Exploring Traditional and Cyberbullying Profiles in Omani Adolescents: Differences in Internalizing/Externalizing Symptoms, Prosocial Behaviors, and Academic Performance

Abstract

1. Introduction

Aims of This Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedure

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Adolescent Peer Relations Instrument (APRI; Parada, 2000)

2.2.2. Revised Cyber Bullying Inventory-II (RCBI-II; Topcu & Erdur-Baker, 2018)

2.2.3. The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ; R. Goodman, 1997)

2.2.4. Academic Performance

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

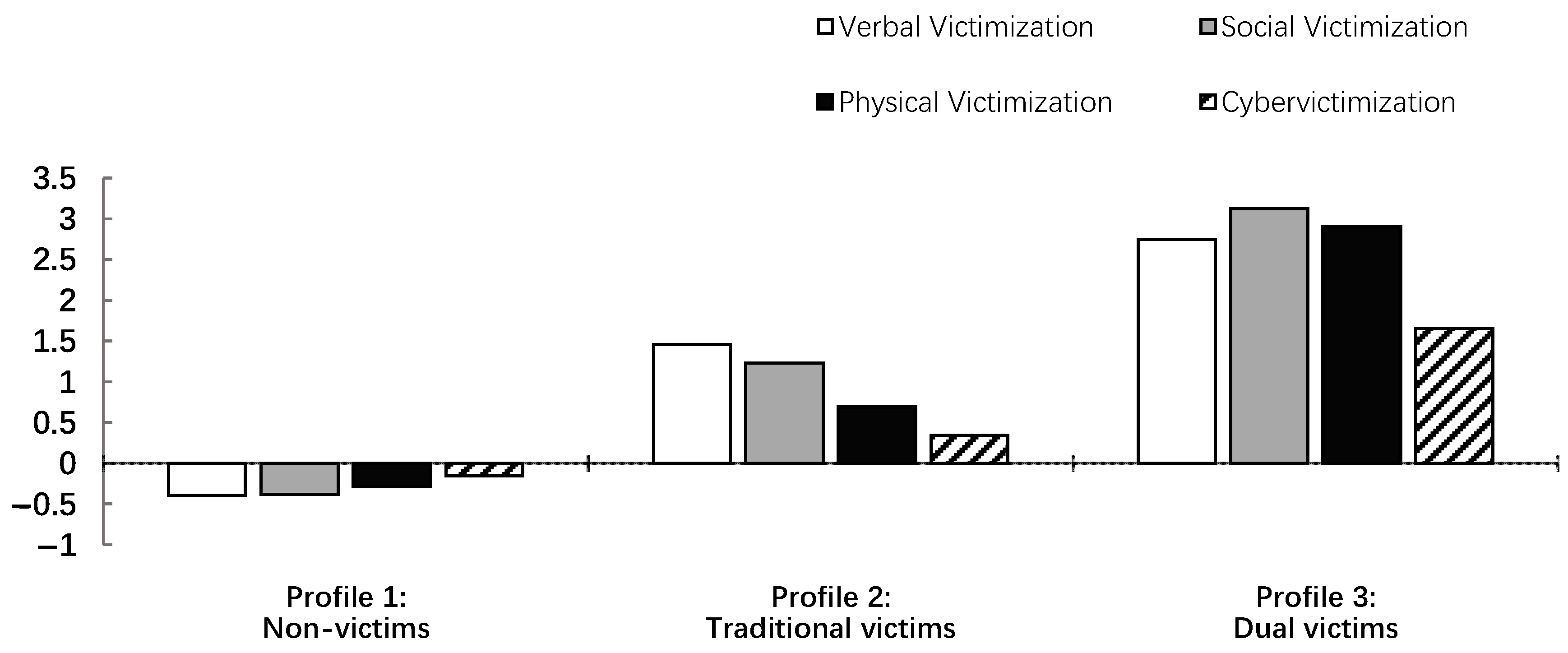

3.1. The Identified Victimization Profiles

3.2. The Victimization Profiles and Profile Differences

4. Discussion

5. Limitations of This Study and Future Research

Practical Implications

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| TB | Traditional Bullying |

