1. Introduction

In recent years, the rapid advancement of global industrialization and the continuous growth of automobile ownership have exacerbated environmental pollution while accelerating the depletion of fossil fuel resources. Conventional internal combustion engine vehicles (ICEVs), powered primarily by gasoline and diesel, emit substantial quantities of carbon dioxide, nitrogen oxides and particulate matter (PM) [

1]. These pollutants intensify the greenhouse effect, deteriorate air quality, and impose mounting pressure on energy supply security and sustainable development. Moreover, the heavy reliance of ICEVs on fossil fuels has created structural challenges for the global energy system and posed significant threats to ecological stability [

2]. Against this backdrop, electric vehicles (EVs) have emerged as a promising alternative to conventional ICEVs and have become a focal point of research and industrial development. EVs operate predominantly on electricity and achieve zero tailpipe emissions during use, offering a significant advantage in mitigating urban air pollution [

3]. Their inherently higher energy utilization efficiency further enhances their environmental and economic benefits. As the penetration of renewable energy sources such as solar, wind, and hydropower increases in modern power systems, EVs can also serve as flexible distributed energy storage units, enabling efficient conversion, storage, and redeployment of renewable electricity. This capability not only supports large-scale integration of renewable energy but also enhances grid resilience through vehicle-to-grid (V2G) technologies [

4]. Driven by technological innovation and the maturation of industrial supply chains, the EV market has expanded rapidly across major regions, including China, Europe, and the United States. Electrified transportation is now widely recognized as a key pathway toward achieving sustainable mobility and reducing carbon emissions.

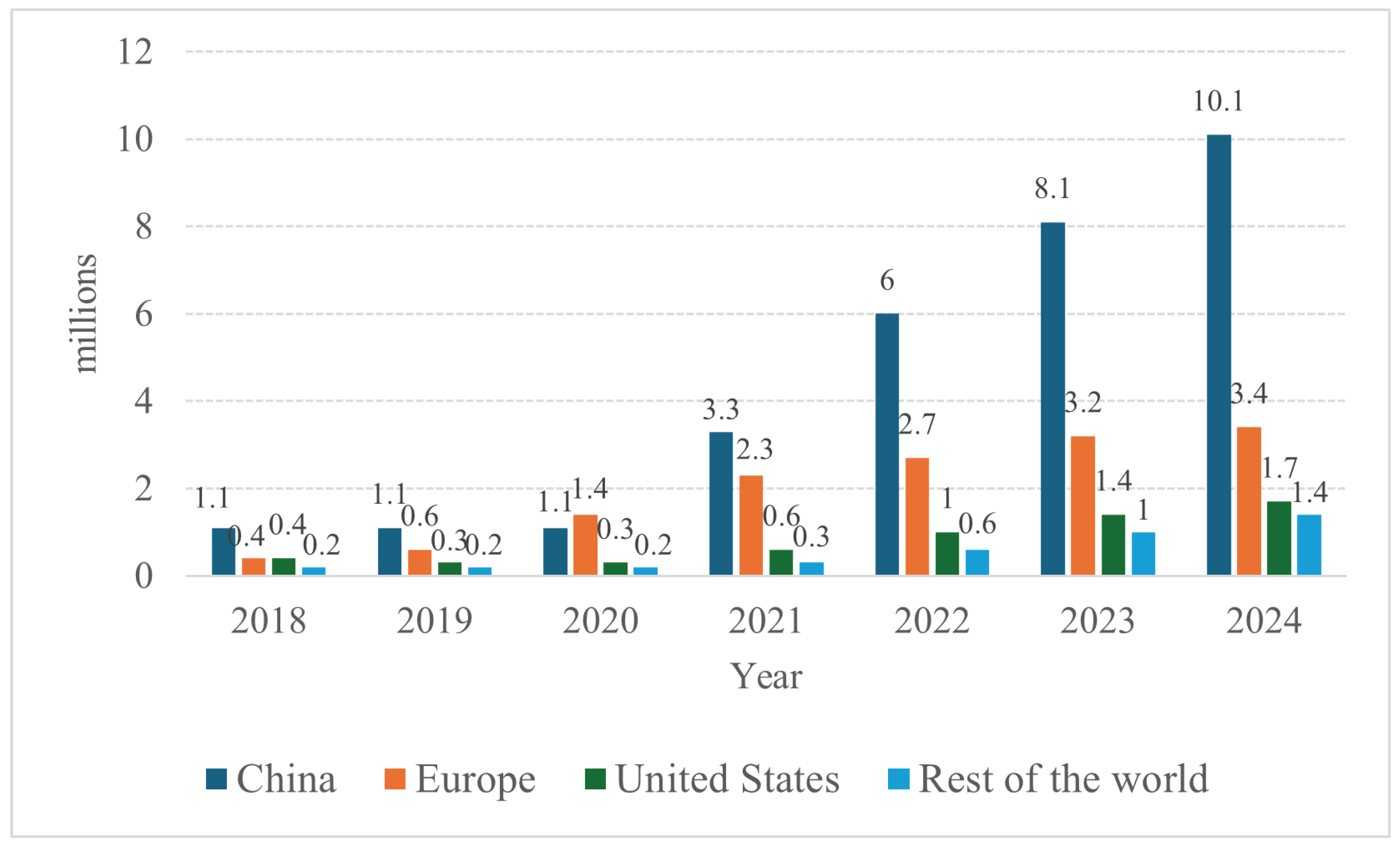

Figure 1 presents EV sales from 2018 to 2024, highlighting the strong and sustained growth of global EV adoption and underscoring its substantial future potential [

5].

As EVs are increasingly embraced worldwide to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and dependence on fossil fuels, charging technology has become one of the most critical factors influencing their widespread adoption. The performance, safety, economic viability, and user convenience of charging systems directly affect consumer acceptance and the pace of EV infrastructure deployment [

6]. High-efficiency, reliable charging solutions are essential not only for practical EV usability but also for the coordinated integration of renewable energy and smart grid operations. Consequently, the design and optimization of EV charging systems have become a central research focus across academia and industry. Currently, wired charging remains the primary method of energy replenishment for EVs. This approach delivers power through physical conductive connections between a charging station and the vehicle’s battery. Wired charging offers several advantages, including high power transfer capability, relatively low cost, and strong compatibility with existing grid infrastructure [

7]. Depending on the type of current used, wired charging can be categorized into AC charging and DC fast charging. AC charging requires an on-board charger (OBC) to convert AC to DC, which increases vehicle weight and limits charging speed [

8]. In contrast, DC fast charging supplies DC power directly from an external unit, enabling significantly higher charging power and reduced charging time [

9]. Despite its maturity, wired charging presents several inherent drawbacks: manual plug-in operations reduce convenience; safety risks arise in humid or corrosive environments; and mechanical connectors can wear over time. These limitations restrict charging automation and flexibility, encouraging the development of alternative approaches such as WPT [

10]. Another major challenge associated with wired charging is the lack of global standardization in charging interfaces and communication protocols. Different regions have adopted distinct standards reflecting local grid structures and industrial ecosystems, resulting in poor interoperability between EVs and charging infrastructure worldwide. For example, North America primarily employs the SAE J1772 (Type 1) interface for AC charging and CCS1 for DC charging [

11]; Europe utilizes the IEC 62196 Type 2 (Mennekes) connector with CCS2 [

12]; Japan relies on the CHAdeMO standard for DC fast charging [

13]; and China has established its own GB/T system for AC and DC charging [

14].

Table 1 summarizes the prevalent EV charging plug types across different regions. It is evident that each region has developed unique connector designs, communication protocols, and voltage/current specifications. These discrepancies in connector design, communication protocol, and voltage levels hinder cross-regional compatibility. As a result, multinational automakers must design multiple charging interfaces and control systems for different markets, increasing manufacturing complexity and cost. Such fragmentation in charging standards has led to significant compatibility issues and associated consequences.

WPT offers a promising solution by enabling contactless power delivery through magnetic fields, microwaves, or laser beams. WPT systems are broadly categorized into short-range and long-range transmission [

15]. Short-range WPT particularly magnetic-resonant coupling, has become the dominant approach due to its high efficiency and suitability for EV charging, although its performance is sensitive to the relative alignment of transmitting and receiving units. Long-range approaches, such as microwave or laser-based WPT, provide greater spatial freedom and are particularly attractive for powering moving or distant targets. However, these technologies currently face challenges such as low transmission efficiency and high system complexity. Among the various WPT methods, MCR-WPT has emerged as the most promising and widely adopted technology for EV wireless charging applications. MCR-WPT systems can be designed to accommodate misalignments and varying air gaps between coils, making them well-suited for dynamic charging scenarios where vehicles may not be perfectly positioned over charging pads. To ensure interoperability and safety across different manufacturers and regions, several standards have been established for EV wireless charging systems. Notably, the SAE J2954 standard [

16] defines key parameters such as operating frequency, coil geometries, power levels, and alignment tolerances [

17].

Table 2 summarizes some of the critical design constraints specified by these standards for EV wireless power transfer systems.

To facilitate the development of efficient, reliable, and practical EV wireless charging systems, this paper provides a comprehensive review of WPT systems. A systemtic review framework is proposed in

Figure 2 to clearly illustrate the literature search and review process. This framework clarifies the overall workflow, including literature identification, and classification. Specifically, the reviewed studies are systematically categorized according to key technical dimensions of MCR-WPT systems, including coupling mechanisms, resonant compensation networks, power converter architectures, and control strategies.

The main contributions of this paper are summarized as follows:

A comprehensive overview of WPT technologies for EV charging is presented, covering both near-field and far-field approaches. The advantages, limitations, and application scenarios of each technology are discussed to provide a holistic understanding of the field.

An in-depth analysis of MCR-WPT systems is conducted, focusing on key enabling technologies including magnetic coupling mechanisms, compensation network topologies, power converter architectures, and control strategies. The interdependencies among these aspects are highlighted to illustrate their collective impact on system performance.

Emerging trends and future research directions in EV wireless charging are identified, emphasizing the need for hybrid WPT architectures, adaptive compensation designs, and robust control algorithms to achieve high-power, long-distance, and misalignment-resilient wireless charging solutions.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 provides an overview of WPT technologies for EV charging.

Section 3 delves into the magnetic coupling mechanisms employed in MCR-WPT systems.

Section 4 reviews various resonant compensation network topologies and their design considerations. The power converter architecture and control methods are analyzed in

Section 5 and

Section 6, respectively. A comprehensive discussion of future research directions is presented in

Section 7. Finally, a brief conclusion is provided in

Section 8.

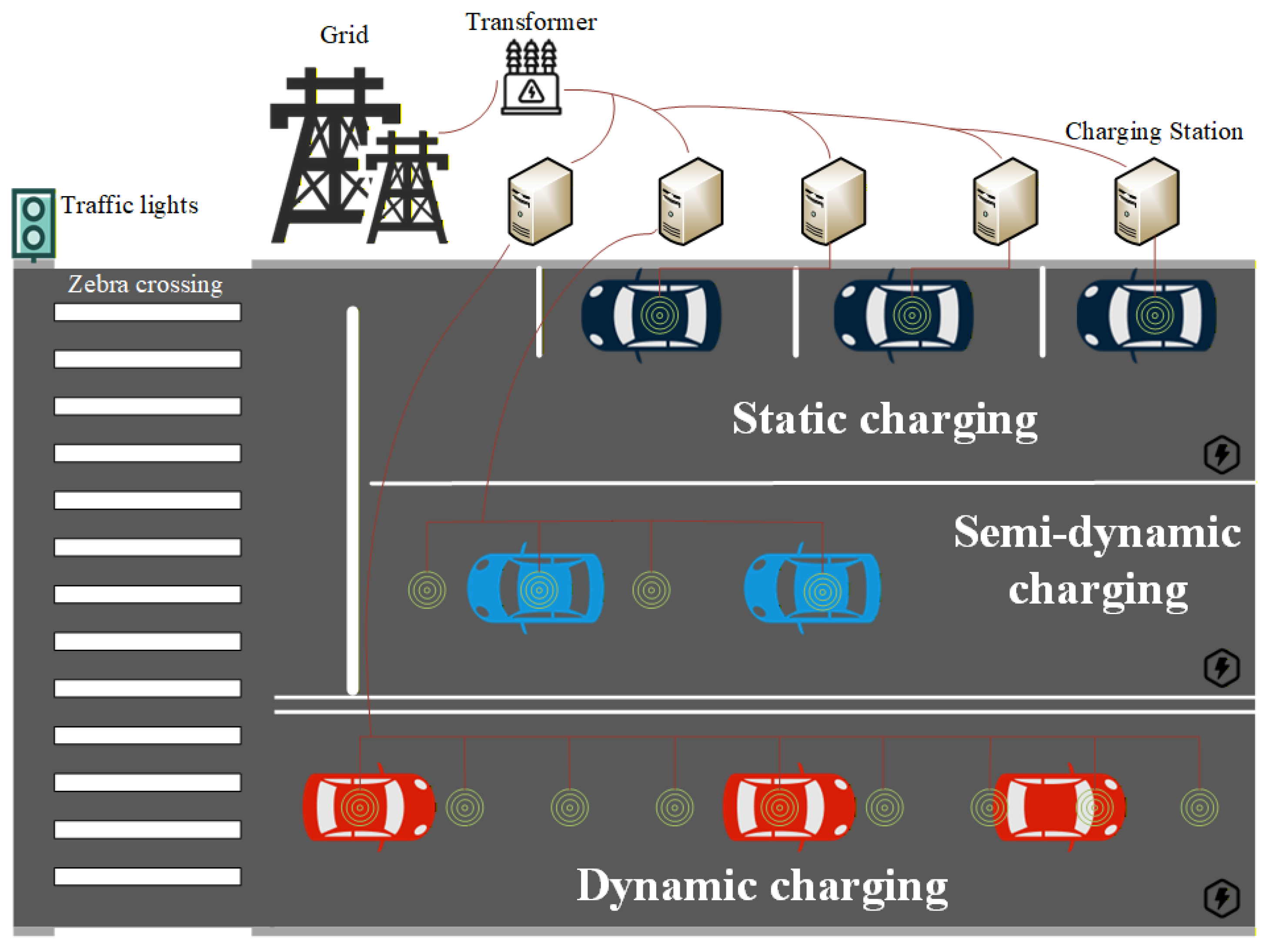

2. Wireless Power Transfer Technologies for EV

WPT is an advanced energy transmission technology that utilizes spatial media such as electromagnetic fields, magnetic fields, or light waves, to enable contactless energy transfer from a transmitter to a receiver. This technology eliminates the need for mechanical connectors or manual operation, offering advantages such as enhanced safety, higher automation, and improved environmental adaptability. As a result, WPT is widely regarded as a promising and intelligent solution for the future energy replenishment of electric vehicles (EVs). By employing WPT, EVs can be charged without physical contact, effectively avoiding issues associated with conventional plug-in charging systems, including connector wear, operation inconvenience, and poor reliability under harsh environmental conditions. Based on the vehicle’s motion state and charging scenario, EV wireless charging technologies can generally be categorized into three modes: Static Wireless Charging, Dynamic Wireless Charging (DWCS), and Semi-Dynamic Wireless Charging, as illustrated in

Figure 3.

