Effect of an Educational Intervention on Pupil’s Knowledge, Attitudes, Perceptions, and Behavior on Air Pollution in Public Schools in Pristina

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

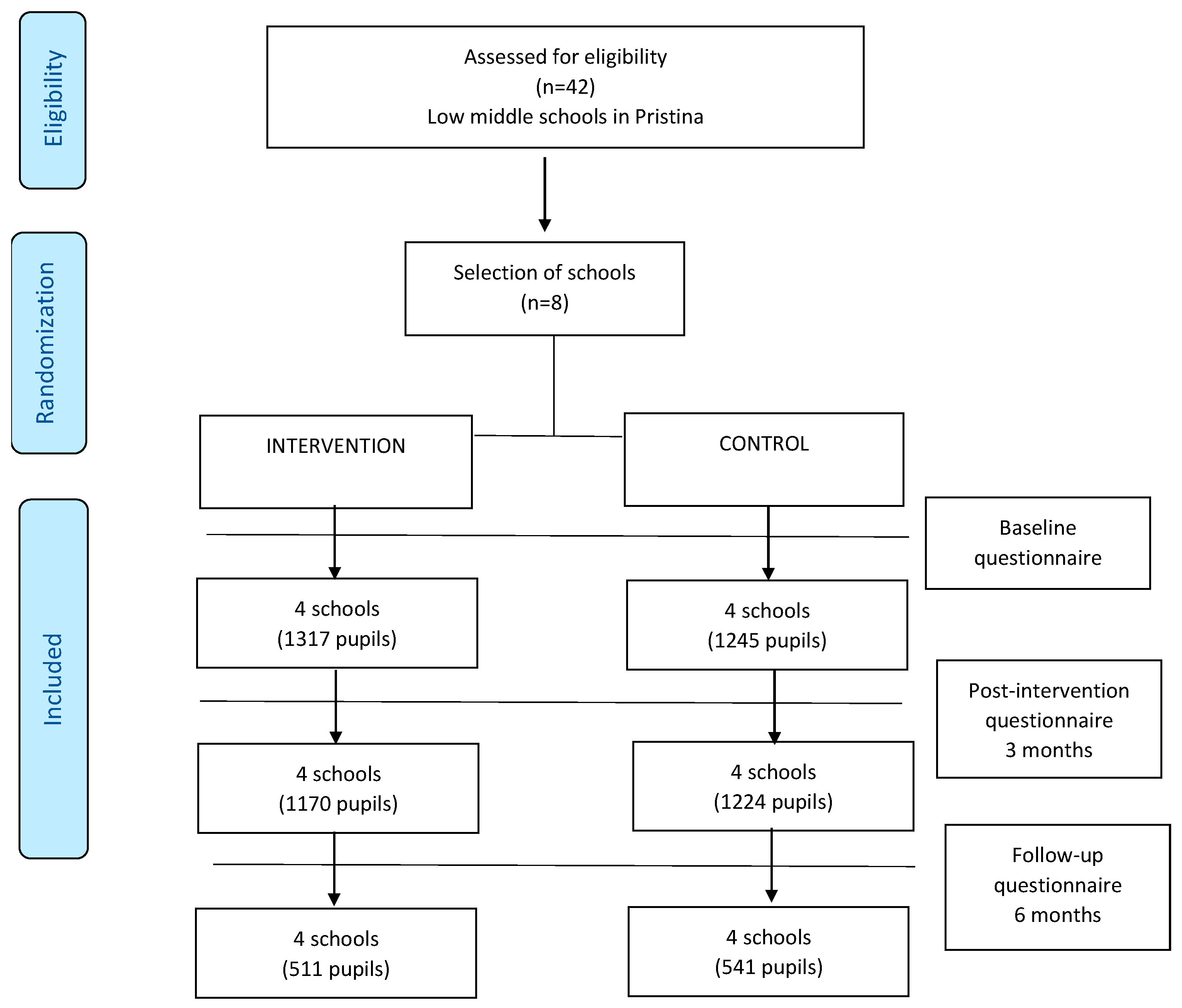

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Description of Intervention

2.4. Instrument and Construction of Scores

2.5. Data Collection

2.6. Statistical Analysis

2.7. Ethical Approval

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

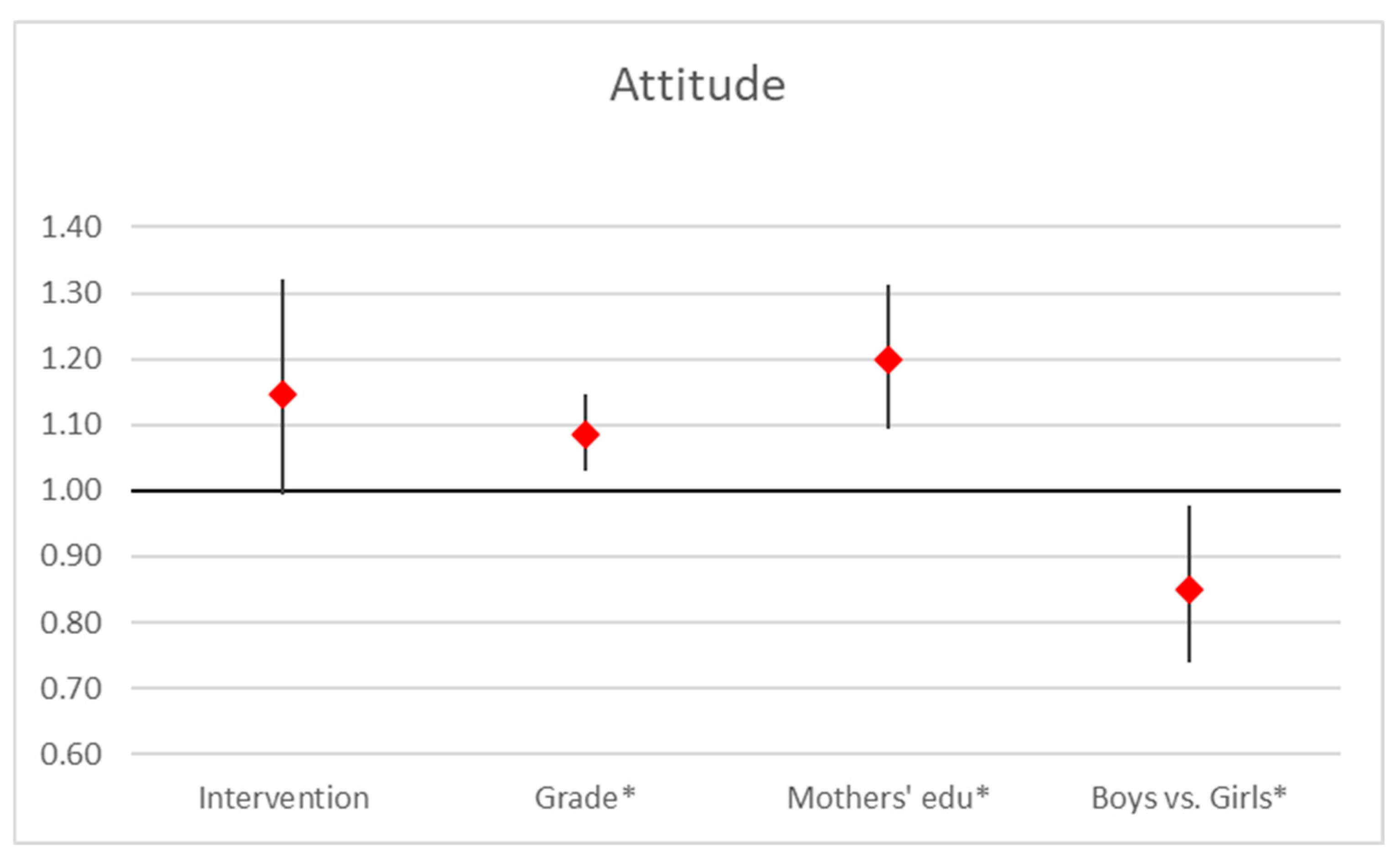

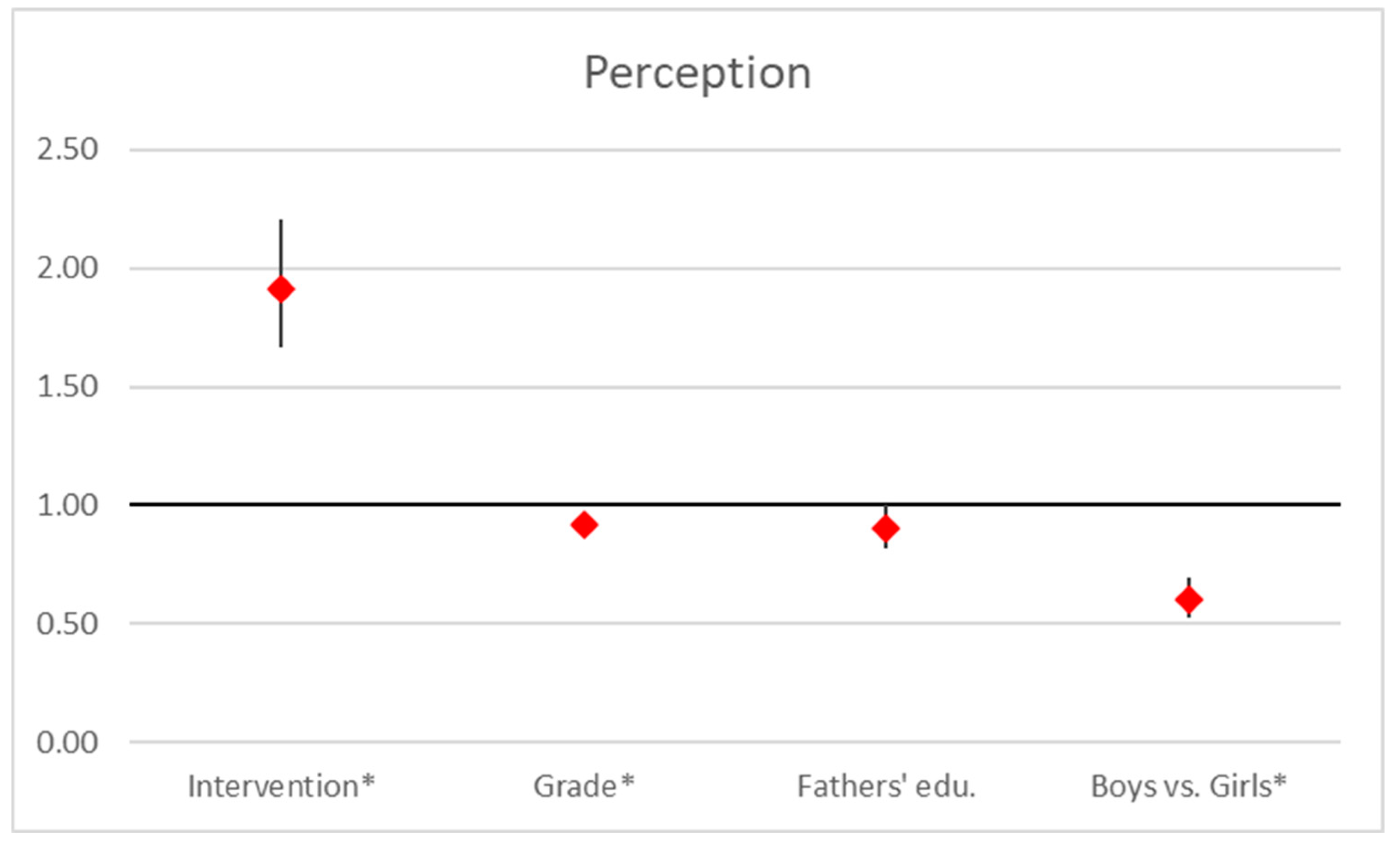

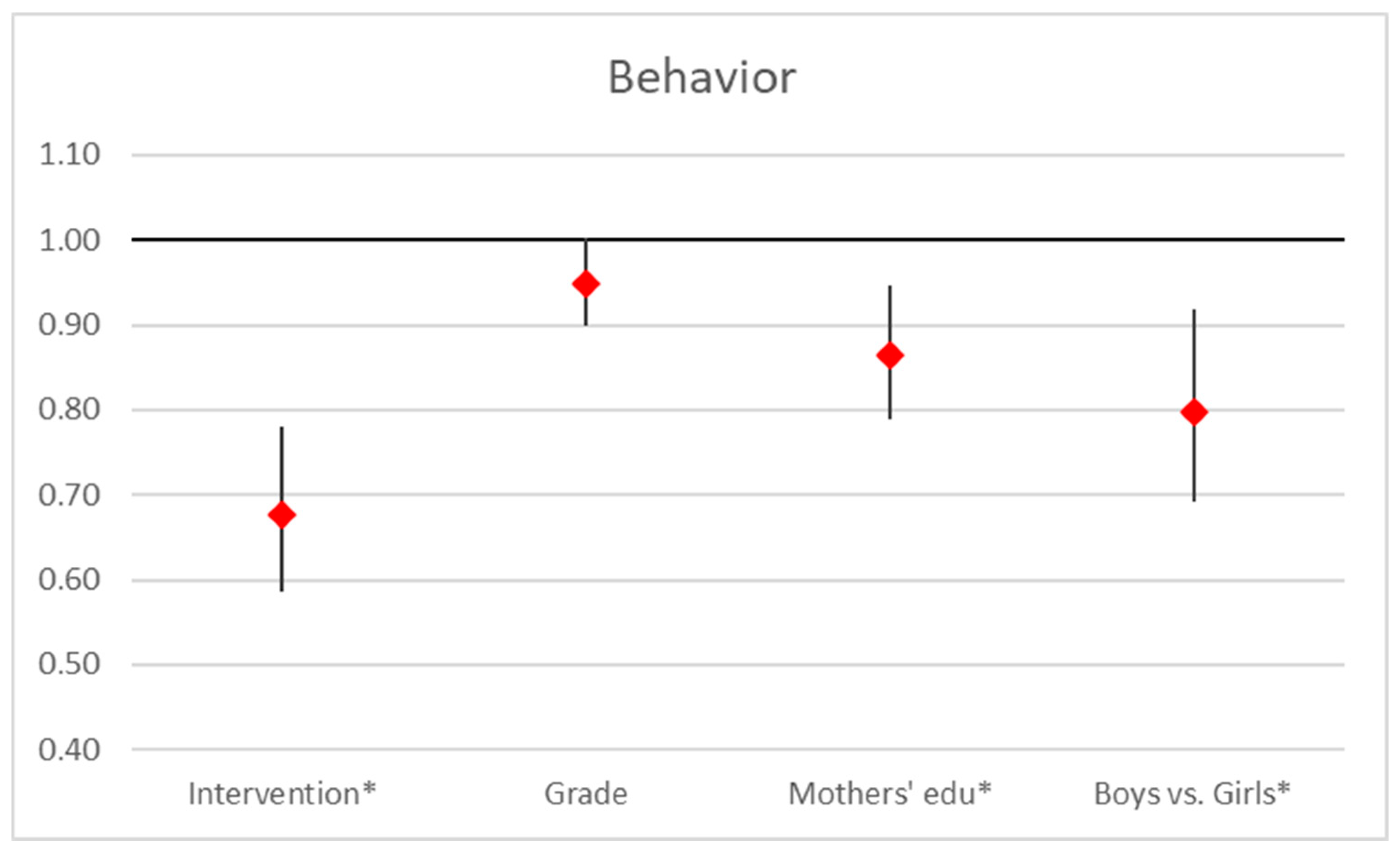

3.2. Regression Analysis

3.3. Follow-Up Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Knowledge Questions | Correct | Wrong | Do Not Know | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| What is the main cause of air pollution in Pristina? * | 575 | 1169 | 648 | |||

| Natural phenomena (e.g., fires) are responsible for almost 50% of air pollution in Kosovo. | 462 | 1232 | 698 | |||

