Scale of Subtle Prejudices Towards Disability at the University: Validation in Mexican Population

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Prejudice Toward Disability in Higher Education

1.2. Measuring Attitudes and Prejudices Toward Disability

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedure

2.2. Measures

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Validity Evidence Based on Internal Structure

3.1.1. Exploratory Factor Analysis

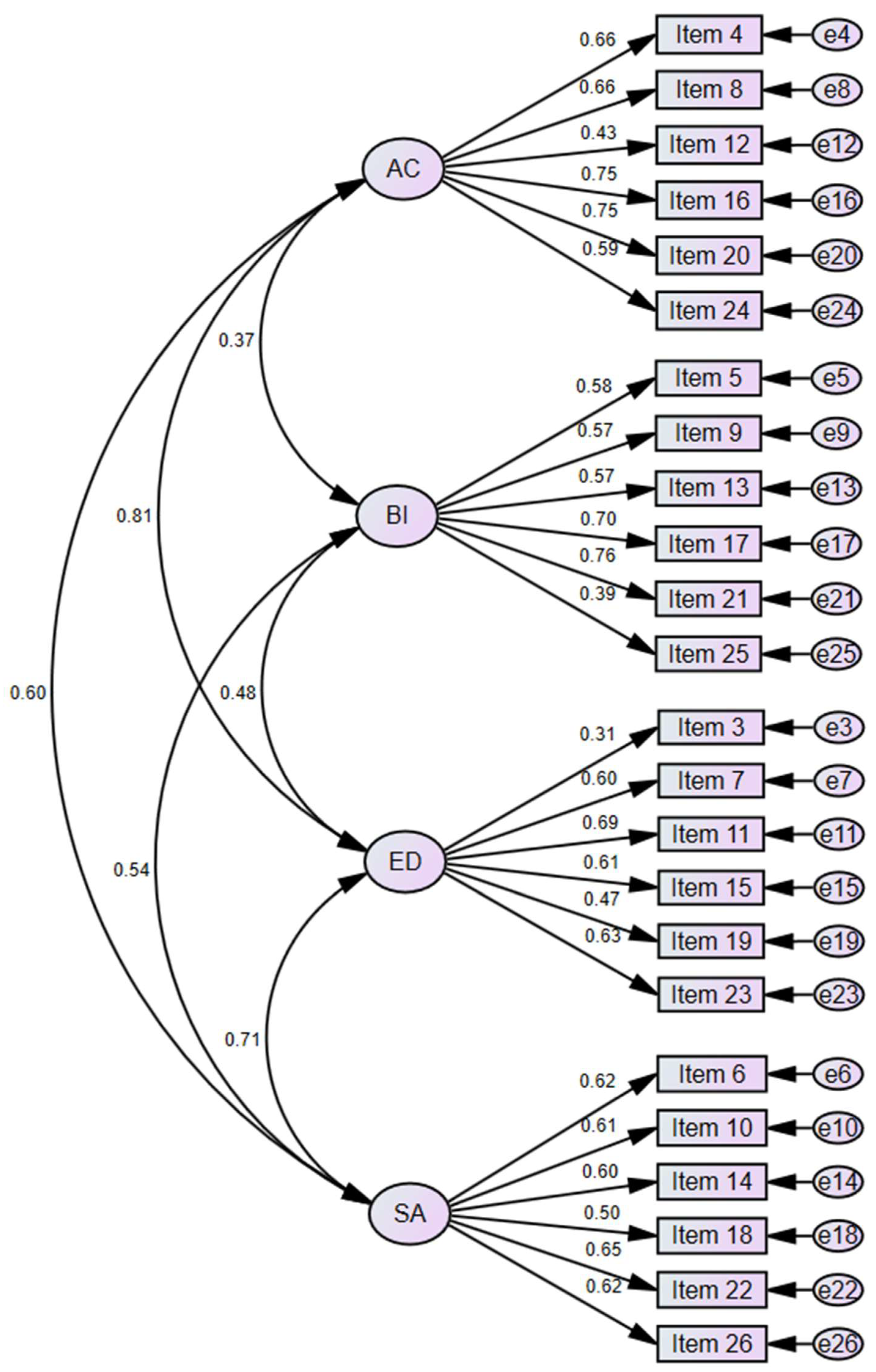

3.1.2. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

3.1.3. Comparison of Scores Across Factors

3.2. Validity Evidence Based on Relations to Other Variables

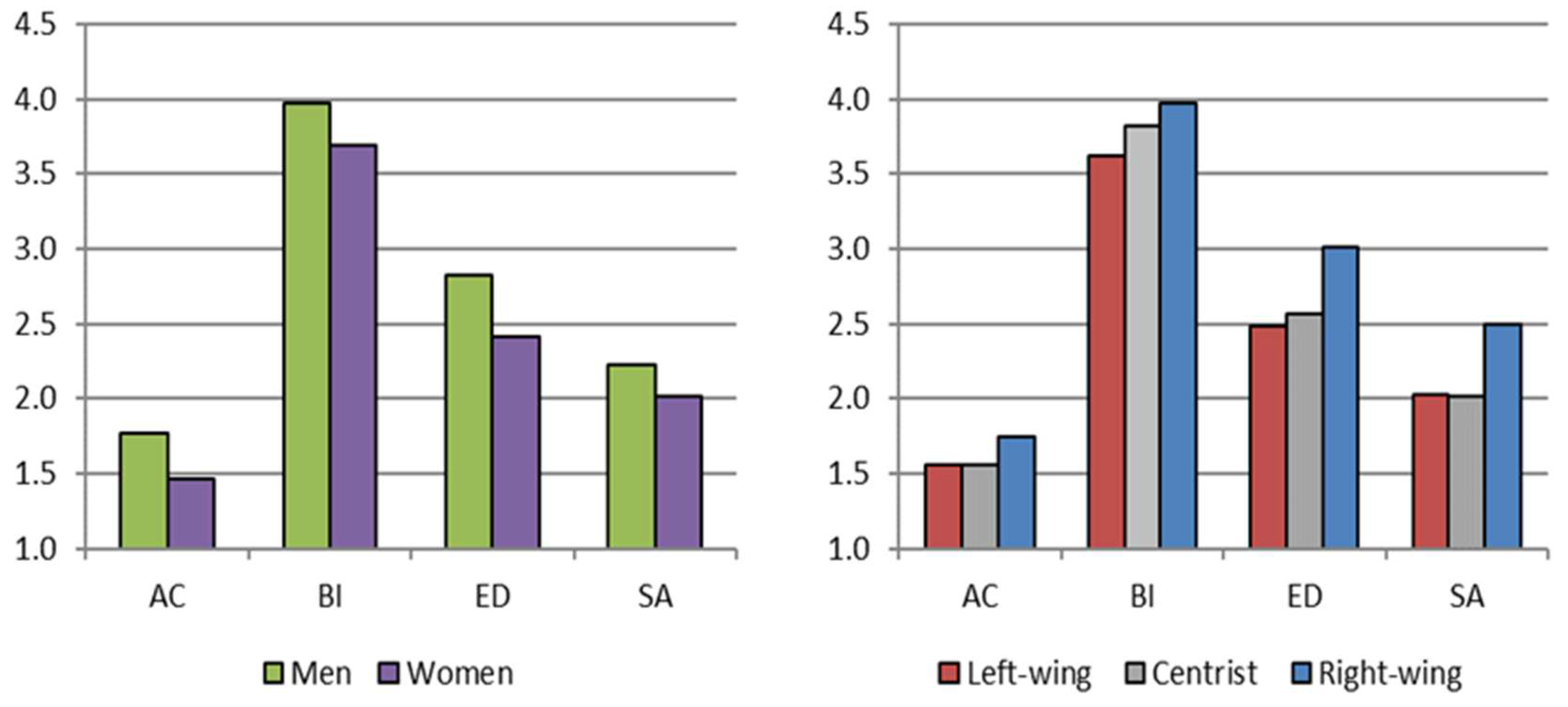

3.2.1. Relations to Sex and Political Opinion

3.2.2. Relations to the Opinion About University Policies for People with Disabilities

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| 1 = Total DESACUERDO 7 = Total ACUERDO | ||||||||

| 01 La libertad de expresión es un valor; por tanto debería ser políticamente correcto expresar cualquier opinión siempre que se haga respetuosamente. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

| 02 No debería ser un tabú hablar sobre la discapacidad; las personas deberían expresar libremente lo que piensan sobre este tema, como sobre cualquier otro. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

| 03 A las personas con discapacidad hay que ayudarlas demasiado para que salgan adelante. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

| 04 En general me incomoda interactuar con una persona con discapacidad. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

| 05 Las personas con discapacidad, en comparación con las demás personas, tienden a ser más compasivas por su discapacidad. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

| 06 Los estudiantes con discapacidad participan más en las clases que las estudiantes con discapacidad porque ellas son calladas y tímidas. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

