Teachers’ Heart Rate Variability and Behavioral Reactions in Aggressive Interactions: Teachers Can Downregulate Their Physiological Arousal, and Progesterone Favors Social Integrative Teacher Responses

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Student Aggression as a Central Source of Teacher Stress

1.2. Risk Factors and Resources

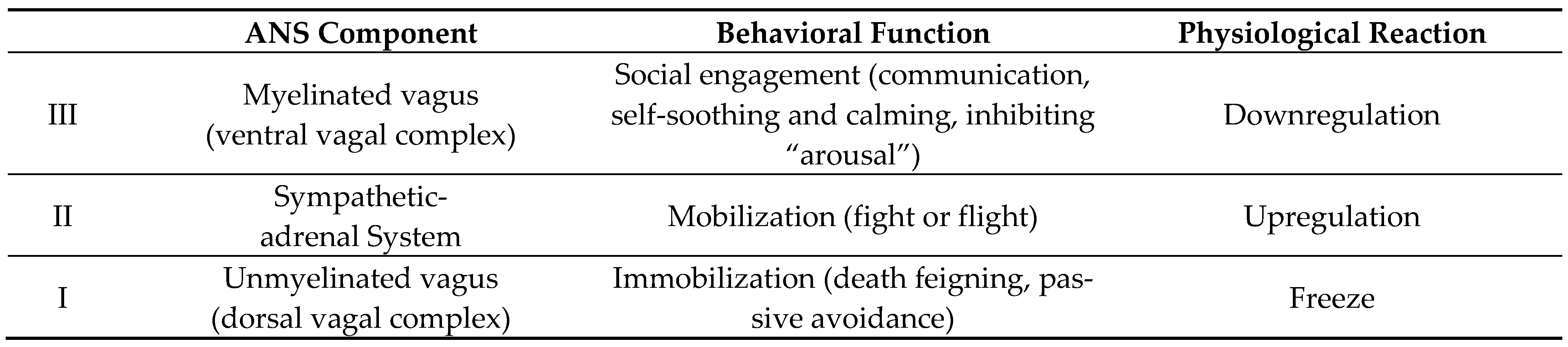

1.3. Physiological Teacher Stress in the Light of Polyvagal Theory

1.4. Present Study

1.5. Research Questions and Hypotheses

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Self-Reports

2.2.2. Classroom Observations

2.2.3. Heart Rate Variability

2.2.4. Progesterone

2.2.5. Overweight (BMI)

2.3. Data Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Student Aggression and Teacher Responses

3.2. Interactional Episodes

3.3. Teacher Responses in the Light of Resources and Risk Factors

3.4. Teachers HRV in Aggressive Interactional Episodes and Associations with Risk Factors and Resources

3.5. Long-Term Effects of Upregulation

4. Discussion

4.1. Student Aggression and Teacher Reaction

4.2. Interactional Episodes

4.3. Teacher Reaction in the Context of Resources and Risk Factors

4.4. Teachers’ HRV in Aggressive Interactional Episodes

4.5. Long-Term Effects of Upregulation

4.6. Strengths, Limitations, and Implications

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Agyapong, B.; Brett-MacLean, P.; Burback, L.; Agyapong, V.I.O.; Wei, Y. Interventions to Reduce Stress and Burnout among Teachers: A Scoping Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 5625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iriarte Redín, C.; Erro-Garcés, A. Stress in teaching professionals across Europe. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2020, 103, 101623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aloe, A.M.; Amo, L.C.; Shanahan, M.E. Classroom management self-efficacy and burnout: A multivariate meta-analysis. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2014, 26, 101–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wettstein, A.; Scherzinger, M. Unterrichtsstörungen Verstehen und Wirksam Vorbeugen, 2nd ed.; Kohlhammer: Stuttgart, Germany, 2022; ISBN 9783170421349. [Google Scholar]

- Doyle, W. Classroom Organization and Management. In Handbook of Research on Teaching, 3rd ed.; Witttrock, M.C., Ed.; Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Lortie, D.C. Schoolteacher: A Sociological Study, 2nd ed.; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2002; ISBN 9780226773230. [Google Scholar]

- Wettstein, A. Die Wahrnehmung sozialer Prozesse im Unterricht. Schweiz. Z. Heilpädagogik 2013, 19, 5–13. [Google Scholar]

