Numerical Simulation of the Combustion Characteristics of a 330 MW Tangentially Fired Boiler with Preheating Combustion Devices Under Various Loads

Abstract

1. Introduction

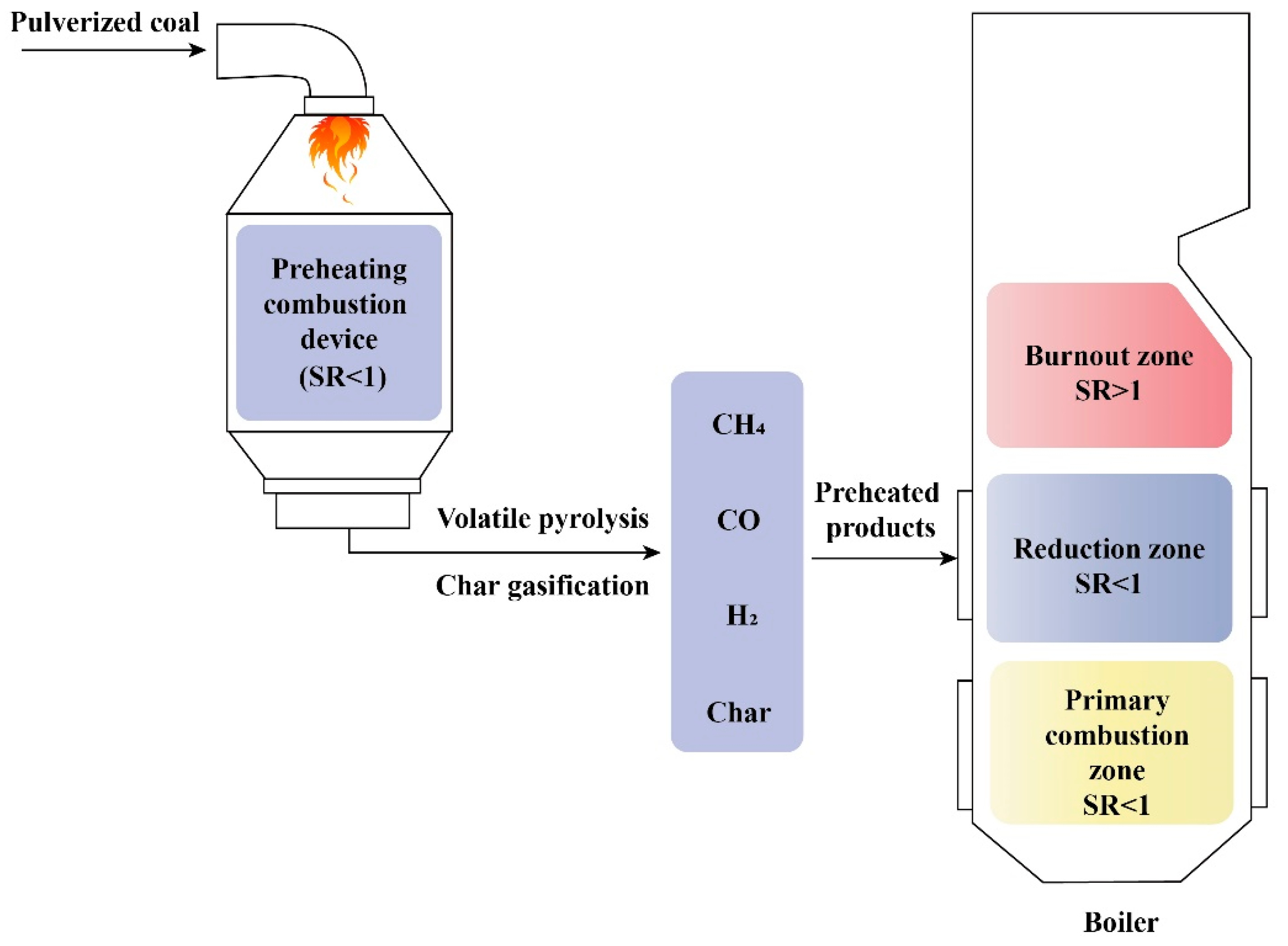

2. Methodology

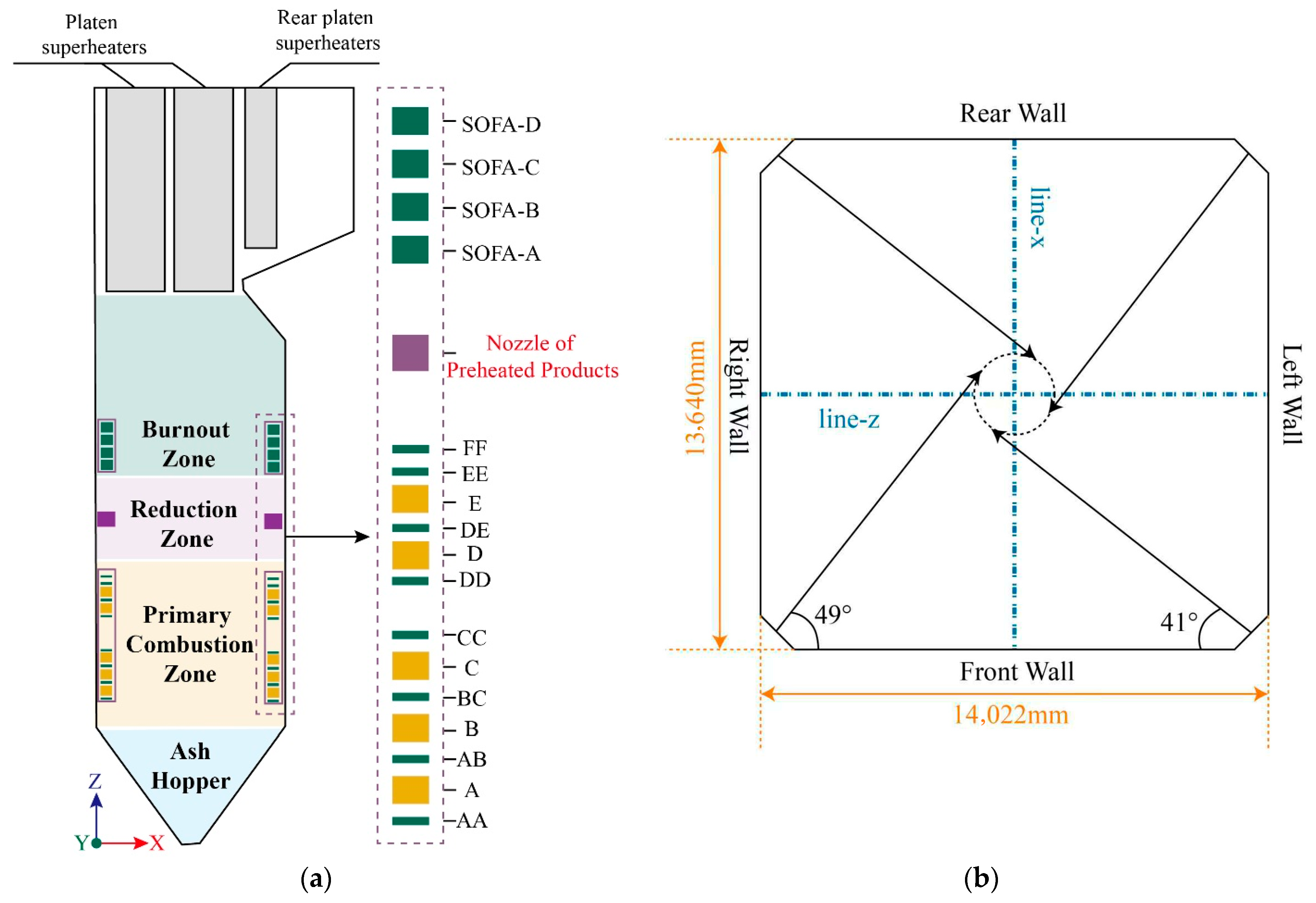

2.1. Boiler Description

2.2. Case Setup and Coal Properties

