Impact of Family Environment in Rural China on Loneliness, Depression, and Internet Addiction Among Children and Adolescents

Abstract

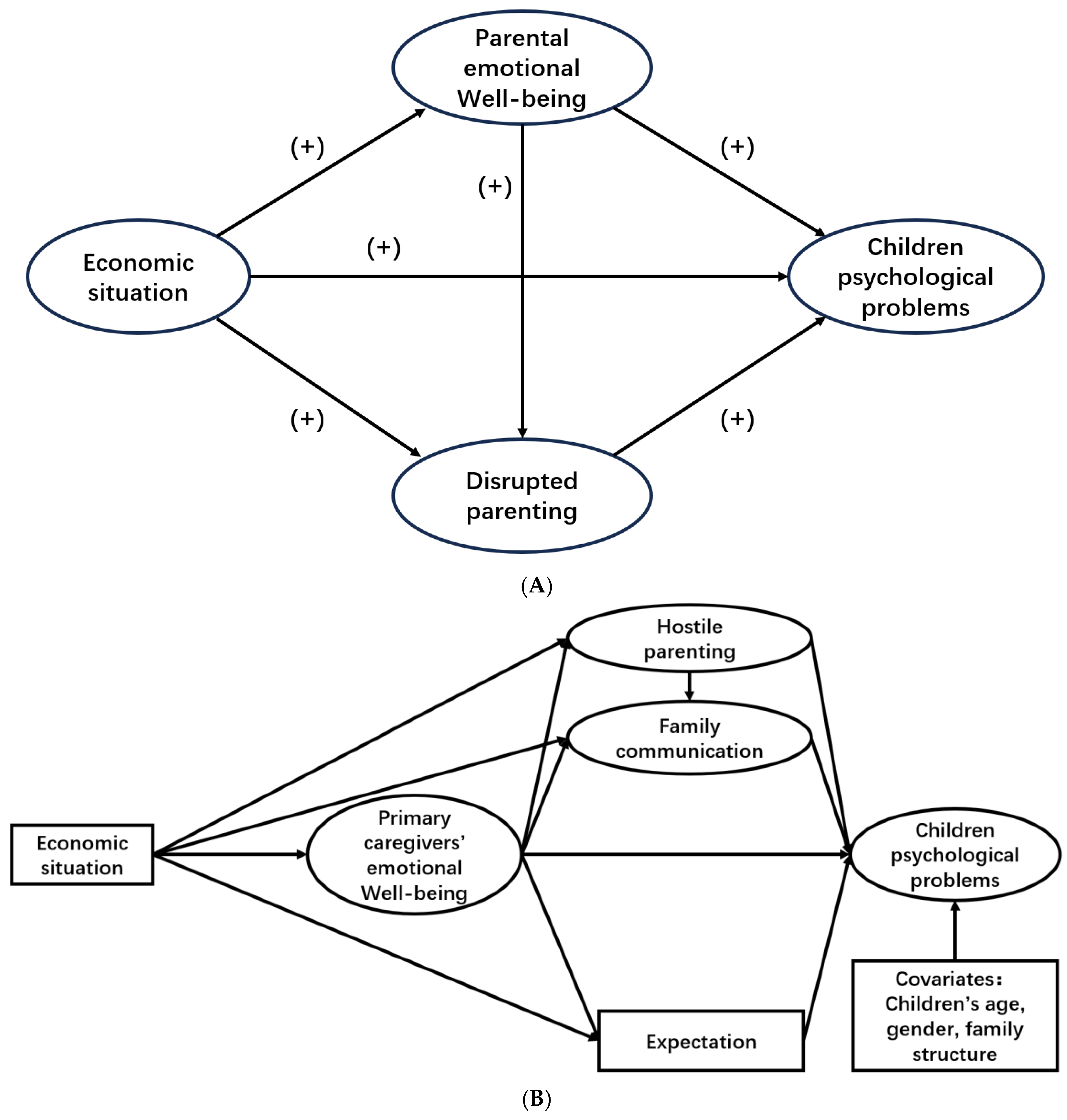

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

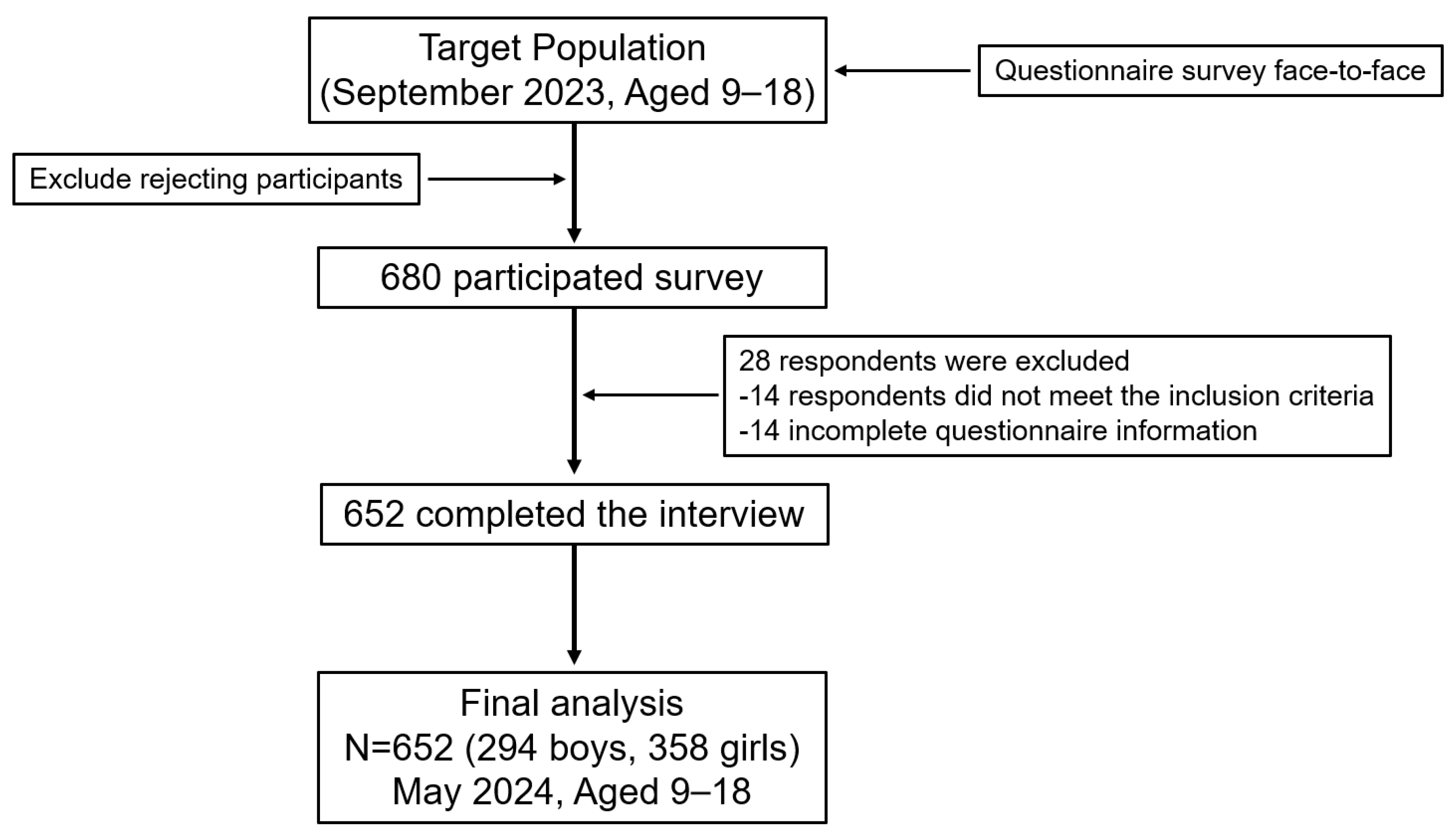

2.1. Research Design and Study Participants

Sample

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Loneliness Among Children and Adolescents

2.2.2. Depression Among Children and Adolescents

2.2.3. Internet Addiction Among Children and Adolescents

2.2.4. Family Environment: The Family Environment Was Comprehensively Assessed Through Five Sub-Dimensions (X. Ding et al., 2024; Yang & Zhao, 2020; Young & Hannum, 2018)