| The smallest dust particles that can get deeper into the lungs are: | 1055 | 1120 | 217 | |||

| The greatest contribution to air pollution in Pristina is: | 1122 | 1077 | 193 | |||

| PM 2.5 in Kosovo often comes from combustion and heating from houses, dirty chimneys, high-emission power plants, and diesel vehicles. * | 1042 | 962 | 388 | |||

| Ground-level ozone plays a protective role, protecting the Earth from harmful rays and ultraviolet radiation. * | 691 | 1332 | 369 | |||

| The elderly and children have a higher risk of suffering adverse health effects from air pollution than young adults. | 1203 | 922 | 267 | |||

| All people face the same risk of suffering adverse health effects from air pollution. * | 739 | 1450 | 203 | |||

| Health problems caused by air pollution can cause premature death. | 1243 | 705 | 444 | |||

| What diseases are caused by air pollution? | 1831 | 286 | 275 | |||

| The faster you drive, the finer particles will be transmitted or released into the air. | 1409 | 417 | 566 | |||

| When air pollution in Pristina is very high, staying indoors can protect you from its harmful effects. | 1402 | 426 | 564 | |||

| I know how to find out about air quality in my community. * | 983 | 169 | 1240 | |||

| * Not used for the final score | ||||||

| Attitude Questions | Do not agree at all | Do not agree | Not sure | Agree | Completely agree | |

| Traffic jams can increase small inhalable dust locally. | 262 | 115 | 621 | 603 | 791 | |

| People should pay more attention to how to reduce their individual contribution to air pollution. | 495 | 201 | 301 | 569 | 826 | |

| Polluted air (fog/smog) bothers me, but I do not think it poses a health risk. * | 402 | 510 | 558 | 489 | 433 | |

| Air pollution should be considered as a serious threat to the future development of society. | 141 | 163 | 555 | 734 | 799 | |

| * Coded in reverse order: Completely agree/Agree/Not sure/Not agree/Not agree at all | ||||||

| Perception Questions | Not at all | Not dangerous | Not sure | Dangerous | Very dangerous | |

| Air pollution (AP) is dangerous to my health. | 210 | 211 | 371 | 587 | 1013 | |

| AP caused by heating and cooking is dangerous. | 217 | 324 | 790 | 630 | 431 | |

| AP caused by industry is dangerous. | 149 | 146 | 571 | 810 | 716 | |

| AP caused by transport is dangerous. | 189 | 233 | 734 | 827 | 409 | |

| How often do you notice AP? * | 79 | 185 | 303 | 392 | 688 | 745 |

| How concerned are you about AP in your area? ** | 175 | 648 | 816 | 753 | ||

| Have you had difficulty breathing in the last month? * | 705 | 380 | 286 | 201 | 392 | 428 |

| * Coded: Never/Once a month or less/Several times a month/Once a week/Several times a week/Every day. ** Coded: Not at all/A little/Somewhat/A lot.1 | ||||||

| Behavior Questions (last month)2 | Never | Rare | Sometimes | Always | ||

| In the last month, how often have you used public transport, walked or cycled instead of driving? | 184 | 700 | 612 | 896 | ||

