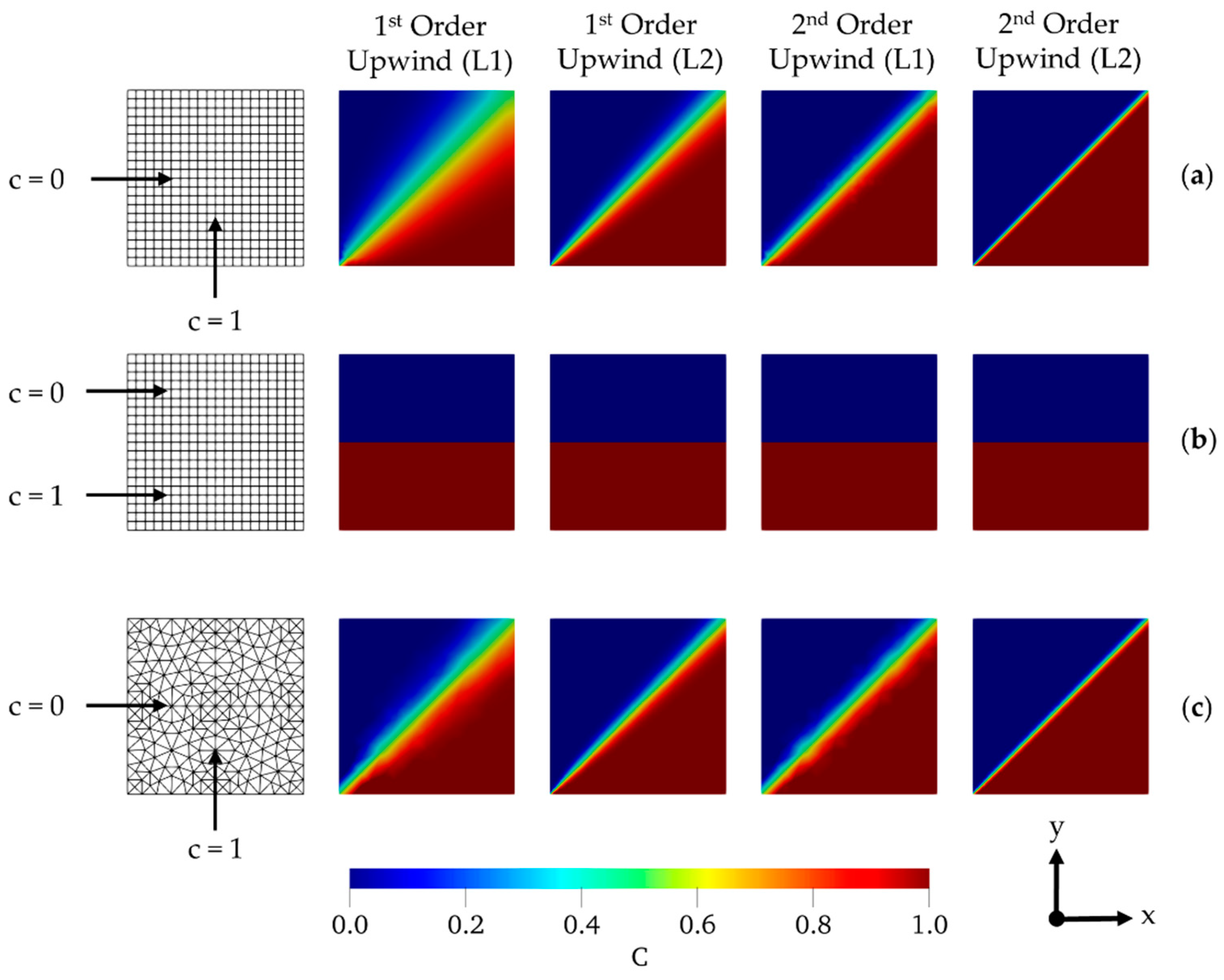

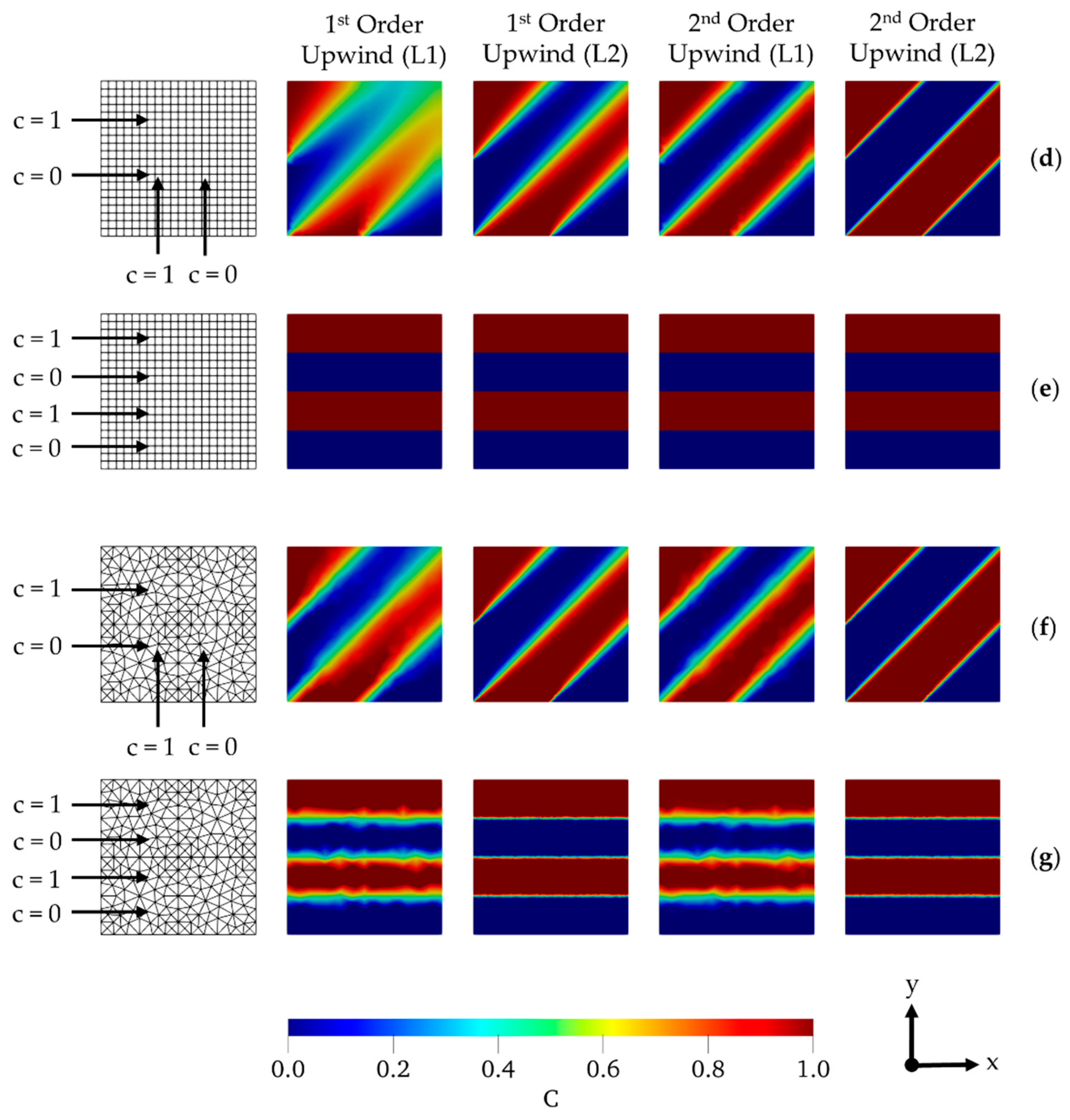

5.1. Numerical Diffusion in Fluid Flow and Scalar Transport (DM = 3 × 10−10 m2/s)

In numerical micromixer investigations, mesh characterization is a critical step to identify and control numerical errors which fundamentally originate from the properties of the mesh. In the current passive micromixer literature, there is no standard and accepted procedure for grid sensitivity analysis. Generally, tested mesh properties (e.g., grid size, grid type, mesh density, and element positioning etc.) are chosen as a rule of thumb or they are based on computational limits. However, these properties need to be considered and used appropriately depending on the physical problem type to avoid reporting unphysical mixing results in numerical simulations as remarked in References [

9,

10,

11] and in also the present study. For instance, the selected mesh level in References [

19,

25] was primarily considered to resolve the flow field instead of solute transport although quite high Peclet numbers (e.g., on the order 10

4–10

6) were examined. In several papers [

14,

17,

27,

28], very close mesh densities were employed for grid studies which implies that the effects of numerical diffusion cannot be revealed clearly. In these applications, numerical simulations may be considered as grid-independent with a minimal error percentage even though a serious amount of error remains in the reported results. On the other hand, in some studies [

2,

13,

14,

17,

27], low or moderate Re or Pe cases were used to determine a grid level, but higher Re or Pe case results were reported in these studies which are inconsistent.