In static wireless charging, the vehicle remains stationary during charging, typically in environments such as home garages, office parking lots, or public charging facilities. In this mode, the transmitting coil installed on the ground and the receiving coil mounted beneath the vehicle are well aligned and fixed in position, resulting in a large coupling coefficient between the coils. This enables high transmission efficiency and stable power delivery. Owing to its structural simplicity, mature control strategies, and proven reliability, static WPT represents the most commercially mature and widely implemented form of EV wireless charging to date. In contrast, dynamic wireless charging enables vehicles to replenish energy while in motion, using a series of transmitting coils embedded along designated roads or highways. As the vehicle moves, it continuously receives energy from these coils, effectively extending driving range and improving the utilization of charging infrastructure. This mode can also reduce downtime and improve overall transportation energy efficiency. However, during dynamic charging, misalignment between coils and variations in coupling coefficients caused by vehicle movement often lead to fluctuations in output power and reduced energy transfer efficiency [

18]. Therefore, robust control algorithms and adaptive compensation network designs are essential to maintain stability and high efficiency under varying conditions. Semi-dynamic wireless charging serves as an intermediate solution between static and dynamic modes. It is typically applied in scenarios where vehicles make short stops, such as at traffic lights, bus stops, or intersections [

19]. Although the charging duration is short, the frequency of charging events is high, imposing stringent requirements on system response speed and power density. Consequently, semi-dynamic charging has attracted increasing attention in urban public transportation systems and shared mobility platforms, where high-throughput, short-duration charging is desirable.

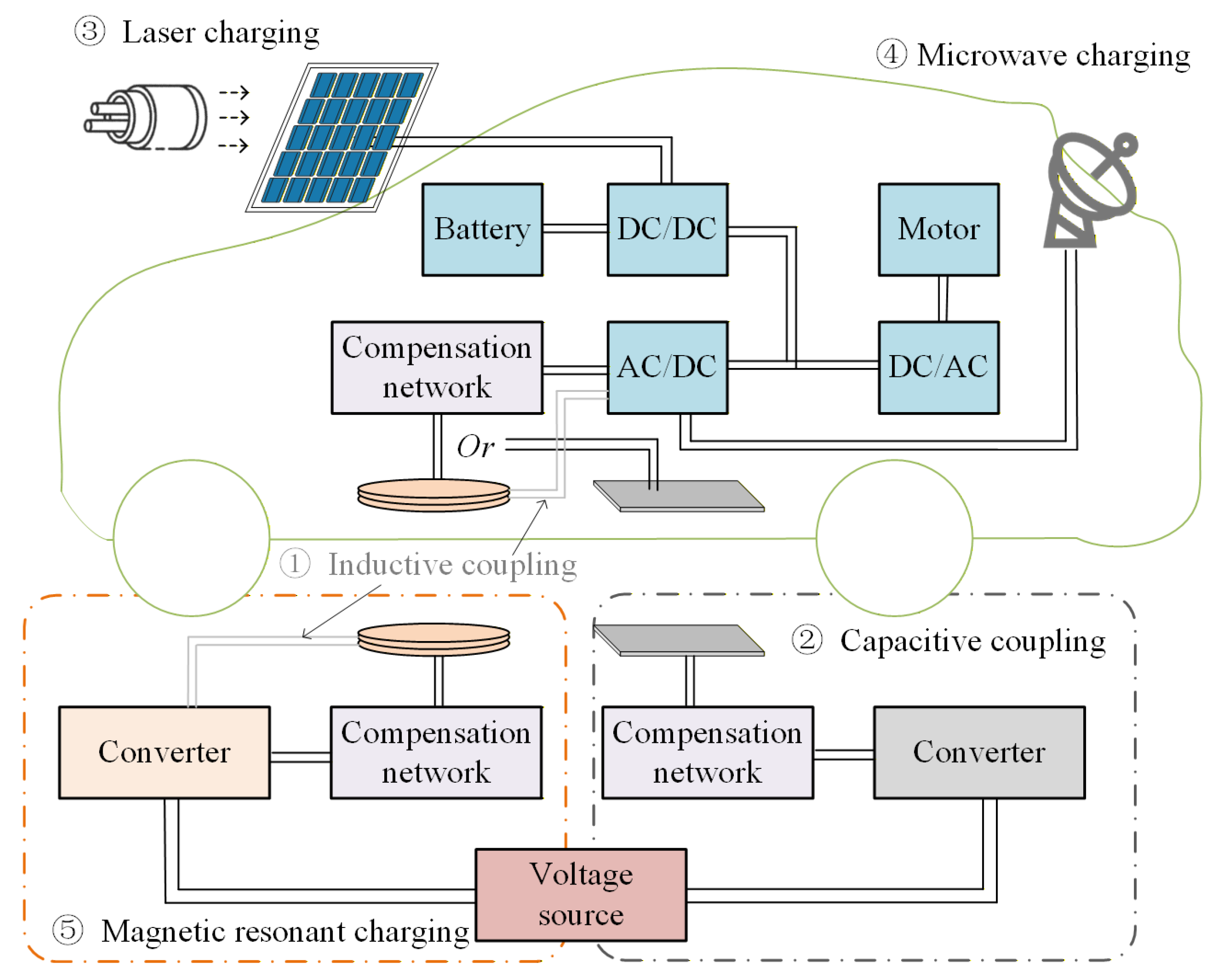

From the perspective of energy transfer mechanisms, EV wireless charging technologies can be broadly divided into near-field WPT and far-field WPT. Near-field WPT technologies primarily include IPT, CPT, and MCRWPT systems. The above common used WPT technologies for EV charging are shown in

Figure 4.

2.1. Inductive Power Transfer Technology

Inductive Power Transfer (IPT) is fundamentally based on Faraday’s law of electromagnetic induction. Its core principle is that when an alternating current (AC) flows through the transmitting coil, a time-varying magnetic field is generated in the surrounding space. The receiving coil, located within the magnetic field region, experiences a change in magnetic flux, which induces an electromotive force (EMF) within the conductor, thereby enabling contactless energy transfer from the transmitter to the receiver [

20]. This process can be regarded as a magnetic-field-coupled energy conversion, where electrical energy is first converted into magnetic energy through the transmitting coil and then reconverted into electrical energy at the receiving side.

Figure 5 shows the diagram of inductive power transfer for EV charging, which can be divided into transmitter and receiver parts. The transmitter part mainly consists of a DC power source, an inverter, a compensation network, and a transmitting coil. The receiver part is composed of the receiving coil, compensation network, rectifier, filter, and load (i.e., EV battery). During operation, the DC power source provides input energy that is converted into high-frequency AC power by the inverter. This AC power is then transmitted to the receiving coil through magnetic coupling. The receiving coil captures the magnetic field and induces an AC voltage, which is subsequently rectified and filtered to provide stable DC power for charging the EV battery. In addition, the mutual inductance

M between the transmitting and receiving coils is a critical parameter that directly affects the power transfer efficiency and system performance, which can be calculated as the following equation:

where

and

are the self-inductances of the transmitting and receiving coils, respectively, and

k is the coupling coefficient, which depends on the relative position and alignment of the coils. A higher coupling coefficient indicates better magnetic coupling and improved power transfer efficiency.

Benefiting from its simple structure, high safety, and excellent electrical insulation, IPT technology has been widely applied in various fields such as unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), mobile robots, and underwater autonomous vehicles. For EVs, IPT is particularly suitable for static charging scenarios, including home garages, parking lots, and bus terminals [

21,

22]. In these applications, the transmitting and receiving coils are placed in close proximity (typically less than 20 cm) and maintain a relatively fixed alignment, resulting in a high coupling coefficient. Consequently, IPT systems can achieve high transmission efficiency and moderate-to-high power output, making them well-suited for medium-power charging applications. However, IPT also faces several technical challenges that limit its further deployment. The most critical issue lies in its strong dependence on coil alignment. To enhance the misalignment tolerance of inductive power transfer (IPT) systems, existing studies have mainly focused on coupler structure optimization and resonant compensation design. On the coupler side, advanced pad geometries such as Double-D (DD), Double-D Quadrature (DDQ), and tripolar structures have been widely investigated. These couplers can maintain relatively stable mutual inductance under lateral displacement, thereby improving system robustness against misalignment. However, such designs typically increase manufacturing complexity, material usage, and overall cost.

In parallel, higher-order and hybrid compensation networks have been proposed to extend system adaptability under varying coupling conditions. Representative examples include LCL-S, LCCC-LCC, and other hybrid topologies. Beyond passive design, active control strategies, such as frequency tuning, phase control, and variable reactive components, have also been explored to improve power regulation and efficiency. While these methods enhance adaptability within a given operating range, they do not fundamentally extend the effective transfer distance. Moreover, as IPT systems still rely on magnetic cores to enhance coupling, challenges related to system size, weight, and cost remain, limiting their scalability toward long-distance or large-area wireless charging applications.

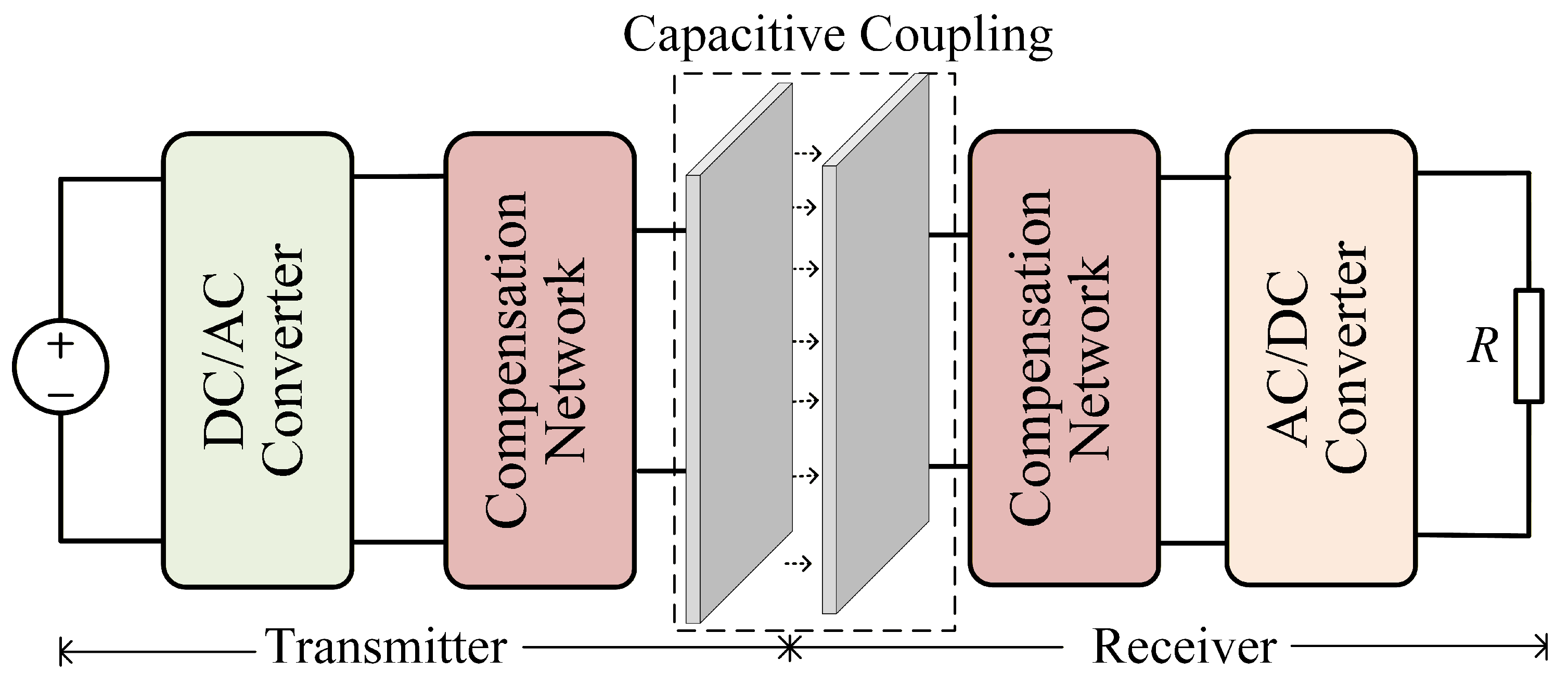

2.2. Capacitive Power Transfer Technology

Capacitive Power Transfer (CPT) is a non-contact power transfer technology based on electric field coupling. As shown in

Figure 6, the CPT system consists of two main parts: a transmitter and a receiver. The transmitter comprises a high-frequency inverter and a compensation network, which convert DC power into high-frequency AC. The receiver, on the other hand, includes a compensation network, a rectifier, and a load, responsible for receiving AC energy and delivering a stable DC output. Energy transfer between the transmitter and receiver occurs through capacitive couplers, which form the transmission channel.

To improve power transfer efficiency and reduce the equivalent impedance, CPT systems typically employ resonant compensation networks such as LC, LCL, or LCLC topologies [

23]. Addressing system stability, ref. [

24] developed an innovative split-inductor matching network that absorbs parasitic capacitances into the resonant tank, achieving a “capacitorless matching” design. Compared with the IPT system, which relies on magnetic-field coupling, CPT systems utilize alternating electric fields and thus eliminate the need for expensive ferrite materials and Litz-wire coils. This results in lower system cost, reduced weight, and improved suitability for high-frequency operation. The geometric flexibility of capacitive plates further expands CPT applicability to portable electronics, consumer devices, UAV power delivery, and automotive auxiliary systems. Nevertheless, CPT efficiency is highly sensitive to lateral or angular misalignment of the metal plates. To address this challenge, ref. [

25] developed a reconfigurable capacitive coupler with adaptive transmitting plates and lightweight receiving plates, achieving omnidirectional misalignment tolerance while maintaining 82.5% efficiency at 212.1 W. Building on this concept, ref. [

26] introduced a single-capacitor CPT architecture that exploits a UAV landing platform as an intermediate relay plate, enabling stable output voltage under arbitrary planar displacement and full 360° rotation. Despite these advancements, CPT technology continues to face several fundamental challenges. First, electric-field coupling is highly sensitive to variations in dielectric properties and plate spacing; fluctuations in relative position or air gap can cause significant changes in capacitance, adversely affecting system stability. Second, high-power CPT systems are constrained by dielectric breakdown limits and parasitic discharge risks, imposing stringent requirements on insulation design and operational safety. Finally, CPT systems generally exhibit shorter effective transmission distances than magnetic coupling, limiting their suitability for long-distance or dynamic charging applications. Consequently, CPT systems are currently unsuitable for dynamic wireless charging.

