The Influence of Loneliness, Social Support and Income on Mental Well-Being

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Participants’ Information

3.2. Mental Well-Being

3.3. Linear Regression

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MOS-SSS | Medical Outcomes Study Social Support Survey |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| UCLA | University of California, Los Angeles |

| WEMWBS | Warwick–Edinburgh Mental Well-Being Scale |

References

- Barreto, M., Victor, C., Hammond, C., Eccles, A., Richins, M. T., & Qualter, P. (2021). Loneliness around the world: Age, gender, and cultural differences in loneliness. Personality and Individual Differences, 169, 110066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruss, K. V., Seth, P., & Zhao, G. (2024). Loneliness, lack of social and emotional support, and mental health issues—United States, 2022. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 73, 539–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cacioppo, J. T., & Hawkley, L. C. (2009). Perceived social isolation and cognition. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 13(10), 447–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cacioppo, J. T., Hawkley, L. C., Crawford, L. E., Ernst, J. M., Burleson, M. H., Kowalewski, R. B., Malarkey, W. B., Van Cauter, E., & Berntson, G. G. (2002). Loneliness and health: Potential mechanisms. Psychosomatic Medicine, 64(3), 407–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cacioppo, J. T., Hawkley, L. C., & Thisted, R. A. (2010). Perceived social isolation makes me sad: 5-year cross-lagged analyses of loneliness and depressive symptomatology in the Chicago Health, Aging, and Social Relations Study. Psychology and Aging, 25(2), 453–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacioppo, J. T., & Patrick, W. (2008). Loneliness: Human nature and the need for social connection. W W Norton & Co. [Google Scholar]

- Castellví, P., Forero, C. G., Codony, M., Vilagut, G., Brugulat, P., Medina, A., Gabilondo, A., Mompart, A., Colom, J., Tresserras, R., Ferrer, M., Stewart-Brown, S., & Alonso, J. (2014). The Spanish version of the Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-Being Scale (WEMWBS) is valid for use in the general population. Quality of Life Research, 23(3), 857–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen-Xia, X. J., Betancor, V., Rodríguez-Gómez, L., & Rodríguez-Pérez, A. (2023). Cultural variations in perceptions and reactions to social norm transgressions: A comparative study. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1243955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, P. J., Marshall, V. W., Ryff, C. D., & Rosenthal, C. J. (2000). Well being in Canadian seniors: Findings from the Canadian study of health and aging. Canadian Journal on Aging, 19(2), 139–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S., & Wills, T. A. (1985). Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin, 98(2), 310–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, R. M., Knoll, M. A., & Kyranides, M. N. (2024). A moderated mediation analysis on the influence of social support and cognitive flexibility in predicting mental wellbeing in elite sport. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 70, 102560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E., Oishi, S., & Ryan, K. L. (2013). Universals and cultural differences in the causes and structure of happiness: A multilevel review. In Mental well-being: International contributions to the study of positive mental health (pp. 153–176). Springer Science + Business Media. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donovan, N. J., & Blazer, D. (2020). Social isolation and loneliness in older adults: Review and commentary of a national academies report. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 28(12), 1233–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fazia, T., Bubbico, F., Salvato, G., Berzuini, G., Bruno, S., Bottini, G., & Bernardinelli, L. (2020). Boosting psychological well-being through a social mindfulness-based intervention in the general population. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(22), 8404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-Ballesteros, R. (2002). Social support and quality of life among older people in Spain. Journal of Social Issues, 58(4), 645–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forero, C. G., Adroher, N. D., Stewart-Brown, S., Castellví, P., Codony, M., Vilagut, G., Mompart, A., Tresseres, R., Colom, J., Castro, J. I., & Alonso, J. (2014). Differential item and test functioning methodology indicated that item response bias was not a substantial cause of country differences in mental well-being. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 67(12), 1364–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gable, S. L., & Bedrov, A. (2022). Social isolation and social support in good times and bad times. Current Opinion in Psychology, 44, 89–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrett, J. K., Rowney, F. M., White, M. P., Lovell, R., Fry, R. J., Akbari, A., Geary, R., Lyons, R. A., Mizen, A., Nieuwenhuijsen, M., Parker, C., Song, J., Stratton, G., Thompson, D. A., Watkins, A., White, J., Williams, S. A., Rodgers, S. E., & Wheeler, B. W. (2023). Visiting nature is associated with lower socioeconomic inequalities in well-being in Wales. Scientific Reports, 13(1), 9684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautam, S., Jain, A., Chaudhary, J., Gautam, M., Gaur, M., & Grover, S. (2024). Concept of mental health and mental well-being, it’s determinants and coping strategies. Indian Journal of Psychiatry, 66(Suppl. S2), S231–S244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginja, S., Coad, J., Bailey, E., Kendall, S., Goodenough, T., Nightingale, S., Smiddy, J., Day, C., Deave, T., & Lingam, R. (2018). Associations between social support, mental wellbeing, self-efficacy and technology use in first-time antenatal women: Data from the BaBBLeS cohort study. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 18(1), 441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goñi-Balentziaga, O., & Azkona, G. (2023). Perceived professional quality of life and mental well-being among animal facility personnel in Spain. Laboratory Animals, 58(1), 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, C., Higuera, L., & Lora, E. (2011). Which health conditions cause the most unhappiness? Health Economics, 20(12), 1431–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossmann, I., Karasawa, M., Kan, C., & Kitayama, S. (2014). A cultural perspective on emotional experiences across the life span. Emotion, 14(4), 679–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hawkley, L. C., Hughes, M. E., Waite, L. J., Masi, C. M., Thisted, R. A., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2008). From social structural factors to perceptions of relationship quality and loneliness: The Chicago health, aging, and social relations study. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 63(6), S375–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hawkley, L. C., Thisted, R. A., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2009). Loneliness predicts reduced physical activity: Cross-sectional & longitudinal analyses. Health Psychology, 28(3), 354–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hombrados-Mendieta, I., Millán-Franco, M., Gómez-Jacinto, L., Gonzalez-Castro, F., Martos-Méndez, M. J., & García-Cid, A. (2019). Positive influences of social support on sense of community, life satisfaction and the health of immigrants in Spain. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 2555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutten, E., Jongen, E. M. M., Vos, A. E. C. C., van den Hout, A. J. H. C., & van Lankveld, J. J. D. M. (2021). Loneliness and mental health: The mediating effect of perceived social support. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(22), 11963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- INE. (2024). Encuesta de Estructura Salarial (EES). Año 2022. Datos definitivos. Available online: https://www.ine.es/dyngs/INEbase/es/operacion.htm?c=Estadistica_C&cid=1254736177025&menu=ultiDatos&idp=1254735976596#:~:text=%C3%9Altima%20Nota%20de%20prensa&text=El%20salario%20medio%20anual%20fue,que%20el%20del%20a%C3%B1o%20anterior (accessed on 13 February 2025).

