5. Results

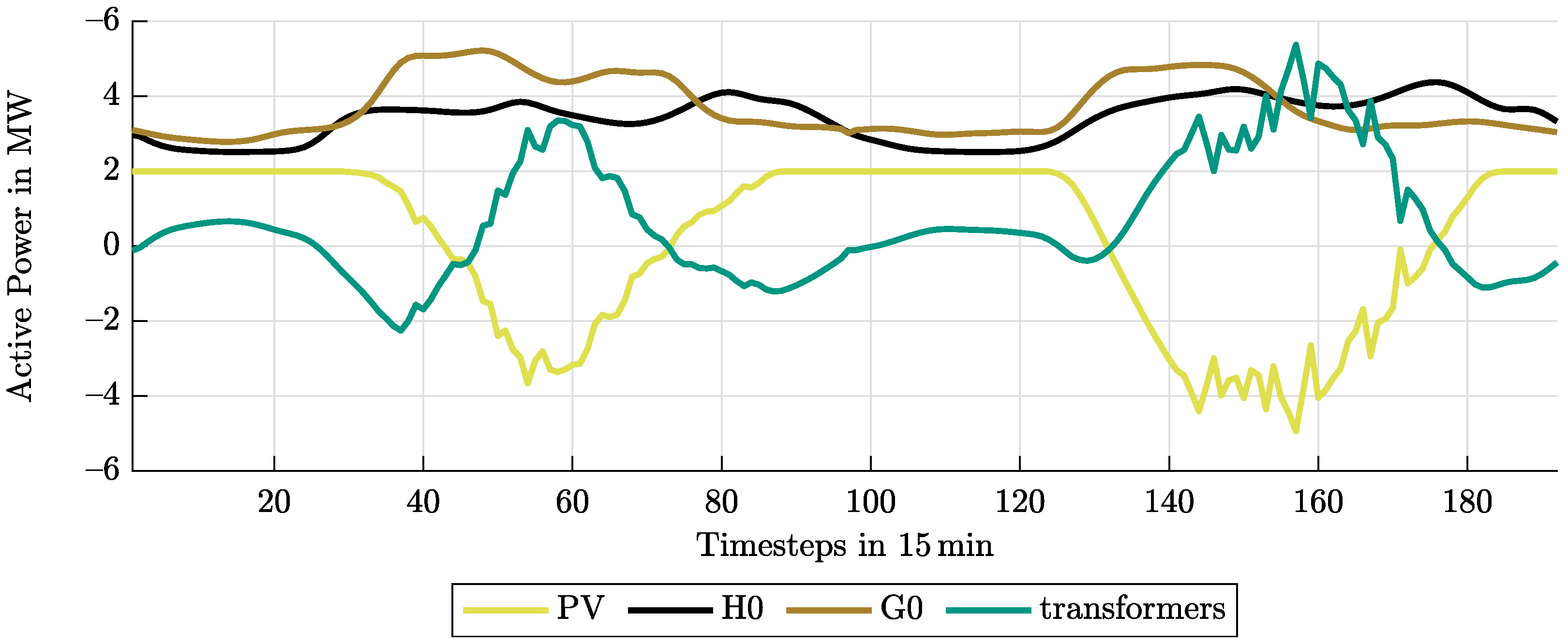

Figure 3 shows the load profile with a PV penetration of 100% over two days in 15 min time steps. It can be seen that on both days, the PV feed-in exceeds the total power of the loads, resulting in reverse power flow.