Economic Situation

Parenting Styles

Family Communication

Caregivers’ Emotional Well-Being

Caregivers’ Expectations for Children

2.3. Covariates

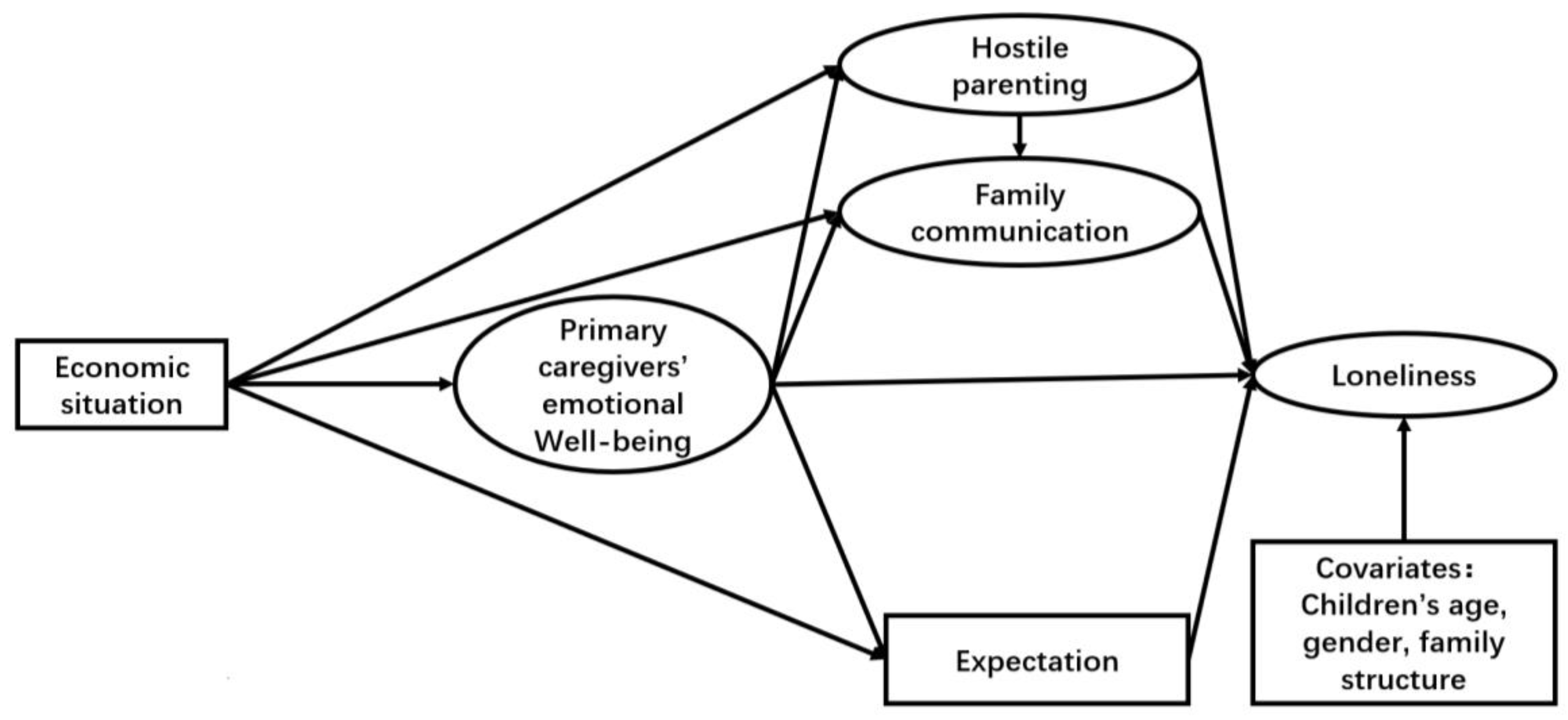