| 07 La ayuda que requieren las personas con discapacidad para ingresar al mundo laboral implica una carga para las demás personas. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

| 08 Aunque no discrimino a las personas con discapacidad, he de reconocer que me intimida relacionarme con ellas. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

| 09 Las personas con discapacidad tienen unos valores que pocas personas suelen tener, precisamente por la vivencia de su discapacidad. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

| 10 Los estudiantes con discapacidad socializan más y mejor en el ambiente universitario que las estudiantes con discapacidad. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

| 11 Las personas con discapacidad no pueden valerse por sí mismas, siempre requieren ayuda de los demás. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

| 12 Me asusta la idea de tener que interactuar con una o un estudiante con discapacidad. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

| 13 La mayoría de las personas con discapacidad se caracterizan por una simpatía que pocas personas poseen. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

| 14 Los estudiantes con discapacidad pueden cursar más fácilmente carreras de tecnología y ciencias que las estudiantes con discapacidad, porque las mujeres tienen menor capacidad de abstracción. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

| 15 Es absurdo negar que las personas con discapacidad son un problema, pues es evidente que tienen limitaciones. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

| 16 Sinceramente, prefiero no relacionarme con personas con discapacidad. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

| 17 Las personas con discapacidad, en comparación con las que no tienen ningún tipo de discapacidad, tienden a tener mayor sensibilidad moral. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