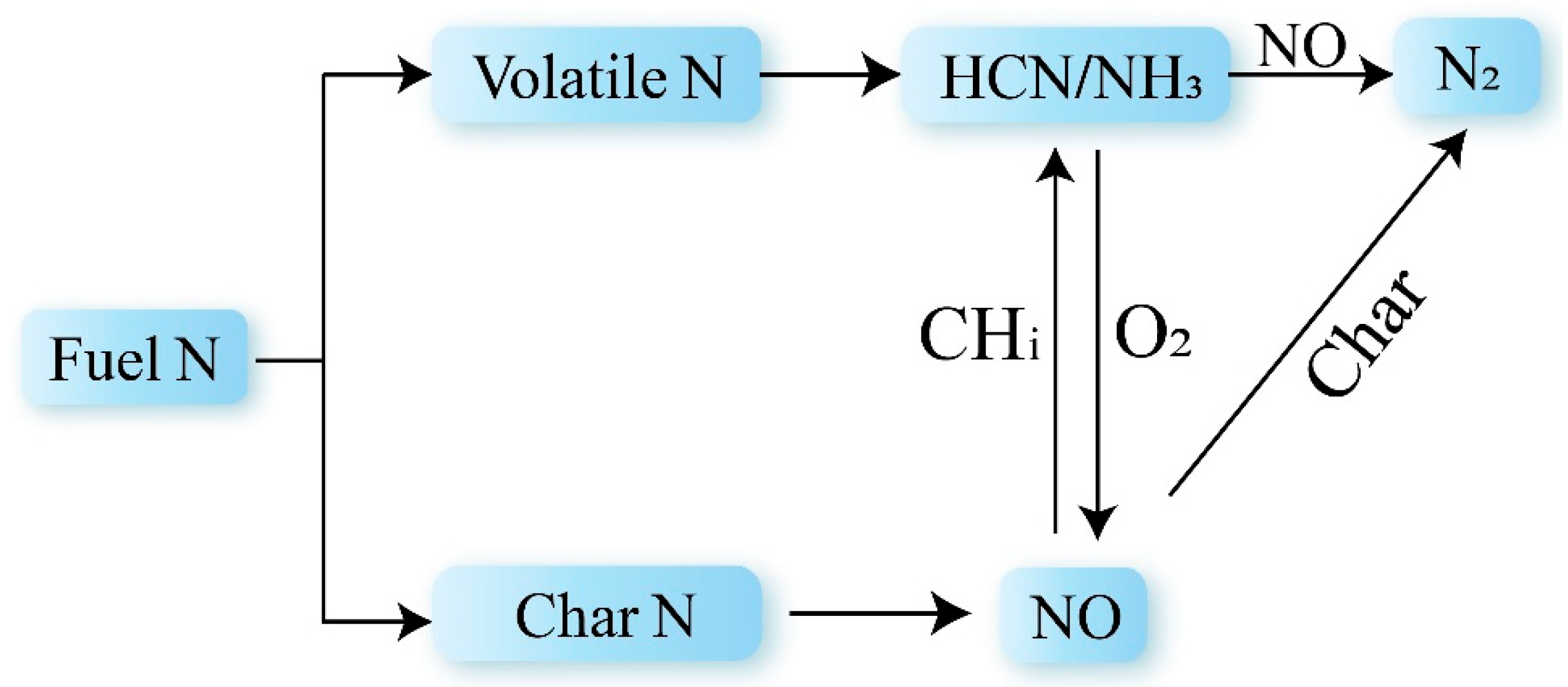

2.3. Numerical Models

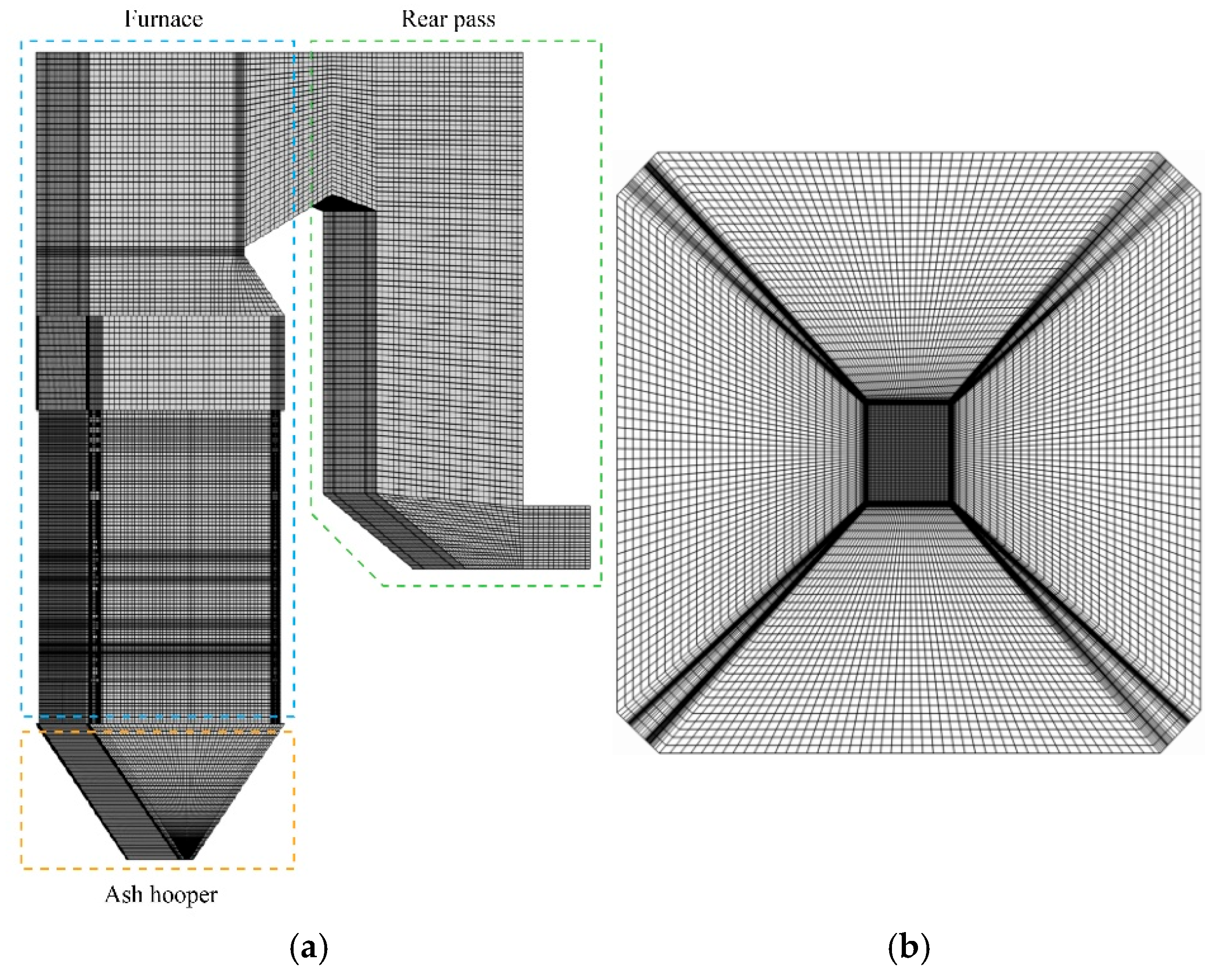

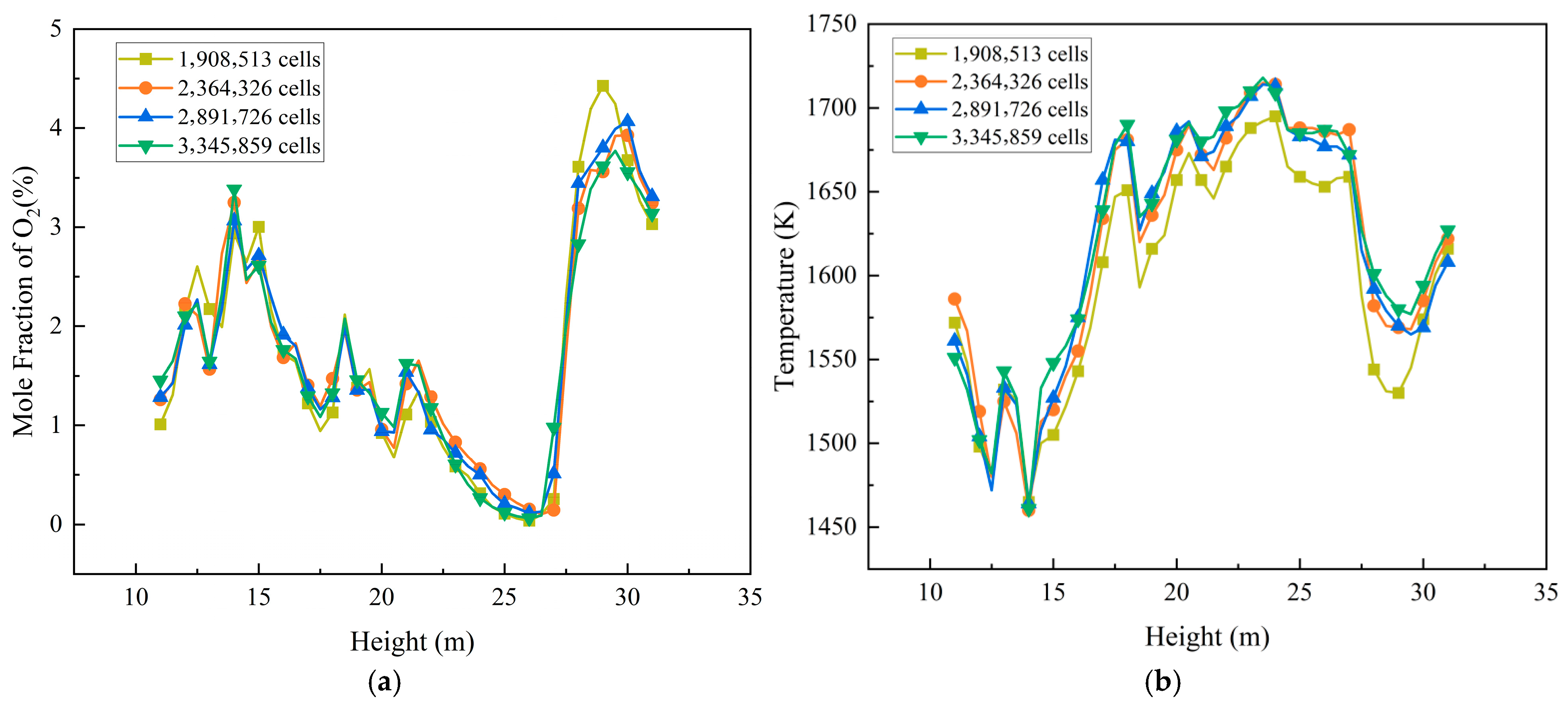

2.4. Mesh Independence and Model Verification

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Effects of Load on Combustion Performance of the Boiler

