Promoting Self-Regulation in Children with Cerebral Palsy: A Mixed Analysis of the Impact of a Training Program for Psychologists

Abstract

1. Introduction

The Current Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Quantitative Phase Materials and Methods

2.1.1. Sample

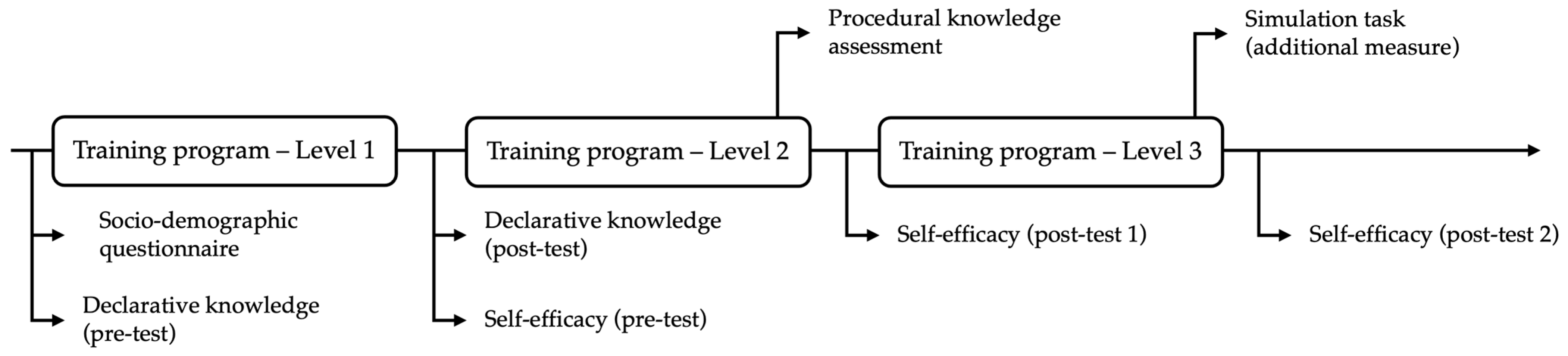

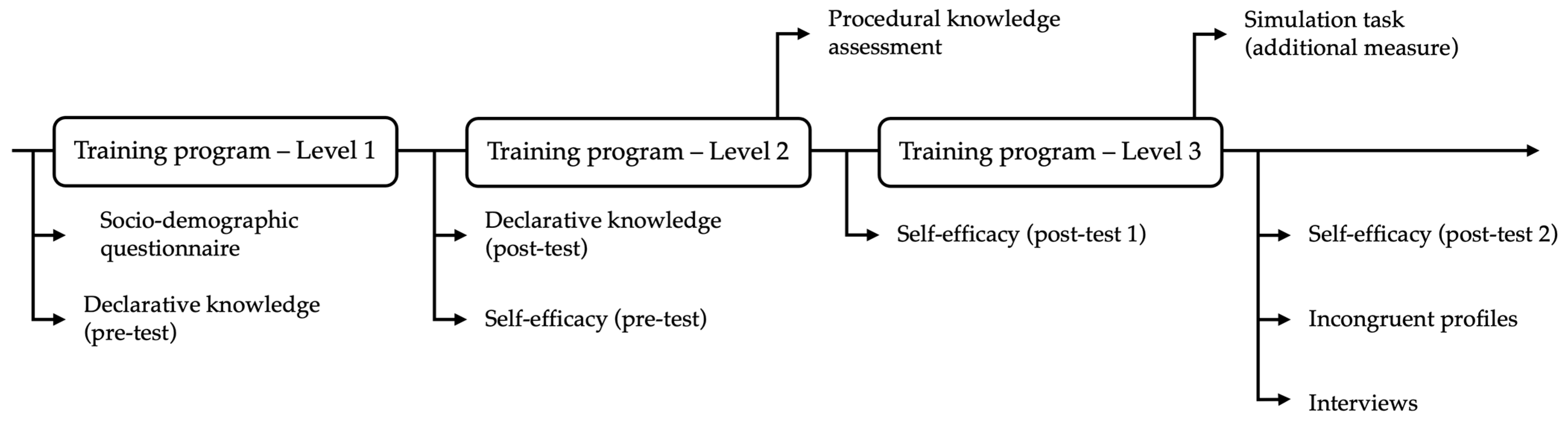

2.1.2. Assessment Protocol and Procedure

2.1.3. Variables and Instruments

Socio-Demographic

Declarative Knowledge

Procedural Knowledge

Self-Efficacy

2.1.4. Data Analysis

2.2. Qualitative Phase Materials and Methods

2.2.1. Sample

2.2.2. Procedure

2.2.3. Interviews

2.2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results and Findings

3.1. Quantitative Phase Results

3.1.1. Declarative Knowledge

3.1.2. Procedural Knowledge

3.1.3. Self-Efficacy

3.2. Qualitative Phase Findings

3.2.1. Participants’ Academic Background and Professional Experience

3.2.2. Features of the Training Model

3.2.3. Dispositional Profiles

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations and Implications for Research

4.2. Implications for Practice

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CP | Cerebral Palsy |

| SR | Self-Regulation |

References

- Abogsesa, A. S., & Kaushik, G. (2017). Impact of training and development on employee performance: A study of libyan bank. International Journal of Civic Engagement and Social Change, 4(3), 53–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aisen, M. L., Kerkovich, D., Mast, J., Mulroy, S., Wren, T. A., Kay, R. M., & Rethlefsen, S. A. (2011). Cerebral palsy: Clinical care and neurological rehabilitation. The Lancet Neurology, 10(9), 844–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, M., & Moura, O. (2013). Estrutura factorial da General Self-Efficacy Scale (Escala de Auto-Eficácia Geral) numa amostra de professores portugueses [Factorial structure of the General Self-Efficacy Scale in a sample of Portuguese teachers]. Laboratório de Psicologia, 9(1), 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boswell, S. S. (2013). Undergraduates’ perceived knowledge, self-efficacy, and interest in social science research. The Journal of Effective Teaching, 13(2), 48–57. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2021). Thematic analysis: A practical guide. SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, P. C., Roediger, H. L., & McDaniel, M. A. (2014). Make it stick: The science of successful learning. The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Burke, L. A., & Hutchins, H. M. (2007). Training transfer: An integrative literature review. Human Resource Development Review, 6(3), 263–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constantine, J., Fernald, J., Robinson, J., & Courtney, M. B. (2019). Best practices guidebook. Supporting students’ self-efficacity. Bluegrass Center for Teacher Quality. [Google Scholar]

- Dincer, A., Yeşilyurt, S., Noels, K. A., & Vargas Lascano, D. I. (2019). Self-determination and classroom engagement of EFL learners: A mixed-methods study of the Self-System Model of Motivational Development. SAGE Open, 9(2), 215824401985391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ertmer, P. A., & Newby, T. J. (2013). Behaviorism, cognitivism, constructivism: Comparing critical features from an instructional design perspective. Performance Improvement Quarterly, 26(2), 43–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, A. (2012). Discovering statistics using SPSS: And sex and drugs and rock’n’roll (3rd ed.). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Graham, H. K., Rosenbaum, P., Paneth, N., Dan, B., Lin, J.-P., Damiano, D. L., Becher, J. G., Gaebler-Spira, D., Colver, A., Reddihough, D. S., Crompton, K. E., & Lieber, R. L. (2016). Cerebral palsy. Nature Reviews Disease Primers, 2(1), 15082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatfield, T. G., Withers, T. M., & Greaves, C. J. (2020). Systematic review of the effect of training interventions on the skills of health professionals in promoting health behaviour, with meta-analysis of subsequent effects on patient health behaviours. BMC Health Services Research, 20(1), 593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honicke, T., & Broadbent, J. (2016). The influence of academic self-efficacy on academic performance: A systematic review. Educational Research Review, 17, 63–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBM Corp. (2022). IBM® SPSS® statistics™ (Version 29.0) [Computer software].