| 18 Probablemente, las mujeres sufren la discapacidad más que los hombres pues para ellas es más importante su atractivo físico. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

| 19 Tener una discapacidad debe ser como tener una enfermedad. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

| 20 A pesar de que debemos respetar a las demás personas, siento incomodidad cuando hay un o una estudiante con discapacidad en mi aula. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

| 21 Las personas con discapacidad tienen una sensibilidad mayor que las demás, por la limitación que implica su discapacidad. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

| 22 Los recursos de la universidad son mejor aprovechados por los estudiantes con discapacidad que por las estudiantes con discapacidad, pues ellos tienen mejor rendimiento académico. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

| 23 Las personas con discapacidad no son autónomas; por eso demandan más ayuda. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

| 24 Si una persona acompaña a una persona con discapacidad prefiero comunicarme con ella que con la persona con discapacidad. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

| 25 Las personas con discapacidad deberían ser admiradas por lo que les implica vivir con una limitación. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

| 26 Para el personal docente es más problemático tener estudiantes mujeres con discapacidad pues tienen menor motivación para los estudios que los estudiantes con discapacidad. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

| Dimensions—Subscales: “Exceso de demandas” [excessive demands (ED)] = items 3, 7, 11, 15, 19, and 23; “Evitación de contacto” [avoidance of contact (AC)] = items 4, 8, 12, 16, 20, and 24; “Idealización benevolente” [benevolent idealization (BI)] = items 5, 9, 13, 17, 21, and 25; “Amplificación sexista” [sexist amplification (SA)] = items 6, 10, 14, 18, 22, and 26. | ||||||||

References

- American Educational Research Association, American Psychological Association & National Council on Measurement in Education. (2014). Standards for educational and psychological testing. American Educational Research Association. [Google Scholar]

- Arellano, A., Gaeta, M. L., Peralta, F., & Cavazos, J. (2019). Actitudes hacia la discapacidad en una universidad mexicana [Attitudes toward disability in a Mexican University]. Revista Brasileira de Educaçao, 24, e240023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, D. E. J., & Jackson, M. (2019). Benevolent and hostile sexism differentially predicted by facets of right-wing authoritarianism and social dominance orientation. Personality and Individual Differences, 139, 34–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barradas, M. E. (2014). Educación Superior Inclusiva en México: Una verdad a medias [Inclusive Higher Education in Mexico: A half truth]. Palibrio. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, N. (2020). Introduction: Theorizing ableism in academia. In N. Brown, & J. Leigh (Eds.), Ableism in Academia: Theorising experiencies of disabilities and cronic illnesses in high-education (pp. 1–10). University College London Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, N., & Leigh, J. (2020). Concluding thoughts: Moving forward. In N. Brown, & J. Leigh (Eds.), Ableism in Academia: Theorising experiencies of disabilities and cronic illnesses in high-education (pp. 226–236). University College London Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, F. K. (2001). Inciting legal fictions: “Disability’s” date with ontology and the ableist body of the law. Griffith Law Review, 10(1), 42–62. [Google Scholar]

- Cheung, G. W., Cooper-Thomas, H. D., Lau, R. S., & Wang, L. C. (2024). Reporting reliability, convergent and discriminant validity with structural equation modeling: A review and best-practice recommendations. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 41, 745–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christopher, A. N., & Mull, M. S. (2006). Conservative ideology and ambivalent sexism. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 30(2), 223–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cisternas, M., Trecan, S., & Tomás, R. (2022). Manual de prácticas docentes inclusivas: La discapacidad en educación superior [Manual of inclusive teaching practices: Disability in higher education]. Universidad Católica de Temuco. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Comité Español de Representantes de Personas con Discapacidad. (2023, February 2). Las “personas con discapacidad” reclaman ser llamadas así, como prescribe la Convención de la ONU [“Persons with disabilities” demand to be called in this way, as prescribed by the UN Convention]. CERMI diario. Available online: https://diario.cermi.es/entry/las-personas-con-discapacidad-reclaman-ser-llamadas-asi-como-prescribe-la-convencion-de-la-onu (accessed on 27 March 2024).

- Crenshaw, K. (1991). Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stanford Law Review, 43(6), 1241–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davaki, K., Marzo, C., Naminio, E., & Arvanitidou, M. (2013). Discrimination generated by the instersection of gender and disability. Publications Office of the European Union. Available online: https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2861/23765 (accessed on 28 March 2024).

- Davis, J., & Watson, N. (2001). Where are the children’s experiences? Analysing Social and cultural exclusion in “special” and “mainstream” schools. Disability & Society, 16(5), 671–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado-Álvarez, C., Gurdián-Fernández, A., Sánchez-Prada, A., & Vargas-Dengo, M. C. (2020). Evaluation of a model of prejudice toward persons with disabilities at the university. AERA Online Paper Repository, 1–16. Available online: https://www.aera.net/Publications/Online-Paper-Repository/AERA-Online-Paper-Repository-Viewer/ID/1573747 (accessed on 20 March 2024). [CrossRef]

- De Silva, R. (2008). Disability rights, gender, and development. A resource tool for action. United Nations, Wellesley Centers for Research on Women. Available online: https://www.un.org/disabilities/documents/Publication/UNWCW%20MANUAL.pdf (accessed on 28 March 2024).