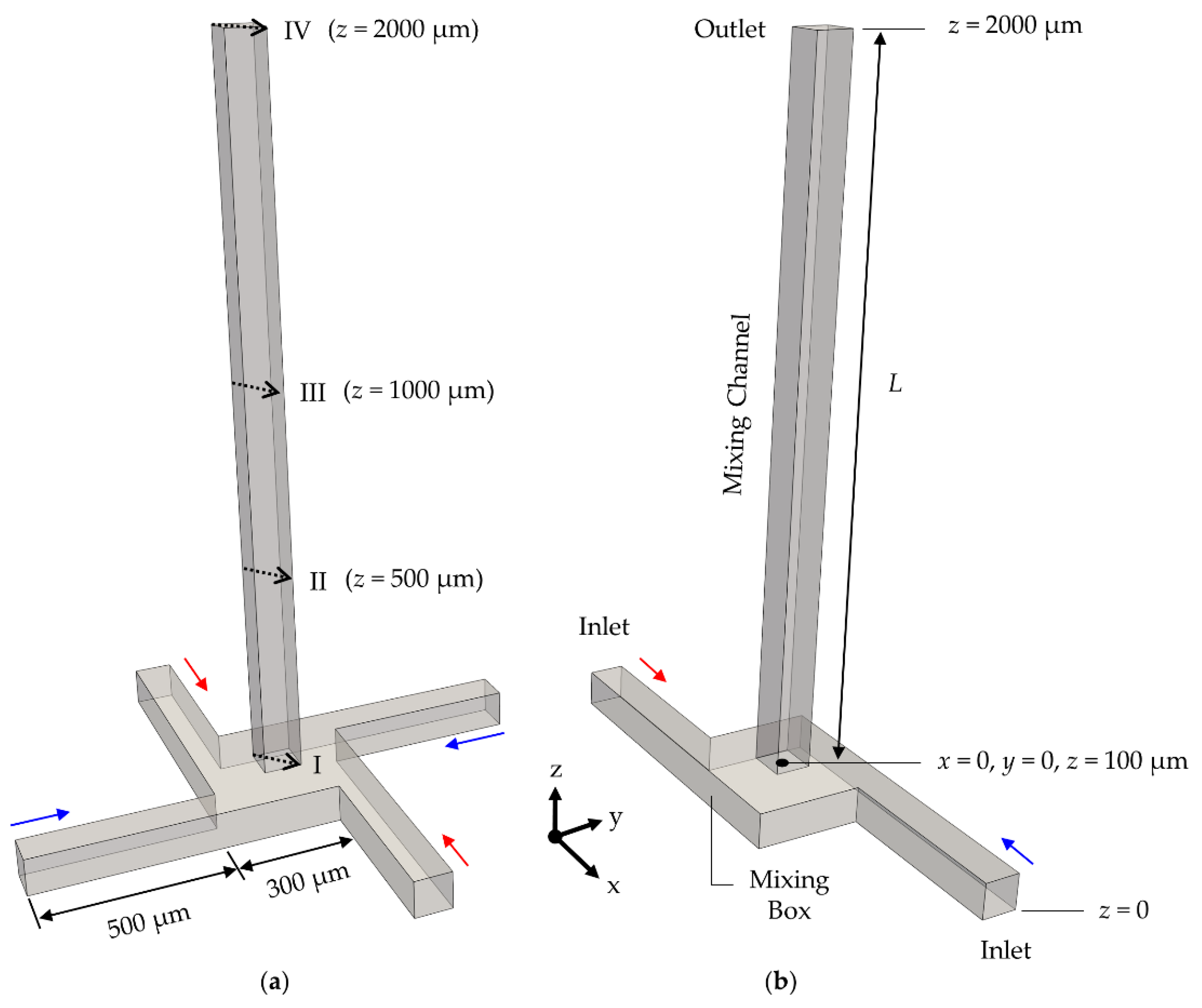

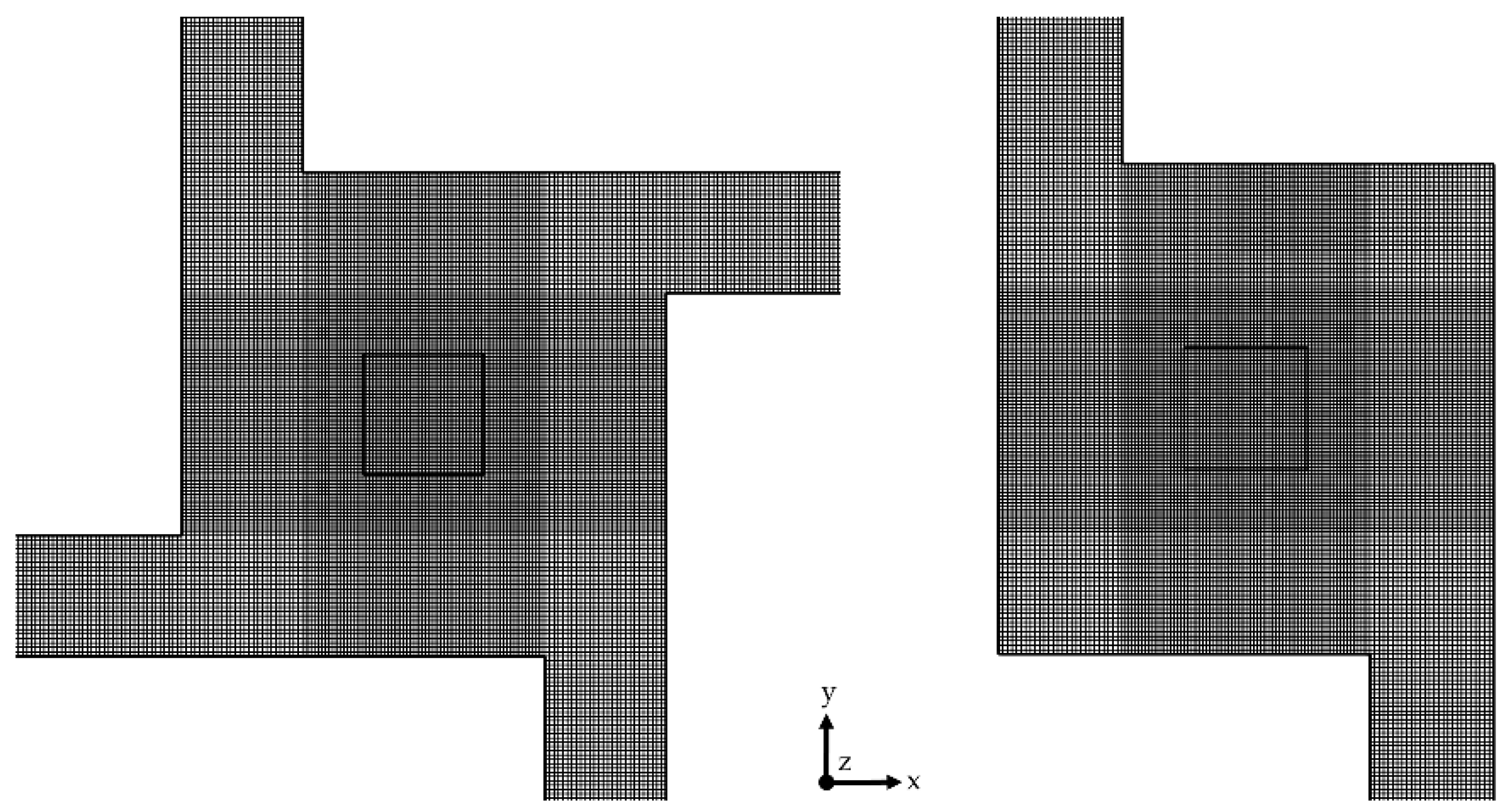

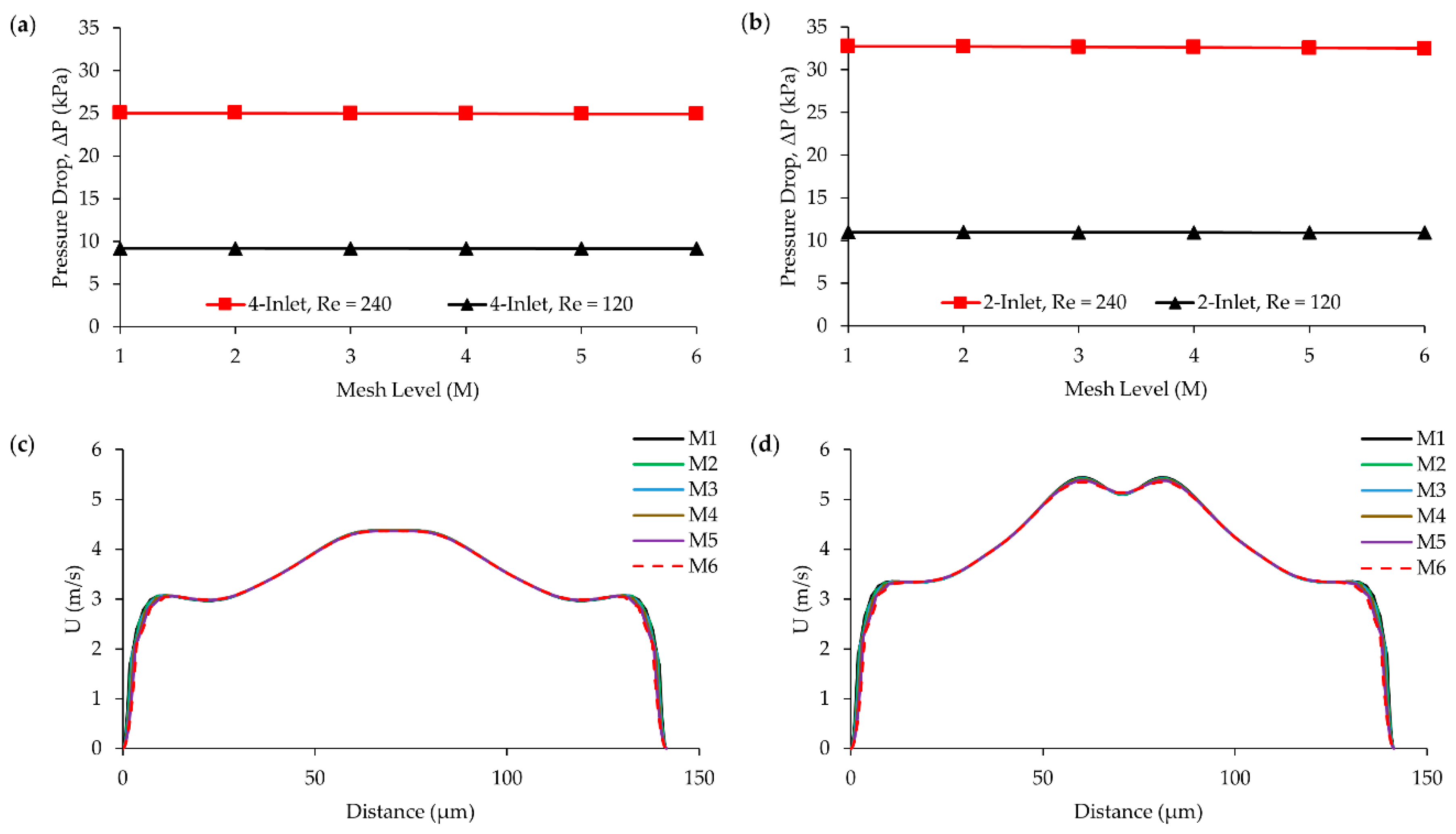

Considering the above practices, six different mesh levels were determined for the micromixers designed to observe numerical diffusion in fluid flow and scalar transport. The density difference between M1 and M6 levels is around 14 million and 13 million for four-inlet and two-inlet micromixers respectively. Such a big density difference between meshes is necessary to capture the numerical diffusion effects in terms of the characteristics of the physical problem.