- Blase, J.J. A Qualitative Analysis of Sources of Teacher Stress: Consequences for Performance. Am. Educ. Res. J. 1986, 23, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyle, G.J.; Borg, M.G.; Falzon, J.M.; Baglioni, A.J. A structural model of the dimensions of teacher stress. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 1995, 65, 49–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evers, W.J.G.; Tomic, W.; Brouwers, A. Burnout among Teachers: Students’ and Teachers’ Perceptions Compared. Sch. Psychol. Int. 2004, 25, 131–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsouloupas, C.N.; Carson, R.L.; Matthews, R.; Grawitch, M.J.; Barber, L.K. Exploring the association between teachers’ perceived student misbehaviour and emotional exhaustion: The importance of teacher efficacy beliefs and emotion regulation. Educ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 173–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, C.A.; Bushman, B.J. Human aggression. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2002, 53, 27–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humpert, W.; Dann, H.-D. Das Beobachtungssystem BAVIS: Ein Beobachtungsverfahren zur Analyse von Aggressionsbezogenen Interaktionen im Schulunterricht; Hogrefe: Göttingen, Germany, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Wettstein, A. Beobachtungssystem zur Analyse Aggressiven Verhaltens in Schulischen Settings (BASYS); Huber: Bern, Switzerland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Hollenstein, T. (Ed.) State Space Grids. In State Space Grids; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2013; pp. 11–33. [Google Scholar]

- Lamey, A.; Hollenstein, T.; Lewis, M.D.; Granic, I. Gridware; Version 1.1; Adolescent Dynamics Lab.: Kingston, ON, Canada, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Granic, I.; Hollenstein, T. Dynamic systems methods for models of developmental psychopathology. Dev. Psychopathol. 2003, 15, 641–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granic, I.; Lamey, A.V. Combining dynamic systems and multivariate analyses to compare the mother-child interactions of externalizing subtypes. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2002, 30, 265–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hollenstein, T.; Granic, I.; Stoolmiller, M.; Snyder, J. Rigidity in parent-child interactions and the development of externalizing and internalizing behavior in early childhood. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2004, 32, 595–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mainhard, T.M.; Pennings, H.J.M.; Wubbels, T.; Brekelmans, M. Mapping control and affiliation in teacher-student interaction with State Space Grids. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2012, 28, 1027–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennings, H.J.M.; Brekelmans, M.; Wubbels, T.; van der Want, A.C.; Claessens, L.C.A.; van Tartwijk, J. A nonlinear dynamical systems approach to real-time teacher behavior: Differences between teachers. Nonlinear Dyn. Psychol. Life Sci. 2014, 18, 23–45. [Google Scholar]

- Pennings, H.J.M.; Brekelmans, M.; Sadler, P.; Claessens, L.C.; van der Want, A.C.; van Tartwijk, J. Interpersonal adaptation in teacher-student interaction. Learn. Instr. 2018, 55, 41–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennings, H.J.M.; Hollenstein, T. Teacher-Student Interactions and Teacher Interpersonal Styles: A State Space Grid Analysis. J. Exp. Educ. 2020, 88, 382–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennings, H.J.M.; Mainhard, T. Analyzing Teacher-Student Interactions with State Space Grids. In Complex Dynamical Systems in Education: Concepts, Methods and Applications; Koopmans, M., Stamovlasis, D., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 233–271. ISBN 978-3-319-27577-2. [Google Scholar]

- Scherzinger, M.; Roth, B.; Wettstein, A. Pädagogische Interaktionen als Grundbaustein der Lehrperson-Schüler*innen-Beziehung. Die Erfassung mit State Space Grids. Unterrichtswissenschaft 2021, 49, 303–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherzinger, M.; Roth, B.; Wettstein, A. Soziale Interaktionen in pädagogischen Beziehungen. Erfassung mit State Space Grids. In Lehrer. Bildung. Gestalten. Beiträge zur Empirischen Forschung in der Lehrerbildung; Ehmke, T., Kuhl, P., Pietsch, M., Eds.; Beltz Juventa: Weinheim, Germany, 2019; pp. 314–324. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus, R.S.; Folkman, S. Stress, Appraisal, and Coping; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1984; ISBN 9780826141927. [Google Scholar]