- Dolmage, J. T. (2017). Academic ableism: Disability and higher education. University of Michigan Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Muñoz, A., & Durán-Rojas, D. (2020). Actuar-enseñar entre la diversidad: Construyendo educación inclusiva en atacama [Act-teach among diversity: Building inclusive education in atacama]. Revista Internacional de Educación para la Justicia Social, 9(2), 71–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrando, P. J., & Lorenzo-Seva, U. (2017). Program FACTOR at 10: Origins, development and future directions. Psicothema, 29(2), 236–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrando, P. J., Lorenzo-Seva, U., & Chico, E. (2009). A general factor-analytic procedure for assessing response bias in questionnaire measures. Structural Equation Modeling, 16(2), 364–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fichten, C., Nguyen, M., Budd, J., Asuncion, J., Tibbs, A., & Jorgensen, M. (2014). College and university students with disabilities: “Modifiable” personal and school related factors pertinent to grades and graduation. Journal of Postsecondary Education and Disability, 27(3), 273–290. [Google Scholar]

- Fiske, S. (2001). Social cognition. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Fontana, A., & Vargas, M. C. (2018). Percepciones sobre discapacidad: Implicaciones para la atención educativa del estudiantado de la Universidad Nacional de Costa Rica [Perceptions of disability: Implications for educational attention of students of the national university of costa rica]. Revista Electrónica Educare, 22(3), 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontana, A., Vargas, M. C., & Quirós, M. (2015). Construcciones sobre discapacidad y necesidades educativas e implicaciones en la respuesta educativa del estudiantado de la Universidad Nacional de Costa Rica (UNA) [Constructions on disability and educational needs and implications in the educational answer of the students of the National University of Costa Rica (UNA)]. In M. A. Verdugo, F. B. Jordán, T. Nieto, M. Crespo, D. Velázquez, E. Vicente, & V. Guillén (Eds.), Actas de las IX Jornadas científicas internacionales de investigación sobre personas con discapacidad. Instituto Universitario de Integración en la Comunidad, Universidad de Salamanca. Available online: https://inico.usal.es/cdjornadas2015/CD%20Jornadas%20INICO/cdjornadas-inico.usal.es/docs/103.pdf (accessed on 27 March 2024).

- Forero, C. G., Maydeu-Olivares, A., & Gallardo-Pujol, D. (2009). Factor analysis with ordinal indicators: A monte carlo study comparing DWLS and ULS estimation. Structural Equation Modeling, 16(4), 625–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frederick, J. (2019). Attitudes about disability and political participation since the 2016 U.S. presidential election [Doctoral dissertation, University of Michigan]. University of Michigan Library—Deep Blue Repository. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/2027.42/151386 (accessed on 22 January 2025).

- Friedman, C. (2019). Mapping ableism: A two-dimensional model of explicit and implicit disability attitudes. Canadian Journal of Disability Studies, 8(3), 95–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, C. (2024). Ableism and modern disability attitudes. In G. Bennett, & E. Goodall (Eds.), The palgrave encyclopedia of disability (pp. 1–14). Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentes, V., Pérez-Padilla, J., de la Fuente, Y., & Aranda, M. (2022). Creation and validation of the questionnaire on attitudes towards disability in higher education (QAD-HE) in Latin America. Higher Education Research & Development, 41(5), 1514–1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garabal-Barbeira, J., Espinosa, P., & Pousada, T. (2017). Influencia de la desconexicón moral y el prejuicio sobre la percepción de términos asociados a la discapacidad. Revista de Estudios e Investigación en Psicología y Educación, 8, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glick, P., & Fiske, S. (1996). The ambivalent sexism inventory: Differentiating hostile and benevolent sexism. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70(3), 491–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glick, P., & Fiske, S. T. (2001). An ambivalent alliance: Hostile and benevolent sexism as complementary justifications for gender inequality. American Psychologist, 56(2), 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glick, P., Fiske, S. T., Mladinic, A., Saiz, J. L., Abrams, D., Masser, B., Adetoun, B., Osagie, J. E., Akande, A., Alao, A., Annetje, B., Willemsen, T. M., Chipeta, K., Dardenne, B., Dijksterhuis, A., Wigboldus, D., Eckes, T., Six-Materna, I., Expósito, F., … López, W. L. (2000). Beyond prejudice as simple antipathy: Hostile and benevolent sexism across cultures. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79(5), 763–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gurdián-Fernández, A., Vargas-Dengo, M. C., Delgado-Álvarez, C., & Sánchez-Prada, A. (2020a). Prejuicios hacia las personas con discapacidad: Fundamentación teórica para el diseño de una escala. Revista Actualidades Investigativas en Educación, 20(1), 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurdián-Fernández, A., Vargas-Dengo, M. C., Delgado-Álvarez, C., & Sánchez-Prada, A. (2020b). Validación de una escala de prejuicios hacia las personas con discapacidad. Revista Actualidades Investigativas en Educación, 20(2), 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurdián-Fernández, A., Vargas-Dengo, M. C., Delgado-Álvarez, C., & Sánchez-Prada, A. (2020c). Prejudice toward disability at the university: Design of an assessment tool. AERA Online Paper Repository, 1–13. Available online: https://www.aera.net/Publications/Online-Paper-Repository/AERA-Online-Paper-Repository-Viewer/ID/1573727 (accessed on 20 March 2024). [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2010). Multivariate data analysis (7th ed.). Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43(1), 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6(1), 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía. (2022). Encuesta nacional sobre discriminación ENADIS. Presentación de resultados [National survey on discrimination ENADIS. Presentation of results]. Consejo Nacional para Prevenir la Discriminación (CONAPRED), Comisión Nacional de los Derechos Humanos (CNDH). Available online: https://www.inegi.org.mx/contenidos/programas/enadis/2022/doc/enadis2022_resultados.pdf (accessed on 27 March 2024).