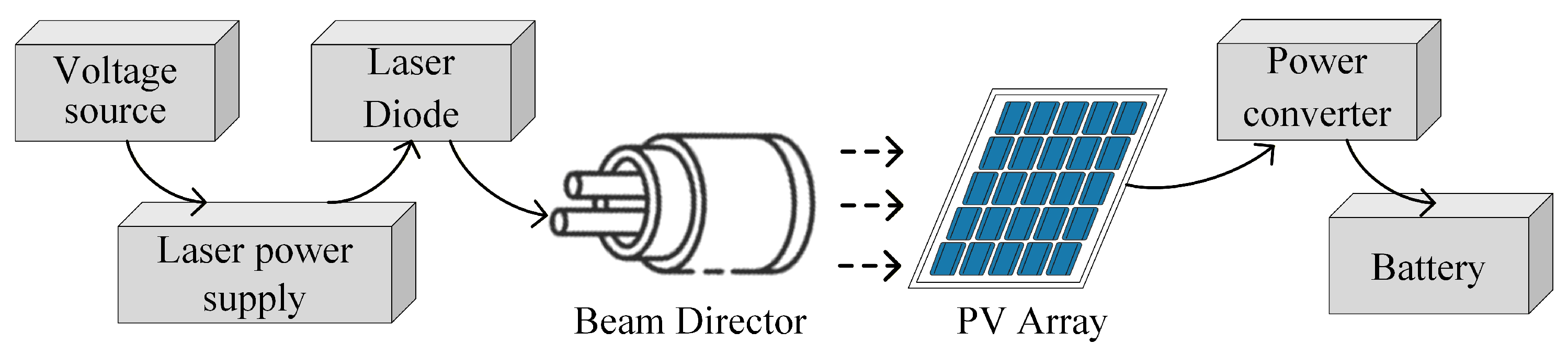

2.3. Laser Power Transfer Technology

Laser Power Transfer (LPT) has emerged as a promising far-field wireless power delivery technology, particularly suited for long-distance and high-directionality energy transmission scenarios. Unlike near-field magnetic coupling techniques such as IPT or CPT, LPT converts electrical energy into highly collimated optical radiation and delivers power through a free-space optical channel [

27]. A typical LPT system consists of a laser transmitter, a beam propagation and alignment module, and a photovoltaic (PV)-based receiver, shown in

Figure 7.

The transmitter generates a monochromatic and highly directional laser beam using a laser diode driven by a high-frequency power supply, while optical tracking and beam-steering mechanisms maintain spatial alignment between the transmitter and receiver. At the receiving side, a PV cell converts the incident laser into electrical energy, followed by rectification and power-conditioning circuits that provide usable DC output. LPT offers several unique advantages—such as kilometer-level transmission distance, high power density, and excellent beam directionality—which motivate its exploration for applications such as low-orbit satellites [

28]. Significant research efforts have been devoted to enhancing the efficiency, stability, and feasibility of Laser WPT through advancements in laser–matter interaction understanding, device optimization, and novel beam control technologies. Ref. [

29] proposed a fully optical space-charge measurement system based on nanosecond pulsed laser excitation and ellipsometric detection, achieving a signal-to-noise ratio of 38.02 dB and 14 μm spatial resolution. Such characterization tools provide critical insights into the transient charge behavior of insulating materials under high-energy excitation. Similarly, ref. [

30] investigated carbon plasma dynamics generated by nanosecond laser pulses and demonstrated that ionic charge states increase with laser energy density, reaching a maximum charge state. Complementary work by [

31] revealed that incorporating arc plasma into laser–matter interaction enhances free electron energy and significantly improves plasma penetration, offering a new route for increasing optical-to-plasma energy conversion efficiency in hybrid laser systems.

Despite the rapid technological progress, LPT still faces several practical limitations, especially in EV charging applications. System performance is highly sensitive to alignment accuracy, environmental disturbances (such as fog, rain, and dust), and optical obstructions [

32]. The photovoltaic conversion efficiency at the receiver is typically limited to 40–50% for high-power PV devices, constraining overall efficiency. Additionally, high-power laser beams introduce potential eye-safety and thermal hazards, requiring robust protection mechanisms and strict regulatory compliance.

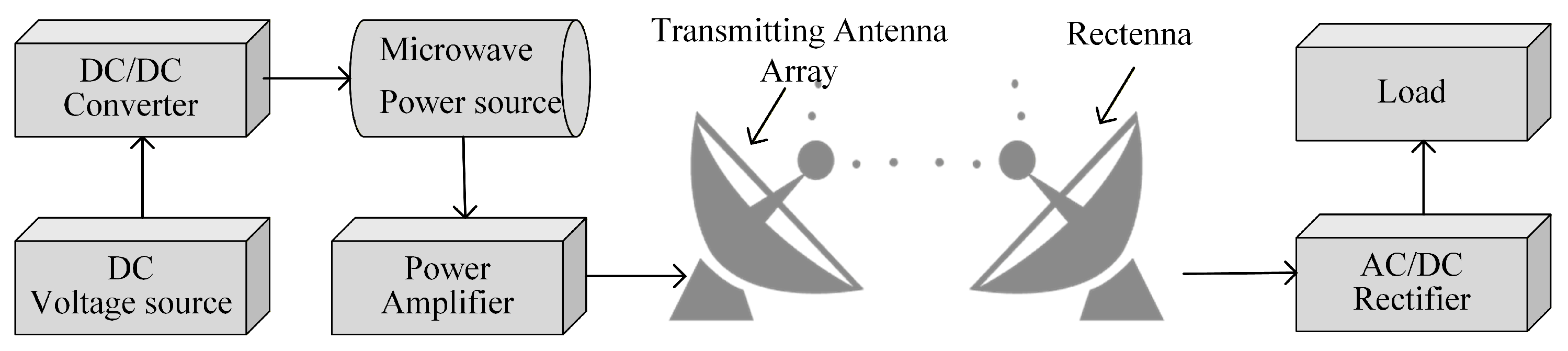

2.4. Microwave Power Transfer Technology

Microwave Wireless Power Transfer (MPT) represents a pivotal far-field WPT technology capable of delivering high power over long distances through the radiation and reception of microwave-frequency electromagnetic waves. Unlike near-field approaches such as Inductive IPT, which rely on magnetic coupling between coils, MPT operates by first converting electrical energy into radio-frequency (RF) or microwave power, then radiating this energy directionally through a high-gain transmitting antenna, and finally reconverting it into DC power at the receiver via a rectifying antenna (rectenna) [

33].

The diagram of MPT is shown in

Figure 8, which mainly consists of a microwave power source, transmitting antenna, receiving antenna (rectenna), and load. During operation, the microwave power source generates high-frequency electromagnetic waves that are transmitted through space via the transmitting antenna. The receiving antenna captures the microwave energy and converts it into AC power, which is then rectified and filtered to provide stable DC power for charging the EV battery. In recent years, MPT has been considered for mid-range electric vehicle (EV) charging, where systems using 2.45 GHz magnetrons have demonstrated 10 kW transfer over 5 m at efficiencies nearing 80% [

34]. At the device level, high-power microwave sources form the core of MPT systems, and their technological evolution has substantially expanded the potential of long-range WPT. Virtual cathode oscillators (Vircators) have attracted attention due to their simple structure and high-power capability; innovations such as the annular-reflector-based coaxial diode by [

35] and improved efficiency, while [

36] achieved 244 MW peak power and 2.75% efficiency by tuning anode–cathode spacing, and [

37] increased efficiency to 7% by introducing a cathode-wing design to suppress electron backflow. In parallel, relativistic klystron amplifiers have demonstrated gigawatt-level output and long-pulse operation, with [

38] achieving 2.2 GW and 50 dB gain in an X-band coaxial multi-beam configuration. The propagation of high-power microwaves is profoundly influenced by plasma behavior and space-charge dynamics. Complementary work by [

39] proposed a charge-balance model for irradiated dielectrics based on secondary electron emission, identifying distinct charging regimes and offering guidance for managing space-charge accumulation in high-power environments.

However, MPT still faces several practical challenges. Achieving high transmission efficiency requires large-aperture antennas, precise line-of-sight (LoS) alignment, and robust beam-tracking control systems. Environmental factors such as atmospheric attenuation, fog, rain, and multipath scattering degrade beam quality, and high-power microwave radiation introduces safety concerns that require strict shielding and monitoring protocols.

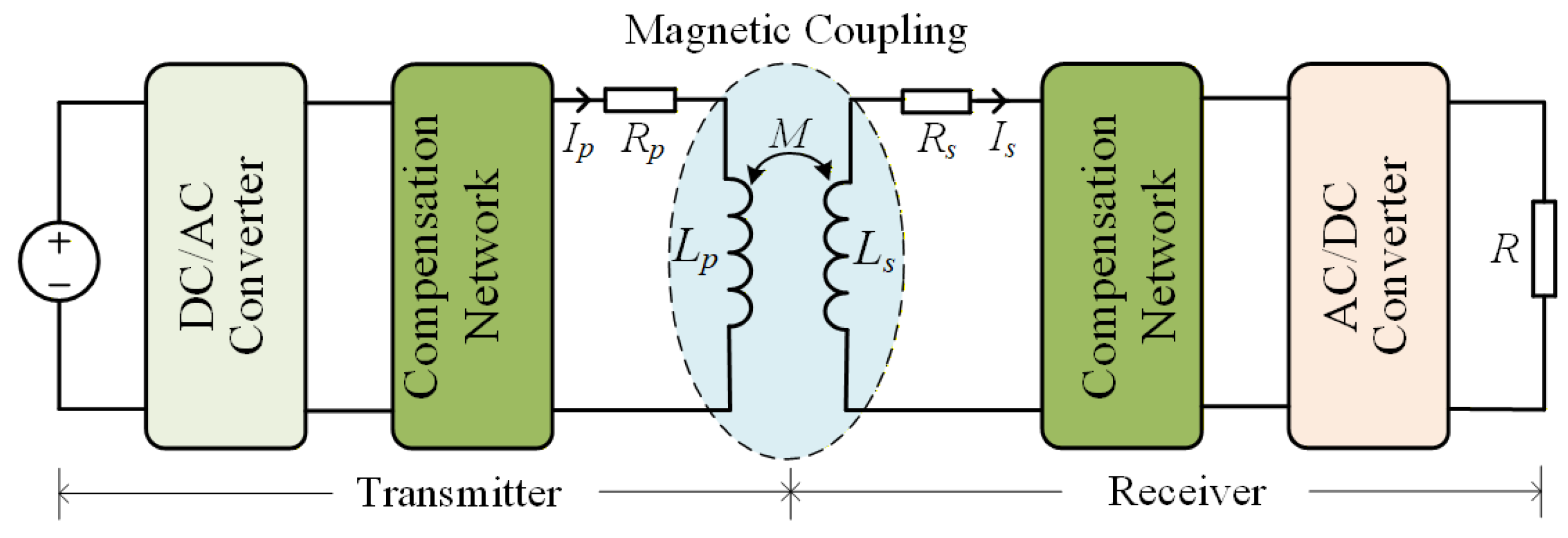

2.5. Magnetic Coupled Resonant Wireless Power Transfer Technology

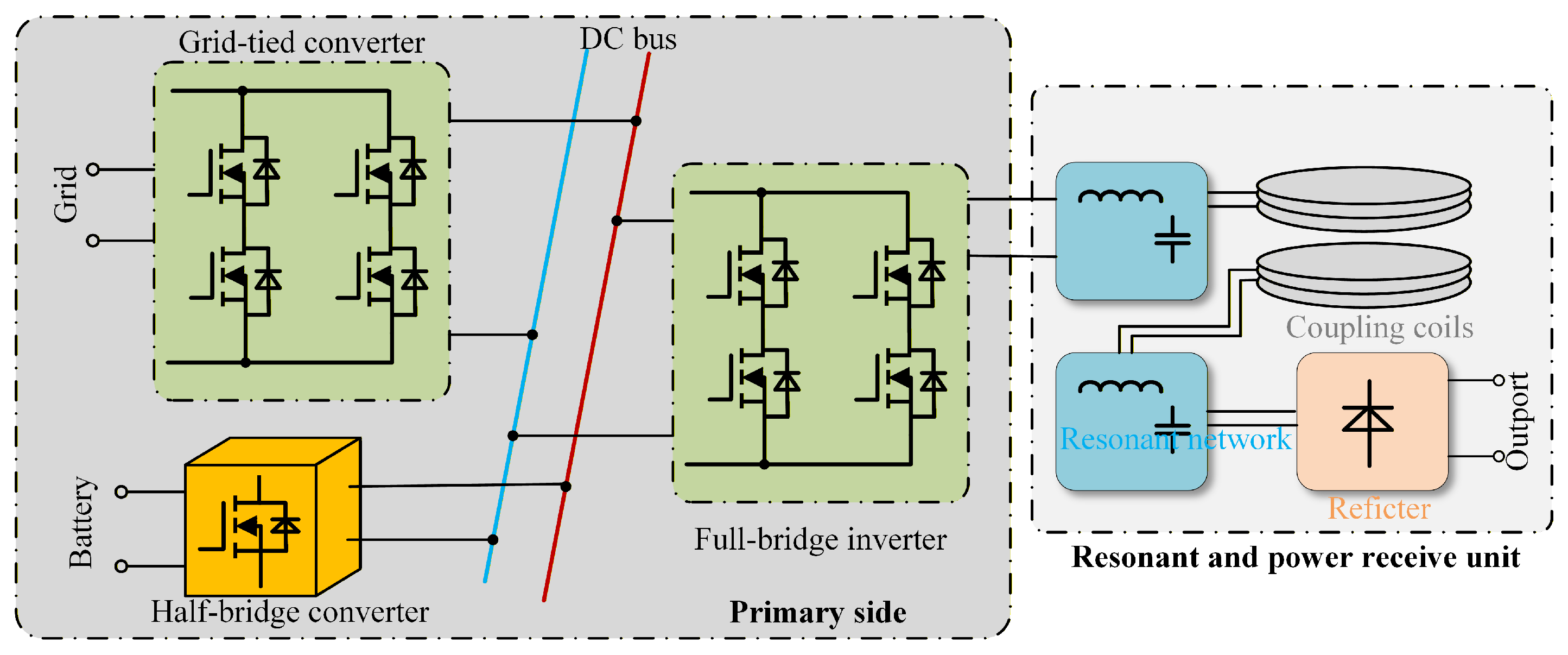

Magnetic coupled resonant wireless power transfer (MCRWPT) has been widely adopted in electric vehicles (EVs) and portable smart devices due to its high safety, convenience, and flexibility in installation. MCRWPT utilizes magnetic resonant coupling to transfer energy efficiently between transmitter and receiver coils over moderate distances. As illustrated in the

Figure 9, an MCRWPT system consists of a transmitter and a receiver. On the transmitter side, a DC/AC converter generates high-frequency alternating current that flows through the transmitting coil to produce a time-varying magnetic field. The receiving coil, tuned to resonate at the same frequency, captures the magnetic field and induces an alternating current, which is subsequently rectified and filtered to supply stable DC power to the load.