| In the last month, how often have you reduced energy consumption (e.g., turned off the lights, turned off the air conditioner, etc.)? | 466 | 693 | 696 | 537 | ||

| In the last month, how often have you reduced your outdoor activities to avoid air pollution?3 | 316 | 779 | 833 | 464 | ||

| 1 | Distinction between attitudes and perceptions based on the questions provided: Attitudes reflect a pupil’s beliefs and feelings about air pollution, particularly their views on its seriousness and the responsibility for addressing it. For example, the questions “People should pay more attention to how to reduce their individual contribution to air pollution” and “Air pollution should be considered a serious threat to the future development of society” assess attitudes, as they focus on how strongly individuals believe air pollution is a problem and their responsibility in mitigating it. On the other hand, perceptions are about how pupils assess the risks or presence of air pollution in their environment. Questions like “Air pollution (AP) is dangerous to my health”, “How often do you notice AP?” and “How concerned are you about AP in your area?” focus on perceptions, as they gauge how individuals perceive the health risks and the visibility of air pollution in their surroundings. In short, in our study attitudes are concerned with beliefs and responsibility, while perceptions are about risk awareness and environmental observation. |

| 2 | We grouped the two types of behavior—environmental protection and health protection—together under the broader category of ‘behavior and practices’ for the purpose of survey clarity and ease of analysis. While these behaviors serve distinct purposes, both fall within the domain of individual actions and choices aimed at improving personal and collective well-being. |

| 3 | The pre-test data were not used for direct comparison between the control and intervention groups because the pre-test was administered to the entire sample of participants as a whole, not to the two groups separately. Therefore, it was not possible to assess differences between the control and intervention groups at the pre-test stage. Instead, we focused on the comparison between the control and intervention groups at the post-test (and/or follow-up test), as the primary goal was to assess the effects of the intervention. Additionally, the pre-test served as a baseline for the entire sample, and we assumed that any differences between the groups at the post-test would reflect the impact of the intervention, assuming that the groups were similar at baseline. |

References

- Adejoke, O. C., Mji, A., & Mukhola, M. S. (2014). Students’ and teachers’ awareness of and attitude towards environmental pollution: A multivariate analysis using biographical variables. Journal of Human Ecology, 45, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S., Adnan, M., Janssens, D., & Wets, G. (2020). A route to school informational intervention for air pollution exposure reduction. Sustainable Cities and Society, 53, 101965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alp, E., Ertepinar, H., Tekkaya, C., & Yilmaz, A. (2006). A statistical analysis of children’s environmental knowledge and attitudes in Turkey. International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education, 15(3), 210–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atlantic Council. (n.d.). Western Balkans must pursue more competitive energy sectors. Atlantic Council. Available online: https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/in-depth-research-reports/issue-brief/western-balkans-must-pursue-more-competitive-energy-sectors/ (accessed on 6 August 2024).

- Augustine, J. M., Cavanagh, S. E., & Crosnoe, R. (2009). Maternal education, early child care, and the reproduction of advantage. Social Forces, 88(1), 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berenguer, J., Corraliza, J. A., & Martin, R. (2005). Rural-urban differences in environmental concern, attitudes, and actions. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 21(2), 128–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergman, B. G. (2016). Assessing impacts of locally designed environmental education projects on students’ environmental attitudes, awareness and intention to act. Environmental Education Research, 22(4), 480–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burger, J., & Gochfeld, M. (2018). Environmental education and attitudes. In R. B. Bechtel, & A. Churchman (Eds.), Encyclopedia of environmental health (2nd ed., pp. 346–353). Elsevier. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/referencework/9780444639523/encyclopedia-of-environmental-healt (accessed on 29 April 2024).

- Burns, J., Boogaard, H., Polus, S., Pfadenhauer, L. M., Rohwer, A. C., Van Erp, A. M., Turley, R., & Rehfuess, E. A. (2020). Interventions to reduce ambient air pollution and their effects on health: An abridged Cochrane systematic review. Environmental International, 135, 105400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catlin, J. R., & Wang, Y. (2013). Recycling gone bad: When the option to recycle increases resource consumption. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 23(1), 122–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collado, S., Corraliza, J. A., Staats, H., & Ruiz, M. (2015). Effect of frequency and mode of contact with nature on children’s self-reported ecological behaviors. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 43, 148–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courtenay-Hall, P., & Rogers, L. (2022). Gaps in mind: Problems in environmental knowledge-behavior modeling research. Environmental Education Research, 8(3), 283–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çakar, H., Güneş, A., & Erdoğan, N. (2012). Investigation into environmental awareness of grade school students in Bayındır, Izmir. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/287933150_Investigation_into_Environmental_Awareness_of_Grade_School_Students_in_Bayindir_Izmir (accessed on 14 November 2024).

