22, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lischetzke, T., & Eid, M. (2017). The functionality of emotional clarity: A process-oriented approach to understanding the relation between emotional clarity and well-being. In The happy mind: Cognitive contributions to well-being (pp. 371–388). Springer Nature. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, D. Y., & Thompson, R. J. (2017). Selection and implementation of emotion regulation strategies in major depressive disorder: An integrative review. Clinical Psychology Review, 57, 183–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q., Jiang, M., Li, S., & Yang, Y. (2021). Social support, resilience, and self-esteem protect against common mental health problems in early adolescence: A nonrecursive analysis from a two-year longitudinal study. Medicine, 100(4), e24334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovibond, P. F., & Lovibond, S. H. (1995). The structure of negative emotional states: Comparison of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) with the Beck Depression and Anxiety Inventories. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 33(3), 335–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Líbano, J., Torres-Vallejos, J., Oyanedel, J. C., González-Campusano, N., Calderón-Herrera, G., & Yeomans-Cabrera, M. M. (2023). Prevalence and variables associated with depression, anxiety, and stress among Chilean higher education students, post-pandemic. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 14, 1139946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Líbano, J., & Yeomans-Cabrera, M. M. (2024). Depression, anxiety, and stress in the Chilean Educational System: Children and adolescents post-pandemic prevalence and variables. Frontiers in Education (Lausanne), 9, 1407021. Available online: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2024.1407021/full (accessed on 31 March 2025).

- Martínez-Líbano, J., Yeomans-Cabrera, M. M., Koch Serey, A., Santander Ramírez, N., Cortés Silva, V., & Iturra Lara, R. (2025). Psychometric properties of the Trait Meta-Mood Scale (TMMS-24) in the Chilean child and adolescent population. Salud, Ciencia y Tecnologia, 5, 1376. Available online: https://sct.ageditor.ar/index.php/sct/article/view/1376 (accessed on 31 March 2025).

- McCurdy, B. H., Scozzafava, M. D., Bradley, T., Matlow, R., Weems, C. F., & Carrion, V. G. (2023). Impact of anxiety and depression on academic achievement among underserved school children: Evidence of suppressor effects. Current Psychology, 42(30), 26793–26801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIntosh, C. N., & Fischer, D. G. (2000). Beck’s cognitive triad: One versus three factors. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science/Revue Canadienne des Sciences du Comportement, 32(3), 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaughlin, K. A., & Lambert, H. K. (2017). Child trauma exposure and psychopathology: Mechanisms of risk and resilience. Current Opinion in Psychology, 14, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mesurado, B., Vidal, E. M., & Mestre, A. L. (2018). Negative emotions and behaviour: The role of regulatory emotional self-efficacy. Journal of Adolescence, 64, 62–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Education. (2015). Diversificación de la enseñanza Decreto n°83/2015 aprueba criterios y orientaciones de adecuación curricular para estudiantes con necesidades educativas especiales de educación parvularia y educación básica. Available online: https://especial.mineduc.cl/wp-content/uploads/sites/31/2016/08/Decreto-83-2015.pdf (accessed on 31 March 2025).

