Abstract

Zn-based ternary deep eutectic solvents (TDESs) have attracted significant attention due to their good biodegradability, stability, and sustainability. In this work, TDESs composed of choline chloride:urea (ChCl:U) and zinc salts, ZnCl2, Zn(CH3COO)2, and ZnSO4 were synthesized and characterized by Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy and laser desorption ionization mass spectrometry (LDI MS). Their antibacterial activity against cariogenic Streptococcus species isolates was determined by microdilution assay, while their cytotoxic potential and effect on the intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) induction were analyzed on the MRC-5 fibroblast cell line by XTT, trypan blue, and DCF assays, respectively. FTIR confirmed that hydrogen bonds prevail in the molecular structure of ChCl:U:Zn salts, while LDI MS revealed the interactions between zinc salts and ChCl:U. The antibacterial TDES potential was high, especially against Streptococcus sanguinis, with ChCl:U:ZnCl2 displaying the most promising effects (MICs 1.13–18.12 µg/mL). Cytotoxicity assessment showed that concentrations up to 100 µg/mL of all TDESs did not display significant cytotoxicity, while higher concentrations significantly reduced cell viability by increasing ROS production and cell membrane damage, outlining the safety window of up to 100 µg/mL. Strong antibacterial activity of low TDESs concentrations combined with their good biocompatibility highlights their potential as innovative candidates for biomedical application.

1. Introduction

The development of green solvents with enhanced properties represents a novel approach in different fields of science, including pharmaceuticals and chemicals development, but also biomedical fields, including dentistry [1,2,3]. Deep eutectic solvents (DESs) are classified as a type of ionic fluids composed of two or three substances capable of self-association to form a eutectic mixture with a melting point lower than each substance. DESs are now commonly recognized as a new family of ionic liquids; they have numerous similarities and differences with ionic liquids, but also possess catalytic properties [4,5]. Considering their intrinsic properties, such as low toxicity, simple synthesis, high biocompatibility, and antibacterial properties, their potential biomedical applications in various fields, including drug delivery systems, solvents for natural compounds extraction, and nanomaterial synthesis and functionalization, have been explored in recent years [6,7,8].

The reported antimicrobial activity of some DESs outlined their potential use for therapeutic and preventive applications [9]. Choline chloride-based DESs showed antimicrobial activity against a number of drug-resistant bacteria, fungi, and viruses, including Staphylococcus aureus, Candida albicans, and herpes simplex virus [10]. The antibacterial potential of DESs against oral bacteria such as Enterococus faecalis and Porphyromonas gingivalis was also reported [11,12]. Additionally, research on the cytotoxic profile of choline chloride-based DESs, especially choline chloride:urea (ChCl:U), demonstrated low cytotoxic potential and good biocompatibility, while maintaining antibacterial activity, marking their potential for therapeutic application [13,14,15,16].

Despite continuous advances in oral health care, caries prevention and treatment remain a challenge in many parts of the global population [17]. Mechanical methods such as tooth brushing and flossing are insufficient per se, and the efficacy of commonly used adjuvants against oral bacteria remains controversial, with reports ranging from beneficial to negligible effects [18]. Although chlorhexidine has long been regarded as the gold standard for chemical plaque control due to its strong antibacterial activity, its clinical application is restricted by side effects such as taste alteration, xerostomia, and tooth discoloration [19]. These limitations underscore the need for next-generation antimicrobial formulations that can be safely and effectively incorporated into daily oral hygiene practices.

Even though the antimicrobial activity and good biocompatibility of choline chloride and urea-based DESs have been reported, the addition of a third component—such as a plant extract, metallic nanoparticles, or metal salts—contributes to an enhanced antimicrobial effect [20]. This enhancement is primarily attributed to the intrinsic antimicrobial activity of the third incorporated component. Our previous research indicated that ChCl:U possesses excellent biocompatibility and moderate antibacterial activity against Streptococcus mutans and Streptococcus sanguinis, the two most prevalent bacterial strains involved in the development of dental cavities [13]. However, the antibacterial effects were stronger for DES-formulated sage extracts, confirming the contribution of the third component in the DES solution, such as the plant extract with antibacterial properties, to the overall antibacterial effect. The enhanced antibacterial activity of ternary DESs (TDESs) likely results from improved solubilization of bioactive compounds, increased membrane permeability, and synergistic interactions between DES components and incorporated antimicrobial agents. These ternary formulations represent promising green alternatives for developing antimicrobial applications in pharmaceutical and biomedical fields. The TDES composition’s tunability enables deep eutectic solvents to remain environmentally acceptable while optimizing their antibacterial activity.

Zinc is an essential trace element with pivotal roles in enzymatic processes in human and bacterial cells; nevertheless, it also possesses antibacterial properties when applied at higher concentrations. Different water-soluble zinc (Zn) salts are often used as active ingredients in dental hygiene products to inhibit dental plaque and control calculus formation [21,22], and incorporated into dental materials to inhibit the growth of cariogenic bacteria [23]. The antibacterial effect of Zn salts is achieved by the release of Zn ions (Zn2+) that increase the permeability of bacterial cell membranes, interfere with bacterial enzymatic processes, and affect bacterial cell division [23,24,25]. The antibacterial effect is mostly dependent on the concentration of Zn2+ ions, as well as the solubility of the salts, where zinc chloride, zinc sulfate, and zinc acetate were found to be the most effective in inhibiting bacterial growth of Streptococcus mutans, Streptococcus sobrinus, Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli, and Enterococcus faecalis [23,25,26,27]. However, despite being essential for a plethora of physiological and biochemical functions in the human body, zinc belongs to the heavy metals, which are known to cause severe toxic effects on human cells, mostly mediated by generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), interfering with DNA and nuclear proteins, and inhibiting enzymatic processes [28]. High concentrations of zinc could exhibit toxic effects by elevating ROS through the induction of mitochondrial dysfunction [29], depleting cellular glutathione (GSH) and adenosine triphosphate (ATP) levels, and inducing necrosis and apoptosis [30]. Therefore, designing new formulations that could preserve the antibacterial activity of zinc salts, while mitigating cytotoxic effects on human cells, could be of great importance for future dental applications.

Bearing in mind the aforementioned potential of choline chloride and urea-based DESs and Zn salts, this work aimed to describe the synthesis and chemical characterization of Zn-based ternary choline chloride:urea deep eutectic solvents and to explore their antibacterial potential against cariogenic Streptococcus species isolates. To the best of our knowledge, the antibacterial properties of DESs composed of choline chloride, urea, and three different Zn salts, namely zinc chloride, zinc sulfate, and zinc acetate, against cariogenic bacteria, along with their cytotoxic profiles, has not been previously reported. Even though zinc ions at low concentrations are naturally present in saliva and enamel, and are generally considered safe for oral tissues and commonly used in dental products, higher concentrations or prolonged exposure may cause local irritation [22], and the effects of zinc-containing TDESs on oral tissues have not been systematically studied. Therefore, a cytotoxicity assessment of DESs was performed to determine the range of safe concentrations that possess antibacterial effects.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Synthesis of DESs

DESs were prepared by mixing choline chloride (Acros Organics, Waltham, MA, USA, purity 99%), urea (Sigma Aldrich, purity ≥ 99.5%), and different zinc salts as additives: ZnSO4×7H2O, ZnCl2 (purity ≥ 99.995%), and Zn(CH3COO)2×2H2O (Zn-acetate, all obtained from Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) in a 1:2:0.25 molar ratio at 60 °C for 6 h. After their mixing on a magnetic stirrer, the transparent molecular liquids were formed. To remove any remaining water from the synthesized liquids, which might still be present due to zinc salts, a rotary evaporator was used (IKA Rotary Evaporators, RV8, Staufen, Germany). The pH of the pure synthesized DESs was measured on the 713 pH Meter (Metrohm, Riverview, FL, USA), and the obtained DESs materials were denoted in Table 1. The pH values of DESs were also measured upon dissolving in cell culture medium (DMEM, Gibco™, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), to assess the impact of pH on cellular survival.

Table 1.

DESs composition, designation, molar ratio, and pH values (pure and DESs dissolved in cell culture medium).

2.2. Characterization of DESs

2.2.1. FTIR

Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy was conducted as previously described [13,31] using a Nicolet iS5 FTIR spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). The FTIR spectra of all the investigated DESs were measured in the range of 4000–400 cm−1 with a resolution of 4 cm−1, employing the Attenuated Total Reflection (ATR) technique.

2.2.2. LDI MS

The laser desorption ionization mass spectrometry (LDI MS) measurements (without the use of conventional matrices) were carried out on a commercial MALDI Voyager-DE PRO mass spectrometer from Sciex (Foster City, CA, USA) equipped with a time-of-flight (TOF) mass analyzer according to the previously described procedure [32]. This mass spectrometer contains an ultraviolet nitrogen laser with wavelength of 337 nm, pulse width of 3 ns, and repetition rates of 20.00 Hz.

The mass spectra shown in this work were performed in the negative reflectron mode. The other instrumental parameters were accelerating voltage 25,000 V, grid voltage 84%, laser intensity 3363 a.u., and number of laser shots 500, and a delayed extraction time of 100 ns.

For LDI analysis, a small volume (1 μL) of sample was applied directly to the stainless steel sample plate without any preparation. The sample was smeared onto this plate and directly introduced into the instrument.