Figure 5 shows the mesh study results for fluid flow at Re = 240 based on two different flow parameters, pressure drop in micromixers and velocity distribution at the exit of the mixing box (Line-I in

Figure 3) where the most complex flow profile is observed. It is clear from

Figure 5c,d that fluid flow was resolved identically for all mesh levels. The maximum difference between M1 and M6 for both parameters is less than 1%. As mentioned before, this small difference between grid levels occurred as a result of the relatively high kinematic viscosity (e.g.,

ν = 10

−6 m

2/s) of the fluids which leads to very low average cell Reynolds numbers (Re

Δ =

uΔ

x/

ν) in the computational domain. At Re = 240, even the biggest grid size (M6) results in an average Re

Δ number around 6 in the mixing channel which creates an insignificant amount of numerical diffusion in the flow solution. Meanwhile, the numerical diffusion term in fluid flow is used for numerical viscosity (or artificial viscosity) as discussed in Reference [

11].

In contrast to the consistency between mesh levels in terms of the resolution of the flow field, transport simulations showed high discrepancy as a result of higher Pe

Δ numbers as given in

Table 2, when

DM = 3 × 10

−10 m

2/s, which indicates the occurrence of sharp concentration gradients in the computational domain.

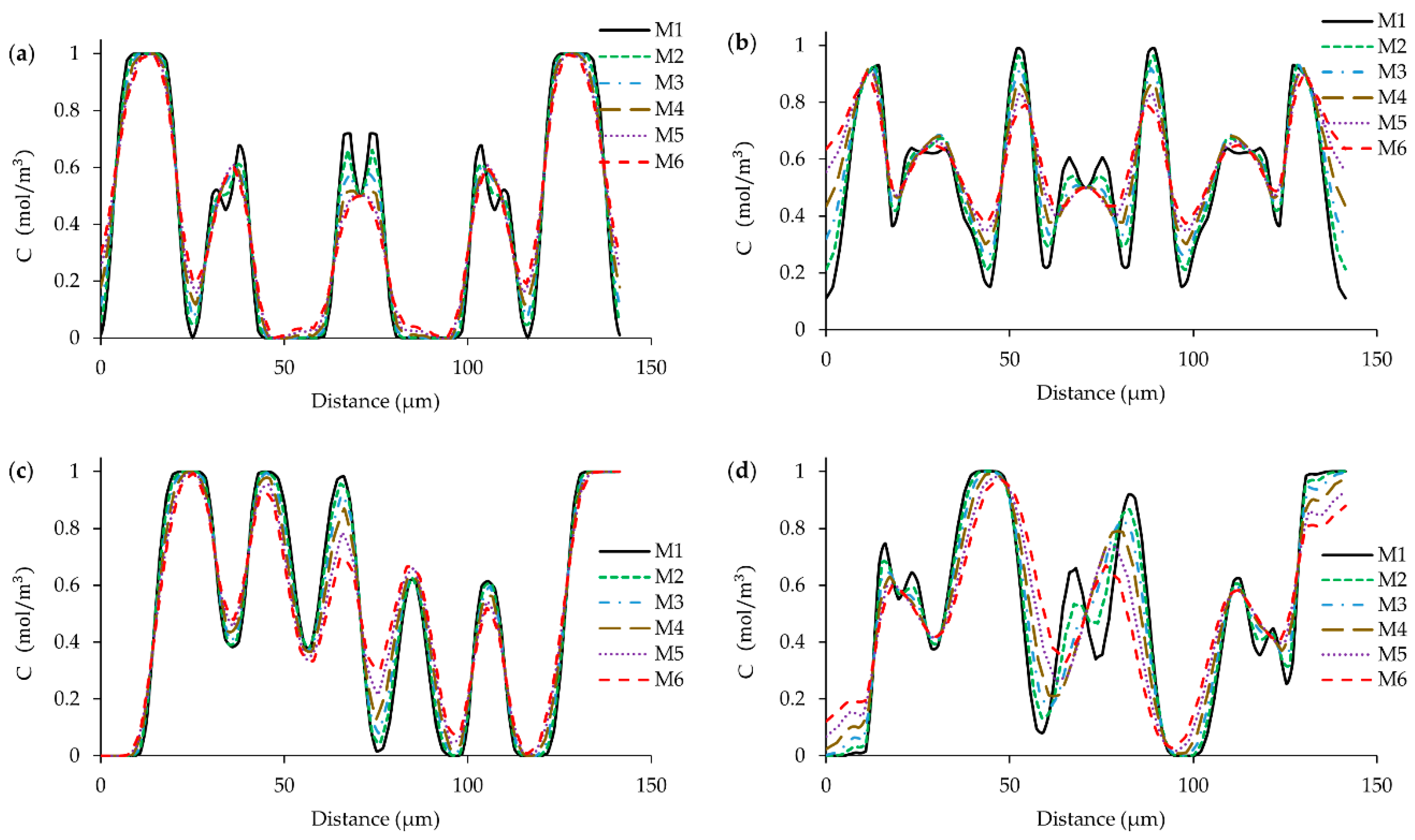

Figure 6 and

Figure 7 show scalar transport results for different mesh levels at Re = 240 and 120 flow conditions respectively. In each figure, while “a and b” and “c and d” plots represent four-inlet and two-inlet micromixer configurations, “a and c” and “b and d” plots show concentration distributions on Line-I and Line-II, as positioned in

Figure 3, respectively. In both flow scenarios, while all mesh levels in both micromixer configurations exhibit relatively similar concentration distributions at the exit of the mixing box, these concentration trends differentiate at

z = 500 µm in the mixing channel. This is because swirl motion starts in the mixing box and continually develops in the streamwise direction. Therefore, during the rotational flow of fluid pairs in the mixing channel, the transport solution starts producing numerical diffusion depending on the swirl profile that develops and the magnitude of the average Pe

Δ number for a specific mesh level. As a result of the flow patterns generated, concentration trends on the same sampling lines and variations between mesh levels are quite different for four-inlet and two-inlet configurations. In both micromixer configurations, however, there is a distinct difference between mesh levels M1 and M6 in terms of the resolution of the concentration field at

z = 500 µm as shown in plots (b) and (d) of

Figure 6 and

Figure 7. Such a large variation emerged as a result of a doubled average Pe

Δ number between mesh levels M1 and M6 which are 10,000 and 20,000 for Re = 240 and 5000 and 10,000 for Re = 120 respectively. Meanwhile, variations between all mesh levels are obviously smaller in the Re = 120 when compared to the Re = 240 case, due to smaller average Pe

Δ numbers which generate relatively less numerical diffusion. On the other hand, although increasing the mesh density helps to resolve differences in concentration trends, still the finest mesh may contain a substantial amount of numerical diffusion because the average Pe

Δ number is still in the order of 5000 even for the best-case scenario tested in this section (e.g., Re = 120, M1 Level, and

DM = 3 × 10

−10 m

2/s).