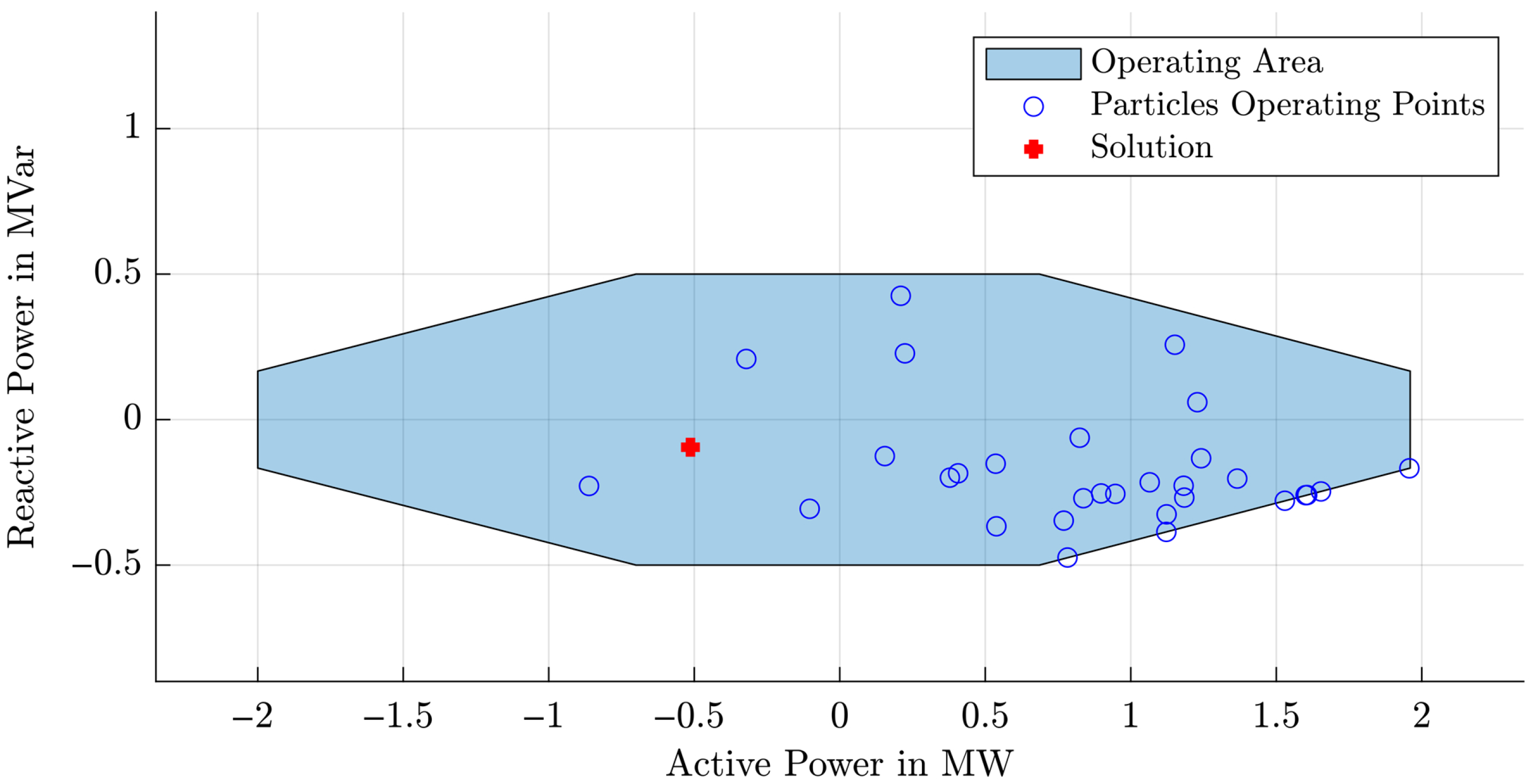

The operating point of the MVDC connections for Scenario 1 (a) with a 100% PV penetration is presented in

Figure 4. While aiming for a loss reduction and power transfer minimization, it is clearly evident that the MVDC connections are transferring active power during PV feed-in. According to

Table 5, the transmitted power has been reduced by 4.53% compared to the initial value, while the power losses have been reduced by 21.42% as shown in

Table 6. Both results indicate a significant improvement in the power system efficiency.