- Jackman, P. C., Slater, M. J., Carter, E. E., Sisson, K., & Bird, M. D. (2023). Social support, social identification, mental wellbeing, and psychological distress in doctoral students: A person-centred analysis. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 47(1), 45–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyes, C. L. M. (2002). The mental health continuum: From languishing to flourishing in life. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 43(2), 207–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyes, C. L. M., Shmotkin, D., & Ryff, C. D. (2002). Optimizing well-being: The empirical encounter of two traditions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82(6), 1007–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiely, K. M., Brady, B., & Byles, J. (2019). Gender, mental health and ageing. Maturitas, 129, 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E. S., Tkatch, R., Martin, D., MacLeod, S., Sandy, L., & Yeh, C. (2021). Resilient aging: Psychological well-being and social well-being as targets for the promotion of healthy aging. Gerontology and Geriatric Medicine, 7, 23337214211002951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koushede, V., Lasgaard, M., Hinrichsen, C., Meilstrup, C., Nielsen, L., Rayce, S. B., Torres-Sahli, M., Gudmundsdottir, D. G., Stewart-Brown, S., & Santini, Z. I. (2019). Measuring mental well-being in Denmark: Validation of the original and short version of the Warwick-Edinburgh mental well-being scale (WEMWBS and SWEMWBS) and cross-cultural comparison across four European settings. Psychiatry Research, 271, 502–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loayza-Rivas, J., & Fernández-Castro, J. (2020). Perceived stress and well-being: The role of social support as a protective factor among Peruvian immigrants in Spain. Ansiedad y Estrés, 26(2), 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, M. A., Gabilondo, A., Codony, M., García-Forero, C., Vilagut, G., Castellví, P., Ferrer, M., & Alonso, J. (2013). Adaptation into Spanish of the Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale (WEMWBS) and preliminary validation in a student sample. Quality of Life Research, 22(5), 1099–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyyra, N., Thorsteinsson, E. B., Eriksson, C., Madsen, K. R., Tolvanen, A., Löfstedt, P., & Välimaa, R. (2021). The association between loneliness, mental well-being, and self-esteem among Adolescents in Four Nordic Countries. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(14), 7405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macía, P., Goñi-Balentziaga, O., Vegas, O., & Azkona, G. (2022). Professional quality of life among Spanish veterinarians. Veterinary Record Open, 9(1), e250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, F., Wang, J., Pearce, E., Ma, R., Schlief, M., Lloyd-Evans, B., Ikhtabi, S., & Johnson, S. (2022). Loneliness and the onset of new mental health problems in the general population. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 57(11), 2161–2178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mushtaq, R., Shoib, S., Shah, T., & Mushtaq, S. (2014). Relationship between loneliness, psychiatric disorders and physical health? A review on the psychological aspects of loneliness. Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research, 8(9), WE01–WE04. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (2012). Emotion regulation and psychopathology: The role of gender. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 8, 161–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryff, C. D. (2014). Psychological well-being revisited: Advances in the science and practice of eudaimonia. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 83(1), 10–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saadeh, M., Welmer, A. K., Dekhtyar, S., Fratiglioni, L., & Calderón-Larrañaga, A. (2020). The role of psychological and social well-being on physical function trajectories in older adults. The Journals of Gerontology: Series A, 75(8), 1579–1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salinero-Fort, M., del Otero-Sanz, L., Martín-Madrazo, C., de Burgos-Lunar, C., Chico-Moraleja, R. M., Rodés-Soldevila, B., Jiménez-García, R., Gómez-Campelo, P., & HEALTH & MIGRATION Group. (2011). The relationship between social support and self-reported health status in immigrants: An adjusted analysis in the Madrid Cross Sectional Study. BMC Family Practice, 12, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schönfeld, P., Brailovskaia, J., & Margraf, J. (2017). Positive and negative mental health across the lifespan: A cross-cultural comparison. International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology, 17(3), 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soldevila-Domenech, N., Forero, C. G., Alayo, I., Capella, J., Colom, J., Malmusi, D., Mompart, A., Mortier, P., Puértolas, B., Sánchez, N., Schiaffino, A., Vilagut, G., & Alonso, J. (2021). Mental well-being of the general population: Direct and indirect effects of socioeconomic, relational and health factors. Quality of Life Research, 30(8), 2171–2185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steptoe, A., Deaton, A., & Stone, A. A. (2015). Subjective wellbeing, health, and ageing. Lancet, 385(9968), 640–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thoits, P. A. (1995). Stress, coping, and social support processes: Where are we? What next? Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 53–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, R. M., Igelström, E., Purba, A. K., Shimonovich, M., Thomson, H., McCartney, G., Reeves, A., Leyland, A., Pearce, A., & Katikireddi, S. V. (2022). How do income changes impact on mental health and wellbeing for working-age adults? A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Public Health, 7(6), e515–e528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toribio Caballero, S., Cardenal Hernáez, V., Ávila Espada, A., & Ovejero Bruna, M. M. (2022). Gender roles and women’s mental health: Their influence on the demand for psychological care. Annals of Psychology, 38(1), 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trousselard, M., Steiler, D., Dutheil, F., Claverie, D., Canini, F., Fenouillet, F., Naughton, G., Stewart-Brown, S., & Franck, N. (2016). Validation of the Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-Being Scale (WEMWBS) in French psychiatric and general populations. Psychiatry Research, 245, 282–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchino, B. N. (2006). Social support and health: A review of physiological processes potentially underlying links to disease outcomes. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 29(4), 377–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veenhoven, R. (2015). Social conditions for human happiness: A review of research. International Journal of Psychology, 50(5), 379–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velarde-Mayol, C., Fragua-Gil, S., & García-de-Cecilia, J. M. (2016). Validación de la escala de soledad de UCLA y perfil social en la población anciana que vive sola. Medicina de Familia. SEMERGEN, 42(3), 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J., Mann, F., Lloyd-Evans, B., Ma, R., & Johnson, S. (2018). Associations between loneliness and perceived social support and outcomes of mental health problems: A systematic review. BMC Psychiatry, 18(1), 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X., & Dong, S. (2022). The relationships between social support and loneliness: A meta-analysis and review. Acta Psychologica, 227, 103616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Female | 362 (71.5%) |