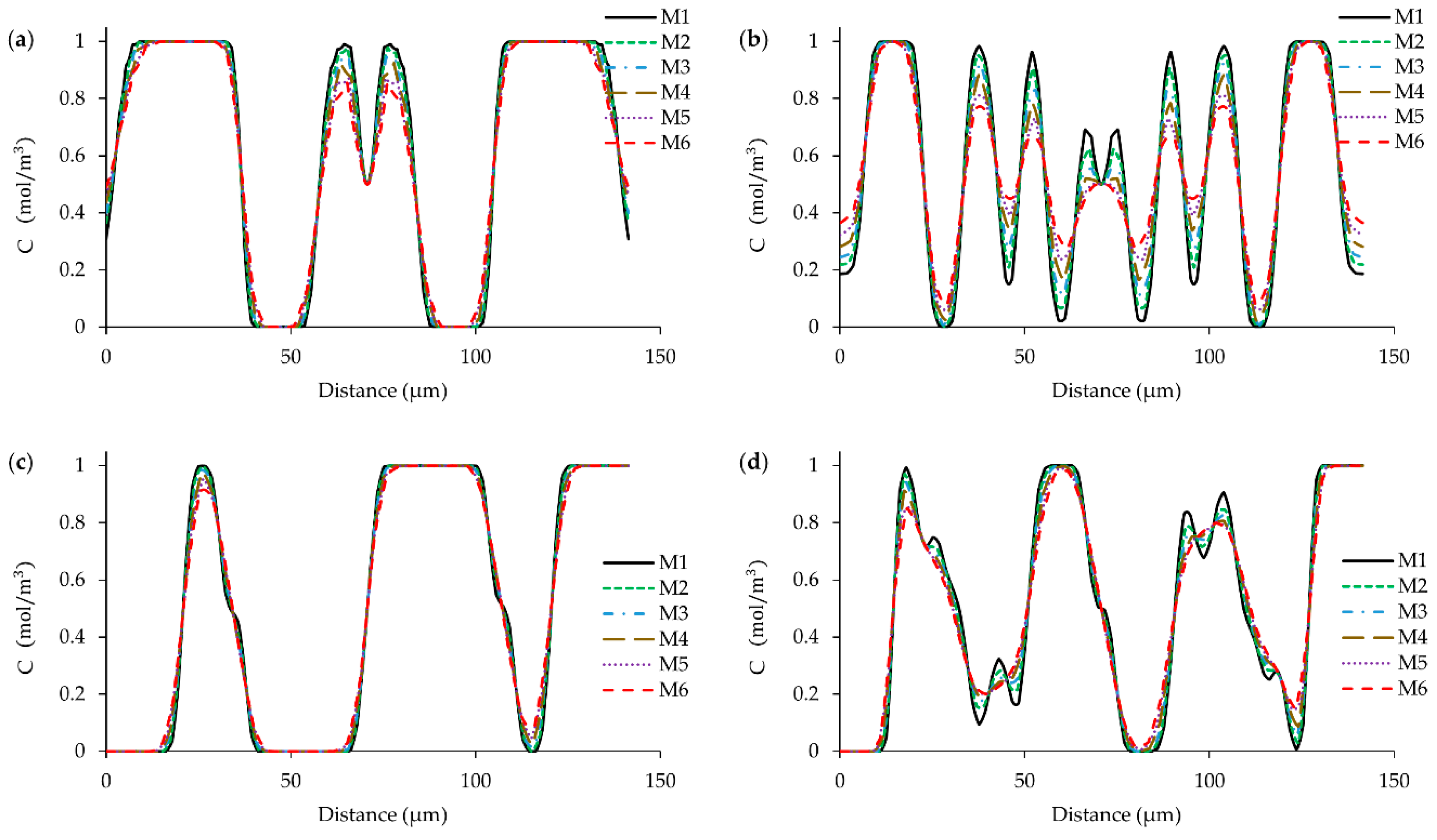

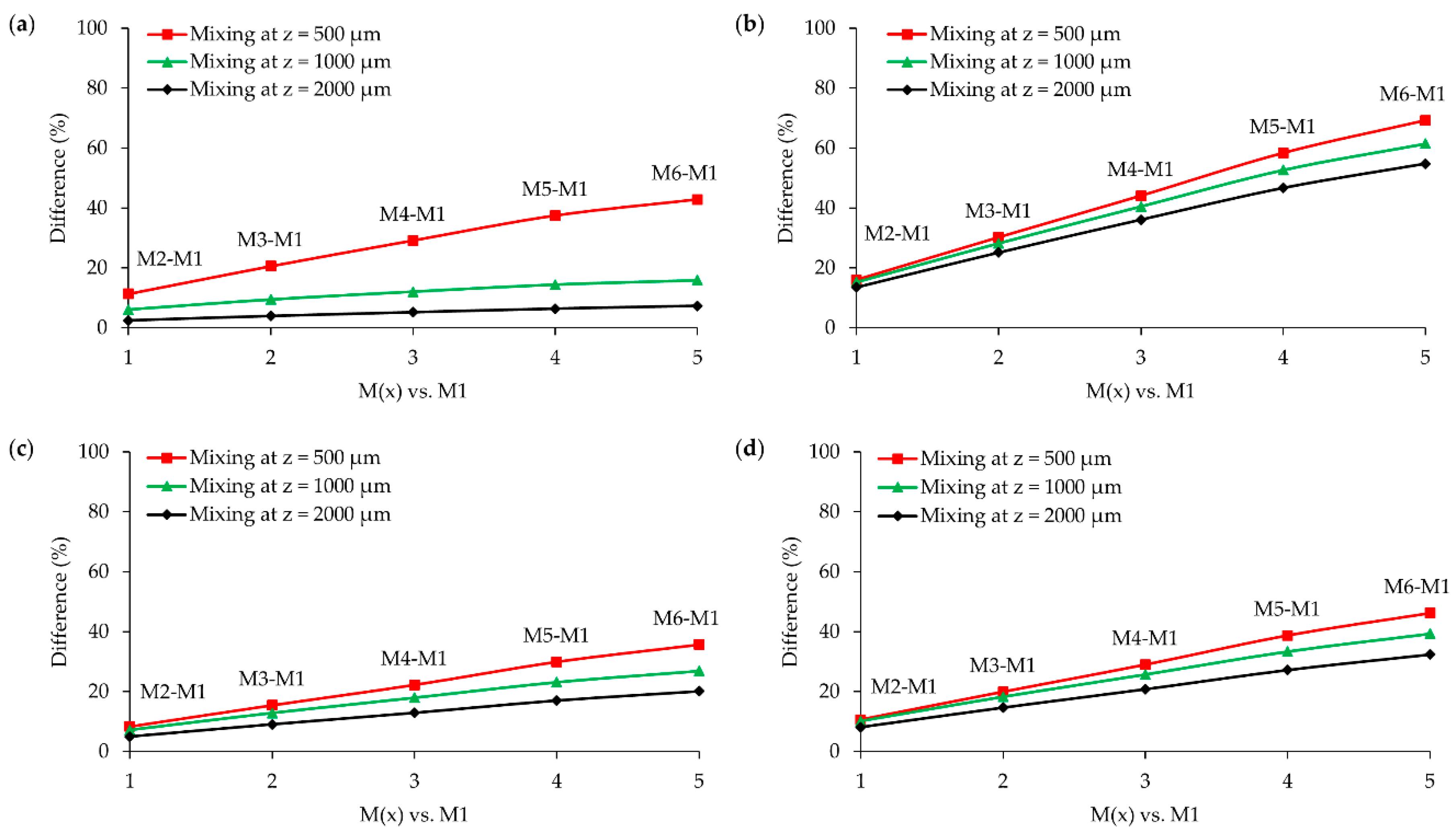

To further investigate the numerical diffusion development in the micromixers, mixing on different cross-sections between the entrance and outlet of the mixing channel were measured and graphed as shown in

Figure 8 in which “a and b” and “c and d” plots show four-inlet and two-inlet micromixer configurations and “a and c” and “b and d” plots show Re = 240 and 120 scenarios respectively. In the Re = 120 case, while mesh levels predict a similar amount of mixing values at the entrance of the mixing channel, measured mixing values are different due to developing mixing in the mixing channel. These differences between mesh levels emerge as a result of numerical diffusion during the mixing process in the mixing channel since each mesh level resolves different concentration profiles as previously shown in

Figure 6 and

Figure 7. Depending on the flow profile created and the magnitude of the swirls in the mixing channel, variation between mesh densities increases until a certain distance in the mixing channel is reached. After this point, mesh levels exhibit a mild convergent tendency. At Re = 240 scenario, however, while the two-inlet design shows a similar mixing estimation trend as observed in the Re = 120 case, the four-inlet configuration draws quite a different profile. As the variation between mixing indexes of different mesh densities increases until the

z = 500 µm in the mixing channel, after this point, the variation declines and convergence is observed at the outlet of the micromixer. Thus, it should be noted that selecting the concentration sampling points for grid studies becomes important to reveal the actual contradiction between mesh levels. Using Equation (7),

Figure 9 shows the comparison of mesh levels with the finest mesh in terms of mixing index on the

x-

y plane at different

z-distances of the mixing channel. Similarly, while “a and b” and “c and d” plots show the results for four-inlet and two-inlet micromixer designs, “a and c” and “b and d” plots represent Re = 240 and 120 scenarios respectively.