- Flink, C.; Boggiano, A.K.; Barrett, M. Controlling teaching strategies: Undermining children’s self-determination and performance. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1990, 59, 916–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelletier, L.G.; Séguin-Lévesque, C.; Legault, L. Pressure from above and pressure from below as determinants of teachers’ motivation and teaching behaviors. J. Educ. Psychol. 2002, 94, 186–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skinner, E.A.; Belmont, M.J. Motivation in the classroom: Reciprocal effects of teacher behavior and student engagement across the school year. J. Educ. Psychol. 1993, 85, 571–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuevas, R.; Ntoumanis, N.; Fernandez-Bustos, J.G.; Bartholomew, K. Does teacher evaluation based on student performance predict motivation, well-being, and ill-being? J. Sch. Psychol. 2018, 68, 154–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernet, C.; Guay, F.; Senécal, C.; Austin, S. Predicting intraindividual changes in teacher burnout: The role of perceived school environment and motivational factors. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2012, 28, 514–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartholomew, K.J.; Ntoumanis, N.; Cuevas, R.; Lonsdale, C. Job pressure and ill-health in physical education teachers: The mediating role of psychological need thwarting. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2014, 37, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Travers, C.J.; Cooper, C.L. Teachers under Pressure: Stress in the Teaching Profession; Routledge: London, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Judge, T.A.; Klinger, R. Job satisfaction: Subjective well-being at work. In The Science of Subjective Well-Being; Eid, M., Larsen, R.J., Eds.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 393–413. [Google Scholar]

- Wettstein, A.; Jenni, G.; Schneider, I.; Kühne, F.; grosse Holtforth, M.; La Marca, R. Predictors of Psychological Strain and Allostatic Load in Teachers: Examining the Long-Term Effects of Biopsychosocial Risk and Protective Factors Using a LASSO Regression Approach. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 5760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Childs, E.; van Dam, N.T.; de Wit, H. Effects of acute progesterone administration upon responses to acute psychosocial stress in men. Exp. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2010, 18, 78–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Judge, T.A.; Zhang, S.C.; Glerum, D.R. Job Satisfaction. In Essentials of Job Attitudes and Other Workplace Psychological Constructs, 1st ed.; Sessa, V.I., Bowling, N.A., Eds.; Routledge Taylor & Francis Group: New York, NY, USA, 2021; ISBN 9780429325755. [Google Scholar]

- Wirth, M.M. Beyond the HPA Axis: Progesterone-Derived Neuroactive Steroids in Human Stress and Emotion. Front. Endocrinol. 2011, 2, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiorilli, C.; Gabola, P.; Pepe, A.; Meylan, N.; Curchod-Ruedi, D.; Albanese, O.; Doudin, P.-A. The effect of teachers’ emotional intensity and social support on burnout syndrome. A comparison between Italy and Switzerland. Eur. Rev. Appl. Psychol. 2015, 65, 275–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakanen, J.J.; Bakker, A.B.; Schaufeli, W.B. Burnout and work engagement among teachers. J. Sch. Psychol. 2006, 43, 495–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, C.; Lan, J.; Li, Y.; Feng, W.; You, X. The mediating role of workplace social support on the relationship between trait emotional intelligence and teacher burnout. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2015, 51, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, D.Y.P.; Lee, W.W.S. Predicting intention to quit among Chinese teachers: Differential predictability of the components of burnout. Anxiety Stress Coping 2006, 19, 129–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, S.L.; Fredrickson, B.L.; Wirth, M.M.; Poulin, M.J.; Meier, E.A.; Heaphy, E.D.; Cohen, M.D.; Schultheiss, O.C. Social closeness increases salivary progesterone in humans. Horm. Behav. 2009, 56, 108–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wirth, M.M.; Schultheiss, O.C. Effects of affiliation arousal (hope of closeness) and affiliation stress (fear of rejection) on progesterone and cortisol. Horm. Behav. 2006, 50, 786–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denson, T.F.; O’Dean, S.M.; Blake, K.R.; Beames, J.R. Aggression in Women: Behavior, Brain and Hormones. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2018, 12, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology; the North American Society of Pacing and Electrophysiology. Heart rate variability: Standards of measurement, physiological interpretation and clinical use. Circulation 1996, 93, 1043–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinel, J.P.J. Basics of Biopsychology; Pearson Allyn and Bacon: Boston, MA, USA, 2007; ISBN 0205461085. [Google Scholar]