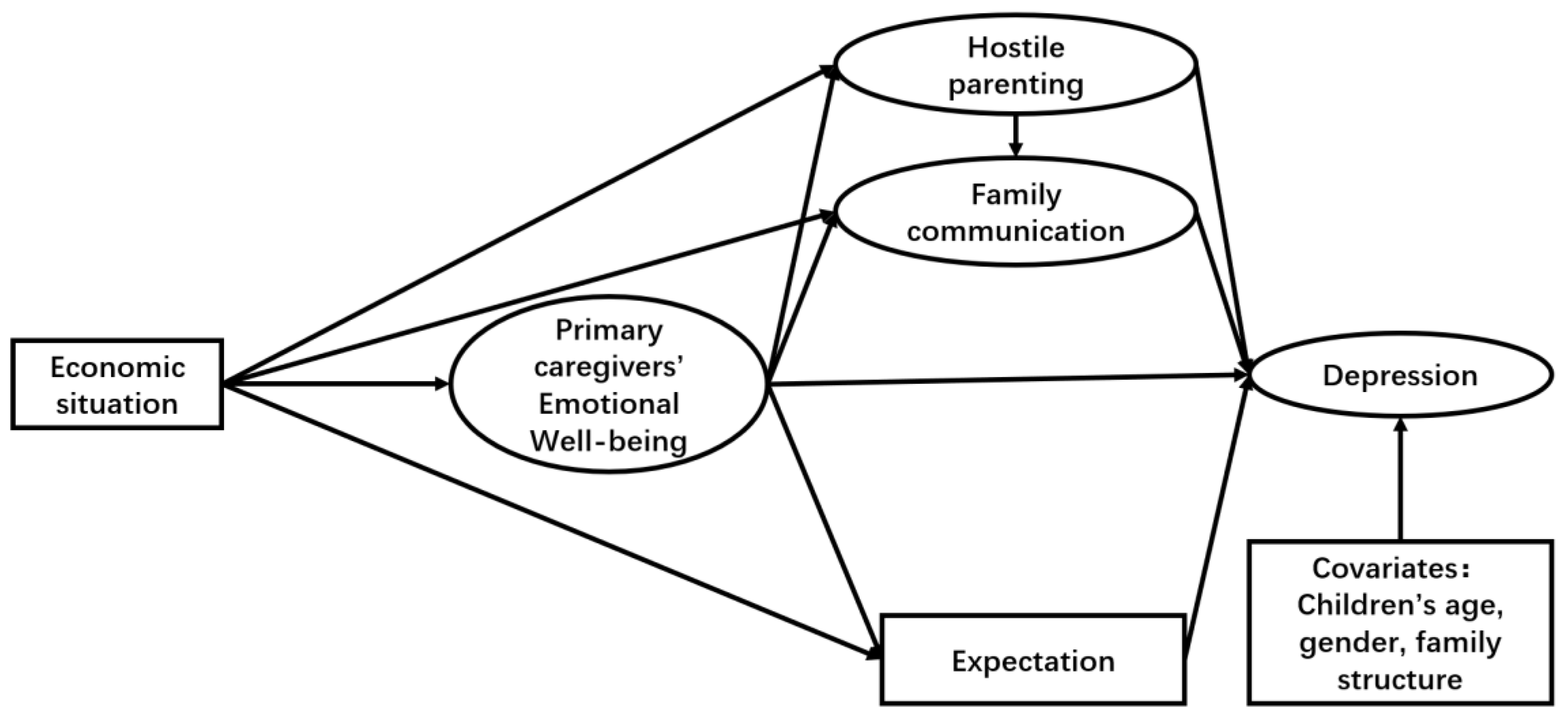

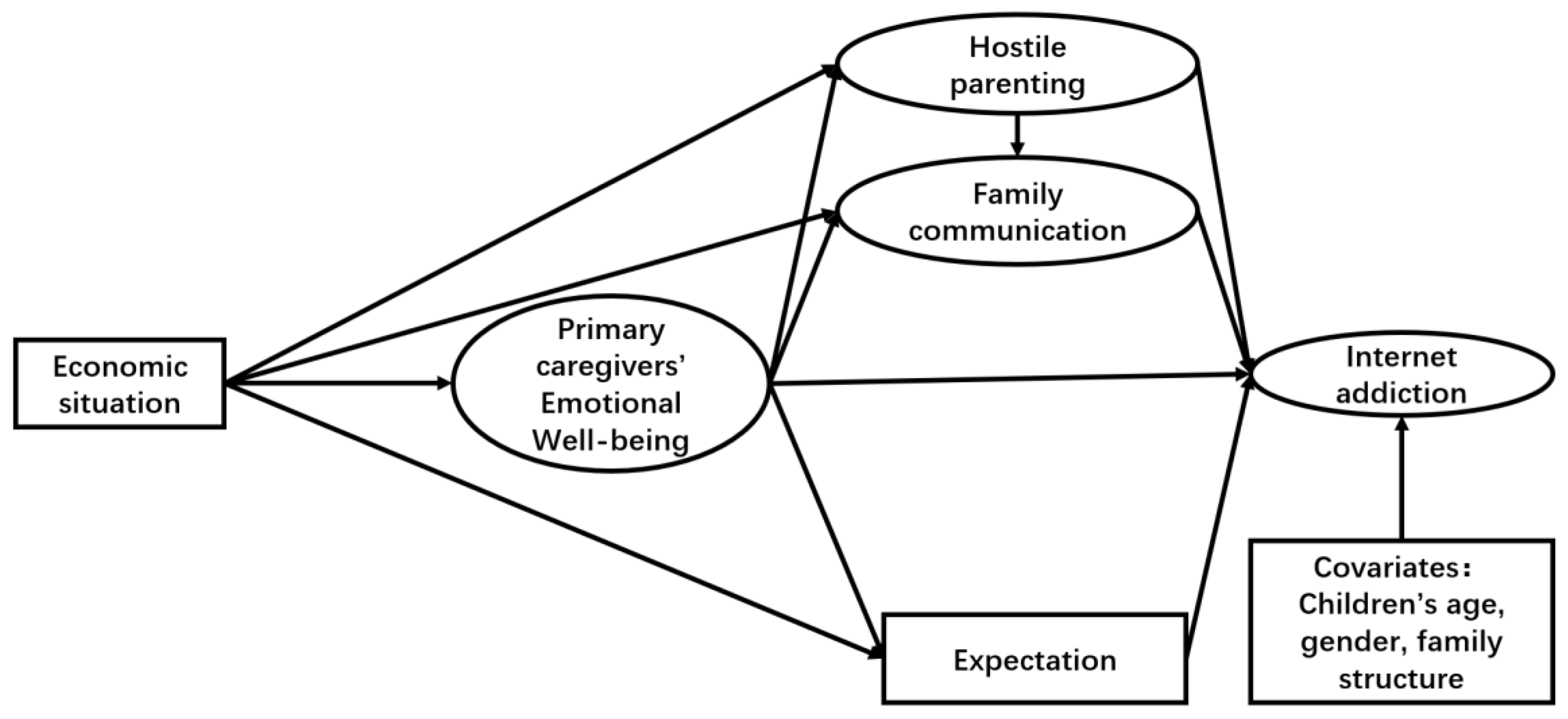

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic Characteristics of the Participants