- Jeffries, L., Fiss, A., McCoy, S. W., & Bartlett, D. J. (2016). Description of primary and secondary impairments in young children with cerebral palsy. Pediatric Physical Therapy, 28(1), 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klassen, R. M., & Durksen, T. L. (2014). Weekly self-efficacy and work stress during the teaching practicum: A mixed methods study. Learning and Instruction, 33, 158–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kornell, N., & Bjork, R. A. (2007). The promise and perils of self-regulated study. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 14(2), 219–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leme, V. B. R., Coimbra, S., Gato, J., Fontaine, A. M., & Del Prette, Z. A. P. (2013). Confirmatory factor analysis of the generalized self-efficacy scale in Brazil and Portugal. The Spanish Journal of Psychology, 16, E93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIntyre, S., Goldsmith, S., Webb, A., Ehlinger, V., Hollung, S. J., McConnell, K., Arnaud, C., Smithers-Sheedy, H., Oskoui, M., Khandaker, G., & Himmelmann, K. (2022). Global prevalence of cerebral palsy: A systematic analysis. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology, 64(12), 1494–1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moshman, D. (2018). Metacognitive theories revisited. Educational Psychology Review, 30(2), 599–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novak, I., McIntyre, S., Morgan, C., Campbell, L., Dark, L., Morton, N., Stumbles, E., Wilson, S.-A., & Goldsmith, S. (2013). A systematic review of interventions for children with cerebral palsy: State of the evidence. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology, 55(10), 885–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novak, I., Morgan, C., Fahey, M., Finch-Edmondson, M., Galea, C., Hines, A., Langdon, K., McNamara, M. M., Paton, M. C., Popat, H., Shore, B., Khamis, A., Stanton, E., Finemore, O. P., Tricks, A., Te Velde, A., Dark, L., Morton, N., & Badawi, N. (2020). State of the evidence traffic lights 2019: Systematic review of interventions for preventing and treating children with cerebral palsy. Current Neurology and Neuroscience Reports, 20(2), 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, R., Schwarzer, R., & Jerusalem, M. (1999). A escala de auto-eficácia geral percepcionada [The perceived general self-efficacy scale]. Available online: http://userpage.fu-berlin.de/~health/auto.htm (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Oliveira, A., Pereira, A., Núñez, J. C., Vallejo, G., Lopes, S., Guimarães, A., Abreu, R., & Rosário, P. (2024). Children with cerebral palsy rehabilitation in-session engagement: Lessons learnt from a story tool training program. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paparo, J., Beccaria, G., Canoy, D., Chur-Hansen, A., Conti, J. E., Correia, H., Dudley, A., Gooi, C., Hammond, S., Kavanagh, P. S., Monfries, M., Norris, K., Oxlad, M., Rooney, R. M., Sawyer, A., Sheen, J., Xenos, S., Yap, K., Thielking, M., & Australian Postgraduate Psychology Simulation Education Working Group (APPESWG). (2021). A new reality: The role of simulated learning activities in postgraduate psychology training programs. Frontiers in Education, 6, 653269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, A., Rosário, P., Lopes, S., Moreira, T., Magalhães, P., Núñez, J. C., Vallejo, G., & Sampaio, A. (2019). Promoting school engagement in children with cerebral palsy: A narrative based program. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(19), 3634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- QSR International. (2021). NVivo (Version 14) [Computer software].

