Promoting Attitudes Towards Disability in University Settings: A Quasi-Experimental Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Ethical Considerations

2.2. Participants

2.3. Sample Procedure

2.4. Measures and Instruments

- Sociodemographic Variables (gender, age, higher level of prior education, and degree program), variables related to contact with people with disabilities (prior contact with people with disability, reason for contact, frequency of interaction, type of disability, and emotional response in presence of people with disabilities), and variables related to knowledge about disabilities (physical disability, sensory disability and intellectual disability)

- Assessment of Attitudes Towards Disability: Score on the Attitudes Towards Disability Scale (Arias González et al., 2016).

2.5. Statistical Analysis

2.6. Description of the Intervention

3. Results

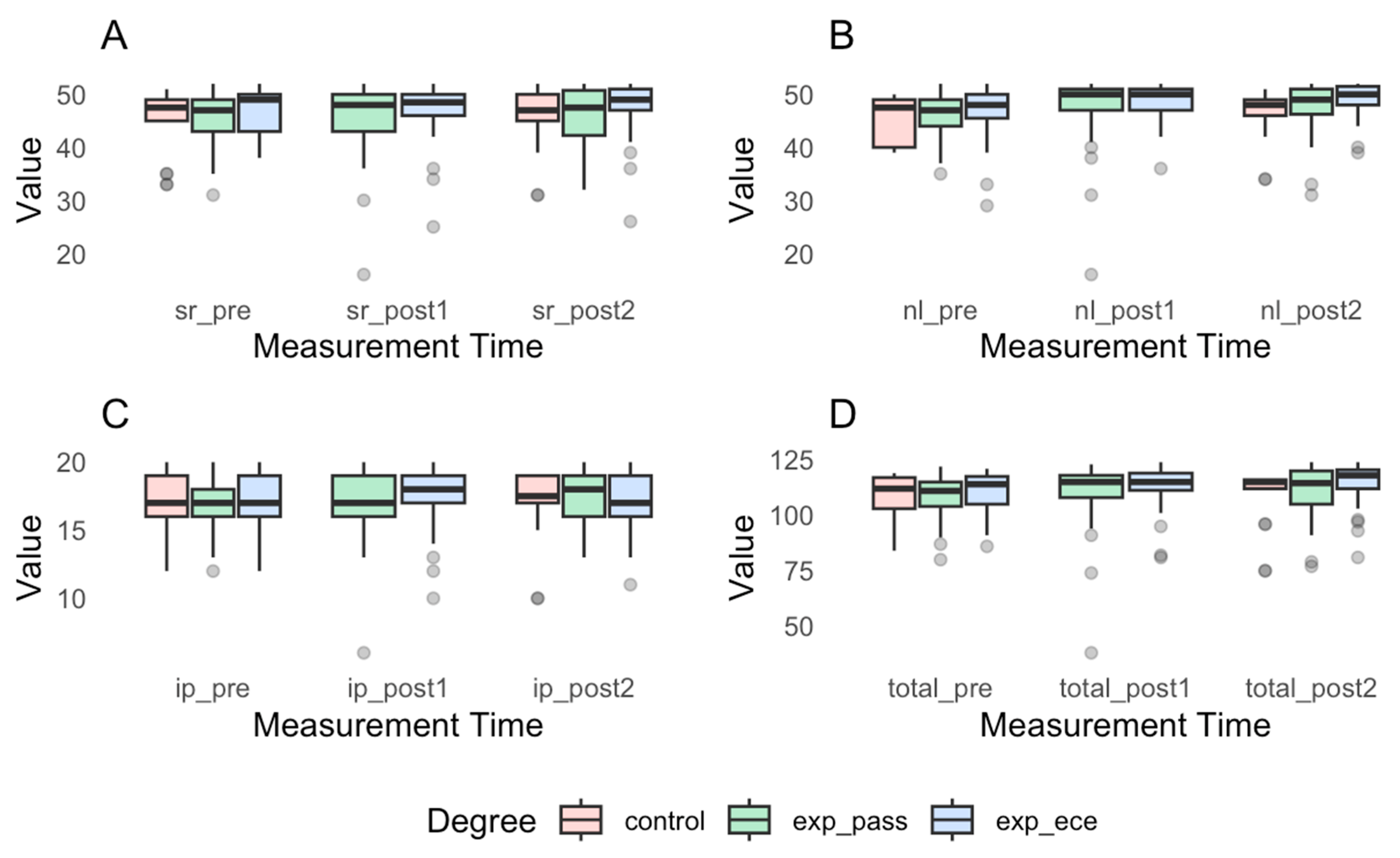

3.1. Group Comparison

3.1.1. Factor 1: Social and Interpersonal Relationships with People with Disabilities

3.1.2. Factor 2: Normalized Life

3.1.3. Factor 3: Intervention Programs

3.1.4. Total Score

3.2. Intra-Group Comparison over Time

3.2.1. Factor 1: Social and Interpersonal Relationships with People with Disabilities

3.2.2. Factor 2: Normalized Life

3.2.3. Factor 3: Intervention Programs

3.2.4. Total Score

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PASS | Physical Activity and Sport Sciences |

| ECE | Early Childhood Education |

| SR | Social and Interpersonal relationships with people with disabilities |

| NL | Normalized Life |

| IP | Intervention Programs |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

| Title | Contents | Resources |

|---|---|---|

| Disability Contextualization |

| YouTube videos and own elaboration slides |

| Attitudes towards disability |

| YouTube videos and own elaboration slides |

| Inclusive Language Terms |

| YouTube videos, google Jamboard and own elaboration slides |

| Accessibility and supports |

| YouTube videos and own elaboration slides |

| Title | PASS | ECE |

|---|---|---|

| Practical Situation—Visual Disability |

|

|

| Faculty Accessibility Practice |

| |