2.3. Antibacterial Activity Assessment

2.3.1. Bacterial Strains

Clinical isolates belonging to Streptococcus species, i.e., Streptococcus mutans, Streptococcus mitis, Streptococcus sanguinis, and Streptococcus gordonii, were obtained from the Department of Pediatric and Preventive Dentistry, School of Dental Medicine, University of Belgrade, Republic of Serbia. Bacterial collecting and identification was undertaken according to the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethical Committee No 36/7. The identification of clinical isolates was performed according to the standard procedures [33,34], as previously described and reported [35]. The clinical isolates were stored at −80 °C at the Microbiology department of the “Vinča” Institute of Nuclear Sciences—National Institute of the Republic of Serbia, University of Belgrade, and designated as the following strain numbers within the depository: Streptococcus mutans strain number 142, Streptococcus mitis strain number 062, Streptococcus sanguinis strain number 132, and Streptococcus gordonii strain number 057.

2.3.2. Bacterial Cultivation

Cultivation was performed on Blood Agar plates (BA, Torlak, Serbia) by streaking frozen stock cultures and 48 h incubation at 37 °C. Colonies of all tested strains were inoculated into Luria–Bertani Broth (Tryptone 10.0 g/L, Yeast extract 5.0 g/L, Sodium chloride 10.0 g/L, LB, HiMedia, Mumbai, India) and grown overnight at 37 °C prior to each experiment. Cell suspensions turbidity was adjusted spectrophotometrically to an optical density OD600 of 0.2 (corresponding to 1 × 108 CFU/mL).

2.3.3. Assessment of Antibacterial Activity Using Microdilution Assay

Minimal inhibitory concentrations (MICs) were determined by the microdilution method in 96-well microtiter plates, as previously described in Diouchi et al. [36]. Four test substances were two-fold diluted in Tryptone Soya Broth (casein peptone Torlak 17.0 g/L, Soya peptone 3.0 g/L, Dextrose 2.5 g/L, Sodium chloride 5 g/L, Dipotassium hydrogen phosphate 2.5 g/L, TSB, Himedia, Mumbai, India) along the rows, and the tested concentration ranges were 0.29–600 µg/mL, 0.29–595 µg/mL, 0.28–580 µg/mL and 0.27–550 µg/mL for ChCl:U:Zn(CH3COO)2, ChCl:U:ZnSO4, ChCl:U:ZnCl2, and ChCl:U, respectively. In this assay, mouthwash based on 0.2% chlorhexidine (CHX) with CHX in a concentration range 2–106 µg/mL was also tested, as commonly used formulation in dentistry. Inocula were adjusted to 2 × 104 CFU/well, and the plates were incubated at 37 °C for 24 h in microaerophilic conditions. A growth indicator, resazurin, was added to determine MICs. Minimal bactericidal concentrations (MBCs) were detected by additional plating of 20 μL from the wells with no visible growth onto BA. The experiment was performed in triplicate and repeated twice.

2.4. Cytotoxicity Assessment

2.4.1. Cell Culture and Treatment

Commercially available human fetal lung fibroblast cell line MRC-5 (CCL-171) was used for the cytotoxicity assessment (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA). Briefly, the cell cultures were grown in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM, Gibco™, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS, Capricorn Scientific, Germany) and 1% antibiotic-antimycotic (Gibco™ Antibiotic-Antimycotic, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA), under standard cell culture conditions, i.e., humified atmosphere at 37 °C and 5% CO2. The cell cultures were treated with a range of DESs concentrations: 50, 100, 300, and 500 μg/mL for 24 h. Untreated cultures served as a negative control; all treatments were set up in triplicate and experiments were repeated twice.

2.4.2. Viability Assays (XTT and Trypan Blue Exclusion Assay)

The cell viability assessment was performed by applying 2,3-Bis-(2-Methoxy-4-Nitro-5-Sulfophenyl)-2H-Tetrazolium-5-Carboxanilide (XTT) assay according to the standard procedure [37]. Briefly, cells were seeded in the 24-well plates at a density of 0.05 × 106, allowed to adhere for 24 h, and treated with DESs previously dissolved in DMEM and filtered through a 0.22 µm Millipore filter (Merck Millipore, Darmstadt, Germany). Then, 24 h after the treatment, cell culture media was discharged and the cells were supplemented with XTT reagent activated with phenazine methosulfate (PMS) and placed at 37 °C, until the color developed. Absorbance was measured at 470 nm on a microplate reader (Sunrise, Tecan Group Ltd., Männedorf, Switzerland). The results are presented as a percentage of viable cells compared to untreated control, i.e., ratio between the absorbance of treated and untreated cells.

To assess the impact of the treatments on the cell membrane, we also performed a trypan blue exclusion (TB) assay following the procedure described by Strober [38]. The cells were seeded in 24-well plates at the same densities as for the XTT assay. Upon the treatment in the same manner as for the XTT assay, the cells were detached from the wells using trypsin-EDTA (Capricorn Scientific, Ebsdorfergrund, Germany) and blocked with the same volumes of complete medium. Equal volumes of MRC-5 cell suspensions and 0.4% trypan blue dye were mixed, applied to a hemocytometer (Cambridge Instruments Inc., Buffalo, NY, USA), and counted using a light microscope (Optech, Gmbh, Munchen, Germany) with 40· magnification objective. Cell viability was expressed as a percentage of viable cells compared to the untreated control (100%).

2.5. Intracellular ROS Production (DCF Assay)

Determination of intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) production was assessed by employing cell-permeable 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA) staining as previously described [39]. The protocol is based on the use of DCFH-DA that oxidizes to fluorescent DCF (dichlorofluorescein) by ROS. Briefly, the cells were seeded in 96-well plates at a density of 2.5 × 104 cells per well and allowed to adhere for 24 h. Upon adhering, the cells were treated with DCFH-DA (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) for 45 min at 37 °C in the dark, washed with 1xPBS, and treated with DESs. The fluorescent measurements were performed by measuring excitation absorbance and emission absorbance at 485 nm and 535 nm wavelengths, respectively, on the microplate reader Wallac Victor2 1420 Multilabel Counter (Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA, USA). Treatment with hydrogen peroxide (300 µM) served as a positive control.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Results are presented as mean value ± standard error of mean (SEM). Statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS 10 statistical package for Windows (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). A one-way ANOVA statistical test was used for the analysis, whereas p value < 0.05 were accepted as the level of significance.