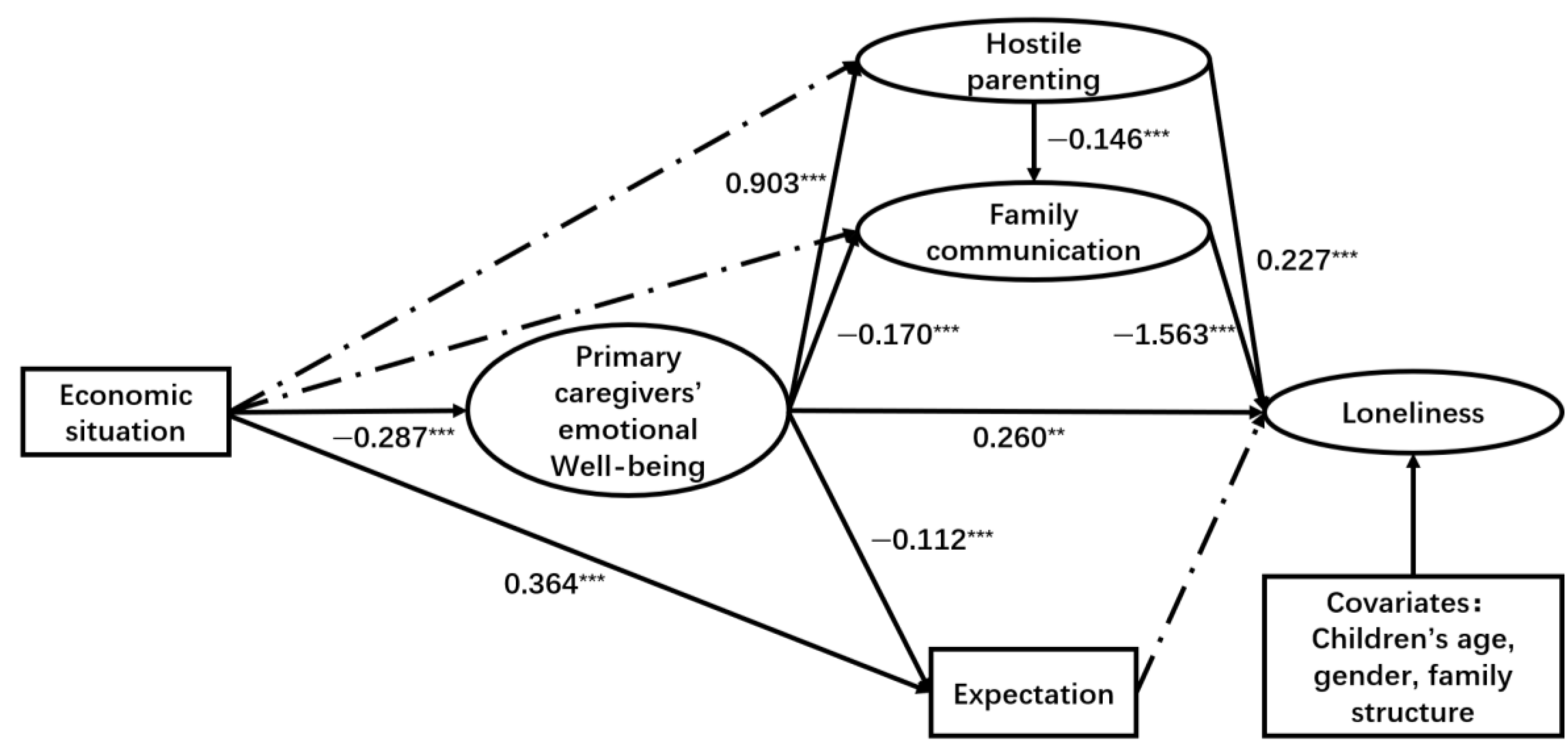

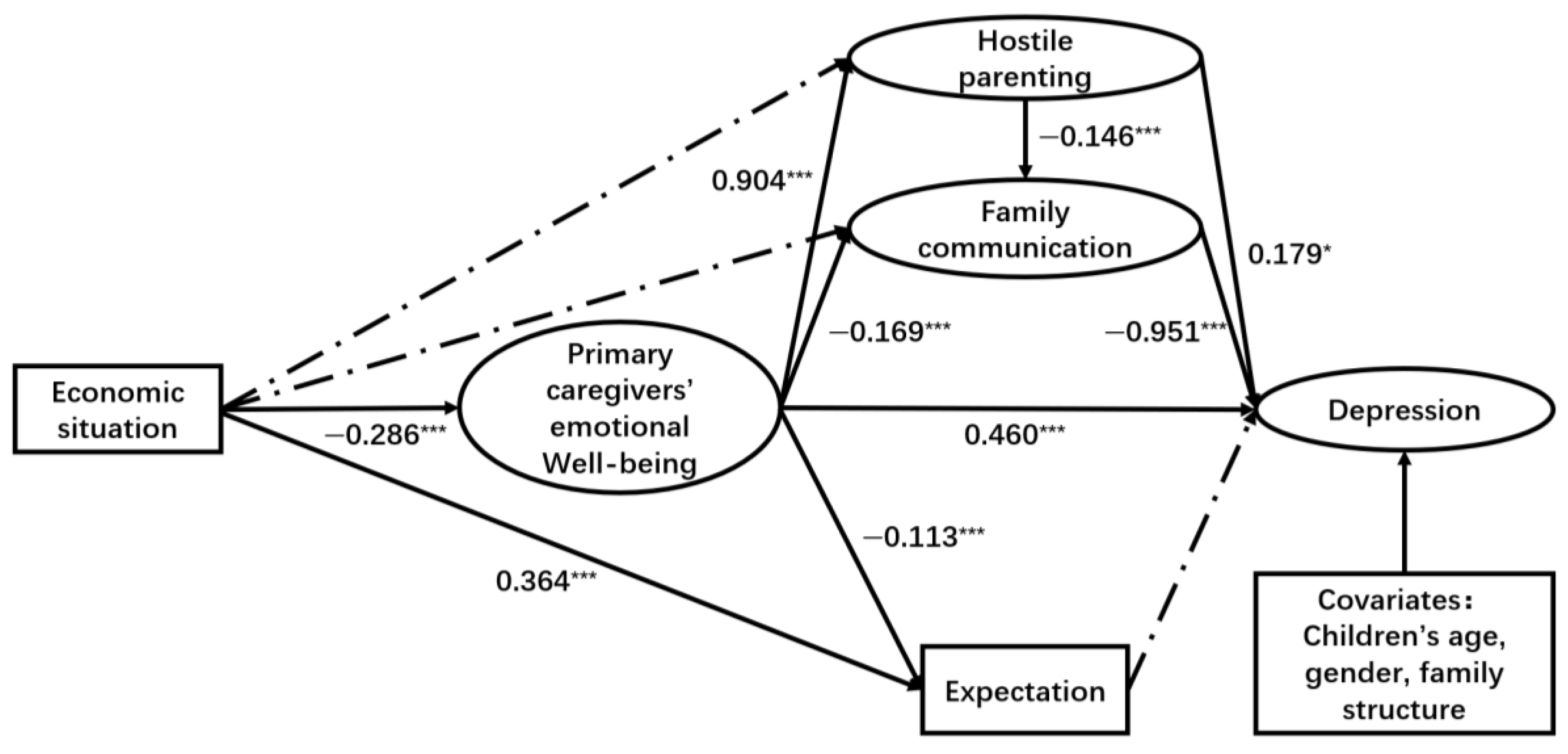

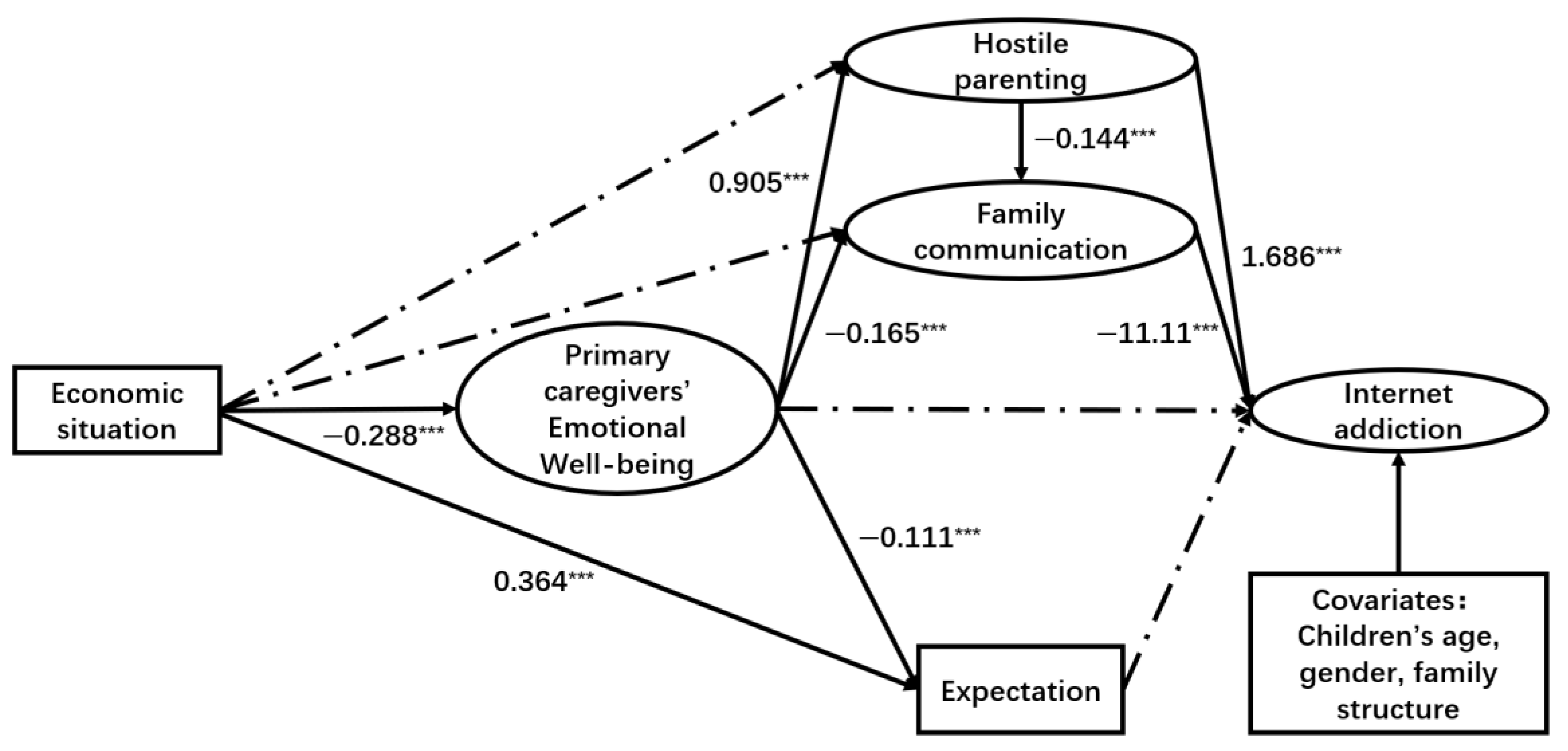

3.2. Associations of Family Environment with Loneliness, Depression, and Internet Addiction in Children and Adolescents

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Loneliness | 1 | ||||||||

| 2. Depression | 0.897 ** | 1 | |||||||

| 3. Internet Addiction | 0.590 ** | 0.531 ** | 1 | ||||||

| 4. Economic Condition | −0.273 ** | −0.255 ** | −0.232 ** | 1 | |||||

| 5. Family Communication | −0.768 ** | −0.721 ** | −0.661 ** | 0.328 ** | 1 | ||||