| Cooperation and Observation Circuit |

|

|

| Guiding a Blind Person |

| |

Appendix A.2

| Degree | Comp. | Ac.Yr | Credits/Subjects | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical Activity and Sports Sciences | CT8 | 1st Year | 18 Credits/ 3 Subjects | CT8: Promote equal opportunities and universal accessibility for people with disabilities and special populations in the field of physical activity and sports. |

| 2nd Year | 42 Credits/ 7 Subjects | |||

| 3rd Year | 18 Credits/ 3 Subjects | |||

| 4th Year | 12 Credits/ 2 Subjects | |||

| Optatives | 54 Credits/ 9 Subjects | |||

| Early Childhood Education | CG3 CT3.6 CT8 CT12 CE70 CE81 CE83 | 1st Year | 36 Credits/ 6 Subjects | CG3: Design and regulate learning environments within diverse contexts that address the unique educational needs of students, promote gender equality, equity, and respect for human rights. CT3.6: Critically and logically reflect on the need to eliminate all forms of discrimination, whether direct or indirect, particularly those based on race, gender, sexual orientation, or disability. CT8: Develop and demonstrate an ethical commitment in professional practice, a commitment that should foster the concept of holistic education with critical and responsible attitudes, ensuring effective equality between women and men, equal opportunities, universal accessibility for individuals with disabilities, and upholding the values of a culture of peace and democratic principles. CT12: Recognize the right to equal opportunities for individuals with disabilities and implement measures aimed at preventing or compensating for the disadvantages that may hinder their full participation in political, economic, cultural, and social life. CE.70: Understand the needs of children, accompanied by indicators of risk situations, to promote actions aimed at reducing the impact of disability on the child’s overall development. CE.81: Offer individualized educational measures through ICT to address diversity. CE83: Select conceptual and methodological tools to identify and address educational and organizational challenges in Early Childhood Education, developing flexible curricular projects capable of accommodating diversity. |