- Rodrigues, F., Teixeira, D. S., Neiva, H. P., Cid, L., & Monteiro, D. (2025). Application of the hierarchical model of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation: A systematic review. Frontiers in Psychology, 16, 1512270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosário, P., Núñez, J. C., & Arias, A. V. (2016a). As incríveis aventuras de Anastácio, o explorador [The incredible adventures of Anastácio, the explorer]. Escola de Psicologia, Universidade do Minho. Available online: https://anastacio-projecto.weebly.com/as-incriacuteveis-aventuras-de-anastaacutecio-o-explorador.html (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Rosário, P., Núñez, J. C., Rodríguez, C., Cerezo, R., Fernández, E., Tuero, E., & Högemann, J. (2017). Analysis of instructional programs in different academic levels for improving self-regulated learning (SRL) through written text. In R. F. Redondo, K. Harris, & M. Braaksma (Eds.), Design principles for teaching effective writing (pp. 201–231). Brill. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosário, P., Núñez, J. C., Vallejo, G., Cunha, J., Azevedo, R., Rosáa, R., Nunes, A. R., Fuentes, S., & Moreira, T. (2016b). Promoting gypsy children school engagement: A story-tool project to enhance self-regulated learning. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 47, 84–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenbaum, P. L., Paneth, N., Leviton, A., Goldstein, M., Bax, M., Damiano, D., Dan, B., & Jacobsson, B. (2007). A report: The definition and classification of cerebral palsy April 2006. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology, 49, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schunk, D. H., & DiBenedetto, M. K. (2020). Motivation and social cognitive theory. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 60, 101832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, C. J., Watson MacDonell, K., & Moran, M. (2021). Provider self-efficacy in delivering evidence-based psychosocial interventions: A scoping review. Implementation Research and Practice, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, A., Dash, S. K., & Ashwani, K. (2023). Factors affecting transfer of online training: A systematic literature review and proposed taxonomy. Human Resource Development Quarterly, 34(4), 567–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitzmann, T., & Weinhardt, J. M. (2015). Training engagement theory: A multilevel perspective on the effectiveness of work-related training. Journal of Management, 44(2), 732–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skinner, E., Furrer, C., Marchand, G., & Kindermann, T. (2008). Engagement and disaffection in the classroom: Part of a larger motivational dynamic? Journal of Educational Psychology, 100(4), 765–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soderstrom, N. C., & Bjork, R. A. (2015). Learning versus performance: An integrative review. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 10(2), 176–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speckmann, F., & Unkelbach, C. (2024). Illusions of knowledge due to mere repetition. Cognition, 247, 105791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stadskleiv, K., Jahnsen, R., Andersen, G. L., & Von Tetzchner, S. (2018). Neuropsychological profiles of children with cerebral palsy. Developmental Neurorehabilitation, 21(2), 108–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tayyare, B. Ç., Gerçek, E., Dursun, E., & Akçin, N. (2023). Cerebral palsy and executive functions: Inhibitory control and cognitive flexibility skills. Psychology in the Schools, 60(12), 4859–4875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tschannen-Moran, M., & Hoy, A. W. (2001). Teacher efficacy: Capturing an elusive construct. Teaching and Teacher Education, 17(7), 783–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valle, A., Perez, J. C. N., Rodríguez, S., Cabanach, R. G., González Pienda, J. A. G., & Rosário, P. (2010). Perfiles motivacionales y diferencias en variables afectivas, motivacionales y de logro [Motivational profiles and differences in affective, motivational, and achievement variables]. Universitas Psychologica, 9(1), 109–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visoso, C. (2024). Self-efficacy literature review: Graduate students. Open Journal of Social Sciences, 12(03), 105–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wade, D. T. (2016). Rehabilitation—A new approach. Part four: A new paradigm, and its implications. Clinical Rehabilitation, 30(2), 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wade, D. T. (2020). What is rehabilitation? An empirical investigation leading to an evidence-based description. Clinical Rehabilitation, 34(5), 571–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, B. J., & Labuhn, A. S. (2012). Self-regulation of learning: Process approaches to personal development. In K. R. Harris, S. Graham, T. Urdan, C. B. McCormick, G. M. Sinatra, & J. Sweller (Eds.), APA educational psychology handbook, Vol. 1. Theories, constructs, and critical issues (pp. 399–425). American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoom Video Communications. (2011). Zoom® videoconferencing software (Version 5.0) [Computer software].