| 6. Expectation | −0.269 ** | −0.265 ** | −0.175 ** | 0.525 ** | 0.262 ** | 1 | |||

| 7. Primary caregivers’ emotional well-being | 0.802 ** | 0.790 ** | 0.648 ** | −0.370 ** | −0.787 ** | −0.285 ** | 1 | ||

| 8. Warm Parenting | −0.773 ** | −0.761 ** | −0.651 ** | 0.301 ** | 0.776 ** | 0.270 ** | −0.829 ** | 1 | |

| 9. Hostile Parenting | 0.786 ** | 0.754 ** | 0.669 ** | −0.311 ** | −0.765 ** | −0.266 ** | 0.837 ** | −0.854 ** | 1 |

References

- Allen, J., Balfour, R., Bell, R., & Marmot, M. (2014). Social determinants of mental health. International Review of Psychiatry, 26(4), 392–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barajas-Gonzalez, R. G., & Brooks-Gunn, J. (2014). Income, neighborhood stressors, and harsh parenting: Test of moderation by ethnicity, age, and gender. Journal of Family Psychology, 28(6), 855–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, A. C., Brewer, K. C., & Rankin, K. M. (2012). The association of child mental health conditions and parent mental health status among U.S. Children, 2007. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 16(6), 1266–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, N., Pei, Y., Lin, X., Wang, J., Bu, X., & Liu, K. (2019). Mental health status compared among rural-to-urban migrant, urban and rural school-age children in Guangdong Province, China. BMC Psychiatry, 19(1), 383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X., Wang, L., Li, D., & Liu, J. (2014). Loneliness in Chinese children across contexts. Developmental Psychology, 50(10), 2324–2333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- China Foundation Development Forum Parallel Forum. (2022). Report on the investigation of rural children’s mental health. Available online: https://www.csaf.org.cn/content/1438 (accessed on 10 January 2022).

- Chinese Communist Youth League. (2022). National research report on internet usage among minors. Available online: https://qnzz.youth.cn/qckc/202211/t20221130_14166885.htm (accessed on 30 November 2022).

- Conger, R. D., Ge, X., Elder, G. H., Lorenz, F. O., & Simons, R. L. (1994). Economic stress, coercive family process, and developmental problems of adolescents. Child Development, 65(2), 541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, M., & Hong, P. (2021). COVID-19 and mental health of young adult children in China: Economic impact, family dynamics, and resilience. Family Relations, 70(5), 1358–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Figueiredo, C. S., Sandre, P. C., Portugal, L. C. L., Mázala-de-Oliveira, T., Da Silva Chagas, L., Raony, Í., Ferreira, E. S., Giestal-de-Araujo, E., Dos Santos, A. A., & Bomfim, P. O.-S. (2021). COVID-19 pandemic impact on children and adolescents’ mental health: Biological, environmental, and social factors. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry, 106, 110171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, X., Ji, Y., Dong, Y., Li, Z., & Zhang, Y. (2024). The impact of family factors and communication on recreational sedentary screen time among primary school-aged children: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health, 24(1), 1733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y., Chen, L., & Zhang, Z. (2022). The relationship between social participation and depressive symptoms among Chinese middle-aged and older adults: A cross-lagged panel analysis. Frontiers in Public Health, 10, 996606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y., & Chen, Q. (2012). Family functioning as a mediator between neighborhood conditions and children’s health: Evidence from a national survey in the United States. Social Science & Medicine, 74(12), 1939–1947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fellmeth, G., Rose-Clarke, K., Zhao, C., Busert, L. K., Zheng, Y., Massazza, A., Sonmez, H., Eder, B., Blewitt, A., Lertgrai, W., Orcutt, M., Ricci, K., Mohamed-Ahmed, O., Burns, R., Knipe, D., Hargreaves, S., Hesketh, T., Opondo, C., & Devakumar, D. (2018). Health impacts of parental migration on left-behind children and adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet, 392(10164), 2567–2582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glynn, L. M., Davis, E. P., Luby, J. L., Baram, T. Z., & Sandman, C. A. (2021). A predictable home environment may protect child mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. Neurobiology of Stress, 14, 100291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gou, Y., Wu, N., Xia, J., Liu, Y., Yang, H., Wang, H., Yan, T., & Luo, D. (2022). Province-and individual-level influential factors of depression: Multilevel cross-provinces comparison in China. Frontiers in Public Health, 10, 893280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hohashi, N., & Honda, J. (2011). Development of the concentric sphere family environment model and companion tools for culturally congruent family assessment. Journal of Transcultural Nursing, 22(4), 350–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kenney, M. K., & Chanlongbutra, A. (2020). Prevalence of parent reported health conditions among 0-to 17-year-olds in rural United States: National survey of children’s health, 2016–2017. The Journal of Rural Health, 36(3), 394–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J., Kubik, M. Y., Fulkerson, J. A., Kohli, N., & Garwick, A. E. (2020). The identification of family social environment typologies using latent class analysis: Implications for future family-focused research. Journal of Family Nursing, 26(1), 26–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S. L., Pearce, E., Ajnakina, O., Johnson, S., Lewis, G., Mann, F., Pitman, A., Solmi, F., Sommerlad, A., Steptoe, A., Tymoszuk, U., & Lewis, G. (2021). The association between loneliness and depressive symptoms among adults aged 50 years and older: A 12-year population-based cohort study. The Lancet Psychiatry, 8(1), 48–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leng, X. (2022). Digital revolution and rural family income: Evidence from China. Journal of Rural Studies, 94, 336–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M., Xue, H., Wang, W., & Wang, Y. (2017). Parental Expectations and Child Screen and Academic Sedentary Behaviors in China. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 52(5), 680–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linardon, J., Anderson, C., & McClure, Z. (2023). Body appreciation predicts better mental health and wellbeing. A short-term prospective study. Body Image, 45, 20–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, D., Zhang, Z., & Fu, M. (2008). Factor structure of the family environment scale among adolescents in Chinese. Chinese Journal of Behavioral Medical Science, 17(3), 277–279. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, L.-J., & Guo, Q. (2007). Loneliness and health-related quality of life for the empty nest elderly in the rural area of a mountainous county in China. Quality of Life Research, 16(8), 1275–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S., Fang, Y., Su, Z., Cai, J., & Chen, Z. (2023). Factor structure and measurement invariance of the 8-item CES-D: A national longitudinal sample of Chinese adolescents. BMC Psychiatry, 23(1), 868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, T., Jia, Y., Yang, Y., Yan, J., & Mu, W. (2024). Validation of the revised Chen internet addition scale for Chinese older adults. Research on Social Work Practice, 34(8), 922–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mak, K.-K., Lai, C.-M., Ko, C.-H., Chou, C., Kim, D.-I., Watanabe, H., & Ho, R. C. M. (2014). Psychometric properties of the revised chen internet addiction scale (CIAS-R) in Chinese adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 42(7), 1237–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Z., & Zhao, X. (2012). The effects of social connections on self-rated physical and mental health among internal migrant and local adolescents in Shanghai, China. BMC Public Health, 12(1), 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meherali, S., Punjani, N., Louie-Poon, S., Abdul Rahim, K., Das, J., Salam, R., & Lassi, Z. (2021). Mental health of children and adolescents amidst COVID 19 and past pandemics: A rapid systematic review. SOCIAL SCIENCES. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mistry, R. S., Vandewater, E. A., Huston, A. C., & McLoyd, V. C. (2002). Economic well-being and children’s social adjustment: The role of family process in an ethnically diverse low-income sample. Child Development, 73(3), 935–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Bureau of Statistics of China. (2023). China’s child population situation in 2020 facts and figures. Available online: https://www.unicef.cn/media/24496/file (accessed on 19 April 2023).