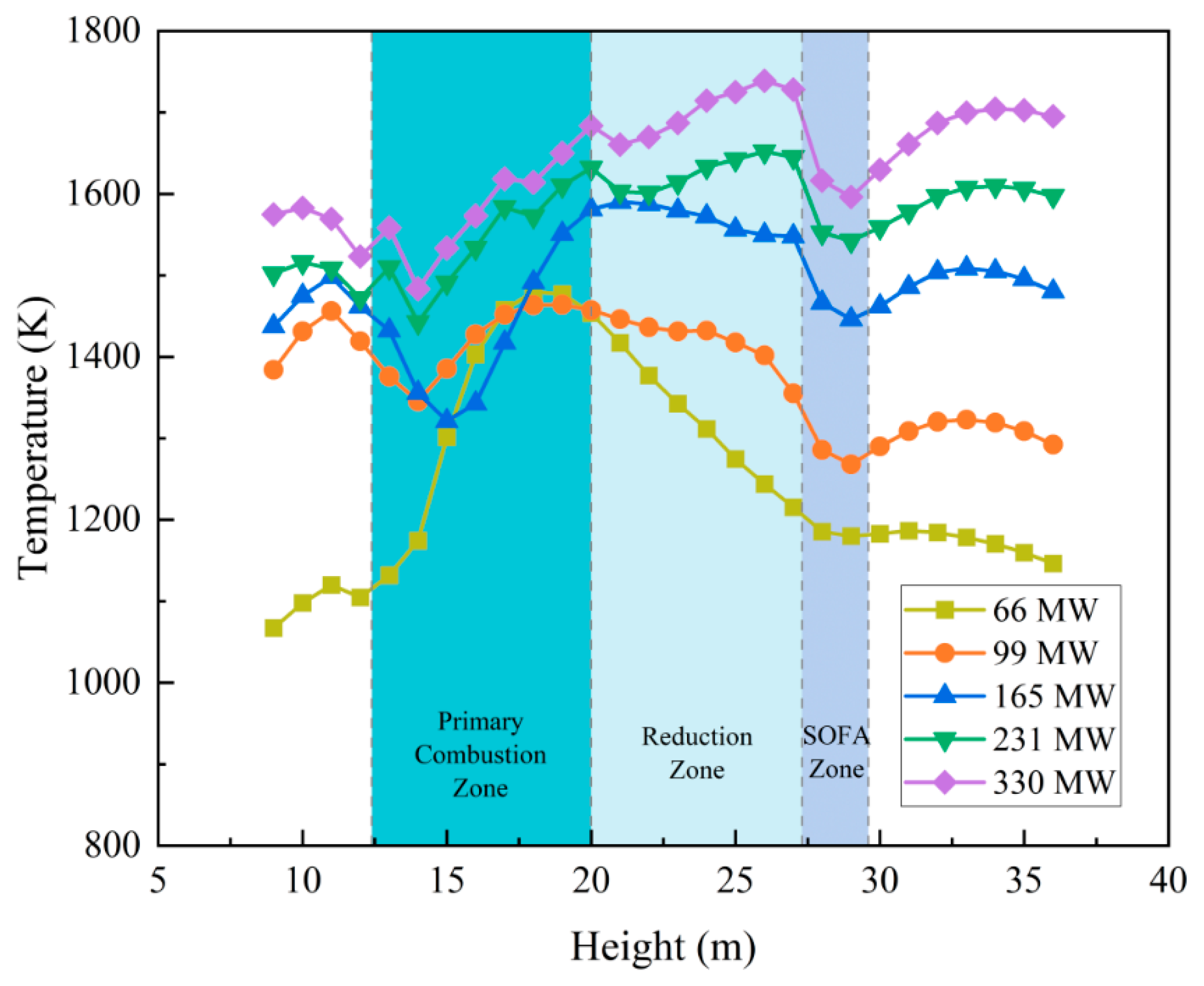

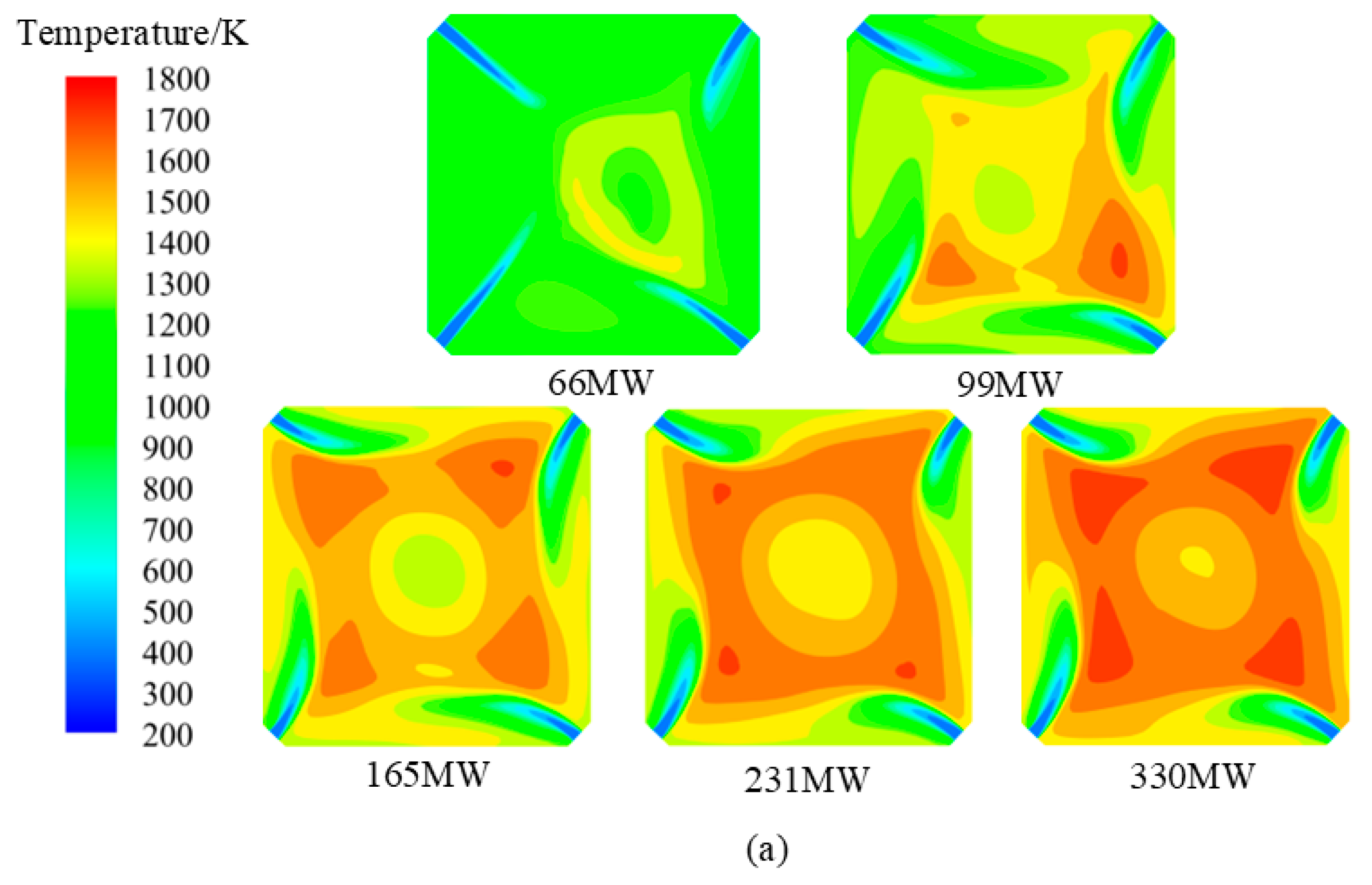

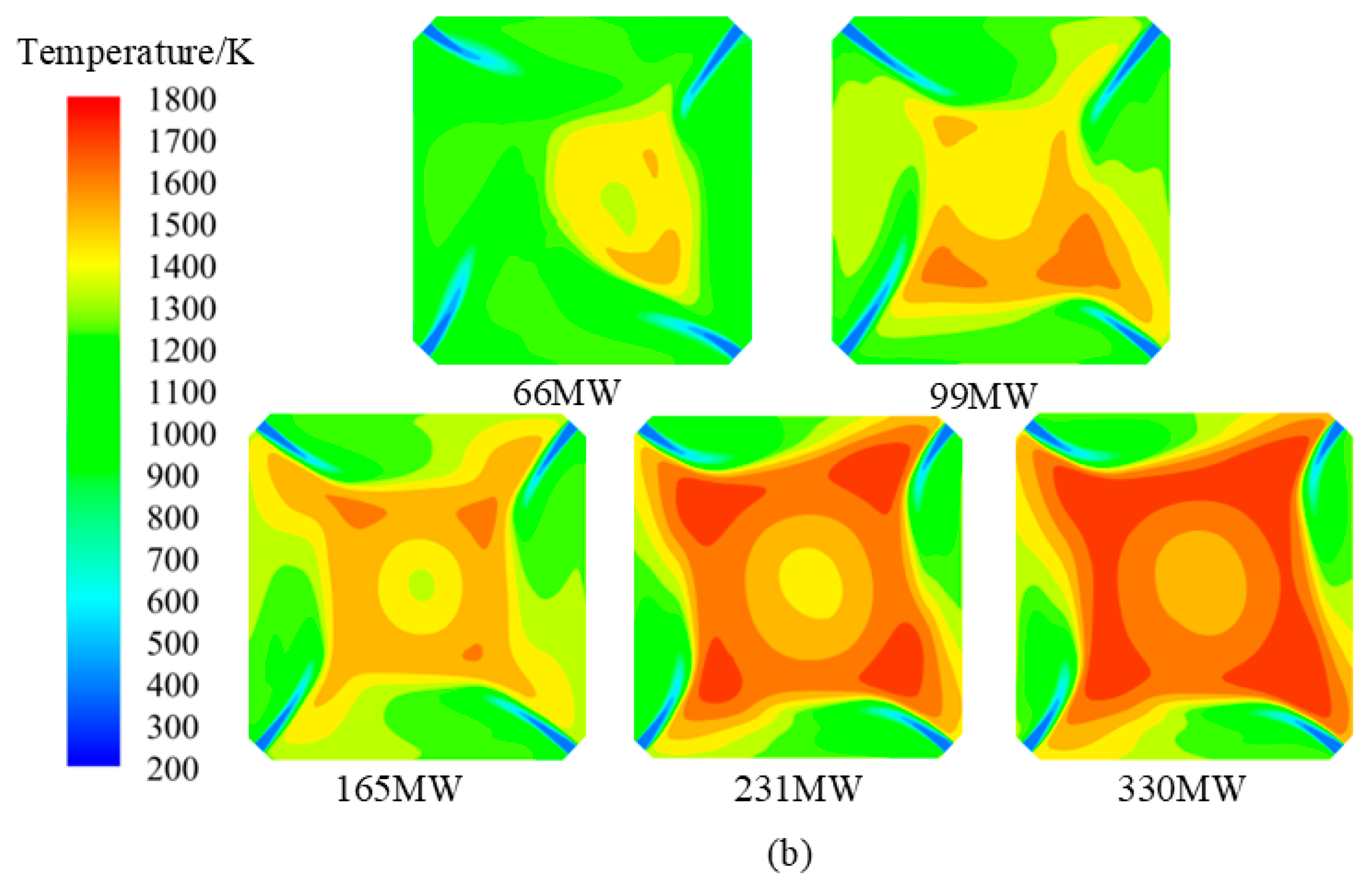

3.1.1. Temperature Distribution

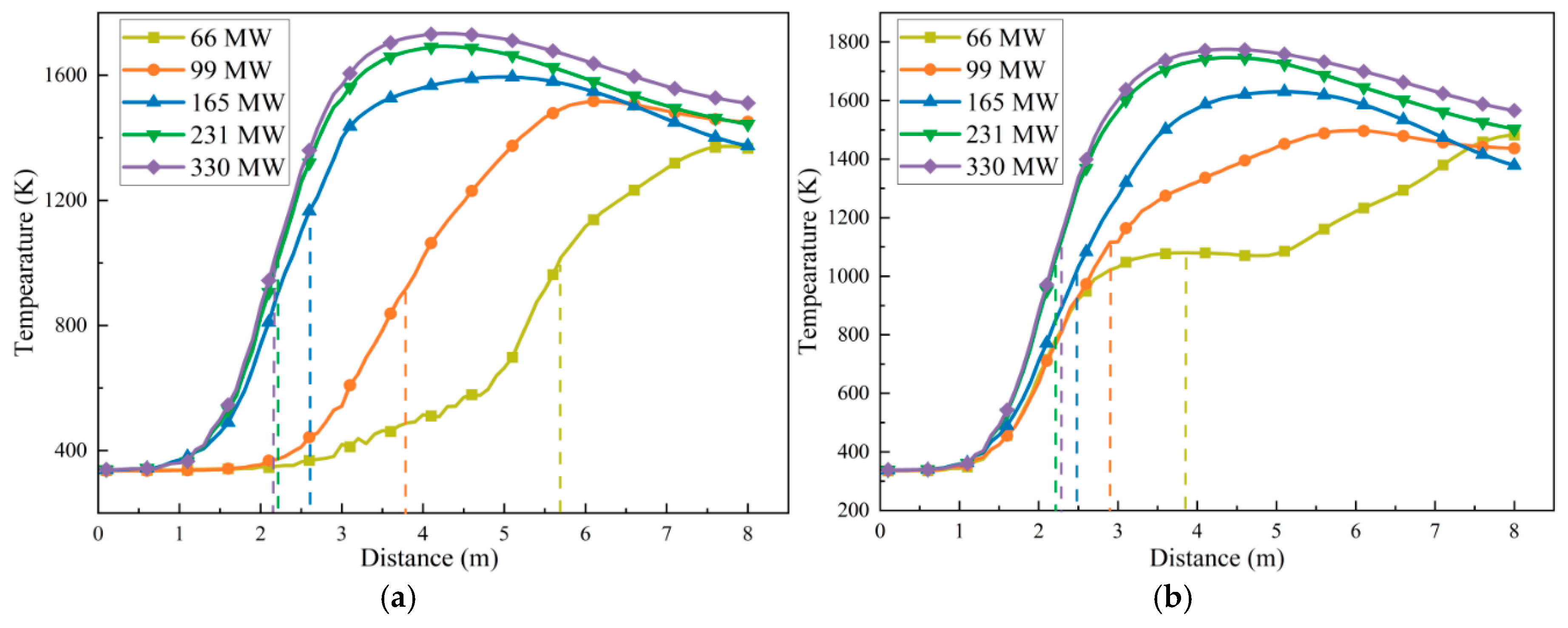

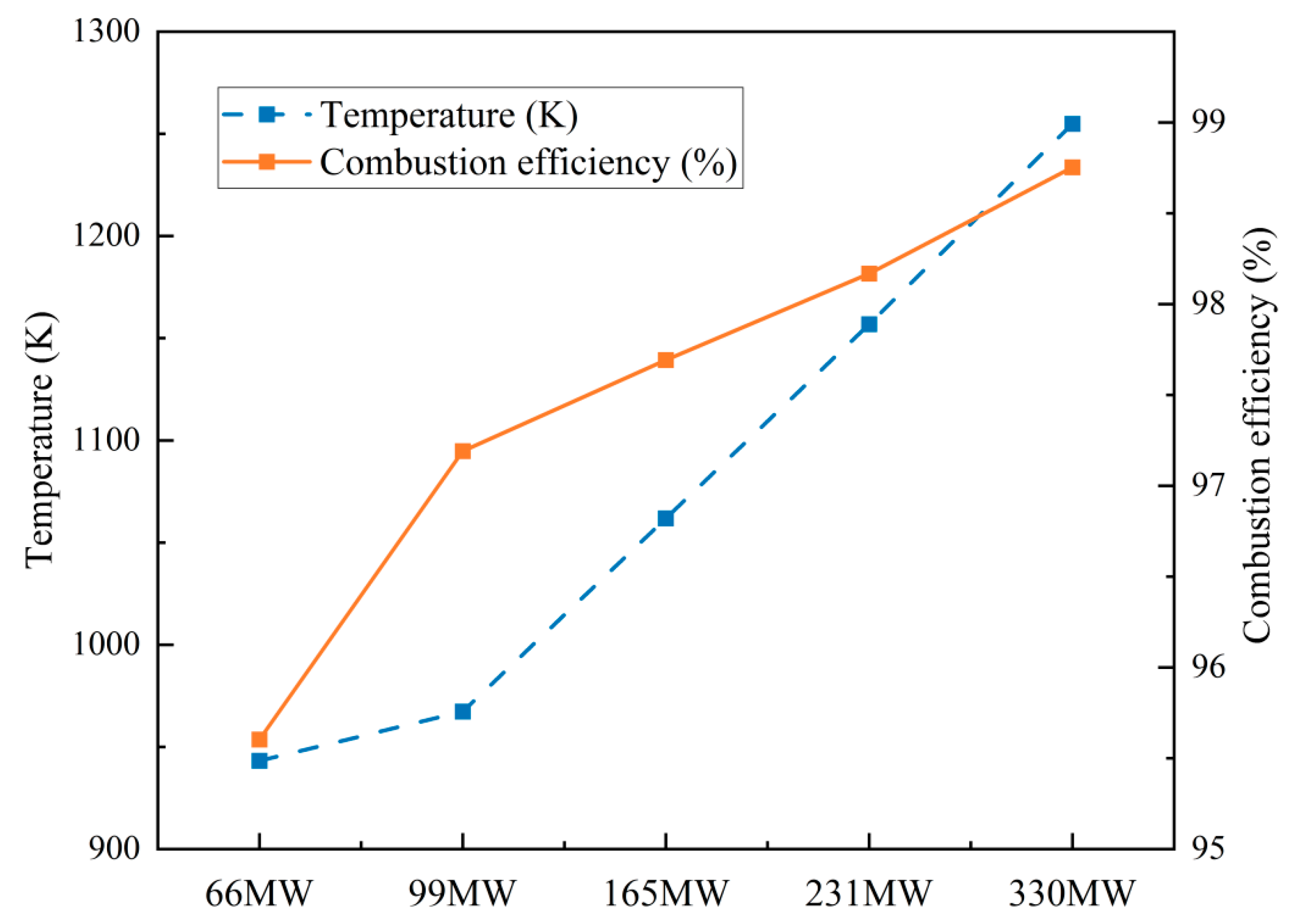

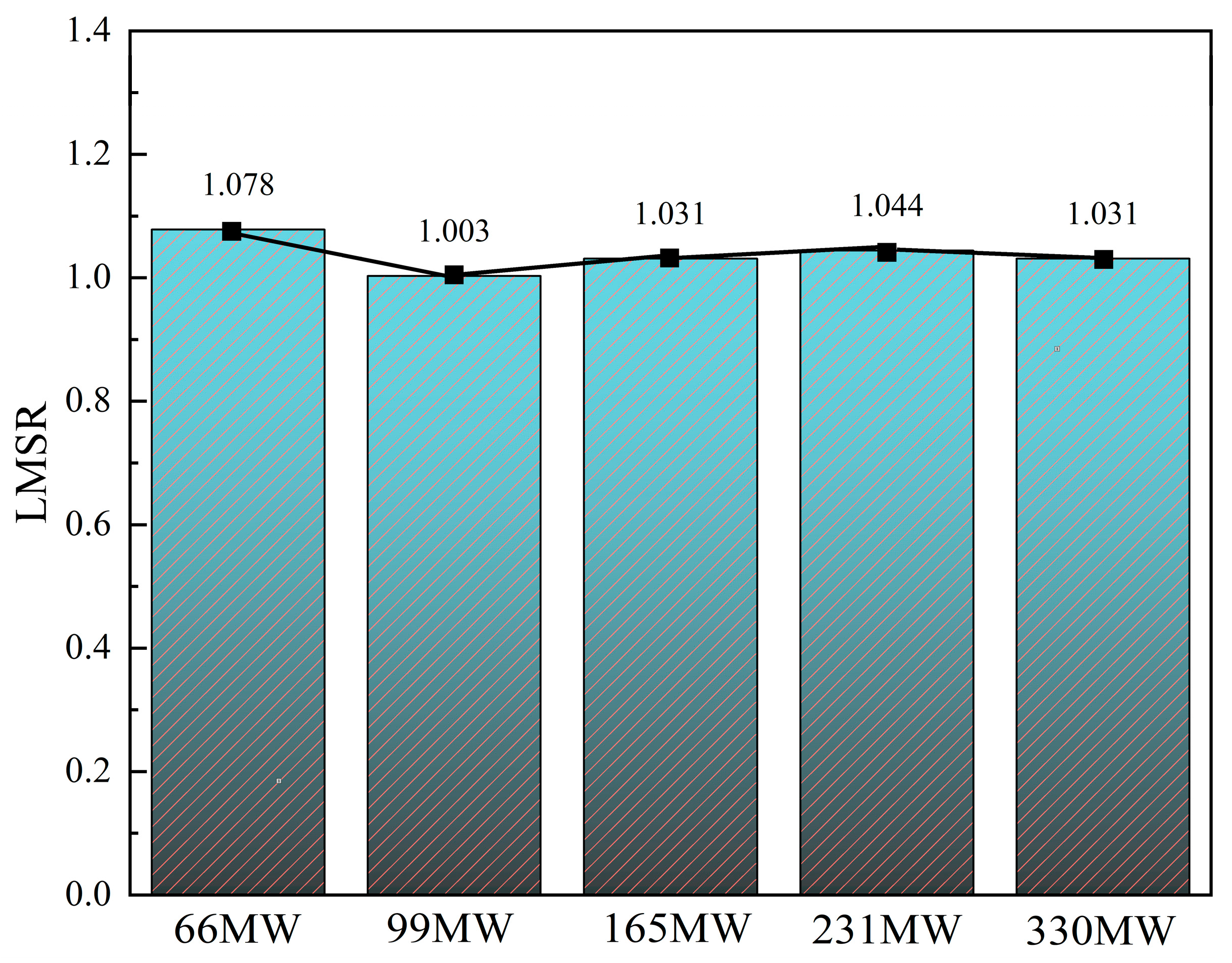

3.1.2. Combustion Stability and Efficiency Under Various Loads

3.2. Effects of Loads on the O2 and NOx Distribution of the Boiler

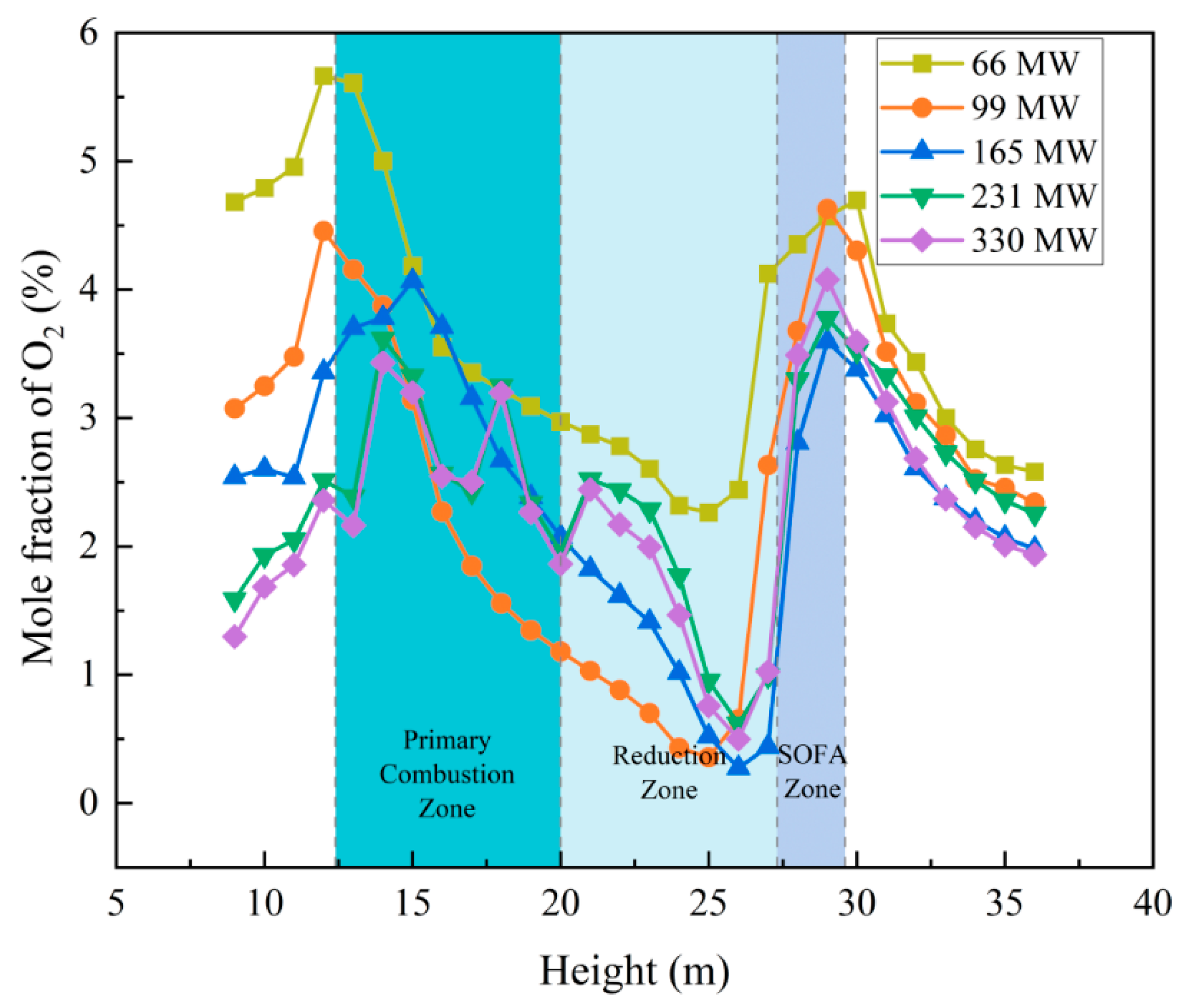

3.2.1. O2 Distribution Under Various Loads

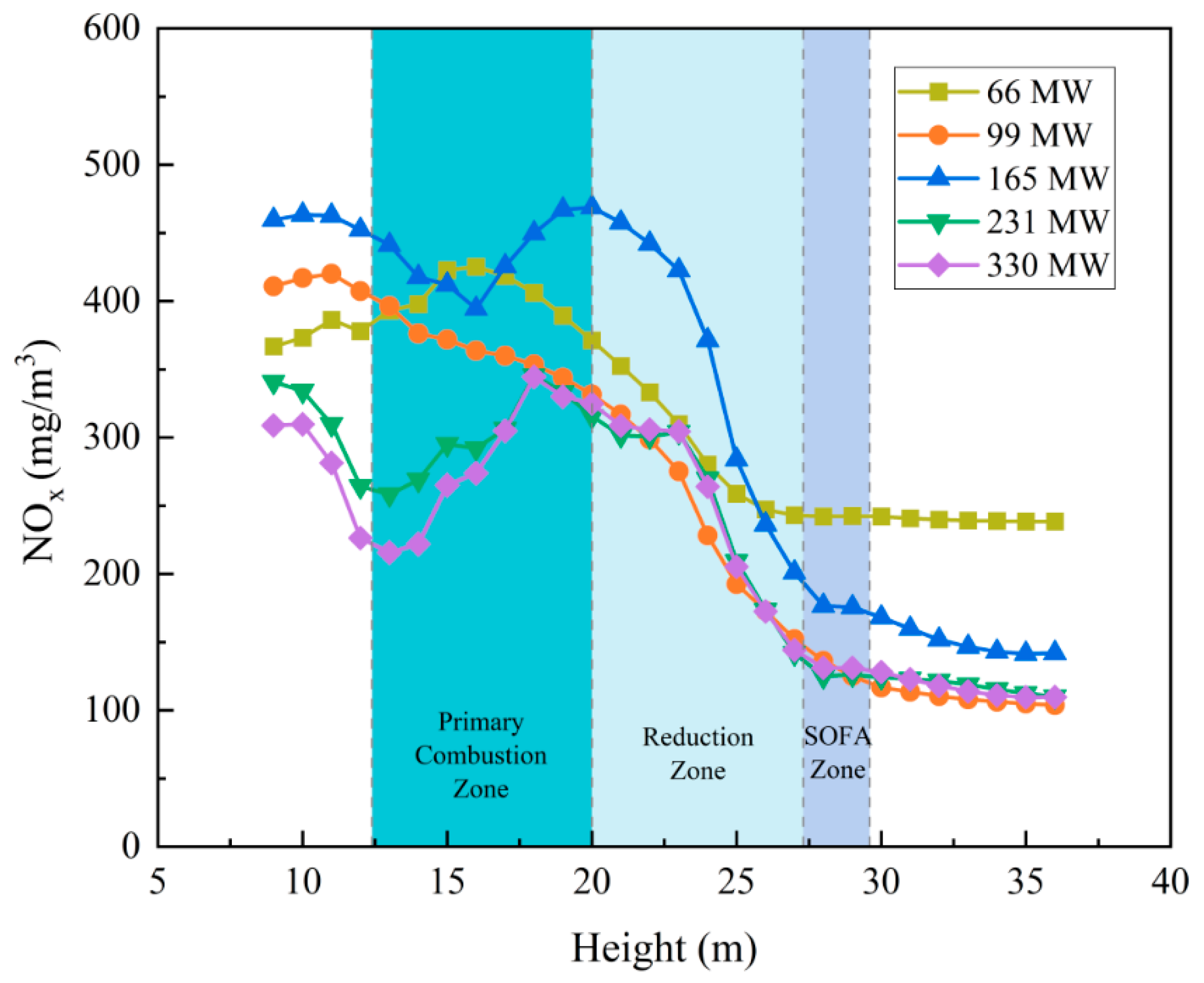

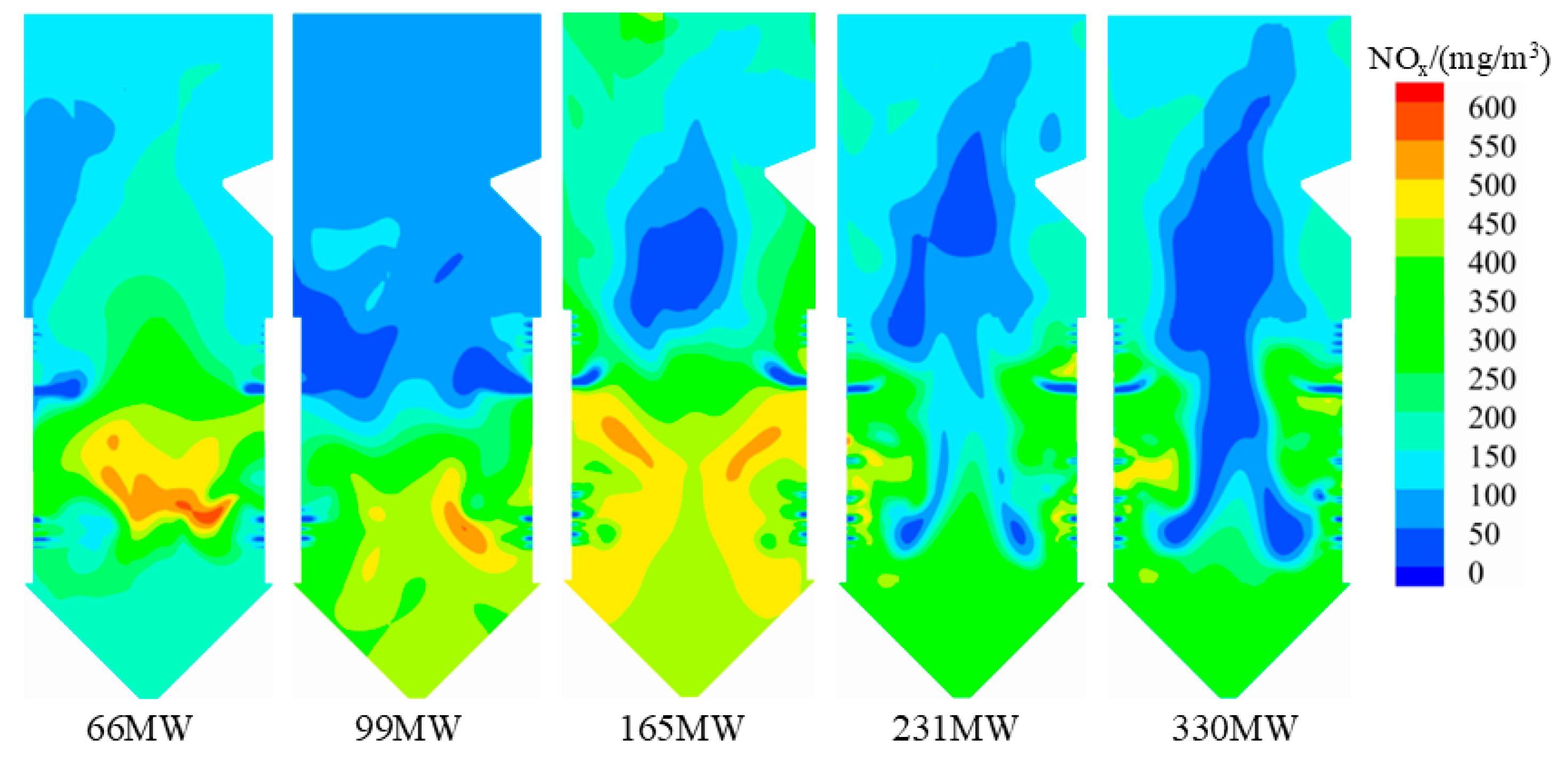

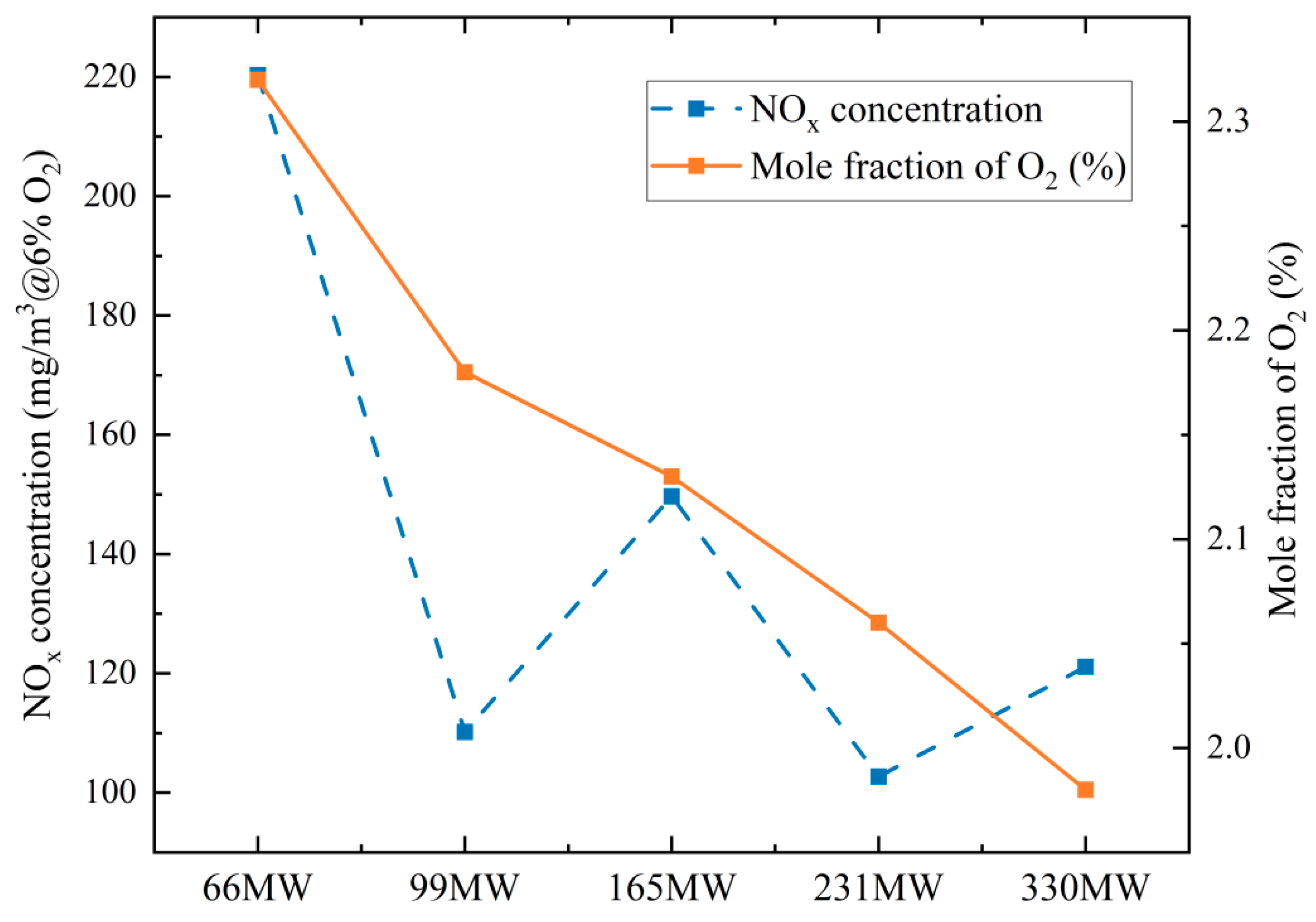

3.2.2. NOx Distribution Under Various Loads

4. Conclusions

- (1)

- The boiler with the PCDs can achieve stable operation with an acceptable combustion efficiency over a load range of 66 MW to 330 MW. As the load declines, the temperature distribution in the furnace becomes uneven, while the ignition distance of pulverized coal increases.

- (2)

- As the load decreases from 330 MW to 66 MW, the boiler’s combustion efficiency gradually declines from 98.7% to 95.6%. The PCDs help achieve complete combustion. Under the 66 MW scenario, boiler combustion stability markedly decreases, accompanied by a significant rise in NOx emissions. Therefore, the PCDs should not be engaged at a boiler load of 66 MW.

- (3)

- With fluctuations in boiler load, the NOx concentration at the furnace outlet varies from 102.7 mg/Nm3 to 220.3 mg/Nm3. The preheated products effectively reduce NOx generated during the combustion process under most loads, thereby lowering NOx emissions at the boiler outlet.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Nomenclature

| A1, A2 | Pre-exponential factors of devolatilization at low temperature and high temperature (s−1) |

| C | Diffusion rate constant of oxygen to particle surface |

| Cf | Combustible percentage of fly ash (%) |

| dp | Diameter of particle (m) |

| D0 | Diffusion rate coefficient (m2/s) |

| E1, E2 | Activation energy of devolatilization at low temperature and high temperature (J/kmol) |

| fw,0 | Initial mass fraction of moisture in coal particle |

| FD | Particle drag coefficient under turbulence |

| Gb | Turbulence kinetic energy generated by buoyancy (kg/(m⋅s3)) |

| Gk | Turbulence kinetic energy generated by mean velocity gradients (kg/(m⋅s3)) |

| k | Turbulence kinetic energy (m2/s2) |

| kf,i | Rate constants for forward reactions of thermal NO formation (i = 1, 2, 3) (m3/(gmol·s)) |

| kr,i | Rate constants for reverse reactions of thermal NO formation (i = 1, 2, 3) (m3/(gmol·s)) |