- Izquierdo, I., Olea, J., & Abad, F. J. (2014). Exploratory factor analysis in validation studies: Uses and recommendations. Psicothema, 26(3), 395–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kane, M. (1992). An argument-based approach to validity. Psychological Bulletin, 112, 527–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kane, M. (2001). Current concerns in validity theory. Journal of Educational Measurement, 38, 319–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerschbaum, S. L., Eisenman, L. T., & Jones, J. M. (2017). Negotiating disability. Disclosure and higher education. University of Michigan Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lillywhite, A., & Wolbring, G. (2022). Undergraduate disabled students as knowledge producers including researchers: Perspectives of disabled students. Education Sciences, 12(2), 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzo-Seva, U., & Ferrando, P. J. (2006). FACTOR: A computer program to fit the exploratory factor analysis model. Behavior Research Methods, 38(1), 88–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mareño-Sempertegui, M. (2021). El capacitismo y su expresión en la educación superior [Ableism and its expression in higher education]. RAES Revista Argentina de Educación Superior, 13(23), 24–43. [Google Scholar]

- Mareño Sempertegui, M. (2023). La invención del ‘problema de la discapacidad’ en la Educación Superior Universitaria [The invention of the ‘disability problem’ in university higher education]. Trayectorias Universitarias, 9(16), e119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Cilleros, M. V., Sánchez-Gómez, M. C., Verdugo-Castro, S., & Verdugo-Alonso, M. A. (2020). Opiniones de la calidad de vida desde la perspectiva de la mujer con discapacidad [Views on quality of life as perceived by women with disabilities]. RISTI-Revista Ibérica de Sistemas e Tecnologias de Informação, 38, 64–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, R. P. (1999). Test theory: A unified treatment. Lawrence Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Meertens, R. W., & Pettigrew, T. F. (1997). Is subtle prejudice really prejudice? Public Opinion Quarterly, 61(1), 54–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mertens, D. M., Wilson, A., & Mounty, J. (2007). Gender equity for people with disabilities. In S. Klein, B. Richardson, D. A. Grayson, L. H. Fox, C. Kramarae, D. S. Pollard, & C. A. Dwyer (Eds.), Handbook for achieveing gender equity throught education (2nd ed., pp. 583–604). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Messick, S. (1989). Validity. In R. L. Linn (Ed.), Educational measurement (3rd ed., pp. 13–103). MacMillan. [Google Scholar]

- Messick, S. (1998). Test validity: A matter of consequence. Social Indicators Research, 45, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mireles, D. (2022). Theorizing racist ableism in higher education. Teachers College Record, 124(7), 17–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morata-Ramírez, M. A., & Holgado-Tello, F. P. (2013). Construct validity of likert scales through confirmatory factor analysis: A simulation study comparing different methods of estimation based on pearson and polychoric correlations. International Journal of Social Science Studies, 1(1), 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morata-Ramírez, M. A., Holgado-Tello, F. P., Barbero-García, I., & Méndez, G. (2015). Análisis factorial confirmatorio. Recomendaciones sobre mínimos cuadrados no ponderados en función del error tipo I de ji-cuadrado y RMSEA [Confirmatory factor analysis. Recommendations for unweighted least squares method related to Chi-Square and RMSEA type I error]. Acción Psicológica, 12(1), 79–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulaik, S. A., James, L. R., Van Alstine, J., Bennett, N., Lind, S., & Stilwell, C. D. (1989). Evaluation of goodness-of-fit indices for structural equation models. Psychological Bulletin, 105(3), 430–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nario-Redmond, M. R., Kemerling, A. A., & Silverman, A. (2019). Hostile, benevolent, and ambivalent ableism: Contemporary manifestations. Journal of Social Issues, 75(3), 726–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nario-Redmond, M. R., & Oleson, K. C. (2016). Disability group identification and disability-rights advocacy: Contingencies among emerging and other adults. Emerging Adulthood, 4(3), 207–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norgazaray, C. C., & Fraijo, J. A. (2022). Inclusión educativa de estudiantes con discapacidad en las instituciones de educación superior [Educational inclusion of students with disabilities in higher education institutions]. Fontamara—Universidad de Sonora. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J. C., & Bernstein, I. H. (1994). Psychometric theory (3rd ed.). McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Palacios, A. (2019). Perspectiva de discapacidad y derechos humanos en el contexto de una educación superior inclusiva [Disability and human rights perspective in the context of inclusive higher education]. Pensar. Revista de Ciencias Jurídidas, 24(4), 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Pettigrew, T. F., & Meertens, R. W. (2001). In defense of the subtle prejudice concept: A retort. European Journal of Social Psychology, 31(3), 299–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pineda, J. A., & Luna, A. (2018). Intersecciones de género y discapacidad. La inclusión laboral de mujeres con discapacidad. Sociedad y Economía, 35, 158–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Price, M. (2011). Mad at school. Rhetorics of mental disability and academic life. University of Michigan Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quiles, M. N. (2019). El estigma social. Convivir con la mirada del otro [The social stigma. Living with the gaze of the other]. Alianza Editorial. [Google Scholar]