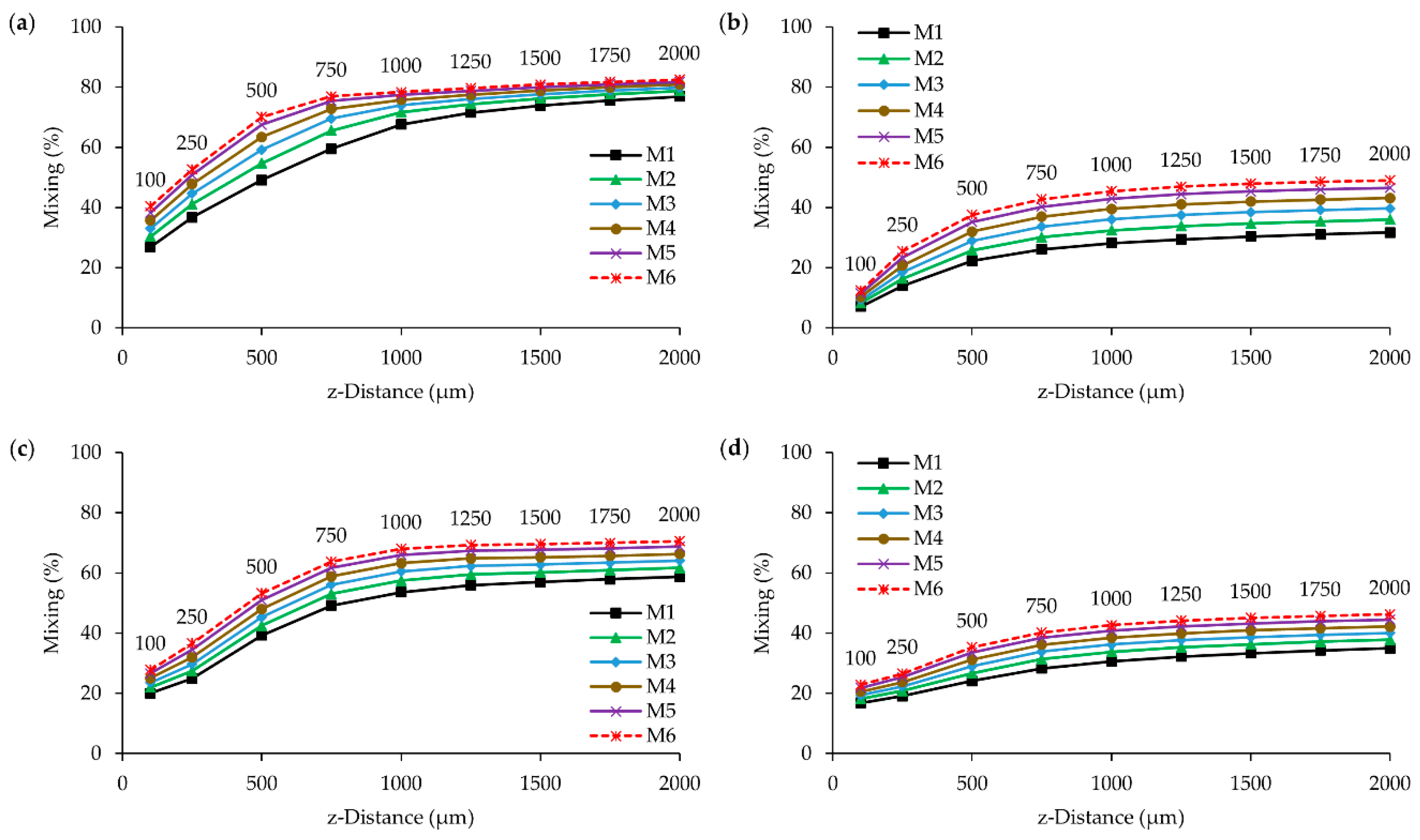

It is noticeable from

Figure 9a–d that mesh refinement significantly reduces the numerical diffusion errors in both micromixer types and flow cases. Besides, the maximum difference occurs between M6 and M1 meshes as expected and gradually diminishes with increasing mesh density until the level of M2 and M1 is reached, which is around 10% for all cases. On the other hand, the mixing outcome obtained from separate locations results in different trends for mesh comparisons. Namely, discrepancies between meshes with the finest level reach the maximum at the

z = 500 µm sampling point and beyond this point it starts decreasing across the mixing channel. While the two-inlet design reacts to mesh refinement and sampling regions similarly for both Re = 240 and 120 flow scenarios as shown in

Figure 9c,d, four-inlet configuration shows quite low differences beyond the

z = 500 µm sampling point at Re = 240 as shown in

Figure 9a. Therefore, for this case, the use of the outlet mixing index in the mesh study may seriously mislead the evaluation of numerical diffusion because, as the difference between M6 and M1 is around 7% at the outlet, this is 42% at the

z = 500 µm point. This contradiction is also observed in all other cases at relatively lower magnitudes. The discrepancy observed at different points and the converging tendency of different mesh resolutions across the mixing channel require an explanation.

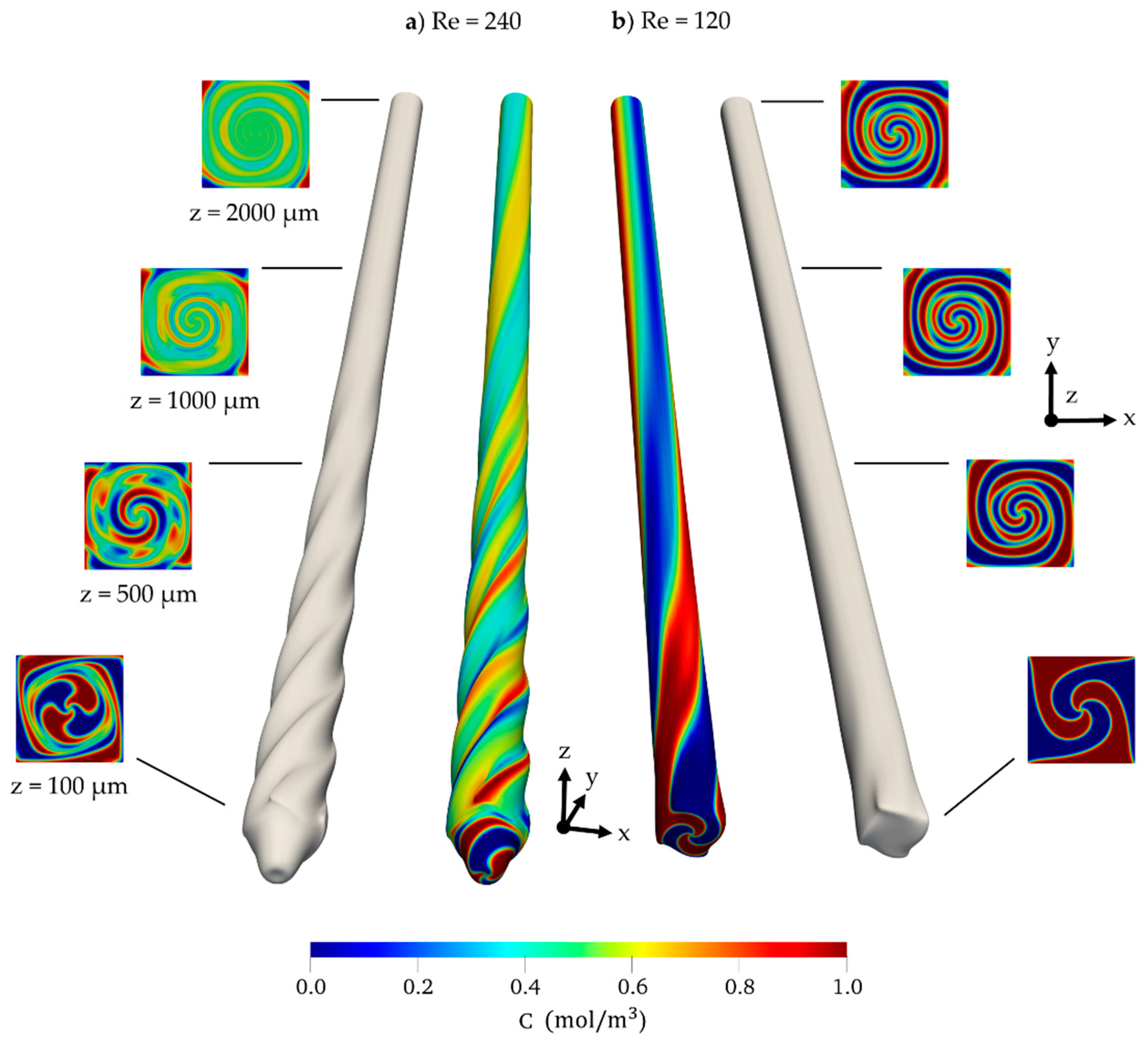

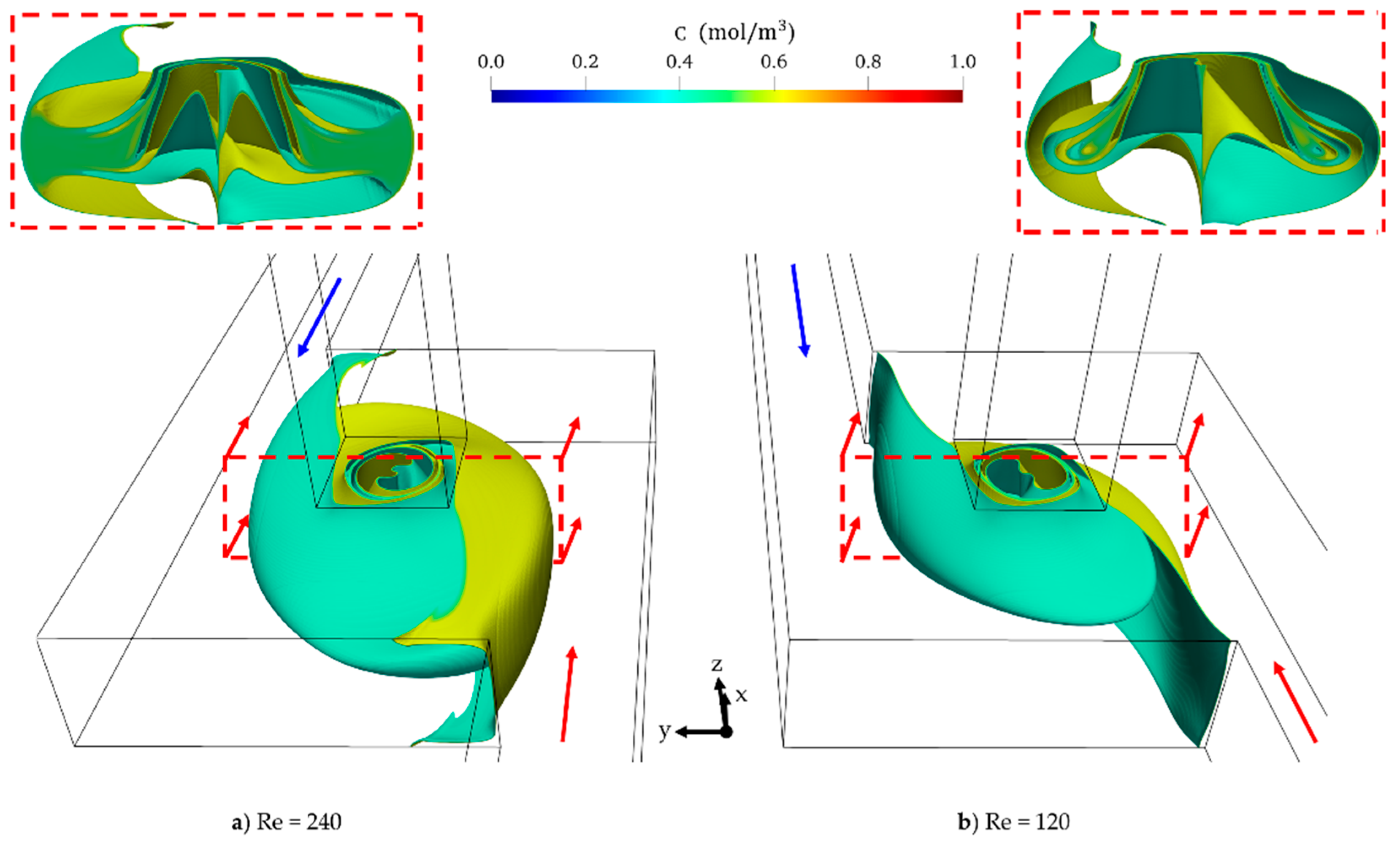

Figure 10a,b shows the fluid flow and scalar transport in the mixing channel of the four-inlet design for both Re = 240 and 120 scenarios respectively. As can be seen in

Figure 10a, the swirl motion starts at the entrance of the mixing channel and continues strongly until

z = 500 µm. After this point, the intensity of the generated swirl is dampened and fluid pairs flow along the mixing channel with a relatively smoother rotational movement. Hence, the maximum amount of numerical diffusion is produced between

z = 100 µm and 500 µm depending on the grid resolution used and after this point the numerical errors generated are averaged and transported in the mixing channel as mixing.