| CB | Cyberbullying |

| LPA | Latent Profile Analysis |

| GSHS | Global School-based Students Health Survey |

| APRI | Adolescent Peer Relations Instrument |

| RCBI-II | Revised Cyberbullying Inventory-II |

| SDQ | Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire |

| GPA | Grade Point Average |

| SPSS | Statistical Package for the Social Sciences |

| AIC | Akaike Information Criterion |

| BIC | Bayesian Information Criterion |

| aBIC | Adjusted Bayesian Information Criterion |

| LMR | Lo–Mendell–Rubin Adjusted Likelihood Ratio Test |

References

- Abdalmaleki, E., Abdi, Z., Isfahani, S. R., Safarpoor, S., Haghdoost, B., Sazgarnejad, S., & Ahmadnezhad, E. (2022). Global school-based student health survey: Country profiles and survey results in the eastern Mediterranean region countries. BMC Public Health, 22(1), 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AlBuhairan, F., Abou Abbas, O., El Sayed, D., Badri, M., Alshahri, S., & De Vries, N. (2017). The relationship of bullying and physical violence to mental health and academic performance: A cross-sectional study among adolescents in Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. International Journal of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, 4(2), 61–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Saadoon, M., Eltayib, R. A. A., Alhaj, A. H., Chan, M. F., Aldhafri, S., & Al-Adawi, S. (2024). The perception and roles of school mental health professionals regarding school bullying (Suluk Audwani) in Oman: A qualitative study in an urban setting. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 21(8), 991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amin, A. N., Supartini, Y., Tambunan, E. S., Sulastri, T., Ningsih, R., & Hapsari, D. C. (2024). Analysis of factors that influence bullying behavior in adolescents in public middle school in East Jakarta Region. Jurnal Keperawatan, 9(2), 282–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asparouhov, T., & Muthén, B. (2014). Auxiliary variables in mixture modeling: Using the BCH method in Mplus to estimate a distal outcome model and an arbitrary secondary model. Mplus Web Notes, 21(2), 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, B., & Lin, W. Y. (2015). How do victims react to cyberbullying on social networking sites? The influence of previous cyberbullying victimization experiences. Computers in Human Behavior, 52, 458–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casper, D. M., & Card, N. A. (2017). Overt and relational victimization: A meta-analytic review of their overlap and associations with social–psychological adjustment. Child Development, 88(2), 466–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, X., & Chen, Z. (2024). The associations between parenting and bullying among children and adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 54(4), 928–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chudal, R., Tiiri, E., Brunstein Klomek, A., Ong, S. H., Fossum, S., Kaneko, H., Kolaitis, G., Lesinskiene, S., Li, L., Huong, M. N., Praharaj, S. K., Sillanmäki, L., Slobodskaya, H. R., Srabstein, J. C., Wiguna, T., Zamani, Z., Sourander, A., & Eurasian Child Mental Health Study (EACMHS) Group. (2021). Victimization by traditional bullying and cyberbullying and the combination of these among adolescents in 13 European and Asian countries. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 31, 1391–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eastman, M., Foshee, V., Ennett, S., Sotres-Alvarez, D., Reyes, H. L. M., Faris, R., & North, K. (2018). Profiles of internalizing and externalizing symptoms associated with bullying victimization. Journal of Adolescence, 65, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eisenberg, N., Fabes, R. A., & Spinrad, T. L. (2006). Prosocial behavior. In N. Eisenberg, W. Damon, & R. M. Lerner (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology: Social, emotional, and personality development (6th ed., Vol. 3, pp. 646–718). Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Elgar, F. J., Napoletano, A., Saul, G., Dirks, M. A., Craig, W., Poteat, V. P., & Koenig, B. W. (2014). Cyberbullying victimization and mental health in adolescents and the moderating role of family dinners. JAMA Pediatrics, 168(11), 1015–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fabris, M. A., Badenes-Ribera, L., & Longobardi, C. (2021). Bullying victimization and muscle dysmorphic disorder in Italian adolescents: The mediating role of attachment to peers. Children and Youth Services Review, 120, 105720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabris, M. A., Longobardi, C., Morese, R., & Marengo, D. (2022). Exploring multivariate profiles of psychological distress and empathy in early adolescent victims, bullies, and bystanders involved in cyberbullying episodes. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(16), 9871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabris, M. A., Settanni, M., Longobardi, C., & Marengo, D. (2023). Sense of belonging at school and on social media in adolescence: Associations with educational achievement and psychosocial maladjustment. Child Psychiatry & Human Development, 55, 1620–1633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, B. W., Gardella, J. H., & Teurbe-Tolon, A. R. (2016). Peer cybervictimization among adolescents and the associated internalizing and externalizing problems: A meta-analysis. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 45, 1727–1743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X., Li, S., Shen, C., Zhu, K., Zhang, M., Liu, Y., & Zhang, M. (2023). Effect of prosocial behavior on school bullying victimization among children and adolescents: Peer and student–teacher relationships as mediators. Journal of Adolescence, 95(2), 322–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallego-Jiménez, M. G., & Rodríguez Otero, L. M. (2025). Adicción a internet y ciberbullying en alumnado español de formación profesional. Health and Addictions/Salud y Drogas, 25(1), 54–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardella, J. H., Fisher, B. W., & Teurbe-Tolon, A. R. (2017). A systematic review and meta-analysis of cyber-victimization and educational outcomes for adolescents. Review of Educational Research, 87(2), 283–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, J., Bao, L., Wang, J., Wei, X., Zeng, P., & Lei, L. (2022). The maladaptive side of Internet altruists: Relationship between Internet altruistic behavior and cyberbullying victimization. Children and Youth Services Review, 134, 106362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginanjar, Y. E., Yahya, M., & Samana, A. (2024). Development of an integrative learning model for character education based on islamic values of the koran and hadith in boarding school. Journal of Multidisciplinary Academic and Practice Studies, 2(2), 147–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gini, G., Card, N. A., & Pozzoli, T. (2018). A meta-analysis of the differential relations of traditional and cyber-victimization with internalizing problems. Aggressive Behavior, 44(2), 185–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodman, A., Lamping, D. L., & Ploubidis, G. B. (2010). When to use broader internalising and externalising subscales instead of the hypothesised five subscales on the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ): Data from British parents, teachers and children. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 38(8), 1179–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodman, R. (1997). The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire: A research note. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 38, 581–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellström, L., Thornberg, R., & Espelage, D. L. (2021). Definitions of bullying. In The Wiley Blackwell handbook of bullying: A comprehensive and international review of research and intervention (Vol. 1, pp. 2–21). John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Holfeld, B., & Mishna, F. (2019). Internalizing symptoms and externalizing problems: Risk factors for or consequences of cyber victimization? Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 48, 567–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadambaa, A., Thomas, H. J., Scott, J. G., Graves, N., Brain, D., & Pacella, R. (2019). Prevalence of traditional bullying and cyberbullying among children and adolescents in Australia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 53(9), 878–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, S., Kyrrestad, H., & Fossum, S. (2020). Cyberbullying status and mental health in Norwegian adolescents. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 61(5), 707–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keith, S., Scheuerman, H. L., & Smith, A. L. (2025). Going viral: Investigating the short-and long-term traumatic effects of cyberbullying victimization on adolescents in schools. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokkinos, C. M., & Kipritsi, E. (2012). The relationship between bullying, victimization, trait emotional intelligence, self-efficacy and empathy among preadolescents. Social Psychology of Education, 15, 41–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. Y., Chung, I. J., & Miller, D. B. (2022). The developmental trajectories of prosocial behavior in adolescence: A growth-mixture model. Child Indicators Research, 15(1), 161–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C., Wang, P., Martin-Moratinos, M., Bella-Fernández, M., & Blasco-Fontecilla, H. (2024). Traditional bullying and cyberbullying in the digital age and its associated mental health problems in children and adolescents: A meta-analysis. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 33(9), 2895–2909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S., Longobardi, C., Fabris, M. A., & Settanni, M. (2025). Being kicked out of a WhatsApp group: Frequency and association with adolescents’ psychosocial well-being and School Achievement. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 42(1), 318–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S., Longobardi, C., Mastrokoukou, S., & Fabris, M. A. (2024). Bullying victimization and psychological adjustment in Chinese students: The mediating role of teacher–student relationships. School Psychology International, 46(1), 68–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longobardi, C., Badenes-Ribera, L., Fabris, M. A., Martinez, A., & McMahon, S. D. (2019a). Prevalence of student violence against teachers: A meta-analysis. Psychology of Violence, 9(6), 596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longobardi, C., Morese, R., & Fabris, M. A. (2020). COVID-19 emergency: Social distancing and social exclusion as risks for suicide ideation and attempts in adolescents. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 551113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longobardi, C., Prino, L. E., Fabris, M. A., & Settanni, M. (2017). School violence in two Mediterranean countries: Italy and Albania. Children and Youth Services Review, 82, 254–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longobardi, C., Prino, L. E., Fabris, M. A., & Settanni, M. (2019b). Violence in school: An investigation of physical, psychological, and sexual victimization reported by Italian adolescents. Journal of School Violence, 18(1), 49–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longobardi, C., Settanni, M., Lin, S., & Fabris, M. A. (2021). Student–teacher relationship quality and prosocial behaviour: The mediating role of academic achievement and a positive attitude towards school. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 91(2), 547–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marciano, L., Schulz, P. J., & Camerini, A. L. (2020). Cyberbullying perpetration and victimization in youth: A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 25(2), 163–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marengo, D., Jungert, T., Iotti, N. O., Settanni, M., Thornberg, R., & Longobardi, C. (2018). Conflictual student–teacher relationship, emotional and behavioral problems, prosocial behavior, and their associations with bullies, victims, and bullies/victims. Educational Psychology, 38(9), 1201–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marengo, D., Settanni, M., Fabris, M. A., & Longobardi, C. (2021). Alone, together: Fear of missing out mediates the link between peer exclusion in WhatsApp classmate groups and psychological adjustment in early-adolescent teens. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 38(4), 1371–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marengo, D., Settanni, M., Mastrokoukou, S., Fabris, M. A., & Longobardi, C. (2024). Social Media Linked to early adolescent suicidal thoughts via cyberbullying and internalizing symptoms. International Journal of Bullying Prevention, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, H. W., Lüdtke, O., Trautwein, U., & Morin, A. J. S. (2009). Classical latent profile analysis of academic self-concept dimensions: Synergy of person-and variable-centered approaches to theoretical models of self-concept. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 16(2), 191–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modecki, K. L., Minchin, J., Harbaugh, A. G., Guerra, N. G., & Runions, K. C. (2014). Bullying prevalence across contexts: A meta-analysis measuring cyber and traditional bullying. Journal of Adolescent Health, 55(5), 602–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, S. E., Norman, R. E., Suetani, S., Thomas, H. J., Sly, P. D., & Scott, J. G. (2017). Consequences of bullying victimization in childhood and adolescence: A systematic review and meta-analysis. World Journal of Psychiatry, 7(1), 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morese, R., Fabris, M. A., Longobardi, C., & Marengo, D. (2024). Involvement in cyberbullying events and empathy are related to emotional responses to simulated social pain tasks. Digital Health, 10, 20552076241253085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nylund-Gibson, K., & Choi, A. Y. (2018). Ten frequently asked questions about latent class analysis. Translational Issues in Psychological Science, 4(4), 440–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ossa, F. C., Jantzer, V., Neumayer, F., Eppelmann, L., Resch, F., & Kaess, M. (2023). Cyberbullying and school bullying are related to additive adverse effects among adolescents. Psychopathology, 56(1–2), 127–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parada, R. (2000). Adolescent peer relations instrument: A theoretical and empirical basis for the measurement of participant roles in bullying and victimisation of adolescence: An interim test manual and a research monograph: A test manual. Publication Unit, Self-concept Enhancement and Learning Facilitation (SELF) Research Centre, University of Western Sydney. [Google Scholar]