| ma | Ash content in coal particle (kg) |

| mp | Coal particle mass (kg) |

| mp,0 | Initial mass of particle (kg) |

| mv(t) | Volatile yield over time (kg) |

| p | Static pressure (Pa) |

| pox | Partial pressure of oxidant around char (Pa) |

| R | Universal gas constant (J/(kmol·K)) |

| Rp | Kinetic rate at particle surface (s−1) |

| S | Source term |

| Tp | Temperature of pulverized coal (K) |

| T∞ | Gas-phase temperature (K) |

| u | Velocity vector of gas phase (m/s) |

| Vgy | Volume of flue gas (Nm3/kg) |

| Abbreviations | |

| CCOFA | Close-coupled overfire air |

| LMSR | Local mean stoichiometric ratio |

| PA | Primary air |

| PCD | Preheating combustion device |

| SA | Secondary air |

| SOFA | Separated overfire air |

| SR | Stoichiometric ratio |

| Greek Symbols | |

| α1, α2 | Yield factors |

| ε | Turbulence dissipation rate (m2/s3) |

| ηr | Combustion efficiency (%) |

| μ | Molecular viscosity (N⋅s/m2) |

| μt | Gas-phase turbulent viscosity (N⋅s/m2) |

| ρ | Gas density (kg/m3) |

| υ | Kinematic viscosity (m2/s) |

| σk, σε | Turbulent Prandtl numbers for k and ε |

References

- Wang, H.; Jin, H.; Yang, Z.; Deng, S.; Wu, X.; An, J.; Sheng, R.; Ti, S. CFD modeling of flow, combustion and NOx emission in a wall-fired boiler at different low-load operating conditions. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2023, 236, 121824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Wang, C.; Fan, J.; Liu, M.; Xing, Y.; Yan, J. Enhancing the flexibility and stability of coal-fired power plants by optimizing control schemes of throttling high-pressure extraction steam. Energy 2023, 288, 129756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Wang, Y.; Zou, L.; Bai, Y.; Shen, T.; Wei, Y.; Li, F.; Zhao, Q. Numerical investigation of stable combustion at ultra-low load for a 350 MW wall tangentially fired pulverized-coal boiler: Effect of burner adjustments and methane co-firing. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2024, 246, 122980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, D.; Zhang, S.; He, X.; Zhang, J.; Ding, X. Combustion stability and NOX emission characteristics of a 300 MWe tangentially fired boiler under ultra-low loads with deep-air staging. Energy 2023, 269, 126795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, M.; Zeng, L.; Li, Z. Combustion stability, burnout and NO emissions of the 300-MW down-fired boiler with bituminous coal: Load variation and low-load comparison with anthracite. Fuel 2021, 295, 120641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Qiao, X.; Miao, Z. Low load performance of tangentially-fired boiler with annularly combined multiple airflows. Energy 2021, 224, 120131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Lee, B.