The same explanation is also true for Re = 120 scenario, but the difference between results at

z = 500 µm and beyond is less than that of Re = 240 case. This is mainly as a result of a relatively lower flow velocity and moderate swirl profile generated in the mixing channel as shown in

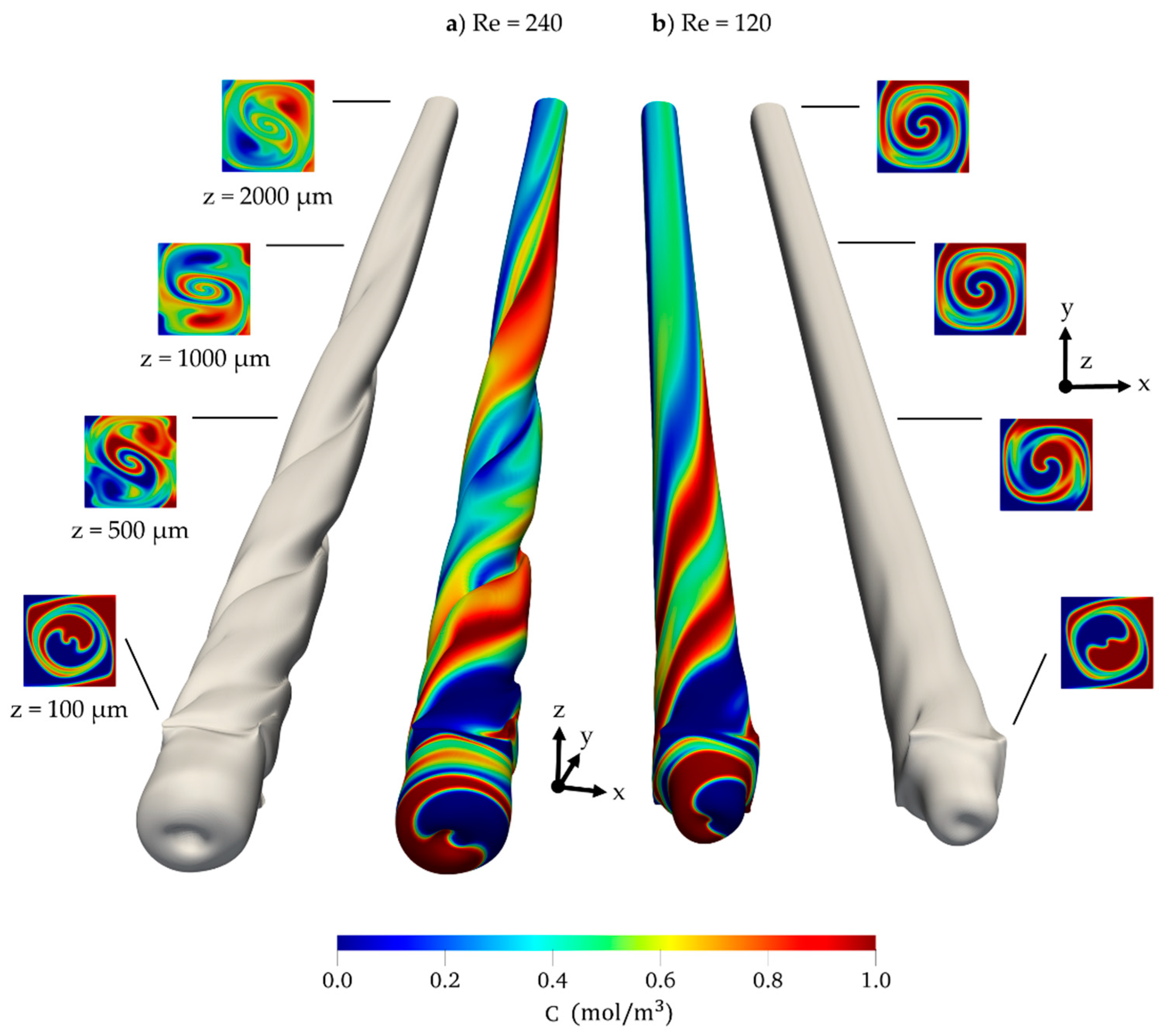

Figure 10b. In the case of the two-inlet design, while the flow profile does not exhibit an even swirl form at Re = 240, the swirl profile generated is similar to the four-inlet design at Re = 120 as shown in

Figure 11a,b respectively. Nevertheless, the maximum difference between mesh resolutions and the finest mesh is still observed at

z = 500 µm for both flow scenarios. As discussed in

Section 3, scalar transport with two-inlet injection is expected to produce less numerical diffusion since this configuration will create a relatively lower rotational contact surfaces between fluids. However, when four-inlet and two-inlet design outcomes are compared qualitatively at Re = 120, this is not as projected in the 2-D test case previously. Although fluids in the four-inlet micromixer create more contact surfaces at Re = 120 as shown in

Figure 10b, the green regions in this figure are lower than that of the two-inlet solution as displayed in

Figure 11b. If both figures are compared with respect to cross-sections at the entrance of the mixing channel (

z = 100 µm), the two-inlet design shows much more green regions as opposed to four-inlet’s distinct blue and red color pattern. This is because the uniform velocity magnitude applied from each inlet of the two-inlet micromixer is two times higher than that of the four-inlet in order to provide Re = 240 and 120 flow conditions. Therefore, the flow regimes generated in the mixing boxes of both micromixer configurations are different as displayed in

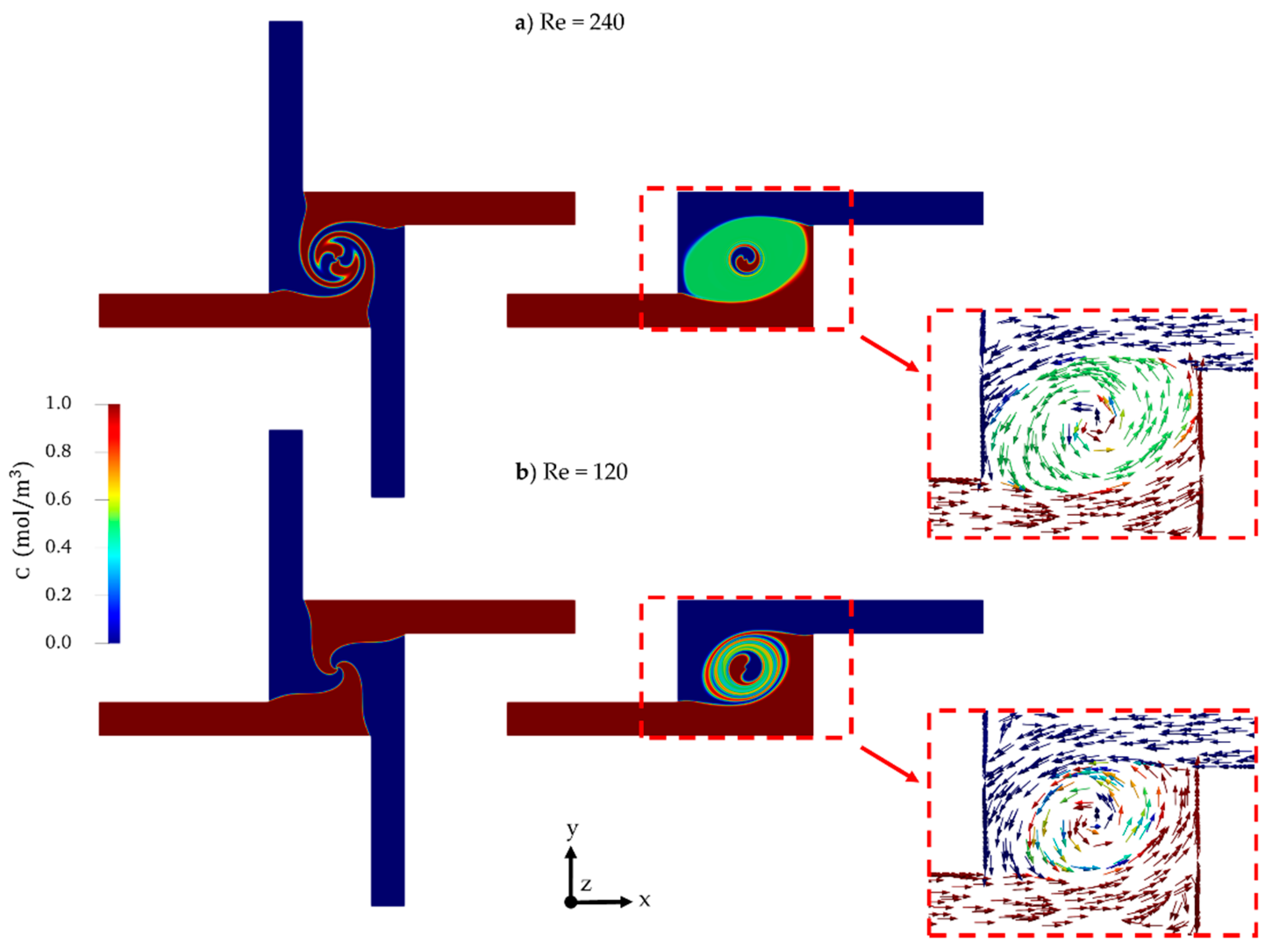

Figure 12a,b, which shows the central plane of the mixing box at

z = 50 µm for both micromixer types and flow cases. It is clear from the figure that in contrast to the balanced four-sided fluid injection structure and lower inlet velocity of the four-inlet design, higher flow rates and two-sided inlet orientation generate a strong vortex inside the mixing box of the two-inlet micromixer for both flow conditions.