- Beuchel, P.; Cramer, C. Heart Rate Variability and Perceived Stress in Teacher Training: Facing the Reality Shock With Mindfulness? Glob. Adv. Integr. Med. Health 2023, 12, 27536130231176538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scheuch, K.; Knothe, M. Psychophysische Beanspruchung von Lehrern in der Unterrichtstätigkeit. In Jahrbuch für Lehrerforschung; Tippelt, R., Schmidt, B., Eds.; Juventa: Weinheim, Germany, 1997; pp. 285–299. [Google Scholar]

- Schwerdtfeger, A.; Konermann, L.; Schönhofen, K. Self-efficacy as a health-protective resource in teachers? A biopsychological approach. Health Psychol. 2008, 27, 358–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wettstein, A.; Kühne, F.; Tschacher, W.; La Marca, R. Ambulatory assessment of psychological and physiological stress on workdays and free days among teachers. A preliminary study. Front. Neurosci. 2020, 14, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donker, M.H.; van Gog, T.; Goetz, T.; Roos, A.-L.; Mainhard, T. Associations between teachers’ interpersonal behavior, physiological arousal, and lesson-focused emotions. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2020, 63, 101906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porges, S.W. Orienting in a defensive world: Mammalian modifications of our evolutionary heritage. A Polyvagal Theory. Psychophysiology 1995, 32, 301–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porges, S.W. Polyvagal Theory: A biobehavioral journey to sociality. Compr. Psychoneuroendocrinol. 2021, 7, 100069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porges, S.W. Social engagement and attachment: A phylogenetic perspective. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2003, 1008, 31–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porges, S.W. Emotion: An evolutionary by-product of the neural regulation of the autonomic nervous system. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1997, 807, 62–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laurence, G.A.; Fried, Y.; Raub, S. Evidence for the need to distinguish between self-initiated and organizationally imposed overload in studies of work stress. Work Stress 2016, 30, 337–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Appels, A.; Mulder, P. Excess fatigue as a precursor of myocardial infarction. Eur. Heart J. 1988, 9, 758–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kouvonen, A.; Kivimäki, M.; Cox, S.J.; Cox, T.; Vahtera, J. Relationship between work stress and body mass index among 45,810 female and male employees. Psychosom. Med. 2005, 67, 577–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wardle, J.; Chida, Y.; Gibson, E.L.; Whitaker, K.L.; Steptoe, A. Stress and adiposity: A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Obesity 2011, 19, 771–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harding, J.L.; Backholer, K.; Williams, E.D.; Peeters, A.; Cameron, A.J.; Hare, M.J.; Shaw, J.E.; Magliano, D.J. Psychosocial stress is positively associated with body mass index gain over 5 years: Evidence from the longitudinal AusDiab study. Obesity 2014, 22, 277–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Epel, E.S.; Crosswell, A.D.; Mayer, S.E.; Prather, A.A.; Slavich, G.M.; Puterman, E.; Mendes, W.B. More than a feeling: A unified view of stress measurement for population science. Front. Neuroendocrinol. 2018, 49, 146–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- La Marca, R.; Schneider, S.; Jenni, G.; Kühne, F.; grosse Holtforth, M.; Wettstein, A. Associations between stress, resources, and hair cortisol concentration in teachers. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2023, 154, 106291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wettstein, A.; Schneider, S.; grosse Holtforth, M.; La Marca, R. Teacher stress: A psychobiological approach to stressful interactions in the classroom. Front. Educ. 2021, 6, 681258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagemann, W.; Geuenich, K. Burnout-Screening-Skalen, 2nd ed.; Hogrefe: Göttingen, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Schulz, P.; Schlotz, W.; Becker, P. Trierer Inventar zum Chronischen Stress (TICS), 1st ed.; Hogrefe: Göttingen, Germany, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Rau, R.; Gebele, N.; Morling, K.; Rösler, U. Untersuchung Arbeitsbedingter Ursachen für das Auftreten von Depressiven Störungen: Forschung Projekt F 186; Bundesanstalt für Arbeitsschutz und Arbeitsmedizin: Dortmund/Berlin/Dresden, Germany, 2010; ISBN 978-3-88261-114-4. [Google Scholar]