-H.; Oh, D.-H.; Jeon, C.-H. Optimization of operating conditions to achieve combustion stability and reduce NOx emission at half-load for a 550-MW tangentially fired pulverized coal boiler. Fuel 2021, 306, 121727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.; Zhou, Z.; Ma, X.; Liu, J. Computational investigation of hydrodynamics, coal combustion and NOx emissions in a tangentially fired pulverized coal boiler at various loads. Particuology 2022, 65, 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Chen, Z.; He, E.; Jiang, B.; Li, Z.; Wang, Q. Combustion characteristics and NOx formation of a retrofitted low-volatile coal-fired 330 MW utility boiler under various loads with deep-air-staging. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2017, 110, 223–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, W.; Zheng, Z.; Zhao, N.; Wang, X.; Cheng, Z. Combustion characteristics of a 660 MW tangentially fired pulverized coal boiler considering different loads, burner combinations and horizontal deflection angles. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2024, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhu, S.; Zhu, J.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Hui, J.; Ding, H.; Cao, X.; Lyu, Q. Preheating and combustion characteristics of anthracite under O2/N2, O2/CO2 and O2/CO2/H2O atmospheres. Energy 2023, 274, 127419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, R.; Wang, X.; Li, J.; Cui, B.; Lyu, Z.; Wang, X.; Tan, H. The effect of preheating temperature and combustion temperature on the formation characteristics of PM0.4 from preheating combustion of high-alkali lignite. Fuel 2023, 348, 128560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Z.; Xiong, X.; Tan, H.; Wang, X.; Liu, X.; Rahman, Z.U. Experimental investigation on NO emission and burnout characteristics of high-temperature char under the improved preheating combustion technology. Fuel 2022, 313, 122662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Lin, H.; Zhou, X.; Wang, X.; Zheng, H.; Liu, Y.; Tan, H. CFD modeling and industry application of a self-preheating pulverized coal burner of high coal concentration and enhanced combustion stability under ultra-low load. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2024, 253, 123831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, H.; Ouyang, Z.; Su, K.; Wang, W.; Zhang, J.; Wang, H.; Zhu, S. Experimental research on effects of multi-layer injection of the high-temperature preheated pulverized coal on combustion characteristics and NO emission. Fuel 2023, 347, 128424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.; Liu, Z.; Han, X.; Shen, X.; Liu, Y.; Wang, S.; Xu, Z. Experimental study on combustion characteristics of a 40 MW pulverized coal boiler based on a new low NOx burner with preheating function. Energy 2024, 305, 132319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, J.; Zhu, S.; Zhang, X.; Liu, Y.; Lin, J.; Ding, H.; Su, K.; Cao, X.; Lyu, Q. Experimental study of deep and flexible load adjustment on pulverized coal combustion preheated by a circulating fluidized bed. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 418, 138040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.; Yao, G.; Wang, Z.; Yang, J.; Han, X.; Sun, L.; Xu, Z. Study on low-load combustion characteristics of a 600 MW power plant boiler with self-sustaining internal combustion burners. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2025, 267, 125859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, G.; Han, X.; Liu, Z.; Tang, H.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, Z. Low-NOx study of a 600 MW tangentially fired boiler based on pulverized coal preheating method. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2023, 48, 125859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Tang, H.; Liu, Z.; Han, X.; Shen, X.; Xu, Z. Combustion performance and NOx emissions in a 330 MW tangentially fired boiler retrofitted with preheating combustion devices. Energy 2025, 318, 134803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, W.; Si, F.; Kheirkhah, S.; Yu, C.; Li, H.; Wang, Y. Numerical study on the effects of primary air ratio on ultra-low-load combustion characteristics of a 1050 MW coal-fired boiler considering high-temperature corrosion. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2022, 221, 119811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Huang, S.; Li, H.; Cheng, Z.; Chang, X.; Dong, L.; Kong, D.; Jing, X. Numerical simulation of combustion characteristics in a 660 MW tangentially fired pulverized coal boiler subjected to peak-load regulation. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2023, 49, 103168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Wang, Y.; Wang, X.; Cui, B.; Tan, H. Numerical simulation of NO formation during combustion process of gasified fuel generated from partial gasification of pulverized coal. Process. Saf. Environ. Prot. 2025, 201, 107484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shih, T.