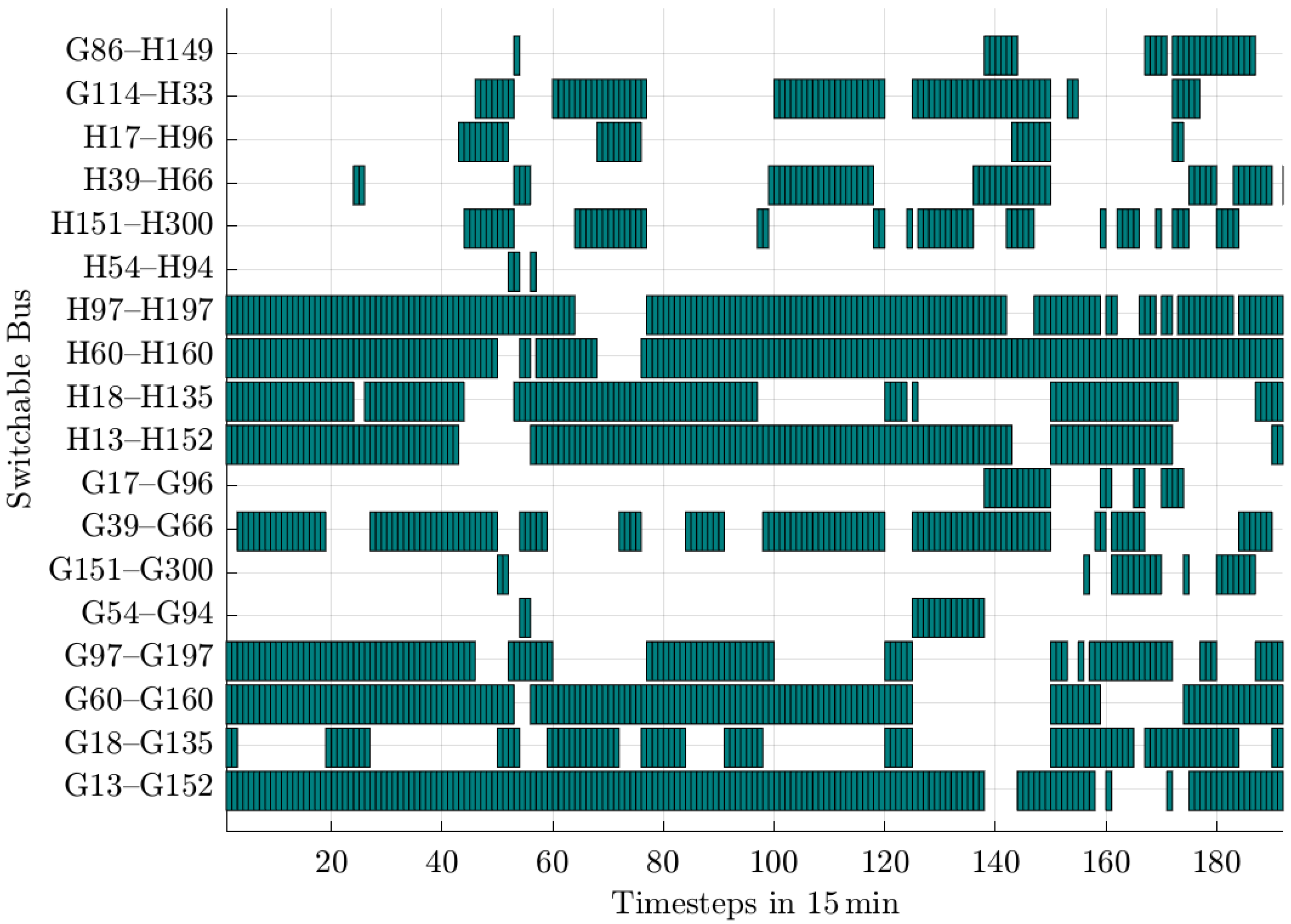

For the case of optimizing AC switches in Scenario 2 (a) with PV-penetration of 100% and forbidden ring branches, the results of the switch states can be seen in

Figure 5. A green block for a timestep in this figure means that the corresponding switch listed on the y-axis is closed. It can be observed that during periods with PV feed-in, switching operations occur more frequently, resulting in several different topologies within a short time span, compared to periods without PV feed-in. However, because of the optimization process, the original topology can be altered at all times.