| 2nd Year | 6 Credits/ 1 Subjects | |||

| 3rd Year | 24 Credits/ 4 Subjects | |||

| 4th Year | N/A | |||

| Optatives | 36 Credits/ 6 Subjects |

References

- Arias González, V., Arias Martínez, B., Verdugo Alonso, M. Á., Rubia Avi, M., & Jenaro Río, C. (2016). Evaluación de actitudes de los profesionales hacia las personas con discapacidad. Siglo Cero. Revista Española Sobre Discapacidad Intelectual, 47(2), 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atoche-Silva, L. A., Horna-Calderón, V. E., Vela-Miranda, O. M., & Sánchez-Chero, M. J. (2021). Attitudes towards people with disabilities in university students. Revista de La Universidad del Zulia, 12(35), 209–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babik, I., & Gardner, E. S. (2021). Factors affecting the perception of disability: A developmental perspective. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 702166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bebetsos, E., Derri, V., & Vezos, N. (2017). Can an intervention program affect students’ attitudes toward inclusive physical education? An application of the “Theory of planned behavior. Turk Psikoloji Dergisi, 32(78), 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonett, D. G., & Wright, T. A. (2015). Cronbach’s alpha reliability: Interval estimation, hypothesis testing, and sample size planning. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 36(1), 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booth, T., & Ainscow, M. (2018). Guía para la educación inclusiva desarrollando el aprendizaje y la participación. In Educational management administration and leadership (Vol. 1, Issue 6). Federación Down Galicia. Available online: https://downgalicia.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/Guia-para-la-Educacion-Inclusiva.pdf (accessed on 5 April 2025).

- Cliff, N. (1993). Dominance statistics: Ordinal Analyses to answer ordinal questions. Psychological Bulletin, 114(3), 494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delve, H. L., & Limpaecher, A. (2024). Understanding qualitative research in education. Allyn & Bacon. [Google Scholar]

- Erkilic, M., & Durak, S. (2013). Tolerable and inclusive learning spaces: An evaluation of policies and specifications for physical environments that promote inclusion in Turkish primary schools. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 17(5), 462–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estany, B. A. M., & Bravo, S. A. (2017). Inclusión del alumnado con discapacidad en los estudios superiores. Ideas y actitudes del colectivo estudiantil. Revista Española de Discapacidad, 5(2), 129–148. Available online: https://www.cedd.net/redis/index.php/redis/article/view/341 (accessed on 5 April 2025). [CrossRef]

- Felipe Rello, C., Garoz Puerta, I., & Tejero González, C. M. (2018). Análisis comparativo del efecto de tres programas de sensibilización hacia la discapacidad en Educación Física (Comparative analysis of the effect of three physical education programs on awareness toward disability). Retos, 2041(34), 258–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, J., & Weisberg, S. (2019). An R companion to applied regression. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, C., & VanPuymbrouck, L. (2021). Impact of occupational therapy education on students’ disability attitudes: A longitudinal study. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 75(4). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gámez-Calvo, L., Beltrán, V. H., Gamonales, J. M., Muñoz-Jiménez, J., & Gózalo, M. (2024a). Attitudes towards disabilities and inclusive method-ologies in physical education lessons: Systematic review. Movimento, 30, 139771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gámez-Calvo, L., Gamonales, J. M., Hernández-Beltrán, V., & Muñoz-Jiménez, J. (2024b). Análisis bibliométrico de los estudios sobre actitudes hacia la discapacidad e inclusión en profesores de educación física (Bibliometric analysis of studies on attitudes towards disability and inclusion in physical education teachers). Retos, 54, 188–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gámez-Calvo, L., Muñoz-Jiménez, J., & Gozalo, M. (2025). The importance of positive attitudes toward disability among future health and education professionals: A comparative study. Education Sciences, 15(1), 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garabal-Barbeira, J., Pousada García, T., Espinosa Breen, P. C., & Saleta Canosa, J. L. (2018). Las actitudes como factor clave en la inclusión universitaria. Revista Española de Discapacidad, 6(1), 181–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Fernández, J. M., Inglés, C. J., Vicent Juan, M., Gonzálvez Macià, C., & Mañas Viejo, C. (2017). Actitudes hacia la Discapacidad en el Ámbito Educativo a través del SSCI (2000–2011). Análisis temático y bibliométrico. Electronic Journal of Research in Education Psychology, 11(29), 139–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Gray, B. H., Cooke, R. A., & Tannenbaum, A. S. (1978). Research involving human subjects. Science, 201(4361), 1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernández-Beltrán, V., González-Coto, V. A., Gámez-Calvo, L., Suárez-Arévalo, E., & Gamonales, J. M. (2023). The importance of attitudes towards people with disabilities in early childhood and primary education. Systematic review. Bordon. Revista de Pedagogia, 75(1), 83–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jardinez, M. J., & Natividad, L. R. (2024). The advantages and challenges of inclusive education: Striving for equity in the classroom. Shanlax International Journal of Education, 12(2), 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jean Dunn, O. (1964). Multple Comparisons Using Rank Sums. Technometrics, 6(3), 241–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krämer, S., Möller, J., & Zimmermann, F. (2021). Inclusive education of students with general learning difficulties: A meta-analysis. Review of Educational Research, 91(3), 432–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruskal, W. H., & Wallis, W. A. (1952). Use of ranks in one-criterion variance analysis. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 47(260), 583–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, J., & Moreno, R. (2019). Las actitudes de los estudiantes universitarios de grado hacia la discapacidad. The attitudes of undergraduate students towards disability. Revista de Educación Inclusiva, 12, 50–65. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez Martín, M., & Bilbao León, M. (2011). Los docentes de la universidad de Burgos y su actitud hacia las personas con discapacidad. Siglo Cero, Revista Española sobre Discapacidad Intelectual, 42(240), 50–78. [Google Scholar]