| Male | 140 (27.7%) |

| Non-binary | 1 (0.2%) |

| Prefer not to say | 3 (0.6%) |

| Sexual orientation | |

| Asexual | 1 (0.2%) |

| Bisexual | 47 (9.3%) |

| Heterosexual | 400 (79.1%) |

| Homosexual | 43 (8.5%) |

| Pansexual | 2 (0.4%) |

| Prefer not to say | 13 (2.6%) |

| Age | |

| 18–32 | 193 (38.1%) |

| 33–45 | 139 (26.9%) |

| 46–60 | 128 (25.3%) |

| Over 60 | 49 (9.7%) |

| Sentimental relationship | |

| No | 226 (44.7%) |

| Yes | 280 (55.3%) |

| Household composition | |

| Living accompanied | 424 (83.8%) |

| Living alone | 82 (16.2%) |

| Living area | |

| Rural | 91 (18%) |

| Urban | 415 (82%) |

| Education | |

| Primary school | 12 (2.4%) |

| Secondary school | 58 (11.5%) |

| Vocational training | 62 (12.3%) |

| Undergraduate degree | 318 (62.8%) |

| PhD | 56 (11.1%) |

| Employment status | |

| Employed | 347 (68.6%) |

| Retired | 25 (4.9%) |

| Unemployed | 17 (3.4%) |

| University student | 78 (15.4%) |

| Working and studying at the University | 38 (7.7%) |

| Salary range (EUR/year) | |

| Prefer not to say | 18 (3.6%) |

| Students not working | 81 (16%) |

| <28,000 | 212 (41.9%) |

| 28,000–<52,000 | 165 (32.6%) |

| ≥52,000 | 30 (5.9%) |

| Loneliness | |

| Low | 256 (50.6%) |

| Average | 222 (43.9%) |

| High | 28 (5.5%) |

| Social support | |

| Low | 9 (1.8%) |

| Average | 44 (8.7%) |

| High | 453 (89.5%) |

| β | 95% CI | t | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Loneliness | ||||