- National Bureau of Statistics of China. (2024). 2023 migrant workers monitoring survey report. Available online: https://www.gov.cn/lianbo/bumen/202405/content_6948813.htm (accessed on 1 May 2024).

- Paterson, G., & Sanson, A. (1999). The association of behavioural adjustment to temperament, parenting and family characteristics among 5-year-old children. Social Development, 8(3), 293–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- People’s Daily Overseas Edition. (2023, March 29). China’s permanent population urbanization rate exceeds 65%, and urbanization enters the “second half”. Available online: https://news.cctv.com/2023/03/29/ARTI0oMQJO0p8MNxpyBMCn3O230329.shtml (accessed on 29 March 2023).

- Prime, H., Wade, M., & Browne, D. T. (2020). Risk and resilience in family well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic. American Psychologist, 75(5), 631–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russell, B. S., Hutchison, M., Tambling, R., Tomkunas, A. J., & Horton, A. L. (2020). Initial challenges of caregiving during COVID-19: Caregiver burden, mental health, and the parent–child relationship. Child Psychiatry & Human Development, 51(5), 671–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, D., Chen, F., & Ouyang, X. (2024). The impact of changes in rural family structure on agricultural productivity and efficiency: Evidence from rice farmers in China. Sustainability, 16(10), 3892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Southern Metropolis Daily. (2022). Internet penetration rate among rural minors exceeds that in urban areas, and the youth model needs to be improved. Available online: https://m.mp.oeeee.com/a/BAAFRD000020221201745290.html (accessed on 1 December 2022).

- Suizzo, M., & Cheng, C. (2007). Taiwanese and American mothers’ goals and values for their children’s futures. International Journal of Psychology, 42(5), 307–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, R., Luo, D., Li, B., Wang, J., & Li, M. (2023). The role of family support in diabetes self-management among rural adult patients. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 32(19–20), 7238–7246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torche, F., Fletcher, J., & Brand, J. E. (2024). Disparate effects of disruptive events on children. RSF: The Russell Sage Foundation Journal of the Social Sciences, 10(1), 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C., Li, S., Wang, Y., Li, M., & Tao, W. (2024). Growth mindset and well-being in social interactions: Countering individual loneliness. Frontiers in Public Health, 12, 1368491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., Zhou, K., Wang, Y., Zhang, J., Xie, Y., Wang, X., Yang, W., Zhang, X., Yang, J., & Wang, F. (2024). Examining the association of family environment and children emotional/behavioral difficulties in the relationship between parental anxiety and internet addiction in youth. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 15, 1341556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, H.-S., & Chen, J.-K. (2014). The relationships between family financial stress, mental health problems, child rearing practice, and school involvement among Taiwanese parents with school-aged children. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 23(7), 1145–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D., Liu, M., Li, D., & Yin, H. (2024). The longitudinal relationship between loneliness and both social anxiety and mobile phone addiction among rural left-behind children: A cross-lagged panel analysis. Journal of Adolescence, 96(5), 969–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y., Becerik-Gerber, B., Lucas, G., & Roll, S. C. (2021). Impacts of working from home during COVID-19 pandemic on physical and mental well-being of office workstation users. Journal of Occupational & Environmental Medicine, 63(3), 181–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, S., Wu, D., & Liang, L. (2022). Family environment profile in China and its relation to family structure and young children’s social competence. Early Education and Development, 33(3), 469–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xinhua News Agency. (2022). The number of Internet users in my country has reached 1.032 billion. Available online: https://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2022-02/25/content_5675643.htm (accessed on 25 February 2022).