3. Results

3.1. Characterization of DESs

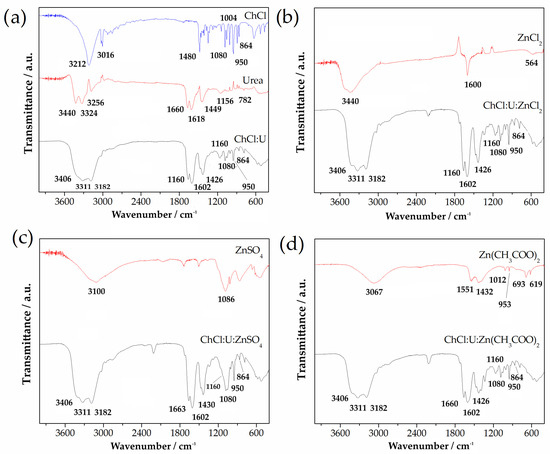

3.1.1. FTIR Analysis of DESs

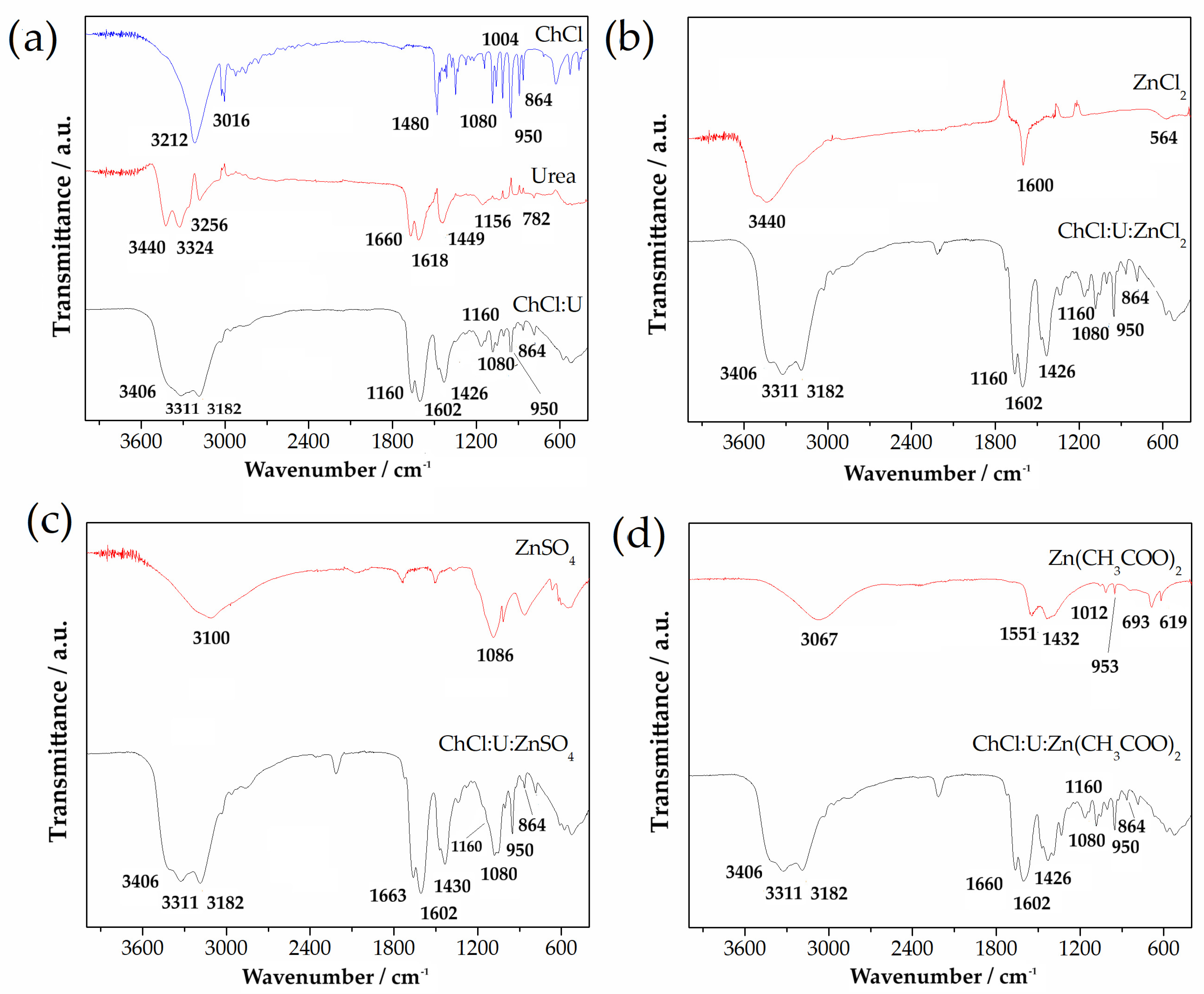

Figure 1a shows the ATR-FTIR spectra of choline chloride (ChCl), urea (U), and choline chloride:urea (ChCl:U) DES. It can be seen that spectrum of ChCl:U overlapped with spectra of choline chloride and urea. In the ChCl spectrum, there were several characteristic bands located at 3212 cm−1 and 3016 cm−1 associated with OH vibrations. Bands positioned at 1480 cm−1, 1080 cm−1, 1004 cm−1, 950 cm−1, and 864 cm−1 can be assigned as CH3, CH2, C-O, CCO, and N-CH3 vibration bands, respectively. On the other hand, the spectrum of urea showed the absorption bands in the investigated IR region, which can be ascribed to the υas NH2, υs NH2, δas NH2, and δs NH2 vibrations. Vibrations at positions of 1156 cm−1 and 782 cm−1 can be assigned as υas CN and ω C=O. The spectrum of ChCl:U DES adsorption bands of urea, especially the bands in the region between 3600 and 3000 cm−1, were moved towards the lower wave number region, which implies that hydrogen bonds were formed between urea and ChCl.

Figure 1.

ATR-FTIR spectra of (a) choline chloride, urea, and binary DES ChCl:U, and different Zn salts and ternary DESs (b) ZnCl2 and ChCl:U:ZnCl2; (c) ZnSO4 and ChCl:U:ZnSO4, and (d) Zn(CH3COO)2 and ChCl:U:Zn(CH3COO)2.

ATR-FTIR spectra of Zn salts and ternary DESs are presented at Figure 1b–d. In the case of all Zn salts, there was a broad band located in the region 3000–3450 cm−1, as well as a band at 1600 cm−1, only in the case of ZnCl2. ZnCl2 showed a band below 600 cm−1, which can be attributed to the vibration of metal halide (Zn-Cl, Figure 1b). ATR-FTIR spectrum for ZnSO4 (Figure 1c) showed vibration at a position of 1086 cm−1, associated with SO4. In the spectrum of Zn(CH3COO)2 in Figure 1d, all bands were associated with Zn(CH3COO)2.

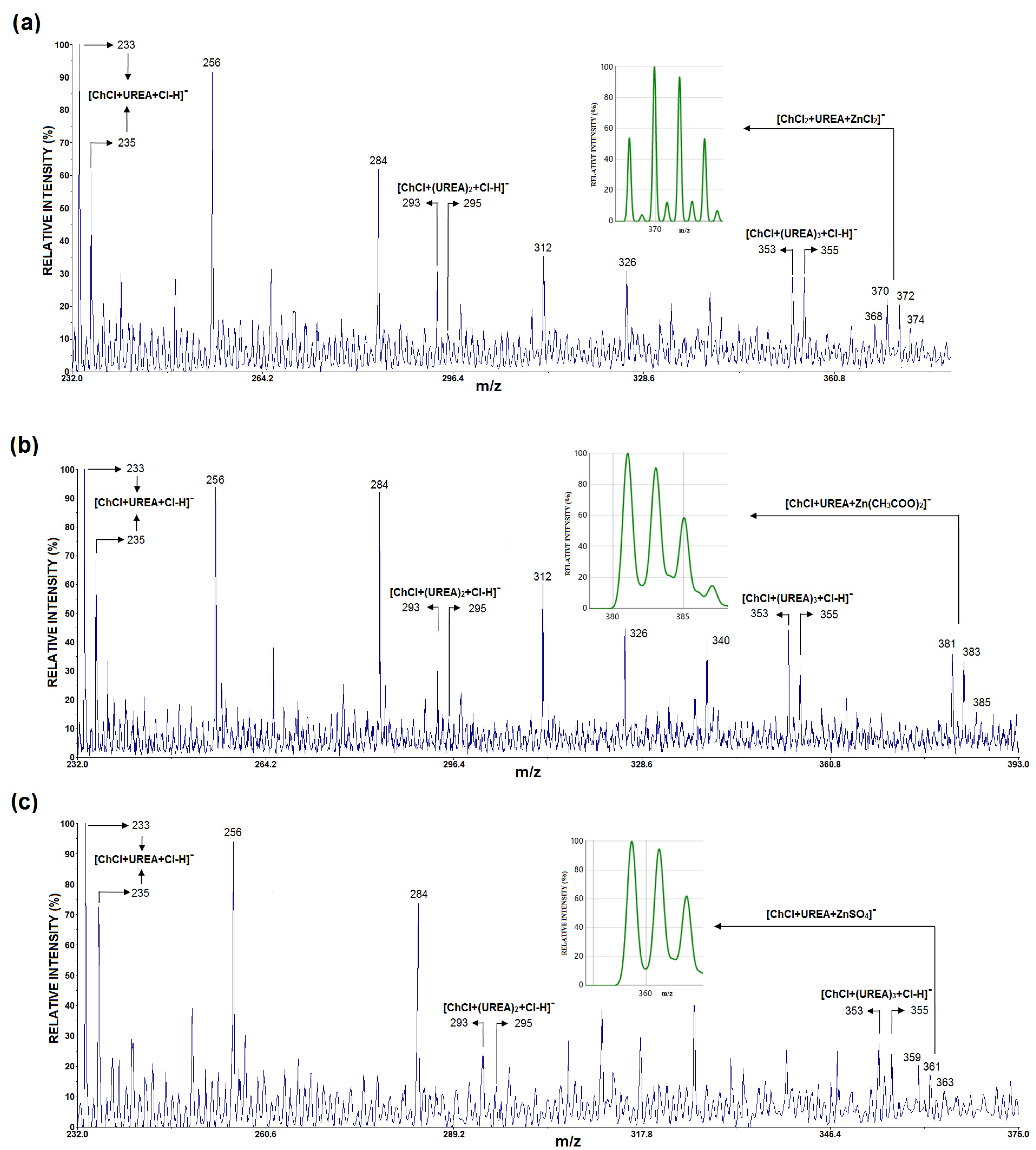

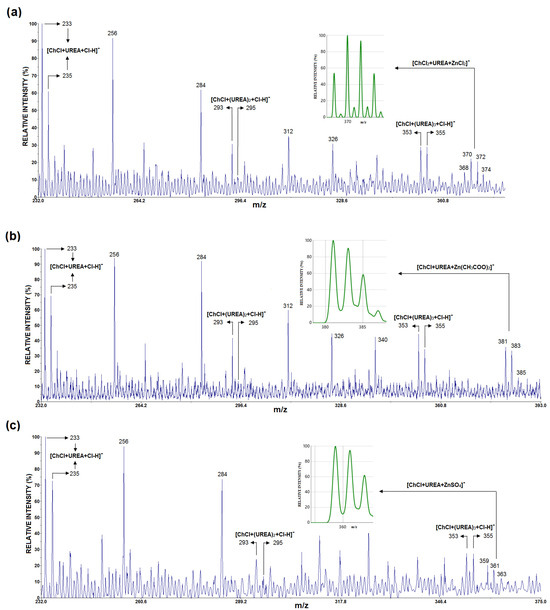

3.1.2. LDI MS

Figure 2a–c show the LDI mass spectra in the negative mode of ChCl:U:ZnCl2, ChCl:U:Zn(CH3COO)2, and ChCl:U:ZnSO4, respectively. In the LDI mass spectrum of all three samples, peaks corresponding to deprotonated chloride adducts of one cholinium chloride unit and one, two, and three urea molecules (U) were detected, e.g., [ChCl + U + Cl-H]− (at m/z 233.18, 235.19, calcd 233.07, 235.07), [ChCl + U2 + Cl-H]− (at m/z 293.52, 295.43, calcd 293.11, 295.11), and [ChCl + U3 + Cl-H]− (at m/z 353.37, 355.31, calcd 353.13, 355.13). Moreover, the signal of [ChCl + U + Cl-H]− in all three graphs was more intense than the peaks where ChCl associated with two and three urea molecules, such as [ChCl + Un + Cl-H]− (n = 2 and 3). In addition, low intensity peaks around m/z 370 (Figure 2a), m/z 381 (Figure 2b), and m/z 359 (Figure 2c), can be assigned as [ChCl+U+Cl+ZnCl2]− (at m/z 367.69, 369.67, 371.67, 374.64, calcd 367.94, 369.93, 371.93, 374.93), [ChCl+U+Zn(CH3COO)2]− (at m/z 381.44, 383.43, 385.31, calcd 381.06, 383.06, 385.06), and [ChCl+U+ZnSO4]− (at m/z 359.49, 361.48, 363.38, calcd 358.98, 360.98, 362.98), respectively.

Figure 2.