| Average | −0.686 | −0.84–−0.52 | −8.38 | <0.001 *** |

| High | −1.424 | −1.78–−1.06 | −7.75 | <0.001 *** |

| Social support | ||||

| Average | 0.097 | −0.52–0.70 | 0.31 | 0.754 |

| High | 0.589 | 0.02–1.15 | 2.04 | 0.025 * |

| Income | ||||

| Students not working | 0.085 | −0.16–0.33 | 0.68 | 0.495 |

| €28,000–€52,000 | 0.368 | 0.17–0.56 | 3.72 | <0.001 *** |

| €52,000 | 0.680 | 0.33–1.02 | 3.88 | <0.001 *** |

| Gender | −0.054 | −0.23–0.12 | −0.61 | 0.542 |

| Age | ||||

| 33–45 | −0.071 | −0.29–0.15 | −0.63 | 0.527 |

| 46–60 | −0.047 | −0.28–0.18 | −0.40 | 0.689 |

| Over 60 | −0.248 | −0.55–0.05 | −1.60 | 0.109 |

| Education | ||||

| Secondary school | −0.17 | −0.71–0.38 | −0.61 | 0.540 |

| Vocational training | −0.11 | −0.64–0.42 | −0.42 | 0.670 |

| Undergraduate degree | −0.10 | −0.60–0.40 | −0.40 | 0.683 |

| PhD | −0.07 | −0.62–0.47 | −0.28 | 0.779 |

| Employment status | ||||

| Retired | 0.39 | −0.06–0.85 | 1.70 | 0.088 |

| Unemployed | 0.03 | −0.44–0.51 | 0.14 | 0.889 |

| University student | 0.17 | −0.38–0.73 | 0.62 | 0.532 |

| Working and studying at the University | −0.06 | −0.38–0.26 | −0.39 | 0.695 |

| Loneliness * Social Support | 0.047 | −0.01–0.02- | 0.60 | 0.545 |

| Loneliness * Income | −0.004 | −0.82–0.75 | −0.08 | 0.932 |

| Social Support * Income | −0.046 | −0.25–0.17 | −0.39 | 0.691 |

| Loneliness * Social Support * Income | 0.002 | −0.009–0.009 | 0.06 | 0.947 |

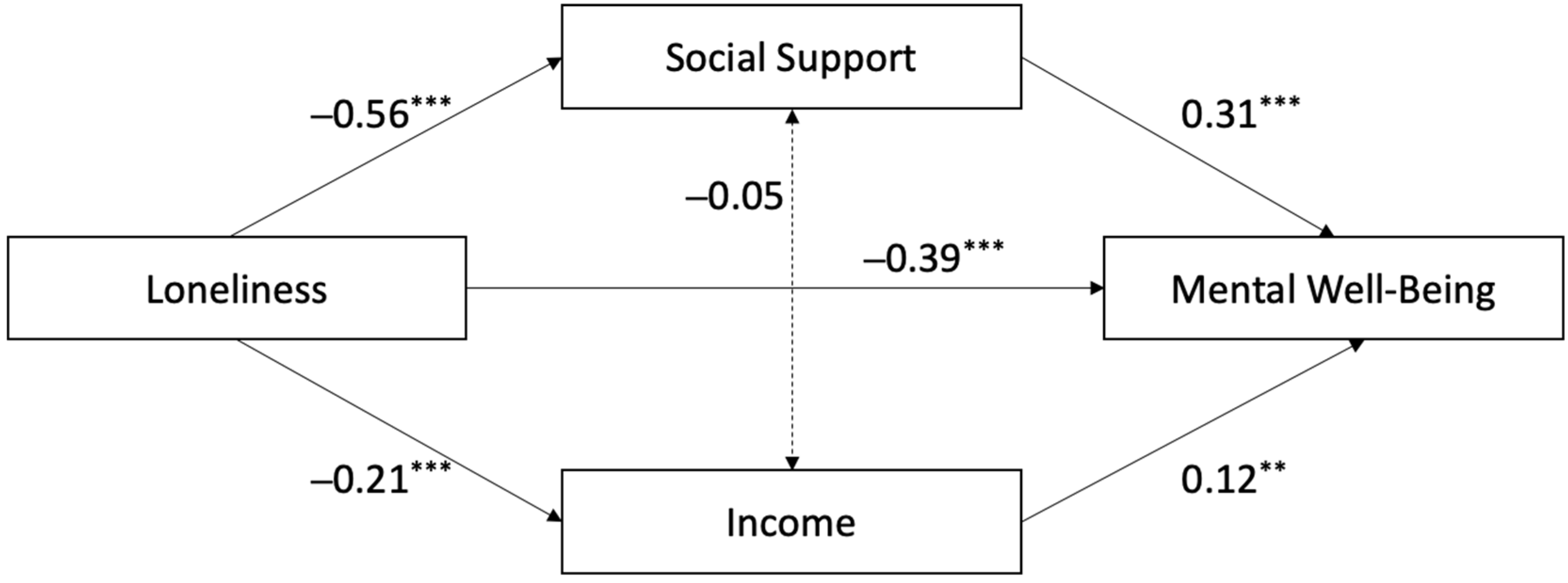

| Pathway | β | 95% CI | z | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct effect | ||||

| Loneliness → Mental Well-being | −0.386 | −0.77–−0.49 | −9.07 | <0.001 *** |

| Indirect effects | ||||

| Loneliness → Social Support → Mental Well-being | −0.173 | −0.36–−0.20 | −6.68 | <0.001 *** |

| Loneliness → Income → Mental Well-being | −0.024 | −0.07–−0.02 | −2.70 | 0.007 ** |

| Total | −0.582 | −1.06–0.83 | −16.09 | <0.001 *** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the University Association of Education and Psychology. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Egaña-Marcos, E.; Collantes, E.; Diez-Solinska, A.; Azkona, G. The Influence of Loneliness, Social Support and Income on Mental Well-Being. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2025, 15, 70. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15050070

Egaña-Marcos E, Collantes E, Diez-Solinska A, Azkona G. The Influence of Loneliness, Social Support and Income on Mental Well-Being. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education. 2025; 15(5):70. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15050070

Chicago/Turabian StyleEgaña-Marcos, Eider, Ezequiel Collantes, Alina Diez-Solinska, and Garikoiz Azkona. 2025. "The Influence of Loneliness, Social Support and Income on Mental Well-Being" European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education 15, no. 5: 70. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15050070

APA StyleEgaña-Marcos, E., Collantes, E., Diez-Solinska, A., & Azkona, G. (2025). The Influence of Loneliness, Social Support and Income on Mental Well-Being. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 15(5), 70. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15050070