- Xu, H. (2019). Physical and mental health of Chinese grandparents caring for grandchildren and great-grandparents. Social Science & Medicine, 229, 106–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J., & Wang, Y. (2025). The goldilocks effect of parental educational aspirations on academic achievement: The benefit of expectations and harm of the gap. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 40(1), 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J., & Zhao, X. (2020). Parenting styles and children’s academic performance: Evidence from middle schools in China. Children and Youth Services Review, 113, 105017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, J., & Lu, P. (2011). Differentiated childhoods: Impacts of rural labor migration on left-behind children in China. Journal of Peasant Studies, 38(2), 355–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, N. A. E., & Hannum, E. C. (2018). Childhood inequality in China: Evidence from recent survey data (2012–2014). The China Quarterly, 236, 1063–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, X., Lei, T., Su, Y., Li, X., & Zhu, L. (2024). Longitudinal associations between intergroup contact and intergroup trust among adolescents in ethnic regions of China. Scientific Reports, 14(1), 15942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J. (2018). Comparative study of life quality between migrant children and local students in small and medium-sized cities in China. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 35(6), 649–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L. (2024). Parent-child expectation discrepancy and adolescent mental health: Evidence from “China Education Panel Survey”. Child Indicators Research, 17(2), 705–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C., Wang, F., Zhou, X., Jiang, M., & Hesketh, T. (2018). Impact of parental migration on psychosocial well-being of children left behind: A qualitative study in rural China. International Journal for Equity in Health, 17(1), 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F., & Yu, G. (2016). Parental migration and rural left-behind children’s mental health in China: A meta-analysis based on mental health test. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 25(12), 3462–3472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M., Zhu, Z., Kong, C., & Zhao, C. (2021). Caregiver burden and parenting stress among left-behind elderly individuals in rural China: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health, 21(1), 846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Q., Guo, S., & Lu, H. J. (2021). Well-being and health of children in rural China: The roles of parental absence, economic status, and neighborhood environment. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 16(5), 2023–2037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | n (%) | Mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|

| Children and adolescents’ sociodemographic characteristics | ||

| Gender | ||

| Male | 294 (45.1) | |

| Female | 358 (54.9) | |

| Age (years) | 13.06 (2.16) | |

| Children | 297 (45.6%) | |

| Adolescent | 355 (54.4%) | |

| Education level | ||

| Primary school | 280 (42.9) | |

| Junior high school | 240 (36.9) | |

| High school and above | 132 (20.2) | |

| Children and adolescents’ psychological and behavioral characteristics | ||

| R-UCLA score (Loneliness) | 2.60 (2.84) | |

| CES-D score (Depression) | 6.42 (6.68) | |

| CIAS-R score (Internet Addiction) | 50.35 (21.55) | |

| Family environment | ||

| Primary caregiver | ||

| Both parents | 209 (32.1) | |

| One parent | 184 (28.2) | |

| Grandparents | 259 (39.7) | |

| Education level of the Primary caregiver | ||

| Primary school or below | 81 (12.4) | |

| Junior high school | 340 (52.2) | |

| High school | 198 (30.4) | |

| University and above | 33 (5.0) | |

| Economic situation (per capita) | ||

| <1000 CNY a | 21 (3.2) | |

| 1000–2000 CNY | 148 (22.7) | |

| 2000–3000 CNY | 266 (40.8) | |

| 3000–5000 CNY | 150 (23) | |

| >5000 CNY | 67 (10.3) | |

| R-UCLA and CES-D score (Parents’ emotional well-being) | 32.34 (8.08) | |

| Caregivers’ expectation for children | ||

| High | 182 (27.9) | |

| Middle | 289 (44.3) | |

| Low | 181 (27.8) |

| Model | χ2 | d.f. | χ2/d.f. | CFI | TLI | RMSEA | SRMR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Loneliness a | 786.351 | 340 | 2.31 | 0.970 | 0.967 | 0.045 | 0.031 |

| Loneliness b | 391.023 | 147 | 2.66 | 0.981 | 0.978 | 0.050 | 0.027 |

| Depression a | 943.302 | 454 | 2.08 | 0.973 | 0.970 | 0.041 | 0.029 |

| Depression b | 511.593 | 226 | 2.26 | 0.982 | 0.980 | 0.044 | 0.026 |

| Internet addiction a | 817.434 | 367 | 2.23 | 0.972 | 0.969 | 0.043 | 0.031 |

| Internet addiction b | 1113.05 | 165 | 6.75 | 0.931 | 0.921 | 0.094 | 0.302 |

| Pathways | β | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||

| Loneliness | |||

| 0.004 | −0.006 | 0.011 |

| −0.059 | −0.089 | −0.030 |

| −0.013 | −0.035 | 0.009 |

| −0.006 | −0.025 | 0.013 |

| 0.002 | −0.006 | 0.011 |

| −0.075 | −0.121 | −0.028 |

| −0.059 | −0.100 | −0.018 |

| −0.001 | −0.002 | 0.001 |

| −0.076 | −0.113 | −0.040 |

| Pathways | β | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||

| Depression | |||

| 0.001 | −0.004 | 0.007 |

| −0.036 | −0.060 | −0.012 |

| −0.010 | −0.025 | 0.005 |

| −0.009 | −0.029 | 0.010 |

| 0.002 | −0.005 | 0.009 |

| −0.132 | −0.184 | −0.080 |

| −0.046 | −0.087 | −0.005 |

| −0.001 | −0.003 | 0.001 |

| −0.046 | −0.076 | −0.016 |

| Pathways | β | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||

| Internet addiction | |||

| 0.015 | −0.045 | 0.076 |

| −0.418 | −0.630 | −0.206 |

| −0.137 | −0.297 | 0.022 |

| 0.097 | −0.045 | 0.238 |

| 0.016 | −0.048 | 0.080 |

| 0.110 | −0.224 | 0.443 |

| −0.439 | −0.747 | −0.132 |

| 0.009 | −0.005 | 0.022 |

| −0.529 | −0.795 | −0.262 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the University Association of Education and Psychology. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhou, Y.; Zheng, M.; He, Y.; Zhang, J.; Guo, T.; Wang, Q.; Chen, W. Impact of Family Environment in Rural China on Loneliness, Depression, and Internet Addiction Among Children and Adolescents. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2025, 15, 68. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15050068

Zhou Y, Zheng M, He Y, Zhang J, Guo T, Wang Q, Chen W. Impact of Family Environment in Rural China on Loneliness, Depression, and Internet Addiction Among Children and Adolescents. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education. 2025; 15(5):68. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15050068

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhou, Yixiang, Meng Zheng, Yujie He, Jianghui Zhang, Tingting Guo, Qing Wang, and Wen Chen. 2025. "Impact of Family Environment in Rural China on Loneliness, Depression, and Internet Addiction Among Children and Adolescents" European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education 15, no. 5: 68. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15050068

APA StyleZhou, Y., Zheng, M., He, Y., Zhang, J., Guo, T., Wang, Q., & Chen, W. (2025). Impact of Family Environment in Rural China on Loneliness, Depression, and Internet Addiction Among Children and Adolescents. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 15(5), 68. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15050068