The MCRWPT system operates without a magnetic core, so the coupling between primary and secondary coils is inherently weak, typically yielding a coupling coefficient below 0.3 [

40]. This weak coupling leads to considerable reactive power and reduced transmission efficiency. To mitigate this issue, resonant compensation networks are introduced on both sides of the system to ensure resonant operation. By counteracting the reactive effects of leakage inductance, these networks significantly enhance magnetic energy exchange and maintain high efficiency even under weak-coupling conditions. Resonant compensation strategies can be classified into classical, high-order, and hybrid topologies. Classical structures (SS, SP, PS, PP) are simple and easy to implement but exhibit pronounced sensitivity to load and coupling variations [

41]. High-order networks such as LCL and LCC incorporate additional resonant tanks to broaden operational bandwidth, improve soft-switching capability, and increase robustness to parameter deviations, making them well-suited for medium- and high-power MCRWPT applications [

42]. Moreover, hybrid resonant compensation has recently gained attention for its reconfigurability and functional integration. By incorporating switch arrays, tunable capacitors, tunable inductors, or reconfigurable branches, hybrid networks dynamically adjust the resonant topology to match varying operating conditions. Such architectures enable seamless switching between constant-current (CC) and constant-voltage (CV) charging modes, accommodate battery charging profiles, and maintain high efficiency despite coil misalignment or load fluctuations. As in traditional IPT systems, the performance of MCRWPT is highly dependent on coil alignment. To enhance misalignment tolerance, researchers have developed advanced coupling structures such as double-D (DD), DDQ, and bipolar coils. These designs expand the effective magnetic field region or improve field uniformity, thereby reducing sensitivity to lateral, longitudinal, and angular displacement. Complementary techniques, including zero-crossing detection, frequency tracking, ensure stable resonant operation under dynamic coupling conditions.

With the combined advancements in compensation design, coupling structures, and adaptive control, MCRWPT can achieve high efficiency across transmission distances from several tens of centimeters to over one meter—significantly exceeding the typical range of conventional IPT. Due to its long transmission range, high efficiency, and immunity to environmental factors, MCRWPT has become a key enabling technology for UAV in-flight charging, static and dynamic EV charging, autonomous robotics, and mission-critical industrial and defense systems. These developments position MCRWPT as a foundational technology for future intelligent, high-performance, and wide-coverage wireless energy delivery infrastructures. As summarized in

Table 3, MCRWPT emerges as the most suitable candidate for dynamic wireless charging of electric vehicles (EVs). Although IPT and CPT exhibit high efficiency in short-range near-field coupling scenarios, their effective transfer distance is typically limited to only a few centimeters. This short-range requirement makes them unsuitable for dynamic EV charging, as the vertical clearance between the vehicle chassis and the embedded roadway coils prevents the strong coupling necessary for stable power transfer. On the other hand, far-field technologies such as MPT and LPT provide meter-to-kilometer-level transmission distances, but their application in road-integrated EV charging is restricted by significant safety risks, strict regulatory constraints, and low end-to-end power transfer efficiency. These characteristics make them impractical for delivering the continuous, high-power energy required by moving vehicles. In contrast, MCRWPT offers a favorable compromise between transfer distance, efficiency, and operational safety. Its resonant magnetic coupling mechanism enables efficient mid-range power transfer across the typical air gap between the vehicle and the roadway, while maintaining high system efficiency and adhering to electromagnetic exposure regulations. Therefore, MCRWPT is widely recognized as the most promising and practical technology for implementing a dynamic wireless charging infrastructure for electric vehicles. Building upon this conclusion, the subsequent sections of this paper focus exclusively on MCRWPT, providing a systematic examination of its key technical aspects, including coupling mechanisms, resonant compensation topologies, power converter configurations, and control strategies.

3. Coupling Mechanism

In MCRWPT systems, the coupling mechanism constitutes the essential component that enables non-contact energy transmission, consisting primarily of the transmitter coil, the receiver coil, and the magnetic flux coupling path that bridges them. By driving the transmitter coil with an alternating current, a time-varying magnetic field is generated and subsequently coupled through air or magnetic media to induce an electromotive force in the receiver coil. As the fundamental channel through which electromagnetic energy is transferred, the geometric structure, dimensional parameters, and spatial arrangement of the coupling mechanism exert a decisive influence on the mutual inductance, coupling coefficient, system efficiency, output stability, and tolerance to spatial misalignment. Variations in coil shape—whether circular, rectangular, double-D (DD), coaxial, or bipolar—lead to substantially different magnetic flux distributions and mutual inductance characteristics.

Among the existing designs, the single-coil structure remains the most basic and widely studied form, consisting of a closed-loop spiral coil at both the transmitter and receiver sides. Circular spiral coils and rectangular planar coils produce annular or quasi-annular magnetic flux distributions, and their coupling performance depends strongly on coil dimensions, turn number, spacing, and relative alignment, with coaxial positioning maximizing the coupling coefficient. Circular coils generally provide symmetric flux distribution and high efficiency under well-aligned static charging conditions, whereas rectangular coils offer improved space utilization when integrated into vehicles underbodies or ground charging pads. Prior studies have examined various aspects of single-coil behavior: Ref. [

43] established a particle-swarm-optimization-based relationship between coil parameters and resonant frequency for circular coils.

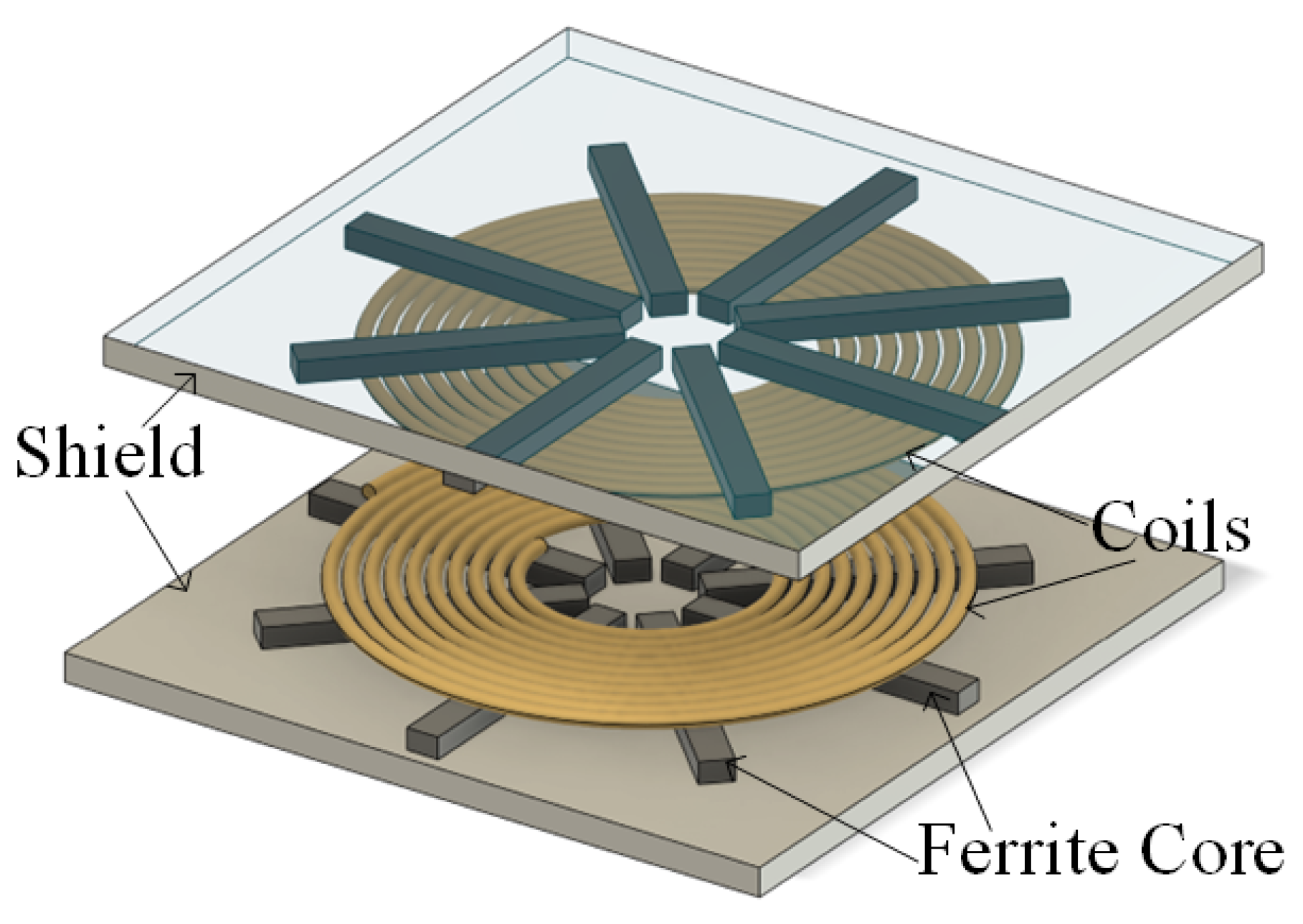

Figure 10 shows a shielded ferrite-core circular coil structure commonly used to enhance magnetic flux concentration and reduce electromagnetic interference. The effect of ferrite geometry, thickness, permeability, and loss characteristics on the coupling coefficient and system performance has been analyzed in refs. [

44,

45]. Experimental comparisons reported in Refs. [

46,

47,

48,

49] show that although circular coils yield a larger coupling coefficient under identical dimensions, rectangular coils suffer far smaller variation in coupling when lateral misalignment occurs, thereby exhibiting better misalignment tolerance and greater suitability for dynamic wireless charging. Despite their simplicity and manufacturability, single-coil structures experience strong nonlinear degradation of coupling and received power once misalignment occurs, severely limiting their applicability to dynamic or wide-coverage wireless charging scenarios.

To overcome these inherent limitations, researchers have developed multi-coil and segmented-coil architectures to enhance misalignment tolerance, among which the double-D (DD) configuration and its extended forms, such as DDQ and DQDD, have drawn significant attention. A DD coil is typically composed of two adjacent semi-circular conductors that form a flattened and broadened magnetic distribution, enabling the receiver to maintain partial coupling even when laterally displaced. Studies such as Ref. [

50] show that DD coils can offer nearly twice the effective charging area of circular coils and provide enhanced tolerance along the vehicle’s y-axis, which is especially beneficial for dynamic alignment variations during vehicle motion. Further improvements have been achieved through the integration of ferrite materials, as demonstrated in Ref. [

51], while Ref. [

52] developed analytical magneto-geometric models for evaluating the inductance characteristics of ferrite-based DD coils. Cross-DD structures proposed in Refs. [

53,

54] further improve coupling stability by reconfiguring the magnetic-field direction at the transmitter. However, DD coils remain sensitive to misalignment along the x-axis, where transferred power declines rapidly.

To further extend misalignment tolerance, DDQ-based coupling mechanisms have been proposed, wherein a centrally located rectangular Q-coil is added to the DD structure to form a hybrid coil set capable of enhancing mutual inductance distribution and suppressing cross-coupling. Refs. [

55,

56,

57,

58] demonstrated that DDQ coils significantly enhance tolerance along both x- and y-directions and effectively decouple the magnetic interaction between D-coils and the Q-coil. Applications range from dual-channel motor drive systems in Ref. [

55] to CC/CV charging control using DDQ compensation networks in Ref. [

57] while the DQDD structure proposed in Ref. [

58] enhances misalignment tolerance even under large displacement conditions through dual-layer orthogonal coil arrangements.

In addition to DD-based coils, bipolar coils represent another effective approach toward improving misalignment tolerance. A bipolar coil consists of two windings carrying currents in opposite directions, forming a distributed magnetic polarity pattern that produces a relatively uniform flux profile across a wider lateral area. Compared with unipolar or DD coils, bipolar structures preserve stronger coupling under lateral displacement and exhibit more robust performance in wide-coverage charging scenarios. Recent advances include the reconfigurable bipolar (RB) coil in Ref. [

59], which allows switching between vertical and horizontal operational modes by simply altering the current direction, and the hybrid unipolar–bipolar WPT system proposed in Ref. [

60], which supports wide-range constant-current/constant-voltage output and maintains stable performance under vertical displacement and moderate angular misalignment.

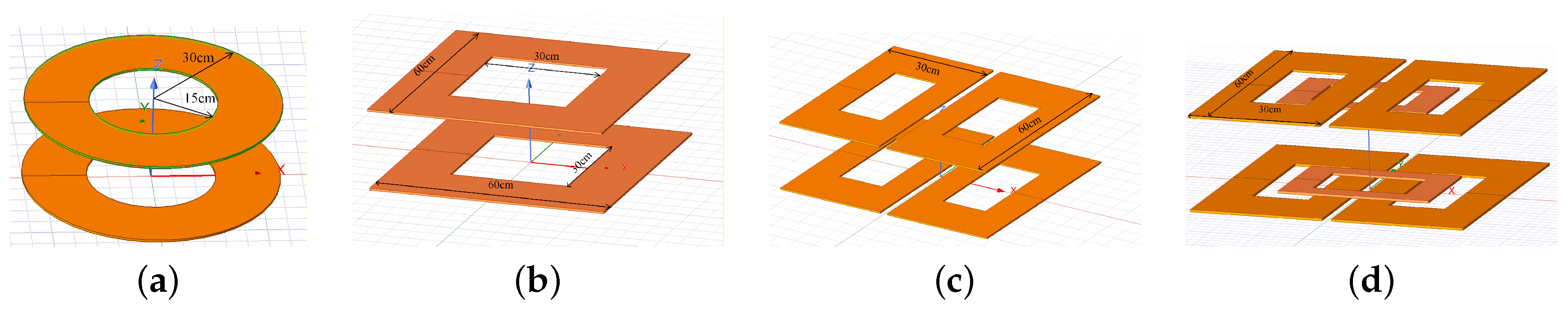

To evaluate and compare the misalignment tolerance of different coupling structures, finite-element models of circular, square, DD, and DDQ coils were established in ANSYS Maxwell 2025, as illustrated in

Figure 11. In the simulations, the vertical separation between the primary and secondary coils was defined as the air gap, which was varied from 15 cm to 45 cm. The horizontal displacement between the coils was characterized by the lateral offset, ranging from −60 cm to 0 cm.