An interesting finding is that the original switching states can still be observed, since initial closed switches stay closed in the majority of time steps and vice versa. Apart from that, switch G39–G66 proves to be a more favorable choice than G18–G135 to supply the subnet of nodes G35 to G51 over multiple time steps. Furthermore, the switching behavior confirms the effectiveness of ring network prevention: with switch G13–G152 remaining nearly permanently closed, switches G18–G135 and G39–G66 operate in a mutually exclusive manner to avoid forming a closed loop among those three switches.

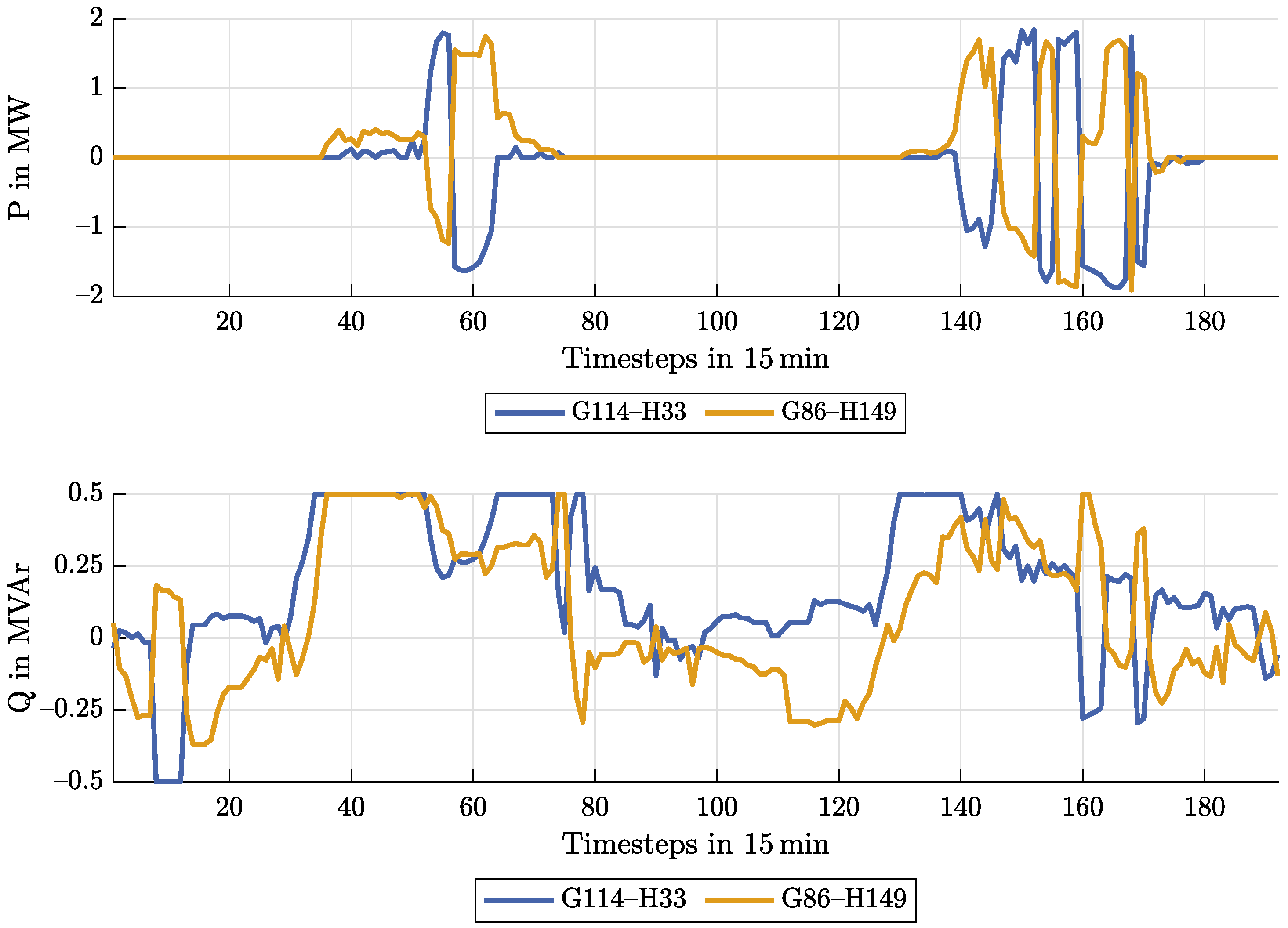

In contrast to the usage of MVDC connections, the switches connecting both networks, G114–H33 and G86–H149, are not permanently closed at times with PV feed-in, since the AC switches cannot enable continuous power flow between the MV networks, unlike the MVDC connections. As a consequence, the transferred power is reduced to 97.13%.

The results shown in

Table 5,

Table 6,

Table 7 and

Table 8 differ depending on whether an open ring structure is allowed or not. As mentioned in

Section 2.2.2, the MVDC couplings do not play a role in the consideration of the ring structure, which can consequently be seen in the results. When using MVDC couplings alone, without simultaneous AC switching, there are no differences in the results between the open- and closed-ring structures.

5.1. Power Transfer Optimization

The results for power transfer optimization are shown in

Table 5 (ring branches not allowed) and

Table 7 (ring branches allowed). For all scenarios, the losses have been reduced if the value of sub-objective

was set to 1. Scenario 2 (c), with closed-ring structures and a PV penetration of 100%, achieved the best performance by reducing the power transfer by 8.75%.