- de Pauw, J. B., & van Petegem, P. (2011). The effect of Flemish eco-schools on student environmental knowledge, attitudes, and affect. International Journal of Science Education, 33(10), 1513–1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisler, A. D., Eisler, H., & Yoshida, M. (2003). Perception of human ecology: Cross-cultural and gender comparisons. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 23(1), 89–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Environment Agency. (2019). Air quality in Europe—2019 report. European Environment Agency. Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/publications/air-quality-in-europe-2019 (accessed on 6 August 2024).

- European Environment Agency. (n.d.). How air pollution affects our health. European Environment Agency. Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/en/topics/in-depth/air-pollution/eow-it-affects-our-health (accessed on 6 August 2024).

- Fan, S., Yuan, Z., Liao, X., Tu, H., Lan, G., Maddock, J. E., & Lu, Y. (2017). A study of parents’ perception of air pollution and its effect on their children’s respiratory health in Nanchang, China. Journal of Environmental Health, 79(7), E1–E9. [Google Scholar]

- Gaudiano, M. G., & Ortega, A. (2009). Perfiles educativos (Vol. XXXI, pp. 58–68). Perfiles Educativos. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Gaudiano, E. (2007). Educación ambiental: Trayectorias, rasgos y escenarios. Plaza y Valdés & Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León. [Google Scholar]

- Imperial College London. (2024). Reducing air pollution: How can changing behaviors help? Imperial News. Available online: https://www.imperial.ac.uk/news/230817/reducing-pollution-changing-behaviours-help/ (accessed on 5 September 2024).

- Iwaniec, J., & Curdt-Christiansen, X. L. (2020). Parents as agents: Engaging children in environmental literacy in China. Sustainability, 12(12), 6605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kesenheimer, J. S., & Greitemeyer, T. (2020). Ego or Eco? Neither ecological nor egoistic appeals of persuasive climate change messages impacted pro-environmental behavior. Sustainability, 12(23), 10064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollmuss, A., & Agyeman, J. (2002). Mind the gap: Why do people act environmentally and what are the barriers to pro-environmental behavior? Environmental Education Research, 8(3), 239–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krnel, D., & Naglic, S. (2009). Environmental literacy comparison between eco-schools and ordinary schools in Slovenia. Science Education International, 20(1), 5–24. [Google Scholar]

- Kubinger, K. D. (2005). Psychological test calibration using the Rasch model—Some critical suggestions on traditional approaches. International Journal of Testing, 5(4), 377–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marín, D., Calle, N., Arango, V., Betancur, P., Pérez, M., Orozco, L. Y., Marín-Ochoa, B., Ceballos, J. C., López, L., & Rueda, Z. V. (2024). Knowledge, attitudes and practices about air pollution and its health effects in 6th to 11th-grade students in Colombia: A cross-sectional study. Frontiers in Public Health, 12, 1390780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mashaba, E. K., Maile, S., & Manaka, M. J. (2022). Learners’ knowledge of environmental education in selected primary schools of the Tshwane North District, Gauteng Province. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(23), 15552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masykuroh, K., Yetti, E., & Nurani, Y. (2022). The role of parents in raising children’s environmental awareness and attitudes. Educational Administration: Theory and Practice, 28(1), 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarron, A., Semple, S., Braban, C. F., Swanson, V., Gillespie, C., & Price, H. D. (2023). Public engagement with air quality data: Using health behavior change theory to support exposure-minimizing behaviors. Journal of Exposure Science & Environmental Epidemiology, 33, 321–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naquin, M., Cole, D., Bowers, A., & Walkwitz, E. (2011). Environmental health knowledge, attitudes, and practices of students in grades four through eight. ICHPER-SD Journal of Research, 6(1), 45–50. [Google Scholar]

- Olsson, D., Gericke, N., & Chang Rundgren, S. N. (2016). The effect of implementation of education for sustainable development in Swedish compulsory schools—Assessing pupils’ sustainability consciousness. Environmental Education Research, 22(2), 176–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otto, S., & Pensini, P. (2017). Nature-based environmental education of children: Environmental knowledge and connectedness to nature, together, are related to ecological behavior. Global Environmental Change, 47, 88–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özsoy, S., & Ahi, B. (2014). Elementary school students’ perceptions of the future environment through artwork. Educational Sciences: Theory & Practice, 14(45), 1570–1582. Available online: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1045119 (accessed on 29 April 2024).