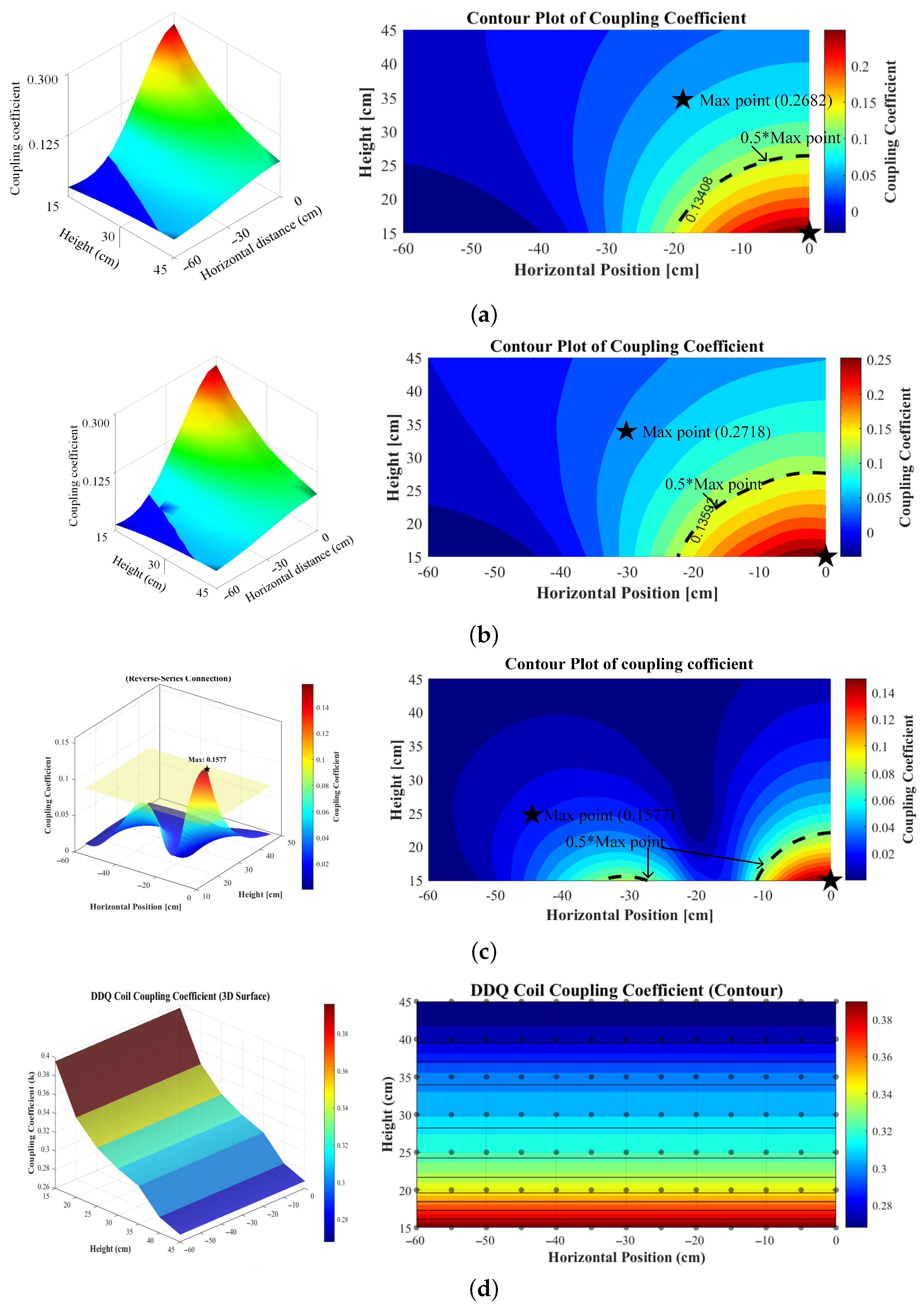

3D surfaces and corresponding contour maps of the coupling coefficient were obtained as functions of both vertical separation and lateral offset for each coil topology (shown in

Figure 12). The simulation results indicate that single-coil configurations, such as circular and square coils, exhibit relatively high coupling coefficients under precise alignment conditions; however, their tolerance to lateral misalignment is limited, with a rapid degradation in coupling as the offset increases. In contrast, DD and DDQ coil structures demonstrate significantly enhanced lateral misalignment tolerance. In particular, the DDQ coil shows a nearly invariant coupling coefficient over a wide lateral offset range (−60 cm to 0 cm), as illustrated in

Figure 12d, highlighting its superior anti-offset capability. Nevertheless, for all investigated coil topologies, the coupling coefficient consistently decreases with increasing air gap, indicating that vertical separation remains a dominant factor influencing magnetic coupling strength.

A quantitative comparison of the different coil structures in terms of misalignment tolerance is summarized in

Table 4, where more stars indicate a larger area of effective charging. The maximum coupling coefficient (

), effective charging area, and misalignment robustness are evaluated for each coil type.

Based on the above analysis and simulation results, the detailed comparison of representative coupling mechanisms in MCRWPT systems is summarized in

Table 5 and

Table 6. It can be seen that single-coil structures such as circular and rectangular coils offer simplicity and high efficiency under ideal alignment but suffer from significant performance degradation under misalignment. In contrast, multi-coil configurations like DD, DDQ, and bipolar coils provide enhanced misalignment tolerance and wider effective charging areas, making them more suitable for dynamic wireless charging applications. Looking forward, the evolution of coupling mechanisms in MCRWPT systems is expected to continue toward more adaptive, intelligent, and multifunctional designs. Future developments are likely to focus on reconfigurable and modular multi-coil architectures that can dynamically adjust the magnetic coupling pattern in response to vehicle position, misalignment, or load variations, thereby maximizing power transfer efficiency under highly variable conditions. Advanced orthogonal and multi-layered coil structures, combined with integrated shielding and ferrite-assisted designs, will further enhance spatial coverage, reduce electromagnetic interference, and improve safety.

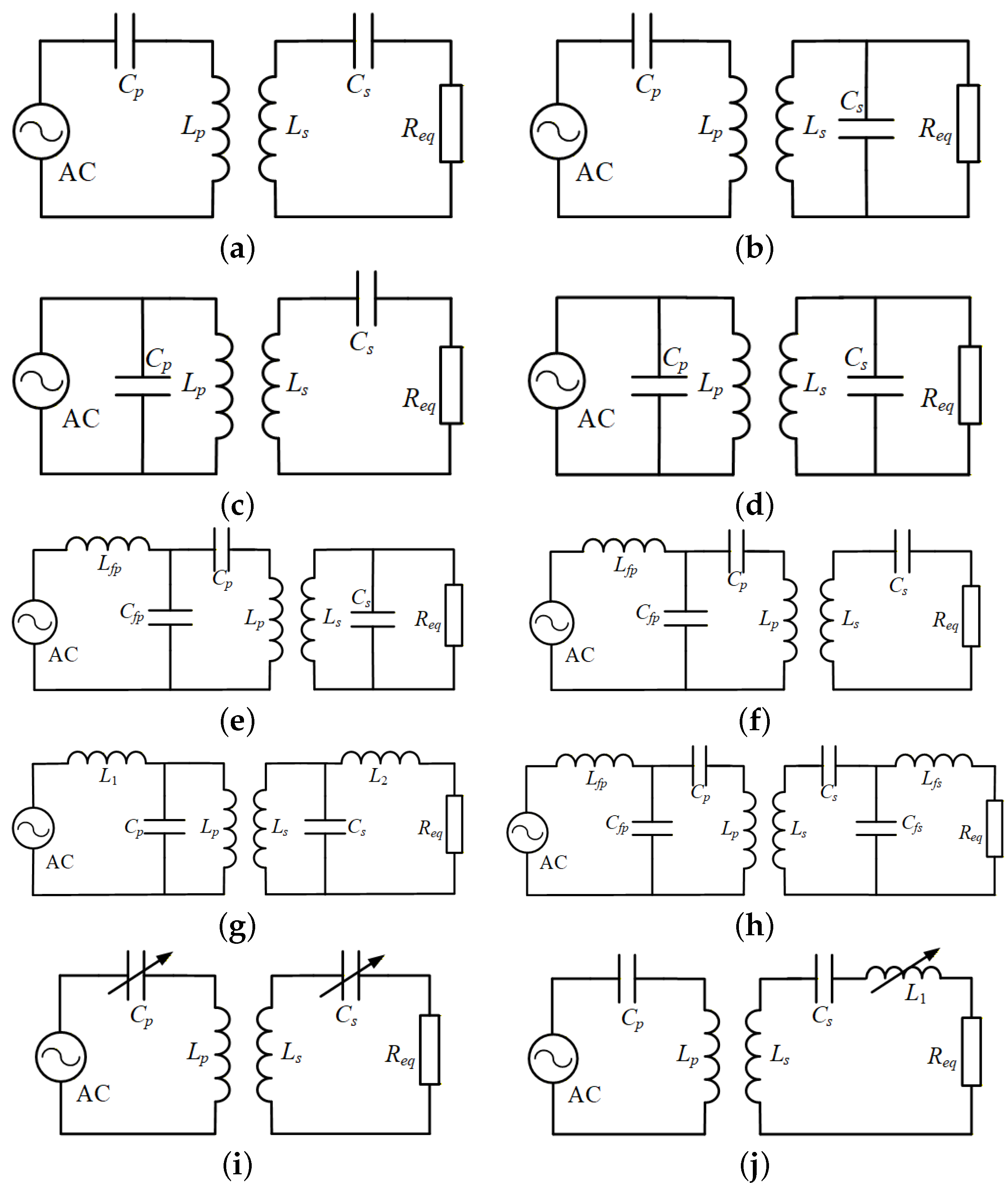

4. Compensation Network

The compensation network plays a crucial role in neutralizing the reactive impedance introduced by the coil inductances in MCRWPT systems. By adding external capacitors or inductors to offset the leakage inductance or reactance of the coils, the compensation network ensures that both the transmitter (Tx) and receiver (Rx) operate at the same resonant frequency. This reduces reactive power, improves the system power factor, and significantly enhances the overall power transfer efficiency. According to the number and configuration of the compensation components, compensation networks can be generally categorized into low-order networks (SS [

61], SP [

62], PS [

63], PP [

64], shown in

Figure 13a–d respectively), high-order networks (LCL, LCC), and hybrid compensation schemes. The lower-order networks are characterized by their simplicity and ease of implementation, but they often exhibit sensitivity to load and coupling variations. In contrast, high-order networks introduce additional reactive elements that provide greater flexibility in tuning system resonance, achieving soft-switching conditions, and maintaining stable operation across a wider range of load and coupling scenarios.

High-order compensation networks, particularly the LCC and LCL topologies, have become mainstream in research and application due to their superior performance. The LCC topology is distinguished by its ability to provide load-independent constant current (CC), while facilitating zero-voltage switching (ZVS) for primary-side switching devices. In previous studies, ref. [

65] systematically elaborated the tuning methodology for double-sided LCC (DS-LCC), demonstrating that its resonant frequency remains independent of load and coupling variations. Their 7.7-kW prototype achieved a DC–DC efficiency of 96%, establishing a benchmark for high-power static charging. To accommodate battery charging profiles, reconfigurable topologies such as LCC-S have been derived. For instance, ref. [

66] designed a switchable hybrid LCC-S network in which the transition between CC and CV modes is accomplished merely by toggling two AC switches on the secondary side to alter the capacitor configuration, without modifying the main circuit. Furthermore, ref. [

67] proposed a hybrid LCC–SP topology that enables smooth mode switching through parameter adjustment rather than structural reconfiguration, while maintaining ZVS conditions.

In contrast to the CV/CC source characteristics of LCC, the LCL topology offers the distinct advantage of providing an approximately ideal current-source characteristic at the inverter side. This ensures that the primary-side current remains relatively stable under variations in load and coupling, significantly reducing current stress on power devices and simplifying control. Ref. [

42] identified limitations in conventional DS-LCL and improved its parameter design, increasing prototype efficiency from 87.3% to 90.2%. This inherent feature makes LCL naturally suitable for multi-load power supply scenarios. Ref. [

68] utilized two orthogonal LCL-compensated coils to generate a rotating magnetic field, enabling simultaneous power delivery to multiple receivers. Ref. [

69] extended this approach to multi-channel systems, achieving independent power regulation for each receiver without complex algorithms or additional converters. In the domain of dynamic wireless charging, ref. [

70] proposed a segmented-track architecture based on LCL complementary compensation, which reduces system cost and volume through resonant component reuse while preserving constant-current characteristics.

Figure 13.

Compensation networks for MCRWPT. (

a) S-S [

61]. (

b) S-P [

62]. (

c) P-S [

63]. (

d) P-P [

64]. (

e) LCC-P [

67]. (

f) LCC-S [

71]. (

g) LCL-LCL [

42]. (

h) LCC-LCC [

65]. (

i) Variable capacitor [

72]. (

j) Variable inductor [

73].

Figure 13.

Compensation networks for MCRWPT. (

a) S-S [

61]. (

b) S-P [

62]. (

c) P-S [

63]. (

d) P-P [

64]. (

e) LCC-P [

67]. (

f) LCC-S [

71]. (

g) LCL-LCL [

42]. (

h) LCC-LCC [

65]. (

i) Variable capacitor [

72]. (

j) Variable inductor [

73].

To maintain high efficiency and soft-switching over wider operating ranges, such as under large output voltage variations or strong coupling changes, dynamic tuning techniques have emerged as a cutting-edge focus. These primarily include switched-controlled capacitors (SCCs) and variable inductors (VI). Ref. [

74] integrated SCCs with phase-shift modulation in an LCC-S network, achieving a wide output voltage range of 100–250 V and full-range ZVS in a 500-W system, with a peak efficiency of 94.7%. Ref. [

75] combined SCCs with triple-phase-shift control in an LCC-LCC topology to extend the ZVS range under high coupling variation, achieving a peak efficiency of 96.2% in a 3.3-kW prototype. Ref. [

72] proposed a novel variable-capacitor LCC-S topology, dynamically adjusting capacitance to minimize circulating current, thereby improving overall efficiency across a wide voltage range. On the other hand, variable inductor technology provides continuous and smooth adjustment capability. Ref. [

76] proposed an architecture based on a dual half-bridge inverter and two variable inductors, regulating output through inductance modulation rather than phase shifting. This approach fundamentally eliminates circulating current, enables wide-range ZVS, and increases peak efficiency by 3.65% to 92.4% compared to conventional phase-shift control. Ref. [

73] employed a secondary-side variable inductor combined with detuned operation in an underwater vehicle wireless charging system, achieving remarkable misalignment tolerance of ±47% horizontally and +140% vertically.