In general, it can be said that operating in Scenario 2, the closed-ring structure enables a more effective minimization of the transferred power. Scenario 1 (c) performs approximately 1 to 1.5 percentage points worse than Scenario 2 (c) across all levels of PV penetration in the case of closed-ring configurations.

But when it comes to Scenario (a), both technologies are on a comparable level. Thus, the two optimization criteria pose a greater challenge for the AC switches than for the MVDC.

The combination of both technologies in Scenario 3 (a) leads to nearly the same result as the best result from Scenario 1 (a) and 2 (a): with an open-ring structure, it is comparable to the MVDC and with no enforcement of the open-ring structure, it is close to the result of the AC switches. For sub-scenario (b), where the aim was only to reduce the losses, the power transfer could be slightly reduced, but mostly less than 1%. Only for Scenario 1 and 2 (b) and a PV penetration of 200%, the transferred power increased.

5.2. Minimization of Power Losses

In

Table 6 and

Table 8, the results for the minimization of power losses are shown. Scenario 3 (b) containing MVDC and AC switching, and closed-ring structures achieved the best loss reduction. For example, for a PV penetration of 100% the losses were reduced by 33.73%, which is a massive improvement in terms of transmission efficiency.

In general, allowing closed-ring branches leads to a higher loss reduction when AC switching is included (Scenario 2 and 3). While Scenario 1 with the MVDC is comparable to Scenario 2 and 3 in open-ring structures, the optimization potential of Scenario 2 and 3 with the allowance of closed rings is for all PV penetrations more than 10 percentage points higher than in Scenario 1.

While most Scenarios have their highest optimization potential at 100% PV penetration, Scenarios 1 and 2, in combination with forbidden closed rings, perform best at 200% PV penetration.

For Scenarios 1 (c) and 2 (c) in closed-ring structures, the reduction in the transferred power leads to significantly higher losses as shown in

Table 8.