- Mezzanotte, C., & Calvel, C. (2023). Indicators of inclusion in education: A framework for analysis. OECD Education Working Papers. OECD. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno Pilo, I., Morán Suárez, L., Gómez Sánchez, L., Solís García, P., & Alcedo Rodríguez, A. (2022). Actitudes hacia las personas con discapacidad una revisión de la literatura. Revista Española de Discapacidad, 10(1), 7–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega, M. G., Cilleros, V. M., & Jenaro, C. (2014). El Index para la inclusion: Presencia, aprendizaje y participación. Revista de Educación Inclusiva, 7(3), 186–201. [Google Scholar]

- Pinheiro, J., & Bates, D. (2000). Mixed-effects models in S and S-plus. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Polo, M. T., Fernández, C., & Díaz, C. (2011). Estudio de las actitudes de estudiantes de ciencias sociales y psicología: Relevancia de la información y contacto con personas discapacitadas. Universitas Psychologica, 10(1), 113–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polo Sánchez, M. T., Fernández-Jiménez, C., & Fernández Cabezas, M. (2018). The attitudes of different partners involved in higher education towards students with disabilities. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 65(4), 442–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, K. C., & Naik, S. (2024). Inclusive education: A foundation for equality and empowerment at the elementary stage. International Journal of Multidisciplinary Research in Arts, Science and Technology, 2(2), 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. (2023). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. [Google Scholar]

- Reina, R., Haegele, J. A., Pérez-Torralba, A., Carbonell-Hernández, L., & Roldan, A. (2021). The influence of a teacher-designed and-implemented disability awareness programme on the attitudes of students toward inclusion. European Physical Education Review, 27(4), 837–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reina, R., Hutzler, Y., Carmen Iniguez-Santiago, M., Antonio Moreno-Murcia, J., & Reina Vaillo, R. (2016). Attitudses towards inclusion of students with disabilities in physical education questionnaire (AISDPE): A two-component scale in spanish. European Journal of Human Movement, 36, 75–87. [Google Scholar]

- Reina, R., Íñiguez-Santiago, M. C., Ferriz-Morell, R., Martínez-Galindo, C., Cebrián-Sánchez, M., & Roldan, A. (2022). The effects of modifying contact, duration, and teaching strategies in awareness interventions on attitudes towards inclusion in physical education. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 37(1), 57–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandoval, M. (2002). Index for inclusion. Una guía para la evaluación y mejora de la educación inclusiva. Contextos Educativos: Revista de Educación, 5, 227–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scior, K., & Werner, S. (2015). Changing attitudes to learning disability (pp. 1–25). Royal Mencap Society. Available online: https://www.mencap.org.uk/sites/default/files/2016-08/Attitudes_Changing_Report.pdf (accessed on 5 April 2025).