- Modecki, K. L., Zimmer-Gembeck, M. J., & Guerra, N. (2017). Emotion regulation, coping, and decision making: Three linked skills for preventing externalizing problems in adolescence. Child Development, 88(2), 417–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrish, L., Rickard, N., Chin, T. C., & Vella-Brodrick, D. A. (2018). Emotion regulation in adolescent well-being and positive education. Journal of Happiness Studies, 19, 1543–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyanedel, J. C., Vargas, S., Mella, C., & Páez, D. (2015). Validación del índice de bienestar personal (PWI) en usuarios vulnerables de servicios de salud en Santiago. Revista Médica de Chile, 143(9), 1144–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J., & Naragon-Gainey, K. (2020). Is more emotional clarity always better? An examination of curvilinear and moderated associations between emotional clarity and internalising symptoms. Cognition and Emotion, 34(2), 273–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peter, C., & Jule, A. (2023). A systematic review of pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions for the treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder. Archives of Clinical Psychiatry, 50(1), 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Ripoll-Núñez, K., Carrillo, S., Gómez, Y., & Villada, J. (2020). Predicting well-being and life satisfaction in Colombian adolescents: The role of emotion regulation, proactive coping, and prosocial behavior. Psykhe, 29(2). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubenstein, L. M., Hamilton, J. L., Stange, J. P., Flynn, M., Abramson, L. Y., & Alloy, L. B. (2015). The cyclical nature of depressed mood and future risk: Depression, rumination, and deficits in emotional clarity in adolescent girls. Journal of Adolescence, 42, 68–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salovey, P., Mayer, J. D., Goldman, S. L., Turvey, C., & Palfai, T. P. (1995). Emotional attention, clarity, and repair: Exploring emotional intelligence using the Trait Meta-Mood Scale. In J. W. Pennebaker (Ed.), Emotion, disclosure, & health (pp. 125–154). American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Sawyer, S., & Patton, G. (2018). Health and well-being in adolescence. In Handbook of adolescent development research and its impact on global policy (pp. 28–45). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger, C. D. (2021). Stress and anxiety in sports. In Anxiety in sports (pp. 3–17). Taylor & Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Tao, A., Ho, K. H. M., Yang, C., & Chan, H. Y. L. (2023). Effects of non-pharmacological interventions on psychological outcomes among older people with frailty: A systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 140, 104437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villagrán, C., Hernández, M. E. M., & Delgado, S. C. (2018). Relación entre variables mediadoras del desempeño docente y resultados educativos: Una aproximación al liderazgo escolar. Opción: Revista de Ciencias Humanas y Sociales, (87), 213–240. [Google Scholar]

- Von Elm, E., Altman, D. G., Egger, M., Pocock, S. J., Gøtzsche, P. C., & Vandenbroucke, J. P. (2007). The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. The Lancet, 370(9596), 1453–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willner, C. J., Hoffmann, J. D., Bailey, C. S., Harrison, A. P., Garcia, B., Ng, Z. J., Cipriano, C., & Brackett, M. A. (2022). The development of cognitive reappraisal from early childhood through adolescence: A systematic review and methodological recommendations. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 875964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Medical Association. (2013). World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA, 310(20), 2191–2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubin, J., & Spring, B. (1977). Vulnerability: A new view of schizophrenia. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 86(2), 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Categories | Categories | n (%) | Emotional Clarity | Emotional Regulation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M ± SD | M ± SD | t/F | M ± SD | t/F | ||

| Gender | Woman | 277 (43.6) | 22.0 ± 8.64 | −4.01 ** | 24.2 ± 8.33 | −3.08 ** |