The LDI MS of (a) ChCl:U:ZnCl2, (b) ChCl:U:Zn(CH3COO)2, and (c) ChCl:U:ZnSO4, with the theoretical isotopic distributions for [ChCl+U+Cl+ZnCl2]−, [ChCl+U+Zn(CH3COO)2]−, and [ChCl+U+ZnSO4]− shown in (a–c), respectively.

3.2. Antimicrobial Activity of DESs

Minimal inhibitory concentrations of three eutectic mixtures with Zn salts was generally high (MICs ranged 1.17–18.75, 1.16–37.19, and 1.13–18.12 µg/mL for ChCl:U:Zn(CH3COO)2, ChCl:U:ZnSO4, and ChCl:U:ZnCl2, respectively) and comparable to both the positive control and commonly used mouthwash based on 0.2% chlorhexidine. MIC values were lower for all three ternary Zn-based DESs, compared to their binary counterpart, ChCl:U, indicating enhanced antibacterial activity of ternary solvents. Among the tested DESs, the most potent against all tested strains was ChCl:U:ZnCl2. A similar trend was observed for MBCs. Considering the difference in strain sensitivity, slight differences in sensitivity can be observed, with S. sanguinis isolate being the most sensitive (Table 2).

Table 2.

Antibacterial activity of investigated deep eutectic solvents against four isolates belonging to the genus Streptococcus.

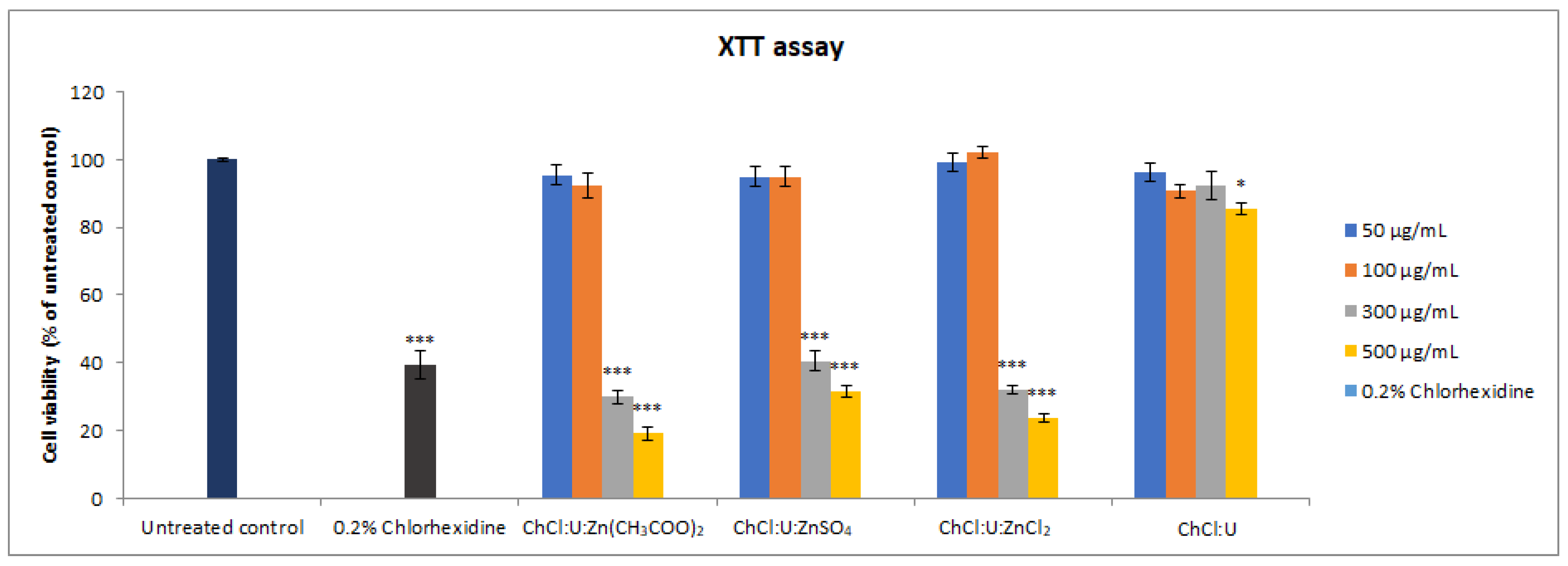

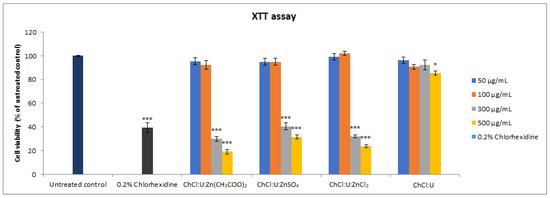

3.3. Cytotoxicity of DESs

The cytotoxicity of all deep eutectic solvents was assessed by XTT and trypan blue assays. The results of the XTT assay showed that lower concentrations (50 and 100 µg/mL) of all DESs did not display significant cytotoxic effects compared to the untreated control. However, higher concentrations (300 and 500 µg/mL) of ChCl:U:Zn(CH3COO)2, ChCl:U:ZnSO4, and ChCl:U:ZnCl2 displayed statistically significant cytotoxicity (Figure 3, p < 0.001) in a concentration-dependent manner. ChCl:U showed cytotoxicity only at the highest tested concentration of 500 µg/mL (p < 0.05).

Figure 3.

Cell viability of MRC-5 cells treated with different concentrations (50–500 µg/mL) of DES assessed by XTT assay. Level of significance: * p < 0.05, *** p < 0.001.

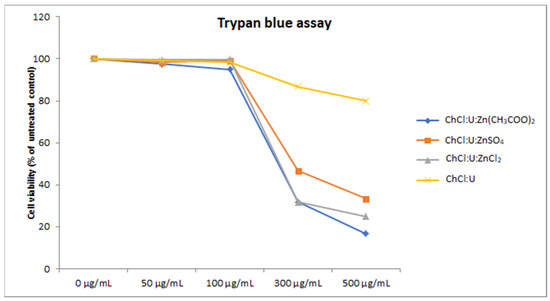

When the effects of the same concentrations of different treatments were compared, ChCl:U showed the mildest cytotoxicity compared to other treatments, i.e., only the highest tested concentration (500 µg/mL) was significantly cytotoxic and reduced the percentage of viable cells to 85.57%. The same concentration of other treatments markedly reduced cell viability, ranging from 19.11% (ChCl:U:Zn(CH3COO)2) to 31.34% (ChCl:U:ZnSO4) (p < 0.001). Concentration of 300 µg/mL was cytotoxic for ChCl:U:Zn(CH3COO)2, ChCl:U:ZnSO4, and ChCl:U:ZnCl2, but there was no statistical significance between the treatments with different Zn-based DESs. However, compared to ChCl:U treatment at the same concentration, these treatments displayed significantly higher cytotoxicity (p < 0.001).

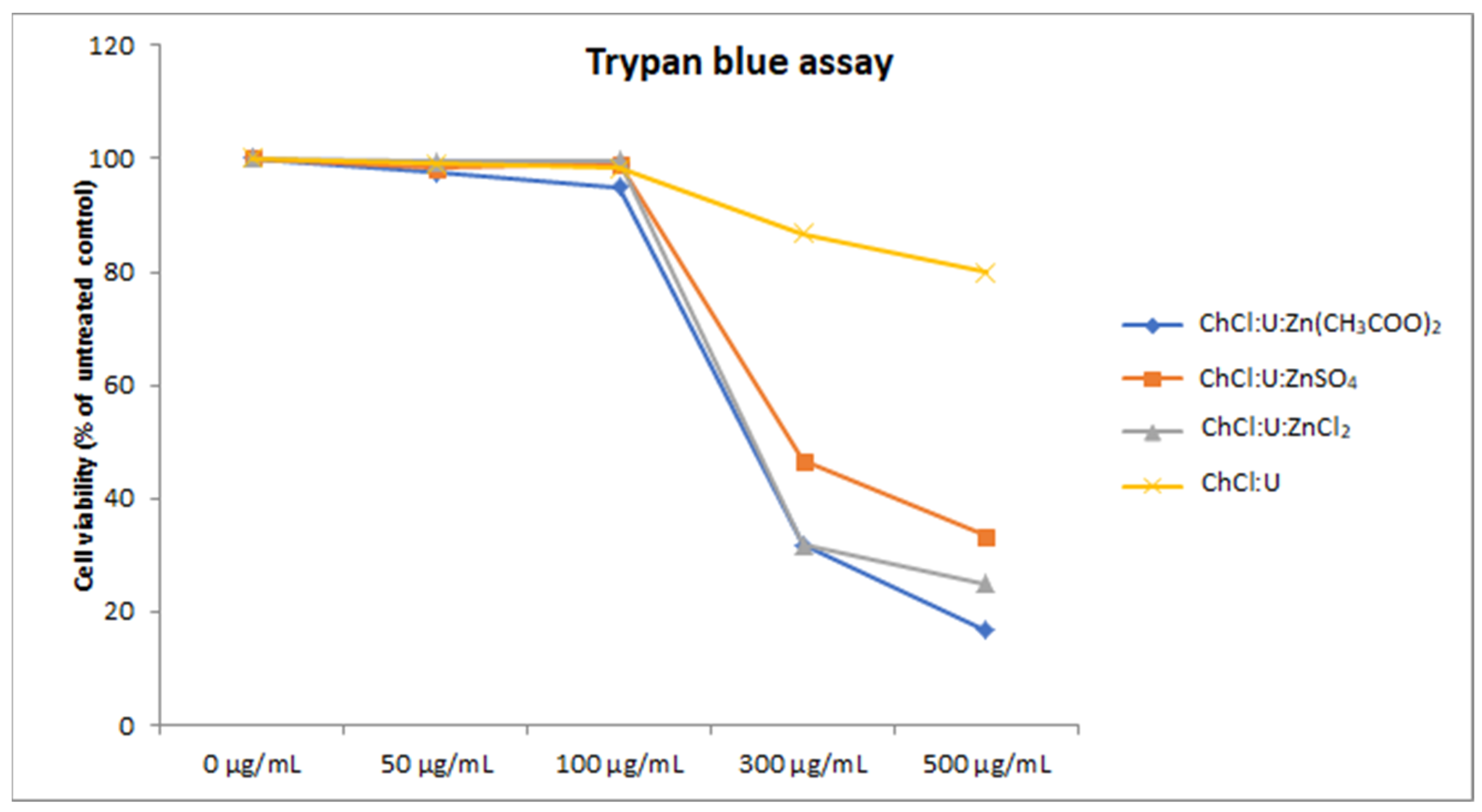

To confirm the results of XTT assay, we also employed trypan blue staining on the treatments. Unlike the XTT assay, which is based on the measurement of cellular metabolism in the living cells [40], trypan blue dye penetrates the damaged cell membrane of the dead cells [38]. The results obtained by trypan blue staining showed a similar trend to the XTT assay (Figure 4), outlining the safety window of zinc-based TDESs of up to 100 µg/mL.