- Shapiro, S. S., & Wilk, A. M. B. (1965). An analysis of variance test for normality (complete samples). Biometrica, 52(3–4), 591–611. Available online: https://sci2s.ugr.es/keel/pdf/algorithm/articulo/shapiro1965.pdf (accessed on 5 April 2025). [CrossRef]

- Shields, N., Bhowon, Y., Prendergast, L., Cleary, S., & Taylor, N. F. (2024). Fostering positive attitudes towards interacting with young people with disability among health students: A stepped-wedge trial. Disability and Rehabilitation, 46(6), 1212–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simón Medina, N., Gómezescobar, A., & Abellán López, M. Á. (2024). Psychometric analysis of the scale of attitude towards persons with disabilities in a sample of MUFPS students. Siglo Cero, 55(2), 43–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taber, K. S. (2018). The use of cronbach’s alpha when developing and reporting research instruments in science education. Research in Science Education, 48(6), 1273–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tai, J., Ajjawi, R., Bearman, M., Boud, D., Dawson, P., & Jorre de St Jorre, T. (2023). Assessment for inclusion: Rethinking contemporary strategies in assessment design. Higher Education Research and Development, 42(2), 483–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tejero, J. P., Roig, M. G., Álvarez, E. F., & López, J. C. (2022). Efectos de un programa de concienciación hacia la discapacidad en Educación Física. Retos: Nuevas Tendencias en Educación Física, Deporte y Recreación, 45, 1041–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VanPuymbrouck, L., & Friedman, C. (2020). Relationships between occupational therapy students’ understandings of disability and disability attitudes. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 27(2), 122–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, K., & Clerke, T. (2024). Qualitative methods in special education research—A scoping review. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Categories | n | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention program | Control | 20 | 14.6% |

| Physical Activity and Sport Sciences | 66 | 48.2% | |

| Early Childhood Education | 51 | 37.2% | |

| Gender | Female | 85 | 62.0% |

| Male | 52 | 38.0% | |

| Contact with Disability | Yes | 44 | 32.0% |

| No | 93 | 67.9% | |

| Contact Reason * | Familiar | 8 | 18.2% |

| Laboral | 16 | 36.4% | |

| Care Intervention | 2 | 4.5% | |

| Leisure and Friendship | 0 | 0.0% | |

| Other | 18 | 40.9% | |

| Various | 3 | 6.8% | |

| Contact Frequency * | Every Day | 3 | 6.8% |

| Several Times a Week | 14 | 31.8% | |

| Several Times a Month | 21 | 47.7% | |

| Less than once a Mont | 10 | 22.7% | |

| Type of Disability * | Physical Disability | 17 | 38.6% |

| Mental Illness | 12 | 27.3% | |

| Sensory Disability | 10 | 22.3% | |

| Other types | 5 | 11.4% | |

| Feeling in presence of people with disability | Very Comfortable | 33 | 24.1% |

| Quite Comfortable | 62 | 45.3% | |

| Indifferent | 39 | 28.5% | |

| Quite Uncomfortable | 2 | 1.5% | |

| Very Uncomfortable | 1 | 0.7% |

| Data Collected | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor | Original Questionnaire | Pre | Post 1 | Post 2 |

| SR | 0.858 | 0.816 | 0.868 | 0.872 |

| NL | 0.822 | 0.798 | 0.908 | 0.840 |

| IP | 0.603 | 0.497 | 0.652 | 0.589 |

| Total Score | 0.928 | 0.889 | 0.936 | 0.921 |

| Factor 1: “Social and Interpersonal Relationships with People with Disabilities” | |||||||||