As systems evolve toward dynamic, multi-load, and bidirectional operation, control strategies have shifted from steady-state design to advanced closed-loop control ensuring transient stability and safety. For scenarios where wireless communication is undesirable, indirect control strategies are highly favored. Ref. [

77] developed a comprehensive transient model for an LCC-S system, revealing that secondary voltage/current are proportional to primary inverter current and coil current, respectively. Based on this relationship, they proposed a primary-side dual-loop indirect control strategy for precise tracking of battery charging profiles. For more complex two-stage systems, ref. [

78] addressed the risk of overvoltage and overcurrent during shutdown of the secondary Buck converter in an LCC–LCC system by proposing a bilateral indirect closed-loop control scheme, applying cascaded-system stability theory to provide a unified methodology for controller design.

Research on resonant networks has extended beyond traditional boundaries into multi-receiver management and novel transfer mechanisms. To address cross-coupling and power distribution challenges in multi-receiver systems. Ref. [

79] proposed a double-sided LCL-CPT design that suppresses reactive power by maintaining a 90° phase shift between plate voltages, achieving 90% efficiency in a 500-W system.

For multi-receiver WPT systems, switching arrays have proven effective in addressing cross-coupling and power distribution challenges. Ref. [

80] employed relay-based switching of compensation capacitors to modify the resonant frequency, enabling selective power delivery to a targeted receiver within a one-to-three multi-receiver system and effectively mitigating power imbalance. Ref. [

81] introduced an active reactance compensator within each receiver—functionally analogous to a switched-controlled half-bridge—that regulates the phase of the receiver current to maintain orthogonality with the transmitter current, achieving receiver decoupling and stable output regulation for multi-load operation.

Table 7 summarizes the key features, advantages, and limitations of various resonant compensation networks used in WPT systems. As for these networks, low-order topologies such as S–S, S–P, P–S, and P–P are characterized by their simplicity and ease of implementation but often exhibit sensitivity to load and coupling variations. High-order topologies like LCC and LCL introduce additional reactive elements that provide greater flexibility in tuning system resonance, achieving soft-switching conditions, and maintaining stable operation across a wider range of load and coupling scenarios. Hybrid compensation schemes incorporating dynamic tuning elements such as variable capacitors and inductors further enhance regulation capabilities and adaptability to changing operating conditions. Future advancements will be driven by the deep integration of topological innovation, dynamic tuning technologies, and advanced control algorithms, collectively propelling WPT systems toward higher efficiency, greater adaptability, and enhanced intelligence.

Table 8 summarizes resonant conditions, output formulas, and properties of various compensation networks used in WPT systems. It can be seen that compensation networks has load-independent output characteristics, which is beneficial for maintaining stable operation under varying load and coupling conditions. The output formulas indicate whether the network provides constant-current (CC) or constant-voltage (CV) characteristics, guiding the selection of appropriate topologies based on specific application requirements. Based on this table, a general design procedure for resonant compensation networks is further provided (shown in

Figure 14), which explicitly links the required output characteristic (CC or CV) to the selection of the compensation topology and parameter design. It should be emphasized that the presented design procedure focuses solely on the intrinsic output behavior of the resonant networks under resonant conditions, without involving additional control methods such as phase-shift control, duty-cycle modulation, or the introduction of post-stage DC–DC converters at the receiver side.

6. Control Methods

The system performance of WPT systems is critically dependent on effective control strategies that can adapt to dynamic operating conditions. According to the location of control-signal generation and associated actuation mechanisms, WPT control methodologies have evolved along three major technological paths, distinguished by the location of control-signal generation and the associated actuation mechanisms: primary-side control, secondary-side control, and dual-side cooperative control currently. Primary-side control centralizes all sensing and regulation at the transmitter, where primary-side electrical quantities (e.g., voltage and current) are monitored to indirectly infer and adjust the receiver-side conditions. Its foremost advantage lies in the simplicity of the receiver, which requires no controller, thereby reducing cost and enhancing reliability. Nevertheless, the accuracy and dynamic performance of such strategies are fundamentally constrained by model fidelity and parameter sensitivity.

In contrast, secondary-side control places the control authority on the receiver. By directly sampling load-side voltage or current and regulating an active rectifier or post-stage DC–DC converter, this approach enables precise and fast power control. However, it typically requires additional active components and control circuitry on the secondary side, increasing complexity, cost, and sometimes form-factor constraints. To achieve a balance between control accuracy, system flexibility, and overall performance, dual-side cooperative control has emerged as a compelling solution. By deploying coordinated controllers on both the primary and secondary sides, these strategies can maintain high efficiency and stable operation under wide variations in coupling coefficient and load conditions. The key challenge, however, is the design of low-latency and reliable communication between the two sides—or alternatively, the development of intelligent control frameworks that achieve cooperation without explicit communication. Although primary-side, secondary-side, and dual-side control strategies form the basis of conventional WPT regulation, their performance often depends on accurate system models and fixed control laws. As WPT applications move toward dynamic and uncertain environments, these model-based approaches increasingly face limitations in adaptability and robustness. This has motivated the introduction of AI-driven control methods, which leverage data-driven learning and real-time optimization to enhance system autonomy and efficiency.

6.1. Primary Side Control

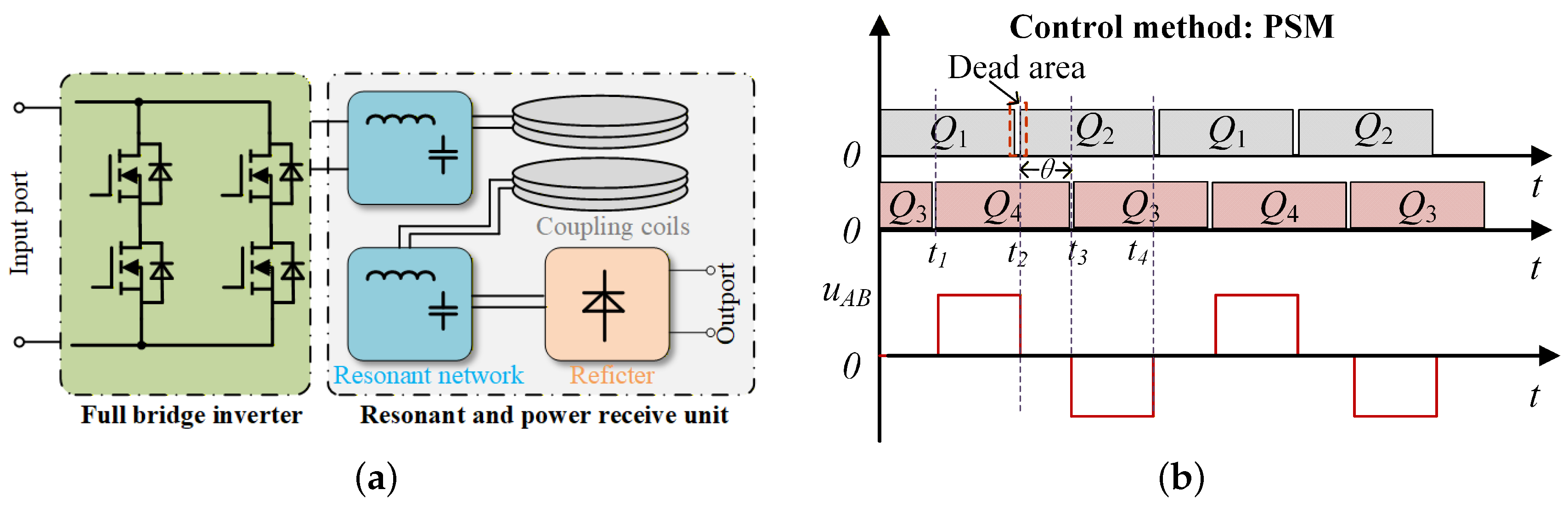

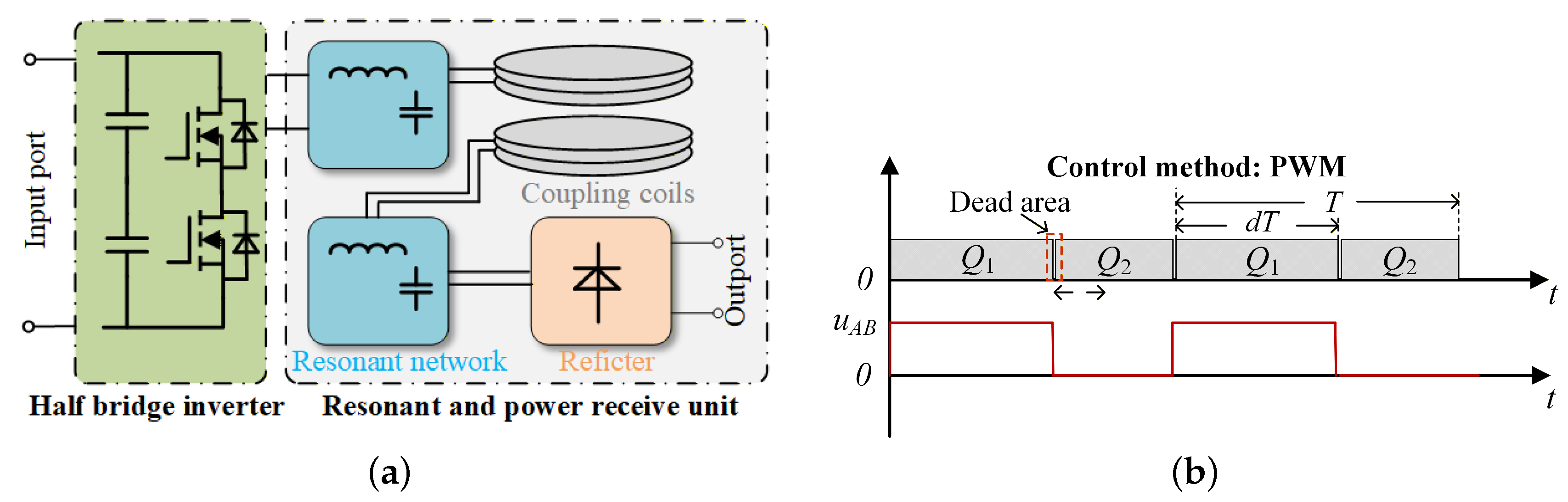

In magnetically coupled WPT systems, primary-side control plays a central role in achieving efficient and stable energy transmission(shown in

Figure 21). By precisely regulating the front-end DC–DC converter or high-frequency inverter, the primary controller indirectly governs the power delivered to the load. Frequency control is one of the most classical primary-side strategies. By adjusting the switching frequency of the inverter, the operating point of the resonant network shifts, thereby modifying the effective impedance seen by the inverter and enabling output regulation. Since the system gain peaks at the resonant frequency and decreases as the operating frequency detunes, frequency control naturally supports output voltage or current regulation while facilitating soft switching. Leveraging this principle, ref. [

100] proposed a dual off-resonant frequency-based mutual inductance identification method and developed a primary-side constant-current/constant-voltage control scheme for an XS-compensated system. The proposed method eliminates the control complexity typically associated with frequency modulation under varying coupling conditions. Extending the concept to multi-load systems, ref. [

101] introduced a hybrid-modulation SPWM–based multi-frequency WPT architecture in which the inverter synthesizes different frequencies to independently supply loads with distinct resonant characteristics, achieving a power factor as high as 0.99. Compared with frequency control, phase-shift control (PSC) regulates power by adjusting the phase difference between the upper and lower bridge arms of a full bridge, without altering the switching frequency. PSC modulates the amplitude of the fundamental component of the inverter output voltage while maintaining operation at the optimal resonant point. As a result, it typically achieves wide-range power control along with zero-voltage switching (ZVS) over the full load range.

In addition to phase shift, duty-cycle control represents another effective means of inverter power modulation, particularly attractive when reducing secondary-side control complexity is desirable. By varying the pulse width of the inverter output, the effective output voltage is modulated, enabling single-variable control with potentially reduced switching loss. Following this principle, ref. [

102] proposed a duty-cycle control method for a dual-sided LCC converter, effectively replacing the conventional PSC approach that requires precise gate-signal synchronization. By eliminating synchronization between primary and secondary switches, the proposed method significantly simplifies control while reducing switching frequency and conduction loss in the secondary active rectifier.

Notably, hybrid control strategies that combine multiple control degrees of freedom are emerging as a powerful approach for addressing complex operating conditions and achieving system-level performance optimization. These strategies overcome the limitations of single-dimensional control by coordinating multiple mechanisms. A representative example is the dual-switch-controlled capacitor and enhanced pulse-density modulation scheme proposed by [

103] for a one-to-three WPT system. By jointly adjusting reactance (via SCC) and effective voltage amplitude (via PDM) under fixed-frequency operation, the system achieves full-range CC/CV output regulation and ZVS in the inverter, demonstrating the strong potential of hybrid methods for multi-objective optimization.

6.2. Secondary Side Control

Secondary-side control in WPT systems places the power regulation at the receiver, enabling direct responsiveness to load demands and effective compensation for coupling variations (shown in

Figure 22). Existing techniques can be broadly classified into two categories: (i) Regulating a post-stage DC–DC converter; (ii) Directly controlling an active or semi-active rectifier. Both approaches rely on key control variables, such as duty cycle, phase shift to achieve precise power conditioning and robust system performance.

When a post-stage DC–DC converter is adopted as the control actuator, the control mechanism becomes relatively straightforward, as output voltage or current can be regulated by adjusting the duty cycle of the converter switches. For instance, ref. [

104] introduced a secondary Buck converter for supercapacitor charging and employed a variable-step perturb-and-observe algorithm to track the maximum efficiency point, while leveraging the inherent load-independent constant-current characteristic of the dual-LCC topology to facilitate CC charging. Although this method achieves effective decoupled control, the additional power stage inevitably increases system losses and hardware volume. To pursue higher efficiency and power density, recent research has shifted toward direct control of secondary-side active rectifiers, where phase-shift control has emerged as a dominant strategy. Ref. [

105] proposed a CC/CV charging scheme based on secondary active rectification, in which adjusting the phase shift in the rectifier switches modulates its equivalent impedance. This eliminates the need for wireless communication and enables accurate CC/CV regulation, achieving a peak efficiency of 90.71% at a 15 cm transfer distance. A more sophisticated example is the synchronized secondary-side control framework introduced by [

106]. Their method avoids AC current sensing and real-time communication by incorporating a fast outer-loop output controller and an inner-loop phase synchronization mechanism. To further overcome the limitations of traditional PWM (efficiency degradation at light loads) and the high ripple issues associated with conventional PDM, advanced modulation schemes have been developed. A representative contribution is the hybrid modulation (HM) technique proposed by [

107]. By optimizing the pulse distribution of discrete PDM to eliminate even-order harmonics in the rectifier input voltage, the method reduces current distortion and output voltage ripple. In the area of adaptive resonant tuning, combining switch-controlled capacitors (SCC) with secondary-side control has demonstrated substantial performance improvements.