Figure 4.

Cell viability of MRC-5 cells treated with different concentrations (50–500 µg/mL) of DES assessed by trypan blue assay.

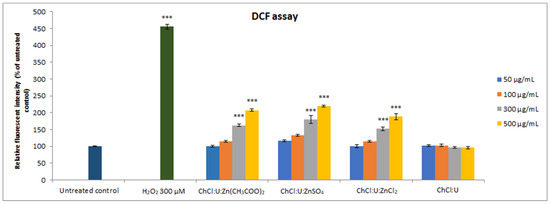

3.4. Intracellular ROS Production

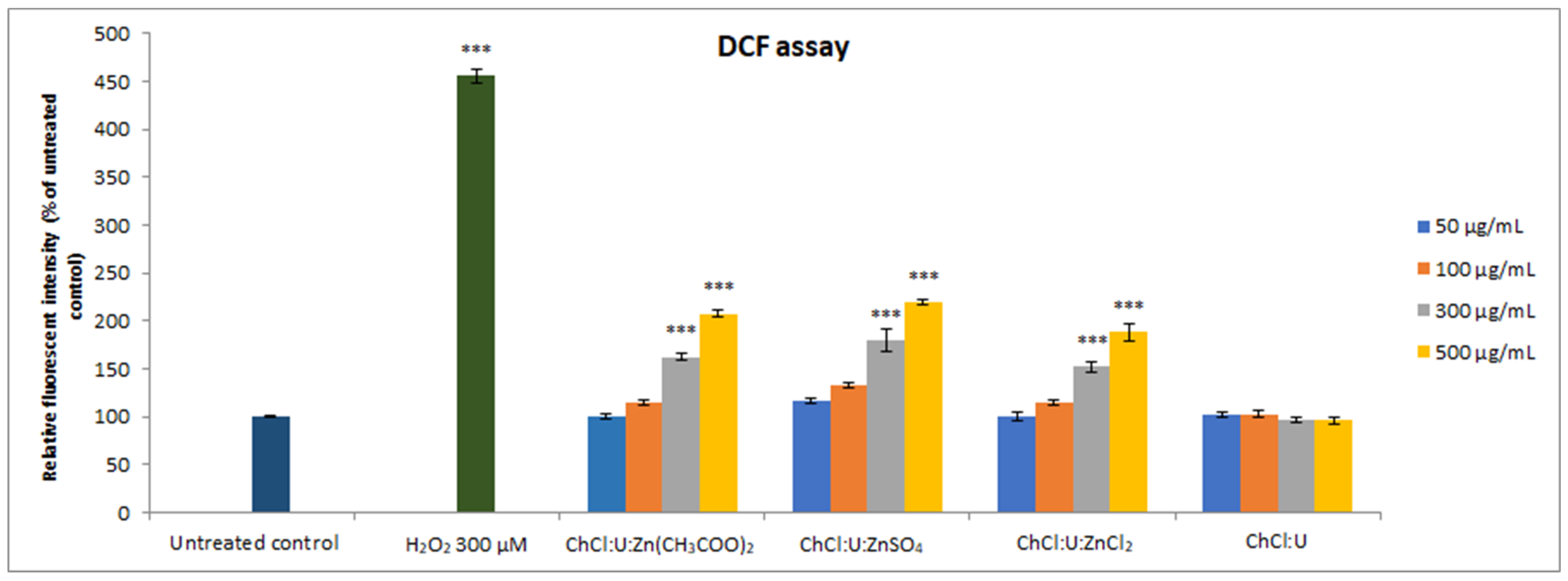

DCF assay was used to assess the impact of the obtained DESs on the intracellular ROS production. The results demonstrated that lower concentrations (50 and 100 µg/mL) of all tested DESs did not significantly increase ROS production compared to the untreated control, while higher concentrations of zinc-based DESs led to a significant elevation in intracellular ROS production (Figure 5, p < 0.001). The intracellular ROS levels upon all concentrations of ChCl:U treatment were in the range of the untreated control, while levels of zinc-based DESs induced ROS production in a concentration-dependent manner, as presented in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Intracellular ROS production in MRC-5 cells treated with different concentrations (50–500 µg/mL) of DES assessed by DCF assay. Positive control was 300 µM H2O2. The results are presented as a percentage of untreated control. Level of significance: *** p < 0.001.

4. Discussion

Zn-based ternary deep eutectic solvents have attracted significant research interest recently, especially for industrial applications, such as zinc-ion battery production and wastewater treatment. These solvents exhibit advantageous properties such as tunable ionic conductivity, biodegradability, stability, and affordability, which make them promising candidates for use in energy storage systems and selective metal ion recovery from industrial effluents [41,42]. Although the synthesis of DESs based on choline chloride and Zn salts has been previously reported, either as binary (for zinc acetate) or ternary (for zinc sulfate and zinc chloride) DESs [43,44,45,46], to the best of our knowledge, their antibacterial potential and cytotoxicity profiles, as well as their potential role in biomedicine, especially in caries prevention, have not been evaluated. Meng et al. (2024) reported the antibacterial effects of a ternary deep eutectic solvent composed of glycerol, zinc chloride, and choline chloride against the bacteria in infected wounds [47], but to the best of our knowledge, the antibacterial properties of DESs composed of choline chloride, urea, and three different Zn salts, namely zinc chloride, sulfate, and acetate, against cariogenic bacteria has not been previously reported. Though zinc itself is integrated into various dental materials and adhesives due to its antimicrobial and biocompatible properties, the specific application of Zn-based DESs as functional agents or solvents in dental formulations or therapies has not yet been investigated. Concerning the necessity of caries prevention, this study was guided by the idea that these materials may be used as the active principle within the formulation that can be integrated into the oral hygiene routine.

Regarding the characterization of these ternary eutectic solvents, the ATR-FTIR spectrum of ChCl:U resulted from the overlapping spectra of choline chloride and urea. The assignment of characteristic bands at 3212 cm−1 and 3016 cm−1 at 1480 cm−1, 1080 cm−1, 1004 cm−1, 950 cm−1, and 864 cm−1, as well as vibrations at 1156 cm−1 and 782 cm, was consistent with the results presented by Li et al. [48]. Assignation related to Zn salts and ternary DESs was also in agreement with previously reported results [49,50,51]. The band at 1600 cm−1, which appeared only in the case of ZnCl2, could be attributed to OH- stretching and H–O-H vibrations of water trapped from environmental exposure. Further, results of the current study indicated that the molecular structure of the binary DES consisting of choline chloride and urea did not change after adding a third component, i.e., the Zn-based salts. The spectra of ternary DESs (ChCl:U:ZnCl2, ChCl:U:ZnSO4 and ChCl:U:Zn(CH3COO)2) were almost the same as the spectrum of the binary DES consisting of ChCl:U. The bands in the investigated IR- region (4000–400 cm−1) for all ternary DESs were at the same positions as in the case of ChCl:U. This indicates that the molecular structure of the binary DES consisting of choline chloride and urea was unchanged after adding a third component, i.e., Zn-base salts. Therefore, the most powerful bonds between choline chloride and urea, which were responsible for the formation of eutectic mixture, were the aforementioned hydrogen bonds [52].

In the LDI mass spectra of ChCl:U:ZnCl2, ChCl:U:ZnSO4, and ChCl:U:Zn(CH3COO)2, characteristic ions of the form [ChCl + Un + Cl-H]− (where n = 1–3) were identified, indicating interactions between ChCl and U. This finding aligns with previous mass spectrometric studies [53] and suggests that LDI MS could be a valuable technique for characterizing deep eutectic solvent (DES) samples. Additionally, low-intensity ions such as [ChCl + U + Cl + ZnCl2]−, [ChCl + U + Zn(CH3COO)2]−, and [ChCl + U + ZnSO4]− were also detected in the individual LDI mass spectra of ChCl:U:ZnCl2, ChCl:U:Zn(CH3COO)2, and ChCl:U:ZnSO4, respectively. This suggests a potential interaction between the zinc salt and the ChCl:U mixture.