-H.; Liou, W.W.; Shabbir, A.; Yang, Z.; Zhu, J. A new k-ϵ eddy viscosity model for high reynolds number turbulent flows. Comput. Fluids 1995, 24, 227–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, J.S.; Silva, V.; Eusébio, D.; Tarelho, L.A.; Hall, M.J.; Dana, A.G. Numerical modelling of ammonia-coal co-firing in a pilot-scale fluidized bed reactor: Influence of ammonia addition for emissions control. Energy Convers. Manag. 2022, 254, 115226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, W.; Si, F.; Cao, Y.; Ma, H.; Wang, Y. Numerical optimization of separated overfire air distribution for air staged combustion in a 1000 MW coal-fired boiler considering the corrosion hazard to water walls. Fuel 2022, 309, 122022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laubscher, R.; Rousseau, P. Numerical investigation into the effect of burner swirl direction on furnace and superheater heat absorption for a 620 MWe opposing wall-fired pulverized coal boiler. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2019, 137, 506–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, H.; Howard, J.; Sarofim, A. Coal devolatilization at high temperatures. Symp. (Int.) Combust. 1977, 16, 411–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, C.; Huang, J.; Sun, R. Numerical optimization of combustion and NOX emission in a retrofitted 600MWe tangentially-fired boiler using lignite. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2023, 226, 120228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, W.; Jo, H.; Lee, J.; Jang, K.; Ryu, C. Numerical investigations on overfire air design for improved boiler operation and lower NOx emission in commercial wall-firing coal power plants. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2022, 219, 119604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolegenova, S.; Askarova, A.; Georgiev, A.; Nugymanova, A.; Maximov, V.; Bolegenova, S.; Adil’Bayev, N. Staged supply of fuel and air to the combustion chamber to reduce emissions of harmful substances. Energy 2024, 293, 130622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baum, M.M.; Street, P.J. Predicting the Combustion Behaviour of Coal Particles. Combust. Sci. Technol. 1971, 3, 231–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeldvich, Y.B. The Oxidation of Nitrogen in Combustion and Explosions. J. Acta Physicochim. 1946, 21, 577. [Google Scholar]