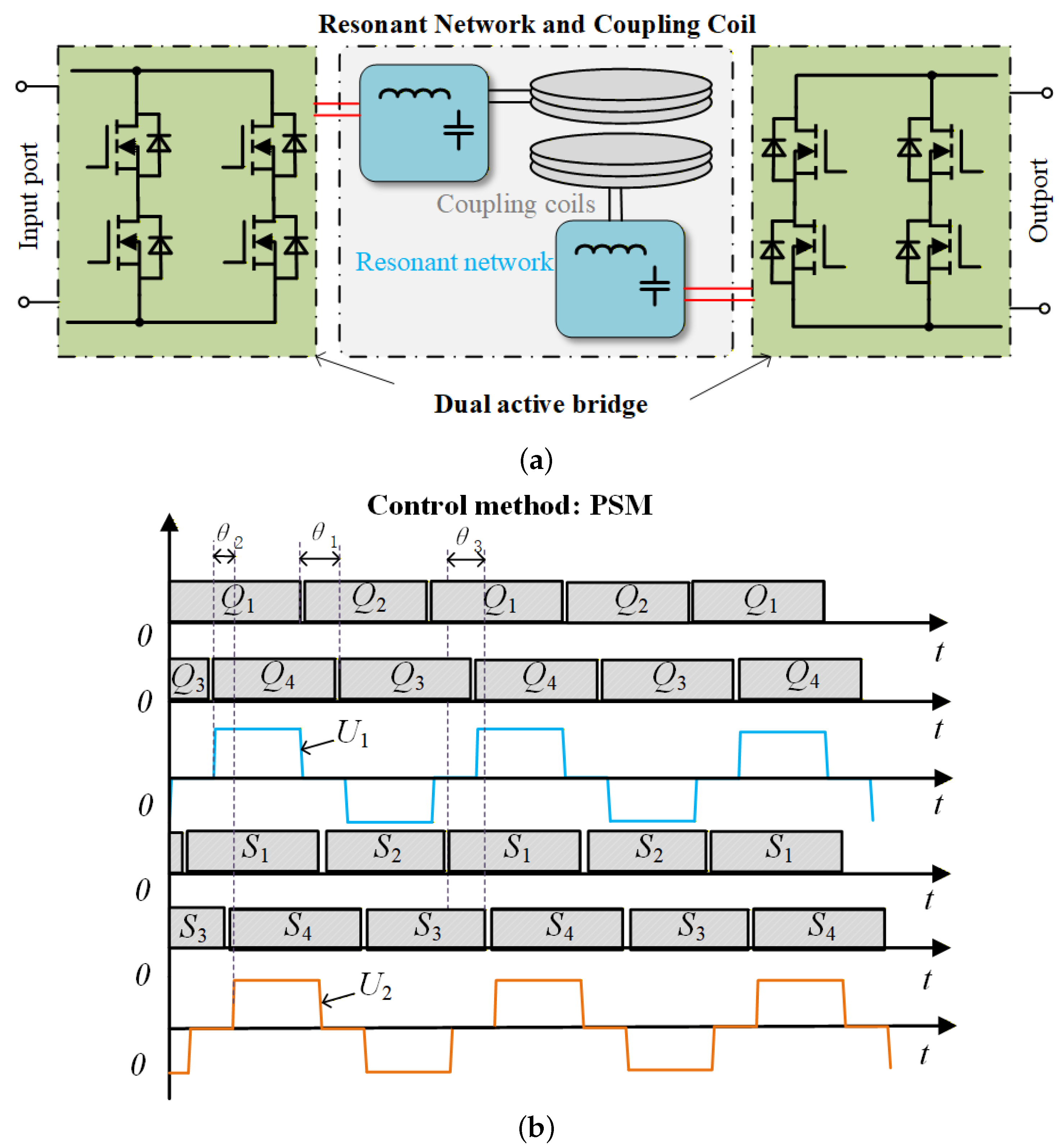

6.3. Double Side Control

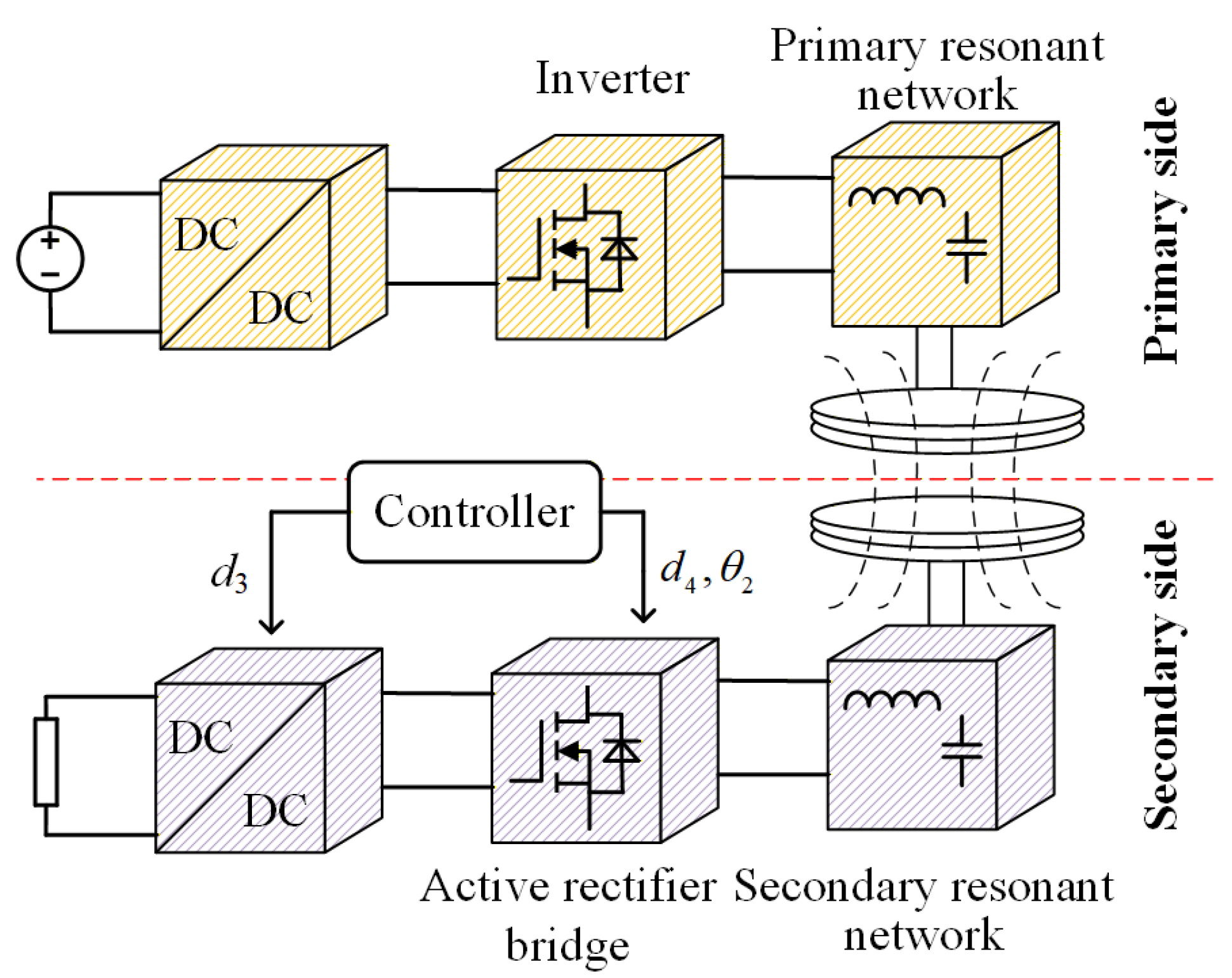

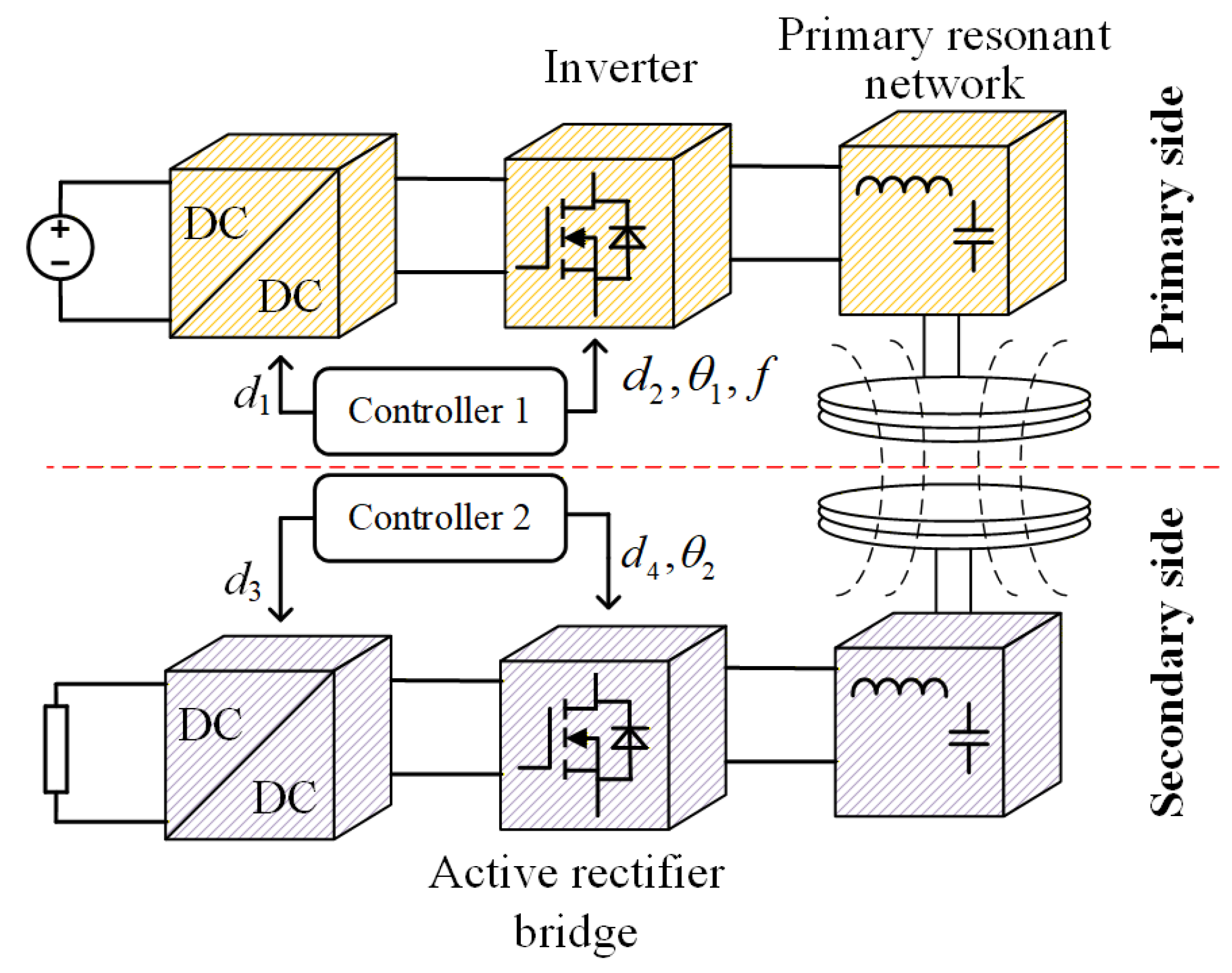

The essence of bilateral control technology in WPT systems lies in jointly exploiting the control degrees of freedom on both the primary and secondary sides (shown in

Figure 23). Through carefully coordinated strategies, such systems can achieve efficient and stable operation under varying coupling conditions and fluctuating loads, without relying on high-speed real-time communication. Depending on the control objectives and implementation approaches, bilateral control schemes can be broadly categorized into power cooperative control, resonance-parameter co-tuning, and cooperative driving for special loads.

In the area of power cooperative control, research primarily focuses on how to coordinate primary- and secondary-side controllers to simultaneously achieve constant-current/constant-voltage (CC/CV) charging and system-efficiency optimization. For higher-power applications, ref. [

108] addressed the increase in active power caused by coil misalignment in SS-compensated WPT systems by proposing a simple constant-active-power control scheme. In this strategy, the secondary side regulates the dc-link voltage based on the active-power reference and measured secondary current to constrain the system’s power transfer, allowing accurate rating of primary and secondary power devices in a 300-kW rail vehicle application.

In the domain of resonance-parameter co-tuning, the objective is to mitigate detuning issues caused by component drift or coupling variations. Ref. [

109] designed a bilateral frequency-decoupled tuning strategy for an LCC/S-compensated WPT system. The primary side employs a zero-phase-angle control method based on optimal-efficiency tracking to minimize reactive power, while the secondary side uses a two-step perturb-and-observe approach with maximum-current search to independently adjust the resonant parameters of both sides. This decoupled architecture allows the system to maintain resonance cooperatively without information exchange, offering strong robustness against parameter variations and significantly improving transmission efficiency and stability.

Regarding cooperative driving for special loads, bilateral control demonstrates considerable flexibility in system-architecture design. Ref. [

110] developed a sophisticated bilateral control system to realize precise wireless control of a hybrid stepper motor. On the primary side, control signals and power are simultaneously delivered to the secondary side by modulating the frequency, duty cycle, and sequence of the transmitter-coil current. The secondary side incorporates four decoupled current channels that separate power and control signals using a dual-frequency resonant network, and drive four self-commutated switches. This configuration eliminates the need for any secondary-side controllers or sensors, while still enabling fully wireless control of motor speed, direction, and position.

Table 9 summarizes and compares the key characteristics of primary-side, secondary-side, and dual-side control strategies in WPT systems, highlighting their respective principles, methods, advantages, limitations, and typical applications.

6.4. AI-Based Control Approaches for WPT Systems

With the rapid progress of artificial intelligence, data-driven control has become an emerging paradigm for WPT. In contrast to traditional model-based methods that rely on accurate circuit modeling and parameter identification, AI-enabled controllers offer strong adaptability, predictive capability, and robustness against detuning, misalignment, and environmental disturbances. Recent studies show that integrating machine learning (ML) and reinforcement learning (RL) into WPT systems substantially enhances regulation accuracy, transmission efficiency, and operational flexibility across EV charging [

111,

112] (shown in

Figure 24). One representative example is the work of [

113], which introduced a data-driven recursive current-tracking method to address the long-standing challenge of achieving precise synchronous switching in active rectifiers. Instead of relying on detailed circuit models or extensive sensing hardware, their algorithm estimates the amplitude and phase of the rectifier input current in real time using only sampled data, and subsequently generates accurate gating signals to ensure synchronized switching.