In addition, the strong vortex inside the mixing box creates two different swirls at the entrance of the mixing channel as one is at the center of the channel and the other one is around this central swirl as shown on different cross-sections of

Figure 11a. It is obvious that while the green areas, which show a fully mixed state, on cross-sections at

z = 100 µm are generated at the beginning of the mixing channel of the four-inlet micromixer, these green regions appear in-between two swirls and are carried from the mixing box of the two-inlet design as shown in

Figure 10 and

Figure 11 respectively. This difference may also be seen when the images in

Figure 10,

Figure 11 and

Figure 12 are compared. As a result of higher inlet velocities in the two-inlet design, fluid bodies coming from both inlets encapsulate each other several times by rotating around the center of the mixing box as shown in

Figure 13a,b. Besides, the size of the vortex profile created inside the mixing box exceeds the dimensions of the mixing box exit, at which the finest mesh elements are used as displayed in

Figure 4. Hence, a higher average Pe

Δ number around the exit section and repeated mesh-flow disorientation inside the large vortex cause a drastic increase of numerical diffusion generation in the mixing box. In view of these results, false diffusion production is mainly controlled by the mixing channel and mixing box in four-inlet and two-inlet micromixer designs respectively. Accordingly, while the grid size distribution used inside the mixing box is a good strategy for a four-inlet micromixer, in the case of the two-inlet configuration, smaller mesh elements need to be positioned across the mixing box in order to control the amount of numerical diffusion produced.

5.2. Quantification and Analysis of Numerical Diffusion

In swirl-induced passive micromixers, higher flow rate requirement to create a swirling motion and very low diffusion constants inevitably lead to high Pe numbers. As it is shown in this study, the numerical solution of high Pe transport systems is quite challenging in terms of controlling the production of numerical diffusion throughout the system. Although the total mesh element numbers used are around 16.4 and 10 million for mesh levels M1 and M2 respectively, still, the discrepancy between these mesh levels is around 10% in terms of measured mixing. The effect of change in the numerical diffusion magnitude beyond M1 density is still not known due to the high computational cost. Considering the complexity of numerical diffusion analysis, Liu [

10] developed a method to quantify the average numerical diffusion in steady flow systems utilizing the scalar gradient in numerical solutions and found that when average Pe

Δ = 50 is used, the numerical solution generated a negligible amount of numerical diffusion in the tested microchannel mixer. This method was later used in References [

9,

11] to analyze false diffusion in different micromixer types. In this technique, the combined effects of molecular diffusion (

DM) and numerical diffusion (

DN) are defined as effective diffusivity (

DEffective) as formulated in Equation (8). Therefore, Equation (8) makes it possible to evaluate numerical diffusion by setting the molecular diffusion constant equal to zero. In this case, effective diffusivity gives the average false diffusion amount in the numerical solution. On the other hand, if numerical diffusivity is zero in a system, effective diffusivity will be equal to the prescribed molecular diffusivity in the system. Effective diffusivity is calculated using a set of equations which may be found in the referenced articles in detail.

Table 3 shows the computed numerical diffusivity (when

DM = 0) and effective diffusivity (when

DM = 3 × 10

−10 m

2/s) constants from the numerical simulations of all micromixer designs, flow conditions, and mesh densities. First, it should be noted that numerical diffusion constants obtained show the unphysical diffusivity in the system for the designed micromixer types, flow conditions, mesh levels, and numerical scheme employed. Notably, estimated numerical and effective diffusivity constants are very close to each other for all scenarios, which indicates that the effect of molecular diffusion is severely masked by false diffusion. In both micromixer designs, effective diffusion constants calculated are one and two orders of magnitude higher than given molecular diffusion constant for Re = 120 and 240 flow cases respectively. Besides, increasing the mesh density also reduced the numerical diffusion generated for all tested scenarios. The two-inlet design simulations showed higher numerical diffusivities than that of the four-inlet micromixer structure especially in the Re = 240 flow scenario. This is obviously due to the strong vortex formation inside the mixing box as explained in the previous section. Nevertheless, all flow and mesh scenarios tested for both micromixer designs failed to recover the given molecular diffusion constants and exposed high numerical diffusion errors.

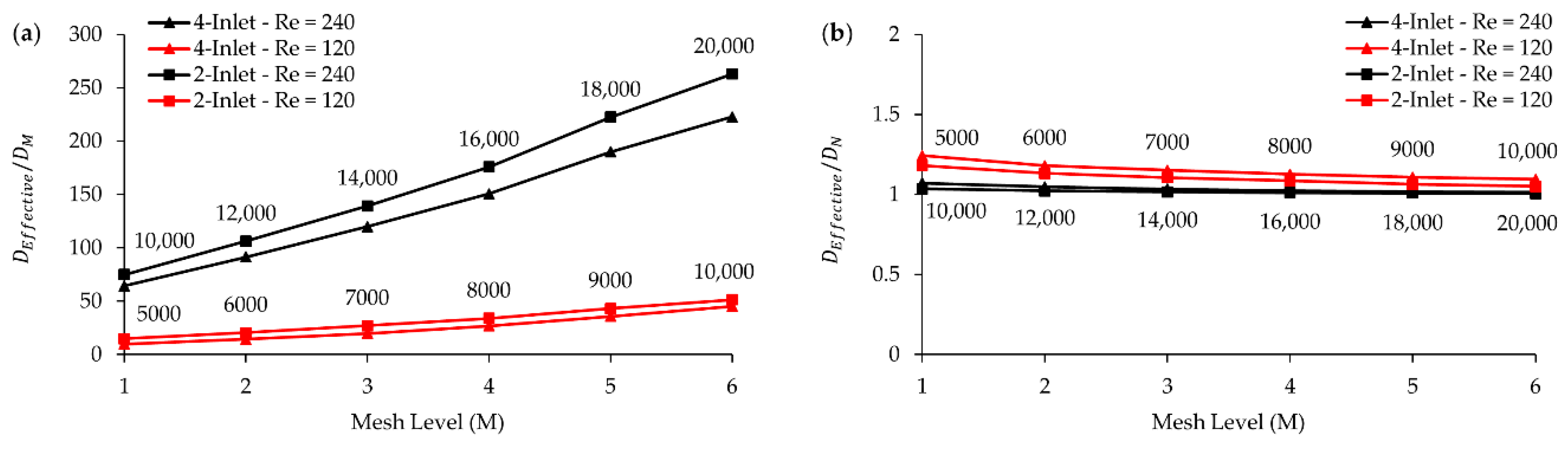

For a better presentation of

Table 3, effective diffusivities were normalized by a molecular diffusion constant (

DM = 3 × 10

−10 m

2/s) and numerical diffusivities for each mesh level as shown in

Figure 14a,b, respectively, in which the numbers above the trendlines represent the average Pe

Δ numbers for different mesh levels. The ratio of

DEffective/

DM describes the performance of the scalar transport simulation in terms of false diffusion production in the solution. Namely, if the amount of numerical diffusion generated approaches to zero, the molecular diffusivity used in simulations will be recovered by the computed effective diffusivity and, therefore, the ratio will be approaching to 1.

Figure 14a clearly shows that the false diffusion amount produced in the Re = 120 scenario is significantly lower than that of Re = 240 for both micromixer types.

The two-inlet and four-inlet designs show a variation at same average Pe

Δ numbers which implies that the amount of mesh-flow misalignment inside the computational domain—hence the numerical diffusion generation tendency—is quite different in both micromixers. Accordingly, it should be noted that considering the cell Pe number alone in the control of false diffusion may yield misevaluation of the errors generated because it is obvious from

Figure 14a that the two-inlet design is prone to create more numerical diffusion than the four-inlet design in the Re = 240 flow scenario. This difference increases when coarser grid elements are used in simulations. Even for the best-case scenarios tested in this study, the predicted effective diffusivities are approximately 10 and 15 times higher than the simulated molecular diffusivity for four-inlet and two-inlet designs respectively. As mentioned earlier, the smallest average Pe

Δ number is on the order of 5000 which is a large number to control false diffusion in numerical simulations.

Similarly,

DEffective/

DN may also be used for the false diffusion evaluation as shown in

Figure 14b. In this case, when the ratio is one, the estimated effective diffusivity completely reflects the produced numerical diffusion in the simulation. When the produced false diffusion in a solution is very small, the ratio will be several orders higher than one. It is clear from the

Figure 14b that even for the minimum average Pe

Δ number, the ratio is on the order of 1.25 which indicates that effective diffusivity is still close to the numerical diffusivity in the solution. When the two plots are compared, there is a consistency between computed effective diffusivities and numerical diffusion constants, which indicates that the employed method in Reference [

10] coherently characterizes and quantifies the average numerical diffusion generation in a scalar transport simulation.