| Pre-test | Post-test 1 | Post-test 2 | |||||||

| Degree | Mean | Sd | Attitudes | Mean | Sd | Attitudes | Mean | Sd | Attitudes |

| Control | 45.400 | 6.09 | Medium | N/A | N/A | N/A | 45.60 | 6.14 | Medium |

| PASS | 45.818 | 4.70 | Medium | 45.79 | 6.41 | Medium | 45.95 | 5.36 | Medium |

| ECE | 46.70 | 4.32 | Medium | 46.97 | 5.14 | Medium | 48.23 | 4.76 | Medium |

| Factor 2: “Normalized Life” | |||||||||

| Pre-test | Post-test 1 | Post-test 2 | |||||||

| Degree | Mean | Sd | Attitudes | Mean | Sd | Attitudes | Mean | Sd | Attitudes |

| Control | 45.60 | 4.45 | Medium | N/A | N/A | N/A | 46.40 | 4.86 | Medium |

| PASS | 46.13 | 3.72 | Medium | 47.81 | 6.10 | Medium | 48.00 | 4.38 | Favorable |

| ECE | 46.92 | 4.74 | Medium | 48.93 | 3.22 | Favorable | 49.31 | 3.06 | Favorable |

| Factor 3: “Intervention Programs” | |||||||||

| Pre-test | Post-test 1 | Post-test 2 | |||||||

| Degree | Mean | Sd | Attitudes | Mean | Sd | Attitudes | Mean | Sd | Attitudes |

| Control | 17.00 | 2.38 | Medium | N/A | N/A | N/A | 16.90 | 2.65 | Medium |

| PASS | 17.07 | 1.80 | Medium | 17.03 | 2.50 | Medium | 17.26 | 2.15 | Medium |

| ECE | 17.00 | 1.91 | Medium | 17.37 | 2.08 | Medium | 17.31 | 2.03 | Medium |

| Total Punctuation | |||||||||

| Pre-test | Post-test 1 | Post-test 2 | |||||||

| Degree | Mean | Sd | Attitudes | Mean | Sd | Attitudes | Mean | Sd | Attitudes |

| Control | 108.00 | 11.58 | Medium | N/A | N/A | N/A | 108.90 | 12.99 | Medium |

| PASS | 109.03 | 8.75 | Medium | 110.64 | 14.03 | Medium | 111.21 | 10.68 | Medium |

| ECE | 110.62 | 9.59 | Medium | 113.28 | 8.92 | Medium | 114.86 | 8.38 | Medium |

| Factor 1: “Social and Interpersonal Relationships with People with Disabilities” | |||||||

| Measurement moment | Group Comparison | Sd | p-value | P_adj | Sig | Cliff’s Delta | Mg |

| PRE | Control vs. PASS | −0.1538 | 0.8777 | 1.000 | Ns | −0.015 | Negligible |

| Control vs. ECE | 0.7338 | 0.4630 | 1.000 | Ns | −0.198 | Small | |

| PASS vs. ECE | 1.249 | 0.2116 | 0.634 | Ns | −0.176 | Small | |

| POST1 | PASS vs. ECE | 0.8843 | 0.3765 | 0.376 | Ns | −0.176 | Small |

| POST2 | Control vs. PASS | 0.2358 | 0.8135 | 1.000 | Ns | −0.015 | Negligible |

| Control vs. ECE | 2.0634 | 0.0390 | 0.117 | Ns | −0.198 | Small | |

| PASS vs. ECE | 2.5972 | 0.0093 | 0.028 | * | −0.176 | Small | |

| Factor 2: “Normalized Life” | |||||||

| Measurement moment | Group Comparison | Sd | p-value | P_adj | Sig | Cliff’s Delta | Mg |