- Pengpid, S., & Peltzer, K. (2023). Combined victimization of face-to-face and cyberbullying and adverse health outcomes among school-age adolescents in Argentina. Psychology, Health & Medicine, 28(8), 2261–2272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prino, L. E., Longobardi, C., Fabris, M. A., Parada, R. H., & Settanni, M. (2019). Effects of bullying victimization on internalizing and externalizing symptoms: The mediating role of alexithymia. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 28, 2586–2593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ran, H., Yang, Q., Fang, D., Che, Y., Chen, L., Liang, X., Sun, H., Peng, J., Wang, S., & Xiao, Y. (2023). Social indicators with serious injury and school bullying victimization in vulnerable adolescents aged 12–15 years: Data from the Global School-Based Student Survey. Journal of affective disorders, 324, 469–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reinecke, J. (2006). Longitudinal Analysis of Adolescents’ Deviant and Delinquent Behavior. Methodology, 2(3), 100–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rostam-Abadi, Y., Stefanovics, E. A., & Potenza, M. N. (2024). An exploratory study of the prevalence and adverse associations of in-school traditional bullying and cyberbullying among adolescents in Connecticut. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 173, 372–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saleem, S., Khan, N. F., Zafar, S., & Ahmed, M. (2025). Cyberbullying victimization among university students—A national study of Pakistan. Security Journal, 38(1), 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samara, M., Da Silva Nascimento, B., El-Asam, A., Hammuda, S., & Khattab, N. (2021). How can bullying victimisation lead to lower academic achievement? A systematic review and meta-analysis of the mediating role of cognitive-motivational factors. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(5), 2209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, S. K., O’donnell, L., Stueve, A., & Coulter, R. W. (2012). Cyberbullying, school bullying, and psychological distress: A regional census of high school students. American Journal of Public Health, 102(1), 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahrour, G., Dardas, L. A., Al-Khayat, A., & Al-Qasem, A. (2020). Prevalence, correlates, and experiences of school bullying among adolescents: A national study in Jordan. School Psychology International, 41(5), 430–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobol, M., Przepiórka, A., & Błachnio, A. (2025). Factors contributing to the defending behavior of adolescent cyberbystanders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Computers in Human Behavior, 162, 108463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, H. J., Connor, J. P., & Scott, J. G. (2015). Integrating traditional bullying and cyberbullying: Challenges of definition and measurement in adolescents—A review. Educational Psychology Review, 27, 135–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, K. J., & McCuddy, T. (2020). Affinity, affiliation, and guilt: Examining between-and within-person variability in delinquent peer influence. Justice Quarterly, 37(4), 715–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornton, E., Panayiotou, M., & Humphrey, N. (2024). Prevalence, inequalities, and impact of bullying in adolescence: Insights from the# BeeWell study. International Journal of Bullying Prevention, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topcu, Ç., & Erdur-Baker, Ö. (2018). RCBI-II: The second revision of the revised cyber bullying inventory. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development, 51(1), 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valente, J. Y., Ferreira-Junior, V., Paiva de Oliveira Galvão, P., de la Torre, A., & Sanchez, Z. M. (2024). Psychiatric symptoms as predictors of latent classes of bullying victimization and perpetration among early adolescents. Current Psychology, 43(1), 204–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Völlink, T., Bolman, C. A., Dehue, F., & Jacobs, N. C. (2013). Coping with cyberbullying: Differences between victims, bully-victims and children not involved in bullying. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 23(1), 7–24. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C., Li, B., Zhang, L., Liu, Y., & Xu, P. (2024). Prosocial behavior and teachers’ attitudes towards bullying on peer victimization among middle school students: Examining the cross-level moderating effect of classroom climate. School Psychology Review, 53(5), 579–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z., Cheng, L., Xie, Z., & Jiang, C. (2024). Cyberbullying victimization and perpetration: The influence on cyberostracism and youth anxiety. Behavioral Sciences & the Law, 42(4), 461–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, M. F. (2015). Adolescents’ cyber aggression perpetration and cyber victimization: The longitudinal associations with school functioning. Social Psychology of Education, 18, 653–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Frequency | Percentage | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Father education | Cannot read and write | 26 | 2.2% |