Regarding the evaluation of antibacterial potential, the isolates of Streptococcus species were selected as model bacteria, since S. mutans is recognized as the main culprit for caries development. On the other hand, although S. mitis, S. sanguinis, and S. gordonii could be considered as commensals [54], they are initial colonizers and have interactions among themselves within plaque formation [55]. The results showed that all eutectic mixtures with Zn-based additives possessed high antibacterial potential. The highest MIC value determined in this study (37.19 µg/mL) against S. mutans is still lower than values determined for solely tested Zn2+, where MIC 128–256 μg/mL [56] and MIC 64 μg/mL [57] were reported. The antibacterial potency of DESs could be attributed to several mechanisms, including increased reactive oxygen species (ROS) production and subsequent oxidation of cell wall macromolecules and destruction of cellular components, as well as membrane damage induced by Zn2+ ions [27,58]. Once released, Zn2+ ions interfere with Mg2+ ions within the bacteria enzymatic systems, leading to their inactivation and bacterial cell death [59]. Recently it was demonstrated that novel water-soluble zinc complexes show pronounced antibacterial activity compared to solely tested Zn salts, possibly due to the adherence to the negatively charged bacterial cell walls, which facilitates membrane permeability and damage [27]. Similarly, the potential of our Zn-based DESs could be caused by choline cation adherence to the polysaccharide chains of the bacterial cell wall through hydrogen bonding or electrostatic interaction [60], which enables more effective Zn2+ penetration through the membrane. Interestingly, slight differences in activity among DESs were observed, with the most potent being ChCl:U:ZnCl2. The highest antibacterial activity of ChCl:U:ZnCl2 is consistent with previous research on antibacterial properties of pure Zn salts against S. mutans and S. sobrinus, where Zn chloride was found to be the most effective, followed by Zn acetate and Zn sulfate [61]. The selective antibacterial properties of different Zn salts are likely a result of their different solubility and ability to release Zn2+ ions [26]. Lower MIC and MBC values obtained in our research might be a result of the complex composition of the obtained ternary DESs, where ChCl:U also possesses intrinsic antibacterial properties, which are enhanced by the addition of Zn salts.

Numerous studies have investigated the biocompatibility of different DESs. While some authors reported their high biocompatibility and low cytotoxic potential [62,63], others reported the opposite [7,14]. Choline chloride DESs are reported to have an overall low cytotoxicity profile, since choline has a significant role in the intracellular metabolism, as a vitamin B component [64]. Cytotoxicity testing clearly outlined the difference between Zn-based and ChCl:U DES, i.e., ChCl:U did not display highly significant cytotoxicity even at the highest tested concentration, unlike all Zn-based DESs, suggesting that Zn2+ ions cause reduced cell viability. ChCl:U did not reduce the percentage of viable cells below 50%, even at the highest tested concentration, indicating high biocompatibility. This is in agreement with the previously reported studies [13,14,62]. The literature data indicate that, among other parameters, pH values of DESs can impact their cytotoxicity rates [65], where acidic DESs typically induce higher toxicity. However, all of the pure DESs obtained in our study had slightly alkaline pHs, with minor differences. Moreover, upon dilution in cell culture medium, the pH values of all DESs were neutral, likely due to the buffer systems in the cell culture media, indicating that minor differences in pH are not the cause of their differing toxicity. Such pH values are advantageous, as they may help neutralize acid production by Streptococcus spp., a key factor in the demineralization process during caries development [66]. Moreover, DES-based formulations with neutral or mildly alkaline pH are not expected to cause erosive changes, in contrast to certain acidic mouth rinses [67]. In addition, salivary enzymes such as amylase, lysozyme, and peroxidases display optimal activity near neutral pH [68]. Therefore, if the application of DESs maintains salivary pH within its physiological range (6.5–7.5), no adverse effects on normal salivary enzyme activity would be expected. The cytotoxicity of Zn-based DES could be explained by dissolution of DES in cell culture medium, where the release of Zn2+ occurs [69]. Even though Zn2+ is an essential trace element for proper cellular functions, such as cell proliferation and differentiation, antioxidative cellular defense, apoptosis, and many enzymatic reactions, excessive concentrations could be detrimental due to the disrupted balance between extracellular/intracellular concentration and higher intracellular uptake [70,71,72]. However, concentrations reported to cause in vitro cytotoxicity depend on the exposure time, cell type, and the form of zinc, i.e., pure salts, nanoparticles, or complexes, and vary significantly from 12 µg/mL for ZnCl2 [70] and 30–100 µg/mL for ZnO nanoparticles [73,74] to up to 135 µg/mL for ZnSO4 [75]. When applied in the pure form, Zn salts display higher toxicity compared to Zn complex compounds [72]. This is in accordance with our research, since Zn-based DESs displayed a significant cytotoxic effect only at the high concentrations—300 and 500 µg/mL. Our results demonstrated that these concentrations of Zn-based DESs significantly increase intracellular ROS production, in contrast to ChCl:U, indicating the pro-oxidant effect of higher TDES concentrations. Previous studies reported that excessive zinc concentrations could increase ROS levels, leading to oxidative stress, which damages cell membranes primarily through lipid peroxidation, which eventually leads to disrupted cell membrane integrity and cell death [29,76]. The trypan blue assay results in our study also confirm this finding, as an increased number of TB-positive cells with damaged cell membrane was found in these treatments.

The minor, statistically insignificant differences in cytotoxicity rates of different Zn-based DESs are likely a result of different Zn salts in the DES structure, as different salts display higher or lower cytotoxicity rates. Pavlica and coworkers [30] demonstrated that Zn sulfate displays high, and Zn chloride and Zn acetate moderate cytotoxicity profiles, due to the distinct release of Zn2+, but the cytotoxicity of all salts was concentration-dependent. Even though Zn-based DES, ChCl:U:Zn(CH3COO)2, ChCl:U:ZnSO4, and ChCl:U:ZnCl2 showed cytotoxic potential at high concentrations (above 100 µg/mL), low concentrations did not affect cellular survival, but demonstrated a strong bactericidal effect against the tested oral pathogens. Overall, these results suggest the strong potential of Zn-based ternary DESs for application in dental medicine, and future research will be directed to understanding the mechanisms by which antibacterial mechanisms are achieved, as well as the evaluation of antibiofilm potential.

5. Conclusions

The present study provides the first evidence of the antibacterial activity and cytotoxicity of novel ternary deep eutectic solvents (DESs) composed of choline chloride, urea, and zinc salts (ChCl:U:Zn(CH3COO)2, ChCl:U:ZnSO4, ChCl:U:ZnCl2). We demonstrate that these components, at specific molar ratios, form stable systems with promising biological potential. The Zn-based ternary DESs displayed strong antibacterial effects against clinically relevant oral isolates—Streptococcus mutans, Streptococcus mitis, Streptococcus sanguinis, and Streptococcus gordonii—with MIC values comparable to conventional antibiotics, while maintaining a low cytotoxic profile in MRC-5 fibroblasts at MICs. However, higher concentrations display cytotoxic impact, which should be taken into account, with the consideration that the safety window of Zn-based DES is up to 100 µg/mL. Overall, the combination of these ternary DESs’ strong antibacterial activity and low cytotoxicity highlights their potential as innovative candidates for application in dental medicine or other biomedical fields.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: J.F.T., N.Z., J.M. and B.J.; Investigation: J.F.T., A.V.Š., N.Z., S.B., M.N. and F.V.; Formal analysis: J.F.T., A.V.Š., N.Z., J.M., S.B., M.N., F.V., S.V. and B.J.; Data curation: J.F.T., A.V.Š., N.Z., S.B., M.N., F.V. and S.V.; Methodology: J.F.T., A.V.Š., N.Z., S.B., M.N., F.V. and S.V.; Supervision and Validation: J.F.T., J.M., B.J. and S.V.; Writing—original draft: J.F.T., N.Z., S.V., B.J. and J.M.; Writing—review and editing: J.F.T., N.Z., F.V., S.V., B.J. and J.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors acknowledge the support provided by the Ministry of Science, Technological Development and Innovation of the Republic of Serbia (Grant no. 451-03-136/2025-03/200017).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by Ethical Committee of the School of Dental Medicine, University of Belgrade, Republic of Serbia (Ethical No 36/7).