| PRE | Control vs. PASS | 0.1313 | 0.8954 | 1.000 | Ns | −0.200 | Small |

| Control vs. ECE | 1.4210 | 0.1553 | 0.465 | Ns | −0.364 | Medium | |

| PASS vs. ECE | 1.8310 | 0.0670 | 0.201 | Ns | −0.146 | Negligible | |

| POST1 | PASS vs. ECE | 0.3334 | 0.7387 | 0.738 | Ns | −0.147 | Negligible |

| POST2 | Control vs. PASS | 1.9380 | 0.0526 | 0.157 | Ns | −0.200 | Small |

| Control vs. ECE | 3.0008 | 0.0026 | 0.008 | ** | −0.364 | Medium | |

| PASS vs. ECE | 1.5932 | 0.1111 | 0.333 | Ns | −0.147 | Negligible | |

| Factor 3: “Intervention Programs” | |||||||

| Measurement moment | Group Comparison | Sd | p-value | P_adj | Sig | Cliff’s Delta | Mg |

| PRE | Control vs. PASS | −0.0238 | 0.9810 | 1.000 | Ns | −0.006 | Negligible |

| Control vs. ECE | −0.1523 | 0.8789 | 1.000 | Ns | −0.026 | Negligible | |

| PASS vs. ECE | −0.1829 | 0.8548 | 1.000 | Ns | −0.022 | Negligible | |

| POST1 | PASS vs. ECE | 0.64506 | 0.5188 | 0.5188 | Ns | −0.022 | Negligible |

| POST2 | Control vs. PASS | 0.24622 | 0.8055 | 1.000 | Ns | −0.006 | Negligible |

| Control vs. ECE | 0.27649 | 0.7821 | 1.000 | Ns | −0.026 | Negligible | |

| PASS vs. ECE | 0.05417 | 0.9567 | 1.000 | Ns | −0.022 | Negligible | |

| Total Punctuation | |||||||

| Measurement moment | Group Comparison | Sd | p-value | P_adj | Sig | Cliff’s Delta | Mg |

| PRE | Control vs. PASS | −0.1410 | 0.887 | 1.000 | Ns | −0.097 | Negligible |

| Control vs. ECE | 0.9602 | 0.336 | 1.000 | Ns | −0.277 | Small | |

| PASS vs. ECE | 1.5519 | 0.120 | 0.362 | Ns | −0.154 | Small | |

| POST1 | PASS vs. ECE | 0.6009 | 0.547 | 0.547 | Ns | −0.154 | Small |

| POST2 | Control vs. PASS | 1.3040 | 0.192 | 0.576 | Ns | −0.097 | Negligible |

| Control vs. ECE | 2.6095 | 0.009 | 0.027 | * | −0.277 | Small | |

| PASS vs. ECE | 1.9074 | 0.056 | 0.169 | Ns | −0.153 | Small | |

| Factor 1: “Social and Interpersonal Relationships with People with Disabilities” | |||||||

| Time Moment | Sd | p-value | P_adj | Sig | Cliff’s Delta | Mg | |

| Control | Pre-test vs. Post-test 2 | −0.0543 | 0.9566 | 0.956 | Ns | 0.133 | Negligible |

| PASS | Pre-test vs. Post-test 1 | 0.6740 | 0.5002 | 1.000 | Ns | 0.077 | Negligible |

| Pre-test vs. Post-test 2 | 0.6260 | 0.5312 | 1.000 | Ns | 0.133 | Negligible | |

| Post-test1 vs. Post-test 2 | −0.0832 | 0.9336 | 1.000 | Ns | −0.058 | Negligible | |

| ECE | Pre-test vs. Post-test 1 | 0.4836 | 0.6286 | 1.000 | Ns | 0.077 | Negligible |

| Pre-test vs. Post-test 2 | 2.3326 | 0.0196 | 0.058 | Ns | 0.133 | Negligible | |

| Post-test1 vs. Post-test 2 | 1.7880 | 0.0737 | 0.221 | Ns | −0.058 | Negligible | |

| Factor 2: “Normalized Life” | |||||||

| Time Moment | Sd | p-value | P_adj | Sig | Cliff’s Delta | Mg | |

| Control | Pre-test vs. Post-test 2 | 0.5475 | 0.584 | 0.584 | Ns | 0.325 | Small |

| PASS | Pre-test vs. Post-test 1 | 3.7518 | 0.00017 | 0.0005 | *** | 0.368 | Medium |