| Primary school | 138 | 11.5% | |

| Secondary school | 916 | 76.1% | |

| College | 78 | 6.5% | |

| Postgraduate | 46 | 3.8% | |

| Mother education | Cannot read and write | 8 | 0.7% |

| Primary school | 40 | 3.3% | |

| Secondary school | 1044 | 86.7% | |

| College | 111 | 9.2% | |

| Postgraduate | 1 | 0.1% | |

| Monthly income A | 325–500 | 44 | 3.7% |

| 501–900 | 313 | 26.0% | |

| 901–1200 | 606 | 50.3% | |

| 1201 and above | 241 | 20.0% | |

| Parent status | Live together | 1199 | 99.6% |

| Divorced | 5 | 0.4% |

| Number of Profiles | AIC | BIC | aBIC | Entropy | LMR | BLRT | Smallest Profile |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| One Profile | 28,873.906 | 28,914.653 | 28,889.242 | – | – | – | 100% (n = 1204) |

| Two Profiles | 26,341.997 | 26,408.212 | 26,366.918 | 0.989 | 2472.204 *** | 2541.909 *** | 0.15532 (n = 187) |

| Three Profiles | 25,401.787 | 25,493.468 | 25,436.293 | 0.979 | 924.154 ** | 950.210 *** | 0.04900 (n = 59) |

| Four Profiles | 25,041.278 | 25,158.427 | 25,085.370 | 0.983 | 950.210 | 370.509 *** | 0.01246 (n = 15) |

| Five Profiles | 24,692.513 | 24,835.128 | 24,746.189 | 0.982 | 348.928 | 358.766 *** | 0.01163 (n = 14) |

| M (SD) | Mean Difference | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcomes | Profile 1: Non-Victims (n = 989) | Profile 2: Traditional Victims (n = 156) | Profile 3: Dual Victims (n = 59) | Overall Test Wald’s χ2 (df = 2) | Pairwise Comparison |

| SDQ_Internalizing symptoms | 10.14 (0.11) | 10.76 (0.26) | 11.94 (0.34) | 25.32 *** | P3 > P2 > P1 |

| SDQ_Externalizing symptoms | 10.36 (0.10) | 9.94 (0.20) | 12.81 (0.38) | 44.16 *** | P3 > P2, P3 > P1, P2 ≈ P1 |

| SDQ_Prosocial behaviors | 4.71 (0.08) | 4.94 (0.17) | 5.63 (0.36) | 7.68 * | P3 > P1, P1 ≈ P2, P2 ≈ P3 |

| GPA | 4.59 (0.02) | 4.31 (0.08) | 4.37 (0.11) | 14.19 ** | P1 > P2, P1 > P3, P2 ≈ P3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the University Association of Education and Psychology. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Al Saidi, A.; Longobardi, C.; Fabris, M.A.; Mastrokoukou, S.; Lin, S. Exploring Traditional and Cyberbullying Profiles in Omani Adolescents: Differences in Internalizing/Externalizing Symptoms, Prosocial Behaviors, and Academic Performance. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2025, 15, 100. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15060100

Al Saidi A, Longobardi C, Fabris MA, Mastrokoukou S, Lin S. Exploring Traditional and Cyberbullying Profiles in Omani Adolescents: Differences in Internalizing/Externalizing Symptoms, Prosocial Behaviors, and Academic Performance. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education. 2025; 15(6):100. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15060100

Chicago/Turabian StyleAl Saidi, Ahmed, Claudio Longobardi, Matteo Angelo Fabris, Sofia Mastrokoukou, and Shanyan Lin. 2025. "Exploring Traditional and Cyberbullying Profiles in Omani Adolescents: Differences in Internalizing/Externalizing Symptoms, Prosocial Behaviors, and Academic Performance" European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education 15, no. 6: 100. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15060100

APA StyleAl Saidi, A., Longobardi, C., Fabris, M. A., Mastrokoukou, S., & Lin, S. (2025). Exploring Traditional and Cyberbullying Profiles in Omani Adolescents: Differences in Internalizing/Externalizing Symptoms, Prosocial Behaviors, and Academic Performance. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 15(6), 100. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15060100