- Quiles, M. N., & Morera, M. D. (2008). El estigma social. La diferencia que nos hace inferiores [Social stigma. The difference that makes us inferior]. In J. F. Morales, C. Huici, A. Gómez, & E. Gaviria (Coord.), Método, teoría e investigación en psicología social (pp. 377–400). Pearson Educación. [Google Scholar]

- Rey-Martínez, F. (2008). La discriminación múltiple, una realidad antigua, un concepto nuevo [Multiple discrimination, an old reality, a new concept]. Revista Española de Derecho Constitucional, 84, 251–283. [Google Scholar]

- Roca-Hurtuna, M., Martinez-Rico, G., Sanz, R., & Alguacil, M. (2021). Attitudes and work expectations of university students towards disability: Implementation of a training programme. International Journal of Instruction, 14(2), 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, S., & Ferreira, M. A. V. (2010). Desde la dis-capacidad hacia la diversidad funcional. Un ejercicio de dis-normalización [From dis-ability to functional diversity. An exercise in dys-normalization]. Revista Internacional De Sociología, 68(2), 289–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Martín, A., & Álvarez-Arregui, E. (2013). Development and validation of a scale to identify attitudes towards disability in Higher Education. Psicothema, 25(3), 370–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Martín, A., & Álvarez-Arregui, E. (2014). Estudiantes con discapacidad en la Universidad. Un estudio sobre su inclusión [University students with disabilities in Universities. A study of their inclusion]. Revista Complutense de Educación, 25(2), 457–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohmer, O., & Louvet, E. (2018). Implicit stereotyping against people with disability. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 21(1), 127–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romañach, J., & Lobato, M. (2009, July 26). Diversidad funcional, nuevo término para la lucha por la dignidad en la diversidad del ser humano [Functional diversity, a new term for the fight for dignity in the diversity of human beings]. Foro de Vida Independiente. Available online: http://forovidaindependiente.org/diversidad-funcional-nuevo-termino-para-la-lucha-por-la-dignidad-en-la-diversidad-del-ser-humano (accessed on 27 March 2024).

- Rönkkö, M., & Cho, E. (2022). An updated guideline for assessing discriminant validity. Organizational Research Methods, 25(1), 6–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sainz, M. Á., Vera, J. Á., Peña, M. O., & Tánori, J. (2022). Estado del arte: Actitudes hacia la discapacidad en instituciones de Educación Superior [State of the art: Attitudes towards disability in Higher Education institutions]. In C. C. Norzagaray, & J. A. Fraijo (Coord.), Inclusión educativa de estudiantes con discapacidad en las instituciones de Educación Superior (pp. 75–90). Fontamara—Universidad de Sonora. [Google Scholar]

- Sainz-Palafox, M. Á., Vera-Noriega, J. Á., & Tánori-Quintana, J. (2022). Características métricas de la escala de actitudes hacia las personas con discapacidad (EAPD) [Metric characteristics of the scale of attitudes towards persons with disabilities (SAPD)]. Revista Evaluar, 22(2), 14–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salinas, M. (2014). Actitudes de estudiantes sin discapacidad hacia la inclusión de estudiantes con discapacidad en educación superior [Attitudes of students without disabilities towards the inclusion of students with disabilities in higher education; Doctoral dissertation, Universidad Autónoma de Barcelona, Spain]. UAB—TDX Repository. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/10803/284953 (accessed on 22 January 2025).

- Schermelleh-Engel, K., Moosbrugger, H., & Müller, H. (2003). Evaluating the fit of structural equation models: Tests of significance and descriptive goodness-of-fit measures. Methods of Psychological Research, 8(2), 23–74. [Google Scholar]