| Man | 359 (56.4) | 24.7 ± 7.84 | 26.2 ± 7.58 | |||

| Age (years) | 10 | 50 (25.4) | 25.4 ± 7.00 | 1.67 | 25.8 ± 7.01 | 1.05 |

| 11 | 120 (24.9) | 24.9 ± 7.98 | 26.5 ± 8.18 | |||

| 12 | 104 (22.2) | 22.2 ± 8.18 | 25.1 ± 7.94 | |||

| 13 | 128 (24.1) | 24.1 ± 8.34 | 25.8 ± 7.90 | |||

| 14 | 100 (22.3) | 22.3 ± 8.21 | 24.7 ± 7.63 | |||

| 15 | 77 (23.2) | 23.2 ± 8.81 | 24.9 ± 8.06 | |||

| 16 | 42 (22.9) | 22.9 ± 8.93 | 23.7 ± 8.99 | |||

| 17 | 13 (21.0) | 21.0 ± 8.90 | 21.8 ± 7.47 | |||

| 18 | 2 (27.5) | 27.5 ± 17.6 | 27.5 ± 17.6 | |||

| Grade | Fifth | 133 (20.9) | 24.6 ± 7.57 | 0.9 | 25.2 ± 7.38 | 1.37 |

| Sixth | 105 (16.5) | 23.9 ± 7.79 | 26.8 ± 7.67 | |||

| Seventh | 129 (20.3) | 23.6 ± 8.80 | 26.0 ± 8.30 | |||

| Eight | 108 (17.0) | 22.6 ± 8.20 | 24.7 ± 7.99 | |||

| First Medio (Ninth) | 70 (11.0) | 22.3 ± 7.84 | 23.7 ± 7.21 | |||

| Second Medio (Tenth) | 65 (10.2) | 23.9 ± 9.96 | 25.3 ± 9.23 | |||

| Third Medio (Eleventh) | 22 (3.5) | 22.5 ± 8.98 | 24.1 ± 8.84 | |||

| Fourth Medio (Twelfth) | 4 (0.6) | 21.5 ± 2.88 | 22.0 ± 5.09 | |||

| Variables | Emotional Regulation | Depression | Personal Well-Being |

|---|---|---|---|

| Emotional Regulation | 1.000 | ||

| Depression | −0.251 ** | 1.000 | |

| Personal Well-being | 0.373 ** | −0.337 ** | 1.000 |

| Effect | B | SE | t | p | IC 95% (LCL–UCL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total effect (Path c) | 1.099 | 0.107 | 10.29 | <0.001 | 0.890–1.309 |

| Direct effect (Path c′) | 0.950 | 0.106 | 8.94 | <0.001 | 0.742–1.159 |

| Indirect effect (Path a × b) | 0.149 | 0.036 | — | — | 0.082–0.225 |

| Effect | B | SE | t | p | IC 95% (LCL–UCL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interaction | −0.0087 | 0.0031 | −28.300 | 0.0048 | −0.0148–−0.0027 |

| Conditional (Emotional clarity = 15) | −0.0595 | 0.0428 | −13.891 | 0.1653 | −0.1437–0.0246 |

| Conditional (Emotional clarity = 23) | −0.1293 | 0.0375 | −34.461 | 0.0006 | −0.2030–−0.0556 |

| Conditional (Emotional clarity = 33) | −0.2166 | 0.0508 | −42.601 | <0.001 | −0.3164–−0.1167 |

| Moderate mediation index | 0.0080 | 0.0034 | — | — | 0.0017–0.0149 |

| Emotional Clarity | B | SE | t | p | LLCI | ULCI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean − SD | −0.0595 | 0.0428 | −13.891 | 0.1653 | −0.1437 | 0.0246 |

| Mean | −0.1293 | 0.0375 | −34.461 | 0.0006 | −0.2030 | −0.0556 |

| Mean + SD | −0.2166 | 0.0508 | −42.601 | 0.0000 | −0.3164 | −0.1167 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the University Association of Education and Psychology. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Martínez-Líbano, J.; Yeomans-Cabrera, M.-M.; Koch, A.; Iturra Lara, R.; Torrijos Fincias, P. Clarity and Emotional Regulation as Protective Factors for Adolescent Well-Being: A Moderated Mediation Model Involving Depression. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2025, 15, 130. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15070130

Martínez-Líbano J, Yeomans-Cabrera M-M, Koch A, Iturra Lara R, Torrijos Fincias P. Clarity and Emotional Regulation as Protective Factors for Adolescent Well-Being: A Moderated Mediation Model Involving Depression. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education. 2025; 15(7):130. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15070130

Chicago/Turabian StyleMartínez-Líbano, Jonathan, María-Mercedes Yeomans-Cabrera, Axel Koch, Roberto Iturra Lara, and Patrícia Torrijos Fincias. 2025. "Clarity and Emotional Regulation as Protective Factors for Adolescent Well-Being: A Moderated Mediation Model Involving Depression" European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education 15, no. 7: 130. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15070130

APA StyleMartínez-Líbano, J., Yeomans-Cabrera, M.-M., Koch, A., Iturra Lara, R., & Torrijos Fincias, P. (2025). Clarity and Emotional Regulation as Protective Factors for Adolescent Well-Being: A Moderated Mediation Model Involving Depression. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 15(7), 130. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15070130