- Pauw, J. B., & van Petegem, P. (2013). The effect of eco-schools on children’s environmental values and behavior. Journal of Biological Education, 47(2), 96–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prince, S. E., Muskin, S. E., Kramer, S. J., Huang, S., Blakey, T., & Rappold, A. G. (2024). Smoke on the horizon: Leveling up citizen and social science to motivate health protective responses during wildfires. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 11(1), 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez, A. S., Ramondt, S., Van Bogart, K., & Perez-Zuniga, R. (2019). Public awareness of air pollution and health threats: Challenges and opportunities for communication strategies to improve environmental health literacy. Journal of Health Communication, 24(1), 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasch, G. (1960). Probabilistic model for some intelligence and achievement tests. Danish Institute for Educational Research. [Google Scholar]

- Robina-Ramírez, R., & Medina-Merodio, J. A. (2019). Transforming students’ environmental attitudes in schools through external communities. Journal of Cleaner Production, 232, 629–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Mallen, I., Barraza, L., Bodenhorn, B., & Reyes-García, V. (2009). Evaluating the impact of an environmental education programme: An empirical study in Mecixo. Environmental Education Research, 15(3), 371–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneller, A. J. (2008). Environmental service learning: Outcomes of innovative pedagogy. Environmental Education Research, 14(3), 291–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schraufnagel, D. E., Balmes, J. R., Cowl, C. T., De Matteis, S., Jung, S. H., Mortimer, K., Perez-Padilla, R., Rice, M. B., Riojas-Rodriguez, H., Sood, A., Thurston, G. D., To, T., Vanker, A., & Wuebbles, D. J. (2019). Air pollution and noncommunicable diseases: A review by the forum of international respiratory societies’ environmental committee, part 2: Air pollution and organ systems. Chest, 155(3), 417–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schultz, P. W. (2014). Strategies for promoting pro-environmental behavior. European Psychologist, 19(2), 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabani Isenaj, Z., Moshammer, H., Berisha, M., & Weitensfelder, L. (2024). Determinants of knowledge, attitudes, perceptions, and behaviors regarding air pollution in schoolchildren in Pristina, Kosovo. Children, 11(1), 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sprague, N. L., & Ekenga, C. C. (2022). The impact of nature-based education on health-related quality of life among low-income youth: Results from an intervention study. Journal of Public Health, 44(2), 394–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sprague, N. L., Okere, U. C., Kaufman, Z. B., & Ekenga, C. C. (2021). Enhancing educational and environmental awareness outcomes through photovoice. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 20, 1832–1842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesfai, M., Nagothu, U. S., Šimek, J., & Fucíkc, P. (2016). Perceptions of secondary school students’ towards environmental services: A case study from Czechia. ResearchGate. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/306107556_Perceptions_of_Secondary_School_Students’_Towards_Environmental_Services_A_Case_Study_from_Czechia (accessed on 24 February 2025).

- VoPham, T., Kim, E. S., Laden, F., & Hart, J. E. (2022). Educational intervention to promote air pollution knowledge and personal exposure mitigation strategies using wearable sensors. In ISEE conference abstracts (vol. 2022). EHP Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wals, A. E., & Jickling, B. (2021). Beyond mainstream environmental education: Towards socioecological transformation. In R. B. Stevenson, M. Brody, J. Dillon, & A. E. J. Wals (Eds.), International handbook of research on environmental education (2nd ed., pp. 101–116). Springer. Available online: https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/edit/10.4324/9780203813331/international-handbook-research-environmental-education-justin-dillon-michael-brody-robert-stevenson-arjen-wals (accessed on 29 April 2024).

- Walsh-Daneshmandi, A., & MacLachlan, M. (2006). Toward effective evaluation of environmental education: Validity of the children’s environmental attitudes and knowledge scale using data from a sample of Irish adolescents. Journal of Environmental Education, 37(2), 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wehrmeyer, W., & McNeil, M. (2000). Activists, pragmatists, technophiles, and tree-huggers? Gender differences in employees’ environmental attitudes. Journal of Business Ethics, 28(3), 211–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. (2017). Air quality management in Bosnia and Herzegovina. World Bank. Available online: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/117281576515111584/pdf/Air-Quality-Management-in-Bosnia-and-Herzegovina.pdf (accessed on 18 July 2024).

- World Health Organization. (2024a). Ambient (outdoor) air quality and health. World Health Organization. Available online: https://www.who.int/es/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ambient-(outdoor)-air-quality-and-health (accessed on 6 August 2024).

- World Health Organization. (2024b). Health consequences of air pollution. World Health Organization. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/25-06-2024-what-are-health-consequences-of-air-pollution-on-populations (accessed on 6 August 2024).