| Pre-test vs. Post-test 2 | 3.5157 | 0.00043 | 0.001 | ** | 0.325 | Small | |

| Post-test1 vs. Post-test 2 | −0.4336 | 0.664 | 1.000 | Ns | 0.045 | Negligible | |

| ECE | Pre-test vs. Post-test 1 | 2.3729 | 0.0176 | 0.052 | Ns | 0.368 | Medium |

| Pre-test vs. Post-test 2 | 3.2124 | 0.0013 | 0.004 | ** | 0.325 | Small | |

| Post-test1 vs. Post-test 2 | 0.7555 | 0.449 | 1.000 | Ns | 0.045 | Negligible | |

| Factor 3: “Intervention Programs” | |||||||

| Time Moment | Sd | p-value | P_adj | Sig | Cliff’s Delta | Mg | |

| Control | Pre-test vs. Post-test 2 | 0.2197 | 0.826 | 0.826 | Ns | 0.088 | Negligible |

| PASS | Pre-test vs. Post-test 1 | 0.4399 | 0.659 | 1.000 | Ns | 0.093 | Negligible |

| Pre-test vs. Post-test 2 | 0.8346 | 0.403 | 1.000 | Ns | 0.088 | Negligible | |

| Post-test1 vs. Post-test 2 | 0.3477 | 0.727 | 1.000 | Ns | −0.006 | Negligible | |

| ECE | Pre-test vs. Post-test 1 | 1.2495 | 0.211 | 0.634 | Ns | 0.093 | Negligible |

| Pre-test vs. Post-test 2 | 1.0125 | 0.311 | 0.934 | Ns | 0.088 | Negligible | |

| Post-test1 vs. Post-test 2 | −0.2634 | 0.792 | 1.000 | Ns | −0.006 | Negligible | |

| Total Score | |||||||

| Time Moment | Sd | p-value | P_adj | Sig | Cliff’s Delta | Mg | |

| Control | Pre-test vs. Post-test 2 | 0.3816 | 0.7027 | 0.703 | Ns | 0.241 | Small |

| PASS | Pre-test vs. Post-test 1 | 2.1456 | 0.0319 | 0.096 | Ns | 0.225 | Small |

| Pre-test vs. Post-test 2 | 2.2293 | 0.0257 | 0.077 | Ns | 0.241 | Small | |

| Post-test1 vs. Post-test 2 | −0.0415 | 0.9668 | 1.000 | Ns | −0.029 | Negligible | |

| ECE | Pre-test vs. Post-test 1 | 1.3524 | 0.1762 | 0.528 | Ns | 0.225 | Small |

| Pre-test vs. Post-test 2 | 2.7998 | 0.0051 | 0.015 | * | 0.242 | Small | |

| Post-test1 vs. Post-test 2 | 1.3742 | 0.1693 | 0.508 | Ns | −0.029 | Negligible | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the University Association of Education and Psychology. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gámez-Calvo, L.; Gozalo, M.; Hernández-Mocholí, M.A.; Muñoz-Jiménez, J. Promoting Attitudes Towards Disability in University Settings: A Quasi-Experimental Study. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2025, 15, 119. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15070119

Gámez-Calvo L, Gozalo M, Hernández-Mocholí MA, Muñoz-Jiménez J. Promoting Attitudes Towards Disability in University Settings: A Quasi-Experimental Study. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education. 2025; 15(7):119. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15070119

Chicago/Turabian StyleGámez-Calvo, Luisa, Margarita Gozalo, Miguel A. Hernández-Mocholí, and Jesús Muñoz-Jiménez. 2025. "Promoting Attitudes Towards Disability in University Settings: A Quasi-Experimental Study" European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education 15, no. 7: 119. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15070119

APA StyleGámez-Calvo, L., Gozalo, M., Hernández-Mocholí, M. A., & Muñoz-Jiménez, J. (2025). Promoting Attitudes Towards Disability in University Settings: A Quasi-Experimental Study. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 15(7), 119. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15070119