RL-based approaches have been applied to achieve model-free output regulation. A dynamic-programming RL controller enables both constant-voltage and constant-current operation in LCC-type WPT systems by learning optimal compensation parameters from primary-side measurements [

112]. The method achieves <1.3% output error without sacrificing efficiency, demonstrating the potential of RL-driven adaptive compensation tuning. Deep-learning methods further improve adaptive frequency control and energy distribution. These AI-driven control strategies not only enhance performance but also reduce reliance on precise system models and extensive sensing, providing lightweight, scalable solutions for complex WPT scenarios.

As for application, AI/RL techniques in WPT can be broadly categorized based on the specific challenges they address, as summarized in

Table 10. Refs. [

114,

115,

116] employs neural networks to map measurable electrical signatures at the transmitter side, such as voltage, current, or phase information, to the relative misalignment or coupling condition between the transmitting and receiving coils. In these studies, AI serves as a perception or identification module, enabling online estimation of coupling-related states without introducing additional sensors or directly interfering with the power control loop. Ref. [

111] formulates frequency selection or adjustment as a sequential decision-making problem, where the learning agent modifies the operating frequency based on efficiency-related or phase-based feedback. Importantly, most reported studies position RL at a supervisory level, where it operates in parallel with or on top of conventional control mechanisms, rather than replacing fast inner control loops.

While the above studies demonstrate the potential of RL-based control in WPT systems, their direct translation to full-scale EV prototypes remains non-trivial. Most existing works validate performance improvements through simulation or laboratory-scale experimental platforms, typically at sub-kW to few-kW power levels. In practical EV implementations, additional challenges such as sensor noise, parameter drift due to temperature variation, electromagnetic interference, and safety constraints significantly affect controller performance. These factors introduce a distribution mismatch between training environments and real-world operating conditions, which may degrade the performance of purely simulation-trained RL policies. As a result, current RL-based WPT control is better regarded as a decision-support or adaptive tuning layer, rather than a fully autonomous replacement of conventional control loops. The extension of RL methods to full-scale EV prototypes with guaranteed safety and robustness remains an open research challenge.

7. Discussion

The rapid electrification of transportation is accelerating the demand for efficient, safe, and intelligent wireless charging technologies. With the global transition toward high-power fast-charging EVs, autonomous driving, and vehicle-to-grid (V2G) integration, WPT systems must evolve beyond traditional static, single-function chargers. Future WPT infrastructures are expected to support dynamic charging, extended misalignment tolerance, wide power ranges, and intelligent grid interaction. These trends redefine the technical requirements for coupling mechanisms, resonant topologies, power converters, and control algorithms.

Coupling Mechanisms: Modern EV applications require WPT systems that maintain high efficiency despite coil displacement, road unevenness, or autonomous parking uncertainties. Traditional single coils offer limited tolerance to misalignment, motivating the development of advanced coupling structures such as DD, DDQ, bipolar, and multi-coil array architectures. Future coupling mechanisms will likely converge toward wide-coverage, field-shaping, and self-optimizing coil structures, enabling dynamic charging lanes, UAV landing pads, and spatially distributed charging surfaces. Reconfigurable magnetic arrays and multi-coil activation schemes are expected to play a key role in enabling adaptive energy focusing and enhanced position freedom.

Resonant Compensation: Resonant compensation remains essential for overcoming weak coupling, minimizing reactive power, and maximizing energy transfer efficiency. Classical SS/SP/PS/PP networks have evolved into high-order topologies such as LCC, LCL, and LLC to support soft switching, broaden operating bandwidth, and improve robustness under variable coupling conditions. The next stage of evolution lies in hybrid and reconfigurable compensation networks capable of dynamically switching between CC/CV modes, tuning resonant frequency, or adapting impedance based on real-time load requirements. Integration with AI-driven parameter estimation and online frequency tracking will further enhance system adaptability in complex charging environments.

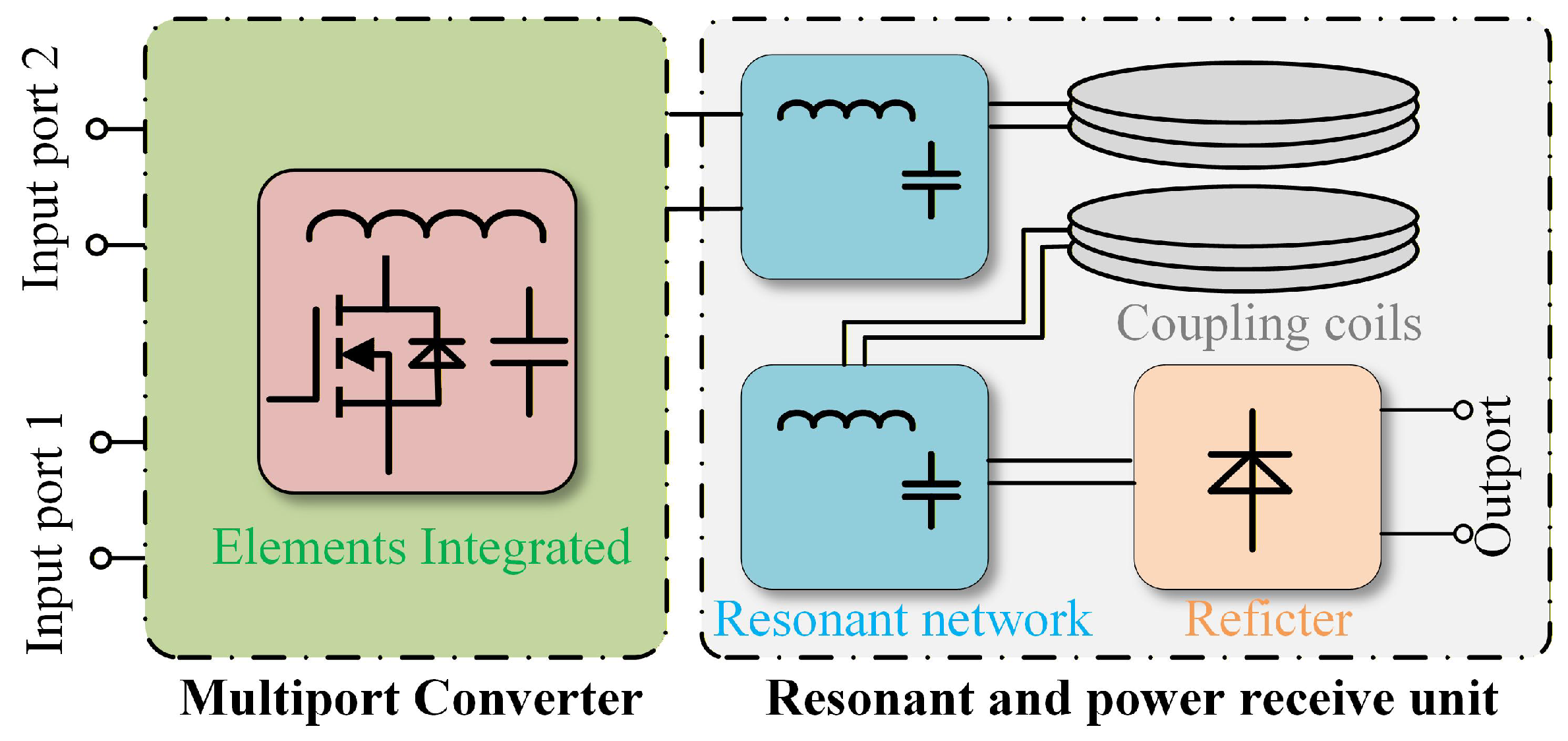

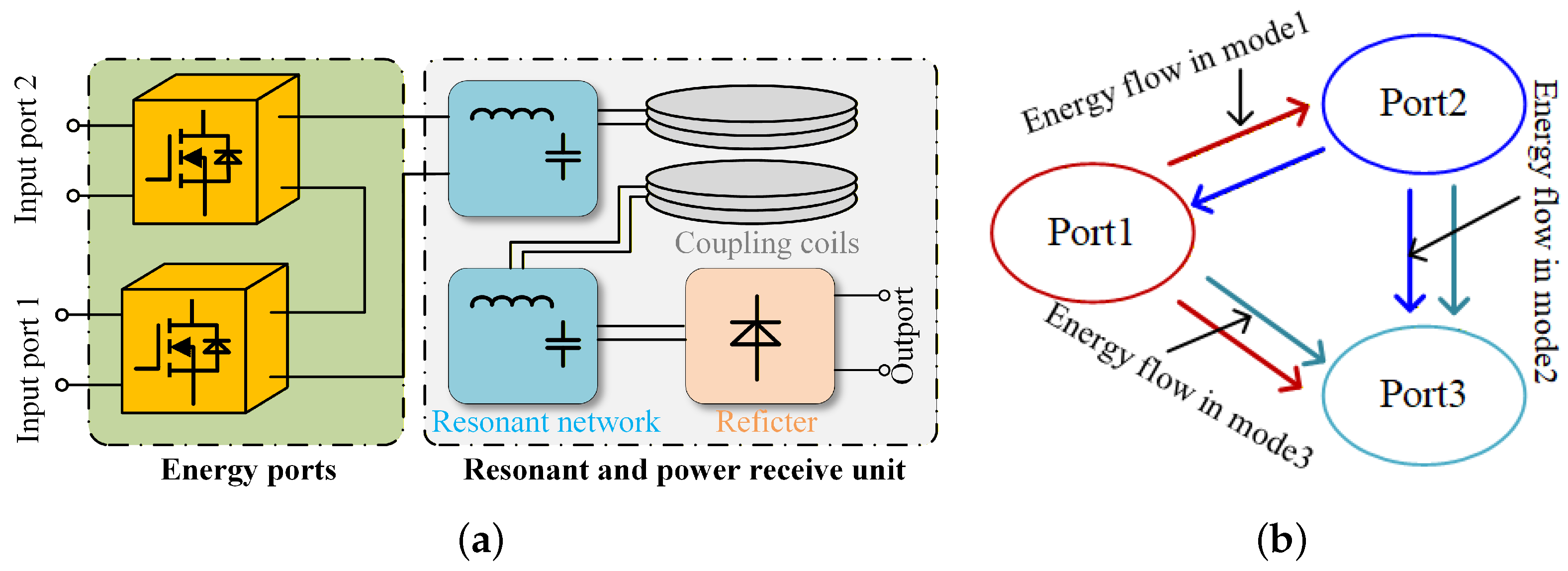

Power Converter Trends: With the shift toward dynamic EV wireless charging, WPT systems must increasingly support multi-source energy coordination and bi-directional power flow among onboard batteries, traction systems, and grid-connected infrastructure. These evolving requirements place higher demands on the flexibility and integration level of the power conversion stage. However, conventional two-port converter architectures remain constrained by multi-stage power processing, limited scalability, and strong port coupling. They typically need additional DC–DC or AC–DC interfaces to connect batteries, auxiliary loads, or microgrid nodes, leading to increased losses, larger volume, and more complex control. Their inability to manage multiple energy paths efficiently makes them unsuitable for the emerging multi-energy, dynamic charging ecosystem. In this context, MPCs will play an increasingly central role in WPT systems, enabling unified energy routing between WPT coils, energy storage units, and DC microgrids within a single power stage. High-frequency, high-density converter architectures leveraging wide-bandgap semiconductors will be crucial for achieving compactness and efficiency.

Control Strategies Development: As EV charging moves toward higher power, wider spatial freedom, and dynamic in-motion operation, WPT systems must operate under rapidly changing coupling conditions, uncertain loads, and strict efficiency constraints. These increasingly complex environments expose the limitations of traditional model-based controllers, which rely on accurate circuit models and fixed-parameter tuning. Such methods struggle to maintain optimal regulation and soft-switching when mutual inductance, resonant frequency, or load conditions deviate from their nominal design points. This growing mismatch between system complexity and controller rigidity is driving a clear shift from classical model-based control toward data-driven and learning-enabled approaches. AI-based techniques offer strong adaptability, real-time prediction, and model-free optimization. They have demonstrated the ability to autonomously tune resonant parameters, track optimal operating frequency, enhance misalignment tolerance, and improve power distribution efficiency without requiring explicit system models.

Despite substantial progress in coupling structures, resonant compensation networks, power converters, and intelligent control strategies, the large-scale deployment of dynamic EV wireless charging remains constrained by several fundamental bottlenecks. Maintaining stable and high-efficiency operation under rapid coupling variation caused by vehicle motion, misalignment, and road unevenness is still challenging at the system level, as existing couplers and compensation networks are predominantly designed for quasi-static conditions. In addition, scaling power conversion architectures toward high-power dynamic charging is limited by magnetic integration, thermal management, and control coupling complexity. Furthermore, although data-driven and learning-based control methods show strong adaptability in simulations and laboratory prototypes, their robustness, convergence guarantees, and compliance with safety and standardization requirements under communication-free operation have not yet been fully established. These unresolved issues collectively hinder the transition of dynamic wireless charging from experimental demonstrations to large-scale real-world deployment.

8. Conclusions

This paper has reviewed the key developments in WPT, with a particular emphasis on MCRWPT as the most mature technology for medium-range, high-efficiency EV charging. Prior research has addressed fundamental limitations such as weak coupling, misalignment sensitivity, and efficiency degradation through advances in coil geometry optimization, magnetic-field shaping, and compensation design to enhance field uniformity and energy-transfer robustness. To accommodate high-power and rapidly varying operating conditions, researchers have also proposed high-order and hybrid resonant compensation networks that expand the soft-switching region, maintain stable operation under parameter deviations, and support CC/CV charging. On the converter level, the need for multi-source coordination and bidirectional energy flow has driven the evolution from traditional half-/full-bridge inverters toward DAB converters and integrated MPC architectures, enabling unified power routing between WPT coils, storage units, and microgrid interfaces. Meanwhile, control strategies have shifted from single-side control to cooperative primary–secondary control and emerging AI-based approaches that provide real-time adaptation without relying on accurate circuit models.

Looking ahead, the widespread deployment of EVs will push WPT toward higher power density, greater spatial freedom, and deeper energy-network integration. This trajectory requires coupling structures that support wide-area coverage and strong misalignment tolerance; resonant compensation networks capable of adaptive reconfiguration and mode switching; converter architectures that consolidate multiple energy ports and operate efficiently at high frequency; and intelligent control strategies—potentially AI-driven—that can maintain optimal operation under dynamic environments with minimal sensing and communication overhead. The convergence of these technologies will enable WPT systems to evolve from point-to-point chargers into intelligent, resilient, and large-scale wireless energy distribution platforms suitable for next-generation electric transportation and distributed energy networks.