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Usman, M.; Cheng, S.; Boonyubol, S.; Cross, J.S. Evaluating Green Solvents for Bio-Oil Extraction: Advancements, Challenges, and Future Perspectives. Energies 2023, 16, 5852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munir, N.; Awang, R.A.; Muhammad, N.; Ismail, N.H.; Khan, A.S.; Inayat, N. Potential Applications of Ionic Liquids in Dentistry: A Narrative Review. ChemBioEng Rev. 2023, 10, 1073–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Dong, X.; Yu, Q.; Baker, S.N.; Li, H.; Larm, N.E.; Baker, G.A.; Chen, L.; Tan, J.; Chen, M. Incorporation of Antibacterial Agent Derived Deep Eutectic Solvent into an Active Dental Composite. Dent. Mater. 2017, 33, 1445–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Achkar, T.; Greige-Gerges, H.; Fourmentin, S. Basics and Properties of Deep Eutectic Solvents: A Review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2021, 19, 3397–3408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, B.B.; Spittle, S.; Chen, B.; Poe, D.; Zhang, Y.; Klein, J.M.; Horton, A.; Adhikari, L.; Zelovich, T.; Doherty, B.W.; et al. Deep Eutectic Solvents: A Review of Fundamentals and Applications. Chem. Rev. 2021, 121, 1232–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez-Juan, E.; López, S.; Abia, R.; Muriana, F.J.G.; Fernández-Bolaños, J.; García-Borrego, A. Antimicrobial Activity on Phytopathogenic Bacteria and Yeast, Cytotoxicity and Solubilizing Capacity of Deep Eutectic Solvents. J. Mol. Liq. 2021, 337, 116343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayyan, M.; Hashim, M.A.; Al-Saadi, M.A.; Hayyan, A.; AlNashef, I.M.; Mirghani, M.E.S. Assessment of Cytotoxicity and Toxicity for Phosphonium-Based Deep Eutectic Solvents. Chemosphere 2013, 93, 455–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, I.J.; Oliveira, F.; Jesus, A.R.; Paiva, A.; Duarte, A.R.C. Current Methodologies for the Assessment of Deep Eutectic Systems Toxicology: Challenges and Perspectives. J. Mol. Liq. 2022, 362, 119675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aroso, I.M.; Silva, J.C.; Mano, F.; Ferreira, A.S.D.; Dionísio, M.; Sá-Nogueira, I.; Barreiros, S.; Reis, R.L.; Paiva, A.; Duarte, A.R.C. Dissolution Enhancement of Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients by Therapeutic Deep Eutectic Systems. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2016, 98, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakrewsky, M.; Banerjee, A.; Apte, S.; Kern, T.L.; Jones, M.R.; Sesto, R.E.D.; Koppisch, A.T.; Fox, D.T.; Mitragotri, S. Choline and Geranate Deep Eutectic Solvent as a Broad-Spectrum Antiseptic Agent for Preventive and Therapeutic Applications. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2016, 5, 1282–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakajima, M.; Tanner, E.E.; Nakajima, N.; Ibsen, K.N.; Mitragotri, S. Topical Treatment of Periodontitis Using an Iongel. Biomaterials 2021, 276, 121069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wikene, K.O.; Rukke, H.V.; Bruzell, E.; Tønnesen, H.H. Physicochemical Characterisation and Antimicrobial Phototoxicity of an Anionic Porphyrin in Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2016, 105, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janić, M.; Zdolšek, N.; Marinković, J.; Lazarević-Pašti, T.; Momić, T.; Brković, S.; Valenta Šobot, A.; Filipović Tričković, J. Sustainable Green Extraction of Selected Polyphenols from Salvia Officinalis L. with Choline Chloride-Based NADES: Phytochemical Screening and Bioactivity. J. Mol. Liq. 2025, 434, 127995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macário, I.P.E.; Oliveira, H.; Menezes, A.C.; Ventura, S.P.M.; Pereira, J.L.; Gonçalves, A.M.M.; Coutinho, J.A.P.; Gonçalves, F.J.M. Cytotoxicity Profiling of Deep Eutectic Solvents to Human Skin Cells. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 3932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurić, T.; Ždero Pavlović, R.; Uka, D.; Beara, I.; Majkić, T.; Savić, S.; Žekić, M.; Popović, B.M. Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents-Mediated Extraction of Rosmarinic Acid from Lamiaceae Plants: Enhanced Extractability and Anti-Inflammatory Potential. Ind. Crops Prod. 2024, 214, 118559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurić, T.; Mićić, N.; Potkonjak, A.; Milanov, D.; Dodić, J.; Trivunović, Z.; Popović, B.M. The Evaluation of Phenolic Content, in Vitro Antioxidant and Antibacterial Activity of Mentha Piperita Extracts Obtained by Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents. Food Chem. 2021, 362, 130226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.; Zhao, X.; Zheng, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, L. Advances and Challenges in Drug Design against Dental Caries: Application of in Silico Approaches. J. Pharm. Anal. 2025, 15, 101161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Nicolás, C.; Pecci-Lloret, M.P.; Guerrero-Gironés, J. Use and Efficacy of Mouthwashes in Elderly Patients: A Systematic Review of Randomized Clinical Trials. Ann. Anat. 2023, 246, 152026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poppolo Deus, F.; Ouanounou, A. Chlorhexidine in Dentistry: Pharmacology, Uses, and Adverse Effects. Int. Dent. J. 2022, 72, 269–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayakumar, A.; Ritty Mohan, J.P. Green Synthesis of ZnO Nanoparticles in Zinc Chloride: Choline Chloride Deep Eutectic Solvent-Characterization Antibacterial and Antioxidant Agents. J. Indian Chem. Soc. 2024, 101, 101375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uwitonze, M.A.; Nkemcho, O.; Julienne, M.; Azeddine, A.; Razzaque, M.S. Optimal Oral Health. Nutrients 2020, 12, 949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lynch, R.J.M. Zinc in the Mouth, Its Interactions with Dental Enamel and Possible Effects on Caries; A Review of the Literature. Int. Dent. J. 2011, 61, 46–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almoudi, M.M.; Hussein, A.S.; Abu Hassan, M.I.; Mohamad Zain, N. A Systematic Review on Antibacterial Activity of Zinc against Streptococcus Mutans. Saudi Dent. J. 2018, 30, 283–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendes, C.R.; Dilarri, G.; Forsan, C.F.; de Sapata, V.M.R.; Lopes, P.R.M.; de Moraes, P.B.; Montagnolli, R.N.; Ferreira, H.; Bidoia, E.D. Antibacterial Action and Target Mechanisms of Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles against Bacterial Pathogens. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 2658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelraheem, W.M.; Kamel, H.S.; Gamil, A.N. Evaluation of Anti-Biofilm and Anti-Virulence Effect of Zinc Sulfate on Staphylococcus Aureus Isolates. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 25747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deumić, S.; El Sayed, A.; Hsino, M.; Kulesa, A.; Crnčević, N.; Vladavić, N.; Borić, A.; Avdić, M. Investigating the Effect of Zinc Salts on Escherichia Coli and Enterococcus Faecalis Biofilm Formation. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 8383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, X.; Li, J.; Khan, M.Z.H.; Ma, F.; Liu, X. A Novel Zinc Complex with Antibacterial and Antioxidant Activity. BMC Chem. 2021, 15, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohiagu, F.O.; Chidoka, P.; Ahaneku, C.C. Human Exposure to Heavy Metals: Toxicity Mechanisms and Health Implications. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2022, 6, 78–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Wang, P.; Guo, J.; Ma, T.; Hu, Y.; Huang, L.; Xing, B.; He, Y.; Xi, J. Zinc Overload Induces Damage to H9c2 Cardiomyocyte Through Mitochondrial Dysfunction and ROS-Mediated Mitophagy. Cardiovasc. Toxicol. 2023, 23, 388–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlica, S.; Gaunitz, F.; Gebhardt, R. Comparative in Vitro Toxicity of Seven Zinc-Salts towards Neuronal PC12 Cells. Toxicol. Vitr. 2009, 23, 653–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janković, B.; Manić, N.; Perović, I.; Vujković, M.; Zdolšek, N. Thermal Decomposition Kinetics of Deep Eutectic Solvent (DES) Based on Choline Chloride and Magnesium Chloride Hexahydrate: New Details on the Reaction Mechanism and Enthalpy–Entropy Compensation (EEC). J. Mol. Liq. 2023, 374, 121274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillenkamp, F.; Beavis, R.C.; Brian, T. Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization Mass Spectrometry of Biopolymers. Anal. Chem. 1991, 63, 1193A–1203A. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singhal, N.; Kumar, M.; Kanaujia, P.K.; Virdi, J.S. MALDI-TOF Mass Spectrometry: An Emerging Technology for Microbial Identification and Diagnosis. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 6, 791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasch, P.; Beyer, W.; Bosch, A.; Borriss, R.; Drevinek, M.; Dupke, S.; Ehling-schulz, M.; Gao, X.; Grunow, R.; Jacob, D.; et al. A MALDI-ToF Mass Spectrometry Database for Identification and Classification of Highly Pathogenic Bacteria. Sci. Data 2025, 12, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinković, J.; Marković, T.; Brkić, S.; Radunović, M.; Soldatović, I.; Ćirić, A.; Marković, D. Microbiological Analysis of Primary Infected Root Canals with Symptomatic and Asymptomatic Apical Periodontitis of Young Permanent Teeth. Balk. J. Dent. Med. 2020, 24, 170–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diouchi, J.; Marinković, J.; Nemoda, M.; El Rhaffari, L.; Toure, B.; Ghoul, S. In Vitro Methods for Assessing the Antibacterial and Antibiofilm Properties of Essential Oils as Potential Root Canal Irrigants—A Simplified Description of the Technical Steps. Methods Protoc. 2024, 7, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roehm, N.W.; Rodgers, G.H.; Hatfield, S.M.; Glasebrook, A.L. An Improved Colorimetric Assay for Cell Proliferation and Viability Utilizing the Tetrazolium Salt XTT. J. Immunol. Methods 1991, 142, 257–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strober, W. Trypan Blue Exclusion Test of Cell Viability. Curr. Protoc. Immunol. 2015, 111, A3.B.1–A3.B.3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matijević, M.; Žakula, J.; Korićanac, L.; Radoičić, M.; Liang, X.; Mi, L. Controlled Killing of Human Cervical Cancer Cells by Combined Action of Blue Light and C-Doped TiO2 Nanoparticles. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2021, 20, 1087–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coşkun Demirkalp, A.N. Use and Comparison of MTT, XTT and ICELLigence Methods in the Evaluation of Drug Toxicity. Med. Palliat. Care 2025, 6, 66–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatta, N.M.; Halim, S.A. Potential Green Liquid From Ternary Deep Eutectic Solvent Composed of Gallic Acid, Urea, and Zinc Chloride: Characterization of Their Physicochemical and Thermal Properties. Malaysian J. Anal. Sci. 2024, 28, 174–187. Available online: https://mjas.analis.com.my/mjas/v28_n1/pdf/Mohd%20Hatta_28_1_15.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Gregorio, V.; Baur, C.; Jankowski, P.; Chang, J.H. Deep Eutectic Solvents as Electrolytes for Zn Batteries: Between Blocked Crystallization, Electrochemical Performance and Corrosion Issues. ChemSusChem 2025, 18, 2–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agostinho, B.; Irska, I.; Kwiatkowska, M.; Szymczyk, A.; Silvestre, A.J.D.; Sousa, A.F. Optimized Closed-Loop Recycling of Bio-Based Poly(Trimethylene 2,5-Furandicarboxylate) Using Eutectic Solvents. Sustain. Mater. Technol. 2025, 45, e01506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.; Yuan, Y.; Yang, Q.; Chen, L.; Deng, J.; Chen, W.; Lian, H.; Mota-Morales, J.D.; Liimatainen, H. Choline Chloride-Zinc Chloride Deep Eutectic Solvent Mediated Preparation of Partial O-Acetylation of Chitin Nanocrystal in One Step Reaction. Carbohydr. Polym. 2019, 220, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, D.; Li, J.; Xu, C.; Wang, S.; Xiang, G.; Chen, W.; Zhang, Q.; Hua, Y.; Li, Y. Existence Forms and Electrodeposition Behavior of Various Zinc Compounds in Choline Chloride—Urea Deep-Eutectic Solvent. J. Mol. Liq. 2024, 394, 123592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamaddon, F.; Ahmadi-Ahmad Abadi, E.; Noorbala, M.R. ZnCl2:ChCl:2urea as a New Ternary Deep Eutectic for Clean Production of High Content Zwitterionic Micro- or Nano-Cellulose by Passing to the Binary DES of ZnCl2:2urea. J. Mol. Liq. 2023, 387, 122662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, L.; Sun, H.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Ding, C.; Xu, X.; Li, J. Green Eutectogel with Antibacterial-Sensing Integration for Infected Wound Treatment. Sci. China Mater. 2024, 67, 3861–3871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, Y.; Li, H.; Fan, X.; Yan, H.; Cai, M.; Xu, X.; Zhu, M. Insights into the Tribological Behavior of Choline Chloride—Urea and Choline Chloride—Thiourea Deep Eutectic Solvents. Friction 2023, 11, 76–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, J.; Podder, J. Crystallization Of Zinc Sulphate Single Crystals And Its Structural, Thermal And Optical Characterization. J. Bangladesh Acad. Sci. 1970, 35, 203–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salazar-García, S.; García-Rodrigo, J.F.; Delgado Buenrostro, N.L.; Martínez Castañón, G.A.; España Sánchez, B.L.; Chirino, Y.I.; Gonzalez, C. Zinc Chloride through N-Cadherin Upregulation Prevents the Damage Induced by Silver Nanoparticles in Rat Cerebellum. J. Nanoparticle Res. 2022, 24, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anžlovar, A.; Crnjak Orel, Z.; Žigon, M. Poly(Methyl Methacrylate) Composites Prepared by in Situ Polymerization Using Organophillic Nano-to-Submicrometer Zinc Oxide Particles. Eur. Polym. J. 2010, 46, 1216–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Pietro, M.E.; Tortora, M.; Bottari, C.; Colombo Dugoni, G.; Pivato, R.V.; Rossi, B.; Paolantoni, M.; Mele, A. In Competition for Water: Hydrated Choline Chloride:Urea vs Choline Acetate:Urea Deep Eutectic Solvents. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 12262–12273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Percevault, L.; Delhaye, T.; Chaumont, A.; Schurhammer, R.; Paquin, L.; Rondeau, D. Cold-Spray Ionization Mass Spectrometry of the Choline Chloride-Urea Deep Eutectic Solvent (Reline). J. Mass Spectrom. 2021, 56, e4725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz, P.I.; Xie, Z.; Sobue, T.; Thompson, A.; Biyikoglu, B.; Ricker, A.; Ikonomou, L.; Dongari-Bagtzoglou, A. Synergistic Interaction between Candida Albicans and Commensal Oral Streptococci in a Novel in Vitro Mucosal Model. Infect. Immun. 2012, 80, 620–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolenbrander, P.E.; Palmer, R.J.; Periasamy, S.; Jakubovics, N.S. Oral Multispecies Biofilm Development and the Key Role of Cell-Cell Distance. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2010, 8, 471–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevgi, F.; Bagkesici, U.; Kursunlu, A.N.; Guler, E. Fe (III), Co(II), Ni(II), Cu(II) and Zn(II) Complexes of Schiff Bases Based-on Glycine and Phenylalanine: Synthesis, Magnetic/Thermal Properties and Antimicrobial Activity. J. Mol. Struct. 2018, 1154, 256–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Kohno, T.; Tsuboi, R.; Kitagawa, H.; Imazato, S. Acidity-Induced Release of Zinc Ion from BiounionTM Filler and Its Inhibitory Effects against Streptococcus Mutans. Dent. Mater. J. 2020, 39, 547–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Da Silva, B.L.; Abuçafy, M.P.; Manaia, E.B.; Junior, J.A.O.; Chiari-Andréo, B.G.; Pietro, R.C.L.R.; Chiavacci, L.A. Relationship between Structure and Antimicrobial Activity of Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles: An Overview. Int. J. Nanomed. 2019, 14, 9395–9410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavassoli Hojati, S.; Alaghemand, H.; Hamze, F.; Ahmadian Babaki, F.; Rajab-Nia, R.; Rezvani, M.B.; Kaviani, M.; Atai, M. Antibacterial, Physical and Mechanical Properties of Flowable Resin Composites Containing Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles. Dent. Mater. 2013, 29, 495–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Q.; Chen, J.X.; Tang, Y.L.; Wang, J.; Yang, Z. Assessing the Toxicity and Biodegradability of Deep Eutectic Solvents. Chemosphere 2015, 132, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almoudi, M.M.; Hussein, A.S.; Mohd Sarmin, N.I.; Abu Hassan, M.I. Antibacterial Effectiveness of Different Zinc Salts on Streptococcus Mutans and Streptococcus Sobrinus: An in-Vitro Study. Saudi Dent. J. 2023, 35, 883–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khorsandi, M.; Nemati-Kande, E.; Hosseini, F.; Martinez, F.; Shekaari, H.; Mokhtarpour, M. Effect of Choline Chloride Based Deep Eutectic Solvents on the Aqueous Solubility of 4-Hydroxycoumarin Drug: Measurement and Correlation. J. Mol. Liq. 2022, 368, 120650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radošević, K.; Čanak, I.; Panić, M.; Markov, K.; Bubalo, M.C.; Frece, J.; Srček, V.G.; Redovniković, I.R. Antimicrobial, Cytotoxic and Antioxidative Evaluation of Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2018, 25, 14188–14196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florindo, C.; Oliveira, F.S.; Rebelo, L.P.N.; Fernandes, A.M.; Marrucho, I.M. Insights into the Synthesis and Properties of Deep Eutectic Solvents Based on Cholinium Chloride and Carboxylic Acids. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2014, 2, 2416–2425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popović, B.M.; Gligorijević, N.; Aranđelović, S.; Macedo, A.C.; Jurić, T.; Uka, D.; Mocko-Blažek, K.; Serra, A.T. Cytotoxicity Profiling of Choline Chloride-Based Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents. RSC Adv. 2023, 13, 3520–3527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiriyasatiankun, P.; Sakoolnamarka, R.; Thanyasrisung, P. The Impact of an Alkasite Restorative Material on the PH of Streptococcus mutans Biofilm and Dentin Remineralization: An in Vitro Study. BMC Oral Health 2022, 22, 334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Swaaij, B.W.M.; Slot, D.E.; Van der Weijden, G.A.; Timmerman, M.F.; Ruben, J. Fluoride, PH Value, and Titratable Acidity of Commercially Available Mouthwashes. Int. Dent. J. 2023, 74, 260–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lenander-Lumikari, M.; Saliva, V.L. Dental Caries. Adv. Dent. Res. 2000, 14, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canta, M.; Cauda, V. Europe PMC Funders Group The Investigation of the Parameters Affecting the ZnO Nanoparticles Cytotoxicity Behaviour: A Tutorial Review. Biomater. Sci. 2021, 8, 6157–6174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salesa, B.; Sabater, R.; Serrano-Aroca, Á. Promotion of Glycoprotein Synthesis and Antioxidant Gene Expression in Human Keratinocytes. Biology 2021, 10, 1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcinčáková, D.; Schusterová, P.; Mudroňová, D.; Csank, T.; Falis, M.; Fedorová, M.; Marcinčák, S.; Hus, K.K.; Legáth, J. Impact of Zinc Sulfate Exposition on Viability, Proliferation and Cell Cycle Distribution of Epithelial Kidney Cells. Polish J. Environ. Stud. 2019, 28, 3279–3286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khabir, Z.; Holmes, A.M.; Lai, Y.J.; Liang, L.; Deva, A.; Polikarpov, M.A.; Roberts, M.S.; Zvyagin, A.V. Human Epidermal Zinc Concentrations after Topical Application of ZnO Nanoparticles in Sunscreens. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 12372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, A.N.; Weaver, N.A.; Monahan, K.S.; Kim, K. Non-ROS-Mediated Cytotoxicity of ZnO and CuO in ML-1 and CA77 Thyroid Cancer Cell Lines. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 4055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cierech, M.; Wojnarowicz, J.; Kolenda, A.; Krawczyk-Balska, A.; Prochwicz, E.; Woźniak, B.; Łojkowski, W.; Mierzwińska-Nastalska, E. Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles Cytotoxicity and Release from Newly Formed PMMA–ZNO Nanocomposites Designed for Denture Bases. Nanomaterials 2019, 9, 1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinković, J.; Marković, T.; Miličić, B.; Soković, M.; Ćirić, A.; Marković, D. Outstanding Efficacy of Essential Oils Against Oral Pathogens. In Essential Oil Research; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 211–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villalpando-Rodriguez, G.E.; Gibson, S.B. Review Article Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) Regulates Different Types of Cell Death by Acting as a Rheostat. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2021, 2021, 9912436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).