6. Conclusions

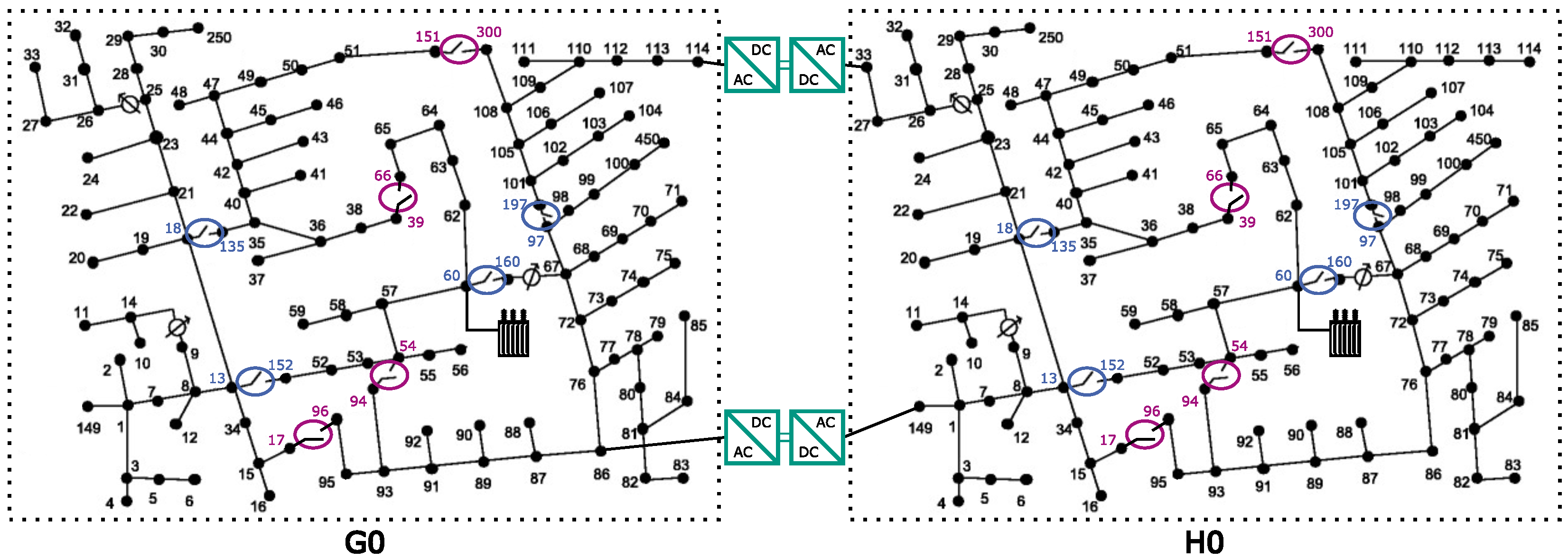

In this paper, the PSO algorithm was applied to a multi-objective optimization problem for the distribution network reconfiguration of a modified IEEE-123 test feeder to investigate the potential application of active and passive grid coupling and their combination. Therefore, two MV networks next to each other were connected by two MVDC connections or AC switches. In addition, several AC switches were used to optimize the grid topology. The results of different scenarios are promising. With a high PV penetration of 100%, where every customer has a PV feed-in, the algorithms and technologies are able to optimize the grid topology with respect to the sub-objectives. The results differ depending on the scenario and the given sub-objectives. In general, allowing closed-ring structures enables a more effective optimization potential than the constraint of a radial grid topology. When aiming for a minimization of power transfer and a minimization of power losses, the combination of MVDC and AC switching performs best in a closed-ring structure.

The direct continuation of this work is the scheduling of selected passive or active coupling elements. The switching state optimization concept was based on ideal switching operations and did not consider dynamic effects within the grid. The method can be applied by incorporating real-time measurements of generation units, as well as load data received, for example, from smart meter measurements, into the operating strategy of real distribution grids. However, before practical implementation, the resulting switching sequences must be examined and compared with operational limitations, such as permissible circulating currents, or assumptions in the protection scheme.