- De Soete, G. Overall reaction rates of NO and N2 formation from fuel nitrogen. Symp. Combust. 1975, 15, 1093–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Wang, C.; Lv, Q.; Li, D.; Liu, H.; Che, D. CFD investigation on combustion and NOx emission characteristics in a 600 MW wall-fired boiler under high temperature and strong reducing atmosphere. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2017, 126, 407–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, H.; Ouyang, Z.; Shi, Y.; Chen, R.; Zhang, Z.; Zhu, S.; Lyu, Q. Effects of the T-abrupt exit configuration of riser on fuel properties, combustion characteristics and NO emissions with coal self-preheating technology. Fuel 2022, 337, 126860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, P.; Tian, D.; Fang, Q.; Ma, L.; Zhang, C.; Chen, G.; Zhong, L.; Zhang, H. Effects of burner tilt angle on the combustion and NOX emission characteristics of a 700 MWe deep-air-staged tangentially pulverized-coal-fired boiler. Fuel 2017, 196, 314–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Case Number | Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 | Case 4 | Case 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Load (MW) | 330 | 231 | 165 | 99 | 66 |

| Running burners | ABCD | ABCD | ABC | AB | AB |

| Total coal feed rate (kg/s) | 52.22 | 36.94 | 26.39 | 16.39 | 10.83 |

| Preheating coal feed rate (kg/s) | 11.11 | 8.33 | 5.56 | 2.78 | 2.78 |

| Preheating air mass-flow (kg/s) | 27.78 | 20.83 | 13.89 | 6.94 | 6.94 |

| Primary air (PA) mass-flow (kg/s) | 118.17 | 82.72 | 59.08 | 35.44 | 23.64 |

| Secondary air (SA) mass-flow (kg/s) | 190.61 | 133.44 | 95.31 | 57.19 | 38.11 |

| SOFA mass-flow (kg/s) | 102.92 | 72.06 | 51.47 | 30.89 | 20.58 |

| PA temperature (K) | 343 | 343 | 343 | 343 | 343 |

| SA temperature (K) | 615 | 589 | 567 | 537 | 537 |

| Boiler outlet temperature (K) | 643 | 621 | 592 | 554 | 492 |

| Feed Rate of Preheated Coal (kg/s) | SR | CO (%) | CO2 (%) | CH4 (%) | H2 (%) | N2 (%) | Flow Rate of Char (kg/s) | Flow Rate of Gas (kg/s) | Temperature of Gas (K) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.78 | 0.42 | 11.68 | 13.20 | 0.68 | 0.65 | 73.79 | 0.96 | 8.77 | 926 |

| 5.56 | 0.42 | 12.33 | 12.74 | 0.80 | 0.68 | 73.45 | 1.89 | 17.55 | 1006 |

| 8.33 | 0.42 | 12.71 | 12.41 | 0.96 | 0.72 | 73.20 | 2.81 | 26.36 | 1121 |

| 11.11 | 0.42 | 13.16 | 12.01 | 1.13 | 0.78 | 72.92 | 3.73 | 35.16 | 1236 |

| Ultimate Analysis (Dry Basis, wt. %) | Vdaf (wt. %) | Qar, net (kJ/kg) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | H | O | N | S | A | 38.63 | 17,220 |

| 63.77 | 3.62 | 15.38 | 0.94 | 0.6 | 15.69 | ||

| Quality Specification | Range | Average Value | Average Standard Value [36] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Equi-angle skewness (QEAS) | 0–0.81 | 0.36 | ≤0.4 |

| Aspect ratio (QAR) | 1–50 | 4.65 | ≤5 |

| Item | 330 MW (Original) | 330 MW (Retrofitted) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measured | Calculated | Error | Measured | Calculated | Error | |

| O2 (%) | 2.98 | 3.16 | 6.0% | 2.12 | 2.04 | 3.8% |

| NOx (mg/m3, at 6% O2) | 185.7 | 194.5 | 4.7% | 126.7 | 121.1 | 4.4% |

| Gas temperature at the furnace outlet (K) | 1279 (design value) | 1200.1 | 6.1% | / | 1254.9 | / |

| Parameters | Criteria | Parameters | Criteria | Parameters | Criteria |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Continuity | 10−6 | ε | 10−6 | CO | 10−4 |

| vx | 10−6 | Energy | 10−6 | CO2 | 10−4 |

| vy | 10−6 | DO | 10−6 | H2 | 10−4 |

| vz | 10−6 | H2O | 10−6 | CH4 | 10−4 |

| k | 10−6 | O2 | 10−4 | vol | 10−4 |

| 66 MW | 99 MW | 165 MW | 231 MW | 330 MW | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ignition distance of burner A/(m) | 5.68 | 3.79 | 2.61 | 2.21 | 2.18 |

| Ignition distance of burner B/(m) | 3.89 | 2.93 | 2.49 | 2.17 | 2.19 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, S.; Tang, H.; Liu, Z.; Xu, Z.; Guo, S. Numerical Simulation of the Combustion Characteristics of a 330 MW Tangentially Fired Boiler with Preheating Combustion Devices Under Various Loads. Processes 2025, 13, 4026. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13124026

Wang S, Tang H, Liu Z, Xu Z, Guo S. Numerical Simulation of the Combustion Characteristics of a 330 MW Tangentially Fired Boiler with Preheating Combustion Devices Under Various Loads. Processes. 2025; 13(12):4026. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13124026

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Siyuan, Hong Tang, Zuodong Liu, Zhiming Xu, and Shuai Guo. 2025. "Numerical Simulation of the Combustion Characteristics of a 330 MW Tangentially Fired Boiler with Preheating Combustion Devices Under Various Loads" Processes 13, no. 12: 4026. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13124026

APA StyleWang, S., Tang, H., Liu, Z., Xu, Z., & Guo, S. (2025). Numerical Simulation of the Combustion Characteristics of a 330 MW Tangentially Fired Boiler with Preheating Combustion Devices Under Various Loads. Processes, 13(12), 4026. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13124026