- Shepard, L. A. (1997). The centrality of test use and consequences for test validity. Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice, 16(2), 5–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherry, M. (2016). Disability hate crimes: Does anyone really hate disabled people? Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solano-Flores, G., & Milbourn, T. (2016). Capacidad evaluativa, validez cultural, y validez consecuencial en PISA [Assessment capacity, cultural validity and consequential validity in PISA]. RELIEVE—Revista Electrónica de Investigación y Evaluación Educativa, 22(1), 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solano-Flores, G., & Nelson-Barber, S. (2001). On the cultural validity of science assessments. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 38(5), 553–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suriá, R. (2017). Creencias entre los estudiantes universitarios hacia la discapacidad: Análisis de su evolución entre generaciones [Beliefs among university students towards disability: Analysis of their evolution between generations]. Revista INFAD De Psicología. International Journal of Developmental and Educational Psychology, 4(1), 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suriá, R., Bueno, A., & Rosser, A. M. (2011). Prejuicios entre los estudiantes hacia las personas con discapacidad: Reflexiones a partir del caso de la Universidad de Alicante [Student prejudices towards people with disabilities: Reflections based on the case of the University of Alicante]. Alternativas. Cuadernos de Trabajo Social, 18, 75–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timmerman, M. E., & Lorenzo-Seva, U. (2011). Dimensionality assessment of ordered polytomous items with parallel analysis. Psychological methods, 16(2), 209–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timmons, S., McGinnity, F., & Carroll, E. (2024). Ableism differs by disability, gender and social context: Evidence from vignette experiments. The British Journal of Social Psychology, 63(2), 637–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vargas, M. C. (2013). Influencia de los prejuicios de un sector de la población universitaria respecto a la discapacidad en la construcción de una cultura institucional inclusiva [Influence of the prejudices of a sector of the university population regarding disability in the construction of an inclusive institutional culture; Doctoral dissertation, Universidad Nacional, Costa Rica]. SIIDCA-CSUCA Repository. Available online: https://catalogosiidca.csuca.org/Record/UCR.000024668?lng=en (accessed on 20 March 2024).

- Verdugo, M. A., Arias, B., & Jenaro, C. (1994). Actitudes hacia las personas con minusvalía [Attitudes towards people with disabilities]. Instituto Nacional de Servicios Sociales. [Google Scholar]

- Verdugo-Alonso, M. A., Crespo-Cuadrado, M., Caballo-Escribano, C., Sánchez-Gómez, M. C., Martín-Cilleros, M. V., & Sánchez-García, A. B. (2022). Analysis of discrimination and denial of the rights of women with disabilities with the help of the Nvivo Software. In A. P. Costa, A. Moreira, M. C. Sánchez-Gómez, & S. Wa-Mbaleka (Eds.), Computer supported qualitative research. WCQR 2022. Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems (vol. 466, pp. 227–247). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolbring, G., & Escobedo, M. (2023). Academic coverage of social stressors experienced by disabled people: A scoping review. Societies, 13(9), 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolbring, G., & Lillywhite, A. (2021). Equity/Equality, diversity, and inclusion (EDI) in Universities: The case of disabled people. Societies, 11(2), 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang-Wallentin, F., Jöreskog, K. G., & Luo, H. (2010). Confirmatory factor analysis of ordinal variables with misspecified models. Structural Equation Modeling, 17(3), 392–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuker, H. E., Block, J. R., & Younng, J. H. (1970). The measurement of attitudes toward disabled persons. Human Resources Center—U.S. Department of Health, Education & Welfare Office of Education. [Google Scholar]

| Variable | Category | n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | Men | 272 (45.3%) |

| Women | 319 (53.1%) | |

| No response | 10 (1.6%) | |

| Position at university | Student | 501 (83.4%) |

| Academic staff | 47 (7.9%) | |

| Administrative staff | 28 (4.7%) | |

| Other | 11 (1.8%) | |

| No response | 14 (2.2%) | |

| Field of knowledge | Health Sciences | 447 (74.4%) |

| Economics—Administration | 72 (12.0%) | |

| Technics | 61 (10.1%) | |

| Arts | 21 (3.5%) | |

| Political opinion | Right-wing | 104 (17.3%) |

| Centrist | 367 (61.1%) | |

| Left-wing | 78 (13.0%) | |

| No response | 52 (8.6%) |

| Item (Subscale) 1 | Factor 1 | Factor 2 | Factor 3 | Factor 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item 16 (AC) | 0.836 | −0.059 | −0.016 | 0.087 |