- Fuss, S.; Karbach, U. Grundlagen der Transkription. Eine praktische Einführung, 2nd ed.; UTB: Stuttgart, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Laborde, S.; Mosley, E.; Thayer, J.F. Heart Rate Variability and Cardiac Vagal Tone in Psychophysiological Research—Recommendations for Experiment Planning, Data Analysis, and Data Reporting. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niskanen, J.-P.; Tarvainen, M.P.; Ranta-Aho, P.O.; Karjalainen, P.A. Software for advanced HRV analysis. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2004, 76, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaffer, F.; McCraty, R.; Zerr, C.L. A healthy heart is not a metronome: An integrative review of the heart’s anatomy and heart rate variability. Front. Psychol. 2014, 5, 1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wennig, R. Potential problems with the interpretation of hair analysis results. Forensic Sci. Int. 2000, 107, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, W.; Stalder, T.; Foley, P.; Rauh, M.; Deng, H.; Kirschbaum, C. Quantitative analysis of steroid hormones in human hair using a column-switching LC-APCI-MS/MS assay. J. Chromatogr. B Analyt. Technol. Biomed. Life Sci. 2013, 928, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juster, R.-P.; McEwen, B.S.; Lupien, S.J. Allostatic load biomarkers of chronic stress and impact on health and cognition. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2010, 35, 2–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clunies-Ross, P.; Little, E.; Kienhuis, M. Self-reported and actual use of proactive and reactive classroom management strategies and their relationship with teacher stress and student behaviour. Educ. Psychol. 2008, 28, 693–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romi, S.; Lewis, R.; Roache, J.; Riley, P. The impact of teachers’ aggressive management techniques on students’ attitudes to schoolwork. J. Educ. Res. 2011, 104, 231–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montuoro, P.; Lewis, R. Personal responsibility and behavioral disengagement in innocent bystanders during classroom management events: The moderating effect of teacher aggressive tendencies. J. Educ. Res. 2018, 111, 439–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherzinger, M.; Wettstein, A. Classroom disruptions, the teacher-student relationship and classroom management from the perspective of teachers, students and external observers: A multimethod approach. Learn. Environ. Res. 2019, 22, 101–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dann, H.-D.; Humpert, W. Eine empirische Analyse der Handlungswirksamkeit subjektiver Theorien von Lehrern in aggressionshaltigen Unterrichtssituationen. Z. Sozialpsychologie 1987, 18, 40–49. [Google Scholar]

- Holmgreen, L.; Tirone, V.; Gerhart, J.; Hobfoll, S.E. Conservation of Resources Theory. In The Handbook of Stress and Health; Cooper, C.L., Quick, J.C., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 443–457. ISBN 9781118993774. [Google Scholar]

- Virtanen, A.; De Bloom, J.; Kinnunen, U. Relationships between recovery experiences and well-being among younger and older teachers. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 2020, 93, 213–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneider, S.; grosse Holtforth, M.; Wettstein, A.; Jenni, G.; Kühne, F.; Tschacher, W.; La Marca, R. The diurnal course of salivary cortisol and alpha-amylase on workdays and leisure days in teachers and the role of social isolation and neuroticism. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0286475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Teacher Responses to Student Aggression | Teacher Behavior in Overall Interaction | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | |

| Social integrative | 4 | 2.4 | 11 | 3.7 |

| Humor | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Empathize | 1 | 0.6 | 4 | 1.3 |

| Encourage | 1 | 0.6 | 4 | 1.3 |

| Integrate | 2 | 1.2 | 2 | 0.7 |

| Suggest compromise | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.3 |

| Neutral | 150 | 89.8 | 242 | 80.9 |

| Observe/ignore | 110 | 65.9 | 160 | 53.5 |

| Stop | 17 | 10.2 | 40 | 13.4 |

| Admonish | 23 | 13.8 | 42 | 14.1 |

| Punitive | 10 | 6.0 | 34 | 11.4 |

| Threaten | 1 | 0.6 | 8 | 2.7 |

| Punish | 2 | 1.2 | 6 | 2.0 |

| Belittle | 7 | 4.2 | 20 | 6.7 |

| Other | 3 | 1.8 | 12 | 4.0 |

| Total | 167 | 100.0 | 299 | 100.0 |

| Teacher behavior | social integrative | 1.3% | 0% | 2.0% |

| neutral | 50.2% | 18.1% | 11.4% | |

| punitive | 3.3% | 4.0% | 3.3% | |

| aggressive | disruptive | prosocial | ||

| Student behavior | ||||

| Variable | Punitive | Non-Punitive | Social | Non-Social |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Interaction turns a | 15.25 | 14.00 | 15.67 | 14.00 |