| Level | Module | Hours | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Motivation Self-Regulation Self-Determination Gamification Engagement in rehabilitation Parenting Narrative and narrative-based intervention | 20 h (16 synchronous hours + 4 asynchronous hours) | 60 h (44 synchronous + 16 asynchronous) |

| 2 | “The Incredibles Adventures of Anastácio, the Explorer”: Story “The Incredibles Adventures of Anastácio, the Explorer”: Program’s structure “The Incredibles Adventures of Anastácio, the Explorer”: Program’s methodological tools | 18 h (12 synchronous hours + 6 asynchronous hours) | |

| 3 | “The Incredibles Adventures of Anastácio, the Explorer”: Observation and analysis “The Incredibles Adventures of Anastácio, the Explorer”: Simulated learning | 22 h (16 synchronous hours + 6 asynchronous hours) |

| Characteristic | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Man | 1 | 5.9 |

| Woman | 16 | 94.1 |

| Age | ||

| <30 | 1 | 5.9 |

| 30–45 | 13 | 76.4 |

| 46–60 | 2 | 11.8 |

| >60 | 1 | 5.9 |

| Nationality | ||

| Portuguese | 17 | 100 |

| Academic qualifications | ||

| Bachelor’s degree | 6 | 35.3 |

| Master’s degree | 11 | 64.7 |

| Years of experience as a psychologist | ||

| <7 | 2 | 11.8 |

| 7–14 | 7 | 41.2 |

| 14–25 | 6 | 35.3 |

| >25 | 2 | 11.8 |

| Years of experience as a psychologist in a rehabilitation context | ||

| <7 | 5 | 29.4 |

| 7–14 | 8 | 47 |

| 14–25 | 2 | 11.8 |

| >25 | 2 | 11.8 |

| Previous training on the topics covered by the training program | ||

| Yes | 4 | 23.5 |

| No | 13 | 76.5 |

| Test | Value | F | Hypothesis df | Error df | Sig. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wilks’ Lambda | 0.929 | 0.572 | 2 | 15 | 0.576 |

| Mean | Std. Deviation | N | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Self-efficacy pre-test | 3.3765 | 0.41912 | 17 |

| Self-efficacy post-test 1 | 3.4118 | 0.38060 | 17 |

| Self-efficacy post-test 2 | 3.4471 | 0.31843 | 17 |

| Theme/Subtheme | Categories |

|---|---|

| Participants’ academic background and professional experience Previous training Previous experience with the tool Professional experience | Contributions Barriers |

| Features of the training model General Training Characteristics Level 1 Level 2 Level 3 | |

| Dispositional profiles Engagement Motivation |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the University Association of Education and Psychology. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Oliveira, A.; Castro, I.; Guimarães, A.; Vidal, S.; Carneiro, M.; Magalhães, B.; Rosário, P.; Pereira, A. Promoting Self-Regulation in Children with Cerebral Palsy: A Mixed Analysis of the Impact of a Training Program for Psychologists. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2025, 15, 120. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15070120

Oliveira A, Castro I, Guimarães A, Vidal S, Carneiro M, Magalhães B, Rosário P, Pereira A. Promoting Self-Regulation in Children with Cerebral Palsy: A Mixed Analysis of the Impact of a Training Program for Psychologists. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education. 2025; 15(7):120. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15070120

Chicago/Turabian StyleOliveira, André, Inês Castro, Ana Guimarães, Sofia Vidal, Maria Carneiro, Beatriz Magalhães, Pedro Rosário, and Armanda Pereira. 2025. "Promoting Self-Regulation in Children with Cerebral Palsy: A Mixed Analysis of the Impact of a Training Program for Psychologists" European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education 15, no. 7: 120. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15070120

APA StyleOliveira, A., Castro, I., Guimarães, A., Vidal, S., Carneiro, M., Magalhães, B., Rosário, P., & Pereira, A. (2025). Promoting Self-Regulation in Children with Cerebral Palsy: A Mixed Analysis of the Impact of a Training Program for Psychologists. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 15(7), 120. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15070120