| Item 04 (AC) | 0.818 | 0.083 | −0.154 | −0.088 |

| Item 20 (AC) | 0.790 | 0.025 | 0.047 | 0.094 |

| Item 12 (AC) | 0.778 | −0.111 | 0.015 | 0.037 |

| Item 08 (AC) | 0.697 | −0.062 | 0.104 | 0.023 |

| Item 24 (AC) | 0.677 | 0.045 | 0.092 | 0.122 |

| Item 09 (BI) | 0.181 | 0.811 | −0.007 | −0.160 |

| Item 17 (BI) | −0.013 | 0.749 | −0.106 | 0.135 |

| Item 13 (BI) | −0.059 | 0.730 | −0.044 | 0.150 |

| Item 21 (BI) | 0.000 | 0.653 | 0.098 | 0.020 |

| Item 25 (BI) | −0.254 | 0.590 | 0.131 | 0.048 |

| Item 05 (BI) | 0.002 | 0.435 | 0.175 | 0.113 |

| Item 23 (ED) | 0.066 | 0.101 | 0.788 | −0.101 |

| Item 11 (ED) | −0.152 | −0.100 | 0.687 | 0.346 |

| Item 15 (ED) | 0.282 | 0.165 | 0.582 | −0.253 |

| Item 07 (ED) | 0.316 | 0.014 | 0.504 | −0.010 |

| Item 19 (ED) | 0.210 | −0.089 | 0.452 | 0.002 |

| Item 03 (ED) | −0.155 | 0.034 | 0.284 | 0.312 |

| Item 14 (SA) | 0.059 | −0.067 | −0.038 | 0.868 |

| Item 26 (SA) | 0.098 | −0.093 | 0.142 | 0.677 |

| Item 10 (SA) | 0.023 | 0.139 | −0.064 | 0.666 |

| Item 22 (SA) | 0.090 | 0.058 | 0.058 | 0.660 |

| Item 06 (SA) | 0.067 | 0.181 | −0.225 | 0.642 |

| Item 18 (SA) | 0.000 | 0.101 | 0.149 | 0.432 |

| Fit Index | Good/Acceptable Fit | 4 Factors | 3 Factors | 2 Factors |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GFI | ≥0.95/≥0.90 | 0.989 | 0.983 | 0.967 |

| AGFI | ≥0.90/≥0.85 | 0.983 | 0.977 | 0.960 |

| CFI | ≥0.97/≥0.95 | 0.997 | 0.987 | 0.961 |

| NNFI | ≥0.97/≥0.95 | 0.995 | 0.983 | 0.953 |

| RMSEA [95% CI] 1 | ≤0.05/≤0.08 | 0.024 [0.038, 0.072] | 0.045 [0.053, 0.088] | 0.074 [0.077, 0.109] |

| Fit Index | Good/Acceptable Fit | 4 Factors | 3 Factors | 2 Factors |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GFI | ≥0.95/≥0.90 | 0.953 | 0.951 | 0.928 |

| AGFI | ≥0.90/≥0.85 | 0.943 | 0.941 | 0.914 |

| PGFI | ≥0.50 | 0.782 | 0.789 | 0.776 |

| NFI | ≥0.95/≥0.90 | 0.920 | 0.916 | 0.876 |

| PNFI | ≥0.50 | 0.820 | 0.826 | 0.797 |

| SRMR | ≤0.05/≤0.08 | 0.067 | 0.070 | 0.083 |

| Factor | AC | BI | ED | SA |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AC | 0.423 | 0.134 | 0.664 | 0.358 |

| BI | 0.134 | 0.367 | 0.230 | 0.287 |

| ED | 0.664 | 0.230 | 0.323 | 0.498 |

| SA | 0.358 | 0.287 | 0.498 | 0.363 |

| Subscale | Group’s Mean (SD) | Effect | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Avoidance of Contact (AC) | Men: 1.77 (1.03) Women: 1.46 (0.73) | F (1, 537) = 16.092; p < 0.001; η2 = 0.029 |

| Benevolent Idealization (BI) | Men: 3.97 (1.29) Women: 3.69 (1.26) | F (1, 537) = 6.071; p = 0.014; η2 = 0.011 | |

| Excessive Demands (ED) | Men: 2.82 (1.14) Women: 2.41 (0.92) | F (1, 537) = 21.988; p < 0.001; η2 = 0.039 | |

| Sexist Amplification (SA) | Men: 2.22 (1.11) Women: 2.02 (0.93) | F (1, 537) = 5.286; p = 0.022; η2 = 0.010 | |

| Political opinion | Avoidance of Contact (AC) | Right-wing: 1.75 (1.08) Centrist: 1.56 (0.83) Left-wing: 1.56 (0.85) | H (2) = 1.990; p = 0.370 |

| Benevolent Idealization (BI) | Right-wing: 3.97 (1.22) Centrist: 3.82 (1.30) Left-wing: 3.62 (1.28) | H (2) = 2.362; p = 0.307 | |

| Excessive Demands (ED) | Right-wing: 3.01 (1.11) Centrist: 2.56 (1.02) Left-wing: 2.48 (1.10) | H (2) = 16.927; p < 0.001 | |

| Sexist Amplification (SA) | Right-wing: 2.49 (1.06) Centrist: 2.02 (0.95) Left-wing: 2.03 (0.96) | H (2) = 18.365; p < 0.001 |

| Avoidance of Contact | Benevolent Idealization | Excessive Demands | Sexist Amplification | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Opinion about the most appropriate policies | 0.113 ** | 0.124 ** | 0.152 *** | 0.068 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the University Association of Education and Psychology. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sánchez-Prada, A.; Delgado-Álvarez, C.; Gurdián-Fernández, A. Scale of Subtle Prejudices Towards Disability at the University: Validation in Mexican Population. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2025, 15, 51. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15040051

Sánchez-Prada A, Delgado-Álvarez C, Gurdián-Fernández A. Scale of Subtle Prejudices Towards Disability at the University: Validation in Mexican Population. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education. 2025; 15(4):51. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15040051

Chicago/Turabian StyleSánchez-Prada, Andrés, Carmen Delgado-Álvarez, and Alicia Gurdián-Fernández. 2025. "Scale of Subtle Prejudices Towards Disability at the University: Validation in Mexican Population" European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education 15, no. 4: 51. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15040051

APA StyleSánchez-Prada, A., Delgado-Álvarez, C., & Gurdián-Fernández, A. (2025). Scale of Subtle Prejudices Towards Disability at the University: Validation in Mexican Population. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 15(4), 51. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15040051