| 2. Student aggression a | 7.65 | 6.05 | 7.12 | 6.51 |

| 3. Seeking positive experiences | 3.88 | 3.75 | 3.50 | 3.93 |

| 4. Support from school team | 4.50 | 4.67 | 4.00 | 4.86 |

| 5. Support from school administration | 3.00 | 3.83 | 3.00 | 3.71 |

| 6. Work satisfaction | 4.65 | 4.83 | 5.07 | 4.63 |

| 7. Progesterone | 1.10 | 1.24 | 1.83 | 0.91 |

| 8. Pressure to succeed | 1.83 | 1.43 | 1.44 | 1.65 |

| 9. Work overload t0 | 1.65 | 1.50 | 1.37 | 1.64 |

| 10. Occupational problems t0 | 2.13 | 1.63 | 1.77 | 1.86 |

| 11. Self-related problems t0 | 1.75 | 1.83 | 1.53 | 1.91 |

| 12. Vital exhaustion t0 | 1.44 | 1.53 | 1.37 | 1.55 |

| 13. Body mass index t0 | 24.28 | 22.79 | 23.17 | 23.48 |

| Variable | RMSSD_d | SDNN_d | HR_d |

|---|---|---|---|

| Seeking positive experiences | −0.03 | −0.05 | −0.70 * |

| Support school administration | −0.77 ** | −0.85 ** | −0.09 |

| Progesterone | 0.23 | −0.02 | −0.06 |

| Work overload t0 | 0.06 | 0.29 | 0.74 ** |

| Work overload t1 | 0.19 | 0.72 * | 0.89 ** |

| Work overload t2 | 0.22 | 0.07 | 0.72 * |

| Occupational problems t0 | 0.17 | 0.52 | 0.30 |

| Occupational problems t1 | −0.03 | 0.40 | 0.74 * |

| Occupational problems t2 | 0.23 | −0.11 | 0.59 |

| Self-related problems t0 | 0.44 | 0.67 * | 0.74 ** |

| Self-related problems t1 | 0.36 | 0.46 | 0.89 ** |

| Self-related problems t2 | 0.12 | 0.03 | 0.70 * |

| Vital exhaustion t0 | 0.19 | 0.52 | 0.63 * |

| Vital exhaustion t1 | −0.04 | 0.31 | 0.72 * |

| Vital exhaustion t2 | −0.26 | 0.02 | 0.58 |

| BMI t0 | 0.82 ** | 0.51 | 0.08 |

| BMI t1 | 0.70 * | 0.22 | 0.41 |

| BMI t2 | 0.76 * | 0.63 * | 0.75 * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wettstein, A.; Krähling, S.; Jenni, G.; Schneider, I.; Kühne, F.; grosse Holtforth, M.; La Marca, R. Teachers’ Heart Rate Variability and Behavioral Reactions in Aggressive Interactions: Teachers Can Downregulate Their Physiological Arousal, and Progesterone Favors Social Integrative Teacher Responses. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2024, 14, 2230-2247. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe14080149

Wettstein A, Krähling S, Jenni G, Schneider I, Kühne F, grosse Holtforth M, La Marca R. Teachers’ Heart Rate Variability and Behavioral Reactions in Aggressive Interactions: Teachers Can Downregulate Their Physiological Arousal, and Progesterone Favors Social Integrative Teacher Responses. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education. 2024; 14(8):2230-2247. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe14080149

Chicago/Turabian StyleWettstein, Alexander, Sonja Krähling, Gabriel Jenni, Ida Schneider, Fabienne Kühne, Martin grosse Holtforth, and Roberto La Marca. 2024. "Teachers’ Heart Rate Variability and Behavioral Reactions in Aggressive Interactions: Teachers Can Downregulate Their Physiological Arousal, and Progesterone Favors Social Integrative Teacher Responses" European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education 14, no. 8: 2230-2247. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe14080149

APA StyleWettstein, A., Krähling, S., Jenni, G., Schneider, I., Kühne, F., grosse Holtforth, M., & La Marca, R. (2024). Teachers’ Heart Rate Variability and Behavioral Reactions in Aggressive Interactions: Teachers Can Downregulate Their Physiological Arousal, and Progesterone Favors Social Integrative Teacher Responses. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 14(8), 2230-2247. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe14080149