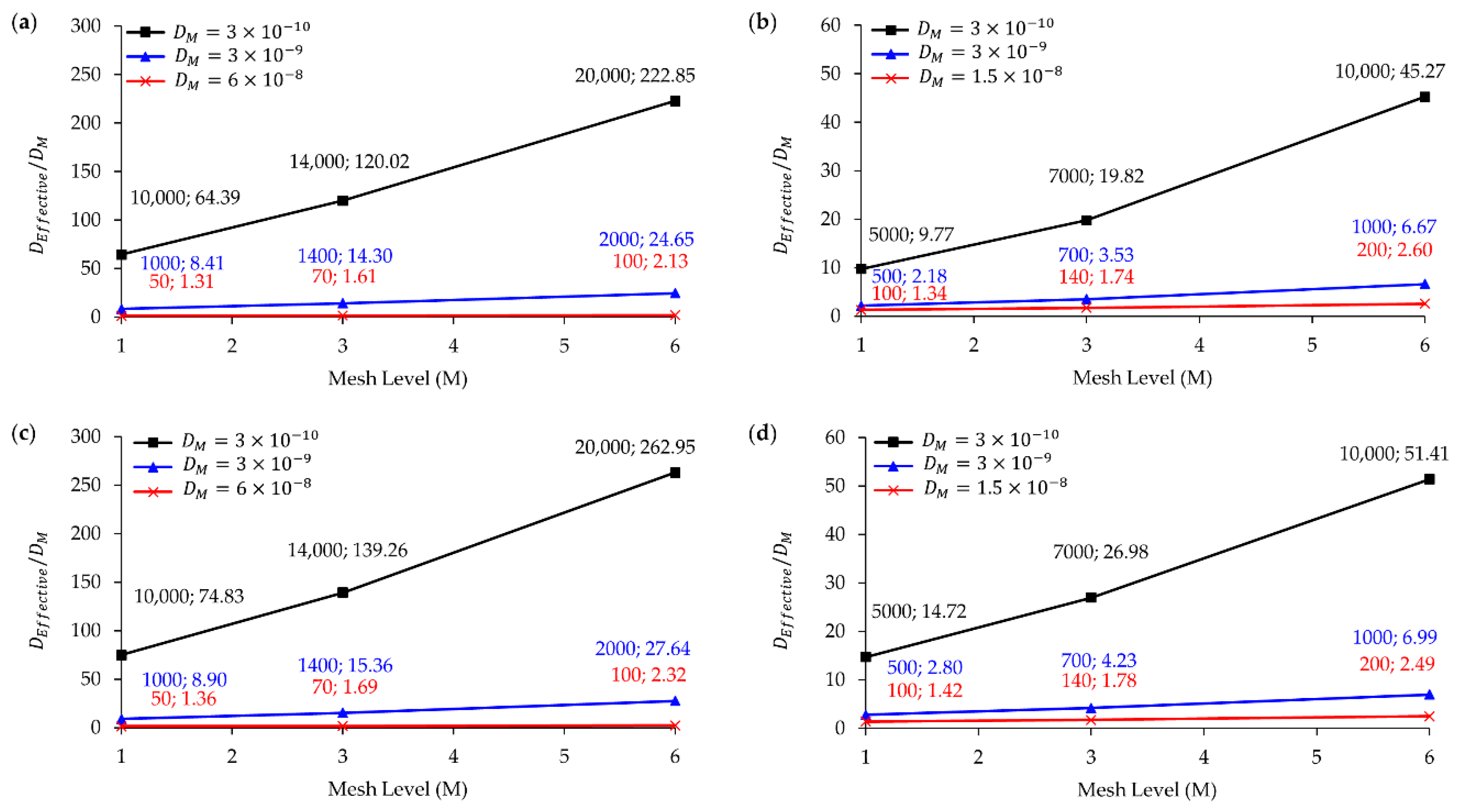

According to the outcome given in

Table 3, the tested scenarios cannot reflect the physical effects of employed molecular diffusion constants as a result of quite high average Pe

Δ numbers, thus mixing values in

Figure 8 are still masked by the numerical diffusion. Therefore, to observe the effects of smaller average Pe

Δ numbers, higher molecular diffusion constants were tested for mesh levels M1, M3, and M6, keeping the same flow conditions. Initially, the original molecular diffusion constants used (i.e.,

DM = 3 × 10

−10 m

2/s) were increased 10 times for both flow conditions by which average Pe

Δ numbers were reduced 10 times. Later, considering the false diffusion production tendency of flow scenarios, 200 and 50 times higher molecular diffusivities were tested for Re = 240 and 120 cases respectively. The molecular diffusion constants used and the corresponding average Pe

Δ numbers may be found in

Table 2. As displayed in

Figure 15, which shows the change of the

DEffective/

DM ratio with respect to three different mesh levels and molecular diffusion constants, using a smaller average Pe

Δ number increases the recovery of the simulated molecular diffusion constant for both micromixer types and flow conditions. For instance, in the Re = 240 scenario, reducing the average Pe

Δ number from 10,000 to 1000 by using the

DM = 3 × 10

−9 m

2/s, decreased the ratio from 64 to 8 for the four-inlet design and 75 to 9 for the two-inlet design at mesh level M1 as shown in

Figure 15a,c respectively. However, the observed ratios 8 and 9 at the M1 level are still very high to reflect the physical effects of the diffusion constant employed. The numerical diffusion generated at this level is on the order of 10

−8 for both micromixer types as given in

Table 3, which implies that numerical diffusion is one order of magnitude higher than the molecular diffusion constant and still dominates the physical diffusivity in the numerical solution. When

DM = 6 × 10

−8 m

2/s for the same flow scenario, the ratio reduces to 1.31 and 1.36 points at the M1 mesh level (Pe

Δ = 50) for the four-inlet and two-inlet micromixers respectively. In this case, the negative effects of numerical diffusion are mostly suppressed due to a tolerable average Pe

Δ number and, therefore, the ratio gets closer to one, which means that physical diffusivity is mostly reflected in simulations. For other mesh levels M3 (Pe

Δ = 70) and M6 (Pe

Δ = 100), the

DEffective/

DM ratio is “1.61 and 2.13” and “1.69 and 2.32” for the four-inlet and two-inlet micromixer designs respectively. Thus, when the average Pe

Δ is 100, the recovered diffusivity from the numerical solution is more than two times higher than the molecular diffusion constant used in the Re = 240 flow scenario. When Re = 120, the ratios at M1 level (Pe

Δ = 500,

DM = 3 × 10

−9 m

2/s) are 2.18 and 2.80 for the four-inlet and two-inlet configurations as shown in

Figure 15b,d respectively. In addition, in the case of

DM = 1.5 × 10

−8 m

2/s, which results in an average cell Peclet number 100 at M1 grid level, the ratios obtained for the four-inlet and two-inlet micromixers are 1.34 and 1.42 respectively. If these ratios are compared with that of the Re = 240 scenario at the same mesh density M1, it is obvious that the physical diffusion recovery performance of both flow scenarios is almost equal while the Pe

Δ is two times higher in the Re = 120 scenario. Thus, when Re = 120, numerical simulations can tolerate higher average grid Peclet numbers in terms of numerical diffusion production, because swirling flow at Re = 120 is typically less when complicated to that of Re = 240 for both micromixer types. Consequently, while numerical diffusion generation is mostly determined by the magnitude of the cell Peclet number, the flow pattern created is similarly important since mesh-flow alignment of fluid pairs is controlled by the flow pattern.

In Reference [

10], it is advised that when mixing is completed at very early stages in the micromixer, including the entire micromixer domain in effective diffusivity computation may result a substantially averaged and imprecise value. In this research, the maximum mixing index is observed at the outlet of the four-inlet micromixer in the Re = 240 flow scenario when

DM = 6 × 10

−8 m

2/s is used. The evolution of the mixing index values on

x-y planes at

z = 500, 1000, and 2000 µm in the mixing channel are 73, 95, and 98% respectively for the above case at the M1 level. Therefore, the effective diffusivity values computed mostly reflect the actual diffusivities in the computational domain since mixing is still developing through the outlet channel. In addition, concentration distributions at

z = 500 µm (Line-II in

Figure 3) for mesh levels M1, M3, and M6 are shown in

Figure 16a,b for molecular diffusivities 3 × 10

−10 and 6 × 10

−8 m

2/s respectively. As shown in

Figure 16b, indeed, variations between mesh levels are significantly decreased because the above mesh densities resolved the transport domain at Pe

Δ numbers 50, 70, and 100 respectively. This figure visually reflects the computed

DEffective/

DM ratios. For example, when the ratios are 64 and 223 for mesh densities M1 and M6, respectively, the observed discrepancy is high between these two levels as plotted in

Figure 16a. However, when the ratios drop to 1.36 and 2.32 by means of a higher molecular diffusion constant,

Figure 16b shows that similar concentration trends are obtained for M1 and M6 mesh densities.

In this research, it was shown that characterization and quantification of false diffusion errors in swirl-induced mixing systems are critical to analyze the mixing performance and report physically reliable results. It should be noted that although numerical diffusion effects on physical mixing were analyzed in swirl-based mixing systems, the findings in this research are also valid for high Pe scalar transport systems in which secondary flows are dominant. In grid-based numerical techniques, diminishing the numerical diffusion errors to negligible levels at high Pe scenarios is possible when mesh density is increased. However, in specific cases, such as swirling flows, where grid-flow orientation is continuously violated, this approach may become unfeasible due to an extremely increased computational cost. For example, to render an average Pe

Δ number 10 in the mixing channel for the Re = 240 and

DM = 3 × 10

−10 m

2/s scenario, approximately 1 × 10

15 hexahedron elements need to be used in the computational domain. Such a mesh density is obviously far beyond the computational capacity of today’s workstations. In this case, alternative approaches to the grid-based methods should be considered. In the current literature, several researchers proposed and practiced specialized particle-based numerical techniques for high Peclet transport systems, as can be seen in References [

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34] and the references therein. The algorithms developed in these studies present different computational advances which are beyond the scope of this study. However, these methods become prominent for elimination of the adverse effects of numerical diffusion errors at high Pe cases and less computational power requirement when compared to the conventional grid-based numerical methods.