- Zelezny, L. C., Chua, P. P., & Aldrich, C. (2000). Elaborating on gender differences in environmentalism. Journal of Social Issues, 56(3), 443–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables N (%) | Post-Intervention | Follow-Up | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention (n = 1169) | Control (n = 1223) | Intervention (n = 510) | Control (n = 541) | |

| Sex | ||||

| Males | 533 (45.6%) | 582 (47.6%) | 246 (48.2%) | 285 (52.6%) |

| Females | 636 (54.4%) | 641 (52.4%) | 264 (51.8%) | 256 (47.4%) |

| Grade | ||||

| 5th Grade | 80 (6.8%) | 145 (11.8%) | 72 (14.2%) | 117 (21.6%) |

| 6th Grade | 260 (22.3%) | 214 (17.5%) | 159 (31.2%) | 136 (25.3%) |

| 7th Grade | 258 (22.1%) | 287 (23.5%) | 163 (31.9%) | 149 (27.5%) |

| 8th Grade | 275 (23.5%) | 297 (24.3%) | 101 (19.8%) | 37 (6.8%) |

| 9th Grade | 296 (25.3%) | 280 (22.9%) | 15 (2.9) | 102 (18.8%) |

| Father’s education | ||||

| No school | 6 (0.5%) | 14 (1.2%) | 4 (0.8%) | 4 (0.7%) |

| Primary school | 133 (11.4%) | 112 (9.2%) | 66 (12.9%) | 69 (12.8%) |

| Secondary school | 349 (29.8%) | 388 (31.7%) | 120 (23.5%) | 187 (34.6%) |

| University | 681 (58.3%) | 709 (57.9%) | 320 (62.8%) | 281 (51.9%) |

| Mothers’ education | ||||

| No school | 45 (3.8%) | 24 (1.9%) | 19 (3.7%) | 13 (2.4%) |

| Primary school | 151 (12.9%) | 85 (6.9%) | 66 (12.9%) | 42 (7.8%) |

| Secondary school | 321 (27.5%) | 389 (31.9%) | 115 (22.6%) | 200 (36.9%) |

| University | 652 (55.8%) | 725 (59.3%) | 310 (60.8%) | 286 (52.9%) |

| Health Status | ||||

| Poor | 28 (2.4%) | 18 (1.5%) | 13 (2.6%) | 9 (1.7%) |

| Fair | 164 (14.1%) | 138 (11.2%) | 84 (16.5%) | 60 (11.1%) |

| Good | 475(40.6%) | 491 (40.2%) | 204 (40.0%) | 226 (41.7%) |

| Very Good | 502 (42.9%) | 576 (47.1%) | 209 (40.9%) | 246 (45.5%) |

| Group | Number | Mean (Mean) | 95% Confidence Interval | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention | 510 | 5.41 (0–8) | 5.29; 5.54 | |

| Controls | 541 | 3.03 (0–7) | 2.91; 3.15 | |

| Both | 1051 | 4.19 (0–8) | 5.57; 5.89 | |

| Difference | 2.38 | 2.21; 2.55 | <0.001 |

| Group | Number | Mean | 95% Confidence Interval | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention | 510 | 8.18 (0–14) | 7.93; 8.43 | |

| Controls | 541 | 7.72 (0–13) | 7.52; 7.91 | |

| Both | 1051 | 7.94 (0–14) | 7.78; 8.10 | |

| Difference | 0.46 | 0.15; 0.78 | 0.0038 |

| Group | Number | Mean | 95% Confidence Interval | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention | 510 | 22.69 (7–33) | 22:32; 23:06 | |

| Controls | 541 | 21.37 (8–33) | 21.03; 21.72 | |

| Both | 1051 | 22.01 (7–33) | 21.76; 22.27 | |

| Difference | 1.32 | 0.81; 1.82 | <0.001 |

| Group | Number | Mean | 95% Confidence Interval | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention | 510 | 4.65 (0–9) | 4.48, 4.81 | |

| Controls | 541 | 5.33 (0–9) | 5.16, 5.50 | |

| Both | 1051 | 5.00 (0–9) | 4.88, 5.12 | |

| Difference | −0.68 | −0.92; −0.45 | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the University Association of Education and Psychology. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Isenaj, Z.S.; Moshammer, H.; Berisha, M.; Weitensfelder, L. Effect of an Educational Intervention on Pupil’s Knowledge, Attitudes, Perceptions, and Behavior on Air Pollution in Public Schools in Pristina. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2025, 15, 69. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15050069

Isenaj ZS, Moshammer H, Berisha M, Weitensfelder L. Effect of an Educational Intervention on Pupil’s Knowledge, Attitudes, Perceptions, and Behavior on Air Pollution in Public Schools in Pristina. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education. 2025; 15(5):69. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15050069

Chicago/Turabian StyleIsenaj, Zana Shabani, Hanns Moshammer, Merita Berisha, and Lisbeth Weitensfelder. 2025. "Effect of an Educational Intervention on Pupil’s Knowledge, Attitudes, Perceptions, and Behavior on Air Pollution in Public Schools in Pristina" European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education 15, no. 5: 69. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15050069

APA StyleIsenaj, Z. S., Moshammer, H., Berisha, M., & Weitensfelder, L. (2025). Effect of an Educational Intervention on Pupil’s Knowledge, Attitudes, Perceptions, and Behavior on Air Pollution in Public Schools in Pristina. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 15(5), 69. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15050069